Volume 25 - Special Issue

jrehab 2024, 25 - Special Issue: 604-635 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Takaffoli M, Vameghi M, Mowzoon H, Soleimani F, Ashour M, Hassanati F. Assessing Children’s Access to Speech Therapy Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Qualitative Study. jrehab 2024; 25 (S3) :604-635

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3423-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3423-en.html

Marzieh Takaffoli1

, Meroe Vameghi1

, Meroe Vameghi1

, Hoda Mowzoon2

, Hoda Mowzoon2

, Farin Soleimani3

, Farin Soleimani3

, Maryam Ashour1

, Maryam Ashour1

, Fatemeh Hassanati *4

, Fatemeh Hassanati *4

, Meroe Vameghi1

, Meroe Vameghi1

, Hoda Mowzoon2

, Hoda Mowzoon2

, Farin Soleimani3

, Farin Soleimani3

, Maryam Ashour1

, Maryam Ashour1

, Fatemeh Hassanati *4

, Fatemeh Hassanati *4

1- Social Welfare Management Research Center, Social Health Research Institute, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,fatemehhasanati64@gmail.com

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: COVID-19, Coronavirus, Speech therapy, Child, Iran, Accessibility, Rehabilitation services

Full-Text [PDF 2781 kb]

(982 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4931 Views)

Full-Text: (879 Views)

Introduction

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis worldwide, including Iran, the necessity of COVID-19 prevention and treatment has turned into a national priority for all communities. Although COVID-19 affected children around the world, the distribution of its consequences was not identical for all children in the world, and children and families who had been vulnerable were at a higher risk of deprivation and harm [1-4].

According to studies, children with disabilities and special needs have been one of the primary groups experiencing considerable inequalities, damages, and deprivations during the COVID-19 pandemic [1, 3-5]. Specifically, among the groups of children with special needs are children and adolescents with developmental communication disorders (such as autism, developmental delay and hearing loss) and swallowing disorders who need to receive rehabilitation services, particularly speech therapy, on a weekly or even daily basis. Speech therapy services are provided using various methods based on the disorder’s type and severity and the client’s needs and conditions. According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association classification, speech therapy services are provided in four ways, including public and private health services, at schools, and remote services [6]. A notable point regarding the speech therapy services required by children with special needs is that providing these services often requires face-to-face communication; however, with the onset of COVID-19 and imposing compulsory social restrictions, children’s access to face-to-face speech therapy services was seriously influenced by the various consequences of the pandemic [7]. Accessibility is a significant concept in health policies and health service research [8], meaning the opportunity and ability to use health resources under any condition [9]. Equitable access to healthcare services leads to improving the level of health and providing equal opportunities in society [10].

In different countries, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, numerous studies have investigated the adverse effects of challenges and restrictions related to COVID-19 control on creating restrictions on access to speech therapy services [11, 12 13]. For instance, Al Awaji, Almudaiheem [11] in Saudi Arabia assessed the nature of the changes in providing speech and language services during COVID-19. According to the caregivers’ reports, only 50% of the children had access to services and the majority of respondents reported stopping the treatment sessions. In the United States, Jeste, and Hyde [14] also evaluated the access status of children with developmental disorders to health and educational services. Their study population consisted of elementary school children. According to the parents’ reports, 74% of these children had access to medical and educational services, 36% had no access to healthcare providers, and only 56% reported that their children received some services in the form of remote education.

Regarding the consequences of reduced accessibility to speech therapy services, a major part of children in need of speech therapy services is in the specific and golden time of speech and language development; hence, any interruption in receiving services timely can cause permanent language, speech, and communication disorders in these children [11, 12, 15], culminating in decreased quality of life and psychosocial health for them and their families [12, 15]. On the other hand, as mentioned, these consequences are not identical for all children, further overshadowing some groups, including children with special needs [4]. Studies conducted in this regard have demonstrated that the pattern of referring and using services varies due to the living conditions of children and their caregivers [13]. For example, access to speech therapy services among urban and rural families has been different during the pandemic because of various distances from the centers or the inability to afford transportation costs [11, 16].

Accordingly, it is necessary and of high priority to pay attention to this group of children and investigate the effect of COVID-19 and its consequences on their access to rehabilitation services, including speech therapy. In Iran, children’s access to speech therapy services during the pandemic has not been specifically assessed. Therefore, a qualitative study can provide profound and detailed dimensions of the subject based on the perspectives and experiences of the individuals who experienced it, including speech therapists and caregivers. Hence, the current research aimed to comprehensively investigate the access status of children in Tehran City, Iran, to speech therapy services during the pandemic using a qualitative approach to examine both the participant’s experiences of the accessibility and the factors contributing to such access during this era [17].

Materials and Methods

Research type

In this study, the experiences related to the accessibility of speech therapists and children’s primary caregivers to in-person and remote services since the COVID-19 outbreak were investigated using the conventional content analysis method in Tehran between October and March 2022.

Study participants

The participants of this study consisted of speech therapists providing services to children and primary caregivers of children in need of speech therapy services. The inclusion criteria for therapists included having at least three years of speech therapy work experience before the onset of COVID-19 and holding at least a bachelor’s degree in speech therapy. The inclusion criteria for caregivers included having a child under 18 years of age with developmental speech, language and swallowing problems; their child’s participation in at least five speech therapy sessions (in-person or remote) before the onset of COVID-19 in a fixed speech therapy center in Tehran City, Iran, and the continuation of these sessions during the COVID-19 era to compare conditions; and parents’ reading and writing literacy to the extent of completing the consent form and understanding the questions.

Sampling procedure

Sampling started purposefully from speech therapists and the children’s primary caregivers and continued until reaching data saturation. To increase diversity in qualitative sampling, we selected specialists from different city districts and public and non-public centers (universities, public centers, charities, and private centers). Furthermore, for caregivers, we tried to select samples with the highest diversity in socioeconomic status, type of speech disorder, child’s age, type of therapeutic intervention, and treatment duration.

Data collection

This study collected participants’ experiences using semi-structured, in-depth interviews with speech therapists and children’s primary caregivers. The mean interview duration was about 74 min for therapists and 40 min for mothers. The central topics of the interview questions were as follows: participants’ experiences of changing the access of children and families to speech therapy services during the pandemic; the participants’ experiences of the characteristics of the child and family in their changed access to speech therapy services during the pandemic and participants’ experiences of receiving remote speech therapy services during the pandemic.

Data analysis

Findings obtained from in-depth interviews with specialists and primary caregivers were analyzed using MAXQDA software, version 2020 and the qualitative content analysis approach Graneheim and Lundman [18] Simultaneously with performing the interviews.

Trustworthiness and rigor

In Lincoln and Goba’s qualitative research, four criteria have been proposed for the trustworthiness and rigor of qualitative data: Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [19]. The research team attempted to elevate the credibility by engaging in the data for a long time and spending adequate time collecting and analyzing the data (about a year), applying various therapist-caregiver perspectives, conducting an acceptable number of interviews and reviewing data, and coding and categorizing by research team members at different stages. Regarding transferability, we increased participants’ diversity in the experience of the intended subject. Regarding dependability, all primary data collected from the interviews were carefully maintained and available at all stages; thus, it was possible to refer to the primary data several times to ensure the collection and analysis process. Moreover, meetings were held with the research team to ensure the presence of an equal and coordinated framework for data collection and analysis to ensure the research’s dependability. Ultimately, for confirmability, in addition to the precise and detailed recording of the whole work process, which made it possible to continue the process with other researchers, several interviews, codes, and categories were provided to other members of the research team, and the accuracy of these codes was checked and reviewed.

Results

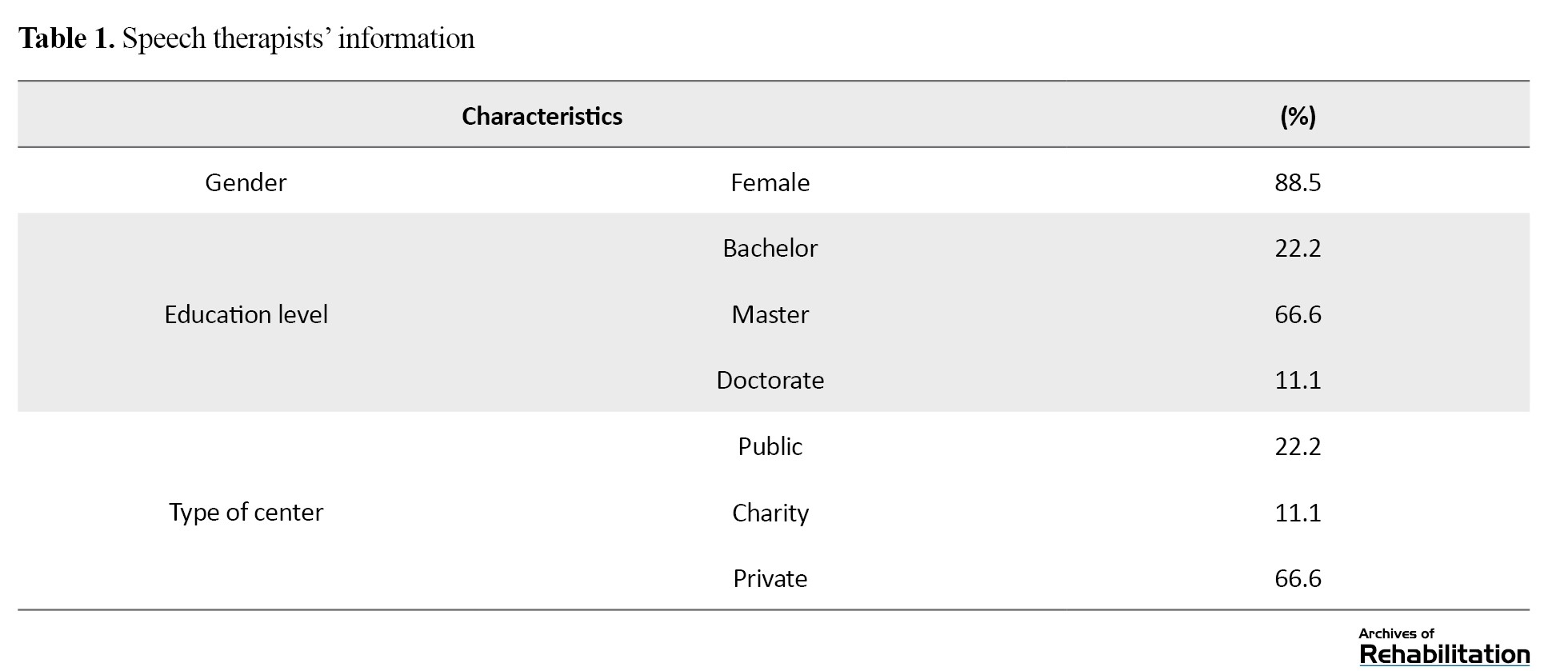

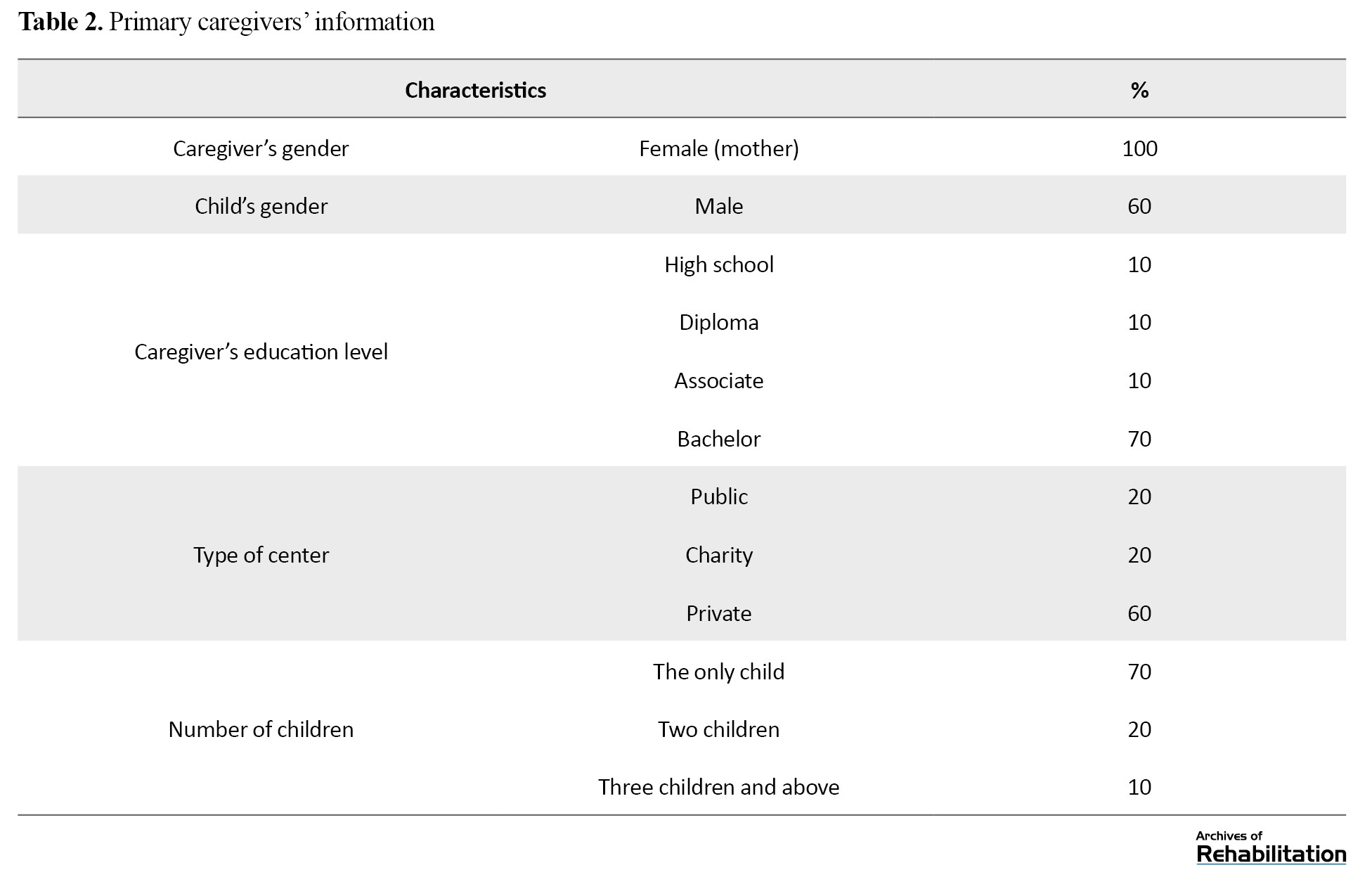

Participants’ characteristics

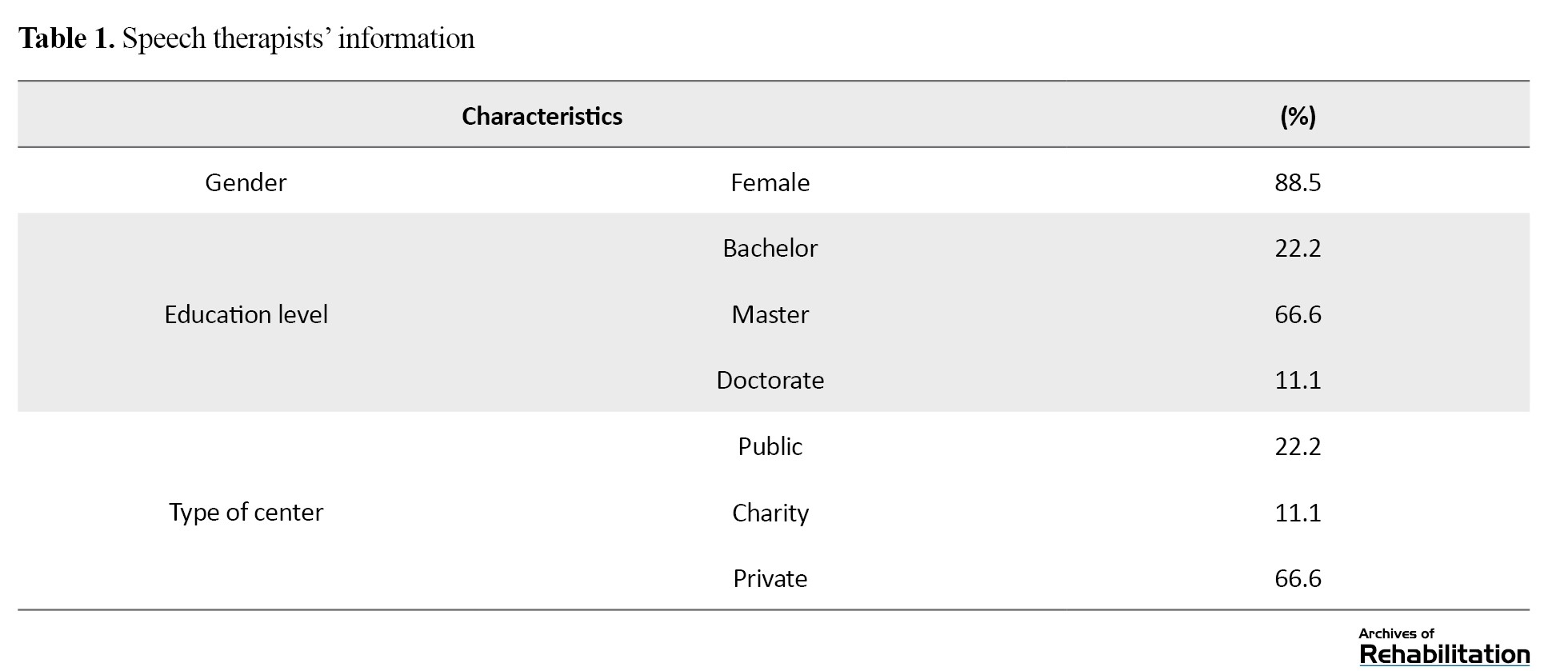

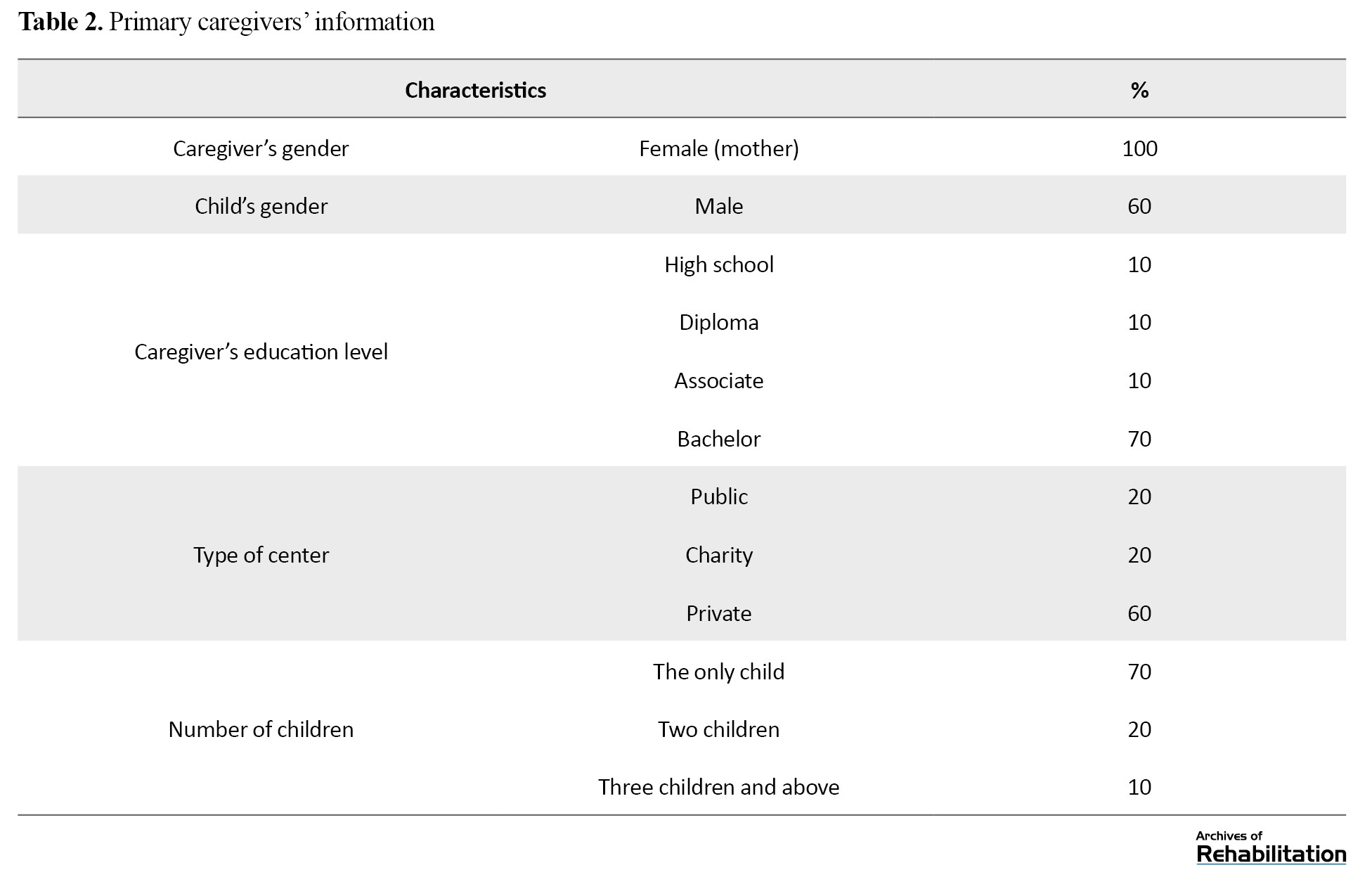

This study interviewed 9 speech therapists and 10 mothers in Tehran City, Iran, along with the children’s primary caregivers. The participants’ information is presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Status of children’s access to speech therapy services during the COVID-19 pandemic

The current research was conducted to determine the status of children’s access to speech therapy services during the COVID-19 pandemic and the role of social factors impacting this access in Tehran City, Iran. The findings of this study consist of four main categories: reduced accessibility, intensifiers of reduced accessibility, modifiers of reduced accessibility, and consequences of reduced accessibility. The following introduces these categories, and quotes are mentioned for each category.

Reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic

As shown in Table 3, according to the participants’ perspectives, during the COVID-19 period, the delay in early specialized diagnosis, inevitable changes in the treatment plan schedule and changes in the type of treatment plan all resulted in children’s reduced accessibility to these services.

Delay in early specialized diagnosis

The participants believed that during the pandemic, as a result of the temporary closure of centers and clinics, reduced specialists’ activities, assumed unnecessary to refer to speech therapy by doctors and families because of the fear of illness, and closure of schools or remote education at schools and kindergartens, as one of the major sources of early diagnosis of children’s speech and language problems- a considerable population of children were deprived of early diagnosis.

Changes in the treatment plan schedule

According to participants’ experiences, during this period, the usual treatment plan schedule also changed, leading to reduced children’s regular access to speech therapy services. During the pandemic, the number of sessions scheduled for a child’s treatment plan decreased due to considerations concerning complying with protocols, reducing working hours in centers, increasing families’ financial problems, and their inclination to be less present in public places. Also, due to the increased interval between clients to comply with health protocols in the clinics and, thus, reduced number of daily visits, the time interval between children’s treatment sessions also extended, which was a reason for the prolonged treatment process per se. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 era, particularly in the first two years of its peak, numerous interruptions were created in the scheduled sessions. These interruptions were considerable, particularly in the initial months when most centers were closed. There were also many other reasons causing serious disruption in the access to services, such as numerous peaks of COVID-19, infection of therapists, center staff, children, or family members with COVID-19 and the necessity of passing the quarantine period.

Changes in the type of treatment plan

From the participants’ perspectives, COVID-19 and its continuous peaks in Iran gave rise to changes in the type of speech therapy services. Some interventions were restricted and abandoned, such as oral massage that required touch and close contact with the child, interventions that required removal of the face mask, or interventions that were implemented with tools that could not be disinfected. Additionally, numerous medical centers discarded group therapy. Concerning speech therapy services at home, several therapists primarily restricted these services. On the other hand, the cost of these services was raised during the COVID-19 peak, so they were mostly available only to wealthy families. Another remarkable point mentioned both by caregivers and therapists was the dependency of the treatment of children with speech disorders on social and communication interactions in normal living environments, in which children’s social interactions became restricted during the pandemic, particularly in the first year.

The following quotes from the participants are related to the reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic main category:

“Since Abolfazl got constantly sick, I could not come every day. For example, I made an interruption for one month. I could not come back here until he improved because they said that they would not work with him if he had the slightest symptoms, so I had to let him get better to be able to come here” (caretaker No. 03; the subcategory of “interruption in treatment plan sessions”);

“Some families are so busy with their affairs that they do not have any time to do anything for their children except TV, cartoons, phones, etc. If it were not for the COVID-19 period, the child would go to kindergarten and preschool centers, and since the child was included in the educational system, the kindergarten trainer noticed that the child had a problem understanding the concepts. Due to the lack of such condition, they said, ‘We did not think at all that the child has such a problem.’” (speech therapist No. 07; the subcategory of “reduced accessibility to diagnostic resources in the education system”).

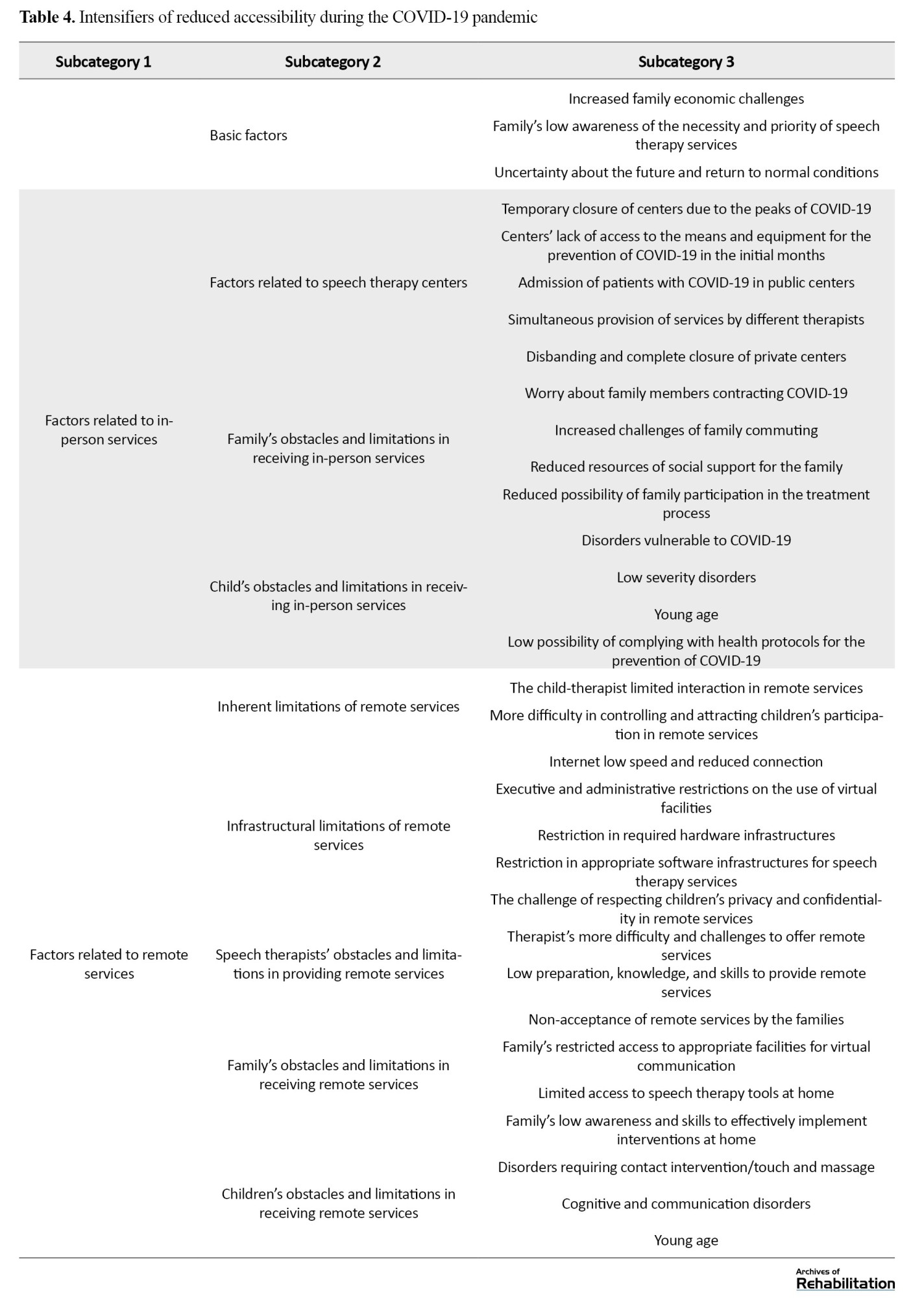

Intensifiers of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 Pandemic

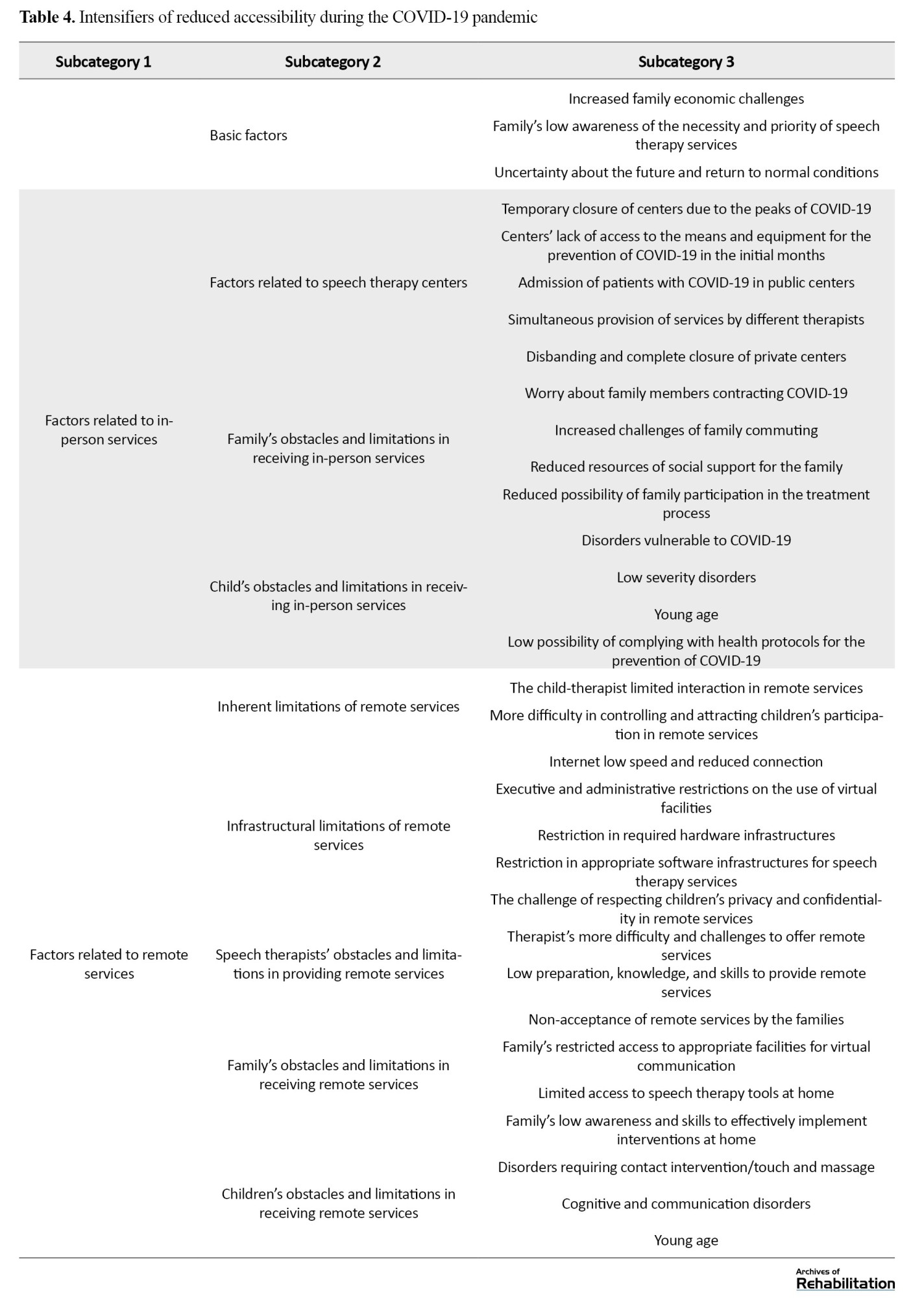

During the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in its first year, in addition to the changes that resulted in children’s reduced accessibility to speech therapy services, some factors intensified this limitation and reduced accessibility in various dimensions. These factors can be proposed in three main categories: Basic factors, factors related to in-person services, and factors related to remote services (Table 4).

Basic factors

The experiences of families and therapists in this study indicated that, on the one hand, the reduced income and, on the other hand, the increased cost of families during the COVID-19 period, specifically the increased cost of speech therapy services, led to the child’s non-continuation of treatment or non-referral for early intervention. Furthermore, compliance with health protocols (such as buying disinfectants or not using public transportation) doubled economic pressure on families. Concerning the reasons for the increased cost of speech therapy, it was suggested that given the high crowd of referrals and low compliance with health protocols in public centers, families were more inclined to private centers. Also, in this period, since home services became more challenging and transportation costs increased, the cost of home services increased. Another substantial factor was the low awareness of families regarding the golden age of development, the importance of early intervention, the necessity of speech therapy services in the pandemic conditions, and, consequently, the delay in receiving services.

Factors related to in-person services

At the level of in-person services, the intensifiers of reduced accessibility were divided into three sections: Factors related to speech therapy centers, the family and the child.

Factors related to speech therapy centers

The participants’ experiences indicated that except in the initial months of the onset of the pandemic, when most centers faced compulsory closure to control the pandemic, in the subsequent peaks of COVID-19, some private centers were temporarily closed for some time. In the initial months of the pandemic, there were problems in producing and distributing preventive equipment, including face masks and alcohol, this shortage of equipment culminated in reduced service provision. Furthermore, the change of use in the speech therapy departments in public centers to the specialized coronavirus departments or the proximity of private and public speech therapy centers to treatment centers for COVID-19 patients induced fear in families and seriously reduced their referral to speech therapy centers. Finally, during the pandemic, similar to many businesses, speech therapy centers also faced serious economic problems, resulting in the closure or displacement of many private centers.

Family’s obstacles and limitations in receiving in-person services

One of the most crucial factors that interrupted children’s access to in-person speech therapy services through referrals to centers was families’ concern about their child and their other children contracting COVID-19. This concern was higher in families who used public transportation or telephone and Internet taxis. Similarly, the families who went to Tehran medical centers from nearby villages and cities faced problems in the initial months of the pandemic because of intercity traffic restrictions. On the other hand, during the pandemic, access to relatives and nurses to care for children decreased, leading to more psychological burden, fatigue, and high responsibility of caregivers, consequently not visiting the centers. Also, before the pandemic, the simultaneous presence of caregivers in the waiting room of medical centers led to the shaping of a social support network of families. This support network was an incentive for families to continue treatment and the necessity of complying with health protocols led to the elimination or weakening of this network. At last, holding children’s school classes remotely and increasing the mother’s responsibilities were serious obstacles to mothers attending medical centers and exercising at home. In this regard, increasing the father’s role was also notable in this era. Many families reported that due to the father’s greater time of presence at home, family disputes increased due to reasons such as the father’s unemployment, disagreements about how to follow health protocols, and doubts about the efficacy of speech therapy interventions. Therefore, they encountered the father’s more serious opposition to continuing the treatment.

Child’s obstacles and limitations in receiving in-person services

According to the findings, COVID-19 prevention was the priority of families for children more vulnerable to COVID-19, such as children with cerebral palsy with a weaker immune system. For children with less severe disorders or children in the pre-language stage or at the preschool age, the family was less concerned about treatment. Thus, in significant cases, the golden age of these children was lost for timely intervention. For children with more severe mental disorders or younger children who did not understand health protocols, the family and even therapists preferred not to visit in person.

Factors related to remote services

During the pandemic, several centers and therapists provided remote speech therapy services. The participants noted that although this type of service provided access for some groups of children during the COVID-19 peak, this replacement gave rise to deprivation and reduced accessibility for other groups. In fact, for various reasons, these services were not provided by all centers and therapists or were not accepted by some families. Some of these factors are mentioned below.

Inherent limitations of remote services

From the participants’ perspectives, the child-therapist direct interaction was very important when receiving speech therapy services. In contrast, in remote services, the child-therapist immediate communication, particularly physical contact for interventions requiring touch and massage, became limited. In this regard, another obstacle was the low possibility of attracting the child’s participation and control and also controlling the conditions of the home as the treatment environment. The centers’ controlled settings and the child-therapist direct communication resulted in the child’s cooperation and the treatment’s efficacy; however, at home, the exercises were mostly not performed or performed with very low quality. Also, home conditions, including family disputes, crowdedness, the lack of private and quiet space, and the family’s skills in using remote services, affected the quality of services.

Infrastructural limitations of remote services

The presence of infrastructural limitations for remote services in Iran is a serious obstacle to the inclination of centers and the possibility of families accessing these services. Table 4 provides the details and dimensions of these infrastructural limitations of remote services from the participants’ perspectives.

Speech therapists’ obstacles and limitations in providing remote services

Speech therapists participating in this study believed that remote interventions required more time, and the possibility of professional relationship management was reduced during the pandemic. Also, given the Internet problems, the session duration for each family usually became more extended than the time of in-person sessions. Thus, speech therapists also needed to spend more time and money preparing educational content or reviewing videos sent by families than in-person sessions. Another obstacle was the unexpected and sudden conditions of COVID-19, which sometimes culminated in the sudden replacement of in-person services with remote services. At the same time, the therapists were not adequately prepared for these conditions. Most had low knowledge and skills to work with online network platforms, specialized speech therapy programs, principles and practices of providing remote services, and how to produce and disseminate educational content.

Family’s obstacles and limitations in receiving remote services

In this period, some families did not accept these remote services as a specialized intervention. One of the serious obstacles was the problems of access to speech therapy tools and appropriate facilities for remote communication due to the high cost of the Internet and holding school classes as remote and consequently, the need for concurrent access to multiple appropriate devices. Finally, the family’s low awareness and skills for effective implementation of interventions at home caused specialized speech therapy services not to be as effective as expected. Low knowledge and abilities were considerable in various dimensions, including low skills in working with electronic tools, applications, and software, low skills in the way of communicating with the child and attracting their cooperation and low skills and accuracy of the therapist in transferring the training and intervention to the child, leading not only to the child not progressing but also to increase their problems.

Child’s obstacles and limitations in receiving remote services

Children in need of oral massage and contact interventions, particularly those with swallowing disorders, and children who lack the cognitive ability to use communication media or lack the required communication and interaction ability due to their young age or the type of disorder did not have the opportunity to use remote services completely. Thus, according to the participants’ experiences, the service provision for some children was limited to education and counseling to the caregiver.

The following quotes from the participants are related to the “intensifiers of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic” main category:

“In any case, subjects whose jobs have been somehow affected by COVID-19, for example, taxi drivers or jobs of this type, their economic status was so affected that speech therapy services were no longer their primary priorities” (caregiver No. 09; the subcategory of “increased family economic challenges”);

“My husband was at home and did not let me do this. Nafiseh was crying; she did not cooperate to perform the exercises. My husband said, ‘Let her go; now it is not the time for this.’ He was working at home all day. My job was to do exercises when my husband was not around” (caregiver No. 08; the subcategory of “reduced possibility of family participation in the treatment process”);

“I mean, we should be taught. Why did we suffer so much? Because we did not know. I did not know how to use WhatsApp. I learned a lot by trial and error how to make a plan, how to communicate” (speech therapist No. 01; the subcategory of “low preparation, knowledge, and skills to provide remote services”).

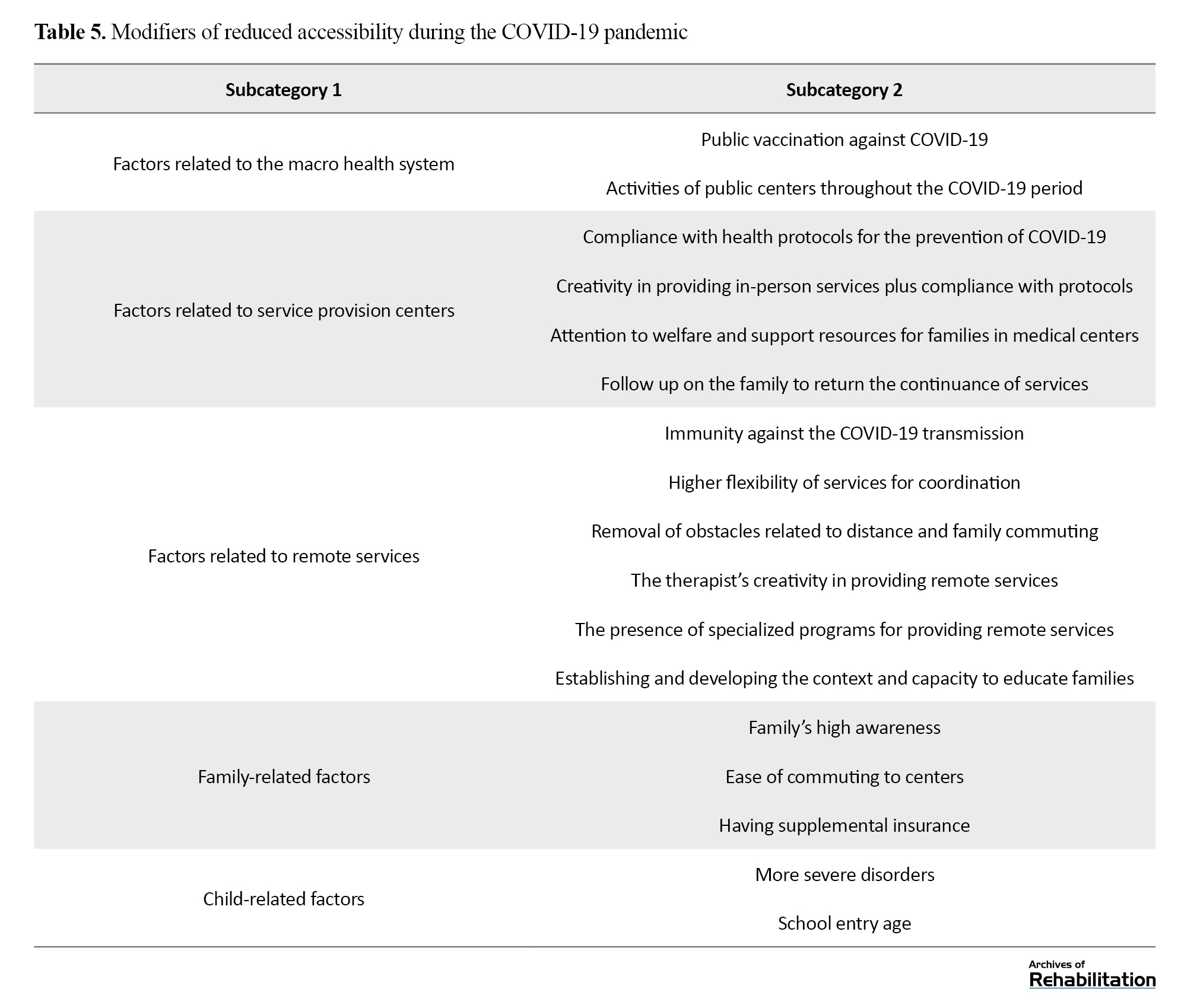

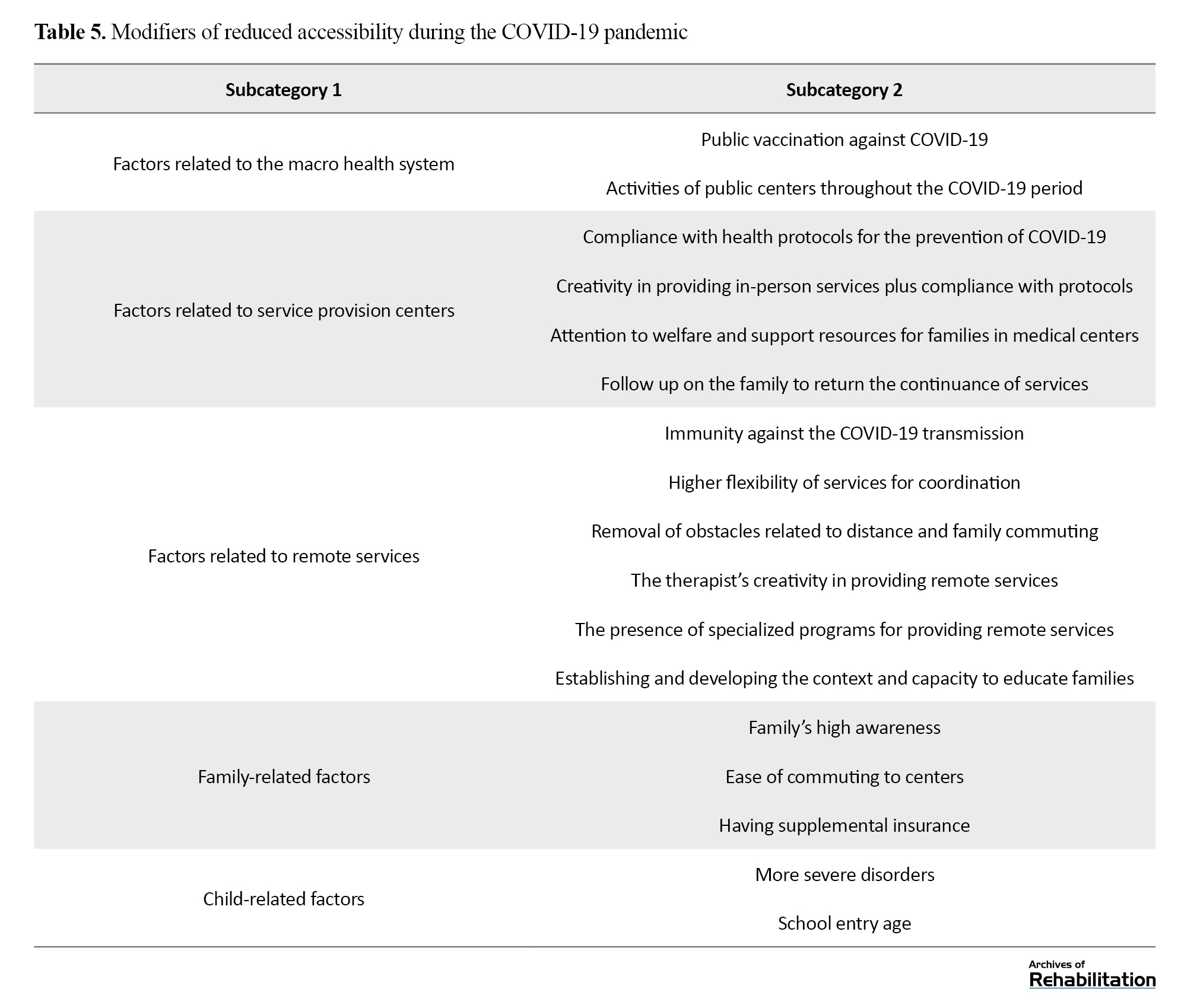

Modifiers of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic

According to the participants’ perspectives, during the pandemic, particularly in its first two years, some factors gradually took the role of modifiers of the created limitations in children’s access to speech therapy services, which, in some cases, even resulted in children’s full access to their needed services (Table 5).

Factors related to the macro health system

This study’s findings revealed that vaccination reduced disease severity and duration, as well as anxiety and worry about getting infected. Also, public centers were active from the onset of the pandemic and even at its peak. The caregivers who visited or made phone calls benefited from the required training for the minimum continuity of services during the pandemic’s peak.

Factors related to service provision centers

Concerning the facilitating role of centers in the continuation and return to services, one of the most significant factors was the degree of compliance with health protocols in the centers (physical structure and arrangement, such as proper ventilation, large waiting space, marked seats, and the use of face masks and alcohol by the staff of the centers), which helped enhance the confidence and mitigate the concerns of the families. Moreover, families exhibited more inclination for private centers, particularly single-therapist centers, due to low population density. On the other hand, using various creative methods, such as replicas or films instead of removing the face mask and reducing the physical distance, was the incentive and facilitator for families. Another critical factor was the centers’ efforts to follow up on the families to return to treatment after the closure during the initial months. Finally, the centers’ attention to welfare and support resources for families, including providing hygiene products, such as face masks or alcohol, increasing the discount possibility, using the network of donors and support resources outside the center, and facilitating the insurance process, were all incentives and facilitators for treatment continuation, particularly for the strata in the lower economic class.

Factors related to remote services

Developing appropriate remote services in centers and offering families the opportunity to combine or accompany them with in-person services played a remarkable role in families’ access to speech therapy services. In the first place, remote services were an appropriate alternative for families who were extremely worried about getting infected with COVID-19 so that their children would not be deprived of speech therapy services. Another essential advantage of remote services was resolving the challenges concerning commuting, particularly for children in cities and villages near Tehran. Considering the possibility for the family to receive remote services at home, at different times, and even on holidays, there was a higher flexibility for coordination, particularly for families with busy schedules and several children. Moreover, the therapists’ creativity in applying various remote educational and therapeutic methods could enhance the quality of remote communication and effectiveness. Finally, remote services have provided a foundation for increasing the awareness of families. During this era, various types of educational videos and materials were shared with the public on virtual networks, and therapists also prepared audio or video educational files for families following their child’s needs, which the family could review several times.

Family-related factors

A major factor in starting and continuing children’s treatment, even at the COVID-19 peak, was the family’s level of awareness. This awareness was manifested in various dimensions of children’s growth and development, as well as the necessity of the golden age of child development, the importance of speech therapy interventions, awareness of COVID-19 and ways of COVID-19 prevention, resulting in the fact that families did not forget speech therapy despite the concerns about COVID-19. On the other hand, in receiving in-person services, families emphasized that their proximity to medical centers and having a private vehicle reduced their costs and worry about illness. Finally, supplementary insurance was also crucial in facilitating access to services.

Child-related factors

Families were more concerned about treatment interruptions for children involved in more serious disorders, such as severe Autism. Additionally, for school-aged children, due to the feeling of pressure stemming from the assessment program for the child’s admission to the school, the family placed more importance and priority on speech therapy.

The following quotes from the participants are related to the “modifiers of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic” main category:

“Even a clinic that is a single-therapist center, I mean because I am the only therapist. Since it was my clinic, those who already recognized me knew that I was the only therapist and there was no one else there, except me, and a secretary. So, they were slightly more assured. Such individuals came back again, and they were assured” (speech therapist No. 03; the subcategory of “compliance with health protocols”);

“In that one year when they closed the clinic, I did not take Abolfazl there. Although there was COVID-19, I always wanted the sessions to be in-person because it was my son’s golden age, and my son had to go to school. Whatever it was, Abolfazl had to go to school. Whatever happened, I did not care much. However, the clinics were closed. I did not fear COVID-19; I feared my son not going to school” (caregiver No. 03; the subcategory of “family’s high awareness”);

“When the new cases arrived, the conditions were critical. It means that the family could not afford it anymore; the situation was terrible. They had already said that age was increasing and they could not do anything. The Autism case is so terrible. There are so many pronunciation errors. A terrible learning disorder that is very distinct and obvious. Such individuals started calling and came” (speech therapist No. 07; the subcategory of “more severe disorders”).

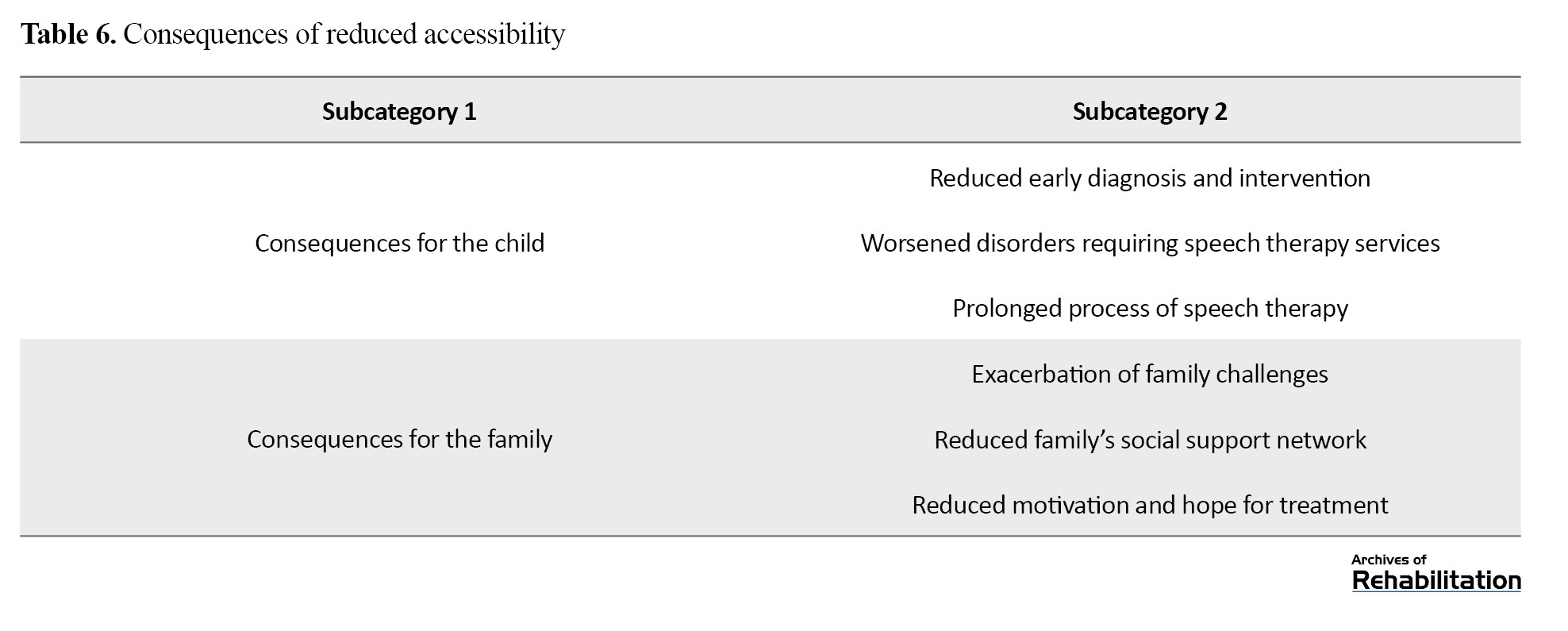

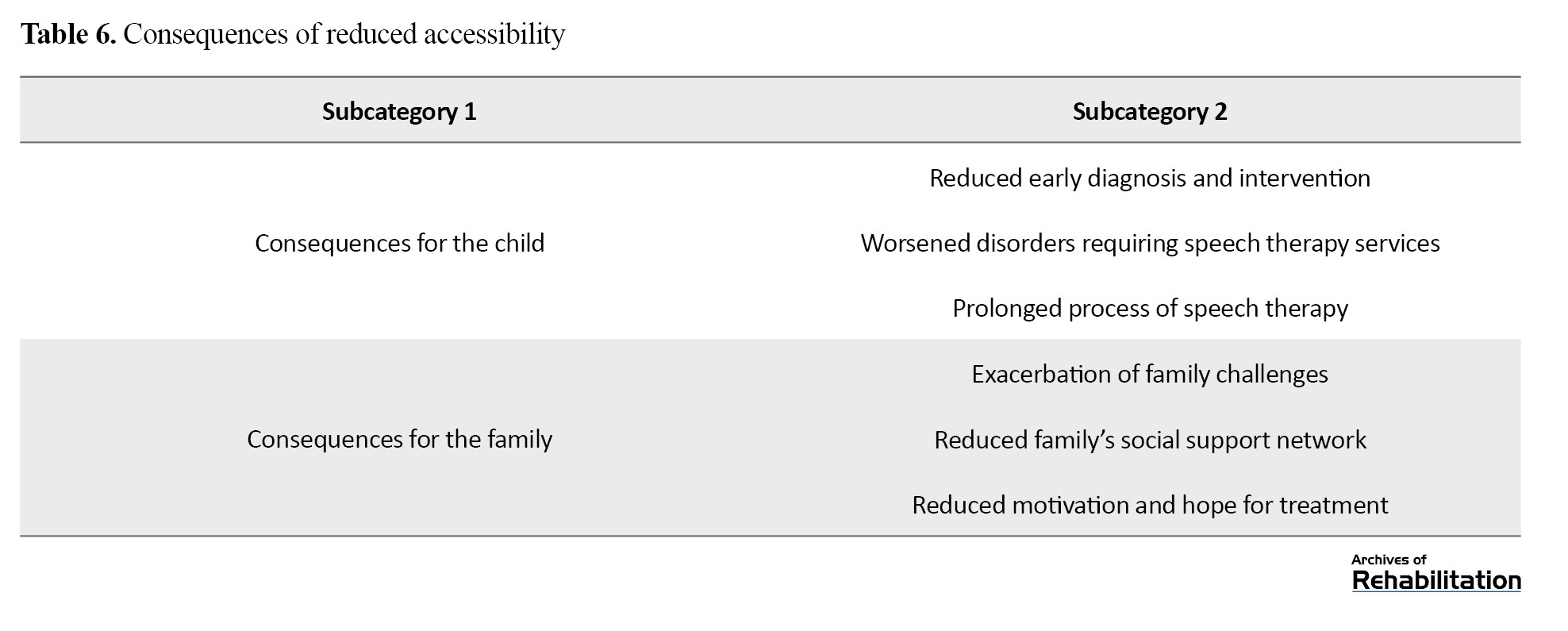

Consequences of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic

Finally, the findings of the present study are related to the consequences of reduced accessibility to services due to COVID-19. As shown in Table 6, children’s reduced accessibility to speech therapy services has negatively affected the child and the family.

Consequences for the child

During the pandemic, the less presence of children and families in public places, particularly at school and kindergarten, caused children’s problems and disorders not to be diagnosed timely or the possibility of visiting a specialist timely not to be made. Furthermore, due to the interruption of treatment, reduced quality of services or non-continuation of specialized interventions, and reduced social interactions of children during this period, all types of disorders worsened, and cases such as delayed speech became more common.

Consequences for the family

Children’s reduced accessibility to speech therapy services during the pandemic, in addition to having negative consequences for children, affected families, and caregivers as well. During this era, conflicts between parents regarding the necessity of receiving services and managing the challenges of accessing services intensified. Moreover, caregivers’ reduced commuting to treatment centers and also their less interaction with each other when attending the centers due to complying with social distancing were obstacles to creating motivation and hope for their children’s treatment.

The following quotes from the participants are related to the “consequences of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic” main category:

“The children born in this period passed the important development period in under two years of this social, communication, and verbal isolation process. Now the child is two and a half years old, is three years old, and still cannot talk. I provided counseling to many of them, to the family, to create this communication, social, and verbal enrichment process for the child, and after three months or four months, I followed up again; a large percentage of them were placed in the normal growth process after the child’s enrichment” (speech therapist No. 02; the subcategory of “worsened disorders requiring speech therapy services”);

“For example, because of my husband’s unemployment, we had disputes and fights. When he did not go to work, this made him say, ‘Do not send him to speech therapy sessions to reduce the costs.’ I said, ‘No, I must send him. We can reduce eating, but he must go to speech therapy.” (Caregiver No. 06; the subcategory of “exacerbation of family challenges”).

Discussion

This study investigated the experiences of speech therapists and children’s primary caregivers regarding children’s access to speech therapy services during the COVID-19 pandemic. The findings indicated that the dominant experience was children’s reduced accessibility to these services in Tehran, particularly in the first year. Intensifiers and modifiers dynamically influenced the understanding of reduced accessibility. Over time and with the decreased likelihood of contracting the disease, modifiers had a greater influence or intensifiers became weaker so that after the second year of the pandemic until the time of conducting the study, the participants’ experiences revealed a return to relatively normal conditions of the pre-COVID-19 era.

Regarding the “reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic” main category, the assessment and comparison of the findings of this study with other studies primarily showed the different dimensions and forms of this reduced accessibility. For instance, a study in Turkey on children with cerebral palsy demonstrated that <2% of children used rehabilitation services during quarantine [20]. Another study in India on children with neurodevelopmental disorders suggested the suspension of all speech therapy plans in centers during the quarantine period and also the continuation of home services [21]. According to a study in China, >13% of children with autism spectrum disorder did not receive any services. Only 30% visited the related centers to receive services, and about 20% performed exercises at home. During quarantine, despite having access to remote and home services, one-third of parents reported that they did not receive timely and helpful counseling and rehabilitation [22].

Regarding the “intensifiers of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic” main category, in the present research, the participants’ experiences indicated that during this period, particularly in the first year, some factors at the level of centers, families and children, both for in-person and remote services, played the role of intensifiers of the reduced accessibility. Concerning family-related factors, a study in Turkey demonstrated that the high level of anxiety of parents of children with cerebral palsy and their concern about the child and family members getting infected with the disease could be among the factors worsening these parents’ anxiety and worry and consequently the priority of keeping the child at home [20]. In a study in the rural regions of Nepal, it has been reported that the COVID-19 pandemic has culminated in reduced accessibility of children with cleft lip and palate to speech therapy centers that provide services due to these children’s limited ability to travel to nearby areas [16]. Regarding child-related factors, various studies also mentioned the greater vulnerability of some groups of children to COVID-19, including children with autism [22], cerebral palsy [20] and Down syndrome [23], by restricting commuting and social interactions, these children remained immune from the disease, but it led them to be deprived of the required rehabilitation services, including speech therapy.

A review of studies on children’s speech therapy during the pandemic demonstrated that a considerable part of these studies had dealt with remote services in this era and their contribution to increased access to speech therapy services. Most of the studies underscored that although these services had existed before the pandemic in many countries, the COVID-19 pandemic and measures related to its control gave rise to an unprecedented transformation in remote medical and rehabilitation services [24]. Despite the presence of some challenges in the use of remote rehabilitation interventions, this method is an appropriate option both for the COVID-19 period and even for non-pandemic conditions for individuals and children who are not able to visit in person [16, 25-27]. For instance, in a study on autistic children, it was found that >25% of parents used remote rehabilitation training and >40% reported that they could receive remote counseling services whenever they desired [22]. In various studies, the high effectiveness of these services [27, 28] and, in some cases, the low effectiveness of these services has been reported [16, 23, 29]. These discrepant findings can be attributed to the type of speech therapy and rehabilitation intervention, children’s conditions, and the context under investigation. The current research confirmed that despite the remote services’ substantial role in the increased access for groups of children, these services were not usable and accessible for everyone. In line with the present research results, numerous studies have investigated the obstacles and challenges of remote services. Various studies have mentioned obstacles, such as the importance of direct interaction in speech therapy and the elimination of this factor in remote services [16, 30], difficulties in attracting the child’s participation and companionship due to their lack of concentration in the home environment and the high number of distractions [16, 31], the therapist’s lack of concentration in the workplace or home due to the lack of dedicated space [31], the lack of clinical evidence for the child’s comprehensive assessment [26, 30, 31] and also the challenges in providing and observing therapeutic interventions in the context of the child’s daily life and family [31].

Concerning the obstacles related to remote service facilities, a study in Iran investigated the obstacles of remote rehabilitation interventions and mentioned infrastructure problems, such as shortage of specialized equipment, Internet problems and problems related to maintaining information security [32]. Moreover, a study in the rural regions of Nepal mentioned the issue of Internet connections and non-clarity of sound during sessions [16]. Studies in Canada and England also reported the need for efficient technology infrastructure and access to appropriate [24, 31]. Regarding speech therapists’ limitations, various studies have suggested the lack and necessity of therapist training and preparation for remote services [24, 30, 32]. A study in India demonstrated that only about 16% of speech therapists had received formal training to use remote treatment [30]. Furthermore, as proposed by the participants of this study, family participation is more important in remote services than in-person services. Hence, attracting family participation is more complicated and challenging because of the family’s lack of direct interaction, acceptance, and low awareness and skills [31]. On the other hand, according to studies in different countries, families who did not have proper access to virtual tools and facilities for economic reasons [16, 33] or had low levels of digital literacy [33] were less likely to use remote services. In addition, regarding the children, based on the experiences of families and therapists in various studies, children who lacked high tolerance and resilience for therapeutic activities, stable mental states, and sufficient strength to focus on the mobile screen or laptop were at a young age [31]. Also, children, such as those with Down Syndrome, who are highly dependent on direct social interactions [23], were less able to use remote services. The results of the mentioned studies are also consistent with the results of the present study.

One of the main categories extracted from the interviews was related to “modifiers of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Based on the findings, some factors also culminated in children’s increased access to services. Regarding family-related factors, a study in India showed that parents’ high awareness and motivation toward specialized interventions were among the factors making families able to cope with the challenges of the pandemic, particularly during quarantine, leading to the continuance of the child’s interventions [21]. Regarding remote services, similar to the experiences of the participants in the present study, reduced risk of infection for both the therapist and the child and the possibility of providing services to patients with COVID-19 [34], no need to commute and removal of commuting obstacles, particularly for rural children [16, 27, 31], and more convenient scheduling and more flexibility in providing services for both the therapist and the family [16, 27, 31, 34], all encouraged families and therapists to use remote services. A study in Canada suggested the notable role of the therapist’s preparation, experience, and skill in the acceptance and participation of the family and the child in remote speech therapy services, enhancing the effectiveness of these services. Moreover, the therapist’s capacity and ability for creativity in communication, such as using hand puppets, the ability to establish good communication, exchange information, and coordinate various dimensions of the child-related services, the therapist’s preparation, experience, and skill to attract the child’s companionship and participation, the ability to manage and attract the parents’ participation, and the therapist’s ability to pay attention to the needs of the child and the family play a vital role in encouraging the family and the child to use the services [31]. Furthermore, studies pointed to the cost-effectiveness of remote services compared to in-person services [34]. The experiences of the participants in this study in Tehran City, Iran, were diverse in this regard. In some cases, it was suggested that the costs of the sessions were equal to or even more expensive than in-person sessions. In general, some families, despite eliminating the commuting costs, still regarded the costs of these services as high because they believed that the major part of the responsibility was on their shoulders. On the other hand, unlike the experiences of the participants in the present study, holding and continuing group therapy for parents and children resulted in elevating the effectiveness of services and also motivating them to continue remote services [31]. The development of reimbursement and insurance policies for remote services also encouraged families to receive these services during the pandemic [33].

Finally, “consequences of reduced accessibility” for both the child and the family was another main category obtained from the participants’ experiences. In line with the findings of the current research, the behavioral regressions of children with neurodevelopmental disorders, particularly in children with Autism and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder [21], and the reduced language, cognitive, and motor abilities of children with Down syndrome despite receiving remote sessions due to the reduction of social interactions [23] have been reported in relevant studies. Based on the findings, families with children in need of speech therapy services also encountered challenges during this era due to various reasons, including children’s reduced accessibility to their required services. Numerous studies mainly conducted using quantitative methods addressing the mental health of parents having children with rehabilitation needs in this era reported parents’ increased stress and anxiety. Among the central reasons addressed in these studies were interruptions in rehabilitation services, lack of regular treatment for children, concern about the worsening of children’s problems, how to implement rehabilitation interventions at home, and the reduced social support during this period [17, 20-22, 33]. In a study in China, 50.7% of parents with autistic children reported superficial stress and 36.5% reported high levels of stress; 90% of these parents stated that the child’s non-cooperation due to distraction and their difficulty in emotional control for the interventions and exercises they have to do at home were the leading causes of stress [22]. In another study, parents of children with cerebral palsy mentioned the interruption in rehabilitation services as one of the causes of their anxiety, and the anxiety of caregivers who did not perform home exercises for their children was significantly higher than those who did. Caregivers of children with cerebral palsy who had speech disorders, behavioral problems, and mental retardation also experienced higher levels of anxiety than caregivers of children without these problems [20]. In a study in France on children with physical disabilities, 72% of parents expressed that their main concern was their child’s rehabilitation, and 60% complained about the lack of support and help during this period [17].

Conclusion

The current research is one of the few studies in Iran that investigated the issue of children’s access to rehabilitation services during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results of the present research demonstrated that the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in its initial months, greatly reduced the access of children in need of speech therapy services both in early diagnosis and in the quantity and types of intervention required, culminating in negative consequences both for the child and the family. This study, with a comprehensive viewpoint and from the perspective of the main stakeholders, revealed that intensifiers of reduced accessibility to in-person and remote services at different infrastructure levels, centers, children, and families can be investigated and pondered. Also, according to the findings, both macro health policies and medical centers, on the one hand, and the characteristics of the child and family, on the other hand, can play a crucial role in facilitating access. Moreover, substituting various types of remote therapeutic interventions could compensate for different degrees of limitations for different groups of children, but not all. This study indicated the inequality experienced by different groups of children in accessing in-person and remote services during the COVID-19 crisis. Hence, it can help the policymakers and planners of the health and rehabilitation system and managers and experts at speech therapy centers to adopt policies and measures in similar cases to adjust the intensifiers of reduced accessibility and reinforce the facilitators of access. Regarding the continuation and acceptance of remote services in the rehabilitation system, it should be noted that remote speech therapy in Iran is at the beginning of its route and requires infrastructure and policies to reinforce and develop it. However, the findings of this study demonstrated that for fair access to speech therapy and other remote rehabilitation services, the access of all children and their families, particularly low-income families, must be assured, and the necessary foundation for fair services must be provided.

Study limitations

This study faced some limitations. One of these limitations was related to much efforts made to make a primary caregiver other than the mother participate in this study; however, access to such samples was not possible due to the inclusion criteria. On the other hand, concerning the research suggestions extracted from this study, it can be suggested that the challenges and problems of providing speech therapy services under pandemic conditions be investigated using a survey of a larger statistical population. The status of access to remote speech therapy services for different groups of children and its challenges for the speech therapists themselves can also be investigated in a study with a larger statistical population and even at the national level.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science (Code: ID IR.USWR.REC.1401.090). All the interviews were performed after obtaining an informed written consent form and the participants’ information was stored and reported as coded anonymously.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science (2861/T/01).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Marzieh Takaffoli, Fatemeh Hassanati, and Farin Soleimani; Formal analysis: Marzieh Takaffoli, Meroe Vameghi, Hoda Mowzoon, and Maryam Ashour; Methodology: Marzieh Takaffoli, Hoda Mowzoon, and Maryam Ashour; Writing original draft: Marzieh Takaffoli and Hoda Mowzoon; Supervision:Meroe Vameghi and Farin Soleimani; Data validation: Farin Soleimani and Meroe Vameghi; Project administration: Marzieh Takaffoli and Fatemeh Hassanati; Writing, review and editing: Marzieh Takaffoli and Fatemeh Hassanati; Investigation and funding: Fatemeh Hassanati.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the speech therapy center managers, speech therapists, and mothers who participated in this research.

References

With the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic crisis worldwide, including Iran, the necessity of COVID-19 prevention and treatment has turned into a national priority for all communities. Although COVID-19 affected children around the world, the distribution of its consequences was not identical for all children in the world, and children and families who had been vulnerable were at a higher risk of deprivation and harm [1-4].

According to studies, children with disabilities and special needs have been one of the primary groups experiencing considerable inequalities, damages, and deprivations during the COVID-19 pandemic [1, 3-5]. Specifically, among the groups of children with special needs are children and adolescents with developmental communication disorders (such as autism, developmental delay and hearing loss) and swallowing disorders who need to receive rehabilitation services, particularly speech therapy, on a weekly or even daily basis. Speech therapy services are provided using various methods based on the disorder’s type and severity and the client’s needs and conditions. According to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association classification, speech therapy services are provided in four ways, including public and private health services, at schools, and remote services [6]. A notable point regarding the speech therapy services required by children with special needs is that providing these services often requires face-to-face communication; however, with the onset of COVID-19 and imposing compulsory social restrictions, children’s access to face-to-face speech therapy services was seriously influenced by the various consequences of the pandemic [7]. Accessibility is a significant concept in health policies and health service research [8], meaning the opportunity and ability to use health resources under any condition [9]. Equitable access to healthcare services leads to improving the level of health and providing equal opportunities in society [10].

In different countries, including Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, numerous studies have investigated the adverse effects of challenges and restrictions related to COVID-19 control on creating restrictions on access to speech therapy services [11, 12 13]. For instance, Al Awaji, Almudaiheem [11] in Saudi Arabia assessed the nature of the changes in providing speech and language services during COVID-19. According to the caregivers’ reports, only 50% of the children had access to services and the majority of respondents reported stopping the treatment sessions. In the United States, Jeste, and Hyde [14] also evaluated the access status of children with developmental disorders to health and educational services. Their study population consisted of elementary school children. According to the parents’ reports, 74% of these children had access to medical and educational services, 36% had no access to healthcare providers, and only 56% reported that their children received some services in the form of remote education.

Regarding the consequences of reduced accessibility to speech therapy services, a major part of children in need of speech therapy services is in the specific and golden time of speech and language development; hence, any interruption in receiving services timely can cause permanent language, speech, and communication disorders in these children [11, 12, 15], culminating in decreased quality of life and psychosocial health for them and their families [12, 15]. On the other hand, as mentioned, these consequences are not identical for all children, further overshadowing some groups, including children with special needs [4]. Studies conducted in this regard have demonstrated that the pattern of referring and using services varies due to the living conditions of children and their caregivers [13]. For example, access to speech therapy services among urban and rural families has been different during the pandemic because of various distances from the centers or the inability to afford transportation costs [11, 16].

Accordingly, it is necessary and of high priority to pay attention to this group of children and investigate the effect of COVID-19 and its consequences on their access to rehabilitation services, including speech therapy. In Iran, children’s access to speech therapy services during the pandemic has not been specifically assessed. Therefore, a qualitative study can provide profound and detailed dimensions of the subject based on the perspectives and experiences of the individuals who experienced it, including speech therapists and caregivers. Hence, the current research aimed to comprehensively investigate the access status of children in Tehran City, Iran, to speech therapy services during the pandemic using a qualitative approach to examine both the participant’s experiences of the accessibility and the factors contributing to such access during this era [17].

Materials and Methods

Research type

In this study, the experiences related to the accessibility of speech therapists and children’s primary caregivers to in-person and remote services since the COVID-19 outbreak were investigated using the conventional content analysis method in Tehran between October and March 2022.

Study participants

The participants of this study consisted of speech therapists providing services to children and primary caregivers of children in need of speech therapy services. The inclusion criteria for therapists included having at least three years of speech therapy work experience before the onset of COVID-19 and holding at least a bachelor’s degree in speech therapy. The inclusion criteria for caregivers included having a child under 18 years of age with developmental speech, language and swallowing problems; their child’s participation in at least five speech therapy sessions (in-person or remote) before the onset of COVID-19 in a fixed speech therapy center in Tehran City, Iran, and the continuation of these sessions during the COVID-19 era to compare conditions; and parents’ reading and writing literacy to the extent of completing the consent form and understanding the questions.

Sampling procedure

Sampling started purposefully from speech therapists and the children’s primary caregivers and continued until reaching data saturation. To increase diversity in qualitative sampling, we selected specialists from different city districts and public and non-public centers (universities, public centers, charities, and private centers). Furthermore, for caregivers, we tried to select samples with the highest diversity in socioeconomic status, type of speech disorder, child’s age, type of therapeutic intervention, and treatment duration.

Data collection

This study collected participants’ experiences using semi-structured, in-depth interviews with speech therapists and children’s primary caregivers. The mean interview duration was about 74 min for therapists and 40 min for mothers. The central topics of the interview questions were as follows: participants’ experiences of changing the access of children and families to speech therapy services during the pandemic; the participants’ experiences of the characteristics of the child and family in their changed access to speech therapy services during the pandemic and participants’ experiences of receiving remote speech therapy services during the pandemic.

Data analysis

Findings obtained from in-depth interviews with specialists and primary caregivers were analyzed using MAXQDA software, version 2020 and the qualitative content analysis approach Graneheim and Lundman [18] Simultaneously with performing the interviews.

Trustworthiness and rigor

In Lincoln and Goba’s qualitative research, four criteria have been proposed for the trustworthiness and rigor of qualitative data: Credibility, transferability, dependability, and confirmability [19]. The research team attempted to elevate the credibility by engaging in the data for a long time and spending adequate time collecting and analyzing the data (about a year), applying various therapist-caregiver perspectives, conducting an acceptable number of interviews and reviewing data, and coding and categorizing by research team members at different stages. Regarding transferability, we increased participants’ diversity in the experience of the intended subject. Regarding dependability, all primary data collected from the interviews were carefully maintained and available at all stages; thus, it was possible to refer to the primary data several times to ensure the collection and analysis process. Moreover, meetings were held with the research team to ensure the presence of an equal and coordinated framework for data collection and analysis to ensure the research’s dependability. Ultimately, for confirmability, in addition to the precise and detailed recording of the whole work process, which made it possible to continue the process with other researchers, several interviews, codes, and categories were provided to other members of the research team, and the accuracy of these codes was checked and reviewed.

Results

Participants’ characteristics

This study interviewed 9 speech therapists and 10 mothers in Tehran City, Iran, along with the children’s primary caregivers. The participants’ information is presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Status of children’s access to speech therapy services during the COVID-19 pandemic

The current research was conducted to determine the status of children’s access to speech therapy services during the COVID-19 pandemic and the role of social factors impacting this access in Tehran City, Iran. The findings of this study consist of four main categories: reduced accessibility, intensifiers of reduced accessibility, modifiers of reduced accessibility, and consequences of reduced accessibility. The following introduces these categories, and quotes are mentioned for each category.

Reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic

As shown in Table 3, according to the participants’ perspectives, during the COVID-19 period, the delay in early specialized diagnosis, inevitable changes in the treatment plan schedule and changes in the type of treatment plan all resulted in children’s reduced accessibility to these services.

Delay in early specialized diagnosis

The participants believed that during the pandemic, as a result of the temporary closure of centers and clinics, reduced specialists’ activities, assumed unnecessary to refer to speech therapy by doctors and families because of the fear of illness, and closure of schools or remote education at schools and kindergartens, as one of the major sources of early diagnosis of children’s speech and language problems- a considerable population of children were deprived of early diagnosis.

Changes in the treatment plan schedule

According to participants’ experiences, during this period, the usual treatment plan schedule also changed, leading to reduced children’s regular access to speech therapy services. During the pandemic, the number of sessions scheduled for a child’s treatment plan decreased due to considerations concerning complying with protocols, reducing working hours in centers, increasing families’ financial problems, and their inclination to be less present in public places. Also, due to the increased interval between clients to comply with health protocols in the clinics and, thus, reduced number of daily visits, the time interval between children’s treatment sessions also extended, which was a reason for the prolonged treatment process per se. Furthermore, during the COVID-19 era, particularly in the first two years of its peak, numerous interruptions were created in the scheduled sessions. These interruptions were considerable, particularly in the initial months when most centers were closed. There were also many other reasons causing serious disruption in the access to services, such as numerous peaks of COVID-19, infection of therapists, center staff, children, or family members with COVID-19 and the necessity of passing the quarantine period.

Changes in the type of treatment plan

From the participants’ perspectives, COVID-19 and its continuous peaks in Iran gave rise to changes in the type of speech therapy services. Some interventions were restricted and abandoned, such as oral massage that required touch and close contact with the child, interventions that required removal of the face mask, or interventions that were implemented with tools that could not be disinfected. Additionally, numerous medical centers discarded group therapy. Concerning speech therapy services at home, several therapists primarily restricted these services. On the other hand, the cost of these services was raised during the COVID-19 peak, so they were mostly available only to wealthy families. Another remarkable point mentioned both by caregivers and therapists was the dependency of the treatment of children with speech disorders on social and communication interactions in normal living environments, in which children’s social interactions became restricted during the pandemic, particularly in the first year.

The following quotes from the participants are related to the reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic main category:

“Since Abolfazl got constantly sick, I could not come every day. For example, I made an interruption for one month. I could not come back here until he improved because they said that they would not work with him if he had the slightest symptoms, so I had to let him get better to be able to come here” (caretaker No. 03; the subcategory of “interruption in treatment plan sessions”);

“Some families are so busy with their affairs that they do not have any time to do anything for their children except TV, cartoons, phones, etc. If it were not for the COVID-19 period, the child would go to kindergarten and preschool centers, and since the child was included in the educational system, the kindergarten trainer noticed that the child had a problem understanding the concepts. Due to the lack of such condition, they said, ‘We did not think at all that the child has such a problem.’” (speech therapist No. 07; the subcategory of “reduced accessibility to diagnostic resources in the education system”).

Intensifiers of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 Pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in its first year, in addition to the changes that resulted in children’s reduced accessibility to speech therapy services, some factors intensified this limitation and reduced accessibility in various dimensions. These factors can be proposed in three main categories: Basic factors, factors related to in-person services, and factors related to remote services (Table 4).

Basic factors

The experiences of families and therapists in this study indicated that, on the one hand, the reduced income and, on the other hand, the increased cost of families during the COVID-19 period, specifically the increased cost of speech therapy services, led to the child’s non-continuation of treatment or non-referral for early intervention. Furthermore, compliance with health protocols (such as buying disinfectants or not using public transportation) doubled economic pressure on families. Concerning the reasons for the increased cost of speech therapy, it was suggested that given the high crowd of referrals and low compliance with health protocols in public centers, families were more inclined to private centers. Also, in this period, since home services became more challenging and transportation costs increased, the cost of home services increased. Another substantial factor was the low awareness of families regarding the golden age of development, the importance of early intervention, the necessity of speech therapy services in the pandemic conditions, and, consequently, the delay in receiving services.

Factors related to in-person services

At the level of in-person services, the intensifiers of reduced accessibility were divided into three sections: Factors related to speech therapy centers, the family and the child.

Factors related to speech therapy centers

The participants’ experiences indicated that except in the initial months of the onset of the pandemic, when most centers faced compulsory closure to control the pandemic, in the subsequent peaks of COVID-19, some private centers were temporarily closed for some time. In the initial months of the pandemic, there were problems in producing and distributing preventive equipment, including face masks and alcohol, this shortage of equipment culminated in reduced service provision. Furthermore, the change of use in the speech therapy departments in public centers to the specialized coronavirus departments or the proximity of private and public speech therapy centers to treatment centers for COVID-19 patients induced fear in families and seriously reduced their referral to speech therapy centers. Finally, during the pandemic, similar to many businesses, speech therapy centers also faced serious economic problems, resulting in the closure or displacement of many private centers.

Family’s obstacles and limitations in receiving in-person services

One of the most crucial factors that interrupted children’s access to in-person speech therapy services through referrals to centers was families’ concern about their child and their other children contracting COVID-19. This concern was higher in families who used public transportation or telephone and Internet taxis. Similarly, the families who went to Tehran medical centers from nearby villages and cities faced problems in the initial months of the pandemic because of intercity traffic restrictions. On the other hand, during the pandemic, access to relatives and nurses to care for children decreased, leading to more psychological burden, fatigue, and high responsibility of caregivers, consequently not visiting the centers. Also, before the pandemic, the simultaneous presence of caregivers in the waiting room of medical centers led to the shaping of a social support network of families. This support network was an incentive for families to continue treatment and the necessity of complying with health protocols led to the elimination or weakening of this network. At last, holding children’s school classes remotely and increasing the mother’s responsibilities were serious obstacles to mothers attending medical centers and exercising at home. In this regard, increasing the father’s role was also notable in this era. Many families reported that due to the father’s greater time of presence at home, family disputes increased due to reasons such as the father’s unemployment, disagreements about how to follow health protocols, and doubts about the efficacy of speech therapy interventions. Therefore, they encountered the father’s more serious opposition to continuing the treatment.

Child’s obstacles and limitations in receiving in-person services

According to the findings, COVID-19 prevention was the priority of families for children more vulnerable to COVID-19, such as children with cerebral palsy with a weaker immune system. For children with less severe disorders or children in the pre-language stage or at the preschool age, the family was less concerned about treatment. Thus, in significant cases, the golden age of these children was lost for timely intervention. For children with more severe mental disorders or younger children who did not understand health protocols, the family and even therapists preferred not to visit in person.

Factors related to remote services

During the pandemic, several centers and therapists provided remote speech therapy services. The participants noted that although this type of service provided access for some groups of children during the COVID-19 peak, this replacement gave rise to deprivation and reduced accessibility for other groups. In fact, for various reasons, these services were not provided by all centers and therapists or were not accepted by some families. Some of these factors are mentioned below.

Inherent limitations of remote services

From the participants’ perspectives, the child-therapist direct interaction was very important when receiving speech therapy services. In contrast, in remote services, the child-therapist immediate communication, particularly physical contact for interventions requiring touch and massage, became limited. In this regard, another obstacle was the low possibility of attracting the child’s participation and control and also controlling the conditions of the home as the treatment environment. The centers’ controlled settings and the child-therapist direct communication resulted in the child’s cooperation and the treatment’s efficacy; however, at home, the exercises were mostly not performed or performed with very low quality. Also, home conditions, including family disputes, crowdedness, the lack of private and quiet space, and the family’s skills in using remote services, affected the quality of services.

Infrastructural limitations of remote services

The presence of infrastructural limitations for remote services in Iran is a serious obstacle to the inclination of centers and the possibility of families accessing these services. Table 4 provides the details and dimensions of these infrastructural limitations of remote services from the participants’ perspectives.

Speech therapists’ obstacles and limitations in providing remote services

Speech therapists participating in this study believed that remote interventions required more time, and the possibility of professional relationship management was reduced during the pandemic. Also, given the Internet problems, the session duration for each family usually became more extended than the time of in-person sessions. Thus, speech therapists also needed to spend more time and money preparing educational content or reviewing videos sent by families than in-person sessions. Another obstacle was the unexpected and sudden conditions of COVID-19, which sometimes culminated in the sudden replacement of in-person services with remote services. At the same time, the therapists were not adequately prepared for these conditions. Most had low knowledge and skills to work with online network platforms, specialized speech therapy programs, principles and practices of providing remote services, and how to produce and disseminate educational content.

Family’s obstacles and limitations in receiving remote services

In this period, some families did not accept these remote services as a specialized intervention. One of the serious obstacles was the problems of access to speech therapy tools and appropriate facilities for remote communication due to the high cost of the Internet and holding school classes as remote and consequently, the need for concurrent access to multiple appropriate devices. Finally, the family’s low awareness and skills for effective implementation of interventions at home caused specialized speech therapy services not to be as effective as expected. Low knowledge and abilities were considerable in various dimensions, including low skills in working with electronic tools, applications, and software, low skills in the way of communicating with the child and attracting their cooperation and low skills and accuracy of the therapist in transferring the training and intervention to the child, leading not only to the child not progressing but also to increase their problems.

Child’s obstacles and limitations in receiving remote services

Children in need of oral massage and contact interventions, particularly those with swallowing disorders, and children who lack the cognitive ability to use communication media or lack the required communication and interaction ability due to their young age or the type of disorder did not have the opportunity to use remote services completely. Thus, according to the participants’ experiences, the service provision for some children was limited to education and counseling to the caregiver.

The following quotes from the participants are related to the “intensifiers of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic” main category:

“In any case, subjects whose jobs have been somehow affected by COVID-19, for example, taxi drivers or jobs of this type, their economic status was so affected that speech therapy services were no longer their primary priorities” (caregiver No. 09; the subcategory of “increased family economic challenges”);

“My husband was at home and did not let me do this. Nafiseh was crying; she did not cooperate to perform the exercises. My husband said, ‘Let her go; now it is not the time for this.’ He was working at home all day. My job was to do exercises when my husband was not around” (caregiver No. 08; the subcategory of “reduced possibility of family participation in the treatment process”);

“I mean, we should be taught. Why did we suffer so much? Because we did not know. I did not know how to use WhatsApp. I learned a lot by trial and error how to make a plan, how to communicate” (speech therapist No. 01; the subcategory of “low preparation, knowledge, and skills to provide remote services”).

Modifiers of reduced accessibility during the COVID-19 pandemic