Volume 26, Issue 3 (Autumn 2025)

jrehab 2025, 26(3): 328-343 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Gharib M, Shayestehazar M, Kazemi K, Moradi M, Nezamoddini M. The Relationship Between Gait Parameters, Behavioral Problems, and Health-related Quality of Life in Children With Cerebral Palsy. jrehab 2025; 26 (3) :328-343

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3628-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3628-en.html

1- Orthopedic Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Science, Sari, Iran. , gharib_masoud@yahoo.com

2- Orthopedic Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Science, Sari, Iran.

3- Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

2- Orthopedic Research Center, Mazandaran University of Medical Science, Sari, Iran.

3- Department of Rehabilitation Sciences, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1705 kb]

(292 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1781 Views)

Full-Text: (314 Views)

Introduction

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the predominant childhood physical disability, with a global incidence rate of about 2–3 per 1,000 live births [1, 2]. This lifelong neuromotor condition results from non-progressive brain development disturbances during pregnancy or infancy, leading to persistent challenges in motor control and postural stability [3]. Key symptoms include muscle stiffness, reduced strength, and irregular coordination, often manifesting as visible gait abnormalities [4]. These gait abnormalities not only limit mobility but also reduce independence and the ability to perform daily activities [5]. The severity and presentation of gait disorders in children with CP vary widely, ranging from mild limping to complete inability to walk [6], influenced by factors such as CP type, disease severity, age, and treatment efficacy [7].

While motor impairments in CP are well-documented, their association with behavioral and emotional disorders has received less attention [8]. Children with CP are at higher risk of developing co-occurring behavioral disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [9, 10], anxiety [11], depression, and emotional dysregulation [8]. These behavioral disorders are not simply secondary to neurological disorders; they are exacerbated by the environmental and social limitations caused by physical disability [3, 12]. Limited participation in educational, social, and recreational activities can lead to isolation, low self-esteem, and increased behavioral disorders [13]. The comorbidity of motor and psychological issues underscores the need for a comprehensive, multidisciplinary management approach to CP [14].

Quality of life (QoL), as one of the key indicators in evaluating the outcomes of pediatric rehabilitation, encompasses physical health, emotional well-being, social functioning, and psychological health [11, 12]. Evidence from multiple studies shows that children with CP generally have a lower QoL compared to their typically developing peers. This reduction is mainly due to physical limitations such as motor impairments, chronic pain, fatigue, and behavioral problems [15]. Mobility or gait plays a pivotal role in determining individual independence, participation in daily activities, and overall QoL [16]. Despite extensive CP research, most studies have separately examined domains such as gait biomechanics [5], epidemiology of behavioral disorders [17], and QoL determinants [18]. Few studies have explored the complex interaction between these domains [19, 20]. This research gap is concerning, considering that new approaches to care emphasize comprehensive, patient-centered methods. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the relationships between gait function, behavioral disorders, and QoL in children with CP. By analyzing these multidimensional interactions, the study seeks to provide deeper insights into QoL determinants in this population. The findings can be helpful for developing targeted multidisciplinary interventions integrating physical and psychological rehabilitation services, and ultimately improving functional outcomes and overall well-being of CP patients.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This is an observational cross-sectional study. The study population consists of children aged 6–12 years with a confirmed CP diagnosis, including spastic, dyskinetic, ataxic, or mixed subtypes in Mazandaran Province, Iran. The inclusion criteria were being at gross motor function classification system (GMFCS) levels of I, II, III, indicating independent or minimally assisted walking ability, having sufficient cognitive capacity to understand and follow instructions, and parental or guardian consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were severe cognitive impairment precluding participation, orthopedic surgery, or receiving botulinum toxin injections in the past six months, and concurrence of neurological or musculoskeletal disorders unrelated to CP. The participants were enrolled using a purposive sampling method from those referred to governmental and private rehabilitation clinics and special schools in Mazandaran Province. The sample size was determined at 60 using G*Power (effect size: 0.3, power: 80%, three predictors).

Assessments

Data collection began with demographic/clinical recording. Demographic/clinical data included age, sex, CP subtype, GMFCS level, and intervention history (e.g. medical treatment, physiotherapy, and use of assistive devices). The GMFCS was used for motor function classification. It is a standardized 5-level system that classifies children with CP based on self-initiated motor abilities (sitting, walking). We used the Persian version of this tool, which has already been validated [21]. The functional mobility scale (FMS) was used to evaluate mobility across 5-, 50-, and 500-meter distances on a 6-point scale from 1 (wheelchair dependence) to 6 (complete independence). This observational tool, completed by therapists or researchers, quantifies assistance levels required for mobility, providing an objective measure of functional gait ability. We used the Persian version of FMS, which has already been validated [22].

The children were then asked to walk at his/her desired speed along a 10-meter path and the relevant gait parameters were recorded. The pediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL CP Module) was used to assess health-related QoL at physical, emotional, social, and school functioning domains. Both parent-proxy and child self-report versions were used for comprehensive QoL evaluation. We used the Persian version of this tool, which has already been validated [23]. The child behavior checklist (CBCL) was used for behavioral and emotional assessment. It is a common parent-report instrument that evaluates internalizing behaviors such as anxiety and depression, as well as externalizing behaviors including aggression and hyperactivity in children. We used the Persian version of this tool, which has already been validated [24]. Parents completed the CBCL and PedsQL CP module (parent-proxy), while children completed the PedsQL CP module (self-report).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted in SPSS software, version 27. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics were first used to describe demographic characteristics, clinical features, and study outcomes. Continuous data were described using Mean±SD, while categorical data were expressed using frequencies and percentages. Spearman’s correlation test examined relationships between gait parameters, QoL scores, and behavioral scores. Multiple linear regression models identified the QoL predictors, considering gait parameters and behavioral scores as independent variables.

Results

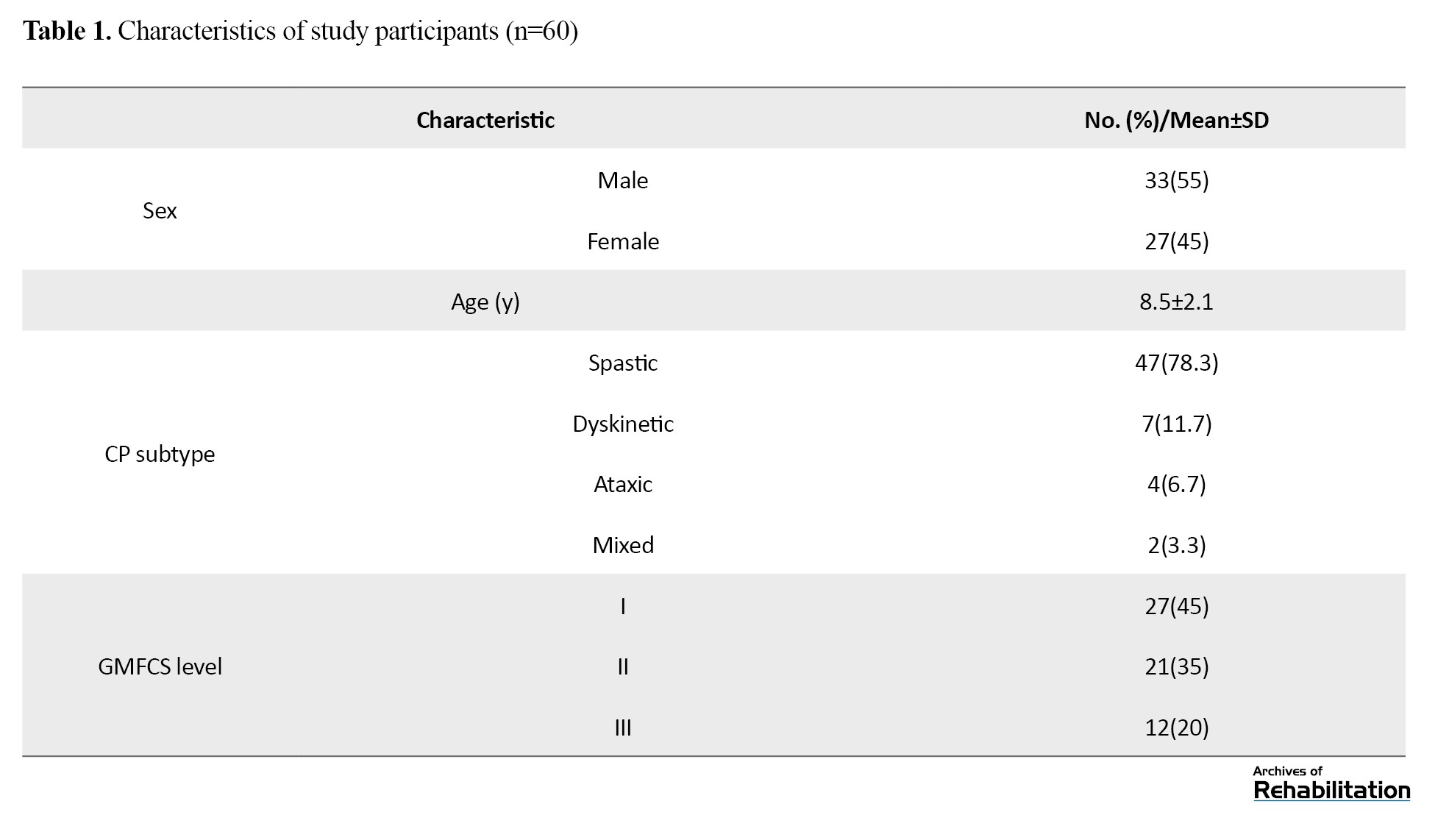

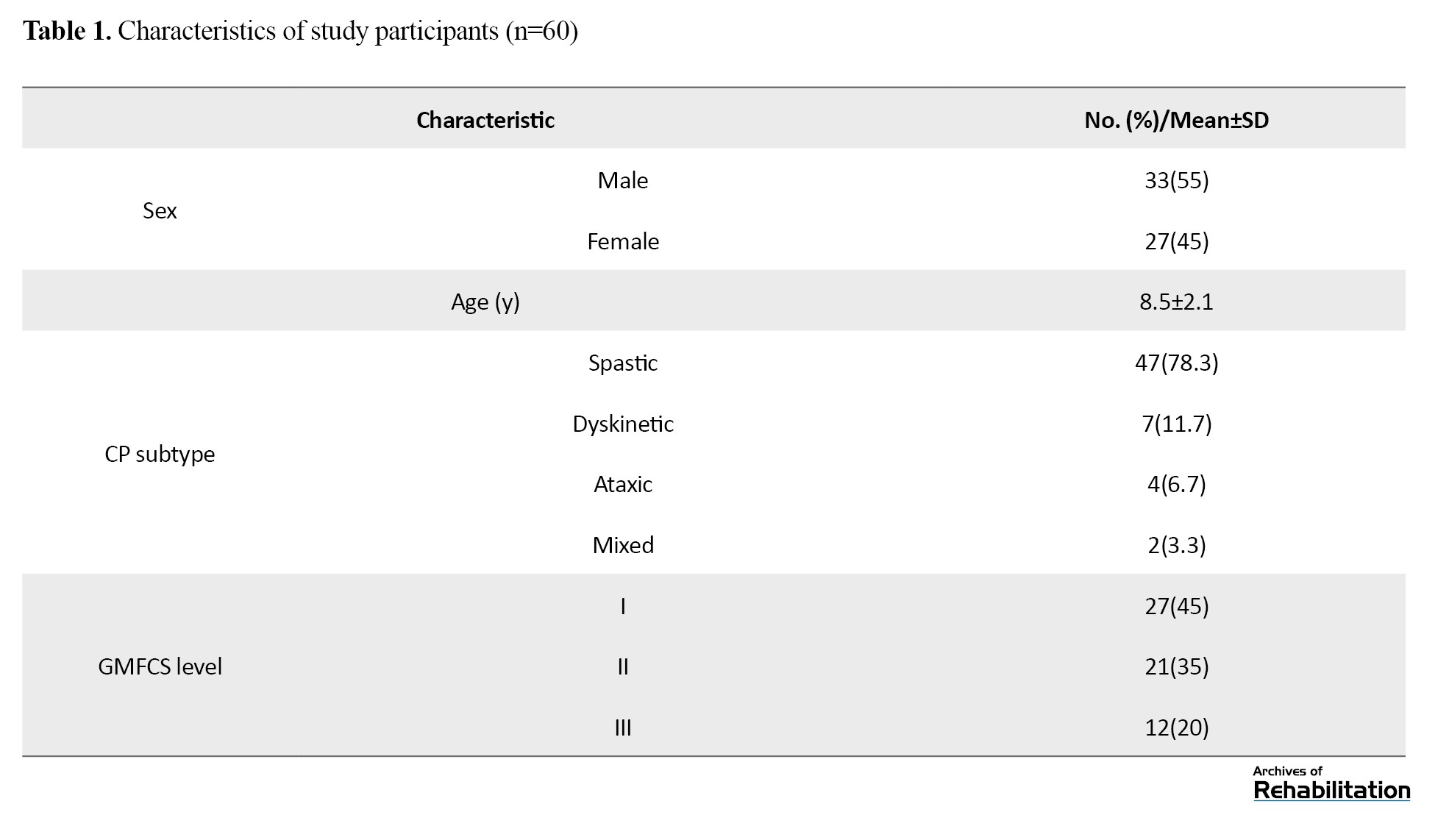

Among 60 children with CP, 33 were male and 27 were female, with a mean age of 8.5±2.1 years. The majority were classified with spastic CP (78.3%), followed by dyskinetic (11.7%), ataxic (6.7%), and mixed (3.3%) subtypes. Regarding gross motor function, 45% of participants were at GMFCS level I, 35% at level II, and 20% at level III (Table 1).

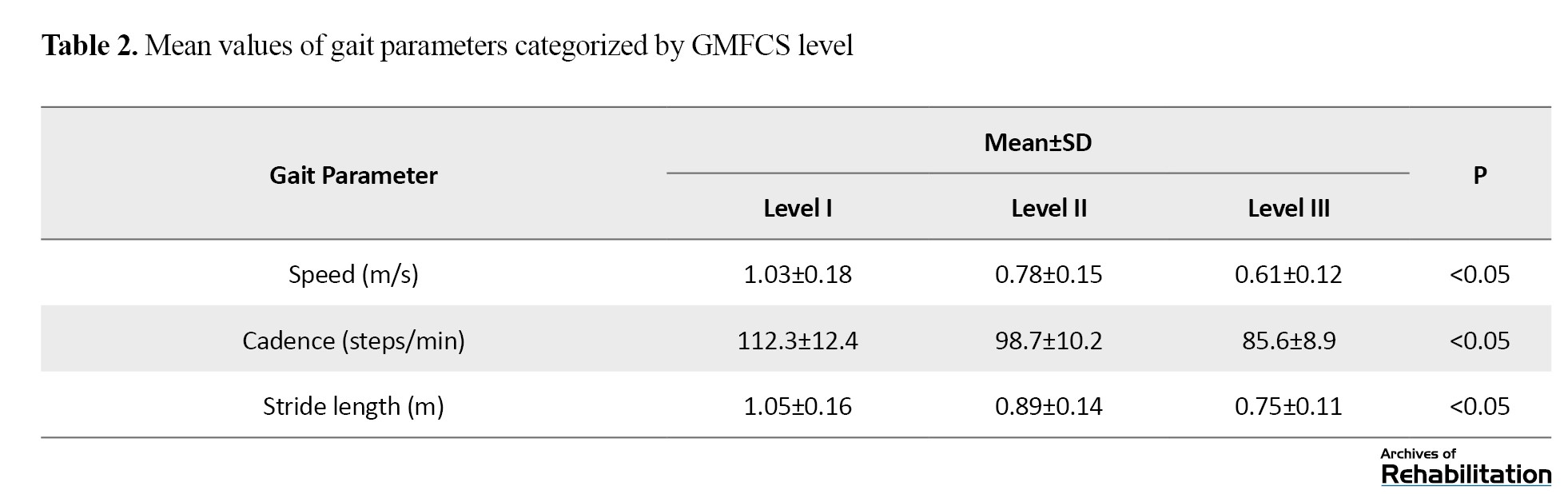

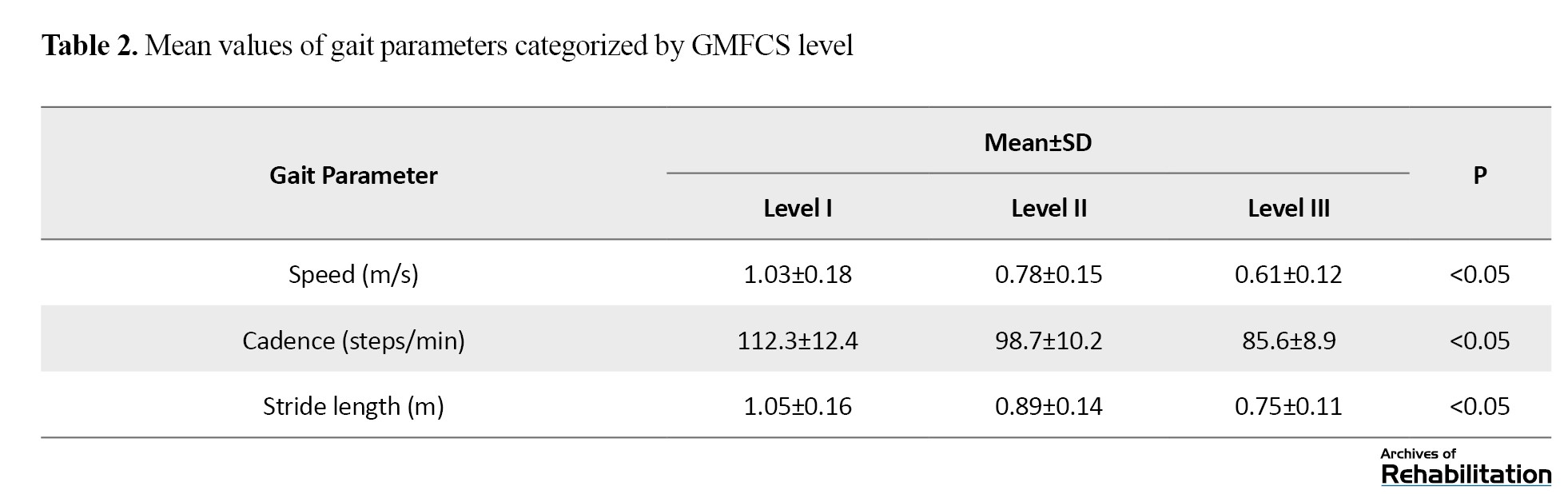

As shown in Table 2, significant differences were observed in gait parameters among children based on the GMFCS level.

Gait speed decreased from 1.03 m/s in children at level I to 0.61 m/s in children at level III (P<0.05). The cadence decreased from 112.3 steps/min (level I) to 85.6 steps/min (Level III), and stride length declined from 1.05 m to 0.75 m from level I to II, both of which were statistically significant (P<0.05).

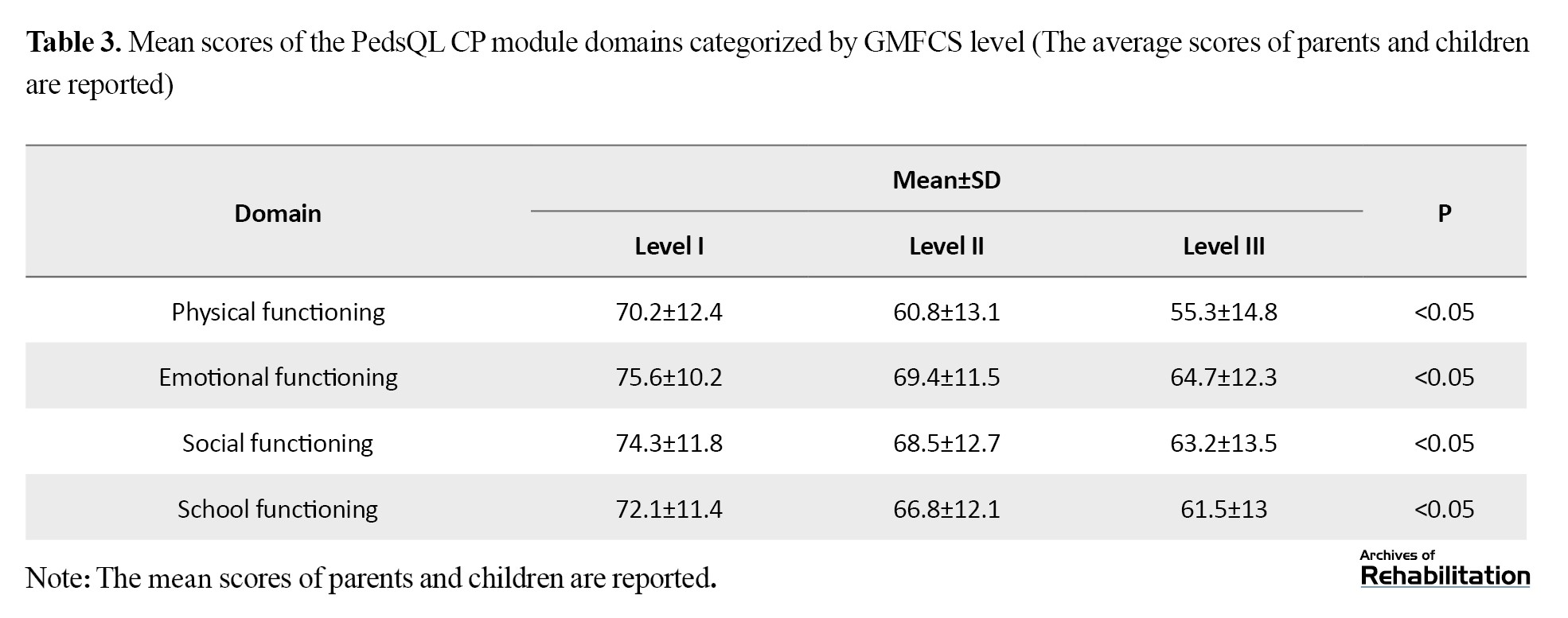

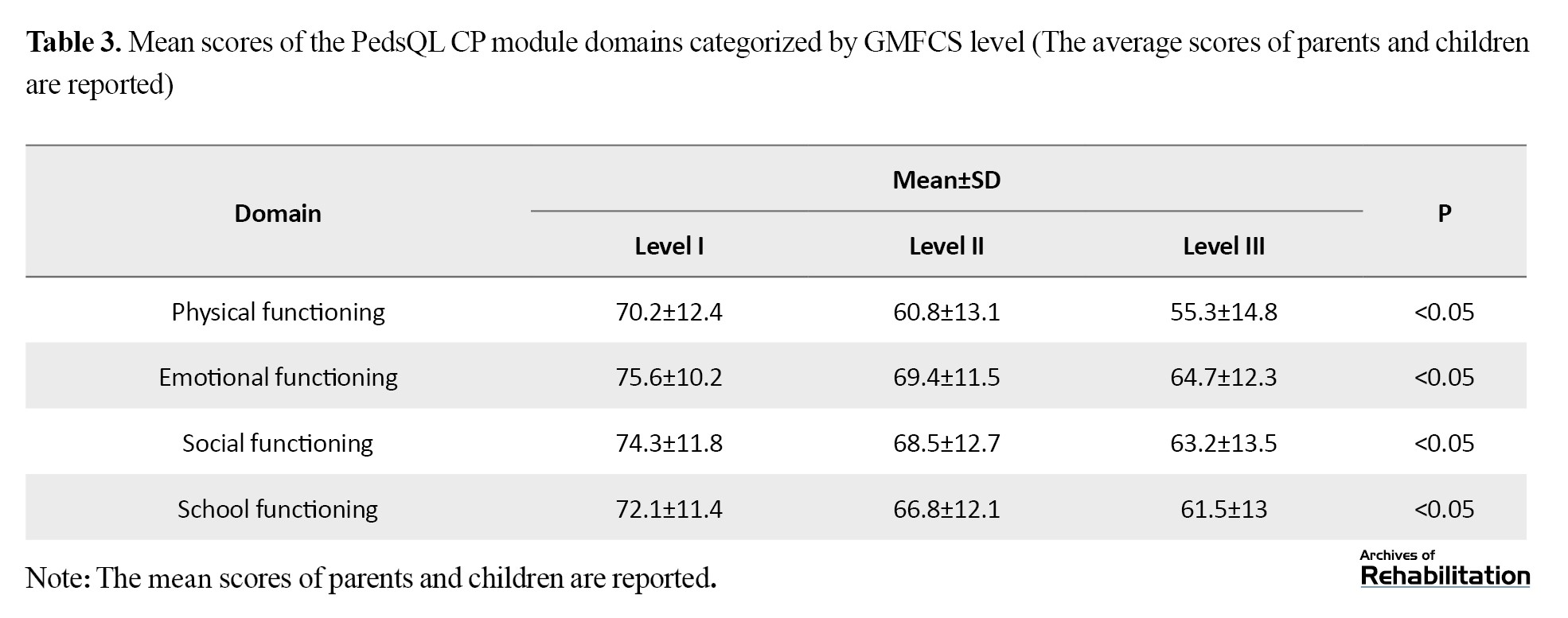

According to Table 3, the PedsQL CP module score indicated a moderate QoL with a total score of 68.4±12.3.

The domain-specific total scores were as follows: Physical functioning: 62.5±14.2, emotional functioning: 71.3±11.8, social functioning: 70.8±13.1, and school functioning: 69.1±12.5. The results reflected significantly lower QoL ratings compared to child self-report (P<0.05).

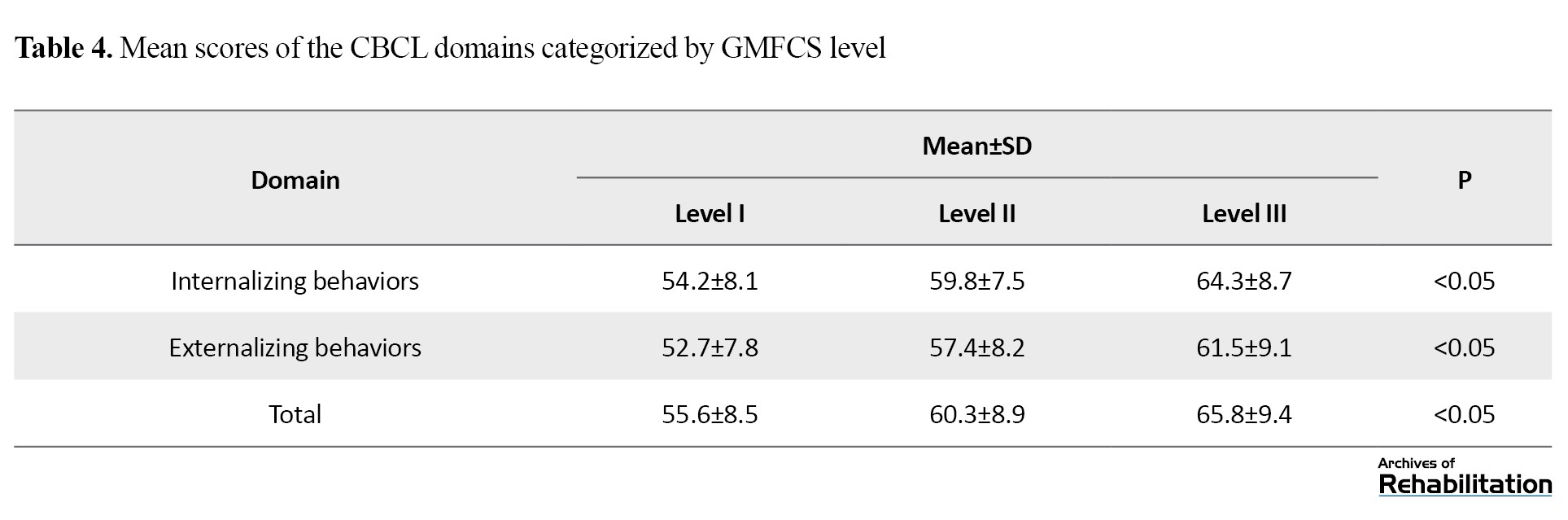

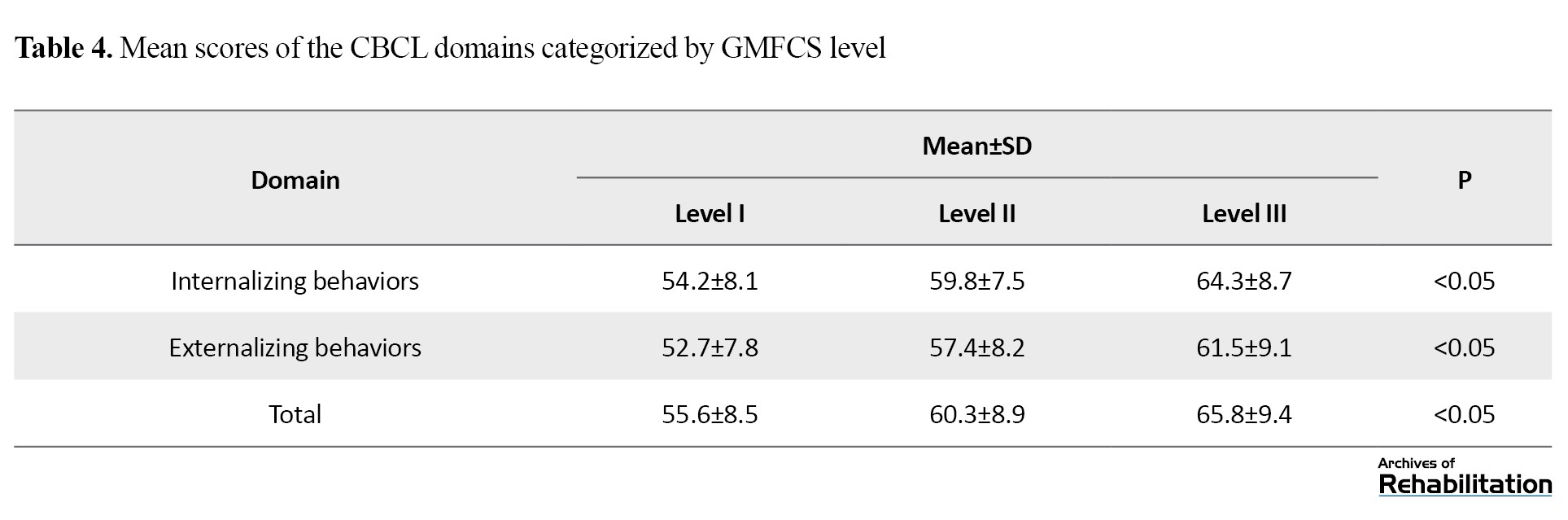

The results reported in Table 4 regarding the CBCL score based on the GMFCS level indicated a notable prevalence of behavioral problems in children with CP.

The mean total CBCL score was 58.7±9.4. Also, it was found that 35% of the children had internalizing behavioral problems such as anxiety and depression, while 28% exhibited externalizing behavioral problems, such as aggression and ADHD symptoms. Notably, the domain scores of the CBCL were significantly different among children based on the GMFCS level (P<0.05).

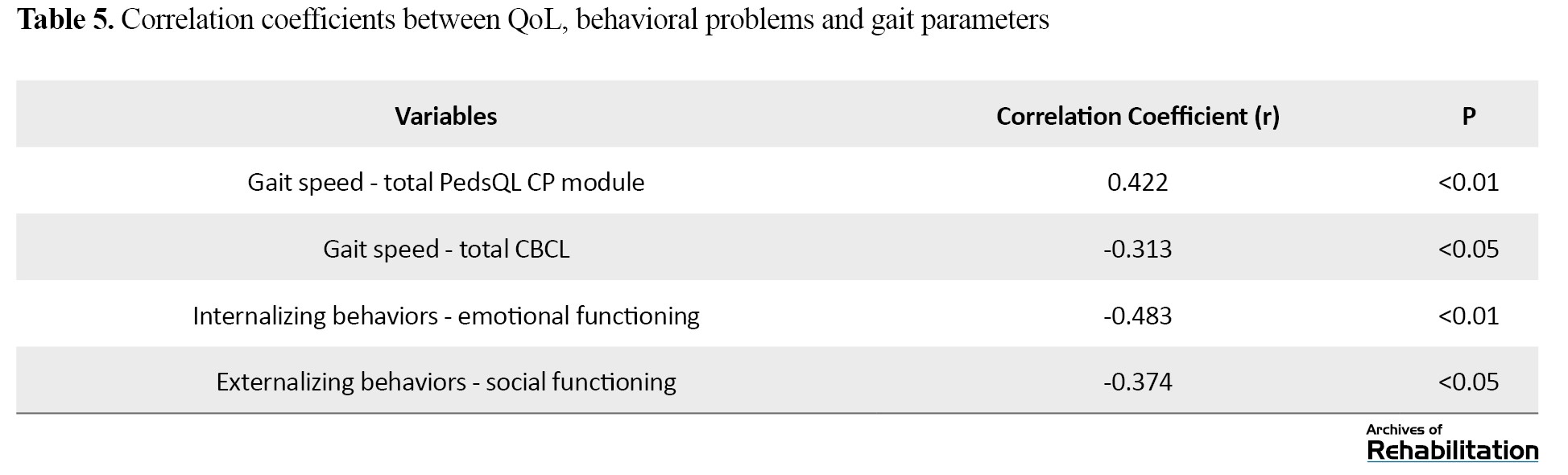

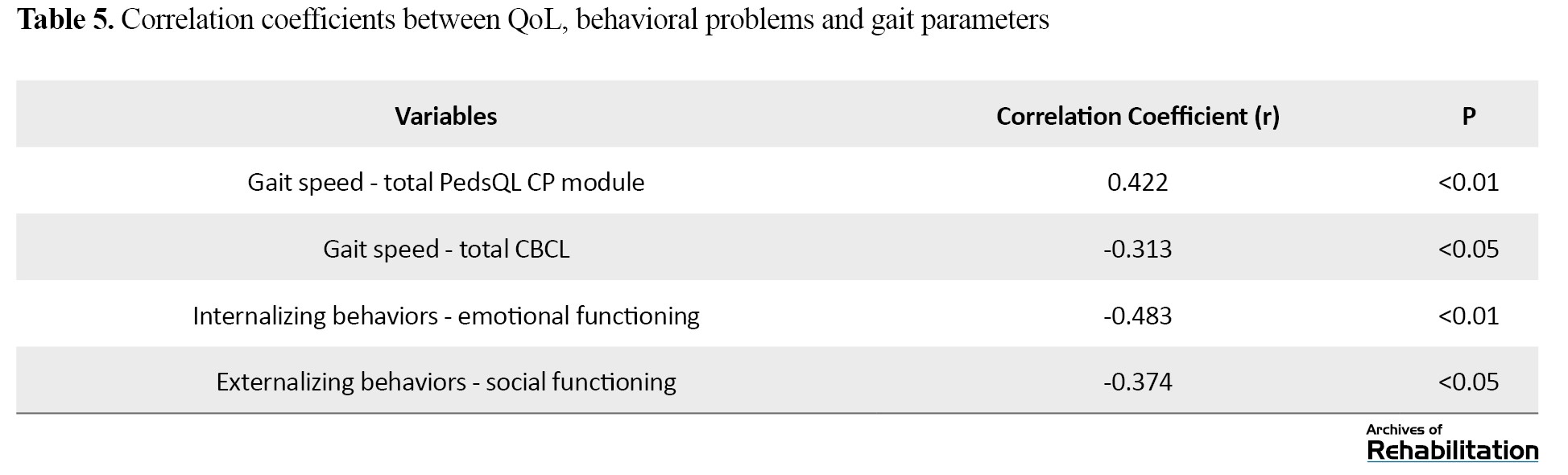

Gait speed showed a moderate significant positive correlation with the total PedsQL CP module score (r=0.422, P<0.01) and a weak significant negative relationship with the total CBCL score (r=-0.31, P<0.05). Internalizing behaviors domain of the CBCL had a significant negative association with emotional functioning domain of QoL (r=-0.483, P<0.01), whereas the externalizing behaviors domain had a significant negative association with the social functioning domain (r=-0.374, P<0.05), as detailed in Table 5.

Multiple linear regression coefficients revealed that gait speed (β=0.382, P<0.01) and internalizing behaviors (β=-0.454, P<0.01) were significant predictors of QoL. Together, they accounted for 52% of the variance in QoL (R²=0.52, P<0.001). The effect of externalizing behaviors was not significant (β=-0.221, P=0.06).

Discussion

This study investigated the complex relationships between gait parameters, QoL, and behavioral disorders in children with CP. The findings showed a significant association between motor disorders, behavioral problems, and overall QOL, emphasizing the multidimensional nature of CP and the interaction between physical and mental health.

The results confirmed that children with CP had poor gait parameters, including decreased speed, cadence, and stride length. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies that highlighted impaired gait mechanics in children with CP, especially those with severe motor disabilities [5, 25]. Other studies have also shown that spatiotemporal parameters of gait are significantly affected by the type and severity of CP, and that children with spastic CP have slower and less efficient gait patterns [26, 27]. Tehrani-Doost et al. reported that dyskinetic and ataxic CP is often associated with greater variability and instability in gait than spastic CP, leading to reduced functional mobility [24]. These results emphasize the importance of individualized gait interventions, tailored to the type of CP and severity of motor impairment, to optimize mobility and gait outcomes [28, 29].

The QoL scores of CP children in our study were low, with physical functioning being the most affected domain. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that children with CP experience a lower QoL compared to their healthy peers, particularly in the physical and social domains [30, 31]. Furthermore, the QoL scores differed significantly based on the GMFCS levels, with children at level I reporting better scores than those at levels II and III. This finding is supported by Dickinson et al.’s study, which showed that more severe movement disorder was associated with lower QoL, particularly in physical and social domains [13]. Gender differences in emotional functioning scores, with higher scores in girls, require further investigation, as they may reflect differences in coping strategies, emotional resilience, or access to social support networks [32, 33].

Behavioral disorders were significantly prevalent in CP children, with 35% having internalizing behaviors (such as anxiety and depression) and 28% having externalizing behaviors (such as aggression and ADHD). This is consistent with previous studies that identified high behavioral and emotional problems in children with CP [9-11]. Bhatnagar et al. found that children with CP were at higher risk for ADHD, anxiety, and depression, which can exacerbate the challenges caused by their physical disabilities [34]. A very significant finding of this study was the strong association between behavioral disorders and QoL, such that internalized behavior was found as a significant predictor of low QoL. These results are consistent with the findings of Williamson et al. who showed that behavioral problems, especially internalizing behaviors, are associated with lower QoL in children with CP [35]. Furthermore, we observed a significant relationship between gait speed and behavioral disorders, highlighting the need for comprehensive interventions that consider both mobility and behavioral health to improve the health-related QoL of CP children. Whittingham et al. also demonstrated a direct relationship between motor skills and behavioral problems in children with CP [36]. Our study provides new evidence supporting the integrated care model, where behavioral interventions can enhance the effectiveness of physical therapies in improving QoL in pediatric CP.

The findings of this study have important implications for both clinical practice and future research. The strong association of motor function and behavioral health with QoL highlights the need for multidisciplinary interventions that simultaneously focus on motor rehabilitation and behavioral therapies. Treatment programs for children with CP that incorporate cognitive-behavioral therapies in traditional walking exercises may provide better outcomes in terms of mobility, behavioral health, and QoL. Clinicians should consider individualized treatment plans based on the type and severity of CP, as children with dyskinetic and ataxic CP may require specialized gait interventions to address instability and variability. Also, given the significant prevalence of behavioral disorders in children with CP, routine mental health screenings should be included in comprehensive CP management protocols. Due to being a cross-sectional study, this research was unable to determine cause-and-effect relationships among the variables. To explore possible causal relationships, longitudinal cohort studies with follow-up assessments are needed. Although the sample size was sufficient, it was limited to children able to walk (GMFCS levels I–III). To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the reported associations, future research should expand the study population to include children unable to walk (GMFCS levels IV–V), who may face different behavioral and QoL-related challenges.

Behavioral problems were prevalent, with internalizing problems (e.g. anxiety, depression) strongly predicting poorer emotional well-being, consistent with Williamson et al. [35]. The mediating role of behavioral problems in the gait-QoL relationship emphasizes the need for integrated physical-psychological interventions [36].

Being a cross-sectional study, this research is unable to determine cause-and-effect relationships among the variables. To explore temporal links and possible causal pathways, longitudinal cohort studies with multiple follow-up assessments are needed. Furthermore, the participant group was restricted to ambulatory children classified as GMFCS levels I through III; incorporating non-ambulatory children at levels IV and V in future work would yield a more comprehensive understanding of the wider cerebral palsy population.

Conclusion

This study reveals the complex interaction between motor function, behavioral health, and QoL in CP children. It shows that poor gait and behavioral problems have a significant negative impact on the QoL of these children. Therefore, an integrated and multidisciplinary approach that targets both gait and behavioral problems at the same time is needed for CP children. Physical rehabilitation programs for these children should be complemented by targeted behavioral therapies to reduce the cascading effects of gait disturbances on their QOL. By adopting a holistic child-centered approach, clinicians can improve mobility, behaviors, and overall QoL of CP children.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.IMAMHOSPITAL.REC.1403.102).

Funding

This study was supported by the research project (No.: 23524), funded by the Mazndaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Cerebral palsy (CP) is the predominant childhood physical disability, with a global incidence rate of about 2–3 per 1,000 live births [1, 2]. This lifelong neuromotor condition results from non-progressive brain development disturbances during pregnancy or infancy, leading to persistent challenges in motor control and postural stability [3]. Key symptoms include muscle stiffness, reduced strength, and irregular coordination, often manifesting as visible gait abnormalities [4]. These gait abnormalities not only limit mobility but also reduce independence and the ability to perform daily activities [5]. The severity and presentation of gait disorders in children with CP vary widely, ranging from mild limping to complete inability to walk [6], influenced by factors such as CP type, disease severity, age, and treatment efficacy [7].

While motor impairments in CP are well-documented, their association with behavioral and emotional disorders has received less attention [8]. Children with CP are at higher risk of developing co-occurring behavioral disorders such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [9, 10], anxiety [11], depression, and emotional dysregulation [8]. These behavioral disorders are not simply secondary to neurological disorders; they are exacerbated by the environmental and social limitations caused by physical disability [3, 12]. Limited participation in educational, social, and recreational activities can lead to isolation, low self-esteem, and increased behavioral disorders [13]. The comorbidity of motor and psychological issues underscores the need for a comprehensive, multidisciplinary management approach to CP [14].

Quality of life (QoL), as one of the key indicators in evaluating the outcomes of pediatric rehabilitation, encompasses physical health, emotional well-being, social functioning, and psychological health [11, 12]. Evidence from multiple studies shows that children with CP generally have a lower QoL compared to their typically developing peers. This reduction is mainly due to physical limitations such as motor impairments, chronic pain, fatigue, and behavioral problems [15]. Mobility or gait plays a pivotal role in determining individual independence, participation in daily activities, and overall QoL [16]. Despite extensive CP research, most studies have separately examined domains such as gait biomechanics [5], epidemiology of behavioral disorders [17], and QoL determinants [18]. Few studies have explored the complex interaction between these domains [19, 20]. This research gap is concerning, considering that new approaches to care emphasize comprehensive, patient-centered methods. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the relationships between gait function, behavioral disorders, and QoL in children with CP. By analyzing these multidimensional interactions, the study seeks to provide deeper insights into QoL determinants in this population. The findings can be helpful for developing targeted multidisciplinary interventions integrating physical and psychological rehabilitation services, and ultimately improving functional outcomes and overall well-being of CP patients.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This is an observational cross-sectional study. The study population consists of children aged 6–12 years with a confirmed CP diagnosis, including spastic, dyskinetic, ataxic, or mixed subtypes in Mazandaran Province, Iran. The inclusion criteria were being at gross motor function classification system (GMFCS) levels of I, II, III, indicating independent or minimally assisted walking ability, having sufficient cognitive capacity to understand and follow instructions, and parental or guardian consent to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were severe cognitive impairment precluding participation, orthopedic surgery, or receiving botulinum toxin injections in the past six months, and concurrence of neurological or musculoskeletal disorders unrelated to CP. The participants were enrolled using a purposive sampling method from those referred to governmental and private rehabilitation clinics and special schools in Mazandaran Province. The sample size was determined at 60 using G*Power (effect size: 0.3, power: 80%, three predictors).

Assessments

Data collection began with demographic/clinical recording. Demographic/clinical data included age, sex, CP subtype, GMFCS level, and intervention history (e.g. medical treatment, physiotherapy, and use of assistive devices). The GMFCS was used for motor function classification. It is a standardized 5-level system that classifies children with CP based on self-initiated motor abilities (sitting, walking). We used the Persian version of this tool, which has already been validated [21]. The functional mobility scale (FMS) was used to evaluate mobility across 5-, 50-, and 500-meter distances on a 6-point scale from 1 (wheelchair dependence) to 6 (complete independence). This observational tool, completed by therapists or researchers, quantifies assistance levels required for mobility, providing an objective measure of functional gait ability. We used the Persian version of FMS, which has already been validated [22].

The children were then asked to walk at his/her desired speed along a 10-meter path and the relevant gait parameters were recorded. The pediatric quality of life inventory (PedsQL CP Module) was used to assess health-related QoL at physical, emotional, social, and school functioning domains. Both parent-proxy and child self-report versions were used for comprehensive QoL evaluation. We used the Persian version of this tool, which has already been validated [23]. The child behavior checklist (CBCL) was used for behavioral and emotional assessment. It is a common parent-report instrument that evaluates internalizing behaviors such as anxiety and depression, as well as externalizing behaviors including aggression and hyperactivity in children. We used the Persian version of this tool, which has already been validated [24]. Parents completed the CBCL and PedsQL CP module (parent-proxy), while children completed the PedsQL CP module (self-report).

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were conducted in SPSS software, version 27. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Descriptive statistics were first used to describe demographic characteristics, clinical features, and study outcomes. Continuous data were described using Mean±SD, while categorical data were expressed using frequencies and percentages. Spearman’s correlation test examined relationships between gait parameters, QoL scores, and behavioral scores. Multiple linear regression models identified the QoL predictors, considering gait parameters and behavioral scores as independent variables.

Results

Among 60 children with CP, 33 were male and 27 were female, with a mean age of 8.5±2.1 years. The majority were classified with spastic CP (78.3%), followed by dyskinetic (11.7%), ataxic (6.7%), and mixed (3.3%) subtypes. Regarding gross motor function, 45% of participants were at GMFCS level I, 35% at level II, and 20% at level III (Table 1).

As shown in Table 2, significant differences were observed in gait parameters among children based on the GMFCS level.

Gait speed decreased from 1.03 m/s in children at level I to 0.61 m/s in children at level III (P<0.05). The cadence decreased from 112.3 steps/min (level I) to 85.6 steps/min (Level III), and stride length declined from 1.05 m to 0.75 m from level I to II, both of which were statistically significant (P<0.05).

According to Table 3, the PedsQL CP module score indicated a moderate QoL with a total score of 68.4±12.3.

The domain-specific total scores were as follows: Physical functioning: 62.5±14.2, emotional functioning: 71.3±11.8, social functioning: 70.8±13.1, and school functioning: 69.1±12.5. The results reflected significantly lower QoL ratings compared to child self-report (P<0.05).

The results reported in Table 4 regarding the CBCL score based on the GMFCS level indicated a notable prevalence of behavioral problems in children with CP.

The mean total CBCL score was 58.7±9.4. Also, it was found that 35% of the children had internalizing behavioral problems such as anxiety and depression, while 28% exhibited externalizing behavioral problems, such as aggression and ADHD symptoms. Notably, the domain scores of the CBCL were significantly different among children based on the GMFCS level (P<0.05).

Gait speed showed a moderate significant positive correlation with the total PedsQL CP module score (r=0.422, P<0.01) and a weak significant negative relationship with the total CBCL score (r=-0.31, P<0.05). Internalizing behaviors domain of the CBCL had a significant negative association with emotional functioning domain of QoL (r=-0.483, P<0.01), whereas the externalizing behaviors domain had a significant negative association with the social functioning domain (r=-0.374, P<0.05), as detailed in Table 5.

Multiple linear regression coefficients revealed that gait speed (β=0.382, P<0.01) and internalizing behaviors (β=-0.454, P<0.01) were significant predictors of QoL. Together, they accounted for 52% of the variance in QoL (R²=0.52, P<0.001). The effect of externalizing behaviors was not significant (β=-0.221, P=0.06).

Discussion

This study investigated the complex relationships between gait parameters, QoL, and behavioral disorders in children with CP. The findings showed a significant association between motor disorders, behavioral problems, and overall QOL, emphasizing the multidimensional nature of CP and the interaction between physical and mental health.

The results confirmed that children with CP had poor gait parameters, including decreased speed, cadence, and stride length. These findings are consistent with the results of previous studies that highlighted impaired gait mechanics in children with CP, especially those with severe motor disabilities [5, 25]. Other studies have also shown that spatiotemporal parameters of gait are significantly affected by the type and severity of CP, and that children with spastic CP have slower and less efficient gait patterns [26, 27]. Tehrani-Doost et al. reported that dyskinetic and ataxic CP is often associated with greater variability and instability in gait than spastic CP, leading to reduced functional mobility [24]. These results emphasize the importance of individualized gait interventions, tailored to the type of CP and severity of motor impairment, to optimize mobility and gait outcomes [28, 29].

The QoL scores of CP children in our study were low, with physical functioning being the most affected domain. These results are consistent with previous studies showing that children with CP experience a lower QoL compared to their healthy peers, particularly in the physical and social domains [30, 31]. Furthermore, the QoL scores differed significantly based on the GMFCS levels, with children at level I reporting better scores than those at levels II and III. This finding is supported by Dickinson et al.’s study, which showed that more severe movement disorder was associated with lower QoL, particularly in physical and social domains [13]. Gender differences in emotional functioning scores, with higher scores in girls, require further investigation, as they may reflect differences in coping strategies, emotional resilience, or access to social support networks [32, 33].

Behavioral disorders were significantly prevalent in CP children, with 35% having internalizing behaviors (such as anxiety and depression) and 28% having externalizing behaviors (such as aggression and ADHD). This is consistent with previous studies that identified high behavioral and emotional problems in children with CP [9-11]. Bhatnagar et al. found that children with CP were at higher risk for ADHD, anxiety, and depression, which can exacerbate the challenges caused by their physical disabilities [34]. A very significant finding of this study was the strong association between behavioral disorders and QoL, such that internalized behavior was found as a significant predictor of low QoL. These results are consistent with the findings of Williamson et al. who showed that behavioral problems, especially internalizing behaviors, are associated with lower QoL in children with CP [35]. Furthermore, we observed a significant relationship between gait speed and behavioral disorders, highlighting the need for comprehensive interventions that consider both mobility and behavioral health to improve the health-related QoL of CP children. Whittingham et al. also demonstrated a direct relationship between motor skills and behavioral problems in children with CP [36]. Our study provides new evidence supporting the integrated care model, where behavioral interventions can enhance the effectiveness of physical therapies in improving QoL in pediatric CP.

The findings of this study have important implications for both clinical practice and future research. The strong association of motor function and behavioral health with QoL highlights the need for multidisciplinary interventions that simultaneously focus on motor rehabilitation and behavioral therapies. Treatment programs for children with CP that incorporate cognitive-behavioral therapies in traditional walking exercises may provide better outcomes in terms of mobility, behavioral health, and QoL. Clinicians should consider individualized treatment plans based on the type and severity of CP, as children with dyskinetic and ataxic CP may require specialized gait interventions to address instability and variability. Also, given the significant prevalence of behavioral disorders in children with CP, routine mental health screenings should be included in comprehensive CP management protocols. Due to being a cross-sectional study, this research was unable to determine cause-and-effect relationships among the variables. To explore possible causal relationships, longitudinal cohort studies with follow-up assessments are needed. Although the sample size was sufficient, it was limited to children able to walk (GMFCS levels I–III). To gain a more comprehensive understanding of the reported associations, future research should expand the study population to include children unable to walk (GMFCS levels IV–V), who may face different behavioral and QoL-related challenges.

Behavioral problems were prevalent, with internalizing problems (e.g. anxiety, depression) strongly predicting poorer emotional well-being, consistent with Williamson et al. [35]. The mediating role of behavioral problems in the gait-QoL relationship emphasizes the need for integrated physical-psychological interventions [36].

Being a cross-sectional study, this research is unable to determine cause-and-effect relationships among the variables. To explore temporal links and possible causal pathways, longitudinal cohort studies with multiple follow-up assessments are needed. Furthermore, the participant group was restricted to ambulatory children classified as GMFCS levels I through III; incorporating non-ambulatory children at levels IV and V in future work would yield a more comprehensive understanding of the wider cerebral palsy population.

Conclusion

This study reveals the complex interaction between motor function, behavioral health, and QoL in CP children. It shows that poor gait and behavioral problems have a significant negative impact on the QoL of these children. Therefore, an integrated and multidisciplinary approach that targets both gait and behavioral problems at the same time is needed for CP children. Physical rehabilitation programs for these children should be complemented by targeted behavioral therapies to reduce the cascading effects of gait disturbances on their QOL. By adopting a holistic child-centered approach, clinicians can improve mobility, behaviors, and overall QoL of CP children.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran (Code: IR.MAZUMS.IMAMHOSPITAL.REC.1403.102).

Funding

This study was supported by the research project (No.: 23524), funded by the Mazndaran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interception of the results and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- McIntyre S, Goldsmith S, Webb A, Ehlinger V, Hollung SJ, McConnell K, et al. Global prevalence of cerebral palsy: A systematic analysis. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2022; 64(12):1494-506. [DOI:10.1111/dmcn.15346] [PMID]

- Abate BB, Tegegne KM, Zemariam AB, Wondmagegn Alamaw A, Kassa MA, Kitaw TA, et al. Magnitude and clinical characteristics of cerebral palsy among children in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plos Global Public Health. 2024; 4(6):e0003003. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pgph.0003003] [PMID]

- Patel DR, Bovid KM, Rausch R, Ergun-Longmire B, Goetting M, Merrick J. Cerebral palsy in children: A clinical practice review. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 2024; 54(11):101673. [DOI:10.1016/j.CPpeds.2024.101673] [PMID]

- Himmelmann K, Panteliadis CP. Clinical Characteristics of Cerebral Palsy. In: Himmelmann K, Panteliadis CP, editors. Cerebral palsy: From childhood to adulthood. London: Springer; 2025. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-031-71571-6_12]

- Gravholt A, Fernandez B, Bessaguet H, Millet GY, Buizer AI, Lapole T. Motor function and gait decline in individuals with cerebral palsy during adulthood: A narrative review of potential physiological determinants. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 2024; 124(10):2867-79. [DOI:10.1007/s00421-024-05550-y] [PMID]

- Sheu J, Cohen D, Sousa T, Pham KL. Cerebral palsy: current concepts and practices in musculoskeletal care. Pediatrics in Review. 2022; 43(10):572-81. [DOI:10.1542/pir.2022-005657] [PMID]

- Mashabi A, Abdallat R, Alghamdi MS, Al-Amri M. Gait compensation among children with non-operative legg-calvé-perthes disease: A systematic review. Healthcare. 2024; 12(9):895. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare12090895] [PMID]

- Honan I, Waight E, Bratel J, Given F, Badawi N, McIntyre S, et al. Emotion regulation is associated with anxiety, depression and stress in adults with cerebral palsy. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2023; 12(7):2527. [DOI:10.3390/jcm12072527] [PMID]

- Casseus M, Cheng J, Reichman NE. Clinical and functional characteristics of children and young adults with cerebral palsy and co-occurring attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2024; 151:104787. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2024.104787] [PMID]

- Zaman M, Behlim T, Ng P, Dorais M, Shevell MI, Oskoui M. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children with cerebral palsy: A case-control study. Neurology. 2025; 104(6):e213425. [DOI:10.1212/wnl.0000000000213425] [PMID]

- Sarman A, Tuncay S, Budak Y, Demirpolat E, Bulut İ. Anxiety, depression, and support needs of the mothers of children with cerebral palsy and determining their opinions: Mixed methods study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2024; 78:e133-e40. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2024.06.028] [PMID]

- Rok-Bujko P, Kawecka J. Psychological and functional problems of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy from the neurodevelopmental perspective. Pediatria Polska-Polish Journal of Paediatrics. 2023; 98(2):145-53. [DOI:10.5114/polp.2023.128854]

- Sañudo B, Sánchez-Oliver AJ, Fernández-Gavira J, Gaser D, Stöcker N, Peralta M, et al. Physical and psychosocial benefits of sports participation among children and adolescents with chronic diseases: A systematic review. Sports Medicine-Open. 2024; 10(1):54. [DOI:10.1186/s40798-024-00722-8] [PMID]

- Biswal R, Mishra C. Addressing the Psychological Barriers Towards an Inclusive Society for the Persons with Disabilities (PwDs). In: Biswas UN, Narayan Biswas S, editors. Building a resilient and responsible world: Psychological perspectives from India. London: Springer; 2025. [DOI:10.1007/978-981-96-0108-0_6]

- Tedla JS, Sangadala DR, Asiri F, Alshahrani MS, Alkhamis BA, Reddy RS, et al. Quality of life among children with cerebral palsy in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and various factors influencing it: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Disability Research. 2024; 3(4):20240050. [DOI:10.57197/jdr-2024-0050]

- Ahmeti ZG, Bıyık KS, Günel M, Yazıcıoğlu FG. Relation between balance, functional mobility, walking endurance and participation in ambulatory children with spastic bilateral cerebral palsy-Balance and participation in cerebral palsy. Journal of Exercise Therapy and Rehabilitation. 2024; 11(2):132-41. [DOI:10.15437/jetr.1292901]

- Freitas PM, Haase VG. Behavioral Disorders in Unilateral and Bilateral Cerebral Palsy: A Comparative Study. International Journal of Psychiatry Research. 2024; 7(5):1-6. [DOI:10.33425/2641-4317.1208]

- Badgujar S, Dixit J, Kuril BM, Deshmukh LS, Khaire P, Vaidya V, et al. Epidemiological predictors of quality of life and the role of early markers in children with cerebral palsy: A multi-centric cross-sectional study. Pediatrics and Neonatology. 2025; 66(1):18-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedneo.2024.04.003] [PMID]

- Mosser N, Norcliffe G, Kruse A. The impact of cycling on the physical and mental health, and quality of life of people with disabilities: A scoping review. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living. 2025; 6:1487117. [DOI:10.3389/fspor.2024.1487117] [PMID]

- Alanazi AH, Alanazi AM, Alenazi AS, Alanazi AM, Alruwaili AA, Alabdali SS, et al. Improving quality of life for patients with cerebral palsy: Evidence-based nursing strategies. Journal of International Crisis and Risk Communication Research. 2024; 7(S8):2292. [DOI:10.63278/jicrcr.vi.1226]

- Dehghan L, Abdolvahab M, Bagheri H, Dalvand H, Faghih Zade SF. [Inter rater reliability of Persian version of gross motor function classification system expanded and revised in patients with cerebral palsy (Persian)]. Daneshvar Medicine. 2020; 18(6):37-44. [Link]

- Sadeghian Afarani R, Fatorehchy S, Rassafiani M, Vahedi M, Azadi H, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the persian version of the functional mobility scale: Assessing validity and reliability. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2024; 44(5):721-32. [DOI:10.1080/01942638.2024.2314489] [PMID]

- Amiri P, Eslamian G, Mirmiran P, Shiva N, Jafarabadi MA, Azizi F. Validity and reliability of the Iranian version of the pediatric quality of life inventory™ 4.0 (PedsQL™) generic core scales in children. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2012; 10:3. [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-10-3] [PMID]

- Tehrani-Doost M, Shahrivar Z, Pakbaz B, Rezaie A, Ahmadi F. Normative data and psychometric properties of the child behavior checklist and teacher rating form in an Iranian community sample. Iranian Journal of Pediatrics. 2011; 21(3):331. [DOI:10.18502/ijps.v15i2.2686]

- Tabard-Fougère A, Rutz D, Pouliot-Laforte A, De Coulon G, Newman CJ, Armand S, et al. Are clinical impairments related to kinematic gait variability in children and young adults with cerebral palsy? Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2022; 16:816088. [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2022.816088] [PMID]

- Corsi C, Santos MM, Moreira RFC, Dos Santos AN, de Campos AC, Galli M, et al. Effect of physical therapy interventions on spatiotemporal gait parameters in children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2021; 43(11):1507-16. [DOI:10.1080/09638288.2019.1671500] [PMID]

- OuYang Z, Shen C, Wang Y. Motion analysis for the evaluation of dynamic spasticity during walking: A systematic scoping review. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders. 2025; 94:106273. [DOI:10.1016/j.msard.2025.106273] [PMID]

- Bekteshi S, Monbaliu E, McIntyre S, Saloojee G, Hilberink SR, Tatishvili N, et al. Towards functional improvement of motor disorders associated with cerebral palsy. The Lancet. Neurology. 2023; 22(3):229-43. [DOI:10.1016/s1474-4422(23)00004-2] [PMID]

- Bogaert A, Romanò F, Cabaraux P, Feys P, Moumdjian L. Assessment and tailored physical rehabilitation approaches in persons with cerebellar impairments targeting mobility and walking according to the International Classification of Functioning: a systematic review of case-reports and case-series. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2024; 46(16):3490-512. [DOI:10.1080/09638288.2023.2248886] [PMID]

- Di Lieto MC, Matteucci E, Martinelli A, Beani E, Menici V, Martini G, et al. Impact of social participation, motor, and cognitive functioning on quality of life in children with Cerebral Palsy. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2025; 161:105004. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2025.105004] [PMID]

- Aza A, Riquelme I, Vela MG, Badia M. Proxy-and self-report evaluation of quality of life in cerebral palsy: Using Spanish version of CPQOL for Children and adolescents. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2024; 154:104844. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2024.104844] [PMID]

- Ruetti E, Pirotti S. Emotional burden of care in mothers of children with cerebral palsy: functional dependency, emotional intelligence, and coping strategies. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2024; 72(4):737-52. [DOI:10.1080/1034912x.2024.2355345]

- Moriwaki M, Yuasa H, Kakehashi M, Suzuki H, Kobayashi Y. Impact of social support for mothers as caregivers of cerebral palsy children in Japan. Journal of pediatric Nursing. 2022; 63:e64-71. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2021.10.010] [PMID]

- Bhatnagar S, Mitelpunkt A, Rizzo JJ, Zhang N, Guzman T, Schuetter R, et al. Mental health diagnoses risk among children and young adults with cerebral palsy, chronic conditions, or typical development. JAMA Network Open. 2024; 7(7):e2422202-e. [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.22202] [PMID]

- Williamson AA, Zendarski N, Lange K, Quach J, Molloy C, Clifford SA, et al. Sleep problems, internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and domains of health-related quality of life: bidirectional associations from early childhood to early adolescence. Sleep. 2021; 44(1):zsaa139. [DOI:10.1093/sleep/zsaa139] [PMID]

- Whittingham K, Sanders M, McKinlay L, Boyd RN. Interventions to reduce behavioral problems in children with cerebral palsy: An RCT. Pediatrics. 2014; 133(5):e1249-57. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2013-3620] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 26/04/2025 | Accepted: 6/08/2025 | Published: 1/10/2025

Received: 26/04/2025 | Accepted: 6/08/2025 | Published: 1/10/2025

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |