Volume 25, Issue 3 (Autumn 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(3): 500-519 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Telicani F, Khademi Kalantari K, Rahimi A, Akbarzadeh Baghban A, Omidian M M, Daryabor A. Relationship Between Psychological and Clinical Outcomes of 12-Week Therapeutic Exercises Following Total Knee Arthroplasty. jrehab 2024; 25 (3) :500-519

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3366-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3366-en.html

Fariba Telicani1

, Khosro Khademi Kalantari *2

, Khosro Khademi Kalantari *2

, Abbas Rahimi1

, Abbas Rahimi1

, Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban3

, Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban3

, Mohammad Mahdi Omidian4

, Mohammad Mahdi Omidian4

, Aliyeh Daryabor5

, Aliyeh Daryabor5

, Khosro Khademi Kalantari *2

, Khosro Khademi Kalantari *2

, Abbas Rahimi1

, Abbas Rahimi1

, Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban3

, Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban3

, Mohammad Mahdi Omidian4

, Mohammad Mahdi Omidian4

, Aliyeh Daryabor5

, Aliyeh Daryabor5

1- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,khosro_khademi@yahoo.co.uk

3- Department of Biostatistics, Proteomics Research Center, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Orthopedics, School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, Physiotherapy Research Center, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Physiotherapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Biostatistics, Proteomics Research Center, School of Allied Medical Sciences, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Orthopedics, School of Medicine, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, Physiotherapy Research Center, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Physiotherapy, Psychological factors, Total knee arthroplasty (TKA), Pain, Range of motion (ROM), Functional ability

Full-Text [PDF 3213 kb]

(900 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6246 Views)

Full-Text: (1391 Views)

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is recommended for severe and advanced knee osteoarthritis patients. This therapeutic procedure reduces pain intensity and improves the knee joint’s functional ability [1]. Although most patients achieve significant pain reduction and functional improvement after the procedure, about 15% to 25% report no satisfactory improvement in pain and quality of life (QoL) [2, 3]. Several factors can influence the results of TKA, including the surgical method and the type of prosthesis used [4]. Some previous studies have also suggested demographics (age, gender, and body mass index) clinical and psychological factors [5, 6].

It has been shown that patients who suffer from severe pain for a long time have an increased risk of developing psychological problems [7, 8]. These psychological problems may manifest themselves in anxiety and depression. In patients who are exposed to psychological problems, the perception of pain is closely related to their psychological status. For example, people who exhibit symptoms of depression report more pain both before and after surgery [7].

Psychological factors play an essential role in the clinical outcomes of patients after various types of orthopedic surgery [9]. Several studies have also reported that psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing are among the predictors of patient dissatisfaction after TKA [10-13]. A review study indicated that anxiety is one of the main factors associated with poor outcomes after TKA [5]. However, there is conflicting evidence on the role of psychological factors such as depression [14] and anxiety [14-16] in predicting clinical outcomes after surgery. Kinesiophobia, i.e. fear of physical movement, with the idea that movement may lead to pain and injury [17, 18], is a risk factor in predicting the outcome of TKA [19-21].

Pain depends not only on its intensity but also on the patient’s interpretation of the pain. Pain catastrophizing with self-report of pain intensity and duration is considered a modifiable risk factor for predicting the outcomes of a TKA. Pain catastrophizing is a negative variable that results in people being unable to control their pain because they feel helpless and overly reinforce their cognitions related to the painful processes [22]. Lungu et al. found that the higher the person’s score on the pre-surgery pain catastrophizing questionnaire, the greater the pain and disability one year after surgery [5]. However, Birch et al. showed that the group with a higher score on the pain catastrophizing questionnaire made greater progress in gaining functional ability after TKA [23].

Considering that rehabilitation treatment after TKA requires patients’ cooperation, psychological problems can have a negative impact on the outcome of rehabilitation, e.g. subsequent physiotherapy, leading to reports of dissatisfaction reports after this procedure [7]. On the other hand, few studies have investigated the relationship between the fear of movement and clinical outcomes of TKA. Despite the studies investigating the relationship between psychological factors before TKA and clinical outcomes after surgery, to our knowledge, no clear evidence proves this relationship. In the studies conducted, patients were often examined by telephone or virtually and without time monitoring, and no attention was paid to the process they underwent during the study, especially concerning therapeutic exercises after TKA. Perhaps one of the reasons for the inconsistencies is that most studies did not mention the rehabilitation process of patients with psychological problems and physical therapy steps after surgery. However, this process can play an important role in the clinical outcomes of these patients. For example, in a study examining the correlation between depression and anxiety with outcomes of TKA, it was found that not only depression and anxiety are related to surgical outcomes but also that the level of depression and anxiety decreased 6 weeks following surgery. The severity of the patient’s psychological symptoms decreases as their abilities improve. Therefore, they do not consider depression and anxiety as contraindications for surgery [7]. On the other hand, both aerobic and resistance exercise have been reported effective in treating depression, and the effect of aerobic exercise therapy was equivalent to therapeutic-psychological interventions in the treatment of depression [24]. There is also evidence that therapeutic exercise improves psychological status in cancer patients [25, 26] and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction [27].

Studies investigating the effect of therapeutic exercise after TKA have reported that exercise can significantly improve clinical outcomes in these patients [28]. However, few studies have investigated the effect of exercise therapy on the severity of psychological problems following this surgery. In a previous study, the impact of physical therapy, including functional exercises and theoretical information on how to deal with the fear of movement after TKA, was investigated, and the results showed that the interventions effectively improved this outcome [29]. However, no study has been conducted to show whether only therapeutic exercises without psychological interventions can improve psychological factors after TKA. Therefore, this study investigated the relationship between psychological characteristics and clinical outcomes of therapeutic exercise after 12 weeks. Another aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of 12 weeks of therapeutic exercise on patients’ psychological characteristics.

Materials and Methods

Study participants

In this quasi-experimental study, 29 female patients who were candidates for TKA for their first knees and had been referred to the orthopedic department of Imam Hossein Hospital were examined by the researcher on the day of admission with the prior coordination of the orthopedic surgeon. If the inclusion and exclusion criteria were met, the steps of the study were explained to them. If the individuals were willing to cooperate further, they signed the written informed consent form. The inclusion criteria for this study were women eligible for TKA for their first knees who could speak, read, and write in Persian. The exclusion criteria included lack of cooperation during the study, damage to the prosthesis after an injury, joint infection after surgery, and prosthesis in the lower extremity on the surgical side. All patients underwent TKA with American Zimmer Biomet prosthesis with posterior cruciate ligament retained by one surgeon.

Study tools

The following tools were used to assess the clinical outcomes of patients.

Visual analog scale

This scale was used to assess pain intensity at rest and during activity. This scale consists of a 100 mm straight line with the words “no pain” on one side and “worst pain imaginable” on the other. Participants are instructed to make a mark on the line indicating the pain level they are experiencing during the evaluation. Its validity and reliability are acceptable in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain [30]. To rate the pain at rest, patients were asked to mark on the line how they felt it in the last week. Patients were asked to walk for 6 minutes to measure pain intensity during activity and then mark on the line.

Goniometer

In this study, Rahavard Mehr’s Iranian goniometer was used to determine the active range of motion (ROM) of knee flexion and extension. To measure the knee flexion, which was performed in the supine position with the hip flexed, the center of the goniometer was on the lateral condyle of the femur, the fixed arm was aligned with the lateral condyle of the femur and its longitudinal axis, and the movable arm was aligned with the lateral malleus and the longitudinal axis of the tibia. The individual was asked to flex their knee actively, and the ROM was recorded. To measure knee extension, the person’s knee was brought into the extension position as far as possible, and the goniometer was placed the same way as when measuring knee flexion.

Oxford knee score (OKS)

The 12-item OKS self-report questionnaire was used to check patients’ functional ability, which examines various dimensions of knee pain and function after TKA. This questionnaire is scored based on 5 items (0: Most disability, 4: Least disability) according to the condition reported by the patient. The total score ranges from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating higher functional ability. The Persian version of this questionnaire has good validity and reliability [31]. The patients’ psychological indicators were assessed using the following tools.

Beck depression inventory (BDI) II

To assess the intensity of depression, the updated 21-item BDI II questionnaire was utilized. The questionnaire is scored based on four answer choices, with a value ranging from 0 to 3, depending on the severity reported by the patient. The Persian version of this questionnaire has satisfactory psychometric properties [32].

State trait anxiety index (STAI)

This questionnaire was used to assess “state” and “trait” anxiety. It was standardized for the Iranian population with a high validity and reliability [33]. This 40-item questionnaire comprises two sections, each with 20 questions: Trait anxiety and state anxiety. While answering the state anxiety scale, respondents are asked to consider their present feelings, whereas when responding to the trait anxiety scale, they should report their usual and consistent feelings. The total scores of the trait and state anxiety scales range from 20 to 80. Scoring higher on the anxiety test indicates a greater level of anxiety. A score of 40 and above for the state section of the questionnaire indicates that the person is currently experiencing high anxiety [34].

Pain catastrophizing scale (PCS)

PCS is a 13-item self-report questionnaire to assess catastrophic thoughts and behaviors related to pain [35]. The questionnaire asks individuals to rate the degree to which they have experienced past painful thoughts and feelings on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0: Never to 4: Always. This scale’s Persian version has been found reliable in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain [36].

Tampa scale of kinesiophobia (TSK)

This scale measures the fear of painful movement, physical activity, and re-injury. It consists of a self-report checklist with 17 items, using a 4-point Likert scale (1: Strongly disagree and 4: Strongly agree), with a maximum score of 68. A higher score indicates greater kinesiophobia related to movements and re-injury [37].

Intervention and procedure

During this study, which lasted for 12 weeks, patients performed therapeutic exercises under the supervision of a physiotherapist. One day before the surgery, the physiotherapist measured the intensity of the patient’s knee pain at rest during the last week and during activity immediately after a 6-minute walking test. Additionally, the physiotherapist measured the patients’ active flexion and extension ROM of the knee. Patients also filled out questionnaires related to psychological indicators and functional ability.

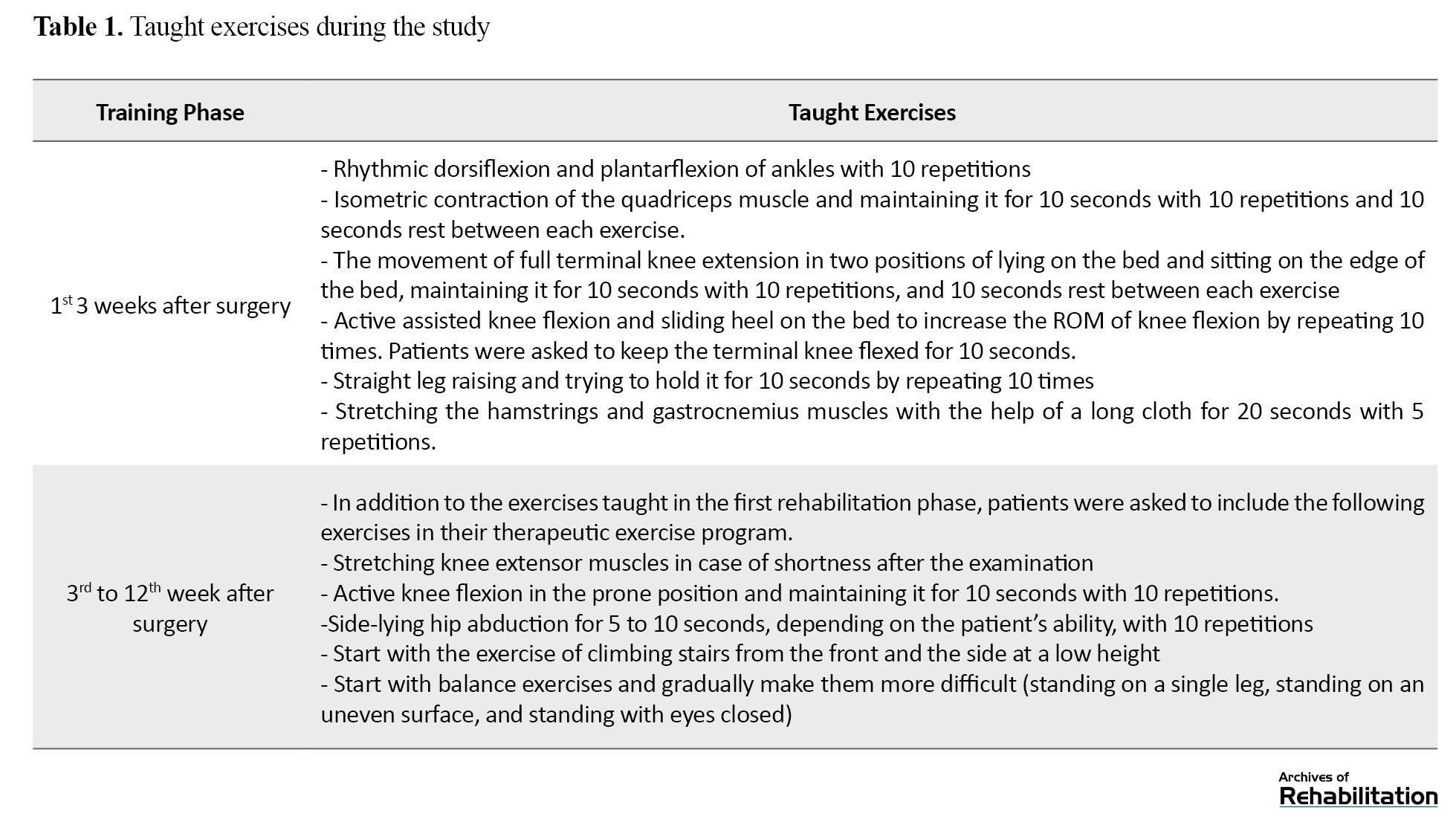

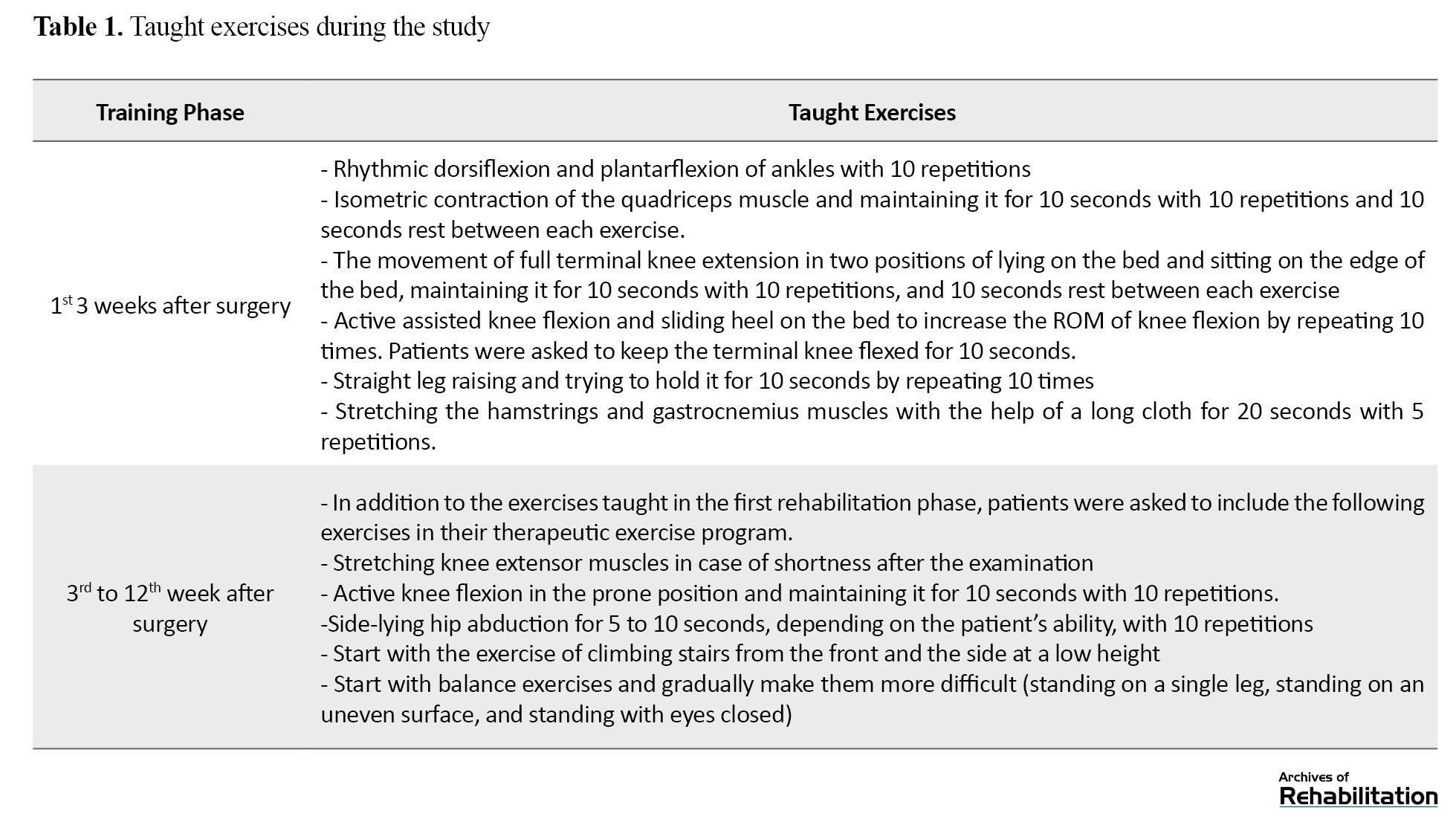

Individuals who underwent TKA were subjected to a standard exercise program during one session the day after their surgery [38]. The therapeutic exercises were performed in the first 3 weeks post-surgery, emphasizing restoring the ROM of 90-degree flexion and 0-degree extension and muscle strength around the knee. The exercises included rhythmic dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the ankle (ankle pumping exercise) to control swelling of the leg and prevent clots, sliding heel on the bed and wall, quadriceps setting exercise, terminal knee extension, active assisted knee flexion, straight leg raising exercise, and stretching of the hamstrings and gastrocnemius muscles. Patients were instructed to perform each exercise daily in 4 sets (every 3-4 hours) of 10 repetitions (Table 1).

These exercises lasted about 30 minutes each time. Educational brochures were also given to patients outlining the exercise.

To control pain and swelling, patients were taught to use a cold compress on their knee for 15 minutes every 3-4 hours for 6 weeks [39]. After teaching the exercises, the physiotherapist re-measured the knee’s active flexion and extension ROM one day after the surgery (Figure 1).

The therapist then evaluated the pain intensity at rest.

After the stitches were removed at the end of the third week, the second phase of exercises began. This phase aimed to achieve knee ROM between 90-125 degrees, reduce pain and swelling, improve balance, and promote independence. To achieve these goals, hamstring curls and hip abductions were added to the exercise plan used in the first phase.

At the end of the 12th week, the patients were asked to complete all questionnaires. The pain intensity at rest and during activity and knee ROM were re-examined. After being discharged from the hospital until the end of the study period, the patients remained in virtual communication with their therapist. The physiotherapist regularly checked the patients’ ROM and exercises by reviewing photos and videos sent by the patients. This virtual communication was maintained once every three days for the first three weeks after surgery and weekly throughout the remainder of the study. Throughout the 12 week treatment period, the patients were evaluated and treated by one physiotherapist, unaware of the score of the psychological indicators.

Statistical analysis

To investigate the correlation between quantitative variables, we used the Pearson and partial correlation coefficient (to control the confounding effect of age and body mass index) based on the normality of data distribution. For comparing patients’ psychological characteristics before surgery and after physical therapy, we checked the normality of data distribution via the Shapiro-Wilk test. Next, we used the paired t-test to compare two conditions. We conducted the statistical analysis of data using SPSS software, version 25 at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

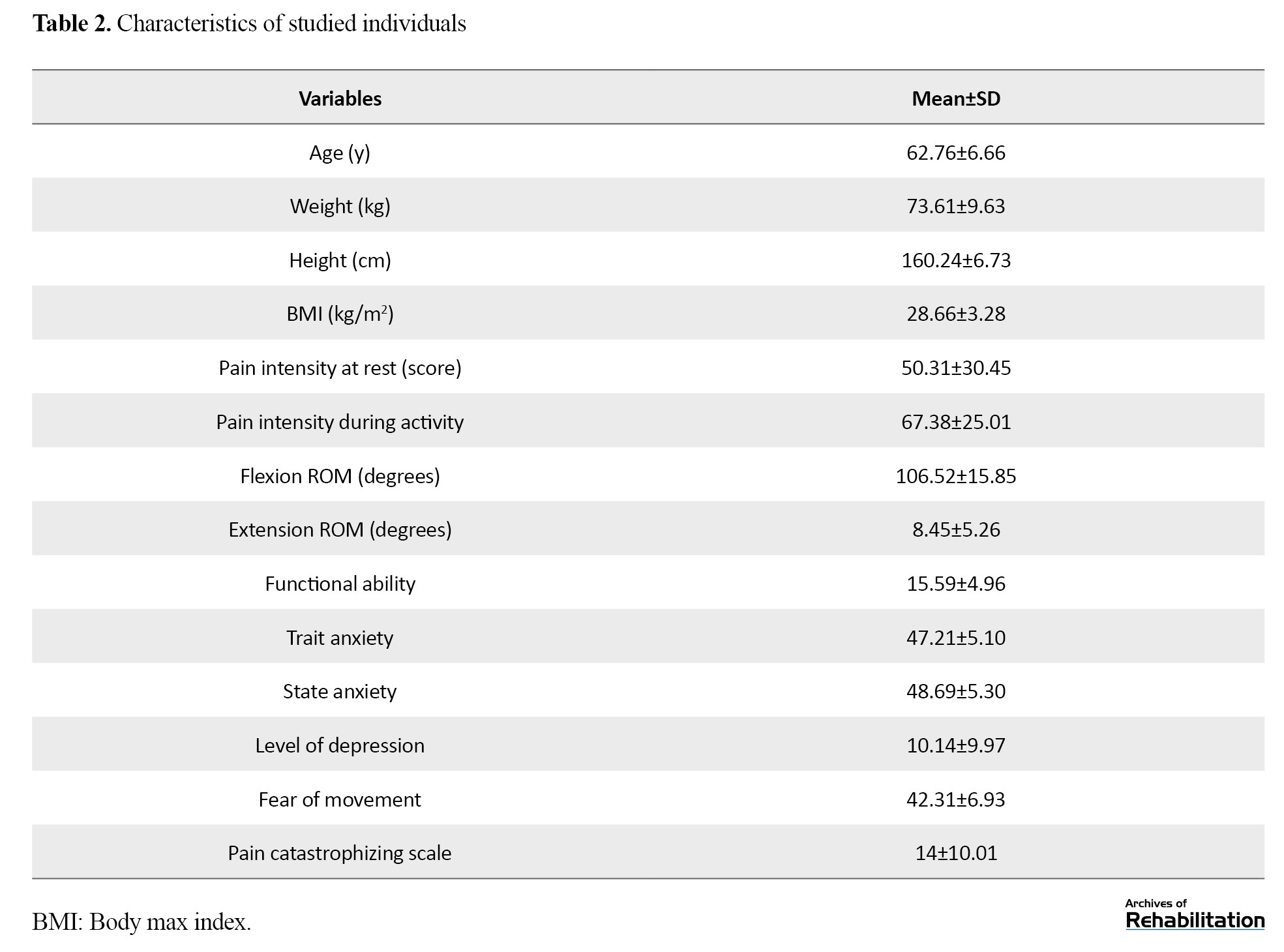

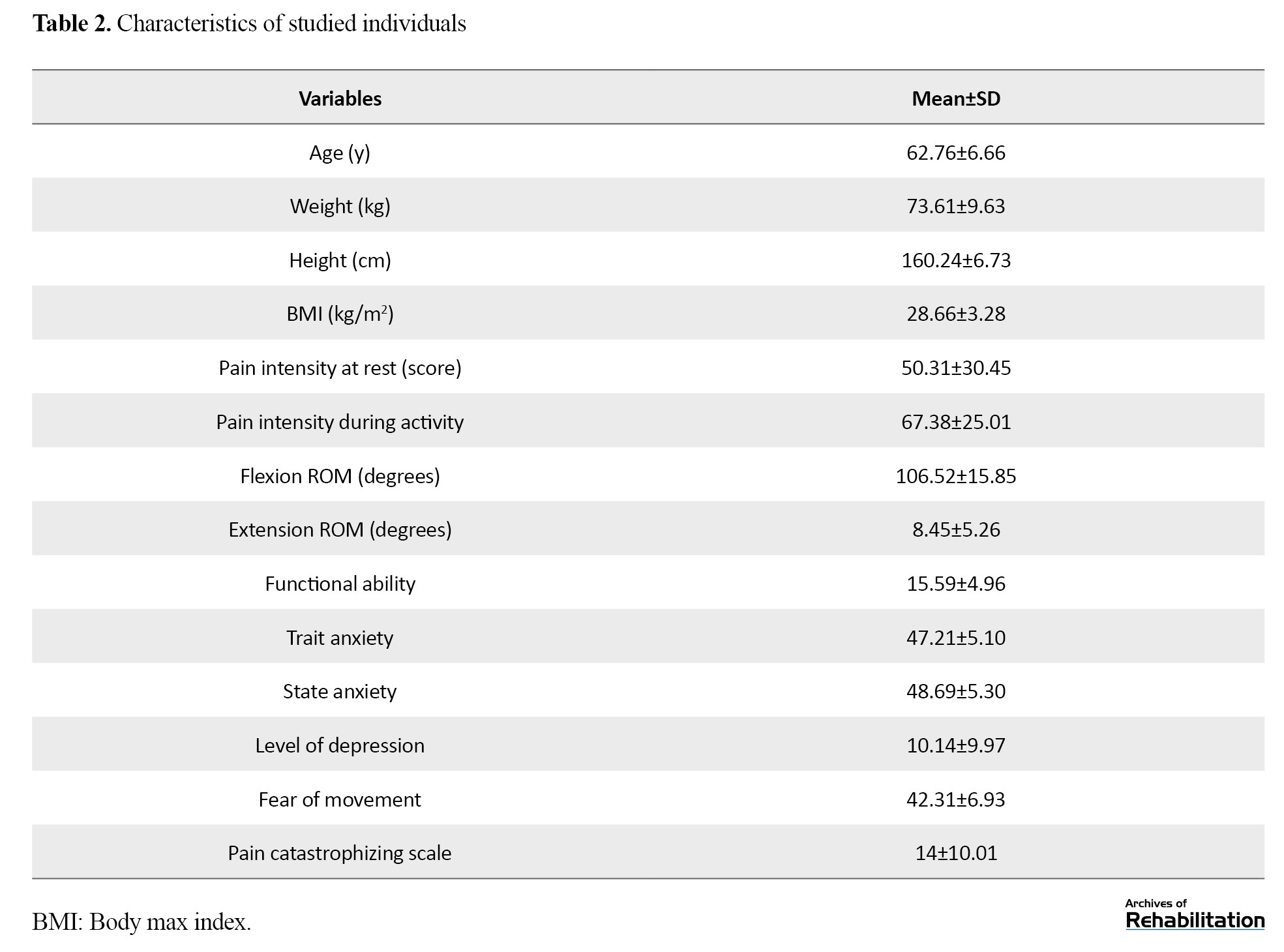

In this study, 29 female patients who had undergone unilateral TKA and had an average age of 62.76 years were analyzed. Table 2 provides a summary of the participants’ characteristics at the beginning of the research.

Effect of therapeutic exercise on psychological factors

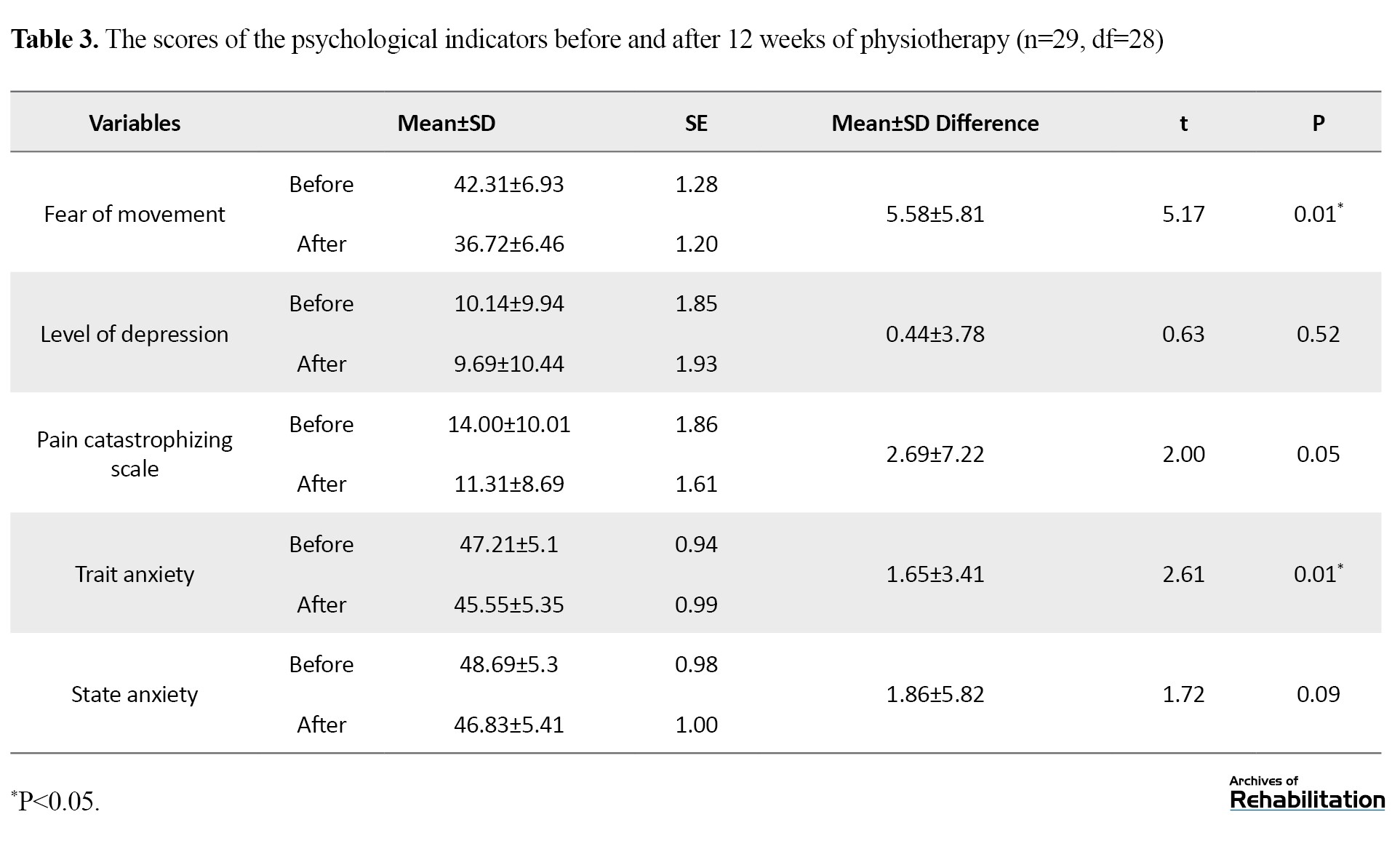

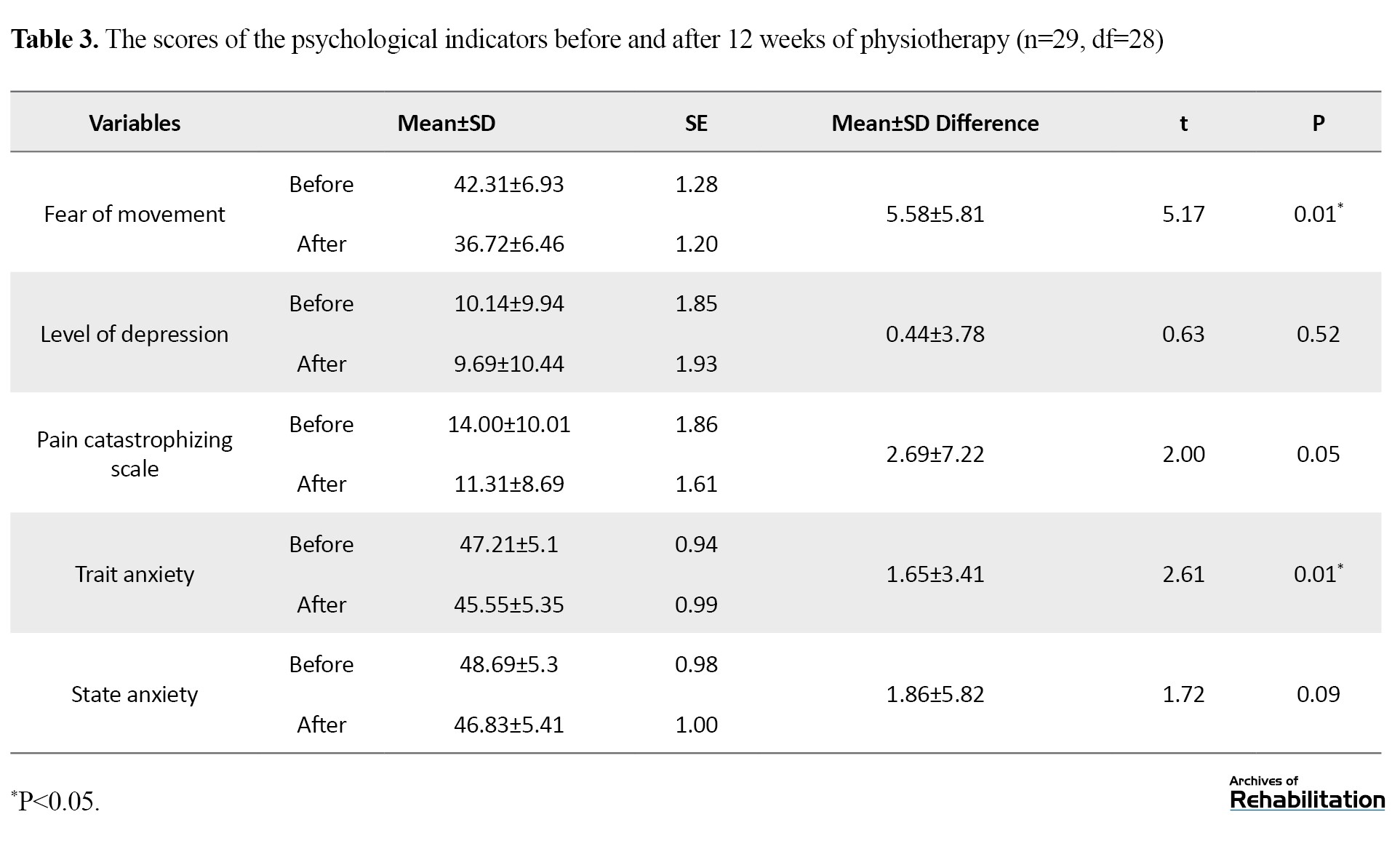

The results showed that 12 week therapeutic exercise after TKA had a significant effect on reducing psychological problems, including fear of movement (P=0.01) and trait anxiety (P=0.01). The statistical indicators of these scores before surgery and after 12 week therapeutic exercise are shown in Table 3.

Relationship between psychological factors and clinical outcomes

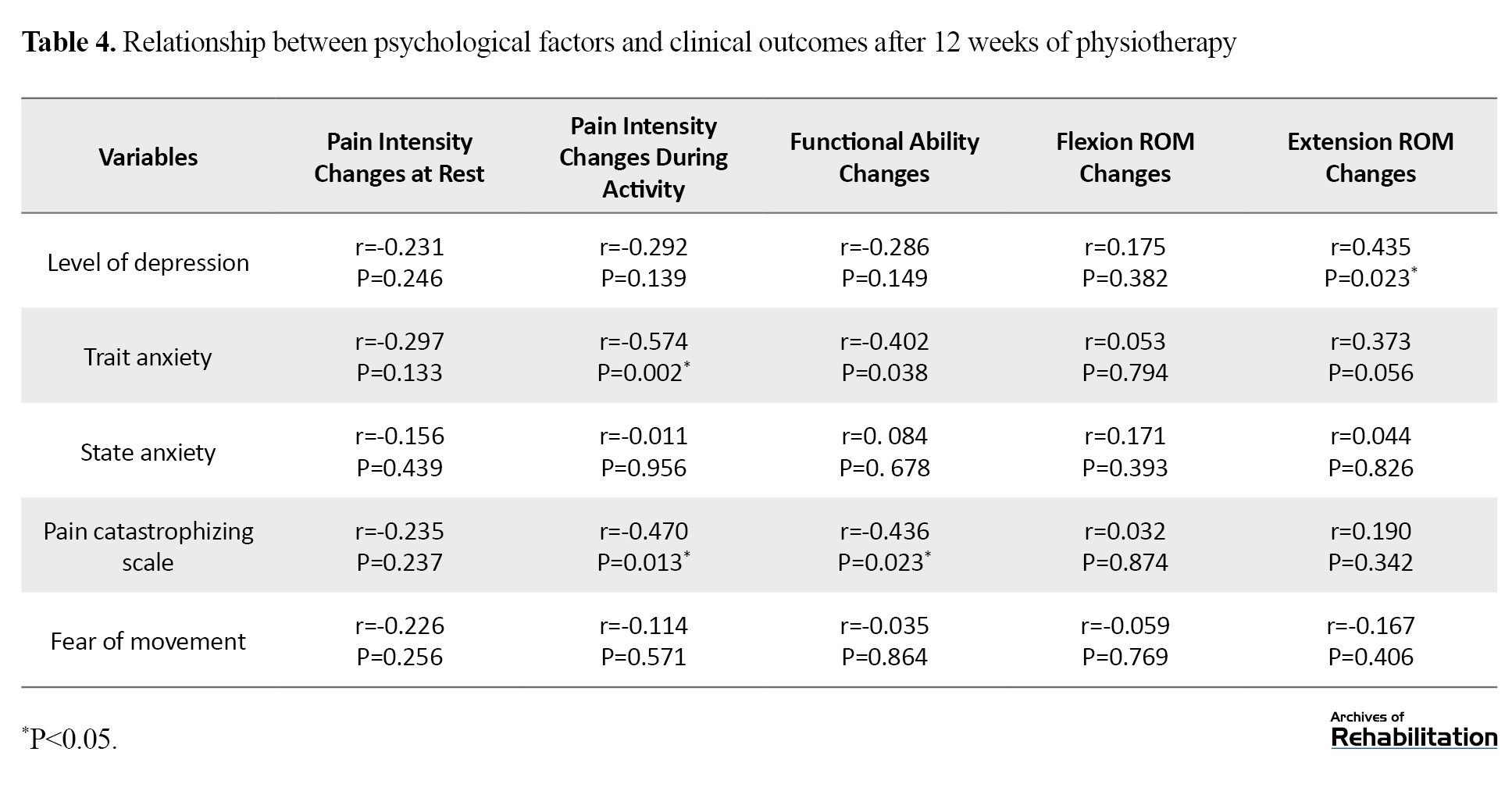

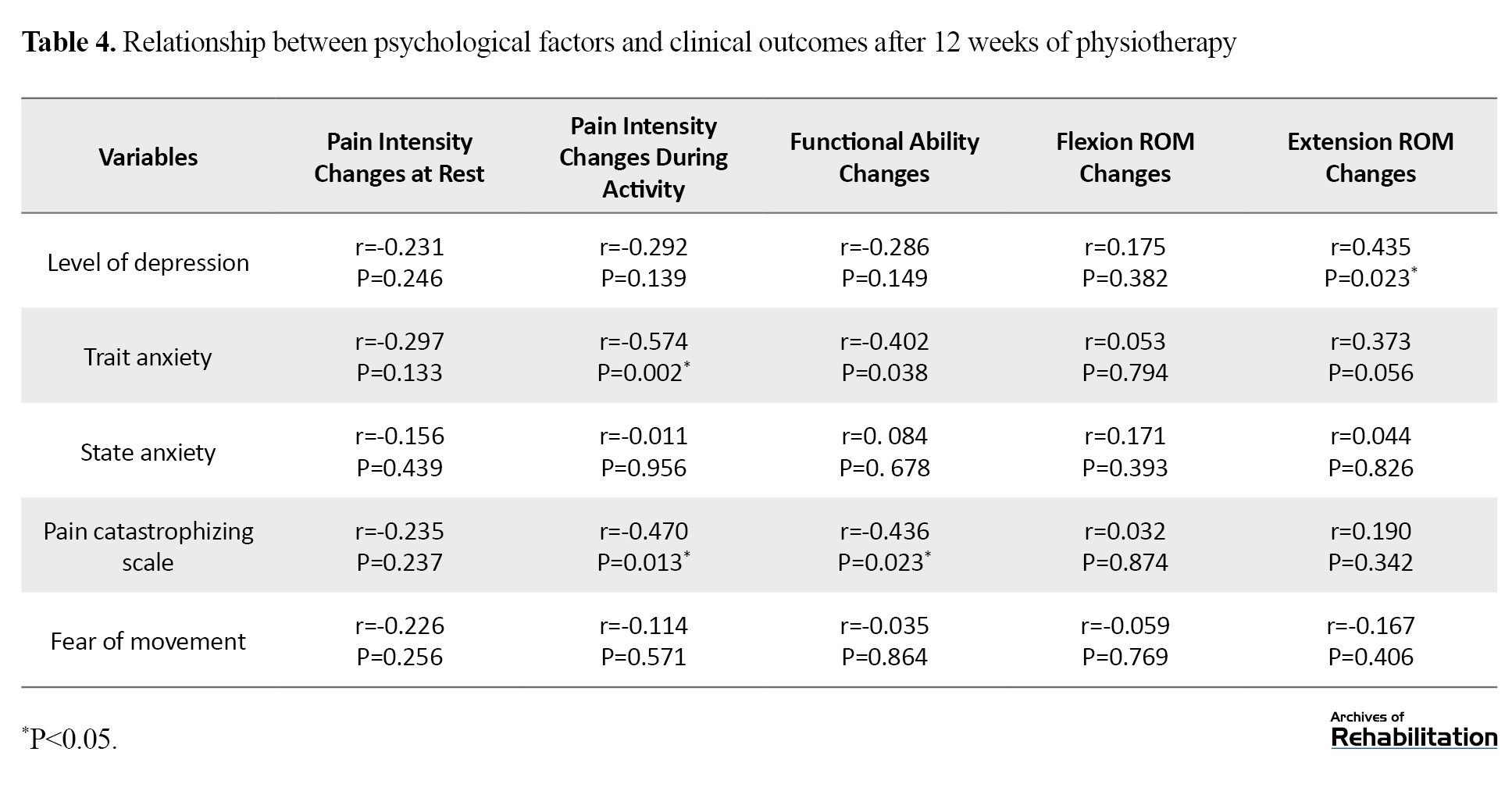

Table 4 presents the correlation between pre-surgery psychological factors and changes in pain intensity, flexion and extension ROM, and functional ability following 12 weeks of therapeutic exercises.

According to the findings, there was a significant correlation between pre-surgery depression and decreased extension ROM of the knee (r=0.435, P=0.023). It was observed that people with higher scores on the BDI questionnaire had more extension limitations at the end of 12 weeks of exercise therapy. However, there was no significant correlation between depression and other clinical outcomes such as pain intensity at rest (P=0.246) and during activity (P=0.139), functional ability (P=0.149), and knee flexion ROM (P=0.382) after rehabilitation.

The study found that patients with higher levels of trait anxiety before surgery experienced significantly less reduction in pain during activity (P=0.002) and less improvement in functional ability (P=0.038) after 12 weeks of therapeutic exercise. However, there was no significant correlation between trait anxiety and other clinical outcomes, such as pain at rest or flexion-extension ROM (P<0.05).

There was a significant negative correlation between PCS, reduced pain during activity (P=0.013), and improved functional ability (P=0.023). This means that people with a higher PCS were more likely to experience less pain relief and functional ability improvement. On the other hand, there is no significant correlation between state anxiety and TSK with clinical outcomes of 12 week therapeutic exercise following TKA (P<0.05).

Discussion

The results of the study indicate a significant correlation between the patient’s trait anxiety, PCS and clinical outcomes after 12 weeks of therapeutic exercise following surgery. Patients with higher trait anxiety and PCS before surgery experienced less pain reduction and functional ability improvement after the 12 week exercise program. Furthermore, the study found that psychological indicators are inversely correlated with clinical outcomes. After surgery, therapeutic exercise led to a significant reduction in the severity of trait anxiety and fear of movement.

Previous studies found that anxiety can be used to predict clinical outcomes, including pain and functional ability after TKA [40-42]. Ali et al. found that individuals with higher levels of anxiety and depression before surgery were six times more likely to experience poor outcomes and dissatisfaction following TKA [43]. A review study concluded that anxiety is one of the most significant factors that can predict the success of TKA outcomes [44]. Therefore, according to the consistency of the results of the present study with those of previous ones, it is essential to pay attention to the treatment process of patients after TKA and perform controlled therapeutic exercises. The intensity of anxiety before surgery is one of the significant factors that can affect the treatment outcomes of TKA. In another review study, Lungu et al. reported that a person’s score in the pre-surgery PCS questionnaire can predict their pain and disability level 12 months after TKA. The higher the score, the higher the pain and disability level [5]. Some studies have failed to confirm a correlation between the intensity of PCS before surgery and the intensity of pain and functional outcomes after surgery [45, 46]. It is worth noting that previous studies have only examined the correlation between pre-surgery psychological indicators and post-surgery functional outcomes, and the patients did not receive any controlled treatments during the study period. Therefore, the results obtained from the present study provide more robust evidence that the greater the intensity of PCS before surgery, the less pain reduction and functional ability improvement the patient achieves. The cause of this correlation may be that people with psychological problems have a different understanding of pain and tend to report pain more frequently. This issue affects people’s functional ability. This issue can affect people’s functional ability, which is why psychological problems may have had a negative effect on the results of therapeutic exercise, leading to increased dissatisfaction reports [7].

According to a recent study, psychological factors did not show any significant correlation with the improvement of flexion ROM, which is consistent with the findings of a previous study by Hanusch et al. The previous study also found no correlation between depression, anxiety, and changes in knee flexion ROM [47]. It is worth noting that the patients’ self-reported clinical outcomes, such as pain and functional ability, were influenced by their psychological factors and pain perception. However, the measurable factor of ROM by the physiotherapist was not negatively affected by psychological factors. Therefore, physiotherapists must consider the ROM when determining patients’ satisfaction and QoL after TKA and their psychological condition.

Based on the results obtained, psychological factors like trait anxiety and PCS can have an impact on a patient’s treatment process. Knowing these factors before surgery can help therapists predict treatment outcomes and realistically inform patients what to expect from surgery outcomes and physiotherapy. This information can improve their satisfaction. Patients can also be referred to counseling centers before surgery for effective treatment. Additionally, physiotherapists can provide special attention and care to such patients, which can positively impact the results of physiotherapy treatment.

As part of our study, we aimed to determine how therapeutic exercise over 12 weeks affects psychological indicators. Our findings indicated that patients who participated in the exercise program experienced a significant reduction in trait anxiety and fear of movement by the end of the 12th week. Jones et al. also found that patients’ levels of depression and anxiety decreased after 6 weeks of TKA. Still, they did not investigate controlled therapeutic exercise’s effect on psychological indicators [7]. Monticone et al. discovered that therapeutic exercises based on daily functional activities can reduce fear of movement in patients undergoing TKA after 6 months [29]. The current study confirmed that fear of movement can be reduced in a shorter period without a guide to control fear of movement. Therefore, rehabilitation, such as therapeutic exercise after TKA, can reduce pain and improve functional ability, leading to an improvement in patients’ QoL and a decrease in the severity of their psychological problems.

According to the study results, psychological symptoms such as trait anxiety and fear of movement should not be viewed as barriers to undergoing TKA. These symptoms tend to improve as the knee’s functional state and surgery outcomes recover. Additionally, physical therapy can play a crucial role in alleviating the psychological symptoms of patients.

Therapeutic exercise sessions were not conducted in therapeutic clinics due to the lack of easy access for patients; instead, they were performed at home under supervision with virtual and telephone communication. Due to the limited study time, a study can be designed with a longer follow-up. One group is recommended to be limited to exercise programs in the hospital, while the other group continues physical therapy under the supervision of a physiotherapist.

Conclusion

Psychological factors can play an important role in predicting the clinical outcomes of physiotherapy after TKA. In addition, the improvement of psychological factors after therapeutic exercises may indicate that these psychological problems can be improved by reducing pain and achieving ROM during treatment, so psychological factors are not considered an obstacle to surgery.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1400.993). Participants were fully informed of the objectives of the study. In addition to obtaining written consent, they were assured that information obtained from them would remain confidential.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Fariba Telikani, approved by the Department of Physiotherapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Fariba Telikani and Khosro Khademi Kalantari; Methodology and analysis: Fariba Telikani, Abbas Rahimi and Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban; Research: Fariba Telikani and Mohammad Mehdi Omidian; Review, editing and final approval: Aliyeh Daryabor; Supervision: Khosro Khademi Kalantari.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors appreciate the faculty members of the Department of Physiotherapy at the School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and all those who participated in this study.

References

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is recommended for severe and advanced knee osteoarthritis patients. This therapeutic procedure reduces pain intensity and improves the knee joint’s functional ability [1]. Although most patients achieve significant pain reduction and functional improvement after the procedure, about 15% to 25% report no satisfactory improvement in pain and quality of life (QoL) [2, 3]. Several factors can influence the results of TKA, including the surgical method and the type of prosthesis used [4]. Some previous studies have also suggested demographics (age, gender, and body mass index) clinical and psychological factors [5, 6].

It has been shown that patients who suffer from severe pain for a long time have an increased risk of developing psychological problems [7, 8]. These psychological problems may manifest themselves in anxiety and depression. In patients who are exposed to psychological problems, the perception of pain is closely related to their psychological status. For example, people who exhibit symptoms of depression report more pain both before and after surgery [7].

Psychological factors play an essential role in the clinical outcomes of patients after various types of orthopedic surgery [9]. Several studies have also reported that psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, kinesiophobia, and pain catastrophizing are among the predictors of patient dissatisfaction after TKA [10-13]. A review study indicated that anxiety is one of the main factors associated with poor outcomes after TKA [5]. However, there is conflicting evidence on the role of psychological factors such as depression [14] and anxiety [14-16] in predicting clinical outcomes after surgery. Kinesiophobia, i.e. fear of physical movement, with the idea that movement may lead to pain and injury [17, 18], is a risk factor in predicting the outcome of TKA [19-21].

Pain depends not only on its intensity but also on the patient’s interpretation of the pain. Pain catastrophizing with self-report of pain intensity and duration is considered a modifiable risk factor for predicting the outcomes of a TKA. Pain catastrophizing is a negative variable that results in people being unable to control their pain because they feel helpless and overly reinforce their cognitions related to the painful processes [22]. Lungu et al. found that the higher the person’s score on the pre-surgery pain catastrophizing questionnaire, the greater the pain and disability one year after surgery [5]. However, Birch et al. showed that the group with a higher score on the pain catastrophizing questionnaire made greater progress in gaining functional ability after TKA [23].

Considering that rehabilitation treatment after TKA requires patients’ cooperation, psychological problems can have a negative impact on the outcome of rehabilitation, e.g. subsequent physiotherapy, leading to reports of dissatisfaction reports after this procedure [7]. On the other hand, few studies have investigated the relationship between the fear of movement and clinical outcomes of TKA. Despite the studies investigating the relationship between psychological factors before TKA and clinical outcomes after surgery, to our knowledge, no clear evidence proves this relationship. In the studies conducted, patients were often examined by telephone or virtually and without time monitoring, and no attention was paid to the process they underwent during the study, especially concerning therapeutic exercises after TKA. Perhaps one of the reasons for the inconsistencies is that most studies did not mention the rehabilitation process of patients with psychological problems and physical therapy steps after surgery. However, this process can play an important role in the clinical outcomes of these patients. For example, in a study examining the correlation between depression and anxiety with outcomes of TKA, it was found that not only depression and anxiety are related to surgical outcomes but also that the level of depression and anxiety decreased 6 weeks following surgery. The severity of the patient’s psychological symptoms decreases as their abilities improve. Therefore, they do not consider depression and anxiety as contraindications for surgery [7]. On the other hand, both aerobic and resistance exercise have been reported effective in treating depression, and the effect of aerobic exercise therapy was equivalent to therapeutic-psychological interventions in the treatment of depression [24]. There is also evidence that therapeutic exercise improves psychological status in cancer patients [25, 26] and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction [27].

Studies investigating the effect of therapeutic exercise after TKA have reported that exercise can significantly improve clinical outcomes in these patients [28]. However, few studies have investigated the effect of exercise therapy on the severity of psychological problems following this surgery. In a previous study, the impact of physical therapy, including functional exercises and theoretical information on how to deal with the fear of movement after TKA, was investigated, and the results showed that the interventions effectively improved this outcome [29]. However, no study has been conducted to show whether only therapeutic exercises without psychological interventions can improve psychological factors after TKA. Therefore, this study investigated the relationship between psychological characteristics and clinical outcomes of therapeutic exercise after 12 weeks. Another aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of 12 weeks of therapeutic exercise on patients’ psychological characteristics.

Materials and Methods

Study participants

In this quasi-experimental study, 29 female patients who were candidates for TKA for their first knees and had been referred to the orthopedic department of Imam Hossein Hospital were examined by the researcher on the day of admission with the prior coordination of the orthopedic surgeon. If the inclusion and exclusion criteria were met, the steps of the study were explained to them. If the individuals were willing to cooperate further, they signed the written informed consent form. The inclusion criteria for this study were women eligible for TKA for their first knees who could speak, read, and write in Persian. The exclusion criteria included lack of cooperation during the study, damage to the prosthesis after an injury, joint infection after surgery, and prosthesis in the lower extremity on the surgical side. All patients underwent TKA with American Zimmer Biomet prosthesis with posterior cruciate ligament retained by one surgeon.

Study tools

The following tools were used to assess the clinical outcomes of patients.

Visual analog scale

This scale was used to assess pain intensity at rest and during activity. This scale consists of a 100 mm straight line with the words “no pain” on one side and “worst pain imaginable” on the other. Participants are instructed to make a mark on the line indicating the pain level they are experiencing during the evaluation. Its validity and reliability are acceptable in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain [30]. To rate the pain at rest, patients were asked to mark on the line how they felt it in the last week. Patients were asked to walk for 6 minutes to measure pain intensity during activity and then mark on the line.

Goniometer

In this study, Rahavard Mehr’s Iranian goniometer was used to determine the active range of motion (ROM) of knee flexion and extension. To measure the knee flexion, which was performed in the supine position with the hip flexed, the center of the goniometer was on the lateral condyle of the femur, the fixed arm was aligned with the lateral condyle of the femur and its longitudinal axis, and the movable arm was aligned with the lateral malleus and the longitudinal axis of the tibia. The individual was asked to flex their knee actively, and the ROM was recorded. To measure knee extension, the person’s knee was brought into the extension position as far as possible, and the goniometer was placed the same way as when measuring knee flexion.

Oxford knee score (OKS)

The 12-item OKS self-report questionnaire was used to check patients’ functional ability, which examines various dimensions of knee pain and function after TKA. This questionnaire is scored based on 5 items (0: Most disability, 4: Least disability) according to the condition reported by the patient. The total score ranges from 0 to 48, with higher scores indicating higher functional ability. The Persian version of this questionnaire has good validity and reliability [31]. The patients’ psychological indicators were assessed using the following tools.

Beck depression inventory (BDI) II

To assess the intensity of depression, the updated 21-item BDI II questionnaire was utilized. The questionnaire is scored based on four answer choices, with a value ranging from 0 to 3, depending on the severity reported by the patient. The Persian version of this questionnaire has satisfactory psychometric properties [32].

State trait anxiety index (STAI)

This questionnaire was used to assess “state” and “trait” anxiety. It was standardized for the Iranian population with a high validity and reliability [33]. This 40-item questionnaire comprises two sections, each with 20 questions: Trait anxiety and state anxiety. While answering the state anxiety scale, respondents are asked to consider their present feelings, whereas when responding to the trait anxiety scale, they should report their usual and consistent feelings. The total scores of the trait and state anxiety scales range from 20 to 80. Scoring higher on the anxiety test indicates a greater level of anxiety. A score of 40 and above for the state section of the questionnaire indicates that the person is currently experiencing high anxiety [34].

Pain catastrophizing scale (PCS)

PCS is a 13-item self-report questionnaire to assess catastrophic thoughts and behaviors related to pain [35]. The questionnaire asks individuals to rate the degree to which they have experienced past painful thoughts and feelings on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 0: Never to 4: Always. This scale’s Persian version has been found reliable in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain [36].

Tampa scale of kinesiophobia (TSK)

This scale measures the fear of painful movement, physical activity, and re-injury. It consists of a self-report checklist with 17 items, using a 4-point Likert scale (1: Strongly disagree and 4: Strongly agree), with a maximum score of 68. A higher score indicates greater kinesiophobia related to movements and re-injury [37].

Intervention and procedure

During this study, which lasted for 12 weeks, patients performed therapeutic exercises under the supervision of a physiotherapist. One day before the surgery, the physiotherapist measured the intensity of the patient’s knee pain at rest during the last week and during activity immediately after a 6-minute walking test. Additionally, the physiotherapist measured the patients’ active flexion and extension ROM of the knee. Patients also filled out questionnaires related to psychological indicators and functional ability.

Individuals who underwent TKA were subjected to a standard exercise program during one session the day after their surgery [38]. The therapeutic exercises were performed in the first 3 weeks post-surgery, emphasizing restoring the ROM of 90-degree flexion and 0-degree extension and muscle strength around the knee. The exercises included rhythmic dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of the ankle (ankle pumping exercise) to control swelling of the leg and prevent clots, sliding heel on the bed and wall, quadriceps setting exercise, terminal knee extension, active assisted knee flexion, straight leg raising exercise, and stretching of the hamstrings and gastrocnemius muscles. Patients were instructed to perform each exercise daily in 4 sets (every 3-4 hours) of 10 repetitions (Table 1).

These exercises lasted about 30 minutes each time. Educational brochures were also given to patients outlining the exercise.

To control pain and swelling, patients were taught to use a cold compress on their knee for 15 minutes every 3-4 hours for 6 weeks [39]. After teaching the exercises, the physiotherapist re-measured the knee’s active flexion and extension ROM one day after the surgery (Figure 1).

The therapist then evaluated the pain intensity at rest.

After the stitches were removed at the end of the third week, the second phase of exercises began. This phase aimed to achieve knee ROM between 90-125 degrees, reduce pain and swelling, improve balance, and promote independence. To achieve these goals, hamstring curls and hip abductions were added to the exercise plan used in the first phase.

At the end of the 12th week, the patients were asked to complete all questionnaires. The pain intensity at rest and during activity and knee ROM were re-examined. After being discharged from the hospital until the end of the study period, the patients remained in virtual communication with their therapist. The physiotherapist regularly checked the patients’ ROM and exercises by reviewing photos and videos sent by the patients. This virtual communication was maintained once every three days for the first three weeks after surgery and weekly throughout the remainder of the study. Throughout the 12 week treatment period, the patients were evaluated and treated by one physiotherapist, unaware of the score of the psychological indicators.

Statistical analysis

To investigate the correlation between quantitative variables, we used the Pearson and partial correlation coefficient (to control the confounding effect of age and body mass index) based on the normality of data distribution. For comparing patients’ psychological characteristics before surgery and after physical therapy, we checked the normality of data distribution via the Shapiro-Wilk test. Next, we used the paired t-test to compare two conditions. We conducted the statistical analysis of data using SPSS software, version 25 at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

In this study, 29 female patients who had undergone unilateral TKA and had an average age of 62.76 years were analyzed. Table 2 provides a summary of the participants’ characteristics at the beginning of the research.

Effect of therapeutic exercise on psychological factors

The results showed that 12 week therapeutic exercise after TKA had a significant effect on reducing psychological problems, including fear of movement (P=0.01) and trait anxiety (P=0.01). The statistical indicators of these scores before surgery and after 12 week therapeutic exercise are shown in Table 3.

Relationship between psychological factors and clinical outcomes

Table 4 presents the correlation between pre-surgery psychological factors and changes in pain intensity, flexion and extension ROM, and functional ability following 12 weeks of therapeutic exercises.

According to the findings, there was a significant correlation between pre-surgery depression and decreased extension ROM of the knee (r=0.435, P=0.023). It was observed that people with higher scores on the BDI questionnaire had more extension limitations at the end of 12 weeks of exercise therapy. However, there was no significant correlation between depression and other clinical outcomes such as pain intensity at rest (P=0.246) and during activity (P=0.139), functional ability (P=0.149), and knee flexion ROM (P=0.382) after rehabilitation.

The study found that patients with higher levels of trait anxiety before surgery experienced significantly less reduction in pain during activity (P=0.002) and less improvement in functional ability (P=0.038) after 12 weeks of therapeutic exercise. However, there was no significant correlation between trait anxiety and other clinical outcomes, such as pain at rest or flexion-extension ROM (P<0.05).

There was a significant negative correlation between PCS, reduced pain during activity (P=0.013), and improved functional ability (P=0.023). This means that people with a higher PCS were more likely to experience less pain relief and functional ability improvement. On the other hand, there is no significant correlation between state anxiety and TSK with clinical outcomes of 12 week therapeutic exercise following TKA (P<0.05).

Discussion

The results of the study indicate a significant correlation between the patient’s trait anxiety, PCS and clinical outcomes after 12 weeks of therapeutic exercise following surgery. Patients with higher trait anxiety and PCS before surgery experienced less pain reduction and functional ability improvement after the 12 week exercise program. Furthermore, the study found that psychological indicators are inversely correlated with clinical outcomes. After surgery, therapeutic exercise led to a significant reduction in the severity of trait anxiety and fear of movement.

Previous studies found that anxiety can be used to predict clinical outcomes, including pain and functional ability after TKA [40-42]. Ali et al. found that individuals with higher levels of anxiety and depression before surgery were six times more likely to experience poor outcomes and dissatisfaction following TKA [43]. A review study concluded that anxiety is one of the most significant factors that can predict the success of TKA outcomes [44]. Therefore, according to the consistency of the results of the present study with those of previous ones, it is essential to pay attention to the treatment process of patients after TKA and perform controlled therapeutic exercises. The intensity of anxiety before surgery is one of the significant factors that can affect the treatment outcomes of TKA. In another review study, Lungu et al. reported that a person’s score in the pre-surgery PCS questionnaire can predict their pain and disability level 12 months after TKA. The higher the score, the higher the pain and disability level [5]. Some studies have failed to confirm a correlation between the intensity of PCS before surgery and the intensity of pain and functional outcomes after surgery [45, 46]. It is worth noting that previous studies have only examined the correlation between pre-surgery psychological indicators and post-surgery functional outcomes, and the patients did not receive any controlled treatments during the study period. Therefore, the results obtained from the present study provide more robust evidence that the greater the intensity of PCS before surgery, the less pain reduction and functional ability improvement the patient achieves. The cause of this correlation may be that people with psychological problems have a different understanding of pain and tend to report pain more frequently. This issue affects people’s functional ability. This issue can affect people’s functional ability, which is why psychological problems may have had a negative effect on the results of therapeutic exercise, leading to increased dissatisfaction reports [7].

According to a recent study, psychological factors did not show any significant correlation with the improvement of flexion ROM, which is consistent with the findings of a previous study by Hanusch et al. The previous study also found no correlation between depression, anxiety, and changes in knee flexion ROM [47]. It is worth noting that the patients’ self-reported clinical outcomes, such as pain and functional ability, were influenced by their psychological factors and pain perception. However, the measurable factor of ROM by the physiotherapist was not negatively affected by psychological factors. Therefore, physiotherapists must consider the ROM when determining patients’ satisfaction and QoL after TKA and their psychological condition.

Based on the results obtained, psychological factors like trait anxiety and PCS can have an impact on a patient’s treatment process. Knowing these factors before surgery can help therapists predict treatment outcomes and realistically inform patients what to expect from surgery outcomes and physiotherapy. This information can improve their satisfaction. Patients can also be referred to counseling centers before surgery for effective treatment. Additionally, physiotherapists can provide special attention and care to such patients, which can positively impact the results of physiotherapy treatment.

As part of our study, we aimed to determine how therapeutic exercise over 12 weeks affects psychological indicators. Our findings indicated that patients who participated in the exercise program experienced a significant reduction in trait anxiety and fear of movement by the end of the 12th week. Jones et al. also found that patients’ levels of depression and anxiety decreased after 6 weeks of TKA. Still, they did not investigate controlled therapeutic exercise’s effect on psychological indicators [7]. Monticone et al. discovered that therapeutic exercises based on daily functional activities can reduce fear of movement in patients undergoing TKA after 6 months [29]. The current study confirmed that fear of movement can be reduced in a shorter period without a guide to control fear of movement. Therefore, rehabilitation, such as therapeutic exercise after TKA, can reduce pain and improve functional ability, leading to an improvement in patients’ QoL and a decrease in the severity of their psychological problems.

According to the study results, psychological symptoms such as trait anxiety and fear of movement should not be viewed as barriers to undergoing TKA. These symptoms tend to improve as the knee’s functional state and surgery outcomes recover. Additionally, physical therapy can play a crucial role in alleviating the psychological symptoms of patients.

Therapeutic exercise sessions were not conducted in therapeutic clinics due to the lack of easy access for patients; instead, they were performed at home under supervision with virtual and telephone communication. Due to the limited study time, a study can be designed with a longer follow-up. One group is recommended to be limited to exercise programs in the hospital, while the other group continues physical therapy under the supervision of a physiotherapist.

Conclusion

Psychological factors can play an important role in predicting the clinical outcomes of physiotherapy after TKA. In addition, the improvement of psychological factors after therapeutic exercises may indicate that these psychological problems can be improved by reducing pain and achieving ROM during treatment, so psychological factors are not considered an obstacle to surgery.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.SBMU.RETECH.REC.1400.993). Participants were fully informed of the objectives of the study. In addition to obtaining written consent, they were assured that information obtained from them would remain confidential.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Fariba Telikani, approved by the Department of Physiotherapy, School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Fariba Telikani and Khosro Khademi Kalantari; Methodology and analysis: Fariba Telikani, Abbas Rahimi and Alireza Akbarzadeh Baghban; Research: Fariba Telikani and Mohammad Mehdi Omidian; Review, editing and final approval: Aliyeh Daryabor; Supervision: Khosro Khademi Kalantari.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Authors appreciate the faculty members of the Department of Physiotherapy at the School of Rehabilitation, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and all those who participated in this study.

References

- Losina E, Walensky RP, Kessler CL, Emrani PS, Reichmann WM, Wright EA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of total knee arthroplasty in the United States: Patient risk and hospital volume. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2009; 169(12):1113-21. [DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2009.136] [PMID]

- DeFrance MJ, Scuderi GR. Are 20% of patients actually dissatisfied following total knee arthroplasty? A systematic review of the literature. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2023; 38(3):594-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.arth.2022.10.011] [PMID]

- Nakahara H, Okazaki K, Mizu-Uchi H, Hamai S, Tashiro Y, Matsuda S, et al. Correlations between patient satisfaction and ability to perform daily activities after total knee arthroplasty: why aren’t patients satisfied? Journal of Orthopaedic Science. 2015; 20(1):87-92. [DOI:10.1007/s00776-014-0671-7] [PMID]

- Gunaratne R, Pratt DN, Banda J, Fick DP, Khan RJK, Robertson BW. Patient dissatisfaction following total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review of the literature. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017; 32(12):3854-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.arth.2017.07.021] [PMID]

- Lungu E, Vendittoli P, Desmeules F. Preoperative determinants of patient-reported pain and physical function levels following total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. The Open Orthopaedics Journal. 2016; 10:213-31. [DOI:10.2174/1874325001610010213] [PMID]

- Schatz C, Klein N, Marx A, Buschner P. Preoperative predictors of health-related quality of life changes (EQ-5D and EQ VAS) after total hip and knee replacement: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2022; 23(1):58. [DOI:10.1186/s12891-021-04981-4] [PMID]

- Jones AR, Al-Naseer S, Bodger O, James ETR, Davies AP. Does pre-operative anxiety and/or depression affect patient outcome after primary knee replacement arthroplasty? The Knee. 2018; 25(6):1238-46. [DOI:10.1016/j.knee.2018.07.011] [PMID]

- Merskey H. Psychological aspects of pain. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 1968; 44(510):297. [DOI:10.1136/pgmj.44.510.297] [PMID]

- Ayers DC, Franklin PD, Ring DC. The role of emotional health in functional outcomes after orthopaedic surgery: Extending the biopsychosocial model to orthopaedics: AOA critical issues. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American. 2013 6; 95(21):e165. [DOI:10.2106/JBJS.L.00799] [PMID]

- Ayers DC, Franklin PD, Ploutz-Snyder R, Boisvert CB. Total knee replacement outcome and coexisting physical and emotional illness. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2005; 440:157-61. [DOI:10.1097/01.blo.0000185447.43622.93] [PMID]

- Escobar A, Quintana JM, Bilbao A, Azkárate J, Güenaga JI, Arenaza JC, et al. Effect of patient characteristics on reported outcomes after total knee replacement. Rheumatology. 2007; 46(1):112-9. [DOI:10.1093/rheumatology/kel184] [PMID]

- Lingard EA, Katz JN, Wright EA, Sledge CB; Kinemax Outcomes Group. Predicting the outcome of total knee arthroplasty. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American volume. 2004; 86(10):2179-86. [DOI:10.2106/00004623-200410000-00008] [PMID]

- Roth ML, Tripp DA, Harrison MH, Sullivan M, Carson P. Demographic and psychosocial predictors of acute perioperative pain for total knee arthroplasty. Pain Research and Management. 2007; 12(3):185-94. [DOI:10.1155/2007/394960] [PMID]

- Vissers MM, Bussmann JB, Verhaar JA, Busschbach JJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Reijman M. Psychological factors affecting the outcome of total hip and knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2012; 41(4):576-88.[DOI:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.07.003] [PMID]

- Bletterman AN, de Geest-Vrolijk ME, Vriezekolk JE, Nijhuis-van der Sanden MW, van Meeteren NL, Hoogeboom TJ. Preoperative psychosocial factors predicting patient’s functional recovery after total knee or total hip arthroplasty: A systematic review. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2018; 32(4):512-25. [DOI:10.1177/0269215517730669] [PMID]

- Khatib Y, Madan A, Naylor JM, Harris IA. Do psychological factors predict poor outcome in patients undergoing TKA? A systematic review. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2015; 473(8):2630-8. [DOI:10.1007/s11999-015-4234-9] [PMID]

- Vlaeyen JW, Kole-Snijders AM, Rotteveel AM, Ruesink R, Heuts PH. The role of fear of movement/(re) injury in pain disability. Journal of Occupational Rehabilitation. 1995; 5(4):235-52.[DOI:10.1007/BF02109988] [PMID]

- Brown OS, Hu L, Demetriou C, Smith TO, Hing CB. The effects of kinesiophobia on outcome following total knee replacement: A systematic review. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2020; 140(12):2057-70. [DOI:10.1007/s00402-020-03582-5] [PMID]

- Güney-Deniz H, Irem Kınıklı G, Çağlar Ö, Atilla B, Yüksel İ. Does kinesiophobia affect the early functional outcomes following total knee arthroplasty? Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2017; 33(6):448-53. [DOI:10.1080/09593985.2017.1318988] [PMID]

- Filardo G, Merli G, Roffi A, Marcacci T, Berti Ceroni F, Raboni D, et al. Kinesiophobia and depression affect total knee arthroplasty outcome in a multivariate analysis of psychological and physical factors on 200 patients. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2017; 25(11):3417-23. [DOI:10.1007/s00167-016-4201-3] [PMID]

- Terradas-Monllor M, Ruiz MA, Ochandorena-Acha M. Postoperative psychological predictors for chronic postsurgical pain after a knee arthroplasty: A prospective observational study. Physical Therapy. 2024; 104(1):pzad141. [DOI:10.1093/ptj/pzad141] [PMID]

- Burns LC, Ritvo SE, Ferguson MK, Clarke H, Seltzer Z, Katz J. Pain catastrophizing as a risk factor for chronic pain after total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. Journal of Pain Research. 2015; 8:21-32. [DOI:10.2147/JPR.S64730] [PMID]

- Birch S, Stilling M, Mechlenburg I, Hansen TB. The association between pain catastrophizing, physical function and pain in a cohort of patients undergoing knee arthroplasty. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2019; 20(1):421. [DOI:10.1186/s12891-019-2787-6] [PMID]

- Etnier JL. Psychology of physical activity: Determinants, well-being, and interventions. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2001; 33(10):1796. [DOI:10.1097/00005768-200110000-00030]

- Zyzniewska-Banaszak E, Kucharska-Mazur J, Mazur A. Physiotherapy and physical activity as factors improving the psychological state of patients with cancer. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021; 12:772694. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.772694] [PMID]

- Zeng J, Wu J, Tang C, Xu N, Lu L. Effects of exercise during or postchemotherapy in cancer patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing. 2019; 16(2):92-101. [DOI:10.1111/wvn.12341] [PMID]

- Chmielewski TL, Zeppieri G Jr, Lentz TA, Tillman SM, Moser MW, Indelicato PA, et al. Longitudinal changes in psychosocial factors and their association with knee pain and function after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Physical Therapy. 2011; 91(9):1355-66. [DOI:10.2522/ptj.20100277] [PMID]

- Fatoye F, Yeowell G, Wright JM, Gebrye T. Clinical and cost-effectiveness of physiotherapy interventions following total knee replacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery. 2021; 141(10):1761-78.[DOI:10.1007/s00402-021-03784-5] [PMID]

- Monticone M, Ferrante S, Rocca B, Salvaderi S, Fiorentini R, Restelli M, et al. Home-based functional exercises aimed at managing kinesiophobia contribute to improving disability and quality of life of patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013; 94(2):231-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.10.003] [PMID]

- Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain. 1983; 17(1):45-56. [DOI:10.1016/0304-3959(83)90126-4] [PMID]

- Ebrahimzadeh MH, Makhmalbaf H, Birjandinejad A, Soltani-Moghaddas SH. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the persian version of the oxford knee score in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2014; 39(6):529-35. [PMID]

- Ghassemzadeh H, Mojtabai R, Karamghadiri N, Ebrahimkhani N. Psychometric properties of a Persian-language version of the Beck Depression Inventory-Second edition: BDI-II-PERSIAN. Depress Anxiety. Depression and Anxiety. 2005; 21(4):185-92. [DOI:10.1002/da.20070] [PMID]

- Abdoli N, Farnia V, Salemi S, Davarinejad O, Ahmadi Jouybari T, Khanegi M, et al. Reliability and validity of Persian version of state-trait anxiety inventory among high school students. East Asian Archives of Psychiatry. 2020; 30(2):44-7. [PMID]

- Knight RG, Waal-Manning HJ, Spears GF. Some norms and reliability data for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory and the Zung Self-Rating Depression scale. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1983; 22(4):245-9. [DOI:10.1111/j.2044-8260.1983.tb00610.x] [PMID]

- Sullivan MJ, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: Development and validation. Psychological Assessment. 1995; 7(4):524-32. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.7.4.524]

- Raeissadat SA, Sadeghi S, Montazeri A. Validation of the pain catastrophizing scale (PCS) in Iran. Journal of Basic and Applied Scientific Research. 2013; 3(9):376-80. [Link]

- Jafari H, Ebrahimi I, Salavati M, Kamali M, Fata L. [Psychometric properties of Iranian version of Tampa Scale for Kinesiophobia in low back pain patients (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2010; 11(1):15-22. [Link]

- Eymir M, Erduran M, Ünver B. Active heel-slide exercise therapy facilitates the functional and proprioceptive enhancement following total knee arthroplasty compared to continuous passive motion. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2021; 29(10):3352-60. [DOI:10.1007/s00167-020-06181-4] [PMID]

- Schinsky MF, McCune C, Bonomi J. Multifaceted comparison of two cryotherapy devices used after total knee arthroplasty: Cryotherapy device comparison. Orthopaedic Nursing. 2016; 35(5):309-16. [DOI:10.1097/NOR.0000000000000276] [PMID]

- Brander VA, Stulberg SD, Adams AD, Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanos SP, et al. Ranawat Award Paper: Predicting total knee replacement pain: A prospective, observational study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2003; 416:27-36. [DOI:10.1097/01.blo.0000092983.12414.e9] [PMID]

- Hirschmann MT, Testa E, Amsler F, Friederich NF. The unhappy total knee arthroplasty (TKA) patient: Higher WOMAC and lower KSS in depressed patients prior and after TKA. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2013; 21(10):2405-11. [DOI:10.1007/s00167-013-2409-z] [PMID]

- Qi A, Lin C, Zhou A, Du J, Jia X, Sun L, et al. Negative emotions affect postoperative scores for evaluating functional knee recovery and quality of life after total knee replacement. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2016; 49(1):e4616.[DOI:10.1590/1414-431x20154616] [PMID]

- Ali A, Lindstrand A, Sundberg M, Flivik G. Preoperative anxiety and depression correlate with dissatisfaction after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of 186 patients, with 4-year follow-up. The Journal of Arthroplasty. 2017; 32(3):767-70. [DOI:10.1016/j.arth.2016.08.033] [PMID]

- Alattas SA, Smith T, Bhatti M, Wilson-Nunn D, Donell S. Greater pre-operative anxiety, pain and poorer function predict a worse outcome of a total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2017; 25(11):3403-10. [DOI:10.1007/s00167-016-4314-8] [PMID]

- Riddle DL, Wade JB, Jiranek WA, Kong X. Preoperative pain catastrophizing predicts pain outcome after knee arthroplasty. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2010; 468(3):798-806. [DOI:10.1007/s11999-009-0963-y] [PMID]

- Høvik LH, Winther SB, Foss OA, Gjeilo KH. Preoperative pain catastrophizing and postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty: A prospective cohort study with one year follow-up. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 2016; 17:214. [DOI:10.1186/s12891-016-1073-0] [PMID]

- Hanusch BC, O'Connor DB, Ions P, Scott A, Gregg PJ. Effects of psychological distress and perceptions of illness on recovery from total knee replacement. The Bone & Joint Journal. 2014; 96(2):210-6. [DOI:10.1302/0301-620X.96B2.31136] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Physical Therapy

Received: 21/09/2023 | Accepted: 6/04/2024 | Published: 1/10/2024

Received: 21/09/2023 | Accepted: 6/04/2024 | Published: 1/10/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |