Volume 25 - Special Issue

jrehab 2024, 25 - Special Issue: 726-745 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mowzoon H, Hassanati F, Nilipour R, Mohammadzamani M R, Ghoreishi Z S. Investigating the Relationship Between Linguistic Variables and Executive Functions in Persian-speaking Children Aged 5-8 Years With and Without Developmental Language Disorder. jrehab 2024; 25 (S3) :726-745

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3407-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3407-en.html

Hoda Mowzoon1

, Fatemeh Hassanati1

, Fatemeh Hassanati1

, Reza Nilipour1

, Reza Nilipour1

, Mohammad Reza Mohammadzamani1

, Mohammad Reza Mohammadzamani1

, Zahra Sadat Ghoreishi *2

, Zahra Sadat Ghoreishi *2

, Fatemeh Hassanati1

, Fatemeh Hassanati1

, Reza Nilipour1

, Reza Nilipour1

, Mohammad Reza Mohammadzamani1

, Mohammad Reza Mohammadzamani1

, Zahra Sadat Ghoreishi *2

, Zahra Sadat Ghoreishi *2

1- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,zahraqoreishi@yahoo.com

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: Developmental language disorder, Verbal fluency, Specific language disorder, Language, Executive functions

Full-Text [PDF 2065 kb]

(737 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4177 Views)

Full-Text: (892 Views)

Introduction

Developmental language disorder (DLD) describes individuals who, during a known biomedical condition, have problems with language that affect daily functioning and lifelong functioning [1]. Until 2017, this disorder was known as specific language impairment (SLI); however, Bishop proposed the label of DLD for SLI this year. In this disorder, despite having intellectual, social, emotional and normal hearing functions, the child is delayed in acquiring language skills. These children have major deficits in language learning and will not be able to compensate for these deficits until the age of 5 years [2]. This disorder is common and it is estimated that on average two children in each class have this disorder [3]. Children with DLD have different degrees of damage in different parts of language comprehension and expression. These damages are manifested in the aspects of semantics and grammar [4]. For example, this has been observed in various studies that these children have a shorter mean length of utterance. They also have limitations in the use of syntactic structures [5] and weaker performance in vocabulary development, word definition [6], and storytelling [7]. Studies conducted in recent years on this disorder have shown that these children are not only impaired in language skills but also in other skills, including cognitive skills [4-6]. Among the cognitive domains that have been investigated in these children in recent years is the domain of executive functions. Executive functions play an important role in language processing [8] and they are one of the underlying processes involved in cognitive performance. These processes include behaviors such as self-regulation, self-initiation, cognitive flexibility, planning, response inhibition, sustained attention, selective attention, shifting, organizing, and working memory [9]. These skills are involved in solving complex and new problems and it is thought that they arise through language [10]. In this research, two skills of selective attention and problem-solving/organization have been investigated. Selective attention means avoiding the interference of irrelevant information (either as a dominant response or as a non-dominant response) and choosing information related to the goal [11]. The organization also includes a series of stages of problem analysis, testing solutions, creating possible solutions, and modifying behavior or changing strategies when a solution is not successful. This ability is often associated with the prefrontal cortex [12، 13]. Research conducted on the relationship between executive function and language processing in children with DLD shows that tasks related to language processing, such as sentence comprehension are largely influenced by executive function [14]. Many children with DLD perform at a slower speed in cognitive tasks and complex language tasks than their normal peers, and their performance patterns are different [15-20]. One of the reasons for these problems, or at least part of them, can be the existence of deficits in executive functions. However, due to the few studies conducted in this area on children with DLD, this disorder is still not well understood [21، 22]. Various studies have investigated specific aspects of executive function, such as working memory and inhibitory responses in children and adults with DLD. For example, according to several studies, children with DLD have deficits in verbal working memory. These deficits have been shown in various tasks, such as non-word repetition, listening span, and dual processing of sentence comprehension [22، 23]. Vugs et al. (2014) in a study investigated executive functions, including working memory in children with DLD. The results of this study showed that children with DLD performed weaker than normal peers in cognitive skills including working memory in both the verbal and visual-spatial sections. Deficits in executive functions included problems in shifting, inhibition, planning/organization and emotional control, and the relationship pattern between working memory function and executive function behaviors was also different in the two groups [24]. Flores CamasCamas and Leon-Rojas (2023), who reviewed the studies conducted in the field of SLI and executive function in school-age children, stated that the cognitive skills of children with SLI in terms of inhibition, processing capacity, planning and organization, attention, verbal reasoning, and logic are limited. Accordingly, they have fewer cognitive resources and cannot use them effectively. The findings of this study showed that children with SLI have deficits, low academic performance, and sometimes, serious disorders in the development of executive function compared to normal peers aged 3 to 4 years. The most observed changes were in attention, working memory (including auditory memory, phonological memory, and visual/verbal memory), processing speed, planning, inhibition, cognitive flexibility and inner speech. The above results are due to the view that language development may have a significant impact on the acquisition and development of executive function, and both of them are necessary for cognitive development [25]. Blom and Boerma (2019) examined the relationship between language skills and executive functions with lexical and syntactic development in 117 children with and without DLD. Their study showed that both groups showed stable lexical and growth in syntactic skills. In children with DLD, syntactic skills and executive functioning, including interference control, selective attention, and working memory were predictive of vocabulary skills. However, in the group of normal children, vocabulary skills were predictive of executive performance. The mean scores of selective attention and interference control in children with DLD were higher than the group of normal children, but in working memory tasks, normal children obtained higher scores [26]. Kapa and Erickson (2020) also examined the relationship between executive function and word learning in normal preschool children and children with DLD. The results showed that the performance of children with DLD in all sections of executive function, including shifting, short-term memory, working memory, selective attention, inhibition and language skills of word learning was weaker than normal peers. The findings showed that children with DLD were weaker in word learning than normal peers, and also preschoolers were weak in learning new words for familiar objects. The results of this study support the relationship between executive function and vocabulary learning in children with and without DLD [17]. In another study, Ralli et al. (2021) examined working memory, executive function, and verbal fluency concerning non-verbal intelligence in Greek-speaking school-age children. The studied age group was 8 to 9 years old and included one group of children with DLD and another matched normal group. Data analysis showed that children with DLD have earned scored lower in non-verbal intelligence measures than the normal peer group, but had better scores in working memory capacity, verbal fluency (phonetic and semantic), updating, and monitoring [21]. Finneran et al. (2009) studied sustained attention in the two components of accuracy and response time. The results showed that children with DLD had a weaker performance than the normal group in terms of accuracy, but their response speed was not significantly different from the normal group [27]. Among the researchers conducted in Iran, we can refer to Haresabadi et al.’s study (2021), in which they investigated grammatical and lexical language functions and theory of mind skills in two groups of children with high-functioning autism and DLD and compared them with normal children. The results of this research showed that both groups of children with impaired skills performed worse than their normal peers [28]. Also, Yazdani et al. (2012) investigated the effect of non-word repetition tasks on the linguistic variables of children with DLD. According to this research, most of the studied children showed improvement in their language indicators [29]. Despite the studies that have investigated executive function in children with DLD worldwide [30] and in Iran [28، 29], the relationship between executive function and language deficits is still unknown. Considering that most of these studies have been conducted on English-speaking children [31], it is necessary to produce similar research in the Persian language. Due to the importance of executive function in developmental disorders, many studies have been conducted on executive function in other developmental disorders such as autism, learning disability, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [32-36]. Understanding the relationship between language skills and executive function in children with DLD is essential for clinical use in this field because by identifying the side areas of disorders in these children, a more suitable treatment program can be designed for the weak aspects of language. On the other hand, by more closely examining the relationship between different aspects of language skills and executive functions, existing theories in this field can be improved. In this study, those linguistic skills were investigated, and according to various studies, DLD children have more problems in this field and are often considered as a criterion for differential diagnosis of children with and without DLD [7]. Also, selective attention was chosen from executive functions because it is a basic skill and most executive functions are based on it [37]. Also, the skill of organization/problem solving was chosen as a skill that has existed since the beginning of children’s development and gradually grows, and having this knowledge does not necessarily mean solving the existing problem. Rather, it can facilitate the transfer of knowledge from one situation to another [38]. Hence, this study investigates the relationship between linguistic variables (including type-token ratio, number of utterances, syntactic complexity, syntactic comprehension, repetition and verbal fluency) and executive function (including selective attention and organization/problem-solving) in 5 to 8-year-old Persian-speaking children with and without DLD.

Materials and Methods

The current study is descriptive-analytical and cross-sectional-comparative, in which the subjects were evaluated using executive functions and language assessment tools. The studied sample included 56 normal children (26 boys and 30 girls) 5 to 8 years old (preschool, first and second elementary school) and 20 children with DLD (12 boys and 8 girls) 5 to 8 years old (preschool, first and second elementary school). These two groups were matched in terms of intelligence quotient (general intelligence quotient above 85 in the Wechsler test), chronological age and educational level. Children with DLD were selected from the available sampling method among the referrals to learning disability centers and public and private rehabilitation clinics in Tehran City, Iran, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A cluster sampling method was used to sample the children of the peer group. First, several normal schools from 10 schools in 5 education regions of Tehran City, Iran, including regions 10, 9, 8, 1 and 16 and then the number of classes in each school and the number of students in each class were randomly selected. The inclusion criteria were being 5 to 8 years old, monolingual in Persian, having normal non-verbal intelligence (85 and above in the Wechsler test) and also for the group with DLD (based on the diagnostic criteria), obtaining a language test score of at least 2 standard deviations (in one of the language tasks) or at least 1.5 standard deviations (in two or more language tasks) lower than their age peers (using the Persian language development test). Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria included having any neurological disease and accompanying psychiatric disorders and having any visual or hearing impairment. To ensure the health of normal children, the child’s medical file was first referred to, and then two researcher-made reporting forms (one for the teacher and one for the parents) were completed. To diagnose children with disorders, reporting forms (parents and teachers) in addition to the clinical diagnosis of 3 expert speech therapists (with an average professional age of 8 years who were active in the field of assessment and treatment of developmental disorders) based on DLD diagnostic criteria [1] and Persian language developmental battery [39] were used. After entering the desired samples into the study, the informed consent form and history taking were presented to the parents. After ensuring the ability of the subjects to work with the computer and familiarizing themselves with the instructions for the test provided by the researcher, the neuropsychological computer tests of the tower of London, day and night Stroop [40], verbal fluency [41] and parts of the Persian language developmental battery [39] was done by the participants.

Study measurements and implementation methods

After selecting children with and without DLD, children of both groups were evaluated in terms of language skills and executive functions. In the following, the structure and implementation method of the used tests are explained.

Tower of London test

The tower of London test is designed to evaluate at least two aspects of executive functions: Strategic planning and problem-solving. The test used in this research was prepared by the Sina Institute of Psychological Products. This test has good construct validity in measuring people’s planning and organization. A correlation of 0.41 has been reported between the results of this test and the Proteus maze test. The reliability of this test is accepted and reported as 0.79 [42]. In this test, the subject makes the shape of the sample by moving the colored plates (green, blue, red) and placing them in the right place, with the minimum necessary movements. In each stage, the person is allowed to solve the problem 3 times and the person must solve the example according to the instructions with the minimum necessary moves. At each stage, after success (and if the problem is not solved after 3 attempts), the next problem is provided to the subject. The variables of this test (the data obtained from this test) are total time, delay time, experience time, number of errors, and total score.

Day and night stroop test

The day and night stroop test is the most widely used Stroop measure used for children. This task was first designed by Gerstadt et al. in 1994. Accordingly, two sets of cards are used as follows: One set for the day and night condition and one set for the control condition. The examiner asks the subject to call it day when they see the image of the moon and call it night when they see the image of the sun. The images are presented to the subject in order (according to the predetermined sequence) and the results are recorded. The recorded information of this task included: the correct answers of the subject, the delayed response in each item, and the delayed response in all items. The validity of this assignment is 90 [40]. In this study, this task was implemented using the DMDX software, version 4 The sequence of 16 images of the moon and the sun was designed in computer form (according to the original pattern of the initial test) and the children’s answers were recorded orally using a microphone and in written form. The microphone was fixed on the microphone stand at a distance of 15-20 cm from the subject. The time interval between each item and the next item was considered to be 2000 ms. To check the internal validity of the DMDX measurement tool, the Cronbach α test was performed on the items of this tool. According to the results, the Cronbach α estimated for this tool is 0.899, which is considered excellent for research purposes. In this research, this task was used to investigate selective attention. Meanwhile, to investigate the linguistic variables, the verbal fluency task and Persian language developmental battery have been used. The measured variables included verbal fluency (semantic), type-token ratio, number of utterances, complexity, and syntactic understanding and repetition.

Persian language developmental battery

The Persian language developmental battery was designed by Nilipour in 2015 as a research project at the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, and it is based on the Gopnic 5 test. It was then developed after cultural and linguistic adaptions for the Persian language. The Cronbach α (internal consistency coefficient) of this test, which was performed on 60 Persian-speaking 5-10-year-old children, was 0.9. This test has 9 sub-tests to evaluate language skills, which include pointing, grammatical judgment, grammatical modification, derivational morphemes, verb tense, listening comprehension, Vag test, syntactic comprehension, and repetition. After the test, the language profile of each child with DLD was obtained in each of the above nine subtests [39].

Verbal fluency test

Verbal fluency is examined in the two following ways: Semantic fluency and phonemic fluency [41]. In the current research, semantic fluency was considered. There are several tests to assess this skill, but the most common one is naming fruits and animals to evaluate semantic fluency [43]. These tasks are often used in neuro-psychological evaluations and research projects [44]. In this test, the subject was asked to remember and say as many names of fruits and animals (first from the group of fruits and then from the group of animals) within 1 min (for each semantic category). The number of spoken words (repeated words, words that were not included in the intended semantic classes, or self-made words are not counted) were counted and compared and analyzed. The research data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 18. Meanwhile, to analyze the data, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check the data distribution, the independent t-test was used to check the difference between the two studied groups, and the Pearson correlation was used to check the relationship between executive function and language deficits in children with DLD.

Results

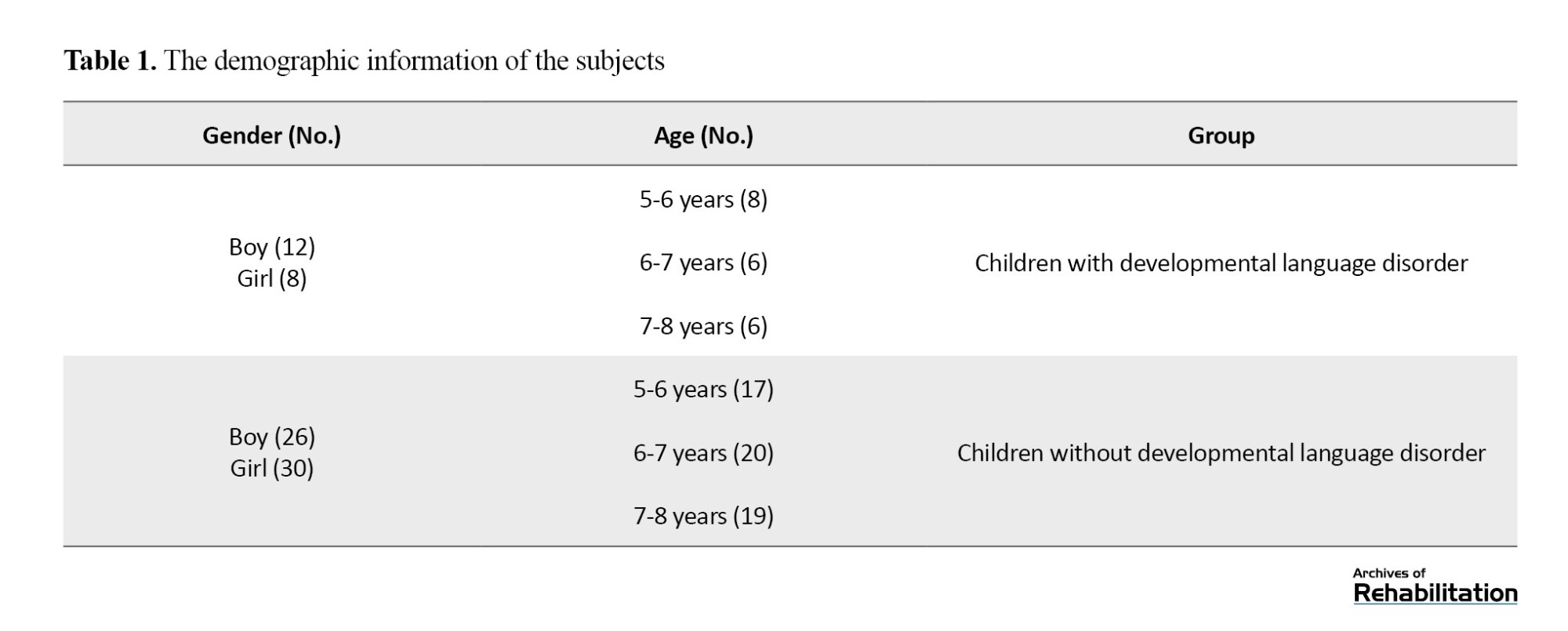

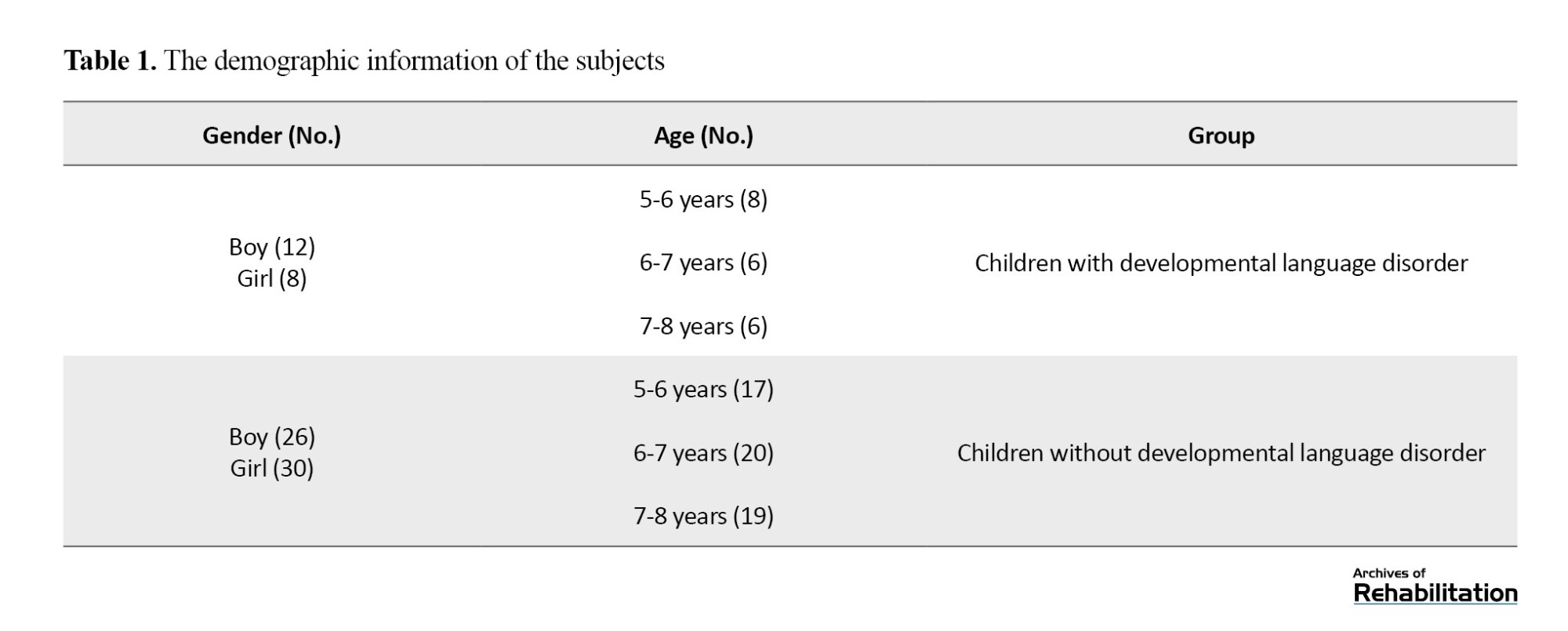

Considering that the distribution of data in the normal and impaired group in language skills and executive functions was normal (P>0.05), using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, parametric tests were conducted to compare the variables. Table 1 demonstrates the demographic information of the subjects.

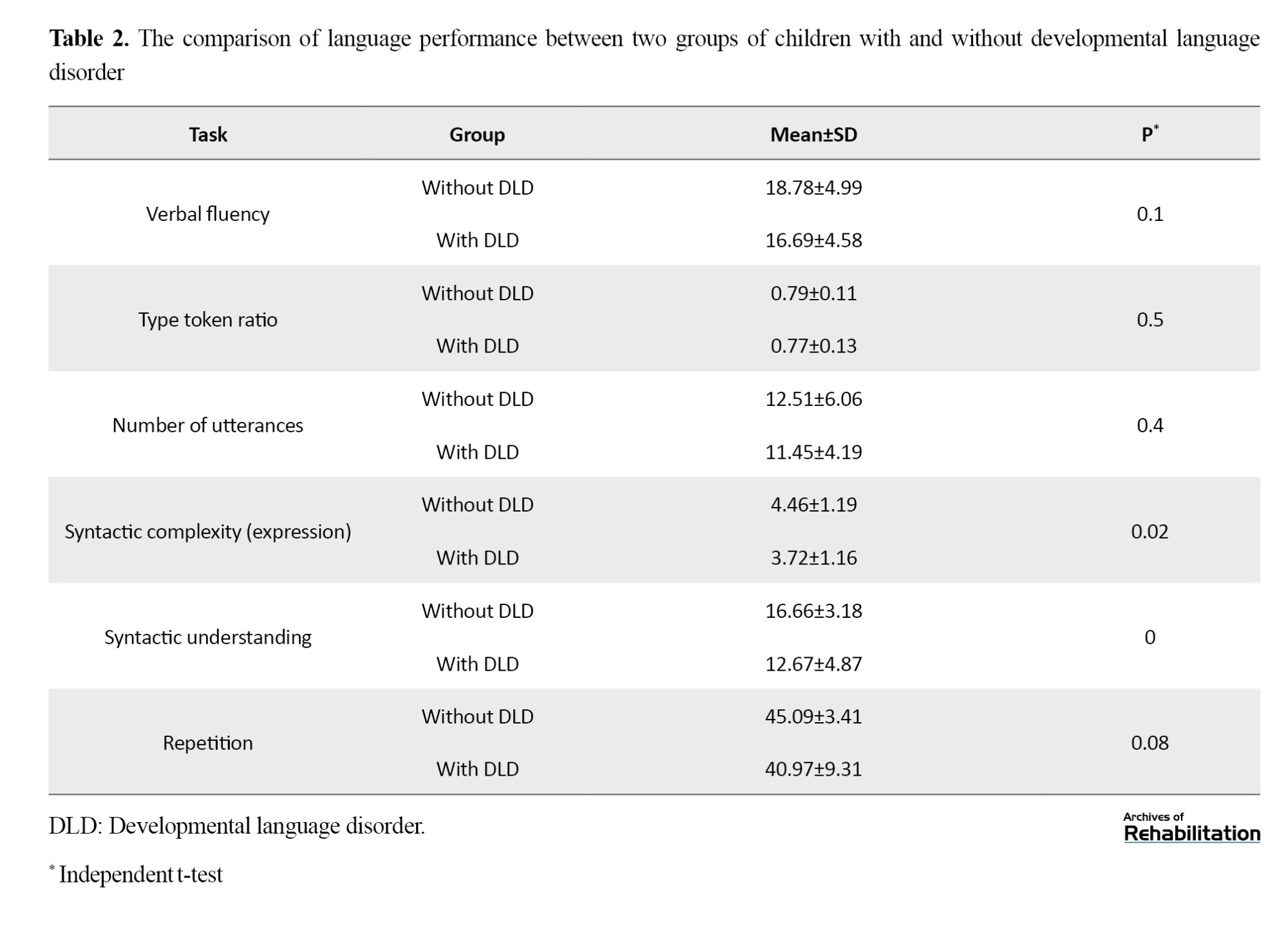

Meanwhile, Table 2 shows the Mean±SD and independent t-test results in language variables to inspect the difference between the two groups in these components.

According to Table 2, the average language scores of the group without DLD are higher than the group of children with DLD, but this difference in verbal fluency test was not significant between the two groups. Also, the mean type token ratio, the number of utterances, and repetition did not differ significantly (P>0.05). There was a significant difference between the two groups in linguistic indexes of complexity and syntactic understanding (P<0.05).

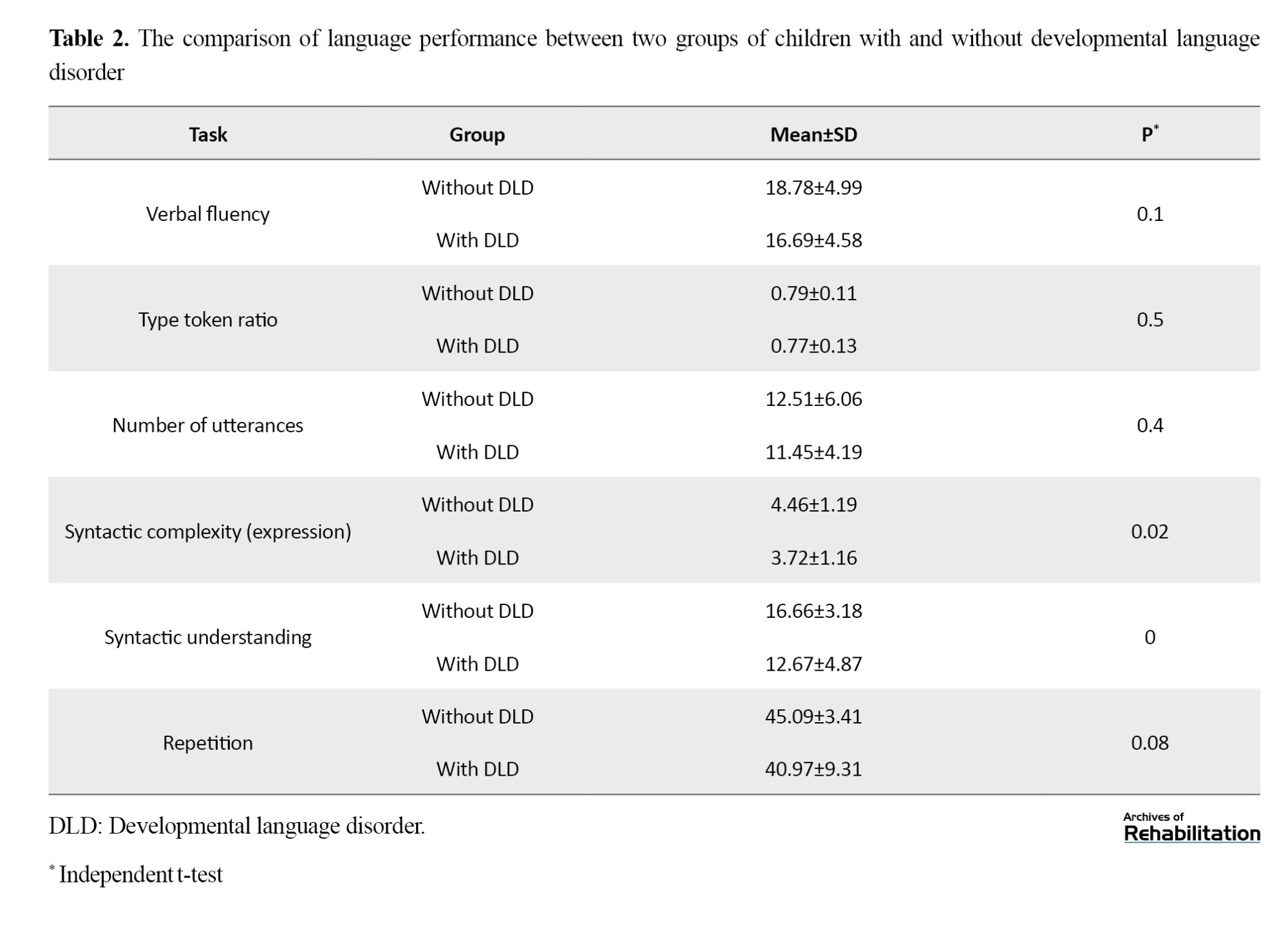

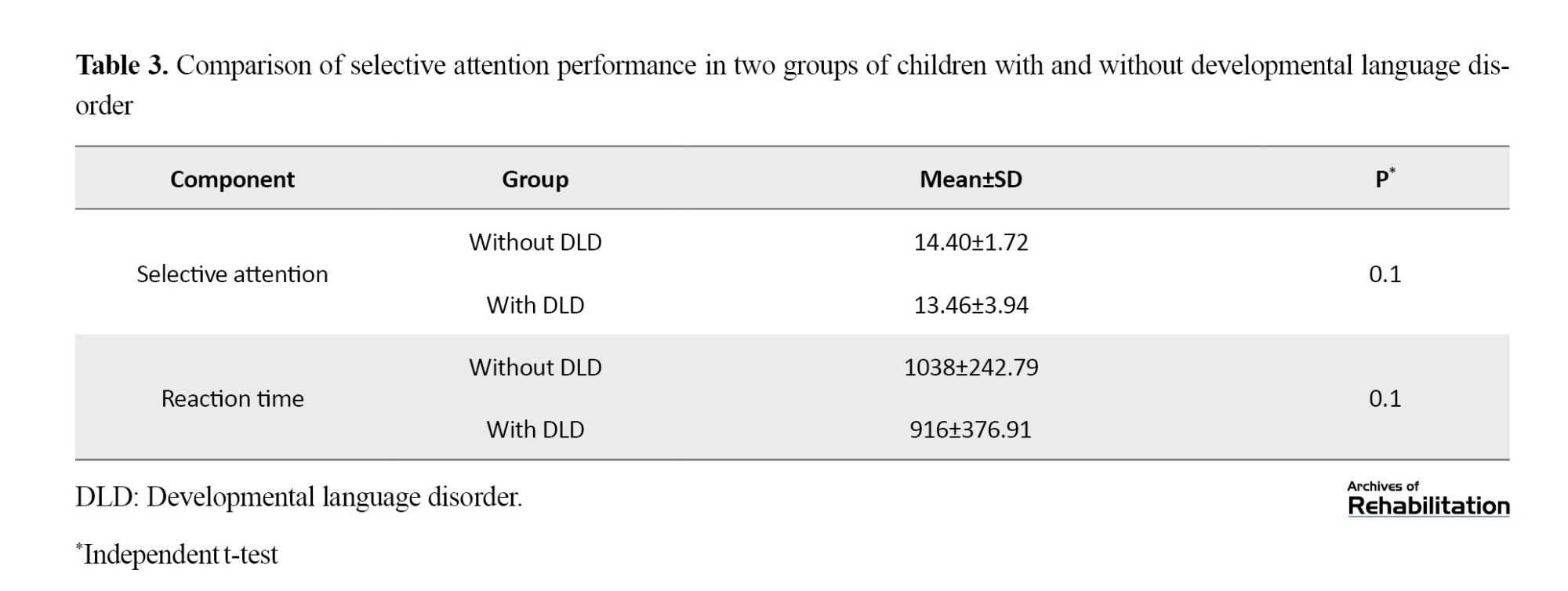

To compare the ability of the two research groups in selective attention, as one of the components of executive functions, the day and night Stroop test was used. Table 3 shows the Mean±SD of the scores related to the number of correct answers as well as the reaction time to the Stroop test items, as well as the results of the independent groups t-test to study the significant differences between the two groups in this component.

According to Table 3, the two groups did not show any significant difference in reaction time or any of the components of selective attention, which indicates the correct answers in the Stroop test (P>0.05).

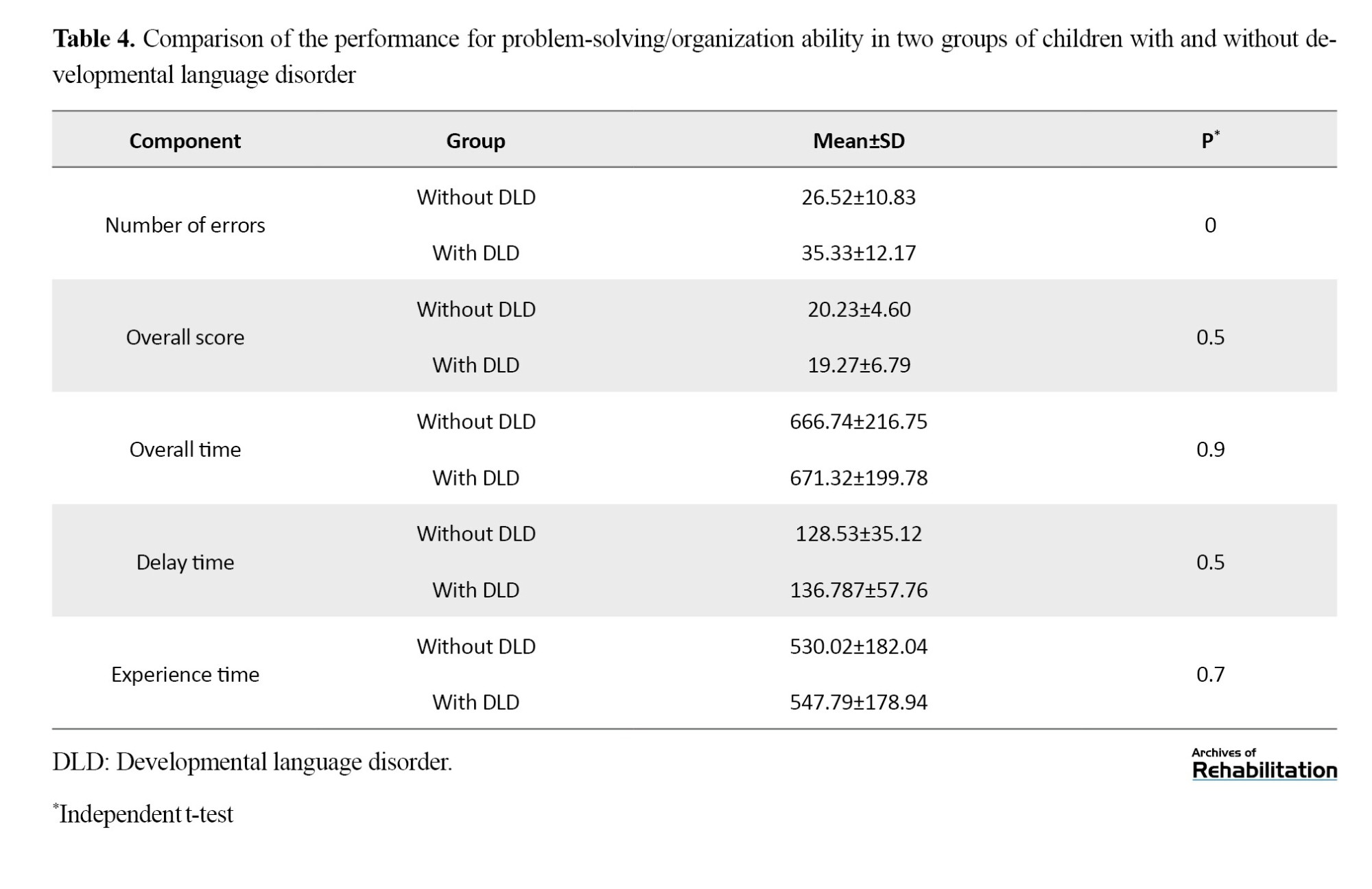

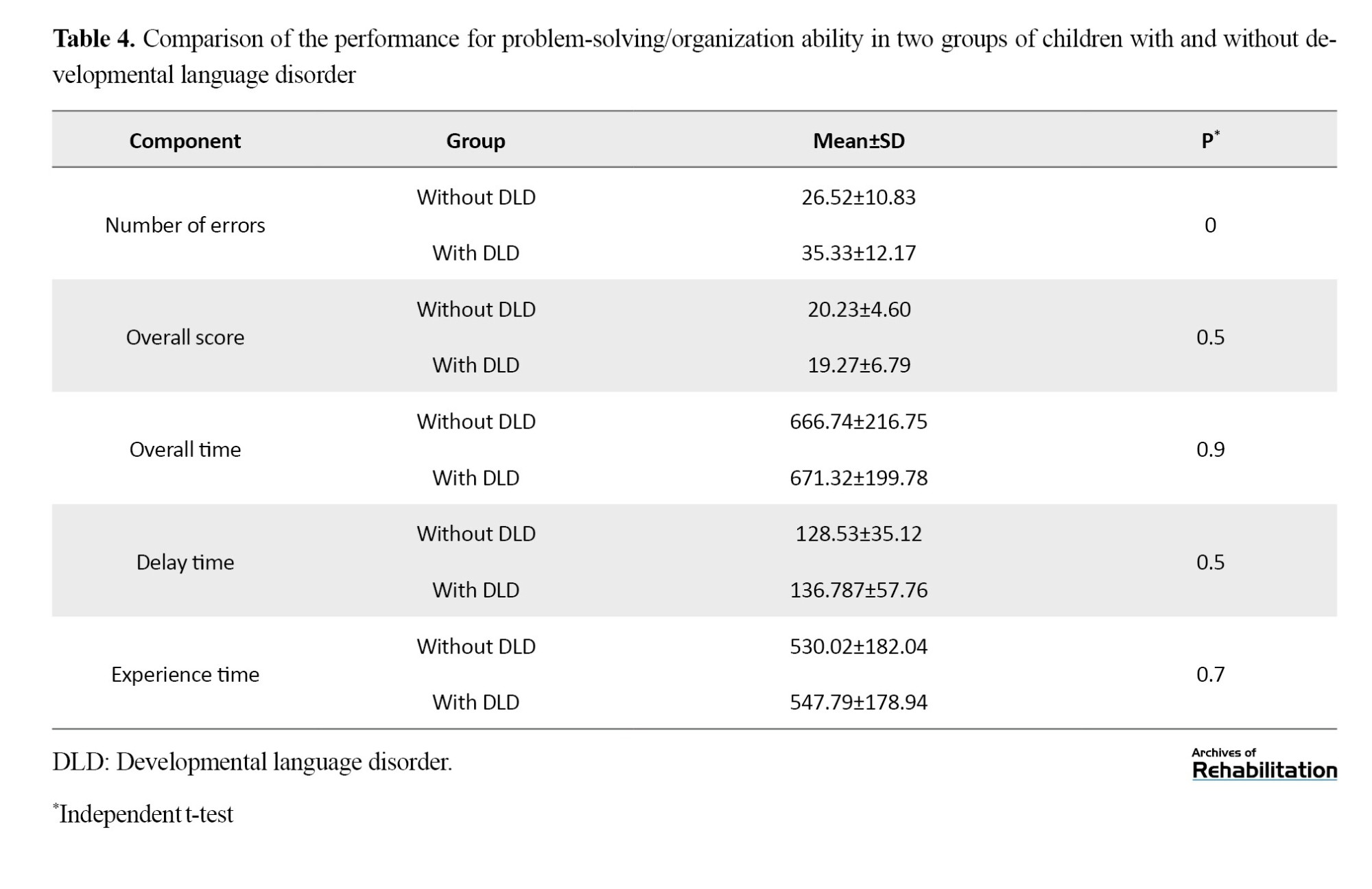

The tower of London test was used to compare two groups of subjects in problem-solving/organization ability, as one of the components of executive functions. Table 4 demonstrates the Mean±SD of scores related to the number of errors, overall score, overall test time, delay time, and experience time, as well as the results of the t-test of independent groups to identify notable differences between the two groups.

According to Table 4, two groups showed a significant difference in the number of errors for problem-solving skills (P<0.05). There was no serious difference between the two groups for other components.

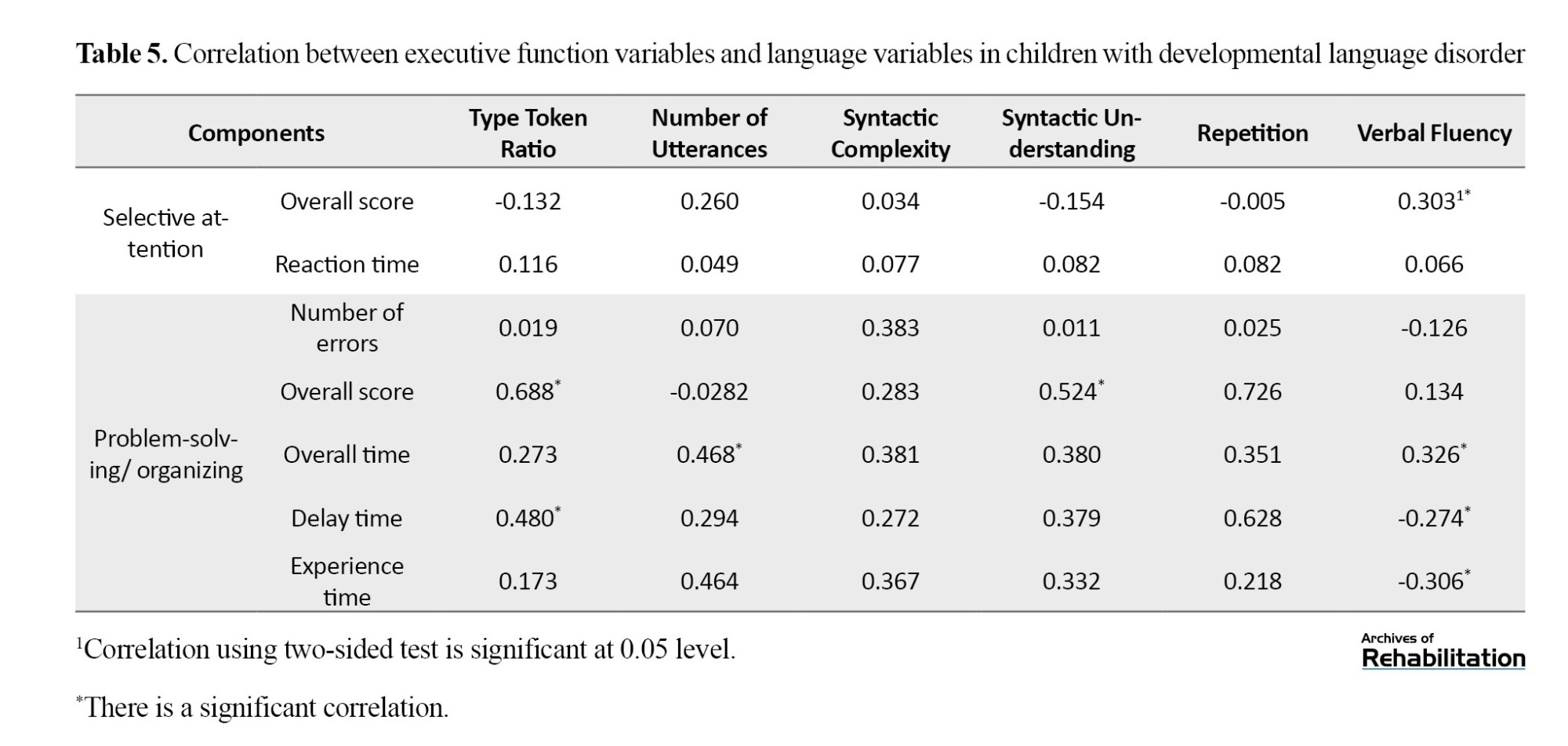

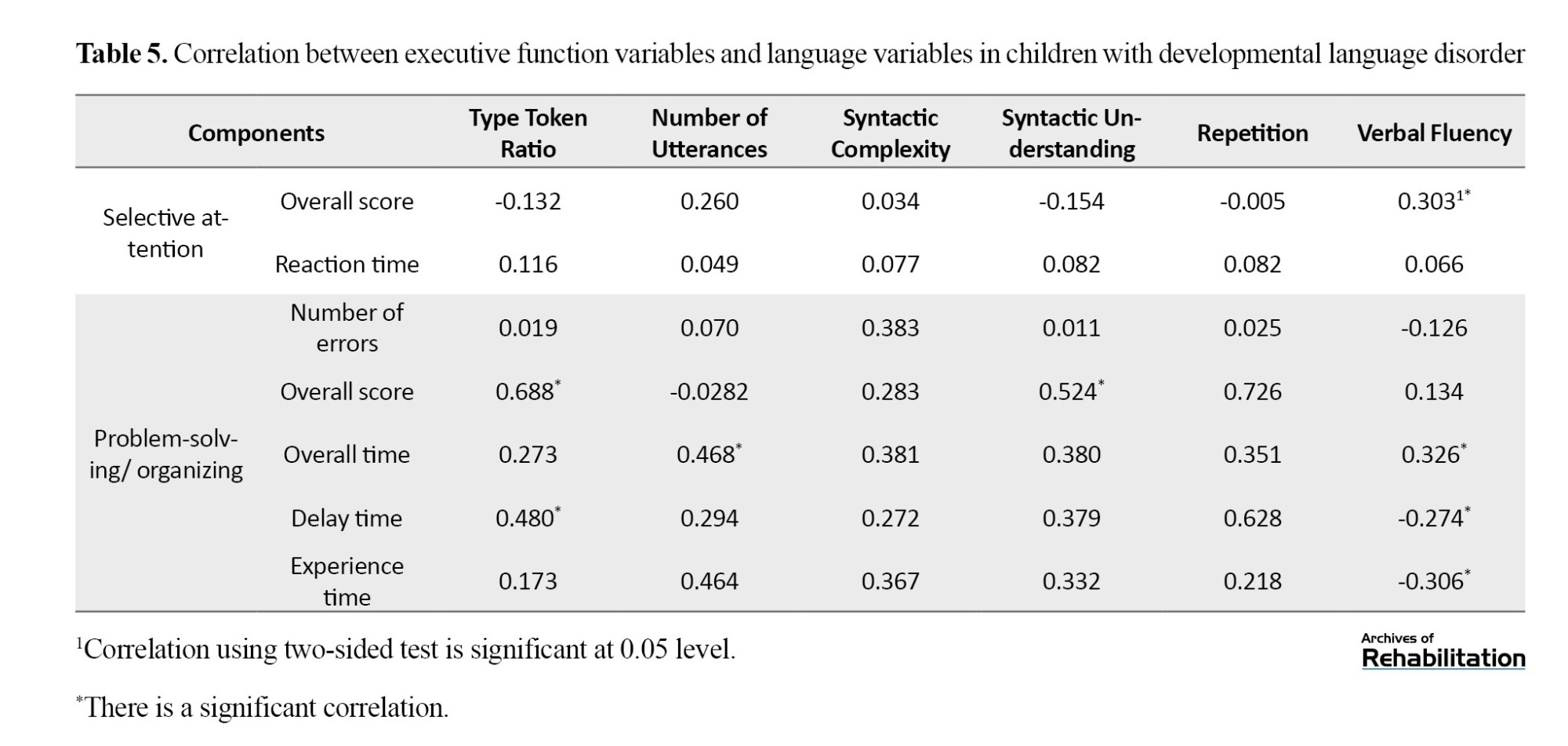

To investigate the relationship between executive functions and language deficits in children with DLD, the Pearson correlation was used. The results of this study are shown in Table 5.

According to the results of Table 5, in examining the relationship between selective attention skill and verbal fluency variable, a positive and significant correlation (r=0.30) was observed only between the two components of the total score of selective attention and verbal fluency. Concerning problem-solving/organizing skills, between the components of the total score with type-token ratio (r=0.68) and syntactic understanding (r=0.52), total time with the number of utterances (r=0.46) and verbal fluency (r=0.32), delay time with type-token ratio (r=0.48) and verbal fluency (r=-0.27), experience time with verbal fluency (r=-0.30) significant correlations were observed.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between language variables and executive functioning in children aged 5 to 8 years with and without DLD. The linguistic variables investigated in this research included type token ratio, number of utterances, syntactic complexity, syntactic comprehension, repetition and verbal fluency. Among the executive functions, two skills of selective attention and problem-solving/organization were evaluated. The results of the examination of language functions showed that the average scores of children without DLD in the verbal fluency test were higher than the group with DLD, however, there was no significant difference between the normal group and the group with DLD in this task (P<0.05). This finding was consistent with the results of Marini’s study [45]. In his study, children with DLD responded similarly to the normal group in terms of the number of items mentioned in each semantic class (household appliances, animals). However, the findings of the research are not aligned with the results of the Henry’s study [46]. This lack of alignment can be because semantic and phonetic verbal fluency has been investigated in this study and it has emphasized speed, number of errors, and change of clusters. Even in Ralli et al.’s study [21], it was demonstrated that children with DLD showed higher scores in the verbal fluency task. According to the different and sometimes contradictory findings in this field, this skill in children with DLD still needs further investigation. The two groups had significant differences only in the indexes of linguistic complexity and syntactic understanding (P<0.05). This finding is in line with the reports of Haresabadi et al. [28] and Hughes [23] who showed that language deficits, especially grammar, were impaired in these children. These deficits can occur both at the level of expression and at the level of comprehension. Paul also believes that these children are impaired at different linguistic levels, including syntax, semantics, phonology and grammar and the delay patterns show that our findings in this section are in line with Paul’s findings and theories [47]. According to the study by Nilipour et al. [39], children with DLD have serious deficits in syntactic understanding and mean length of utterance. Therefore, these two indexes can be used to diagnose DLD in the developmental Persian language battery.

Examination of the selective attention showed that the two groups did not have significant differences in any of the components of selective attention, i.e. correct answers in the Stroop test (t=1.423, P>0.05) and reaction time (t=1.604, P>0.05). This finding is contrary to the results of previous studies, including Kapa and Erikson’s research [17]. This discrepancy may be due to the difference in the tools used. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate this skill in children with DLD in future studies using other tests and in larger samples.

Examining problem-solving/organization skills in normal children and children with DLD showed that the two groups showed a significant difference in the number of errors committed in the tower of London test (t=2.740, P<0.01). These results are consistent with the findings of the study of Bishop and Norbury [3] and Vugs et al. [24]. In all these studies, children with DLD have performed weaker than their normal peers in organization and problem-solving skills.

Examining the relationship between linguistic variables and executive function variables showed a positive and significant correlation between the two components of the total score of selective attention and verbal fluency. The better the selective attention skill in children, the better verbal fluency has been seen in them. According to the study by Kapa and Erikson, there is a significant correlation between the two skills of selective attention and vocabulary learning in children with DLDs [17]. Previous findings, such as the studies of Molinari and Leggio [48] (2016) and Lezak [49] (2010) confirm the results of the present study. According to their research, it was seen that verbal fluency is strongly influenced by executive functions, especially attention and working memory. Also, the variety and range of words and how they are organized in the brain are related to the capacity of working memory and attention.

In examining the relationship between problem-solving/organization skills and language variables, between the components of the total score with type-token ratio (r=0.68) and syntactic understanding (r=0.52), total time with the number of utterances (r=0.46) and verbal fluency (r=0.32), delay time with type-token ratio (r=0.48) has a positive and significant correlation. Therefore, the better the problem-solving/organization skills in childhood, the more varied the type-token ratio, better syntactic understanding, more utterances, and better verbal fluency. On the other hand, a negative and significant correlation has been seen between the delay time with verbal fluency (r=-0.27) and the task completion time with verbal fluency (r=-0.30). The longer the subject’s response time to the task presented in the Tower of London test, the lower their verbal fluency score. Also, the longer the task was completed, the lower the child’s verbal fluency score. Considering that the development of problem-solving skills begins between the ages of 3 and 5 years [50] and this stage coincides exactly with the stage of language development in which the sudden growth of syntactic and grammatical skills is seen in the child [47], the correlation In the important aspects of grammar and syntax, including type-token ratio, verbal fluency, number of utterances, and syntactic understanding, it can be explained with problem-solving/organizational performance in these children by relying on the simultaneity of the evolutionary developmental stages of these two skills.

Conclusion

Executive function deficits can be related to language impairments. One of the possible explanations can be the initial formation process of executive functions during growth. To reject or confirm this assumption, more investigations are needed using more accurate tools. Also, the use of non-linguistic assessment tools can provide more accurate information, because among the observations during implementation in this research, there was a deficiency in the verbal understanding of the test instructions and, on the other hand, a weakness in memorizing the rules of the tests. If it is possible to use measurement methods that involve fewer aspects of receptive and expressive language, we can say with more certainty the causal relationships between executive functions and language skills. According to the results of this research, it is necessary to examine cognitive skills, including executive functions, in the evaluation and treatment planning of children with DLD. Because it seems that a deficit in executive functions can affect their language skills. Despite the studies done so far, the relationship between executive functions and language skills is still not well known. Therefore, there is a need to conduct more research in this field with more accurate tools, more subjects, and control of interfering factors. Nevertheless, improved language skills following executive function-focused treatments have provided initial support for a causal role of executive function in language deficits among children with DLD.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1394.124). The study objectives were explained to the parents of children and they were assured of the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study at any time. While paying attention to children’s mental states and fatigue, efforts were made to respect their dignity and human rights during the research.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master thesis of Hoda Mowzoon, approved by University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (register No.: 911673012).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Hoda Mowzoon and Reza Nilipour; Methodology and data analysis: Hoda Mowzoon and Zahra Ghoreishi; Data collection: Hoda Mowzoon; Writing–original draft: Hoda Mowzoon and Fatemeh Hasanati; Editing and final approval: Hoda Mowzoon, Fatemeh Hasanati and Mohammad Reza Mohammadzamani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the speech therapists’ families and children for their cooperation in this study.

Developmental language disorder (DLD) describes individuals who, during a known biomedical condition, have problems with language that affect daily functioning and lifelong functioning [1]. Until 2017, this disorder was known as specific language impairment (SLI); however, Bishop proposed the label of DLD for SLI this year. In this disorder, despite having intellectual, social, emotional and normal hearing functions, the child is delayed in acquiring language skills. These children have major deficits in language learning and will not be able to compensate for these deficits until the age of 5 years [2]. This disorder is common and it is estimated that on average two children in each class have this disorder [3]. Children with DLD have different degrees of damage in different parts of language comprehension and expression. These damages are manifested in the aspects of semantics and grammar [4]. For example, this has been observed in various studies that these children have a shorter mean length of utterance. They also have limitations in the use of syntactic structures [5] and weaker performance in vocabulary development, word definition [6], and storytelling [7]. Studies conducted in recent years on this disorder have shown that these children are not only impaired in language skills but also in other skills, including cognitive skills [4-6]. Among the cognitive domains that have been investigated in these children in recent years is the domain of executive functions. Executive functions play an important role in language processing [8] and they are one of the underlying processes involved in cognitive performance. These processes include behaviors such as self-regulation, self-initiation, cognitive flexibility, planning, response inhibition, sustained attention, selective attention, shifting, organizing, and working memory [9]. These skills are involved in solving complex and new problems and it is thought that they arise through language [10]. In this research, two skills of selective attention and problem-solving/organization have been investigated. Selective attention means avoiding the interference of irrelevant information (either as a dominant response or as a non-dominant response) and choosing information related to the goal [11]. The organization also includes a series of stages of problem analysis, testing solutions, creating possible solutions, and modifying behavior or changing strategies when a solution is not successful. This ability is often associated with the prefrontal cortex [12، 13]. Research conducted on the relationship between executive function and language processing in children with DLD shows that tasks related to language processing, such as sentence comprehension are largely influenced by executive function [14]. Many children with DLD perform at a slower speed in cognitive tasks and complex language tasks than their normal peers, and their performance patterns are different [15-20]. One of the reasons for these problems, or at least part of them, can be the existence of deficits in executive functions. However, due to the few studies conducted in this area on children with DLD, this disorder is still not well understood [21، 22]. Various studies have investigated specific aspects of executive function, such as working memory and inhibitory responses in children and adults with DLD. For example, according to several studies, children with DLD have deficits in verbal working memory. These deficits have been shown in various tasks, such as non-word repetition, listening span, and dual processing of sentence comprehension [22، 23]. Vugs et al. (2014) in a study investigated executive functions, including working memory in children with DLD. The results of this study showed that children with DLD performed weaker than normal peers in cognitive skills including working memory in both the verbal and visual-spatial sections. Deficits in executive functions included problems in shifting, inhibition, planning/organization and emotional control, and the relationship pattern between working memory function and executive function behaviors was also different in the two groups [24]. Flores CamasCamas and Leon-Rojas (2023), who reviewed the studies conducted in the field of SLI and executive function in school-age children, stated that the cognitive skills of children with SLI in terms of inhibition, processing capacity, planning and organization, attention, verbal reasoning, and logic are limited. Accordingly, they have fewer cognitive resources and cannot use them effectively. The findings of this study showed that children with SLI have deficits, low academic performance, and sometimes, serious disorders in the development of executive function compared to normal peers aged 3 to 4 years. The most observed changes were in attention, working memory (including auditory memory, phonological memory, and visual/verbal memory), processing speed, planning, inhibition, cognitive flexibility and inner speech. The above results are due to the view that language development may have a significant impact on the acquisition and development of executive function, and both of them are necessary for cognitive development [25]. Blom and Boerma (2019) examined the relationship between language skills and executive functions with lexical and syntactic development in 117 children with and without DLD. Their study showed that both groups showed stable lexical and growth in syntactic skills. In children with DLD, syntactic skills and executive functioning, including interference control, selective attention, and working memory were predictive of vocabulary skills. However, in the group of normal children, vocabulary skills were predictive of executive performance. The mean scores of selective attention and interference control in children with DLD were higher than the group of normal children, but in working memory tasks, normal children obtained higher scores [26]. Kapa and Erickson (2020) also examined the relationship between executive function and word learning in normal preschool children and children with DLD. The results showed that the performance of children with DLD in all sections of executive function, including shifting, short-term memory, working memory, selective attention, inhibition and language skills of word learning was weaker than normal peers. The findings showed that children with DLD were weaker in word learning than normal peers, and also preschoolers were weak in learning new words for familiar objects. The results of this study support the relationship between executive function and vocabulary learning in children with and without DLD [17]. In another study, Ralli et al. (2021) examined working memory, executive function, and verbal fluency concerning non-verbal intelligence in Greek-speaking school-age children. The studied age group was 8 to 9 years old and included one group of children with DLD and another matched normal group. Data analysis showed that children with DLD have earned scored lower in non-verbal intelligence measures than the normal peer group, but had better scores in working memory capacity, verbal fluency (phonetic and semantic), updating, and monitoring [21]. Finneran et al. (2009) studied sustained attention in the two components of accuracy and response time. The results showed that children with DLD had a weaker performance than the normal group in terms of accuracy, but their response speed was not significantly different from the normal group [27]. Among the researchers conducted in Iran, we can refer to Haresabadi et al.’s study (2021), in which they investigated grammatical and lexical language functions and theory of mind skills in two groups of children with high-functioning autism and DLD and compared them with normal children. The results of this research showed that both groups of children with impaired skills performed worse than their normal peers [28]. Also, Yazdani et al. (2012) investigated the effect of non-word repetition tasks on the linguistic variables of children with DLD. According to this research, most of the studied children showed improvement in their language indicators [29]. Despite the studies that have investigated executive function in children with DLD worldwide [30] and in Iran [28، 29], the relationship between executive function and language deficits is still unknown. Considering that most of these studies have been conducted on English-speaking children [31], it is necessary to produce similar research in the Persian language. Due to the importance of executive function in developmental disorders, many studies have been conducted on executive function in other developmental disorders such as autism, learning disability, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [32-36]. Understanding the relationship between language skills and executive function in children with DLD is essential for clinical use in this field because by identifying the side areas of disorders in these children, a more suitable treatment program can be designed for the weak aspects of language. On the other hand, by more closely examining the relationship between different aspects of language skills and executive functions, existing theories in this field can be improved. In this study, those linguistic skills were investigated, and according to various studies, DLD children have more problems in this field and are often considered as a criterion for differential diagnosis of children with and without DLD [7]. Also, selective attention was chosen from executive functions because it is a basic skill and most executive functions are based on it [37]. Also, the skill of organization/problem solving was chosen as a skill that has existed since the beginning of children’s development and gradually grows, and having this knowledge does not necessarily mean solving the existing problem. Rather, it can facilitate the transfer of knowledge from one situation to another [38]. Hence, this study investigates the relationship between linguistic variables (including type-token ratio, number of utterances, syntactic complexity, syntactic comprehension, repetition and verbal fluency) and executive function (including selective attention and organization/problem-solving) in 5 to 8-year-old Persian-speaking children with and without DLD.

Materials and Methods

The current study is descriptive-analytical and cross-sectional-comparative, in which the subjects were evaluated using executive functions and language assessment tools. The studied sample included 56 normal children (26 boys and 30 girls) 5 to 8 years old (preschool, first and second elementary school) and 20 children with DLD (12 boys and 8 girls) 5 to 8 years old (preschool, first and second elementary school). These two groups were matched in terms of intelligence quotient (general intelligence quotient above 85 in the Wechsler test), chronological age and educational level. Children with DLD were selected from the available sampling method among the referrals to learning disability centers and public and private rehabilitation clinics in Tehran City, Iran, according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A cluster sampling method was used to sample the children of the peer group. First, several normal schools from 10 schools in 5 education regions of Tehran City, Iran, including regions 10, 9, 8, 1 and 16 and then the number of classes in each school and the number of students in each class were randomly selected. The inclusion criteria were being 5 to 8 years old, monolingual in Persian, having normal non-verbal intelligence (85 and above in the Wechsler test) and also for the group with DLD (based on the diagnostic criteria), obtaining a language test score of at least 2 standard deviations (in one of the language tasks) or at least 1.5 standard deviations (in two or more language tasks) lower than their age peers (using the Persian language development test). Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria included having any neurological disease and accompanying psychiatric disorders and having any visual or hearing impairment. To ensure the health of normal children, the child’s medical file was first referred to, and then two researcher-made reporting forms (one for the teacher and one for the parents) were completed. To diagnose children with disorders, reporting forms (parents and teachers) in addition to the clinical diagnosis of 3 expert speech therapists (with an average professional age of 8 years who were active in the field of assessment and treatment of developmental disorders) based on DLD diagnostic criteria [1] and Persian language developmental battery [39] were used. After entering the desired samples into the study, the informed consent form and history taking were presented to the parents. After ensuring the ability of the subjects to work with the computer and familiarizing themselves with the instructions for the test provided by the researcher, the neuropsychological computer tests of the tower of London, day and night Stroop [40], verbal fluency [41] and parts of the Persian language developmental battery [39] was done by the participants.

Study measurements and implementation methods

After selecting children with and without DLD, children of both groups were evaluated in terms of language skills and executive functions. In the following, the structure and implementation method of the used tests are explained.

Tower of London test

The tower of London test is designed to evaluate at least two aspects of executive functions: Strategic planning and problem-solving. The test used in this research was prepared by the Sina Institute of Psychological Products. This test has good construct validity in measuring people’s planning and organization. A correlation of 0.41 has been reported between the results of this test and the Proteus maze test. The reliability of this test is accepted and reported as 0.79 [42]. In this test, the subject makes the shape of the sample by moving the colored plates (green, blue, red) and placing them in the right place, with the minimum necessary movements. In each stage, the person is allowed to solve the problem 3 times and the person must solve the example according to the instructions with the minimum necessary moves. At each stage, after success (and if the problem is not solved after 3 attempts), the next problem is provided to the subject. The variables of this test (the data obtained from this test) are total time, delay time, experience time, number of errors, and total score.

Day and night stroop test

The day and night stroop test is the most widely used Stroop measure used for children. This task was first designed by Gerstadt et al. in 1994. Accordingly, two sets of cards are used as follows: One set for the day and night condition and one set for the control condition. The examiner asks the subject to call it day when they see the image of the moon and call it night when they see the image of the sun. The images are presented to the subject in order (according to the predetermined sequence) and the results are recorded. The recorded information of this task included: the correct answers of the subject, the delayed response in each item, and the delayed response in all items. The validity of this assignment is 90 [40]. In this study, this task was implemented using the DMDX software, version 4 The sequence of 16 images of the moon and the sun was designed in computer form (according to the original pattern of the initial test) and the children’s answers were recorded orally using a microphone and in written form. The microphone was fixed on the microphone stand at a distance of 15-20 cm from the subject. The time interval between each item and the next item was considered to be 2000 ms. To check the internal validity of the DMDX measurement tool, the Cronbach α test was performed on the items of this tool. According to the results, the Cronbach α estimated for this tool is 0.899, which is considered excellent for research purposes. In this research, this task was used to investigate selective attention. Meanwhile, to investigate the linguistic variables, the verbal fluency task and Persian language developmental battery have been used. The measured variables included verbal fluency (semantic), type-token ratio, number of utterances, complexity, and syntactic understanding and repetition.

Persian language developmental battery

The Persian language developmental battery was designed by Nilipour in 2015 as a research project at the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, and it is based on the Gopnic 5 test. It was then developed after cultural and linguistic adaptions for the Persian language. The Cronbach α (internal consistency coefficient) of this test, which was performed on 60 Persian-speaking 5-10-year-old children, was 0.9. This test has 9 sub-tests to evaluate language skills, which include pointing, grammatical judgment, grammatical modification, derivational morphemes, verb tense, listening comprehension, Vag test, syntactic comprehension, and repetition. After the test, the language profile of each child with DLD was obtained in each of the above nine subtests [39].

Verbal fluency test

Verbal fluency is examined in the two following ways: Semantic fluency and phonemic fluency [41]. In the current research, semantic fluency was considered. There are several tests to assess this skill, but the most common one is naming fruits and animals to evaluate semantic fluency [43]. These tasks are often used in neuro-psychological evaluations and research projects [44]. In this test, the subject was asked to remember and say as many names of fruits and animals (first from the group of fruits and then from the group of animals) within 1 min (for each semantic category). The number of spoken words (repeated words, words that were not included in the intended semantic classes, or self-made words are not counted) were counted and compared and analyzed. The research data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 18. Meanwhile, to analyze the data, the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to check the data distribution, the independent t-test was used to check the difference between the two studied groups, and the Pearson correlation was used to check the relationship between executive function and language deficits in children with DLD.

Results

Considering that the distribution of data in the normal and impaired group in language skills and executive functions was normal (P>0.05), using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, parametric tests were conducted to compare the variables. Table 1 demonstrates the demographic information of the subjects.

Meanwhile, Table 2 shows the Mean±SD and independent t-test results in language variables to inspect the difference between the two groups in these components.

According to Table 2, the average language scores of the group without DLD are higher than the group of children with DLD, but this difference in verbal fluency test was not significant between the two groups. Also, the mean type token ratio, the number of utterances, and repetition did not differ significantly (P>0.05). There was a significant difference between the two groups in linguistic indexes of complexity and syntactic understanding (P<0.05).

To compare the ability of the two research groups in selective attention, as one of the components of executive functions, the day and night Stroop test was used. Table 3 shows the Mean±SD of the scores related to the number of correct answers as well as the reaction time to the Stroop test items, as well as the results of the independent groups t-test to study the significant differences between the two groups in this component.

According to Table 3, the two groups did not show any significant difference in reaction time or any of the components of selective attention, which indicates the correct answers in the Stroop test (P>0.05).

The tower of London test was used to compare two groups of subjects in problem-solving/organization ability, as one of the components of executive functions. Table 4 demonstrates the Mean±SD of scores related to the number of errors, overall score, overall test time, delay time, and experience time, as well as the results of the t-test of independent groups to identify notable differences between the two groups.

According to Table 4, two groups showed a significant difference in the number of errors for problem-solving skills (P<0.05). There was no serious difference between the two groups for other components.

To investigate the relationship between executive functions and language deficits in children with DLD, the Pearson correlation was used. The results of this study are shown in Table 5.

According to the results of Table 5, in examining the relationship between selective attention skill and verbal fluency variable, a positive and significant correlation (r=0.30) was observed only between the two components of the total score of selective attention and verbal fluency. Concerning problem-solving/organizing skills, between the components of the total score with type-token ratio (r=0.68) and syntactic understanding (r=0.52), total time with the number of utterances (r=0.46) and verbal fluency (r=0.32), delay time with type-token ratio (r=0.48) and verbal fluency (r=-0.27), experience time with verbal fluency (r=-0.30) significant correlations were observed.

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between language variables and executive functioning in children aged 5 to 8 years with and without DLD. The linguistic variables investigated in this research included type token ratio, number of utterances, syntactic complexity, syntactic comprehension, repetition and verbal fluency. Among the executive functions, two skills of selective attention and problem-solving/organization were evaluated. The results of the examination of language functions showed that the average scores of children without DLD in the verbal fluency test were higher than the group with DLD, however, there was no significant difference between the normal group and the group with DLD in this task (P<0.05). This finding was consistent with the results of Marini’s study [45]. In his study, children with DLD responded similarly to the normal group in terms of the number of items mentioned in each semantic class (household appliances, animals). However, the findings of the research are not aligned with the results of the Henry’s study [46]. This lack of alignment can be because semantic and phonetic verbal fluency has been investigated in this study and it has emphasized speed, number of errors, and change of clusters. Even in Ralli et al.’s study [21], it was demonstrated that children with DLD showed higher scores in the verbal fluency task. According to the different and sometimes contradictory findings in this field, this skill in children with DLD still needs further investigation. The two groups had significant differences only in the indexes of linguistic complexity and syntactic understanding (P<0.05). This finding is in line with the reports of Haresabadi et al. [28] and Hughes [23] who showed that language deficits, especially grammar, were impaired in these children. These deficits can occur both at the level of expression and at the level of comprehension. Paul also believes that these children are impaired at different linguistic levels, including syntax, semantics, phonology and grammar and the delay patterns show that our findings in this section are in line with Paul’s findings and theories [47]. According to the study by Nilipour et al. [39], children with DLD have serious deficits in syntactic understanding and mean length of utterance. Therefore, these two indexes can be used to diagnose DLD in the developmental Persian language battery.

Examination of the selective attention showed that the two groups did not have significant differences in any of the components of selective attention, i.e. correct answers in the Stroop test (t=1.423, P>0.05) and reaction time (t=1.604, P>0.05). This finding is contrary to the results of previous studies, including Kapa and Erikson’s research [17]. This discrepancy may be due to the difference in the tools used. Therefore, it is necessary to investigate this skill in children with DLD in future studies using other tests and in larger samples.

Examining problem-solving/organization skills in normal children and children with DLD showed that the two groups showed a significant difference in the number of errors committed in the tower of London test (t=2.740, P<0.01). These results are consistent with the findings of the study of Bishop and Norbury [3] and Vugs et al. [24]. In all these studies, children with DLD have performed weaker than their normal peers in organization and problem-solving skills.

Examining the relationship between linguistic variables and executive function variables showed a positive and significant correlation between the two components of the total score of selective attention and verbal fluency. The better the selective attention skill in children, the better verbal fluency has been seen in them. According to the study by Kapa and Erikson, there is a significant correlation between the two skills of selective attention and vocabulary learning in children with DLDs [17]. Previous findings, such as the studies of Molinari and Leggio [48] (2016) and Lezak [49] (2010) confirm the results of the present study. According to their research, it was seen that verbal fluency is strongly influenced by executive functions, especially attention and working memory. Also, the variety and range of words and how they are organized in the brain are related to the capacity of working memory and attention.

In examining the relationship between problem-solving/organization skills and language variables, between the components of the total score with type-token ratio (r=0.68) and syntactic understanding (r=0.52), total time with the number of utterances (r=0.46) and verbal fluency (r=0.32), delay time with type-token ratio (r=0.48) has a positive and significant correlation. Therefore, the better the problem-solving/organization skills in childhood, the more varied the type-token ratio, better syntactic understanding, more utterances, and better verbal fluency. On the other hand, a negative and significant correlation has been seen between the delay time with verbal fluency (r=-0.27) and the task completion time with verbal fluency (r=-0.30). The longer the subject’s response time to the task presented in the Tower of London test, the lower their verbal fluency score. Also, the longer the task was completed, the lower the child’s verbal fluency score. Considering that the development of problem-solving skills begins between the ages of 3 and 5 years [50] and this stage coincides exactly with the stage of language development in which the sudden growth of syntactic and grammatical skills is seen in the child [47], the correlation In the important aspects of grammar and syntax, including type-token ratio, verbal fluency, number of utterances, and syntactic understanding, it can be explained with problem-solving/organizational performance in these children by relying on the simultaneity of the evolutionary developmental stages of these two skills.

Conclusion

Executive function deficits can be related to language impairments. One of the possible explanations can be the initial formation process of executive functions during growth. To reject or confirm this assumption, more investigations are needed using more accurate tools. Also, the use of non-linguistic assessment tools can provide more accurate information, because among the observations during implementation in this research, there was a deficiency in the verbal understanding of the test instructions and, on the other hand, a weakness in memorizing the rules of the tests. If it is possible to use measurement methods that involve fewer aspects of receptive and expressive language, we can say with more certainty the causal relationships between executive functions and language skills. According to the results of this research, it is necessary to examine cognitive skills, including executive functions, in the evaluation and treatment planning of children with DLD. Because it seems that a deficit in executive functions can affect their language skills. Despite the studies done so far, the relationship between executive functions and language skills is still not well known. Therefore, there is a need to conduct more research in this field with more accurate tools, more subjects, and control of interfering factors. Nevertheless, improved language skills following executive function-focused treatments have provided initial support for a causal role of executive function in language deficits among children with DLD.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1394.124). The study objectives were explained to the parents of children and they were assured of the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study at any time. While paying attention to children’s mental states and fatigue, efforts were made to respect their dignity and human rights during the research.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master thesis of Hoda Mowzoon, approved by University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (register No.: 911673012).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Hoda Mowzoon and Reza Nilipour; Methodology and data analysis: Hoda Mowzoon and Zahra Ghoreishi; Data collection: Hoda Mowzoon; Writing–original draft: Hoda Mowzoon and Fatemeh Hasanati; Editing and final approval: Hoda Mowzoon, Fatemeh Hasanati and Mohammad Reza Mohammadzamani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the speech therapists’ families and children for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Bishop D, Snowling MJ, Thompson P, Greenhalgh T, Consortium C, Bishop DVM. A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study. Identifyirments in children. Plos One. 2016; 11(7):26. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0158753]

- Bishop DVM, Snowling MJ, Thompson PA, Greenhalgh T, Bishop DVM. Phase 2 of CATALISE:A multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2017; 58(10):1068-80. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12721]

- Norbury CF, Sonuga-Barke E. New frontiers in the scientific study of developmental language disorders. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry. 2017; 58(10):1065-7. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12821]

- Engel de Abreu PM, Cruz-Santos A, Puglisi ML. Specific language impairment in language-minority children from low-income families. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2014; 49(6):736-47. [DOI:10.1111/1460-6984.12107]

- Ghayoumi-Anaraki Z, Haresabadi F, Maleki Shahmahmood T, Ebadi A, Vakili V, Majidi Z. The grammatical deficits of Persian-speaking children with specific language impairment. Journal of Rehabilitation Sciences & Research. 2017; 4(4):102-8.[DOI:10.30476/jrsr.2017.41127]

- Mohammadi M, Nilipoor R, Shirazi TS, Rahgozar M. [Semantic differences of definitional skills between persian speaking children with specific language impairment and normal language developing children (Persian)]. Journal of Rehabilitation. 2011; 12(2):48-55. [Link]

- Shahmahmood TM, Soleymani Z, Faghihzade S. [The study of language performances of Persian children with specific language impariment (Persian)]. Audiology. 2011; 20(2):11-21. [Link]

- Engle RW, Kane MJ, Tuholski SW. Individual differences in working memory capacity and what they tell us about controlled attention, general fluid intelligence, and functions of the prefrontal cortex. In: Miyake A, editor. Models of working memory: Mechanisms of active maintenance and executive control. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1999. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9781139174909.007]

- Booth NJ, Boyle ME. Do tasks make a difference? Accounting for heterogeneity of performance of children with reading difficulties on tasks of executive function: Findings from a meta-analysis. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2010; 28(1):43. [DOI:10.1348/026151009X485432]

- Anaya ME, Conway MC, Pisoni BD. Some links between executive function and spoken language processing: Preliminary findings using self-ordered pointing and missing scan tasks [PHD dissertation]. Indiana: Speech Research Laboratory Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences; 2008.

- Fournier VS, Lariguarderie P, Ggaonsch D. More dissociation and interaction within centeral executive functioning: A comprehensive latent variable analysis. Acta Psychology. 2008; 129(1):32-48. [DOI:10.1016/j.actpsy.2008.04.004]

- Miller LA, Tippett LJ. Effects of focal brain lesions on visual problem-solving. Neuropsychologia. 1996; 34(5):387-98. [DOI:10.1016/0028-3932(95)00116-6]

- Baldo JV, Dronkers NF, Wilkins D, Ludy C, Raskin P, Kim J. Is problem solving dependent on language? Brain and Language 2005;92(3):240-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.bandl.2004.06.103]

- Mazuka R, Jincho N, Oishi H. Development of executive control and language processing. Language and Linguistics Compass. 2009; 3(1):59-89. [DOI:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2008.00102.x]

- Pauls LJ, Archibald LMD. Executive functions in children with specific language impairment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research. 2016; 59(5):1074-86. [DOI:10.1044/2016_JSLHR-L-15-0174]

- Plym J, Lahti-Nuuttila P, Smolander S, Arkkila E, Laasonen M. Structure of cognitive functions in monolingual preschool children with typical development and children with developmental language disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2021; 64(8):3140-58. [DOI:10.1044/2021_JSLHR-20-00546]

- Kapa LL, Erikson JA. The relationship between word learning and executive function in preschoolers with and without developmental language disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2020; 63(7):2293-307. [DOI:10.1044/2020_JSLHR-19-00342]

- Im-Bolter N, Johnson J, Pascual-Leone J. Processing limitations in children with specific language impairment: The role of executive function. Child Development. 2006; 77(6):1822-41. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00976.x]

- Marton K. Visuo-spatial processing and executive functions in children with specific language impairment. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2008; 43(2):181-200. [DOI:10.1080/16066350701340719]

- Miller C, Kail R, Leonard L, Tomblin J. Speed of processing in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2001; 44(2):416-33. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2001/034)]

- Ralli AM, Chrysochoou E, Roussos P, Diakogiorgi K, Dimitropoulou P, Filippatou D. Executive function, working memory, and verbal fluency in relation to non-verbal intelligence in greek-speaking school-age children with developmental language disorder. Brain Science. 2021; 11(5):604. [DOI:10.3390/brainsci11050604]

- Marton K, Campanelli L, Scheuer J, Yoon J, Eichorn N. Executive function profiles in children with and without specific language impairment. Rivista di Psicolinguistica Applicatal. 2012;12(3):57-73. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hughes DM. Parent and self-ratings of excecutive function in adolecsents with language impairment and typically developing peers [doctoral dissertation]. Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University; 2006. [Link]

- Vugs B, Hendriks M, Cuperus J, Verhoeven L. Working memory performance and executive function behaviors in young children with SLI. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014; 35(1):62-74. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2013.10.022]

- Flores Camas RA, Leon-Rojas JE. Specific language impairment and executive functions in school-age children: A systematic review. Cureus. 2023; 15(8):e43163. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.43163]

- Blom E, Boerma T. Reciprocal relationships between lexical and syntactic skills of children with developmental language disorder and the role of executive functions. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments 2019; 4:16. [DOI:10.1177/2396941519863984]

- Finneran DA, Francis AL, Leonard LB. Sustained attention in children with specific language impairment (SLI). Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009; 52(4):915-29. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0053)]

- Haresabadi F, Jafarzade H, Rostami M, Abbasi Shayeh Z, Maleki Shahmahmood T, Enayati S, et al. [Comparing theory of mind skills and language performance between children with developmental language disorder, high-functioning autism, and typically developing children (Persian)]. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2021; 31(195):18. [Link]

- Yazdani Z, Shirazi ST, Soleimani Z, Razavi MR, Dolatshahi B. [Determine the effectiveness of non word repetition task on some language indicators in children with specific language impairment (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2013; 14(3):115-23. [Link]

- Verhoeven L, Balkom HV. Classification of developmental language disorders. London: Psychology Press; 2003. [DOI:10.4324/9781410609021]

- Portillo AL. Relations between language and executive function in Spanish-speaking children [master thesis]. Washington: San Jose State University; 2009. [Link]

- Jafari Nodoushan F, Saeedmanesh M, Demehri F. The effects of memory rehabilitation on the executive function of response inhibition in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Middle Eastern Journal of Disability Studies. 2021; 11:204. [Link]

- Agahi A, Shareh H, Toozandehjani H. [The relationship between working memory and fluid reasoning in children with dyslexia: Mediating role of executive functions (Persian)]. Research in Clinical Psychology and Counseling. 2022; [Unpublished]. [DOI:10.22067/tpccp.2022.73586.1205]

- Sheri S, Sedaghat M, Moradi H, Shoakazemi M. [Executive function, learning disorder, neurofeedback, parent-child relationship, perceptual and motor exercises, visual motor coordination (Persian)]. Educational and Scholastic Studies. 2023; 12(2):243-74. [DOI:10.48310/pma.2023.3057]

- Nejati V, Bahrami H, Abravan M, Robenzade S, Motiei H. Executive function and working memory in attention deficit/ hyperactivity disorder and healthy children. Journal of Gorgan University of Medical Sciences. 2013; 15(3):69-76. [Link]

- Hashemi-Nosratabad T, Mahmood-Aliloo M, Gholam-Rostami HA, Nemati-Sogolitappeh F. Comparison of reconstitution of thought executive function in subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder based on barkley,s model. Journal of Clinical Psychology 2010; 2(1):35-9. [DOI:10.22075/jcp.2017.2005]

- Kapa LL, Erikson JA. Variability of executive function performance in preschoolers with developmental language disorder. Seminars in Speech and Language; 2019; 40(04):243-55. [DOI:10.1055/s-0039-1692723]

- Keen R. The development of problem solving in young children: A critical cognitive skill. Annual review of psychology. 2011; 62:1-21. [DOI:10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130730]

- Nilipour R, Qoreishi ZS, Ahadi H, Pourshahbaz, A. [Development and standardization of Persian language developmental battery (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation 2023; 24(2):172-95. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.24.2.2191.5]

- Gerstadt CL, Hong YJ, Diamond A. The relationship between cognition and action: performance of children 3.5-7 years old on a stroop- like day-night test. Cognition. 1994; 53(2):129-53. [DOI:10.1016/0010-0277(94)90068-X]

- Murray L, Chapey R. Assessment of language disorders in adults In: Chapey R. Languag intervention strategies in aphasia and related neurogenic communication disorder. Philiadelphia: Lippincott William & Wilkins; 2001. [Link]

- Khodadoost M, Mashhadi A, Amani H. [Tower of London software (Persian)]. Tehran: Sina Company; 2014.

- Seyedin S, Namdar M, Mehri A, Ebrahimi Pour M, Jalaei S. [Normative data of semantic fluency in adult Persian speakers (Persian)]. Journal of Modern Rehabilitation. 2013; 7(2):13-21. [Link]

- Kosmidis M, Vlahou C, Panagiotaki P, Kiosseoglou G. The verbal fluency task in the Greek population: Normative data, and clustering and switching strategies. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 2004; 10(2):164-72. [DOI:10.1017/S1355617704102014]

- Marini A, Tavano A, Fabbro F. Assessment of linguistic abilities in Italian children with specific language impairment. Neuropsychologia. 2008; 46(11):2816-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.05.013]

- Henry LA, Messer DJ, Nash G. Executive functioning in children with specific language impairment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2011; 53(1):37-45. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02430.x]

- Paul R, Norbury C, Gosse C. Language disorders from infancy through adolescence [Y. Kazemi, Persian trans]. Isfahan: Isfahan University of Medical Sciences; 2007. [Link]

- Molinari M, Leggio M. Cerebellum and verbal fluency (phonological and semantic). In: Mariën P, Manto M, editors. The linguistic cerebellum Academic Press; 2016. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-12-801608-4.00004-9]

- Lezak MD. Neuropsychological Assessmen. NewYork: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Link]

- Best JR, Miller PH, Jones LL. Executive functions after age 5: Changes and correlates. Developmental Review. 2009; 29(3):180-200. [DOI:10.1016/j.dr.2009.05.002]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Speech & Language Pathology

Received: 4/12/2023 | Accepted: 19/02/2024 | Published: 1/10/2024

Received: 4/12/2023 | Accepted: 19/02/2024 | Published: 1/10/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |