Volume 26, Issue 4 (Winter 2026)

jrehab 2026, 26(4): 528-551 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.USWR.REC.1396.308

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sadeghi Sedeh S, FatorehChy S, Akbarfahimi N, Hosseini S A, Dalvand H, Bakhshi E A et al . Effectiveness of the Fall-Proof Rehabilitation Exercise Software on Light Touch and Vibration Sensory Function in Patients with Diabetic Polyneuropathy. jrehab 2026; 26 (4) :528-551

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3686-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3686-en.html

Sahar Sadeghi Sedeh1

, Saeid FatorehChy *2

, Saeid FatorehChy *2

, Nazila Akbarfahimi3

, Nazila Akbarfahimi3

, Seyed Ali Hosseini3

, Seyed Ali Hosseini3

, Hamid Dalvand4

, Hamid Dalvand4

, Enayat allah Bakhshi5

, Enayat allah Bakhshi5

, Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh6

, Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh6

, Saeid FatorehChy *2

, Saeid FatorehChy *2

, Nazila Akbarfahimi3

, Nazila Akbarfahimi3

, Seyed Ali Hosseini3

, Seyed Ali Hosseini3

, Hamid Dalvand4

, Hamid Dalvand4

, Enayat allah Bakhshi5

, Enayat allah Bakhshi5

, Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh6

, Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh6

1- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran. & Department of Occupational Therapy, Iranian Research Center on Aging, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran. ,saeidfatorehchy@yahoo.com

3- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Tehran university of medical sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Biostatics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran.

6- Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Tehran university of medical sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Biostatics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran.

6- Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

Keywords: Diabetic peripheral neuropathy, Fall-proof exercises, Digital rehabilitation, Light touch sensation, Vibration perception

Full-Text [PDF 2817 kb]

(66 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1250 Views)

References

Full-Text: (47 Views)

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a chronic and progressive metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from insulin resistance and impaired beta-cell function. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), over 500 million people worldwide currently live with diabetes, a figure projected to rise to 700 million by 2045 [1].This escalating prevalence imposes a substantial burden not only on healthcare systems but also on patients and their families, particularly in aging populations such as Iran’s, where the demographic shift toward older adulthood amplifies the socioeconomic and clinical challenges of chronic disease management [2].

Among the most debilitating chronic complications of diabetes is diabetic peripheral neuropathy, affecting 30–50% of patients and marked by progressive damage to sensory, motor, and autonomic nerve fibers. Sensory manifestations—including diminished light touch sensation, impaired proprioception, and elevated vibration perception thresholds—directly compromise postural control, gait stability, and functional mobility, thereby significantly increasing fall risk in elderly populations [3]. Supporting this, Sadeghi Sedeh et al. (2023) demonstrated that diabetic patients, particularly those with confirmed diabetic polyneuropathy (DPN), exhibit markedly reduced scores on the BBS and diminished strength in distal ankle muscles compared to non-neuropathic controls. This muscular weakness, especially in the ankle dorsiflexors and plantar flexors, contributes to functional balance deficits and altered gait patterns, further elevating fall susceptibility [4].

Given the absence of pharmacological interventions capable of fully restoring neural function in DPN, clinical emphasis has shifted toward sensorimotor rehabilitation strategies. Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials indicate that targeted strengthening of lower limb musculature—particularly around the ankle joint—can improve plantar pressure distribution, joint mobility, walking speed, nerve conduction velocity, and peripheral sensory function in diabetic patients [5, 6]. Moreover, flexibility and resistance training programs for the foot and ankle have been shown to reduce recurrence rates of diabetic foot ulcers, mitigate neuropathic symptom severity, enhance gait efficiency, and ultimately contribute to fall prevention [7-10]. Supervised, structured exercise regimens, when coupled with consistent follow-up, have proven effective in reducing DPN-related sensory deficits [11, 12], improving vibration perception [13], restoring ankle mobility [14], optimizing plantar pressure distribution during ambulation [15], and enhancing overall lower limb strength and function [16, 17].

Among rehabilitative approaches, Fall-Proof exercises have emerged as a comprehensive, evidence-based intervention designed specifically for fall prevention in older adults [18]. These multimodal exercises integrate static and dynamic balance training, tactile sensory stimulation, and progressive resistance components to activate peripheral sensory pathways and enhance fundamental postural control mechanisms [19]. A recent systematic review concluded that an 8-week Fall-Proof program (three 40–50-minute sessions per week) significantly improves functional balance and reduces fear of falling in adults over 60, recommending its adoption as both a preventive and therapeutic modality following initial assessment and proper instruction [20]. Studies on healthy older adults corroborate these findings: Khazanin et al. [21] reported significant reductions in fall incidence and improved postural strategies following an 8-week fall-proof intervention, while other research has documented enhanced tactile sensitivity and vibration perception following balance-focused training. These improvements are attributed to increased peripheral sensory feedback, which facilitates neural pathway activation and proprioceptive recalibration.

However, a close examination of existing resources reveals that most studies conducted in the field of fall-prevention exercises have focused on healthy or low-risk populations, with little attention given to elderly individuals with diabetic polyneuropathy (DPN), who are among the highest-risk groups for falls and neuropathic complications. Additionally, fall-prevention exercises have primarily been implemented in clinical or group settings in-person, with no structured framework available for their home-based or digital implementation. Moreover, the available resources lack interactive instructional videos and real-time feedback systems to ensure proper execution of exercises by users. Most importantly, no interactive and specialized software for implementing fall-prevention exercises in the diabetic neuropathy population has been designed or evaluated, despite the critical need for such a tool in this patient group [22].

Therefore, there is a significant research and practical gap in the design and evaluation of digital interventions aimed at improving basic sensory functions, especially tactile sensation and vibration perception, in elderly individuals with diabetic neuropathy. Designing a training software that can deliver fall-prevention exercises in a standardized, interactive, and trackable manner could be a crucial step toward enhancing safety, functional independence, and quality of life for these patients.

Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of fall-prevention-based training software on improving tactile sensation and vibration perception in elderly individuals with DPN. This research seeks to provide a practical and scientific response to one of the emerging needs in the field of digital rehabilitation for the elderly diabetic population, and pave the way for the development of cost-effective, scalable, and efficient interventions in home settings. The main hypothesis of this study is that regular use of fall-prevention-based training software can lead to significant improvements in tactile sensation and vibration perception in elderly individuals with DPN, as repetitive and targeted sensory stimulation can facilitate neuroplasticity and functional recovery in the peripheral nervous system.

Materials and Methods

In the first phase, the fall-prevention exercise software was designed and developed in four stages:

Production of instructional videos

Fall-prevention exercises, including static and dynamic balance exercises, ankle muscle strengthening, and foot sensory stimulation, were recorded and edited as short instructional videos (each no longer than 10 minutes). These videos were created in coordination with Rose et al. (the primary designer of fall-prevention rehabilitation exercises) [23].

Content validation

The content validity and face validity of the videos were assessed using content validity ratio (CVR) (minimum acceptable value: 0.78) and content validity index (CVI) (minimum acceptable value: 0.79). A panel of 8 experienced occupational therapists (with at least 5 years of clinical practice) participated in the evaluation, which was based on three main criteria: content necessity, clarity of expression, and relevance to the rehabilitation goals for diabetic neuropathy. The videos were approved based on these criteria.

Technical development

The software was developed using Java (for Android) and PHP/MySQL (for backend). Features such as two-factor authentication, video streaming, a discussion forum, automatic session reminders, and user feedback recording were integrated into the software.

Pilot study

The initial version of the software was tested on 6 patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. The results showed that the software was user-friendly, the instructions were clear, and the session scheduling was appropriate. After making minor adjustments, the final version was prepared for use in the clinical trial.

In the second phase of the study (clinical intervention), patients with type 2 diabetes who had visited the diabetes clinic at Sadeghieh Tahereh Hospital in Isfahan were included in the study. Given the estimated 30% prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy DPN in the diabetic population [24], and considering a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence level, the required sample size for initial screening was estimated to be approximately 280 participants.

After initial screening using the michigan neuropathy screening instrument (MNSI) and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 96 eligible patients were selected. These individuals were randomly assigned into three groups of 32 participants: the in-person intervention group, the virtual intervention group (using the fall-prevention software developed in the study), and the control group.

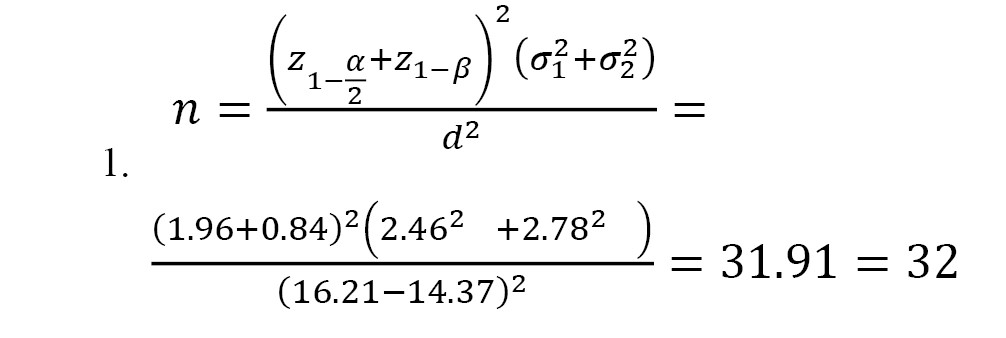

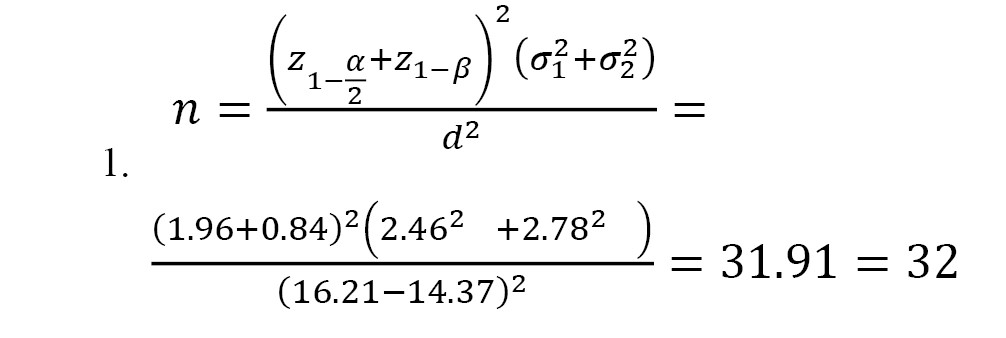

Participant allocation to groups was performed by an independent researcher using the Minimization algorithm [25] to maintain balance between the groups in terms of two key variables: “duration of diabetes” and “severity of DPN.” This algorithm is an adaptive randomization method designed to minimize differences between groups concerning intervening variables (in this study: duration of diabetes and severity of DPN) (Equation 1).

To maintain single-blind assessment, evaluators and statistical analysts were unaware of the group assignments of participants.

Inclusion criteria for the study

1. Age 60 years and older: Given that type 2 diabetes typically begins in the fourth or fifth decade of life and diabetic neuropathy often occurs several years after the onset of the disease, this age range was chosen to focus on the target population with a higher likelihood of developing diabetic peripheral neuropathy [26];

2. Confirmed diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and an active medical record at Sadeghieh Tahereh Hospital in Isfahan: Participants must have visited the diabetes clinic of Sadeghieh Tahereh Hospital at least once in the past six months, with diagnostic and treatment-related information available in the hospital’s electronic health records system. This criterion was applied to ensure diagnostic accuracy, treatment follow-up, and access to valid clinical data for the initial assessment of participants;

3. Presence of signs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy as assessed by the MNSI, with a score ≥2 [27];

4. Ability to walk and maintain balance without the use of assistive devices, with a score greater than 20 on the BBS (BBS) [28];

5. Access to a smartphone for participants in the virtual intervention group;

6. Active participation in at least 90% of the sessions and exercises in the intervention groups;

7. Relatively controlled diabetes, with HbA1c levels less than 8% and blood pressure less than 140/90 mmHg;

8. Ability to provide informed consent and cooperate throughout the study period.

Exclusion criteria

1. Active foot ulcers, lower extremity surgery, or arthroplasty; 2. Diagnosis of severe neurological or cognitive disorders; 3. Receiving concurrent physical therapy or occupational therapy services similar to the intervention; 4. Occurrence of vascular complications or advanced retinopathy.

Inability or unwillingness to continue participation after three follow-up attempts.

Intervention groups

In-person intervention group

Participants in this group performed fall-prevention exercises twice a week (each session lasting 40 minutes with a 10-minute break) in person under the direct supervision of an occupational therapist at the clinic.

Virtual intervention group

After an in-person training session, participants in this group performed exercises at home using the developed software. This Android-based software was installed on the participants’ mobile phones, providing features such as video review, progress tracking, automatic reminders, and the ability to send messages to the therapist. No special equipment was required for home-based exercises, and if participants did not log into the software for more than five days, a reminder SMS was sent, and the researcher followed up.

Control group

The control group received only usual diabetes care including pharmacological treatment, dietary counseling, and lifestyle education, without any exercise intervention.

The fall-proof training followed a progressive structure over eight weeks, with intensity and complexity gradually increased [19, 23]. In weeks 1–2, exercises focused on center-of-mass control, seated weight-shifting, flexibility, and isometric ankle strengthening (12 repetitions, 4–5 sets, 6-second holds). In weeks 3–4, the program included sit-to-stand transfers, static single-leg stance, and dynamic gait tasks with object manipulation (15 repetitions, 8-second holds). In weeks 5–6, multisensory and coordination drills, balance perturbations, and gait pattern enhancement were added (20 repetitions, 10-second holds). In weeks 7–8, participants progressed to advanced postural strategy training, stretching, one-leg transfers with object control, and further progression of gait and balance tasks (25 repetitions, 12-second holds) [19, 23].

Outcomes were assessed at baseline, immediately post-intervention (week 8), and at two and three months after intervention by a trained occupational therapist blinded to group allocation.

Severity of DPN

In this study, the severity of DPN was assessed using the MNSI questionnaire. This tool consists of 15 questions regarding sensory symptoms and foot function. In this questionnaire, a “yes” answer to questions 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, and 15, and a “no” answer to questions 7 and 13, each receive a score of 1. Question 4 relates to circulatory deficiency, and question 10 pertains to the internal validity of the questionnaire (a “lie detection” control question), which are not included in the final score calculation. Therefore, the total score ranges from 0 to 13, with higher scores indicating greater severity of diabetic neuropathy [29].

Tactile sensation

Tactile sensation was assessed using the Semmes-Weinstein 10-gram monofilament on three key areas of the foot (third metatarsal, fifth metatarsal, and hallux) [29, 30].

Vibration sensation

Vibration sensation was assessed using a 128 Hz tuning fork placed on the distal phalanx of the hallux. The time (in seconds) from the start of the vibration until the patient could no longer feel the vibration was recorded [31].

Functional balance

Functional balance was assessed using the Berg balance scale (BBS). This scale consists of 14 items (common activities of daily living), and each item is rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 0 to 4, based on the quality or time spent completing the task. A score of 0 indicates the need for maximum assistance, and a score of 4 indicates the individual’s independence in performing the task. The maximum possible score is 56, which is derived from the sum of scores from various sections of the test. A score between 41 and 56 indicates high balance, meaning a low risk of losing balance and falling. A score between 21 and 40 indicates moderate balance, with a moderate risk of falling, and a score between 0 and 20 indicates low balance, with a high risk of falling. The reliability of each section of the BBS was reported to be 0.98, the reliability of each individual item was 0.99, and the internal consistency was 0.96 [32].

Data distribution was examined with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Between-group comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Walli’s test, within-group changes over time with the Friedman test, and pairwise group comparisons with the Mann–Whitney U test adjusted with Bonferroni correction. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In this single-blind clinical trial, 96 eligible patients were randomly divided into three groups of 32 participants each: In-person intervention, virtual intervention (using the software), and control. The three groups were comparable in terms of baseline variables, including average age (66.93, 67.53, and 67.96 years, respectively; P=0.848), body mass index (24.55, 25.22, and 24.86, respectively; P=0.772), and duration of diabetes (years) (P=0.563).

Additionally, the three groups were similar in terms of HbA1c levels (6.83, 6.70, and 6.93%, respectively; P=0.271), fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) (P=0.938), blood pressure (mmHg) (P=0.703), and the severity of neuropathy as assessed by the MNSI (8.81, 8.28, 8.34, respectively; P=0.649), based on the information in their medical records and clinical examination.

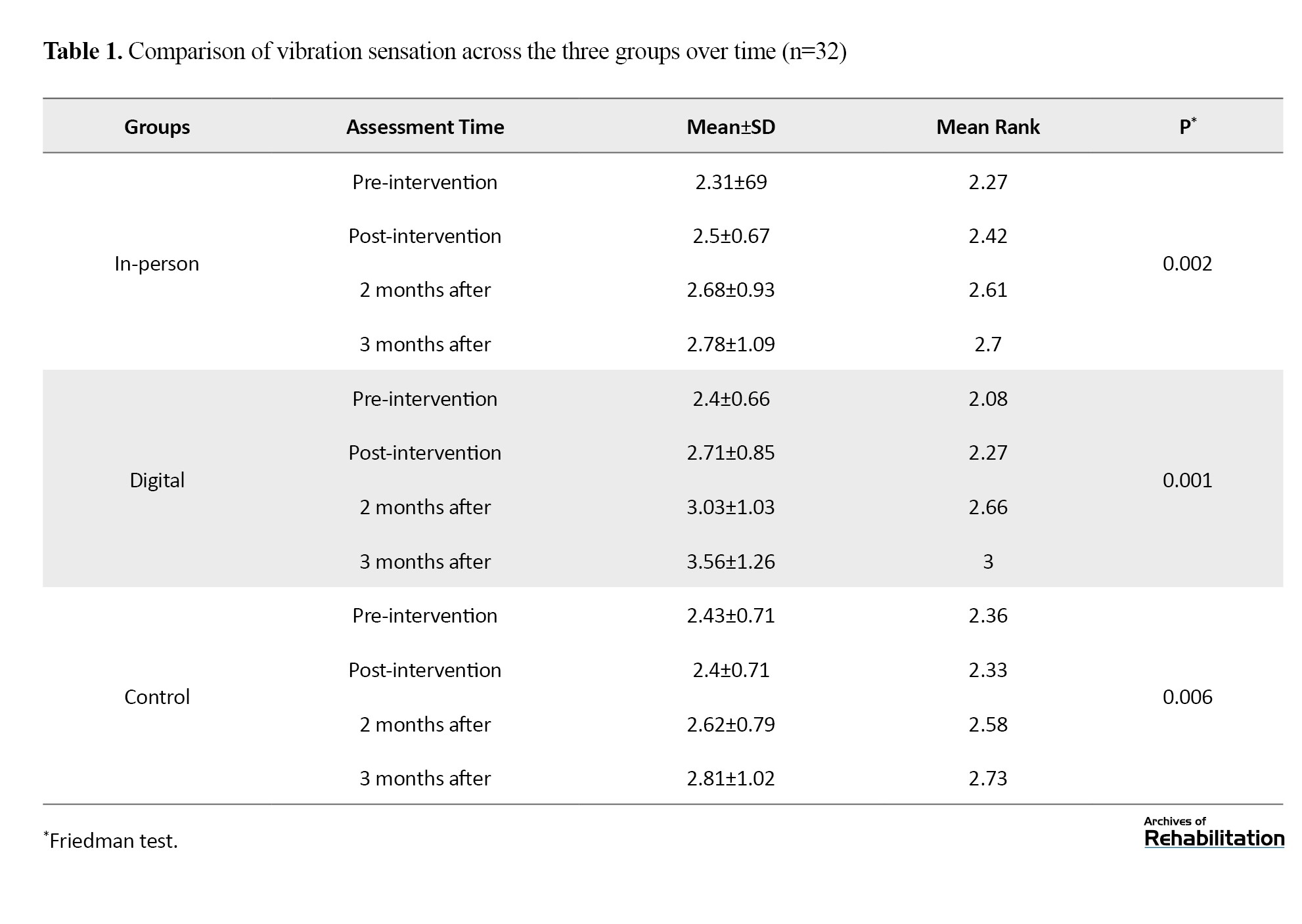

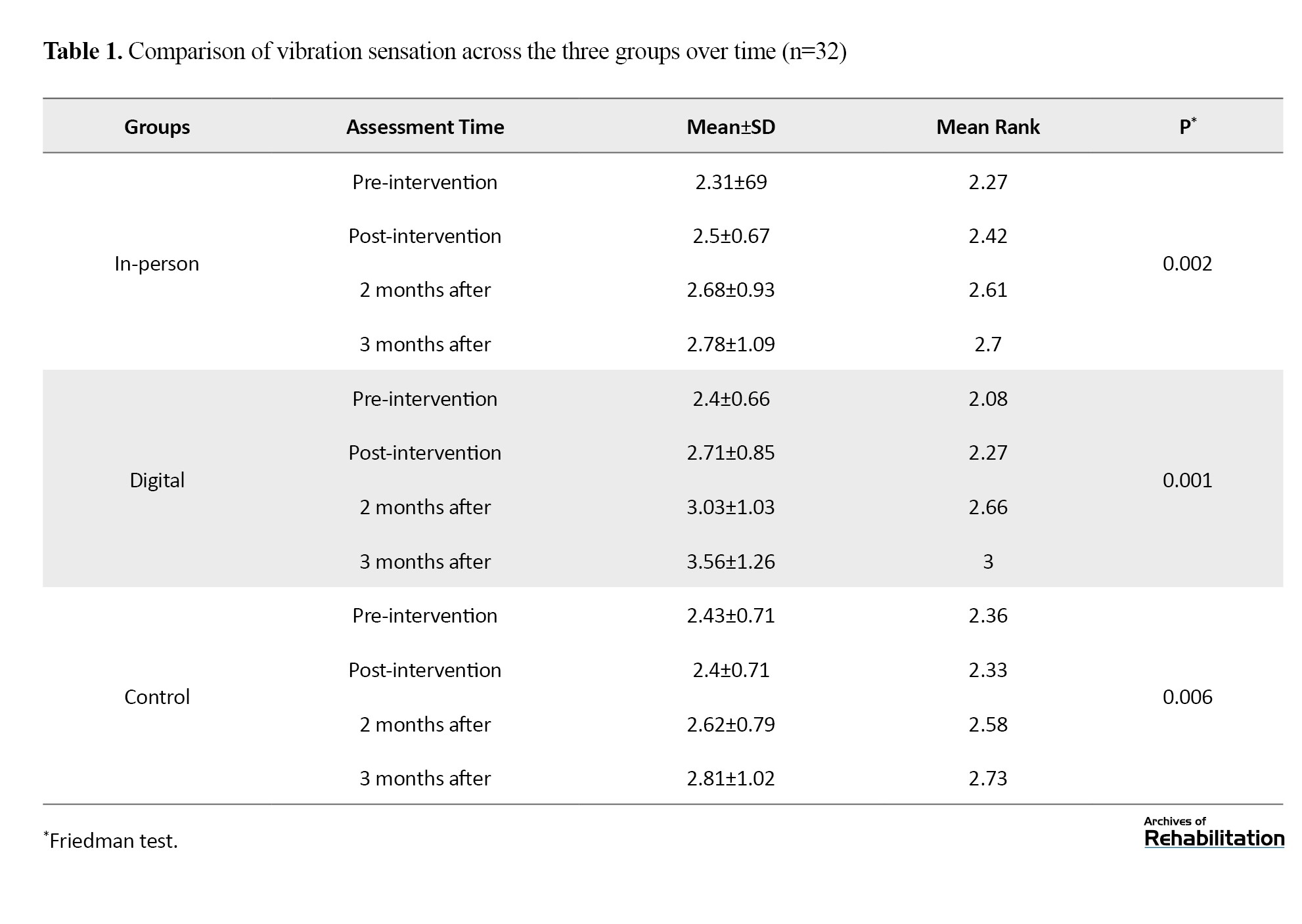

Vibration sensation

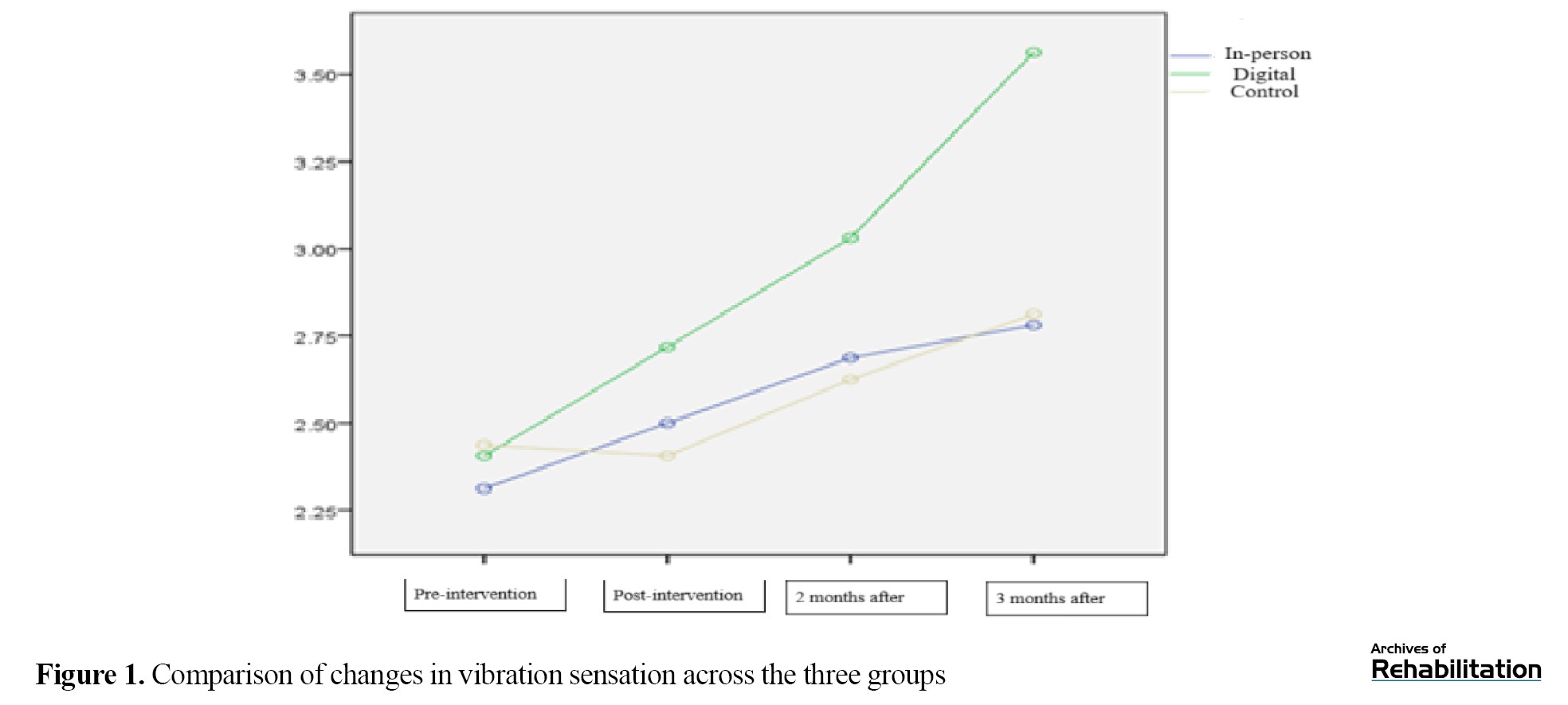

Based on the Kruskal-Wali’s test, there was no significant difference among the three groups in the pretest (P=0.750). After the intervention, both intervention groups (in-person and digital) showed a significant improvement in vibration sensation (P≤0.002), while the control group showed a significant decline (P=0.006). In comparing the groups, the digital intervention led to an increase of 0.359 units and the in-person intervention led to an increase of 0.021 units in vibration sensation. Although the difference between the two intervention groups was not statistically significant (P=0.114), the digital group showed the greatest improvement, and this improvement remained stable up to 3 months after the intervention (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a chronic and progressive metabolic disorder characterized by hyperglycemia resulting from insulin resistance and impaired beta-cell function. According to the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), over 500 million people worldwide currently live with diabetes, a figure projected to rise to 700 million by 2045 [1].This escalating prevalence imposes a substantial burden not only on healthcare systems but also on patients and their families, particularly in aging populations such as Iran’s, where the demographic shift toward older adulthood amplifies the socioeconomic and clinical challenges of chronic disease management [2].

Among the most debilitating chronic complications of diabetes is diabetic peripheral neuropathy, affecting 30–50% of patients and marked by progressive damage to sensory, motor, and autonomic nerve fibers. Sensory manifestations—including diminished light touch sensation, impaired proprioception, and elevated vibration perception thresholds—directly compromise postural control, gait stability, and functional mobility, thereby significantly increasing fall risk in elderly populations [3]. Supporting this, Sadeghi Sedeh et al. (2023) demonstrated that diabetic patients, particularly those with confirmed diabetic polyneuropathy (DPN), exhibit markedly reduced scores on the BBS and diminished strength in distal ankle muscles compared to non-neuropathic controls. This muscular weakness, especially in the ankle dorsiflexors and plantar flexors, contributes to functional balance deficits and altered gait patterns, further elevating fall susceptibility [4].

Given the absence of pharmacological interventions capable of fully restoring neural function in DPN, clinical emphasis has shifted toward sensorimotor rehabilitation strategies. Systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials indicate that targeted strengthening of lower limb musculature—particularly around the ankle joint—can improve plantar pressure distribution, joint mobility, walking speed, nerve conduction velocity, and peripheral sensory function in diabetic patients [5, 6]. Moreover, flexibility and resistance training programs for the foot and ankle have been shown to reduce recurrence rates of diabetic foot ulcers, mitigate neuropathic symptom severity, enhance gait efficiency, and ultimately contribute to fall prevention [7-10]. Supervised, structured exercise regimens, when coupled with consistent follow-up, have proven effective in reducing DPN-related sensory deficits [11, 12], improving vibration perception [13], restoring ankle mobility [14], optimizing plantar pressure distribution during ambulation [15], and enhancing overall lower limb strength and function [16, 17].

Among rehabilitative approaches, Fall-Proof exercises have emerged as a comprehensive, evidence-based intervention designed specifically for fall prevention in older adults [18]. These multimodal exercises integrate static and dynamic balance training, tactile sensory stimulation, and progressive resistance components to activate peripheral sensory pathways and enhance fundamental postural control mechanisms [19]. A recent systematic review concluded that an 8-week Fall-Proof program (three 40–50-minute sessions per week) significantly improves functional balance and reduces fear of falling in adults over 60, recommending its adoption as both a preventive and therapeutic modality following initial assessment and proper instruction [20]. Studies on healthy older adults corroborate these findings: Khazanin et al. [21] reported significant reductions in fall incidence and improved postural strategies following an 8-week fall-proof intervention, while other research has documented enhanced tactile sensitivity and vibration perception following balance-focused training. These improvements are attributed to increased peripheral sensory feedback, which facilitates neural pathway activation and proprioceptive recalibration.

However, a close examination of existing resources reveals that most studies conducted in the field of fall-prevention exercises have focused on healthy or low-risk populations, with little attention given to elderly individuals with diabetic polyneuropathy (DPN), who are among the highest-risk groups for falls and neuropathic complications. Additionally, fall-prevention exercises have primarily been implemented in clinical or group settings in-person, with no structured framework available for their home-based or digital implementation. Moreover, the available resources lack interactive instructional videos and real-time feedback systems to ensure proper execution of exercises by users. Most importantly, no interactive and specialized software for implementing fall-prevention exercises in the diabetic neuropathy population has been designed or evaluated, despite the critical need for such a tool in this patient group [22].

Therefore, there is a significant research and practical gap in the design and evaluation of digital interventions aimed at improving basic sensory functions, especially tactile sensation and vibration perception, in elderly individuals with diabetic neuropathy. Designing a training software that can deliver fall-prevention exercises in a standardized, interactive, and trackable manner could be a crucial step toward enhancing safety, functional independence, and quality of life for these patients.

Thus, the present study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of fall-prevention-based training software on improving tactile sensation and vibration perception in elderly individuals with DPN. This research seeks to provide a practical and scientific response to one of the emerging needs in the field of digital rehabilitation for the elderly diabetic population, and pave the way for the development of cost-effective, scalable, and efficient interventions in home settings. The main hypothesis of this study is that regular use of fall-prevention-based training software can lead to significant improvements in tactile sensation and vibration perception in elderly individuals with DPN, as repetitive and targeted sensory stimulation can facilitate neuroplasticity and functional recovery in the peripheral nervous system.

Materials and Methods

In the first phase, the fall-prevention exercise software was designed and developed in four stages:

Production of instructional videos

Fall-prevention exercises, including static and dynamic balance exercises, ankle muscle strengthening, and foot sensory stimulation, were recorded and edited as short instructional videos (each no longer than 10 minutes). These videos were created in coordination with Rose et al. (the primary designer of fall-prevention rehabilitation exercises) [23].

Content validation

The content validity and face validity of the videos were assessed using content validity ratio (CVR) (minimum acceptable value: 0.78) and content validity index (CVI) (minimum acceptable value: 0.79). A panel of 8 experienced occupational therapists (with at least 5 years of clinical practice) participated in the evaluation, which was based on three main criteria: content necessity, clarity of expression, and relevance to the rehabilitation goals for diabetic neuropathy. The videos were approved based on these criteria.

Technical development

The software was developed using Java (for Android) and PHP/MySQL (for backend). Features such as two-factor authentication, video streaming, a discussion forum, automatic session reminders, and user feedback recording were integrated into the software.

Pilot study

The initial version of the software was tested on 6 patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. The results showed that the software was user-friendly, the instructions were clear, and the session scheduling was appropriate. After making minor adjustments, the final version was prepared for use in the clinical trial.

In the second phase of the study (clinical intervention), patients with type 2 diabetes who had visited the diabetes clinic at Sadeghieh Tahereh Hospital in Isfahan were included in the study. Given the estimated 30% prevalence of diabetic peripheral neuropathy DPN in the diabetic population [24], and considering a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence level, the required sample size for initial screening was estimated to be approximately 280 participants.

After initial screening using the michigan neuropathy screening instrument (MNSI) and applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 96 eligible patients were selected. These individuals were randomly assigned into three groups of 32 participants: the in-person intervention group, the virtual intervention group (using the fall-prevention software developed in the study), and the control group.

Participant allocation to groups was performed by an independent researcher using the Minimization algorithm [25] to maintain balance between the groups in terms of two key variables: “duration of diabetes” and “severity of DPN.” This algorithm is an adaptive randomization method designed to minimize differences between groups concerning intervening variables (in this study: duration of diabetes and severity of DPN) (Equation 1).

To maintain single-blind assessment, evaluators and statistical analysts were unaware of the group assignments of participants.

Inclusion criteria for the study

1. Age 60 years and older: Given that type 2 diabetes typically begins in the fourth or fifth decade of life and diabetic neuropathy often occurs several years after the onset of the disease, this age range was chosen to focus on the target population with a higher likelihood of developing diabetic peripheral neuropathy [26];

2. Confirmed diagnosis of type 2 diabetes and an active medical record at Sadeghieh Tahereh Hospital in Isfahan: Participants must have visited the diabetes clinic of Sadeghieh Tahereh Hospital at least once in the past six months, with diagnostic and treatment-related information available in the hospital’s electronic health records system. This criterion was applied to ensure diagnostic accuracy, treatment follow-up, and access to valid clinical data for the initial assessment of participants;

3. Presence of signs of diabetic peripheral neuropathy as assessed by the MNSI, with a score ≥2 [27];

4. Ability to walk and maintain balance without the use of assistive devices, with a score greater than 20 on the BBS (BBS) [28];

5. Access to a smartphone for participants in the virtual intervention group;

6. Active participation in at least 90% of the sessions and exercises in the intervention groups;

7. Relatively controlled diabetes, with HbA1c levels less than 8% and blood pressure less than 140/90 mmHg;

8. Ability to provide informed consent and cooperate throughout the study period.

Exclusion criteria

1. Active foot ulcers, lower extremity surgery, or arthroplasty; 2. Diagnosis of severe neurological or cognitive disorders; 3. Receiving concurrent physical therapy or occupational therapy services similar to the intervention; 4. Occurrence of vascular complications or advanced retinopathy.

Inability or unwillingness to continue participation after three follow-up attempts.

Intervention groups

In-person intervention group

Participants in this group performed fall-prevention exercises twice a week (each session lasting 40 minutes with a 10-minute break) in person under the direct supervision of an occupational therapist at the clinic.

Virtual intervention group

After an in-person training session, participants in this group performed exercises at home using the developed software. This Android-based software was installed on the participants’ mobile phones, providing features such as video review, progress tracking, automatic reminders, and the ability to send messages to the therapist. No special equipment was required for home-based exercises, and if participants did not log into the software for more than five days, a reminder SMS was sent, and the researcher followed up.

Control group

The control group received only usual diabetes care including pharmacological treatment, dietary counseling, and lifestyle education, without any exercise intervention.

The fall-proof training followed a progressive structure over eight weeks, with intensity and complexity gradually increased [19, 23]. In weeks 1–2, exercises focused on center-of-mass control, seated weight-shifting, flexibility, and isometric ankle strengthening (12 repetitions, 4–5 sets, 6-second holds). In weeks 3–4, the program included sit-to-stand transfers, static single-leg stance, and dynamic gait tasks with object manipulation (15 repetitions, 8-second holds). In weeks 5–6, multisensory and coordination drills, balance perturbations, and gait pattern enhancement were added (20 repetitions, 10-second holds). In weeks 7–8, participants progressed to advanced postural strategy training, stretching, one-leg transfers with object control, and further progression of gait and balance tasks (25 repetitions, 12-second holds) [19, 23].

Outcomes were assessed at baseline, immediately post-intervention (week 8), and at two and three months after intervention by a trained occupational therapist blinded to group allocation.

Severity of DPN

In this study, the severity of DPN was assessed using the MNSI questionnaire. This tool consists of 15 questions regarding sensory symptoms and foot function. In this questionnaire, a “yes” answer to questions 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, and 15, and a “no” answer to questions 7 and 13, each receive a score of 1. Question 4 relates to circulatory deficiency, and question 10 pertains to the internal validity of the questionnaire (a “lie detection” control question), which are not included in the final score calculation. Therefore, the total score ranges from 0 to 13, with higher scores indicating greater severity of diabetic neuropathy [29].

Tactile sensation

Tactile sensation was assessed using the Semmes-Weinstein 10-gram monofilament on three key areas of the foot (third metatarsal, fifth metatarsal, and hallux) [29, 30].

Vibration sensation

Vibration sensation was assessed using a 128 Hz tuning fork placed on the distal phalanx of the hallux. The time (in seconds) from the start of the vibration until the patient could no longer feel the vibration was recorded [31].

Functional balance

Functional balance was assessed using the Berg balance scale (BBS). This scale consists of 14 items (common activities of daily living), and each item is rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 0 to 4, based on the quality or time spent completing the task. A score of 0 indicates the need for maximum assistance, and a score of 4 indicates the individual’s independence in performing the task. The maximum possible score is 56, which is derived from the sum of scores from various sections of the test. A score between 41 and 56 indicates high balance, meaning a low risk of losing balance and falling. A score between 21 and 40 indicates moderate balance, with a moderate risk of falling, and a score between 0 and 20 indicates low balance, with a high risk of falling. The reliability of each section of the BBS was reported to be 0.98, the reliability of each individual item was 0.99, and the internal consistency was 0.96 [32].

Data distribution was examined with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk tests. Between-group comparisons were performed using the Kruskal–Walli’s test, within-group changes over time with the Friedman test, and pairwise group comparisons with the Mann–Whitney U test adjusted with Bonferroni correction. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

In this single-blind clinical trial, 96 eligible patients were randomly divided into three groups of 32 participants each: In-person intervention, virtual intervention (using the software), and control. The three groups were comparable in terms of baseline variables, including average age (66.93, 67.53, and 67.96 years, respectively; P=0.848), body mass index (24.55, 25.22, and 24.86, respectively; P=0.772), and duration of diabetes (years) (P=0.563).

Additionally, the three groups were similar in terms of HbA1c levels (6.83, 6.70, and 6.93%, respectively; P=0.271), fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) (P=0.938), blood pressure (mmHg) (P=0.703), and the severity of neuropathy as assessed by the MNSI (8.81, 8.28, 8.34, respectively; P=0.649), based on the information in their medical records and clinical examination.

Vibration sensation

Based on the Kruskal-Wali’s test, there was no significant difference among the three groups in the pretest (P=0.750). After the intervention, both intervention groups (in-person and digital) showed a significant improvement in vibration sensation (P≤0.002), while the control group showed a significant decline (P=0.006). In comparing the groups, the digital intervention led to an increase of 0.359 units and the in-person intervention led to an increase of 0.021 units in vibration sensation. Although the difference between the two intervention groups was not statistically significant (P=0.114), the digital group showed the greatest improvement, and this improvement remained stable up to 3 months after the intervention (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Based on repeated measures analysis and Bonferroni test, results are shown in Figure 1. Effectiveness of Intervention on Light Touch Sensation

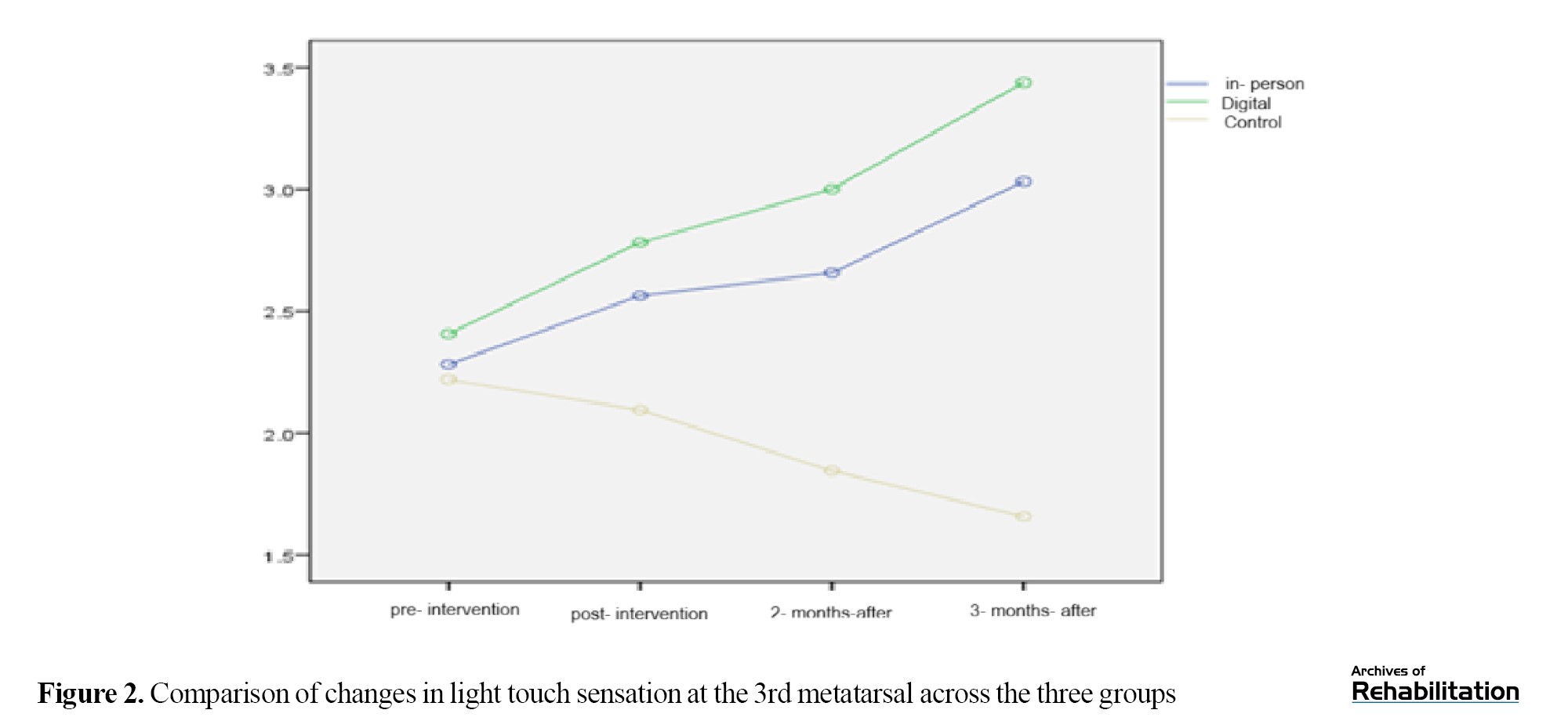

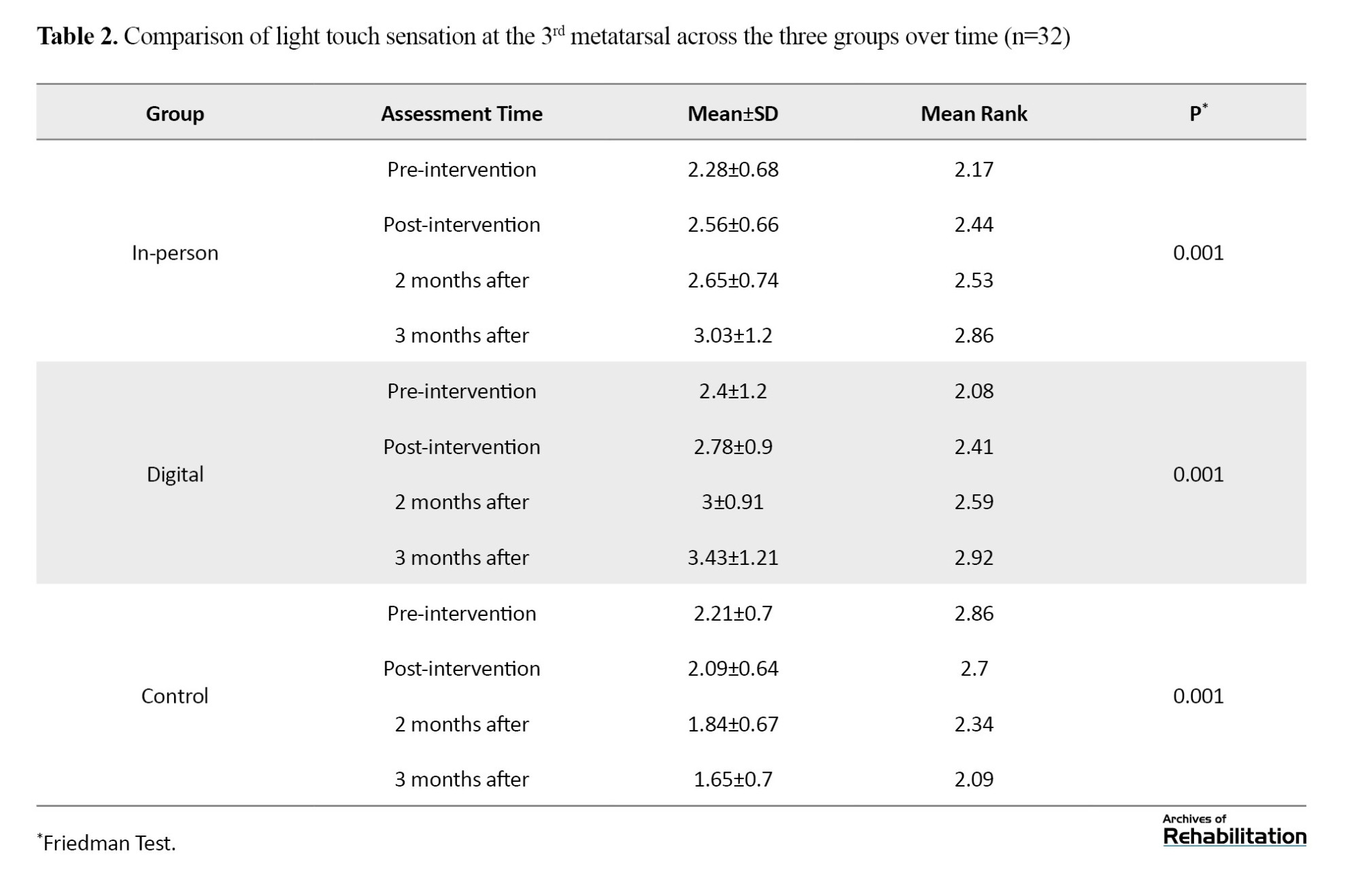

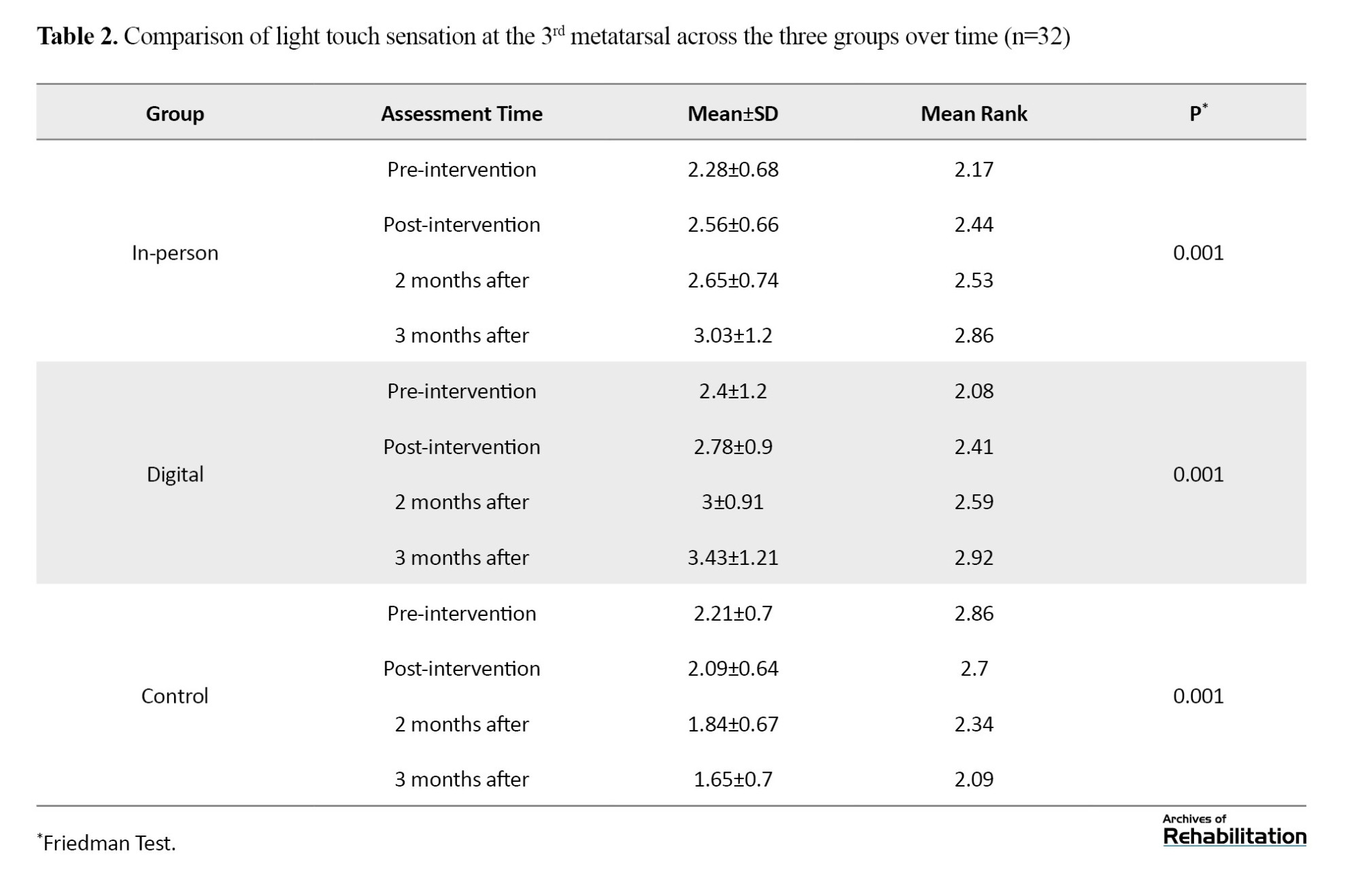

Light touch sensation at the 3rd metatarsal

Based on the Kruskal-Wali’s test, there was no significant difference among the groups in the pretest (p = 0.539). After the intervention, the digital group showed an improvement of 0.953 units and the in-person group showed an improvement of 0.679 units (P<0.001). The difference between the two intervention groups was not significant (p = 0.210), but both were significantly better than the control group (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Light touch sensation at the 3rd metatarsal

Based on the Kruskal-Wali’s test, there was no significant difference among the groups in the pretest (p = 0.539). After the intervention, the digital group showed an improvement of 0.953 units and the in-person group showed an improvement of 0.679 units (P<0.001). The difference between the two intervention groups was not significant (p = 0.210), but both were significantly better than the control group (Table 2 and Figure 2).

Based on repeated measures analysis and Bonferroni test, results are shown in Figure 2.

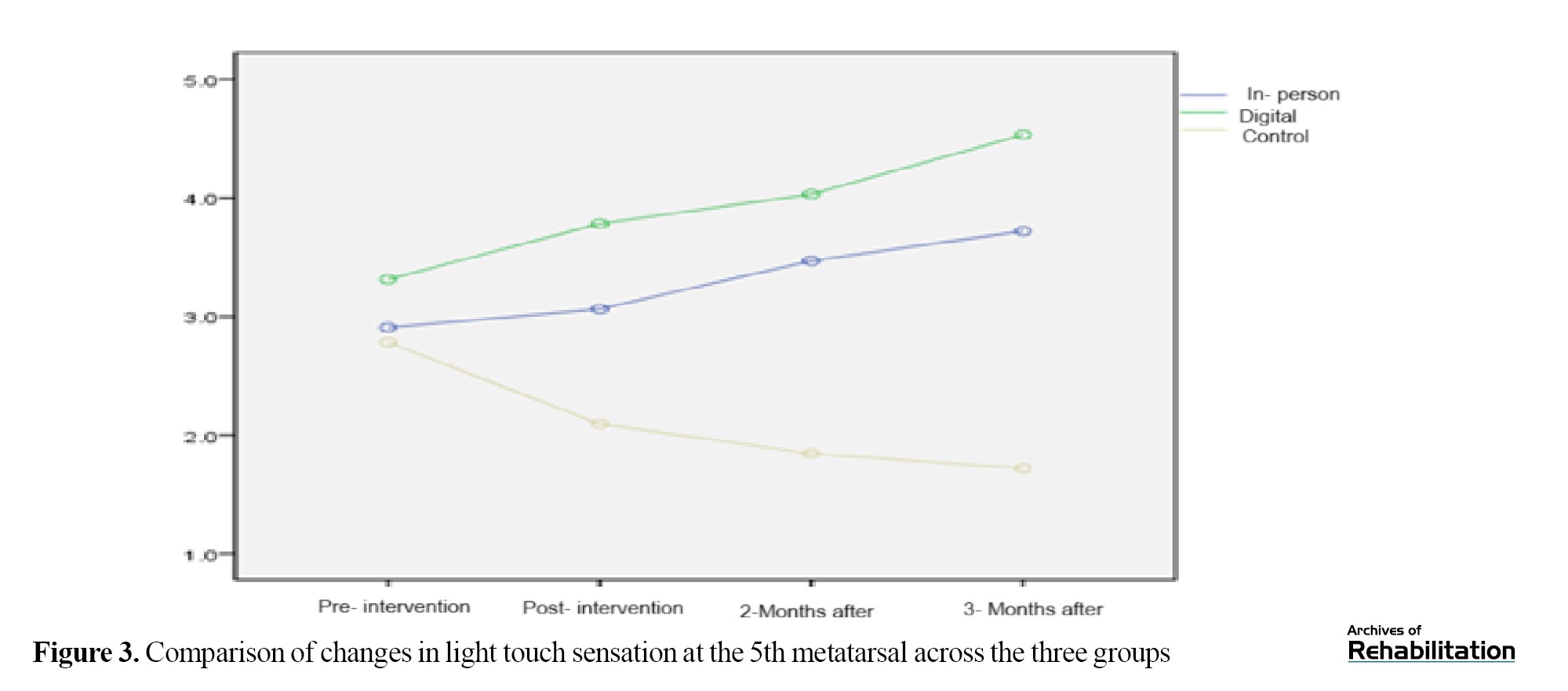

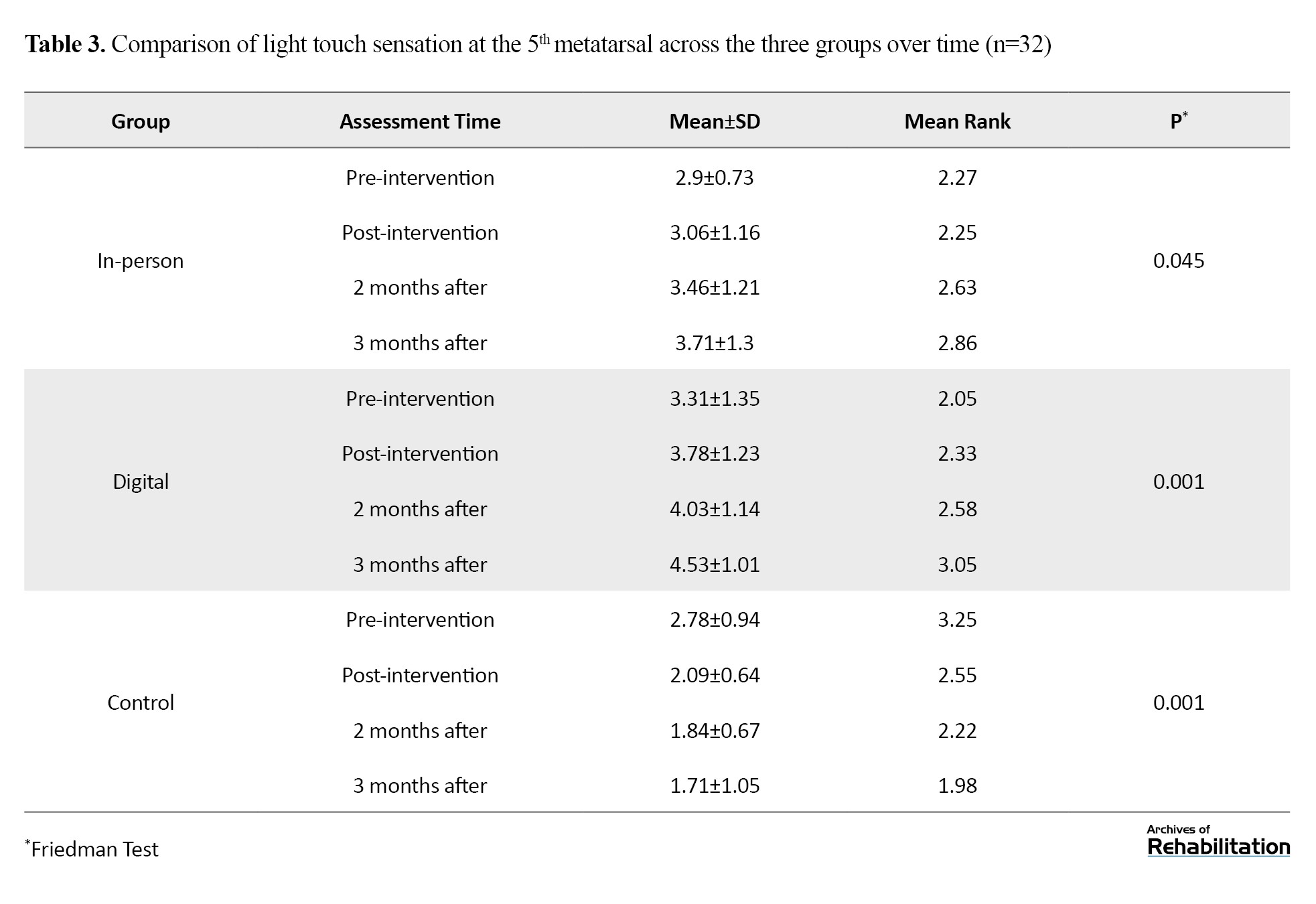

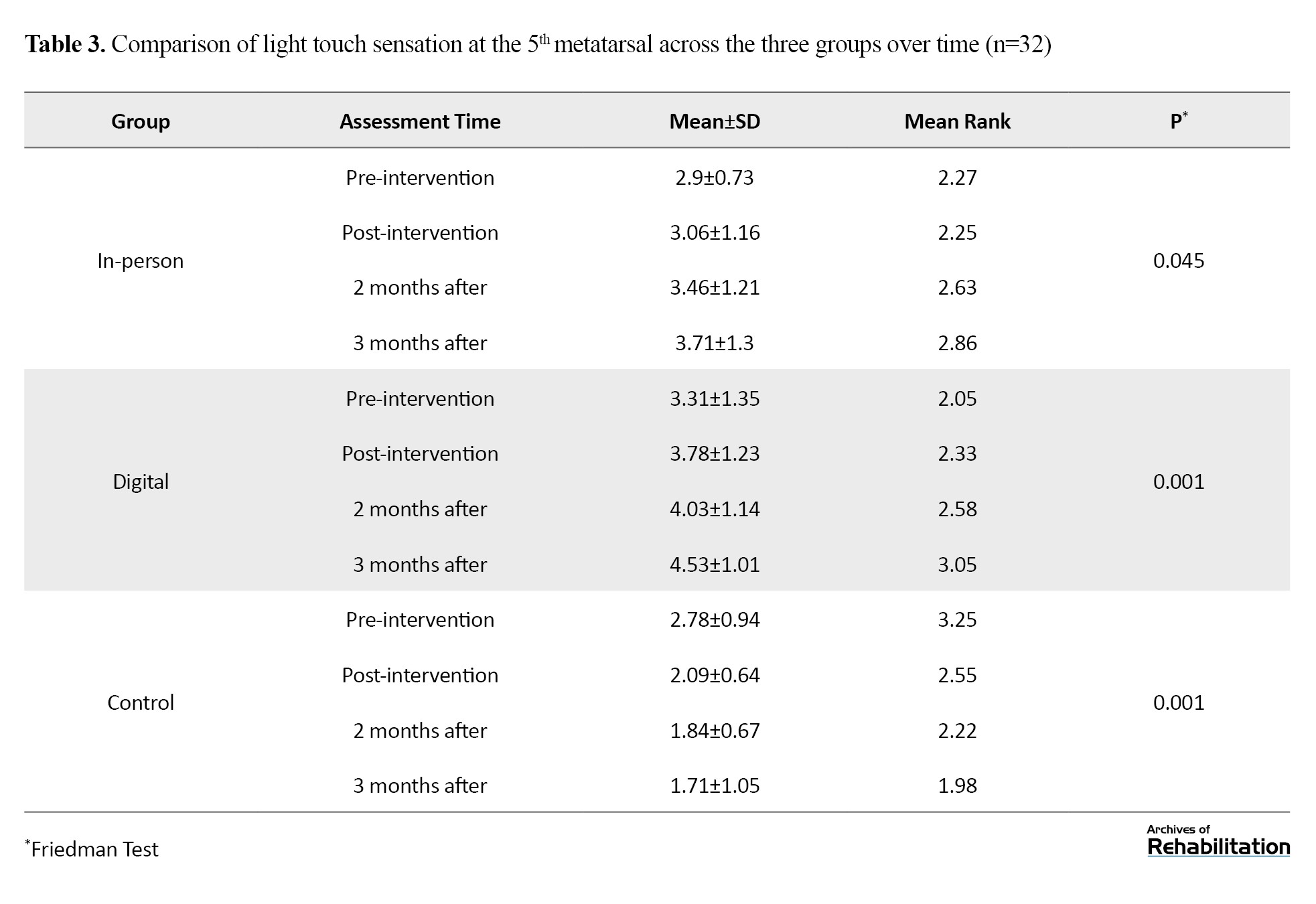

Light touch sensation at the 5th metatarsal

Based on the Kruskal-Walli’s test, this region—which plays a key role in balance and walking—showed the greatest improvement. There was no difference among groups in the pretest (P=0.109). After the intervention, the digital group improved by 1.804 units and the in-person group improved by 1.179 units (P<0.001). The difference between the two intervention groups was significant (P=0.001), with the digital group performing better. This improvement remained stable up to 3 months after the intervention (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Light touch sensation at the 5th metatarsal

Based on the Kruskal-Walli’s test, this region—which plays a key role in balance and walking—showed the greatest improvement. There was no difference among groups in the pretest (P=0.109). After the intervention, the digital group improved by 1.804 units and the in-person group improved by 1.179 units (P<0.001). The difference between the two intervention groups was significant (P=0.001), with the digital group performing better. This improvement remained stable up to 3 months after the intervention (Table 3 and Figure 3).

Based on repeated measures analysis and Bonferroni test, results are shown in Figure 3.

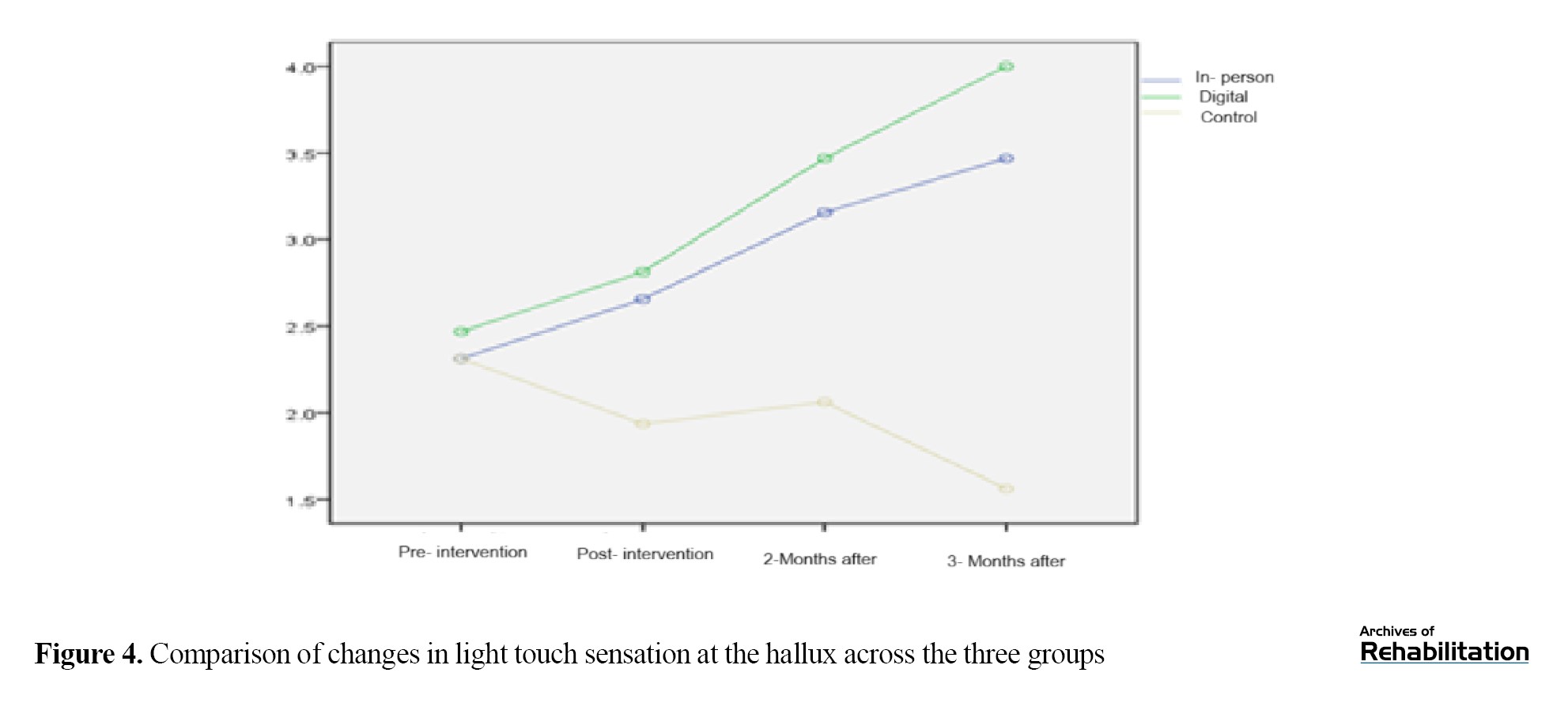

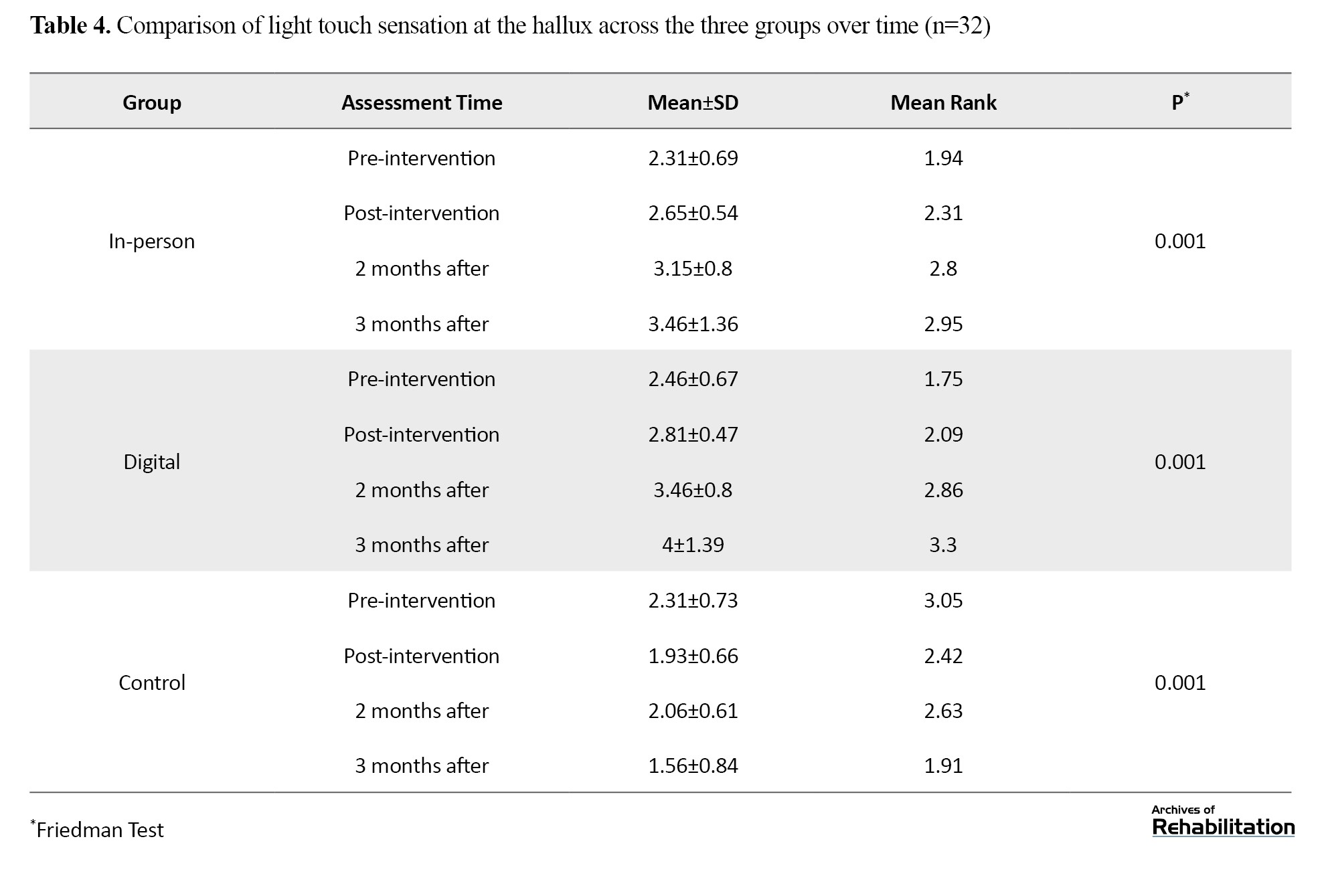

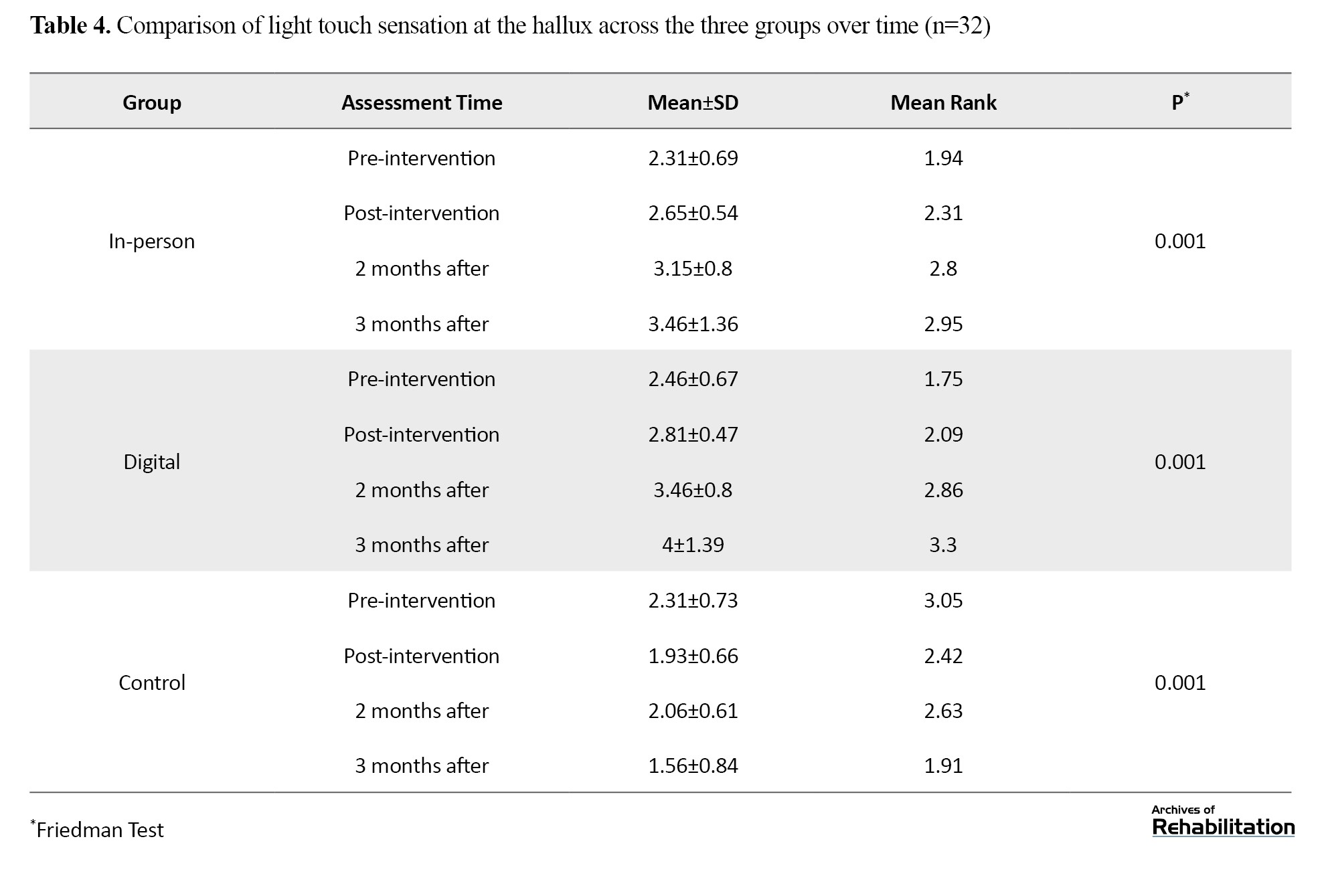

Light touch sensation at the hallux

Based on the Kruskal-Wali’s test, there was no significant difference in the pretest (P=0.591). After the intervention, the digital group showed an improvement of 1.218 units and the in-person group showed an improvement of 0.929 units (P<0.001). The difference between the two intervention groups was not significant (P=0.112), but both performed significantly better than the control group. The improvement in the digital group remained stable up to 3 months after the intervention (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Light touch sensation at the hallux

Based on the Kruskal-Wali’s test, there was no significant difference in the pretest (P=0.591). After the intervention, the digital group showed an improvement of 1.218 units and the in-person group showed an improvement of 0.929 units (P<0.001). The difference between the two intervention groups was not significant (P=0.112), but both performed significantly better than the control group. The improvement in the digital group remained stable up to 3 months after the intervention (Table 4 and Figure 4).

Based on repeated measures analysis and Bonferroni test, results are shown in Figure 4.

Discussion

The findings of this study revealed that the implementation of the “Fall-Proof” rehabilitation program, both in-person and virtually, had a significant positive effect on the improvement of sensory performance, including light touch and vibration sense, in patients with diabetic neuropathy, without causing serious side effects. Prior to the intervention, all patients experienced sensory impairments, but after 8 weeks, a remarkable improvement was observed in the intervention groups, particularly in the fifth metatarsal and hallux areas, which play a key role in balance control and fall prevention. These changes were more prominent in the virtual group than in the in-person group, and remained stable for up to three months after the intervention ended. In contrast, the control group showed not only no improvement but also a decline in sensory performance.

The study’s findings indicated that the “Fall-Proof” rehabilitation program had a significant positive effect on sensory performance in both in-person and virtual formats. Mechanistically, the improvement in sensory performance could be related to neural plasticity and enhanced synaptic connections in sensory pathways. The repeated stimulation of the soles during exercises activated mechanoreceptors and transmitted more precise information to the central nervous system. This process led to improved tactile and vibratory perception, ultimately enhancing the accuracy of postural responses [33].

Furthermore, the improvement in the virtual group was not only greater in effect size but also persisted for three months after the intervention ended. This remarkable advantage, despite the approximate similarity in duration and number of training sessions between the two groups, could be attributed to the inherent features of the digital environment and the interactive design of the software. The software used functioned beyond a video playback platform, providing real-time feedback, automatic session reminders, and recording individual progress, thus creating conditions for sustainable sensory-motor learning. Studies have shown that targeted and repetitive sensory stimulation, even with equal exercise volume, will be more effective when combined with behavioral reinforcement and intrinsic motivation [34, 35]. In the in-person group, although the sessions were under direct supervision, there was no mechanism to encourage home practice or behavior monitoring between sessions. In contrast, the software continuously engaged the user in the rehabilitation process.

Moreover, the familiar home environment in the virtual group may have helped reduce cognitive and physiological stress. Evidence shows that clinical environments or the presence of a therapist can increase anxiety and decrease sensory focus in some elderly individuals, especially those with chronic diseases [33]. In contrast, performing exercises in a calm and personal environment allows for deeper processing of sensory feedback, thus facilitating neuroplasticity in sensory-environmental and cortical pathways [36].

Additionally, the stepwise and gradual design of the exercises in the software, along with the option to review the videos unlimited times, allowed participants to personalize their learning speed. This feature, particularly in the elderly population with high variability in cognitive and sensory performance, could play a key role in stabilizing learning [34].

In contrast, the control group not only showed no improvement but also experienced a significant decline in sensory performance, which aligns with the natural progression of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the absence of intervention.

These findings are consistent with several studies. For example, Babb et al. [37] demonstrated that foot muscle strengthening exercises combined with sensory stimulation improved touch sensitivity and balance in diabetic patients. Similarly, Atre et al. [38] reported that functional exercises and sensory training improved vibration sense and motor safety in patients. Khurshid et al. [34], also confirmed the positive effect of combined exercises on touch sensitivity and balance in diabetic patients. Feng et al. [35] showed that a smart rehabilitation program improved vibration sense and movement confidence in neuropathic patients. These pieces of evidence reinforce the findings of the present study and emphasize the role of targeted foot stimulation in improving sensory performance.

However, the results of some studies were not aligned with our findings. For instance, Eddo et al. [39] in a large clinical trial showed that the implementation of a combined exercise program, including aerobic and resistance exercises, improved balance and walking performance but did not result in any significant changes in touch sensitivity or vibration threshold. Similarly, Calagan et al. [40] reported that balance and strengthening interventions reduced the fall risk but showed no improvement in proprioception or tactile sense. Margestren et al. [41] also found that even after 6 months of structured rehabilitation exercises, there were no significant changes in neurophysiological parameters or touch sensitivity in patients with severe neuropathy.

The differences between the results of the present study and the studies that did not align with our findings may be due to several factors.

1. First, the severity of the disease and the stage of neuropathy in the populations studied varied. In the present study, participants had mild to moderate neuropathy, whereas studies such as Margestren et al. [41] examined patients with advanced neuropathy and severe nerve damage (confirmed by neurophysiological criteria) and reported that even after 6 months of structured exercises, no significant improvement in touch sensitivity or vibration threshold was observed.

2. Second, the type of intervention and focus of the programs is a determining factor. Some studies, such as Eddo et al. [39], primarily focused on aerobic exercises and lifestyle changes, and although they improved balance and motor performance, they did not have a significant impact on touch sensitivity or vibration perception. Also, Calagan et al. [40] in a systematic review showed that interventions focused solely on glucose control or general exercises, without targeted sensory stimulation, cannot restore peripheral sensory function. In contrast, the present study, by combining balance, strengthening exercises, and targeted sensory stimulation of the soles (particularly in the fifth metatarsal and hallux areas), created conditions to induce sensory neuroplasticity.

3. Third, the duration of the intervention and follow-up also matters. Studies with short-term durations (e.g. 6 weeks) may not provide enough time to induce sustained neural changes [33]. In contrast, the present study, by combining balance, strengthening exercises, and targeted sensory stimulation, along with a three-month follow-up, provided optimal conditions for improving and stabilizing changes.

It is recommended that future studies examine the long-term sustainability of the effects of these exercises. Physiological analyses to identify the mechanisms of sensory improvement are also necessary. Additionally, examining the effects of these exercises on other functional dimensions such as balance, gait, and quality of life and comparing them with other exercise methods is suggested. Evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions in other high-risk populations and, ultimately, studying the relationship between improved sensory performance and reduced fear of falling and enhanced balance can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic effects.

Among the limitations of this study is the impossibility of fully blinding participants to the type of intervention; although the study was designed as a single-blind study, participants were aware of the intervention type (in-person or virtual) due to the nature of the exercises, which may have influenced perceived outcomes. Additionally, in the virtual intervention group, it was not possible to accurately monitor adherence to exercises and their actual duration, relying instead on self-reported data from participants. This may have led to bias in estimating the true effectiveness of the intervention, especially since initial results may have increased participants' intrinsic motivation to continue the exercises.

Conclusion

This study, with its dual design (face-to-face and virtual delivery) and specific focus on patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, provides new evidence in the field of digital rehabilitation. The findings indicate that virtual training is not only a viable alternative to conventional face-to-face methods but, in some key domains—including light touch and vibration sensation—may even achieve superior outcomes. Therefore, the Fall-Proof program, particularly in its digital format, represents an innovative, safe, and effective approach for improving sensory function and enhancing quality of life in patients with diabetes.

Sponsor:

The present study is part of the findings of the first author’s doctoral thesis in the Department of Occupational Therapy, Tehran University of Rehabilitation and Social Health Sciences. The University of Rehabilitation and Social Health Sciences has financially supported this article.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Rehabilitation and Social Health Sciences with the ethics code (IR.USWR.REC.1403.136) and this study has been registered with the Iranian Clinical Trial Registry with the code (IRCT20181117041673N2). In this study, written consent was obtained from all participants and the research process was fully explained.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Vice-Chancellor for Research of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Sahar Sadeghi Sedeh and Saeed FatorehChy; methodology: Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh and Nazila Akbarfahimi; validation: Seyed Ali Hosseini; resources, writing original draft, editing & review: Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh and Sahar Sadeghi Sedeh; supervision and project administration: Saeed FatorehChy and Enayat Bakhshi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no financial, scientific, or personal conflict of interest related to this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study as well as the staff of the Diabetes Clinic at Sedigheh Tahereh Hospital, Isfahan, for their valuable cooperation during the screening and intervention phases. The authors also acknowledge the Fall-Proof software development team, especially Mr. Mansour Patro.

Discussion

The findings of this study revealed that the implementation of the “Fall-Proof” rehabilitation program, both in-person and virtually, had a significant positive effect on the improvement of sensory performance, including light touch and vibration sense, in patients with diabetic neuropathy, without causing serious side effects. Prior to the intervention, all patients experienced sensory impairments, but after 8 weeks, a remarkable improvement was observed in the intervention groups, particularly in the fifth metatarsal and hallux areas, which play a key role in balance control and fall prevention. These changes were more prominent in the virtual group than in the in-person group, and remained stable for up to three months after the intervention ended. In contrast, the control group showed not only no improvement but also a decline in sensory performance.

The study’s findings indicated that the “Fall-Proof” rehabilitation program had a significant positive effect on sensory performance in both in-person and virtual formats. Mechanistically, the improvement in sensory performance could be related to neural plasticity and enhanced synaptic connections in sensory pathways. The repeated stimulation of the soles during exercises activated mechanoreceptors and transmitted more precise information to the central nervous system. This process led to improved tactile and vibratory perception, ultimately enhancing the accuracy of postural responses [33].

Furthermore, the improvement in the virtual group was not only greater in effect size but also persisted for three months after the intervention ended. This remarkable advantage, despite the approximate similarity in duration and number of training sessions between the two groups, could be attributed to the inherent features of the digital environment and the interactive design of the software. The software used functioned beyond a video playback platform, providing real-time feedback, automatic session reminders, and recording individual progress, thus creating conditions for sustainable sensory-motor learning. Studies have shown that targeted and repetitive sensory stimulation, even with equal exercise volume, will be more effective when combined with behavioral reinforcement and intrinsic motivation [34, 35]. In the in-person group, although the sessions were under direct supervision, there was no mechanism to encourage home practice or behavior monitoring between sessions. In contrast, the software continuously engaged the user in the rehabilitation process.

Moreover, the familiar home environment in the virtual group may have helped reduce cognitive and physiological stress. Evidence shows that clinical environments or the presence of a therapist can increase anxiety and decrease sensory focus in some elderly individuals, especially those with chronic diseases [33]. In contrast, performing exercises in a calm and personal environment allows for deeper processing of sensory feedback, thus facilitating neuroplasticity in sensory-environmental and cortical pathways [36].

Additionally, the stepwise and gradual design of the exercises in the software, along with the option to review the videos unlimited times, allowed participants to personalize their learning speed. This feature, particularly in the elderly population with high variability in cognitive and sensory performance, could play a key role in stabilizing learning [34].

In contrast, the control group not only showed no improvement but also experienced a significant decline in sensory performance, which aligns with the natural progression of diabetic peripheral neuropathy in the absence of intervention.

These findings are consistent with several studies. For example, Babb et al. [37] demonstrated that foot muscle strengthening exercises combined with sensory stimulation improved touch sensitivity and balance in diabetic patients. Similarly, Atre et al. [38] reported that functional exercises and sensory training improved vibration sense and motor safety in patients. Khurshid et al. [34], also confirmed the positive effect of combined exercises on touch sensitivity and balance in diabetic patients. Feng et al. [35] showed that a smart rehabilitation program improved vibration sense and movement confidence in neuropathic patients. These pieces of evidence reinforce the findings of the present study and emphasize the role of targeted foot stimulation in improving sensory performance.

However, the results of some studies were not aligned with our findings. For instance, Eddo et al. [39] in a large clinical trial showed that the implementation of a combined exercise program, including aerobic and resistance exercises, improved balance and walking performance but did not result in any significant changes in touch sensitivity or vibration threshold. Similarly, Calagan et al. [40] reported that balance and strengthening interventions reduced the fall risk but showed no improvement in proprioception or tactile sense. Margestren et al. [41] also found that even after 6 months of structured rehabilitation exercises, there were no significant changes in neurophysiological parameters or touch sensitivity in patients with severe neuropathy.

The differences between the results of the present study and the studies that did not align with our findings may be due to several factors.

1. First, the severity of the disease and the stage of neuropathy in the populations studied varied. In the present study, participants had mild to moderate neuropathy, whereas studies such as Margestren et al. [41] examined patients with advanced neuropathy and severe nerve damage (confirmed by neurophysiological criteria) and reported that even after 6 months of structured exercises, no significant improvement in touch sensitivity or vibration threshold was observed.

2. Second, the type of intervention and focus of the programs is a determining factor. Some studies, such as Eddo et al. [39], primarily focused on aerobic exercises and lifestyle changes, and although they improved balance and motor performance, they did not have a significant impact on touch sensitivity or vibration perception. Also, Calagan et al. [40] in a systematic review showed that interventions focused solely on glucose control or general exercises, without targeted sensory stimulation, cannot restore peripheral sensory function. In contrast, the present study, by combining balance, strengthening exercises, and targeted sensory stimulation of the soles (particularly in the fifth metatarsal and hallux areas), created conditions to induce sensory neuroplasticity.

3. Third, the duration of the intervention and follow-up also matters. Studies with short-term durations (e.g. 6 weeks) may not provide enough time to induce sustained neural changes [33]. In contrast, the present study, by combining balance, strengthening exercises, and targeted sensory stimulation, along with a three-month follow-up, provided optimal conditions for improving and stabilizing changes.

It is recommended that future studies examine the long-term sustainability of the effects of these exercises. Physiological analyses to identify the mechanisms of sensory improvement are also necessary. Additionally, examining the effects of these exercises on other functional dimensions such as balance, gait, and quality of life and comparing them with other exercise methods is suggested. Evaluating the effectiveness of these interventions in other high-risk populations and, ultimately, studying the relationship between improved sensory performance and reduced fear of falling and enhanced balance can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the therapeutic effects.

Among the limitations of this study is the impossibility of fully blinding participants to the type of intervention; although the study was designed as a single-blind study, participants were aware of the intervention type (in-person or virtual) due to the nature of the exercises, which may have influenced perceived outcomes. Additionally, in the virtual intervention group, it was not possible to accurately monitor adherence to exercises and their actual duration, relying instead on self-reported data from participants. This may have led to bias in estimating the true effectiveness of the intervention, especially since initial results may have increased participants' intrinsic motivation to continue the exercises.

Conclusion

This study, with its dual design (face-to-face and virtual delivery) and specific focus on patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, provides new evidence in the field of digital rehabilitation. The findings indicate that virtual training is not only a viable alternative to conventional face-to-face methods but, in some key domains—including light touch and vibration sensation—may even achieve superior outcomes. Therefore, the Fall-Proof program, particularly in its digital format, represents an innovative, safe, and effective approach for improving sensory function and enhancing quality of life in patients with diabetes.

Sponsor:

The present study is part of the findings of the first author’s doctoral thesis in the Department of Occupational Therapy, Tehran University of Rehabilitation and Social Health Sciences. The University of Rehabilitation and Social Health Sciences has financially supported this article.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Rehabilitation and Social Health Sciences with the ethics code (IR.USWR.REC.1403.136) and this study has been registered with the Iranian Clinical Trial Registry with the code (IRCT20181117041673N2). In this study, written consent was obtained from all participants and the research process was fully explained.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Vice-Chancellor for Research of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Sahar Sadeghi Sedeh and Saeed FatorehChy; methodology: Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh and Nazila Akbarfahimi; validation: Seyed Ali Hosseini; resources, writing original draft, editing & review: Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh and Sahar Sadeghi Sedeh; supervision and project administration: Saeed FatorehChy and Enayat Bakhshi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no financial, scientific, or personal conflict of interest related to this study.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study as well as the staff of the Diabetes Clinic at Sedigheh Tahereh Hospital, Isfahan, for their valuable cooperation during the screening and intervention phases. The authors also acknowledge the Fall-Proof software development team, especially Mr. Mansour Patro.

References

- Sun H, Saeedi P, Karuranga S, Pinkepank M, Ogurtsova K, Duncan BB, et al. IDF diabetes atlas: Global, regional and country-level diabetes prevalence estimates for 2021 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2022; 183:109119. [DOI:10.1016/j.diabres.2021.109119] [PMID]

- Khodakarami R, Abdi Z, Ahmadnezhad E, Sheidaei A, Asadi-Lari M. Prevalence, awareness, treatment and control of diabetes among Iranian population: results of four national cross-sectional STEPwise approach to surveillance surveys. BMC Public Health. 2022; 22(1):1216. [DOI:10.1186/s12889-022-13627-6] [PMID]

- Janjani P, Salehabadi Y, Motevaseli S, Heidari Moghadam R, Siabani S, Salehi N. Comparison of risk factors, prevalence, type of treatment, and mortality rate for myocardial infarction in diabetic and non-diabetic older adults: A cohort study. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2023; 18(2):268-83. [DOI:10.32598/sija.2022.3091.2]

- Rezaei M, FatorehChy S, Javaheri J. Investigation of dynamic balance and muscle strength of lower limbs in type 2 diabetic patients referred to Imam Reza Clinic (AS) in Arak City. Journal of Clinical Care and Skills. 2023; 4(4):175-82. [DOI:10.58209/jccs.4.4.175]

- Zhang P, Lu J, Jing Y, Tang S, Zhu D, Bi Y. Global epidemiology of diabetic foot ulceration: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Medicine. 2017; 49(2):106-16. [DOI:10.1080/07853890.2016.1231932] [PMID]

- Peters EJ, Armstrong DG, Lavery LA. Risk factors for recurrent diabetic foot ulcers: Site matters. Diabetes Care. 2007; 30(8):2077-9. [DOI:10.2337/dc07-0445] [PMID]

- Pound N, Chipchase S, Treece K, Game F, Jeffcoate W. Ulcer-free survival following management of foot ulcers in diabetes. Diabetic Medicine. 2005; 22(10):1306-9. [DOI:10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01640.x] [PMID]

- Van Netten J, Price PE, Lavery L, Monteiro-Soares M, Rasmussen A, Jubiz Y, et al. Prevention of foot ulcers in the at-risk patient with diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 2016; 32(Suppl 1):84-98. [DOI:10.1002/dmrr.2701] [PMID]

- Jeffcoate WJ, Vileikyte L, Boyko EJ, Armstrong DG, Boulton AJ. Current challenges and opportunities in the prevention and management of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Care. 2018; 41(4):645-52. [DOI:10.2337/dc17-1836] [PMID]

- Suryani M, Samekto W, Susanto H, Dwiantoro L. Effect of foot-ankle flexibility and resistance exercise in the secondary prevention of plantar foot diabetic ulcer. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2021; 35(9):107968. [DOI:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2021.107968] [PMID]

- Sartor CD, Hasue RH, Cacciari LP, Butugan MK, Watari R, Pássaro AC, et al. Effects of strengthening, stretching and functional training on foot function in patients with diabetic neuropathy: Results of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2014; 15:1-13. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2474-15-137] [PMID]

- Chang CF, Chang CC, Hwang SL, Chen MY. Effects of buerger exercise combined health-promoting program on peripheral neurovasculopathy among community residents at high risk for diabetic foot ulceration. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2015; 12(3):145-53. [DOI:10.1111/wvn.12091] [PMID]

- Kanchanasamut W, Pensri P. Effects of weight-bearing exercise on a mini-trampoline on foot mobility, plantar pressure and sensation of diabetic neuropathic feet; A preliminary study. Diabetic Foot & Ankle. 2017; 8(1):1287239. [DOI:10.1080/2000625X.2017.1287239] [PMID]

- Cerrahoglu L, Koşan U, Sirin TC, Ulusoy A. Range of motion and plantar pressure evaluation for the effects of self-care foot exercises on diabetic patients with and without neuropathy. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2016; 106(3):189-200. [DOI:10.7547/14-095] [PMID]

- Dijs HM, Roofthooft J, Driessens MF, De Bock P, Jacobs C, Van Acker KL. Effect of physical therapy on limited joint mobility in the diabetic foot. A pilot study. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2000; 90(3):126-32. [DOI:10.7547/87507315-90-3-126] [PMID]

- Allet L, Armand S, De Bie R, Golay A, Monnin D, Aminian K, et al. The gait and balance of patients with diabetes can be improved: A randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia. 2010; 53(3):458-66. [DOI:10.1007/s00125-009-1592-4] [PMID]

- Francia P, Anichini R, De Bellis A, Seghieri G, Lazzeri R, Paternostro F, et al. Diabetic foot prevention: The role of exercise therapy in the treatment of limited joint mobility, muscle weakness and reduced gait speed. Italian Journal of Anatomy and Embryology = Archivio Italiano di Anatomia ed Embriologia. 2015; 120(1):21-32. [PMID]

- Rose DJ. Reducing the risk of falls among older adults: The fallproof balance and mobility program. Current Sports Medicine Reports. 2011; 10(3):151-6. [DOI:10.1249/JSR.0b013e31821b1984] [PMID]

- Sheikhshoaei H, Bahiraei S, Safavi M. [Investigating the impact of fall-proof exercises on the balance system of elderly women with knee osteoarthritis(Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2025; 19(4):558-71. [DOI:10.32598/sija.2023.3721.1]

- Fathi S, Sadeghi Sede B, Safaein A, Fatorehchy S, Akbarfahimi N, Sadeghi Sede S. [Investigating the effect of fall- proof exercises on balance and fall prevention in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis (Persian)]. Salmand: Iranian Journal of Ageing 2026; 21(1):1. [Link]

- Khazanin H, Daneshmandi H, Fakoor Rashid H. Effect of selected fall-proof exercises on fear of falling and quality of life in the elderly. Iranian Journal of Ageing. 2022; 16(4):564-77. [DOI:10.32598/sija.2021.3152.1]

- Sharahi MY, Raeisi Z. Effects of otago and fit-and-fall proof home-based exercises on older adults’ balance, quality of life, and fear of falling: A randomized, single-blind clinical trial. Sport Sciences for Health. 2025; 21:1177–86. [DOI:10.1007/s11332-025-01357-2]

- Rose DJ. Fallproof!: A comprehensive balance and mobility training program. Champaign: Human Kinetics; 2010. [Link]

- Sun J, Wang Y, Zhang X, Zhu S, He H. Prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in patients with diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Primary Care Diabetes. 2020; 14(5):435-44. [DOI:10.1016/j.pcd.2019.12.005] [PMID]

- Pocock SJ, Simon R. Sequential treatment assignment with balancing for prognostic factors in the controlled clinical trial. Biometrics. 1975; 31(1):103-15. [DOI:10.2307/2529712] [PMID]

- Nanayakkara N, Ranasinha S, Gadowski A, Heritier S, Flack JR, Wischer N, et al. Age, age at diagnosis and diabetes duration are all associated with vascular complications in type 2 diabetes. Journal of Diabetes and its Complications. 2018; 32(3):279-90. [DOI:10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.11.009] [PMID]

- Moghtaderi A, Bakhshipour A, Rashidi H. Validation of Michigan neuropathy screening instrument for diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 2006; 108(5):477-81. [DOI:10.1016/j.clineuro.2005.08.003] [PMID]

- Sadeghi S, Nourozi A, Azadi H, Faraji F, Mardani M, Sadeghi B. Comparing vitamin b12 and nitrous oxide neurotoxicity in operating room staff and other hospital staff: A multicenter study. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2019; 29(173):134-9. [Link]

- Boulton AJ, Armstrong DG, Albert SF, Frykberg RG, Hellman R, Kirkman MS, et al. Comprehensive foot examination and risk assessment: a report of the task force of the foot care interest group of the American Diabetes Association, with endorsement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. Diabetes Care. 2008; 31(8):1679-85. [DOI:10.2337/dc08-9021] [PMID]

- Frykberg RG, Lavery LA, Pham H, Harvey C, Harkless L, Veves A. Role of neuropathy and high foot pressures in diabetic foot ulceration. Diabetes Care. 1998; 21(10):1714-9. [DOI:10.2337/diacare.21.10.1714] [PMID]

- Perkins BA, Olaleye D, Zinman B, Bril V. Simple screening tests for peripheral neuropathy in the diabetes clinic. Diabetes Care. 2001; 24(2):250-6. [DOI:10.2337/diacare.24.2.250] [PMID]

- Berg KO, Wood-Dauphinee SL, Williams JI, Maki B. Measuring balance in the elderly: Validation of an instrument. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 1992; 83(Suppl 2):S7-11. [PMID]

- Nogueira LRN, Nogueira CM, da Silva AE, Luvizutto GJ, de Sousa LAPS. Balance evaluation in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus with and without peripheral neuropathy. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2024; 40:534-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbmt.2024.05.010] [PMID]

- Khurshid S, Saeed A, Kashif M, Nasreen A, Riaz H. Effects of multisystem exercises on balance, postural stability, mobility, walking speed, and pain in patients with diabetic peripheral neuropathy: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Neuroscience. 2025; 26(1):16. [DOI:10.1186/s12868-024-00924-6] [PMID]

- Feng S, Tang M, Huang G, Wang J, He S, Liu D, et al. EMG biofeedback combined with rehabilitation training may be the best physical therapy for improving upper limb motor function and relieving pain in patients with the post-stroke shoulder-hand syndrome: A Bayesian network meta-analysis. Frontiers in Neurology. 2023; 13:1056156. [DOI:10.3389/fneur.2022.1056156] [PMID]

- Kosarian Z, Zakerkish M, Mehravar M, Shaterzadeh Yazdi M, Hesam S. Motor strategies used to restore balance in people with and without impaired sensory organization suffering from diabetic polyneuropathy. Jundishapur Scientific Medical Journal. 2022; 21(4):560-73. [DOI:10.32598/JSMJ.21.4.2844]

- Boob M, Phansopkar P. Effect of foot core exercises vs ankle proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation on pain, range of motion, and dynamic balance in individuals with plantar fasciitis: A comparative study. F1000Research. 2024; 12:765. [DOI:10.12688/f1000research.136828.1]

- Atre JJ, Ganvir SS. Effect of functional strength training versus proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation on balance and gait in patients with diabetic neuropathy. Indian Journal of Physical Therapy and Research. 2020; 2(1):47-54. [DOI:10.4103/ijptr.ijptr_76_19]

- Look AHEAD Research Group. Effects of a long-term lifestyle modification programme on peripheral neuropathy in overweight or obese adults with type 2 diabetes: The Look AHEAD study. Diabetologia. 2017; 60(6):980-8. [DOI:10.1007/s00125-017-4253-z] [PMID]

- Callaghan BC, Little AA, Feldman EL, Hughes RA. Enhanced glucose control for preventing and treating diabetic neuropathy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012(6):1. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD007543.pub2]

- Morgenstern J, Groener JB, Jende JME, Kurz FT, Strom A, Göpfert J, et al. Neuron-specific biomarkers predict hypo- and hyperalgesia in individuals with diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Diabetologia. 2021; 64(12):2843-55. [DOI:10.1007/s00125-021-05557-6] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 30/09/2025 | Accepted: 11/11/2025 | Published: 1/01/2026

Received: 30/09/2025 | Accepted: 11/11/2025 | Published: 1/01/2026

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |