Volume 26, Issue 4 (Winter 2026)

jrehab 2026, 26(4): 606-625 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Saadati Z, Salmani M, Mansuri B, Asadi M, Paknazar F. Cross-cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Assessment of Evans & Craig’s Interview Protocol for Persian-speaking Preschool Children With and Without Language Impairment. jrehab 2026; 26 (4) :606-625

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3671-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3671-en.html

1- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

2- Neuromuscular Rehabilitation Research Center, Research Institute of Neurosciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran. ,salmani_masoome@yahoo.com

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran. & Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medicine, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

2- Neuromuscular Rehabilitation Research Center, Research Institute of Neurosciences, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran. ,

3- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran. & Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Medicine, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

Keywords: Language disorders, Children, Speech-language pathology, Interview, Psychometrics, Sensitivity, Specificity

Full-Text [PDF 2295 kb]

(81 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1200 Views)

References

Full-Text: (53 Views)

Introduction

Language development is one of the most important developmental milestones in the early years of a child’s life [1]. Language skills not only form the foundation of communicative abilities but also serve as essential prerequisites for learning in educational settings, cognitive growth, and the establishment of social relationships [2]. However, a considerable number of children experience delays or disorders in language acquisition without any underlying hearing, intellectual, or neurological impairments. This group, commonly referred to as children with developmental language disorders or specific language impairment, constitutes approximately 7–10% of preschool-aged children [3]. Late or inaccurate diagnosis of this condition can lead to long-term consequences in academic, emotional, and social domains, including poor academic achievement, social withdrawal, reduced self-esteem, and an increased risk of mental health problems in adulthood [4, 5]. Therefore, accurate and timely assessment of children’s language abilities plays a crucial role in early intervention and improving their overall quality of life [6]. To assess children’s language abilities, speech-language pathologists (SPLs) employ a range of methods generally categorized as structured and non-structured. Non-structured methods, such as spontaneous language sample elicitation during free play, picture description, and story retelling, are recognized as procedures with high diagnostic validity [7, 8]. These approaches elicit natural language behaviors in contexts resembling everyday communication. For instance, Wu et al. demonstrated that interactive play environments not only enhance children’s communicative quality but also reduce their anxiety, leading to more enriched interactions [9]. Despite these advantages, non-structured methods are often limited by factors such as the need for multiple sampling sessions, dependence on the clinician’s skills in interaction management, and the lack of standardized administration protocols [10]. Conversely, structured methods—including formal tests, imitation tasks, and picture-based assessments—are advantageous in terms of time efficiency, comparability, and precision in evaluating specific linguistic domains such as syntax and vocabulary [11, 12]. Nevertheless, these methods may be less effective in representing children’s spontaneous language performance in natural conversational situations [13–16].

In recent years, efforts have been made to combine the advantages of both structured and non-structured methods in language sample elicitation. One of the innovative approaches in this field is semi-structured clinical interviews, which employ both fully structured tasks and spontaneous speech, while allowing researchers to obtain reliable and comparable linguistic data [15, 17]. Evans and Craig’s interview protocol (1992) is one of the most well-known methods in this field. It consists of a 15-minute conversation focusing on the topics “family”, “school”, and “leisure activities” [18]. Studies have shown that children produce a greater number of utterances using this approach compared to free-play approach, and that their speech includes more complex syntactic and semantic structures [14, 17, 19]. Moreover, the data elicited through this interview demonstrate greater stability than those obtained from free play and are less influenced by external factors or the child’s momentary mood [20]. Furthermore, Nelson (1998) reported that adding guided questions to this protocol can elicit more affective and content-rich responses from children [21]. A review of the existing studies indicates that in all studies employing language samples from children, morphological indices (e.g. use of inflectional morphemes), syntactic indices (e.g. mean length of utterance [MLU], ratio of complex to simple sentences, and number of conjunctions), and semantic indices (e.g. type–token ratio [TTR]) have been identified as important criteria for distinguishing children with and without language impairment [22–24].

Despite the advancements, there are still notable gaps in research on language assessment of children through interviews. The majority of existing studies have been conducted in English-speaking countries, including populations that are relatively homogeneous in terms of language, culture, and socioeconomic status [25]. Commonly used Persian tools, such as the test of language development–3 (TOLD–3), are outdated and lack sufficient applicability for analyzing natural conversational samples [26]. Therefore, there is a clear need for a culturally adapted, efficient, and time-effective tool to identify children at risk for language impairment in Iran. Considering the high prevalence of language disorders in the country [27] and their adverse effects on academic performance and family interactions [28, 29], the psychometric evaluation of Evans & Craig’s interview protocol for Persian-speaking preschool children can be helpful. Language assessment instruments for Persian-speaking children should be redesigned through standardized procedures of translation, cultural adaptation, and psychometric validation [30, 31]. The present study, therefore, aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of Evans & Craig’s interview protocol, providing a foundation for early identification, the development of targeted interventions, and the generation of valid, culturally adapted data in the field of child language assessment.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a descriptive psychometric study with a cross-sectional design. The participants were recruited from among second-year preschool students at non-profit (private) preschools in Semnan, Iran, during the 2022–2023 school year (total study population=620). According to Morgan’s table, the required sample size was estimated at 234. However, since schools were used as the unit for randomization and sampling, the final number of children exceeded the estimated number, so 340 samples were selected. To minimize the effects of socioeconomic factors, reduce selection bias, and protect against randomization bias, a cluster random sampling method was employed. Inclusion criteria were monolingual proficiency in Persian and no record of receiving specialized or counseling services during the preschool screening process (including hearing, vision, speech-language, and cognitive assessments). Using the TOLD–3, 60 children (25 girls and 35 boys) were identified as having language impairment. According to Morgan’s table, a minimum of 52 children were required for this group. Among the 280 children who demonstrated typical language development based on the TOLD–3 score, 162 were selected using Morgan’s table to create the comparison group. These normal peers were selected using systematic random sampling, ensuring proportional representation and adherence to the sampling framework. A higher number of children with normal language development were intentionally included for the following reasons: To better represent the natural variability of language and obtain more reliable descriptive indices of central tendency and dispersion, to enhance the generalizability of the findings, to increase the statistical power of the study, to allow for more precise calculations of sensitivity and specificity, and to enable the determination of cutoff points and the definition of normal ranges. Inclusion criteria for language samples were as follows: Being audible and transcribed clearly, with at least two minutes of effective interaction between the child and the examiner. If a language sample was from a child who had no cooperation during the assessment with TOLD–3, it would be excluded from analysis.

Instruments

The TOLD–3 is one of the most valid and comprehensive instruments for assessing language development in children. It consists of six core subtests (picture vocabulary, relational vocabulary, oral vocabulary, grammatical understanding, sentence imitation, and grammatical completion) and three supplementary subtests (word discrimination, phonemic analysis, and word articulation). The reliability of the Persian TOLD–3 ranges from 0.40 to 0.70, and its construct validity for age differentiation ranges between 0.28 and 0.60. The test also has a strong ability to differentiate among children with learning disabilities, language delay, intellectual disabilities, and ADHD. The six core subtests have internal consistency of 0.44-0.79 (mean=0.55). Factor analysis confirmed that all core subtests adequately represent the overall language ability (OLA) as the primary composite quotient. The discriminative power of the six subtests was found to be excellent (0.90–0.97). By combining the standardized scores from the six core subtests, six composite quotients can be calculated. In the present study, the OLA quotient, derived from summing the scores of six core subtests, was used to screen children with and without language impairment. Other composite quotients were not used because they are based on only two subtests and are designed to assess specific domains, such as listening or grammatical skills. According to the test manual, at least one standard deviation below the mean was considered indicative of language impairment [26]. The test results for each participant were recorded on a designed individual scoring sheet.

Evans & Craig’s interview protocol consists of a semi-structured interview designed for language sampling of children aged 8-9 years, with three 5-minute sections of family, school, and leisure activities. The protocol was developed in 1992 to facilitate the production of spontaneous speech within an interactive context, using open-ended questions, natural interactions, and flexible response options to collect valid language samples suitable for analysis of syntactic, semantic, and discourse-level indices. Its short duration and semi-structured design allow simultaneous application in clinical and research settings with time constraints. The psychometric properties of the original version of the interview protocol, including content and construct validity, test–retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability, have been confirmed. Its inter-rater reliability, after re-coding 10% of the samples by a second rater and calculating agreement coefficients, exceeded 85% across all indices.

Psychometric assessment

To assess content validity, five SPLs evaluated the items, and both content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were calculated, all exceeding the recommended thresholds. Construct validity was examined by comparing the syntactic and semantic features of children’s speech during the interview with those observed during free play. Additionally, cross-cultural adaptation was assessed by experts by examining the cultural appropriateness of the protocol for Persian-speaking children. An SPL conducted the interviews in a quiet room in the school. All sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed based on the communication unit (C unit) guidelines and according to the Persian language assessment, remediation, and screening procedure (P-LARSP). The language samples were analyzed by the first author (an MS student in speech-language pathology, who received P-LARSP education) based on structural (syntactic and semantic) and discourse-level indices. In the syntactic domain, variables included MLU (average number of words per C units), the ratio of complex to simple sentences, and the number of conjunctions. In the semantic domain, the TTR was examined. In the discourse domain, indices included self-expressive behaviors (verbal requests, clarification, and statements) and verbal responsiveness. Fluency was assessed through speech disruptions, including filled pauses, unfilled pauses, phrase revisions, and phrase repetitions. For the communication partner, variables such as average number of C units, length of C units, topic shifts, and turn-taking were recorded and compared. Criterion validity of the interview protocol was evaluated by calculating the correlation between the language indices obtained from the interview and the OLA quotient in the TOLD–3. To assess responsiveness to change, the syntactic and semantic indices were evaluated at a 6-month interval. Finally, the overall accuracy of the syntactic and semantic indices in correctly classifying children into the language impairment and typically developed groups was evaluated.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 24. Initially, descriptive statistics (Mean±SD) were used to describe the data. Subsequently, to examine the diagnostic accuracy of language indices in distinguishing between children with language impairment and normal peers, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed. In this analysis, one of the most important measures is the area under the curve (AUC). This measure indicates the extent to which a variable (e.g. MLU or ratio of complex to simple sentences) can differentiate between the two groups of children with and without language impairment. In this study, an AUC>0.70 indicated an appropriate discriminative measure, meaning that the indices had a relatively high ability to correctly identify and differentiate between children with and without language impairment.

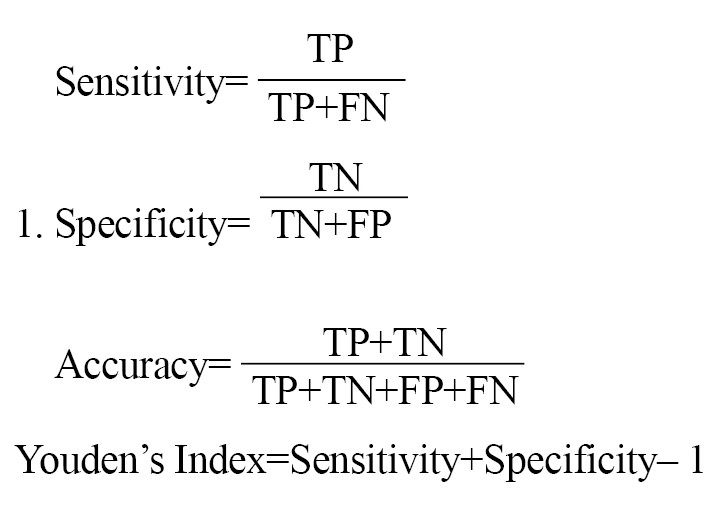

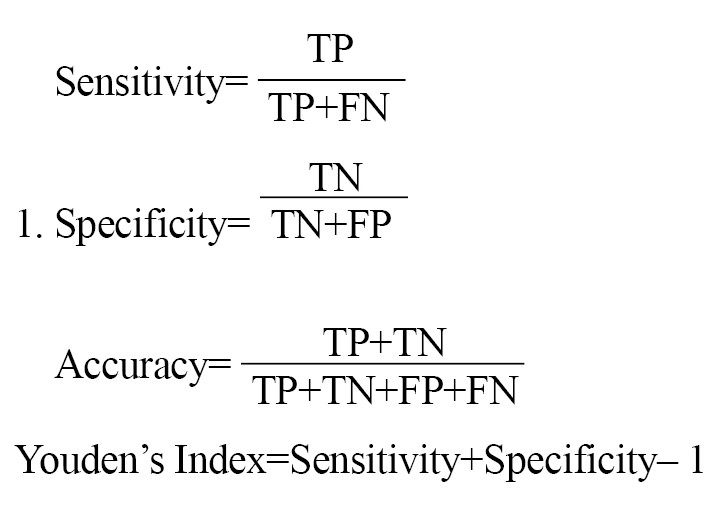

To determine the cutoff point for each index, the Youden index (J=Sensitivity+Specificity–1) was used to achieve an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated based on a classification matrix for each index, using the following parameters: True positive (TP), i.e. the correct identification of a child with language impairment; false positive (FP), i.e. the incorrect identification of a typically developed child as a language-impaired child; true negative (TN), i.e. the correct identification of a typically developed child; and false negative (FN), i.e. the failure to identify a child with language impairment. Based on these parameters, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were calculated as follows (Equation 1):

Criterion validity of the interview protocol was evaluated by using the Spearman correlation coefficient. To assess responsiveness to change, the syntactic and semantic indices were re-evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess their sensitivity to improvements or declines in language performance.

Results

The SPLs confirmed that the Persian version of the interview protocol was valid, understandable, usable, and highly relevant to the objectives of language sampling. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 18 language samples were removed from the study. Among the children with language impairment, 9 children did not engage verbally with the rater prior to assessment, reducing the number of samples in this group to 51. Additionally, 6 language samples from typically developing children were excluded due to their refusal to participate, leaving 156 remaining samples in the healthy group.

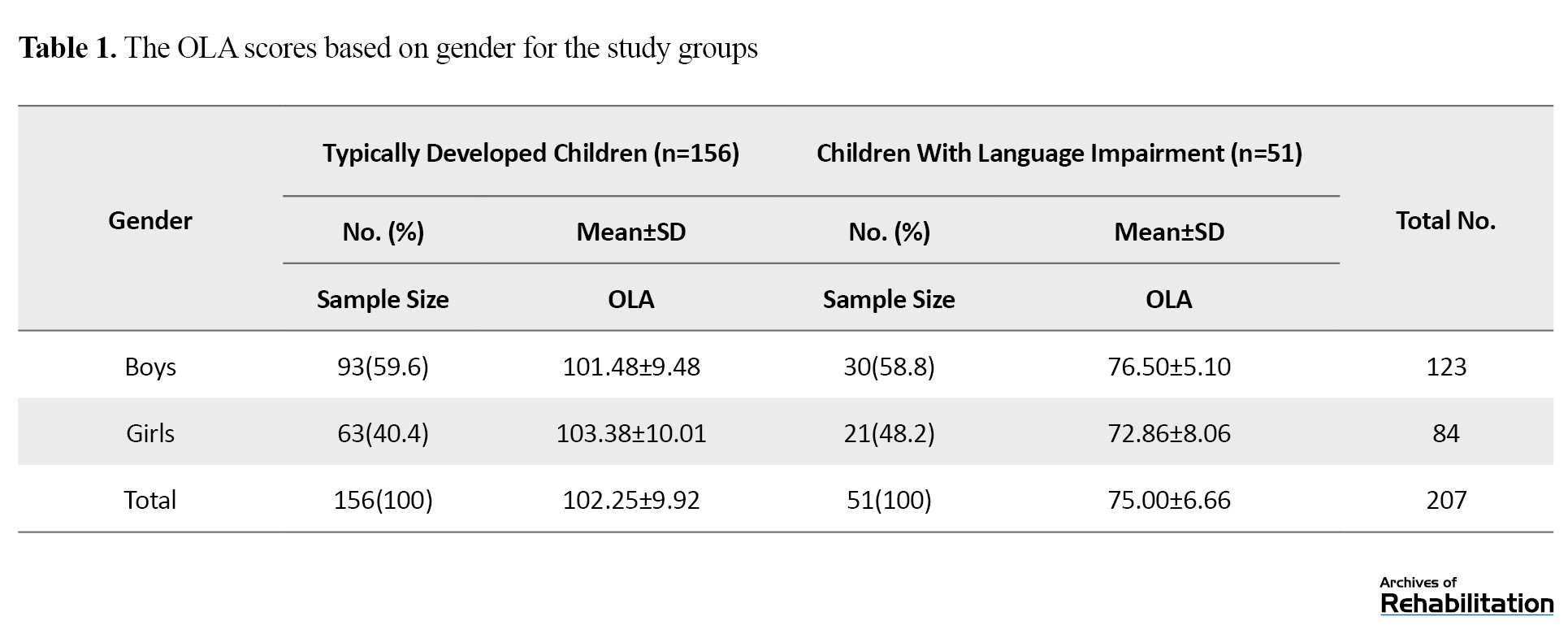

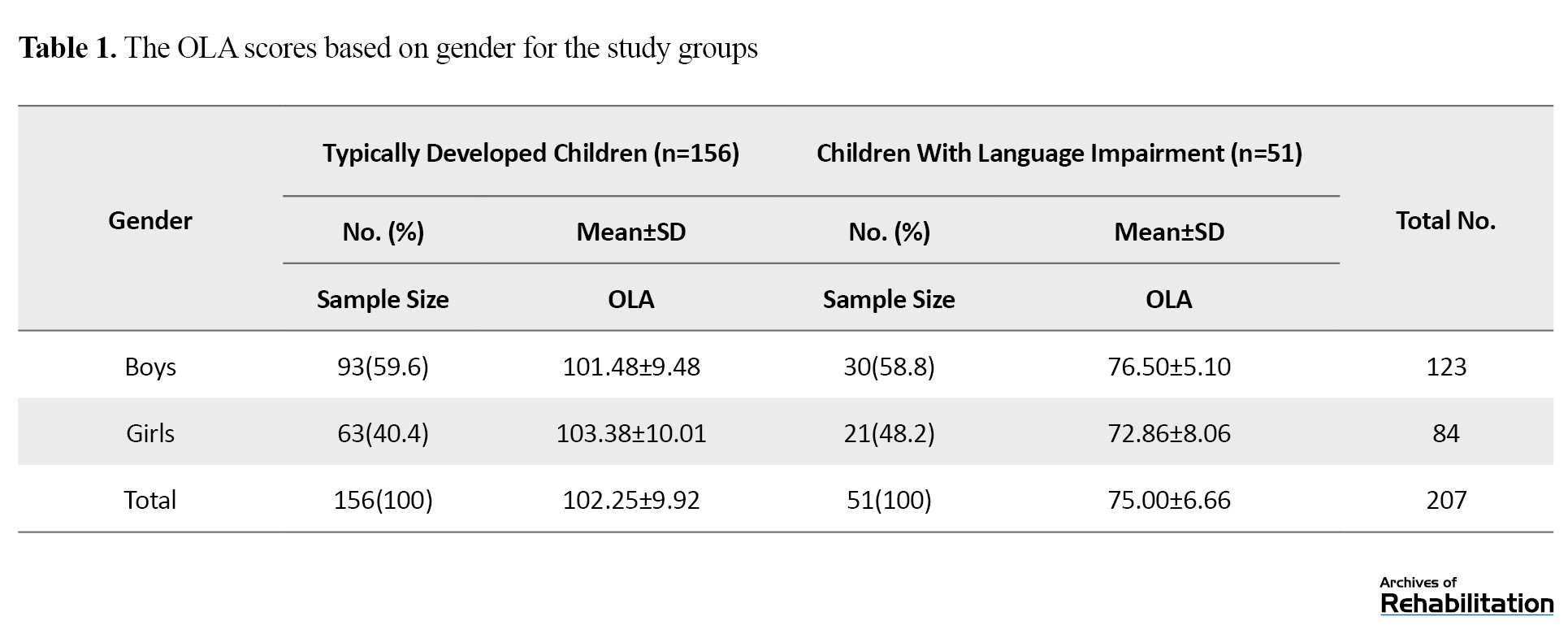

The gender distribution and OLA scores are presented in Table 1.

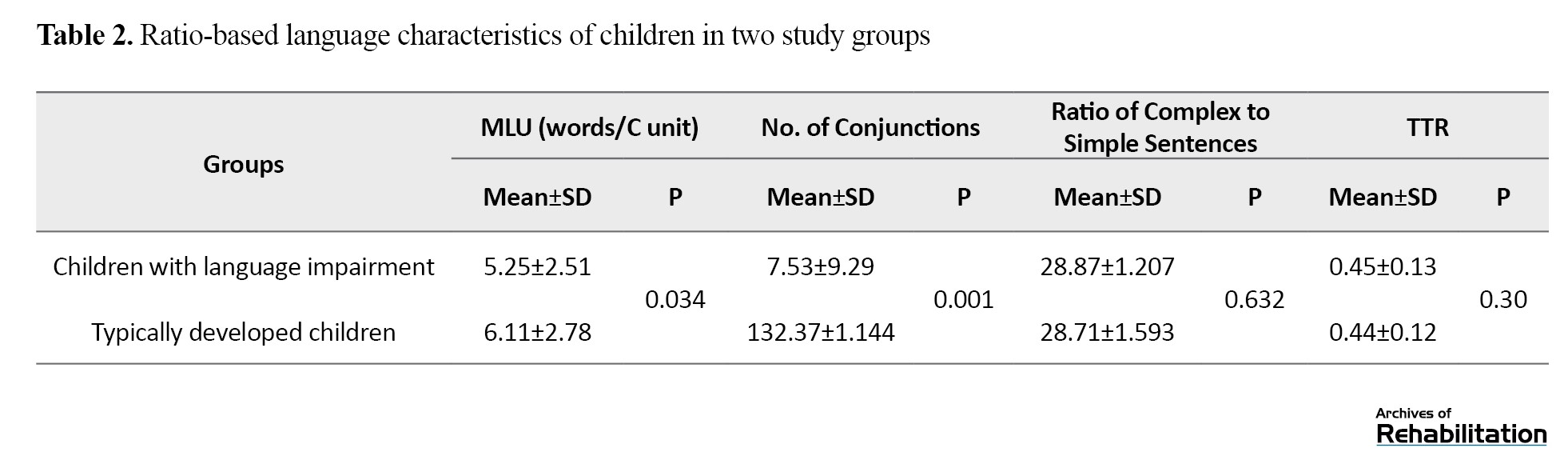

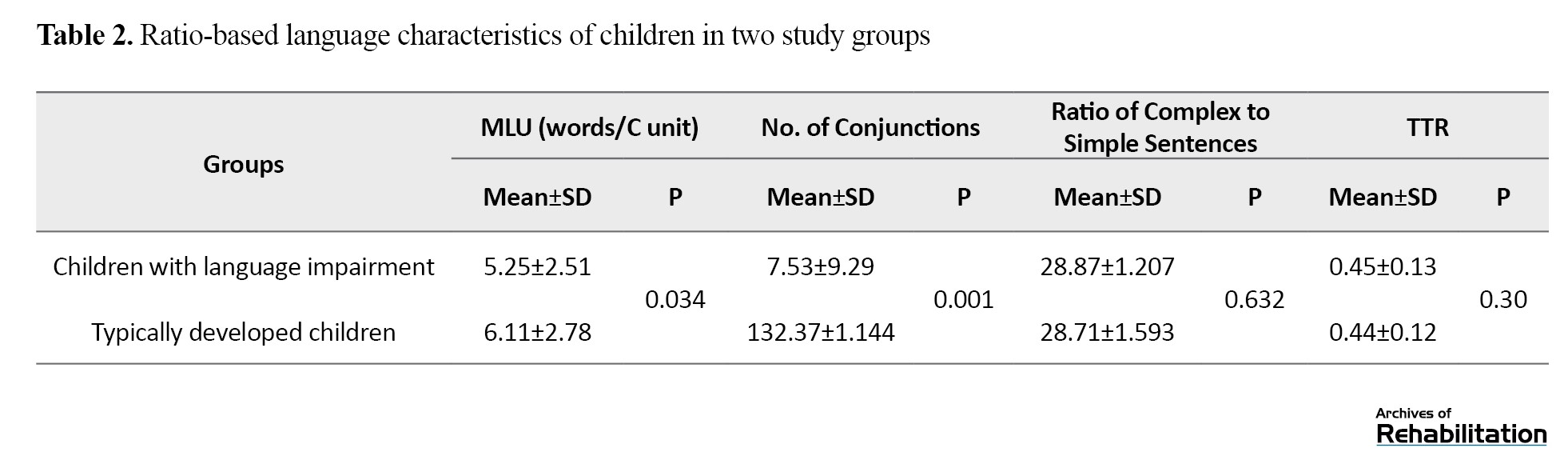

The difference between the two groups in the mean OLA quotient was statistically significant, as determined by the Mann–Whitney U test (P<0.001). The mean age of the language-impaired group was 5.03±0.50 years, and the mean age of the typically developed group was 5.03±0.40 years. The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (P>0.05).Considering the different durations of the interviews (approximately 6 minutes for the language-impaired group and 9 minutes for the typically developed group), the use of time-based cutoffs (e.g. 10 minutes of interaction) or utterance-based cutoffs (e.g. 100 analyzable utterances) was deemed inappropriate. Therefore, only ratio-based indices were reported in the article. Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for these indices and the results of their comparison between the two groups.

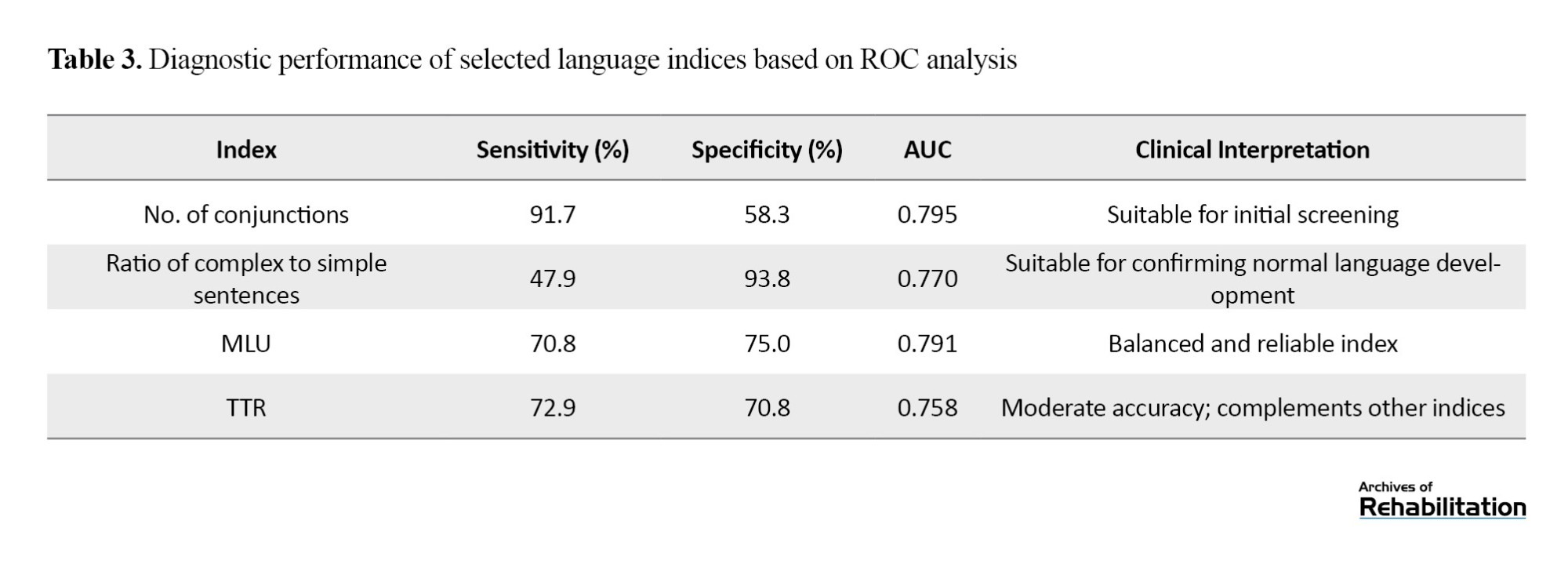

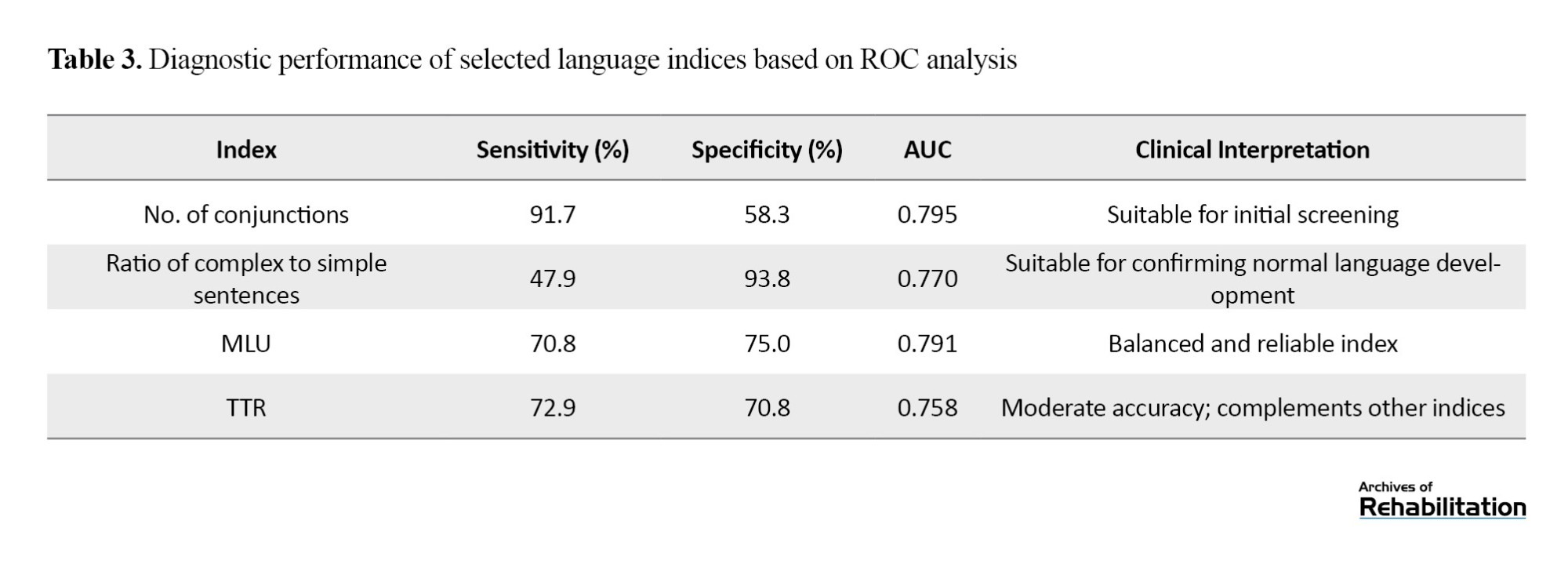

The correlation assessment of the syntactic and semantic indices with the OLA score showed that the highest correlations were observed for the number of conjunctions (r=0.26, P<0.001) and MLU (r=0.19, P=0.005), whereas the TTR did not show a statistically significant correlation. Table 3 summarizes the sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of the main language indices, along with their clinical interpretations based on ROC analysis.

Among the syntactic indices, the ROC analysis showed that the number of conjunctions had the highest ability to identify children with language impairment, with a sensitivity of 91.7% and specificity of 58.3%, making it particularly suitable for initial screening. The ratio of complex to simple sentences showed the highest specificity (93.8%), making it the best indicator for confirming typical language development; however, its low sensitivity (47.9%) indicates a relative limitation in identifying children with language impairment. The MLU exhibited balanced sensitivity and specificity, ranging 70-75%, with an AUC of 0.75-0.82, indicating that it is a reliable index for differentiating between children with and without language impairment.

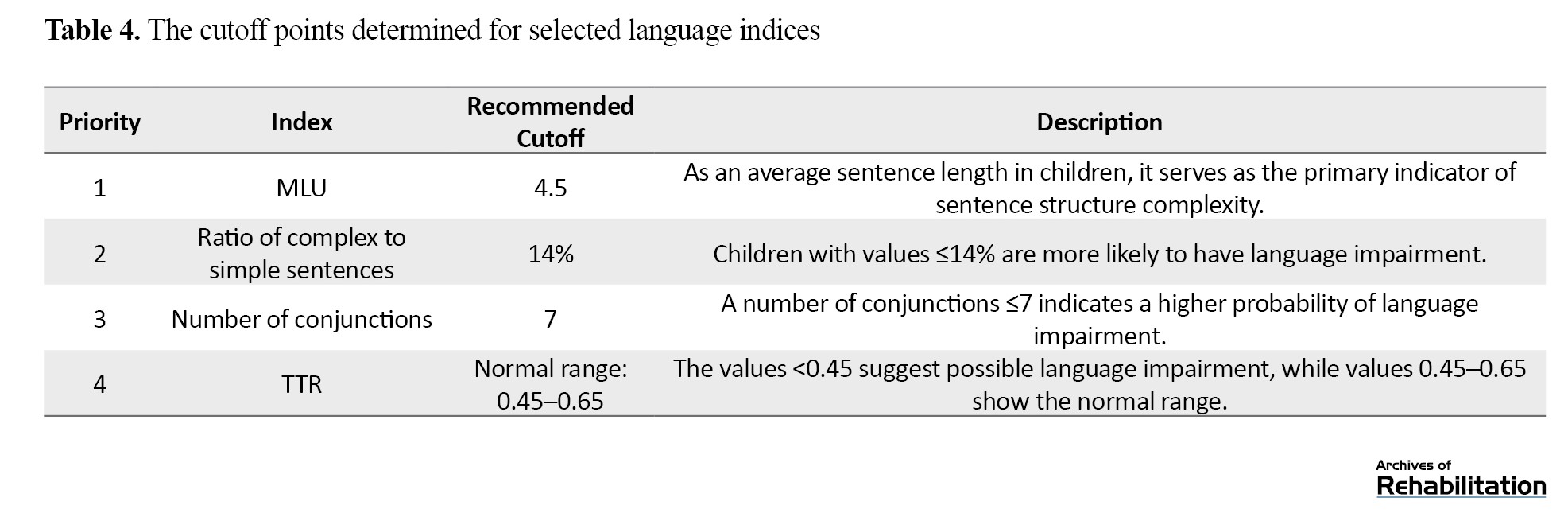

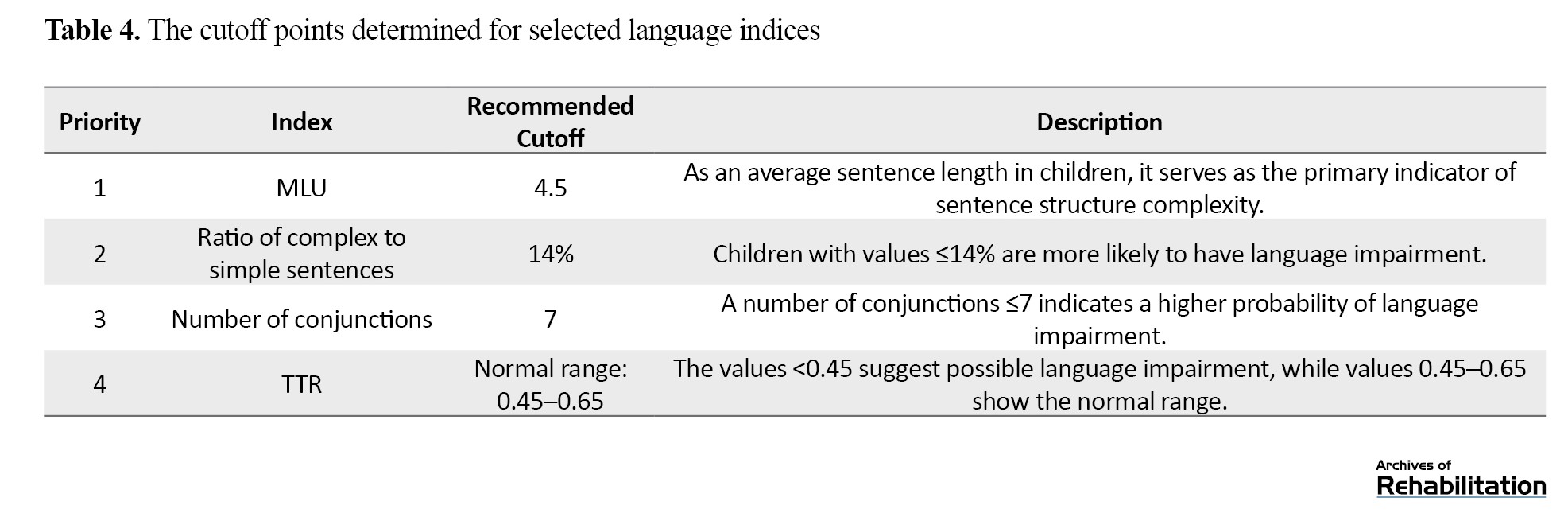

Table 4 presents the optimal cutoff points obtained for each language index, along with their descriptions.

ROC analysis identified the cutoff points for distinguishing between children with and without language impairment as follows: For MLU, 4.05–4.40 words per C unit; for ratio of complex to simple sentences, 29.14%; for number of conjunctions, 7–8; and for TTR, 0.42–0.45. This TTR range yielded the highest Youden’s index (0.38), reflecting an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity. Clinically, a TTR at or below 0.42–0.45 suggests a higher likelihood of language impairment, whereas higher values indicate a greater probability of normal language development. The proposed screening order was: MLU, ratio of complex to simple sentences, number of conjunctions, and TTR. This logical sequence enhances diagnostic accuracy compared with reliance on a single index alone.

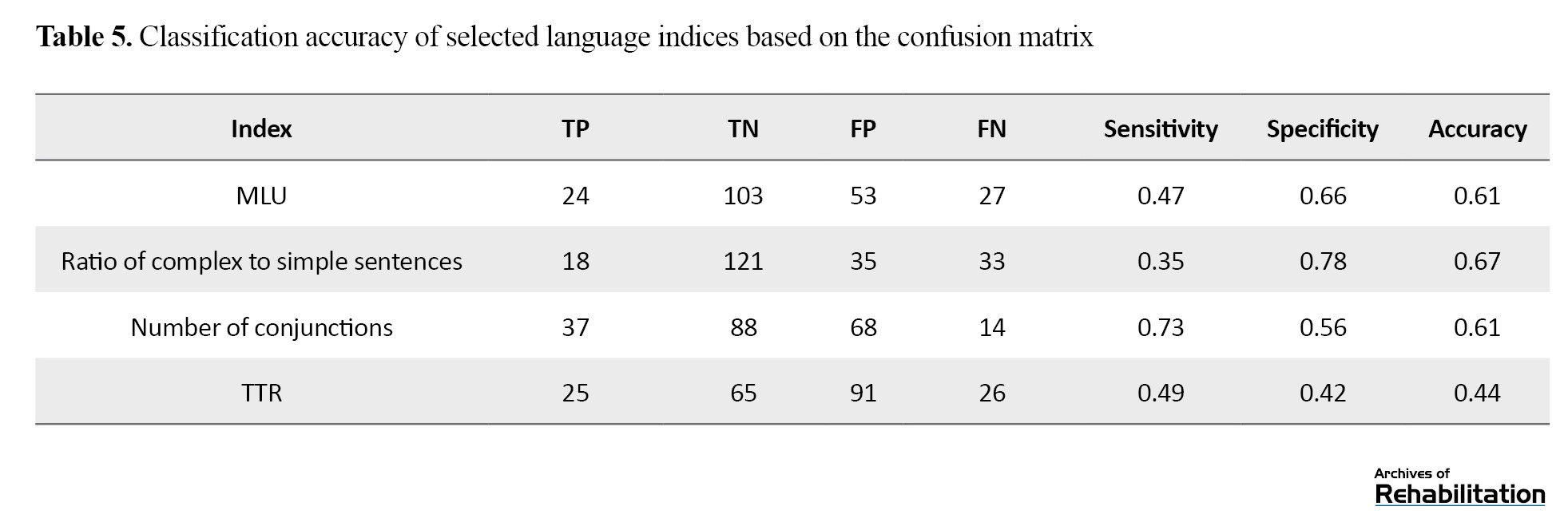

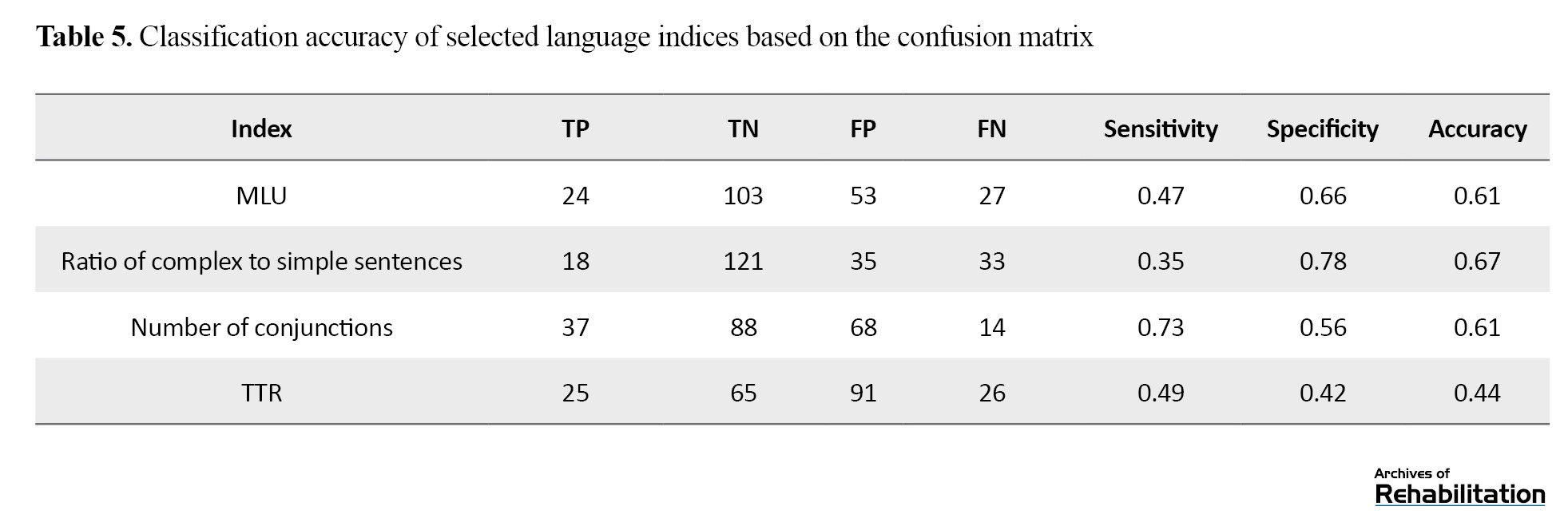

To assess the classification accuracy of each index, a confusion matrix was used. The results are presented in Table 5.

This matrix shows the number of children in each group who were correctly or incorrectly classified by each index. According to the results in this table, the ratio of complex to simple sentences exhibited the highest specificity (78%), making it more suitable for confirming normal language development. The number of conjunctions showed the highest sensitivity (73%), making it more effective for initial screening. The TTR demonstrated the weakest performance based on sensitivity and specificity, and therefore, it is not reliable for diagnosis on its own.

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of Evans & Craig’s interview protocol for the identification and screening of children aged 5–6 years with language impairment. SPLs approved the Persian version for use among Persian-speaking children. The interview administration time was less than 10 minutes for both children with and without language impairment. Given the significant difference in interview duration between children with and without language impairment, ratio-based indices were used to assess the protocol’s sensitivity, specificity, cutoff points, and criterion validity.

The MLU was significantly higher in typically developing children than in children with language impairment. This index demonstrated relatively high sensitivity and moderate specificity, indicating that it correctly identified a large number of children with language impairment but had limitations in fully distinguishing them from typically developing children. These findings are consistent with the studies of Evans and Craig [32] and Kazemi et al. [33], confirming that reduced MLU in children with language impairment is a stable and clinically relevant indicator of language difficulties. However, MLU alone is insufficient to confirm normal language development, as some children with normal language development may exhibit relatively short utterances due to individual or environmental factors. Therefore, examining additional indices is essential for achieving accurate diagnostic conclusions.

The ratio of complex to simple sentences yielded a notable finding. Although the mean values did not differ significantly between the two groups, the index’s specificity was high, indicating that it accurately identified children with normal language development. However, its sensitivity was low, and it failed to identify many children with language impairment. Consequently, the ratio of complex sentences is more suitable for confirming normal language development rather than for screening language disorders. These results are consistent with findings reported in previous studies [34, 35].

Another syntactic index that yielded reliable results in this study was the number of conjunctions. This index was among the most precise syntactic indicators for identifying children with language impairment, exhibiting very high sensitivity while maintaining moderate specificity. This means that the measure was highly effective in detecting children with language difficulties, but it could misclassify some typically developing children as impaired. Consequently, it serves as an ideal index for initial screening. Given that the use of conjunctions reflects advanced syntactic and discourse development, a reduced number of conjunctions may serve as a warning sign of language limitations.

While the syntactic indices demonstrated relatively good discriminative power, the only semantic index, the TTR, showed low diagnostic ability in the ROC analysis. Its sensitivity and specificity were also moderate to low. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have criticized the TTR as being dependent on sample length. In particular, in short language samples, which are common in clinical settings, this index is not reliable for identifying or screening children with and without language impairment, alone without complementary indices.

The combination of multiple indices with high sensitivity, such as the number of conjunctions and MLU, together with indices having high specificity, such as the ratio of complex to simple sentences, resulted in improved classification accuracy. Analysis of the confusion matrix indicated that the simultaneous use of the selected indices significantly enhanced the interview protocol’s predictive power and reduced both type I and type II errors in diagnosis. This finding has important clinical implications, particularly for the screening and early identification of children with language impairment.

Despite its important findings, this study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Although a substantial number of typically developing children were included, the data did not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, generalization of the findings to other age and cultural groups should be done with caution. To achieve more consistent and balanced indices, the inclusion of bilingual groups and children with comorbid conditions (such as ADHD or cognitive disorders) is recommended. It should be emphasized that the results of this study cannot be generalized to these groups. Additionally, the study duration was limited, and some language changes might only become apparent over a longer period. The protocol primarily focused on language indices, and other psycho-social and environmental dimensions were not comprehensively examined.

To enhance the generalizability of the findings and further examine the validity and applicability of the interview protocol, studies with larger and more geographically, culturally, and linguistically diverse populations (including multilingual children and those with language impairments for various reasons) are recommended. Further studies are recommended to clarify the efficiency of the interview protocol for long-term assessment and monitoring of language development, as well as for evaluating the effects of therapeutic interventions on language indices. Additionally, using pragmatic and communicative indices, along with indices obtained from the interview protocol, in future studies may assess and improve SPLs’ ability to diagnose and screen for language impairments.

Conclusion

This Persian version of Evans & Craig’s interview protocol is a valid and reliable tool for Persian-speaking children aged 5-6 years. Therefore, SPLs can use this tool to screen for and identify language impairments in preschool students. The protocol can detect syntactic and semantic differences between children with and without language impairment. Moreover, the correlation of language indices obtained from the interview protocol with the OLA score in the TOLD–3 indicated satisfactory criterion validity. This study suggested that the tool is sensitive to language changes following intervention and can effectively monitor therapeutic progress.

For initial screening of children suspected of language impairment, highly sensitive indices, such as the number of conjunctions, are recommended. To confirm language competence, indices with high specificity, such as the ratio of simple to complex sentences, are more appropriate. Balanced indices, such as the MLU and the TTR, when used in combination with other measures, provide a more comprehensive view of a child’s language status.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran (Code: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1402.227). Parents provided written informed consent, and the children themselves gave verbal consent and expressed their willingness to participate in the study.

Funding

This article was extracted from the thesis of Zahra Saadati at the Department of Speech-Language Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Semnan University of Medical Sciences. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, project management, supervision: Masoumeh Salmani, Banafsheh Mansouri, Fatemeh Paknazar, and Mozhgan Asadi; methodology, validation, analysis: Zahra Saadati, Masoumeh Salmani, Fatemeh Paknazar, Banafsheh Mansouri; Investigation: Zahra Saadati, Masoumeh Salmani, Mozhgan Asadi; Resources, writing: All authors; editing & review: Masoumeh Salmani and Zahra Saadati.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the parents and children who participated in this study for their cooperation as well as Ms. Maryam Imani Dizej Yekan (an MS student in Speech-Language Therapy) for her assistance in the inter-rater reliability assessment.

Language development is one of the most important developmental milestones in the early years of a child’s life [1]. Language skills not only form the foundation of communicative abilities but also serve as essential prerequisites for learning in educational settings, cognitive growth, and the establishment of social relationships [2]. However, a considerable number of children experience delays or disorders in language acquisition without any underlying hearing, intellectual, or neurological impairments. This group, commonly referred to as children with developmental language disorders or specific language impairment, constitutes approximately 7–10% of preschool-aged children [3]. Late or inaccurate diagnosis of this condition can lead to long-term consequences in academic, emotional, and social domains, including poor academic achievement, social withdrawal, reduced self-esteem, and an increased risk of mental health problems in adulthood [4, 5]. Therefore, accurate and timely assessment of children’s language abilities plays a crucial role in early intervention and improving their overall quality of life [6]. To assess children’s language abilities, speech-language pathologists (SPLs) employ a range of methods generally categorized as structured and non-structured. Non-structured methods, such as spontaneous language sample elicitation during free play, picture description, and story retelling, are recognized as procedures with high diagnostic validity [7, 8]. These approaches elicit natural language behaviors in contexts resembling everyday communication. For instance, Wu et al. demonstrated that interactive play environments not only enhance children’s communicative quality but also reduce their anxiety, leading to more enriched interactions [9]. Despite these advantages, non-structured methods are often limited by factors such as the need for multiple sampling sessions, dependence on the clinician’s skills in interaction management, and the lack of standardized administration protocols [10]. Conversely, structured methods—including formal tests, imitation tasks, and picture-based assessments—are advantageous in terms of time efficiency, comparability, and precision in evaluating specific linguistic domains such as syntax and vocabulary [11, 12]. Nevertheless, these methods may be less effective in representing children’s spontaneous language performance in natural conversational situations [13–16].

In recent years, efforts have been made to combine the advantages of both structured and non-structured methods in language sample elicitation. One of the innovative approaches in this field is semi-structured clinical interviews, which employ both fully structured tasks and spontaneous speech, while allowing researchers to obtain reliable and comparable linguistic data [15, 17]. Evans and Craig’s interview protocol (1992) is one of the most well-known methods in this field. It consists of a 15-minute conversation focusing on the topics “family”, “school”, and “leisure activities” [18]. Studies have shown that children produce a greater number of utterances using this approach compared to free-play approach, and that their speech includes more complex syntactic and semantic structures [14, 17, 19]. Moreover, the data elicited through this interview demonstrate greater stability than those obtained from free play and are less influenced by external factors or the child’s momentary mood [20]. Furthermore, Nelson (1998) reported that adding guided questions to this protocol can elicit more affective and content-rich responses from children [21]. A review of the existing studies indicates that in all studies employing language samples from children, morphological indices (e.g. use of inflectional morphemes), syntactic indices (e.g. mean length of utterance [MLU], ratio of complex to simple sentences, and number of conjunctions), and semantic indices (e.g. type–token ratio [TTR]) have been identified as important criteria for distinguishing children with and without language impairment [22–24].

Despite the advancements, there are still notable gaps in research on language assessment of children through interviews. The majority of existing studies have been conducted in English-speaking countries, including populations that are relatively homogeneous in terms of language, culture, and socioeconomic status [25]. Commonly used Persian tools, such as the test of language development–3 (TOLD–3), are outdated and lack sufficient applicability for analyzing natural conversational samples [26]. Therefore, there is a clear need for a culturally adapted, efficient, and time-effective tool to identify children at risk for language impairment in Iran. Considering the high prevalence of language disorders in the country [27] and their adverse effects on academic performance and family interactions [28, 29], the psychometric evaluation of Evans & Craig’s interview protocol for Persian-speaking preschool children can be helpful. Language assessment instruments for Persian-speaking children should be redesigned through standardized procedures of translation, cultural adaptation, and psychometric validation [30, 31]. The present study, therefore, aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of Evans & Craig’s interview protocol, providing a foundation for early identification, the development of targeted interventions, and the generation of valid, culturally adapted data in the field of child language assessment.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a descriptive psychometric study with a cross-sectional design. The participants were recruited from among second-year preschool students at non-profit (private) preschools in Semnan, Iran, during the 2022–2023 school year (total study population=620). According to Morgan’s table, the required sample size was estimated at 234. However, since schools were used as the unit for randomization and sampling, the final number of children exceeded the estimated number, so 340 samples were selected. To minimize the effects of socioeconomic factors, reduce selection bias, and protect against randomization bias, a cluster random sampling method was employed. Inclusion criteria were monolingual proficiency in Persian and no record of receiving specialized or counseling services during the preschool screening process (including hearing, vision, speech-language, and cognitive assessments). Using the TOLD–3, 60 children (25 girls and 35 boys) were identified as having language impairment. According to Morgan’s table, a minimum of 52 children were required for this group. Among the 280 children who demonstrated typical language development based on the TOLD–3 score, 162 were selected using Morgan’s table to create the comparison group. These normal peers were selected using systematic random sampling, ensuring proportional representation and adherence to the sampling framework. A higher number of children with normal language development were intentionally included for the following reasons: To better represent the natural variability of language and obtain more reliable descriptive indices of central tendency and dispersion, to enhance the generalizability of the findings, to increase the statistical power of the study, to allow for more precise calculations of sensitivity and specificity, and to enable the determination of cutoff points and the definition of normal ranges. Inclusion criteria for language samples were as follows: Being audible and transcribed clearly, with at least two minutes of effective interaction between the child and the examiner. If a language sample was from a child who had no cooperation during the assessment with TOLD–3, it would be excluded from analysis.

Instruments

The TOLD–3 is one of the most valid and comprehensive instruments for assessing language development in children. It consists of six core subtests (picture vocabulary, relational vocabulary, oral vocabulary, grammatical understanding, sentence imitation, and grammatical completion) and three supplementary subtests (word discrimination, phonemic analysis, and word articulation). The reliability of the Persian TOLD–3 ranges from 0.40 to 0.70, and its construct validity for age differentiation ranges between 0.28 and 0.60. The test also has a strong ability to differentiate among children with learning disabilities, language delay, intellectual disabilities, and ADHD. The six core subtests have internal consistency of 0.44-0.79 (mean=0.55). Factor analysis confirmed that all core subtests adequately represent the overall language ability (OLA) as the primary composite quotient. The discriminative power of the six subtests was found to be excellent (0.90–0.97). By combining the standardized scores from the six core subtests, six composite quotients can be calculated. In the present study, the OLA quotient, derived from summing the scores of six core subtests, was used to screen children with and without language impairment. Other composite quotients were not used because they are based on only two subtests and are designed to assess specific domains, such as listening or grammatical skills. According to the test manual, at least one standard deviation below the mean was considered indicative of language impairment [26]. The test results for each participant were recorded on a designed individual scoring sheet.

Evans & Craig’s interview protocol consists of a semi-structured interview designed for language sampling of children aged 8-9 years, with three 5-minute sections of family, school, and leisure activities. The protocol was developed in 1992 to facilitate the production of spontaneous speech within an interactive context, using open-ended questions, natural interactions, and flexible response options to collect valid language samples suitable for analysis of syntactic, semantic, and discourse-level indices. Its short duration and semi-structured design allow simultaneous application in clinical and research settings with time constraints. The psychometric properties of the original version of the interview protocol, including content and construct validity, test–retest reliability, and inter-rater reliability, have been confirmed. Its inter-rater reliability, after re-coding 10% of the samples by a second rater and calculating agreement coefficients, exceeded 85% across all indices.

Psychometric assessment

To assess content validity, five SPLs evaluated the items, and both content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were calculated, all exceeding the recommended thresholds. Construct validity was examined by comparing the syntactic and semantic features of children’s speech during the interview with those observed during free play. Additionally, cross-cultural adaptation was assessed by experts by examining the cultural appropriateness of the protocol for Persian-speaking children. An SPL conducted the interviews in a quiet room in the school. All sessions were audio-recorded and transcribed based on the communication unit (C unit) guidelines and according to the Persian language assessment, remediation, and screening procedure (P-LARSP). The language samples were analyzed by the first author (an MS student in speech-language pathology, who received P-LARSP education) based on structural (syntactic and semantic) and discourse-level indices. In the syntactic domain, variables included MLU (average number of words per C units), the ratio of complex to simple sentences, and the number of conjunctions. In the semantic domain, the TTR was examined. In the discourse domain, indices included self-expressive behaviors (verbal requests, clarification, and statements) and verbal responsiveness. Fluency was assessed through speech disruptions, including filled pauses, unfilled pauses, phrase revisions, and phrase repetitions. For the communication partner, variables such as average number of C units, length of C units, topic shifts, and turn-taking were recorded and compared. Criterion validity of the interview protocol was evaluated by calculating the correlation between the language indices obtained from the interview and the OLA quotient in the TOLD–3. To assess responsiveness to change, the syntactic and semantic indices were evaluated at a 6-month interval. Finally, the overall accuracy of the syntactic and semantic indices in correctly classifying children into the language impairment and typically developed groups was evaluated.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed in SPSS software, version 24. Initially, descriptive statistics (Mean±SD) were used to describe the data. Subsequently, to examine the diagnostic accuracy of language indices in distinguishing between children with language impairment and normal peers, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed. In this analysis, one of the most important measures is the area under the curve (AUC). This measure indicates the extent to which a variable (e.g. MLU or ratio of complex to simple sentences) can differentiate between the two groups of children with and without language impairment. In this study, an AUC>0.70 indicated an appropriate discriminative measure, meaning that the indices had a relatively high ability to correctly identify and differentiate between children with and without language impairment.

To determine the cutoff point for each index, the Youden index (J=Sensitivity+Specificity–1) was used to achieve an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated based on a classification matrix for each index, using the following parameters: True positive (TP), i.e. the correct identification of a child with language impairment; false positive (FP), i.e. the incorrect identification of a typically developed child as a language-impaired child; true negative (TN), i.e. the correct identification of a typically developed child; and false negative (FN), i.e. the failure to identify a child with language impairment. Based on these parameters, sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy were calculated as follows (Equation 1):

Criterion validity of the interview protocol was evaluated by using the Spearman correlation coefficient. To assess responsiveness to change, the syntactic and semantic indices were re-evaluated using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess their sensitivity to improvements or declines in language performance.

Results

The SPLs confirmed that the Persian version of the interview protocol was valid, understandable, usable, and highly relevant to the objectives of language sampling. After applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 18 language samples were removed from the study. Among the children with language impairment, 9 children did not engage verbally with the rater prior to assessment, reducing the number of samples in this group to 51. Additionally, 6 language samples from typically developing children were excluded due to their refusal to participate, leaving 156 remaining samples in the healthy group.

The gender distribution and OLA scores are presented in Table 1.

The difference between the two groups in the mean OLA quotient was statistically significant, as determined by the Mann–Whitney U test (P<0.001). The mean age of the language-impaired group was 5.03±0.50 years, and the mean age of the typically developed group was 5.03±0.40 years. The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant (P>0.05).Considering the different durations of the interviews (approximately 6 minutes for the language-impaired group and 9 minutes for the typically developed group), the use of time-based cutoffs (e.g. 10 minutes of interaction) or utterance-based cutoffs (e.g. 100 analyzable utterances) was deemed inappropriate. Therefore, only ratio-based indices were reported in the article. Table 2 presents the means and standard deviations for these indices and the results of their comparison between the two groups.

The correlation assessment of the syntactic and semantic indices with the OLA score showed that the highest correlations were observed for the number of conjunctions (r=0.26, P<0.001) and MLU (r=0.19, P=0.005), whereas the TTR did not show a statistically significant correlation. Table 3 summarizes the sensitivity, specificity, and AUC of the main language indices, along with their clinical interpretations based on ROC analysis.

Among the syntactic indices, the ROC analysis showed that the number of conjunctions had the highest ability to identify children with language impairment, with a sensitivity of 91.7% and specificity of 58.3%, making it particularly suitable for initial screening. The ratio of complex to simple sentences showed the highest specificity (93.8%), making it the best indicator for confirming typical language development; however, its low sensitivity (47.9%) indicates a relative limitation in identifying children with language impairment. The MLU exhibited balanced sensitivity and specificity, ranging 70-75%, with an AUC of 0.75-0.82, indicating that it is a reliable index for differentiating between children with and without language impairment.

Table 4 presents the optimal cutoff points obtained for each language index, along with their descriptions.

ROC analysis identified the cutoff points for distinguishing between children with and without language impairment as follows: For MLU, 4.05–4.40 words per C unit; for ratio of complex to simple sentences, 29.14%; for number of conjunctions, 7–8; and for TTR, 0.42–0.45. This TTR range yielded the highest Youden’s index (0.38), reflecting an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity. Clinically, a TTR at or below 0.42–0.45 suggests a higher likelihood of language impairment, whereas higher values indicate a greater probability of normal language development. The proposed screening order was: MLU, ratio of complex to simple sentences, number of conjunctions, and TTR. This logical sequence enhances diagnostic accuracy compared with reliance on a single index alone.

To assess the classification accuracy of each index, a confusion matrix was used. The results are presented in Table 5.

This matrix shows the number of children in each group who were correctly or incorrectly classified by each index. According to the results in this table, the ratio of complex to simple sentences exhibited the highest specificity (78%), making it more suitable for confirming normal language development. The number of conjunctions showed the highest sensitivity (73%), making it more effective for initial screening. The TTR demonstrated the weakest performance based on sensitivity and specificity, and therefore, it is not reliable for diagnosis on its own.

Discussion

The present study aimed to examine the psychometric properties of the Persian version of Evans & Craig’s interview protocol for the identification and screening of children aged 5–6 years with language impairment. SPLs approved the Persian version for use among Persian-speaking children. The interview administration time was less than 10 minutes for both children with and without language impairment. Given the significant difference in interview duration between children with and without language impairment, ratio-based indices were used to assess the protocol’s sensitivity, specificity, cutoff points, and criterion validity.

The MLU was significantly higher in typically developing children than in children with language impairment. This index demonstrated relatively high sensitivity and moderate specificity, indicating that it correctly identified a large number of children with language impairment but had limitations in fully distinguishing them from typically developing children. These findings are consistent with the studies of Evans and Craig [32] and Kazemi et al. [33], confirming that reduced MLU in children with language impairment is a stable and clinically relevant indicator of language difficulties. However, MLU alone is insufficient to confirm normal language development, as some children with normal language development may exhibit relatively short utterances due to individual or environmental factors. Therefore, examining additional indices is essential for achieving accurate diagnostic conclusions.

The ratio of complex to simple sentences yielded a notable finding. Although the mean values did not differ significantly between the two groups, the index’s specificity was high, indicating that it accurately identified children with normal language development. However, its sensitivity was low, and it failed to identify many children with language impairment. Consequently, the ratio of complex sentences is more suitable for confirming normal language development rather than for screening language disorders. These results are consistent with findings reported in previous studies [34, 35].

Another syntactic index that yielded reliable results in this study was the number of conjunctions. This index was among the most precise syntactic indicators for identifying children with language impairment, exhibiting very high sensitivity while maintaining moderate specificity. This means that the measure was highly effective in detecting children with language difficulties, but it could misclassify some typically developing children as impaired. Consequently, it serves as an ideal index for initial screening. Given that the use of conjunctions reflects advanced syntactic and discourse development, a reduced number of conjunctions may serve as a warning sign of language limitations.

While the syntactic indices demonstrated relatively good discriminative power, the only semantic index, the TTR, showed low diagnostic ability in the ROC analysis. Its sensitivity and specificity were also moderate to low. These findings are consistent with previous studies that have criticized the TTR as being dependent on sample length. In particular, in short language samples, which are common in clinical settings, this index is not reliable for identifying or screening children with and without language impairment, alone without complementary indices.

The combination of multiple indices with high sensitivity, such as the number of conjunctions and MLU, together with indices having high specificity, such as the ratio of complex to simple sentences, resulted in improved classification accuracy. Analysis of the confusion matrix indicated that the simultaneous use of the selected indices significantly enhanced the interview protocol’s predictive power and reduced both type I and type II errors in diagnosis. This finding has important clinical implications, particularly for the screening and early identification of children with language impairment.

Despite its important findings, this study had several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. Although a substantial number of typically developing children were included, the data did not follow a normal distribution. Therefore, generalization of the findings to other age and cultural groups should be done with caution. To achieve more consistent and balanced indices, the inclusion of bilingual groups and children with comorbid conditions (such as ADHD or cognitive disorders) is recommended. It should be emphasized that the results of this study cannot be generalized to these groups. Additionally, the study duration was limited, and some language changes might only become apparent over a longer period. The protocol primarily focused on language indices, and other psycho-social and environmental dimensions were not comprehensively examined.

To enhance the generalizability of the findings and further examine the validity and applicability of the interview protocol, studies with larger and more geographically, culturally, and linguistically diverse populations (including multilingual children and those with language impairments for various reasons) are recommended. Further studies are recommended to clarify the efficiency of the interview protocol for long-term assessment and monitoring of language development, as well as for evaluating the effects of therapeutic interventions on language indices. Additionally, using pragmatic and communicative indices, along with indices obtained from the interview protocol, in future studies may assess and improve SPLs’ ability to diagnose and screen for language impairments.

Conclusion

This Persian version of Evans & Craig’s interview protocol is a valid and reliable tool for Persian-speaking children aged 5-6 years. Therefore, SPLs can use this tool to screen for and identify language impairments in preschool students. The protocol can detect syntactic and semantic differences between children with and without language impairment. Moreover, the correlation of language indices obtained from the interview protocol with the OLA score in the TOLD–3 indicated satisfactory criterion validity. This study suggested that the tool is sensitive to language changes following intervention and can effectively monitor therapeutic progress.

For initial screening of children suspected of language impairment, highly sensitive indices, such as the number of conjunctions, are recommended. To confirm language competence, indices with high specificity, such as the ratio of simple to complex sentences, are more appropriate. Balanced indices, such as the MLU and the TTR, when used in combination with other measures, provide a more comprehensive view of a child’s language status.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran (Code: IR.SEMUMS.REC.1402.227). Parents provided written informed consent, and the children themselves gave verbal consent and expressed their willingness to participate in the study.

Funding

This article was extracted from the thesis of Zahra Saadati at the Department of Speech-Language Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Semnan University of Medical Sciences. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, project management, supervision: Masoumeh Salmani, Banafsheh Mansouri, Fatemeh Paknazar, and Mozhgan Asadi; methodology, validation, analysis: Zahra Saadati, Masoumeh Salmani, Fatemeh Paknazar, Banafsheh Mansouri; Investigation: Zahra Saadati, Masoumeh Salmani, Mozhgan Asadi; Resources, writing: All authors; editing & review: Masoumeh Salmani and Zahra Saadati.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the parents and children who participated in this study for their cooperation as well as Ms. Maryam Imani Dizej Yekan (an MS student in Speech-Language Therapy) for her assistance in the inter-rater reliability assessment.

References

- Deocares NJ, Macaday RJP, Galve MRB, Paderog DCE, Sernicula JB, Hassan DV, et al. Effect of teacher-child interaction on language development in early childhood learners. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology. 2025; (4):1220-5. [DOI:10.38124/ijisrt/25apr820]

- Muhayyo V. Methodology for developing language skills in primary school students. International Journal of Pedagogics. 2025; 5(01):5-6. [Link]

- Laasonen M, Smolander S, Lahti-Nuuttila P, Leminen M, Lajunen HR, Heinonen K, et al. Understanding developmental language disorder-the helsinki longitudinal SLI study (HelSLI): A study protocol. BMC Psychology. 2018; 6(1):24. [DOI:10.1186/s40359-018-0222-7] [PMID]

- Daulay SH, Niswa K, Pratiwi T, Khairun N. Impact of specific language impairment (SLI) in 6-year-old children. Child Education Journal. 2022; 4(2):123-38. [DOI:10.33086/cej.v4i2.3288]

- Flapper BC, Schoemaker MM. Developmental coordination disorder in children with specific language impairment: Co-morbidity and impact on quality of life. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013; 34(2):756-63. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2012.10.014] [PMID]

- Zhang S, Zhang Z, Shen J, Ren L, Yuan Y, Xia L, et al. Construction and application effect analysis of parent training model for children with language development delay: A case study of chongqing area. Education Reform and Development. 2025; 7(3):1-7. [DOI:10.26689/erd.v7i3.10064]

- Caesar LG, Kohler PD. Tools clinicians use:a survey of language assessment procedures used by school-based speech-language pathologists. Communication Disorders Quarterly. 2009; 30(4):226-36. [DOI:10.1177/1525740108326334]

- Kapantzoglou M, Fergadiotis G, Restrepo MA. Language sample analysis and elicitation technique effects in bilingual children with and without language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2017; 60(10):2852-64. [DOI:10.1044/2017_JSLHR-L-16-0335] [PMID]

- Wu HP, Hsieh FH, Chen YL. Interactive gesture-based assessment for preschool hakka language learning: An innovative approach to assessing children’s proficiency. Educational Innovations and Emerging Technologies. 2024; 4(1):28-41. [Link]

- Yonovitz LB, Andrews KR. A Play and story-telling probe for assessing early language content. Journal of Childhood Communication Disorders. 1995; 16(2):10-8. [DOI:10.1177/152574019501600202]

- Horohov JE, Oetting J. Effects of input manipulations on the word learning abilities of children with and without specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2004; 25(1):43-65. [DOI:10.1017/S0142716404001031]

- Spaulding TJ, Plante E, Kimberly FA. Eligibility criteria for language impairment: Is the low end of normal always appropriate? Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2006; 37(1):61-72. [DOI:10.1044/0161-1461(2006/007)] [PMID]

- Eisenberg SL, Govern Fersko TM, Lundgren C. The use of MLU for identifying language impairment in preschool children: A review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2001; 10(4):323-42. [DOI:10.1044/1058-0360(2001/028)]

- Ukrainetz TA, Justice LM, Kaderavek JN, Eisenberg SL, Gillam RB, Harm HM. The development of expressive elaboration in fictional narratives. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2005; 48(6):1363-77. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2005/095)] [PMID]

- Westerveld MF, Gillon GT. Profiling oral narrative ability in young school-aged children. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2010; 12(3):178-89. [DOI:10.3109/17549500903194125] [PMID]

- Westerveld MF, Gillon GT, Moran C. A longitudinal investigation of oral narrative skills in children with mixed reading disability. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2008; 10(3):132-45. [DOI:10.1080/14417040701422390] [PMID]

- Heilmann J, Miller JF, Nockerts A, Dunaway C. Properties of the narrative scoring scheme using narrative retells in young school-age children. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2010; 19(2):154-66. [DOI:10.1044/1058-0360(2009/08-0024)] [PMID]

- Hadley PA. Language sampling protocols for eliciting text-level discourse. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 1998; 29(3):132-47. [DOI:10.1044/0161-1461.2903.132] [PMID]

- Ukrainetz TA. Contextualized language intervention: Scaffolding PreK-12 literacy achievement. London: Thinking Publications; 2007. [Link]

- Bliss LS, McCabe A, Miranda AE. Narrative assessment profile: Discourse analysis for school-age children. Journal of Communication Disorders. 1998; 31(4):347-63. [DOI:10.1016/S0021-9924(98)00009-4] [PMID]

- Nelson NW. Childhood language disorders in context: Infancy through adolescence. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1998. [Link]

- Klee T, Stokes SF, Wong AMY, Fletcher P, Gavin WJ. Utterance length and lexical diversity in Cantonese-speaking children with and without specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004; 47(6):1396-410. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2004/104)] [PMID]

- Thordardottir ET, Weismer SE. Content mazes and filled pauses in narrative language samples of children with specific language impairment. Brain and Cognition. 2002; 48(2-3):587-92. [DOI:10.1006/brcg.2001.1422] [PMID]

- Owen AJ, Leonard LB. Lexical diversity in the spontaneous speech of children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002; 45(5):927-37. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2002/075)] [PMID]

- Paradis J. The interface between bilingual development and specific language impairment. Applied Psycholinguistics. 2010; 31(2):227-52. [DOI:10.1017/S0142716409990373]

- Hasanzadeh S, Minaei A. [Adaptation and standardization of the test of TOLD-P: 3 for Farsi - speaking children of Tehran (Persian)]. Journal of Exceptional Children. 2002; 1(2):119-34. [Link]

- Kianfar F, Akhavan N, Ghasisin L, Sadeghi S, Love T, Blumenfeld HK. Persian adaptation of the SOAP test of sentence comprehension. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups. 2025; 10(3):991-1011. [DOI:10.1044/2025_PERSP-24-00055]

- Armon-Lotem S, De Jong J, Meir N. Assessing multilingual children: Disentangling bilingualism from language impairment. Bristol: Blue Ridge Summit: Multilingual Matters; 2015. [DOI:10.21832/9781783093137]

- Anthony T. Emotional intelligence in second year nursing students: measuring the impact of a single intervention [PhD dissertation]. Kentucky, United States: Bellarmine University; 2022. [Link]

- Nilipour R, Qoreishi ZS, Ahadi H, Pourshahbaz A. Development and standardization of persian language developmental battery. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2023; 24(2):172-95. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.24.2.2191.5]

- Koohestani F, Rezaei P, Nakhshab M. Developing a Persian version of the checklist of pragmatic behaviors and assessing its psychometric properties: A preliminary study. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2020; 21(3):358-75. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.21.3.2923.1]

- Evans JL, Craig HK. Language sample collection and analysis: Interview compared to freeplay assessment contexts. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1992; 35(2):343-53. [DOI:10.1044/jshr.3502.343] [PMID]

- Kazemi Y, Klee T, Stringer H. Diagnostic accuracy of language sample measures with Persian-speaking preschool children. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics 2015; ;29(4):304-18. [PMID]

- Paradis J, Sorenson Duncan T, Thomlinson S, Rusk B. Does the use of complex sentences differentiate between bilinguals with and without DLD? Evidence from conversation and narrative tasks. Frontiers in Education. 2022; 6:2021. [DOI:10.3389/feduc.2021.804088]

- Thompson CK, Shapiro LP. Complexity in treatment of syntactic deficits. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2007; 16:30-42. [DOI:10.1044/1058-0360(2007/005)] [PMID]

Type of Study: Applicable |

Subject:

Speech & Language Pathology

Received: 5/08/2025 | Accepted: 6/12/2025 | Published: 1/01/2026

Received: 5/08/2025 | Accepted: 6/12/2025 | Published: 1/01/2026

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |