Volume 25, Issue 4 (Winter 2025)

jrehab 2025, 25(4): 766-789 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hosseini Zare S M, Babapour J, Hosseini Zare S M, Sadr A S, Hosseini M S, Khorasani B. Quality of Work Life Among Nurses in Hospitals Affiliated With the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences: A Cross-sectional Study. jrehab 2025; 25 (4) :766-789

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3457-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3457-en.html

Seyedeh Mahboobeh Hosseini Zare1

, Jafar Babapour2

, Jafar Babapour2

, Seyedeh Masoumeh Hosseini Zare3

, Seyedeh Masoumeh Hosseini Zare3

, Ahmad Siar Sadr4

, Ahmad Siar Sadr4

, Maryam Sadat Hosseini5

, Maryam Sadat Hosseini5

, Bijan Khorasani *6

, Bijan Khorasani *6

, Jafar Babapour2

, Jafar Babapour2

, Seyedeh Masoumeh Hosseini Zare3

, Seyedeh Masoumeh Hosseini Zare3

, Ahmad Siar Sadr4

, Ahmad Siar Sadr4

, Maryam Sadat Hosseini5

, Maryam Sadat Hosseini5

, Bijan Khorasani *6

, Bijan Khorasani *6

1- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Social Health Research Institute, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Sciences, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. Tehran. Iran.

3- Sabzevar Health Care Center, Deputy of Health, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran.

4- Deputy of Research and Technology, Sharif University of Technology, Tehran. Iran.

5- Department of R&D, Eagle Analytical Services, Houston, United States.

6- Department of Clinical Sciences, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,bkhorasany@hotmail.com

2- Department of Clinical Sciences, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. Tehran. Iran.

3- Sabzevar Health Care Center, Deputy of Health, Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences, Sabzevar, Iran.

4- Deputy of Research and Technology, Sharif University of Technology, Tehran. Iran.

5- Department of R&D, Eagle Analytical Services, Houston, United States.

6- Department of Clinical Sciences, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 2737 kb]

(1258 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5419 Views)

Full-Text: (1208 Views)

Introduction

Nurses play essential roles in the healthcare system; therefore, their job satisfaction and performance are crucial for the success of hospitals [1]. Nurses’ work-life quality significantly influences their well-being, work experiences, and ability to meet job demands and maintain their mental health [2]. This issue, in turn, influences their job satisfaction and decisions regarding whether to remain in or leave their positions, making it a key factor in shaping organizational behavior, which can lead to job dissatisfaction and burnout when there are problems or shortages in this area [3, 4]. Work-life quality also plays an essential role in satisfaction with other dimensions of life, such as family, leisure, and health [5].

Nurses often work under challenging conditions such as sleep deprivation, high stress, and multiple responsibilities. These factors can negatively affect their mood, behavior, social interactions, overall quality of life, learning capacity, decision-making, and the care they provide to patients [6]. Additionally, nurse shortages, low income, job abandonment, and migration to other countries further reduce their quality of care. Therefore, improving nurses’ work-life quality is essential to attracting and retaining them [7]. Hospitals with low work-life quality face higher rates of job abandonment and absenteeism, while improvements in this area lead to better performance, reduced absenteeism, and lower stress levels [7, 8, 9].

The quality of life and job satisfaction of nurses is a global challenge. In 2010, around 40000 nurses left their jobs, doubling to 80000 by 2020. Ensuring a good quality of work life for nurses increases their productivity and reduces job turnover. However, many nurses still lack a satisfactory work-life quality [10]. In the Gulf region, studies show widespread dissatisfaction among nurses. For example, Al-Maskari et al. found that nurses in Oman generally experience a moderate quality of work life [11]. Similarly, Oweidat et al. reported moderate levels of work quality in Jordan [12]. Kaddourah et al. reported that over half of the nurses working in two healthcare institutions in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, were unsatisfied with their work life, with 94% considering leaving their jobs [13]. In Iran, research by Mohammadi et al. reveals that two-thirds of nurses are dissatisfied with their quality of work life [14], with another study indicating that 74.5% of nurses share this dissatisfaction [15].

The University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences oversees two unique hospitals. Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital is the only rehabilitation hospital in the country, providing services to patients who need rehabilitation for brain injury, spinal cord injury, stroke, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and other disabling sensory and motor diseases. The largest psychiatric hospital in the Middle East is Razi Psychiatric Hospital, which offers psychiatric services. There are numerous challenges that nurses must deal with in these two hospitals that can impact their quality of life. Understanding the factors that affect the quality of work life for nurses in these hospitals is crucial for developing strategies to enhance motivation, job performance, and nurse retention, indirectly improving patient care quality. Assessing the work-life quality and other key factors is vital in implementing supportive policies for nurses. Given the critical role of nurses in patient health, improving their work-life quality not only enhances patient care quality but also positively impacts the entire healthcare system [16]. This study evaluated the work-life quality of nurses working at the hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Materials & Methods

This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in 2022. The research population consisted of nurses working at Razi Psychiatric and Rofeideh Rehabilitation hospitals, affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. At the time of the study, 605 nurses were employed at the two hospitals (512 nurses at Razi Psychiatric Hospital and 93 nurses at Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital).

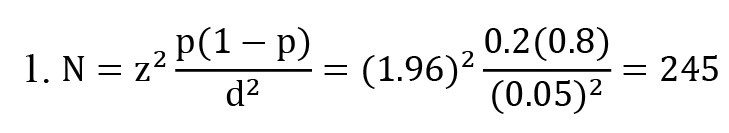

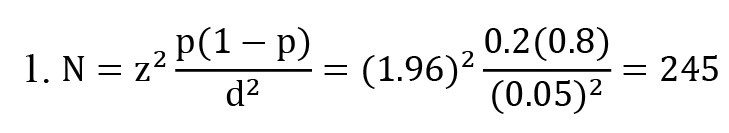

To determine the sample size, assuming that the work-life quality was very good for 20% of nurses, the equation 1 was used, resulting in a required sample size of 245:

Given an estimated response rate of 70%, 350 samples were ultimately selected.

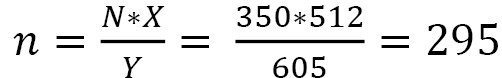

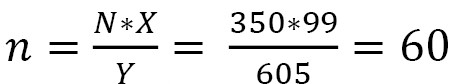

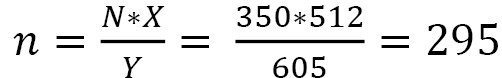

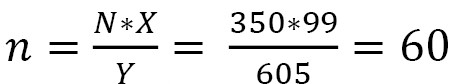

Where N is the Sample size, X refers to the nurses working in each hospital, and Y is the total nurses working in these two hospitals, the following formula estimates the number of samples selected from each hospital:

Sample size for Razi Hospital;

Sample size for Razi Hospital;

Sample size for Rofeideh Hospital;

Sample size for Rofeideh Hospital;

Samples were selected randomly from the nurses working in the two hospitals using their codes. Consequently, 253 nurses from Razi Psychiatric Hospital (85%) and 60 nurses from Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital (100%) participated in the study.

The inclusion criteria required participants to provide informed consent, hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, and have at least one year of work experience. The exclusion criteria included nurses who were ill or on leave during the data collection period.

The Richard Walton quality of work-life questionnaire (1973) was used to measure the work-life quality in this study [16]. Responses were scored using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from very low (1) to very high (5). The questionnaire also included demographic questions at the beginning. The highest possible score was 160, and the lowest was 32, with higher scores indicating a better work-life quality. This questionnaire has been used in similar studies [17-19].

The study objectives and methods for data collection were explained to four trained interviewers. After explaining the study’s objectives and ensuring confidentiality, the interviewers distributed the questionnaires to the participants. They collected the completed questionnaires the following day.

The questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section addressed demographic variables, including the hospital of employment, age, gender, marital status, education level, and work experience. The second part included 32 questions that addressed various dimensions related to work: 5 questions on fair compensation, 3 on safe working conditions, 3 on immediate opportunities for skill development, 9 on opportunities for career growth and job security, 2 on social integration within the workplace, 3 on organizational principles, 2 on balancing work and personal life, and 5 on the societal impact of work-life.

The content validity of the Walton quality of work-life questionnaire has been confirmed by experts and specialists in various studies [20-22]. The Cronbach α coefficients for the trustworthiness of the Walton quality of work-life questionnaire were 0.92 and 0.83 in Talasaz et al. and Imani et al. findings, respectively [20, 23]. For data analysis, descriptive statistics such as frequency, mean, percentage, and standard deviation were computed alongside analytical statistics, including t test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and regression, using SPSS software, version 23.

In this study, ethical principles in research, such as obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality, and respecting individuals’ privacy, were observed. This article is based on a research project titled “Exploring quality of working life in nurses working at hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences,” approved by the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Health with the ethics code IR.USWR.REC.1400.322.

Results

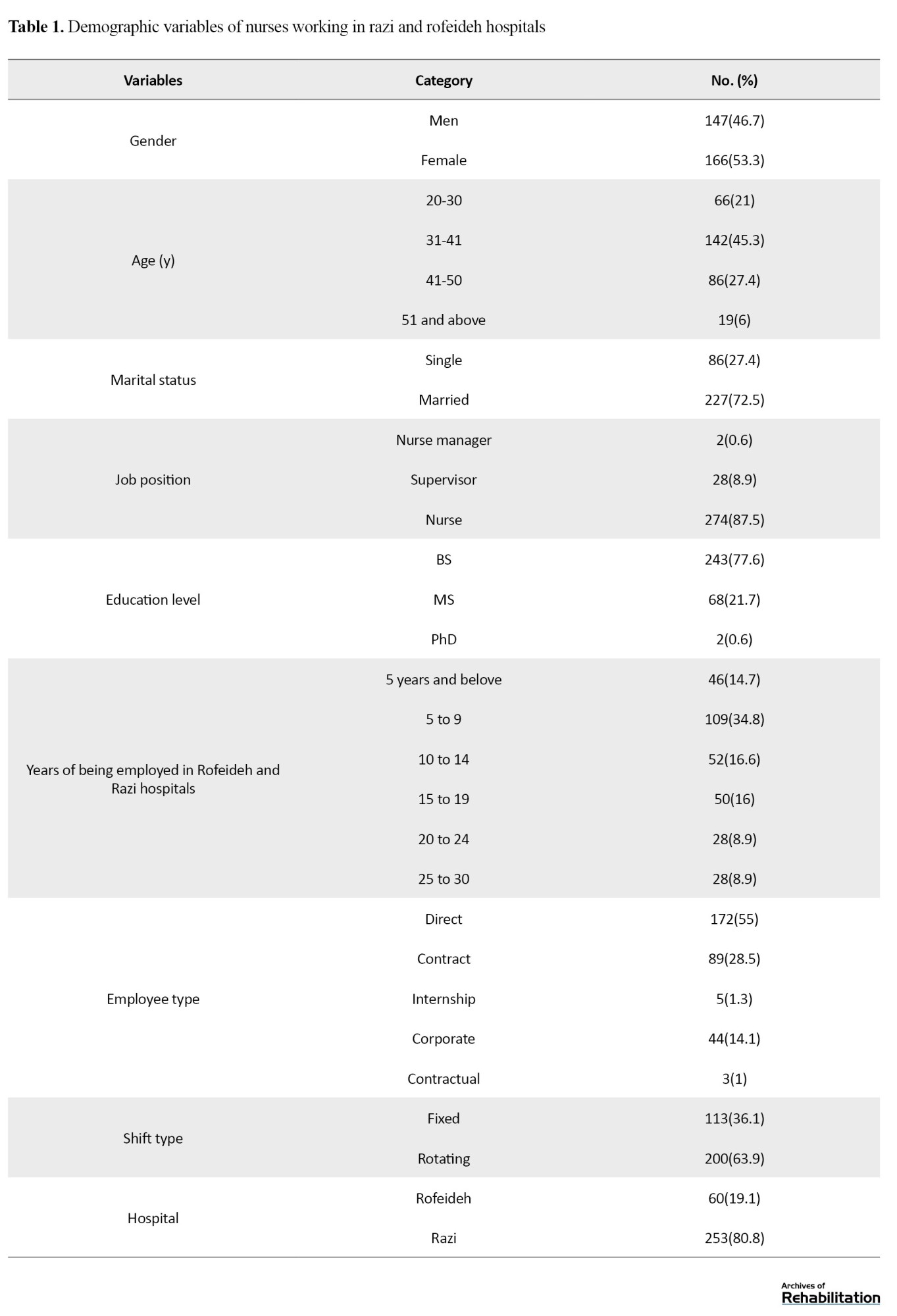

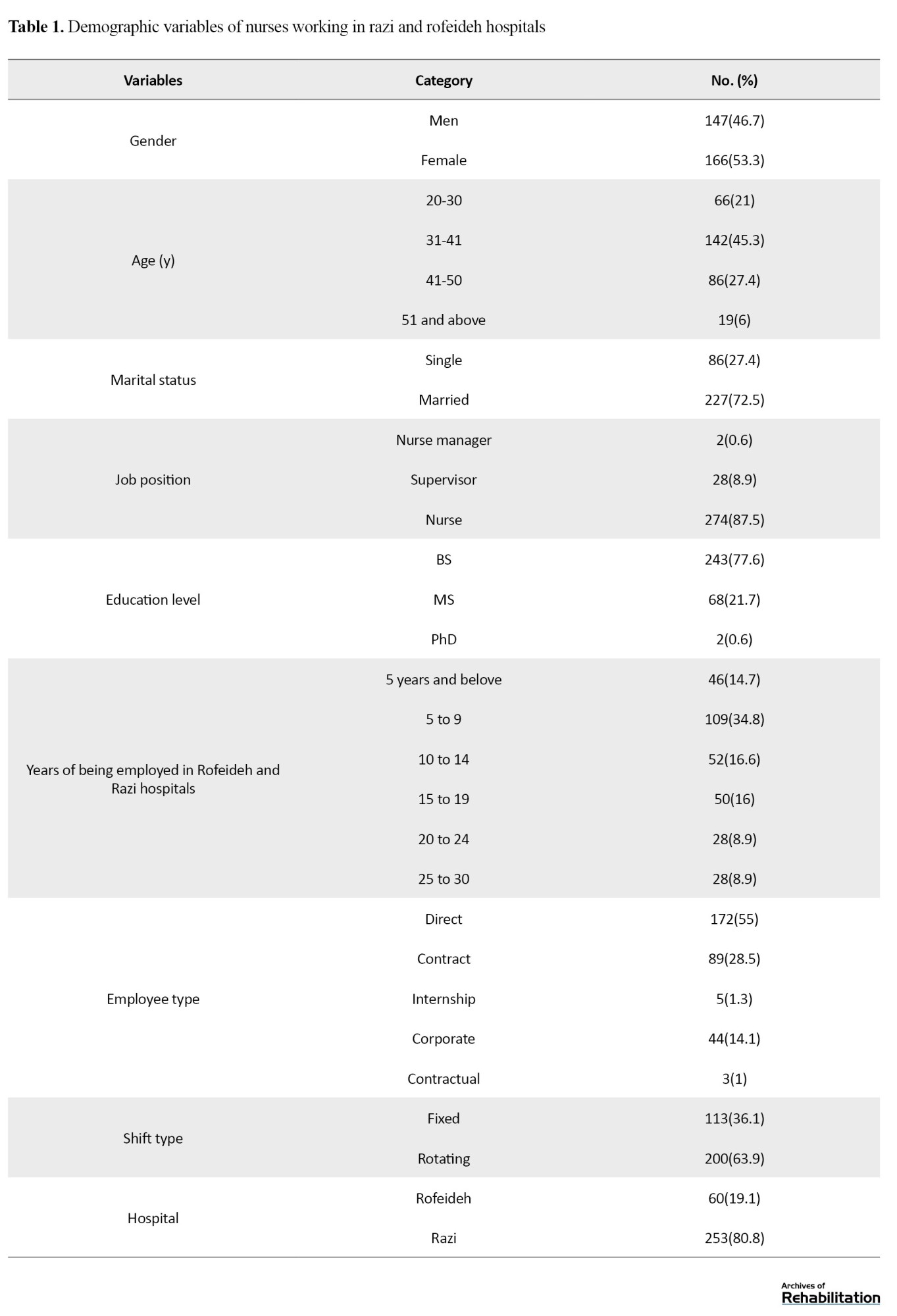

In this study, 253 nurses from Razi Psychiatric Hospital and 60 nurses from Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital participated. According to Table 1, more than half of the participating nurses (53.4%) were male.

Forty-five percent of the participants were between the ages of 31 and 40. Additionally, 72.5% of the participants were married, and 77.6% of the nurses had a bachelor’s degree (Table 1).

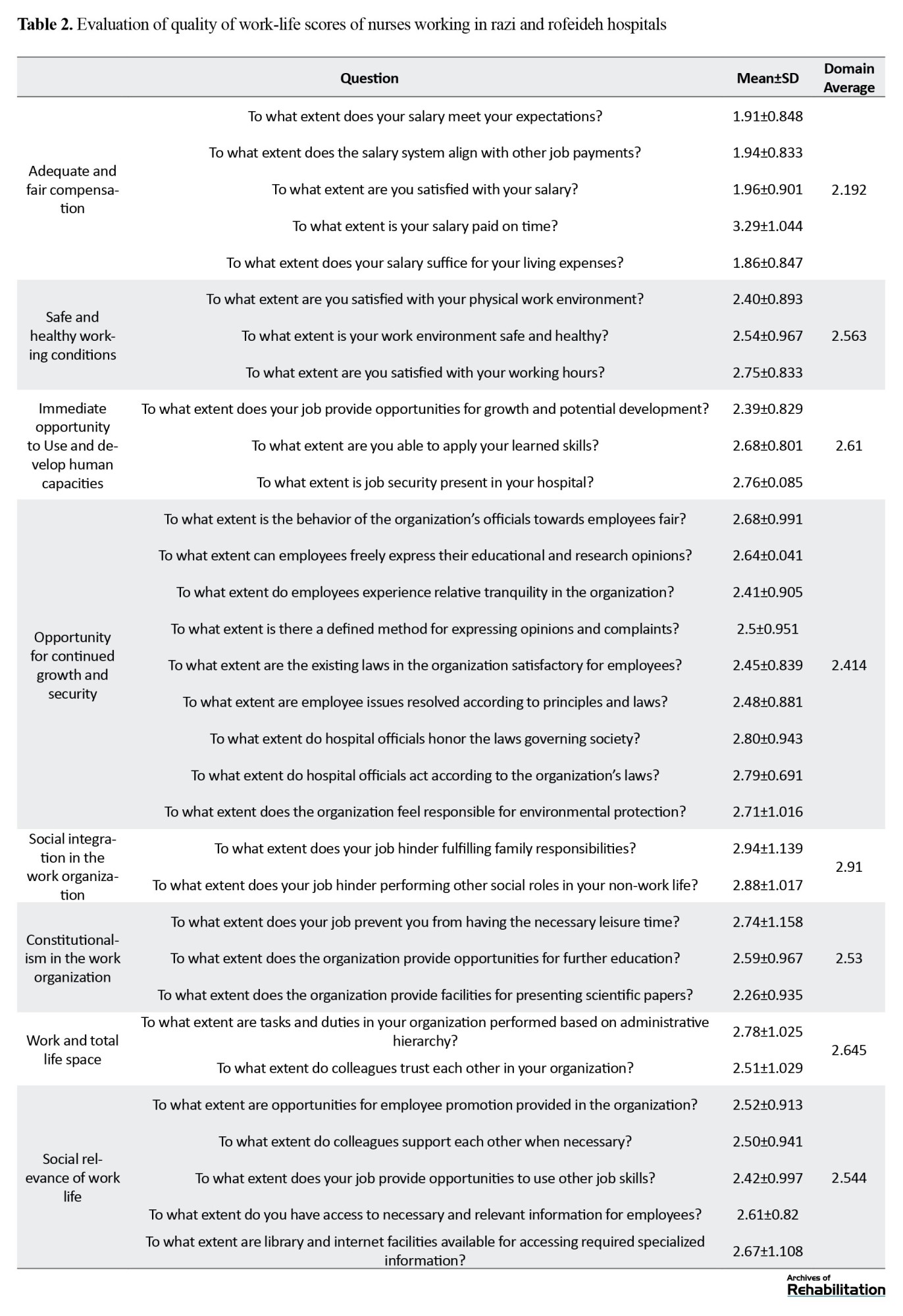

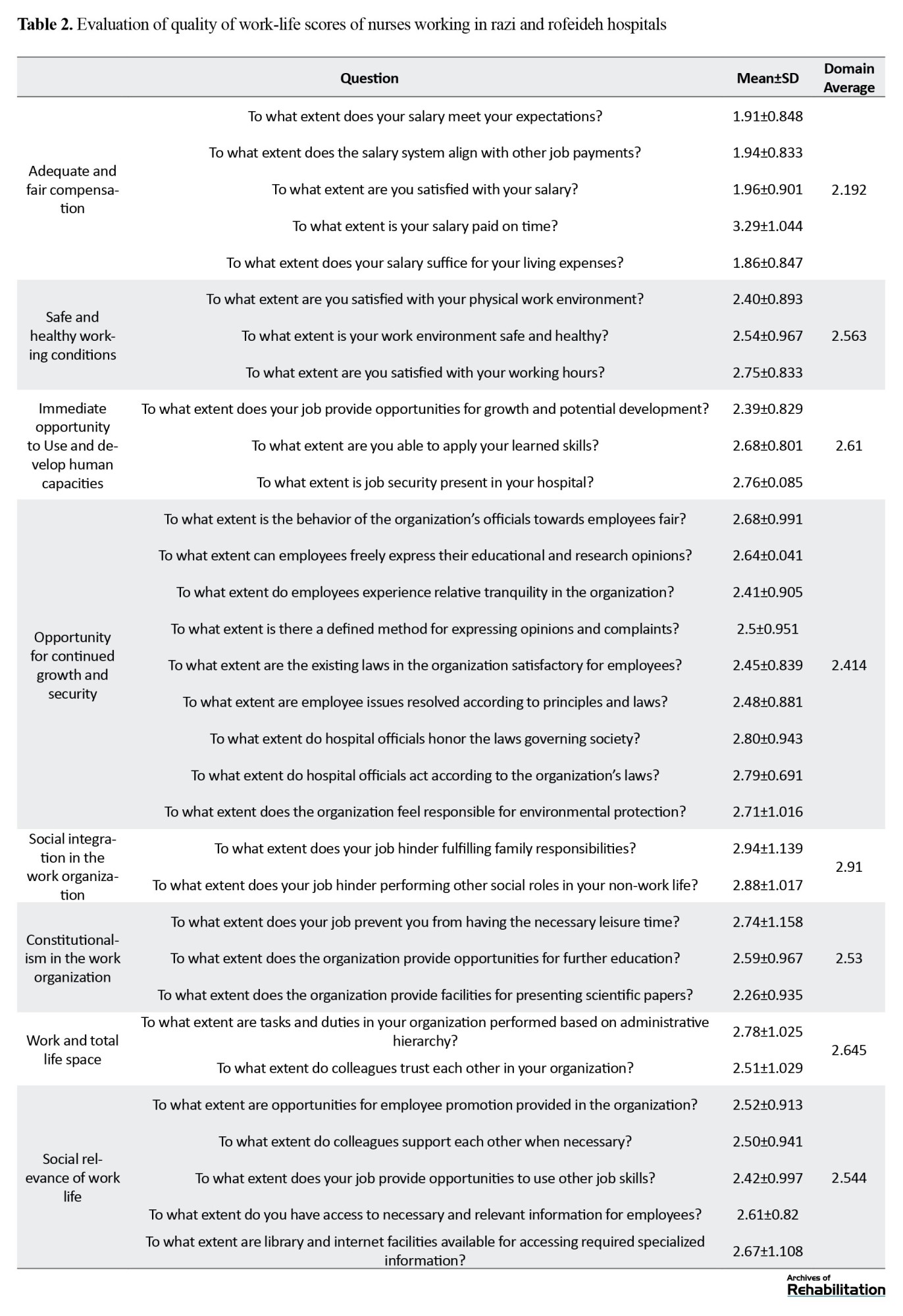

The evaluation of the work-life quality for nurses who were working in Razi Psychiatric Hospital and Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital showed that the highest average score was in the “adequate and fair compensation” domain, specifically for the question “To what extent is your salary paid on time?” with an average of 3.29. The lowest average score was also in the “ adequate and fair compensation “ domain for the “To what extent does your salary suffice for your living expenses?” with an average of 1.86 (Table 2).

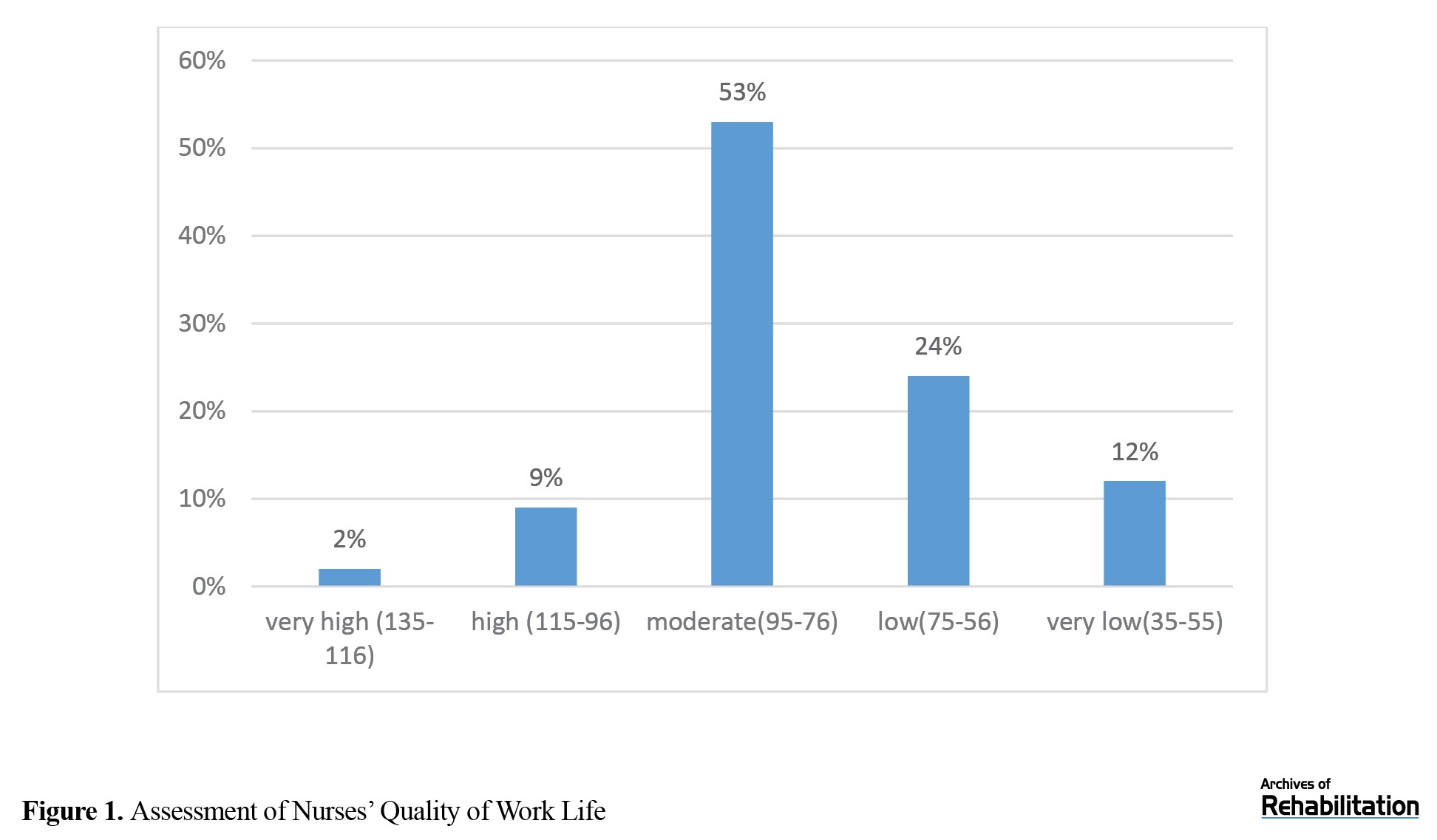

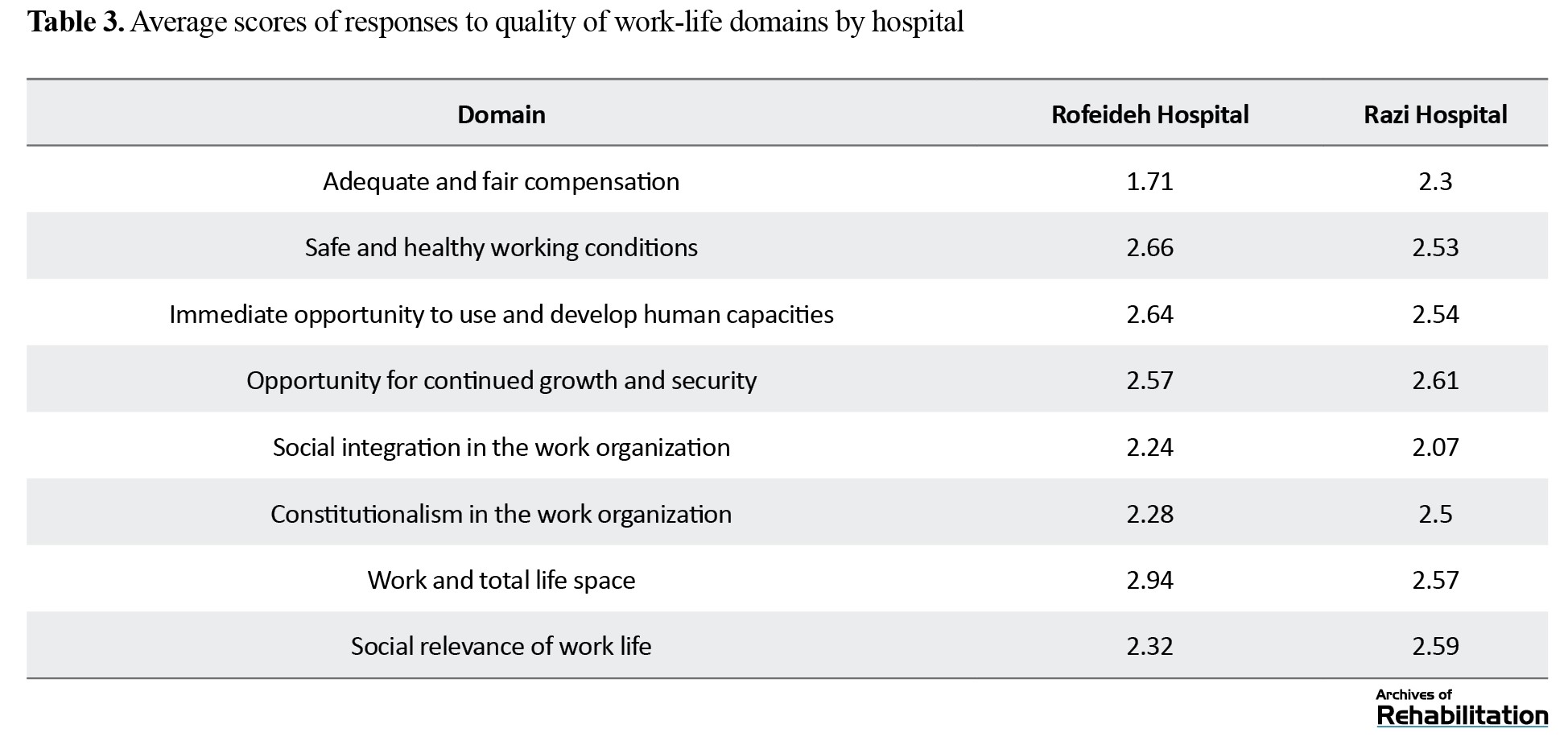

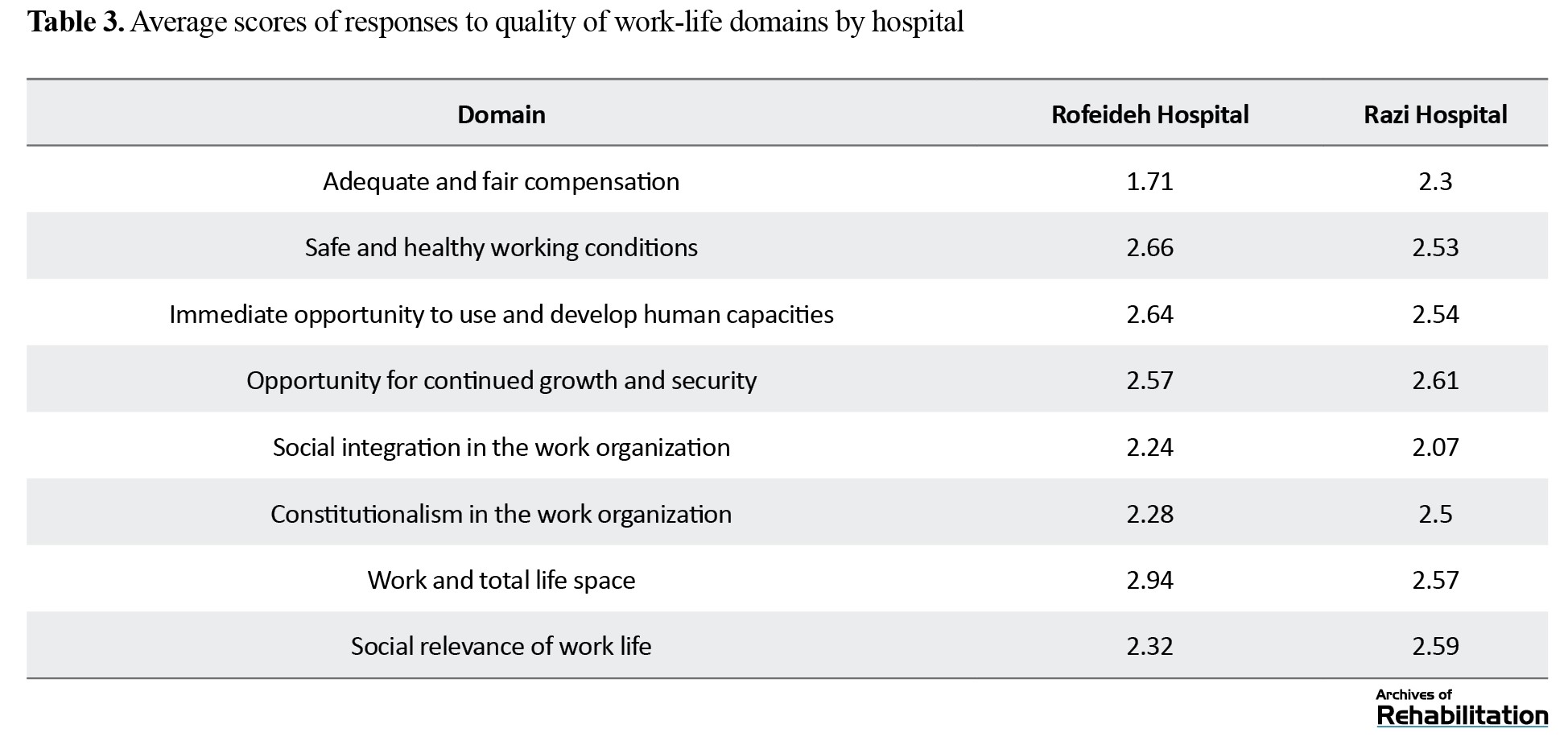

The numerical assessment of nurses’ work-life quality showed that 53% of the participants had a moderate work-life quality. Only 11% of the participants had a very good or good quality of work life. The work-life quality for 36% of the nurses was low or very low (Figure 1). The average scores of the domains of work-life quality indicated that the domain of “adequate and fair compensation” in Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital had the highest average score of 2.94. In contrast, the “opportunity for continued growth and security” domain in Razi Psychiatric Hospital had the highest average score of 2.61. In the domain of “adequate and fair compensation,” Razi Psychiatric Hospital had the lowest average work-life quality score of 2.32, while Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital had the lowest average score of 1.71 among all domains of quality of work-life (Table 3).

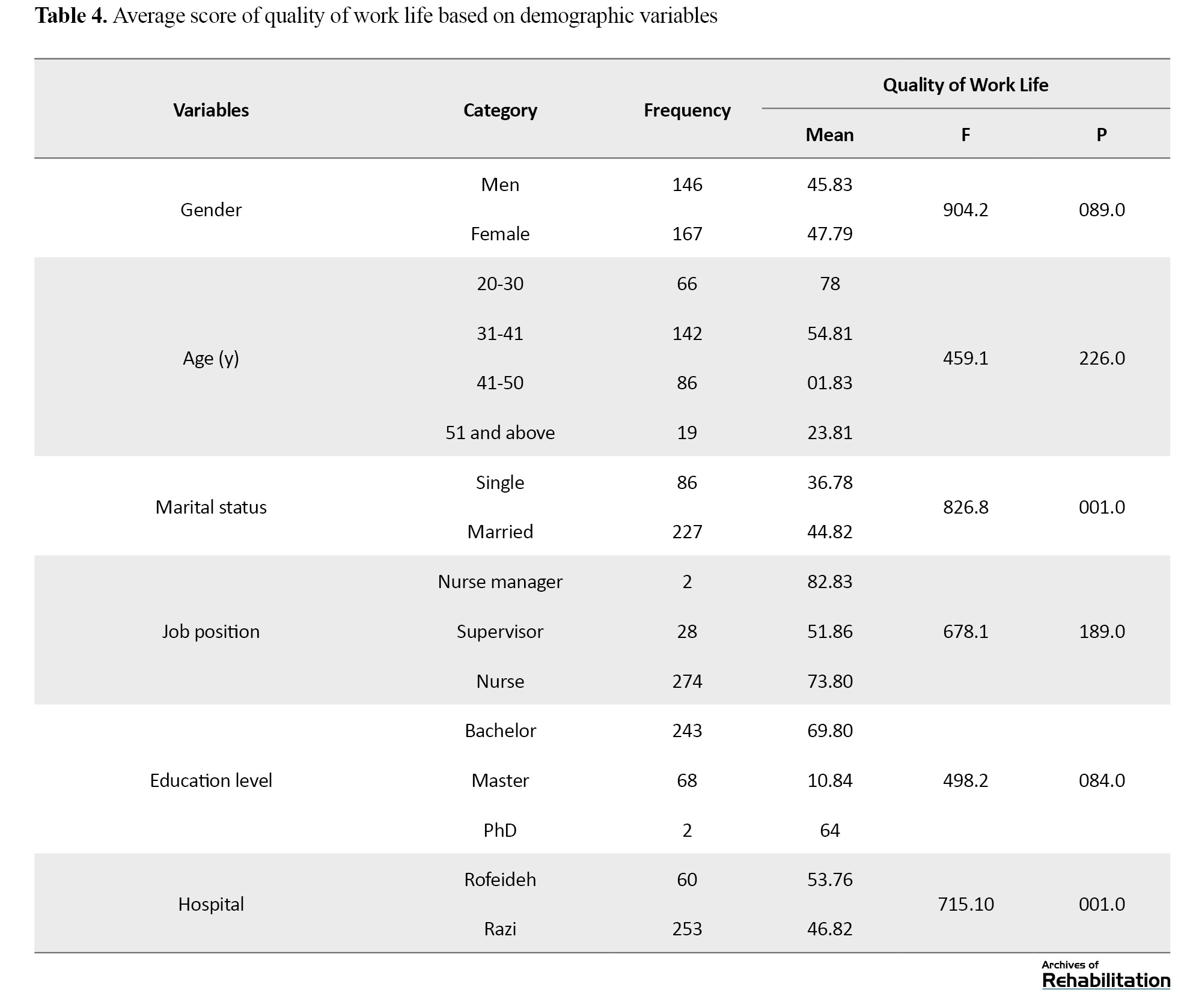

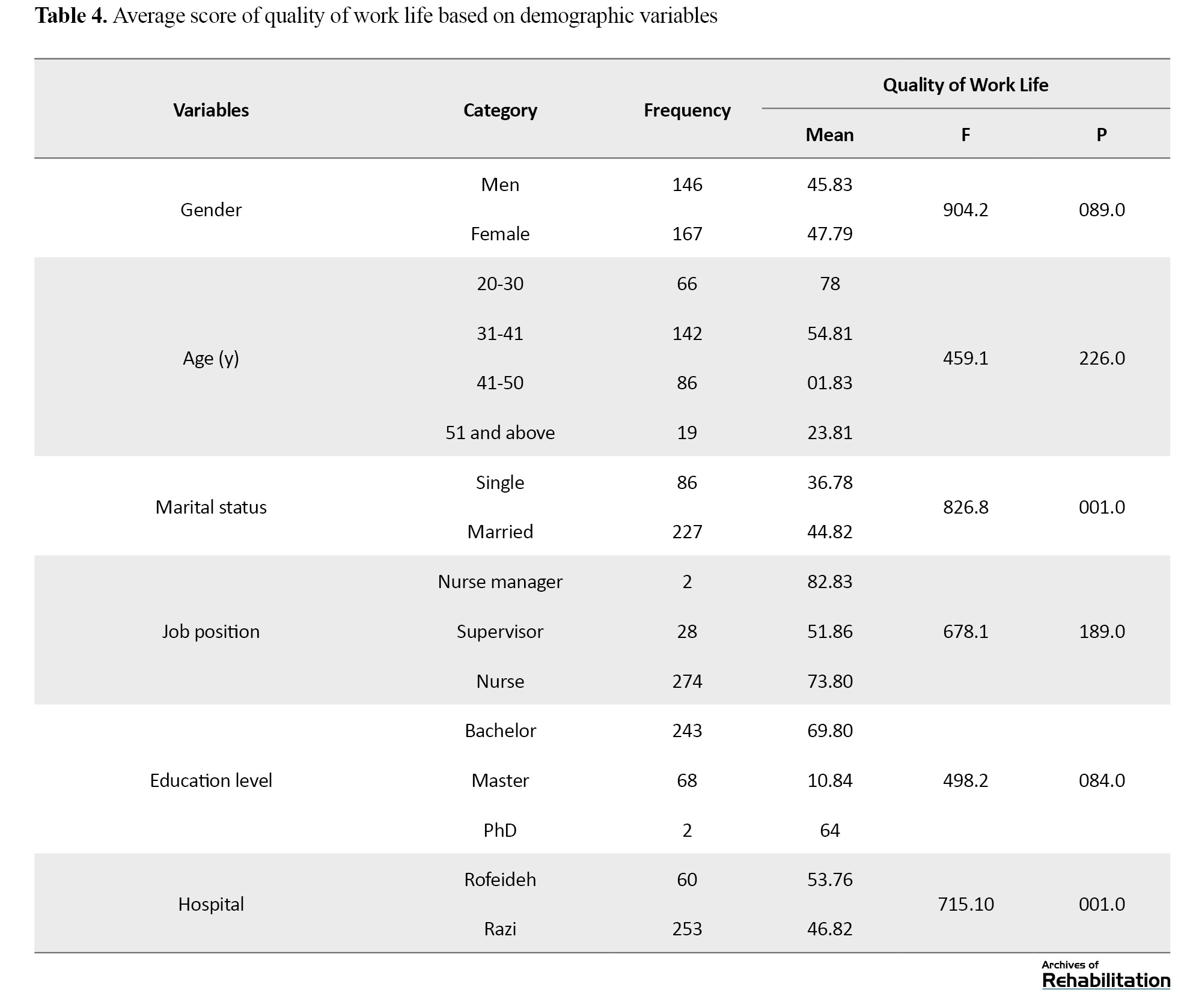

A comparison of the distribution of work-life quality scores between single and married groups showed that the average score for married individuals (82.44) was higher than for singles (78.36), and this difference was significant statistically (P<0.001). A comparison of the distribution of work-life quality scores based on the hospital of employment indicated that the average score at Razi Hospital (82.46) was higher than at Rofeideh Hospital (76.53), and this difference was significant statistically (P<0.001) (Table 4).

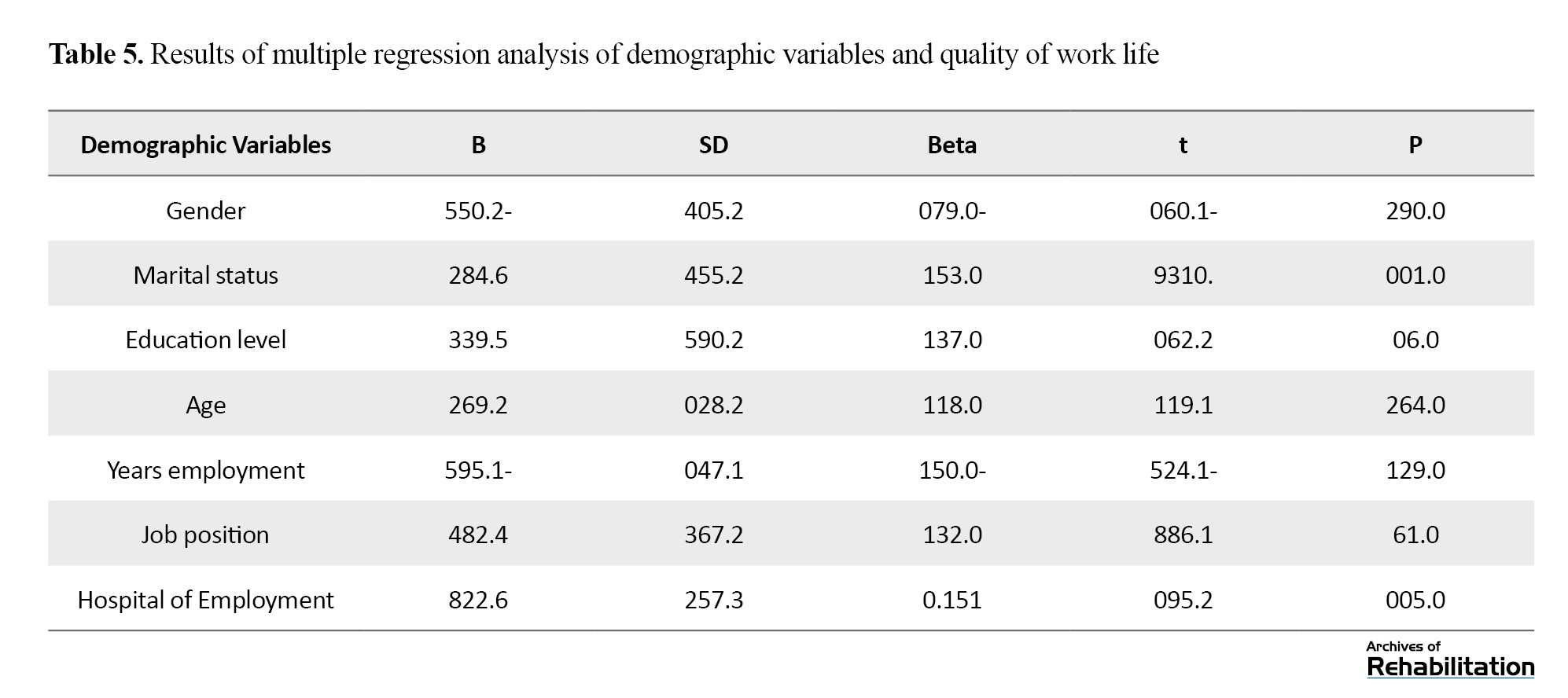

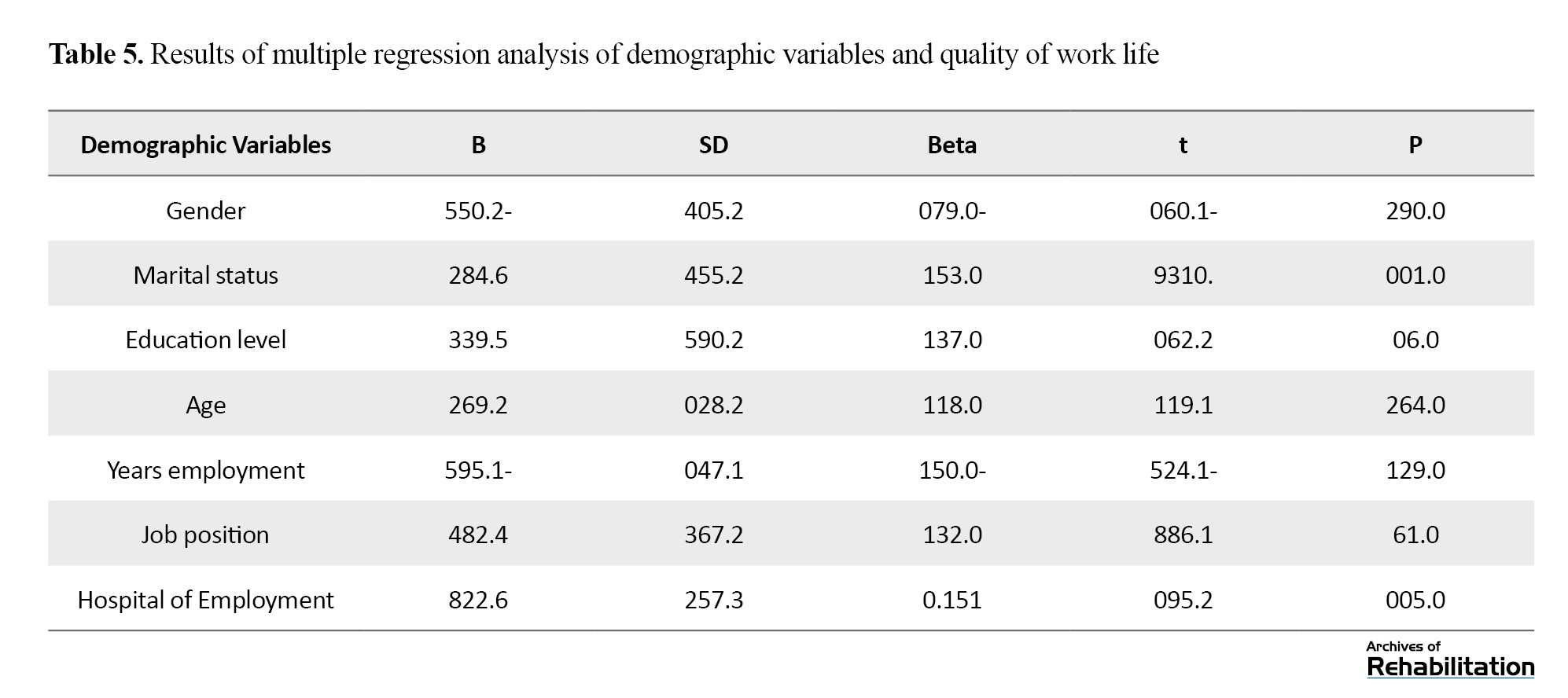

The results of multiple regression analysis of demographic variables and work-life quality showed that two variables, ie, marital status and hospital of employment, have a significant relationship with work-life quality. This finding means that marital status and hospital employment are the most influential factors in predicting the nurses’ quality of work life (Table 5).

Discussion

The current study was designed to determine the work-life quality of nurses working in hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. In this study, the work-life quality was found to be very good for 7 nurses (2%), good for 45 (9%), moderate for 166 (53%), low for 75 (24%), and very low for 20 (12%). Overall, the nurses’ quality of work life in the hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences was moderate to low. The current study findings align with other studies conducted in some hospitals in Iran [8]. Zakeri et al. revealed that nurses working in the intensive care units of hospitals affiliated with Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad City, Iran, had a moderate quality of work life [22]. Bozorgzad et al. also indicated that nurses working in the Emergency Departments of hospitals affiliated with Yazd University of Medical Sciences, Yazd City, Iran, rated their work-life quality as moderate [10]. Moradi et al. demonstrated a moderate work-life quality of nurses working in hospitals affiliated with the Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman City, Iran [4]. Raeissi reported that the work-life quality of nurses was low [24]. Khajehnasiri et al. also showed that nurses working at hospitals affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran City, Iran, were unsatisfied with their work-life quality [25]. Studies in other countries varied. Boonrod et al. showed that the work-life quality of nurses in Thailand was moderate [26]. In countries like Ethiopia, Egypt, and Nigeria, the work-life quality for nurses was also assessed as low [27-29]. However, Nagammal et al. found that in a hospital in Qatar, nurses’ quality of work life was rated as good [30]. Thus, economic conditions, management style, and the organizational structure of hospitals can influence nurses’ quality of work life. In recent years, the excessive migration of nurses has led to a shortage of nurses in hospitals. This condition has resulted in high work pressure for the remaining nurses. The expectation for higher wages and benefits among nurses in this situation and the failure to meet these expectations could explain the low work-life quality of nurses in Iran.

This study investigated 8 aspects of work-life quality across two hospitals: Razi Psychiatric Hospital and Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital. These factors encompassed fair compensation, safe working conditions, opportunities for skill development, job security and growth opportunities, social integration at work, adherence to organizational principles, work-life balance, and the societal significance of work-life.

At Rofeideh Hospital, the highest average score was for the work and total life space domain (2.94), while the lowest was for the “adequate and fair compensation” domain (1.71). This condition highlights the importance of mutual trust among colleagues, adherence to administrative hierarchy, and the level of salaries and wages. Care and treatment activities in the nursing field depend on trust and adherence to the administrative hierarchy. According to the study’s findings, nursing care and treatment actions are acceptable, given the relatively high average score in “the work and total life space” domain at Rofeideh Hospital. At Razi Hospital, the highest average score was for the “opportunity for continued growth and security” domains (2.59), and the lowest score was for the “adequate and fair compensation” domain (2.3). This finding indicates the importance of coworker support, access to information resources, and career advancement opportunities for nurses at Razi Psychiatric Hospital. In both hospitals, the lowest scores were related to economic factors. It can be said that fair and sufficient payment leads to feelings of security, positivity, and the ability to manage life, underscoring the importance of economic factors for nurses. In the study by Ehsan Bakhshi et al., the highest average score pertains to the domain of providing growth opportunities (3.53), and the lowest average score was for the fair and sufficient payment domain (2.29) among nurses who were working in hospitals affiliated with the Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan City, Iran [31]. In the study by Noorbakhsh et al., economic factors were among the most important elements impacting the work-life quality for nurses [32].

Assessing the relationship between work-life quality and demographic variables showed a significant correlation between work-life quality and marital status. Married nurses had a higher work-life quality compared to single nurses. In studies by Lebni et al., Mosisa et al., and Moradi et al., the work-life quality for married nurses was also higher for single nurses [4, 33, 34]. This outcome could be due to greater emotional support from spouses [35], which can help cope with daily work pressures and stresses. Additionally, more interpersonal communication can increase self-confidence and resilience against work-related adversities. In the study by Hemanathan et al., a significant relationship was also found between work-life quality and marital status, with married nurses having a higher work-life quality than single nurses [36].

In the current study, there was no significant relationship between work-life quality and gender. However, more women than men rated their work-life quality higher. Since there is a greater expectation for men to fulfill family needs, the inability of the organization or individual to meet these expectations can potentially impact their work-life quality. Heidari Rafat’s study showed that female nurses had a higher work-life quality than male nurses, although this relationship was not as significant as the present study [37]. Other studies have also indicated no significant relationship between work-life quality and gender [38, 39].

This study found no significant relationship between work-life quality and work experience. Nevertheless, many individuals with more work experience rated their work-life quality as good. Dehghannyieri et al. also indicated no significant relationship between work experience and work-life quality [39]. However, Noorbakhsh et al. confirmed a significant relationship between work experience and work-life quality among nurses [32]. Hemanathan et al. found a significant relationship between work-life quality and work experience, with less experienced individuals having a higher work-life quality [36]. It can be said that individuals with higher work experience have greater mastery of their tasks, which can influence their perception of work-life quality.

The study results showed no significant relationship between the level of education and work-life quality. These findings align with the results of studies by Al-Malki and Suresh [40, 41]. However, in the study by Moradi et al., this relationship was significant, indicating that as the level of education increased, the work-life quality for nurses decreased [4].

This research showed a significant relationship between the work-life quality and the hospital where nurses work. The work-life quality was lower in Rofeideh Hospital than in Razi Hospital. Since fair and sufficient compensation is an influential factor in the quality of life for nurses and Razi Hospital, due to its specialized nature and geographical location, offers better salaries and benefits compared to Rofeideh Hospital, it can be said that this is one of the reasons for the better work-life quality in Razi Psychiatric Hospital. Razi Hospital is located in the Amin Abad area, considered an underprivileged urban area. This factor influences higher salaries and benefits. Additionally, being a single-specialty hospital with the type of patients it serves means fewer emergencies in this hospital. Moradi et al. also showed a significant relationship between the hospital of employment and the work-life quality for nurses, with single-specialty hospitals having a higher work-life quality than general hospitals [8]. Contrary to the present study, Hasan Dargahi found that smaller hospital sizes increase satisfaction with work-life quality [15].

Our results revealed that older individuals had better quality-of-life scores, although these differences were not statistically significant. Suleiman concluded no significant relationship exists between age and work-life quality [42]. Other studies also confirmed this result [43-45]. However, Hemanathan et al. found a significant relationship between the quality of life for nurses and age, with younger individuals having a better work-life quality [36]. This condition could be due to lower job expectations at the beginning of their employment.

One of the constraints of this research was the nurses’ lack of trust in maintaining the confidentiality of information, which led to the cautious completion of the questionnaires. In this regard, the examiners tried to assure the nurses of the confidentiality of the information before distributing the questionnaires. Other research limitations include individual differences and the mental and emotional conditions of the participants when responding to the questions, which could affect the research results and were beyond the researcher’s control.

Conclusion

This study shows that the work-life quality for nurses at the hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences is average to poor. Since, according to studies, the outcomes resulting from low levels of work-life quality are related to the productivity and performance of nurses, the findings of this research can assist senior health officials in formulating appropriate strategies and strategic plans to enhance the work-life quality for nurses as the largest workforce in healthcare organizations, thereby facilitating the achievement of organizational goals. Measures such as salary and benefits reform and holding in-service classes for managers to familiarize them with the importance of work-life quality can influence managers’ decisions to improve the nurses’ quality of life and consequently improve their performance.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (code IR.USWR.REC.1400.322) Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information and had the right to leave the study at any time. Their written informed consent was obtained.

Funding

This study was extracted from a research project funded by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Visualization, conceptualization, editing & review: Seyede Mahboubeh Hosseini Zare; Methodology and validation: Jafar Babapour; Analysis: Ahmad Sireh Sadr; Investigation and Review: Bijan Khorasani, Jafar Babapour, and Seyede Mahboubeh Hosseini Zare; Resources: Maryam Sadat Hosseini; Draft writing: Seyede Mahboubeh Hosseini Zare and Maryam Sadat Hosseini; Supervision and project administration: Bijan Khorasani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the nurses working at Razi Psychiatric Hospital and Refah Rehabilitation Hospital for their participation in this research.

References

Nurses play essential roles in the healthcare system; therefore, their job satisfaction and performance are crucial for the success of hospitals [1]. Nurses’ work-life quality significantly influences their well-being, work experiences, and ability to meet job demands and maintain their mental health [2]. This issue, in turn, influences their job satisfaction and decisions regarding whether to remain in or leave their positions, making it a key factor in shaping organizational behavior, which can lead to job dissatisfaction and burnout when there are problems or shortages in this area [3, 4]. Work-life quality also plays an essential role in satisfaction with other dimensions of life, such as family, leisure, and health [5].

Nurses often work under challenging conditions such as sleep deprivation, high stress, and multiple responsibilities. These factors can negatively affect their mood, behavior, social interactions, overall quality of life, learning capacity, decision-making, and the care they provide to patients [6]. Additionally, nurse shortages, low income, job abandonment, and migration to other countries further reduce their quality of care. Therefore, improving nurses’ work-life quality is essential to attracting and retaining them [7]. Hospitals with low work-life quality face higher rates of job abandonment and absenteeism, while improvements in this area lead to better performance, reduced absenteeism, and lower stress levels [7, 8, 9].

The quality of life and job satisfaction of nurses is a global challenge. In 2010, around 40000 nurses left their jobs, doubling to 80000 by 2020. Ensuring a good quality of work life for nurses increases their productivity and reduces job turnover. However, many nurses still lack a satisfactory work-life quality [10]. In the Gulf region, studies show widespread dissatisfaction among nurses. For example, Al-Maskari et al. found that nurses in Oman generally experience a moderate quality of work life [11]. Similarly, Oweidat et al. reported moderate levels of work quality in Jordan [12]. Kaddourah et al. reported that over half of the nurses working in two healthcare institutions in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, were unsatisfied with their work life, with 94% considering leaving their jobs [13]. In Iran, research by Mohammadi et al. reveals that two-thirds of nurses are dissatisfied with their quality of work life [14], with another study indicating that 74.5% of nurses share this dissatisfaction [15].

The University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences oversees two unique hospitals. Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital is the only rehabilitation hospital in the country, providing services to patients who need rehabilitation for brain injury, spinal cord injury, stroke, cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, cerebral palsy, and other disabling sensory and motor diseases. The largest psychiatric hospital in the Middle East is Razi Psychiatric Hospital, which offers psychiatric services. There are numerous challenges that nurses must deal with in these two hospitals that can impact their quality of life. Understanding the factors that affect the quality of work life for nurses in these hospitals is crucial for developing strategies to enhance motivation, job performance, and nurse retention, indirectly improving patient care quality. Assessing the work-life quality and other key factors is vital in implementing supportive policies for nurses. Given the critical role of nurses in patient health, improving their work-life quality not only enhances patient care quality but also positively impacts the entire healthcare system [16]. This study evaluated the work-life quality of nurses working at the hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Materials & Methods

This descriptive-analytical cross-sectional study was conducted in 2022. The research population consisted of nurses working at Razi Psychiatric and Rofeideh Rehabilitation hospitals, affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. At the time of the study, 605 nurses were employed at the two hospitals (512 nurses at Razi Psychiatric Hospital and 93 nurses at Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital).

To determine the sample size, assuming that the work-life quality was very good for 20% of nurses, the equation 1 was used, resulting in a required sample size of 245:

Given an estimated response rate of 70%, 350 samples were ultimately selected.

Where N is the Sample size, X refers to the nurses working in each hospital, and Y is the total nurses working in these two hospitals, the following formula estimates the number of samples selected from each hospital:

Sample size for Razi Hospital;

Sample size for Razi Hospital; Sample size for Rofeideh Hospital;

Sample size for Rofeideh Hospital;Samples were selected randomly from the nurses working in the two hospitals using their codes. Consequently, 253 nurses from Razi Psychiatric Hospital (85%) and 60 nurses from Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital (100%) participated in the study.

The inclusion criteria required participants to provide informed consent, hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, and have at least one year of work experience. The exclusion criteria included nurses who were ill or on leave during the data collection period.

The Richard Walton quality of work-life questionnaire (1973) was used to measure the work-life quality in this study [16]. Responses were scored using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from very low (1) to very high (5). The questionnaire also included demographic questions at the beginning. The highest possible score was 160, and the lowest was 32, with higher scores indicating a better work-life quality. This questionnaire has been used in similar studies [17-19].

The study objectives and methods for data collection were explained to four trained interviewers. After explaining the study’s objectives and ensuring confidentiality, the interviewers distributed the questionnaires to the participants. They collected the completed questionnaires the following day.

The questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section addressed demographic variables, including the hospital of employment, age, gender, marital status, education level, and work experience. The second part included 32 questions that addressed various dimensions related to work: 5 questions on fair compensation, 3 on safe working conditions, 3 on immediate opportunities for skill development, 9 on opportunities for career growth and job security, 2 on social integration within the workplace, 3 on organizational principles, 2 on balancing work and personal life, and 5 on the societal impact of work-life.

The content validity of the Walton quality of work-life questionnaire has been confirmed by experts and specialists in various studies [20-22]. The Cronbach α coefficients for the trustworthiness of the Walton quality of work-life questionnaire were 0.92 and 0.83 in Talasaz et al. and Imani et al. findings, respectively [20, 23]. For data analysis, descriptive statistics such as frequency, mean, percentage, and standard deviation were computed alongside analytical statistics, including t test, analysis of variance (ANOVA), and regression, using SPSS software, version 23.

In this study, ethical principles in research, such as obtaining informed consent, maintaining confidentiality, and respecting individuals’ privacy, were observed. This article is based on a research project titled “Exploring quality of working life in nurses working at hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences,” approved by the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Health with the ethics code IR.USWR.REC.1400.322.

Results

In this study, 253 nurses from Razi Psychiatric Hospital and 60 nurses from Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital participated. According to Table 1, more than half of the participating nurses (53.4%) were male.

Forty-five percent of the participants were between the ages of 31 and 40. Additionally, 72.5% of the participants were married, and 77.6% of the nurses had a bachelor’s degree (Table 1).

The evaluation of the work-life quality for nurses who were working in Razi Psychiatric Hospital and Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital showed that the highest average score was in the “adequate and fair compensation” domain, specifically for the question “To what extent is your salary paid on time?” with an average of 3.29. The lowest average score was also in the “ adequate and fair compensation “ domain for the “To what extent does your salary suffice for your living expenses?” with an average of 1.86 (Table 2).

The numerical assessment of nurses’ work-life quality showed that 53% of the participants had a moderate work-life quality. Only 11% of the participants had a very good or good quality of work life. The work-life quality for 36% of the nurses was low or very low (Figure 1). The average scores of the domains of work-life quality indicated that the domain of “adequate and fair compensation” in Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital had the highest average score of 2.94. In contrast, the “opportunity for continued growth and security” domain in Razi Psychiatric Hospital had the highest average score of 2.61. In the domain of “adequate and fair compensation,” Razi Psychiatric Hospital had the lowest average work-life quality score of 2.32, while Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital had the lowest average score of 1.71 among all domains of quality of work-life (Table 3).

A comparison of the distribution of work-life quality scores between single and married groups showed that the average score for married individuals (82.44) was higher than for singles (78.36), and this difference was significant statistically (P<0.001). A comparison of the distribution of work-life quality scores based on the hospital of employment indicated that the average score at Razi Hospital (82.46) was higher than at Rofeideh Hospital (76.53), and this difference was significant statistically (P<0.001) (Table 4).

The results of multiple regression analysis of demographic variables and work-life quality showed that two variables, ie, marital status and hospital of employment, have a significant relationship with work-life quality. This finding means that marital status and hospital employment are the most influential factors in predicting the nurses’ quality of work life (Table 5).

Discussion

The current study was designed to determine the work-life quality of nurses working in hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. In this study, the work-life quality was found to be very good for 7 nurses (2%), good for 45 (9%), moderate for 166 (53%), low for 75 (24%), and very low for 20 (12%). Overall, the nurses’ quality of work life in the hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences was moderate to low. The current study findings align with other studies conducted in some hospitals in Iran [8]. Zakeri et al. revealed that nurses working in the intensive care units of hospitals affiliated with Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad City, Iran, had a moderate quality of work life [22]. Bozorgzad et al. also indicated that nurses working in the Emergency Departments of hospitals affiliated with Yazd University of Medical Sciences, Yazd City, Iran, rated their work-life quality as moderate [10]. Moradi et al. demonstrated a moderate work-life quality of nurses working in hospitals affiliated with the Kerman University of Medical Sciences, Kerman City, Iran [4]. Raeissi reported that the work-life quality of nurses was low [24]. Khajehnasiri et al. also showed that nurses working at hospitals affiliated with the Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran City, Iran, were unsatisfied with their work-life quality [25]. Studies in other countries varied. Boonrod et al. showed that the work-life quality of nurses in Thailand was moderate [26]. In countries like Ethiopia, Egypt, and Nigeria, the work-life quality for nurses was also assessed as low [27-29]. However, Nagammal et al. found that in a hospital in Qatar, nurses’ quality of work life was rated as good [30]. Thus, economic conditions, management style, and the organizational structure of hospitals can influence nurses’ quality of work life. In recent years, the excessive migration of nurses has led to a shortage of nurses in hospitals. This condition has resulted in high work pressure for the remaining nurses. The expectation for higher wages and benefits among nurses in this situation and the failure to meet these expectations could explain the low work-life quality of nurses in Iran.

This study investigated 8 aspects of work-life quality across two hospitals: Razi Psychiatric Hospital and Rofeideh Rehabilitation Hospital. These factors encompassed fair compensation, safe working conditions, opportunities for skill development, job security and growth opportunities, social integration at work, adherence to organizational principles, work-life balance, and the societal significance of work-life.

At Rofeideh Hospital, the highest average score was for the work and total life space domain (2.94), while the lowest was for the “adequate and fair compensation” domain (1.71). This condition highlights the importance of mutual trust among colleagues, adherence to administrative hierarchy, and the level of salaries and wages. Care and treatment activities in the nursing field depend on trust and adherence to the administrative hierarchy. According to the study’s findings, nursing care and treatment actions are acceptable, given the relatively high average score in “the work and total life space” domain at Rofeideh Hospital. At Razi Hospital, the highest average score was for the “opportunity for continued growth and security” domains (2.59), and the lowest score was for the “adequate and fair compensation” domain (2.3). This finding indicates the importance of coworker support, access to information resources, and career advancement opportunities for nurses at Razi Psychiatric Hospital. In both hospitals, the lowest scores were related to economic factors. It can be said that fair and sufficient payment leads to feelings of security, positivity, and the ability to manage life, underscoring the importance of economic factors for nurses. In the study by Ehsan Bakhshi et al., the highest average score pertains to the domain of providing growth opportunities (3.53), and the lowest average score was for the fair and sufficient payment domain (2.29) among nurses who were working in hospitals affiliated with the Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences, Rafsanjan City, Iran [31]. In the study by Noorbakhsh et al., economic factors were among the most important elements impacting the work-life quality for nurses [32].

Assessing the relationship between work-life quality and demographic variables showed a significant correlation between work-life quality and marital status. Married nurses had a higher work-life quality compared to single nurses. In studies by Lebni et al., Mosisa et al., and Moradi et al., the work-life quality for married nurses was also higher for single nurses [4, 33, 34]. This outcome could be due to greater emotional support from spouses [35], which can help cope with daily work pressures and stresses. Additionally, more interpersonal communication can increase self-confidence and resilience against work-related adversities. In the study by Hemanathan et al., a significant relationship was also found between work-life quality and marital status, with married nurses having a higher work-life quality than single nurses [36].

In the current study, there was no significant relationship between work-life quality and gender. However, more women than men rated their work-life quality higher. Since there is a greater expectation for men to fulfill family needs, the inability of the organization or individual to meet these expectations can potentially impact their work-life quality. Heidari Rafat’s study showed that female nurses had a higher work-life quality than male nurses, although this relationship was not as significant as the present study [37]. Other studies have also indicated no significant relationship between work-life quality and gender [38, 39].

This study found no significant relationship between work-life quality and work experience. Nevertheless, many individuals with more work experience rated their work-life quality as good. Dehghannyieri et al. also indicated no significant relationship between work experience and work-life quality [39]. However, Noorbakhsh et al. confirmed a significant relationship between work experience and work-life quality among nurses [32]. Hemanathan et al. found a significant relationship between work-life quality and work experience, with less experienced individuals having a higher work-life quality [36]. It can be said that individuals with higher work experience have greater mastery of their tasks, which can influence their perception of work-life quality.

The study results showed no significant relationship between the level of education and work-life quality. These findings align with the results of studies by Al-Malki and Suresh [40, 41]. However, in the study by Moradi et al., this relationship was significant, indicating that as the level of education increased, the work-life quality for nurses decreased [4].

This research showed a significant relationship between the work-life quality and the hospital where nurses work. The work-life quality was lower in Rofeideh Hospital than in Razi Hospital. Since fair and sufficient compensation is an influential factor in the quality of life for nurses and Razi Hospital, due to its specialized nature and geographical location, offers better salaries and benefits compared to Rofeideh Hospital, it can be said that this is one of the reasons for the better work-life quality in Razi Psychiatric Hospital. Razi Hospital is located in the Amin Abad area, considered an underprivileged urban area. This factor influences higher salaries and benefits. Additionally, being a single-specialty hospital with the type of patients it serves means fewer emergencies in this hospital. Moradi et al. also showed a significant relationship between the hospital of employment and the work-life quality for nurses, with single-specialty hospitals having a higher work-life quality than general hospitals [8]. Contrary to the present study, Hasan Dargahi found that smaller hospital sizes increase satisfaction with work-life quality [15].

Our results revealed that older individuals had better quality-of-life scores, although these differences were not statistically significant. Suleiman concluded no significant relationship exists between age and work-life quality [42]. Other studies also confirmed this result [43-45]. However, Hemanathan et al. found a significant relationship between the quality of life for nurses and age, with younger individuals having a better work-life quality [36]. This condition could be due to lower job expectations at the beginning of their employment.

One of the constraints of this research was the nurses’ lack of trust in maintaining the confidentiality of information, which led to the cautious completion of the questionnaires. In this regard, the examiners tried to assure the nurses of the confidentiality of the information before distributing the questionnaires. Other research limitations include individual differences and the mental and emotional conditions of the participants when responding to the questions, which could affect the research results and were beyond the researcher’s control.

Conclusion

This study shows that the work-life quality for nurses at the hospitals affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences is average to poor. Since, according to studies, the outcomes resulting from low levels of work-life quality are related to the productivity and performance of nurses, the findings of this research can assist senior health officials in formulating appropriate strategies and strategic plans to enhance the work-life quality for nurses as the largest workforce in healthcare organizations, thereby facilitating the achievement of organizational goals. Measures such as salary and benefits reform and holding in-service classes for managers to familiarize them with the importance of work-life quality can influence managers’ decisions to improve the nurses’ quality of life and consequently improve their performance.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (code IR.USWR.REC.1400.322) Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information and had the right to leave the study at any time. Their written informed consent was obtained.

Funding

This study was extracted from a research project funded by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Visualization, conceptualization, editing & review: Seyede Mahboubeh Hosseini Zare; Methodology and validation: Jafar Babapour; Analysis: Ahmad Sireh Sadr; Investigation and Review: Bijan Khorasani, Jafar Babapour, and Seyede Mahboubeh Hosseini Zare; Resources: Maryam Sadat Hosseini; Draft writing: Seyede Mahboubeh Hosseini Zare and Maryam Sadat Hosseini; Supervision and project administration: Bijan Khorasani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the nurses working at Razi Psychiatric Hospital and Refah Rehabilitation Hospital for their participation in this research.

References

- Ahmed W, Soliman ES, Shazly MM. Staff nurses’ performance obstacles and quality of work life at Benha University Hospital. IOSR Journal of Nursing and Health Science. 2018; 7(2):65-71. [Link]

- Brooks BA, Anderson MA. Defining quality of nursing work life. Nursing Economic$. 2005; 23(6):319–279. [PMID]

- Kim M, Ryu E. [Structural equation modeling of quality of work life in clinical nurses based on the culture-work-health model (Korean)]. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing. 2015; 45(6):879-89. [DOI:10.4040/jkan.2015.45.6.879] [PMID]

- Moradi T, Maghaminejad F, Azizi-Fini I. Quality of working life of nurses and its related factors. Nursing and Midwifery Studies. 2014; 3(2):e19450. [PMID]

- Flores N, Jenaro C, Begoña Orgaz M, Martín V. Understanding quality of working life of workers with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities. 2011; 24(2):133-41. [DOI:10.1111/j.1468-3148.2010.00576.x]

- Ruzevicius J, Valiukaite J. Quality of life and quality of work life balance: Case study of public and private sectors of Lithuania. Calitatea. 2017; 18(157):77-81. [Link]

- Hwang E. Factors affecting the quality of work life of nurses at tertiary general hospitals in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022; 19(8):4718. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph19084718] [PMID]

- Mosadeghrad AM. Quality of working life: An antecedent to employee turnover intention. International Journal of Health Policy and Management. 2013; 1(1):43-50. [DOI:10.15171/ijhpm.2013.07] [PMID]

- Jenaro C, Flores N, Orgaz MB, Cruz M. Vigour and dedication in nursing professionals: Towards a better understanding of work engagement. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011; 67(4):865-75. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05526.x] [PMID]

- Karimi M, Bozorgzad P, Najafi Ghezeljeh T, Haghani H, Fallah B. [The productivity and quality of work life in emergency nurses (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2021; 34(130):73-90. [DOI:10.52547/ijn.34.130.73]

- Al-Maskari MA, Dupo JU, Al-Sulaimi NK. Quality of work life among nurses: A case study from Ad Dakhiliyah Governorate, Oman. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal. 2020; 20(4):e304–11. [DOI:10.18295/squmj.2020.20.04.005] [PMID]

- Oweidat I, Omari A, ALBashtawy M, Al Omar Saleh, Alrahbeni T, Al-Mugheed K, et al. Factors affecting the quality of working life among nurses caring for Syrian refugee camps in Jordan. Human Resources for Health. 2024; 22(1):1. [DOI:10.1186/s12960-023-00884-8] [PMID]

- Kaddourah B, Abu-Shaheen AK, Al-Tannir M. Quality of nursing work life and turnover intention among nurses of tertiary care hospitals in Riyadh: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Nursing. 2018; 17:43. [DOI:10.1186/s12912-018-0312-0] [PMID]

- Mohammadi M, Mozaffari N, Dadkhah B, Etebari Asl F, Etebari Asl Z. [Study of work-related quality of life of nurses in Ardabil Province Hospitals (Persian)] Journal of Health and Care. 2017; 19(3):108-16. [Link]

- Dargahi H, Gharib M, Goodarzi M. [Quality of work life in nursing employees of Tehran University of Medical Sciences hospitals (Persian)]. Journal of Hayat. 2007; 13 (2):13-21. [Link]

- Walton RE. Quality of working life: What is it. Sloan Management Review. 1973; 15(1):11-21. [Link]

- Jafari N, Heidari A, Kouhestani E, Khatirnamani Z. [Relationship between quality of work life and organizational commitment among Health care staff in Gorgan (Persian)]. Iran. Journal of Occupational Hygiene Engineering. 2024; 10(4):307-16. [DOI:10.32592/joohe.10.4.307]

- Rezaei F. [The relationship between the quality of sleep and the quality of work life with the occupational stress of nurses and hospital personnel in Kermanshah during the Covid-19 Era (Persian)]. Paramedical Sciences and Military Health. 2023; 18(1):28-37. [Link]

- Nakhei A, Asadolahi Z, Hasani H, Abazari A, Abazari L, Rahimi N. [Relationship between covid-19 related anxiety and quality of work life in nurses working in hospitals affiliated to Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2023; 35(140):560-71. [DOI:10.32598/ijn.35.140.1141.7]

- Talasaz ZH, Saadoldin SN, Shakeri MT. Relationship between components of quality of work life with job satisfaction among midwives in Mashhad, 2014. Hayat. 2015; 21(1):56-67. [Link]

- Jafari M, Habibi Houshmand B, Maher A. [Relationship of occupational stress and quality of work life with turnover intention among the nurses of public and private hospitals in selected cities of Guilan Province, Iran, in 2016 (Persian)]. Journal of Health Research in Community. 2017; 3(3):12-24. [Link]

- Zakeri M, Barkhordari-Sharifabad M, Bakhshi M. [Investigating the performance obstacles of intensive care units from the perspective of nurses and its relationship with quality of work life (Persian)]. Journal of Nursing Education (JNE). 2021; 10(2):1-12. [Link]

- Imani B, Karamporian A, Hamidi Y. [The relationship between quality of work life and job stress in employees the foundation of martyrs and veterans affairs of Hamadan (Persian)]. Journal of Military Medicine. 2014; 15(4):253-7. [Link]

- Raeissi P, Rajabi MR, Ahmadizadeh E, Rajabkhah K, Kakemam E. Quality of work life and factors associated with it among nurses in public hospitals, Iran. The Journal of the Egyptian Public Health Association. 2019; 94(1):25. [DOI:10.1186/s42506-019-0029-2] [PMID]

- Khajehnasiri F, Foroushani AR, Kashani BF, Kassiri N. Evaluation of the quality of working life and its effective factors in employed nurses of Tehran University of Medical Sciences Hospitals. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2021; 10:112.[DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_790_20] [PMID]

- Boonrod W. Quality of working life: Perceptions of professional nurses at Phramongkutklao Hospital. Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand. 2009; 92(1):S7-15. [PMID]

- Kelbiso L, Belay A, Woldie M. Determinants of quality of work life among nurses working in Hawassa town public health facilities, South Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Nursing Research and Practice. 2017; 2017:5181676. [DOI:10.1155/2017/5181676] [PMID]

- Awosusi O. Assessment of quality of working-life of nurses in two tertiary hospitals in Ekiti State, Nigeria. African Research Review. 2010; 4(2). [DOI:10.4314/afrrev.v4i2.58295]

- Morsy SM, Sabra HE. Relation between quality of work life and nurses job satisfaction at Assiut university hospitals. Al-azhar Assiut Medical Journal. 2015; 13(1):163-71. [Link]

- Nagammal S, Nashwan AJ, Nair S, Susmitha A. Quality of working life of nurses in a tertiary cancer center in Qatar. Nursing. 2017; 6(1):1-9. [Link]

- Bakhshi E, Kalantari R, Salimi N, Ezati F. [Assessment of quality of work life and factors related to it based on the Walton’s model: A cross-sectional study in employment of health and treatment sectors in islamabad city (Persian)]. Journal of Health in the Field. 2019; 6(4):12-9. [Link]

- Noorbakhsh Haqvardi M, Mirzaei A, Alimohammadzadeh K. [Investigating the factors affecting the quality of work life of nurses and its relationship with the lifestyle of nurses in hospitals affiliated to Tabriz University of Medical Sciences during the Covid19 epidemic (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research. 2022; 17(5):88-99. [DOI:10.22034/IJNR.17.5.88]

- Lebni JY, Toghroli R, Abbas J, Kianipour N, NeJhaddadgar N, Salahshoor MR, et al. Nurses’ work-related quality of life and its influencing demographic factors at a public hospital in Western Iran: A cross-sectional study. International Quarterly of Community Health Education. 2021; 42(1):37-45. [DOI:10.1177/0272684X20972838] [PMID]

- Mosisa G, Abadiga M, Oluma A, Wakuma. Quality of work-life and associated factors among nurses working in Wollega zones public hospitals, West Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Africa Nursing Sciences. 2022; 17:100466. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijans.2022.100466]

- Sharhraky Vahed A, Mardani Hamuleh M, Asadi Bidmeshki E, Heidari M, Hamedi Shahraky S. [Assessment of the items of SCL90 test with quality of work life among Amiralmomenin Hospital personnel of Zabol City (Persian)]. Avicenna Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2011; 18(2):50-5. [Link]

- Hemanathan R, Sreelekha PP, Golda M. Quality of work life among nurses in a tertiary care hospital. JOJ Nursing & Health Care. 2017; 5(4):1-8. [Link]

- Heidari-Rafat A, Enayati-Navinfar A, Hedayati A. [Quality of work life and job satisfaction among the nurses of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Persian)]. Dena. 2010; 5(3):4. [Link]

- Mansourie Ghezelhesari E, Emami Moghadam Z, Movahhedifar M, Behnam Vashani H. [Relationship between the quality of work life and demographic characteristics of nurses working in educational hospitals in Mashhad, Iran (Persian)]. Navid No. 2021; 24(78):87-95. [DOI:10.22038/nnj.2021.54728.1255]

- Dehghannyieri N, Salehi T, Asadinoghabi AA. [Assessing the quality of work life, productivity of nurses and their relationship (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Nursing Research. 2008; 3(9):27-37. [Link]

- Almalki MJ, Fitzgerald G, Clark M. Quality of work life among primary health care nurses in the Jazan region, Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Human Resources for Health. 2012; 10:30. [DOI:10.1186/1478-4491-10-30] [PMID]

- Suresh D. Quality of nursing work life among nurses working in selected government and private hospitals in Thiruvananthapuram [MA thesis]. Kerala: Sree Chitra Tirunal Institute for Medical Sciences & Technology; 2013. [Link]

- Suleiman K, Hijazi Z, Al Kalaldeh M, Abu Sharour L. Quality of nursing work life and related factors among emergency nurses in Jordan. Journal of Occupational Health. 2019; 61(5):398-406. [DOI:10.1002/1348-9585.12068] [PMID]

- Bragard I, Fleet R, Etienne AM, Archambault P, Légaré F, Chauny JM, et al. Quality of work life of rural emergency department nurses and physicians: A pilot study. BMC Research Notes. 2015; 8:116. [DOI:10.1186/s13104-015-1075-2] [PMID]

- Martel JP, Dupuis G. Quality of work life: Theoretical and methodological problems, and presentation of a new model and measuring instrument. Social Indicators Research. 2006; 77:333-68. [DOI:10.1007/s11205-004-5368-4]

- Fu X, Xu J, Song L, Li H, Wang J, Wu X, et al. Validation of the Chinese version of the quality of nursing work life scale. Plos One. 2015; 10(5):e0121150. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0121150] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Rehabilitation Management

Received: 19/02/2024 | Accepted: 27/07/2024 | Published: 1/01/2025

Received: 19/02/2024 | Accepted: 27/07/2024 | Published: 1/01/2025

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |