Volume 25, Issue 4 (Winter 2025)

jrehab 2025, 25(4): 848-863 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Soleimanieh-Naeini T, Sadeghikhah H, Sadati Firoozabadi S S, Movallali G. The Effects of the Faranak Parent-Child Mother Goose Program on the Psychological Well-being of Mothers With Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children. jrehab 2025; 25 (4) :848-863

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3428-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3428-en.html

Tahereh Soleimanieh-Naeini1

, Hakimeh Sadeghikhah2

, Hakimeh Sadeghikhah2

, Somayeh Sadat Sadati Firoozabadi *3

, Somayeh Sadat Sadati Firoozabadi *3

, Guita Movallali4

, Guita Movallali4

, Hakimeh Sadeghikhah2

, Hakimeh Sadeghikhah2

, Somayeh Sadat Sadati Firoozabadi *3

, Somayeh Sadat Sadati Firoozabadi *3

, Guita Movallali4

, Guita Movallali4

1- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. ,somayehsadati@shirazu.ac.ir

4- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran.

3- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. ,

4- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1919 kb]

(663 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5142 Views)

References

Full-Text: (518 Views)

Introduction

Hearing loss (HL) is one of the global public health challenges. This disorder affects about 1.6 billion people (20.3% of the world’s population). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by 2050, nearly 2.5 billion people, including 34 million children, will be affected by HL. The effects of HL in children comprised severe impairment in acquiring speech and language skills [1]. These children struggle to use language appropriately and establish relationships with their hearing peers, limiting their social interaction opportunities [2، 3]. Children who are unable to provide accurate responses due to hearing difficulties may become sensitive and prone to aggression over time, often developing an increased dependence on their close family members [4].

On the other hand, facing the diagnosis of a child’s HL has an emotional impact on parents as well [5]. Parents who are concerned about establishing relationships, parenting, and educating their children experience negative emotions such as shock, denial, helplessness, grief, anger, and anxiety [6، 7]. Consequently, the parent and child’s psychological wellbeing (PWB) is affected [8]. The PWB of parents can only be restored if they can establish effective and efficient interaction with the community, alleviate their negative emotions, be satisfied with their lives, meet their psychological needs, pursue intrinsic goals, maintain desirable social relationships with the community, and thrive [9، 10].

It is recommended that newly becoming mothers utilize parenting skill acquisition programs, as these initiatives have been repeatedly reported to positively impact the PWB of parents in general [11-13]. Implementing such programs would be of great value for ensuring the PWB of parents and DHH children. An important example of such a program is the parent-child mother-goose program (P-CMGP) [14]. This group-based, enjoyable, and verbal program requires no specialized training for implementation. P-CMGP aims to enhance children’s language and speech abilities, fostering secure attachment and bonding between parent and child [15]. The P-CMGP, generally used by parents and their children, is currently being implemented in some centers in many countries, including Canada, Australia, and the United States, as part of supportive interventions for children with DHH and their families [15، 16]. Several studies have indicated that implementing this program increases parents’ sense of competency, self-efficacy, emotion regulation, self-confidence, and satisfaction with parenting. Furthermore, the program facilitates bringing parents and families together, creating opportunities for fostering social connection and enjoyable interactions, and positively impacting the social development of parents [17-22].

Faranak P-CMGP, the Persian-language adaptation of P-CMGP is used to improve the relationship between hearing mothers and their deaf & hard of hearing children [23] and the speech and language skills of their 0-3 years old children [24]. The impact of the P-CMGP and Faranak P-CMGP on fostering attachment and the relationship between mother and children with HL have been reported in several studies. However, to our knowledge, no research has been published yet to evaluate the effect of the P-CMGP or Faranak P-CMGP on the PWB of the mothers of children with HL. The PWB of mothers plays a vital role in the overall development and evolution of children, particularly those with special needs. This study assessed the effects of Faranak P-CMGP on the PWB in mothers of children who are deaf and hard of hearing under 6 years old.

Materials and Methods

In this quasi-experimental study with pre-test, post-test and follow-up design, subjects were recruited from two family and DHH child centers in Borazjan and Ganaveh cities of Bushehr Province, Iran. Mothers of DHH children were aware of the goals of this study and informed written consent was obtained from all participants. They were selected through convenience sampling and divided randomly into two groups; an intervention group and a control group.

Study Participants

Overall, 53 mothers of children who are DHH under the age of 6 (27 mother-child in the intervention group and 26 in the control group) were included in this study. Their children did not have any other disabilities except hearing impairment. Participants had not attended similar intervention classes previously. Participants who missed more than three training sessions were excluded.

The sample size was calculated based on 80% power, 5% alpha error, information from similar studies, and a dropout likelihood in each group. Therefore, 27 mothers in the intervention group and 26 in the control group were allocated.

Measurement

The Persian version of the Ryff PWB Scale was used to measure 6 aspects of wellbeing in the two intervention and control groups before, one month, and four months after the intervention.

Psychological Wellbeing Scale

In this study, the Persian version of the 18-item Ryff PWB scale (1989) assesses 6 dimensions of wellbeing: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. Each dimension consists of three questions using a 6-point scale, with responses ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The total score of these 6 dimensions reveals the range of PWB scores from 18 to 108 [25]. Sefidi and Farzad’s psychometric study of the Persian version (2020) calculated the internal consistency of the questions using the Cronbach α, resulting in a score ranging from 0.65 to 0.75. In the factor analysis, 4 factors explained 37.50% of the total variance [26]. Moreover, Sadati Firoozabadi and Moltafet (2017) calculated the reliability of the test-retest of this scale at 36.39% variance for 3 factors [27]. The scale’s reliability was calculated using the Cronbach α in the present study. The Cronbach α values for PWB and 6 dimensions were as follows: PWB, 0.802; self-acceptance, 0.819; positive relations with others, 0.781; autonomy, 0.790; environmental mastery, 0.802; purpose in life, 0.779; and personal growth, 0.882. It is worthwhile to mention that mothers of both groups completed all questionnaires.

Study Intervention

Faranak Parent-Child Mother Goose Program (P-CMGP)

Faranak P-CMGP is derived from P-CMGP. It promotes parent-child interaction and bonding through singing songs, rhymes, and stories. The Franak program used the content of songs, rhymes, and lullabies from Iranian culture and selections from the Faranak program book series [28]. The program began with a warm welcome, encouraging mothers to sit on mats in a circle and hold their children on their laps. The program is based on the mother’s rhythmic singing with the child through movement as they look at each other (face-to-face), with eye contact, touch, and cuddling. Before the program starts, toys are given to the children to play, but no toys are used during the performance of the program. Two to three new rhymes and lullaby songs were performed in each session, gradually using longer pieces. Previous songs were also repeated for the mother and child as a reminder. Two teachers were involved in implementing the program: The primary teacher was responsible for singing rhythmic, simple, and child-friendly songs, rhymes, and lullabies for mothers and children, and the second teacher collaborated in singing and facilitated the sessions.

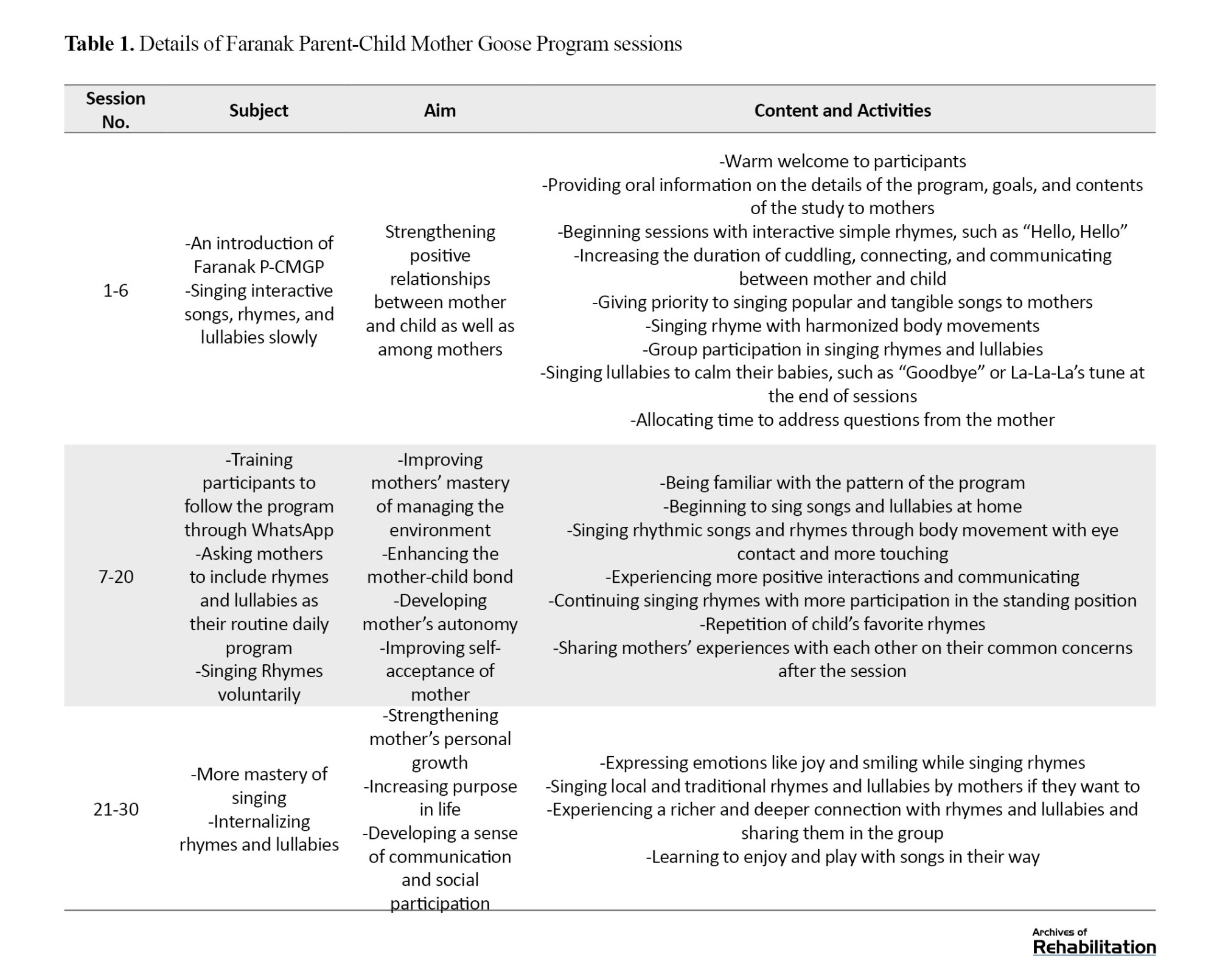

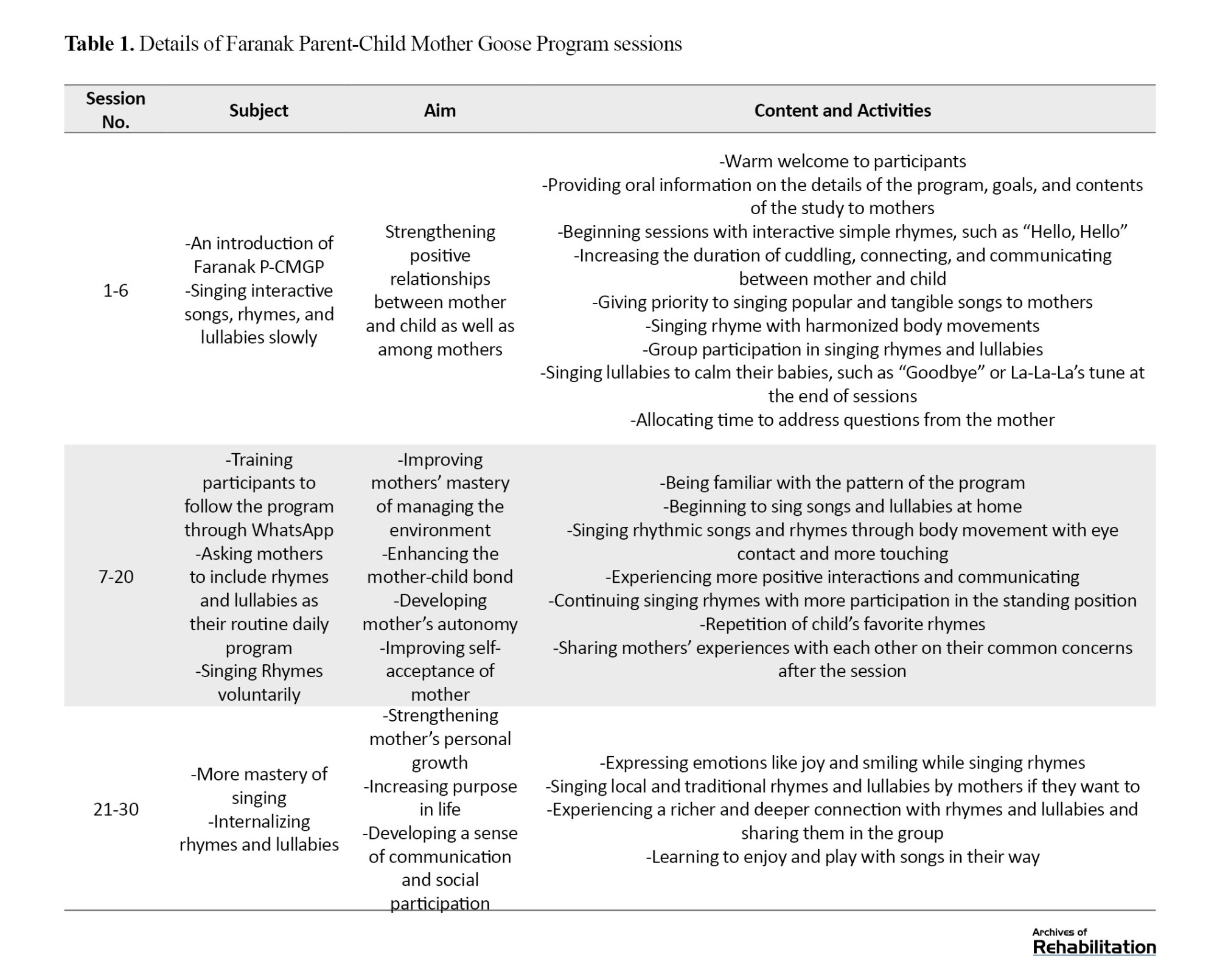

Mothers of children in the intervention group participated in 30 weekly sessions (one-hour duration) of Faranak P-CMGP. Initially, the program was held by the group participation of mothers and their children at two centers and online with the primary teacher for 6 sessions. Subsequently, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the remaining sessions continued online via WhatsApp in 5 small mother-child groups. Because of the children’s interest in technology, the online sessions attracted their attention and their families. Meanwhile, the control group received conventional programs. The training program content is presented in Table 1.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with an alpha error of 0.05, using SPSS software, version 21.

Results

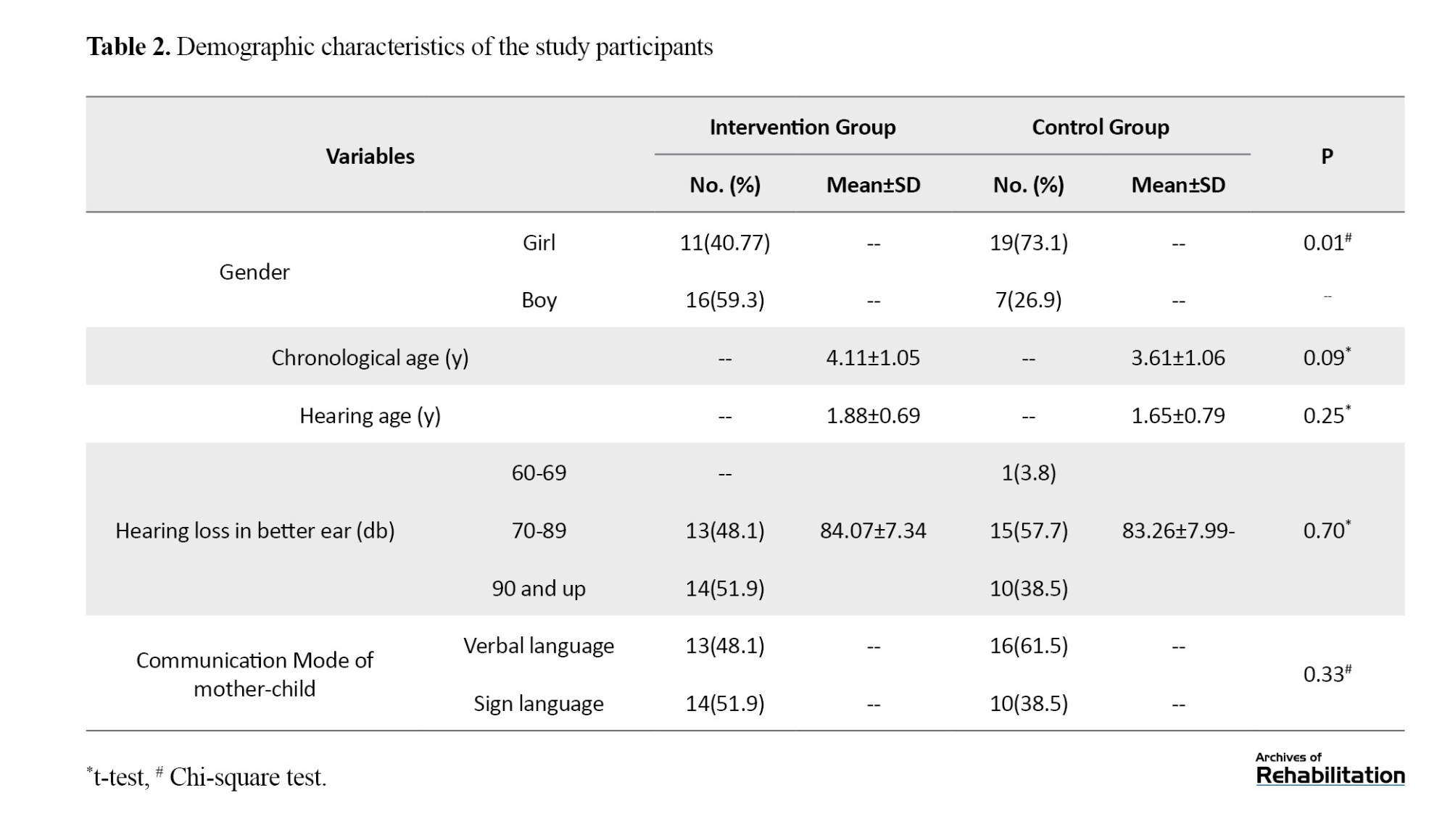

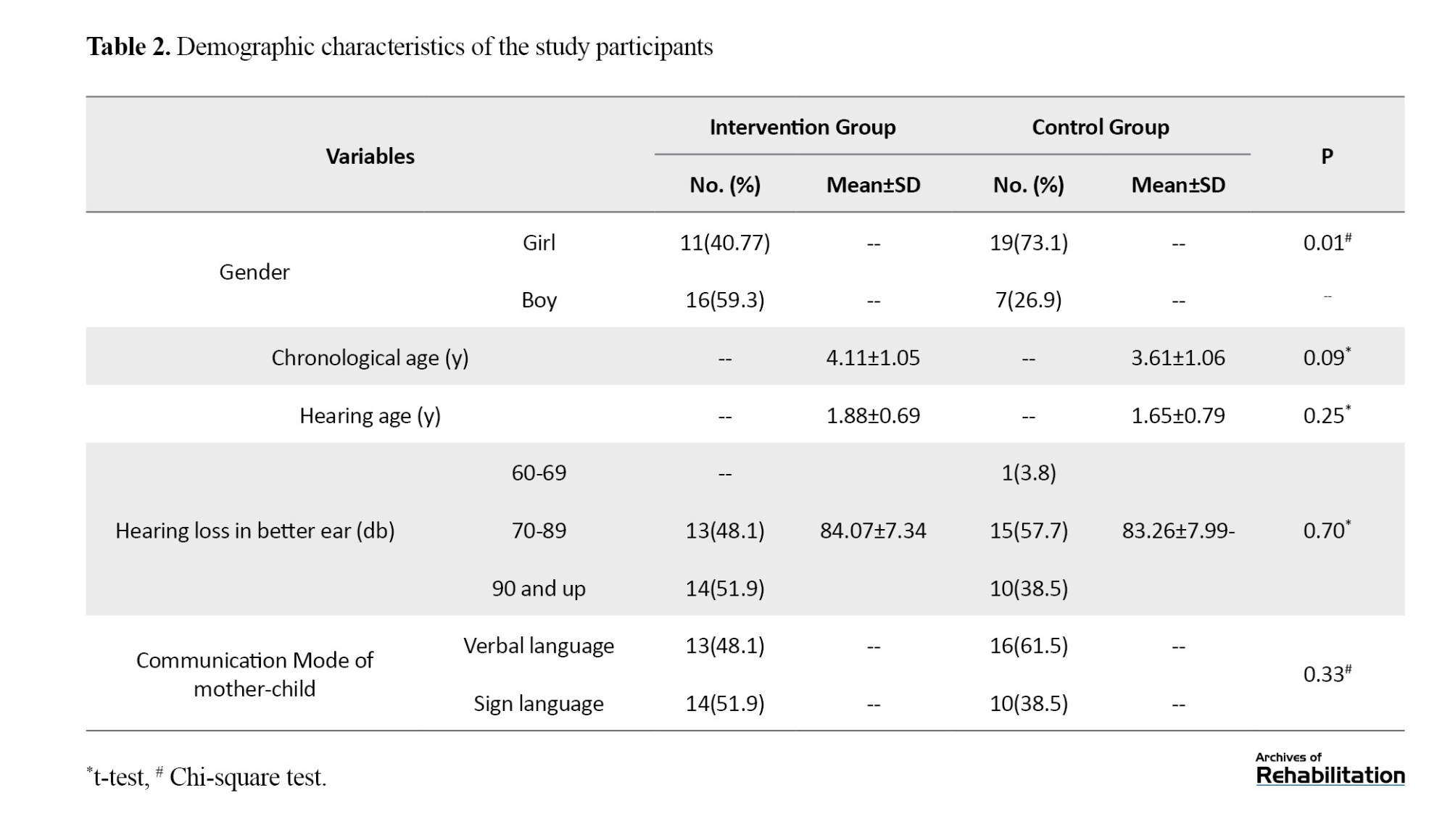

A total of 53 mothers with DHH children participated in this study. The mothers’ mean age and standard deviation were 33.55±3.72 years. In terms of the educational level of participants, 41 mothers had a diploma (77%) and 12 bachelor’s degrees (23%). There was no significant difference between the age and education levels of the mothers in the two groups (P>0.05). The characteristics of the children are presented in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, almost all children had severe to profound HL. There was no statistically significant difference between the chronological age and hearing age of the children, as well as the communication mode between mother and child (verbal/sign language) (P>0.05). There was a statistically significant difference in the gender type of children in the two intervention and control groups (P=0.01). There were more boys than girls in the intervention group and vice versa in the control group.

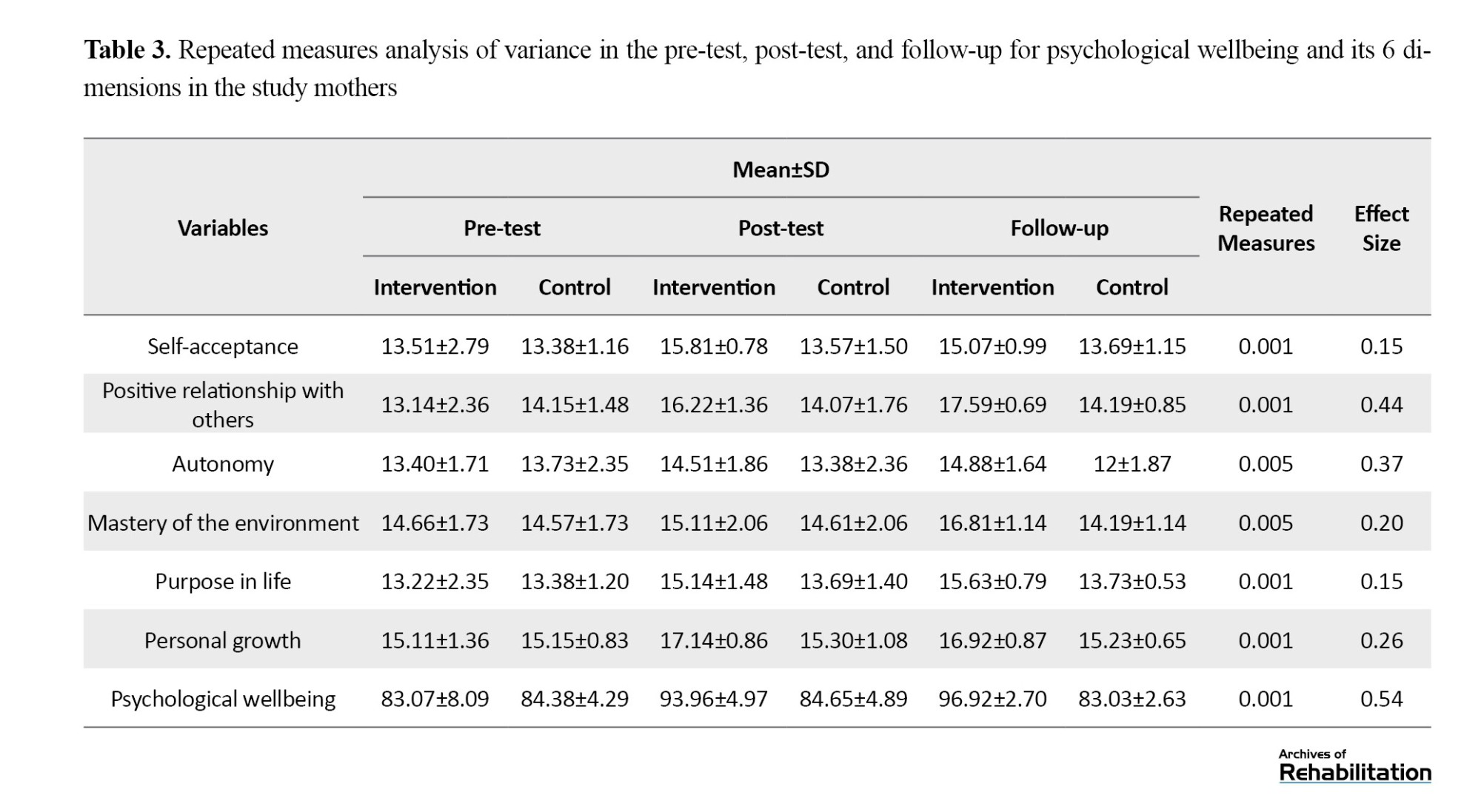

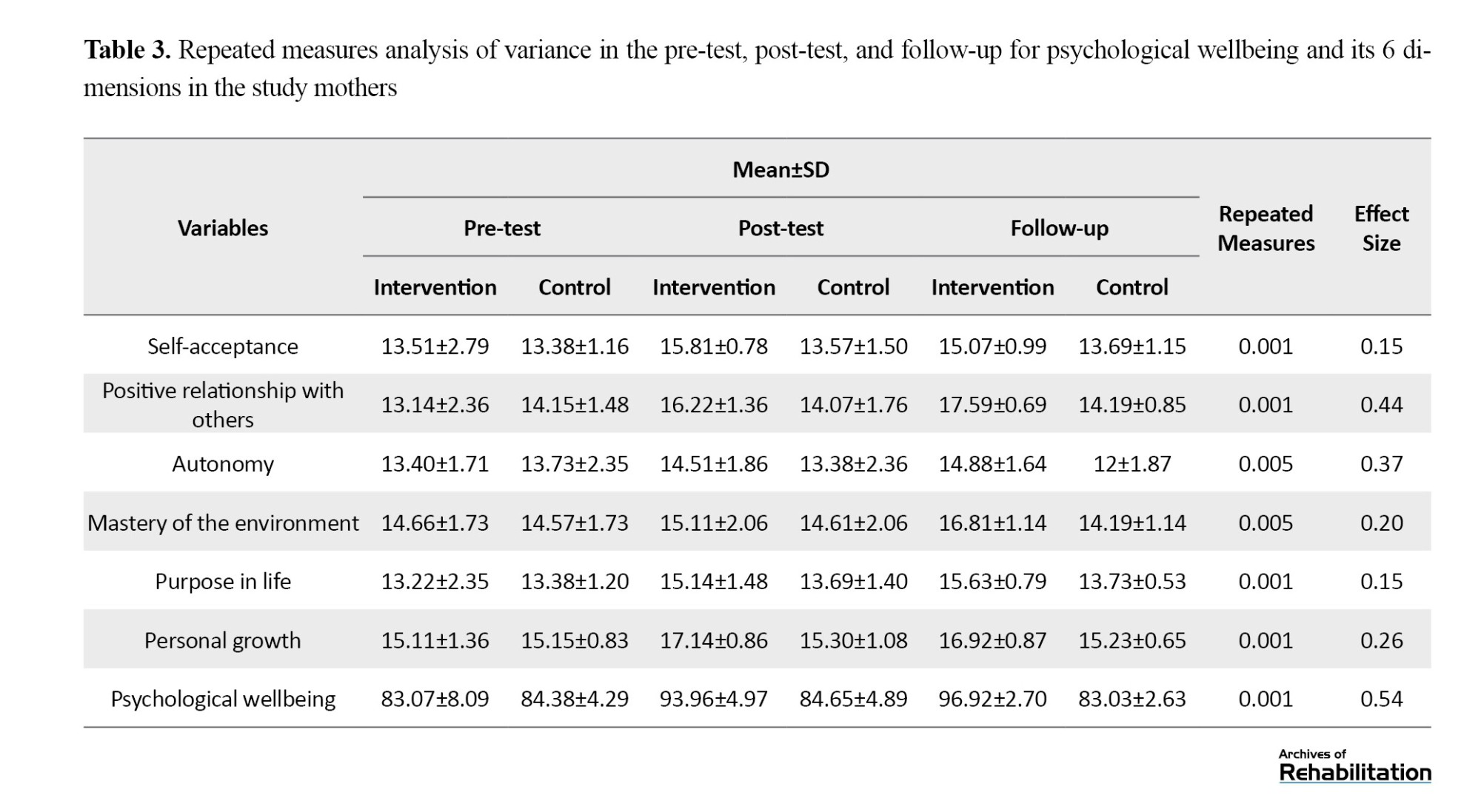

All variables were normally distributed. Before repeated measures ANOVA, the sphericity of changes within and between subjects was confirmed using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction. Table 3 shows the results of repeated measures ANOVA for comparing the effect size and mean scores of PWB and the six dimensions in mothers of the two groups at three time of measurements: pre-test, post-test, and follow-up.

Statistically significant differences were found in the mean score of PWB between the mothers of the two groups: an intervention and a control group (P<0.001).

The repeated measures ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of PWB of mothers of the two groups in three time points of measurements (P<0.001). Pairwise comparisons of this difference indicated that: 1. A statistically significant difference was found in mothers’ mean scores of PWB between the two intervention and control groups before and after the intervention (P<0.001). 2. There was no statistically significant difference in mothers’ mean scores of PWB between the intervention and control groups one month and four months after the intervention and during follow-up (P=0.75). Furthermore, mothers in the intervention group exhibited better performance in the 6 dimensions of PWB: self-acceptance, positive relationships with others, autonomy, mastery of the environment, purpose in life, and personal growth (P<0.001 in all instances) in post-test and follow-up. Based on the Eta squared coefficient, 54% of the changes between the scores of mothers in the two groups are attributed to the intervention (Table 3).

Discussion

Thirty training sessions of P-CMGP led to a significant improvement in the PWB of mothers of DHH children as well as in 6 wellbeing dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth in post-test and follow-up.

Utilizing parenting skill acquisition programs is essential for PWB of mothers of children with HL, as one of the most important dimensions is establishing a strong mother-child relationship. The present study demonstrated that the Faranak Program has a significant effect on the PWB of mothers and their 6 dimensions, and its effectiveness was statistically significant after at least 4 months of follow-up. The Faranak Program, a group-based, parent-centered, and joyful program, facilitated a stronger mother-child relationships and improved the connections among mothers compared to other aspects of wellbeing. This result could be due to the following reasons: One possible reason is that this research was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought about high levels of stress, isolation, and reduced social connections. Another possible reason could be the reduction of feelings of loneliness that mothers might experience when dealing with DHH children by meeting time of mothers who have overcome similar challenges. They also realized that other mothers confronted similar challenges, allowing them to consult with one another.

The results of this study on the effect of the Faranak program on the improved relationship between mother and child, as well as among the mothers, were in accordance with other studies, such as Carroll [22], Weis [21], Terrett, White, and Terrett [19], and Koohi et al. [23]. In all mentioned studies, songs, rhymes and lullabies have been used as tools to help parents in building stronger relationship with children who have HL. For example, the results of the study by Koohi et al. revealed an effect size of 0.64 after the implementation of the Faranak program on the relationship between mothers and children with HL. This effect size was higher than the one obtained in the present study (0.44). A possible reason for the greater effect observed in the study by Koohi et al. may be attributed to the in-person format of the Faranak program rather than online.

Many studies have been conducted to improve the PWB in mothers of children with HL using various intervention strategies. For instance, Foladi et al. investigated the effect of “group narrative therapy” on PWB in mothers of children with hearing impairment [29]. They demonstrated an effect size of 0.66 following the implementation of group narrative therapy on PWB in mothers, which was higher than the effect size obtained in the present study (0.54). However, due to the differences in time and location, as well as the variations in the implementation of the research between these two studies (this study and the study conducted by Foladi et al.), it cannot be certainly stated that the group narrative therapy approach was more effective than the Faranak program. However, further research must be conducted to compare the effect size on mothers of children with HL.

In this study, the Faranak program enhanced the mother-child relationship with an effect size of 0.44. However, Abbaszadeh et al., who applied the “positive parenting program” as an intervention strategy to improve the relationship, reported no statistically significant effect [30]. It seems that several factors have influenced their research outcomes, consisting of the differences in tools, the inadequacy of intervention content, the limited focus on coping strategies for mental health issues, and the acceptance of hearing impairment by mothers. Abbaszadeh’s research was conducted in Tehran, Iran, under specific time and social conditions, and parents could not access online methods, which led to the discontinuity of the training sessions. The present study was performed in smaller cities where parents were already familiar with the center and instructors and easy access to online methods, leading to continuity of training sessions. However, although both studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, the research conditions were entirely different.

There are some limitations in this study. This research was implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it suffered from social isolation, which may have a greater impact on outcome measures compared with post-COVID-19 pandemic conditions. Furthermore, as the sessions were held online (audio and video), the effect size of the face-to-face program may differ from what was estimated through an online program. Since the study was conducted in two small cities in Iran, the results cannot be generalized to all Iranian mothers and, of course, mothers in the world.

Conclusion

This research demonstrated a positive statistically significant effect of the Faranak P-CMGP on the PWB in mothers of DHH children. The interactions created during this program provided a platform for mothers to increase their knowledge about building relationships with DHH children through songs, rhymes, and lullabies. The Faranak program effectively promoted personal growth, autonomy, and PWB for mothers while also creating an opportunity for social connections among the mothers. The present study also indicated that strengthening the parent-child relationship, especially for mothers with DHH children, can be easily achieved by implementing the Faranak program. However, further research with a larger sample size seems necessary. It is recommended that educators of children with HL and early intervention specialists benefit from this program alongside other educational and rehabilitation programs for children with HL. Additionally, conducting online group programs can be a suitable alternative for mothers who cannot attend face-to-face sessions for any reason, allowing them to benefit from the Faranak program.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University, Iran (Code: SEP.14023.48.4840). Written informed consent was obtained the mothers of all children.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master’s thesis of the second author at the Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Somayeh Sadat Sadati Firoozabadi, Guita Movallali, and Hakimeh Sadeghikhah; Implementing P-CMGP, data collection, and data analysis: Tahereh Soleimanieh-Naeini and Hakimeh Sadeghikhah; Writing, review & editing: Somayeh Sadat Sadati Firoozabadi, Tahereh Soleimanieh-Naeini, and Guita Movallali; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the mothers and children who participated in this study and the authorities of the family centers for deaf and hard of hearing children in Borazjan and Ganaveh counties in Bushehr, Iran, for their cooperation in this research. The authors also would like to thank Dr. Nikta Hatamizadeh and Dr. Enayatollah Bakhshi for their invaluable guidance.

Hearing loss (HL) is one of the global public health challenges. This disorder affects about 1.6 billion people (20.3% of the world’s population). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by 2050, nearly 2.5 billion people, including 34 million children, will be affected by HL. The effects of HL in children comprised severe impairment in acquiring speech and language skills [1]. These children struggle to use language appropriately and establish relationships with their hearing peers, limiting their social interaction opportunities [2، 3]. Children who are unable to provide accurate responses due to hearing difficulties may become sensitive and prone to aggression over time, often developing an increased dependence on their close family members [4].

On the other hand, facing the diagnosis of a child’s HL has an emotional impact on parents as well [5]. Parents who are concerned about establishing relationships, parenting, and educating their children experience negative emotions such as shock, denial, helplessness, grief, anger, and anxiety [6، 7]. Consequently, the parent and child’s psychological wellbeing (PWB) is affected [8]. The PWB of parents can only be restored if they can establish effective and efficient interaction with the community, alleviate their negative emotions, be satisfied with their lives, meet their psychological needs, pursue intrinsic goals, maintain desirable social relationships with the community, and thrive [9، 10].

It is recommended that newly becoming mothers utilize parenting skill acquisition programs, as these initiatives have been repeatedly reported to positively impact the PWB of parents in general [11-13]. Implementing such programs would be of great value for ensuring the PWB of parents and DHH children. An important example of such a program is the parent-child mother-goose program (P-CMGP) [14]. This group-based, enjoyable, and verbal program requires no specialized training for implementation. P-CMGP aims to enhance children’s language and speech abilities, fostering secure attachment and bonding between parent and child [15]. The P-CMGP, generally used by parents and their children, is currently being implemented in some centers in many countries, including Canada, Australia, and the United States, as part of supportive interventions for children with DHH and their families [15، 16]. Several studies have indicated that implementing this program increases parents’ sense of competency, self-efficacy, emotion regulation, self-confidence, and satisfaction with parenting. Furthermore, the program facilitates bringing parents and families together, creating opportunities for fostering social connection and enjoyable interactions, and positively impacting the social development of parents [17-22].

Faranak P-CMGP, the Persian-language adaptation of P-CMGP is used to improve the relationship between hearing mothers and their deaf & hard of hearing children [23] and the speech and language skills of their 0-3 years old children [24]. The impact of the P-CMGP and Faranak P-CMGP on fostering attachment and the relationship between mother and children with HL have been reported in several studies. However, to our knowledge, no research has been published yet to evaluate the effect of the P-CMGP or Faranak P-CMGP on the PWB of the mothers of children with HL. The PWB of mothers plays a vital role in the overall development and evolution of children, particularly those with special needs. This study assessed the effects of Faranak P-CMGP on the PWB in mothers of children who are deaf and hard of hearing under 6 years old.

Materials and Methods

In this quasi-experimental study with pre-test, post-test and follow-up design, subjects were recruited from two family and DHH child centers in Borazjan and Ganaveh cities of Bushehr Province, Iran. Mothers of DHH children were aware of the goals of this study and informed written consent was obtained from all participants. They were selected through convenience sampling and divided randomly into two groups; an intervention group and a control group.

Study Participants

Overall, 53 mothers of children who are DHH under the age of 6 (27 mother-child in the intervention group and 26 in the control group) were included in this study. Their children did not have any other disabilities except hearing impairment. Participants had not attended similar intervention classes previously. Participants who missed more than three training sessions were excluded.

The sample size was calculated based on 80% power, 5% alpha error, information from similar studies, and a dropout likelihood in each group. Therefore, 27 mothers in the intervention group and 26 in the control group were allocated.

Measurement

The Persian version of the Ryff PWB Scale was used to measure 6 aspects of wellbeing in the two intervention and control groups before, one month, and four months after the intervention.

Psychological Wellbeing Scale

In this study, the Persian version of the 18-item Ryff PWB scale (1989) assesses 6 dimensions of wellbeing: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth. Each dimension consists of three questions using a 6-point scale, with responses ranging from 0 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The total score of these 6 dimensions reveals the range of PWB scores from 18 to 108 [25]. Sefidi and Farzad’s psychometric study of the Persian version (2020) calculated the internal consistency of the questions using the Cronbach α, resulting in a score ranging from 0.65 to 0.75. In the factor analysis, 4 factors explained 37.50% of the total variance [26]. Moreover, Sadati Firoozabadi and Moltafet (2017) calculated the reliability of the test-retest of this scale at 36.39% variance for 3 factors [27]. The scale’s reliability was calculated using the Cronbach α in the present study. The Cronbach α values for PWB and 6 dimensions were as follows: PWB, 0.802; self-acceptance, 0.819; positive relations with others, 0.781; autonomy, 0.790; environmental mastery, 0.802; purpose in life, 0.779; and personal growth, 0.882. It is worthwhile to mention that mothers of both groups completed all questionnaires.

Study Intervention

Faranak Parent-Child Mother Goose Program (P-CMGP)

Faranak P-CMGP is derived from P-CMGP. It promotes parent-child interaction and bonding through singing songs, rhymes, and stories. The Franak program used the content of songs, rhymes, and lullabies from Iranian culture and selections from the Faranak program book series [28]. The program began with a warm welcome, encouraging mothers to sit on mats in a circle and hold their children on their laps. The program is based on the mother’s rhythmic singing with the child through movement as they look at each other (face-to-face), with eye contact, touch, and cuddling. Before the program starts, toys are given to the children to play, but no toys are used during the performance of the program. Two to three new rhymes and lullaby songs were performed in each session, gradually using longer pieces. Previous songs were also repeated for the mother and child as a reminder. Two teachers were involved in implementing the program: The primary teacher was responsible for singing rhythmic, simple, and child-friendly songs, rhymes, and lullabies for mothers and children, and the second teacher collaborated in singing and facilitated the sessions.

Mothers of children in the intervention group participated in 30 weekly sessions (one-hour duration) of Faranak P-CMGP. Initially, the program was held by the group participation of mothers and their children at two centers and online with the primary teacher for 6 sessions. Subsequently, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the remaining sessions continued online via WhatsApp in 5 small mother-child groups. Because of the children’s interest in technology, the online sessions attracted their attention and their families. Meanwhile, the control group received conventional programs. The training program content is presented in Table 1.

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed by repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA), with an alpha error of 0.05, using SPSS software, version 21.

Results

A total of 53 mothers with DHH children participated in this study. The mothers’ mean age and standard deviation were 33.55±3.72 years. In terms of the educational level of participants, 41 mothers had a diploma (77%) and 12 bachelor’s degrees (23%). There was no significant difference between the age and education levels of the mothers in the two groups (P>0.05). The characteristics of the children are presented in Table 2.

As shown in Table 2, almost all children had severe to profound HL. There was no statistically significant difference between the chronological age and hearing age of the children, as well as the communication mode between mother and child (verbal/sign language) (P>0.05). There was a statistically significant difference in the gender type of children in the two intervention and control groups (P=0.01). There were more boys than girls in the intervention group and vice versa in the control group.

All variables were normally distributed. Before repeated measures ANOVA, the sphericity of changes within and between subjects was confirmed using the Greenhouse-Geisser correction. Table 3 shows the results of repeated measures ANOVA for comparing the effect size and mean scores of PWB and the six dimensions in mothers of the two groups at three time of measurements: pre-test, post-test, and follow-up.

Statistically significant differences were found in the mean score of PWB between the mothers of the two groups: an intervention and a control group (P<0.001).

The repeated measures ANOVA showed a statistically significant difference between the mean scores of PWB of mothers of the two groups in three time points of measurements (P<0.001). Pairwise comparisons of this difference indicated that: 1. A statistically significant difference was found in mothers’ mean scores of PWB between the two intervention and control groups before and after the intervention (P<0.001). 2. There was no statistically significant difference in mothers’ mean scores of PWB between the intervention and control groups one month and four months after the intervention and during follow-up (P=0.75). Furthermore, mothers in the intervention group exhibited better performance in the 6 dimensions of PWB: self-acceptance, positive relationships with others, autonomy, mastery of the environment, purpose in life, and personal growth (P<0.001 in all instances) in post-test and follow-up. Based on the Eta squared coefficient, 54% of the changes between the scores of mothers in the two groups are attributed to the intervention (Table 3).

Discussion

Thirty training sessions of P-CMGP led to a significant improvement in the PWB of mothers of DHH children as well as in 6 wellbeing dimensions: self-acceptance, positive relations with others, autonomy, environmental mastery, purpose in life, and personal growth in post-test and follow-up.

Utilizing parenting skill acquisition programs is essential for PWB of mothers of children with HL, as one of the most important dimensions is establishing a strong mother-child relationship. The present study demonstrated that the Faranak Program has a significant effect on the PWB of mothers and their 6 dimensions, and its effectiveness was statistically significant after at least 4 months of follow-up. The Faranak Program, a group-based, parent-centered, and joyful program, facilitated a stronger mother-child relationships and improved the connections among mothers compared to other aspects of wellbeing. This result could be due to the following reasons: One possible reason is that this research was performed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which brought about high levels of stress, isolation, and reduced social connections. Another possible reason could be the reduction of feelings of loneliness that mothers might experience when dealing with DHH children by meeting time of mothers who have overcome similar challenges. They also realized that other mothers confronted similar challenges, allowing them to consult with one another.

The results of this study on the effect of the Faranak program on the improved relationship between mother and child, as well as among the mothers, were in accordance with other studies, such as Carroll [22], Weis [21], Terrett, White, and Terrett [19], and Koohi et al. [23]. In all mentioned studies, songs, rhymes and lullabies have been used as tools to help parents in building stronger relationship with children who have HL. For example, the results of the study by Koohi et al. revealed an effect size of 0.64 after the implementation of the Faranak program on the relationship between mothers and children with HL. This effect size was higher than the one obtained in the present study (0.44). A possible reason for the greater effect observed in the study by Koohi et al. may be attributed to the in-person format of the Faranak program rather than online.

Many studies have been conducted to improve the PWB in mothers of children with HL using various intervention strategies. For instance, Foladi et al. investigated the effect of “group narrative therapy” on PWB in mothers of children with hearing impairment [29]. They demonstrated an effect size of 0.66 following the implementation of group narrative therapy on PWB in mothers, which was higher than the effect size obtained in the present study (0.54). However, due to the differences in time and location, as well as the variations in the implementation of the research between these two studies (this study and the study conducted by Foladi et al.), it cannot be certainly stated that the group narrative therapy approach was more effective than the Faranak program. However, further research must be conducted to compare the effect size on mothers of children with HL.

In this study, the Faranak program enhanced the mother-child relationship with an effect size of 0.44. However, Abbaszadeh et al., who applied the “positive parenting program” as an intervention strategy to improve the relationship, reported no statistically significant effect [30]. It seems that several factors have influenced their research outcomes, consisting of the differences in tools, the inadequacy of intervention content, the limited focus on coping strategies for mental health issues, and the acceptance of hearing impairment by mothers. Abbaszadeh’s research was conducted in Tehran, Iran, under specific time and social conditions, and parents could not access online methods, which led to the discontinuity of the training sessions. The present study was performed in smaller cities where parents were already familiar with the center and instructors and easy access to online methods, leading to continuity of training sessions. However, although both studies were conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, the research conditions were entirely different.

There are some limitations in this study. This research was implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, and it suffered from social isolation, which may have a greater impact on outcome measures compared with post-COVID-19 pandemic conditions. Furthermore, as the sessions were held online (audio and video), the effect size of the face-to-face program may differ from what was estimated through an online program. Since the study was conducted in two small cities in Iran, the results cannot be generalized to all Iranian mothers and, of course, mothers in the world.

Conclusion

This research demonstrated a positive statistically significant effect of the Faranak P-CMGP on the PWB in mothers of DHH children. The interactions created during this program provided a platform for mothers to increase their knowledge about building relationships with DHH children through songs, rhymes, and lullabies. The Faranak program effectively promoted personal growth, autonomy, and PWB for mothers while also creating an opportunity for social connections among the mothers. The present study also indicated that strengthening the parent-child relationship, especially for mothers with DHH children, can be easily achieved by implementing the Faranak program. However, further research with a larger sample size seems necessary. It is recommended that educators of children with HL and early intervention specialists benefit from this program alongside other educational and rehabilitation programs for children with HL. Additionally, conducting online group programs can be a suitable alternative for mothers who cannot attend face-to-face sessions for any reason, allowing them to benefit from the Faranak program.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shiraz University, Iran (Code: SEP.14023.48.4840). Written informed consent was obtained the mothers of all children.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master’s thesis of the second author at the Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Faculty of Education and Psychology, Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Somayeh Sadat Sadati Firoozabadi, Guita Movallali, and Hakimeh Sadeghikhah; Implementing P-CMGP, data collection, and data analysis: Tahereh Soleimanieh-Naeini and Hakimeh Sadeghikhah; Writing, review & editing: Somayeh Sadat Sadati Firoozabadi, Tahereh Soleimanieh-Naeini, and Guita Movallali; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the mothers and children who participated in this study and the authorities of the family centers for deaf and hard of hearing children in Borazjan and Ganaveh counties in Bushehr, Iran, for their cooperation in this research. The authors also would like to thank Dr. Nikta Hatamizadeh and Dr. Enayatollah Bakhshi for their invaluable guidance.

References

- WHO. Deafness and hearing loss. Geneva: WHO; 2024. [Link]

- Marriage J, Brown TH, Austin N. Hearing impairment in children. Paediatrics and Child Health. 2017; 27(10):441-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.paed.2017.06.003]

- Szarkowski A, Toe D. Pragmatics in deaf and hard of hearing children: an introduction. Pediatrics. 2020; 146(Supplement_3):S231-6. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2020-0242B] [PMID]

- Theunissen SC, Rieffe C, Netten AP, Briaire JJ, Soede W, Schoones JW, et al. Psychopathology and its risk and protective factors in hearing-impaired children and adolescents: A systematic review. JAMA Pediatrics. 2014; 168(2):170-7. [DOI:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3974] [PMID]

- Russ SA, Kuo AA, Poulakis Z, Barker M, Rickards F, Saunders K, et al. Qualitative analysis of parents’ experience with early detection of hearing loss. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2004; 89(4):353-8. [DOI:10.1136/adc.2002.024125] [PMID]

- Majorano M, Guerzoni L, Cuda D, Morelli M. Mothers’ emotional experiences related to their child’s diagnosis of deafness and cochlear implant surgery: Parenting stress and child’s language development. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2020; 130:109812. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.109812] [PMID]

- Kobosko J, Geremek-Samsonowicz A, Skarżyński H. [Mental health problems of mothers and fathers of the deaf children with cochlear implants (Polish)]. Otolaryngologia Polska = The Polish Otolaryngology. 2013; 68(3):135-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.otpol.2013.05.005] [PMID]

- Szarkowski A, Birdsey BC, Smith T, Moeller MP, Gale E, Moodie STF, et al. Family-centered early intervention deaf/hard of hearing (FCEI-DHH): Call to Action. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2024; 29(SI):SI105-1. [DOI:10.1093/deafed/enad041] [PMID]

- Karademas EC. Positive and negative aspects of well-being: Common and specific predictors. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007; 43(2):277-87. [DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2006.11.031]

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology. 2001; 52:141-66. [DOI:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141] [PMID]

- Sanders MR, Markie-Dadds C, Tully LA, Bor W. The triple P-positive parenting program: A comparison of enhanced, standard, and self-directed behavioral family intervention for parents of children with early onset conduct problems. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000; 68(4):624-40.[DOI:10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.624] [PMID]

- Luterman D. Counseling the communicatively disordered and their families. Little Brown: Boston,1984. [Link]

- Sanders MR. Triple P-Positive parenting program: Towards an empirically validated multilevel parenting and family support strategy for the prevention of behavior and emotional problems in children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999; 2(2):71-90. [DOI:10.1023/A:1021843613840] [PMID]

- Sangha K, McLean C, Spark K. Bowness montgomery parent-child mother goose program. California: WordPress Developmen; 2009. [Link]

- Hashmi S MJ, Movallali G, Karakatsanis A, Cho I, Adler M, Jones M A, et al. Parent-Child Mother Goose Program. [Internet]. 2024 [Updated 2024 January 1st]. Available from: [Link]

- Bray K PLC, Fulton S, Tuck J, Davin L, Dann OAM M. Parent-Child Mother Goose Australia. [Internet]. 2024 [Updated 2024 January 1st].

- Weber N. Parent-child mother goose program research. 2018. [Link]

- Weber N. Exploring the impacts of the parent-child mother goose program [MA thesis]. Alberta: University of Alberta; 2017.[Link]

- Terrett G, White R, Spreckley M. A preliminary evaluation of the Parent-Child Mother Goose Program in relation to children’s language and parenting stress. Journal of Early Childhood Research. 2013; 11(1):16-26. [DOI:10.1177/1476718X12456000]

- Scharfe E. Benefits of mother goose. Child Welfare. 2011; 90(5):9-26. [Link]

- Weis DY. Impact of Parent-Child Mother Goose: Mothers’ perceptions and experiences of singing to their infants aged 6-28 months [PhD dissertation]. Victoria: University of Victoria; 2006.[Link]

- Carroll AC. Parents’ perceptions of the effects of the Parent-Child Mother Goose Program (PCMGP) on their parenting practices. Vancouver: University of British Columbia; 2005. [Link]

- Koohi R, Sajedi F, Movallali G, Dann M, Soltani P. Faranak Parent-Child Mother Goose Program: Impact on mother-child relationship for mothers of preschool hearing impaired children. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2016; 14(4):201-10. [DOI:10.18869/nrip.irj.14.4.201]

- Azizzadeh-Parikhani A, Shakeri-Moghanjoghi M, Movallali G. [The effect of Faranak Parent-Child Mother Goose Program on Improving speech and language skills of hearing-impaired children under 0-3 years old (Persian)]. Paper presented at: 3rd National Conference of Applied Studies in Education Processes. 7 October 2023; Minab, Iran. [Link]

- Ryff CD. Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989; 57(6):1069-81. [DOI:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069]

- Sefidi F, Farzad V. Validated measure of Ryff psychological well-being among students of Qazvin University of Medical Sciences (2009). Journal of Inflammatory Diseases. 2012; 16(1):65-71. [Link]

- Sadati Firoozabai S, Moltafet Gh. [Investigate psychometric evaluation of ryff’s psychological well-being scale in gifted high school students: Reliability, validity and factor structure (Persian)]. Quarterly of Educational Measurement. 2017; 8(27):103-19. [DOI:10.22054/jem.2017.11432.1332]

- Movallali G, Koohi R, Soleimanieh-Naeini T. [Faranak Parent-Child Mother Goose Program (Persian)]. Tehran: Raz-e-Nahan; 2018. [Link]

- Fooladi K, Ahmadi R, Sharifi T, Ghazanfari A. [Effectiveness of group narrative therapy on psychological wellbeing and cognitive emotion regulation of mothers of children with hearing impairment (Persian)]. Empowering Exceptional Children. 2021; 12(2):1-11. [DOI: 10.22034/ceciranj.2021.237671.1410]

- Abbaszadeh A, Movallali G, Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi M, Vahedi M. [Effect of Baby Triple P or Positive Parenting Program on Mental Health and Mother-child Relationship in Mothers of Hearing-impaired Children (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2021; 22(2):210-27. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.22.2.3258.1]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Exceptional Children Psychology

Received: 1/01/2024 | Accepted: 16/06/2024 | Published: 1/01/2025

Received: 1/01/2024 | Accepted: 16/06/2024 | Published: 1/01/2025

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |