Volume 25 - Special Issue

jrehab 2024, 25 - Special Issue: 682-701 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Soleimani F, Babaiy Z, Vahedi M, Nobakht Z, Shirinbayan P, Ghorbanpour Z et al . Determining Item Sequence of Bayley Scale in Persian Language Children. jrehab 2024; 25 (S3) :682-701

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3418-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3418-en.html

Farin Soleimani1

, Zahra Babaiy2

, Zahra Babaiy2

, Mohsen Vahedi1

, Mohsen Vahedi1

, Zahra Nobakht1

, Zahra Nobakht1

, Peymaneh Shirinbayan1

, Peymaneh Shirinbayan1

, Zahra Ghorbanpour1

, Zahra Ghorbanpour1

, Fatemeh Hassanati *3

, Fatemeh Hassanati *3

, Zahra Babaiy2

, Zahra Babaiy2

, Mohsen Vahedi1

, Mohsen Vahedi1

, Zahra Nobakht1

, Zahra Nobakht1

, Peymaneh Shirinbayan1

, Peymaneh Shirinbayan1

, Zahra Ghorbanpour1

, Zahra Ghorbanpour1

, Fatemeh Hassanati *3

, Fatemeh Hassanati *3

1- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare & Rehabilitation Sciences.Tehran, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,fatemehhasanati64@gmail.com

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare & Rehabilitation Sciences.Tehran, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 1938 kb]

(670 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4045 Views)

Full-Text: (676 Views)

Introduction

The Bayley scale of infant and toddler development (Bayley III) is one of the global standard assessment tools for measuring early childhood development. This scale is used for clinical and research purposes in some countries [1]. However, some studies have demonstrated that the sequence of items and cut-off points of this scale, standardized for American children, may not be appropriate for non-American children [2-5]. These results denote the necessity of adaptation of developmental scales to various cultures. Studies in other countries have used the norms of the original version (the American norms), in which the cut-off points, the sequence of items and scoring results may not be appropriate for use in other populations [5-9]. Therefore, modifying the sequence of items, particularly in developmental scales, should be carried out following different communities regarding their language, culture, and demographic characteristics [7, 10].

According to the results regarding the adaptation of Bayley in the Dutch language, the development of motor abilities in Dutch children was slower than in American children, and children in any age group were two age steps behind in gross motor. The sequence of items was also assessed in comparison with the original version of the scale. The results demonstrated that the sequence of items in the Dutch language was not much different from that in the American version [10]. Hence, the appropriateness of the item sequence is one of the essential issues in the standardization of scales.

The Bayley-III scale is an individually administered tool for measuring the developmental performance of 1-42-month-old infants and toddlers. This scale is suitable for identifying children with developmental delays and helps the therapist design an appropriate treatment plan [1, 11]. This scale assesses the development of children in an observational manner in three cognitive, language (receptive and expressive communication) and motor (gross and fine) domains [1]. To perform the scale, the chronological age was adjusted for prematurity, and considering 17 age groups, the starting point was specified, then the test was done. Each starting point contains three main items, and if the child does not perform one of the three items of the starting point, the test goes back to a later age stage. Furthermore, the scale stops if the child does not respond to five consecutive items. Hence, the starting and stop points are decisive in the final score and, consequently, in determining the child’s ability. Assuming that the scale’s items are arranged based on the conventional developmental sequence in each environment, any item located after the stop point is assigned a score of zero and all the items located before the starting point are assigned a score of one. Therefore, based on the scale’s structure, the sequence of items considerably affects the child’s overall score [1].

Children of parents with different cultures, races, environments, education, socio-economic levels, and developmental backgrounds seem to acquire skills and abilities differently. Thus, based on these differences, the sequence of items of the original version of the Bayley-III scale in other countries may evaluate children’s abilities more or less than the actual level. Given the need to precisely assess the children’s early childhood development and the effect of various factors on developmental domains, including cognitive, motor and language areas, it is essential to determine the appropriateness or inappropriateness of the exact sequence of items for Persian-language children. Therefore, the current study investigates the appropriateness of the sequence of items for the Bayley-III scale in Persian-language children by specifying the number and location of items with deviations in cognitive, language and motor scales and its effect on the test’s final score.

Materials and Methods

This was a descriptive-analytical study of a secondary type, and the data on the psychometric properties of the Bayley-III have been utilized for the study. The Persian version of the Bayley-III has appropriate face and content validity [6]. Moreover, the validity was assessed through three methods internal consistency, test-re-test, and construct validity, using the factor analysis method and comparison of mean scores [6]. The mean Cronbach α coefficients for all scales are higher than 0.76 and the Pearson correlation coefficient in different sub-scales has been reported to be a minimum of 0.991 (P˂0.001) [6]. In the initial study, 404 children in 17 age groups were investigated by the Bayley-III. The children were selected using the convenience sampling method from the health centers of Tehran City, Iran, between 2013 and 2014. The inclusion criteria were being 1 to 42 months old, having normal development, and having the Persian language. The consent form was completed by the parents and the scale was administered by a trained examiner with a master’s degree in occupational therapy or psychology [6].

In this study, the sequence of items of the Bayley III for Persian-language children was assessed by determining the frequency and the number of individuals who gained a score of 1 in each item. The proportion of positive scores, which can vary between 0.00 and 1.00, was calculated for each item. As the difficulty of the items increases during the test, it is expected that a smaller number of individuals will get a score of 1 along the scale, and naturally, a larger number of individuals are expected to get a score of 1 at the beginning of the test. If the results are different, it indicates that the item is not located in the proper position and the sequence should be changed. Items diverging >0.05 in proportion to positive scores (either higher or lower) from the previous or following items in the sequence were denoted its deviation from the expected general pattern, and it was called a deviant item [1].

Therefore, First, deviant items were identified. Then, the location of these items in the sequence and whether the item is located at the starting point was specified because a deviant item located at the starting point can influence the child’s total score. If the score of a deviant item located at a starting point was over 0.05 less than the previous item, it demonstrated difficulty and was called a difficult item. However, the presence of this pattern does not significantly impact the test scores because, according to the reversal rule, the examiner should return to the lower starting point for the age group. Nonetheless, if the item had a positive deviation from the general pattern, it denoted the easy item in such a way that it received a score of >0.05 from the following items. In this case, the examiner did not use the reversal rule and according to the test instructions, since the individual’s score in all previous items would be considered positive, the child’s ability would be considered higher.

After identifying the deviant items, the percentage of children who scored 1 in that item was specified (the number of responses to the deviated item), followed by specifying the percentage of individuals who correctly responded to the item before (the number of responses in the previous item) and after (the number of responses in the following item) the deviant item. Furthermore, the difference between the items before and after (the amount of deviation) the deviant item was specified.

Hence, to do this, we calculated the mean scores of the items before and after the deviant item, the mean score of the deviant item, and the percentage of children of any age group who correctly responded to the deviant item. Furthermore, we specified to which age group the item was assigned and whether it was at a starting point or not. It was also determined that the item was difficult or easy. Additionally, after specifying the age groups to which the deviant item belonged, the percentage of individuals in that age group who correctly responded to the deviant item (the rate of transition from the deviated item according to the age group) was also specified. It was expected that this value would be <0.95 for difficult items and >0.95 for easy items.

Results

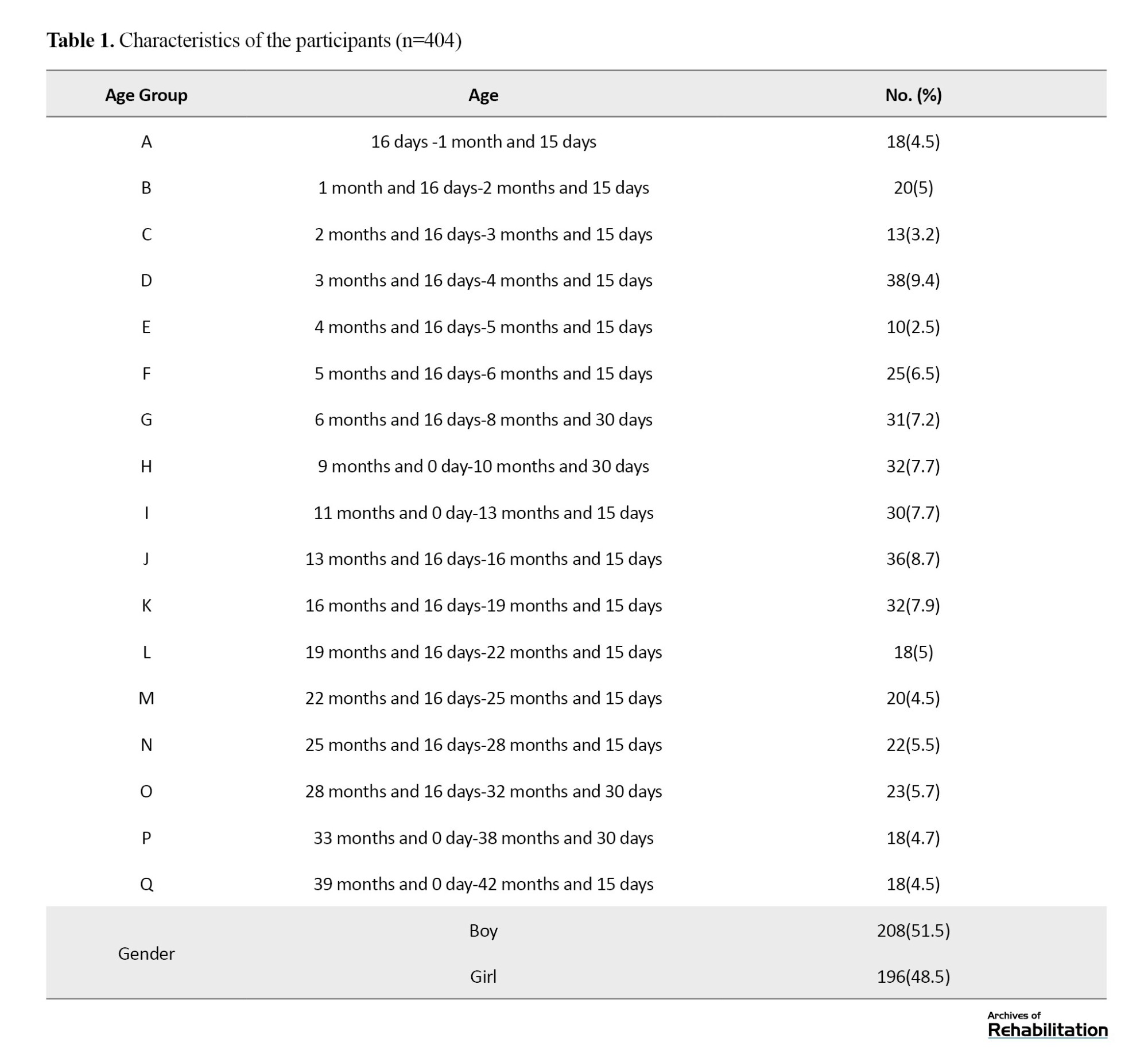

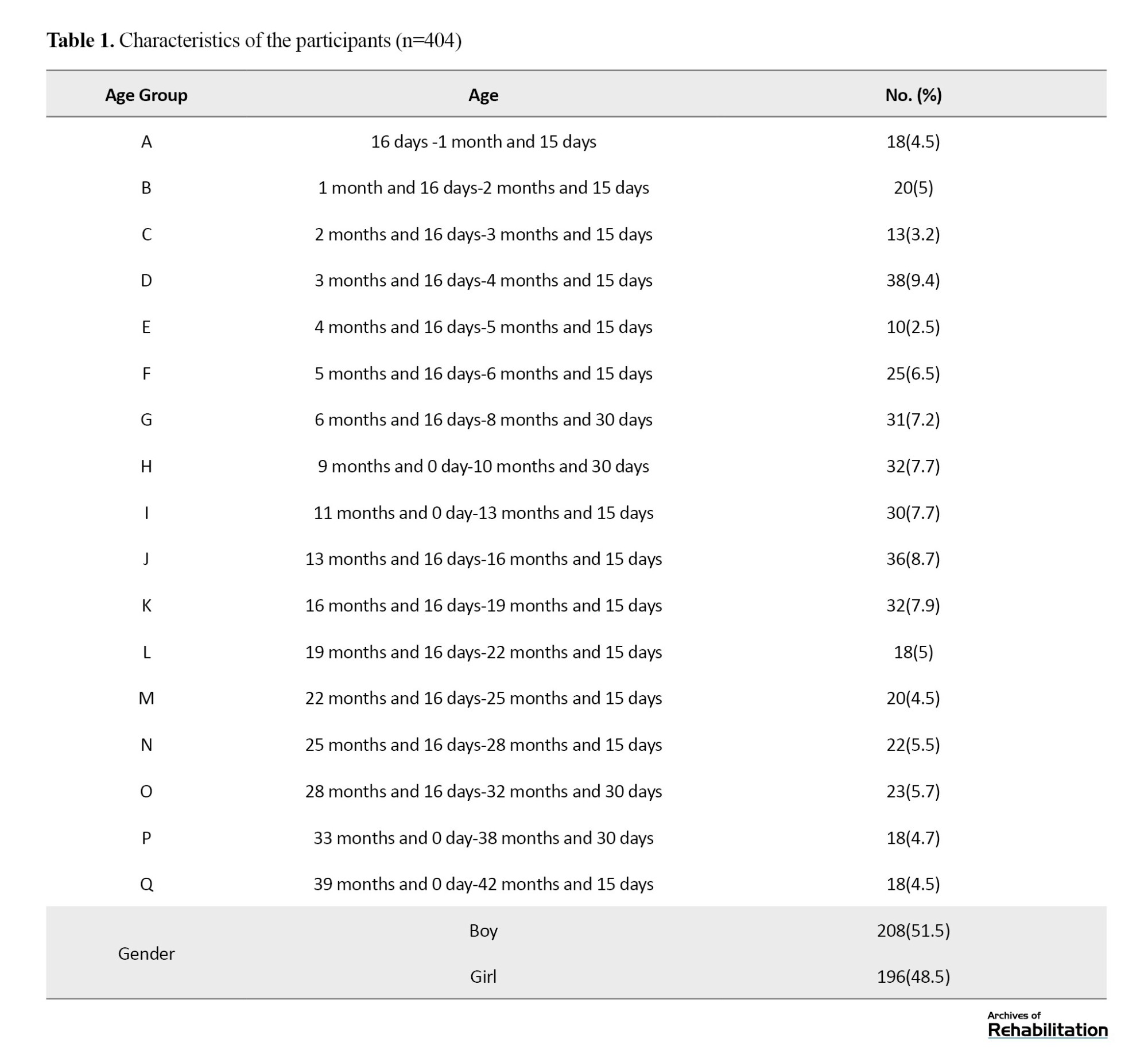

The participants in this study consisted of 404 Persian-language children (1-42-month-old) in 17 age groups, of which 51.5% were male. The lowest number of children (n=10) belonged to the age group E (4 months and 16 days to 5 months and 15 days), and the highest number (n=38) belonged to the age group D (3 months and 16 days and 4 months and 15 days).

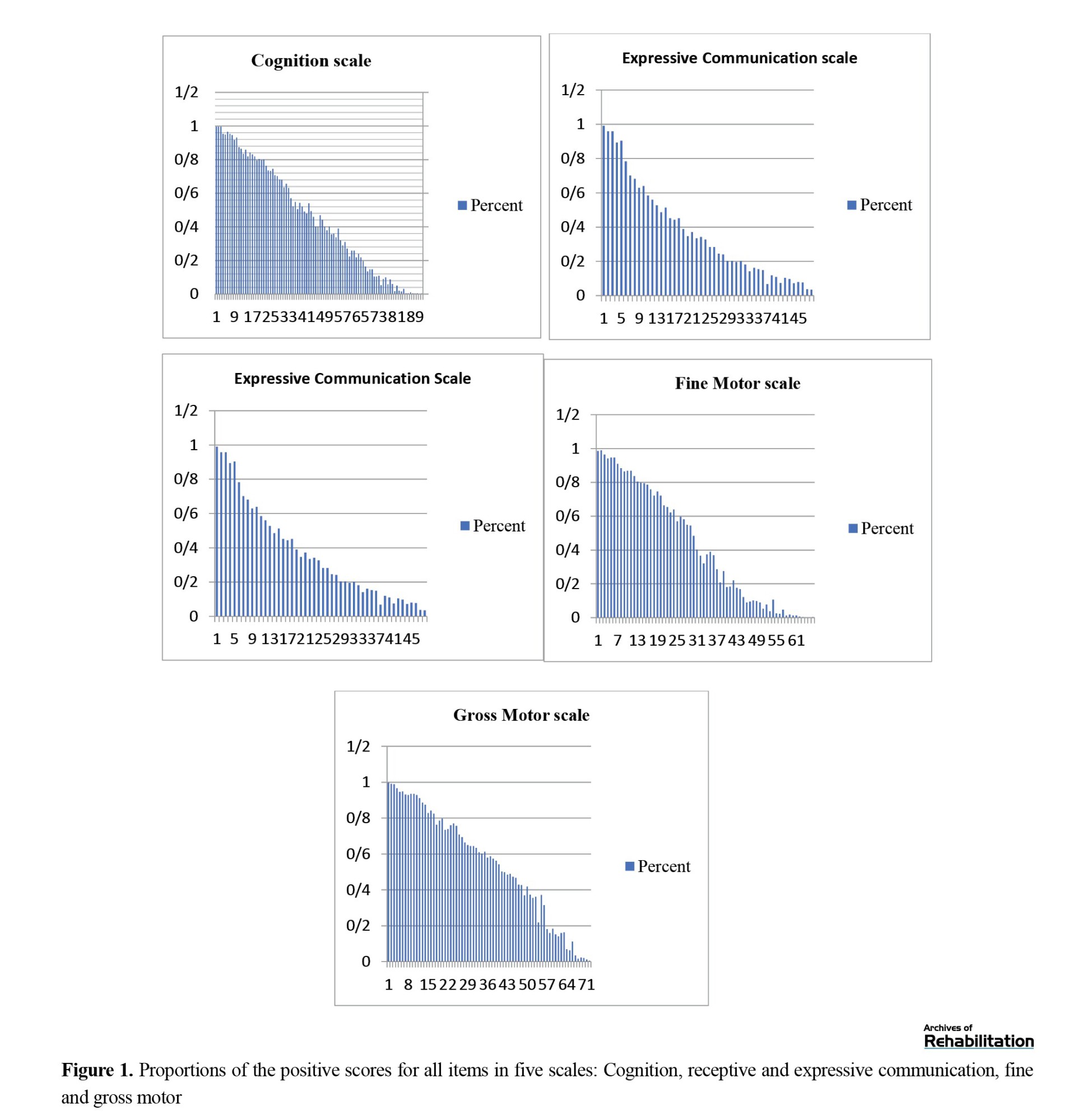

The individuals’ positive scores were determined for each item. The number of individuals receiving positive scores in the sequence of items means the percentage of individuals in different age groups who successfully responded to each item and accomplished that item. The order of the Bayley III items, similar to other developmental scales, is such that by going forward in the scale, the ability to respond positively decreases and this share declines over time because the difficulty of the items is enhanced, which is normal. However, some items violate this sequence. Figure 1 shows the items in which a larger percentage of individuals did not follow the main sequence in various domains of the scale.

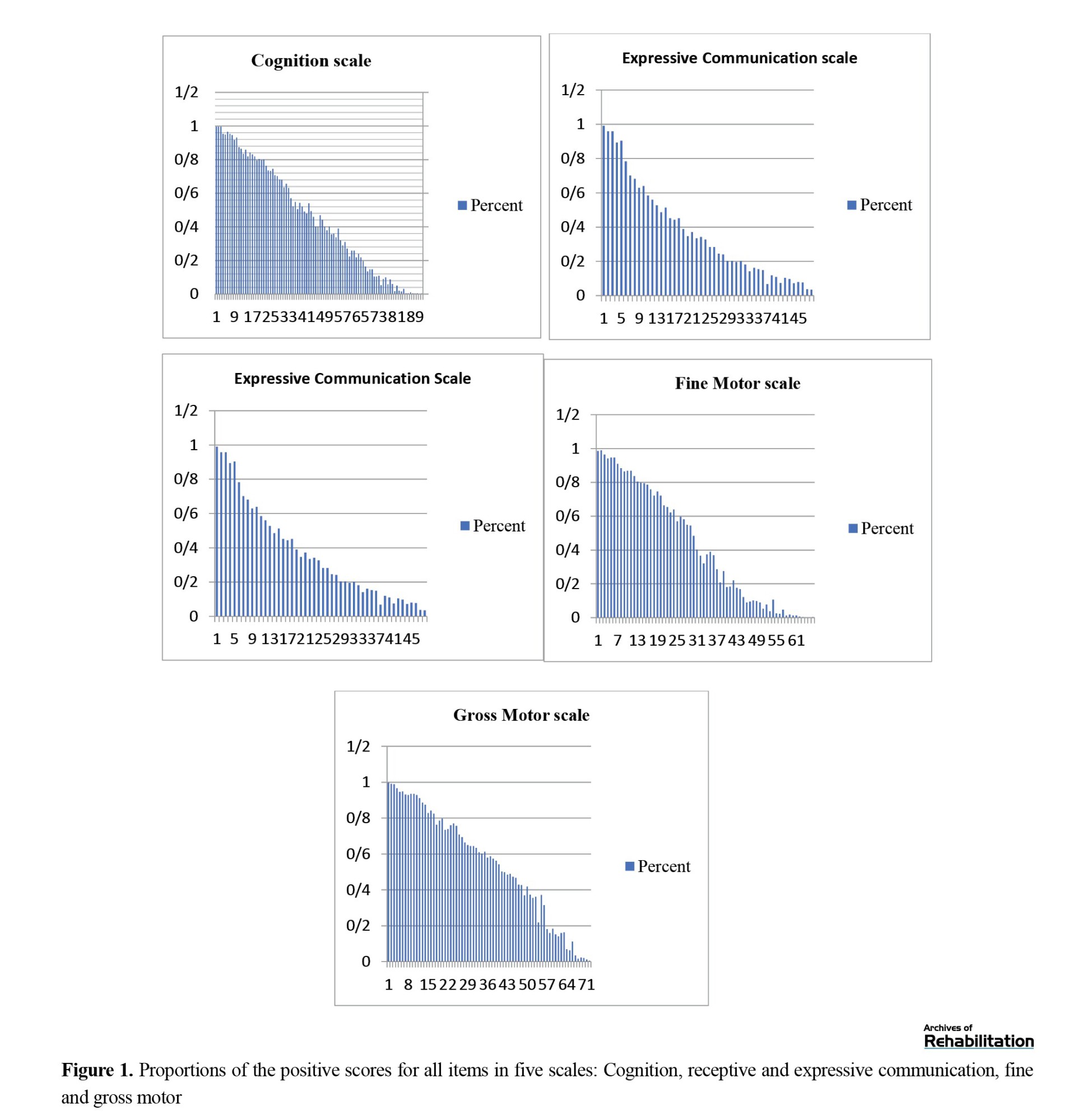

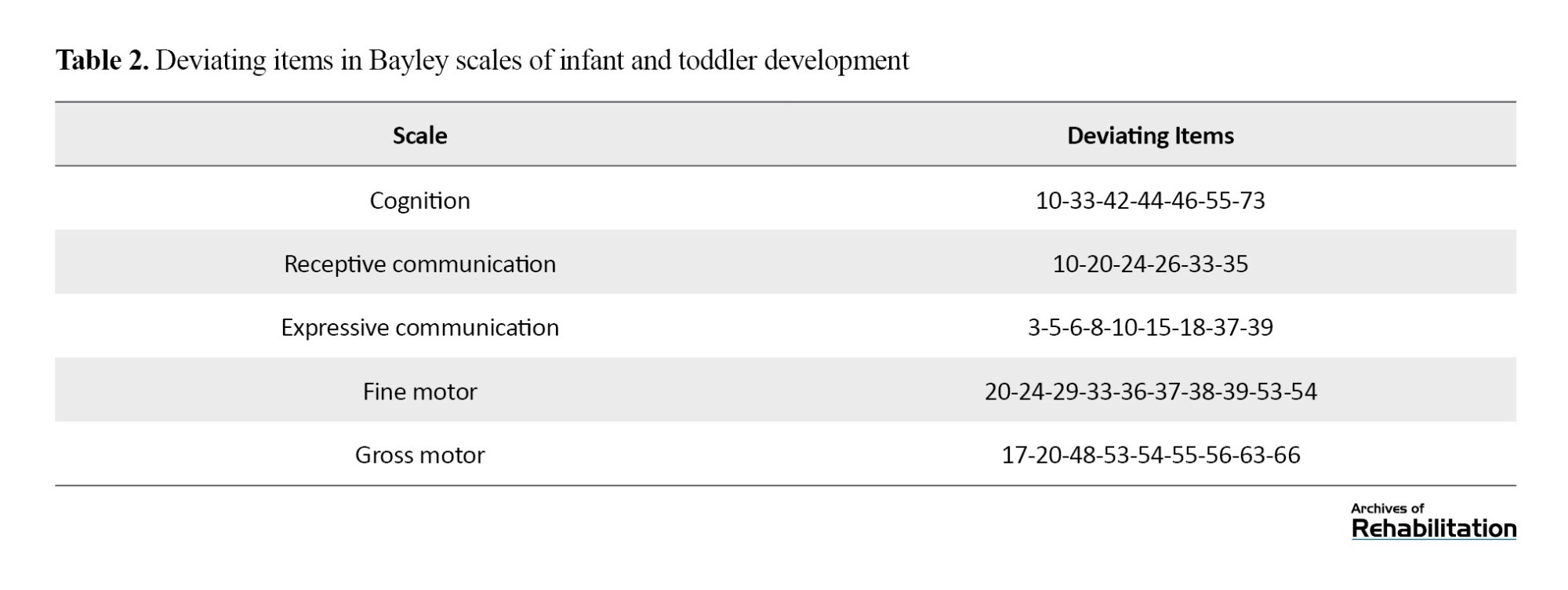

Subsequently, the deviant items were specified. The sequence of items was investigated in 404 children. The items were arranged from easy to difficult, and each item was assigned a score of 0.00 or 1.00. According to the scoring method of the scale, for each item, 404 scores (the number of participants) were available for analysis. The items where the decreased number of positive responses indicated the increased difficulty of the item, i.e. the item was difficult and fewer individuals responded to it. Overall, in this sequence, 41(13%) out of 326 items (the total number of scale items in 5 domains) deviated from their previous or following item by >0.05. On the cognitive scale, 7(8%) out of 91 items, in the receptive communication scale, 6(12%) out of 49 items, in the expressive communication scale, 9(19%) out of 48 items, in the fine motor scale, 10(15%) out of 66 items, and in the gross motor scale, 9(12.5%) out of 72 items deviated from the sequence of items (Table 2).

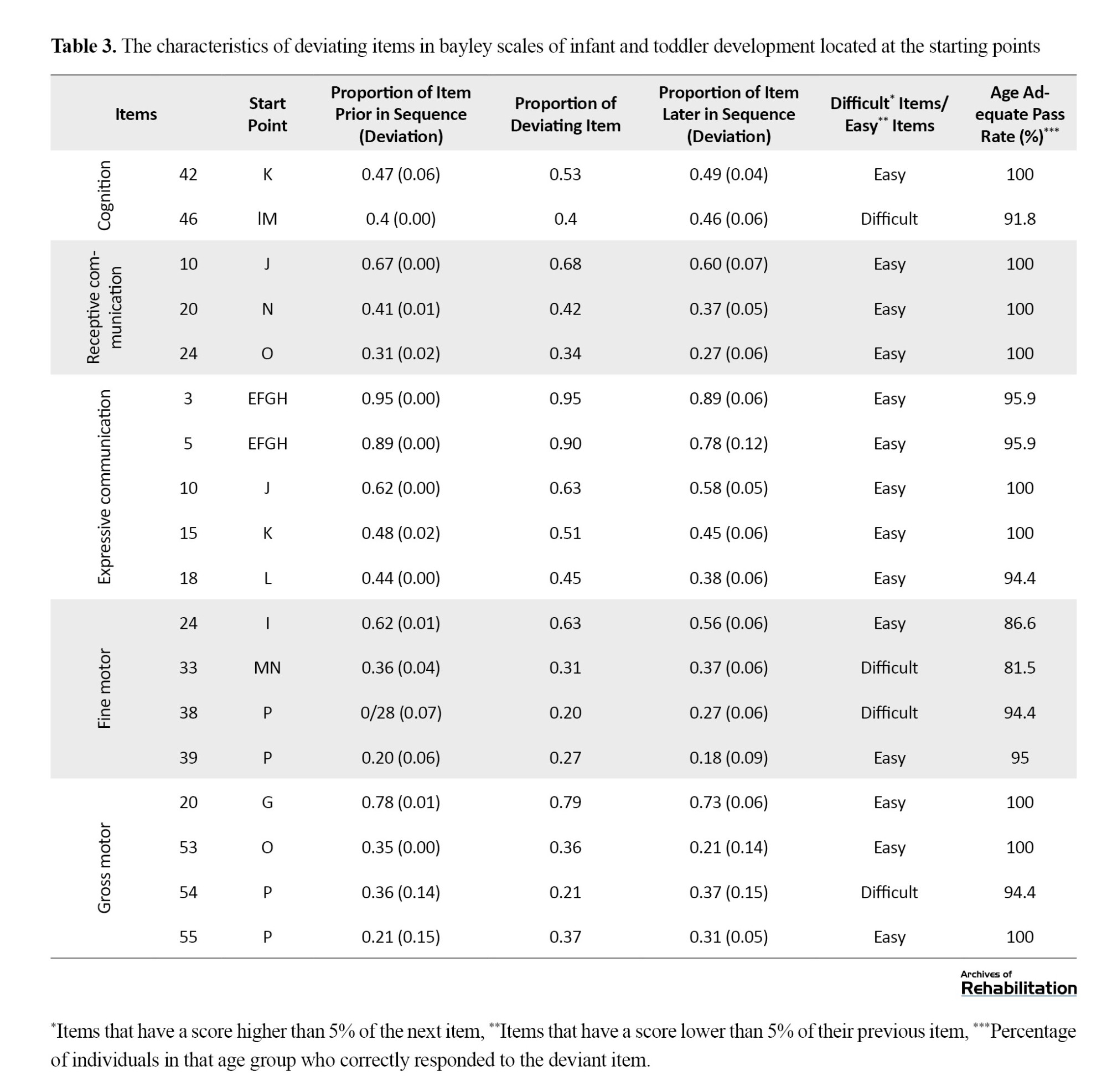

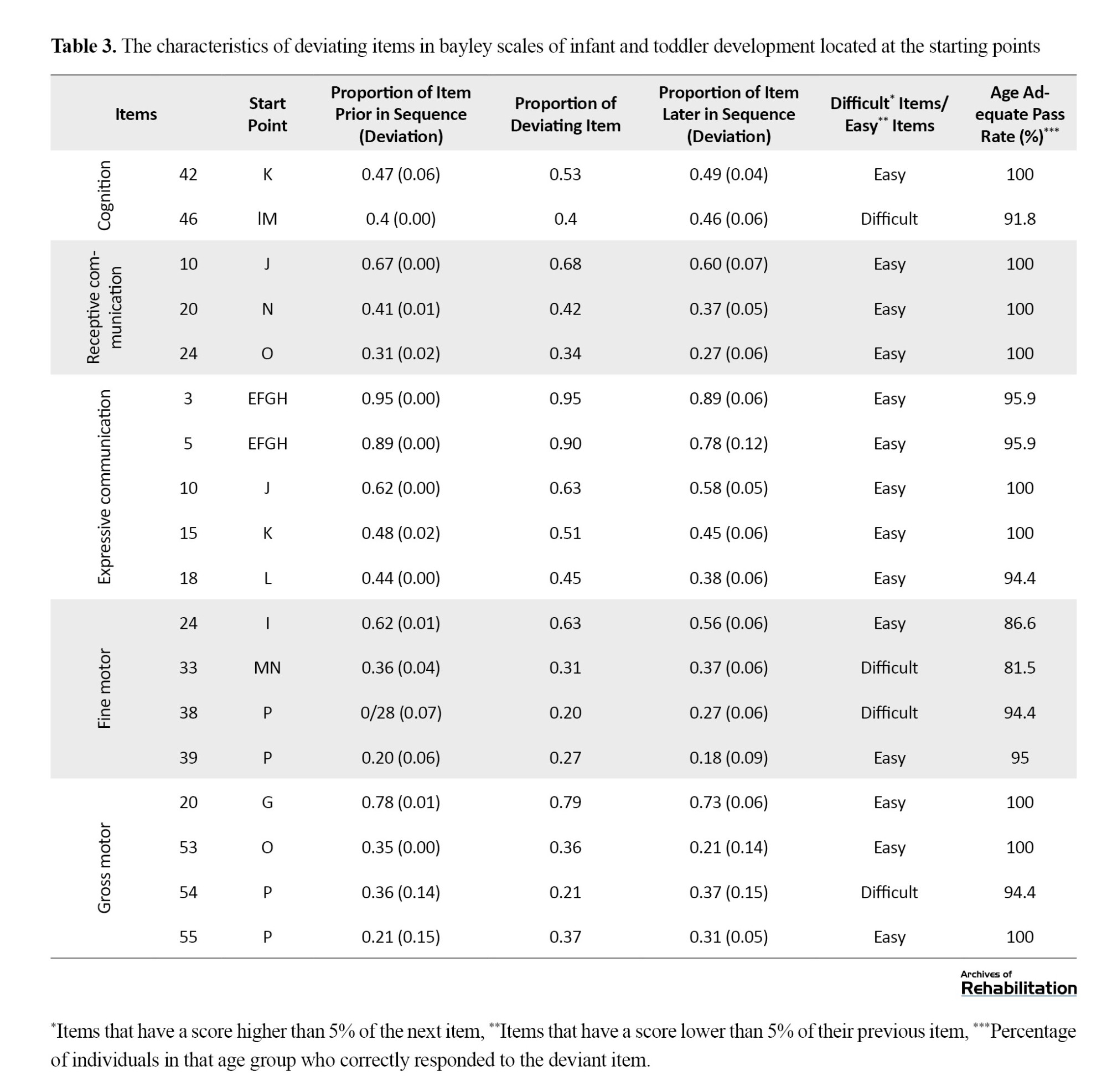

In addition, 27 out of 41 items were related to one of the 3 starting points, among which 9 items progressed based on the routine of the items’ getting difficult gradually (the cognitive item number No. 33, the expressive communication item No. 8, the fine motor items No. 20, 29, 36 and 37 and the gross motor items No. 17, 48 and 56). However, the degree of difference in the number of positive responses was >0.50. Four items were difficult according to the routine (cognitive item No. 46, fine motor items No. 33 and 38 and the gross motor item No. 54) and 14 items were easy (cognitive item No. 42, receptive communication items No. 10, 20, 24, the expressive communication items No. 3, 5, 10, 15 and 18, the fine motor items No. 24 and 39 and the gross motor items No. 20, 53, and 55) (Table 3).

Since the child’s total score will be problematic if the easy item is at the starting point, the characteristics of the items in the three starting points are provided in Table 3.

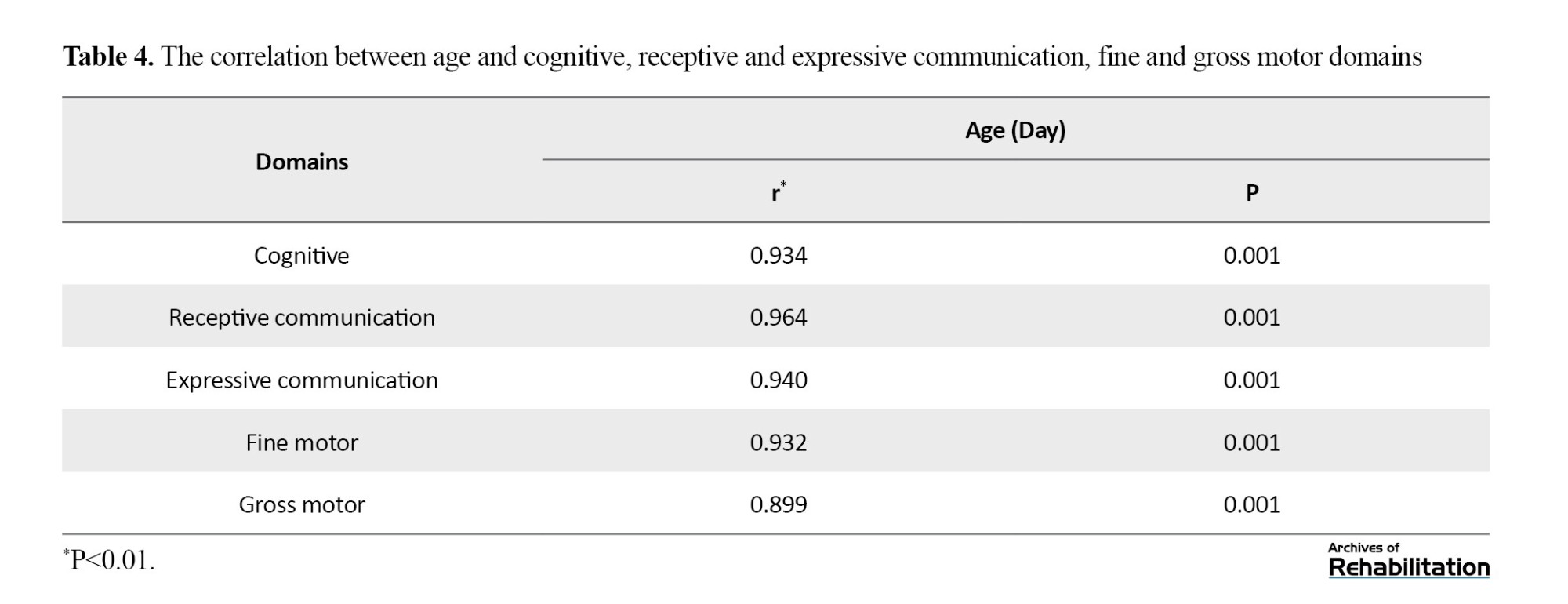

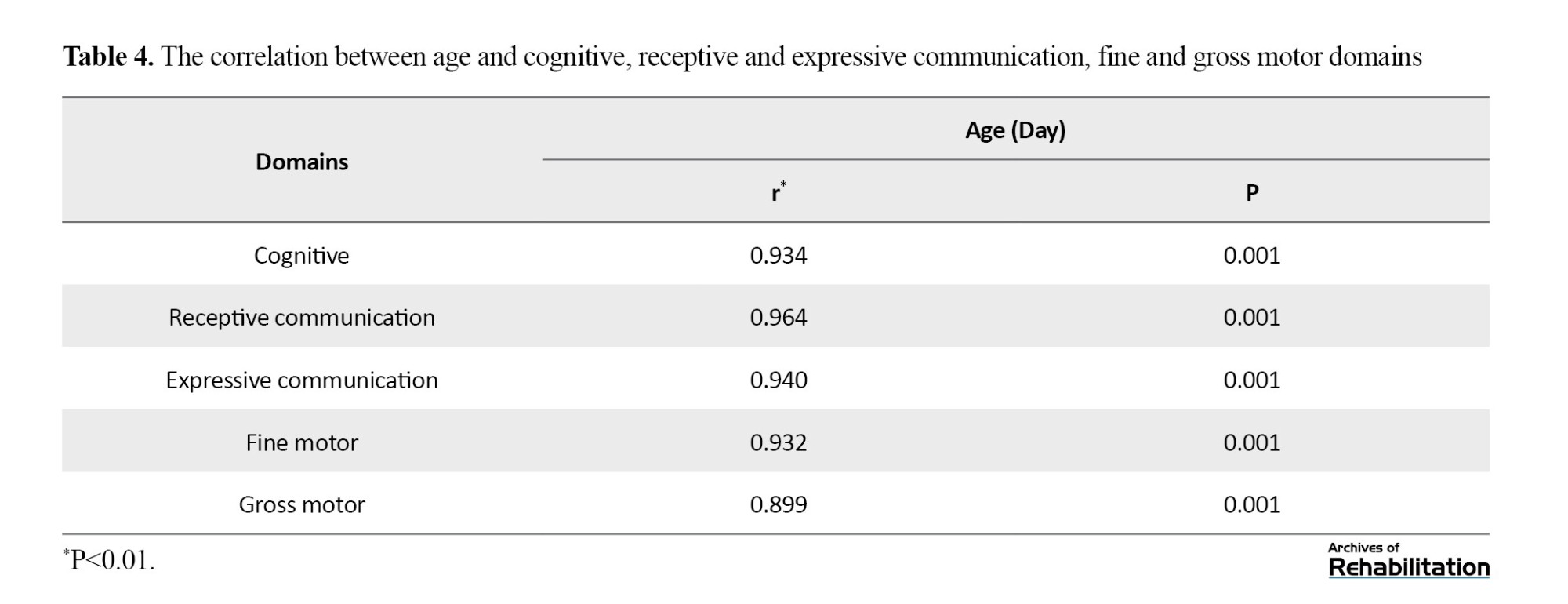

The Pearson correlation test was employed to determine the association between age and developmental domains. Table 4 represents the correlation of age with each domain. Based on the Pearson correlation analysis, age had a statistically significant direct correlation with each of the cognitive (r=0.93, P<0.01), receptive (r=0.96, P<0.01) and expressive communication (r=0.94, P<0.01), fine (r=0.92, P<0.01) and gross motors (r=0.90, P<0.01) domains.

Discussion

Although different stages of translation, re-translation, adaptation, and validity and reliability were performed in the standardization of the Bayley-III in the Persian language, the sequence of items was assessed in the present study, and it was determined whether the sequence of the Bayley-III is usable in Persian-language children. Various studies have demonstrated that different languages and cultures lead to developmental differences in children [1, 9], which besides the standardization of different scales, the order of the scales’ items should also be considered. Moreover, by knowing the exact developmental process in the assessment scales, a more precise treatment plan can be designed for children considering their culture and language.

The current study was conducted to assess the sequence of items of the Bayley-III. Similar to other developmental scales, the item sequence in this scale ranges from simple to difficult. Therefore, the test score for each child should gradually increase with increasing age, and the ability to respond to the items should gradually decrease at each age. In statistical assessments, if no descending trend is observed in the responses to the items, probably, the item is not located in the proper position. Also, if the three items at the starting point are easier than the previous items, the child’s performance may be estimated to be higher than the actual ability. Hence, assessing the starting point items is more important. The statistical analyses of the present research revealed that 41 items in the total scale had a deviant sequence and 27 deviant items located at the starting point. Among the 27 deviant items at the starting point, 14 items were easier than the previous items (the cognitive item No. 42, the receptive communication items No. 10, 20, and 24, the expressive communication items No. 3, 5, 10, 15, and 18, the fine motor items No. 24 and 39, and the gross motor items No. 20, 53 and 55), culminating in calculating higher ability in the child. Moreover, 13 deviant items were difficult items at the starting point, which, according to the test’s rule, caused no problems in calculating the child’s ability. Therefore, the lowest number of deviant items belonged to the cognitive area and the highest to the language area (receptive and expressive communication). Although in the standardization and adaptation stages, the appropriate items were selected based on the structure and sequence of the Persian language development [6], deviations were still observed in sequence, which could be attributed to the differences in the structures of different languages [2, 8, 12], as well as the shortage of resources to assess the Persian-language children’s developmental process. The comparison of the developmental outcomes of Tehran City, Iran, children with the national standard also indicated that the mean difference was greater in the language area (receptive and expressive communication) than in other domains [13].

The present results reveal that deviation in communication items occurred mostly at younger ages. Two possible factors are expected for this result. First, collecting data about the assessment of the developmental process in all languages, particularly in the Persian language, is more difficult at younger ages. In the Persian language, the only data available are parents’ reports, limited cross-sectional studies [14، 15] and longitudinal studies of one or two children [16، 17], which may not be in line with the general group of children. Second, children, particularly at younger ages, pay less attention to verbal stimuli in structured scales [18، 19], which may create deviations in the obtained results. Assessing deviant items in the language scale demonstrated that these items were at young ages and in pre-language communication ages. At a young age, the children’s developmental process is very quick and sometimes it is difficult to determine the exact order of these stages [20]. The results in the pre-language indicate differences in the sequence of items between the Persian language and the scale’s original version. For example, the repetitive combination of consonant and vowel items has gained a higher score compared to the previous using expressive movements item, and the correct use of words has gained a higher score compared to the previous starting interaction in the game. This can be due to the difference in the mother-child interactive style in Iranian culture compared to Western culture [14].

According to the results of Ashtari et al.’s study (2020), the communication style of Iranian mothers is of follow-in directive type [14], while the communication style of mothers in Western countries is supportive responsiveness [21، 22]. The interaction style in Iran is similar to other Asian countries [23-25]. In the follow-in directive method, the mother asks the child to do something or say something that she is currently paying attention to. In the supportive responsiveness method, the mother starts commenting, tagging, imitating, or encouraging the child based on the child’s present focus, which does not necessarily need a response [14]. Studies have demonstrated that the parent-child interactive style will influence the acquisition of expressive language and perception [14, 21, 26]. Therefore, the deviation in the mentioned items may be because Iranian mothers’ interactive style encourages children to respond verbally, and besides, mothers are often the initiators of the interaction and commence the questions. Thus, Iranian children may acquire the initiation of interaction later and begin using expressive language in communication more quickly.

In addition, although the adaptation and standardization of the Persian version of the Bayley-III scale in the motor skills domain have been adapted to the development process of Iranian children, the results showed that five items in the motor scale (fine and gross motor) deviate from the scale’s main process, which can be due to cultural and racial differences in the developmental process of motor skills [12، 27]. The secondary type of this study was one of its limitations because it was not possible to replace and re-assess the items on the same previous samples.

We recommended that developmental test developers pay enough attention to the sequence of items according to their intended culture and language based on the existing studies. On the other hand, it is recommended that the change in the sequence be carried out in future studies and the test’s revision. More precise cognitive, communication and motor development studies on children should also be conducted, particularly at younger ages, so that those studies can be used in adaptation and standardization.

Conclusion

According to the results, the entire sequence of Bayley III in the Persian language contains only 14 easy items in the starting points of the age groups. Given the small number of these items (n=14) compared to the total items of the scale (326 items), no effect was observed on the test result, and this version with the existing sequence is recommended for assessing the development of Persian-language children.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.142).

Funding

This article is extracted from the research project (No: 2887), Funded by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Farin Soleimani; Methodology: Farin Soleimani, Mohsen Vahedi, Zahra Babaiy and Fatemeh Hassanati; Analysis of sources and writing: Farin Soleimani, Fatemeh Hassanati and Zahra Babaiy; Editing and finalization: Zahra Nobakht, Zahra Ghorbanpour and Peymaneh Shirinbayan; Project management: Farin Soleimani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article are grateful for the financial support of the University of social welfare and rehabilitation sciences for this project. They are also grateful to Dr. Nadia Azari and Dr. Adis Kraskian, who participated in previous projects related to the Bayley scale in Iran.

The Bayley scale of infant and toddler development (Bayley III) is one of the global standard assessment tools for measuring early childhood development. This scale is used for clinical and research purposes in some countries [1]. However, some studies have demonstrated that the sequence of items and cut-off points of this scale, standardized for American children, may not be appropriate for non-American children [2-5]. These results denote the necessity of adaptation of developmental scales to various cultures. Studies in other countries have used the norms of the original version (the American norms), in which the cut-off points, the sequence of items and scoring results may not be appropriate for use in other populations [5-9]. Therefore, modifying the sequence of items, particularly in developmental scales, should be carried out following different communities regarding their language, culture, and demographic characteristics [7, 10].

According to the results regarding the adaptation of Bayley in the Dutch language, the development of motor abilities in Dutch children was slower than in American children, and children in any age group were two age steps behind in gross motor. The sequence of items was also assessed in comparison with the original version of the scale. The results demonstrated that the sequence of items in the Dutch language was not much different from that in the American version [10]. Hence, the appropriateness of the item sequence is one of the essential issues in the standardization of scales.

The Bayley-III scale is an individually administered tool for measuring the developmental performance of 1-42-month-old infants and toddlers. This scale is suitable for identifying children with developmental delays and helps the therapist design an appropriate treatment plan [1, 11]. This scale assesses the development of children in an observational manner in three cognitive, language (receptive and expressive communication) and motor (gross and fine) domains [1]. To perform the scale, the chronological age was adjusted for prematurity, and considering 17 age groups, the starting point was specified, then the test was done. Each starting point contains three main items, and if the child does not perform one of the three items of the starting point, the test goes back to a later age stage. Furthermore, the scale stops if the child does not respond to five consecutive items. Hence, the starting and stop points are decisive in the final score and, consequently, in determining the child’s ability. Assuming that the scale’s items are arranged based on the conventional developmental sequence in each environment, any item located after the stop point is assigned a score of zero and all the items located before the starting point are assigned a score of one. Therefore, based on the scale’s structure, the sequence of items considerably affects the child’s overall score [1].

Children of parents with different cultures, races, environments, education, socio-economic levels, and developmental backgrounds seem to acquire skills and abilities differently. Thus, based on these differences, the sequence of items of the original version of the Bayley-III scale in other countries may evaluate children’s abilities more or less than the actual level. Given the need to precisely assess the children’s early childhood development and the effect of various factors on developmental domains, including cognitive, motor and language areas, it is essential to determine the appropriateness or inappropriateness of the exact sequence of items for Persian-language children. Therefore, the current study investigates the appropriateness of the sequence of items for the Bayley-III scale in Persian-language children by specifying the number and location of items with deviations in cognitive, language and motor scales and its effect on the test’s final score.

Materials and Methods

This was a descriptive-analytical study of a secondary type, and the data on the psychometric properties of the Bayley-III have been utilized for the study. The Persian version of the Bayley-III has appropriate face and content validity [6]. Moreover, the validity was assessed through three methods internal consistency, test-re-test, and construct validity, using the factor analysis method and comparison of mean scores [6]. The mean Cronbach α coefficients for all scales are higher than 0.76 and the Pearson correlation coefficient in different sub-scales has been reported to be a minimum of 0.991 (P˂0.001) [6]. In the initial study, 404 children in 17 age groups were investigated by the Bayley-III. The children were selected using the convenience sampling method from the health centers of Tehran City, Iran, between 2013 and 2014. The inclusion criteria were being 1 to 42 months old, having normal development, and having the Persian language. The consent form was completed by the parents and the scale was administered by a trained examiner with a master’s degree in occupational therapy or psychology [6].

In this study, the sequence of items of the Bayley III for Persian-language children was assessed by determining the frequency and the number of individuals who gained a score of 1 in each item. The proportion of positive scores, which can vary between 0.00 and 1.00, was calculated for each item. As the difficulty of the items increases during the test, it is expected that a smaller number of individuals will get a score of 1 along the scale, and naturally, a larger number of individuals are expected to get a score of 1 at the beginning of the test. If the results are different, it indicates that the item is not located in the proper position and the sequence should be changed. Items diverging >0.05 in proportion to positive scores (either higher or lower) from the previous or following items in the sequence were denoted its deviation from the expected general pattern, and it was called a deviant item [1].

Therefore, First, deviant items were identified. Then, the location of these items in the sequence and whether the item is located at the starting point was specified because a deviant item located at the starting point can influence the child’s total score. If the score of a deviant item located at a starting point was over 0.05 less than the previous item, it demonstrated difficulty and was called a difficult item. However, the presence of this pattern does not significantly impact the test scores because, according to the reversal rule, the examiner should return to the lower starting point for the age group. Nonetheless, if the item had a positive deviation from the general pattern, it denoted the easy item in such a way that it received a score of >0.05 from the following items. In this case, the examiner did not use the reversal rule and according to the test instructions, since the individual’s score in all previous items would be considered positive, the child’s ability would be considered higher.

After identifying the deviant items, the percentage of children who scored 1 in that item was specified (the number of responses to the deviated item), followed by specifying the percentage of individuals who correctly responded to the item before (the number of responses in the previous item) and after (the number of responses in the following item) the deviant item. Furthermore, the difference between the items before and after (the amount of deviation) the deviant item was specified.

Hence, to do this, we calculated the mean scores of the items before and after the deviant item, the mean score of the deviant item, and the percentage of children of any age group who correctly responded to the deviant item. Furthermore, we specified to which age group the item was assigned and whether it was at a starting point or not. It was also determined that the item was difficult or easy. Additionally, after specifying the age groups to which the deviant item belonged, the percentage of individuals in that age group who correctly responded to the deviant item (the rate of transition from the deviated item according to the age group) was also specified. It was expected that this value would be <0.95 for difficult items and >0.95 for easy items.

Results

The participants in this study consisted of 404 Persian-language children (1-42-month-old) in 17 age groups, of which 51.5% were male. The lowest number of children (n=10) belonged to the age group E (4 months and 16 days to 5 months and 15 days), and the highest number (n=38) belonged to the age group D (3 months and 16 days and 4 months and 15 days).

The individuals’ positive scores were determined for each item. The number of individuals receiving positive scores in the sequence of items means the percentage of individuals in different age groups who successfully responded to each item and accomplished that item. The order of the Bayley III items, similar to other developmental scales, is such that by going forward in the scale, the ability to respond positively decreases and this share declines over time because the difficulty of the items is enhanced, which is normal. However, some items violate this sequence. Figure 1 shows the items in which a larger percentage of individuals did not follow the main sequence in various domains of the scale.

Subsequently, the deviant items were specified. The sequence of items was investigated in 404 children. The items were arranged from easy to difficult, and each item was assigned a score of 0.00 or 1.00. According to the scoring method of the scale, for each item, 404 scores (the number of participants) were available for analysis. The items where the decreased number of positive responses indicated the increased difficulty of the item, i.e. the item was difficult and fewer individuals responded to it. Overall, in this sequence, 41(13%) out of 326 items (the total number of scale items in 5 domains) deviated from their previous or following item by >0.05. On the cognitive scale, 7(8%) out of 91 items, in the receptive communication scale, 6(12%) out of 49 items, in the expressive communication scale, 9(19%) out of 48 items, in the fine motor scale, 10(15%) out of 66 items, and in the gross motor scale, 9(12.5%) out of 72 items deviated from the sequence of items (Table 2).

In addition, 27 out of 41 items were related to one of the 3 starting points, among which 9 items progressed based on the routine of the items’ getting difficult gradually (the cognitive item number No. 33, the expressive communication item No. 8, the fine motor items No. 20, 29, 36 and 37 and the gross motor items No. 17, 48 and 56). However, the degree of difference in the number of positive responses was >0.50. Four items were difficult according to the routine (cognitive item No. 46, fine motor items No. 33 and 38 and the gross motor item No. 54) and 14 items were easy (cognitive item No. 42, receptive communication items No. 10, 20, 24, the expressive communication items No. 3, 5, 10, 15 and 18, the fine motor items No. 24 and 39 and the gross motor items No. 20, 53, and 55) (Table 3).

Since the child’s total score will be problematic if the easy item is at the starting point, the characteristics of the items in the three starting points are provided in Table 3.

The Pearson correlation test was employed to determine the association between age and developmental domains. Table 4 represents the correlation of age with each domain. Based on the Pearson correlation analysis, age had a statistically significant direct correlation with each of the cognitive (r=0.93, P<0.01), receptive (r=0.96, P<0.01) and expressive communication (r=0.94, P<0.01), fine (r=0.92, P<0.01) and gross motors (r=0.90, P<0.01) domains.

Discussion

Although different stages of translation, re-translation, adaptation, and validity and reliability were performed in the standardization of the Bayley-III in the Persian language, the sequence of items was assessed in the present study, and it was determined whether the sequence of the Bayley-III is usable in Persian-language children. Various studies have demonstrated that different languages and cultures lead to developmental differences in children [1, 9], which besides the standardization of different scales, the order of the scales’ items should also be considered. Moreover, by knowing the exact developmental process in the assessment scales, a more precise treatment plan can be designed for children considering their culture and language.

The current study was conducted to assess the sequence of items of the Bayley-III. Similar to other developmental scales, the item sequence in this scale ranges from simple to difficult. Therefore, the test score for each child should gradually increase with increasing age, and the ability to respond to the items should gradually decrease at each age. In statistical assessments, if no descending trend is observed in the responses to the items, probably, the item is not located in the proper position. Also, if the three items at the starting point are easier than the previous items, the child’s performance may be estimated to be higher than the actual ability. Hence, assessing the starting point items is more important. The statistical analyses of the present research revealed that 41 items in the total scale had a deviant sequence and 27 deviant items located at the starting point. Among the 27 deviant items at the starting point, 14 items were easier than the previous items (the cognitive item No. 42, the receptive communication items No. 10, 20, and 24, the expressive communication items No. 3, 5, 10, 15, and 18, the fine motor items No. 24 and 39, and the gross motor items No. 20, 53 and 55), culminating in calculating higher ability in the child. Moreover, 13 deviant items were difficult items at the starting point, which, according to the test’s rule, caused no problems in calculating the child’s ability. Therefore, the lowest number of deviant items belonged to the cognitive area and the highest to the language area (receptive and expressive communication). Although in the standardization and adaptation stages, the appropriate items were selected based on the structure and sequence of the Persian language development [6], deviations were still observed in sequence, which could be attributed to the differences in the structures of different languages [2, 8, 12], as well as the shortage of resources to assess the Persian-language children’s developmental process. The comparison of the developmental outcomes of Tehran City, Iran, children with the national standard also indicated that the mean difference was greater in the language area (receptive and expressive communication) than in other domains [13].

The present results reveal that deviation in communication items occurred mostly at younger ages. Two possible factors are expected for this result. First, collecting data about the assessment of the developmental process in all languages, particularly in the Persian language, is more difficult at younger ages. In the Persian language, the only data available are parents’ reports, limited cross-sectional studies [14، 15] and longitudinal studies of one or two children [16، 17], which may not be in line with the general group of children. Second, children, particularly at younger ages, pay less attention to verbal stimuli in structured scales [18، 19], which may create deviations in the obtained results. Assessing deviant items in the language scale demonstrated that these items were at young ages and in pre-language communication ages. At a young age, the children’s developmental process is very quick and sometimes it is difficult to determine the exact order of these stages [20]. The results in the pre-language indicate differences in the sequence of items between the Persian language and the scale’s original version. For example, the repetitive combination of consonant and vowel items has gained a higher score compared to the previous using expressive movements item, and the correct use of words has gained a higher score compared to the previous starting interaction in the game. This can be due to the difference in the mother-child interactive style in Iranian culture compared to Western culture [14].

According to the results of Ashtari et al.’s study (2020), the communication style of Iranian mothers is of follow-in directive type [14], while the communication style of mothers in Western countries is supportive responsiveness [21، 22]. The interaction style in Iran is similar to other Asian countries [23-25]. In the follow-in directive method, the mother asks the child to do something or say something that she is currently paying attention to. In the supportive responsiveness method, the mother starts commenting, tagging, imitating, or encouraging the child based on the child’s present focus, which does not necessarily need a response [14]. Studies have demonstrated that the parent-child interactive style will influence the acquisition of expressive language and perception [14, 21, 26]. Therefore, the deviation in the mentioned items may be because Iranian mothers’ interactive style encourages children to respond verbally, and besides, mothers are often the initiators of the interaction and commence the questions. Thus, Iranian children may acquire the initiation of interaction later and begin using expressive language in communication more quickly.

In addition, although the adaptation and standardization of the Persian version of the Bayley-III scale in the motor skills domain have been adapted to the development process of Iranian children, the results showed that five items in the motor scale (fine and gross motor) deviate from the scale’s main process, which can be due to cultural and racial differences in the developmental process of motor skills [12، 27]. The secondary type of this study was one of its limitations because it was not possible to replace and re-assess the items on the same previous samples.

We recommended that developmental test developers pay enough attention to the sequence of items according to their intended culture and language based on the existing studies. On the other hand, it is recommended that the change in the sequence be carried out in future studies and the test’s revision. More precise cognitive, communication and motor development studies on children should also be conducted, particularly at younger ages, so that those studies can be used in adaptation and standardization.

Conclusion

According to the results, the entire sequence of Bayley III in the Persian language contains only 14 easy items in the starting points of the age groups. Given the small number of these items (n=14) compared to the total items of the scale (326 items), no effect was observed on the test result, and this version with the existing sequence is recommended for assessing the development of Persian-language children.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.142).

Funding

This article is extracted from the research project (No: 2887), Funded by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Farin Soleimani; Methodology: Farin Soleimani, Mohsen Vahedi, Zahra Babaiy and Fatemeh Hassanati; Analysis of sources and writing: Farin Soleimani, Fatemeh Hassanati and Zahra Babaiy; Editing and finalization: Zahra Nobakht, Zahra Ghorbanpour and Peymaneh Shirinbayan; Project management: Farin Soleimani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors of this article are grateful for the financial support of the University of social welfare and rehabilitation sciences for this project. They are also grateful to Dr. Nadia Azari and Dr. Adis Kraskian, who participated in previous projects related to the Bayley scale in Iran.

Refrences

- Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant and toddler development, third edition. San Antonio: Pearson Clinical Assessment; 2006. [DOI:10.1037/t14978-000]

- Walker K, Badawi N, Halliday R, Laing S. Brief report: Performance of Australian children at one year of age on the Bayley scales of infant and toddler development (version III). The Educational and Developmental Psychologist. 2010; 27(1):54-8. [DOI:10.1375/aedp.27.1.54]

- Krogh MT, Væver MS, Harder S, Køppe S. Cultural differences in infant development during the first year: A study of Danish infants assessed by the Bayley-III and compared to the American norms. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2012; 9(6):730-6. [DOI:10.1080/17405629.2012.688101]

- Vierhaus M, Lohaus A, Kolling T, Teubert M, Keller H, Fassbender I, et al. The development of 3-to 9-month-old infants in two cultural contexts: Bayley longitudinal results for Cameroonian and German infants. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2011; 8(3):349-66. [DOI:10.1080/17405629.2010.505392]

- Yu YT, Hsieh WS, Hsu CH, Chen LC, Lee WT, Chiu NC, et al. A psychometric study of the bayley scales of infant and toddler development-3rd edition for term and preterm Taiwanese infants. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2013; 34(11):3875-83. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2013.07.006] [PMID]

- Wu YT, Tsou KI, Hsu CH, Fang LJ, Yao G, Jeng SF. Brief report: Taiwanese infants’ mental and motor development-6-24 months. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008; 33(1):102-8. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm067]

- Godamunne P, Liyanage C, Wimaladharmasooriya N, Pathmeswaran A, Wickremasinghe AR, Patterson C, et al. Comparison of performance of Sri Lankan and US children on cognitive and motor scales of the Bayley scales of infant development. BMC Research Notes. 2014; 7(1):1-5. [DOI:10.1186/1756-0500-7-300]

- Azari N, Soleimani F, Vameghi R, Sajedi F, Shahshahani S, Karimi H, et al. A Psychometric study of the bayley scales of infant and toddler development in Persian language children. Iranian Journal of Child Neurology. 2017; 11(1):50-56. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Krogh MT, Væver MS. Bayley-III: Cultural differences and language scale validity in a Danish sample. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. 2016; 57(6):501-8. [DOI:10.1111/sjop.12333]

- Steenis LJ, Verhoeven M, Hessen DJ, van Baar AL. First steps in developing the Dutch version of the Bayley III: Is the original Bayley III and its item sequence also adequate for Dutch children?. European Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2014; 11(4):494-511. [DOI:10.1080/17405629.2013.869207]

- Soleimani F, Azari N, Vameghi R, Barekati SH, Lornejad H, Kraskian A. [Standardization of the bayley scales of infant and toddler development for Persian children (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2022; 23(1):8-31. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.23.1.42.4]

- Kelly Y, Sacker A, Schoon I, Nazroo J. Ethnic differences in achievement of developmental milestones by 9 months of age: The millennium cohort study. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2006; 48(10):825-30. [DOI:10.1017/S0012162206001770]

- Soleimani F, Azari N, Kraskian A, Karimi H, Sajedi F, Vameghi R, et al. A Comparison study of the tehran norms to the reference norms on children performance of the Bayley III. Iran J Child Neurol. 2022; 16(2):63-76. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ashtari A, Samadi SA, Yadegari F, Ghaedamini Harooni G. The relationship between Iranian maternal verbal responsiveness styles and child’s communication acts with expressive and receptive vocabulary in 13-18 months old typically developing children. Early Child Development and Care. 2020; 190(15):2392-401. [DOI:10.1080/03004430.2019.1573227]

- Bayat N, Ashtari A, Vahedi M. The early prelinguistic skills in Iranian infants and toddlers. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2021; 19(4):441-54. [DOI:10.32598/irj.19.4.1605.1]

- Jalilevand N, Ebrahimipur M, Purqarib J. [Mean length of utterance and grammatical morphemes in speech of two Farsi-speaking children (Persian)]. Audiology. 2012; 21(2):96-108. [Link]

- Kazemi Y, Nematzadeh S, Hajian T, Heidari M, Daneshpajouh T, Mirmoeini A. [The validity and reliability coefficient of persian translated mcarthur-bates communicative development inventory (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Rehabilitation Sciences. 2008; 4(1). [DOI:10.22122/jrrs.v4i1.29]

- Yoon JA, An SW, Choi YS, Seo JS, Yoon SJ, Kim SY, et al. Correlation of language assessment batteries of toddlers with developmental language delay. Annals of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2022; 46(5):256-62. [DOI:10.5535/arm.22045]

- Nilipour R, Qoreishi ZS, Ahadi H, Pourshahbaz A. [Development and standardization of persian language developmental battery (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2023; 24(2):172-95. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.24.2.2191.5]

- Steenis LJ, Verhoeven M, Hessen DJ, Van Baar AL. Parental and professional assessment of early child development: The ASQ-3 and the Bayley-III-NL. Early Human Development. 2015; 91(3):217-25. [DOI:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2015.01.008]

- Walton KM, Ingersoll BR. The influence of maternal language responsiveness on the expressive speech production of children with autism spectrum disorders: A microanalysis of mother-child play interactions. Autism. 2015; 19(4):421-32. [DOI:10.1177/1362361314523144]

- Bornstein MH, Britto PR, Nonoyama-Tarumi Y, Ota Y, Petrovic O, Putnick DL. Child development in developing countries: Introduction and methods. Child Development. 2012; 83(1):16-31. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01671.x]

- Johnston JR, Wong MY. Cultural differences in beliefs and practices concerning talk to children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2002; 45(5):916-26. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2002/074)]

- Baharudin R, Keshavarz R. Parenting style in a collectivist culture of Malaysia. European Journal of Social Sciences. 2009; 10(1):66-73. [Link]

- Diken IH, Diken O. Turkish mothers' verbal interaction practices and self-efficacy beliefs regarding their children with expressive language delay. International Journal of Special Education. 2008; 23(3):110-7. [Link]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bornstein MH, Baumwell L. Maternal responsiveness and children’s achievement of language milestones. Child Development. 2001; 72(3):748-67. [DOI:10.1111/1467-8624.00313]

- Duncan AF, Watterberg KL, Nolen TL, Vohr BR, Adams-Chapman I, Das A, et al. Effect of ethnicity and race on cognitive and language testing at age 18-22 months in extremely preterm infants. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2012; 160(6):966-71.e2. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.12.009]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Pediatric Neurology

Received: 25/12/2023 | Accepted: 22/07/2024 | Published: 1/11/2024

Received: 25/12/2023 | Accepted: 22/07/2024 | Published: 1/11/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |