Volume 26, Issue 3 (Autumn 2025)

jrehab 2025, 26(3): 398-421 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abbasi Asl M, Khanjani M S, Foroughan M, Azkhosh M, Moloodi R. Psychological Challenges of Family Caregivers of Older Adults With Dependency in Activities of Daily Living in Iran: A Qualitative Study. jrehab 2025; 26 (3) :398-421

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3619-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3619-en.html

Mojtaba Abbasi Asl1

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani *2

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani *2

, Mahshid Foroughan3

, Mahshid Foroughan3

, Manouchehr Azkhosh1

, Manouchehr Azkhosh1

, Reza Moloodi4

, Reza Moloodi4

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani *2

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani *2

, Mahshid Foroughan3

, Mahshid Foroughan3

, Manouchehr Azkhosh1

, Manouchehr Azkhosh1

, Reza Moloodi4

, Reza Moloodi4

1- Department of Counseling, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,sa.khanjani@uswr.ac.ir

3- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Cognition and Behavior Counseling and Psychological Services Center, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Iranian Research Center on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Cognition and Behavior Counseling and Psychological Services Center, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1891 kb]

(244 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1158 Views)

Full-Text: (284 Views)

Introduction

With the advancement of healthcare, preventive measures, and control of infectious diseases, the average human lifespan has increased, resulting in a significant rise in the aged population in both developed and developing countries [1]. According to the United Nations report, the global aged population was approximately 1.1 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach 1.2 billion by 2050. More than 80% of this population will live in low- and middle-income countries [2]. Similar to many countries, the aged population in Iran is increasing at a rate even higher than the global average, such that in 2022, the number of individuals over 60 years old exceeded 10% of the total population [3]. In old age, chronic physical and mental illnesses and cognitive and functional impairments increase [4], and thus the need for care services, especially long-term care, rises [5]. The older adults who are unable to perform their activities of daily living (ADLs) are at greater risk [6]. ADL refers to any task that an individual normally performs for self-care at home, outside the house, or both (such as toileting, eating, dressing, and undressing) [7]. Impairment in performing these activities leads to increased dependency and increases the risk of hospitalization in nursing homes or receiving full-time family care [8].

In developing countries, family caregiving plays a vital role in the care of disabled older adults. According to statistics, 80% of older adults requiring care are supervised by one of their family members [9]. In family caregiving, older adults require essential support due to their inability to perform ADLs. In these circumstances, relatives act as caregivers and provide care without receiving any compensation from the older adults [10]. Families play a central role in caring for vulnerable older adults. Approximately 80% of this care is provided at home by family caregivers, while less than 20% of the older adults receive formal care [11].

Despite the cost-effectiveness and efficacy of family caregiving, excessive reliance on families may have negative impacts on family members and on the physical, psychological, and social health of family caregivers [12]. Family caregiving is considered a challenging task and may lead to psychological and social problems among family caregivers [13]. Research has shown that family caregivers are more exposed to depression, stress, and caregiver burnout. These problems are primarily exacerbated by insufficient support and neglect of caregivers’ needs [14, 15]. Collins et al. [16] showed that 31% of family caregivers of older adults suffer from depressive symptoms and nearly 50% experience caregiver burden; when considering only female family caregivers, the prevalence of depression rises to almost 47%. Another study indicated that 32% of family caregivers of older adults struggle with anxiety [17]. Family caregivers of older adults face psychological challenges. Identifying these challenges and providing appropriate support can improve both the caregivers’ quality of life and that of the older adults they care for [18].

Studies conducted in various countries have examined the general challenges faced by family caregivers of older adults. For instance, Shuffler et al. [19] extracted the challenges experienced by family caregivers, and Akgun-Citak et al. [18] identified various challenges of this group. However, fewer studies have specifically focused on their psychological challenges, even though family caregivers face specific psychological issues such as a lack of social support, feeling guilty due to the inability to meet all the needs of older adults, lack of anger control towards older adults, and experiencing exclusion from important decision-making processes [20]. Most previous studies have not considered how dependent the older adults are on their caregivers. Therefore, the present study focuses on caregivers of older adults who are semi-dependent in performing ADLs, as this level of dependency may influence the type and intensity of psychological stress experienced by caregivers. It is also important to note that in studies on family caregiving, ethnic and cultural factors play a significant role [21]. Iranian family culture differs from that of other countries in several respects. It mostly follows the norms of the traditional family model [22], where a sense of duty toward older adults, along with kindness and respect, is highly valued [23]. However, to our knowledge, no study has specifically identified or explored the psychological challenges faced by Iranian family caregivers of older adults.

Considering the growth in the number of older adults, the crucial role of family caregivers, and the connection of family caregiving to the economic and social conditions, norms, and values of Iranian society, identifying the psychological challenges of family caregivers in Iran is essential for designing effective interventions to improve caregivers’ mental health. Therefore, the present research aims to identify the psychological challenges of the family caregivers of older adults with dependency in performing ADLs in Iran.

Materials and Methods

This is a qualitative research employing a conventional content analysis approach. This method is usually used when the body of literature on a given phenomenon is scarce [24]. The research was conducted between July 2023 and March 2024. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling method from family caregivers of older adults who attended the second branch of the Kahrizak Day Rehabilitation Center and the Zarman Comprehensive Rehabilitation Center, located in Alborz Province. Sampling continued until data saturation was reached. The selection of these two centers was due to their extensive services for older adults and the opportunity to access family caregivers with maximum social and economic diversity. Purposive sampling was used because the purpose of this method was to select individuals who are rich sources of information and can actively participate in the study, enabling the researcher to gain a deeper understanding of their experiences [25]. Inclusion criteria were: Being a family member who provides care for an older adult for at least four hours per day [26], providing care for more than six months, not receiving any payment for caregiving, age at least 18 years, and informed consent to participate in the study. To assess the older adults’ basic ADLs, the Barthel index [27] was used. This index consists of 10 items, scored on a scale from 0 to 2, indicating the level of independence or dependence in performing ADLs, with a total score ranging from 0 to 20; a score of 20 represents total independence, 13–19 moderate dependency, 9–12 severe dependency, and 0–8 total dependency [27]. The minimum score required to determine the older adult’s dependency level in our study was 9 (severe dependency).

The participants’ experiences were surveyed using semi-structured interviews. A total of 14 interviews were conducted with family caregivers of older adults, after providing an explanation of the research objectives to them. All interviews were recorded with their consent. Interview questions primarily focused on the psychological challenges of family caregivers during the caregiving period for older adults. The interview process began with a few general open-ended questions, e.g. “How has caring for an older adult changed your life?” or “What challenges has caregiving created for you?”. Then, based on the responses, more specific questions were asked to obtain deeper data. Each interview lasted for 30-60 minutes.

Data analysis was performed in MAXQDA software, version 2020, according to the steps proposed by Graneheim and Lundman [24]. The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were read several times to gain a general understanding of the content. Then, the transcribed text was carefully divided into condensed meaning units. In the third step, each sentence or paragraph was coded. Subsequently, the initial codes were compared, and similar codes were grouped into subcategories. In the final step, by continuously comparing subcategories based on similarities and differences, the main themes were extracted. To reduce the number of categories, this process was repeated several times until the main themes and sub-themes were obtained.

This study considered Lincoln and Guba’s four criteria for enhancing the trustworthiness and rigor of the research [28]. To increase credibility, the transcripts and the extracted codes were reviewed and validated by a research team including experts in psychology, counseling, and gerontology. Additionally, the codes were shared with three participants to ensure their alignment with the experiences they had described. Dependability was determined through prolonged engagement of the researcher with participants and the research topic, and holding multiple meetings with the research team to maintain a consistent framework for data collection and analysis. For confirmability, all stages of the research, including data collection, data analysis, and category development, were described in detail. To determine the transferability of the findings, purposeful efforts were made to ensure diversity in the samples by selecting participants with different socioeconomic statuses, different relationships with the older adult, different educational backgrounds, and different employment statuses.

Results

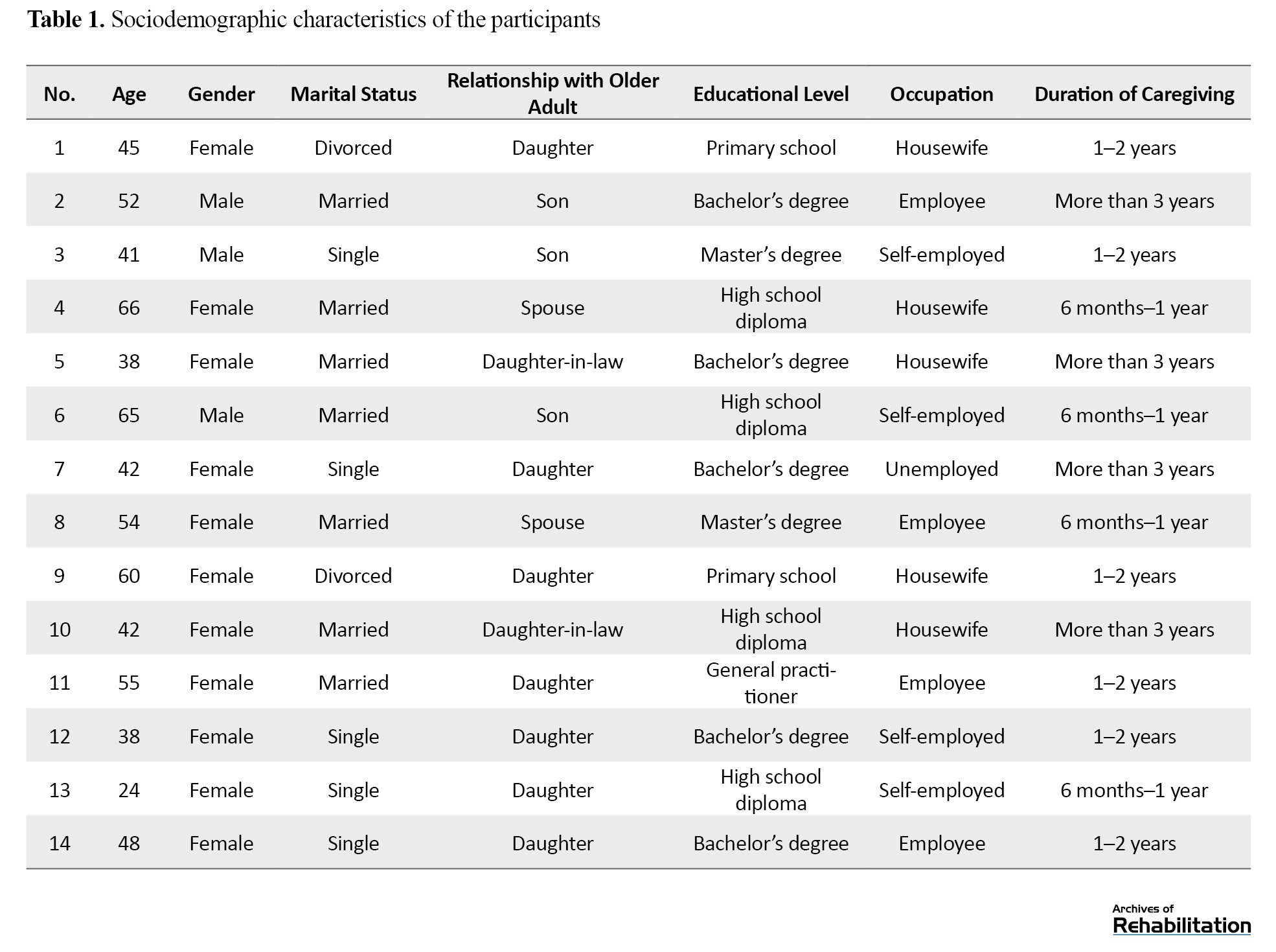

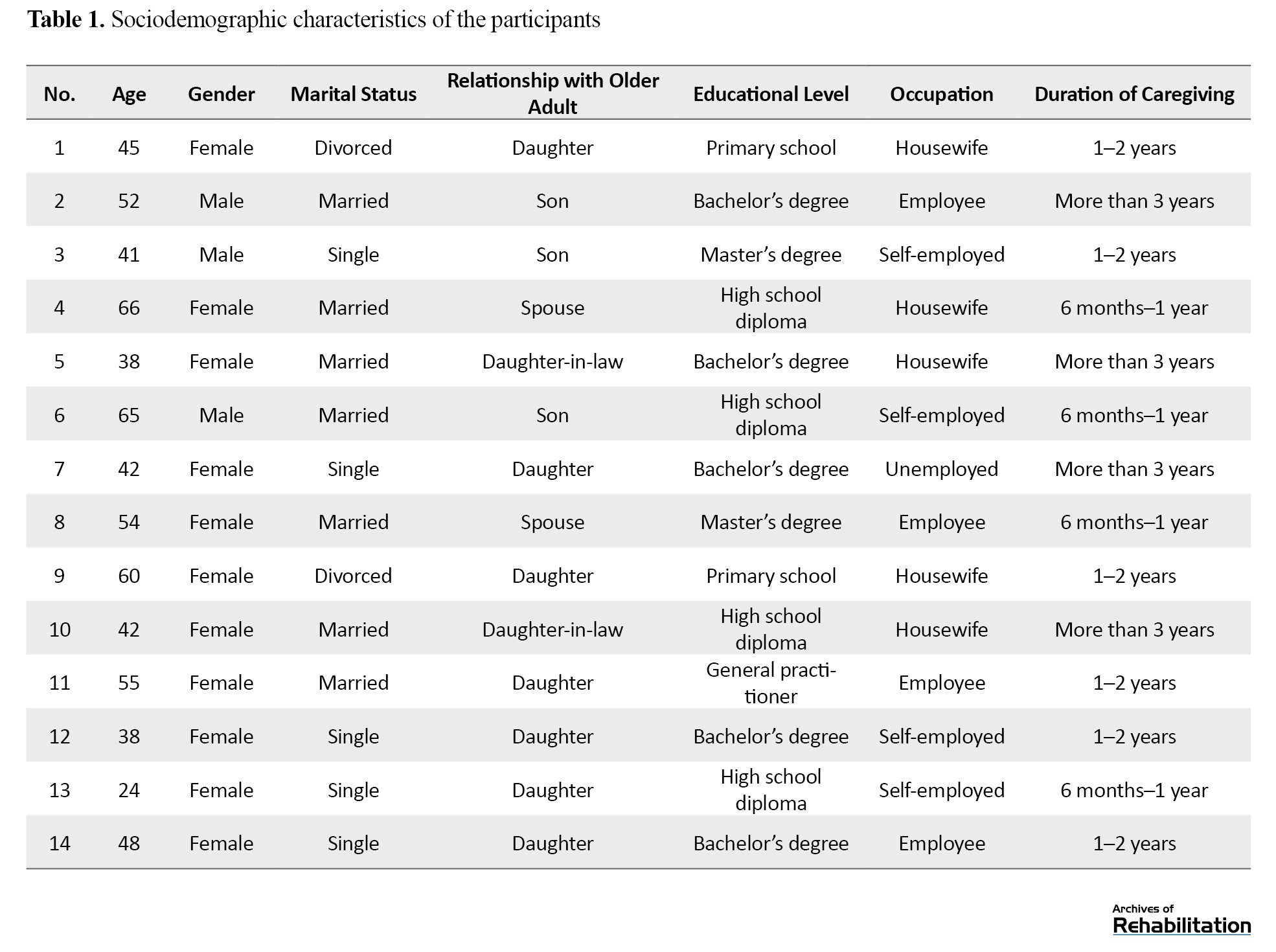

The participants were 14 family caregivers of older adults. The ages of older adults under care ranged from 66 to 87 years. Eleven (78.5%) of family caregivers were women, and three (21.4%) were men. The age range of the caregivers was 24-66 years (Mean age: 47.8 years). Seven caregivers (50.0%) were married, five (35.7%) were single, and two (14.2%) were divorced. Other sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

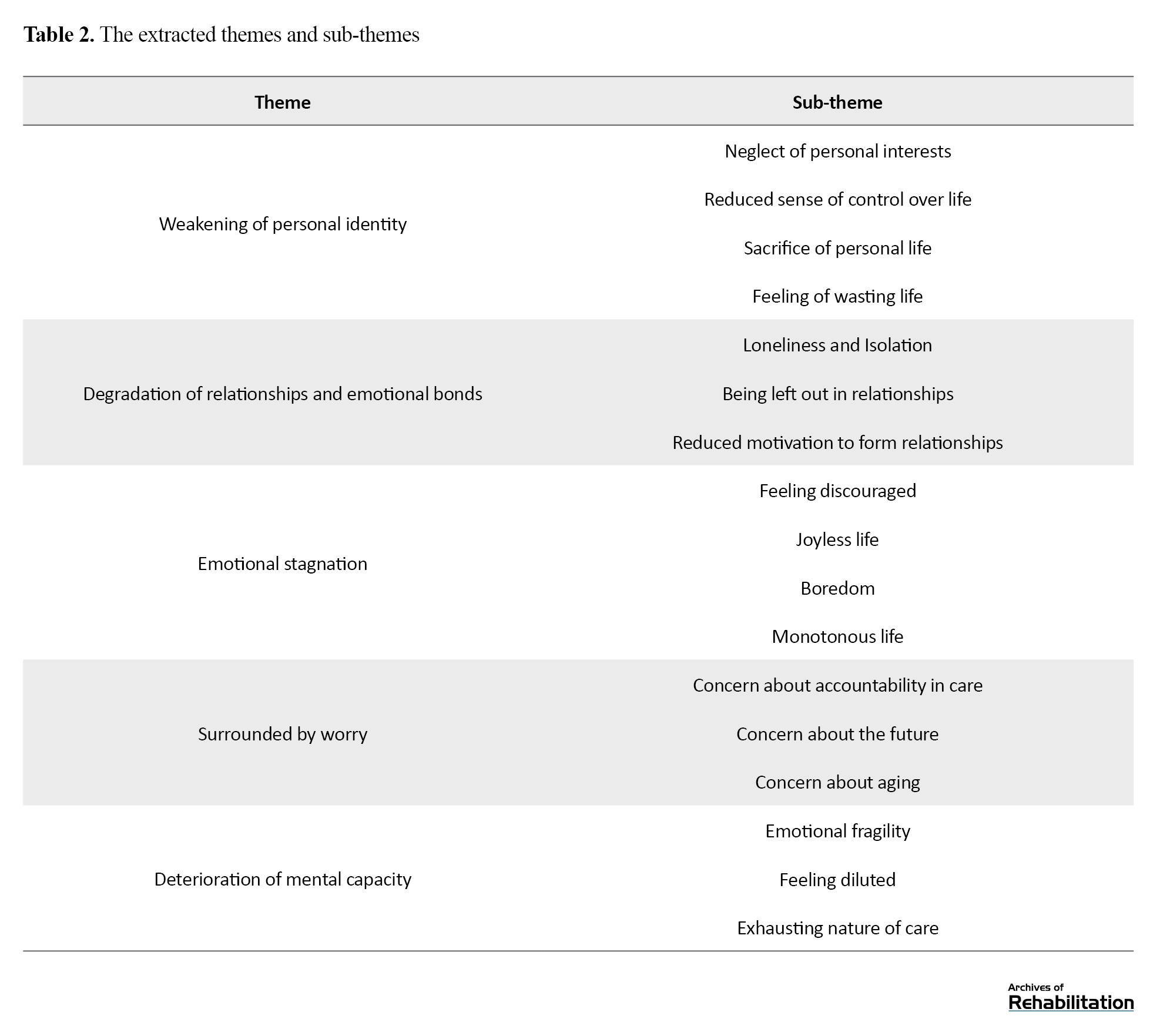

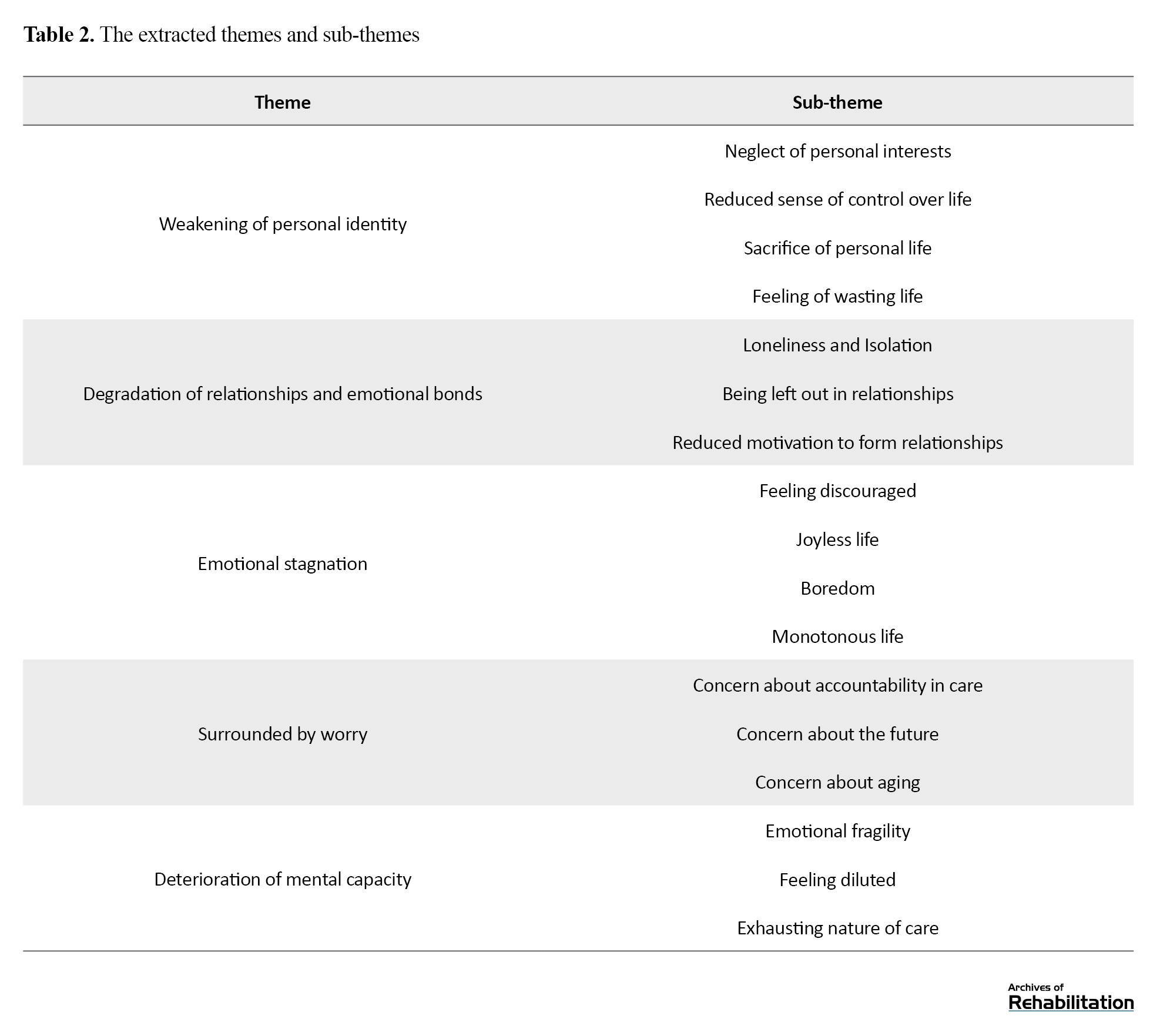

A total of 183 codes were extracted in the first stage of data analysis. These codes were categorized into 17 subcategories and five main categories, reflecting the psychological needs of family caregivers of older adults in Iran (Table 2).

Weakening of personal identity

The first theme was “Weakening of personal identity”. This theme consisted of four sub-themes: Neglect of personal interests, reduced sense of control over life, sacrifice of personal life, and feeling of wasting life.

Neglect of personal interest

Due to the heavy burden of caregiving responsibilities, family caregivers usually have little time to pursue their own interests and personal activities. Neglect of personal interests is a significant challenge in the daily lives of caregivers, as they often prioritize caring for the older adult over their own needs. “Sometimes I think of starting to learn a skill, a sport, or an instrument that I have wanted to learn for years, but because of my caregiving responsibilities and lack of time, I cannot go after it” (Participant No. (P.) 12).

Reduced sense of control over life

In many cases, family caregivers perceive themselves as surrounded by a set of responsibilities that deprive them of the freedom to change direction or pursue alternative paths. In such situations, decision-making about personal life becomes heavily influenced by external demands. Over time, this dynamic can create a sense of being trapped on an unchangeable path that should be endured. Consequently, caregivers may feel that they have lost control over their own lives, perceiving each decision as merely a response to pressures and circumstances imposed upon them.”I feel that I have no control over my future and life, and that there is an obligation to follow a certain path; it’s not up to me to decide what to do” (P.11).

Sacrifice of personal life

Forgetting about personal goals and plans is one of the main challenges for family caregivers. They sometimes feel that their personal lives are sacrificed for the needs of others. This means that in fulfilling caregiving responsibilities, they give up their goals, plans, and desires. In such a situation, a caregiver may perceive themselves as a means used solely for carrying other people. “I feel like I don’t live for myself! I spend my time either taking care of my mother or looking after my kids. I have to forget my own needs, I can’t do anything just for my own benefit anymore” (P.14).

Feeling of wasting life

Sometimes, family caregivers become so involved in the caregiving role that they are forced to leave their favorite jobs and perceive that the efforts they put into their careers in the past are no longer useful or beneficial. They may feel that, although they have been able to help others, they have not been able to reap the benefits of these efforts for themselves, leading to a sense that their time and life have been wasted. “I spent many years to study, and when my children were little, I had to leave them with their grandmothers to work! Now, I can’t benefit from these efforts. They are no longer useful, and I feel like I’ve wasted my life” (P.11).

Degradation of relationships and emotional bonds

The theme “Degradation of relationships and emotional bonds” included three sub-themes: Loneliness/isolation, being left out in relationships, and reduced motivation to form relationships.

Loneliness/isolation

Spending time caring for an older adult gradually leads to a reduction in the caregiver’s social relationships. Caregivers may find themselves in a limited circle of relationships, losing the ability to engage in intimate social relationships they previously enjoyed, which, in addition to damaging interpersonal relationships, can contribute to an emotional void in the caregiver’s personal life, causing the person to experience deep feelings of loneliness and isolation in the long term. “The caregiving role pushes a person towards loneliness. My social relationships have greatly declined. I used to spend more time with relatives and friends, but it has now been greatly reduced. Previously, I could see my friends every day, but now I can barely see them, maybe once a week” (P.3).

Being left out in relationships

In some cases, family caregivers observed that friends and relatives gradually distance themselves from them, and past relationships lose their former form. This is not necessarily the result of a conscious decision by others; rather, it can be due to a change in the interaction space and the caregiver’s mood, or a feeling of unfamiliarity among the caregivers and people around them. Over time, such changes can lead to fewer invitations, visits, and social interactions, causing the caregiver to feel that they no longer have the same place in their social network as before. “I used to go out with my friends. I was very close to my cousins; we had parties every week and we visited each other frequently, but now, when they visit us, my mother-in-law [the older adult] keeps talking to them and interrupting us, ruining our relationship, and doesn’t let them enjoy their time. I see that they are indirectly refusing to come to our house” (P.5).

Reduced motivation to form relationships

Some family caregivers gradually lost their motivation and desire to establish new relationships or maintain previous relationships. In such situations, even interactions that were previously valued may lose their appeal. This change can be accompanied by a sense of indifference, which prevents the individual from making efforts to maintain or form new relationships. “I feel numb and indifferent toward people. It doesn’t really matter whether my relationships are shattered or not. I have very little desire to socialize. I even spend my free time alone. I don’t have hope that a new relationship could be good for me” (P.12).

Emotional stagnation

The theme “Emotional stagnation” consists of four sub-themes: Feeling discouraged, joyless life, boredom, and monotonous life.

Feeling discouraged

When family caregivers are placed in situations for a long time where their emotional and psychological support resources are depleted, they may lose their courage and desire to pursue personal goals and preferred activities. This condition not only manifests as a reduced inclination to engage in pleasurable activities but can also lead to a sense of numbness and indifference toward the future. In this state, the individual is also unable to regain lost courage even when the conditions are met. “Even if I had the time, I would no longer have the motivation to go after the things I wanted in life. I don’t have the courage to do them anymore, it’s a sign of depression, I guess. I feel discouraged” (P.12).

Joyless life

Some family caregivers reported facing the challenge of living a life devoid of joy. This situation becomes particularly evident when daily responsibilities and caregiving duties leave little opportunity to pursue personal interests or engage in enjoyable activities. In such circumstances, caregivers may feel that life has lost its appeal and that neither activities nor social interactions bring satisfaction. “Nothing is enjoyable anymore! My life has become something I never wanted it to be. All I do is stay at home and take care of someone, which doesn’t make me feel better. I don’t enjoy anything in life” (P.13).

Boredom

Most family caregivers experienced boredom, especially when caregiving pressures continue chronically and over a long period. When an individual is continuously engaged in caregiving role, their energy and capacity to perform or even enjoy everyday activities naturally decline. This boredom can affect all aspects of life, causing the individual to withdraw from personal activities or social relationships. “I’m bored to do my work, interact with someone, do house chores, or do knitting. I don’t have the patience to cook the food I want or do something for myself” (P.9).

Monotonous life

A sense of monotony in life was one of the common experiences among caregivers, particularly when caring for an older adult becomes a daily repetitive job due to the lack of variety and change in daily activities. As a result, life turns into a routine and a cycle without diversity, where the person is unable to experience excitement or positive changes in their life. “Sometimes I feel like everything has become so repetitive, as if I was a robot programmed to wake up in the morning and do specific tasks at specific times. When a person does something monotonously, after a while, they like to change their schedule or timing. Nobody wants a monotonous life” (P.10).

Surrounded by worry

The theme “Surrounded by worry” included three sub-themes: Concerns about accountability in care, concerns about the future, and concerns about aging.

Concern about accountability in care

Concern about caregiving responsibilities was one of the major psychological challenges that some family caregivers faced. These concerns arise due to the fear of negative judgments by others, who may perceive the caregiver as incompetent or indifferent. The responsibility of caring for an older adult is accompanied by a fear that any mistake or negligence may lead to criticism or blame from others. This perception makes the caregivers constantly remind themselves to perform their duties in the best possible way in order to reduce the concerns about accountability in care. “If the old adult got sick, I would be responsible; I should be accountable. Everyone is watching me [ready to blame me]. These really make a person nervous; oh my God, if something bad happens, I have to answer to everyone’” (P.1).

Concerns about the future

When family caregivers devote their time to caregiving, they often neglect their work-related issues, personal relationships, and mental state. This self-neglect can lead to worries, as the individual feels they are losing important opportunities for personal and social growth. Over time, their concerns about the future extend to various aspects of life, such as social relationships, mental health, and even their career future. “I am not only worried about my career future, but also about my future mental state. I am currently not in the mood for relationships with others, and I am worried about staying like this forever, and not finding new friends, ending up alone” (P.13).

Concerns about aging

One of the challenges faced by family caregivers was their concerns about their own old age. They had the fear that, during old age, they may experience disability or illness and have no one by their side to support them. These worries arise not only from concerns about potential physical disability or illness, but also from fears of lacking social or family support in the future. Since they devote all their energy and time to caring for the older adult, they witness the challenges of old people, leading to their concerns about their own old age. “Honestly, I think a lot about the future, about my old age. I feel like, oh my God, when I became old, I would be like this, or even more helpless than this? Oh God! Will there be someone by my side? To help me? The same way I care for my father? I think about it every single day. Oh God! What will happen to me?” (P.1)

Deterioration of mental capacity

The theme “Deterioration of mental capacity” had three sub-themes: Emotional fragility, feeling diluted, and the exhausting nature of care.

Emotional fragility

Emotional fragility was one of the primary challenges faced by family caregivers. Continuous caregiving pressures can weaken psychological resilience and make a person more vulnerable. Whereas previously it was possible to recover emotionally after challenges, in these circumstances, minor tensions can trigger feelings of breakdown. Caregivers may feel they have no mental capacity to manage their emotions as they used to, and attempts to regain mental strength often fail to produce the desired results. “Previously, when I had a problem, I could feel better after a few days, but now it’s not like that anymore, and I feel much more fragile. I try my best to get back on my feet and become strong, but I can’t anymore” (P.8).

Feeling diluted

The ongoing stress of caregiving, combined with limited support and few opportunities to restore energy, can leave caregivers without the necessary strength and energy to fulfill their duties. In this situation, continued caregiving is not done by intrinsic motivation, but simply by a sense of obligation and responsibility. “How much capacity does a person have? the person will eventually buckle under the pressure. When you’re under pressure from all sides, you feel diluted. You’re forcing yourself to do your job, and you’re just doing it because you have a task to do! That’s it” (P.8).

Exhausting nature of care

Caring for an older adult is an exhausting and draining process that often becomes more complex over time. The caregivers were not only under constant physical strain but also faced emotional challenges. Many of them felt increasingly helpless as the difficulty of caregiving gradually increased, and their usual coping strategies were no longer effective. In such circumstances, even everyday tasks can become an overwhelming challenge, causing caregivers to feel unable to continue. “I feel distressed; I am under a lot of emotional and physical pressure. Sometimes the pressure is so much that I sit down and cry! The situation has become worse; the caregiving process gets more difficult day by day. The emotional pressure is very high” (P.4).

Discussion

The present study was conducted to identify the psychological challenges of family caregivers of older adults with ADL dependence in Iran. The results indicated that family caregivers experience a set of challenges, including weakening of personal identity, disruption of relationships and emotional bonds, emotional stagnation, being surrounded by worries, and deterioration of psychological capacity, which are often overlooked.

The findings indicated that one of the main challenges for family caregivers of older adults was the weakening of personal identity. The caregiving role often causes the individual to abandon a major part of their personal identity and have a reduced sense of control over their life. Consistent with this finding, previous studies have also highlighted that maintaining personal identity and a sense of control over life are fundamental challenges for family caregivers of older adults [18, 29, 30]. In the present study, family caregivers reported that performing the caregiving role limited their ability to fulfill personal and social roles, compelling them to sacrifice their own priorities to meet the needs of the older adult. According to role theory, individuals assume multiple roles throughout their lives, and maintaining a balance among these roles is essential for preserving their personal identity. However, in situations where one role becomes excessively dominant, the individual may experience role strain and role conflict [31]. In this context, family caregivers, due to their heavy and continuous responsibilities, often have limited time to attend to their other roles, which can lead to feelings of alienation and a weakening of their personal identity. Ribeiro et al. [32]reported that family caregivers who take on a caregiving role often feel like they have lost their identity, which in turn negatively affects their mental health. Changes in responsibilities and roles cause additional pressure in an attempt to maintain a sense of control and personal identity. In Iranian culture, the sense of responsibility toward older adults is considered as an important value [23]. This sense of responsibility causes the caregivers to neglect their own needs and priorities and distance themselves from their personal identity.

The results indicated that family caregivers of older adults experienced disruptions in their relationships and emotional bonds. Caring for an older adult requires substantial time and energy, which can negatively affect caregivers’ emotional and social relationships, eventually leading to withdrawal and isolation. Consistent with this result, Hailu et al. [10] reported that interpersonal relationships gradually decline during the caregiving process, leaving caregivers with feelings of isolation and loneliness. Furthermore, a study on the interpersonal relationships of family caregivers has shown that these individuals need to be acknowledged in their relationships and receive emotional support [33]. In this study, many caregivers reported feeling excluded from relationships and gradually lost their motivation to connect with others. This often manifested in the form of a decline in marital relationships and emotional distancing from children. Constructive interpersonal relationships and social support can reduce the psychological burden and stress of caregivers and improve their mental health [34]. In Iranian culture, family relationships are considered the core of social interactions and emotional support [35].

The findings of the present study identified emotional stagnation as another psychological challenge faced by family caregivers of older adults. Caregivers reported a feeling of discouragement and a life devoid of joy. This phenomenon has been consistently observed in previous studies [14, 15]. Gagliardi et al. [36] reported that family caregivers suffer from a significant reduction in mental energy and symptoms of depression. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s stress theory, individuals experiencing stress and psychological pressure need to restore their psychological and physical energy in order to maintain health [37] In this context, family caregivers who are continuously engaged in caregiving tasks may be unable to regain their energy, leading to emotional stagnation that adversely affects their mental health. Rawlins [29] reported that family caregivers need to take a temporary break from caregiving responsibilities to cope with caregiving pressures and reduce negative emotions. This break time can help them restore psychological energy and maintain vitality and emotional strength.

One of the most fundamental psychological challenges of family caregivers in this study was being surrounded by worries. Family caregivers commonly experience multiple concerns, including concerns about accountability in care, worries about their future, and concerns about their own old age. These concerns can adversely affect caregivers’ psychological well-being, thereby reducing their ability to provide effective care. Consistent with this result, numerous studies have highlighted the prevalence of worry and anxiety among family caregivers of older adults [38, 39]. Caregivers often require psychological comfort to perform their duties effectively. Being constantly surrounded by worries can directly impact the quality of care provided. Bongelli et al. [40]reported that caring for older adults is a stressful and anxiety-provoking process. When caregivers are able to maintain mental peace during caregiving, they will be better able to provide care and feel more satisfied with their performance. Concerns about one’s own old age or future have also been reported among family caregivers from other cultural contexts [41, 42]; however, worries related to caregiving accountability seem to be more specific to Iranian culture.

The findings also revealed that family caregivers felt the deterioration of their mental capacity. Caregiving is an exhausting process, the intensity of which often increases over time. Long-term caregiving, particularly for older adults, can be physically and emotionally draining, gradually reducing caregivers’ sense of self-worth and depleting their psychological resources. This progressive experience of mental fatigue and helplessness may lead to feelings of inadequacy in fulfilling caregiving roles and even doubt about one’s own abilities. Muñoz‐Cruz et al. [43] found that family caregivers experienced considerable pressure and tension, and that appropriate training can help them manage these stressors more effectively and enhance their psychological capacity. Ding et al. [44] reported that family caregivers faced high levels of mental pressure, contributing to mental exhaustion. The longer the caregiving period, the greater the intensity of mental fatigue and stress. This aligns with the resilience theory, which emphasizes an individual’s capacity to cope with stressful conditions and maintain psychological well-being in the face of caregiving challenges [45]. Caregivers with higher mental capacity are better able to manage their psychological resources, maintain emotional balance, reduce stress, and address problems constructively.

This study had some disadvantages, such as the inclusion of family caregivers only from one province of Iran (Alborz Province), which may limit the generalizability of the findings to all family caregivers in Iran, and the inclusion of family caregivers with less than three years of caregiving experience (about 70% of participants) which may lead to lower reflection of the challenges associated with long-term care. Future research should include caregivers from different provinces and explore differences between those with low and high caregiving experiences, as well as gender differences in psychological needs. Moreover, future studies are recommended to examine the psychological challenges of the formal caregivers of older adults in Iran.

Conclusion

Family caregivers of older adults in Iran face some psychological challenges that are often overlooked. These challenges can directly or indirectly affect caregivers’ mental health, and their ignorance may lead to reduced quality of life and feelings of failure. To improve caregivers’ well-being, it is essential to design and implement educational and psychological support programs aimed at enhancing resilience, strengthening coping skills, and restoring psychological resources. Additionally, establishing social support networks and improving access to counseling services may help reduce the burdens of caregiving.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.215). In this study, all ethical principles were considered. The study objectives were fully explained to participants prior to data collection, and written informed consent was obtained from them. All information and data obtained through interviews were kept confidential, and the names of participants were not disclosed.

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Mojtaba Abbasi Asl, approved by the Department of Counseling, school of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Project management, conceptualization, and writing: Mojtaba Abbasi Asl, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Mahshid Foroughan; Methodology, data analysis, and visualization: Mojtaba Abbasi Asl and Mohammad Saeed Khanjani; Review and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants and the officials of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran for their approval and support of this study.

References

With the advancement of healthcare, preventive measures, and control of infectious diseases, the average human lifespan has increased, resulting in a significant rise in the aged population in both developed and developing countries [1]. According to the United Nations report, the global aged population was approximately 1.1 billion in 2023 and is projected to reach 1.2 billion by 2050. More than 80% of this population will live in low- and middle-income countries [2]. Similar to many countries, the aged population in Iran is increasing at a rate even higher than the global average, such that in 2022, the number of individuals over 60 years old exceeded 10% of the total population [3]. In old age, chronic physical and mental illnesses and cognitive and functional impairments increase [4], and thus the need for care services, especially long-term care, rises [5]. The older adults who are unable to perform their activities of daily living (ADLs) are at greater risk [6]. ADL refers to any task that an individual normally performs for self-care at home, outside the house, or both (such as toileting, eating, dressing, and undressing) [7]. Impairment in performing these activities leads to increased dependency and increases the risk of hospitalization in nursing homes or receiving full-time family care [8].

In developing countries, family caregiving plays a vital role in the care of disabled older adults. According to statistics, 80% of older adults requiring care are supervised by one of their family members [9]. In family caregiving, older adults require essential support due to their inability to perform ADLs. In these circumstances, relatives act as caregivers and provide care without receiving any compensation from the older adults [10]. Families play a central role in caring for vulnerable older adults. Approximately 80% of this care is provided at home by family caregivers, while less than 20% of the older adults receive formal care [11].

Despite the cost-effectiveness and efficacy of family caregiving, excessive reliance on families may have negative impacts on family members and on the physical, psychological, and social health of family caregivers [12]. Family caregiving is considered a challenging task and may lead to psychological and social problems among family caregivers [13]. Research has shown that family caregivers are more exposed to depression, stress, and caregiver burnout. These problems are primarily exacerbated by insufficient support and neglect of caregivers’ needs [14, 15]. Collins et al. [16] showed that 31% of family caregivers of older adults suffer from depressive symptoms and nearly 50% experience caregiver burden; when considering only female family caregivers, the prevalence of depression rises to almost 47%. Another study indicated that 32% of family caregivers of older adults struggle with anxiety [17]. Family caregivers of older adults face psychological challenges. Identifying these challenges and providing appropriate support can improve both the caregivers’ quality of life and that of the older adults they care for [18].

Studies conducted in various countries have examined the general challenges faced by family caregivers of older adults. For instance, Shuffler et al. [19] extracted the challenges experienced by family caregivers, and Akgun-Citak et al. [18] identified various challenges of this group. However, fewer studies have specifically focused on their psychological challenges, even though family caregivers face specific psychological issues such as a lack of social support, feeling guilty due to the inability to meet all the needs of older adults, lack of anger control towards older adults, and experiencing exclusion from important decision-making processes [20]. Most previous studies have not considered how dependent the older adults are on their caregivers. Therefore, the present study focuses on caregivers of older adults who are semi-dependent in performing ADLs, as this level of dependency may influence the type and intensity of psychological stress experienced by caregivers. It is also important to note that in studies on family caregiving, ethnic and cultural factors play a significant role [21]. Iranian family culture differs from that of other countries in several respects. It mostly follows the norms of the traditional family model [22], where a sense of duty toward older adults, along with kindness and respect, is highly valued [23]. However, to our knowledge, no study has specifically identified or explored the psychological challenges faced by Iranian family caregivers of older adults.

Considering the growth in the number of older adults, the crucial role of family caregivers, and the connection of family caregiving to the economic and social conditions, norms, and values of Iranian society, identifying the psychological challenges of family caregivers in Iran is essential for designing effective interventions to improve caregivers’ mental health. Therefore, the present research aims to identify the psychological challenges of the family caregivers of older adults with dependency in performing ADLs in Iran.

Materials and Methods

This is a qualitative research employing a conventional content analysis approach. This method is usually used when the body of literature on a given phenomenon is scarce [24]. The research was conducted between July 2023 and March 2024. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling method from family caregivers of older adults who attended the second branch of the Kahrizak Day Rehabilitation Center and the Zarman Comprehensive Rehabilitation Center, located in Alborz Province. Sampling continued until data saturation was reached. The selection of these two centers was due to their extensive services for older adults and the opportunity to access family caregivers with maximum social and economic diversity. Purposive sampling was used because the purpose of this method was to select individuals who are rich sources of information and can actively participate in the study, enabling the researcher to gain a deeper understanding of their experiences [25]. Inclusion criteria were: Being a family member who provides care for an older adult for at least four hours per day [26], providing care for more than six months, not receiving any payment for caregiving, age at least 18 years, and informed consent to participate in the study. To assess the older adults’ basic ADLs, the Barthel index [27] was used. This index consists of 10 items, scored on a scale from 0 to 2, indicating the level of independence or dependence in performing ADLs, with a total score ranging from 0 to 20; a score of 20 represents total independence, 13–19 moderate dependency, 9–12 severe dependency, and 0–8 total dependency [27]. The minimum score required to determine the older adult’s dependency level in our study was 9 (severe dependency).

The participants’ experiences were surveyed using semi-structured interviews. A total of 14 interviews were conducted with family caregivers of older adults, after providing an explanation of the research objectives to them. All interviews were recorded with their consent. Interview questions primarily focused on the psychological challenges of family caregivers during the caregiving period for older adults. The interview process began with a few general open-ended questions, e.g. “How has caring for an older adult changed your life?” or “What challenges has caregiving created for you?”. Then, based on the responses, more specific questions were asked to obtain deeper data. Each interview lasted for 30-60 minutes.

Data analysis was performed in MAXQDA software, version 2020, according to the steps proposed by Graneheim and Lundman [24]. The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were read several times to gain a general understanding of the content. Then, the transcribed text was carefully divided into condensed meaning units. In the third step, each sentence or paragraph was coded. Subsequently, the initial codes were compared, and similar codes were grouped into subcategories. In the final step, by continuously comparing subcategories based on similarities and differences, the main themes were extracted. To reduce the number of categories, this process was repeated several times until the main themes and sub-themes were obtained.

This study considered Lincoln and Guba’s four criteria for enhancing the trustworthiness and rigor of the research [28]. To increase credibility, the transcripts and the extracted codes were reviewed and validated by a research team including experts in psychology, counseling, and gerontology. Additionally, the codes were shared with three participants to ensure their alignment with the experiences they had described. Dependability was determined through prolonged engagement of the researcher with participants and the research topic, and holding multiple meetings with the research team to maintain a consistent framework for data collection and analysis. For confirmability, all stages of the research, including data collection, data analysis, and category development, were described in detail. To determine the transferability of the findings, purposeful efforts were made to ensure diversity in the samples by selecting participants with different socioeconomic statuses, different relationships with the older adult, different educational backgrounds, and different employment statuses.

Results

The participants were 14 family caregivers of older adults. The ages of older adults under care ranged from 66 to 87 years. Eleven (78.5%) of family caregivers were women, and three (21.4%) were men. The age range of the caregivers was 24-66 years (Mean age: 47.8 years). Seven caregivers (50.0%) were married, five (35.7%) were single, and two (14.2%) were divorced. Other sociodemographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

A total of 183 codes were extracted in the first stage of data analysis. These codes were categorized into 17 subcategories and five main categories, reflecting the psychological needs of family caregivers of older adults in Iran (Table 2).

Weakening of personal identity

The first theme was “Weakening of personal identity”. This theme consisted of four sub-themes: Neglect of personal interests, reduced sense of control over life, sacrifice of personal life, and feeling of wasting life.

Neglect of personal interest

Due to the heavy burden of caregiving responsibilities, family caregivers usually have little time to pursue their own interests and personal activities. Neglect of personal interests is a significant challenge in the daily lives of caregivers, as they often prioritize caring for the older adult over their own needs. “Sometimes I think of starting to learn a skill, a sport, or an instrument that I have wanted to learn for years, but because of my caregiving responsibilities and lack of time, I cannot go after it” (Participant No. (P.) 12).

Reduced sense of control over life

In many cases, family caregivers perceive themselves as surrounded by a set of responsibilities that deprive them of the freedom to change direction or pursue alternative paths. In such situations, decision-making about personal life becomes heavily influenced by external demands. Over time, this dynamic can create a sense of being trapped on an unchangeable path that should be endured. Consequently, caregivers may feel that they have lost control over their own lives, perceiving each decision as merely a response to pressures and circumstances imposed upon them.”I feel that I have no control over my future and life, and that there is an obligation to follow a certain path; it’s not up to me to decide what to do” (P.11).

Sacrifice of personal life

Forgetting about personal goals and plans is one of the main challenges for family caregivers. They sometimes feel that their personal lives are sacrificed for the needs of others. This means that in fulfilling caregiving responsibilities, they give up their goals, plans, and desires. In such a situation, a caregiver may perceive themselves as a means used solely for carrying other people. “I feel like I don’t live for myself! I spend my time either taking care of my mother or looking after my kids. I have to forget my own needs, I can’t do anything just for my own benefit anymore” (P.14).

Feeling of wasting life

Sometimes, family caregivers become so involved in the caregiving role that they are forced to leave their favorite jobs and perceive that the efforts they put into their careers in the past are no longer useful or beneficial. They may feel that, although they have been able to help others, they have not been able to reap the benefits of these efforts for themselves, leading to a sense that their time and life have been wasted. “I spent many years to study, and when my children were little, I had to leave them with their grandmothers to work! Now, I can’t benefit from these efforts. They are no longer useful, and I feel like I’ve wasted my life” (P.11).

Degradation of relationships and emotional bonds

The theme “Degradation of relationships and emotional bonds” included three sub-themes: Loneliness/isolation, being left out in relationships, and reduced motivation to form relationships.

Loneliness/isolation

Spending time caring for an older adult gradually leads to a reduction in the caregiver’s social relationships. Caregivers may find themselves in a limited circle of relationships, losing the ability to engage in intimate social relationships they previously enjoyed, which, in addition to damaging interpersonal relationships, can contribute to an emotional void in the caregiver’s personal life, causing the person to experience deep feelings of loneliness and isolation in the long term. “The caregiving role pushes a person towards loneliness. My social relationships have greatly declined. I used to spend more time with relatives and friends, but it has now been greatly reduced. Previously, I could see my friends every day, but now I can barely see them, maybe once a week” (P.3).

Being left out in relationships

In some cases, family caregivers observed that friends and relatives gradually distance themselves from them, and past relationships lose their former form. This is not necessarily the result of a conscious decision by others; rather, it can be due to a change in the interaction space and the caregiver’s mood, or a feeling of unfamiliarity among the caregivers and people around them. Over time, such changes can lead to fewer invitations, visits, and social interactions, causing the caregiver to feel that they no longer have the same place in their social network as before. “I used to go out with my friends. I was very close to my cousins; we had parties every week and we visited each other frequently, but now, when they visit us, my mother-in-law [the older adult] keeps talking to them and interrupting us, ruining our relationship, and doesn’t let them enjoy their time. I see that they are indirectly refusing to come to our house” (P.5).

Reduced motivation to form relationships

Some family caregivers gradually lost their motivation and desire to establish new relationships or maintain previous relationships. In such situations, even interactions that were previously valued may lose their appeal. This change can be accompanied by a sense of indifference, which prevents the individual from making efforts to maintain or form new relationships. “I feel numb and indifferent toward people. It doesn’t really matter whether my relationships are shattered or not. I have very little desire to socialize. I even spend my free time alone. I don’t have hope that a new relationship could be good for me” (P.12).

Emotional stagnation

The theme “Emotional stagnation” consists of four sub-themes: Feeling discouraged, joyless life, boredom, and monotonous life.

Feeling discouraged

When family caregivers are placed in situations for a long time where their emotional and psychological support resources are depleted, they may lose their courage and desire to pursue personal goals and preferred activities. This condition not only manifests as a reduced inclination to engage in pleasurable activities but can also lead to a sense of numbness and indifference toward the future. In this state, the individual is also unable to regain lost courage even when the conditions are met. “Even if I had the time, I would no longer have the motivation to go after the things I wanted in life. I don’t have the courage to do them anymore, it’s a sign of depression, I guess. I feel discouraged” (P.12).

Joyless life

Some family caregivers reported facing the challenge of living a life devoid of joy. This situation becomes particularly evident when daily responsibilities and caregiving duties leave little opportunity to pursue personal interests or engage in enjoyable activities. In such circumstances, caregivers may feel that life has lost its appeal and that neither activities nor social interactions bring satisfaction. “Nothing is enjoyable anymore! My life has become something I never wanted it to be. All I do is stay at home and take care of someone, which doesn’t make me feel better. I don’t enjoy anything in life” (P.13).

Boredom

Most family caregivers experienced boredom, especially when caregiving pressures continue chronically and over a long period. When an individual is continuously engaged in caregiving role, their energy and capacity to perform or even enjoy everyday activities naturally decline. This boredom can affect all aspects of life, causing the individual to withdraw from personal activities or social relationships. “I’m bored to do my work, interact with someone, do house chores, or do knitting. I don’t have the patience to cook the food I want or do something for myself” (P.9).

Monotonous life

A sense of monotony in life was one of the common experiences among caregivers, particularly when caring for an older adult becomes a daily repetitive job due to the lack of variety and change in daily activities. As a result, life turns into a routine and a cycle without diversity, where the person is unable to experience excitement or positive changes in their life. “Sometimes I feel like everything has become so repetitive, as if I was a robot programmed to wake up in the morning and do specific tasks at specific times. When a person does something monotonously, after a while, they like to change their schedule or timing. Nobody wants a monotonous life” (P.10).

Surrounded by worry

The theme “Surrounded by worry” included three sub-themes: Concerns about accountability in care, concerns about the future, and concerns about aging.

Concern about accountability in care

Concern about caregiving responsibilities was one of the major psychological challenges that some family caregivers faced. These concerns arise due to the fear of negative judgments by others, who may perceive the caregiver as incompetent or indifferent. The responsibility of caring for an older adult is accompanied by a fear that any mistake or negligence may lead to criticism or blame from others. This perception makes the caregivers constantly remind themselves to perform their duties in the best possible way in order to reduce the concerns about accountability in care. “If the old adult got sick, I would be responsible; I should be accountable. Everyone is watching me [ready to blame me]. These really make a person nervous; oh my God, if something bad happens, I have to answer to everyone’” (P.1).

Concerns about the future

When family caregivers devote their time to caregiving, they often neglect their work-related issues, personal relationships, and mental state. This self-neglect can lead to worries, as the individual feels they are losing important opportunities for personal and social growth. Over time, their concerns about the future extend to various aspects of life, such as social relationships, mental health, and even their career future. “I am not only worried about my career future, but also about my future mental state. I am currently not in the mood for relationships with others, and I am worried about staying like this forever, and not finding new friends, ending up alone” (P.13).

Concerns about aging

One of the challenges faced by family caregivers was their concerns about their own old age. They had the fear that, during old age, they may experience disability or illness and have no one by their side to support them. These worries arise not only from concerns about potential physical disability or illness, but also from fears of lacking social or family support in the future. Since they devote all their energy and time to caring for the older adult, they witness the challenges of old people, leading to their concerns about their own old age. “Honestly, I think a lot about the future, about my old age. I feel like, oh my God, when I became old, I would be like this, or even more helpless than this? Oh God! Will there be someone by my side? To help me? The same way I care for my father? I think about it every single day. Oh God! What will happen to me?” (P.1)

Deterioration of mental capacity

The theme “Deterioration of mental capacity” had three sub-themes: Emotional fragility, feeling diluted, and the exhausting nature of care.

Emotional fragility

Emotional fragility was one of the primary challenges faced by family caregivers. Continuous caregiving pressures can weaken psychological resilience and make a person more vulnerable. Whereas previously it was possible to recover emotionally after challenges, in these circumstances, minor tensions can trigger feelings of breakdown. Caregivers may feel they have no mental capacity to manage their emotions as they used to, and attempts to regain mental strength often fail to produce the desired results. “Previously, when I had a problem, I could feel better after a few days, but now it’s not like that anymore, and I feel much more fragile. I try my best to get back on my feet and become strong, but I can’t anymore” (P.8).

Feeling diluted

The ongoing stress of caregiving, combined with limited support and few opportunities to restore energy, can leave caregivers without the necessary strength and energy to fulfill their duties. In this situation, continued caregiving is not done by intrinsic motivation, but simply by a sense of obligation and responsibility. “How much capacity does a person have? the person will eventually buckle under the pressure. When you’re under pressure from all sides, you feel diluted. You’re forcing yourself to do your job, and you’re just doing it because you have a task to do! That’s it” (P.8).

Exhausting nature of care

Caring for an older adult is an exhausting and draining process that often becomes more complex over time. The caregivers were not only under constant physical strain but also faced emotional challenges. Many of them felt increasingly helpless as the difficulty of caregiving gradually increased, and their usual coping strategies were no longer effective. In such circumstances, even everyday tasks can become an overwhelming challenge, causing caregivers to feel unable to continue. “I feel distressed; I am under a lot of emotional and physical pressure. Sometimes the pressure is so much that I sit down and cry! The situation has become worse; the caregiving process gets more difficult day by day. The emotional pressure is very high” (P.4).

Discussion

The present study was conducted to identify the psychological challenges of family caregivers of older adults with ADL dependence in Iran. The results indicated that family caregivers experience a set of challenges, including weakening of personal identity, disruption of relationships and emotional bonds, emotional stagnation, being surrounded by worries, and deterioration of psychological capacity, which are often overlooked.

The findings indicated that one of the main challenges for family caregivers of older adults was the weakening of personal identity. The caregiving role often causes the individual to abandon a major part of their personal identity and have a reduced sense of control over their life. Consistent with this finding, previous studies have also highlighted that maintaining personal identity and a sense of control over life are fundamental challenges for family caregivers of older adults [18, 29, 30]. In the present study, family caregivers reported that performing the caregiving role limited their ability to fulfill personal and social roles, compelling them to sacrifice their own priorities to meet the needs of the older adult. According to role theory, individuals assume multiple roles throughout their lives, and maintaining a balance among these roles is essential for preserving their personal identity. However, in situations where one role becomes excessively dominant, the individual may experience role strain and role conflict [31]. In this context, family caregivers, due to their heavy and continuous responsibilities, often have limited time to attend to their other roles, which can lead to feelings of alienation and a weakening of their personal identity. Ribeiro et al. [32]reported that family caregivers who take on a caregiving role often feel like they have lost their identity, which in turn negatively affects their mental health. Changes in responsibilities and roles cause additional pressure in an attempt to maintain a sense of control and personal identity. In Iranian culture, the sense of responsibility toward older adults is considered as an important value [23]. This sense of responsibility causes the caregivers to neglect their own needs and priorities and distance themselves from their personal identity.

The results indicated that family caregivers of older adults experienced disruptions in their relationships and emotional bonds. Caring for an older adult requires substantial time and energy, which can negatively affect caregivers’ emotional and social relationships, eventually leading to withdrawal and isolation. Consistent with this result, Hailu et al. [10] reported that interpersonal relationships gradually decline during the caregiving process, leaving caregivers with feelings of isolation and loneliness. Furthermore, a study on the interpersonal relationships of family caregivers has shown that these individuals need to be acknowledged in their relationships and receive emotional support [33]. In this study, many caregivers reported feeling excluded from relationships and gradually lost their motivation to connect with others. This often manifested in the form of a decline in marital relationships and emotional distancing from children. Constructive interpersonal relationships and social support can reduce the psychological burden and stress of caregivers and improve their mental health [34]. In Iranian culture, family relationships are considered the core of social interactions and emotional support [35].

The findings of the present study identified emotional stagnation as another psychological challenge faced by family caregivers of older adults. Caregivers reported a feeling of discouragement and a life devoid of joy. This phenomenon has been consistently observed in previous studies [14, 15]. Gagliardi et al. [36] reported that family caregivers suffer from a significant reduction in mental energy and symptoms of depression. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s stress theory, individuals experiencing stress and psychological pressure need to restore their psychological and physical energy in order to maintain health [37] In this context, family caregivers who are continuously engaged in caregiving tasks may be unable to regain their energy, leading to emotional stagnation that adversely affects their mental health. Rawlins [29] reported that family caregivers need to take a temporary break from caregiving responsibilities to cope with caregiving pressures and reduce negative emotions. This break time can help them restore psychological energy and maintain vitality and emotional strength.

One of the most fundamental psychological challenges of family caregivers in this study was being surrounded by worries. Family caregivers commonly experience multiple concerns, including concerns about accountability in care, worries about their future, and concerns about their own old age. These concerns can adversely affect caregivers’ psychological well-being, thereby reducing their ability to provide effective care. Consistent with this result, numerous studies have highlighted the prevalence of worry and anxiety among family caregivers of older adults [38, 39]. Caregivers often require psychological comfort to perform their duties effectively. Being constantly surrounded by worries can directly impact the quality of care provided. Bongelli et al. [40]reported that caring for older adults is a stressful and anxiety-provoking process. When caregivers are able to maintain mental peace during caregiving, they will be better able to provide care and feel more satisfied with their performance. Concerns about one’s own old age or future have also been reported among family caregivers from other cultural contexts [41, 42]; however, worries related to caregiving accountability seem to be more specific to Iranian culture.

The findings also revealed that family caregivers felt the deterioration of their mental capacity. Caregiving is an exhausting process, the intensity of which often increases over time. Long-term caregiving, particularly for older adults, can be physically and emotionally draining, gradually reducing caregivers’ sense of self-worth and depleting their psychological resources. This progressive experience of mental fatigue and helplessness may lead to feelings of inadequacy in fulfilling caregiving roles and even doubt about one’s own abilities. Muñoz‐Cruz et al. [43] found that family caregivers experienced considerable pressure and tension, and that appropriate training can help them manage these stressors more effectively and enhance their psychological capacity. Ding et al. [44] reported that family caregivers faced high levels of mental pressure, contributing to mental exhaustion. The longer the caregiving period, the greater the intensity of mental fatigue and stress. This aligns with the resilience theory, which emphasizes an individual’s capacity to cope with stressful conditions and maintain psychological well-being in the face of caregiving challenges [45]. Caregivers with higher mental capacity are better able to manage their psychological resources, maintain emotional balance, reduce stress, and address problems constructively.

This study had some disadvantages, such as the inclusion of family caregivers only from one province of Iran (Alborz Province), which may limit the generalizability of the findings to all family caregivers in Iran, and the inclusion of family caregivers with less than three years of caregiving experience (about 70% of participants) which may lead to lower reflection of the challenges associated with long-term care. Future research should include caregivers from different provinces and explore differences between those with low and high caregiving experiences, as well as gender differences in psychological needs. Moreover, future studies are recommended to examine the psychological challenges of the formal caregivers of older adults in Iran.

Conclusion

Family caregivers of older adults in Iran face some psychological challenges that are often overlooked. These challenges can directly or indirectly affect caregivers’ mental health, and their ignorance may lead to reduced quality of life and feelings of failure. To improve caregivers’ well-being, it is essential to design and implement educational and psychological support programs aimed at enhancing resilience, strengthening coping skills, and restoring psychological resources. Additionally, establishing social support networks and improving access to counseling services may help reduce the burdens of caregiving.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.215). In this study, all ethical principles were considered. The study objectives were fully explained to participants prior to data collection, and written informed consent was obtained from them. All information and data obtained through interviews were kept confidential, and the names of participants were not disclosed.

Funding

This study was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Mojtaba Abbasi Asl, approved by the Department of Counseling, school of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Project management, conceptualization, and writing: Mojtaba Abbasi Asl, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Mahshid Foroughan; Methodology, data analysis, and visualization: Mojtaba Abbasi Asl and Mohammad Saeed Khanjani; Review and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants and the officials of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran for their approval and support of this study.

References

- Tohit NFM, Haque M. Gerontology in public health: A scoping review of current perspectives and interventions. Cureus. 2024; 16(7):13-27. [PMID]

- Matsuura H. Further acceleration in fertility decline in 2023: deviation of Recently published provisional fertility estimates in selected OECD countries from those in the 2022 revision of the world population prospects. Journal of Biodemography and Social Biology. 2024; 69(2):55-68. [PMID]

- Doshmangir L, Khabiri R, Gordeev VS. Policies to address the impact of an ageing population in Iran. The Lancet. 2023; 401(10382):1078-89. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00179-4] [PMID]

- Wu N, Xie X, Cai M, Han Y, Wu S. Trends in health service needs, utilization, and non-communicable chronic diseases burden of older adults in China: Evidence from the 1993 to 2018 National Health Service Survey. International Journal for Equity in Health. 2023; 22(1):169-82. [DOI:10.1186/s12939-023-01983-7] [PMID]

- Karami Matin B, Kazemi Karyani A, Soltani S, Rezaei S, Soofi M. [Predictors of healthcare expenditure: Aging, disability or development (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2019; 20(4):310-21. [DOI:10.32598/rj.20.4.310]

- Gao J, Gao Q, Huo L, Yang J. Impaired activity of daily living status of the older adults and its influencing factors: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(23):87-98. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph192315607] [PMID]

- Wang LY, Feng M, Hu XY, Tang ML. Association of daily health behavior and activity of daily living in older adults in China. Scientific Reports. 2023; 13(1):19484. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-023-44898-7] [PMID]

- Mahmoudzadeh H, Aghayari Hir T, Hatami D. [Study and analysis of the elderly population of the Iran (Persian)]. Journal of Geographical Researches. 2022; 37(1):111-25. [DOI:10.29252/geores.37.1.111]

- Noroozian M. The elderly population in iran: an ever growing concern in the health system. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2012; 6(2):1-6. [PMID]

- Hailu GN, Abdelkader M, Meles HA, Teklu T. Understanding the support needs and challenges faced by family caregivers in the care of their older adults at home. A qualitative study. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2024; 14(19):481-90. [DOI:10.2147/CIA.S451833] [PMID]

- Tu J, Li H, Ye B, Liao J. The trajectory of family caregiving for older adults with dementia: Difficulties and challenges. Age and Ageing. 2022; 51(12):afac254. [DOI:10.1093/ageing/afac254] [PMID]

- Søvde BE, Sandvoll AM, Natvik E, Drageset J. Caregiving for frail home-dwelling older people: A qualitative study of family caregivers’ experiences. International Journal of Older People Nursing. 2024; 19(1):e12586. [DOI:10.1111/opn.12586] [PMID]

- Willemse E, Anthierens S, Farfan-Portet MI, Schmitz O, Macq J, Bastiaens H, et al. Do informal caregivers for elderly in the community use support measures? A qualitative study in five European countries. BMc Health Services Research. 2016; 16:270. [DOI:10.1186/s12913-016-1487-2] [PMID]

- Agyemang-Duah W, Abdullah A, Rosenberg MW. Caregiver burden and health-related quality of life: A study of informal caregivers of older adults in Ghana. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition. 2024; 43(1):31. [DOI:10.1186/s41043-024-00509-3] [PMID]

- Oh E, Moon S, Chung D, Choi R, Hong GS. The moderating effect of care time on care-related characteristics and caregiver burden: Differences between formal and informal caregivers of dependent older adults. Journal of Frontiers in Public Health. 2024; 12:1354263. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1354263] [PMID]

- Collins RN, Kishita N. Prevalence of depression and burden among informal care-givers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing & Society. 2020; 40(11):2355-92. [DOI:10.1017/S0144686X19000527]

- Kaddour L, Kishita N. Anxiety in informal dementia carers: A meta-analysis of prevalence. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 2020; 3(33):161-72. [DOI:10.1177/0891988719868313] [PMID]

- Akgun-Citak E, Attepe-Ozden S, Vaskelyte A, Van Bruchem-Visser RL, Pompili S, Kav S, et al. Challenges and needs of informal caregivers in elderly care: Qualitative research in four European countries, the TRACE project. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2020; 87:103971. [DOI:10.1016/j.archger.2019.103971] [PMID]

- Shuffler J, Lee K, Fields N, Graaf G, Cassidy J. Challenges experienced by rural informal caregivers of older adults in the United States: A scoping review. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 2023; 20(4):520-35. [DOI:10.1080/26408066.2023.2183102] [PMID]

- Steenfeldt VØ, Aagerup LC, Jacobsen AH, Skjødt U. Becoming a family caregiver to a person with dementia: A literature review on the needs of family caregivers. SAGE Open Nursing. 2021; 22(7):23779608211029073. [DOI:10.1177/23779608211029073] [PMID]

- Tran JT, Theng B, Tzeng HM, Raji M, Serag H, Shih M. Cultural diversity impacts caregiving experiences: A comprehensive exploration of differences in caregiver burdens, needs, and outcomes. Cureus. 2023; 15(10):e46537. [PMID]

- Chitsaz MJ. [The Iranian family and socio-cultural transformations: A generational analysis (Persian)]. Journal of Social Problems of Iran. 2023; 14(1):89-112. [DOI:10.61186/jspi.14.1.89]

- Mohamadi Shahbalaghi F. [Self- efficacy and caregiver strain in alzheimer’s caregivers (Persian)]. Salmand. 2006; 1(1):26-33. [Link]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004; 24(2):105-12.[DOI:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001] [PMID]

- Grove SK, Burns N, Gray J. The practice of nursing research: Appraisal, synthesis, and generation of evidence. Edinburgh: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2012. [Link]

- Kent EE, Rowland JH, Northouse L, Litzelman K, Chou WYS, Shelburne N, et al. Caring for caregivers and patients: Research and clinical priorities for informal cancer caregiving. Cancer. 2016; 122(13):1987-95. [DOI:10.1002/cncr.29939] [PMID]

- Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional evaluation: the Barthel Index: a simple index of independence useful in scoring improvement in the rehabilitation of the chronically ill. Maryland State Medical Journal. 1965; 14:56-61. [PMID]

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic inquiry. Beverly Hills (CA): Sage Publications; 1985. [Link]

- Rawlins SR. Using the connecting process to meet family caregiver needs. Journal of Professional Nursing. 1991; 7(4):213-20. [DOI:10.1016/8755-7223(91)90030-o] [PMID]

- Sousa GS, Silva RM, Reinaldo AM, Brasil CC, Pereira MO, Minayo MC. Metamorfosis in the lives of elderly people caring for dependent elderly in brazil. Texto & Contexto-Enfermagem. 2021; 30:e20200608. [DOI:10.1590/1980-265X-TCE-2020-0608]

- Anglin AH, Kincaid PA, Short JC, Allen DG. Role theory perspectives: Past, present, and future applications of role theories in management research. Journal of Management. 2022; 48(6):1469-502. [DOI:10.1177/01492063221081442]

- Ribeiro L, Ho BQ, Senoo D, editors. How does a family caregiver’s sense of role loss impact the caregiving experience? Healthcare; 2021; 9(10):1337. [DOI:10.3390/healthcare9101337] [PMID]

- Morelli N, Barello S, Mayan M, Graffigna G. Supporting family caregiver engagement in the care of old persons living in hard to reach communities: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community. 2019; 27(6):1363-74. [DOI:10.1111/hsc.12826] [PMID]

- Noguchi T, Nakagawa-Senda H, Tamai Y, Nishiyama T, Watanabe M, Hosono A, et al. Neighbourhood relationships moderate the positive association between family caregiver burden and psychological distress in Japanese adults: A cross-sectional study. Public Health. 2020; 185:80-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.009] [PMID]

- KavehFarsani Z, Safi S, Bahmani A. [Introductory in family counseling with islamic-iraninan culture-based approch (Persian)]. Family Counseling and Psychotherapy. 2019; 9(1):49-74. [DOI:10.34785/J015.2019.015]

- Gagliardi C, Piccinini F, Lamura G, Casanova G, Fabbietti P, Socci M. The burden of caring for dependent older people and the resultant risk of depression in family primary caregivers in Italy. Sustainability. 2022; 14(6):3375. [DOI:10.3390/su14063375]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Link]

- Medrano M, Rosario RL, Payano AN, Capellán NR. Burden, anxiety and depression in caregivers of Alzheimer patients in the dominican republic. Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 2014; 8(4):384-8. [DOI:10.1590/S1980-57642014DN84000013] [PMID]

- Moss KO, Kurzawa C, Daly B, Prince-Paul M. Identifying and addressing family caregiver anxiety. Journal of Hospice & Palliative Nursing. 2019; 21(1):14-20. [DOI:10.1097/NJH.0000000000000489] [PMID]

- Bongelli R, Busilacchi G, Pacifico A, Fabiani M, Guarascio C, Sofritti F, et al. Caregiving burden, social support, and psychological well-being among family caregivers of older Italians: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Frontiers in Public Health. 2024; 12:1474967. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2024.1474967] [PMID]

- Sichimba F, Janlöv AC, Khalaf A. Family caregivers’ perspectives of cultural beliefs and practices towards mental illness in Zambia: An interview-based qualitative study. Scientific Reports. 2022; 12(1):21388. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-022-25985-7] [PMID]

- Hazzan AA, Dauenhauer J, Follansbee P, Hazzan JO, Allen K, Omobepade I. Family caregiver quality of life and the care provided to older people living with dementia: Qualitative analyses of caregiver interviews. BMC Geriatrics. 2022; 22(1):86-97. [DOI:10.1186/s12877-022-02787-0] [PMID]