Volume 25 - Special Issue

jrehab 2024, 25 - Special Issue: 540-575 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hassanati F, Nobakht Z, Ghorbanpour Z, Amiri Arimi S, Saatchi M, Shirinbayan P et al . The Impact of COVID-19 on Mental Health of Children and Adolescents With Developmental Disabilities: A Scoping Review. jrehab 2024; 25 (S3) :540-575

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3439-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3439-en.html

Fatemeh Hassanati1

, Zahra Nobakht2

, Zahra Nobakht2

, Zahra Ghorbanpour2

, Zahra Ghorbanpour2

, Somayeh Amiri Arimi3

, Somayeh Amiri Arimi3

, Mohammad Saatchi4

, Mohammad Saatchi4

, Peymaneh Shirinbayan5

, Peymaneh Shirinbayan5

, Farin Soleimani *6

, Farin Soleimani *6

, Zahra Nobakht2

, Zahra Nobakht2

, Zahra Ghorbanpour2

, Zahra Ghorbanpour2

, Somayeh Amiri Arimi3

, Somayeh Amiri Arimi3

, Mohammad Saatchi4

, Mohammad Saatchi4

, Peymaneh Shirinbayan5

, Peymaneh Shirinbayan5

, Farin Soleimani *6

, Farin Soleimani *6

1- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences. Khorramabad, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran.

5- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

6- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,Fa.soleimani@uswr.ac.ir

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Lorestan University of Medical Sciences. Khorramabad, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science, Tehran, Iran.

5- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

6- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: Adolescent, Attention deficit and hyperactivity, Autism spectrum disorder, Children, COVID-19, Developmental disabilities, Mental health

Full-Text [PDF 7443 kb]

(826 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6196 Views)

Full-Text: (908 Views)

Introduction

COVID-19 as a global pandemic has created new stressors for humans worldwide. The extended period of quarantine increased psychological problems, such as post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, depression, low mood and irritability in adults and children [1]. Meanwhile, people with disabilities, including physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory disabilities, are highly likely to experience worse outcomes and greater health needs during the COVID-19 [2].

In these groups, children and adolescents should be provided with adequate support and may be more sensitive to the psychosocial health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic than others [3], because they are in a golden time of their development. Furthermore, approximately half of all mental health conditions are developed before the age of 14 years. One study performed a systematic review of the prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meta-analysis results showed the prevalence of depression was 29%, anxiety was 26%, sleep disorders were 44%, and post-traumatic stress symptoms were 48%. Children and boys had a lower prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to adolescents and girls [4]. Children and adolescents with a background of mental health disorders, such as autism spectrum disorders (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and so on, may have more mental health problems during the pandemic [5]. Studies have shown that long school closures, extreme social isolation, and its consequences have caused mental health problems and these factors may have imposed elevated levels of emotional distress [6]. Also, sudden changes in daily routines were associated with various outcomes in children’s mental health [7, 8, 9]. Based on our investigations and findings, most of the available studies in this field are about the typically developing subjects [10]. Therefore, comprehensive knowledge and resources about mental health issues in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities are essential to support them and their caregivers as well as to manage such crises in the future.

The purpose of this review is to determine the prevalence, correlations, and predicting factors of mental health problems in three groups of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities, namely ASD, ADHD, and other developmental disabilities, including cerebral palsy, learning disabilities, Down syndrome, and so on, during the COVID-19 pandemic and their comparison pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

This was a scoping review study. Scope review is a type of article review suitable for more general-purpose reviews. Therefore, reports should be different from systematic reviews [11]. The main goal of the research is to study mental health outcomes in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. We reviewed articles according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses- scoping review guidelines [11]. We included experimental and observational studies published between January 1, 2020, and September 1, 2022. We systematically searched the ISI, PubMed, and Scopus databases. We used MeSH terms and entered the terms into the title/abstract search. The language of the included studies was English. The search terms were as follows: “COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “Mental Health”, “Intellectual Disability”, “Developmental Disabilities”, “Learning Disabilities”, “Neurodevelopmental Disorders”, “Autistic Disorder”, “Autism Spectrum Disorder”, “Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity”, “Cerebral Palsy”, “Stuttering”, “Language Disorders”, “Mental Retardation”, “Communication Disorders”, “Dyslexia”, “ADHD”, “Cognition Disorders”, “Dyscalculia”, and “Agraphia”.

We selected self-report or caregiver report scales that were specifically designed for mental health assessment. In addition, we excluded studies about adults with disabilities or typically developing children. Articles that were not in our research timeline were excluded from the study.

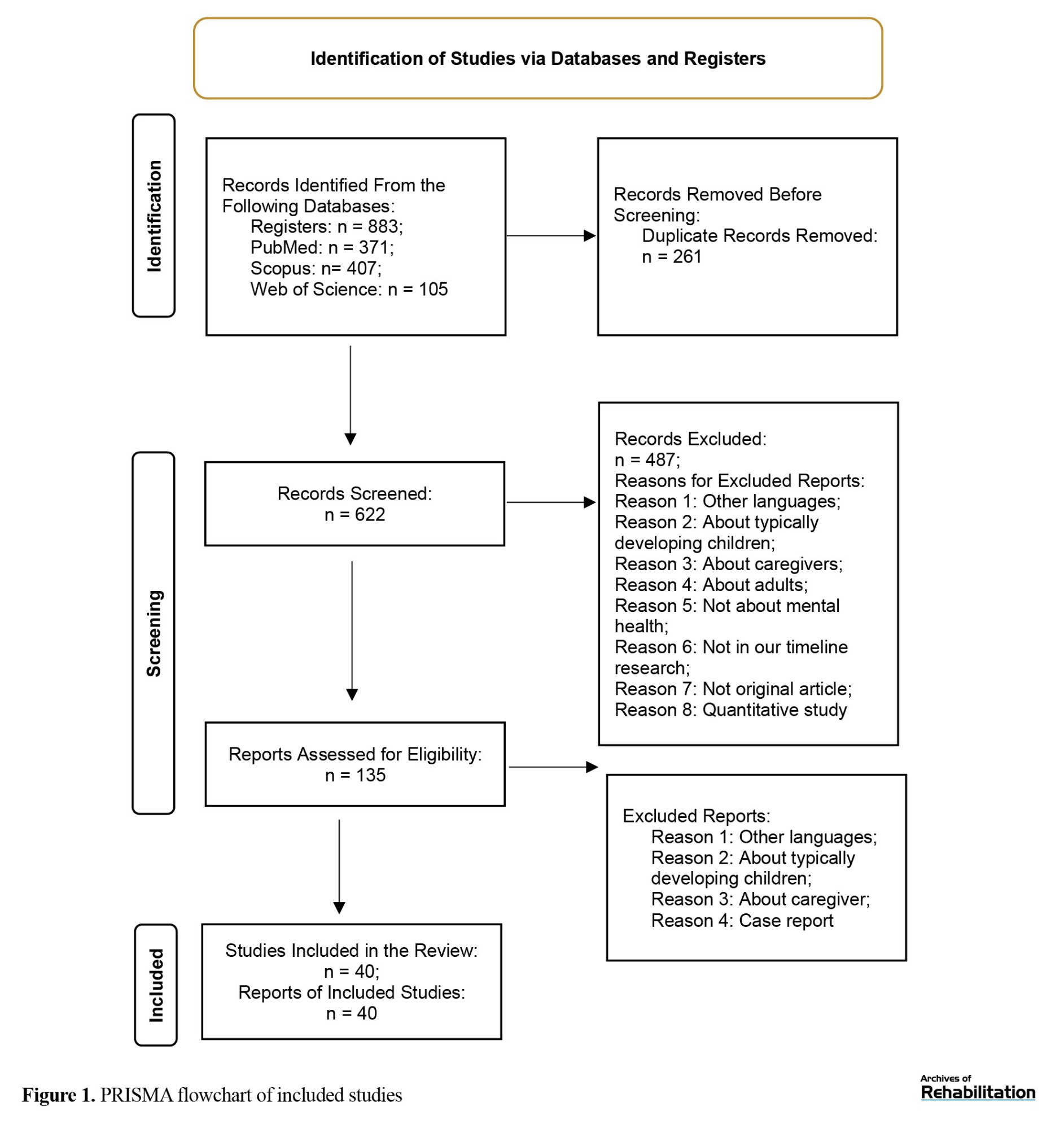

By searching the three selected databases, a total of 883 articles were obtained. Duplicate articles (n=261) were removed. Subsequently, two reviewers independently (Zahra Ghorbanpour, Zahra Nobakht) screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles (n=622) in two stages. First, the titles and abstracts of articles were screened. Finally, if the two researchers did not agree, the third researcher (Fatemeh Hassanati) made the final decision.

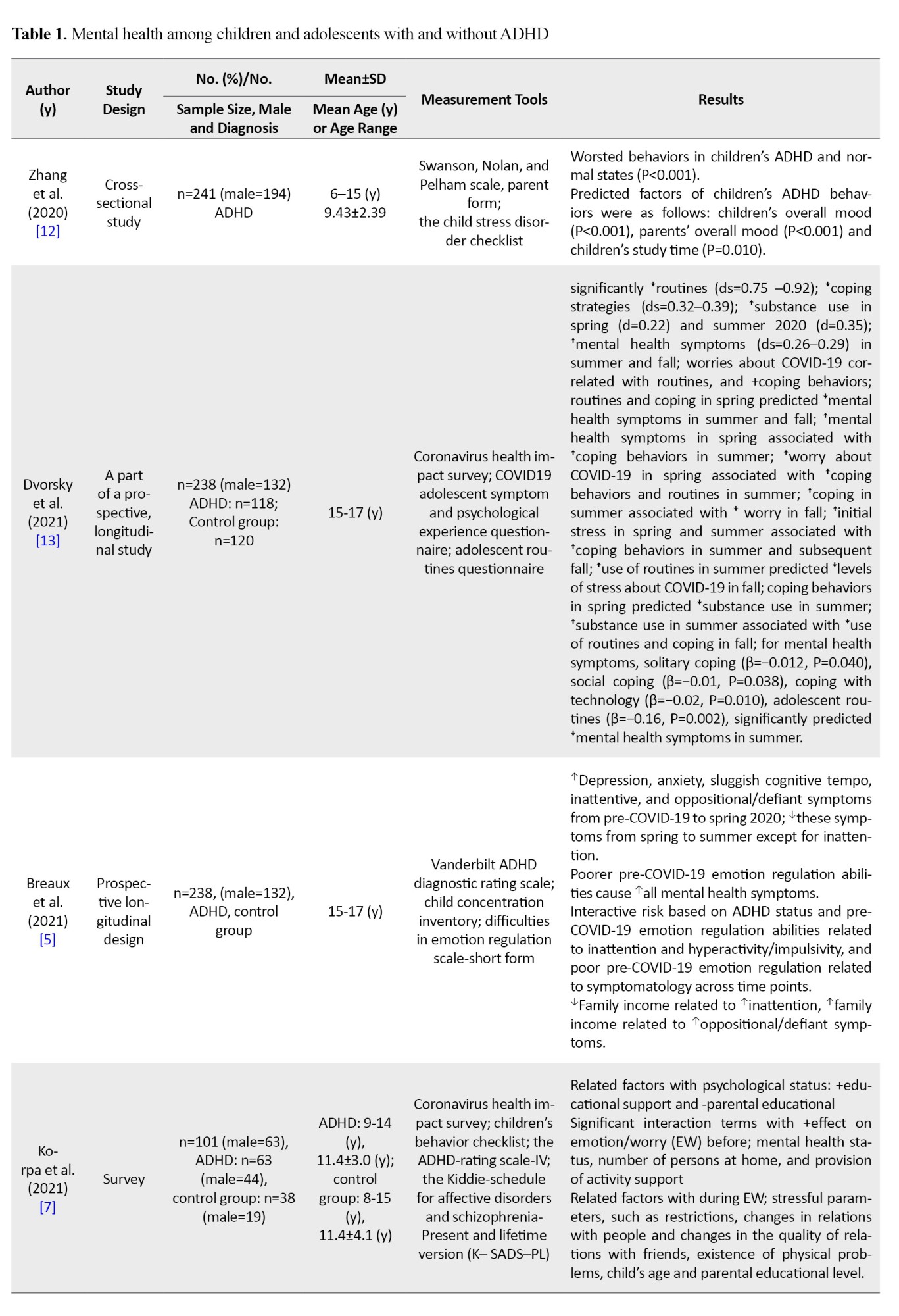

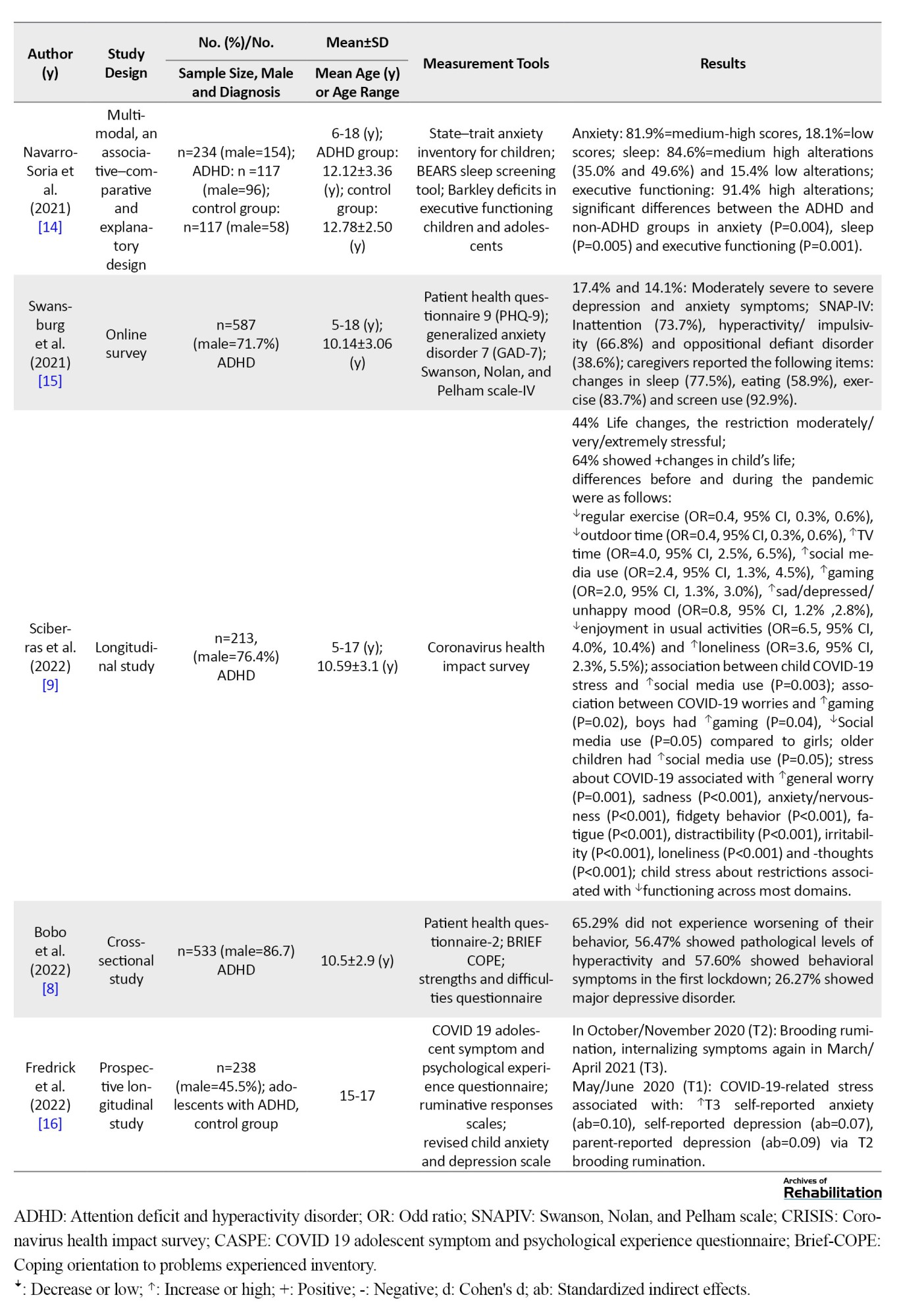

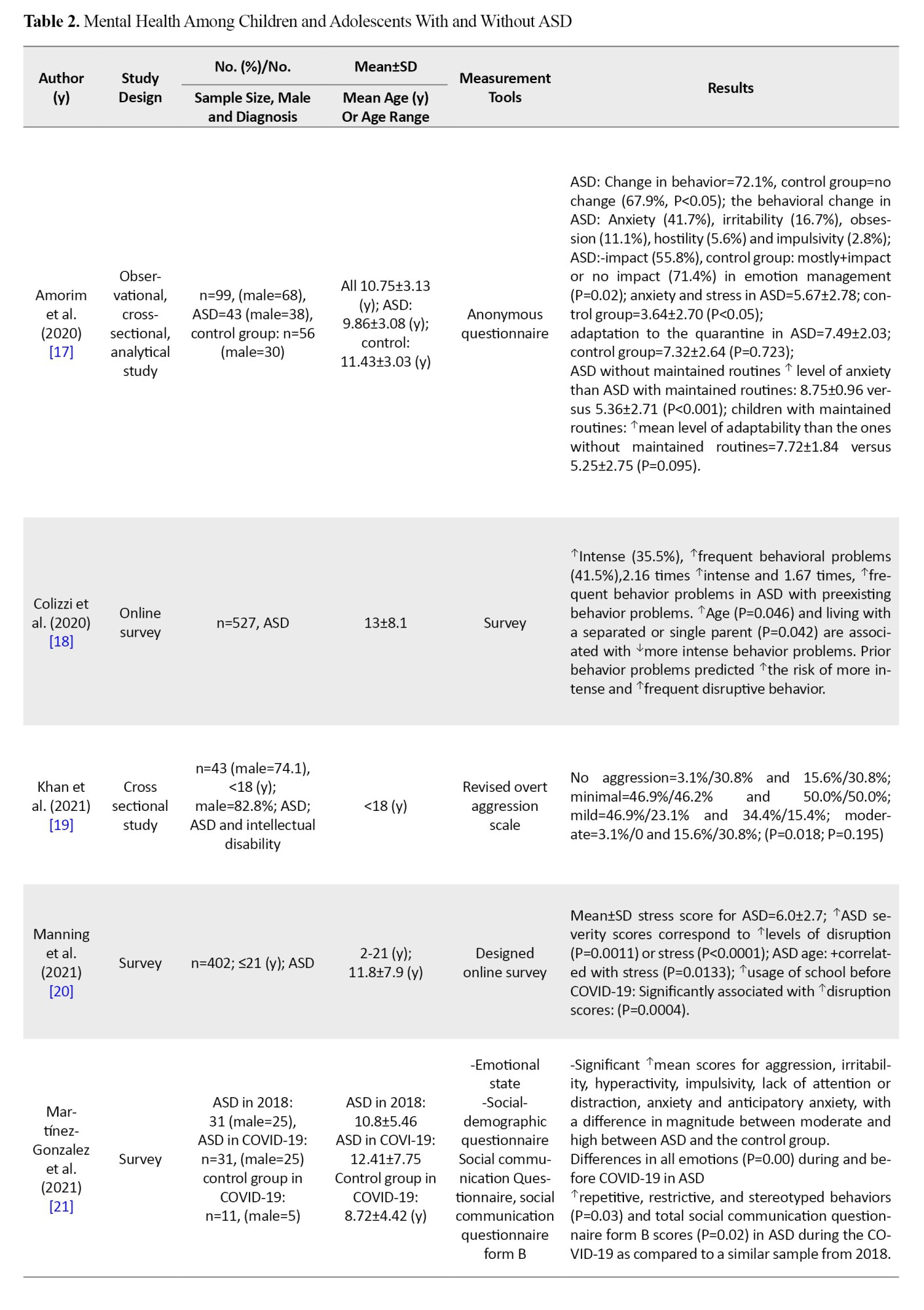

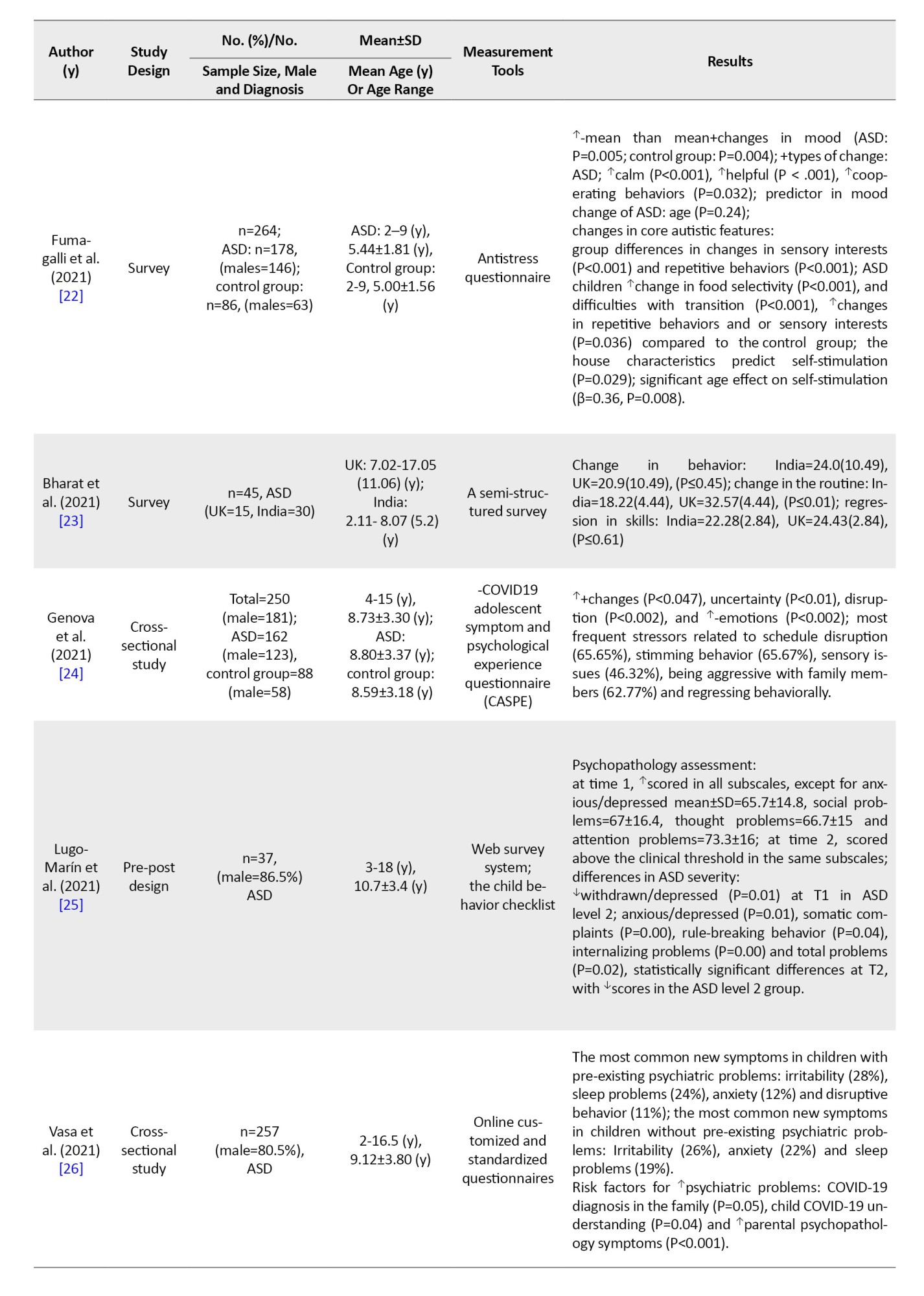

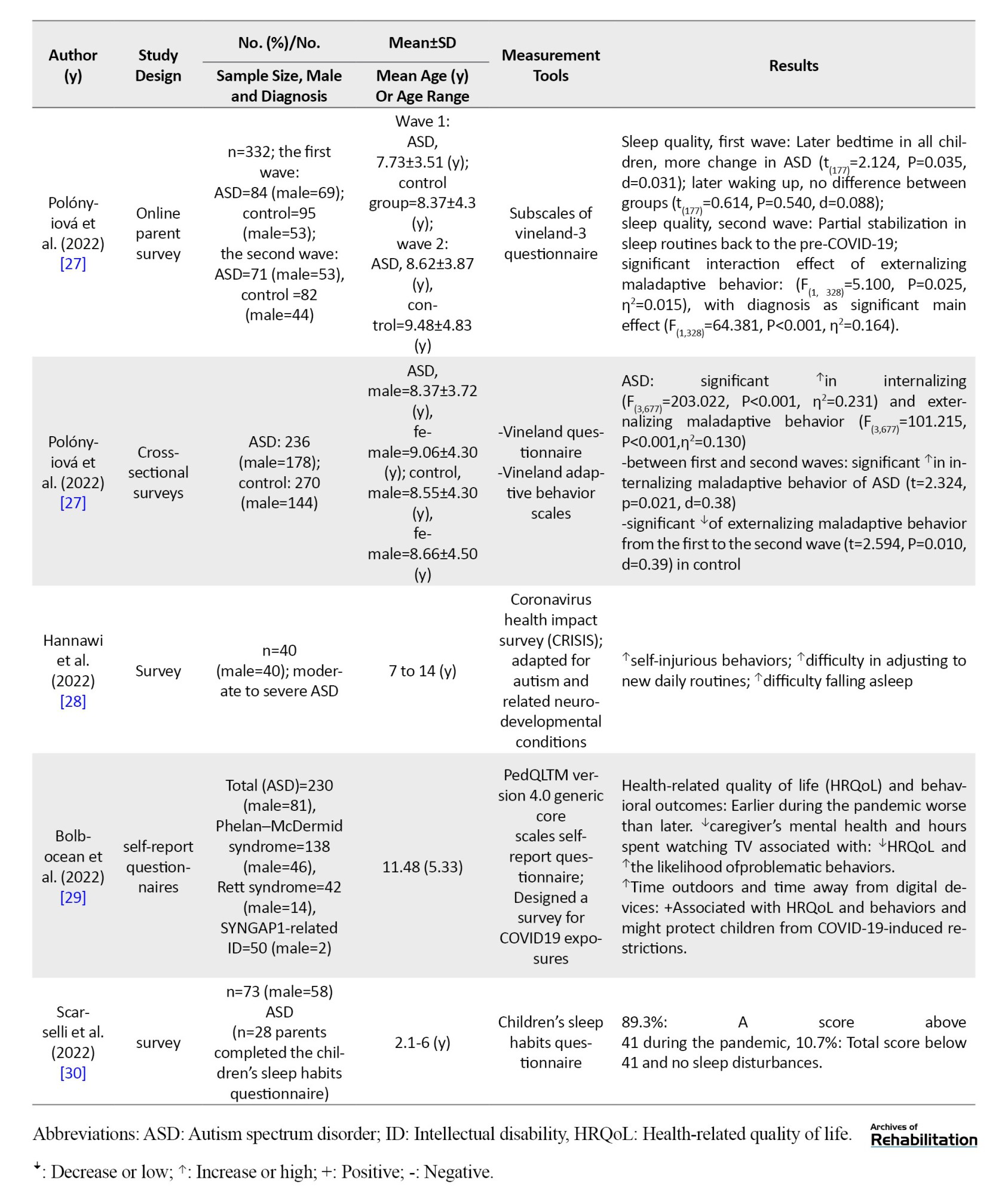

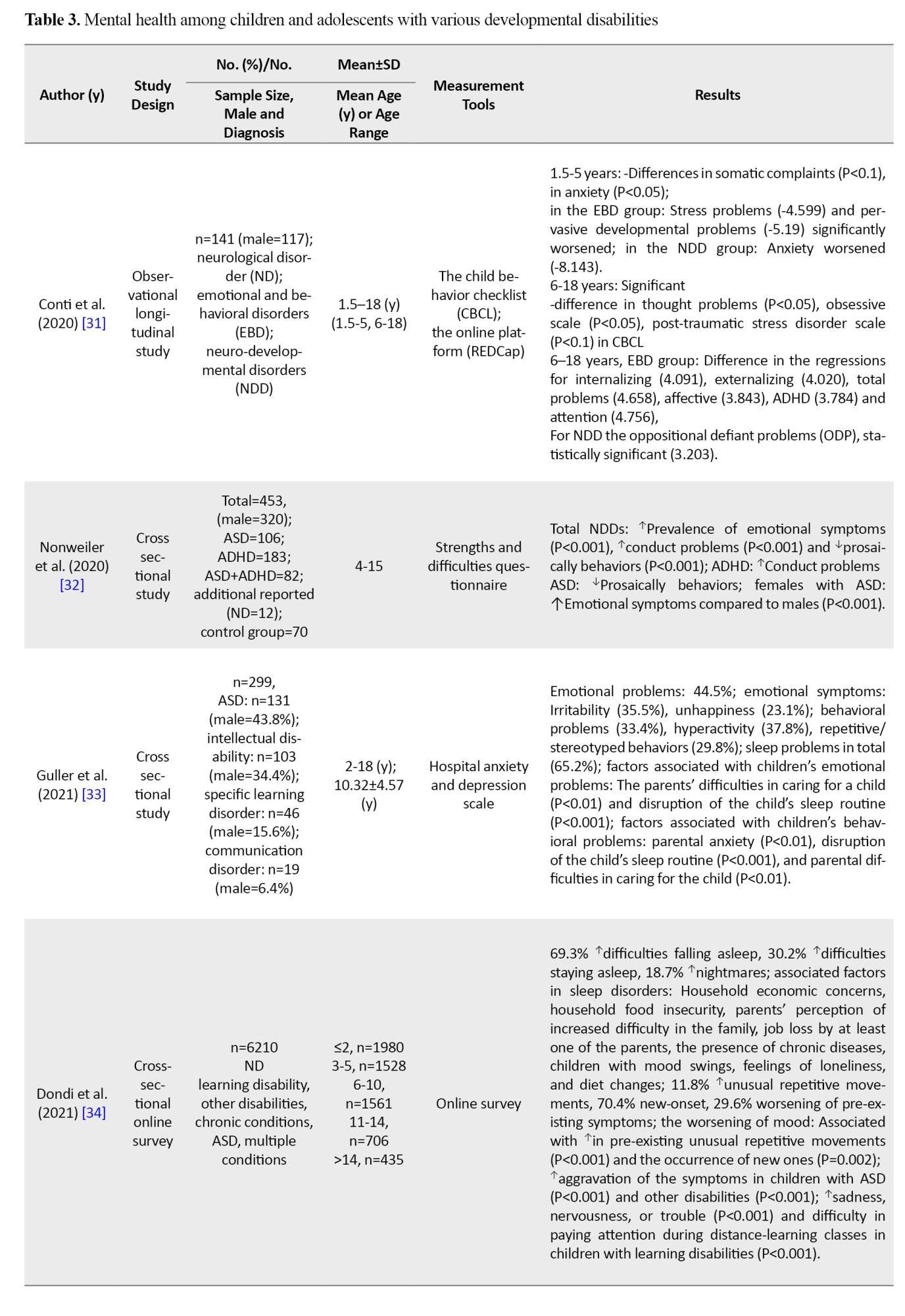

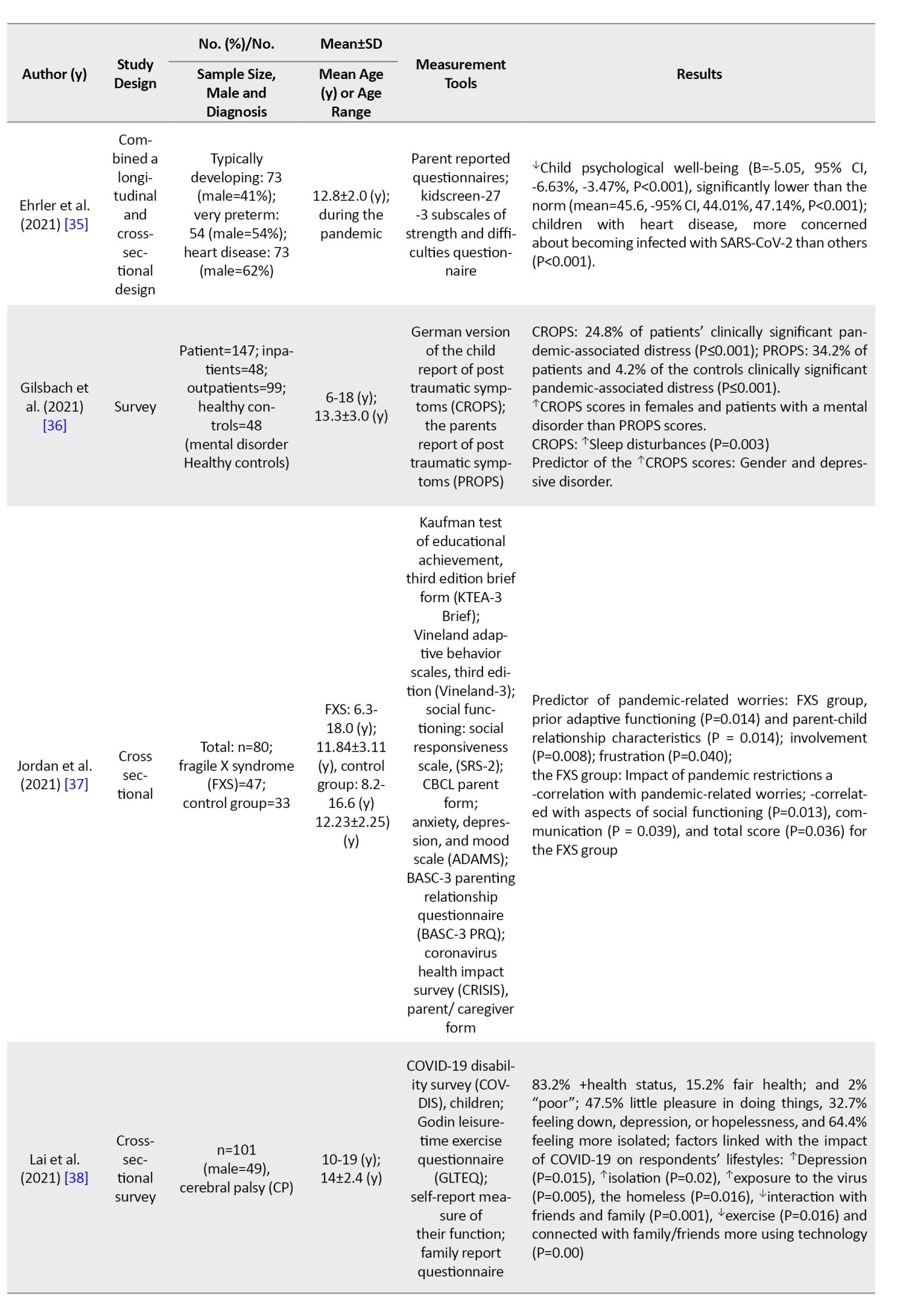

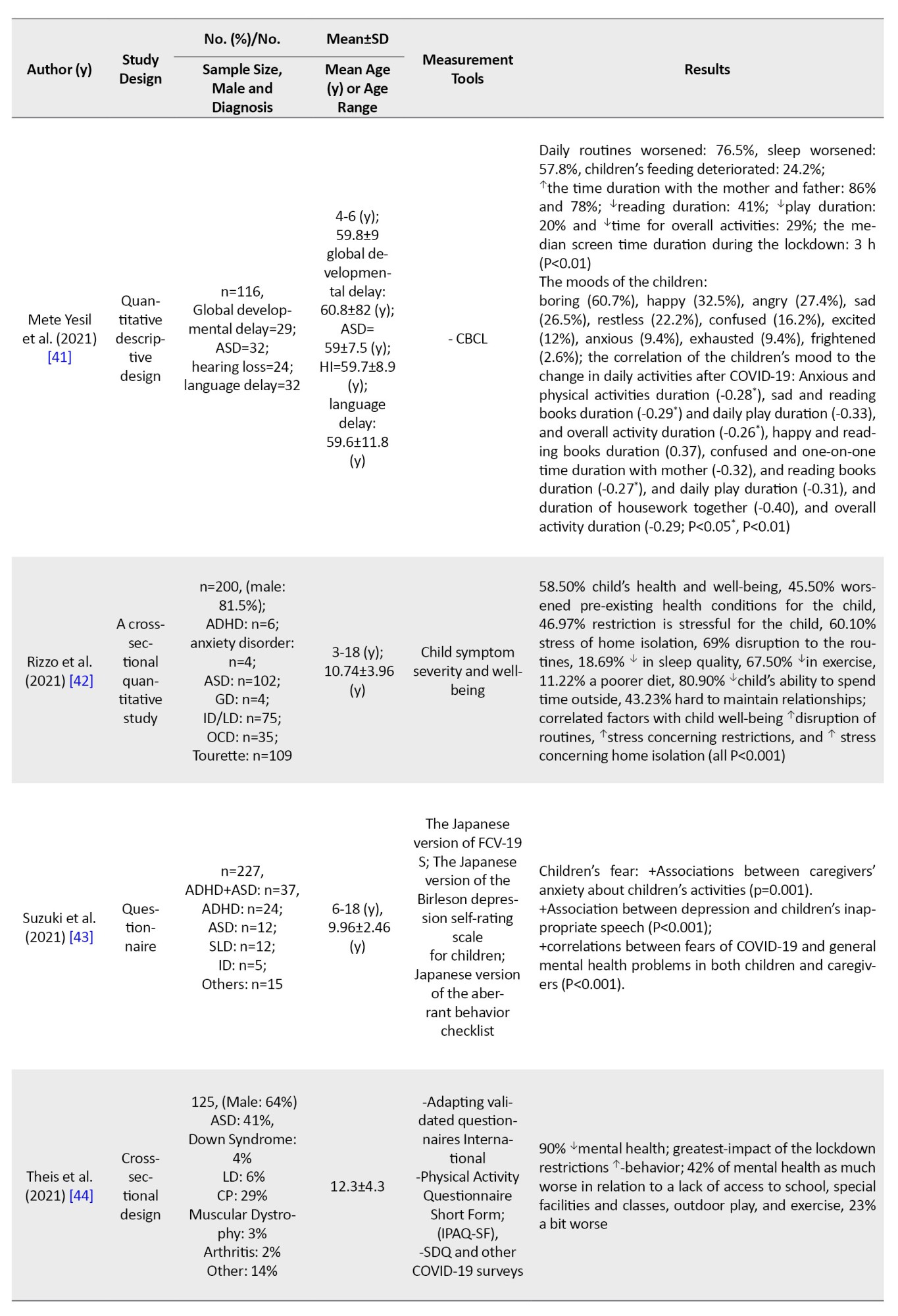

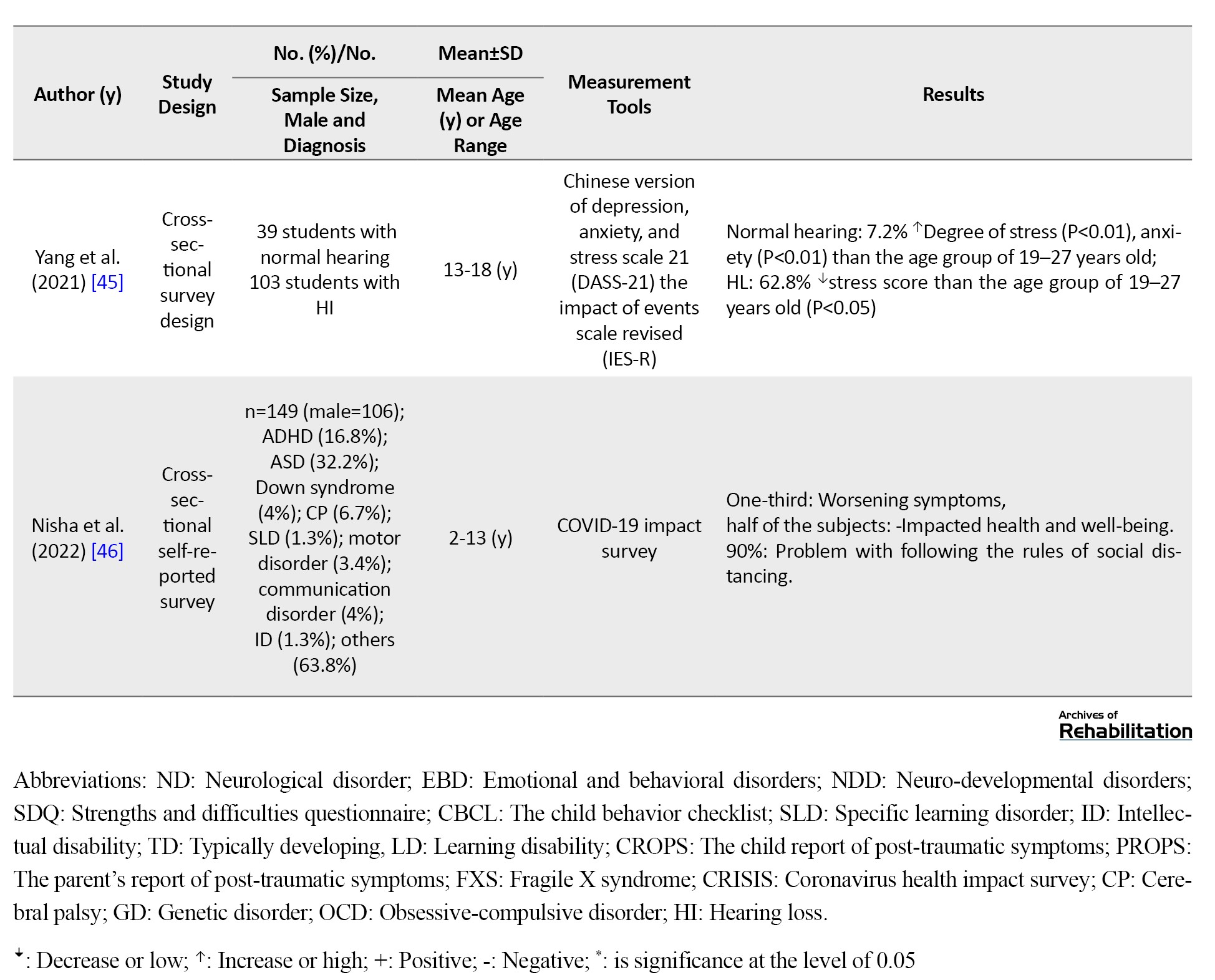

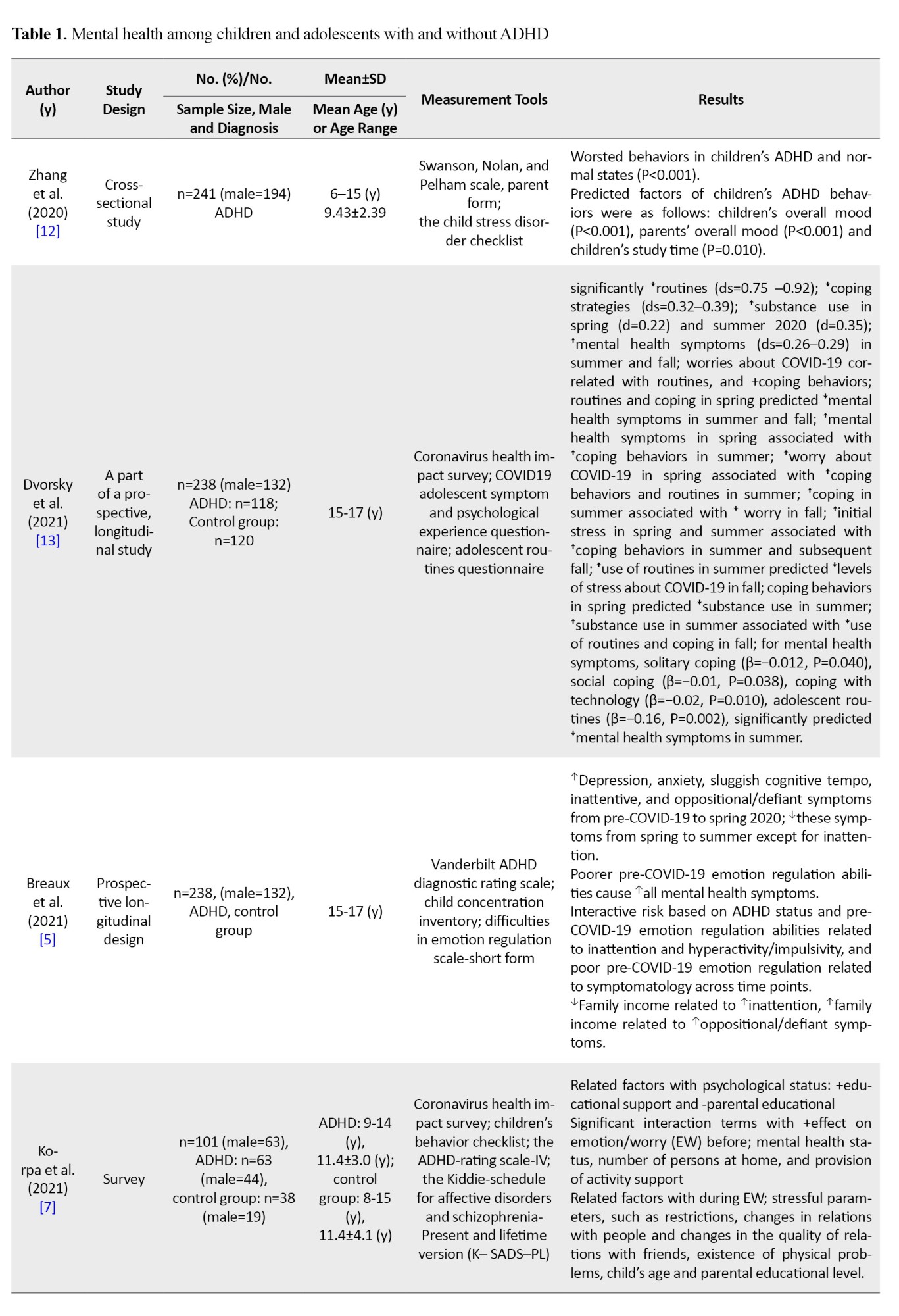

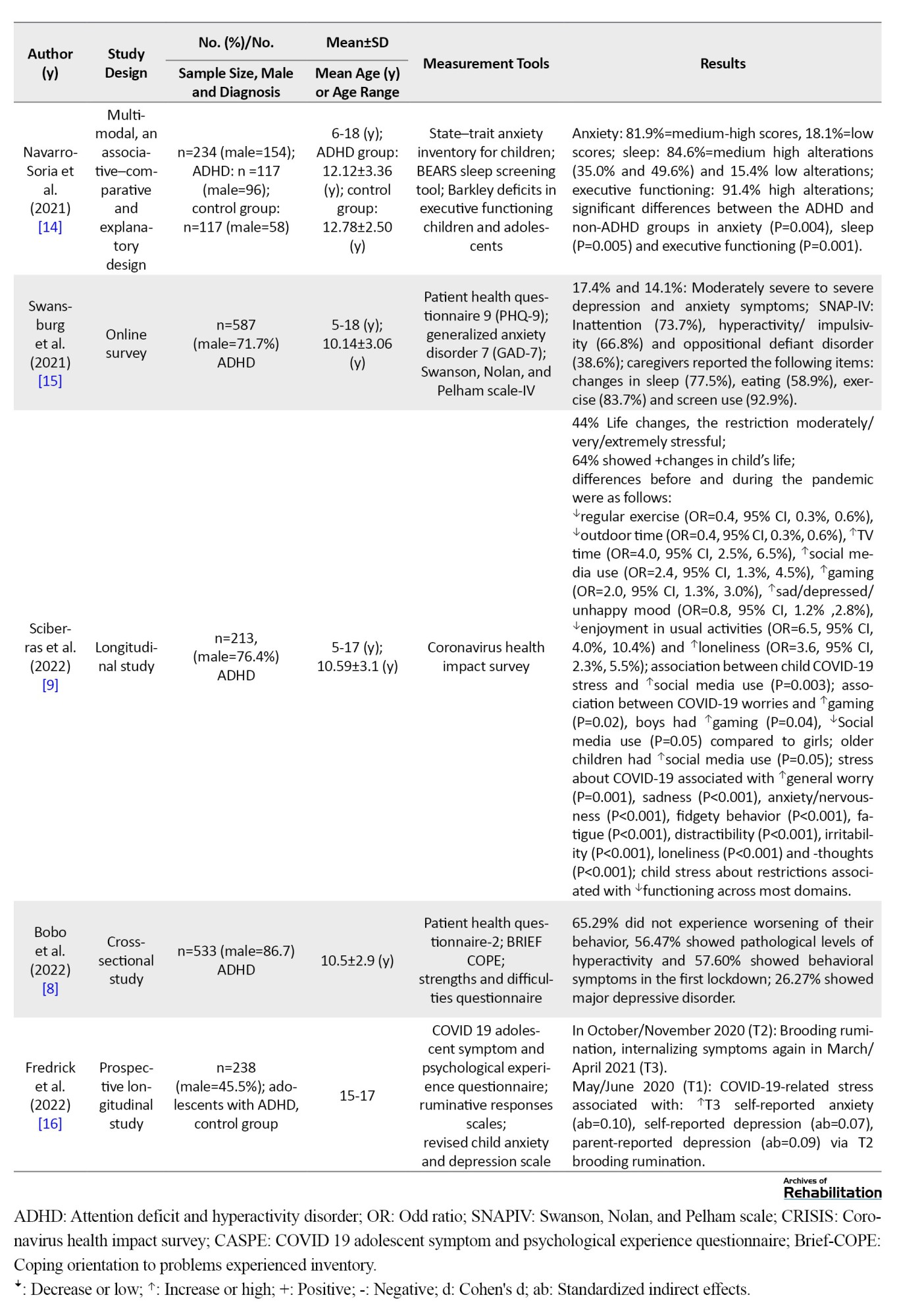

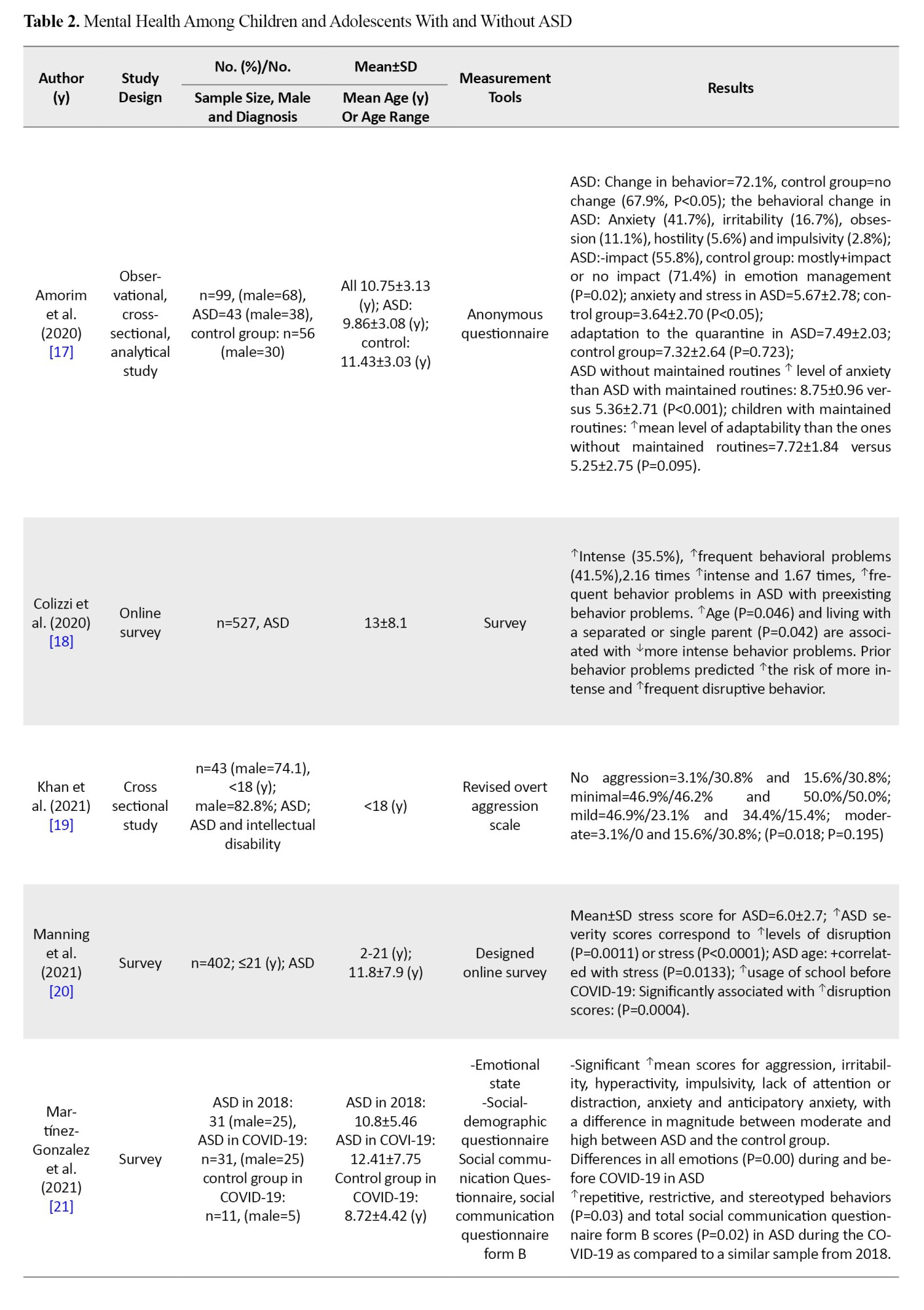

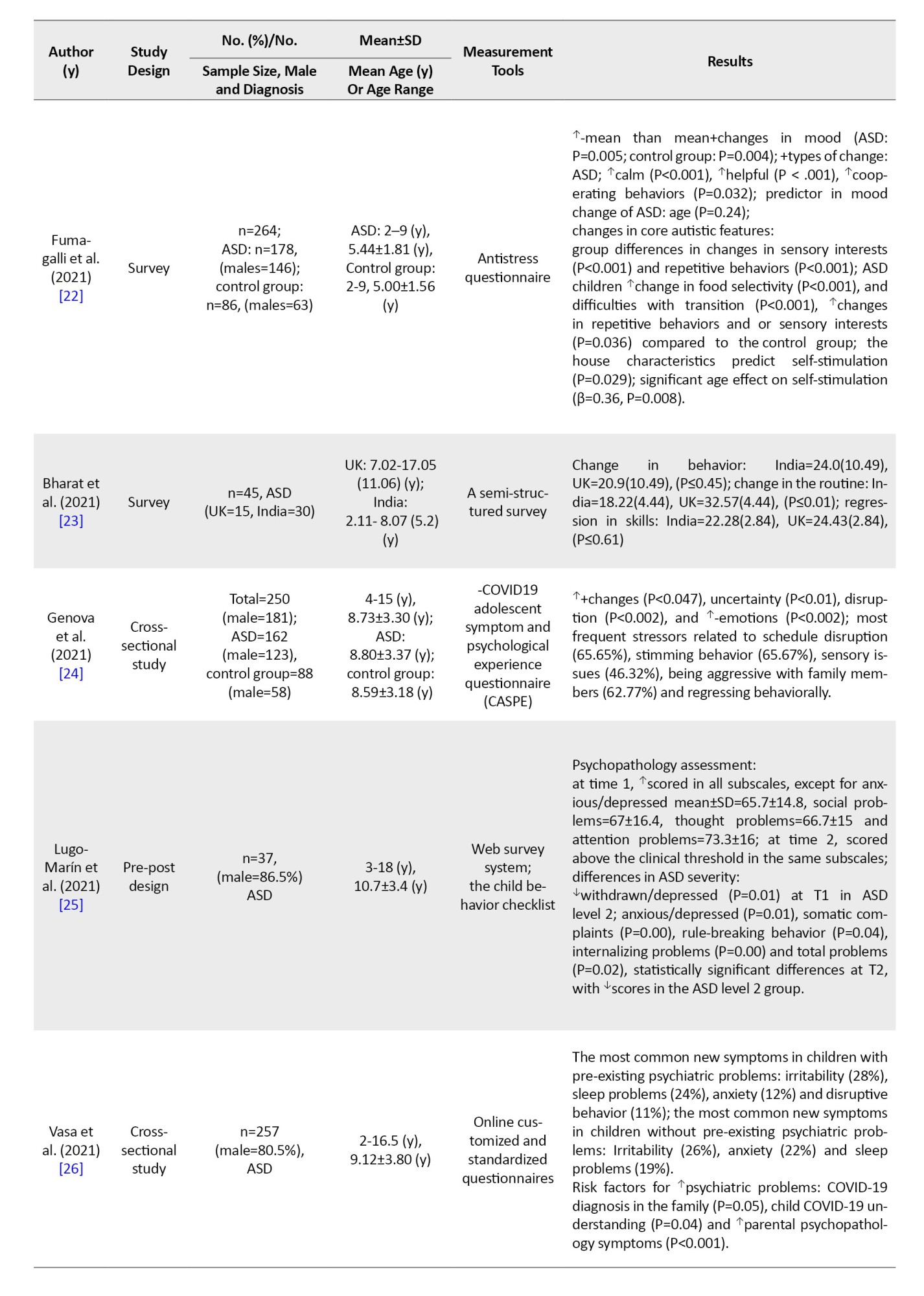

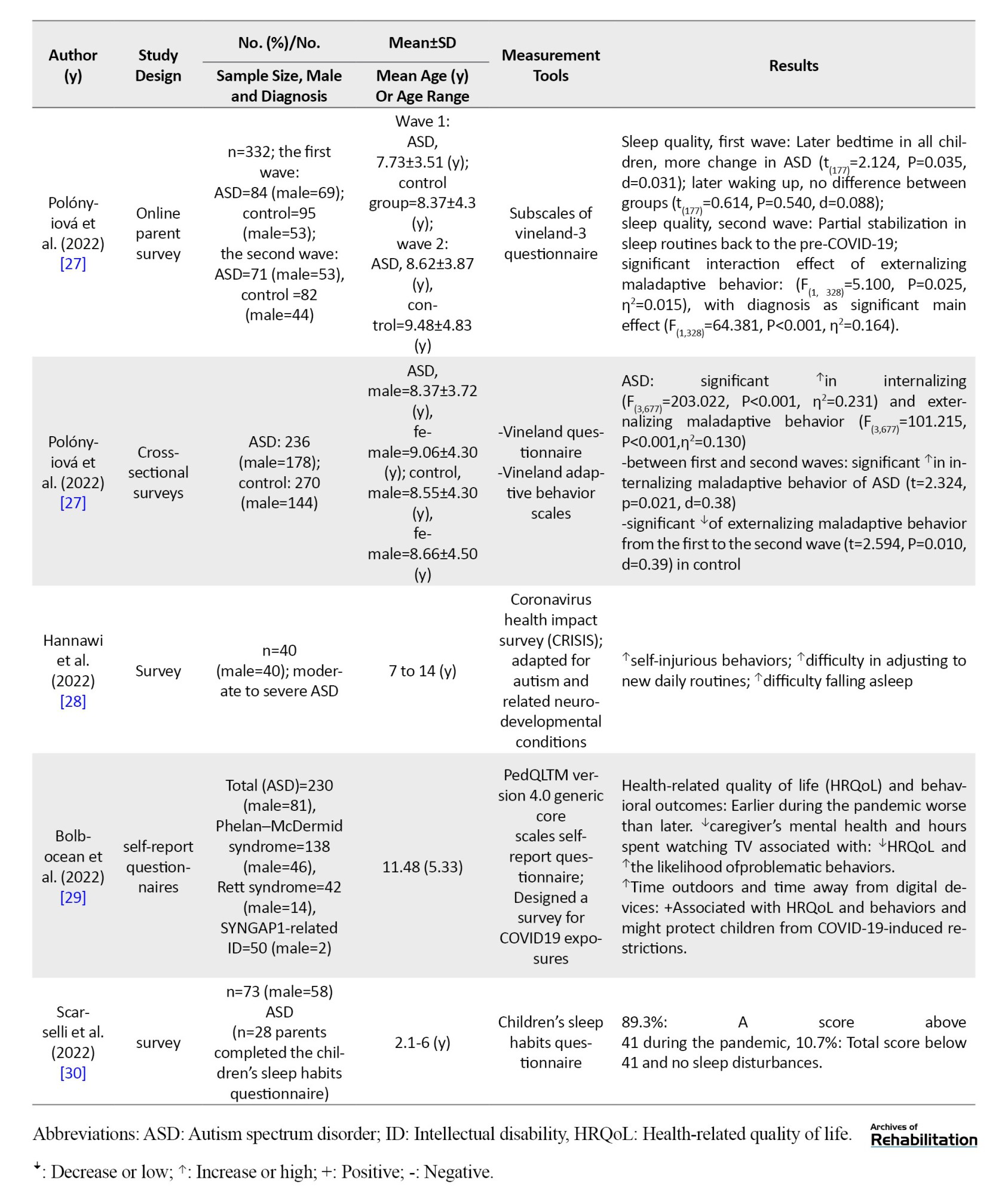

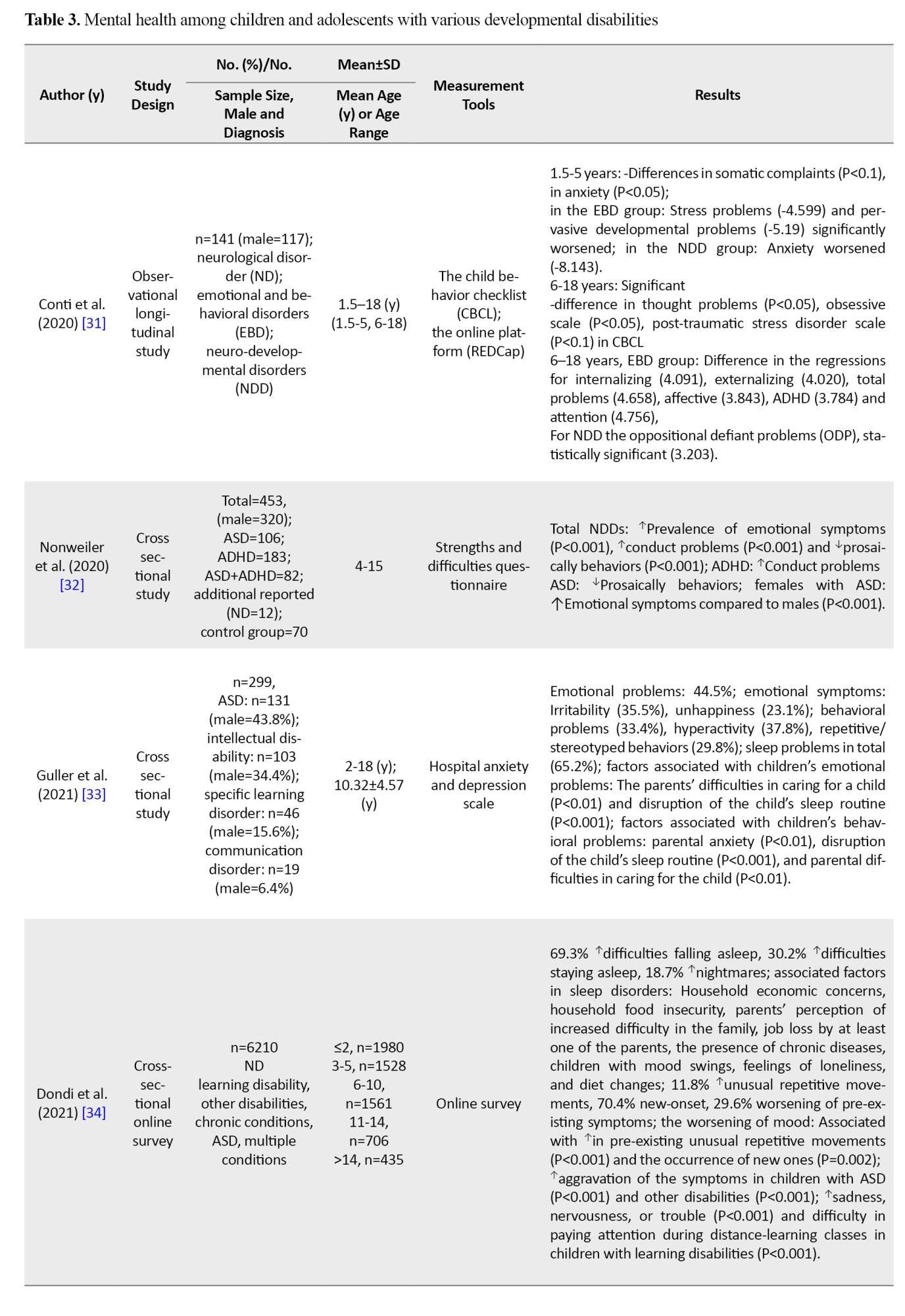

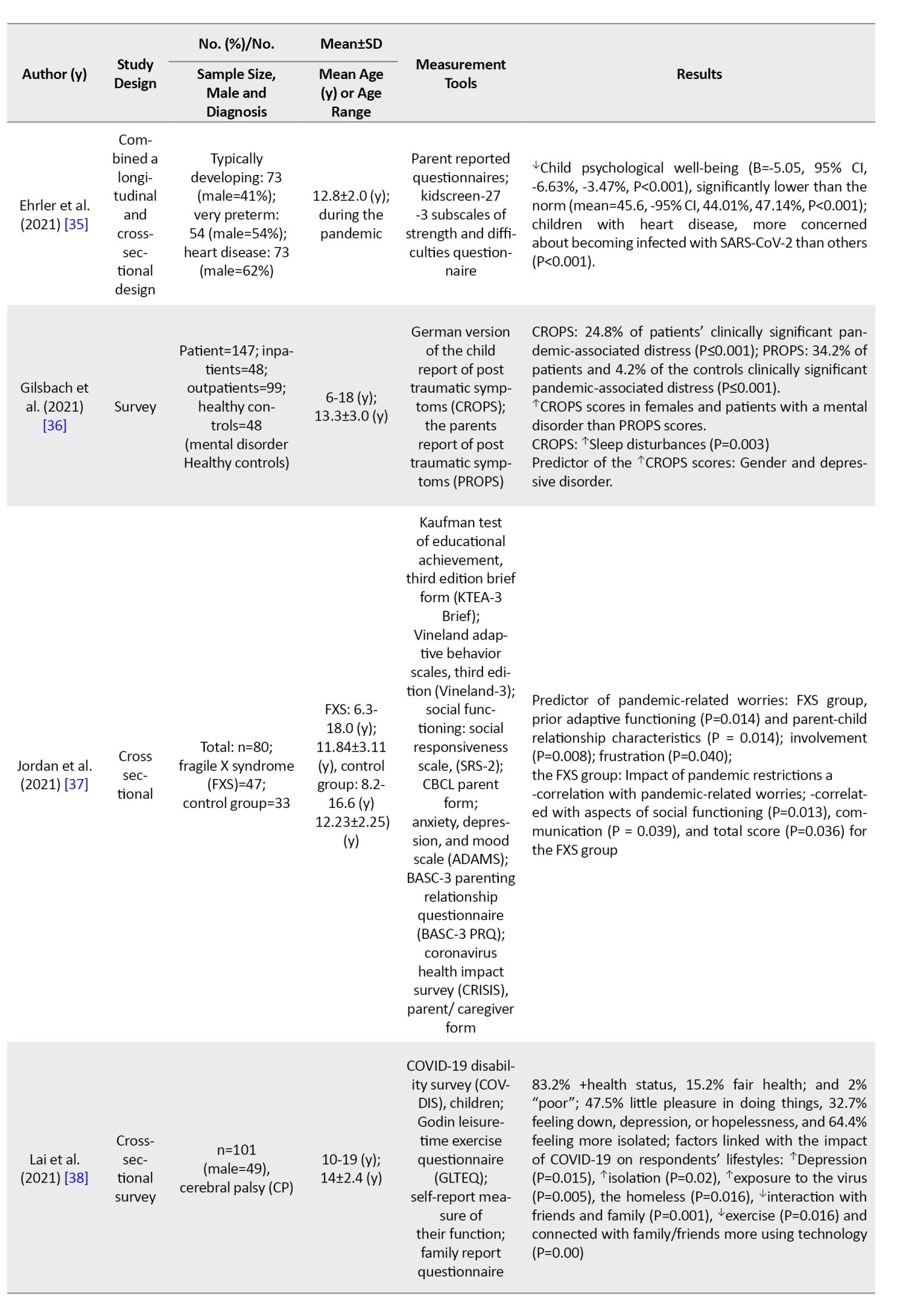

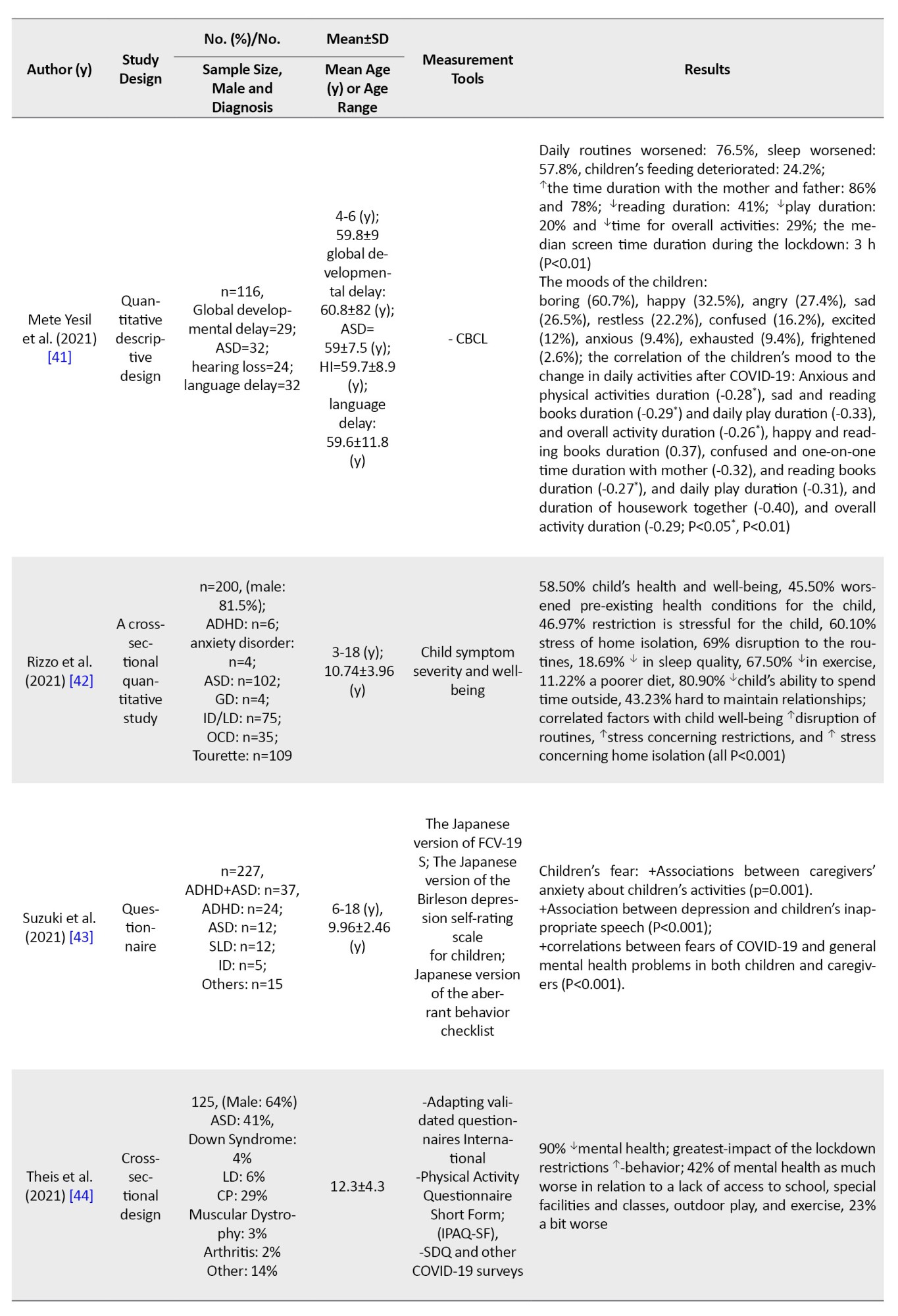

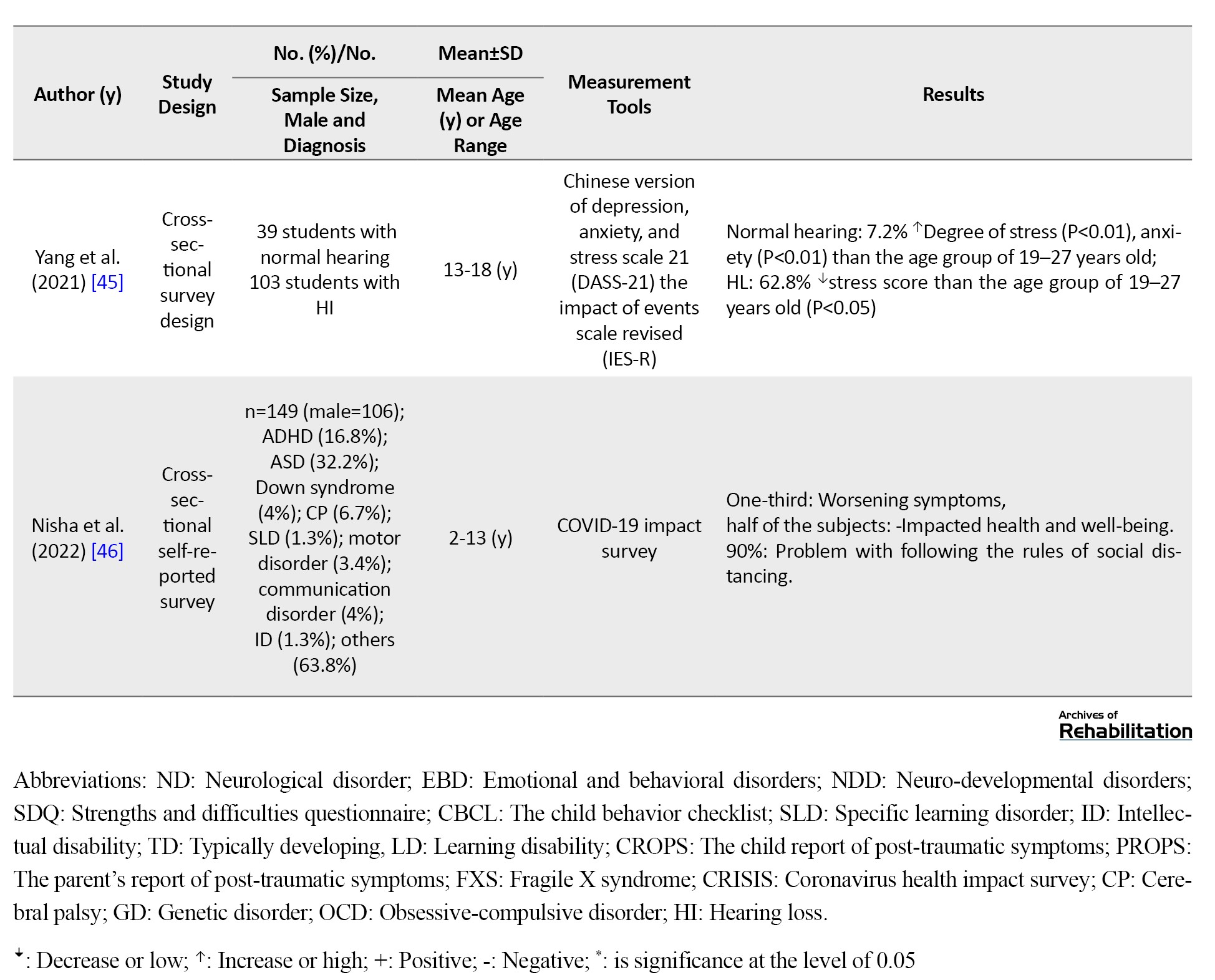

The articles were divided into three categories as follows: articles about the mental health of children with ADHD, ASD and other developmental disabilities. Tables 1, 2 and 3 shows the results of the selected studies by two reviewers (Fatemeh Hassanati, Fatin Soleimani).

The extracted data, such as the name of the first author, study design, sample size, age, measurement tools and outcomes included prevalence, correlations, and predictive factors by reporting mean differences, mean percentages, P, odds ratios and so on.

Results

Search results

We used preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and a meta-analyses flow diagram for searching and selecting appropriate studies. The diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Characteristics of included studies

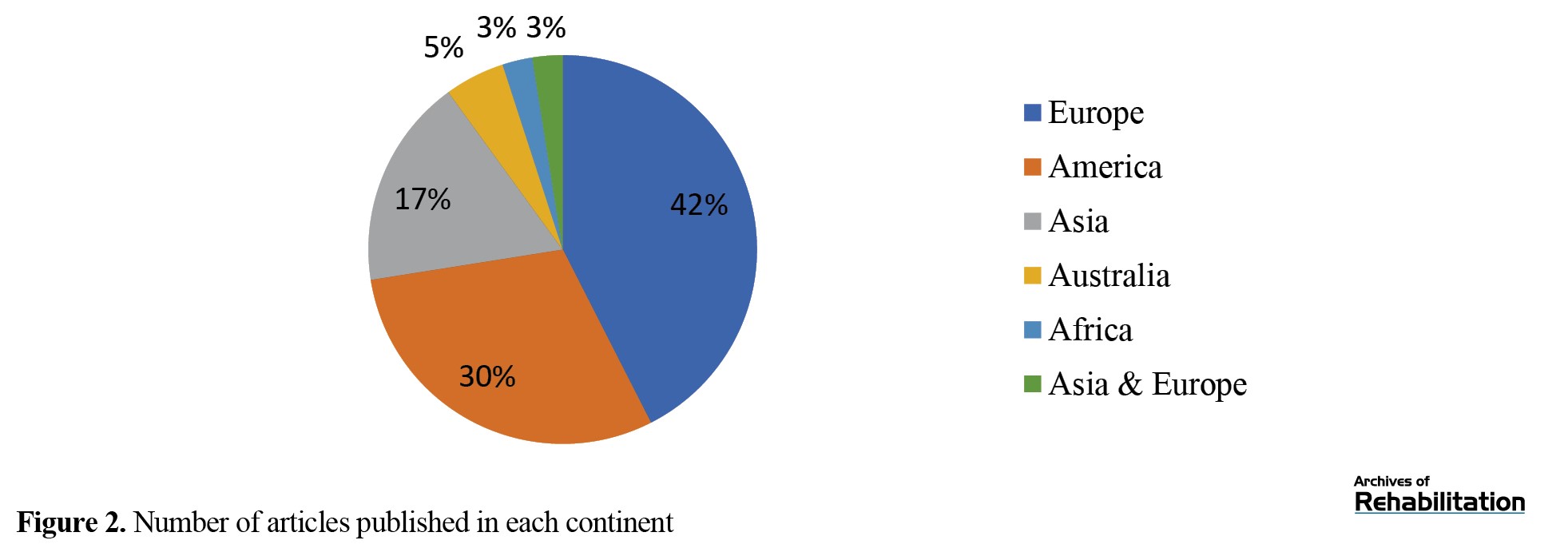

Tables 1, 2 and 3 present the characteristics of all 40 included articles [5, 7, 8, 9, 12-47]. The total number of participants in all 40 studies was about 14 212 people without a control group and about 15 279 people with a control group. Six studies (15%) were published in 2020, 24 articles (60%) in 2021 and 10 studies (25%) in 2022. Most studies were published in the United States (n=10[25%]) and Italy (n=6[15%]). Figure 2 shows the distribution of articles published in each continent.

Mental health outcomes among children and adolescents with and without ADHD

The results showed that 22.5% (n=9) of studies provided data about mental health status among children and adolescents with and without ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). Across most of the studies, the prevalence of behavior problems during COVID-19 was significantly increased compared to pre-COVID-19 [9, 12, 14, 15]. One longitudinal study reported significant change across these time points for every mental health symptom domain. Hyperactivity did not show the change [5] (more details are in Table 1). One study showed no differences in the emotion/worry status in the ADHD group compared with the control group [7]. On the other hand, a few studies reported that about two third of children don’t experience any worsening behaviors [8], or have positive changes in their behaviors [9]. Dvorsky et al. performed a longitudinal study in the spring, summer, and fall of 2020. The results suggested mixed patterns of adjustment during the COVID-19 (Table 1) [13]. The prevalence of moderate to severe anxiety was 14.1% [15] to 81.9% [14] and low anxiety was 18.1% [14] in ADHD. There were significant differences between the ADHD and control groups’ anxiety (P=0.004). Anxiety can affect sleep (P=0.001) and executive functions (P=0.001) [14]. In addition, the prevalence of change in sleep patterns was from 15.4% to 77.5% [14, 15]. Furthermore, the prevalence of inattention, hyperactivity and oppositional symptoms were 73.7%, 66.8% and 38.6%, respectively [15]. Another study revealed that reduced sleep time and increasing the processed food were positively correlated with hyperactivity as well as ADHD symptoms (P<0.01) [15]; however, the reduced exercise was negatively correlated with hyperactivity (P<0.05) [15]. Increasing watching TV and video gaming were positively correlated with inattention (P<0.05) [15]. Some factors predicted the children’s ADHD behaviors, such as the general temperament of children (B=0.17, 95% CI, 0.11%, 0.23%), parents’ general temperament state (B=0.13, 95% CI, 0.06%, 0.20%) and the length of time the child studies (B=−0.09, 95% CI, −0.15%, −0.02%) [12]. Emotion regulation abilities in pre-COVID-19 were predictive of all mental health symptoms before COVID-19 (Table 1) [5].

Mental health outcomes among children and adolescents with and without ASD

According to Table 2, a total of 15 studies (37.5%) provided data about the consequences of mental health among children and adolescents with and without ASD during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some studies reported a higher level of some emotional status and autistic symptoms in children with ASD during the pandemic relative to the pre-pandemic [17, 18, 27]. One study reported that children with ASD were negatively affected by a change in routines more than three times [18]. Other studies showed that there were more negative mood changes than positive changes [18, 22, 24]; however, one study showed a decrease or no change in the grade of aggression during the pandemic, but this reduction was not significant (P=0.30) [19]. One of the mental health statuses reported in the included studies was anxiety, with prevalence ranging from 12% to 22% [26] that was significantly different between ASD and control groups (P<0.05) [17, 21]. The prevalence of sleep disruption was from 19% to 24% [26]. The findings of the included studies revealed that behavioral problems were correlated with changes in routines (r=0.446, P<0.01), decline in skills (r=0.750, P<0.01), and parental stress factors (r=0.370, P<0.05) [23]. In addition, a higher level of ASD severity be consistent with higher levels of disturbance or stress for ASD individuals [17]. In some studies, stress was higher during the restriction, which corresponded to higher ASD severity scores (P<0.0001), age (P=0.013) [17, 20] and schedule disturbance [24]. Moreover, the stress score was a significant difference between ASD and control groups (P<0.05) [17]. Furthermore, vasa et al. determined the risk factors for increased mental health symptoms that are presented in Table 2 [26].

Mental health outcomes among children and adolescents with other developmental disabilities

The participants in 40% of studies (n=16) were from various developmental disabilities the mental health of various groups of developmental disabilities such as learning disabilities, intellectual disabilities, genetic syndromes, hearing loss, fragile X syndrome, cerebral palsy (CP), ASD, ADHD and so on. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Several studies investigated the various aspects of emotional and behavioral changes in diverse groups, so achieving a unique conclusion was difficult. The prevalence of sleep change ranged from 18.69% to 69.3% [33, 34, 36, 39, 42]. Parents reported more sleep disturbances in children during the COVID-19 pandemic (P=0.003) [36]. The well-being of children significantly decreases during the COVID-19 (B=−5.05, 95% CI, −6.63%, −3.47%) [36]. Two studies reported that the overall health of the child is affected by COVID-19 ranging from 58.5% [42] to 76.9% [39]. Furthermore, the prevalence of daily routine changes and worse emotions was from 69% to 76.5% [41] and from 42% to 60.61% [32, 33, 42].

Guller et al. (2021) investigated the associated factors with emotional and behavioral problems in children with specific learning disorders, intellectual disabilities, and communication disorders (Table 3) [33]. Another study reported that negative mood change was associated with increasing pre-existing abnormal repetitive movements and the incidence of new repetitive movements in children with a chronic condition, learning disabilities, ASD, and multiple conditions [34]. A study reported that stress problems and pervasive developmental problems in children with emotional behavioral disorders aged 1.5 to 5 years old significantly deteriorated. Although, anxiety problem was observed in the group of neurodevelopmental disorders. More details about other groups are provided in Table 3 [31]. A study that included children with mental disorders, reported that age was negatively associated with psychological status. Female gender and depressive symptoms were predictors of psychological distress [36]. One study with various groups of developmental disabilities such as anxiety disorder, ASD, genetic disorders, intellectual disabilities, and obsessive-compulsive disorders reported correlated factors with a child’s well-being, including increased disruption of routines, stress about restrictions, and stress about home isolation (P<0.001) [42].

Some studies reported that sleep quality decreased during the pandemic [34, 37, 39, 41]. Dondi et al. (2021) determined the associated factors in sleep disorders that were presented in Table 3 [34].

Discussion

This scoping review was regarding the mental health status of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results indicated that COVID-19 and its restrictions impacted psychological behaviors (i.e. anxiety, sadness, psychological well-being), changes in lifestyles (i.e. sleep, eating, relations, exercise, screen time, social media, routines, and coping strategies), and some special symptoms (i.e. hyperactivity, attention deficit, and oppositional symptoms) in children and adolescents with ADHD [7, 9, 12, 15, 16]. These results are consistent with Bobo et al. (2022) [8]. Despite this, the longitudinal studies did not show a stable pattern of behaviors and mental status in adolescents with ADHD during this time [5, 13]. On the other side, some studies reported the deterioration of behaviors and their related factors in children and adolescents with ADHD [5, 12-15]. Individuals with ADHD have poor adaptability to stressful situations, such as COVID-19. Quarantine and staying at home caused a decrease in routines. In addition, they are susceptible to having poor coping strategies. Changes in routines and poor coping strategies may influence their behaviors; therefore, they need more time to adjust to the changes in situations [7].

This review also highlighted the presence of several mental health changes such as disruptive behavior, anxiety disorder, irritability, sleep problems, and disruptive behavior in children and adolescents with ASD during COVID-19 [18]. These results are consistent with Narzisi et al. (2013) study in which ASD individuals were more vulnerable to routine disruptions [48], so parents had difficulty managing their children’s activities. The difficulty of managing children’s routines will cause greater stress for parents. Studies showed that routine disruption [24] and parental stress [23] were the predictors of mood change and behavioral problems. Another reason for the increasing autistic maladaptive behavior of these children is an unexpected lack of access to healthcare during the COVID-19 [18].

The certain behaviors observed in individuals with ASD, such as sensory issues, stimming behaviors, and repetitive behavior were worsened [17, 21, 22]. The presence of these behaviors can be a compensatory mechanism against internal or external difficulty, such as anxiety [17, 21, 24]. Younger age was a predictor of appearing positive mood changes and reduction of behavioral problems [22]. It may be because younger children naturally are less aware of the condition than older children. Besides that, establishing new routines is more acceptable and tolerable in younger children [22]. In addition, children with ASD get information about COVID-19 through news, social media, and hearing from family members. Achieving the correct information and understanding the news can be difficult for them, thereby causing some psychiatric problems such as anxiety [26]. Other reasons for increasing psychiatric symptoms in children with ASD included low income, parental depression, and anxiety [26]. This finding is consistent with evidence in other populations during COVID-19 [26, 49]. Breaux et al. (2021) reported that low income was related to increased inattention, and high income is related to increased oppositional symptoms in adolescents with ADHD [5]. Families with low income may be more vulnerable to being jobless, so the level of parental depression and sense of worry may increase the child’s psychiatric symptoms [20]. Furthermore, low family income is associated with difficulty in accessing healthcare services.

In the field of other neurodevelopmental disabilities, one study has shown a higher prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems (64.1% and 77.1%) in ASD and (51.5% and 61.2%) in ID groups during the COVID-19 [33]. Previous studies reported fewer emotional and behavioral problems (about 50%) in children with ASD and ID [50]. According to the Guller et al. (2021) study, the disruption of sleep routines is a key predictor of emotional and behavioral problems [33]. Poor quality sleep has negative effects on behavioral and emotional symptoms, especially in children with neurodevelopmental disorders [51]. In addition, school closures and social isolation disrupted children’s daily patterns, which reduced the quality of children’s sleep [33, 34, 39], a poorer diet [39], reduced physical activity, and increasing the use of social media, TV and gaming [39]. Another reason for the decrease in their mental health status could be the homeschooling [42] and inaccessibility to facilities and specialist teams such as the rehabilitation team [44].

Limitations

In this review, we found some shortcomings in the existing studies; Most of the studies focused on ASD and ADHD. We suggested that more specific studies on unique groups of developmental disabilities are essential; Most studies were cross-sectional; Therefore, future longitudinal research is needed to increase knowledge and examine the long-term effects of the epidemic on the mental health of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities. In addition, a systematic review is useful to obtain detailed information in this field.

Conclusion

The present scoping review showed that most children and adolescents with developmental disabilities experienced deterioration in their mental health status due to restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Facilitation of access to rehabilitation and educational services, and parental training is essential to manage these stressful situations. In addition, the role of financial issues in managing mental health problems and increasing the well-being of children and adolescents and their caregivers is crucial. Governments and policymakers should think about long-term post-COVID-19 psychological consequences and provide proper intervention support for vulnerable groups and their families.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.314).

Funding

This article was financially supported by the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Grant No. 2871).

Authors' contributions

Idea of the article: Farin Soleimani; Conceptualization and writing–original draft: Fatemeh Hassanati, Peymaneh Shirinbayan and Somayeh Amiri-Arimi; Record screening and extraction: Zahra Ghorbanpour, Zahra Nobakht and Farin Soleimani; Methodology: Mohammad Saatchi; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article are grateful for the financial support of the University of social welfare and rehabilitation sciences for this project.

Refrences

COVID-19 as a global pandemic has created new stressors for humans worldwide. The extended period of quarantine increased psychological problems, such as post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, depression, low mood and irritability in adults and children [1]. Meanwhile, people with disabilities, including physical, mental, intellectual, or sensory disabilities, are highly likely to experience worse outcomes and greater health needs during the COVID-19 [2].

In these groups, children and adolescents should be provided with adequate support and may be more sensitive to the psychosocial health effects of the COVID-19 pandemic than others [3], because they are in a golden time of their development. Furthermore, approximately half of all mental health conditions are developed before the age of 14 years. One study performed a systematic review of the prevalence of mental health problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Meta-analysis results showed the prevalence of depression was 29%, anxiety was 26%, sleep disorders were 44%, and post-traumatic stress symptoms were 48%. Children and boys had a lower prevalence of depression and anxiety compared to adolescents and girls [4]. Children and adolescents with a background of mental health disorders, such as autism spectrum disorders (ASD), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and so on, may have more mental health problems during the pandemic [5]. Studies have shown that long school closures, extreme social isolation, and its consequences have caused mental health problems and these factors may have imposed elevated levels of emotional distress [6]. Also, sudden changes in daily routines were associated with various outcomes in children’s mental health [7, 8, 9]. Based on our investigations and findings, most of the available studies in this field are about the typically developing subjects [10]. Therefore, comprehensive knowledge and resources about mental health issues in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities are essential to support them and their caregivers as well as to manage such crises in the future.

The purpose of this review is to determine the prevalence, correlations, and predicting factors of mental health problems in three groups of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities, namely ASD, ADHD, and other developmental disabilities, including cerebral palsy, learning disabilities, Down syndrome, and so on, during the COVID-19 pandemic and their comparison pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic.

Materials and Methods

This was a scoping review study. Scope review is a type of article review suitable for more general-purpose reviews. Therefore, reports should be different from systematic reviews [11]. The main goal of the research is to study mental health outcomes in children and adolescents with developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. We reviewed articles according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses- scoping review guidelines [11]. We included experimental and observational studies published between January 1, 2020, and September 1, 2022. We systematically searched the ISI, PubMed, and Scopus databases. We used MeSH terms and entered the terms into the title/abstract search. The language of the included studies was English. The search terms were as follows: “COVID-19”, “SARS-CoV-2”, “Mental Health”, “Intellectual Disability”, “Developmental Disabilities”, “Learning Disabilities”, “Neurodevelopmental Disorders”, “Autistic Disorder”, “Autism Spectrum Disorder”, “Attention Deficit Disorder with Hyperactivity”, “Cerebral Palsy”, “Stuttering”, “Language Disorders”, “Mental Retardation”, “Communication Disorders”, “Dyslexia”, “ADHD”, “Cognition Disorders”, “Dyscalculia”, and “Agraphia”.

We selected self-report or caregiver report scales that were specifically designed for mental health assessment. In addition, we excluded studies about adults with disabilities or typically developing children. Articles that were not in our research timeline were excluded from the study.

By searching the three selected databases, a total of 883 articles were obtained. Duplicate articles (n=261) were removed. Subsequently, two reviewers independently (Zahra Ghorbanpour, Zahra Nobakht) screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles (n=622) in two stages. First, the titles and abstracts of articles were screened. Finally, if the two researchers did not agree, the third researcher (Fatemeh Hassanati) made the final decision.

The articles were divided into three categories as follows: articles about the mental health of children with ADHD, ASD and other developmental disabilities. Tables 1, 2 and 3 shows the results of the selected studies by two reviewers (Fatemeh Hassanati, Fatin Soleimani).

The extracted data, such as the name of the first author, study design, sample size, age, measurement tools and outcomes included prevalence, correlations, and predictive factors by reporting mean differences, mean percentages, P, odds ratios and so on.

Results

Search results

We used preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and a meta-analyses flow diagram for searching and selecting appropriate studies. The diagram is shown in Figure 1.

Characteristics of included studies

Tables 1, 2 and 3 present the characteristics of all 40 included articles [5, 7, 8, 9, 12-47]. The total number of participants in all 40 studies was about 14 212 people without a control group and about 15 279 people with a control group. Six studies (15%) were published in 2020, 24 articles (60%) in 2021 and 10 studies (25%) in 2022. Most studies were published in the United States (n=10[25%]) and Italy (n=6[15%]). Figure 2 shows the distribution of articles published in each continent.

Mental health outcomes among children and adolescents with and without ADHD

The results showed that 22.5% (n=9) of studies provided data about mental health status among children and adolescents with and without ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 1). Across most of the studies, the prevalence of behavior problems during COVID-19 was significantly increased compared to pre-COVID-19 [9, 12, 14, 15]. One longitudinal study reported significant change across these time points for every mental health symptom domain. Hyperactivity did not show the change [5] (more details are in Table 1). One study showed no differences in the emotion/worry status in the ADHD group compared with the control group [7]. On the other hand, a few studies reported that about two third of children don’t experience any worsening behaviors [8], or have positive changes in their behaviors [9]. Dvorsky et al. performed a longitudinal study in the spring, summer, and fall of 2020. The results suggested mixed patterns of adjustment during the COVID-19 (Table 1) [13]. The prevalence of moderate to severe anxiety was 14.1% [15] to 81.9% [14] and low anxiety was 18.1% [14] in ADHD. There were significant differences between the ADHD and control groups’ anxiety (P=0.004). Anxiety can affect sleep (P=0.001) and executive functions (P=0.001) [14]. In addition, the prevalence of change in sleep patterns was from 15.4% to 77.5% [14, 15]. Furthermore, the prevalence of inattention, hyperactivity and oppositional symptoms were 73.7%, 66.8% and 38.6%, respectively [15]. Another study revealed that reduced sleep time and increasing the processed food were positively correlated with hyperactivity as well as ADHD symptoms (P<0.01) [15]; however, the reduced exercise was negatively correlated with hyperactivity (P<0.05) [15]. Increasing watching TV and video gaming were positively correlated with inattention (P<0.05) [15]. Some factors predicted the children’s ADHD behaviors, such as the general temperament of children (B=0.17, 95% CI, 0.11%, 0.23%), parents’ general temperament state (B=0.13, 95% CI, 0.06%, 0.20%) and the length of time the child studies (B=−0.09, 95% CI, −0.15%, −0.02%) [12]. Emotion regulation abilities in pre-COVID-19 were predictive of all mental health symptoms before COVID-19 (Table 1) [5].

Mental health outcomes among children and adolescents with and without ASD

According to Table 2, a total of 15 studies (37.5%) provided data about the consequences of mental health among children and adolescents with and without ASD during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some studies reported a higher level of some emotional status and autistic symptoms in children with ASD during the pandemic relative to the pre-pandemic [17, 18, 27]. One study reported that children with ASD were negatively affected by a change in routines more than three times [18]. Other studies showed that there were more negative mood changes than positive changes [18, 22, 24]; however, one study showed a decrease or no change in the grade of aggression during the pandemic, but this reduction was not significant (P=0.30) [19]. One of the mental health statuses reported in the included studies was anxiety, with prevalence ranging from 12% to 22% [26] that was significantly different between ASD and control groups (P<0.05) [17, 21]. The prevalence of sleep disruption was from 19% to 24% [26]. The findings of the included studies revealed that behavioral problems were correlated with changes in routines (r=0.446, P<0.01), decline in skills (r=0.750, P<0.01), and parental stress factors (r=0.370, P<0.05) [23]. In addition, a higher level of ASD severity be consistent with higher levels of disturbance or stress for ASD individuals [17]. In some studies, stress was higher during the restriction, which corresponded to higher ASD severity scores (P<0.0001), age (P=0.013) [17, 20] and schedule disturbance [24]. Moreover, the stress score was a significant difference between ASD and control groups (P<0.05) [17]. Furthermore, vasa et al. determined the risk factors for increased mental health symptoms that are presented in Table 2 [26].

Mental health outcomes among children and adolescents with other developmental disabilities

The participants in 40% of studies (n=16) were from various developmental disabilities the mental health of various groups of developmental disabilities such as learning disabilities, intellectual disabilities, genetic syndromes, hearing loss, fragile X syndrome, cerebral palsy (CP), ASD, ADHD and so on. The results are summarized in Table 3.

Several studies investigated the various aspects of emotional and behavioral changes in diverse groups, so achieving a unique conclusion was difficult. The prevalence of sleep change ranged from 18.69% to 69.3% [33, 34, 36, 39, 42]. Parents reported more sleep disturbances in children during the COVID-19 pandemic (P=0.003) [36]. The well-being of children significantly decreases during the COVID-19 (B=−5.05, 95% CI, −6.63%, −3.47%) [36]. Two studies reported that the overall health of the child is affected by COVID-19 ranging from 58.5% [42] to 76.9% [39]. Furthermore, the prevalence of daily routine changes and worse emotions was from 69% to 76.5% [41] and from 42% to 60.61% [32, 33, 42].

Guller et al. (2021) investigated the associated factors with emotional and behavioral problems in children with specific learning disorders, intellectual disabilities, and communication disorders (Table 3) [33]. Another study reported that negative mood change was associated with increasing pre-existing abnormal repetitive movements and the incidence of new repetitive movements in children with a chronic condition, learning disabilities, ASD, and multiple conditions [34]. A study reported that stress problems and pervasive developmental problems in children with emotional behavioral disorders aged 1.5 to 5 years old significantly deteriorated. Although, anxiety problem was observed in the group of neurodevelopmental disorders. More details about other groups are provided in Table 3 [31]. A study that included children with mental disorders, reported that age was negatively associated with psychological status. Female gender and depressive symptoms were predictors of psychological distress [36]. One study with various groups of developmental disabilities such as anxiety disorder, ASD, genetic disorders, intellectual disabilities, and obsessive-compulsive disorders reported correlated factors with a child’s well-being, including increased disruption of routines, stress about restrictions, and stress about home isolation (P<0.001) [42].

Some studies reported that sleep quality decreased during the pandemic [34, 37, 39, 41]. Dondi et al. (2021) determined the associated factors in sleep disorders that were presented in Table 3 [34].

Discussion

This scoping review was regarding the mental health status of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results indicated that COVID-19 and its restrictions impacted psychological behaviors (i.e. anxiety, sadness, psychological well-being), changes in lifestyles (i.e. sleep, eating, relations, exercise, screen time, social media, routines, and coping strategies), and some special symptoms (i.e. hyperactivity, attention deficit, and oppositional symptoms) in children and adolescents with ADHD [7, 9, 12, 15, 16]. These results are consistent with Bobo et al. (2022) [8]. Despite this, the longitudinal studies did not show a stable pattern of behaviors and mental status in adolescents with ADHD during this time [5, 13]. On the other side, some studies reported the deterioration of behaviors and their related factors in children and adolescents with ADHD [5, 12-15]. Individuals with ADHD have poor adaptability to stressful situations, such as COVID-19. Quarantine and staying at home caused a decrease in routines. In addition, they are susceptible to having poor coping strategies. Changes in routines and poor coping strategies may influence their behaviors; therefore, they need more time to adjust to the changes in situations [7].

This review also highlighted the presence of several mental health changes such as disruptive behavior, anxiety disorder, irritability, sleep problems, and disruptive behavior in children and adolescents with ASD during COVID-19 [18]. These results are consistent with Narzisi et al. (2013) study in which ASD individuals were more vulnerable to routine disruptions [48], so parents had difficulty managing their children’s activities. The difficulty of managing children’s routines will cause greater stress for parents. Studies showed that routine disruption [24] and parental stress [23] were the predictors of mood change and behavioral problems. Another reason for the increasing autistic maladaptive behavior of these children is an unexpected lack of access to healthcare during the COVID-19 [18].

The certain behaviors observed in individuals with ASD, such as sensory issues, stimming behaviors, and repetitive behavior were worsened [17, 21, 22]. The presence of these behaviors can be a compensatory mechanism against internal or external difficulty, such as anxiety [17, 21, 24]. Younger age was a predictor of appearing positive mood changes and reduction of behavioral problems [22]. It may be because younger children naturally are less aware of the condition than older children. Besides that, establishing new routines is more acceptable and tolerable in younger children [22]. In addition, children with ASD get information about COVID-19 through news, social media, and hearing from family members. Achieving the correct information and understanding the news can be difficult for them, thereby causing some psychiatric problems such as anxiety [26]. Other reasons for increasing psychiatric symptoms in children with ASD included low income, parental depression, and anxiety [26]. This finding is consistent with evidence in other populations during COVID-19 [26, 49]. Breaux et al. (2021) reported that low income was related to increased inattention, and high income is related to increased oppositional symptoms in adolescents with ADHD [5]. Families with low income may be more vulnerable to being jobless, so the level of parental depression and sense of worry may increase the child’s psychiatric symptoms [20]. Furthermore, low family income is associated with difficulty in accessing healthcare services.

In the field of other neurodevelopmental disabilities, one study has shown a higher prevalence of emotional and behavioral problems (64.1% and 77.1%) in ASD and (51.5% and 61.2%) in ID groups during the COVID-19 [33]. Previous studies reported fewer emotional and behavioral problems (about 50%) in children with ASD and ID [50]. According to the Guller et al. (2021) study, the disruption of sleep routines is a key predictor of emotional and behavioral problems [33]. Poor quality sleep has negative effects on behavioral and emotional symptoms, especially in children with neurodevelopmental disorders [51]. In addition, school closures and social isolation disrupted children’s daily patterns, which reduced the quality of children’s sleep [33, 34, 39], a poorer diet [39], reduced physical activity, and increasing the use of social media, TV and gaming [39]. Another reason for the decrease in their mental health status could be the homeschooling [42] and inaccessibility to facilities and specialist teams such as the rehabilitation team [44].

Limitations

In this review, we found some shortcomings in the existing studies; Most of the studies focused on ASD and ADHD. We suggested that more specific studies on unique groups of developmental disabilities are essential; Most studies were cross-sectional; Therefore, future longitudinal research is needed to increase knowledge and examine the long-term effects of the epidemic on the mental health of children and adolescents with developmental disabilities. In addition, a systematic review is useful to obtain detailed information in this field.

Conclusion

The present scoping review showed that most children and adolescents with developmental disabilities experienced deterioration in their mental health status due to restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Facilitation of access to rehabilitation and educational services, and parental training is essential to manage these stressful situations. In addition, the role of financial issues in managing mental health problems and increasing the well-being of children and adolescents and their caregivers is crucial. Governments and policymakers should think about long-term post-COVID-19 psychological consequences and provide proper intervention support for vulnerable groups and their families.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.314).

Funding

This article was financially supported by the University of Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Grant No. 2871).

Authors' contributions

Idea of the article: Farin Soleimani; Conceptualization and writing–original draft: Fatemeh Hassanati, Peymaneh Shirinbayan and Somayeh Amiri-Arimi; Record screening and extraction: Zahra Ghorbanpour, Zahra Nobakht and Farin Soleimani; Methodology: Mohammad Saatchi; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article are grateful for the financial support of the University of social welfare and rehabilitation sciences for this project.

Refrences

- Doody O, Keenan PM. The reported effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic on PeoPle with intellectual disability and their carers: A scoPing review. Annals of Medicine. 2021; 53(1):786-804. [DOI:10.1080/07853890.2021.1922743]

- Houtrow A, Harris D, Molinero A, Levin-Decanini T, Robichaud C. Children with disabilities in the United States and the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine. 2020; 13(3):415-24. [DOI:10.3233/PRM-200769]

- Klasen H, Crombag AC. What works where? A systematic review of child and adolescent mental health interventions for low and middle income countries. Social Psychiatry And Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013; 48(4):595-611. [DOI:10.1007/s00127-012-0566-x]

- Ma L, Mazidi M, Li K, Li Y, Chen S, Kirwan R, et al. Prevalence of mental health Problems among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021; 293:78-89. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.021]

- Breaux R, Dvorsky MR, Marsh NP, Green CD, Cash AR, Shroff DM, et al. Prospective impact of COVID-19 on mental health functioning in adolescents with and without ADHD: Protective role of emotion regulation abilities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2021; 62(9):1132-9. [DOI:10.1111/jcPP.13382]

- Shorey S, Lau LST, Tan JX, Ng ED, Aishworiya R. Families with children with neurodeveloPmental disorders during COVID-19: a scoping review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2021; 46(5):514-25. [DOI:10.1093/jPePsy/jsab029]

- Korpa T, Pappa T, Chouliaras G, Sfinari A, Eleftheriades A, Katsounas M, et al. Daily behaviors, worries and emotions in children and adolescents with ADHD and learning difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic. Children. 2021; 8(11):995. [DOI:10.3390/children8110995]

- Bobo E, Fongaro E, Lin L, Gétin C, Gamon L, Picot MC, et al. Mental health of children with attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder and their parents during the COVID-19 lockdown: A national cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2022; 13:902245. [DOI:10.3389/fPsyt.2022.902245]

- Sciberras E, Patel P, Stokes MA, Coghill D, Middeldorp CM, Bellgrove MA, et al. Physical health, media use, and mental health in children and adolescents with ADHD during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2022; 26(4):549-62. [DOI:10.1177/1087054720978549]

- Panchal U, Salazar de Pablo G, Franco M, Moreno C, Parellada M, Arango C, et al. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on child and adolescent mental health: Systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2021; 32:1151-77. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-021-01856-w]

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018; 169(7):467-73. [DOI:10.7326/M18-0850]

- Zhang J, Shuai L, Yu H, Wang Z, Qiu M, Lu L, et al. Acute stress, behavioural symptoms and mood states among school-age children with attention-deficit/hyperactive disorder during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020; 51:102077. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajP.2020.102077]

- Dvorsky MR, Breaux R, Cusick CN, Fredrick JW, Green C, Steinberg A, et al. Coping with COVID-19: Longitudinal impact of the pandemic on adjustment and links with coping for adolescents with and without ADHD. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology. 2022; 50(5):605-19. [DOI:10.1007/s10802-021-00857-2]

- Navarro-Soria I, Real-Fernández M, de Mier RJR, Costa-López B, Sánchez M, Lavigne R. Consequences of confinement due to covid-19 in Spain on anxiety, sleep and executive functioning of children and adolescents with ADHD. Sustainability. 2021; 13(5):1-17. [DOI:10.3390/su13052487]

- Swansburg R, Hai T, Macmaster FP, Lemay JF. Impact of COVID-19 on lifestyle habits and mental health symPtoms in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Canada. Paediatrics & Child Health. 2021; 26(5):e199-207. [DOI:10.1093/Pch/Pxab030]

- Fredrick JW, Nagle K, Langberg JM, Dvorsky MR, Breaux R, Becker SP. Rumination as a mechanism of the longitudinal association between COVID-19-related stress and internalizing symptoms in adolescents. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2022; 55:531–40. [DOI:10.1007/s10578-022-01435-3]

- Amorim R, Catarino S, Miragaia P, Ferreras C, Viana V, Guardiano M. The impact of COVID-19 on children with autism sPectrum disorder. Revista de Neurologia. 2020; 71(8):285-91. [DOI:10.33588/rn.7108.2020381] [PMID]

- Colizzi M, Sironi E, Antonini F, CIceri ML, Bovo C, Zoccante L. Psychosocial and behavioral impact of COVID-19 in autism spectrum disorder: An online parent survey. Brain Sciences. 2020; 10(6):341. [DOI:10.3390/brainsCI10060341]

- Khan YS, Khan AW, El Tahir M, Hammoudeh S, Al Shamlawi M, Alabdulla M. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic social restrictions on individuals with autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers in the stateof Qatar: A cross-sectional study. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2021; 119:104090. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104090]

- Manning J, Billian J, Matson J, Allen C, Soares N. Perceptions of families of individuals with autism spectrum disorder during the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2021; 51(8):2920-8. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-020-04760-5]

- Martínez-González AE, Moreno-Amador B, Piqueras JA. Differences in emotional state and autistic symptoms before and during confinement due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2021; 116:104038. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2021.104038]

- Fumagalli L, Nicoli M, Villa L, Riva V, Vicovaro M, Casartelli L. The (a)typical burden of COVID-19 pandemic scenario in autism spectrum disorder. Scientific Reports. 2021; 11(1):22655. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-021-01907-x]

- Bharat R, Uzaina, Niranjan S, Yadav T, Newman S, Marriott J, et al. Autism spectrum disorder in the COVID 19 era: New challenges - new solutions. Indian Pediatrics. 2021; 58(9):890-1. [DOI:10.1007/s13312-021-2314-3]

- Genova HM, Arora A, Botticello AL. Effects of school closures resulting from COVID-19 in autistic and neurotypical children. Frontiers in Education. 2021; 6:761485. [DOI:10.3389/feduc.2021.761485]

- Lugo-Marín J, Gisbert-Gustemps L, Setien-Ramos I, Español-Martín G, Ibañez-Jimenez P, Forner-Puntonet M, et al. COVID-19 pandemic effects in people with autism spectrum disorder and their caregivers: Evaluation of social distancing and lockdown impact on mental health and general status. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2021; 83:101757. [DOI:10.1016/j.rASD.2021.101757]

- Vasa RA, Singh V, Holingue C, Kalb LG, Jang Y, Keefer A. Psychiatric problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research. 2021; 14(10):2113-9. [DOI:10.1002/aur.2574]

- Polónyiová K, Belica I, Celušáková H, Janšáková K, Kopčíková M, Szapuová Ž, et al. Comparing the impact of the first and second wave of COVID-19 lockdown on slovak families with typically developing children and children with autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2022; 26(5):1046-55. [DOI:10.1177/13623613211051480]

- Hannawi AP, Knight C, Grelotti DJ, Trauner DA. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic-associated social changes on boys with moderate to severe autism. Advances in Neurodevelopmental Disorders. 2022; 6(2):206-10. [DOI:10.1007/s41252-022-00257-7]

- Bolbocean C, Rhidenour KB, Mccormack M, Suter B, Holder JL. COVID-19 induced environments, health-related quality of life outcomes and problematic behaviors: Evidence from children with syndromic autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2022; 53:1000–16. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-022-05619-7]

- Scarselli V, Martucci M, Prono F, Giovannone F, Sogos C. Sleep behavior of children with autism spectrum disorder during the Covid-19 pandemic: A parent survey. La Clinica Terapeutica. 2022; 173(1):88-90. [PMID]

- Conti E, Sgandurra G, De Nicola G, Biagioni T, Boldrini S, Bonaventura E, et al. Behavioural and emotional changes during COVID-19 lockdown in an italian paediatric population with neurologic and psychiatric disorders. Brain Sciences. 2020; 10(12):918. [DOI:10.3390/brainsCI10120918]

- Nonweiler J, Rattray F, Baulcomb J, Happé F, Absoud M. Prevalence and associated factors of emotional and behavioural difficulties during COVID-19 pandemic in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Children. 2020; 7(9):128. [DOI:10.3390/children7090128]

- Guller B, Yaylaci F, Eyuboglu D. Those in the shadow of the Pandemic: imPacts of the COVID-19 outbreak on the mental health of children with neurodevelopmental disorders and their Parents. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 2021; 68(6):943-55. [DOI:10.1080/20473869.2021.1930827]

- Dondi A, Fetta A, Lenzi J, Morigi F, Candela E, Rocca A, et al. SleeP disorders reveal distress among children and adolescents during the Covid-19 first wave: results of a large web-based Italian survey. Italian Journal of Pediatrics. 2021; 47(1):130. [DOI:10.1186/s13052-021-01083-8]

- Ehrler M, Werninger I, Schnider B, Eichelberger DA, Naef N, Disselhoff V, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with and without risk for neurodevelopmental impairments. Acta Paediatrica. 2021; 110(4):1281-8. [DOI:10.1111/aPa.15775]

- Gilsbach S, Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Konrad K. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents with and without mental disorders. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021; 9:679041. [DOI:10.3389/fPubh.2021.679041]

- Jordan TL, Bartholomay KL, Lee CH, Miller JG, Lightbody AA, Reiss AL. COVID-19 pandemic: Mental health in girls with and without fragile X syndrome. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2022; 47(1):25-36. [DOI:10.1093/jPePsy/jsab106]

- Lai B, Wen HC, Sinha T, Davis D, Swanson-Kimani E, Wozow C, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on the lifestyles of adolescents with cerebral palsy in the southeast United States. Disability and Health Journal. 2022; 15(2):101263. [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101263]

- Masi A, Mendoza Diaz A, Tully L, Azim SI, Woolfenden S, Efron D, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on the well-being of children with neurodevelopmental disabilities and their Parents. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2021; 57(5):631-6. [DOI:10.1111/jPc.15285]

- Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, Birken CS, Charach A, Monga S, et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: imPact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2022; 31(4):671-84. [DOI:10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3]

- Mete Yesil A, Sencan B, Omercioglu E, Ozmert EN. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children with special needs: A descriptive study. Clinical Pediatrics. 2022; 61(2):141-9. [DOI:10.1177/00099228211050223]

- Rizzo R, Karlov L, Maugeri N, di Silvestre S, Eapen V. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family wellbeing in the context of neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2021; 17:3007-14. [DOI:10.2147/NDT.S327092]

- Suzuki K, Hiratani M. The association of mental health problems with preventive behavior and caregivers’ anxiety about COVID-19 in children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021; 12:713834. [DOI:10.3389/fPsyt.2021.713834]

- Theis N, Campbell N, De Leeuw J, Owen M, Schenke KC. The effects of COVID-19 restrictions on physical activity and mental health of children and young adults with physical and/or intellectual disabilities. Disability and Health Journal. 2021; 14(3):101064. [DOI:10.1016/j.dhjo.2021.101064]

- Yang Y, Xiao Y, Liu Y, Li Q, Shan C, Chang S, et al. Mental health and psychological impact on students with or without hearing loss during the recurrence of the COVID-19 pandemic in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(4):1421. [DOI:10.3390/ijerPh18041421]

- Nisha SI, Bakul F. Parents/primary caregivers’ perspectives on the well-being, and home-based learning of children with neurodevelopmental disorders during COVID-19 in Bangladesh. International Journal of DeveloPmental Disabilities. 2022; 70(4):594-603. [DOI:10.1080/20473869.2022.2121140]

- Narzisi A, Muratori F, Calderoni S, Fabbro F, Urgesi C. Neuropsychological profile in high functioning autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2013; 43(8):1895-909. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-012-1736-0]

- Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, Sampson L, Vivier PM, Galea S. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2020; 3(9):e2019686. [DOI:10.1001/jamanetworkoPen.2020.19686]

- Dekker MC, Koot HM, Ende JVD, Verhulst FC. Emotional and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with and without intellectual disability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002; 43(8):1087-98. [DOI:10.1111/1469-7610.00235]

- Chorney DB, Detweiler MF, Morris TL, Kuhn BR. The interplay of sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression in children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008; 33(4):339-48. [DOI:10.1093/jPePsy/jsm105]

Type of Study: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Pediatric Neurology

Received: 9/01/2024 | Accepted: 3/09/2024 | Published: 1/11/2024

Received: 9/01/2024 | Accepted: 3/09/2024 | Published: 1/11/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |