Volume 25 - Special Issue

jrehab 2024, 25 - Special Issue: 576-603 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Vameghi M, Jorjoran Shushtari Z, Takaffoli M, Bahrami G, Setareh Forouzan A. Investigating the Requirements for Integration of the Social Determinants of Health Approach in Rehabilitation Education: A Qualitative Study in Iran. jrehab 2024; 25 (S3) :576-603

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3421-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3421-en.html

Meroe Vameghi1

, Zahra Jorjoran Shushtari2

, Zahra Jorjoran Shushtari2

, Marzieh Takaffoli *3

, Marzieh Takaffoli *3

, Giti Bahrami4

, Giti Bahrami4

, Ameneh Setareh Forouzan5

, Ameneh Setareh Forouzan5

, Zahra Jorjoran Shushtari2

, Zahra Jorjoran Shushtari2

, Marzieh Takaffoli *3

, Marzieh Takaffoli *3

, Giti Bahrami4

, Giti Bahrami4

, Ameneh Setareh Forouzan5

, Ameneh Setareh Forouzan5

1- Social Welfare Management Research Center, Social Health Research Institute, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Social Health Research Institute, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,marzieh.takaffoli@gmail.com

4- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

5- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Social Health Research Institute, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

4- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Alborz University of Medical Sciences, Karaj, Iran.

5- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 2709 kb]

(695 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5367 Views)

Full-Text: (862 Views)

Introduction

Social accountability is crucial to medical education and health profession programs, as they are held responsible for their actions and impact on the public [1-4]. Regarding social accountability, the medical profession has specific responsibilities and privileges bestowed upon them by society [5]. In 1995, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined the social accountability of medical schools as the obligation to direct their education, research, and service activities toward addressing the priority health concerns of the community, region and/or nation they serve [1]. These obligations are reinforced through various means, such as legislation, regulation, and accreditation. This means placing the responsibility on medical schools to produce capable students who can effectively address the community’s needs [6]. Social accountability encompasses the enduring social contract between the medical field and society [6, 7, 8]. Furthermore, the role of universities in social accountability and sustainable development has been indicated. When higher education institutions develop an integral, socially responsible collaboration with the broader community, opportunities are created for unique epistemic advances for the stakeholders involved [9]. Considering the importance of social accountability in medical education, an increasing body of evidence emphasized the vital and prior role of social determinants of health (SDH) in this regard [1, 10].

WHO [11] defines SDH as the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems. Notable evidence emphasizes that the role of SDH is imperative in promoting social accountability in medical schools, enhancing collaboration between sectors in the health domain, implementing evidence-based interventions, and substantially reducing health inequalities and improving health outcomes [12]. Although addressing the SDH requires a broad range of actions that involve the collaboration of multiple sectors (e.g. education, justice, and employment) and different levels of government, healthcare workers at the front of clinical care are nonetheless important players and potential catalysts of change [13, 14]. In this regard, Andermann [14] posits that clinicians can address social determinants in their clinical practice through three levels, including the patient level (e.g. asking patients about social challenges in a sensitive way), the practice level (e.g. ensuring that care is accessible to those most in need), and at the community level (e.g. physicians can advocate for more supportive environments for health). These practices and actions require specific knowledge and skills that universities should address. On the other hand, with demographic changes, shifts in the patterns of diseases, injuries and disorders and increased public awareness and societal expectations for quality specialized services, the need for revised educational programs emphasizing SDH has become more apparent [15]. Hence, by providing students with opportunities to develop a more robust SDH and health equity model, it is ensured that the next generation of physicians is providing better care for the most vulnerable target group [16].

Furthermore, the challenges in addressing SDH within medical education include inadequate planning, an insufficient emphasis on social responsibility, and a tendency to neglect environmental factors [12, 17]. Studies reveal that to overcome these challenges, medical schools and residency programs are successfully incorporating educational approaches and models that focus on SDH, such as participatory and community-based approaches [18 -21], collaborative learning approaches [22, 23], transformative learning [20, 24-26], service-based learning [12, 17, 20, 25-27] and experiential learning [16, 28, 29]. Moreover, there are some pieces of evidence that to integrate SDH in medical education, the educational content should focus on community engagement, identification of local contexts, health policies, support-oriented education and student skills development. It should teach students to consider population diversity and leadership [30].

In Iran, addressing social accountability has been paid considerable attention to in policies related to medical education in recent years, which is defined as one of the main goals of the medical education system in Iran [31]. Additionally, the committee of accountable and justice-oriented education specifies operational plans and actions to fulfill its objectives, including revising and developing educational curriculums and monitoring them in terms of social accountability and responsiveness to the needs of the target population and making students and academic staff alert and knowledgeable about SDH in their practices [32].

As noted, integrating SDH into medical education has gained increasing attention internationally, with studies focusing on curriculum development and review [33-35]. Meanwhile, in Iran, different medical universities’ considerations for social accountability, their challenges [36, 37] and developing tools or exploring necessities for revising curricula to fulfill its goal have been studied [15, 38, 39] as research reveals the lack of attention in the current medical education of Iranian medical students [15, 36, 37].

As mentioned, while some studies have examined social accountability in medical education in Iran, no studies have deeply focused on SDH specifically for rehabilitation sciences. Moreover, no comprehensive tools exist for national-level development of SDH for medical education. On the other hand, the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences has made significant contributions to the development of rehabilitation in Iran since its responsibility and mission in this term. The first step to integrating SDH into medical education is to clarify its educational needs and requirements.

Accordingly, this study identifies the requirements from the point of view of rehabilitation education beneficiaries, including students, faculty members, and non-governmental organizations. By addressing this research gap, we can contribute to developing evidence-based interventions and enhancing social accountability in medical education, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes and reduced health inequalities.

Materials and Methods

The research paradigm employed in this study was qualitative and conducted using conventional content analysis. The study occurred in 2022 at the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Health. Various aspects of actions leading to social accountability were examined based on a review of relevant sources regarding medical universities’ social accountability. Among these aspects, the SDH approach was selected as the primary focus of the study, considering its higher feasibility for implementation within universities.

Study participants

The study population consisted of students and academic faculty members from three departments: Physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy at the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Health. Additionally, members of non-governmental organizations affiliated with rehabilitation and an external rehabilitation specialist were included in the study.

Participant’s selection method

The sampling method employed in this study was purposive. Academic faculty members needed at least three years of clinical experience in rehabilitation. Enrolling in a doctoral program in one of the three disciplines was required for students. Non-governmental and charitable organization members were included if they possessed at least three years of direct work experience with rehabilitation clients. All academic faculty members from the three educational departments were invited to group discussions. From the Physiotherapy Department, 4 participants were involved. From the Occupational Therapy Department, 6 participants were invited, and from the Speech Therapy Department, 8 participants contributed to group discussions relevant to their respective fields. Eight doctoral students from three disciplines and seven managers and experts from non-governmental organizations representing four institutions participated in group discussions. Four non-governmental organizations in the rehabilitation domain were chosen, considering diversity within the covered groups (age groups, types of disabilities and services provided). These organizations were selected based on their accessibility to Tehran and Karaj. Managers and experts of these organizations who met the study’s entry criteria were invited to participate.

Data collection method

Data collection in this study was carried out through focused group discussions with various participants, guided by the criteria for reaching data saturation. Data saturation was achieved through three separate group discussions with academic faculty members from each department. One was with students from all three disciplines, and one was with members of non-governmental organizations. All group discussions were conducted in person, except for the one with students, which was held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A semi-structured questionnaire was used for data collection, consisting of open-ended questions prepared based on reviewing relevant sources and study objectives. These questions were reviewed and refined based on simultaneous data collection and analysis for subsequent group discussion sessions. The main themes of the questionnaire included participants’ experiences regarding the role of SDH in their professional services, the necessary education for students in rehabilitation fields to acquire knowledge and essential intervention skills and the changes and improvements in attitudes related to SDH. Additionally, the features of the educational environment that allowed students to better understand and acquire skills in addressing SDH were explored. The average duration of each session was approximately 3 hours, and with participants’ permission, all group discussion sessions were fully recorded. After the conclusion of each group discussion session, its content was immediately implemented and analyzed to guide subsequent sessions. The results from the group discussions were categorized into the main category: requirements of integrating the SDH approach into rehabilitation education. To re-examine the collected information, the results of the group discussions were shared with six key informants in the rehabilitation field. Three of these informants had previously participated in group discussions, while the others had not. Their input aimed to provide corrective and complementary perspectives. Subsequently, in a session attended by 3 of these key informants, their opinions were revisited and finalized.

Data analysis

The Elo and Kyngäs [40] process was utilized for the qualitative content analysis of group discussion data. To enhance the study’s credibility and accuracy, analyses were conducted using the MAXQDA software, version 2018. Immediately after each group discussion session, its content was entered into the software. Text segments containing content relevant to the study objectives were initially identified and coded as semantic units during textual analysis. These initial codes were then listed. Duplicate or synonymous codes were merged, and initial codes that shared similar semantic content or indicated similar events were combined to form preliminary concepts. At a higher level of abstraction, these concepts formed categories. As additional group discussion sessions were added and data analysis progressed, each semantic unit identified in the textual material or each code or concept generated was compared with other codes or concepts. A new initial code was created if there was no conceptual similarity to other existing concepts or codes. If there was a similarity, the new concept was added to the current code to enrich its meaning. Categories were also formed based on their relationships at different classification levels, comprising both main and subcategories.

Trustworthiness or rigor

This study considered four criteria of Lincoln and Guba [41] for the study’s trustworthiness. The researchers tried to ensure credibility by long-term engagement with data, spending enough time to collect and analyze data, having many interviewees (33 interviews), member checking, and peer debriefing. For transferability in the selection of the participants, the high diversity of their experience from different groups of students, academic faculty members, and members of non-governmental organizations was considered. To improve dependability, meetings were held with the research team to discuss the data collection and analysis process and to determine a uniform and coordinated framework for it. To achieve confirmability, all stages of the research, especially data analysis, were recorded in detail and accurately; also, several interviews, codes, and categories extracted were provided to the research team to review and evaluate.

Results

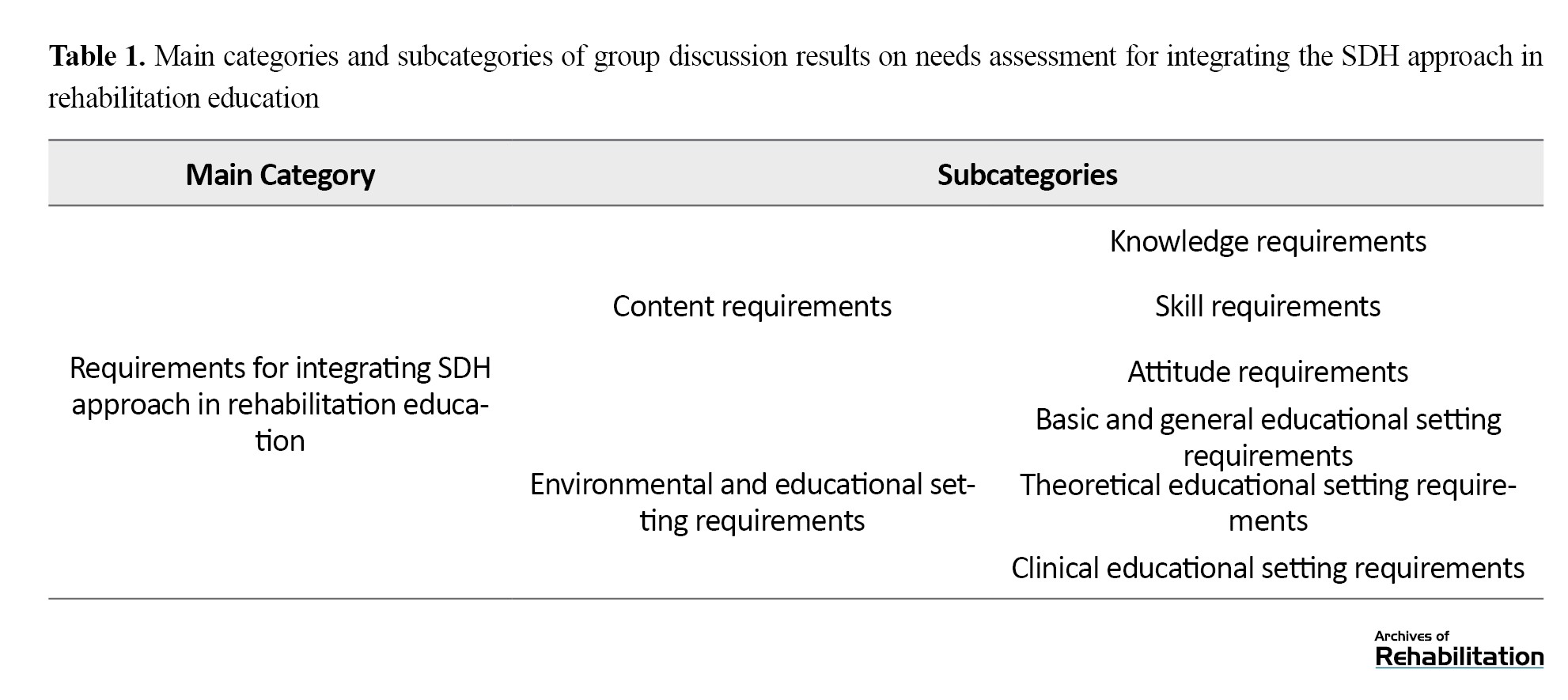

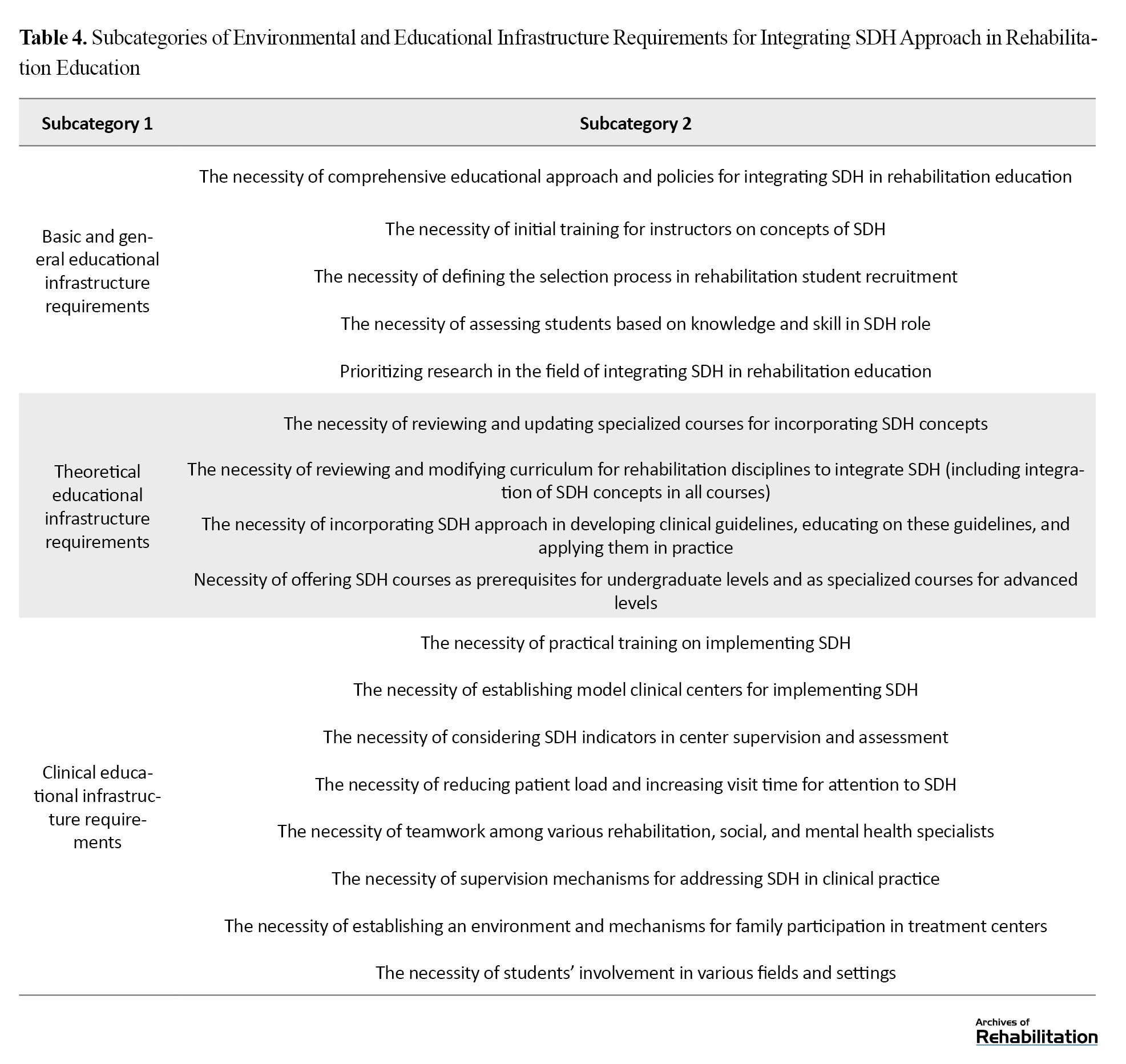

The results of the study revealed the main requirements for integrating the SDH approach into rehabilitation education. The main category was divided into two subcategories: educational content requirements and educational environment and setting requirements (Table 1).

The participants of the current study believed that to integrate the SDH approach into rehabilitation education, requirements must be considered not only in the theoretical and practical educational content of rehabilitation disciplines but also in the environment and academic settings, especially in clinical training.

Educational content requirements

Based on the findings of the current study, the necessary educational content to be taught to students in the field of rehabilitation was divided into three subcategories: knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

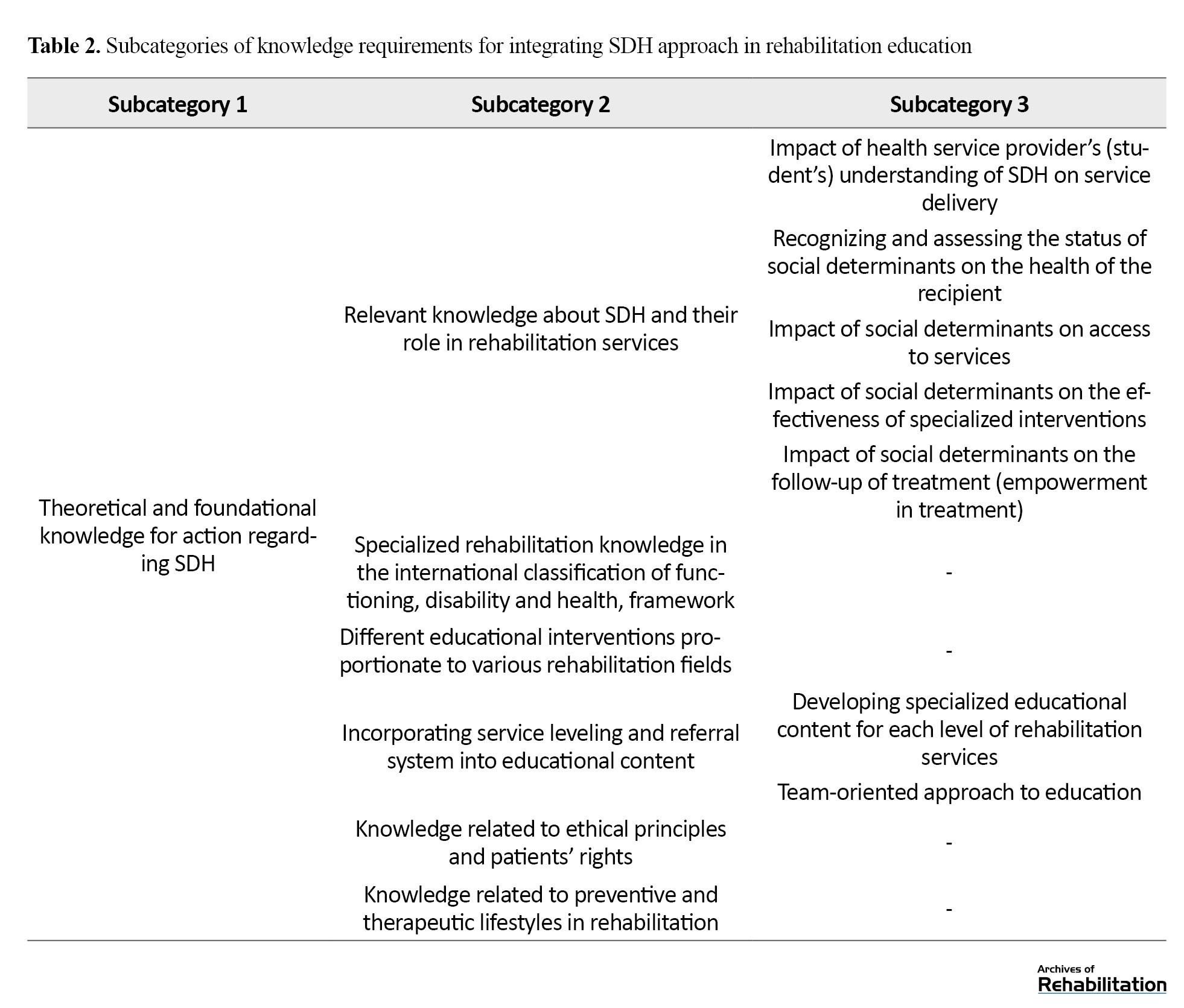

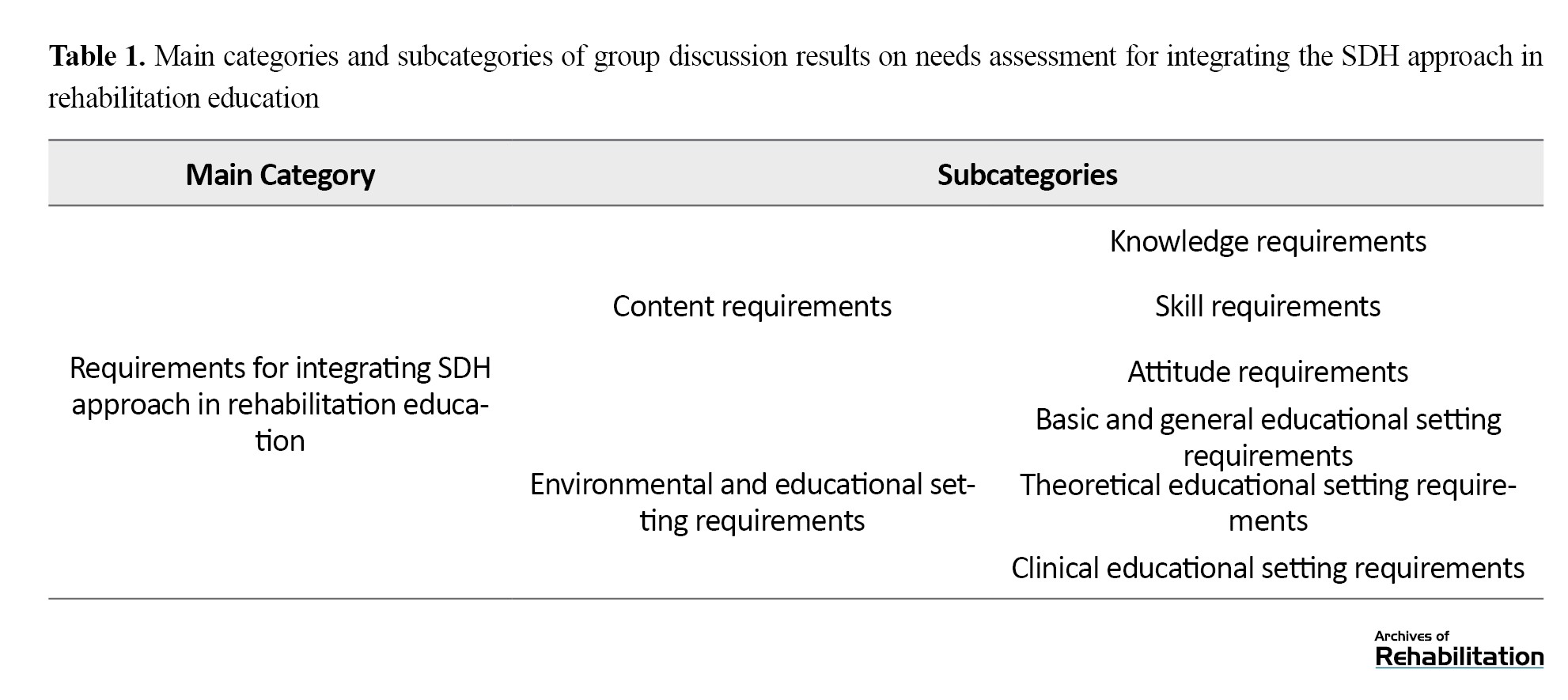

Knowledge Requirements

According to participants’ views, rehabilitation students should possess sufficient knowledge to recognize the role of SDH. The most important areas of this knowledge are highlighted below (Table 2).

The participants emphasized students’ need to learn about SDH and their role in rehabilitation services including access to services, rehabilitation intervention effectiveness, and compliance with treatment. Experiences of faculty members, students, and representatives from non-governmental organizations, indicated that various social factors, such as gender, ethnicity, language, education, awareness of patients and their families, and cultural norms and values, such as social stigma play a significant role in patients’ access to rehabilitation services.

“There are many times when people are afraid of social stigma. She brings her child about two years, stating that her family is unaware of her situation and she comes sneakily so as not to stigmatize her child” (speech therapist).

Additionally, economic status and access to financial support resources significantly impact health status. Rehabilitation education should provide the necessary knowledge in this area.

“A person with acute back pain who does not work for a week and has no work problems is less likely to get chronic back pain and this has been proven, so social issues have a great deal of influence” (physiotherapist).

the participants of this study emphasized the significance of concepts related to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health framework, such as a comprehensive definition and holistic view of health and disability, the role of environmental and social factors in individuals’ functioning and participation, and rehabilitation within the social and family context. They considered this perspective in alignment with the SDH approach. However, they believe the concept needs to be developed and receive more attention in education.

Additionally, the participants emphasized education of preventive and therapeutic lifestyle-related knowledge within the rehabilitation domain. According to their viewpoint, therapists need to know various preventive and therapeutic methods and patterns and plan interventions tailored to patients’ personal and social contexts. Moreover, in integrating SDH into the rehabilitation education program, it is essential to consider service categorization, patient referral systems, and service differentiation based on prevention levels.

“Physical activity is a sub-branch of lifestyle; that is, if we truly want to consider lifestyle, it is closely related to our social issues” (physiotherapist).

There was also a strong emphasis among many participants on the necessity of increasing knowledge about ethical principles and patients’ rights:

“A student should also be trained to understand his role as an occupational therapist within the health care system. Some people are making progress in private family matters. Are you legally permitted to speak? Are you allowed to evaluate? Where can you work” (occupational therapist).

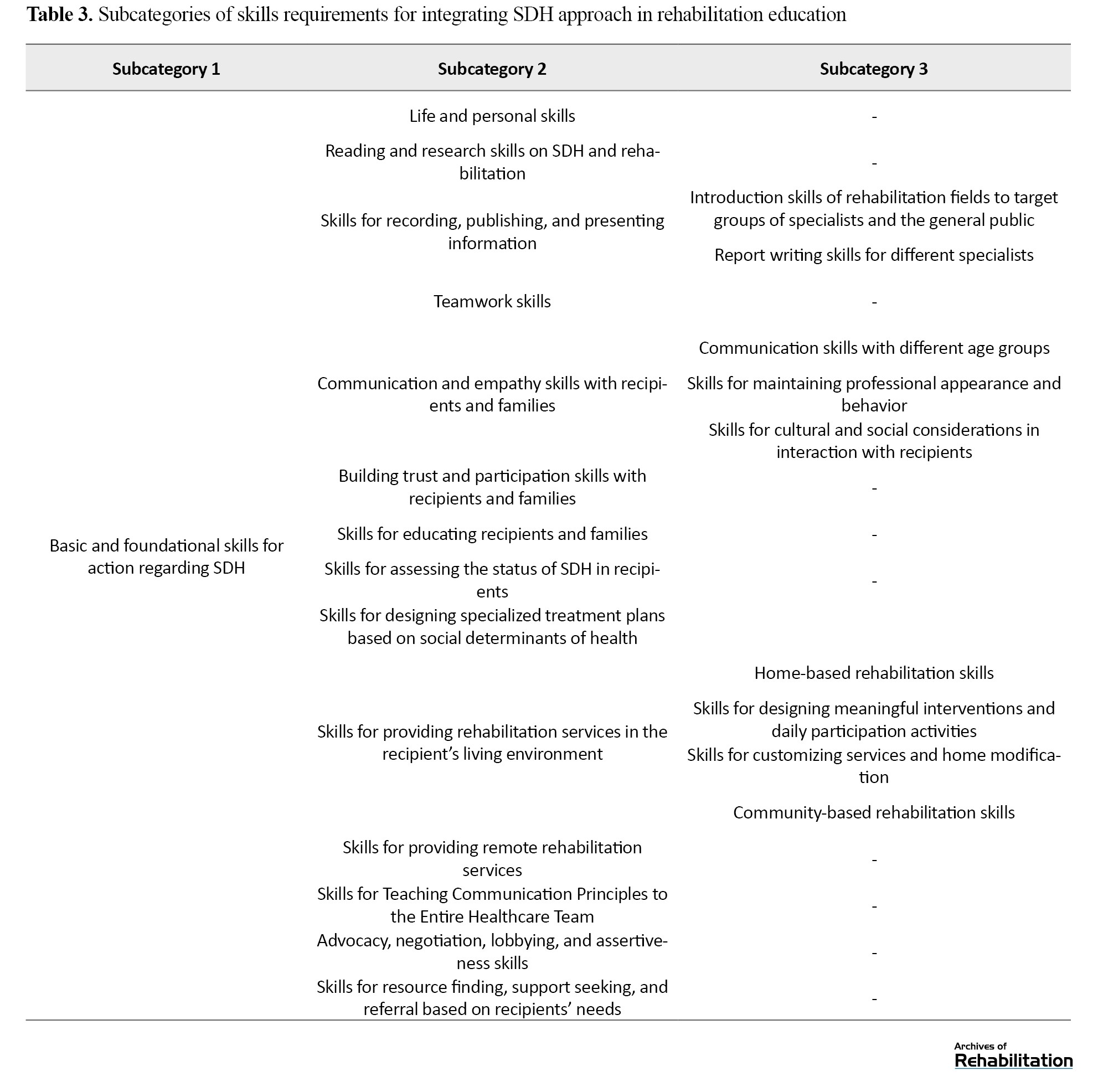

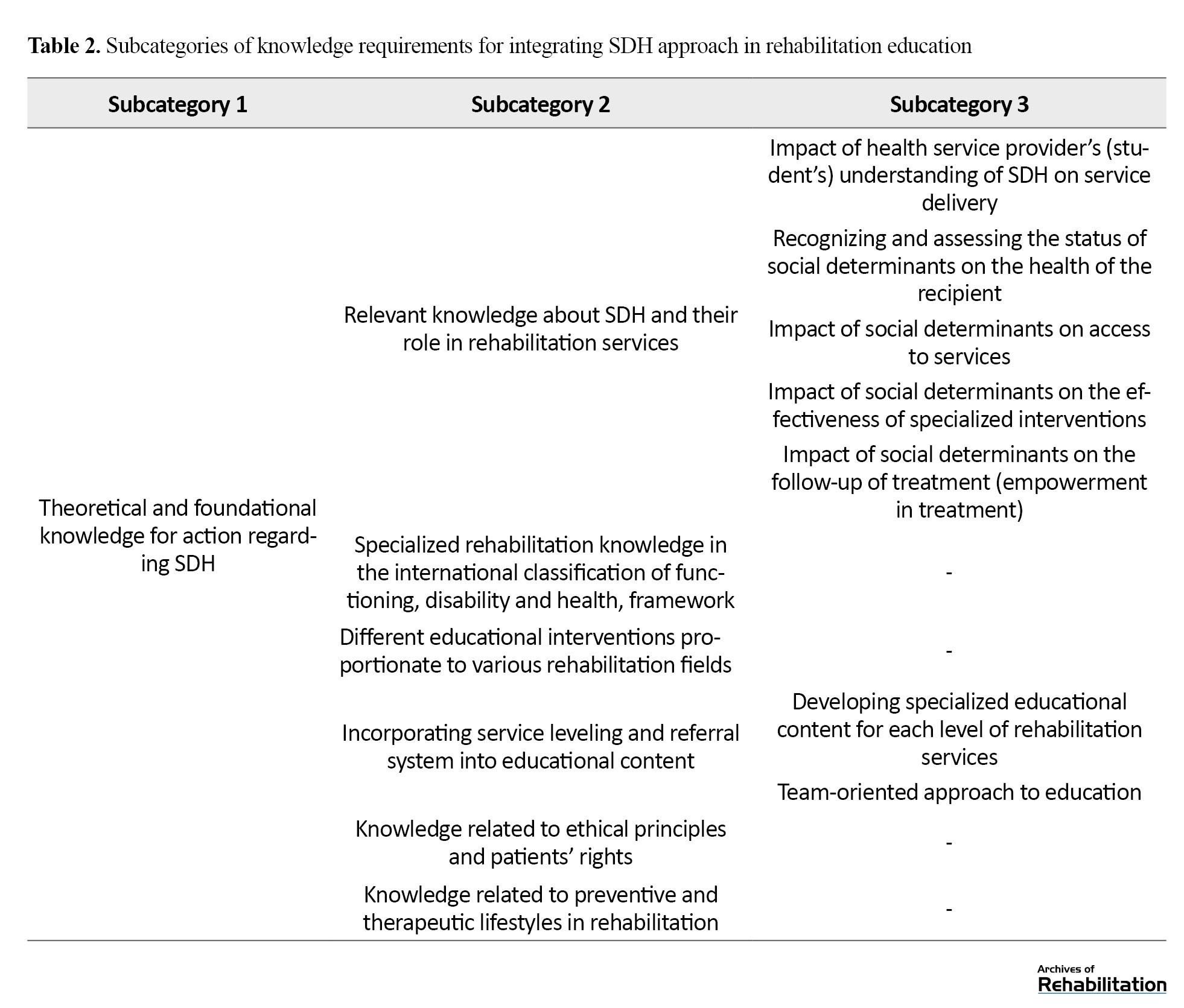

Skill requirements

Table 3 illustrates the skill requirements for integrating SDH into rehabilitation education and its subcategories based on the study findings.

According to the participants of this study, within university rehabilitation education, acquiring individual skills and life skills, including self-awareness, self-confidence, self-esteem, anger management and assertiveness, is crucial. These skills are necessary for team-based collaborations among students, cooperation with other specialists, and working with families dealing with various and severe impairments. In addition, they are essential to prevent the negative impact of personal and social situations of service providers on their performance. Also, in addition to specialized skills, students and therapists should learn communication and empathy skills for clients and families. They should learn skills to build trust and engage service users and their families. Complete trust and collaboration are achieved when service users and their families actively participate in treatment. Moreover, therapists should be culturally and socially sensitive and learn how to establish connections with various age groups, especially children and older people.

“For some speech disorders, family conditions can be very effective, for example, what are your child’s conditions, what environment he is in, how stressful it is, and I believe that increasing this skill in students can be very beneficial” (speech therapist).

Based on the study findings and considering the multidimensional approach of SDH, teamwork-related skills are also necessary.

“The majority of people who come to us usually have several deficiencies together, such as aphasia clients need SLP and occupational therapy, as well as physiotherapy. The interaction between these different therapists can prove useful” (student).

When facing patients, students should be able to assess various aspects of social determinants in them. They should also be able to create a patient profile that considers these factors within different cultural and social contexts. Besides, to ensure a comprehensive understanding of social determinants, periodic assessments should be conducted. Another skill requirement is the ability to formulate specialized treatment plans based on SDH. Students must be educated in providing interventions that align with these factors and existing social capacities after a thorough evaluation.

“As an occupational therapist, I am confident this method is appropriate for treating the patient. However, he does not have access to a toilet, so we have to inquire whether he can use the toilet. In this course, the student should be able to assess how these factors should be evaluated” (occupational therapist).

Considering the participants’ perspectives, there is currently insufficient knowledge and evidence of the impact of social determinants in rehabilitation. This underscores the necessity of acquiring skills in various quantitative and qualitative research methods and disseminating results. Additionally, rehabilitation specialists play a crucial role in interacting with rehabilitation organizations and advocating for the rights and rehabilitation needs of different societal groups. They should learn and employ advocacy, lobbying, and negotiation skills to enact necessary reforms and realize individuals’ rights, utilizing available capacities to benefit patients and their families.

“I intend to dedicate part of the training, whether in the clinic or student training, to finding charities because a therapist’s relationship with a charity is much more effective than the individual direct expression of the problem” (speech therapist).

Attitude requirements

The participants strongly emphasized the necessity of applying knowledge and skills related to SDH with a comprehensive and holistic perspective toward service users as individuals with various physical, psychological, social, family and spiritual dimensions.

“Our only definition is that of the WHO, which does not specify health as a state of welfare, but rather a state of well-being. In other words, health is not only the absence of disease and disability, but also a state of well-being and a healthy physical, mental and social condition” (NGO).

According to the participants, given the numerous operational challenges in providing rehabilitation services, confidence can only be gained by educating and institutionalizing ethical, fair, and rights-based approaches toward patients and their families. This ensures that students will provide adequate services toward justice in healthcare in the future. Rehabilitation specialists must also adopt a holistic and systemic approach to the healthcare system. This involves considering health services within an integrated and interconnected framework that covers patients’ diverse and comprehensive needs. The new approaches to rehabilitation all focus on empowering individuals with disabilities and those in need of rehabilitation services which emphasizes the necessity of creating suitable platforms for their participation and involvement in society. From the participants’ viewpoint, rehabilitation specialists should recognize that their service users extend beyond those who physically visit specialized rehabilitation centers. With a community-based rehabilitation approach, it is crucial to tailor specialized services based on available resources and collaboration with the local community to ensure accessibility and utilization.

“There are several problems you have listed under the heading of social issues, including access, income, and awareness. All of these factors have made it difficult for many people to access these services. Instead of bringing people to clinics, hospitals, or centers, let’s send specialists to the community to offer services” (occupational therapist).

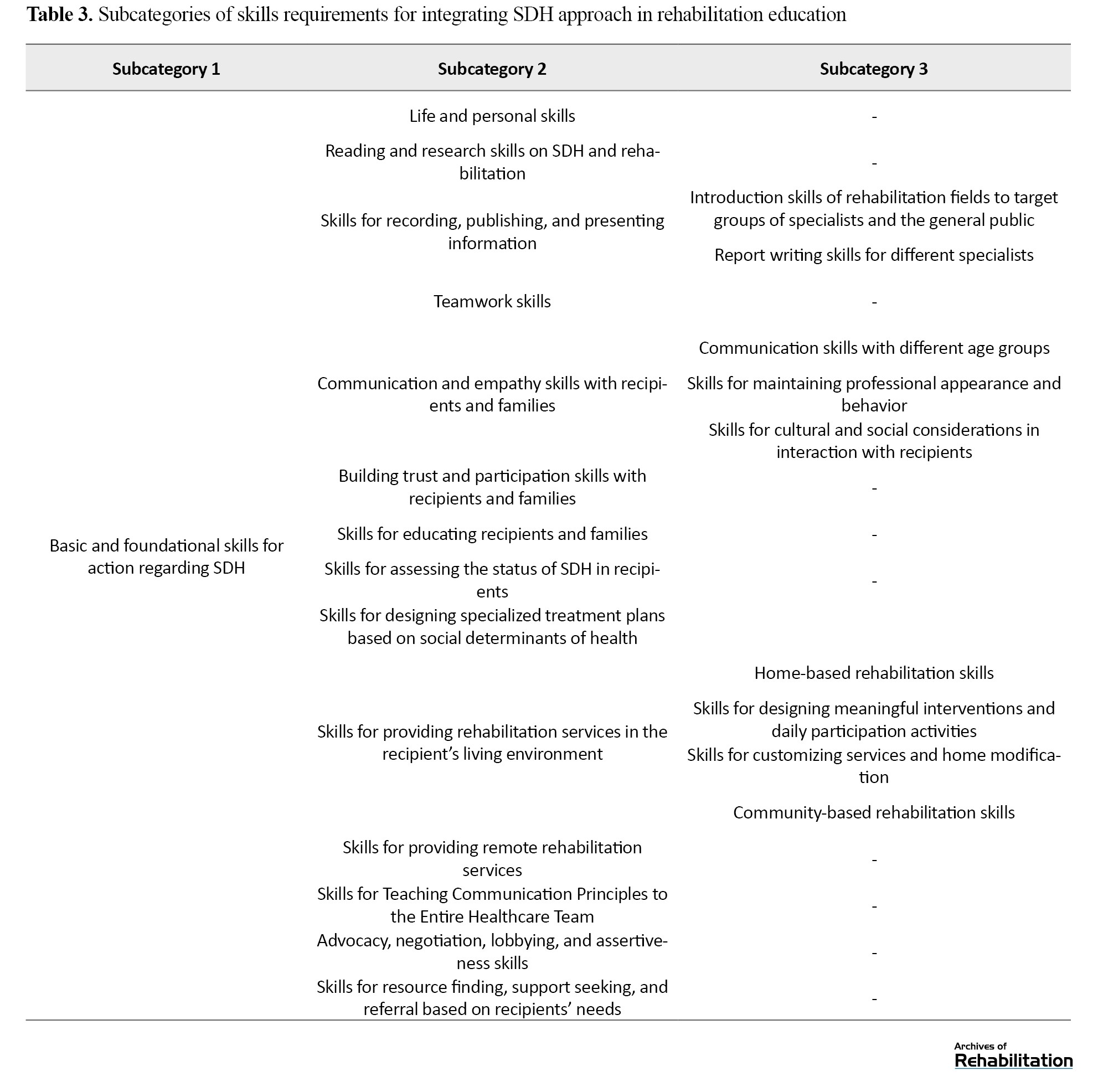

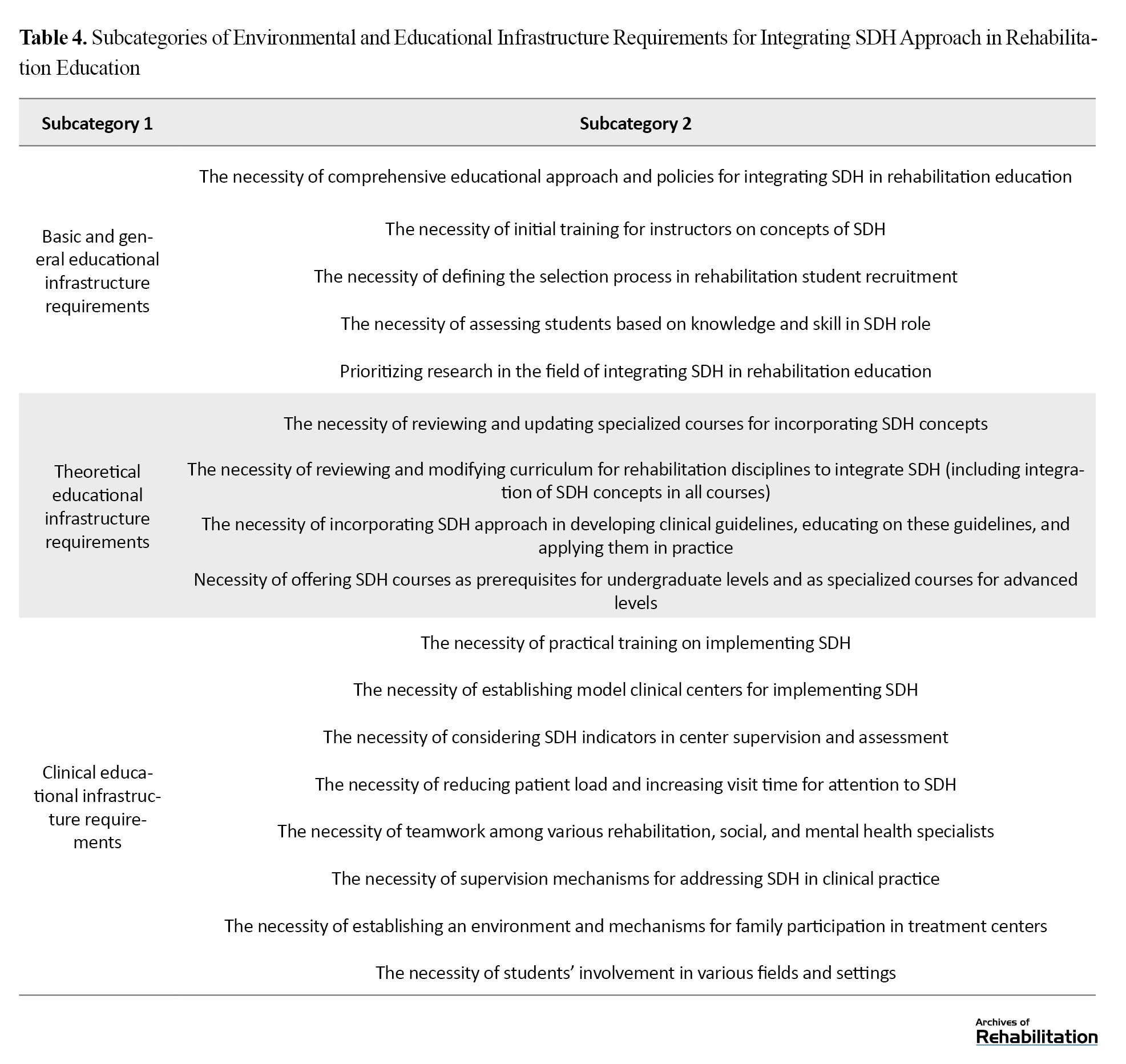

Educational environment and setting requirements

Based on the study findings, the theoretical and clinical educational environment must possess specific conditions and characteristics to integrate the SDH approach into rehabilitation education. These requirements were categorized into three subcategories: basic and general requirements of the educational setting, theoretical educational setting requirements, and clinical educational setting requirements (Table 4).

Basic and general environmental and educational setting requirements

The participants pointed out that one of the fundamental and general requirements of the educational setting is to train faculty members in rehabilitation fields in the concepts of SDH and how to act at different levels with this perspective. This ensures that these teachings can be effectively conveyed to students. Additionally, theoretical and clinical teachings will effectively achieve the necessary impact when theoretical and clinical knowledge and skills related to SDH are assessed and evaluated among students.

Theoretical educational setting requirements

The participants believe that, besides revising all current syllabi and courses based on updated and scientifically relevant resources related to SDH, there should also be coherence and coordination regarding these concepts across all applicable courses. This approach ensures that the necessity of these concepts is reiterated in various courses and students develop a comprehensive perspective on the topic. One of the significant educational resources in rehabilitation is guidelines and clinical manuals, which serve as the basis for students’ practical actions in service-provided centers. SDH educational content must be incorporated into these guidelines and clinical manuals. Another requirement highlighted by participants was the need for tailoring academic courses and materials related to SDH according to different educational levels:

“A course on SDH can be helpful at the undergraduate level, where students are more involved in internships and practical courses, to increase students’ knowledge and change their attitudes regarding health determinants. However, at higher levels, this training should be part of supplementary and specialized courses” (physiotherapist).

Clinical educational setting requirements

This study indicates that rehabilitation students’ clinical training should also possess specific conditions and characteristics alongside the requirements for preparing the theoretical educational setting. In this context, some participants emphasized that practical training can illustrate the practicality of theoretical courses related to SDH for students. This will enhance their learning motivation and education effectiveness:

“If SDH is included in the educational curriculum, but students are unaware of their practical value, and how it can benefit their work, they may not show interest” (physiotherapist).

According to the study participants, one of the requirements is the establishment of exemplary rehabilitation centers that apply the SDH approach. In this regard, the participants maintained that for students to be able to apply the knowledge and skills they have been taught in rehabilitation actions during and after their education, universities should provide real-life examples of rehabilitation centers that have operationalized the SDH approach. Students should receive training in such environments to gain practical experience.

“As an example, if I were a student and went to a central facility for clinical observation, it must have a social worker, a professor trying to acquire a sports area from, for example, the municipality, for the patients, sending the students to obtain the land. This is the facility serving as an ideal” (NGO).

Moreover, the participants believed that due to the high volume of patients, very limited time is allocated to each patient. This limits the possibility for students and therapists to assess and intervene within the framework of SDH during clinical placements. Therefore, they emphasized reducing service users and increasing visit time to focus on SDH.

Based on the participants’ perspectives in this study, a collaborative and holistic approach to SDH can only be fully implemented within university healthcare centers and students can operationalize the learned teachings when a collaborative environment is established among various rehabilitation and social and mental health experts, especially social workers and psychologists. These professionals should interact with each other and provide comprehensive and coordinated services to clients. Furthermore, participants stressed that all professionals working as a team in healthcare centers should receive education on the SDH. This will ensure a harmonized approach and performance in this area.

“Finally, if the children [students] can obtain a consultation from a psychologist, social worker, psychiatrist, and physiotherapist to implement the teamwork they study, this will be very beneficial” (physiotherapist).

The participants believe supervisory mechanisms should be in place throughout clinical training to ensure attention to SDH during clinical practice. This should involve trained supervisors working alongside students to provide necessary supervision, support, and guidance when needed.

The findings indicate that despite the significant role of family participation in integrating SDH into education, the conditions and service delivery methods in healthcare centers are not always conducive to family involvement and participation in the rehabilitation process. Therefore, as the participants emphasized, an environment that encourages and facilitates the presence and participation of families in healthcare centers is needed.

“During our bachelor’s clinical training, we did not interact much with families; they waited outside. Now, with those who have graduated, I often see that families are not present during therapy sessions. They sit outside and do not know what is happening inside the therapy session” (speech therapist).

The necessity of students’ presence in diverse fields and different contexts has been highlighted as one of the requirements for clinical education. This is because participants believe that students can apply theoretical and practical teachings on SDH when they are exposed to service users from diverse social backgrounds and encounter various social factors in different educational settings. This exposure will enable them to operationalize their learned knowledge and skills.

“We need to provide conditions for our students (because this is a gap in our job) that encourage them to have more presence, especially occupational therapy students, in schools. I know speech therapy has this presence. There was also a period when technical orthopedics were present in schools, examining proper footwear and insoles” (occupational therapist).

Finally, according to the participants’ perspective, one factor that could lead institutions where students undergo clinical training to pay attention to SDH and provide an operationalized educational environment for students is establishing a monitoring and evaluation system of institutions that focuses on social determinants of health.

Discussion

Addressing the SDH in providing rehabilitation services requires a wide range of actions and collaboration among various sectors, including education, welfare, and employment at local, provincial, and governmental levels. Frontline health service providers play a crucial role in achieving this goal. However, they must be well educated about the impact of social determinants on community health outcomes and how to address these in practice. This study aimed to explore the educational needs and requirements for integrating SDH into Rehabilitation Sciences education at an academic level. According to our knowledge, this is the first study focusing on understanding the educational needs of specialized rehabilitation service providers concerning SDH. This study emphasizes developing social accountability skills and considering SDH in the service delivery process. This study reviewed rehabilitation education programs in selected fields, including speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy. The study’s findings were categorized according to the requirements for integrating the SDH approach into rehabilitation sciences education.

The study’s findings reveal that rehabilitation students must have a comprehensive understanding of SDH. Many participants acknowledged the importance of recognizing the impact of social factors such as gender, ethnicity, language, education, and cultural norms on patients’ access to rehabilitation services.

The participants shared some of their lived experiences regarding the significant role of economic factors on patients’ health outcomes and referenced scenarios where financial stability impacted recovery from conditions like acute back pain. This finding is supported by studies, demonstrating that economic hardship can exacerbate health conditions and limit access to necessary healthcare [42]. In this regard, it is indicated that incorporating SDH into healthcare education can significantly enhance students’ ability to address health inequities. They argue that education programs should impart knowledge and foster critical thinking skills that enable students to apply it in real-world settings [43]. This finding highlighted the importance of understanding the role of economic status and access to financial support on patients’ health outcomes by students who study rehabilitation sciences in academia.

Despite the participants’ agreement on the importance of SDH’s impact on service provision and clients, applying these factors requires a complex and intertwined set of requirements at different levels. Therefore, discussing SDH at the university level requires a comprehensive approach and changes in the content and setting of education. Most of the participants believed that students should possess sufficient knowledge of SDH to integrate these concepts into rehabilitation education. Hence, it was recommended to develop new curriculums, revise existing ones, and change teaching methods and evaluation approaches that can be used to guide rehabilitation educators. These findings are aligned with other studies [28, 36]. Moreover, in line with Moffett, Shahidi [33], provision of an SDH curriculum and integration of that into a core emergency medicine clerkship, our findings place the highest emphasis on practical education of these concepts in a clinical context. Some participants expressed that providing theoretical education about SDH to students without teaching these concepts practically to patients and without converting them into practical skills would render such education ineffective.

Alongside other studies [44, 45], our results revealed that educating students majoring in Rehabilitation Sciences about SDH not only acquaints them with the role of social determinants in various health outcomes but also equips them with the capability to take action and intervene at different levels, including the patient, practice, and community levels. Moreover, it instills in them the mindset that, armed with knowledge of SDH and skills such as advocacy, lobbying, negotiation, and most importantly, interdisciplinary and intersectoral collaboration, they can effectively work towards improving the health of the individuals and community and reducing health inequalities. Therefore, it is suggested that integrating SDH should be considered alongside theoretical and foundational teachings, and clinical education should focus on designing educational intervention packages.

In this regard, the development of a framework for integrating SDH into the educational program of rehabilitation sciences in academia should include three main areas: education, collaboration with the community, and ensuring alignment of policies and responsibilities for all beneficiaries [46]. A curriculum focused on developing social accountability in rehabilitation professionals requires innovative, collaborative, and transformative educational approaches. As recommended in similar studies [10], initial discussions for developing or revising educational curricula should focus on how the curriculum can best create opportunities for social awareness and responsibility.

From the participants’ perspective, many concepts related to SDH have been applied in the current rehabilitation curriculum, specifically the international classification of functioning, disability and health framework. this perspective is echoed in the work of Cieza and Stucki [47], who advocate for the international classification of functioning, disability and health as a comprehensive model that can enhance the delivery of rehabilitation services by addressing individual and societal factors. However, participants believed these concepts do not transform into actual actions and change due to the lack of an appropriate setting and motivation. Furthermore, the necessity for a proper educational setting, such as qualified faculty members and supervisors, necessary facilities, and a teamwork atmosphere, was highlighted as essential for effective education.

Besides, participants stated that the rehabilitation education system in universities should adopt cohesive policies based on SDH, including developing appropriate content, providing educational platforms within families and communities, facilitating family involvement and participation in clinical settings and implementing suitable supervision and evaluation. These findings are consistent with key observations indicating that a health education system at the postgraduate level requires socially accountable assessment to ensure that learning emphasizes necessary competencies and that graduates possess the desired attributes [39].

Another finding of the present study was the necessity of educating educators and service users. Educators familiar with the concepts and importance of SDH in healthcare can vividly explain the impact of these factors on individuals’ health during different rehabilitation courses. This finding aligns with a study conducted at Qazvin University of Medical Sciences [48], which emphasized the training of academic educators through periodic workshops in integrating SDH into medical education.

According to the participants’ perspectives in the current study, service users must also become acquainted with SDH and its effects. This knowledge can effectively prevent disabilities and health problems. It can also familiarize them with the importance of service providers considering social determinants during screening and service delivery, improve the interaction between service users and providers in rehabilitation centers, and enhance service quality.

Conclusion

Finally, these findings can help educators develop curriculum content and structure and challenge the field to develop assessment strategies that assess the impact of teaching SDH on patient- and community-level outcomes. In this study, addressing the needs and requirements for social accountability and considering SDH in the education of rehabilitation sciences is a ground for further research, including assessing the current situation of rehabilitation fields in different universities due to the defined requirements, research on effective teaching and learning approaches for various stakeholders, and review best practices and challenges in this regard.

Study limitations

This qualitative study has some limitations. First, the expert panels in our study do not represent all medical/rehabilitation schools and practitioners nationally. Second, academic staff and students from all rehabilitation groups were not included in this study. Finally, the expertise of the participants was limited to the fields of physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.287). All group discussion sessions were recorded with verbal consent obtained from the participants. They were free to stop participating and leave the interview session whenever they wanted. The discussion reports included no names or other information identifying the participants, ensuring participants’ privacy and confidentiality.

Funding

This study was supported by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Science (Grant No. 2677/T/00).

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Meroe Vameghi and Zahra Jorjoran; Formal analysis: Meroe Vameghi, Marzieh Takaffoli and Zahra Jorjoran; Funding acquisition: Meroe Vameghi; Methodology: Meroe Vameghi and Ameneh Setareh Forouzan; Project administration: Meroe Vameghi, Zahra Jorjoran Shushtari and Giti Bahrami; Writing–review and editing: Meroe Vameghi, Marzieh Takaffoli, Zahra Jorjoran Shushtari and Giti Bahrami; Software: Marzieh Takaffoli; Writing – original draft: Zahra Jorjoran; Investigation: Marzieh Takaffoli, Zahra Jorjoran Shushtari and Giti Bahrami; Investigation: Zahra Jorjoran Shushtari and Giti Bahrami; Supervision and validation: Ameneh Setareh Forouzan.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the students, faculty members and non-governmental organizations participating in the project.

References

Social accountability is crucial to medical education and health profession programs, as they are held responsible for their actions and impact on the public [1-4]. Regarding social accountability, the medical profession has specific responsibilities and privileges bestowed upon them by society [5]. In 1995, the World Health Organization (WHO) defined the social accountability of medical schools as the obligation to direct their education, research, and service activities toward addressing the priority health concerns of the community, region and/or nation they serve [1]. These obligations are reinforced through various means, such as legislation, regulation, and accreditation. This means placing the responsibility on medical schools to produce capable students who can effectively address the community’s needs [6]. Social accountability encompasses the enduring social contract between the medical field and society [6, 7, 8]. Furthermore, the role of universities in social accountability and sustainable development has been indicated. When higher education institutions develop an integral, socially responsible collaboration with the broader community, opportunities are created for unique epistemic advances for the stakeholders involved [9]. Considering the importance of social accountability in medical education, an increasing body of evidence emphasized the vital and prior role of social determinants of health (SDH) in this regard [1, 10].

WHO [11] defines SDH as the conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life. These forces and systems include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems. Notable evidence emphasizes that the role of SDH is imperative in promoting social accountability in medical schools, enhancing collaboration between sectors in the health domain, implementing evidence-based interventions, and substantially reducing health inequalities and improving health outcomes [12]. Although addressing the SDH requires a broad range of actions that involve the collaboration of multiple sectors (e.g. education, justice, and employment) and different levels of government, healthcare workers at the front of clinical care are nonetheless important players and potential catalysts of change [13, 14]. In this regard, Andermann [14] posits that clinicians can address social determinants in their clinical practice through three levels, including the patient level (e.g. asking patients about social challenges in a sensitive way), the practice level (e.g. ensuring that care is accessible to those most in need), and at the community level (e.g. physicians can advocate for more supportive environments for health). These practices and actions require specific knowledge and skills that universities should address. On the other hand, with demographic changes, shifts in the patterns of diseases, injuries and disorders and increased public awareness and societal expectations for quality specialized services, the need for revised educational programs emphasizing SDH has become more apparent [15]. Hence, by providing students with opportunities to develop a more robust SDH and health equity model, it is ensured that the next generation of physicians is providing better care for the most vulnerable target group [16].

Furthermore, the challenges in addressing SDH within medical education include inadequate planning, an insufficient emphasis on social responsibility, and a tendency to neglect environmental factors [12, 17]. Studies reveal that to overcome these challenges, medical schools and residency programs are successfully incorporating educational approaches and models that focus on SDH, such as participatory and community-based approaches [18 -21], collaborative learning approaches [22, 23], transformative learning [20, 24-26], service-based learning [12, 17, 20, 25-27] and experiential learning [16, 28, 29]. Moreover, there are some pieces of evidence that to integrate SDH in medical education, the educational content should focus on community engagement, identification of local contexts, health policies, support-oriented education and student skills development. It should teach students to consider population diversity and leadership [30].

In Iran, addressing social accountability has been paid considerable attention to in policies related to medical education in recent years, which is defined as one of the main goals of the medical education system in Iran [31]. Additionally, the committee of accountable and justice-oriented education specifies operational plans and actions to fulfill its objectives, including revising and developing educational curriculums and monitoring them in terms of social accountability and responsiveness to the needs of the target population and making students and academic staff alert and knowledgeable about SDH in their practices [32].

As noted, integrating SDH into medical education has gained increasing attention internationally, with studies focusing on curriculum development and review [33-35]. Meanwhile, in Iran, different medical universities’ considerations for social accountability, their challenges [36, 37] and developing tools or exploring necessities for revising curricula to fulfill its goal have been studied [15, 38, 39] as research reveals the lack of attention in the current medical education of Iranian medical students [15, 36, 37].

As mentioned, while some studies have examined social accountability in medical education in Iran, no studies have deeply focused on SDH specifically for rehabilitation sciences. Moreover, no comprehensive tools exist for national-level development of SDH for medical education. On the other hand, the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences has made significant contributions to the development of rehabilitation in Iran since its responsibility and mission in this term. The first step to integrating SDH into medical education is to clarify its educational needs and requirements.

Accordingly, this study identifies the requirements from the point of view of rehabilitation education beneficiaries, including students, faculty members, and non-governmental organizations. By addressing this research gap, we can contribute to developing evidence-based interventions and enhancing social accountability in medical education, ultimately leading to improved health outcomes and reduced health inequalities.

Materials and Methods

The research paradigm employed in this study was qualitative and conducted using conventional content analysis. The study occurred in 2022 at the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Health. Various aspects of actions leading to social accountability were examined based on a review of relevant sources regarding medical universities’ social accountability. Among these aspects, the SDH approach was selected as the primary focus of the study, considering its higher feasibility for implementation within universities.

Study participants

The study population consisted of students and academic faculty members from three departments: Physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy at the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Health. Additionally, members of non-governmental organizations affiliated with rehabilitation and an external rehabilitation specialist were included in the study.

Participant’s selection method

The sampling method employed in this study was purposive. Academic faculty members needed at least three years of clinical experience in rehabilitation. Enrolling in a doctoral program in one of the three disciplines was required for students. Non-governmental and charitable organization members were included if they possessed at least three years of direct work experience with rehabilitation clients. All academic faculty members from the three educational departments were invited to group discussions. From the Physiotherapy Department, 4 participants were involved. From the Occupational Therapy Department, 6 participants were invited, and from the Speech Therapy Department, 8 participants contributed to group discussions relevant to their respective fields. Eight doctoral students from three disciplines and seven managers and experts from non-governmental organizations representing four institutions participated in group discussions. Four non-governmental organizations in the rehabilitation domain were chosen, considering diversity within the covered groups (age groups, types of disabilities and services provided). These organizations were selected based on their accessibility to Tehran and Karaj. Managers and experts of these organizations who met the study’s entry criteria were invited to participate.

Data collection method

Data collection in this study was carried out through focused group discussions with various participants, guided by the criteria for reaching data saturation. Data saturation was achieved through three separate group discussions with academic faculty members from each department. One was with students from all three disciplines, and one was with members of non-governmental organizations. All group discussions were conducted in person, except for the one with students, which was held virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic. A semi-structured questionnaire was used for data collection, consisting of open-ended questions prepared based on reviewing relevant sources and study objectives. These questions were reviewed and refined based on simultaneous data collection and analysis for subsequent group discussion sessions. The main themes of the questionnaire included participants’ experiences regarding the role of SDH in their professional services, the necessary education for students in rehabilitation fields to acquire knowledge and essential intervention skills and the changes and improvements in attitudes related to SDH. Additionally, the features of the educational environment that allowed students to better understand and acquire skills in addressing SDH were explored. The average duration of each session was approximately 3 hours, and with participants’ permission, all group discussion sessions were fully recorded. After the conclusion of each group discussion session, its content was immediately implemented and analyzed to guide subsequent sessions. The results from the group discussions were categorized into the main category: requirements of integrating the SDH approach into rehabilitation education. To re-examine the collected information, the results of the group discussions were shared with six key informants in the rehabilitation field. Three of these informants had previously participated in group discussions, while the others had not. Their input aimed to provide corrective and complementary perspectives. Subsequently, in a session attended by 3 of these key informants, their opinions were revisited and finalized.

Data analysis

The Elo and Kyngäs [40] process was utilized for the qualitative content analysis of group discussion data. To enhance the study’s credibility and accuracy, analyses were conducted using the MAXQDA software, version 2018. Immediately after each group discussion session, its content was entered into the software. Text segments containing content relevant to the study objectives were initially identified and coded as semantic units during textual analysis. These initial codes were then listed. Duplicate or synonymous codes were merged, and initial codes that shared similar semantic content or indicated similar events were combined to form preliminary concepts. At a higher level of abstraction, these concepts formed categories. As additional group discussion sessions were added and data analysis progressed, each semantic unit identified in the textual material or each code or concept generated was compared with other codes or concepts. A new initial code was created if there was no conceptual similarity to other existing concepts or codes. If there was a similarity, the new concept was added to the current code to enrich its meaning. Categories were also formed based on their relationships at different classification levels, comprising both main and subcategories.

Trustworthiness or rigor

This study considered four criteria of Lincoln and Guba [41] for the study’s trustworthiness. The researchers tried to ensure credibility by long-term engagement with data, spending enough time to collect and analyze data, having many interviewees (33 interviews), member checking, and peer debriefing. For transferability in the selection of the participants, the high diversity of their experience from different groups of students, academic faculty members, and members of non-governmental organizations was considered. To improve dependability, meetings were held with the research team to discuss the data collection and analysis process and to determine a uniform and coordinated framework for it. To achieve confirmability, all stages of the research, especially data analysis, were recorded in detail and accurately; also, several interviews, codes, and categories extracted were provided to the research team to review and evaluate.

Results

The results of the study revealed the main requirements for integrating the SDH approach into rehabilitation education. The main category was divided into two subcategories: educational content requirements and educational environment and setting requirements (Table 1).

The participants of the current study believed that to integrate the SDH approach into rehabilitation education, requirements must be considered not only in the theoretical and practical educational content of rehabilitation disciplines but also in the environment and academic settings, especially in clinical training.

Educational content requirements

Based on the findings of the current study, the necessary educational content to be taught to students in the field of rehabilitation was divided into three subcategories: knowledge, skills, and attitudes.

Knowledge Requirements

According to participants’ views, rehabilitation students should possess sufficient knowledge to recognize the role of SDH. The most important areas of this knowledge are highlighted below (Table 2).

The participants emphasized students’ need to learn about SDH and their role in rehabilitation services including access to services, rehabilitation intervention effectiveness, and compliance with treatment. Experiences of faculty members, students, and representatives from non-governmental organizations, indicated that various social factors, such as gender, ethnicity, language, education, awareness of patients and their families, and cultural norms and values, such as social stigma play a significant role in patients’ access to rehabilitation services.

“There are many times when people are afraid of social stigma. She brings her child about two years, stating that her family is unaware of her situation and she comes sneakily so as not to stigmatize her child” (speech therapist).

Additionally, economic status and access to financial support resources significantly impact health status. Rehabilitation education should provide the necessary knowledge in this area.

“A person with acute back pain who does not work for a week and has no work problems is less likely to get chronic back pain and this has been proven, so social issues have a great deal of influence” (physiotherapist).

the participants of this study emphasized the significance of concepts related to the international classification of functioning, disability, and health framework, such as a comprehensive definition and holistic view of health and disability, the role of environmental and social factors in individuals’ functioning and participation, and rehabilitation within the social and family context. They considered this perspective in alignment with the SDH approach. However, they believe the concept needs to be developed and receive more attention in education.

Additionally, the participants emphasized education of preventive and therapeutic lifestyle-related knowledge within the rehabilitation domain. According to their viewpoint, therapists need to know various preventive and therapeutic methods and patterns and plan interventions tailored to patients’ personal and social contexts. Moreover, in integrating SDH into the rehabilitation education program, it is essential to consider service categorization, patient referral systems, and service differentiation based on prevention levels.

“Physical activity is a sub-branch of lifestyle; that is, if we truly want to consider lifestyle, it is closely related to our social issues” (physiotherapist).

There was also a strong emphasis among many participants on the necessity of increasing knowledge about ethical principles and patients’ rights:

“A student should also be trained to understand his role as an occupational therapist within the health care system. Some people are making progress in private family matters. Are you legally permitted to speak? Are you allowed to evaluate? Where can you work” (occupational therapist).

Skill requirements

Table 3 illustrates the skill requirements for integrating SDH into rehabilitation education and its subcategories based on the study findings.

According to the participants of this study, within university rehabilitation education, acquiring individual skills and life skills, including self-awareness, self-confidence, self-esteem, anger management and assertiveness, is crucial. These skills are necessary for team-based collaborations among students, cooperation with other specialists, and working with families dealing with various and severe impairments. In addition, they are essential to prevent the negative impact of personal and social situations of service providers on their performance. Also, in addition to specialized skills, students and therapists should learn communication and empathy skills for clients and families. They should learn skills to build trust and engage service users and their families. Complete trust and collaboration are achieved when service users and their families actively participate in treatment. Moreover, therapists should be culturally and socially sensitive and learn how to establish connections with various age groups, especially children and older people.

“For some speech disorders, family conditions can be very effective, for example, what are your child’s conditions, what environment he is in, how stressful it is, and I believe that increasing this skill in students can be very beneficial” (speech therapist).

Based on the study findings and considering the multidimensional approach of SDH, teamwork-related skills are also necessary.

“The majority of people who come to us usually have several deficiencies together, such as aphasia clients need SLP and occupational therapy, as well as physiotherapy. The interaction between these different therapists can prove useful” (student).

When facing patients, students should be able to assess various aspects of social determinants in them. They should also be able to create a patient profile that considers these factors within different cultural and social contexts. Besides, to ensure a comprehensive understanding of social determinants, periodic assessments should be conducted. Another skill requirement is the ability to formulate specialized treatment plans based on SDH. Students must be educated in providing interventions that align with these factors and existing social capacities after a thorough evaluation.

“As an occupational therapist, I am confident this method is appropriate for treating the patient. However, he does not have access to a toilet, so we have to inquire whether he can use the toilet. In this course, the student should be able to assess how these factors should be evaluated” (occupational therapist).

Considering the participants’ perspectives, there is currently insufficient knowledge and evidence of the impact of social determinants in rehabilitation. This underscores the necessity of acquiring skills in various quantitative and qualitative research methods and disseminating results. Additionally, rehabilitation specialists play a crucial role in interacting with rehabilitation organizations and advocating for the rights and rehabilitation needs of different societal groups. They should learn and employ advocacy, lobbying, and negotiation skills to enact necessary reforms and realize individuals’ rights, utilizing available capacities to benefit patients and their families.

“I intend to dedicate part of the training, whether in the clinic or student training, to finding charities because a therapist’s relationship with a charity is much more effective than the individual direct expression of the problem” (speech therapist).

Attitude requirements

The participants strongly emphasized the necessity of applying knowledge and skills related to SDH with a comprehensive and holistic perspective toward service users as individuals with various physical, psychological, social, family and spiritual dimensions.

“Our only definition is that of the WHO, which does not specify health as a state of welfare, but rather a state of well-being. In other words, health is not only the absence of disease and disability, but also a state of well-being and a healthy physical, mental and social condition” (NGO).

According to the participants, given the numerous operational challenges in providing rehabilitation services, confidence can only be gained by educating and institutionalizing ethical, fair, and rights-based approaches toward patients and their families. This ensures that students will provide adequate services toward justice in healthcare in the future. Rehabilitation specialists must also adopt a holistic and systemic approach to the healthcare system. This involves considering health services within an integrated and interconnected framework that covers patients’ diverse and comprehensive needs. The new approaches to rehabilitation all focus on empowering individuals with disabilities and those in need of rehabilitation services which emphasizes the necessity of creating suitable platforms for their participation and involvement in society. From the participants’ viewpoint, rehabilitation specialists should recognize that their service users extend beyond those who physically visit specialized rehabilitation centers. With a community-based rehabilitation approach, it is crucial to tailor specialized services based on available resources and collaboration with the local community to ensure accessibility and utilization.

“There are several problems you have listed under the heading of social issues, including access, income, and awareness. All of these factors have made it difficult for many people to access these services. Instead of bringing people to clinics, hospitals, or centers, let’s send specialists to the community to offer services” (occupational therapist).

Educational environment and setting requirements

Based on the study findings, the theoretical and clinical educational environment must possess specific conditions and characteristics to integrate the SDH approach into rehabilitation education. These requirements were categorized into three subcategories: basic and general requirements of the educational setting, theoretical educational setting requirements, and clinical educational setting requirements (Table 4).

Basic and general environmental and educational setting requirements

The participants pointed out that one of the fundamental and general requirements of the educational setting is to train faculty members in rehabilitation fields in the concepts of SDH and how to act at different levels with this perspective. This ensures that these teachings can be effectively conveyed to students. Additionally, theoretical and clinical teachings will effectively achieve the necessary impact when theoretical and clinical knowledge and skills related to SDH are assessed and evaluated among students.

Theoretical educational setting requirements

The participants believe that, besides revising all current syllabi and courses based on updated and scientifically relevant resources related to SDH, there should also be coherence and coordination regarding these concepts across all applicable courses. This approach ensures that the necessity of these concepts is reiterated in various courses and students develop a comprehensive perspective on the topic. One of the significant educational resources in rehabilitation is guidelines and clinical manuals, which serve as the basis for students’ practical actions in service-provided centers. SDH educational content must be incorporated into these guidelines and clinical manuals. Another requirement highlighted by participants was the need for tailoring academic courses and materials related to SDH according to different educational levels:

“A course on SDH can be helpful at the undergraduate level, where students are more involved in internships and practical courses, to increase students’ knowledge and change their attitudes regarding health determinants. However, at higher levels, this training should be part of supplementary and specialized courses” (physiotherapist).

Clinical educational setting requirements

This study indicates that rehabilitation students’ clinical training should also possess specific conditions and characteristics alongside the requirements for preparing the theoretical educational setting. In this context, some participants emphasized that practical training can illustrate the practicality of theoretical courses related to SDH for students. This will enhance their learning motivation and education effectiveness:

“If SDH is included in the educational curriculum, but students are unaware of their practical value, and how it can benefit their work, they may not show interest” (physiotherapist).

According to the study participants, one of the requirements is the establishment of exemplary rehabilitation centers that apply the SDH approach. In this regard, the participants maintained that for students to be able to apply the knowledge and skills they have been taught in rehabilitation actions during and after their education, universities should provide real-life examples of rehabilitation centers that have operationalized the SDH approach. Students should receive training in such environments to gain practical experience.

“As an example, if I were a student and went to a central facility for clinical observation, it must have a social worker, a professor trying to acquire a sports area from, for example, the municipality, for the patients, sending the students to obtain the land. This is the facility serving as an ideal” (NGO).

Moreover, the participants believed that due to the high volume of patients, very limited time is allocated to each patient. This limits the possibility for students and therapists to assess and intervene within the framework of SDH during clinical placements. Therefore, they emphasized reducing service users and increasing visit time to focus on SDH.

Based on the participants’ perspectives in this study, a collaborative and holistic approach to SDH can only be fully implemented within university healthcare centers and students can operationalize the learned teachings when a collaborative environment is established among various rehabilitation and social and mental health experts, especially social workers and psychologists. These professionals should interact with each other and provide comprehensive and coordinated services to clients. Furthermore, participants stressed that all professionals working as a team in healthcare centers should receive education on the SDH. This will ensure a harmonized approach and performance in this area.

“Finally, if the children [students] can obtain a consultation from a psychologist, social worker, psychiatrist, and physiotherapist to implement the teamwork they study, this will be very beneficial” (physiotherapist).

The participants believe supervisory mechanisms should be in place throughout clinical training to ensure attention to SDH during clinical practice. This should involve trained supervisors working alongside students to provide necessary supervision, support, and guidance when needed.

The findings indicate that despite the significant role of family participation in integrating SDH into education, the conditions and service delivery methods in healthcare centers are not always conducive to family involvement and participation in the rehabilitation process. Therefore, as the participants emphasized, an environment that encourages and facilitates the presence and participation of families in healthcare centers is needed.

“During our bachelor’s clinical training, we did not interact much with families; they waited outside. Now, with those who have graduated, I often see that families are not present during therapy sessions. They sit outside and do not know what is happening inside the therapy session” (speech therapist).

The necessity of students’ presence in diverse fields and different contexts has been highlighted as one of the requirements for clinical education. This is because participants believe that students can apply theoretical and practical teachings on SDH when they are exposed to service users from diverse social backgrounds and encounter various social factors in different educational settings. This exposure will enable them to operationalize their learned knowledge and skills.

“We need to provide conditions for our students (because this is a gap in our job) that encourage them to have more presence, especially occupational therapy students, in schools. I know speech therapy has this presence. There was also a period when technical orthopedics were present in schools, examining proper footwear and insoles” (occupational therapist).

Finally, according to the participants’ perspective, one factor that could lead institutions where students undergo clinical training to pay attention to SDH and provide an operationalized educational environment for students is establishing a monitoring and evaluation system of institutions that focuses on social determinants of health.

Discussion

Addressing the SDH in providing rehabilitation services requires a wide range of actions and collaboration among various sectors, including education, welfare, and employment at local, provincial, and governmental levels. Frontline health service providers play a crucial role in achieving this goal. However, they must be well educated about the impact of social determinants on community health outcomes and how to address these in practice. This study aimed to explore the educational needs and requirements for integrating SDH into Rehabilitation Sciences education at an academic level. According to our knowledge, this is the first study focusing on understanding the educational needs of specialized rehabilitation service providers concerning SDH. This study emphasizes developing social accountability skills and considering SDH in the service delivery process. This study reviewed rehabilitation education programs in selected fields, including speech therapy, occupational therapy, and physiotherapy. The study’s findings were categorized according to the requirements for integrating the SDH approach into rehabilitation sciences education.

The study’s findings reveal that rehabilitation students must have a comprehensive understanding of SDH. Many participants acknowledged the importance of recognizing the impact of social factors such as gender, ethnicity, language, education, and cultural norms on patients’ access to rehabilitation services.

The participants shared some of their lived experiences regarding the significant role of economic factors on patients’ health outcomes and referenced scenarios where financial stability impacted recovery from conditions like acute back pain. This finding is supported by studies, demonstrating that economic hardship can exacerbate health conditions and limit access to necessary healthcare [42]. In this regard, it is indicated that incorporating SDH into healthcare education can significantly enhance students’ ability to address health inequities. They argue that education programs should impart knowledge and foster critical thinking skills that enable students to apply it in real-world settings [43]. This finding highlighted the importance of understanding the role of economic status and access to financial support on patients’ health outcomes by students who study rehabilitation sciences in academia.

Despite the participants’ agreement on the importance of SDH’s impact on service provision and clients, applying these factors requires a complex and intertwined set of requirements at different levels. Therefore, discussing SDH at the university level requires a comprehensive approach and changes in the content and setting of education. Most of the participants believed that students should possess sufficient knowledge of SDH to integrate these concepts into rehabilitation education. Hence, it was recommended to develop new curriculums, revise existing ones, and change teaching methods and evaluation approaches that can be used to guide rehabilitation educators. These findings are aligned with other studies [28, 36]. Moreover, in line with Moffett, Shahidi [33], provision of an SDH curriculum and integration of that into a core emergency medicine clerkship, our findings place the highest emphasis on practical education of these concepts in a clinical context. Some participants expressed that providing theoretical education about SDH to students without teaching these concepts practically to patients and without converting them into practical skills would render such education ineffective.

Alongside other studies [44, 45], our results revealed that educating students majoring in Rehabilitation Sciences about SDH not only acquaints them with the role of social determinants in various health outcomes but also equips them with the capability to take action and intervene at different levels, including the patient, practice, and community levels. Moreover, it instills in them the mindset that, armed with knowledge of SDH and skills such as advocacy, lobbying, negotiation, and most importantly, interdisciplinary and intersectoral collaboration, they can effectively work towards improving the health of the individuals and community and reducing health inequalities. Therefore, it is suggested that integrating SDH should be considered alongside theoretical and foundational teachings, and clinical education should focus on designing educational intervention packages.

In this regard, the development of a framework for integrating SDH into the educational program of rehabilitation sciences in academia should include three main areas: education, collaboration with the community, and ensuring alignment of policies and responsibilities for all beneficiaries [46]. A curriculum focused on developing social accountability in rehabilitation professionals requires innovative, collaborative, and transformative educational approaches. As recommended in similar studies [10], initial discussions for developing or revising educational curricula should focus on how the curriculum can best create opportunities for social awareness and responsibility.