Volume 26, Issue 3 (Autumn 2025)

jrehab 2025, 26(3): 422-445 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Ghovati F, Ashtari A, Soleimani F, Zarifian T, Vahedi M, Goshtai S M. An Investigation and Comparison of Early Communication Skills in Persian-speaking Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder Using Communication Skills Checklist (CSC). jrehab 2025; 26 (3) :422-445

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3632-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3632-en.html

Fateme Ghovati1

, Atieh Ashtari *2

, Atieh Ashtari *2

, Farin Soleimani3

, Farin Soleimani3

, Talieh Zarifian1

, Talieh Zarifian1

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Seyyede Masuomeh Goshtai5

, Seyyede Masuomeh Goshtai5

, Atieh Ashtari *2

, Atieh Ashtari *2

, Farin Soleimani3

, Farin Soleimani3

, Talieh Zarifian1

, Talieh Zarifian1

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Seyyede Masuomeh Goshtai5

, Seyyede Masuomeh Goshtai5

1- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,at.ashtari@uswr.ac.ir

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Health Education and Promotion, Deputy of Health, Iran university of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Health Education and Promotion, Deputy of Health, Iran university of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 2723 kb]

(331 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1356 Views)

Full-Text: (296 Views)

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by substantial deficits in communication skills and restricted/repetitive behavior patterns [1]. Early communicative skills emerge during the prelinguistic stage, typically at 9 months of age, when intentional communication begins. These skills encompass behaviors such as gesture use, eye contact, vocalizations, and single-word expression, serving functions like behavior regulation (requesting and rejecting), social interaction, and joint attention [2]. Additionally, key cognitive skills in the prelinguistic stage, such as play, imitation, and object permanence, develop during the initial stage of intentional communication (approximately 9–12 months). Research indicates that these skills are crucial for later language development in both typically developing (TD) children and those with developmental disorders [3, 4]. Children with ASD exhibit significant impairments in communicative skills, including limited or absent use of gestures, eye contact, varied vocalizations, and joint attention compared to TD peers [5–8]. Beyond communication, cognitive abilities are also affected; children with ASD often show deficits in various types of play, particularly pretend and symbolic play, and in imitation [9]. Studies suggest that impairments in early communication and cognitive skills during early childhood increase the risk of ASD development [7, 10]. Given the critical role and vulnerability of these skills in children with ASD, their assessment is essential for early identification of at-risk children and for establishing communication profiles to guide therapeutic interventions [11]. Theoretical frameworks, such as social interaction theory, and intervention models such as the social-pragmatic developmental approach and prelinguistic milieu teaching (PMT), emphasize the importance of assessing these skills in children with ASD, focusing on early detection and individualized treatment [12, 13].

Various methods, including parent–child interaction observations and parent-report checklists, have been used to study early communication in children with ASD and identify at-risk children. Parent-report tools have demonstrated high validity and reliability [14, 15]. Internationally, prominent parent-report tools include the communication and symbolic behavior scales – infant toddler checklist (CSBS-ITC) [16] and the MacArthur–Bates communicative development inventories–1 (CDI-1) [17]. However, the CSBS-ITC does not assess skills such as imitation, nonverbal comprehension, or phrase production, while the CDI-1 primarily focuses on receptive and expressive vocabulary [18, 19]. Numerous studies have examined early communication skills, such as joint attention, imitation, and vocalizations, and their predictive role in later language development using various tools [20–24]. For instance, Hamrick et al. used the autism diagnostic observation schedule–2 (ADOS-2) to evaluate nonverbal communication in children with ASD aged 18–70 months, aiming to improve screening accuracy and reduce diagnostic errors [20]. Maes et al. employed the CDI-1 to assess vocal output (vocalizations and early words) in children with ASD aged 3–5 years, without comparing them to TD peers [25]. Vennes c et al. conducted a longitudinal study using the CSBS DP-ITC and CDI-1 to identify early ASD markers in children aged 12–24 months later diagnosed at age four, comparing them to TD children, those with language impairment, and those with developmental delays; however, no within-group ASD comparisons or examinations of older age groups were performed [26].

In Iran, research on early communication skills has primarily focused on specific abilities, such as nonverbal communication or early vocabulary, in TD children, often to validate screening tools [27–31]. For example, Oryadi-Zanjani developed the children’s nonverbal communication scale (CNCS) for TD children aged 3–18 months but did not apply it to children with ASD [27]. Kazemi et al. examined the psychometric properties of the CDI-1 in TD children aged 8–16 months [32]. This tool has also been used to assess receptive and expressive vocabulary in Persian-speaking children with ASD, for example, in Teimouri et al.’s study on remote interventions [33]. Most Iranian studies on minimally verbal or nonverbal children with ASD emphasized intervention effects on early communicative skills or examined selected abilities [34, 35]. Dadgar et al. used the early social communication scales (ESCSs) to evaluate nonverbal communication in children with ASD aged 3–5 years and assess its relationship with imitation and motor skills [35]. Abdi et al. assessed pivotal response treatment effects in Iranian children with ASD aged 2–6 years using the Persian version of the autism treatment evaluation checklist, a diagnostic tool covering speech, language, communication, socialization, sensory awareness, cognition, and health [36].

A review of Iranian studies reveals that no studies have systematically investigated early communication skills using specialized instruments to compare them between ASD children and their TD peers. One available tool is the communication skills checklist (CSC), developed by Bayat et al. to screen early communication and related cognitive skills in Persian-speaking TD children aged 6–24 months. The CSC has strong psychometric properties and is completed by primary caregivers, typically mothers [37]. This study used the CSC to: (a) assess early communication skills in Persian-speaking minimally verbal or nonverbal children with ASD at the initial intentional communication stage aged 3–5 years, since formal ASD diagnoses in Iran typically occur after age three [38, 39], and expressive language often emerges during this period [25]; (b) compare these skills between age groups in both ASD and TD children; and (c) compare skills between ASD and TD children aged 9–12 months matched for communicative developmental level [40-43].

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a descriptive–analytical study with a cross-sectional design conducted in Tehran, Iran, during 2023–2024. Participants were 70 children with ASD aged 3-5 years and 132 TD children aged 9–12 months. The ASD group was subdivided into three age groups (3, 4, and 5 years), with at least 23 children per group. The TD group was divided into four age groups (9, 10, 11, and 12 months), with at least 25 children per group. The two groups were matched for the communicative developmental level. Inclusion criteria for both groups were being monolingual Persian speakers, residing in Tehran, and having mothers proficient in Persian speaking and writing. For the ASD group, additional inclusion criteria were chronological age 3–5 years; ASD diagnosis by a child psychiatrist based on the DSM-5 criteria, documented in medical records; absence of severe comorbid sensory, motor, metabolic, or genetic syndromes; having at least early intentional communication; and, for verbal children, a spontaneous vocabulary of at most 3–5 words using the CDI-1. For the TD group, additional inclusion criteria were chronological age 9–12 months, no parental developmental concerns, absence of genetic syndromes, physical impairments, or hearing loss, and no preterm birth history, based on medical records or using a researcher-designed checklist. The exclusion criterion for both groups was the incomplete return of questionnaires.

Children with ASD were recruited using a convenience sampling method from rehabilitation centers in Tehran. Eligibility was assessed using clinical records and CDI-1 results. If the criteria were met, informed consent was obtained from their mothers. For the TD group, recruitment was conducted using two approaches: In-person and online sampling (due to the onset of the respiratory disease season during data collection). In the in-person sampling method, health and vaccination centers affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, and Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences were first randomly selected. The research team then attended these centers, selected eligible boys and girls using a convenience sampling method. In the online sampling method, recruitment was also conducted using a convenience method following the distribution of an invitation poster on social media platforms such as Instagram. The poster provided information about the study objectives. Interested mothers contacted the research team, and the inclusion criteria were assessed through an online interview with the principal investigator.

Instruments

Data collection in the present study was conducted using three instruments: A demographic form, the CSC, and the CDI-1.

The CSC is a validated tool in Persian for screening communication skills in TD children aged 6–24 months, which is completed by parents or primary caregivers (mothers). It includes 36 items (33 on a three-point Likert scale, and 3 on a five-point scale) assessing prelinguistic domains: Communication (16 items, max score 32; gestures, eye contact, facial expressions, functions), expression (4 items, max score 12; word production, vocalizations, phrases), comprehension (7 items, max score 14; verbal/nonverbal), and play/imitation (9 items, max score 20; play types, imitation, object permanence). The total score ranges from 0 to 78. It has a Cronbach’s α of 0.95 and a test re-test reliability of 0.93 [37].

The CDI-1 is a parent-report tool assessing receptive/expressive vocabulary and gesture use in TD children aged 8–16 months, also applicable to older children with developmental disorders like ASD. The Persian version, validated by Kazemi et al., has a Cronbach’s α of 0.43–0.98 across subscales [32].

Data analysis

For performing data analysis, SPSS software, version 25 was used. Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic factors (age, gender, parents’ education/occupation). Mean±SD were used to describe the CSC domain scores. Data normality was confirmed. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc was used to compare the scores within ASD and TD groups. Independent t-test was used to compare the scores between the groups.

Results

Characteristics of participants

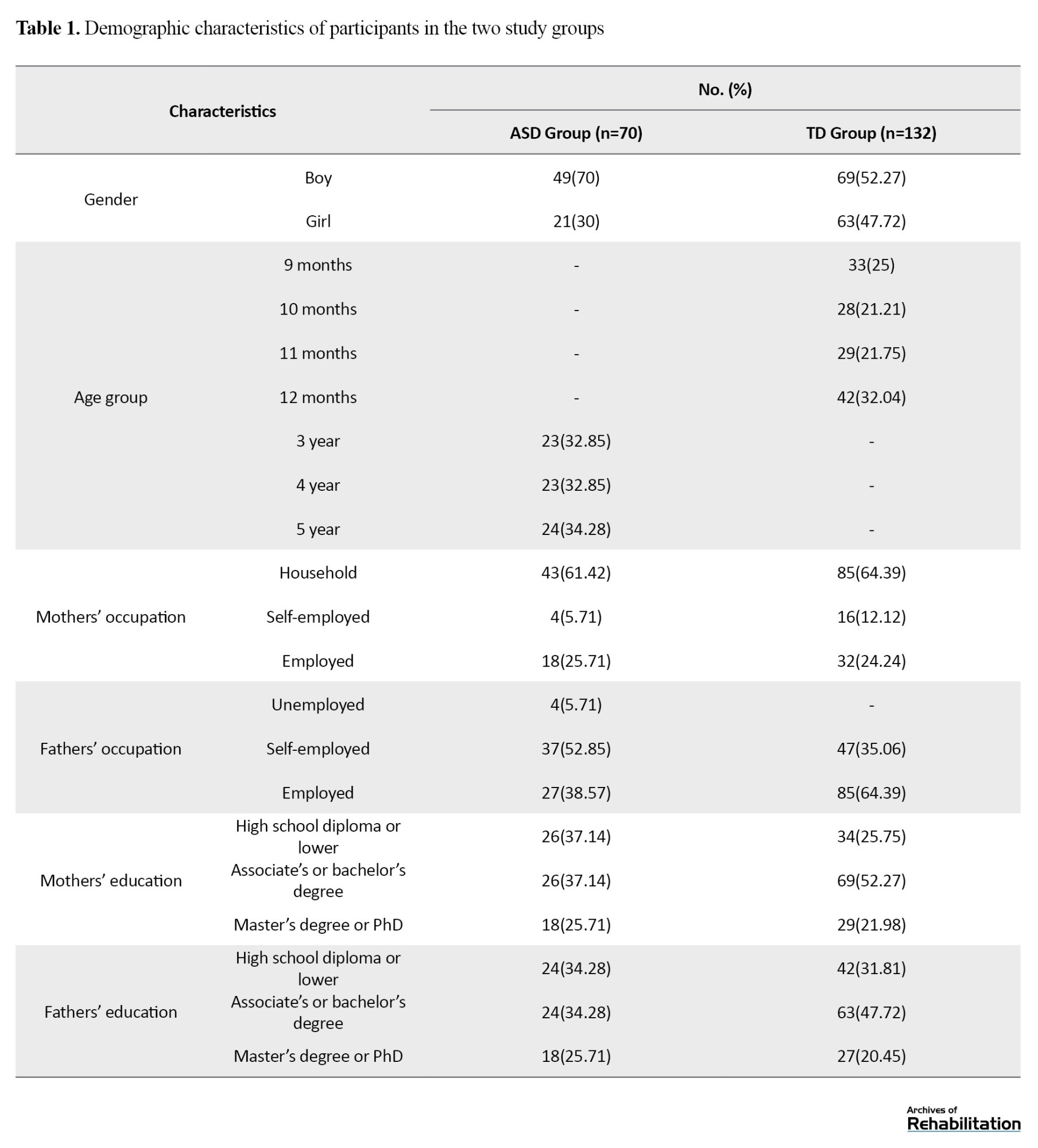

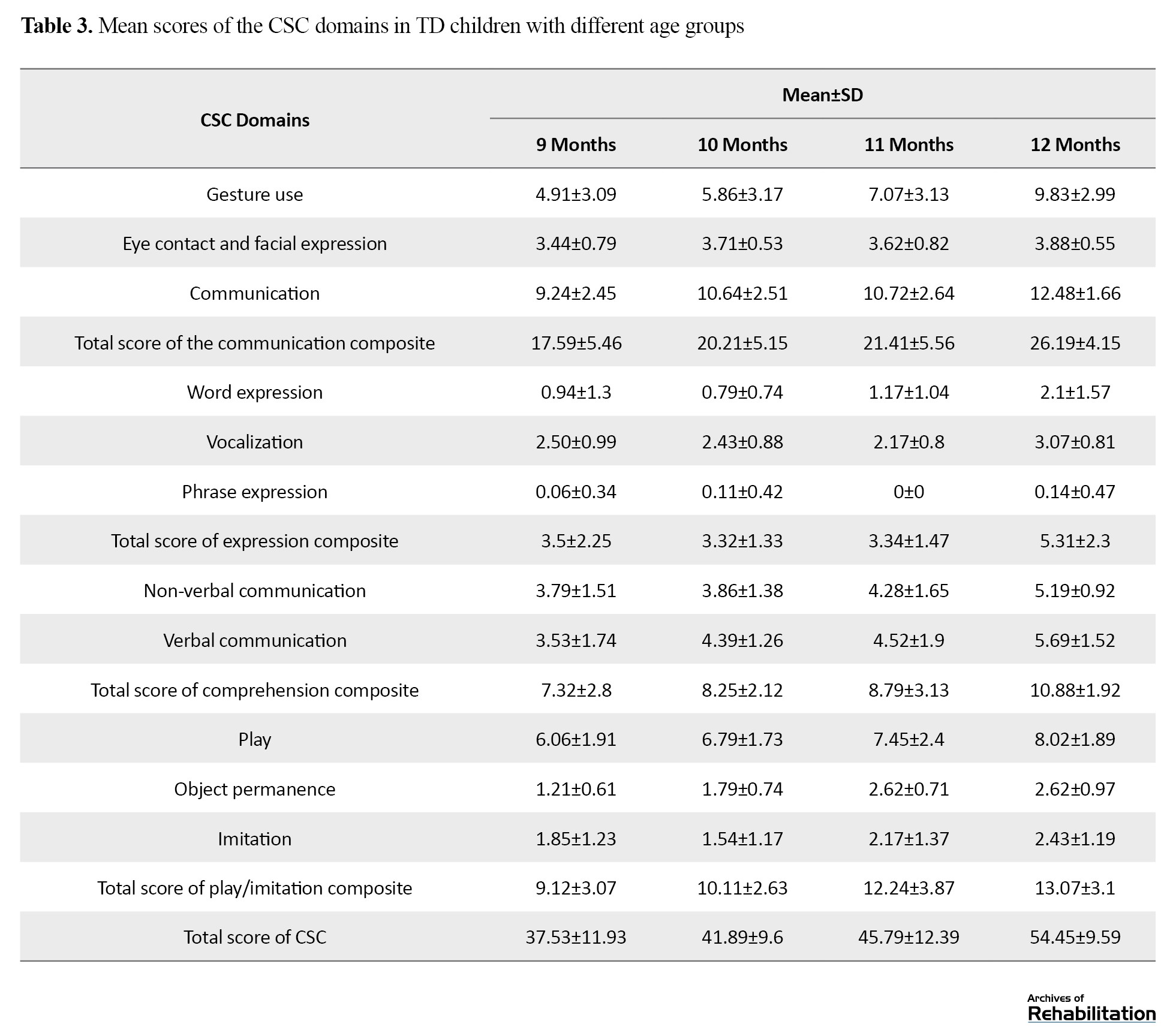

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants in the two groups.

It should be noted that some mothers of children with ASD, after participation in the study, were not willing to provide information about their own or their husbands’ employment and educational level for personal reasons.

Early communication skills in children with ASD and TD children

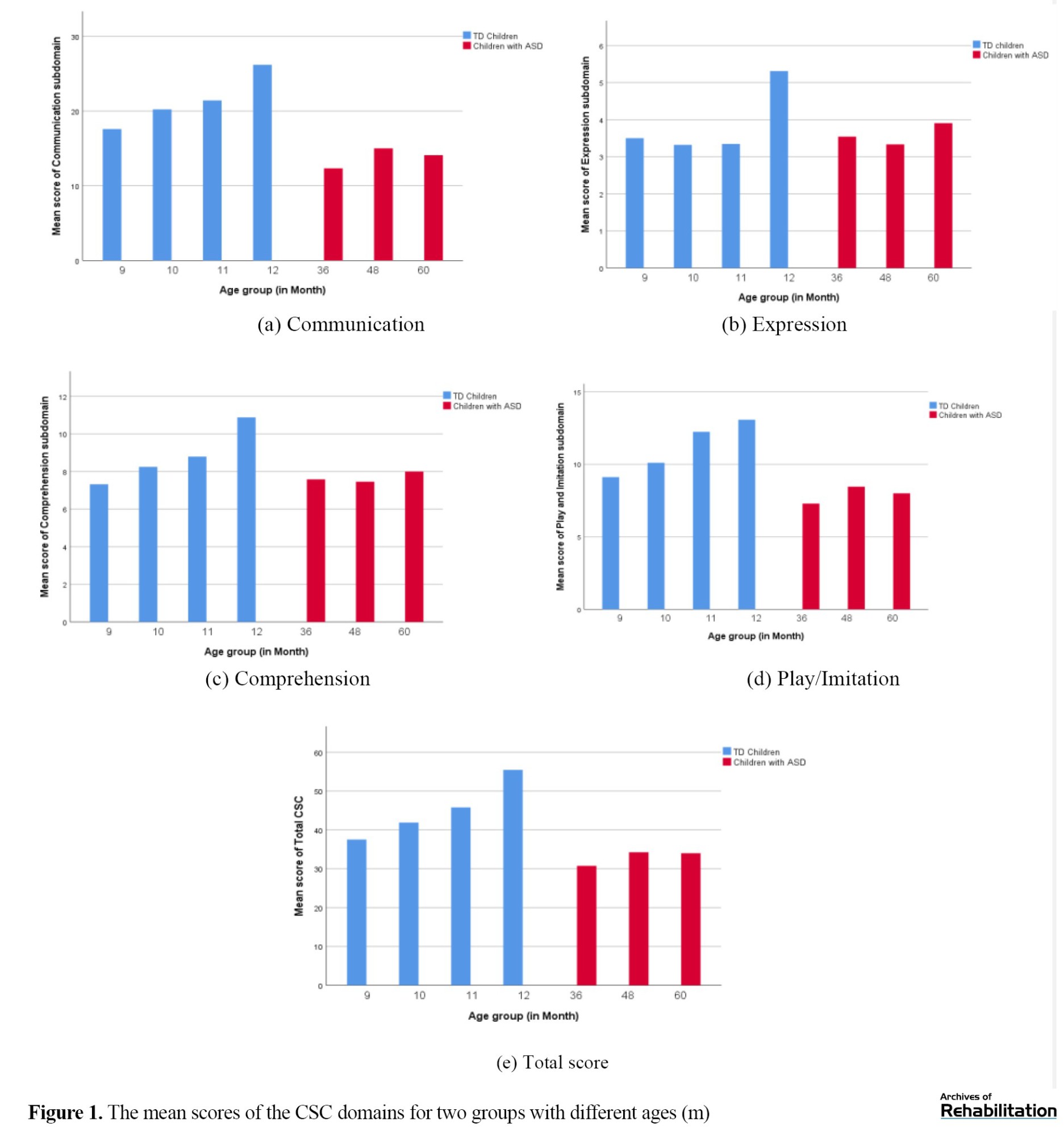

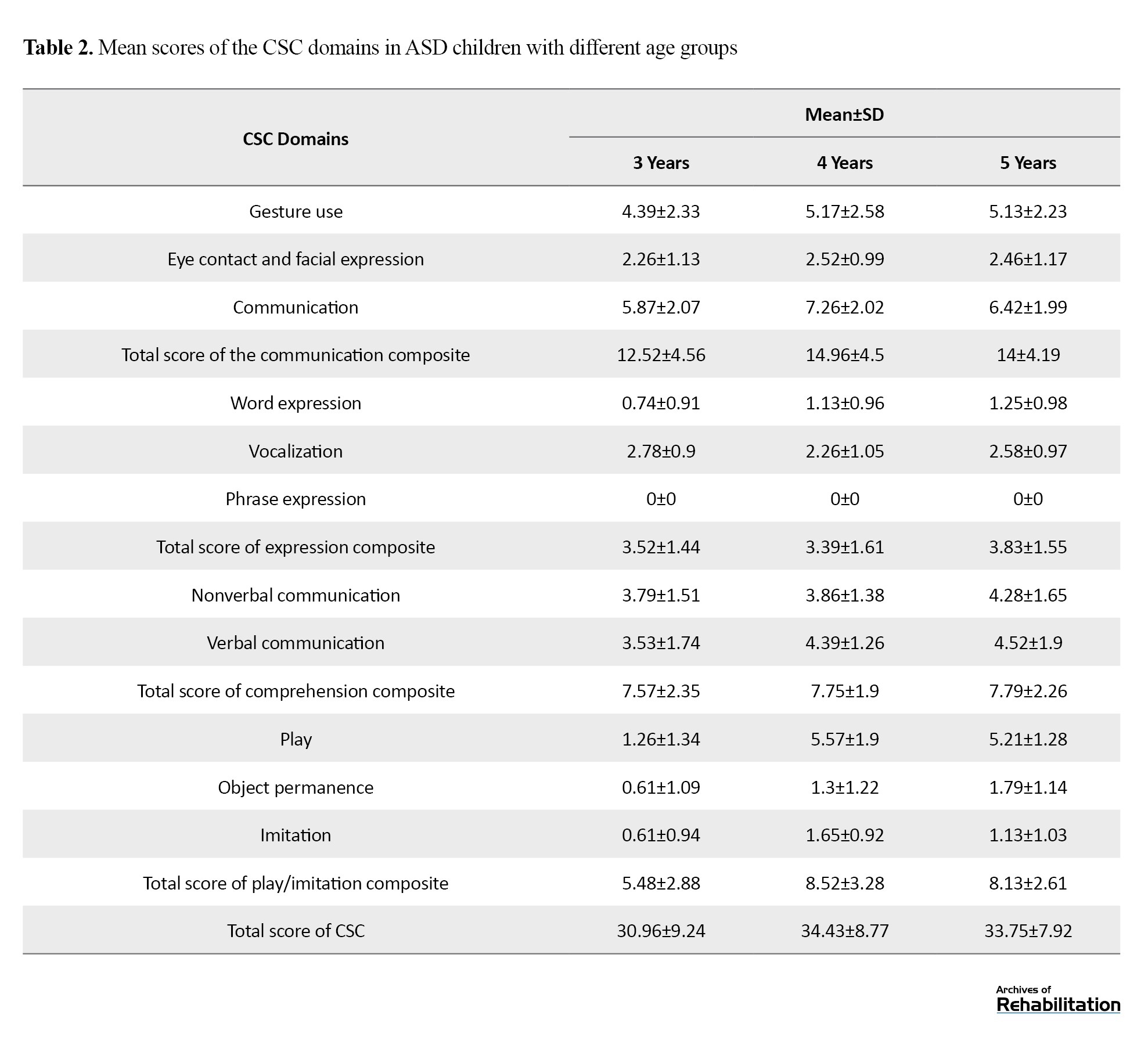

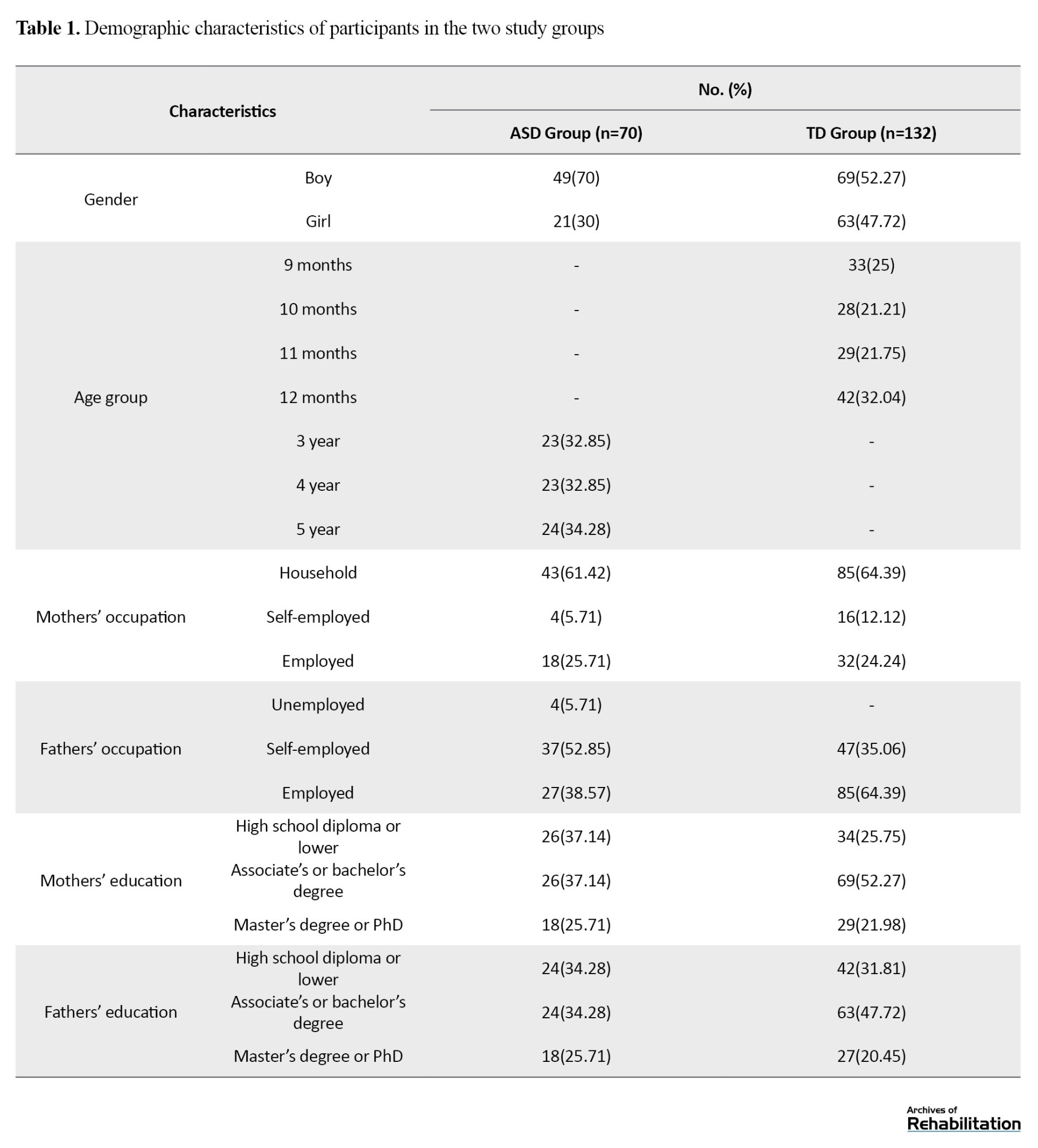

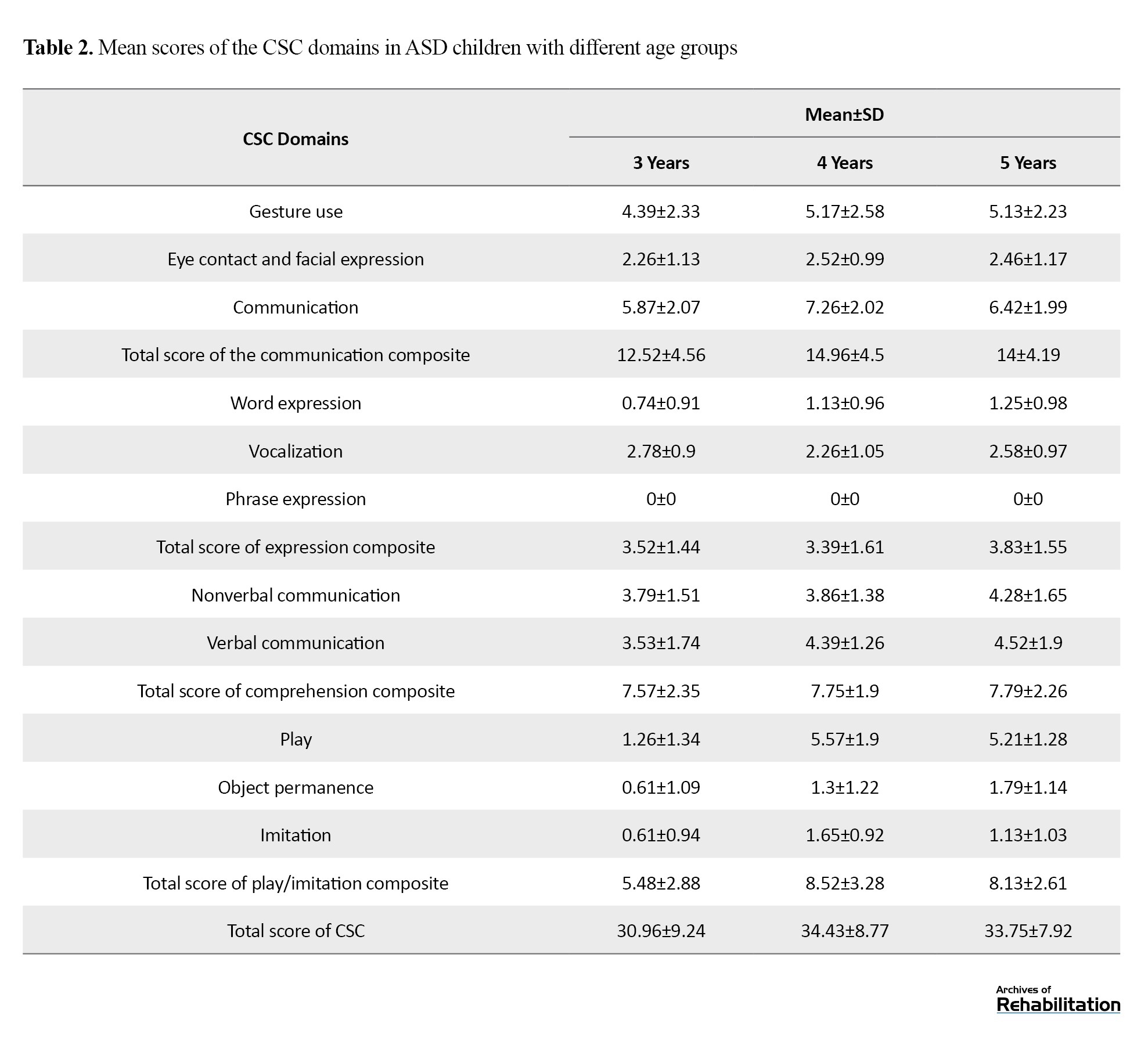

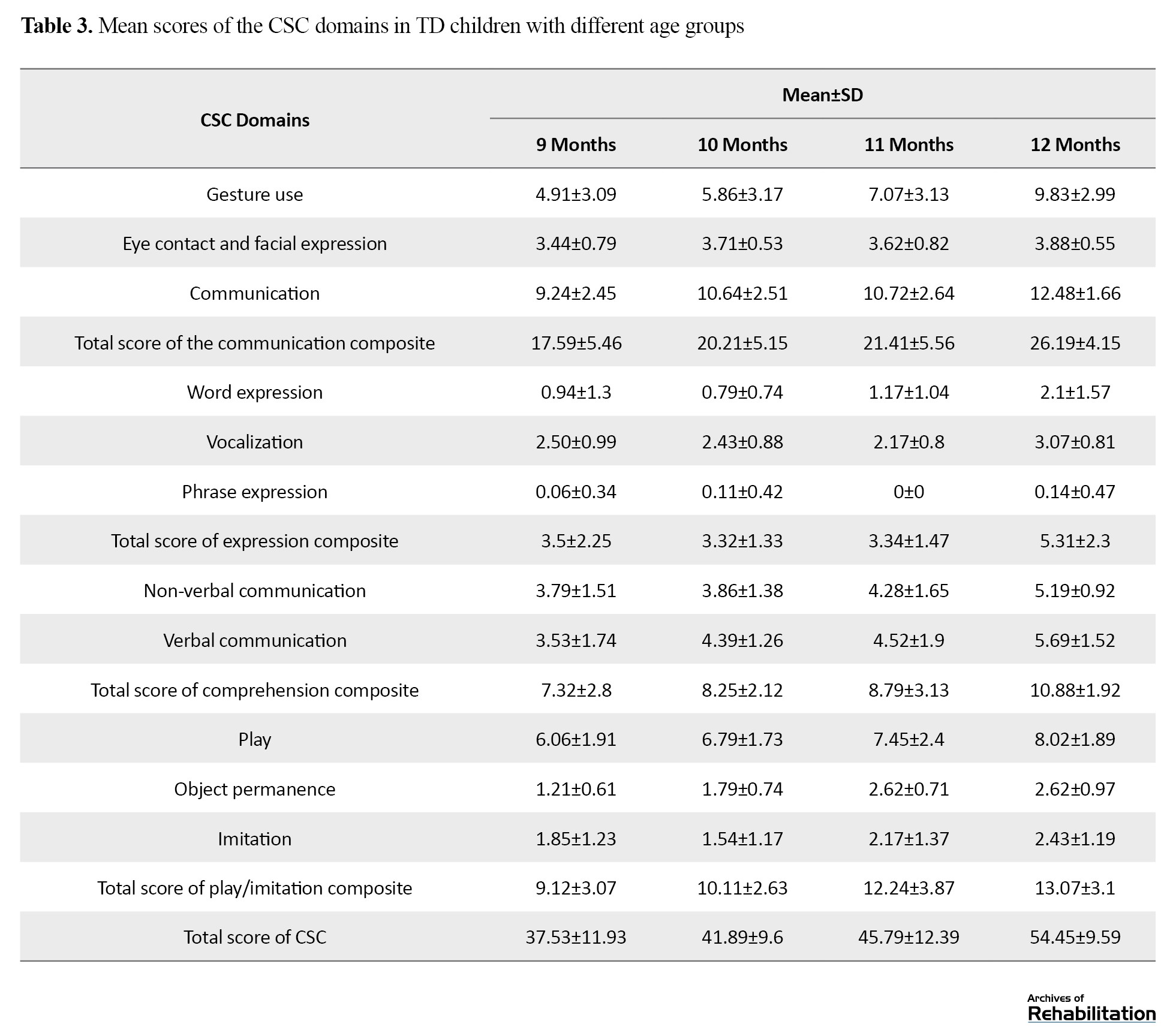

Mean±SD of CSC scores for domains (communication, expression, comprehension, play/imitation) and total are in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 1 illustrates the comparison of mean scores for two groups of children of different ages.

Within-group comparison of children

The within-group comparison of the CSC scores (domain and total) among the three age groups of children with ASD (3, 4, and 5 years) indicated that 5-year-old children had higher scores, but the differences were not significant (P>0.05). For TD children (9–12 months), one-way ANOVA results indicated significant differences among the four age groups (P<0.05). Tukey’s post-hoc test results revealed that 12-month-old TD children scored significantly higher than 9-month and 10-month-old children in all CSC domains and total CSC score (P<0.001). Differences between 11 and 12-month-old TD children were significant in all domains (P<0.001) except for the play/imitation domain. Nine-month-old TD children differed significantly from 11-month-olds in scores of the communication and play/imitation domains and total score, but not from 10-month-old children (P>0.05). No significant differences existed between 10- and 11-month-old TD children (P>0.05).

Between-group comparison of children

The t-test results showed no significant differences in total or domain scores of the CSC between children with ASD (3–5 years) and TD children (9–11 months) (P>0.05), indicating their similar early communication performance. The expression domain scores were slightly higher in children with ASD due to rehabilitation interventions and minimal verbal output, but lower than in 12-month-old TD children. The communication domain scores were significantly lower in children with ASD than in 9–11-month-old TD children (P<0.05). All CSC domains and the total CSC score in ASD were significantly lower than in 12-month-old TD children (P<0.001).

Discussion

In the present study, early communication skills (CSC domains including communication, expression, comprehension, play/imitation) were investigated in 70 Persian-speaking children with ASD aged 3 to 5 years, who had minimal or no verbal output and were in the prelinguistic stage of communicative development. These skills were then compared with those of 132 TD peers aged 9-12 months. The findings indicated that children with ASD scored significantly lower than 12-month-old TD children in all CSC domains.

Comparisons of early communication skills among 3-year, 4-year, and 5-year-old children with ASD revealed no significant differences among age groups. This similarity may be attributed to the age at diagnosis, intervention variability, and ASD heterogeneity. This is consistent with the results of Maes et al., Hamrick et al., and Venker et al. [25, 20, 44]. Other studies have also shown that delays or differences in the development of communication skills in children with ASD can make it difficult to compare them with each other [45].

Among TD children aged 9-12 months, significant differences in early communicative skills were observed, where older children had higher CSC scores, consistent with the results of Bayat et al., Babaei et al., Şimşek et al., and Delehanty and Wetherby, who demonstrated that in children under 24 months, early communication skills develop with the increase of age [30, 31, 46, 47].

Differences between children with ASD and 9–11-month-old TD children were not significant in overall, though TD children scored higher in comprehension, aligning with the results of Trevisan et al. and Dimitrova and Özçalışkan [48, 49]. This finding is probably due to the similarity of the communication performance of children with ASD and TD children aged 9 to 11 months, due to delays in the development of communication skills in children with ASD [19, 26].

The communication scores (eye contact, gesture use, communicative functions) were lower in children with ASD than in any age groups of TD children, reflecting core deficits in communication, consistent with the results of Veness et al., MC Dennis, Manwaring et al., and Wu et al., and Dennis [26, 50–52]. Some studies that examined early communication skills in children with ASD using tools other than the CSC have also reported significant differences and lower communication scores in children with ASD compared to TD children [53]. Other studies have also shown delayed or deviant patterns in expressive gestures, eye contact, and significant impairment in communicative functioning, especially joint attention [54].

Twelve-month-old TD children significantly outperformed children with ASD in all early communication skills, likely due to rapid skill acquisition at age 12 months, widening the developmental gap between the two groups. Studies in this field have shown that in 12-month-old TD children, the number of initial vocabulary words and the variety and form of phonemes have increased and they can have about five expressive words and can often produce linguistic consonants in various syllables, starting to use expressive movements, and their games progress towards early symbolic games [55].

There were some limitations in this study. The ASD group sample size was smaller than the TD group, and the familiarity of ASD children’s parents with communication skills (due to prior rehabilitation experiences) may have influenced responses. Future research should apply the CSC to younger children with ASD cohorts and use larger sample sizes and other groups with developmental language delays.

Conclusion

This is the first study to assess early communication skills in Persian-speaking children with ASD using the CSC tool, and to compare them with TD children matched for developmental—but not chronological—level. Findings reveal that 3–5-year-old children with ASD, despite their older age, display substantial delays in early communication, sometimes performing comparably to much younger TD peers. The results highlight the necessity of early screening and detection of communication delays or deviations in ASD children, and demonstrate the CSC tool’s potential as a brief, parent-report tool for clinical and research use.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1402.102). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents prior to data collection, and all participant information was coded to ensure anonymity.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and data analysis: Fateme Ghovati, Atieh Ashtari, Farin Soleimani, Talieh Zarifian, and Mohsen Vahedi; Investigation: Fateme Ghovati, Atieh Ashtari, Farin Soleimani, and Talieh Zarifian; Methodology: All authors; Review and editing: Fateme Ghovati and Atieh Ashtari; Supervision: Atieh Ashtari and Farin Soleimani; Validation: Atieh Ashtari, Farin Soleimani, and Talieh Zarifian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the health and vaccination centers of Tehran, Iran, and Shahid Beheshti Universities of Medical Sciences and the mothers of children with ASD and TD participating in this study who helped them in this research.

References

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by substantial deficits in communication skills and restricted/repetitive behavior patterns [1]. Early communicative skills emerge during the prelinguistic stage, typically at 9 months of age, when intentional communication begins. These skills encompass behaviors such as gesture use, eye contact, vocalizations, and single-word expression, serving functions like behavior regulation (requesting and rejecting), social interaction, and joint attention [2]. Additionally, key cognitive skills in the prelinguistic stage, such as play, imitation, and object permanence, develop during the initial stage of intentional communication (approximately 9–12 months). Research indicates that these skills are crucial for later language development in both typically developing (TD) children and those with developmental disorders [3, 4]. Children with ASD exhibit significant impairments in communicative skills, including limited or absent use of gestures, eye contact, varied vocalizations, and joint attention compared to TD peers [5–8]. Beyond communication, cognitive abilities are also affected; children with ASD often show deficits in various types of play, particularly pretend and symbolic play, and in imitation [9]. Studies suggest that impairments in early communication and cognitive skills during early childhood increase the risk of ASD development [7, 10]. Given the critical role and vulnerability of these skills in children with ASD, their assessment is essential for early identification of at-risk children and for establishing communication profiles to guide therapeutic interventions [11]. Theoretical frameworks, such as social interaction theory, and intervention models such as the social-pragmatic developmental approach and prelinguistic milieu teaching (PMT), emphasize the importance of assessing these skills in children with ASD, focusing on early detection and individualized treatment [12, 13].

Various methods, including parent–child interaction observations and parent-report checklists, have been used to study early communication in children with ASD and identify at-risk children. Parent-report tools have demonstrated high validity and reliability [14, 15]. Internationally, prominent parent-report tools include the communication and symbolic behavior scales – infant toddler checklist (CSBS-ITC) [16] and the MacArthur–Bates communicative development inventories–1 (CDI-1) [17]. However, the CSBS-ITC does not assess skills such as imitation, nonverbal comprehension, or phrase production, while the CDI-1 primarily focuses on receptive and expressive vocabulary [18, 19]. Numerous studies have examined early communication skills, such as joint attention, imitation, and vocalizations, and their predictive role in later language development using various tools [20–24]. For instance, Hamrick et al. used the autism diagnostic observation schedule–2 (ADOS-2) to evaluate nonverbal communication in children with ASD aged 18–70 months, aiming to improve screening accuracy and reduce diagnostic errors [20]. Maes et al. employed the CDI-1 to assess vocal output (vocalizations and early words) in children with ASD aged 3–5 years, without comparing them to TD peers [25]. Vennes c et al. conducted a longitudinal study using the CSBS DP-ITC and CDI-1 to identify early ASD markers in children aged 12–24 months later diagnosed at age four, comparing them to TD children, those with language impairment, and those with developmental delays; however, no within-group ASD comparisons or examinations of older age groups were performed [26].

In Iran, research on early communication skills has primarily focused on specific abilities, such as nonverbal communication or early vocabulary, in TD children, often to validate screening tools [27–31]. For example, Oryadi-Zanjani developed the children’s nonverbal communication scale (CNCS) for TD children aged 3–18 months but did not apply it to children with ASD [27]. Kazemi et al. examined the psychometric properties of the CDI-1 in TD children aged 8–16 months [32]. This tool has also been used to assess receptive and expressive vocabulary in Persian-speaking children with ASD, for example, in Teimouri et al.’s study on remote interventions [33]. Most Iranian studies on minimally verbal or nonverbal children with ASD emphasized intervention effects on early communicative skills or examined selected abilities [34, 35]. Dadgar et al. used the early social communication scales (ESCSs) to evaluate nonverbal communication in children with ASD aged 3–5 years and assess its relationship with imitation and motor skills [35]. Abdi et al. assessed pivotal response treatment effects in Iranian children with ASD aged 2–6 years using the Persian version of the autism treatment evaluation checklist, a diagnostic tool covering speech, language, communication, socialization, sensory awareness, cognition, and health [36].

A review of Iranian studies reveals that no studies have systematically investigated early communication skills using specialized instruments to compare them between ASD children and their TD peers. One available tool is the communication skills checklist (CSC), developed by Bayat et al. to screen early communication and related cognitive skills in Persian-speaking TD children aged 6–24 months. The CSC has strong psychometric properties and is completed by primary caregivers, typically mothers [37]. This study used the CSC to: (a) assess early communication skills in Persian-speaking minimally verbal or nonverbal children with ASD at the initial intentional communication stage aged 3–5 years, since formal ASD diagnoses in Iran typically occur after age three [38, 39], and expressive language often emerges during this period [25]; (b) compare these skills between age groups in both ASD and TD children; and (c) compare skills between ASD and TD children aged 9–12 months matched for communicative developmental level [40-43].

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a descriptive–analytical study with a cross-sectional design conducted in Tehran, Iran, during 2023–2024. Participants were 70 children with ASD aged 3-5 years and 132 TD children aged 9–12 months. The ASD group was subdivided into three age groups (3, 4, and 5 years), with at least 23 children per group. The TD group was divided into four age groups (9, 10, 11, and 12 months), with at least 25 children per group. The two groups were matched for the communicative developmental level. Inclusion criteria for both groups were being monolingual Persian speakers, residing in Tehran, and having mothers proficient in Persian speaking and writing. For the ASD group, additional inclusion criteria were chronological age 3–5 years; ASD diagnosis by a child psychiatrist based on the DSM-5 criteria, documented in medical records; absence of severe comorbid sensory, motor, metabolic, or genetic syndromes; having at least early intentional communication; and, for verbal children, a spontaneous vocabulary of at most 3–5 words using the CDI-1. For the TD group, additional inclusion criteria were chronological age 9–12 months, no parental developmental concerns, absence of genetic syndromes, physical impairments, or hearing loss, and no preterm birth history, based on medical records or using a researcher-designed checklist. The exclusion criterion for both groups was the incomplete return of questionnaires.

Children with ASD were recruited using a convenience sampling method from rehabilitation centers in Tehran. Eligibility was assessed using clinical records and CDI-1 results. If the criteria were met, informed consent was obtained from their mothers. For the TD group, recruitment was conducted using two approaches: In-person and online sampling (due to the onset of the respiratory disease season during data collection). In the in-person sampling method, health and vaccination centers affiliated with Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Iran University of Medical Sciences, and Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences were first randomly selected. The research team then attended these centers, selected eligible boys and girls using a convenience sampling method. In the online sampling method, recruitment was also conducted using a convenience method following the distribution of an invitation poster on social media platforms such as Instagram. The poster provided information about the study objectives. Interested mothers contacted the research team, and the inclusion criteria were assessed through an online interview with the principal investigator.

Instruments

Data collection in the present study was conducted using three instruments: A demographic form, the CSC, and the CDI-1.

The CSC is a validated tool in Persian for screening communication skills in TD children aged 6–24 months, which is completed by parents or primary caregivers (mothers). It includes 36 items (33 on a three-point Likert scale, and 3 on a five-point scale) assessing prelinguistic domains: Communication (16 items, max score 32; gestures, eye contact, facial expressions, functions), expression (4 items, max score 12; word production, vocalizations, phrases), comprehension (7 items, max score 14; verbal/nonverbal), and play/imitation (9 items, max score 20; play types, imitation, object permanence). The total score ranges from 0 to 78. It has a Cronbach’s α of 0.95 and a test re-test reliability of 0.93 [37].

The CDI-1 is a parent-report tool assessing receptive/expressive vocabulary and gesture use in TD children aged 8–16 months, also applicable to older children with developmental disorders like ASD. The Persian version, validated by Kazemi et al., has a Cronbach’s α of 0.43–0.98 across subscales [32].

Data analysis

For performing data analysis, SPSS software, version 25 was used. Descriptive statistics were used to describe demographic factors (age, gender, parents’ education/occupation). Mean±SD were used to describe the CSC domain scores. Data normality was confirmed. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc was used to compare the scores within ASD and TD groups. Independent t-test was used to compare the scores between the groups.

Results

Characteristics of participants

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants in the two groups.

It should be noted that some mothers of children with ASD, after participation in the study, were not willing to provide information about their own or their husbands’ employment and educational level for personal reasons.

Early communication skills in children with ASD and TD children

Mean±SD of CSC scores for domains (communication, expression, comprehension, play/imitation) and total are in Tables 2 and 3.

Figure 1 illustrates the comparison of mean scores for two groups of children of different ages.

Within-group comparison of children

The within-group comparison of the CSC scores (domain and total) among the three age groups of children with ASD (3, 4, and 5 years) indicated that 5-year-old children had higher scores, but the differences were not significant (P>0.05). For TD children (9–12 months), one-way ANOVA results indicated significant differences among the four age groups (P<0.05). Tukey’s post-hoc test results revealed that 12-month-old TD children scored significantly higher than 9-month and 10-month-old children in all CSC domains and total CSC score (P<0.001). Differences between 11 and 12-month-old TD children were significant in all domains (P<0.001) except for the play/imitation domain. Nine-month-old TD children differed significantly from 11-month-olds in scores of the communication and play/imitation domains and total score, but not from 10-month-old children (P>0.05). No significant differences existed between 10- and 11-month-old TD children (P>0.05).

Between-group comparison of children

The t-test results showed no significant differences in total or domain scores of the CSC between children with ASD (3–5 years) and TD children (9–11 months) (P>0.05), indicating their similar early communication performance. The expression domain scores were slightly higher in children with ASD due to rehabilitation interventions and minimal verbal output, but lower than in 12-month-old TD children. The communication domain scores were significantly lower in children with ASD than in 9–11-month-old TD children (P<0.05). All CSC domains and the total CSC score in ASD were significantly lower than in 12-month-old TD children (P<0.001).

Discussion

In the present study, early communication skills (CSC domains including communication, expression, comprehension, play/imitation) were investigated in 70 Persian-speaking children with ASD aged 3 to 5 years, who had minimal or no verbal output and were in the prelinguistic stage of communicative development. These skills were then compared with those of 132 TD peers aged 9-12 months. The findings indicated that children with ASD scored significantly lower than 12-month-old TD children in all CSC domains.

Comparisons of early communication skills among 3-year, 4-year, and 5-year-old children with ASD revealed no significant differences among age groups. This similarity may be attributed to the age at diagnosis, intervention variability, and ASD heterogeneity. This is consistent with the results of Maes et al., Hamrick et al., and Venker et al. [25, 20, 44]. Other studies have also shown that delays or differences in the development of communication skills in children with ASD can make it difficult to compare them with each other [45].

Among TD children aged 9-12 months, significant differences in early communicative skills were observed, where older children had higher CSC scores, consistent with the results of Bayat et al., Babaei et al., Şimşek et al., and Delehanty and Wetherby, who demonstrated that in children under 24 months, early communication skills develop with the increase of age [30, 31, 46, 47].

Differences between children with ASD and 9–11-month-old TD children were not significant in overall, though TD children scored higher in comprehension, aligning with the results of Trevisan et al. and Dimitrova and Özçalışkan [48, 49]. This finding is probably due to the similarity of the communication performance of children with ASD and TD children aged 9 to 11 months, due to delays in the development of communication skills in children with ASD [19, 26].

The communication scores (eye contact, gesture use, communicative functions) were lower in children with ASD than in any age groups of TD children, reflecting core deficits in communication, consistent with the results of Veness et al., MC Dennis, Manwaring et al., and Wu et al., and Dennis [26, 50–52]. Some studies that examined early communication skills in children with ASD using tools other than the CSC have also reported significant differences and lower communication scores in children with ASD compared to TD children [53]. Other studies have also shown delayed or deviant patterns in expressive gestures, eye contact, and significant impairment in communicative functioning, especially joint attention [54].

Twelve-month-old TD children significantly outperformed children with ASD in all early communication skills, likely due to rapid skill acquisition at age 12 months, widening the developmental gap between the two groups. Studies in this field have shown that in 12-month-old TD children, the number of initial vocabulary words and the variety and form of phonemes have increased and they can have about five expressive words and can often produce linguistic consonants in various syllables, starting to use expressive movements, and their games progress towards early symbolic games [55].

There were some limitations in this study. The ASD group sample size was smaller than the TD group, and the familiarity of ASD children’s parents with communication skills (due to prior rehabilitation experiences) may have influenced responses. Future research should apply the CSC to younger children with ASD cohorts and use larger sample sizes and other groups with developmental language delays.

Conclusion

This is the first study to assess early communication skills in Persian-speaking children with ASD using the CSC tool, and to compare them with TD children matched for developmental—but not chronological—level. Findings reveal that 3–5-year-old children with ASD, despite their older age, display substantial delays in early communication, sometimes performing comparably to much younger TD peers. The results highlight the necessity of early screening and detection of communication delays or deviations in ASD children, and demonstrate the CSC tool’s potential as a brief, parent-report tool for clinical and research use.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1402.102). Written informed consent was obtained from all parents prior to data collection, and all participant information was coded to ensure anonymity.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and data analysis: Fateme Ghovati, Atieh Ashtari, Farin Soleimani, Talieh Zarifian, and Mohsen Vahedi; Investigation: Fateme Ghovati, Atieh Ashtari, Farin Soleimani, and Talieh Zarifian; Methodology: All authors; Review and editing: Fateme Ghovati and Atieh Ashtari; Supervision: Atieh Ashtari and Farin Soleimani; Validation: Atieh Ashtari, Farin Soleimani, and Talieh Zarifian.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the health and vaccination centers of Tehran, Iran, and Shahid Beheshti Universities of Medical Sciences and the mothers of children with ASD and TD participating in this study who helped them in this research.

References

- Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB. The American psychiatric association publishing textbook of psychopharmacology. Washington: American Psychiatric Publication; 2017. [Link]

- Beuker KT, Rommelse NNJ, Donders R, Buitelaar JK. Development of early communication skills in the first two years of life. Infant Behavior & Development. 2013; 36(1):71-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.11.001] [PMID]

- Eadie PA, Ukoumunne O, Skeat J, Prior MR, Bavin E, Bretherton L, et al. Assessing early communication behaviours: Structure and validity of the communication and symbolic behaviour scales-developmental profile (CSBS-DP) in 12-month-old infants. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2010; 45(5):572-85. [DOI:10.3109/13682820903277944] [PMID]

- Barrett M. The development of language. London: Psychology Press; 2016. [DOI:10.4324/9781315784694]

- Kaplan RM, Saccuzzo DP. Psychological testing: Principles, applications, and issues. Belmont: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning; 2001. [Link]

- Wetherby AM, Prizant BM. Profiling communication and symbolic abilities in young children. Journal of Childhood Communication Disorders. 1993; 15(1):23-32. [DOI:10.1177/152574019301500105]

- Crais E, Ogletree BT. Prelinguistic communication development. In: Keen D, Meadan H, Brady NC, Halle JW, editors. Prelinguistic and minimally verbal communicators on the autism spectrum. Singapore: Springer Singapore; 2016. [DOI:10.1007/978-981-10-0713-2_2]

- Scharf RJ, Scharf GJ, Stroustrup A. Developmental milestones. Pediatrics in Review. 2016; 37(1):25-38. [DOI:10.1542/pir.2014-0103] [PMID]

- Bruce B, Kornfält R, Radeborg K, Hansson K, Nettelbladt U. Identifying children at risk for language impairment: Screening of communication at 18 months. Acta Paediatr. 2003; 92(9):1090-5. [DOI:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2003.tb02583.x] [PMID]

- Laakso ML. Prelinguistic skills and early interactional context as predictors of children’s language development [doctoral thesis]. Jyvaskyla: University of Jyväskylä; 1999. [Link]

- Molini Avejonas DR, Nanakuma Matsumoto MM, Cardilli Dias D. How does the child hear and talk? International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology. 2022; 1-11. [Link]

- Turner JH. A theory of social interaction. Redwood: Stanford University Press; 1988. [Link]

- Davis PH, Elsayed H, Crais ER, Watson LR, Grzadzinski R. Caregiver responsiveness as a mechanism to improve social communication in toddlers: Secondary analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Autism Research. 2022; 15(2):366-78. [DOI:10.1002/aur.2640] [PMID]

- Stolt S. Internal consistency and concurrent validity of the parental report instrument on language in pre-school-aged children-The Finnish communicative development inventory III. First Language. 2023; 43(5):492-515. [DOI:10.1177/01427237231167301]

- Trembath D, Paynter J, Sutherland R, Tager-Flusberg H. Assessing communication in children with autism spectrum disorder who are minimally verbal. Current Developmental Disorders Reports. 2019; 6(3):103-10. [DOI:10.1007/s40474-019-00171-z]

- Wetherby AM, Prizant BM. Communication and symbolic behavior scales: Developmental profile. Washington: Paul H Brookes Publishing Co.; 2002. [DOI:10.1037/t11529-000]

- Fenson L, Marchman VA, Thal DJ, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E. MacArthur-bates communicative development inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co; 2007. [Link]

- Marchman VA, Dale PS. The MacArthur-bates communicative development inventories: Updates from the CDI advisory board. Frontiers in Psychology. 2023; 14:1170303. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1170303] [PMID]

- Wetherby AM, Allen L, Cleary J, Kublin K, Goldstein H. Validity and reliability of the communication and symbolic behavior scales developmental profile with very young children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002; 45(6):1202-18. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2002/097)] [PMID]

- Hamrick LR, Ros-Demarize R, Kanne S, Carpenter LA. Profiles of nonverbal skills used by young pre-verbal children with autism on the ADOS-2: Relation to screening disposition and outcomes. Autism Research. 2024; 17(11):2370-85. [DOI:10.1002/aur.3229] [PMID]

- Bottema-Beutel K. Associations between joint attention and language in autism spectrum disorder and typical development: A systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Autism Research. 2016; 9(10):1021-35. [DOI:10.1002/aur.1624] [PMID]

- Ambarchi Z, Boulton KA, Thapa R, Arciuli J, DeMayo MM, Hickie IB, et al. Social and joint attention during shared book reading in young autistic children: A potential marker for social development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2024; 65(11):1441-52. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.13993] [PMID]

- Bopp KD, Mirenda P. Prelinguistic predictors of language development in children with autism spectrum disorders over four-five years. Journal of Child Language. 2011; 38(3):485-503. [DOI:10.1017/S0305000910000140] [PMID]

- Kilili-Lesta M, Voniati L, Giannakou K. Early gesture as a predictor of later language outcome for young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD): A systematic literature review. Current Developmental Disorders Reports. 2022; 9:110-26. [DOI:10.1007/s40474-022-00250-8]

- Maes P, Weyland M, Kissine M. Describing (pre)linguistic oral productions in 3- to 5-year-old autistic children: A cluster analysis. Autism. 2023; 27(4):967-982. [DOI:10.1177/13623613221122663] [PMID]

- Veness C, Prior M, Bavin E, Eadie P, Cini E, Reilly S. Early indicators of autism spectrum disorders at 12 and 24 months of age: A prospective, longitudinal comparative study. Autism. 2012; 16(2):163-77. [DOI:10.1177/1362361311399936] [PMID]

- Oryadi-Zanjani MM. Development of the childhood nonverbal communication scale. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020; 50(4):1238-48. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-019-04356-8] [PMID]

- Sheibani F, Ghoreishi ZS, Nilipour R, Pourshahbaz A, Mohammad Zamani S. Validity and reliability of a language development scale for Persian-speaking children aged 2-6 years. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2020; 45(4):259-68. [DOI:10.30476/ijms.2020.72538.0] [PMID]

- Ghazvini A, Yadegari F, Yoosefi A, Maleki F. [Development of nonverbal request skills in persian typically developing 9-to-30-month children (Persian)]. The Scientific Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2017; 6(2):122-30. [Link]

- Bayat N, Ashtari A, Vahedi M. The early prelinguistic skills in Iranian Infants and toddlers. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2021;19(4):441-54. [DOI:10.32598/irj.19.4.1605.1]

- Babaei Z, Zarifian T, Ashtari A, Bakhshi E. [Study of deictic gesture in normally developing Persian-speaking children between 12 to 18 months old: A longitudinal study (Persian)]. Koomesh. 2017; 19(4):894-900. [Link]

- Kazemi Y, Nematzadeh S, Hajian T, Heidari M, Daneshpajouh T, Mirmoeini A. [The validity and reliability coefficient of persian translated mcarthur-bates communicative development inventory (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Rehabilitation Sciences. 2008; 4(1):1-7. [DOI:10.22122/jrrs.v4i1.29]

- Mohamadi R, Teymouri Sangani M, Nokhostin Ansari N, Soleymani Z. A preliminary study of telepractice prelinguistic milieu teaching for children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Iranian Medical Council. 2022; 5(3):471-7. [DOI:10.18502/jimc.v5i3.10943]

- Karampour M, Hashemi Razini H, Gholamali Lavasani M, Vakili S. The effectiveness of an intervention program based on functional communication training on the social and communication skills of children with autism spectrum disorder. Quarterly Journal of Child Mental Health. 2022; 9(2):78-91. [DOI:10.52547/jcmh.9.2.7]

- Dadgar H, Rad JA, Soleymani Z, Khorammi A, McCleery J, Maroufizadeh S. The relationship between motor, imitation, and early social communication skills in children with autism. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2017; 12(4):236. [PMID]

- Abdi F, Rezai H, Tahmasebi N, Dastoorpoor M. The effectiveness of pivotal response treatment training for mothers on the communication skills of children with non-verbal autism spectrum disorder: A randomized clinical trial. Middle East Journal of Rehabilitation and Health Studies. 2023; 11(2):e127597. [DOI:10.5812/mejrh-127597]

- Bayat N, Ashtari A, Vahedi M. The development and psychometric assessment of communication skills checklist for 6- to 24-month-old Persian children. Applied Neuropsychology. Child. 2023; 12(2):122-30. [DOI:10.1080/21622965.2022.2039654] [PMID]

- Samadi SA, McConkey R, Mahmoodizadeh A. Identifying children with autism spectrum disorders in Iran using the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised. Autism. 2021; 25(4):1009-19. [DOI:10.1177/1362361320974558] [PMID]

- Samadi SA, McConkey R, Abdollahi-Boghrabadi G, Pourseid-Mohammad M. Developmental signs of autism spectrum disorder in Iranian Pre-Schoolers. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2021; 58:e69-e73. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2021.01.006] [PMID]

- Owens Jr RE. Language development: An introduction (9th ed). London: Pearson Education, Inc; 2015. [Link]

- Mundy P, Sigman M, Kasari C. A longitudinal study of joint attention and language development in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 1990; 20(1):115-28. [DOI:10.1007/BF02206861] [PMID]

- Chiang CH, Soong WT, Lin TL, Rogers SJ. Nonverbal communication skills in young children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2008; 38(10):1898-906. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-008-0586-2] [PMID]

- Paul R, Norbury CF, Gosse C. Language disorders from infancy through adolescence: Language disorders from infancy through adolescence. Edinburgh: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2018. [Link]

- Venker CE, Eernisse ER, Saffran JR, Weismer SE. Individual differences in the real-time comprehension of children with ASD. Autism Research. 2013; 6(5):417-32. [DOI:10.1002/aur.1304] [PMID]

- Senju A, Johnson MH. Atypical eye contact in autism: Models, mechanisms and development. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2009; 33(8):1204-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.06.001] [PMID]

- Şimşek KN, Günhan Şenol NE, Birol NY, Yaşar Gündüz E. Investigation of communicative behaviors and communication functions of Turkish individuals with autism spectrum disorder through Communication Matrix. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 2024; 1-16. [DOI:10.1080/20473869.2024.2331836]

- Delehanty AD, Wetherby AM. Rate of communicative gestures and developmental outcomes in toddlers with and without autism spectrum disorder during a home observation. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2021; 30(2):649-62. [DOI:10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00206] [PMID]

- Trevisan DA, Hoskyn M, Birmingham E. Facial expression production in autism: A meta-analysis. Autism Research. 2018; 11(12):1586-601. [DOI:10.1002/aur.2037] [PMID]

- Dimitrova N, Özçalışkan Ş. Identifying patterns of similarities and differences between gesture production and comprehension in autism and typical development. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 2022; 46(2):173-96. [DOI:10.1007/s10919-021-00394-y] [PMID]

- Manwaring SS, Stevens AL, Mowdood A, Lackey M. A scoping review of deictic gesture use in toddlers with or at-risk for autism spectrum disorder. Speech and Language Impairments in Autism. 2018; 3:2396941517751891. [DOI:10.1177/2396941517751891]

- Wu D, Wolff JJ, Ravi S, Elison JT, Estes A, Paterson S, et al. Infants who develop autism show smaller inventories of deictic and symbolic gestures at 12 months of age. Autism Research. 2024; 17(4):838-51. [DOI:10.1002/aur.3092] [PMID]

- McDaniel J, Brady NC, Warren SF. Effectiveness of responsivity intervention strategies on prelinguistic and language outcomes for children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of group and single case studies. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2022; 52(11):4783-816. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-021-05331-y] [PMID]

- Wetherby AM. Understanding and measuring social communication in children with autism spectrum disorders. Social and Communication Development in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2006; 18(3):3-4. [Link]

- Wetherby AM, Watt N, Morgan L, Shumway S. Social communication profiles of children with autism spectrum disorders late in the second year of life. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2007; 37(5):960-75. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-006-0237-4] [PMID]

- Paul R, Norbury C. Language disorders from infancy through adolescence-E-book. Edinburgh: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012. [Link]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Speech & Language Pathology

Received: 5/05/2025 | Accepted: 23/09/2025 | Published: 1/10/2025

Received: 5/05/2025 | Accepted: 23/09/2025 | Published: 1/10/2025

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |