Volume 26, Issue 3 (Autumn 2025)

jrehab 2025, 26(3): 464-489 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mousavi N, Poursharifi H, Momeni F, Pourshahbaz A, Rapee R. Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Adolescent Life Interference Scale for Internalizing Symptoms in Iranian Adolescents. jrehab 2025; 26 (3) :464-489

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3492-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3492-en.html

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,ha.poursharifi@uswr.ac.ir

3- Centre for Emotional Health, School of Psychological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Centre for Emotional Health, School of Psychological Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia.

Keywords: Adolescents, Anxiety disorders, Depressive disorders, Life interference, Reliability, Validity

Full-Text [PDF 3018 kb]

(319 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2005 Views)

References

Full-Text: (330 Views)

Introduction

Anxiety and depressive disorders are common during adolescence [1]. A national study conducted in Iran on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents showed that 14.13% of participants aged 6-18 years had anxiety disorders and 2.15% had a mood disorder [2]. Following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, an increasing trend in the incidence of mental health-related problems in this age group was observed [3]. Adolescents diagnosed with mood and/or anxiety disorders are at a higher risk of experiencing mental health problems in adulthood, academic failure, and communication problems compared to their healthy peers [4]. These disorders lead to increased use of governmental healthcare services and reduced participation in the labor market. The physical health and quality of life of adults who have suffered from these disorders during adolescence are also lower than those of other people [5].

Comorbidity between anxiety and depressive disorders is higher in adolescence [6], compared to childhood [7]. In Iran, the comorbidity is greater than 50% among individuals aged 6-18 years [2]. Adolescents with comorbid depression and anxiety exhibit greater impairments than those diagnosed with either of them, and their treatment is also more difficult [8-10]. Common cognitive, behavioral, and emotion regulation processes in anxiety and depressive disorders that can be targeted for treatment are of great importance [11, 12]. However, adults usually underestimate the severity of these disorders in their adolescent children and interpret their symptoms as a mere transitional phase. Consequently, the majority of these adolescents do not receive any treatment [13]. Therefore, acquiring a deep understanding of these disorders and their impact on adolescents is necessary, and appropriate instruments tailored to adolescents are required for this purpose.

One of the important aspects in the study of anxiety and depressive disorders is functional impairment. It represents a key aspect of mental health in adolescents and offers valuable insight into the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms, which is a key factor in clinical assessments and treatment planning. Early identification and treatment of functional impairments can prevent the persistence of these disorders in adulthood [7, 14]. Functional impairment refers to specific limitations in various functional domains in daily life that are caused by a disorder. These domains include cognitive abilities, academic or occupational performance, interpersonal relationships, age-appropriate self-care capacity, and the capacity to enjoy life, which includes the use of leisure time for self-fulfillment [15, 16]. By assessing functional impairment, the impact of an individual’s symptoms on the level of impairment can be examined, or the improvement in performance resulting from psychological interventions can be measured [17, 18].

Despite the importance of this issue in research and clinical practice, the development of measurement instruments for functional impairment is limited. This limitation is even more evident for adolescents [7]. Although instruments such as the Child Activity Limitations Interview [19], Functional Disability Inventory [20] and Functional Status Inventory [16] have been developed for this purpose, they are not specific to adolescents and can also be used for children. The age-specific instruments for measuring functional impairment in adolescents should be designed to capture the challenges that adolescents face during adolescence. This period is characterized by rapid changes in cognitive, emotional, and social functioning, many of which differ significantly from those of children and adults [21-23]. For example, adolescents with psychiatric disorders use avoidance strategies more than children. Higher use of avoidance is associated with a greater level of impairment [14, 24]. Relationships with peers play a key role in the lives of adolescents, and their importance for adolescents is more than for children or adults. Any effect on peer relationships can influence adolescents’ functioning [21]. Hence, it is essential to utilize specialized instruments tailored to this age group. For this purpose, Schniering et al. [7] developed the adolescent life interference scale for internalizing symptoms (ALIS-I). While this measure has shown promise for adolescents from Australia and the United States, it is important to evaluate its psychometric properties for other countries with different cultures. The nature and extent of functional impairment vary from culture to culture. Even basic language differences can influence the responses or may affect the nuances of item interpretation [25-27].

Previous studies have suggested that Iranian adolescents have high functional impairment. For example, Hadianfard et al. showed that 29.5% of Iranian adolescents had significant deficits in domains such as life and school skills [28]. However, to date, no self-report tool has been specifically designed to assess the functional impairment and interference of anxiety and depression symptoms in Iranian adolescents. Considering the high prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders in Iranian adolescents, a standardized tool is required to investigate the complications of depression and anxiety symptoms in this group. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the ALIS-I for examining functional impairment and life interference related to anxiety and depression in Iranian adolescents.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This is a descriptive and psychometric study that was conducted in 2022. Participants were adolescents aged 11-18 from different cities in Iran. According to Kline, a sample size of at least 5-20 is needed for each parameter or item in structural equation models [29]. As the ALIS-I had 26 items, 130-520 samples were required. In this regard, 384 adolescents were included in this study with a mean age of 15.54±1.62 years: 322 nonclinical samples (83.8%) and 62 clinical samples (16.2%). Sampling was done using a convenience sampling method. The clinical samples were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: Age 11-18 years and the diagnosis of depression or anxiety disorders based on the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) held by the research team. The comorbid psychiatric problems (e.g. eating disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and substance abuse) were accepted in the clinical samples only if anxiety or depression were the main complaint. The exclusion criteria for clinical samples were comorbid bipolar or psychotic disorder.

For selecting clinical samples, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, invitation was done online by sending links or designed posters on popular social networks (Instagram, WhatsApp, and Telegram) to adolescents with self-reported symptoms of anxiety or depression from all over the country, or asking adolescent psychologists to introduce their adolescent clients suffering from anxiety and/or depression. After all volunteers had contacted the researcher, they were asked questions during a phone call to verify the inclusion and exclusion criteria and underwent the SCID-5. After checking the criteria, a link containing consent forms and questionnaires was sent to these samples. The online survey link was generated on the Porsline website.

For selecting nonclinical samples, another invitation poster was designed. To encourage participation in the study, a free internet package was offered by lottery to 20 participants. Nonclinical participants were excluded if they had visited a psychiatrist or psychologist in the last three months for the treatment of any anxiety, depression, bipolar, substance abuse, or psychotic disorder, or were currently taking psychotropic medication.

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

Permission for the translation and psychometric assessment of the ALIS-I was first obtained from the developer of the ALIS-I. The translation and cross-cultural adaptation were then carried out in five steps using Beaton et al.’s method [30]. Two native Persian speakers, each with fluency in English (one was a PhD candidate in clinical psychology and the other was an adolescent psychotherapist), conducted the English-to-Persian translation separately. Two translated drafts in Persian were merged to develop a single draft. This was translated back into English by two other translators with master’s degrees in English literature, with no background in psychology. A statistician was also invited to supervise the translation and cultural adaptation process. After comparing the Persian and English drafts, the final draft in Persian was prepared and approved by all authors. Before using the scale, it was presented to 30 adolescents (19 girls and 11 boys, aged 11-18 years) residing in Tehran, Iran, and they were asked to answer the items online. They were encouraged to mark any item that was unclear to them. Then, the draft was modified based on their comments, and the final Persian version was developed (Appendix 1).

The feedback showed that the sentences were meaningful, and no changes were needed in any items

Measures

SCID-5

The SCID-5 is a semi-structured interview for the diagnosis of mental disorders according to the DSM-5 criteria. This tool is administered by a trained clinical psychologist familiar with the diagnostic criteria and classification of DSM-5 disorders. The diagnostic coverage and the language used in the SCID-5 make it suitable for people over age 18 years, and with a brief rewording of the questions, the tool can also be used for adolescents [31].

ALIS-I

The ALIS-I is a 26-item self-report tool developed by Schniering et al. [7] to evaluate the extent of functional impairment across various social contexts (i.e. school performance, sports, and peers/family) over the past month. It is a reliable and valid tool for clinical and nonclinical samples aged 11-18. It has four subscales representing common areas of life interference frequently reported by this age group: Withdrawal/avoidance (9 items), somatic symptoms (3 items), problems with study/work (6 items), and peer problems (4 items). The other four items are not related to any of these subscales. The responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time). The overall scale has high internal consistency (α=0.94). The Cronbach’s α values for the subscales were: 0.91 for withdrawal/avoidance, 0.76 for somatic symptoms, 0.86 for problems with study/work, and 0.81for peer problems. In this scale, higher scores indicate greater life interference [7].

The emotional avoidance strategy inventory for adolescents (EASI-A)

The EASI-A is a self-report inventory developed by Kennedy and Ehrenreich-May in 2017 [32] to assess emotional avoidance. This tool has 33 items rated on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all true of me) to 4 (extremely true of me). It has three subscales, including “avoidance of thoughts and feelings” (e.g. “I do whatever I can to avoid feeling sad or worried or afraid”), “avoidance of emotion expression” (e.g. “I have a hard time showing my true feelings”), and “active avoidance coping” (e.g. “I prefer to keep conversations happy or light.”). The EASI-A has high validity and reliability for children and adolescents [32]. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this inventory were assessed and confirmed by Mousavi et al. They reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.71 for its reliability [33].

Psychometric assessments

Construct validity

To assess the factor structure of the Persian ALIS-I, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the weighted least squares mean and variance (WLSMV) estimation [34] in Mplus software, version 7.11. This estimation method yields more precise results for categorical data compared to the traditional maximum likelihood approach [35]. Target rotation was used in the structural equation modeling (SEM) due to the confirmatory approach of the models. A two-step approach was employed to identify the model that best fits the data, and the chi-square (χ2), Tucker‒Lewis index (TLI), weighted root mean square residual (WRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) results were then compared. The models were considered fit based on the recommendations proposed by Hu and Bentler: CFI >0.90, GFI >0.9, RMSEA <0.08 as good and <0.1 as acceptable, TLI >0.9, and WRMR <0.08 [36]. To choose the most suitable structure for the Persian version of the ALIS-I, five models were considered as follows: (a) Unidimensional model: each item is loaded on a single factor, (b) First-order four-factor model: This model was selected based on the original version. Items 1-9 were loaded on withdrawal/avoidance, items 10-12 on somatic symptoms, item 13-18 on problems with study/work, and items 19-22 on peer problems, (c) Higher-order or second-order four-factor model: In this model, the four first-order factors were loaded on a higher-order factor called ALIS-I, (d) Bifactor model: In this model, ALIS-I was considered a general factor independent of the four specific factors. The bifactor model offers an alternative to the traditional higher-order factorial model by allowing items to simultaneously load on a “general” factor as well as on four specific factors. These specific factors reflect the unique variance shared among the items making up the four subscales – that is, the variance that the general factor cannot explain. (d) First-order four-factor exploratory SEM (ESEM): In this model, the four factors were estimated as distinct yet correlated first-order factors. In hierarchically organized constructs such as those in ALIS-I, these first-order ESEMs likely overlook the presence of a hierarchically superior construct, which may instead be expressed through hyper inflated cross-loadings [37]. Asparouhov and Muthén, by proposing the ESEM method, claimed that this method integrates the strengths of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, regardless of their limitations [38]. ESEM, like exploratory factor analysis (EFA), permits items to load on all factors simultaneously. On the other hand, this method has all the advantages of CFA, such as the ability to calculate standard errors and the measurement invariance test [38, 39]. Also, it should be noted that no missing data or unengaged response patterns was found.

Reliability

Internal consistency was determined by calculating Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s omega. Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s omega values equal to or higher than 0.70 were considered acceptable. To assess the test re-test reliability, 30 clinical samples completed the ALIS-I at a three-week interval. Then, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated. The two-way random model with the absolute agreement approach was used to examine the ICC. An ICC in the range of 0.40-0.59 indicates fair, 0.60-0.75 good, and ≥0.76 excellent reliability [40].

Convergent and divergent validity

The average variance extracted (AVE) based on Fornell-Larcker criterion and Pearson’s correlation test (to assess the relationship between the ALIS-I and EASI-A scores) were used to evaluate convergent validity [41]. Acceptable values for convergent validity were: AVE>0.5, CR>0.7, and CR>AVE. To examine divergent validity, scores on the ALIS-I and its subscales were compared between the clinical and nonclinical samples using the independent t-test.

Data analysis

Descriptive and correlational analyses were performed in the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software, version 27, and MacDonald’s omega coefficient for reliability estimation was calculated in the SPSS OMEGA macro.

Results

The nonclinical samples included 170(52.8%) females and 152(47.2%) males. Their mean age was 15.78±1.43 years. Their field of study was mathematics & physics (n=150, 46.6%), technical and vocational sciences (n=73, 22.7%), experimental sciences (n=58, 18%), or humanities (n=41, 12.7%). The educational level of their fathers was a high school diploma (n=124, 38.5%), a bachelor’s degree (n=78, 24.2%), lower than a high school education (n=69, 21.4%), or a master’s degree or higher (n=51, 15.9%). The clinical samples included 52(83.9%) females and 10(16.1%) males. Their mean age was 14.16±1.92 years. Their field of study was technical and vocational sciences (n=19, 30.6%), experimental sciences (n=19, 30.6%), humanities (n=18, 29%), or mathematics & physics (n=6, 9.7%). The educational level of their fathers was a high-school diploma (n=22, 35.5%), a bachelor’s degree (n=17, 27.4%), a master’s degree or higher (n=11, 19.7%), or lower than a high school education (n=12, 19.4%).

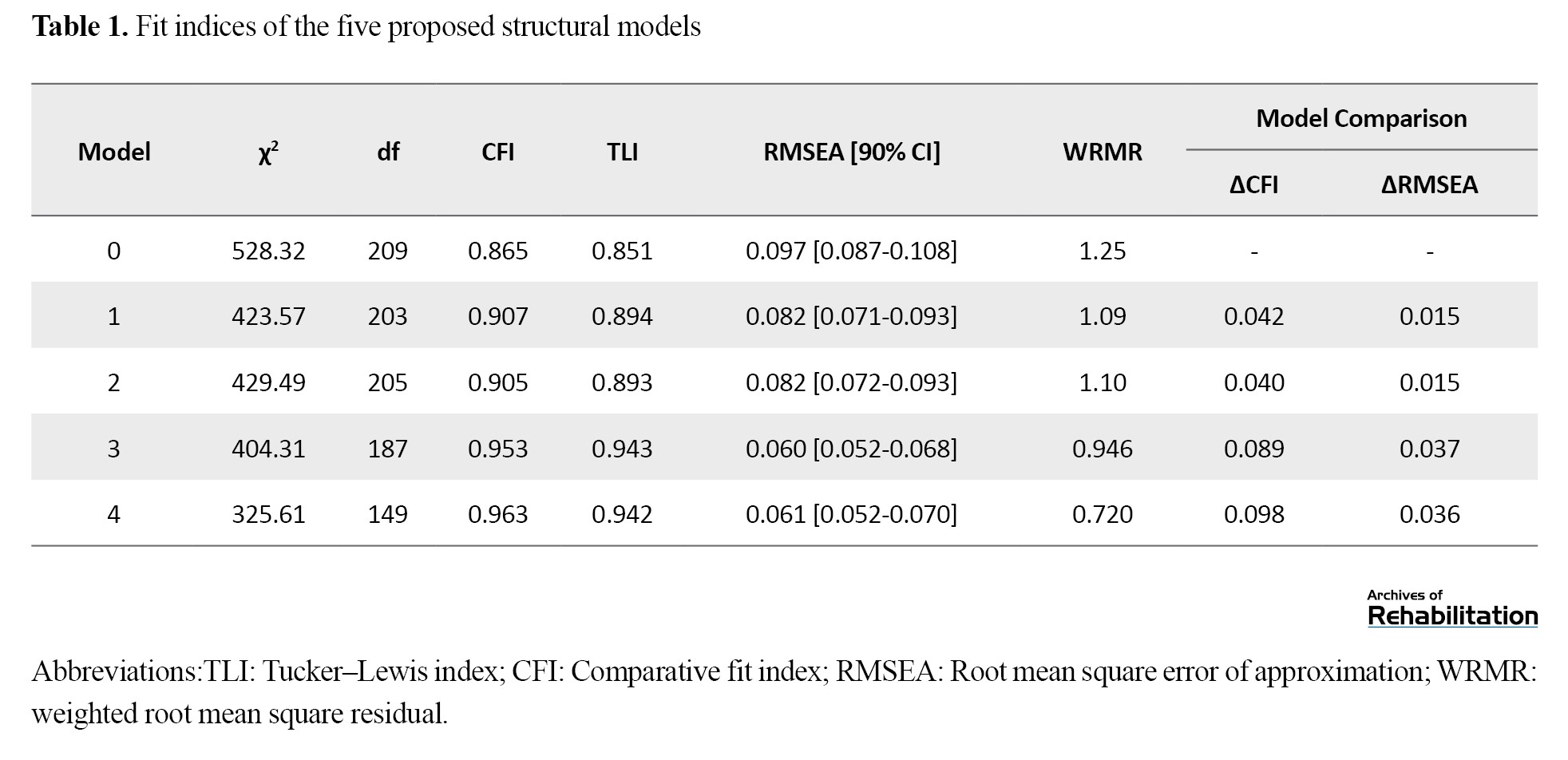

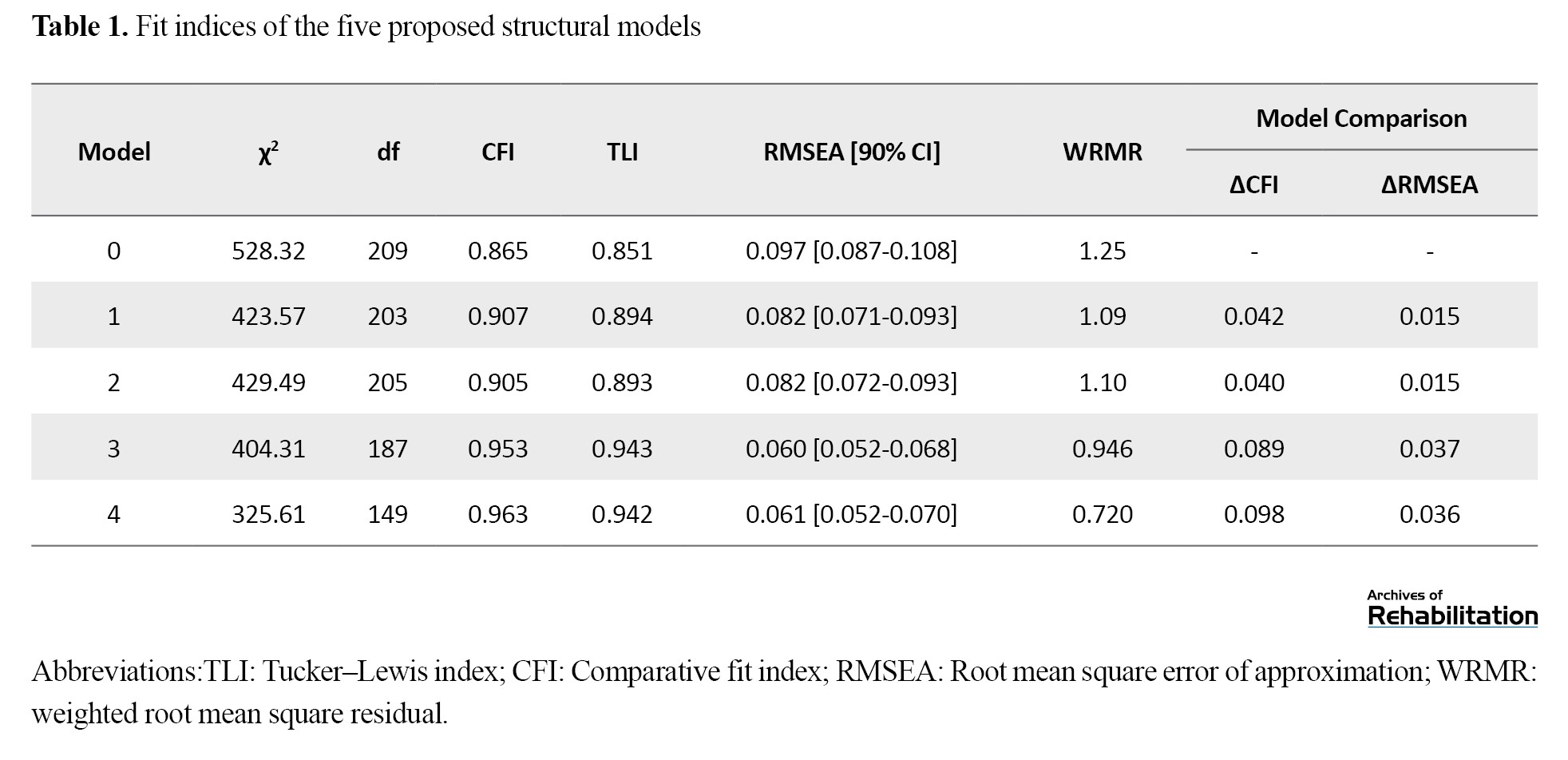

Table 1 presents the fit indices of the five proposed models.

The single-factor model (model 0) had a poor fit. Considering CFI>0.9 and RMSEA<0.1, the four-factor (model 1) and second-order CFA models (model 2) had a relatively good fit. The bifactor model (model 3) and ESEM model (model 4) were then analyzed. The fit indices showed that these two models fit the data very well. Then, the single-factor model was taken as a reference, and the other models were compared to it. Table 2 shows that the ∆CFI and ∆RMSEA of models 1 to 4 were greater than 0.01, indicating a better fit of these models compared to the single-factor model [42].

The Model 4 demonstrated a significantly better fit to the data compared to Model 3 (∆χ2=78.7; ∆df=38; P <0.001; ∆CFI=0.01; ∆TLI=0.001; ∆RMSEA=0.001; ∆WRMR=0.226), Model 2 (∆χ2=103.88; ∆df=56; P<0.001; ∆CFI=0.058; ∆TLI=0.049; ∆RMSEA=0.021; ∆WRMR=0.38), and Model 1 (∆χ2=97.96; ∆df=54; P<0.001; ∆CFI=0.056; ∆TLI=0.048; ∆RMSEA=0.021; ∆WRMR=0.37).

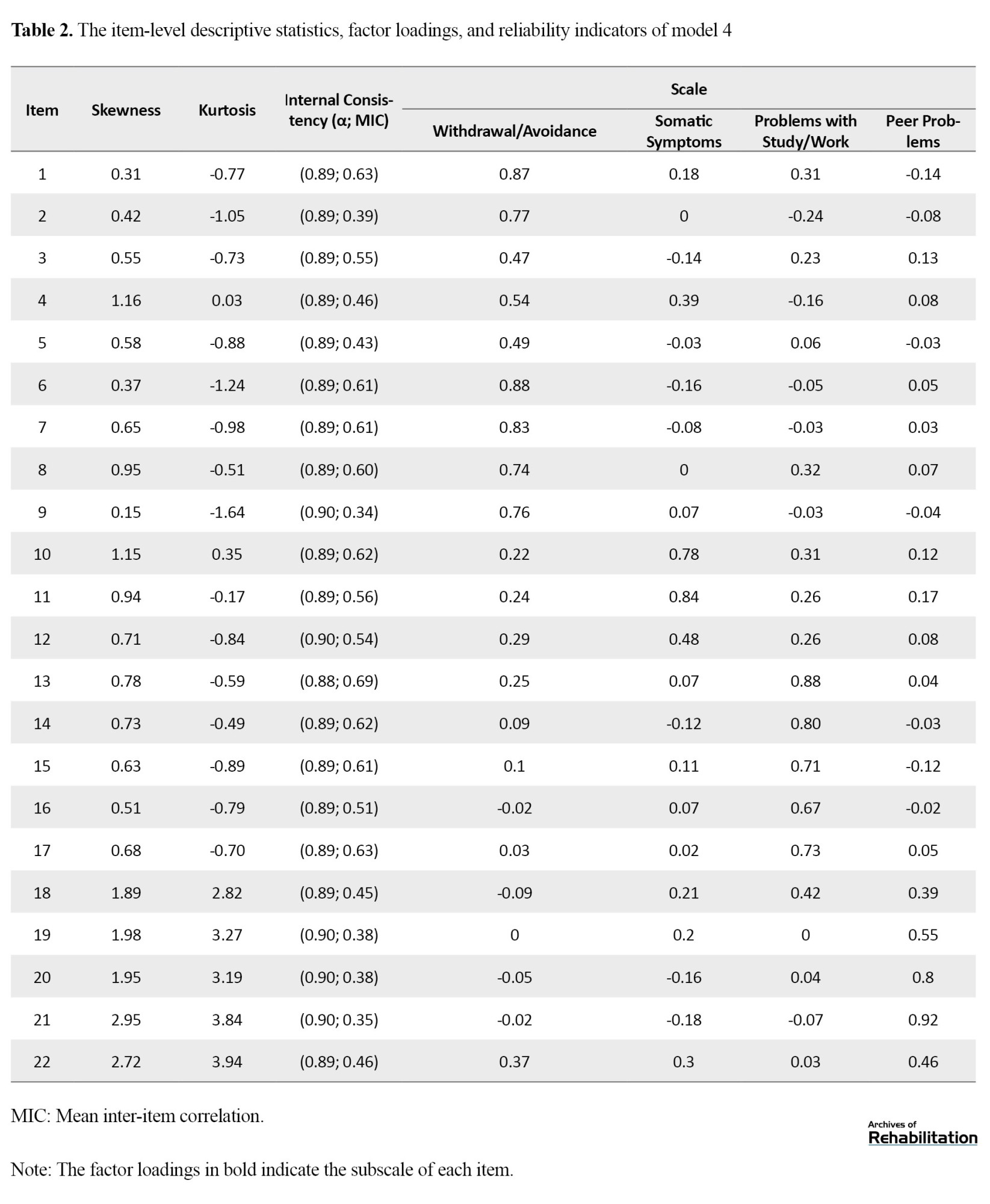

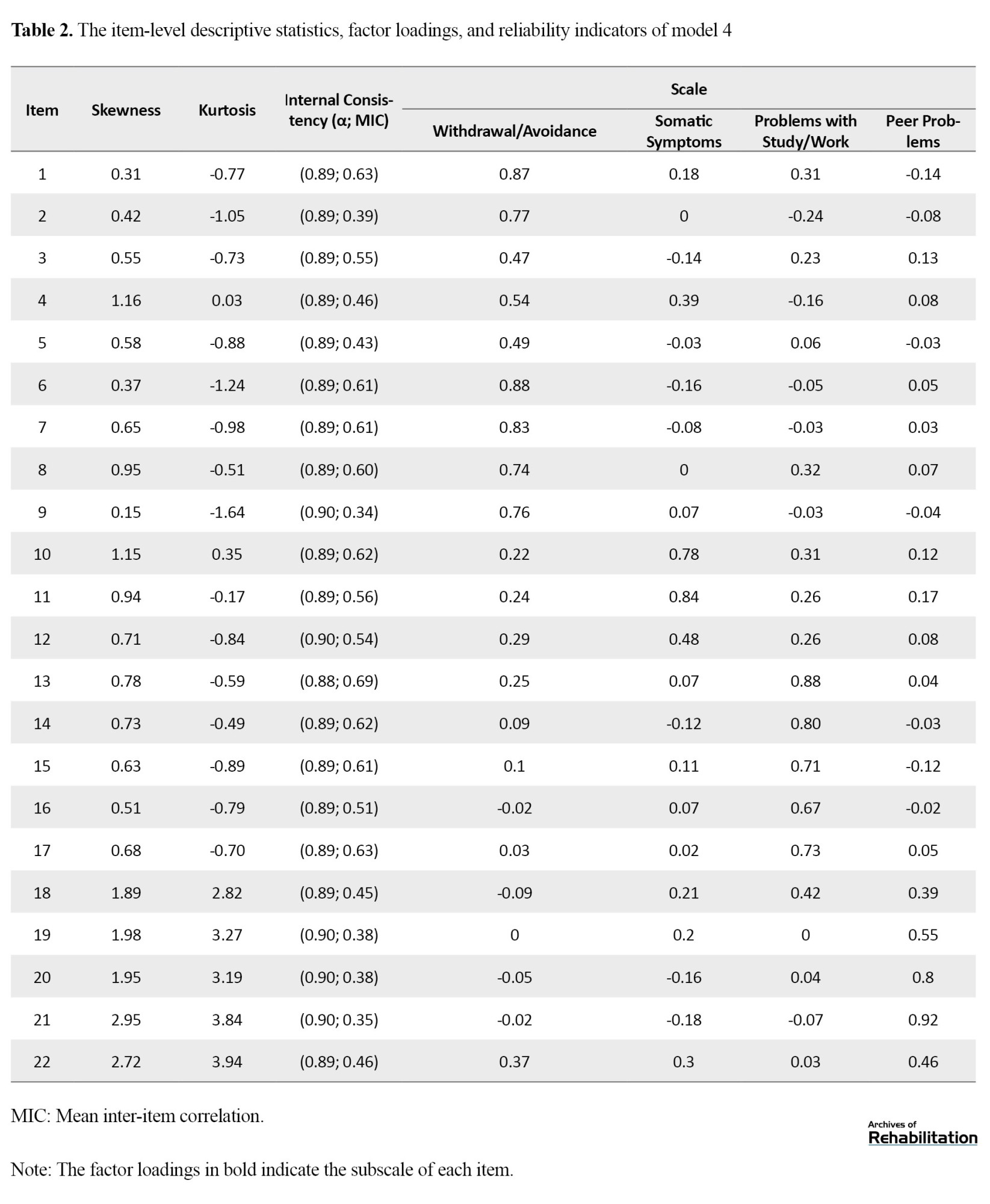

Table 2 presents the ESEM analysis for the ALIS-I subscales. As can be seen, the data distribution of most of the items was normal. In addition, as expected, all items were well loaded on the intended factor. Items 1-9 had the highest factor loading on the withdrawal/avoidance subscale, followed by items 10-12 on the somatic symptoms subscale, items 13-18 on the problems with study/work subscale, and items 19-22 on the peer problems subscale. All loadings were >0.4. Based on the ESEM approach, some items (e.g. 1, 10, and 22) shared more than one factor. There was also an acceptable correlation (>0.3) between all items and the total score.

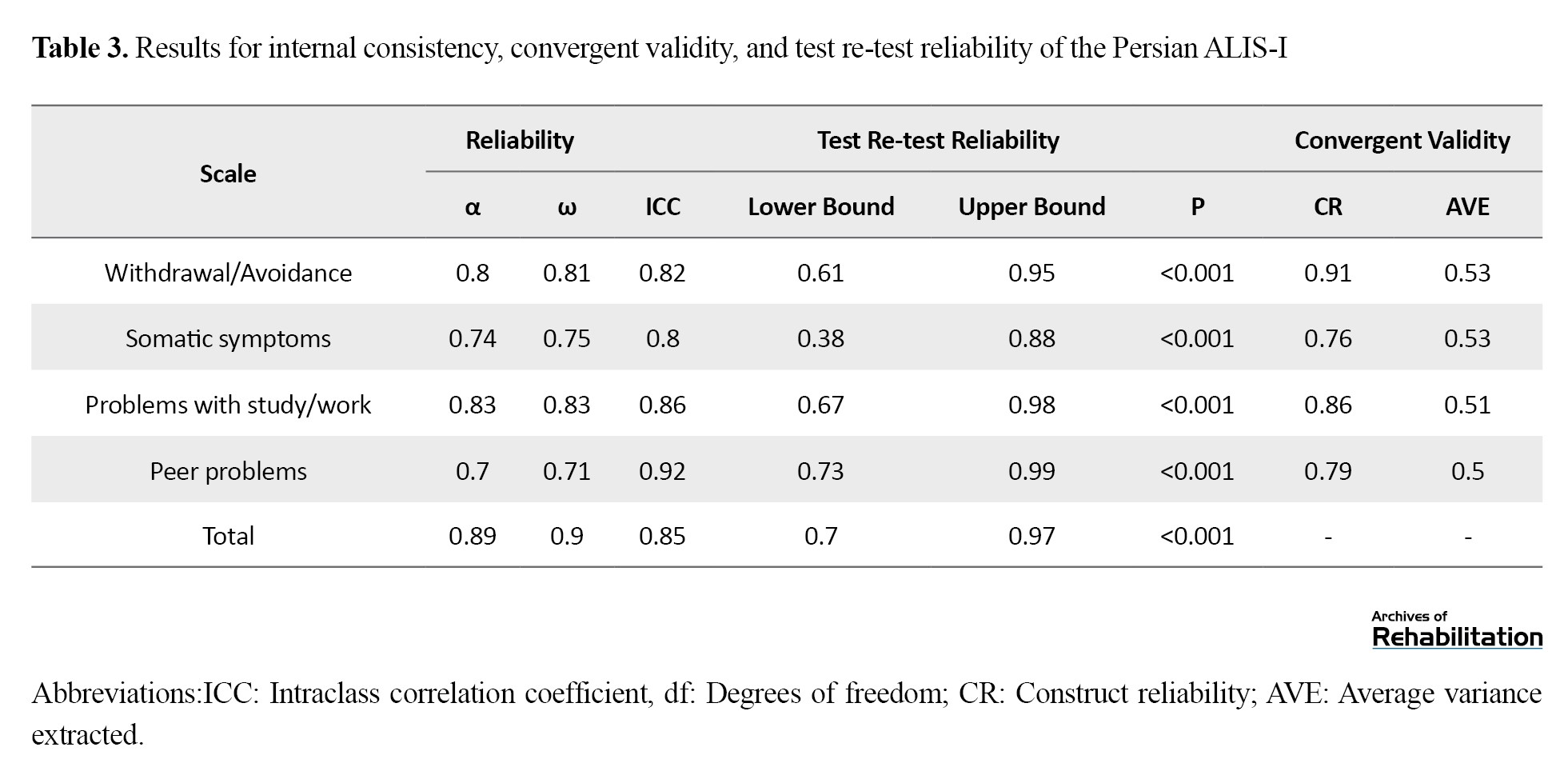

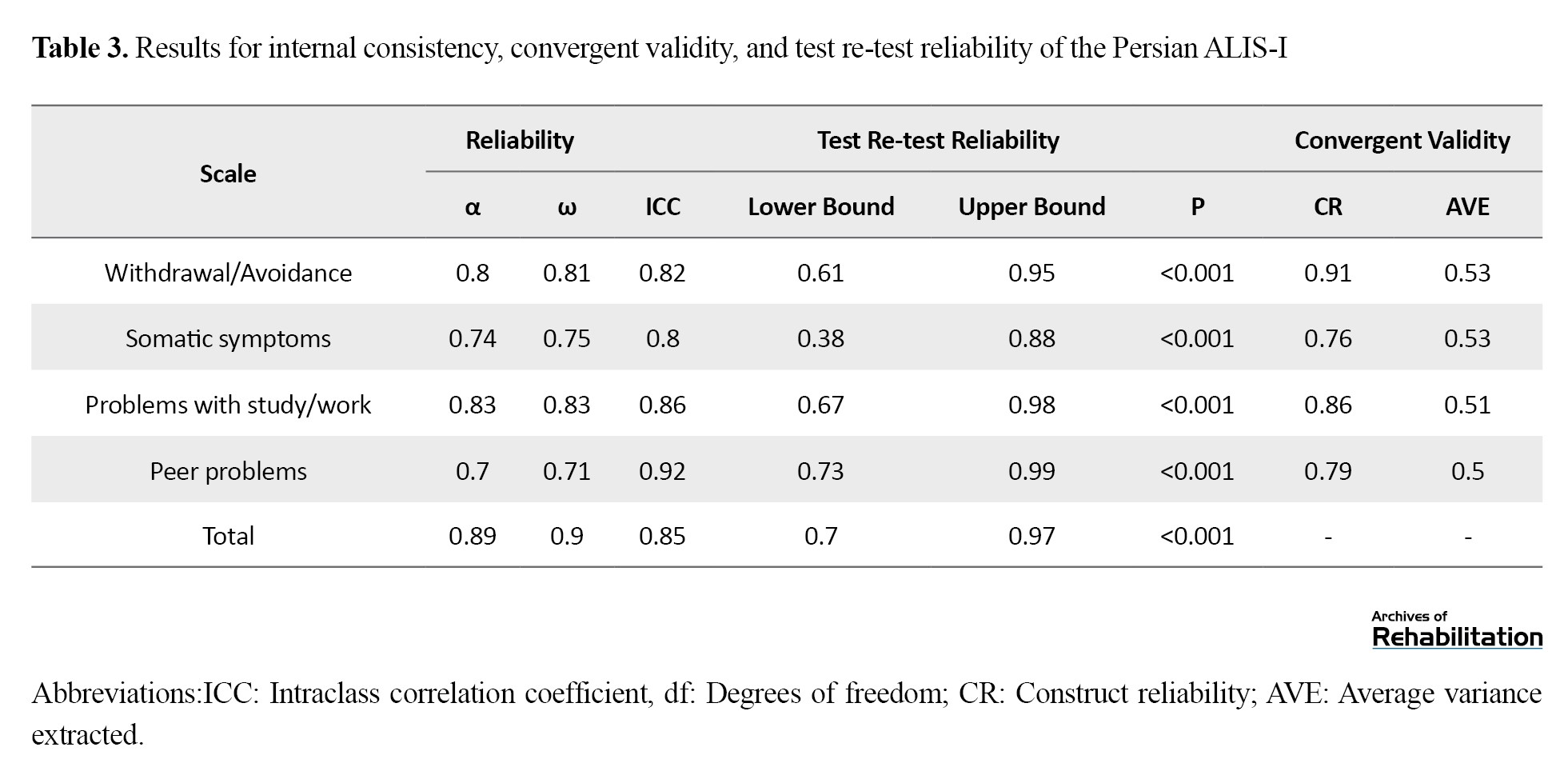

The results in Table 3 showed that Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s omega for the total scale and its subscales were >0.70, indicating that the internal consistency of the Persian ALIS-I was acceptable.

The ICCs were >0.80 for the total scale and its subscales, showing that the ALIS-I had acceptable test re-test reliability. There was also a moderate to strong correlation between the subscales of the ALIS-I.

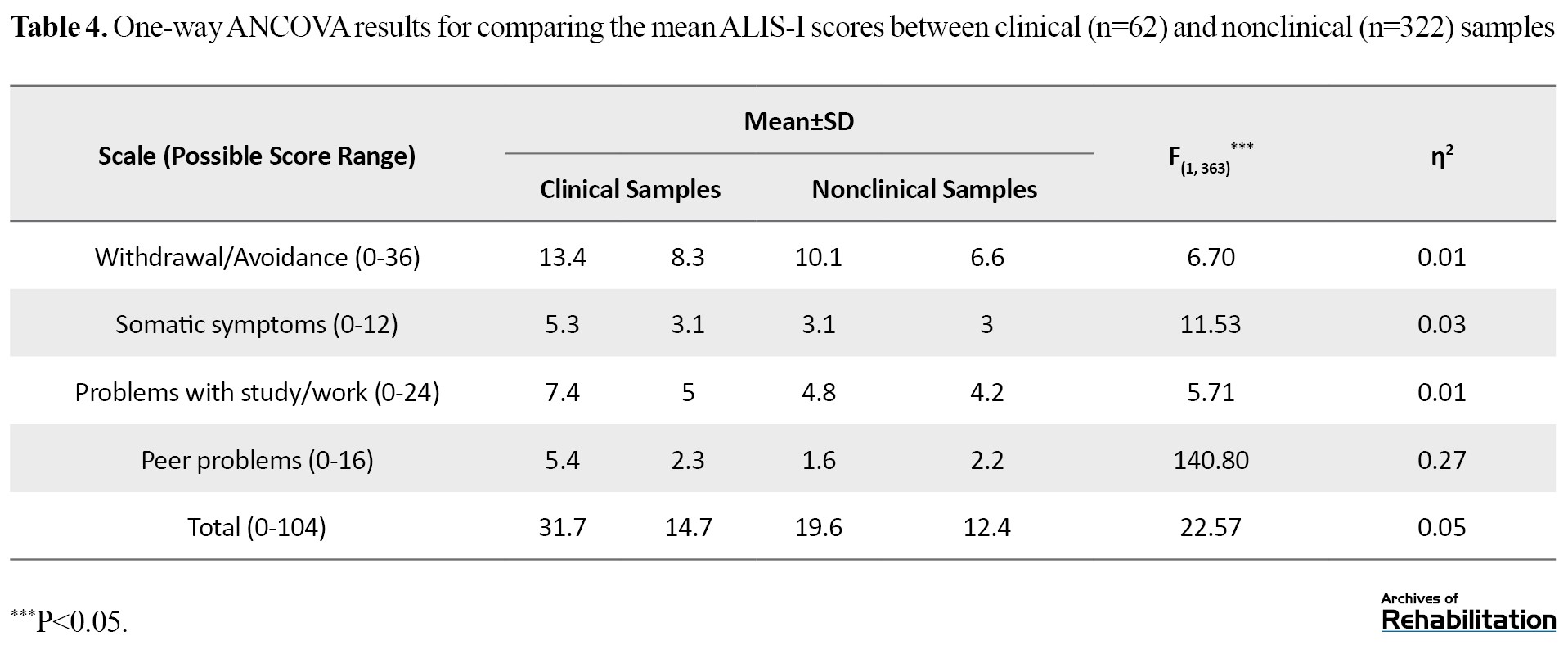

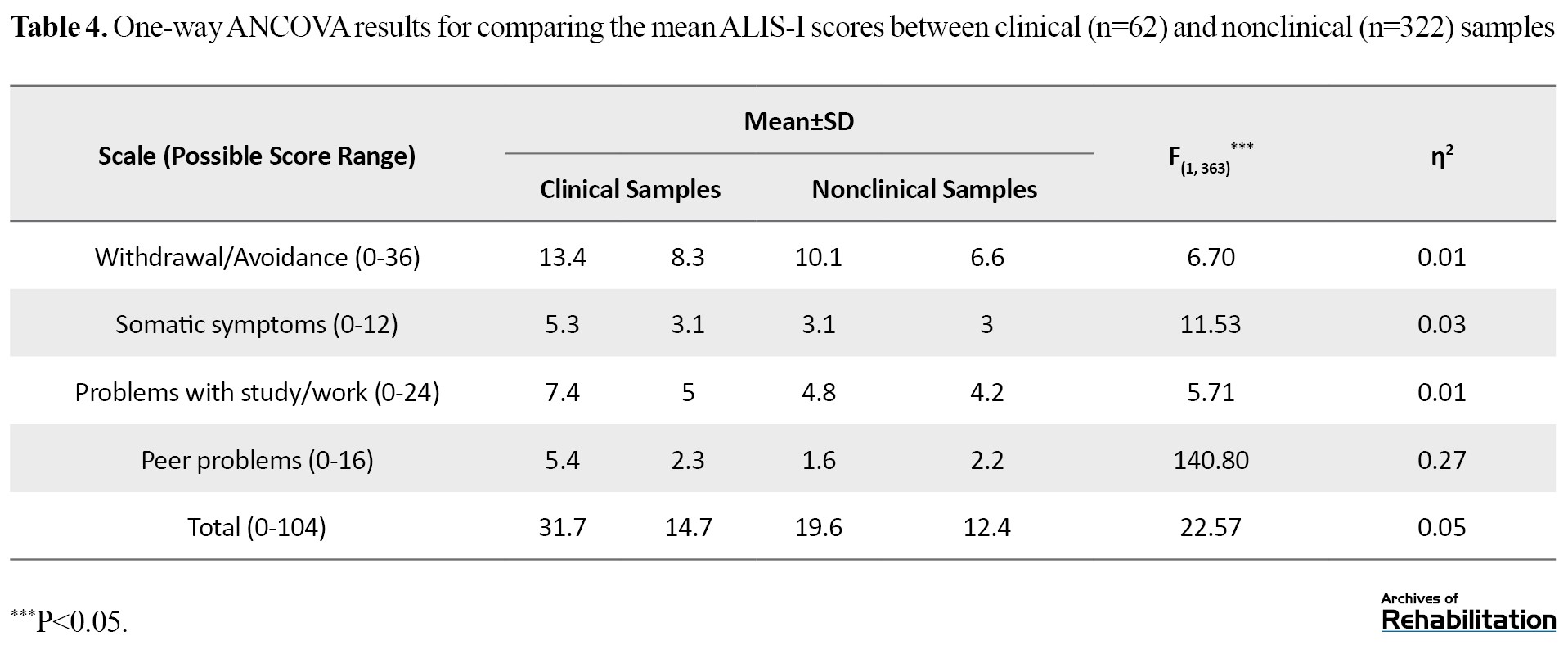

In assessing the divergent validity, one-way ANCOVA was used to compare the ALIS-I means of clinical and non-clinical samples, while controlling for age, sex, and field of study (Table 4).

The results showed that the mean scores of the ALIS-I and its subscales in the clinical group were significantly higher compared to the normal group (P<.001). Convergent validity was checked based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion and by measuring the correlation between the Persian ALIS-I and EASI-A scores. Based on the results in Table 3, AVE>0.5, CR>0.7, and CR>AVE for all subscales of the ALIS-I. Moreover, the total ALIS-I (r=0.85, P<0.001) and its subscales, including withdrawal/avoidance (r=0.45, P<0.001), somatic symptoms (r=0.71, P<0.001), problems with study/work (r=0.53, P<0.001), and peer problems (r=0.41, P<0.001), had significant positive correlations with the EASI-A score. Therefore, the convergent validity of the ALIS-I was acceptable.

Comparisons of clinical samples by age and sex were conducted using simple linear regression analysis and independent t-test. Regarding age, the mean total score of the Persian ALIS-I was higher in adolescents aged 14-16 years than in adolescents aged 11-13 years, and its effect size was moderate (B=10.58, P=0.005, ƞ2=0.16). Furthermore, the mean scores of the withdrawal/avoidance (B=2.50, P<0.001, ƞ2=0.21), somatic symptoms (B=2.84, P<0.001, ƞ2=0.25), problems with study/work (B=3.46, P=0.013, ƞ2=0.13), and peer problems (B=1.79, P=0.002, ƞ2=0.19) subscales were higher in adolescents aged 14-16 years than in those aged 11-13 years, with moderate effect sizes. Regarding sex differences, the mean total score of ALIS-I (d=0.21, 95% CI, 0.02%, 0.63%) and the score of the subscale problems with study/work (d=0.12, 95% CI, -0.05%, 0.34%) were higher in females than in males, and their effect size was moderate. In other subscales, the results revealed no significant difference (P>0.05).

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the ALIS-I for Iranian adolescents. Results demonstrated that the Persian ALIS had suitable psychometric properties (construct validity, divergent validity, convergent validity, and reliability). The study showed that the first-order four-factor ESEM model of the ALIS-I, in which four factors were estimated as distinct and related first-order factors, had a good fit. This model takes general and specific factors into account, reflecting the original four dimensions of the ALIS-I, and the same items are loaded on each dimension. The factor structure of the Persian ALIS-I is consistent with the results for the original version of the ALIS-I. There was an acceptable correlation between all items and the total score of the Persian ALIS-I, leading to strong internal consistency for the overall scale (α=0.89), consistent with the original version [7].

The mean total score of the ALIS-I was higher in clinical samples aged 14-16 years than in those aged 11-13, with a moderate effect size. A similar difference was found regarding its four subscales. This finding is consistent with the results of Schniering et al.’s study, in which older adolescents reported significantly higher ALIS-I total scores compared to younger adolescents [7]. Other studies on the life interference related to anxiety and depression in adolescents have reported similar results, generally showing that the effects of these disorders on life increase with age [43-45]. These findings are also consistent with studies on nonclinical populations in Iran showing an inverse relationship between functioning and age in adolescents [28, 46]. In explaining these findings, it can be said that academic and social expectations increase with age during adolescence. Therefore, the symptoms of mental disorders are likely to yield different consequences depending on the age. For example, symptoms of social anxiety disorder in young children who are not yet required to engage in regular peer relationships tend to cause less interference than in adolescents, whose social interactions are more complex. Exam anxiety also becomes increasingly disruptive as academic pressures increase [14]. This is also true for the effects of depression on the social relationships of adolescents. With the increase of age, a decrease in reliance on family, and becoming more independent, and given the increasing importance of peer groups, interference due to internalizing distress becomes higher [7]. In Iran, to our knowledge, there is no study on the relationship between age and functional impairment caused by anxiety and depression in adolescents, to compare the results. Further research is necessary in this field.

The mean total score of the ALIS-I and its subscales of problems with study/work were higher in female clinical samples than in males, with a moderate effect size. This finding contradicts the results of Schniering et al.’s study, in which female participants reported slightly higher mean scores than the male participants; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.061) and the effect size was small (d=0.25). In their study, the female participants had higher mean scores in the somatic symptoms subscale than in male participants. In other subscales, the difference was statistically nonsignificant [7]. Our findings is consistent with the results of study in 2010 on Iranian adolescents, in which adolescent females had lower total functioning scores than boys [47]. Conversely, in Hadianfard et al.’s study, the general functioning of male adolescents (including physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, school functioning, and psychosocial health) was significantly higher than that of girls. However, no significant difference was observed in school functioning [46]. Our result is also against the results of the study by Ghahremani et al., where, using the Mental Health and Social Inadaptation questionnaire, interference caused by anxiety, depression, eating disorder and behavioral problems in adolescents was investigated and no difference in interference between girls and boys was found [48]. In another study conducted on nonclinical adolescents, males had higher impairment than females in domains of work, school, social activities, and risky activities, although the overall impairment score was not significantly different between males and females [46]. The discrepancy in results may be due to cross-cultural differences. In Iran, during the past years, many steps have been taken towards gender equality in education, and the gender equality index (GPI) value has increased, especially in secondary schools. In addition, the literacy rate of teenage girls has increased [49, 50]; since 2011, females’ entry to universities in Iran has outnumbered males [51]. These statistics show that adolescent girls in Iran give more attention to education than boys; therefore, probably, the girls with anxiety or depression suffer from academic failure more than boys. In general, the literature on sex differences of functional impairment in adolescents is very mixed and there are few consistent patterns. Therefore, there is a need for more research to draw definite conclusions, especially for Iranian adolescents.

Conclusion

The Persian ALIS-I has excellent structural validity and reliability and can be used to evaluate Iranian adolescents’ functional impairment. Thus, clinical psychologists in Iran can confidently use the Persian version of the ALIS to assess the degree of functional impairment in adolescents caused by anxiety and depression in different social contexts.

Despite the promising results, this study has certain limitations. Since the participants came from different cities in Iran, further research is required before the results can be generalized to the entire Iranian population. Participation in the study was fully online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have introduced biases such as self-selection (participants choosing to complete the survey), undercoverage (limited internet access in the target population), and voluntary response (responses mainly from self-selected volunteers). Consequently, the generalization of the findings is limited to Iranian adolescents who attended the selected high schools in the mentioned cities and had internet access. There were also demographic differences between the clinical and non-clinical groups, which should be considered when interpreting the results. Therefore, additional research involving a broader range of adolescents from Iran or other countries is essential. Moreover, the ALIS-I is recommended for use in experimental studies to further examine its functional validity.

Limitations and recommendations

Despite the promising results, this study has certain limitations. Since the participants came from different cities in Iran, further research is required before the results can be generalized to the entire Iranian population. Participation in the study was fully online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may cause self-selection bias (the participant is informed about the survey and decides to complete the survey), undercoverage bias (whether the target population has internet access), voluntary response bias (when the sample consists of self-selected volunteers). The generalization of the findings is thus limited to Iranian adolescents who attended the selected high schools in the mentioned cities and had access to the internet. There were demographic differences between the two clinical and non-clinical groups, which should be taken into account when interpreting the study’s results. Therefore, conducting further research involving a wider range of adolescents from Iran or other countries seems essential. The ALIS-I is also recommended to be used in experimental studies to determine its functional validity.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.167). All procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical principles. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the research. They had the right to leave the study at any time and were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This study was extracted from the dissertation of Nasim Mousavi, at the Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Abbas Pourshahbaz and Nasim Mousavi; Investigation and writing the original draft: Nasim Mousavi; Review and editing: Hamid Poursharifi, Abbas Pourshahbaz, Fereshteh Momeni, and Ronald Rapee.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Omid Rezaee, Mr. Reza Araei, and Dr. Marzieh Norozpour for their contributions to this research as well as all participants for their cooperation.

Anxiety and depressive disorders are common during adolescence [1]. A national study conducted in Iran on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among children and adolescents showed that 14.13% of participants aged 6-18 years had anxiety disorders and 2.15% had a mood disorder [2]. Following the emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic, an increasing trend in the incidence of mental health-related problems in this age group was observed [3]. Adolescents diagnosed with mood and/or anxiety disorders are at a higher risk of experiencing mental health problems in adulthood, academic failure, and communication problems compared to their healthy peers [4]. These disorders lead to increased use of governmental healthcare services and reduced participation in the labor market. The physical health and quality of life of adults who have suffered from these disorders during adolescence are also lower than those of other people [5].

Comorbidity between anxiety and depressive disorders is higher in adolescence [6], compared to childhood [7]. In Iran, the comorbidity is greater than 50% among individuals aged 6-18 years [2]. Adolescents with comorbid depression and anxiety exhibit greater impairments than those diagnosed with either of them, and their treatment is also more difficult [8-10]. Common cognitive, behavioral, and emotion regulation processes in anxiety and depressive disorders that can be targeted for treatment are of great importance [11, 12]. However, adults usually underestimate the severity of these disorders in their adolescent children and interpret their symptoms as a mere transitional phase. Consequently, the majority of these adolescents do not receive any treatment [13]. Therefore, acquiring a deep understanding of these disorders and their impact on adolescents is necessary, and appropriate instruments tailored to adolescents are required for this purpose.

One of the important aspects in the study of anxiety and depressive disorders is functional impairment. It represents a key aspect of mental health in adolescents and offers valuable insight into the severity of anxiety and depressive symptoms, which is a key factor in clinical assessments and treatment planning. Early identification and treatment of functional impairments can prevent the persistence of these disorders in adulthood [7, 14]. Functional impairment refers to specific limitations in various functional domains in daily life that are caused by a disorder. These domains include cognitive abilities, academic or occupational performance, interpersonal relationships, age-appropriate self-care capacity, and the capacity to enjoy life, which includes the use of leisure time for self-fulfillment [15, 16]. By assessing functional impairment, the impact of an individual’s symptoms on the level of impairment can be examined, or the improvement in performance resulting from psychological interventions can be measured [17, 18].

Despite the importance of this issue in research and clinical practice, the development of measurement instruments for functional impairment is limited. This limitation is even more evident for adolescents [7]. Although instruments such as the Child Activity Limitations Interview [19], Functional Disability Inventory [20] and Functional Status Inventory [16] have been developed for this purpose, they are not specific to adolescents and can also be used for children. The age-specific instruments for measuring functional impairment in adolescents should be designed to capture the challenges that adolescents face during adolescence. This period is characterized by rapid changes in cognitive, emotional, and social functioning, many of which differ significantly from those of children and adults [21-23]. For example, adolescents with psychiatric disorders use avoidance strategies more than children. Higher use of avoidance is associated with a greater level of impairment [14, 24]. Relationships with peers play a key role in the lives of adolescents, and their importance for adolescents is more than for children or adults. Any effect on peer relationships can influence adolescents’ functioning [21]. Hence, it is essential to utilize specialized instruments tailored to this age group. For this purpose, Schniering et al. [7] developed the adolescent life interference scale for internalizing symptoms (ALIS-I). While this measure has shown promise for adolescents from Australia and the United States, it is important to evaluate its psychometric properties for other countries with different cultures. The nature and extent of functional impairment vary from culture to culture. Even basic language differences can influence the responses or may affect the nuances of item interpretation [25-27].

Previous studies have suggested that Iranian adolescents have high functional impairment. For example, Hadianfard et al. showed that 29.5% of Iranian adolescents had significant deficits in domains such as life and school skills [28]. However, to date, no self-report tool has been specifically designed to assess the functional impairment and interference of anxiety and depression symptoms in Iranian adolescents. Considering the high prevalence of anxiety and depressive disorders in Iranian adolescents, a standardized tool is required to investigate the complications of depression and anxiety symptoms in this group. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the ALIS-I for examining functional impairment and life interference related to anxiety and depression in Iranian adolescents.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This is a descriptive and psychometric study that was conducted in 2022. Participants were adolescents aged 11-18 from different cities in Iran. According to Kline, a sample size of at least 5-20 is needed for each parameter or item in structural equation models [29]. As the ALIS-I had 26 items, 130-520 samples were required. In this regard, 384 adolescents were included in this study with a mean age of 15.54±1.62 years: 322 nonclinical samples (83.8%) and 62 clinical samples (16.2%). Sampling was done using a convenience sampling method. The clinical samples were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: Age 11-18 years and the diagnosis of depression or anxiety disorders based on the structured clinical interview for DSM-5 (SCID-5) held by the research team. The comorbid psychiatric problems (e.g. eating disorders, disruptive behavior disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and substance abuse) were accepted in the clinical samples only if anxiety or depression were the main complaint. The exclusion criteria for clinical samples were comorbid bipolar or psychotic disorder.

For selecting clinical samples, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, invitation was done online by sending links or designed posters on popular social networks (Instagram, WhatsApp, and Telegram) to adolescents with self-reported symptoms of anxiety or depression from all over the country, or asking adolescent psychologists to introduce their adolescent clients suffering from anxiety and/or depression. After all volunteers had contacted the researcher, they were asked questions during a phone call to verify the inclusion and exclusion criteria and underwent the SCID-5. After checking the criteria, a link containing consent forms and questionnaires was sent to these samples. The online survey link was generated on the Porsline website.

For selecting nonclinical samples, another invitation poster was designed. To encourage participation in the study, a free internet package was offered by lottery to 20 participants. Nonclinical participants were excluded if they had visited a psychiatrist or psychologist in the last three months for the treatment of any anxiety, depression, bipolar, substance abuse, or psychotic disorder, or were currently taking psychotropic medication.

Translation and cross-cultural adaptation

Permission for the translation and psychometric assessment of the ALIS-I was first obtained from the developer of the ALIS-I. The translation and cross-cultural adaptation were then carried out in five steps using Beaton et al.’s method [30]. Two native Persian speakers, each with fluency in English (one was a PhD candidate in clinical psychology and the other was an adolescent psychotherapist), conducted the English-to-Persian translation separately. Two translated drafts in Persian were merged to develop a single draft. This was translated back into English by two other translators with master’s degrees in English literature, with no background in psychology. A statistician was also invited to supervise the translation and cultural adaptation process. After comparing the Persian and English drafts, the final draft in Persian was prepared and approved by all authors. Before using the scale, it was presented to 30 adolescents (19 girls and 11 boys, aged 11-18 years) residing in Tehran, Iran, and they were asked to answer the items online. They were encouraged to mark any item that was unclear to them. Then, the draft was modified based on their comments, and the final Persian version was developed (Appendix 1).

The feedback showed that the sentences were meaningful, and no changes were needed in any items

Measures

SCID-5

The SCID-5 is a semi-structured interview for the diagnosis of mental disorders according to the DSM-5 criteria. This tool is administered by a trained clinical psychologist familiar with the diagnostic criteria and classification of DSM-5 disorders. The diagnostic coverage and the language used in the SCID-5 make it suitable for people over age 18 years, and with a brief rewording of the questions, the tool can also be used for adolescents [31].

ALIS-I

The ALIS-I is a 26-item self-report tool developed by Schniering et al. [7] to evaluate the extent of functional impairment across various social contexts (i.e. school performance, sports, and peers/family) over the past month. It is a reliable and valid tool for clinical and nonclinical samples aged 11-18. It has four subscales representing common areas of life interference frequently reported by this age group: Withdrawal/avoidance (9 items), somatic symptoms (3 items), problems with study/work (6 items), and peer problems (4 items). The other four items are not related to any of these subscales. The responses are rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (all the time). The overall scale has high internal consistency (α=0.94). The Cronbach’s α values for the subscales were: 0.91 for withdrawal/avoidance, 0.76 for somatic symptoms, 0.86 for problems with study/work, and 0.81for peer problems. In this scale, higher scores indicate greater life interference [7].

The emotional avoidance strategy inventory for adolescents (EASI-A)

The EASI-A is a self-report inventory developed by Kennedy and Ehrenreich-May in 2017 [32] to assess emotional avoidance. This tool has 33 items rated on a Likert scale from 0 (not at all true of me) to 4 (extremely true of me). It has three subscales, including “avoidance of thoughts and feelings” (e.g. “I do whatever I can to avoid feeling sad or worried or afraid”), “avoidance of emotion expression” (e.g. “I have a hard time showing my true feelings”), and “active avoidance coping” (e.g. “I prefer to keep conversations happy or light.”). The EASI-A has high validity and reliability for children and adolescents [32]. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of this inventory were assessed and confirmed by Mousavi et al. They reported a Cronbach’s α of 0.71 for its reliability [33].

Psychometric assessments

Construct validity

To assess the factor structure of the Persian ALIS-I, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the weighted least squares mean and variance (WLSMV) estimation [34] in Mplus software, version 7.11. This estimation method yields more precise results for categorical data compared to the traditional maximum likelihood approach [35]. Target rotation was used in the structural equation modeling (SEM) due to the confirmatory approach of the models. A two-step approach was employed to identify the model that best fits the data, and the chi-square (χ2), Tucker‒Lewis index (TLI), weighted root mean square residual (WRMR), comparative fit index (CFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) results were then compared. The models were considered fit based on the recommendations proposed by Hu and Bentler: CFI >0.90, GFI >0.9, RMSEA <0.08 as good and <0.1 as acceptable, TLI >0.9, and WRMR <0.08 [36]. To choose the most suitable structure for the Persian version of the ALIS-I, five models were considered as follows: (a) Unidimensional model: each item is loaded on a single factor, (b) First-order four-factor model: This model was selected based on the original version. Items 1-9 were loaded on withdrawal/avoidance, items 10-12 on somatic symptoms, item 13-18 on problems with study/work, and items 19-22 on peer problems, (c) Higher-order or second-order four-factor model: In this model, the four first-order factors were loaded on a higher-order factor called ALIS-I, (d) Bifactor model: In this model, ALIS-I was considered a general factor independent of the four specific factors. The bifactor model offers an alternative to the traditional higher-order factorial model by allowing items to simultaneously load on a “general” factor as well as on four specific factors. These specific factors reflect the unique variance shared among the items making up the four subscales – that is, the variance that the general factor cannot explain. (d) First-order four-factor exploratory SEM (ESEM): In this model, the four factors were estimated as distinct yet correlated first-order factors. In hierarchically organized constructs such as those in ALIS-I, these first-order ESEMs likely overlook the presence of a hierarchically superior construct, which may instead be expressed through hyper inflated cross-loadings [37]. Asparouhov and Muthén, by proposing the ESEM method, claimed that this method integrates the strengths of exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, regardless of their limitations [38]. ESEM, like exploratory factor analysis (EFA), permits items to load on all factors simultaneously. On the other hand, this method has all the advantages of CFA, such as the ability to calculate standard errors and the measurement invariance test [38, 39]. Also, it should be noted that no missing data or unengaged response patterns was found.

Reliability

Internal consistency was determined by calculating Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s omega. Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s omega values equal to or higher than 0.70 were considered acceptable. To assess the test re-test reliability, 30 clinical samples completed the ALIS-I at a three-week interval. Then, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated. The two-way random model with the absolute agreement approach was used to examine the ICC. An ICC in the range of 0.40-0.59 indicates fair, 0.60-0.75 good, and ≥0.76 excellent reliability [40].

Convergent and divergent validity

The average variance extracted (AVE) based on Fornell-Larcker criterion and Pearson’s correlation test (to assess the relationship between the ALIS-I and EASI-A scores) were used to evaluate convergent validity [41]. Acceptable values for convergent validity were: AVE>0.5, CR>0.7, and CR>AVE. To examine divergent validity, scores on the ALIS-I and its subscales were compared between the clinical and nonclinical samples using the independent t-test.

Data analysis

Descriptive and correlational analyses were performed in the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS) software, version 27, and MacDonald’s omega coefficient for reliability estimation was calculated in the SPSS OMEGA macro.

Results

The nonclinical samples included 170(52.8%) females and 152(47.2%) males. Their mean age was 15.78±1.43 years. Their field of study was mathematics & physics (n=150, 46.6%), technical and vocational sciences (n=73, 22.7%), experimental sciences (n=58, 18%), or humanities (n=41, 12.7%). The educational level of their fathers was a high school diploma (n=124, 38.5%), a bachelor’s degree (n=78, 24.2%), lower than a high school education (n=69, 21.4%), or a master’s degree or higher (n=51, 15.9%). The clinical samples included 52(83.9%) females and 10(16.1%) males. Their mean age was 14.16±1.92 years. Their field of study was technical and vocational sciences (n=19, 30.6%), experimental sciences (n=19, 30.6%), humanities (n=18, 29%), or mathematics & physics (n=6, 9.7%). The educational level of their fathers was a high-school diploma (n=22, 35.5%), a bachelor’s degree (n=17, 27.4%), a master’s degree or higher (n=11, 19.7%), or lower than a high school education (n=12, 19.4%).

Table 1 presents the fit indices of the five proposed models.

The single-factor model (model 0) had a poor fit. Considering CFI>0.9 and RMSEA<0.1, the four-factor (model 1) and second-order CFA models (model 2) had a relatively good fit. The bifactor model (model 3) and ESEM model (model 4) were then analyzed. The fit indices showed that these two models fit the data very well. Then, the single-factor model was taken as a reference, and the other models were compared to it. Table 2 shows that the ∆CFI and ∆RMSEA of models 1 to 4 were greater than 0.01, indicating a better fit of these models compared to the single-factor model [42].

The Model 4 demonstrated a significantly better fit to the data compared to Model 3 (∆χ2=78.7; ∆df=38; P <0.001; ∆CFI=0.01; ∆TLI=0.001; ∆RMSEA=0.001; ∆WRMR=0.226), Model 2 (∆χ2=103.88; ∆df=56; P<0.001; ∆CFI=0.058; ∆TLI=0.049; ∆RMSEA=0.021; ∆WRMR=0.38), and Model 1 (∆χ2=97.96; ∆df=54; P<0.001; ∆CFI=0.056; ∆TLI=0.048; ∆RMSEA=0.021; ∆WRMR=0.37).

Table 2 presents the ESEM analysis for the ALIS-I subscales. As can be seen, the data distribution of most of the items was normal. In addition, as expected, all items were well loaded on the intended factor. Items 1-9 had the highest factor loading on the withdrawal/avoidance subscale, followed by items 10-12 on the somatic symptoms subscale, items 13-18 on the problems with study/work subscale, and items 19-22 on the peer problems subscale. All loadings were >0.4. Based on the ESEM approach, some items (e.g. 1, 10, and 22) shared more than one factor. There was also an acceptable correlation (>0.3) between all items and the total score.

The results in Table 3 showed that Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s omega for the total scale and its subscales were >0.70, indicating that the internal consistency of the Persian ALIS-I was acceptable.

The ICCs were >0.80 for the total scale and its subscales, showing that the ALIS-I had acceptable test re-test reliability. There was also a moderate to strong correlation between the subscales of the ALIS-I.

In assessing the divergent validity, one-way ANCOVA was used to compare the ALIS-I means of clinical and non-clinical samples, while controlling for age, sex, and field of study (Table 4).

The results showed that the mean scores of the ALIS-I and its subscales in the clinical group were significantly higher compared to the normal group (P<.001). Convergent validity was checked based on the Fornell-Larcker criterion and by measuring the correlation between the Persian ALIS-I and EASI-A scores. Based on the results in Table 3, AVE>0.5, CR>0.7, and CR>AVE for all subscales of the ALIS-I. Moreover, the total ALIS-I (r=0.85, P<0.001) and its subscales, including withdrawal/avoidance (r=0.45, P<0.001), somatic symptoms (r=0.71, P<0.001), problems with study/work (r=0.53, P<0.001), and peer problems (r=0.41, P<0.001), had significant positive correlations with the EASI-A score. Therefore, the convergent validity of the ALIS-I was acceptable.

Comparisons of clinical samples by age and sex were conducted using simple linear regression analysis and independent t-test. Regarding age, the mean total score of the Persian ALIS-I was higher in adolescents aged 14-16 years than in adolescents aged 11-13 years, and its effect size was moderate (B=10.58, P=0.005, ƞ2=0.16). Furthermore, the mean scores of the withdrawal/avoidance (B=2.50, P<0.001, ƞ2=0.21), somatic symptoms (B=2.84, P<0.001, ƞ2=0.25), problems with study/work (B=3.46, P=0.013, ƞ2=0.13), and peer problems (B=1.79, P=0.002, ƞ2=0.19) subscales were higher in adolescents aged 14-16 years than in those aged 11-13 years, with moderate effect sizes. Regarding sex differences, the mean total score of ALIS-I (d=0.21, 95% CI, 0.02%, 0.63%) and the score of the subscale problems with study/work (d=0.12, 95% CI, -0.05%, 0.34%) were higher in females than in males, and their effect size was moderate. In other subscales, the results revealed no significant difference (P>0.05).

Discussion

This is the first study to investigate the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the ALIS-I for Iranian adolescents. Results demonstrated that the Persian ALIS had suitable psychometric properties (construct validity, divergent validity, convergent validity, and reliability). The study showed that the first-order four-factor ESEM model of the ALIS-I, in which four factors were estimated as distinct and related first-order factors, had a good fit. This model takes general and specific factors into account, reflecting the original four dimensions of the ALIS-I, and the same items are loaded on each dimension. The factor structure of the Persian ALIS-I is consistent with the results for the original version of the ALIS-I. There was an acceptable correlation between all items and the total score of the Persian ALIS-I, leading to strong internal consistency for the overall scale (α=0.89), consistent with the original version [7].

The mean total score of the ALIS-I was higher in clinical samples aged 14-16 years than in those aged 11-13, with a moderate effect size. A similar difference was found regarding its four subscales. This finding is consistent with the results of Schniering et al.’s study, in which older adolescents reported significantly higher ALIS-I total scores compared to younger adolescents [7]. Other studies on the life interference related to anxiety and depression in adolescents have reported similar results, generally showing that the effects of these disorders on life increase with age [43-45]. These findings are also consistent with studies on nonclinical populations in Iran showing an inverse relationship between functioning and age in adolescents [28, 46]. In explaining these findings, it can be said that academic and social expectations increase with age during adolescence. Therefore, the symptoms of mental disorders are likely to yield different consequences depending on the age. For example, symptoms of social anxiety disorder in young children who are not yet required to engage in regular peer relationships tend to cause less interference than in adolescents, whose social interactions are more complex. Exam anxiety also becomes increasingly disruptive as academic pressures increase [14]. This is also true for the effects of depression on the social relationships of adolescents. With the increase of age, a decrease in reliance on family, and becoming more independent, and given the increasing importance of peer groups, interference due to internalizing distress becomes higher [7]. In Iran, to our knowledge, there is no study on the relationship between age and functional impairment caused by anxiety and depression in adolescents, to compare the results. Further research is necessary in this field.

The mean total score of the ALIS-I and its subscales of problems with study/work were higher in female clinical samples than in males, with a moderate effect size. This finding contradicts the results of Schniering et al.’s study, in which female participants reported slightly higher mean scores than the male participants; however, the difference was not statistically significant (P=0.061) and the effect size was small (d=0.25). In their study, the female participants had higher mean scores in the somatic symptoms subscale than in male participants. In other subscales, the difference was statistically nonsignificant [7]. Our findings is consistent with the results of study in 2010 on Iranian adolescents, in which adolescent females had lower total functioning scores than boys [47]. Conversely, in Hadianfard et al.’s study, the general functioning of male adolescents (including physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, school functioning, and psychosocial health) was significantly higher than that of girls. However, no significant difference was observed in school functioning [46]. Our result is also against the results of the study by Ghahremani et al., where, using the Mental Health and Social Inadaptation questionnaire, interference caused by anxiety, depression, eating disorder and behavioral problems in adolescents was investigated and no difference in interference between girls and boys was found [48]. In another study conducted on nonclinical adolescents, males had higher impairment than females in domains of work, school, social activities, and risky activities, although the overall impairment score was not significantly different between males and females [46]. The discrepancy in results may be due to cross-cultural differences. In Iran, during the past years, many steps have been taken towards gender equality in education, and the gender equality index (GPI) value has increased, especially in secondary schools. In addition, the literacy rate of teenage girls has increased [49, 50]; since 2011, females’ entry to universities in Iran has outnumbered males [51]. These statistics show that adolescent girls in Iran give more attention to education than boys; therefore, probably, the girls with anxiety or depression suffer from academic failure more than boys. In general, the literature on sex differences of functional impairment in adolescents is very mixed and there are few consistent patterns. Therefore, there is a need for more research to draw definite conclusions, especially for Iranian adolescents.

Conclusion

The Persian ALIS-I has excellent structural validity and reliability and can be used to evaluate Iranian adolescents’ functional impairment. Thus, clinical psychologists in Iran can confidently use the Persian version of the ALIS to assess the degree of functional impairment in adolescents caused by anxiety and depression in different social contexts.

Despite the promising results, this study has certain limitations. Since the participants came from different cities in Iran, further research is required before the results can be generalized to the entire Iranian population. Participation in the study was fully online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have introduced biases such as self-selection (participants choosing to complete the survey), undercoverage (limited internet access in the target population), and voluntary response (responses mainly from self-selected volunteers). Consequently, the generalization of the findings is limited to Iranian adolescents who attended the selected high schools in the mentioned cities and had internet access. There were also demographic differences between the clinical and non-clinical groups, which should be considered when interpreting the results. Therefore, additional research involving a broader range of adolescents from Iran or other countries is essential. Moreover, the ALIS-I is recommended for use in experimental studies to further examine its functional validity.

Limitations and recommendations

Despite the promising results, this study has certain limitations. Since the participants came from different cities in Iran, further research is required before the results can be generalized to the entire Iranian population. Participation in the study was fully online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which may cause self-selection bias (the participant is informed about the survey and decides to complete the survey), undercoverage bias (whether the target population has internet access), voluntary response bias (when the sample consists of self-selected volunteers). The generalization of the findings is thus limited to Iranian adolescents who attended the selected high schools in the mentioned cities and had access to the internet. There were demographic differences between the two clinical and non-clinical groups, which should be taken into account when interpreting the study’s results. Therefore, conducting further research involving a wider range of adolescents from Iran or other countries seems essential. The ALIS-I is also recommended to be used in experimental studies to determine its functional validity.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.167). All procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical principles. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to the research. They had the right to leave the study at any time and were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This study was extracted from the dissertation of Nasim Mousavi, at the Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Abbas Pourshahbaz and Nasim Mousavi; Investigation and writing the original draft: Nasim Mousavi; Review and editing: Hamid Poursharifi, Abbas Pourshahbaz, Fereshteh Momeni, and Ronald Rapee.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Omid Rezaee, Mr. Reza Araei, and Dr. Marzieh Norozpour for their contributions to this research as well as all participants for their cooperation.

References

- Klaufus L, Verlinden E, van der Wal M, Cuijpers P, Chinapaw M, Smit F. Adolescent anxiety and depression: burden of disease study in 53,894 secondary school pupils in the Netherlands. BMC Psychiatry. 2022; 22(1):225. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-022-03868-5] [PMID]

- Mohammadi MR, Ahmadi N, Khaleghi A, Mostafavi SA, Kamali K, Rahgozar M, et al. Prevalence and correlates of psychiatric disorders in a national survey of Iranian children and adolescents. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2019; 14(1):1-15. [DOI:10.18502/ijps.v14i1.418] [PMID]

- Oliveira JMD, Butini L, Pauletto P, Lehmkuhl KM, Stefani CM, Bolan M, et al. Mental health effects prevalence in children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2022; 19(2):130-7. [DOI:10.1111/wvn.12566] [PMID]

- Ahlen J, Hursti T, Tanner L, Tokay Z, Ghaderi A. Prevention of anxiety and depression in Swedish school children: A cluster-randomized effectiveness study. Prev Sci. 2018; 19(2):147-58. [DOI:10.1007/s11121-017-0821-1] [PMID]

- Greenberg PE, Fournier AA, Sisitsky T, Pike CT, Kessler RC. The economic burden of adults with major depressive disorder in the United States (2005 and 2010). The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2015; 76(2):155-62. [DOI:10.4088/JCP.14m09298] [PMID]

- Cummings CM, Caporino NE, Kendall PC. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: 20 years after. Psychological Bulletin. 2014; 140(3):816-45. [DOI:10.1037/a0034733] [PMID]

- Schniering CA, Forbes MK, Rapee RM, Wuthrich VM, Queen AH, Ehrenreich-May J. Assessing functional impairment in youth: development of the adolescent life interference scale for internalizing symptoms (ALIS-I). Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2023; 54(2):508-19. [DOI:10.1037/t88321-000] [PMID]

- Young JF, Mufson L, Davies M. Impact of comorbid anxiety in an effectiveness study of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006; 45(8):904-12. [DOI:10.1097/01.chi.0000222791.23927.5f] [PMID]

- Starr LR, Davila J. Differentiating interpersonal correlates of depressive symptoms and social anxiety in adolescence: Implications for models of comorbidity. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008; 37(2):337-49. [DOI:10.1080/15374410801955854] [PMID]

- Ollendick TH, Jarrett MA, Grills-Taquechel AE, Hovey LD, Wolff JC. Comorbidity as a predictor and moderator of treatment outcome in youth with anxiety, affective, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional/conduct disorders. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008; 28(8):1447-71. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.003] [PMID]

- Schniering CA, Rapee RM. Evaluation of a transdiagnostic treatment for adolescents with comorbid anxiety and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports. 2020; 2:100026. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadr.2020.100026]

- Pruessner L, Timm C, Kalmar J, Bents H, Barnow S, Mander J. Emotion regulation as a mechanism of mindfulness in individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2024; 2024:9081139. [DOI:10.1155/2024/9081139] [PMID]

- Berk LE. Development through the lifespan. 7th ed. Boston: Pearson; 2014. [Link]

- Rapee RM, Bőgels SM, van der Sluis CM, Craske MG, Ollendick T. Annual research review: Conceptualising functional impairment in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2012; 53(5):454-68. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02479.x] [PMID]

- Shaffer DE, Lucas CP, Richters JE. Diagnostic assessment in child and adolescent psychopathology. New York: The Guilford Press; 1999. [Link]

- Stein RE, Jessop DJ. Functional status II(R). A measure of child health status. Medical Care. 1990; 28(11):1041-55. [DOI:10.1097/00005650-199011000-00006] [PMID]

- Dickson SJ, Kuhnert RL, Lavell CH, Rapee RM. Impact of psychotherapy for children and adolescents with anxiety disorders on global and domain-specific functioning: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2022; 25(4):720-36. [DOI:10.1007/s10567-022-00402-7] [PMID]

- Palermo TM, Long AC, Lewandowski AS, Drotar D, Quittner AL, Walker LS. Evidence-based assessment of health-related quality of life and functional impairment in pediatric psychology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008; 33(9):983-96. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsn038] [PMID]

- Palermo TM, Witherspoon D, Valenzuela D, Drotar DD. Development and validation of the Child Activity Limitations Interview: A measure of pain-related functional impairment in school-age children and adolescents. Pain. 2004; 109(3):461-70. [DOI:10.1016/j.pain.2004.02.023] [PMID]

- Walker LS, Greene JW. The functional disability inventory: measuring a neglected dimension of child health status. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1991; 16(1):39-58. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/16.1.39] [PMID]

- Rapee RM, Oar EL, Johnco CJ, Forbes MK, Fardouly J, Magson NR, et al. Adolescent development and risk for the onset of social-emotional disorders: A review and conceptual model. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2019; 123:103501. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2019.103501] [PMID]

- Bonnie RJ, Backes EP, Alegria M, Diaz A, Brindis CD. Fulfilling the promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2019; 65(4):440-2. [DOI:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.07.018] [PMID]

- Attell BK, Cappelli C, Manteuffel B, Li H. Measuring Functional Impairment in Children and Adolescents: Psychometric properties of the Columbia impairment scale (CIS). Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2020; 43(1):3-15. [DOI:10.1177/0163278718775797] [PMID]

- Rao PA, Beidel DC, Turner SM, Ammerman RT, Crosby LE, Sallee FR. Social anxiety disorder in childhood and adolescence: Descriptive psychopathology. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2007; 45(6):1181-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2006.07.015] [PMID]

- Duinhof EL, Lek KM, de Looze ME, Cosma A, Mazur J, Gobina I, et al. Revising the self-report strengths and difficulties questionnaire for cross-country comparisons of adolescent mental health problems: The SDQ-R. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences. 2019; 29:e35. [DOI:10.1017/S2045796019000246] [PMID]

- Hariharan M, Padhy M, Monteiro SR, Nakka LP, Chivukula U. Adolescence Stress Scale: Development and Standardization. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2023; 19(2):197-206. [DOI:10.1177/09731342231173214]

- Abbasi N, Ghosh S. Construction and standardization of examination anxiety scale for adolescent students. International Journal of Assessment Tools in Education. 2020; 7(4):522-34. [DOI:10.21449/ijate.793084]

- Hadianfard H, Kiani B, Azizzadeh Herozi M, Mohajelin F, Mitchell JT. Health-related quality of life in Iranian adolescents: a psychometric evaluation of the self-report form of the PedsQL 4.0 and an investigation of gender and age differences. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2021; 19(1):108. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-021-01742-8] [PMID]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. fifth ed. New York: Guilford publications; 2023. [Link]

- Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, Ferraz MB. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine. 2000; 25(24):3186-91. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-200012150-00014] [PMID]

- First M, Williams J, karg R, Spitzer R. SCID-5-CV: Structured clinical interview for DSM-5 disorders: Clinician version. Tehran: Ebnesina Publication; 2016. [Link]

- Kennedy SM, Ehrenreich-May J. Assessment of emotional avoidance in adolescents: Psychometric properties of a new multidimensional measure. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2017; 39(2):279-90. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-016-9581-7]

- Mousavi N, Poursharifi H, Momeni F, Pourshhbaz A, Rapee R. [Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Adolescent life interference scale for internalizing symptoms among iranian adolescents (Persian)]. Archeves of Rehabilitation. 2025; 26(3) [Unpublished]. [Link]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables (7th ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2012. [Link]

- Morin AJ. Exploratory structural equation modeling. In: Hoyle RH, editor. Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Press; 2021. [Link]

- Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999; 6(1):1-55. [DOI:10.1080/10705519909540118]

- van Zyl LE, Ten Klooster PM. Exploratory structural equation modeling: Practical guidelines and tutorial with a convenient online tool for mplus. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022; 12:795672. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.795672] [PMID]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling. 2009; 16(3):397-438. [DOI:10.1080/10705510903008204]

- Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 2000; 3(1):4-70. [DOI:10.1177/109442810031002]

- Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. Hoboken: John Wiley & sons; 2013. [Link]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research. 1981; 18(1):39-50. [DOI:10.2307/3151312]

- Lai K, Green SB. The problem with having two watches: Assessment of fit when RMSEA and CFI disagree. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2016; 51(2-3):220-39. [DOI:10.1080/00273171.2015.1134306] [PMID]

- Nagar S, Sherer JT, Chen H, Aparasu RR. Extent of functional impairment in children and adolescents with depression. Current Medical Research and Opinion. 2010; 26(9):2057-64. [DOI:10.1185/03007995.2010.496688] [PMID]

- Scott J, Scott EM, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, Guastella AJ, White D, et al. Functional impairment in adolescents and young adults with emerging mood disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2014; 205(5):362-8. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.bp.113.134262] [PMID]

- Ezpeleta L, Granero R, de la Osa N, Guillamón N. Predictors of functional impairment in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2000; 41(6):793-801. [DOI:10.1111/1469-7610.00666] [PMID]

- Hadianfard H, Kiani B, Weiss MD. Study of functional impairment in students of elementary and secondary public schools in Iran. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021; 30(2):68-81. [PMID]

- Amiri P, M Ardekani E, Jalali-Farahani S, Hosseinpanah F, Varni JW, Ghofranipour F, et al. Reliability and validity of the Iranian version of the pediatric quality of life inventory™ 4.0 generic core scales in adolescents. Quality of Life Research. 2010; 19(10):1501-8. [DOI:10.1007/s11136-010-9712-7] [PMID]

- Ghahremani S, Ahmadian Vargahan F, Khanjani S, Farahani H, Fathali Lavasani F. [Psychometric properties of the mental health and social inadaptation assessment in Iranian adolescents (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2022; 28(1):106-21. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.28.1.2000.3]

- The World Bank Group. Literacy rate, youth female (% of females ages 15-24) - Iran, Islamic Rep [Internet]. 2021 [Updated 2025 January 26]. Available from: [Link]

- Mehran G. Gender and education in Iran. Paris: The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 2003. [Link]

- The World Bank Group. School enrollment, tertiary, female (% gross) - Iran, Islamic Rep [Internet]. 2023 [Updated 2024 March 20]. Available from: [Link]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Clinical Psycology

Received: 4/06/2024 | Accepted: 21/07/2025 | Published: 23/09/2025

Received: 4/06/2024 | Accepted: 21/07/2025 | Published: 23/09/2025

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |