Volume 26, Issue 3 (Autumn 2025)

jrehab 2025, 26(3): 360-379 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.USWR.REC.1396.308

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sadeghi Sedeh S, Mirzaie H, Fatoreh Chy S, Ghayomi Z, Sadeghi Sedeh B. Effect of a Family-centered Early Intervention on Psychological Symptoms and Quality of Life in Mothers of Children with Down Syndrome: A Randomized Clinical Trial. jrehab 2025; 26 (3) :360-379

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3552-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3552-en.html

Sahar Sadeghi Sedeh1

, Hooshang Mirzaie1

, Hooshang Mirzaie1

, Saeed Fatoreh Chy1

, Saeed Fatoreh Chy1

, Zahra Ghayomi2

, Zahra Ghayomi2

, Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh *3

, Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh *3

, Hooshang Mirzaie1

, Hooshang Mirzaie1

, Saeed Fatoreh Chy1

, Saeed Fatoreh Chy1

, Zahra Ghayomi2

, Zahra Ghayomi2

, Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh *3

, Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh *3

1- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Social Medicine, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,drbhs59176@gmail.com

2- Department of Occupational therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Social Medicine, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 2621 kb]

(506 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2673 Views)

Full-Text: (552 Views)

Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common chromosomal abnormality in live births, leading to difficulties in mental functioning and adaptation in conceptual, social, and practical areas during growth and development. Most children with DS have mild to moderate intellectual disabilities. These children experience delays in various aspects of development, including sensory-motor, cognitive, and psychosocial aspects. These delays cause significant limitations in activities such as dressing, eating, functional movement, play, or school attendance. Therefore, these children need more care. In most cases, mothers are responsible for the care of their DS children [1, 2]. Mothers need to spend more time on feeding and taking the child to medical or rehabilitation centers. This causes their lifestyle to be affected by the needs of their children [3], which influences other family members. Mothers may neglect their own interests and other children. They have to spend less time on social, leisure, and sports activities, and have less time to sleep and rest [4]. These challenges cause severe stress in mothers, and who often do not receive enough therapeutic, economic, and welfare support [5]. As a result, they have lower mental health and quality of life (QOL) compared to mothers with normally developed children [6]. The QOL is influenced by individuals’ perceptions of culture, values, goals, standards, and priorities that are not visible to others, and is based on their perceptions of various aspects of life [7]. Mental health refers to the ability to communicate properly with others, modify the individual and social environment, and solve personal conflicts logically, fairly, and appropriately [8]. Several studies have shown lower mental health and QOL in parents, especially mothers, of children with DS than in mothers with normal children [9, 10].

The disruption of psychological health and QOL in mothers has a negative impact on the development process of their children and other family members and may make the family enter into a vicious cycle. Therefore, rehabilitation and educational interventions to effectively support DS children and their families should be done simultaneously. Research has shown that such interventions should consider the family as a unit, rather than focusing solely on the child. Family-centered interventions take this feature into account [11]. In family-centered interventions, the main approach is to help families whose children have developmental delays. Instead of focusing on shortcomings, these interventions emphasize the family’s abilities and give them more decision-making power. This approach is sensitive to the complexities in the family and responds to the priorities. It also supports caregiving behaviors that help the child’s growth and learning [12].

One type of family-centered intervention is early intervention, which refers to both patient-centered and family-centered concepts. The primary goal of early interventions is to enhance the awareness and developmental adaptation of families and children. This goal is pursued by identifying and reducing parental stress and introducing appropriate support systems. The early intervention is coordinated with the family’s needs and leads to a reduction in focus on the child and an increase in focus on the family [13]. In other words, early intervention is a support/educational system that helps the child and their family from birth or after the diagnosis of developmental disorders in children. Various studies have shown that the effects of early interventions include reduced complications, shorter time spent, lower costs, and greater efficiency. These interventions also help to correct the functional norms and executive function of children [14]. It has been determined that the use of appropriate and early support/educational interventions for parents of children with DS leads to improved self-confidence and child care quality [15]. For example, the studies by Hosseinali Zade et al. and Tomris et al. on the effect of early interventions on families of children with DS showed that parents gained a better understanding of their child’s strengths and abilities and were more optimistic about the future [16, 17]. Also, Brian et al. showed that a parent-mediated intervention improved parents’ use of treatment strategies and reduced their stress [18].

Considering that children’s physical disabilities lead to parental fatigue and occurrence of psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, family tension, marital dissatisfaction, and social problems, and since children’s growth is closely related to their parents’ physical and mental health, psychological stress in parents affects their function and, consequently, the children’s growth [19]. On the other hand, considering the increasing prevalence of DS and the associated problems and challenges for families, the need for early interventions for them is felt. These interventions should be accessible and inexpensive. It seems that if the early interventions are provided through a booklet, it can be more cost-effective [20]. However, the impact of early intervention using this technique on various aspects of parents’ lives, especially their mental health and QOL, has been less studied. Therefore, this study aims to assess the effect of a family-centered early educational intervention on the psychological symptoms (depression, anxiety, stress) and QOL of mothers of children with DS.

Materials and Methods

Participants

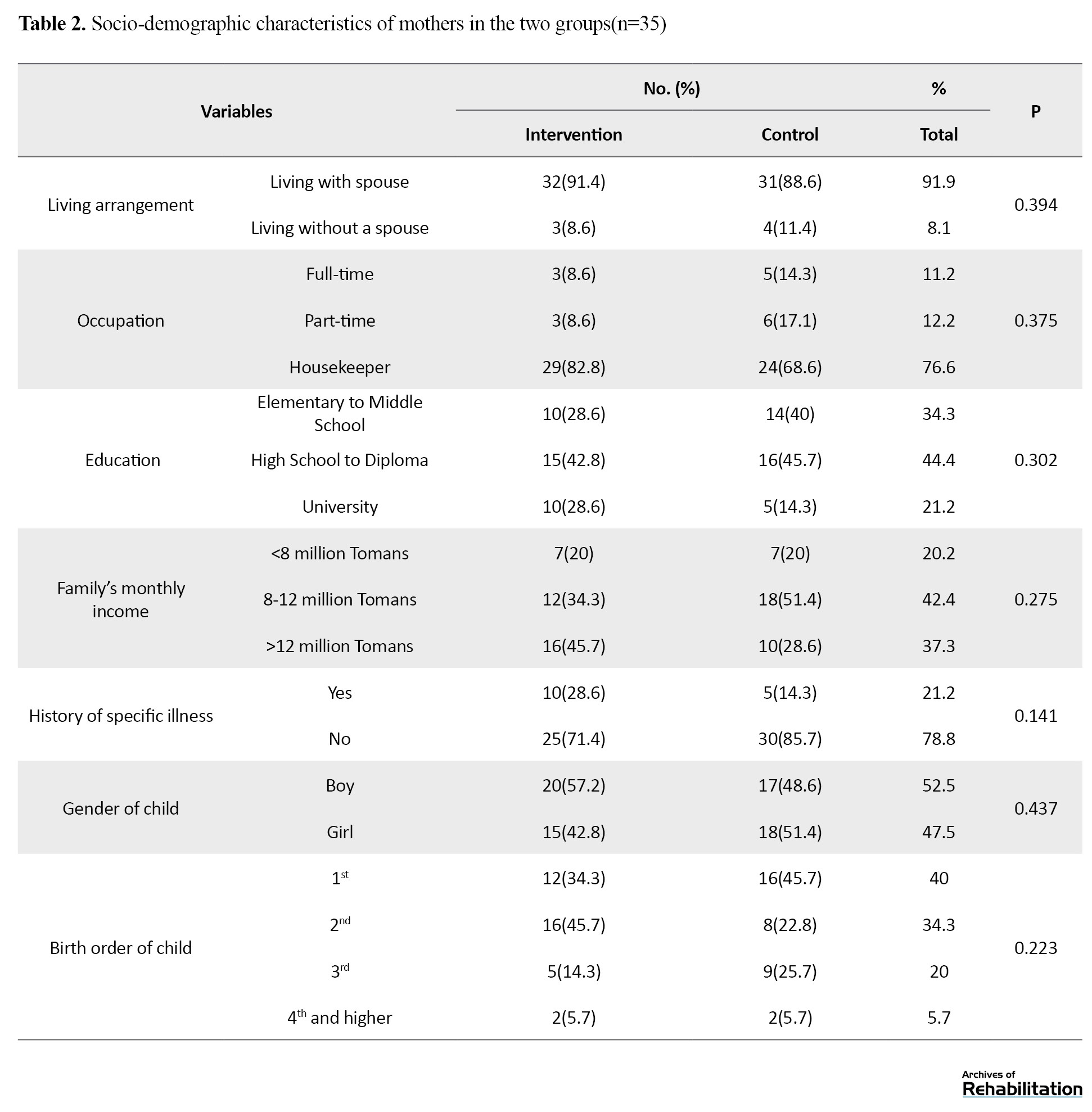

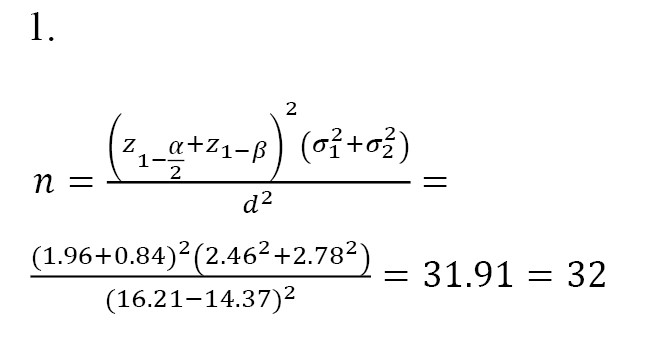

This is a single-blind randomized clinical trial conducted during 2022-2023. The study population consists of mothers of children with DS referred to the Aseman-e Nili DS center in Isfahan, Iran. The required sample size for each group was determined 32 using Equation 1, considering σ1=2.46, σ2=2.78, and a mean difference (d) of 1.84 according to Faramarzi and Malekpour’s study [21] on the impact of early intervention on the mental health of mothers of DS children, and a 95% confidence interval (CI), and 80% test power. Considering the potential sample dropout, the sample size for each group increased to 35.

Inclusion criteria were having a child with DS, child’s age 6-72 months, child being cared for at home, mothers’ willingness to participate in the study, a general health questionnaire-28 item (GHQ-28) score >23, mother’s ability to read, understand, and answer questions, no severe medical abnormalities and problems, including orthopedic disorders, seizures, uncontrolled thyroid disorders, congenital heart defects requiring surgery, no severe visual or hearing impairments, or a history of neonatal infection (meningitis and encephalitis), and having no other child with a chronic illness, including DS. Exclusion criteria were: Absence from one of the four educational sessions, diagnosis of a mental or physical illness requiring medication or surgical intervention during the three-month intervention period, mothers’ lack of cooperation in performing exercises in more than 10% of the intervention program, and family disruption or divorce/separation during the study.

After obtaining the ethics code from the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences in Tehran, and referring to the Isfahan DS Association and the Aseman-e Nili Center, 115 mothers were selected from a list using simple random sampling based on a random number table. They were asked to complete the GHQ-28. Those who scored higher than 23 and met the inclusion criteria were selected [22]. After matching for mother’s age, child’s age, care hours, and socio-economic status, they were randomly divided into two groups of 35 including intervention and control groups, by the coin toss method. The heads were assigned to the intervention group and the tails to the control group.

Instruments

The GHQ-28, designed by Goldberg in 1997, was used to screen for mental health issues. Its Persian version has good validity and reliability. It has a test re-test reliability, split-half reliability, and Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0.70, 0.93, and 0.90, respectively. The GHQ-28 has four subscales: Somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression, each containing seven items rated on a 4-point Likert scale: Not at all, no more than usual, rather more than usual, and much more than usual. The total score ranges from 0 to 84, with lower scores indicating better general health. A score of 23 is considered a threshold for unfavorable general health [23].

The depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21), developed by Lovibond in 1995, was used to measure the mental health of mothers. It is a 21-item self-report scale for assessing depression, anxiety, and stress. For the Persian version, Samani and Joukar reported a test re-test reliability of 0.80, 0.76, and 0.77, and Cronbach’s α values of 0.81, 0.74, and 0.78 for the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales, respectively [24].

The World Health Organization QOL scale (WHOQOL-BREF) was used to measure the QOL of mothers. This 26-item questionnaire measures four domains of QOL: Physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. It uses a 5-point Likert scale from 1 to 5 (not at all, not much, moderately, very much, and completely). The total score of each domain ranges from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating better QOL. This tool was validated in Iran by Nejat et al. In their study, test re-test reliability for the subscales was 0.77, 0.77, 0.75, and 0.84 for physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment, respectively. Cronbach’s α values for the subscales were the same, indicating the acceptable internal consistency of the WHOQOL-BREF for the Iranian population [25].

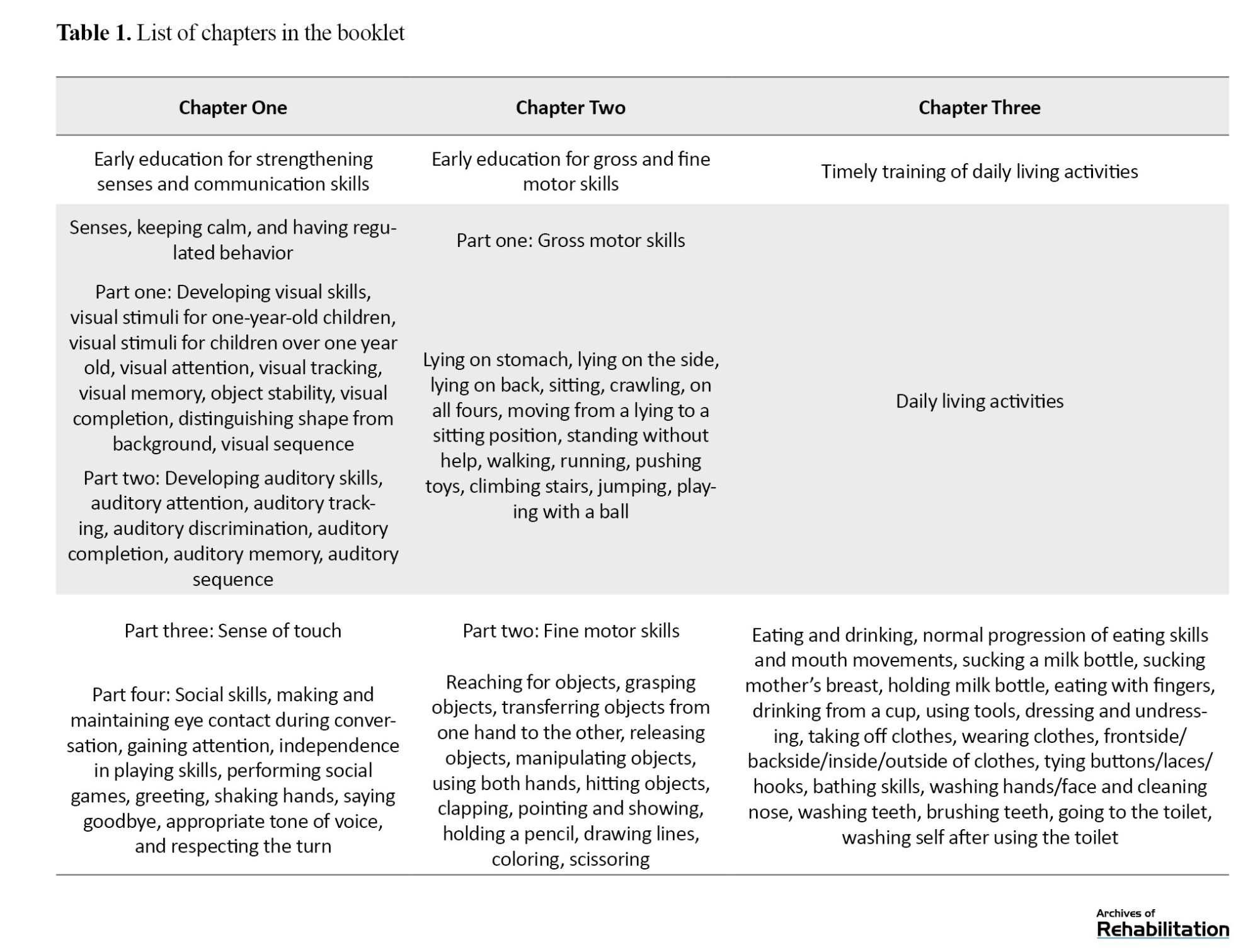

Intervention

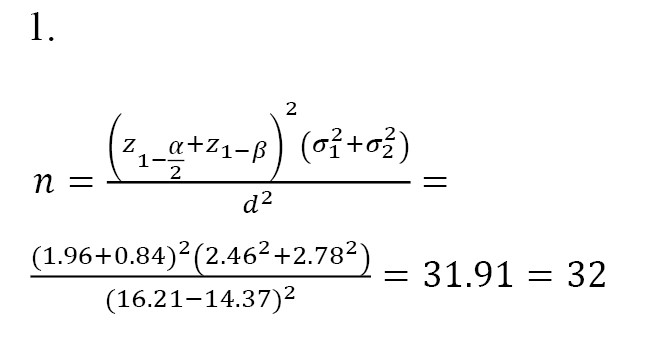

The educational intervention was provided using a 75-page booklet with a preface and three chapters [26]. In the preface section, information about DS, the care needs of children with DS and the problems of their parents, how to identify family strengths, how to make decisions and determine family priorities, how to increase the awareness and adaptation of all family members, support systems, and the definition and effects of early interventions are discussed. The first chapter focuses on sensory adjustment and the development of appropriate communication skills, including practical exercises. The second chapter focuses on gross and fine motor skills, including practical exercises designed to enhance these skills. The third chapter discusses how to utilize the child’s abilities and enhance their independence in performing daily living activities. Table 1 lists the contents of each chapter.

This booklet presents the desired exercises in the form of daily living activities, and also mentions the appropriate age for acquiring each skill, and provides the necessary exercises for each skill, in order. The exercises are shown with a photo, making it easy for mothers to implement them in their daily lives. An example of an exercise to improve visual memory while cooking is given below: “While cooking, ask the child to look at the objects on the table, then close their eyes and pick up an object and ask them to name the object that is no longer on the table.”

In the intervention group, four one-hour individual educational sessions were held. In each session, one chapter of the booklet, as well as early educational techniques and assignments, were presented to the mothers. The content of each chapter and the assignments were fully explained. To ensure the mothers’ learning, they performed several exercises in the presence of a therapist. The intervention was designed to reduce the stress of mothers with DS children, considering the challenges they face in teaching their children. Given the time constraints of mothers, the content required minimal instruction and was presented in a self-help format. During these sessions, each mother learned how to implement each exercise practically, and checklists were completed weekly by mothers for continuous follow-up. They should record the date of each day they completed the exercises and specify the chapter of the booklet used. They also noted any challenges they encountered while performing the exercise and shared them with the researcher when they handed in the checklist. After the intervention, the mothers were followed up for 3 months. Follow-ups were conducted weekly via telephone calls to guide them if problems arose. The mothers could contact the researcher at any time if they needed more consultation. Some days, the researcher was present at the center to answer the mothers’ potential questions and collect the completed weekly checklists. The average follow-up time for mothers was 97 days. The control group received only their usual treatments, including occupational therapy, speech therapy, and behavioral therapy, in the DS association. Also, in cooperation with the DS association, regular occupational therapy and speech therapy classes were held for the mothers in the control group. After the end of the intervention, all mothers in the control group were informed about the results of the study.

Data analysis

The data were collected before and after the intervention. After examining the normality of data distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, descriptive and inferential statistical methods, including the Mann-Whitney U test, the Wilcoxon test, and the chi-square test, were used for data analysis in SPSS software, version 21.

Results

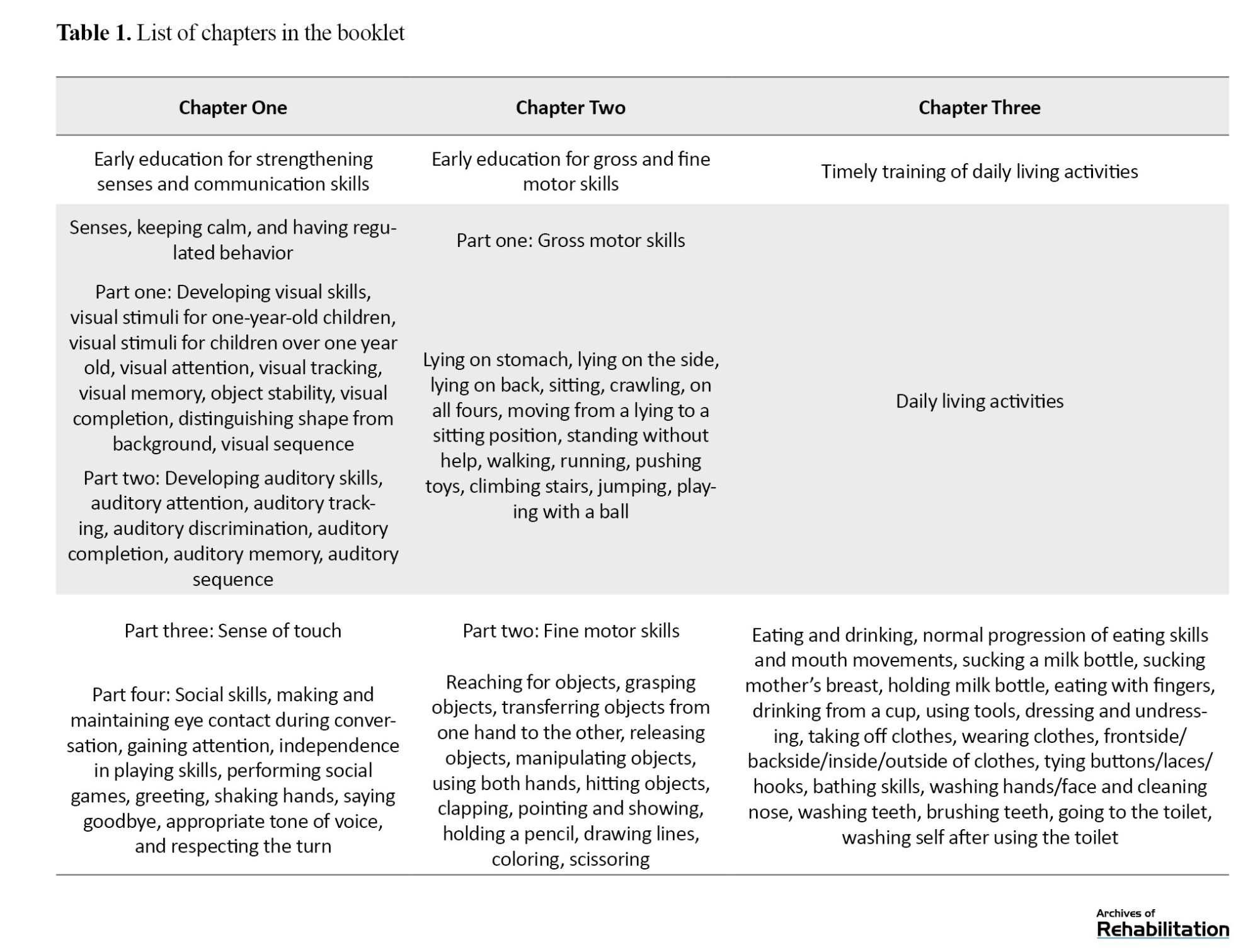

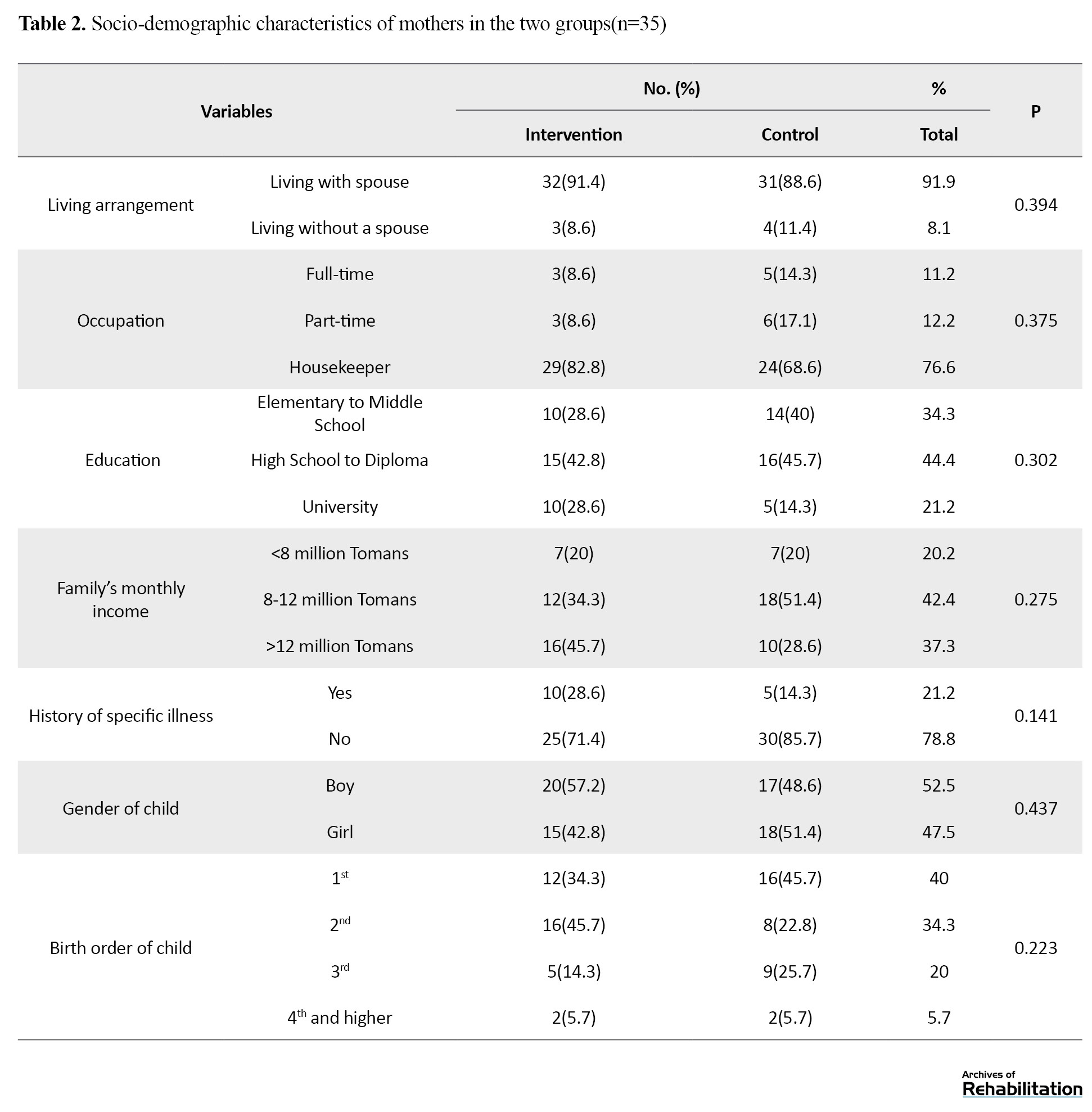

The mean age of mothers was 35.4±1.8 years, and the mean age of children was 33.8±14.8 months. Among 70 mothers, 91.9% were living with their spouses, and 8.1% were living without a spouse. Also, 76.6% were housewives, 44.4% had a high school diploma or lower education, and 42.4% had a monthly income of 8-12 million Tomans. Based on the chi-square test results shown in Table 2, there was no statistically significant difference between the control and intervention groups regarding the sociodemographic factors (P>0.05).

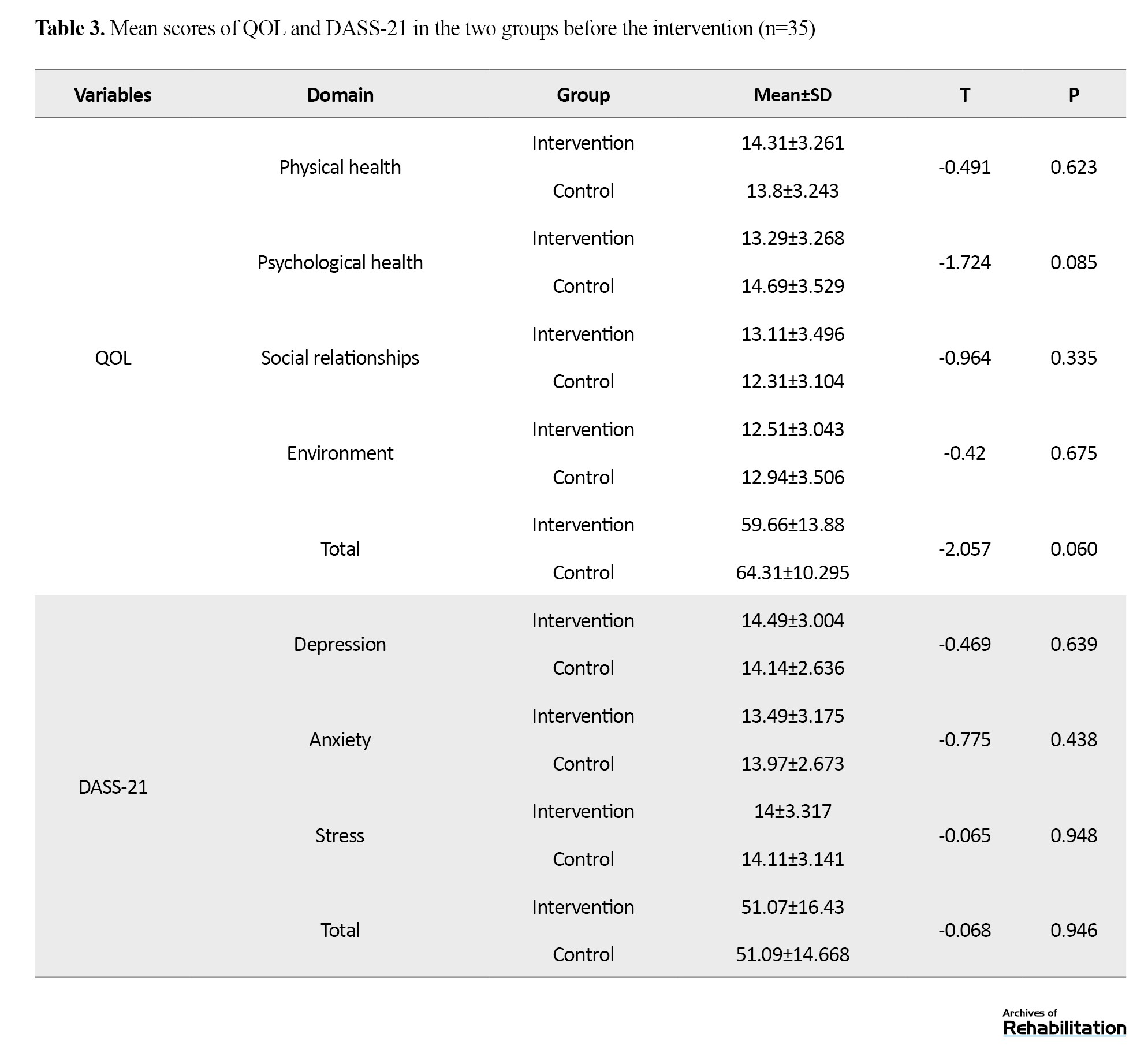

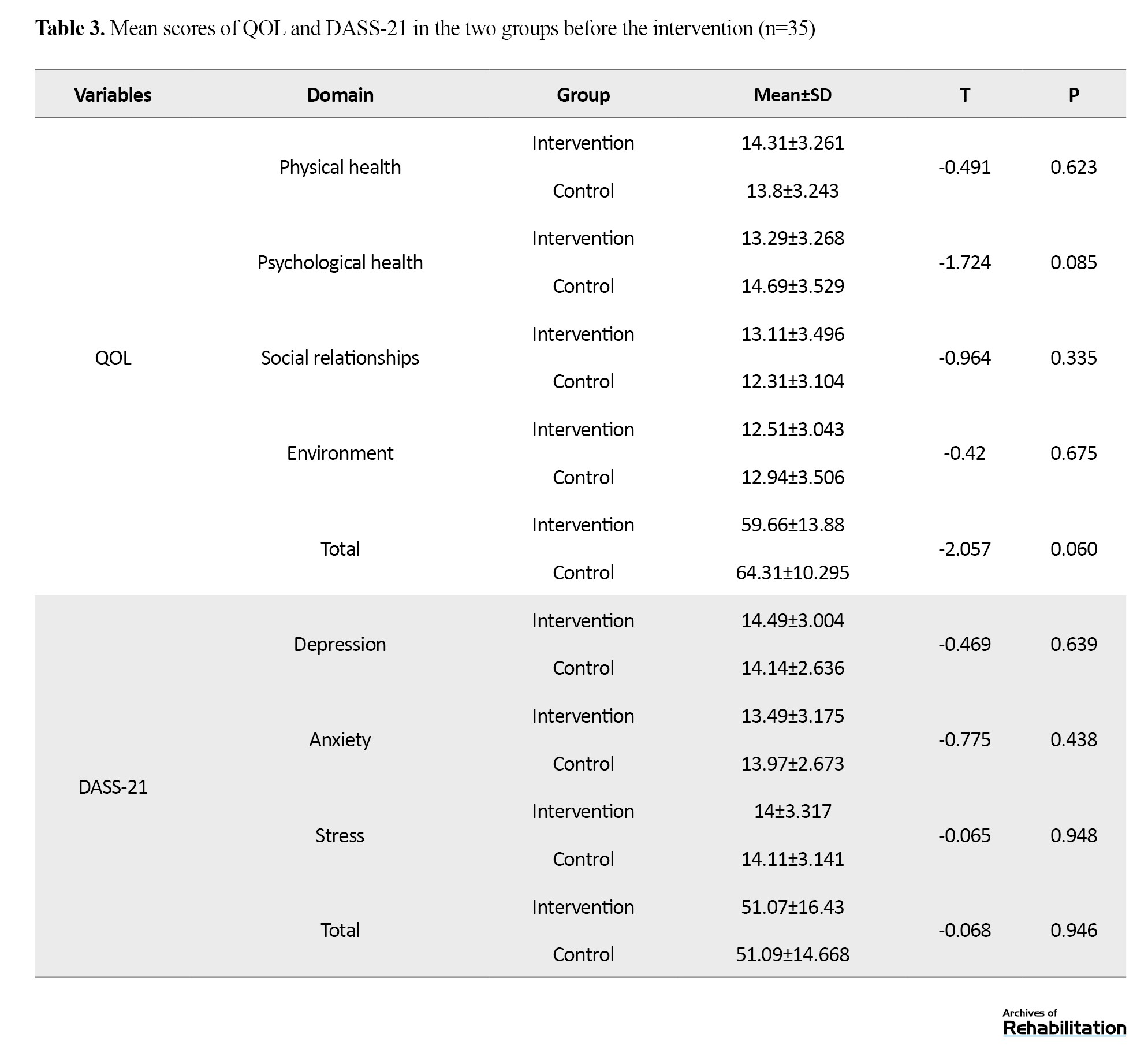

Based on the results in Table 3, the Mann-Whitney U test results showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the scores of QOL and DASS-21 before the intervention (P>0.05).

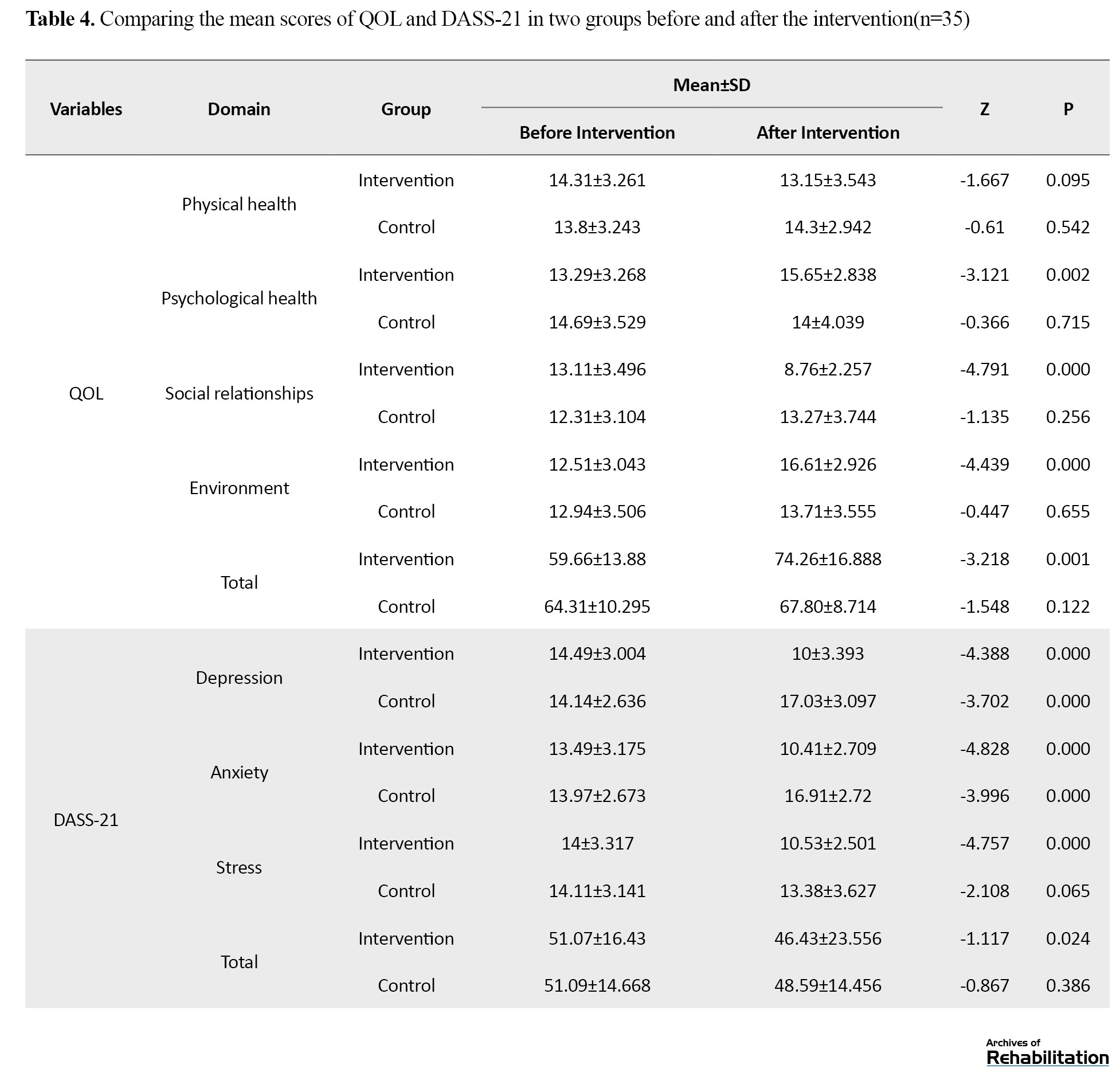

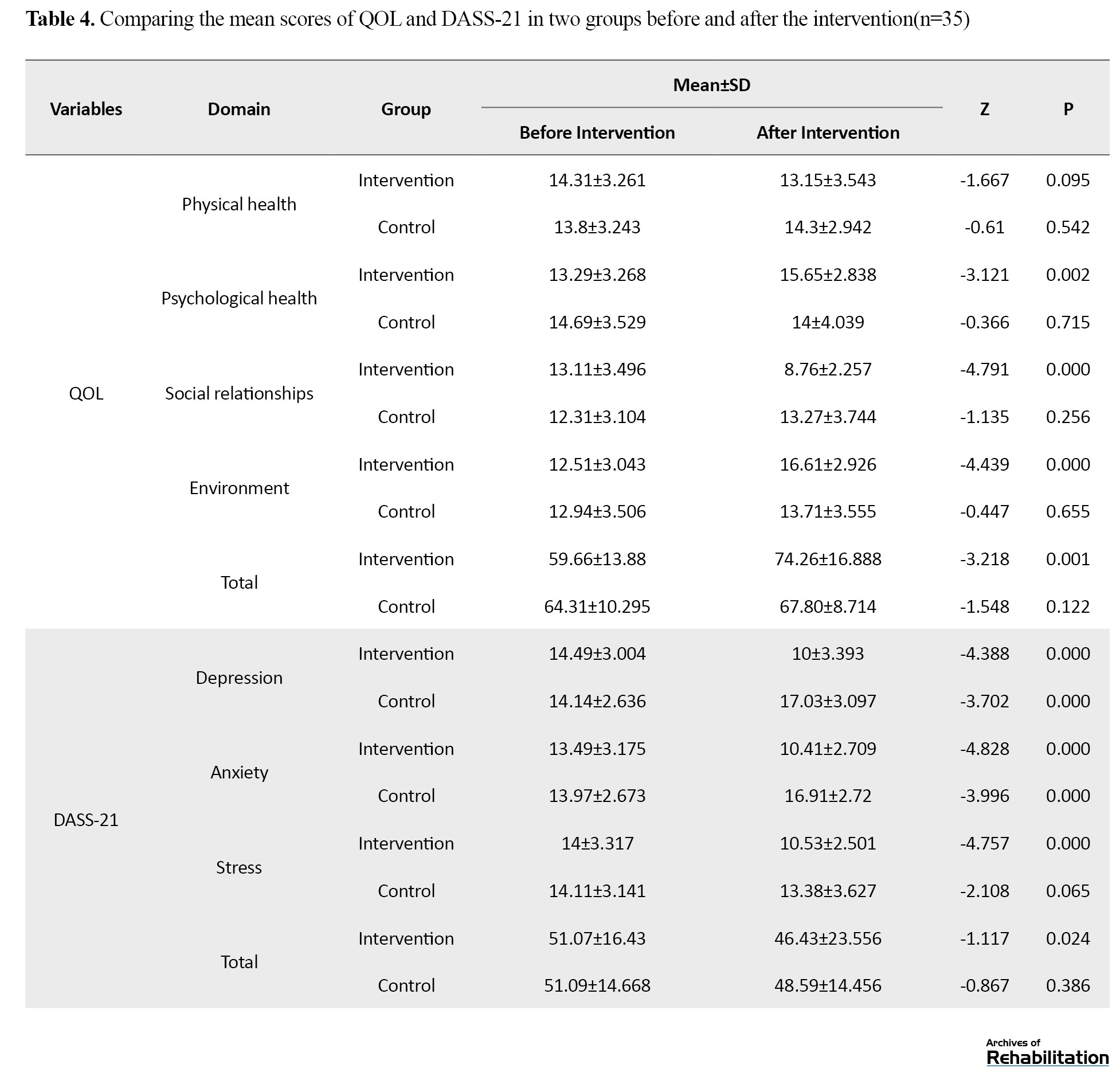

Based on the Wilcoxon test results in Table 4, in the intervention group, the early educational intervention resulted in significant increase in total QOL score (P=0.001), and in the QOL domains of psychological health (P=0.002), and environment (P<0.001) and a significant decrease in social relationships (P<0.001), but no significant change was found in the physical health domain (P=0.095).

In the control group, no significant change in any QOL domains (P>0.05). In the DASS-21 tool, the depression domain decreased significantly in the intervention group (P<0.001), but significantly increased in the control group (P<0.001). Similarly, anxiety decreased in the intervention group (P<0.001), but increased in the control group (P<0.001). Stress also significantly decreased in the intervention group (P<0.001), but did not show a significant change in the control group (P=0.065). The total DASS-21 score significantly improved in the intervention group (P=0.024), but no significant change was observed in the control group (P=0.386).

Discussion

Based on the total score of DASS-21 at baseline, the mental health of mothers of DS children in our study was severely affected, which is consistent with the results of Mesgarian et al. and Ginieri‐Coccossis et al. [26, 27]. Explaining this result, it can be said that parents of children with DS, instead of focusing on issues to improve their QOL, are more involved in concerns related to their children. These concerns lead to the neglect of mental health and the development of psychological disorders. Some parents may also feel ashamed or limit their social interactions, each of which exacerbates negative emotions and hidden anger. These factors can negatively affect the parents’ QOL [28]. The family-centered early educational intervention for mothers in our study led to improvement in the QOL domains of psychological health and environment, but the physical health domain did not change significantly, and the social health domain significantly decreased. The mothers’ depression, stress, and anxiety also significantly decreased. Our findings are consistent with the results of Milgramm et al. [29] and Darbani [19]. These studies showed that family-centered education led to improved treatment strategies, reduced mother-child conflict, and increased parental reasoning, ultimately increasing mental health and QOL. Wakimizu et al. showed that family empowerment had a significant relationship with increased QOL [30].

The non-significant change in the physical dimension after intervention may be due to the short follow-up period, the need for specialized examination, or the clinical course of physical problems. On the other hand, reducing mothers’ physical symptoms requires more focus on cognitive and behavioral skills such as stress management training, anger management training, problem-solving, etc. Early interventions do not solely focus on skill training [31]. Also, it is important to note that 21.2% of the mothers in our study had chronic illnesses. Also, their mean age was 35.4 years, and the socio-economic status of most families was unstable, which may contribute to the occurrence or exacerbation of physical problems [32].

Providing support to families of DS children and helping them realize they are not alone in their challenges can alleviate the psychological pressure on mothers [33, 34]. Early interventions often offer emotional, social, and informational support to families, which in turn helps reduce maternal anxiety [35]. Also, group counseling and contact with mothers who are in a similar situation can improve mothers’ attitudes towards life, towards the children with physical disabilities, and towards the people and environment, and increase their self-esteem, thereby reducing their anxiety [36]. In the early interventions, the goal is to help mothers become familiar with various ways of receiving support, share their experiences with others, and learn to support each other in various fields, which can ultimately lead to their less isolation and higher social functioning [37]. In this study, the QOL domain of social relationships decreased after intervention in mothers. Mothers of DS children often have poor marital satisfaction, poor expression of emotions, poor adaptation, and family cohesion compared to mothers of normal children [38]. The results of Nejad et al. [39], who examined the perceptions and feelings of mothers with DS children, suggested that, since children with DS spend more time with their mothers, it reduces marital satisfaction and the expression of love between couples. In these families, due to reasons such as family demands, low family budget, and communication problems, multiple and simultaneous interventions are required. Therefore, it should not be expected that early intervention alone can improve all dimensions of QOL. On the other hand, the fathers and other family members were not the target of intervention and less attention was paid to their expectations and perspectives, which may have changed the mothers’ perspectives and declined their social relationships. On the other hand, economic instability and financial problems can affect the effectiveness of interventions, especially in the social domain. There is a need to pay attention to the social and economic conditions of families in the design of early educational programs [40].

Overall, it can be claimed that family-centered early intervention at four face-to-face sessions leads to improved QOL and mental health in mothers of DS children. In Fallahi et al.’s study, 10 sessions for family empowerment intervention were recommended [41], but positive results were obtained with a shorter duration and lower cost in our study, using educational booklets. It seems that the effectiveness of the intervention in our study was due to adapting the educational content to the specific problems of mothers and focusing on the abilities and strengths of families, as well as the introduction of social support methods at various levels. Telephone follow-ups and face-to-face sessions might also be other factors that increased mothers’ motivation to perform exercises and turn them into a routine in their daily lives. This approach may also be used as an effective model for other target groups.

Conclusion

The family-centered early educational intervention using the designed booklet may have a positive impact on the QOL (particularly in the psychological and environmental health domains) and mental health (reducing depression, anxiety, and stress) in mothers of children with DS in Iran. However, for improving the physical health and social relationships domains of QOL in mothers, longer intervention duration or the use of other interventions such as psychological support, behavioral therapy, and problem-solving strategies may be needed. Therefore, it is recommended that in future studies, skill-based and problem-solving techniques should also be used and their effectiveness compared. Also, more educational booklets should be designed for the families of children with other disorders. The early educational intervention is recommended for the caregivers of children with DS in treatment or rehabilitation centers.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1396.308). This study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), Tehran, Iran (Code: IRCT20181117041673N1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the research process was fully explained to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Sahar Sadeghi and Houshang Mirzaei; Methodology and data analysis: Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh and Saeed Fatorehchi; Data collection: Zahra Qayumi; Resources: Sahar Sadeghi and Bahman Sadeghi; Writing: Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and management of the Aseman-e Nili DS Center, Isfahan, Iran, and all participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common chromosomal abnormality in live births, leading to difficulties in mental functioning and adaptation in conceptual, social, and practical areas during growth and development. Most children with DS have mild to moderate intellectual disabilities. These children experience delays in various aspects of development, including sensory-motor, cognitive, and psychosocial aspects. These delays cause significant limitations in activities such as dressing, eating, functional movement, play, or school attendance. Therefore, these children need more care. In most cases, mothers are responsible for the care of their DS children [1, 2]. Mothers need to spend more time on feeding and taking the child to medical or rehabilitation centers. This causes their lifestyle to be affected by the needs of their children [3], which influences other family members. Mothers may neglect their own interests and other children. They have to spend less time on social, leisure, and sports activities, and have less time to sleep and rest [4]. These challenges cause severe stress in mothers, and who often do not receive enough therapeutic, economic, and welfare support [5]. As a result, they have lower mental health and quality of life (QOL) compared to mothers with normally developed children [6]. The QOL is influenced by individuals’ perceptions of culture, values, goals, standards, and priorities that are not visible to others, and is based on their perceptions of various aspects of life [7]. Mental health refers to the ability to communicate properly with others, modify the individual and social environment, and solve personal conflicts logically, fairly, and appropriately [8]. Several studies have shown lower mental health and QOL in parents, especially mothers, of children with DS than in mothers with normal children [9, 10].

The disruption of psychological health and QOL in mothers has a negative impact on the development process of their children and other family members and may make the family enter into a vicious cycle. Therefore, rehabilitation and educational interventions to effectively support DS children and their families should be done simultaneously. Research has shown that such interventions should consider the family as a unit, rather than focusing solely on the child. Family-centered interventions take this feature into account [11]. In family-centered interventions, the main approach is to help families whose children have developmental delays. Instead of focusing on shortcomings, these interventions emphasize the family’s abilities and give them more decision-making power. This approach is sensitive to the complexities in the family and responds to the priorities. It also supports caregiving behaviors that help the child’s growth and learning [12].

One type of family-centered intervention is early intervention, which refers to both patient-centered and family-centered concepts. The primary goal of early interventions is to enhance the awareness and developmental adaptation of families and children. This goal is pursued by identifying and reducing parental stress and introducing appropriate support systems. The early intervention is coordinated with the family’s needs and leads to a reduction in focus on the child and an increase in focus on the family [13]. In other words, early intervention is a support/educational system that helps the child and their family from birth or after the diagnosis of developmental disorders in children. Various studies have shown that the effects of early interventions include reduced complications, shorter time spent, lower costs, and greater efficiency. These interventions also help to correct the functional norms and executive function of children [14]. It has been determined that the use of appropriate and early support/educational interventions for parents of children with DS leads to improved self-confidence and child care quality [15]. For example, the studies by Hosseinali Zade et al. and Tomris et al. on the effect of early interventions on families of children with DS showed that parents gained a better understanding of their child’s strengths and abilities and were more optimistic about the future [16, 17]. Also, Brian et al. showed that a parent-mediated intervention improved parents’ use of treatment strategies and reduced their stress [18].

Considering that children’s physical disabilities lead to parental fatigue and occurrence of psychological problems such as anxiety, depression, family tension, marital dissatisfaction, and social problems, and since children’s growth is closely related to their parents’ physical and mental health, psychological stress in parents affects their function and, consequently, the children’s growth [19]. On the other hand, considering the increasing prevalence of DS and the associated problems and challenges for families, the need for early interventions for them is felt. These interventions should be accessible and inexpensive. It seems that if the early interventions are provided through a booklet, it can be more cost-effective [20]. However, the impact of early intervention using this technique on various aspects of parents’ lives, especially their mental health and QOL, has been less studied. Therefore, this study aims to assess the effect of a family-centered early educational intervention on the psychological symptoms (depression, anxiety, stress) and QOL of mothers of children with DS.

Materials and Methods

Participants

This is a single-blind randomized clinical trial conducted during 2022-2023. The study population consists of mothers of children with DS referred to the Aseman-e Nili DS center in Isfahan, Iran. The required sample size for each group was determined 32 using Equation 1, considering σ1=2.46, σ2=2.78, and a mean difference (d) of 1.84 according to Faramarzi and Malekpour’s study [21] on the impact of early intervention on the mental health of mothers of DS children, and a 95% confidence interval (CI), and 80% test power. Considering the potential sample dropout, the sample size for each group increased to 35.

Inclusion criteria were having a child with DS, child’s age 6-72 months, child being cared for at home, mothers’ willingness to participate in the study, a general health questionnaire-28 item (GHQ-28) score >23, mother’s ability to read, understand, and answer questions, no severe medical abnormalities and problems, including orthopedic disorders, seizures, uncontrolled thyroid disorders, congenital heart defects requiring surgery, no severe visual or hearing impairments, or a history of neonatal infection (meningitis and encephalitis), and having no other child with a chronic illness, including DS. Exclusion criteria were: Absence from one of the four educational sessions, diagnosis of a mental or physical illness requiring medication or surgical intervention during the three-month intervention period, mothers’ lack of cooperation in performing exercises in more than 10% of the intervention program, and family disruption or divorce/separation during the study.

After obtaining the ethics code from the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences in Tehran, and referring to the Isfahan DS Association and the Aseman-e Nili Center, 115 mothers were selected from a list using simple random sampling based on a random number table. They were asked to complete the GHQ-28. Those who scored higher than 23 and met the inclusion criteria were selected [22]. After matching for mother’s age, child’s age, care hours, and socio-economic status, they were randomly divided into two groups of 35 including intervention and control groups, by the coin toss method. The heads were assigned to the intervention group and the tails to the control group.

Instruments

The GHQ-28, designed by Goldberg in 1997, was used to screen for mental health issues. Its Persian version has good validity and reliability. It has a test re-test reliability, split-half reliability, and Cronbach’s α coefficients of 0.70, 0.93, and 0.90, respectively. The GHQ-28 has four subscales: Somatic symptoms, anxiety/insomnia, social dysfunction, and severe depression, each containing seven items rated on a 4-point Likert scale: Not at all, no more than usual, rather more than usual, and much more than usual. The total score ranges from 0 to 84, with lower scores indicating better general health. A score of 23 is considered a threshold for unfavorable general health [23].

The depression, anxiety, and stress scale (DASS-21), developed by Lovibond in 1995, was used to measure the mental health of mothers. It is a 21-item self-report scale for assessing depression, anxiety, and stress. For the Persian version, Samani and Joukar reported a test re-test reliability of 0.80, 0.76, and 0.77, and Cronbach’s α values of 0.81, 0.74, and 0.78 for the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales, respectively [24].

The World Health Organization QOL scale (WHOQOL-BREF) was used to measure the QOL of mothers. This 26-item questionnaire measures four domains of QOL: Physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment. It uses a 5-point Likert scale from 1 to 5 (not at all, not much, moderately, very much, and completely). The total score of each domain ranges from 4 to 20, with higher scores indicating better QOL. This tool was validated in Iran by Nejat et al. In their study, test re-test reliability for the subscales was 0.77, 0.77, 0.75, and 0.84 for physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environment, respectively. Cronbach’s α values for the subscales were the same, indicating the acceptable internal consistency of the WHOQOL-BREF for the Iranian population [25].

Intervention

The educational intervention was provided using a 75-page booklet with a preface and three chapters [26]. In the preface section, information about DS, the care needs of children with DS and the problems of their parents, how to identify family strengths, how to make decisions and determine family priorities, how to increase the awareness and adaptation of all family members, support systems, and the definition and effects of early interventions are discussed. The first chapter focuses on sensory adjustment and the development of appropriate communication skills, including practical exercises. The second chapter focuses on gross and fine motor skills, including practical exercises designed to enhance these skills. The third chapter discusses how to utilize the child’s abilities and enhance their independence in performing daily living activities. Table 1 lists the contents of each chapter.

This booklet presents the desired exercises in the form of daily living activities, and also mentions the appropriate age for acquiring each skill, and provides the necessary exercises for each skill, in order. The exercises are shown with a photo, making it easy for mothers to implement them in their daily lives. An example of an exercise to improve visual memory while cooking is given below: “While cooking, ask the child to look at the objects on the table, then close their eyes and pick up an object and ask them to name the object that is no longer on the table.”

In the intervention group, four one-hour individual educational sessions were held. In each session, one chapter of the booklet, as well as early educational techniques and assignments, were presented to the mothers. The content of each chapter and the assignments were fully explained. To ensure the mothers’ learning, they performed several exercises in the presence of a therapist. The intervention was designed to reduce the stress of mothers with DS children, considering the challenges they face in teaching their children. Given the time constraints of mothers, the content required minimal instruction and was presented in a self-help format. During these sessions, each mother learned how to implement each exercise practically, and checklists were completed weekly by mothers for continuous follow-up. They should record the date of each day they completed the exercises and specify the chapter of the booklet used. They also noted any challenges they encountered while performing the exercise and shared them with the researcher when they handed in the checklist. After the intervention, the mothers were followed up for 3 months. Follow-ups were conducted weekly via telephone calls to guide them if problems arose. The mothers could contact the researcher at any time if they needed more consultation. Some days, the researcher was present at the center to answer the mothers’ potential questions and collect the completed weekly checklists. The average follow-up time for mothers was 97 days. The control group received only their usual treatments, including occupational therapy, speech therapy, and behavioral therapy, in the DS association. Also, in cooperation with the DS association, regular occupational therapy and speech therapy classes were held for the mothers in the control group. After the end of the intervention, all mothers in the control group were informed about the results of the study.

Data analysis

The data were collected before and after the intervention. After examining the normality of data distribution using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, descriptive and inferential statistical methods, including the Mann-Whitney U test, the Wilcoxon test, and the chi-square test, were used for data analysis in SPSS software, version 21.

Results

The mean age of mothers was 35.4±1.8 years, and the mean age of children was 33.8±14.8 months. Among 70 mothers, 91.9% were living with their spouses, and 8.1% were living without a spouse. Also, 76.6% were housewives, 44.4% had a high school diploma or lower education, and 42.4% had a monthly income of 8-12 million Tomans. Based on the chi-square test results shown in Table 2, there was no statistically significant difference between the control and intervention groups regarding the sociodemographic factors (P>0.05).

Based on the results in Table 3, the Mann-Whitney U test results showed no statistically significant difference between the two groups in the scores of QOL and DASS-21 before the intervention (P>0.05).

Based on the Wilcoxon test results in Table 4, in the intervention group, the early educational intervention resulted in significant increase in total QOL score (P=0.001), and in the QOL domains of psychological health (P=0.002), and environment (P<0.001) and a significant decrease in social relationships (P<0.001), but no significant change was found in the physical health domain (P=0.095).

In the control group, no significant change in any QOL domains (P>0.05). In the DASS-21 tool, the depression domain decreased significantly in the intervention group (P<0.001), but significantly increased in the control group (P<0.001). Similarly, anxiety decreased in the intervention group (P<0.001), but increased in the control group (P<0.001). Stress also significantly decreased in the intervention group (P<0.001), but did not show a significant change in the control group (P=0.065). The total DASS-21 score significantly improved in the intervention group (P=0.024), but no significant change was observed in the control group (P=0.386).

Discussion

Based on the total score of DASS-21 at baseline, the mental health of mothers of DS children in our study was severely affected, which is consistent with the results of Mesgarian et al. and Ginieri‐Coccossis et al. [26, 27]. Explaining this result, it can be said that parents of children with DS, instead of focusing on issues to improve their QOL, are more involved in concerns related to their children. These concerns lead to the neglect of mental health and the development of psychological disorders. Some parents may also feel ashamed or limit their social interactions, each of which exacerbates negative emotions and hidden anger. These factors can negatively affect the parents’ QOL [28]. The family-centered early educational intervention for mothers in our study led to improvement in the QOL domains of psychological health and environment, but the physical health domain did not change significantly, and the social health domain significantly decreased. The mothers’ depression, stress, and anxiety also significantly decreased. Our findings are consistent with the results of Milgramm et al. [29] and Darbani [19]. These studies showed that family-centered education led to improved treatment strategies, reduced mother-child conflict, and increased parental reasoning, ultimately increasing mental health and QOL. Wakimizu et al. showed that family empowerment had a significant relationship with increased QOL [30].

The non-significant change in the physical dimension after intervention may be due to the short follow-up period, the need for specialized examination, or the clinical course of physical problems. On the other hand, reducing mothers’ physical symptoms requires more focus on cognitive and behavioral skills such as stress management training, anger management training, problem-solving, etc. Early interventions do not solely focus on skill training [31]. Also, it is important to note that 21.2% of the mothers in our study had chronic illnesses. Also, their mean age was 35.4 years, and the socio-economic status of most families was unstable, which may contribute to the occurrence or exacerbation of physical problems [32].

Providing support to families of DS children and helping them realize they are not alone in their challenges can alleviate the psychological pressure on mothers [33, 34]. Early interventions often offer emotional, social, and informational support to families, which in turn helps reduce maternal anxiety [35]. Also, group counseling and contact with mothers who are in a similar situation can improve mothers’ attitudes towards life, towards the children with physical disabilities, and towards the people and environment, and increase their self-esteem, thereby reducing their anxiety [36]. In the early interventions, the goal is to help mothers become familiar with various ways of receiving support, share their experiences with others, and learn to support each other in various fields, which can ultimately lead to their less isolation and higher social functioning [37]. In this study, the QOL domain of social relationships decreased after intervention in mothers. Mothers of DS children often have poor marital satisfaction, poor expression of emotions, poor adaptation, and family cohesion compared to mothers of normal children [38]. The results of Nejad et al. [39], who examined the perceptions and feelings of mothers with DS children, suggested that, since children with DS spend more time with their mothers, it reduces marital satisfaction and the expression of love between couples. In these families, due to reasons such as family demands, low family budget, and communication problems, multiple and simultaneous interventions are required. Therefore, it should not be expected that early intervention alone can improve all dimensions of QOL. On the other hand, the fathers and other family members were not the target of intervention and less attention was paid to their expectations and perspectives, which may have changed the mothers’ perspectives and declined their social relationships. On the other hand, economic instability and financial problems can affect the effectiveness of interventions, especially in the social domain. There is a need to pay attention to the social and economic conditions of families in the design of early educational programs [40].

Overall, it can be claimed that family-centered early intervention at four face-to-face sessions leads to improved QOL and mental health in mothers of DS children. In Fallahi et al.’s study, 10 sessions for family empowerment intervention were recommended [41], but positive results were obtained with a shorter duration and lower cost in our study, using educational booklets. It seems that the effectiveness of the intervention in our study was due to adapting the educational content to the specific problems of mothers and focusing on the abilities and strengths of families, as well as the introduction of social support methods at various levels. Telephone follow-ups and face-to-face sessions might also be other factors that increased mothers’ motivation to perform exercises and turn them into a routine in their daily lives. This approach may also be used as an effective model for other target groups.

Conclusion

The family-centered early educational intervention using the designed booklet may have a positive impact on the QOL (particularly in the psychological and environmental health domains) and mental health (reducing depression, anxiety, and stress) in mothers of children with DS in Iran. However, for improving the physical health and social relationships domains of QOL in mothers, longer intervention duration or the use of other interventions such as psychological support, behavioral therapy, and problem-solving strategies may be needed. Therefore, it is recommended that in future studies, skill-based and problem-solving techniques should also be used and their effectiveness compared. Also, more educational booklets should be designed for the families of children with other disorders. The early educational intervention is recommended for the caregivers of children with DS in treatment or rehabilitation centers.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1396.308). This study was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT), Tehran, Iran (Code: IRCT20181117041673N1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, and the research process was fully explained to them.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Sahar Sadeghi and Houshang Mirzaei; Methodology and data analysis: Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh and Saeed Fatorehchi; Data collection: Zahra Qayumi; Resources: Sahar Sadeghi and Bahman Sadeghi; Writing: Bahman Sadeghi Sedeh.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff and management of the Aseman-e Nili DS Center, Isfahan, Iran, and all participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

- Pelosi MB, Ferreira KG, Nascimento JS. Occupational therapy activities developed with children and pre-teens with Down syndrome. Cadernos Brasileiros de Terapia Ocupacional, 2020; 28(2):511-24. [DOI:10.4322/2526-8910.ctoAO1782]

- Do Amaral CO, Tomasella CM, Lourencetti IS, Do Amaral MO, Straioto FG. Down syndrome-trisomy of chromosome 21: Medical considerations, physiological, and oral health perspectives. Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal. 24(1):1-8. [Link]

- Abbeduto L, Seltzer MM, Shattuck P, Krauss MW, Orsmond G, Murphy MM. Psychological well-being and coping in mothers of youths with autism, Down syndrome, or fragile X syndrome. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 2004; 109(3):237-54. [DOI:10.1352/0895-8017(2004)1092.0.CO;2] [PMID]

- Estes A, Munson J, Dawson G, Koehler E, Zhou XH, Abbott R. Parenting stress and psychological functioning among mothers of preschool children with autism and developmental delay. Autism. 2009; 13(4):375-87. [DOI:10.1177/1362361309105658] [PMID]

- Siklos S, Kerns KA. Assessing need for social support in parents of children with autism and Down syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2006; 36(7):921-33. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-006-0129-7] [PMID]

- McIntyre LL, Blacher J, Baker BL. Behaviour/mental health problems in young adults with intellectual disability: The impact on families. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2002; 46(Pt 3):239-49. [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2788.2002.00371.x] [PMID]

- Macedo EC, da Silva LR, Paiva MS, Ramos MN. Burden and quality of life of mothers of children and adolescents with chronic illnesses: An integrative review. Revista Latino-Americana De Enfermagem. 2015; 23(4):769-77. [DOI:10.1590/0104-1169.0196.2613] [PMID]

- Solgi Z, Saeedipoor B, Abdolmaleki P. Study of psychological well-being of physical education students of Razi university of Kermanshah. Journal of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences. 2009; 13(2):e79805. [Link]

- Lee A, Knafl G, Knafl K, Van Riper M. Parent-reported contribution of family variables to the quality of life in children with down syndrome: Report from an international study. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2020; 55:192-200. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2020.07.009] [PMID]

- Lee EY, Neil N, Friesen DC. Support needs, coping, and stress among parents and caregivers of people with Down syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2021; 119:104113. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104113] [PMID]

- Walker BJ, Washington L, Early D, Poskey GA. Parents' experiences with implementing therapy home programs for children with down syndrome: A scoping review. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2020; 34(1):85-98. [DOI:10.1080/07380577.2020.1723820] [PMID]

- Na E. Cochlear implants for children with residual hearing: Supporting family decision-making [doctoral thesis]. Ottawa: University of Ottawa; 2021. [Link]

- Hoare P, Harris M, Jackson P, Kerley S. A community survey of children with severe intellectual disability and their families: psychological adjustment, carer distress and the effect of respite care. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 1998; 42( Pt 3):218-27. [DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2788.1998.00134.x] [PMID]

- Ramey CT, Ramey SL. Early intervention and early experience. The American Psychologist. 1998; 53(2):109-20. [DOI:10.1037//0003-066X.53.2.109] [PMID]

- Pashazadeh Azari Z, Hosseini SA, Rassafiani M, Samadi SA, Hoseinzadeh S, Dunn W. Contextual intervention adapted for autism spectrum disorder: An RCT of a parenting program with parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Iranian Journal of Child Neurology. 2019; 13(4):19-35. [PMID]

- Hosseinali Zade M, Faramarzi S, Abedi A. The effectiveness of child-centered neuropsychological early interventions package on cognitive and social performance of children with developmental delay. Educational Psychology. 2022; 18(65):43-64. [DOI:10.22054/jep.2023.34719.2361]

- Tomris G, Celik S, Diken IH, Akemoğlu Y. Views of parents of children with down syndrome on early intervention services in Turkey: Problems, expectations, and suggestions. Infants & Young Children. 2022; 35(2):120-32. [DOI:10.1097/IYC.0000000000000212]

- Brian J, Drmic I, Roncadin C, Dowds E, Shaver C, Smith IM, et al. Effectiveness of a parent-mediated intervention for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder: Evidence from a large community implementation. Autism. 2022; 26(7):1882-97. [DOI:10.1177/13623613211068934] [PMID]

- Darbani SA, Parsakia K. The effectiveness of strength-based counseling on the reduction of divorced women's depression. Journal of Assessment and Research in Applied Counseling. 2022; 4(1):64-76. [DOI:10.61838/kman.pwj.3.1.5]

- Alibakhshi H, Ayoubi Avaz K, Azani Z, Ahmadizadeh Z, Siminghalam M, Tohidast SA. Investigating the caregiver burden and related factors in parents of 4 to 12 years old children with down syndrome living in Tehran City, Iran, in 2020. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2022; 23(3):434-49. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.23.3.3407.1]

- Faramarzi S, Malekpour M. [The effects of educational and psychological family-based early intervention on the motor development of children with Down syndrome (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation, 2009; 10(1):24-31. [Link]

- Zare N, Parvareh M, Noori B, Namdari M. [Mental health status of Iranian university students using the GHQ-28: A meta-analysis (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Kurdistan University of Medical Sciences. 2016; 21(4):1-6. [Link]

- Sterling M. General health questionnaire - 28 (GHQ-28). Journal of Physiotherapy. 2011; 57(4):259. [DOI:10.1016/S1836-9553(11)70060-1] [PMID]

- Samani S, Joukar B. [A study on the reliability and validity of the short form of the depression anxiety stress scale (DASS-21) (Persian)]. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 2007; 3(52):65-77. [Link]

- Nejat SA, Montazeri A, Holakouie Naieni K, Mohammad KA, Majdzadeh SR. [The World Health Organization quality of life (WHOQOL-BREF) questionnaire: Translation and validation study of the Iranian version (Persian)]. Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research. 2006; 4(4):1-12. [Link]

- Sadeghi S, Mirzae H, Surtiji H, Sadeghi B. [Parent Guide:Guide to Occupational Therapy for Parents: In the Form of Games and Daily Activities at Home (Simple, 5-Minute Games) (Persian)]. Tehran: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences; 2020. [Link]

- Mesgarian F, Asghari MM, Shairi MR. [The role of self-efficacy in predicting catastrophic depression in patients with chronic pain (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012; 4(4):74-83. [Link]

- Ginieri-Coccossis M, Rotsika V, Skevington S, Papaevangelou S, Malliori M, Tomaras V, et al. Quality of life in newly diagnosed children with specific learning disabilities (SpLD) and differences from typically developing children: A study of child and parent reports. Child. 2013; 39(4):581-91. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2012.01369.x] [PMID]

- Payot A, Barrington KJ. The quality of life of young children and infants with chronic medical problems: Review of the literature. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care. 2011; 41(4):91-101. [DOI:10.1016/j.cppeds.2010.10.008] [PMID]

- Milgramm A, Corona LL, Janicki-Menzie C, Christodulu KV. Community-based parent education for caregivers of children newly diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2022; 52(3):1200-10. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-021-05025-5] [PMID]

- Wakimizu R, Fujioka H, Nishigaki K, Matsuzawa A. Quality of life and associated factors in siblings of children with severe motor and intellectual disabilities: A cross-sectional study. Nursing & Health Sciences. 2020; 22(4):977-87. [DOI:10.1111/nhs.12755] [PMID]

- Nematollahi M, Tahmasebi S. [The effectiveness of parents’ skills training program on reducing children’s behavior problems (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2014; 10(2):159-74. [Link]

- Parand A, Movallali G. [The effect of teaching stress management on the reduction of psychological problems of families with children suffering from hearing-impairment (Persian)]. Journal of Family Research. 2011; 7(1):23-34. [Link]

- Iravani M, Hatamizadeh N, Fotouhi A, Hosseinzadeh S. [Comparing effectiveness of new training program of local trainers of Community-Based Rehabilitation program with the current program: A knowledge, attitude and skills study (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2011; 12(3):44-52. [Link]

- Abdollahi Mehraban N, Shafiabadi A, Behboodi M. [Effectiveness of group counseling with a reality therapy approach on increasing self esteem of mothers with cerebral palsy (CP) (Persian)]. Research on Behavioral Science. 2014; 3(37):60-8. [Link]

- Sadeghi S, Sadeghi SB, Mirzaee H, Rasafiani M, Pishyareh E. [Translating and standardizing the Persian version measure of process of care for service providers (MPOC-SP) in down syndrome (Persian)]. Journal of Advanced Biomedical Sciences. 2020; 9(4):1870-8. [Link]

- Halstead EJ, Griffith GM, Hastings RP. Social support, coping, and positive perceptions as potential protective factors for the well-being of mothers of children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 2017; 64(4-5):288-96. [DOI:10.1080/20473869.2017.1329192] [PMID]

- Byrne MB, Hurley DA, Daly L, Cunningham CG. Health status of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy. Child. 2010; 36(5):696-702. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.01047.x] [PMID]

- Senses Dinc G, Cop E, Tos T, Sari E, Senel S. Mothers of 0-3-year-old children with Down syndrome: Effects on quality of life. Pediatrics International. 2019; 61(9):865-71. [DOI:10.1111/ped.13936] [PMID]

- Nejad RK, Afrooz G, Shokoohi-Yekta M, Bonab BG, Hasanzadeh S. [Lived experience of parents of infants with down syndrome from early diagnosis and reactions to child disability (Persian)]. The Journal of Tolooebehdasht. 2020; 19(3):12-31. [DOI:10.18502/tbj.v19i3.4170]

- Fallahi F, Hemati Alamdarloo G. [Effectiveness of psychological empowerment on general health of mothers of children with disability under the community-based rehabilitation program (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2019; 19(4):326-39. [DOI:10.32598/rj.19.4.326]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 1/10/2024 | Accepted: 24/05/2025 | Published: 1/10/2025

Received: 1/10/2024 | Accepted: 24/05/2025 | Published: 1/10/2025

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |