Volume 25 - Special Issue

jrehab 2024, 25 - Special Issue: 636-663 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Soleimani F, Nobakht Z, Azari N, Kraskian A, Hassanati F, Ghorbanpor Z. Validity and Reliability Determination of the Persian Version of the Adaptive Behavior Assessment System. jrehab 2024; 25 (S3) :636-663

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3363-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3363-en.html

Farin Soleimani1

, Zahra Nobakht *2

, Zahra Nobakht *2

, Nadia Azari1

, Nadia Azari1

, Adis Kraskian3

, Adis Kraskian3

, Fatemeh Hassanati4

, Fatemeh Hassanati4

, Zahra Ghorbanpor5

, Zahra Ghorbanpor5

, Zahra Nobakht *2

, Zahra Nobakht *2

, Nadia Azari1

, Nadia Azari1

, Adis Kraskian3

, Adis Kraskian3

, Fatemeh Hassanati4

, Fatemeh Hassanati4

, Zahra Ghorbanpor5

, Zahra Ghorbanpor5

1- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,nobakht.zahra@gmail.com

3- Department of General Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Karaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Karaj, Iran.

4- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Occupational Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of General Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, Karaj Branch, Islamic Azad University, Karaj, Iran.

4- Department of Speech Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

5- Department of Occupational Therapy, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 3113 kb]

(752 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4110 Views)

Full-Text: (911 Views)

Introduction

The concept of adaptive behavior typically refers to an individual’s capacity to take on greater responsibility for themselves and subsequently assist others in developing essential daily life skills. Conducting a thorough and accurate assessment of adaptive behaviors is crucial as it forms the foundation for early identification and subsequent intervention. This information can be gathered from various informants familiar with the behaviors of young children, or through reliable tests. Assessing the behavior of children from birth to 5 years old often presents challenges due to changes in behavior and the difficulty in engaging them in the assessment process. Utilizing adaptive behavior scales can mitigate some of these challenges, making them a common tool for evaluating young children [1, 2]. Adaptive skills in children, such as social self-care, communication, social behaviors, and motor skills, develop in response to their living environments. These along with other adaptive skills are essential for sufficient and independent performance at home, in school and within the community. Early disruptions in these skills can predict more persistent disorders later on. Consequently, early intervention based on accurate and practical assessments can reduce or even prevent the emergence of chronic conditions [3]. Additionally, specialists can assess adaptive behavior to determine the performance levels of individuals with various disorders.

Throughout the 20th century, the evaluation of adaptive behavior emerged as an essential factor for diagnosing mental retardation and devising interventions for individuals with this condition [3]. According to the 2002 definition by the American Association for Mental Retardation, adaptive behavior is categorized into three domains: conceptual, social and practical, all of which are essential for daily functioning [4]. Moreover, current diagnostic and classification systems, including the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, American Association for Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, and International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision, share three universal criteria for confirming or dismissing a diagnosis of intellectual disability (ID): a) Notable restrictions in intellectual functioning, b) Notable restrictions in adaptive behavior and c) Onset during the period of development [5, 6, 7, 8]. Since 2002, the significance of adaptive behavior’s structure and its importance in identifying intellectual disability have been established [4, 9, 10]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition moves away from relying solely on intelligence quotient scores to measure the severity of intellectual disability, rather employing adaptive behavior assessments as a measure of severity [5]. Although over 200 adaptive behavior scales exist, only four have been standardized with criteria for testing, and a limited number have been known to be particularly effective in the diagnosis of intellectual disability [7, 11]. The four instruments standardized for US samples include the Vineland adaptive behavior scales [12], the adaptive behavior assessment system (ABAS) [13], the scales of independent behavior-revised [14] and the school function assessment [15].

Determining the instrument’s validity, sensitivity and specificity is important. For instance, concerning the ABAS, its authors noted that the average scores for the group with developmental disabilities were significantly less than those for the normative group [15]. However, they did not disclose the exact percentage of individuals accurately identified; thus, the precision of the school ABAS in correctly diagnosing someone with a developmental disability remains uncertain.

In the comprehensive manual for the revised independent behavior scale, Bruininks et al. [14] offered a more thorough analysis of sensitivity and specificity. They reported that 76% of individuals in the standard sample were accurately classified into their respective groups: 51% in the group with mild, 74% with moderate, and 82% without disability. From a decision-making standpoint, the lowest accuracy rate (i.e. 51% sensitivity) on the revised independent behavior scale was observed in the group with mild disability, given the narrow margin for differentiating this group from the normative group. Nonetheless, if only half of those diagnosed with mild intellectual disability have scores indicative of such a diagnosis, the revised independent behavior scale might lack the sensitivity required for accurately distinguishing individuals with mild conditions from those with mental retardation. Moreover, while the revised independent behavior scale spans various age groups from infancy onwards, it does not provide sensitivity and specificity figures for distinct age categories. On the Vineland adaptive behavior scales, the accuracy of classification ranged from 71% to 100% among individuals aged 6 to 18 years (71% for mild, 87% for moderate, and 100% for severe disability). The Vineland adaptive behavior scales also offer data on sensitivity across different skill domains (e.g. daily living skills, communication, social skills, and motor skills). However, details regarding the rate at which individuals were correctly diagnosed with a disability (i.e. specificity) have not been reported [12].

ABAS stands out as a reliable questionnaire for evaluating adaptive behavior in children. Initially designed for individuals aged 5 to 89 years, its second version extends its applicability to ages 0 to 89 years. ABAS includes four different forms targeting parents (for children aged birth to 21 years), teachers (for children and young adults aged 5 to 21 years) and adults (aged 16 to 89 years), with two assessment options available: Self-assessment or assessment by others, across various age categories. This scale provides normative scores across 10 skill areas covering community use, communication, functional pre-academic, home living, health and safety, leisure, self-care, self-direction, social and motor skills, all with an average score of 10 and a standard deviation of 3. It offers standard scores for conceptual, social and practical domains, alongside a general adaptive composite score with an average of 100, a standard deviation of 15, 90% and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and percentile rankings [13].

The adaptive behavior scales in the Persian language is the survey form of Vineland adaptive behavior scales that have been standardized for individuals from birth to 18 years [16, 17]. The Vineland scales feature three forms: The survey interview, parent/caregiver rating, expanded interview, and teacher rating. This form assesses the following four domains: Communication, daily living skills, socialization, motor skills, and maladaptive behavior. Another notable Persian adaptive behavior questionnaire is the third edition of the children’s behavior assessment system, designed for parents and teachers. It was administered to a cohort of adolescents aged 12 to 16 years in Yazd City, Iran [18]. This questionnaire extensively evaluates emotional challenges within school and clinical settings, offering multiple assessments to aid in the identification and development of treatment plans, including a comprehensive evaluation of both externalized and internalized behavioral symptoms [19]. Furthermore, the indicators of this questionnaire play an important role in diagnosing various disorders [18].

One of the primary challenges faced by researchers and professionals in analyzing functional outcomes across various individual and societal levels is the creation of suitable scales for assessment. When these scales are internationally available, the task becomes selecting the most appropriate one from the existing tools. The goal of this selection process is to find tools that best satisfy the clinical and research needs of researchers, enabling them to evaluate the effects of injuries and diseases, the impact of strategies, interventions, treatment, and rehabilitation programs, monitor patient progress, and ultimately make clinical decisions about whether to continue, halt, or adjust these actions. Factors such as the tool’s focus on different target populations, its application through observation or patient interviews, its psychometric properties, its sub-scales, etc. are considered during this process.

Given the absence of a comprehensive and suitable tool for assessing adaptive behavior and evaluating this aspect of development in young children across various skill areas, and considering the high validity and reliability of the ABAS, along with its coverage of ten primary skill areas in young children (including communication, community use, functional pre-academic, home living, health and safety, leisure, self-care, self-direction, social skills and motor skills) as rated by parents and caregivers, this study translates and culturally adapts ABAS and then assesses the validity and reliability of its Persian version for use by researchers and the healthcare system in early detection and intervention in behavioral disorders.

Materials and Methods

This study employed a methodological approach. The Persian version of the ABAS was created through a meticulous process of translation and back-translation. The translation to Persian and the cross-cultural adaptation of the ABAS followed the international quality of life assessment project approach guidelines [20]. Initially, two independent translators, both fluent in Persian and English and knowledgeable about children’s adaptive behavior development, translated the original scale from English to Persian. These versions were then reviewed by the research team, resulting in the first Persian draft. This draft was subsequently translated back into English by two native English speakers. The research group convened to compare these re-translated versions with the original English text, identify any translation discrepancies, and produce a second Persian draft. This version was then evaluated by 11 experts in child development, including psychologists, pediatricians specialized in child development, occupational therapists and child psychiatrists, for face and content validity. Their feedback led to cultural and linguistic modifications. Additionally, to assess face validity, cognitive interviews were conducted with 11 mothers of children aged 1 to 42 months. The research team reviewed their feedback, leading to the final version of the instrument. For structural validity, factor analysis using principal component analysis (PCA) was applied. The Cronbach α and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with a 95% CI were calculated to assess test-retest reliability and internal consistency, respectively. Given the absence of a specific formula for estimating sample size in studies evaluating the validity and reliability of tests, and using of factor analysis method in this research, it was recommended to have a minimum sample of 200 individuals for a vigorous assessment of construct validity [21]. Thus, a target sample size of 200 children was set, ultimately including 253 parents of children aged 1 to 42 months in the study.

Study instruments

In this study, the second edition of ABAS by Harrison and Oakland (2003) was utilized to evaluate the daily functional abilities of children aged 0-5 years. This scale identifies the skills a child currently has or is likely to develop in the future. The ABAS functions as a screening tool across ten skill domains. For children under one year of age, the scale evaluates the following seven skill domains: Communication, health and safety, leisure, self-care, self-direction, social skills, and motor skills. For children aged 1 to 5 years, it assesses ten skill domains as follows: Communication, community use, Functional pre-academic, home living, health and safety, leisure, self-care, self-direction, social, and motor skills. The assessment is completed by parents or caregivers and aims to measure significant behaviors demonstrated by the child at home, in preschool settings, and other contexts [13].

The scoring range for this scale spans from 0 ("Is not able") to 3 ("Always when needed"), with the scoring conducted by the respondent. Concurrently, the respondent denotes whether the behavior was directly observed or is based on a guess about its repetition and frequency. If the scoring is speculative, the respondent marks a check (√) in the box labeled check if you guessed. If the assessment is based on direct observation or firsthand knowledge, this column is left blank. The scale assesses the child’s abilities in 7 to 10 domains according to age, as follows: Communication, which includes 25 questions; community use, comprising 22 questions about interest in external activities and recognizing different facilities; functional pre-academic, with 23 questions on letter recognition, counting and simple drawing; home living, including 25 questions about assisting with daily tasks and managing personal belongings; health and safety, with 24 questions on precaution and avoiding physical hazards; leisure, comprising 22 questions on the play, game rules adherence, and creativity at home; self-care, including 24 questions on eating, toileting, and bathing; self-direction, with 25 questions on self-control, rule adherence, and making choices; social skills, comprising 24 questions on empathy, assistance, emotional and mental state recognition, and etiquette; and motor skills, with 27 questions on moving and manipulating objects in the environment [22].

The original version’s reliability coefficients in the parent form for conceptual, social and practical domains were reported as 96%, 94% and 96%, respectively. Inter-rater reliability among parents and teachers for the 10 skill domains was reported in the range of 60-70%. Additionally, the correlation between the school-age teacher form and the Vineland adaptive behavior scales-classroom Version was 82% [13].

Reliability and validity

The content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were employed to quantitatively assess content validity. Following the survey questionnaires, the feedback received was thoroughly reviewed and subjected to statistical analysis using the relative content validity coefficient and the CVI. Based on these analyses, necessary modifications were made, including the deletion, addition, or revision of items.

To evaluate CVR, the Lawshe method was applied [23]. The validated Persian version was then presented to a panel of experts, who were asked to rate the importance and necessity ("necessary," "useful but not necessary," and "not necessary") of items. Additionally, experts assessed each item for clarity, simplicity, and relevance. Items that fell below the predetermined threshold for the relative content validity coefficient, as per the number of experts reviewing the item, were eliminated.

Following the guidelines by Waltz and Bausell for determining the CVI [24], experts were instructed to rate the clarity, simplicity, and relevance of each item based on a 4-point scale. The proportion of experts who selected the top two ratings was calculated against the total number of experts. Items with a resulting value below 0.7 were rejected, those between 0.7 and 0.79 were revised and those with a value above 0.79 were considered acceptable.

To assess the face validity of the scale, cognitive interviews were conducted with 11 mothers from the target group. The process began with an explanation of the research’s objectives, followed by instructing the mother to read each question aloud and then rephrase it in her words. Subsequently, parents were asked if the overall meaning of the question was understandable, whether any words or phrases were confusing if they had any suggestions for improvement, and if the question was culturally and linguistically appropriate for Persian speakers. The findings from these 11 interviews were discussed within the research group, leading to modifications in the second version and the creation of a third iteration. A preliminary study was then conducted to refine the grammar and enhance comprehension.

Acknowledging that an instrument’s psychometric properties may vary with changes in society and sample, factor analysis with PCA was applied to evaluate construct validity among Persian-speaking children. Internal consistency and test-retest were assessed for reliabiliwwty. The Cronbach α coefficient, a widely recognized measure for evaluating internal consistency, is considered acceptable when it exceeds 0.70 [23].

In this study, to ascertain test reliability, the ICC (95% CI) was employed, comparing scores from parents over a two-week interval. Reliability was categorized as weak for correlations below 0.40, moderate for correlations between 0.40 and 0.75 and good for correlations exceeding 0.75 [21, 22].

Study participants and methods

The convenience sampling method was employed to select the parents of children who visited health centers in Tehran City, Iran, from 2021 to 2023. Coordination was established with three medical science universities in Tehran City, Iran, collectively serving approximately 60% of children across three regions: The north and east, the west, and central and south Tehran City, Iran. The researchers then selected the parents of these children. The inclusion criteria specified children aged 1 to 42 months, exhibiting normal growth without developmental or sensory-motor disorders, or any referrals to rehabilitation centers. Meanwhile, the exclusion criterion was for parents who did not speak Persian. Upon receiving approval from the health centers, informed consent was obtained from parents, and they were informed on how to complete the items by the researcher. Subsequently, the parents filled out a demographic questionnaire detailing parental age, gender and education level and completed the adaptive behavior scale.

Data analysis

To assess the structural validity, factor analysis employing PCA was utilized. Before conducting factor analysis, two critical metrics were examined: The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, followed by the calculation of the chi-square value. To determine the saturation of test components with significant factors, three key elements were considered: The eigenvalue, the proportion of variance in each factor explained and the scree plot. Given the significance of calculating the general adaptive composite score in young children, derived from the sum of subscale scores across seven skill areas for children under one year and ten skill areas for those older than one year, factor analysis was conducted for each subscale.

Descriptive statistics were utilized to characterize the study participants. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P<0.01. Data analysis was done using the SPSS software, version 19 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

This study included 130 boys (51.3%) and 123 girls (48.7%), totaling 253 participants. The distribution of the sample group is presented in Table 1.

To assess the face validity, cognitive interviews were conducted with 11 mothers of participants. As a result of these interviews, changes were made to eight items: Functional pre-academic (items 4 and 9), self-direction (item 25), community use (items 16, 18,and 22), motor (item 24) and social skills (item 3) and the titles used for grading.

The CVR for item 25 (communication), items 18, 20, and 22 (community use), items 11, 14, 15, 17, 18 and 21 (functional pre-academic), and item 18 (leisure) was below the minimum acceptable value (0.59); however, the remaining items demonstrated an acceptable CVR, leading to no items being removed.

The CVI regarding relevance for item 25 (communication), items 18 and 22 (community use), items 11, 18, 23 and 22 (functional pre-academic) and the clarity for item 9 (functional pre-academic) scored between 0.7 and 0.79, indicating they required revision. Other items achieved an acceptable CVI value. The KMO measure and the Bartlett test of sphericity values for each subscale are presented in Table 2.

Table 3 reports the eigenvalues and the percentage of variance explained by the first factor within each subscale.

Furthermore, the scree plot (Figure 1) for the subscales suggests that the first factor’s contribution to the total variance was significant and distinct from that of the other factors. To examine the relationships between the items on the scale and define the factors, it was established that coefficients >0.3 significantly contribute to the factor definitions. Consequently, coefficients below this threshold were deemed to represent random factors. The factor loadings, which reflect the correlation of items with the extracted factors, are documented in Table 4.

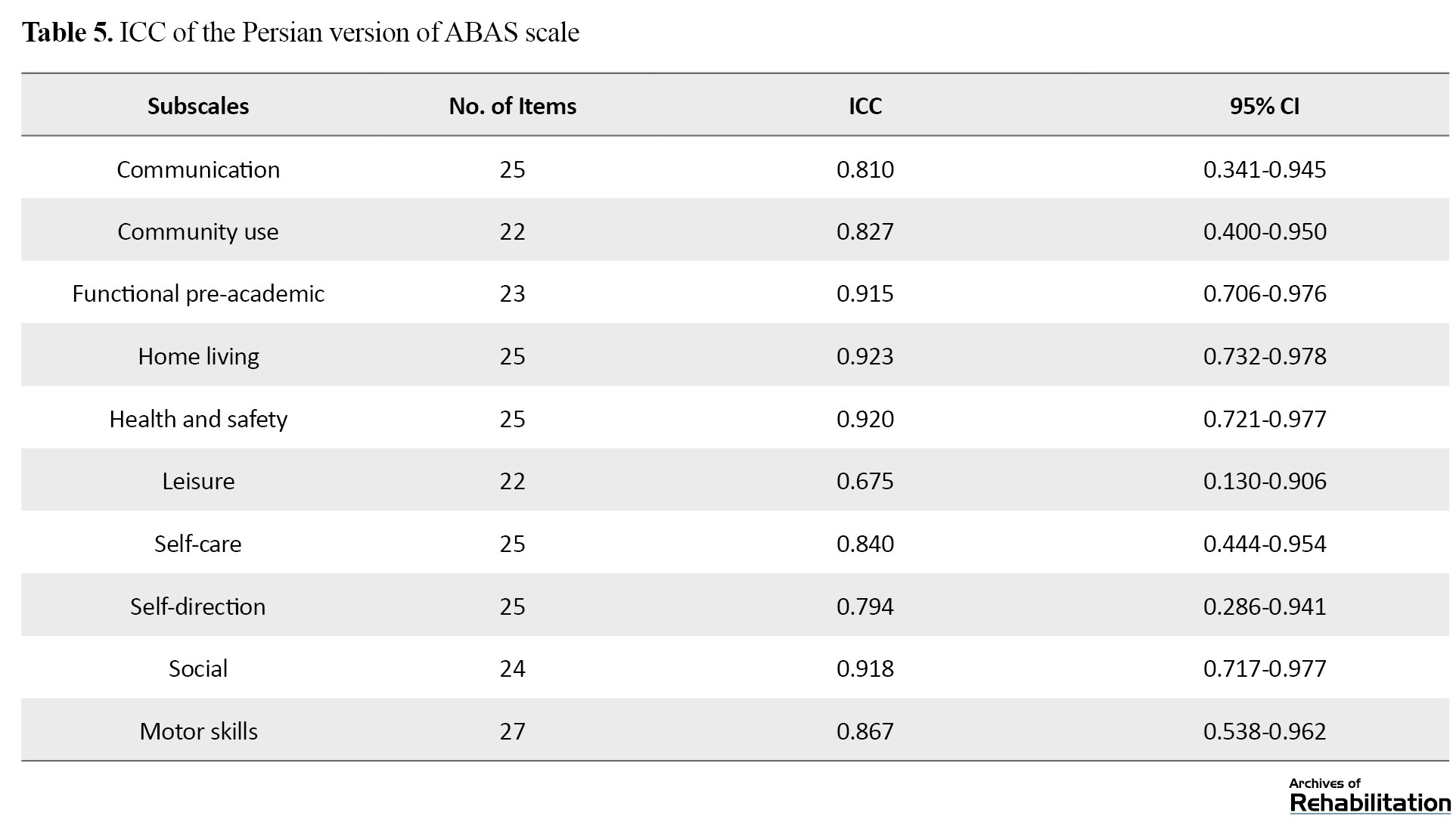

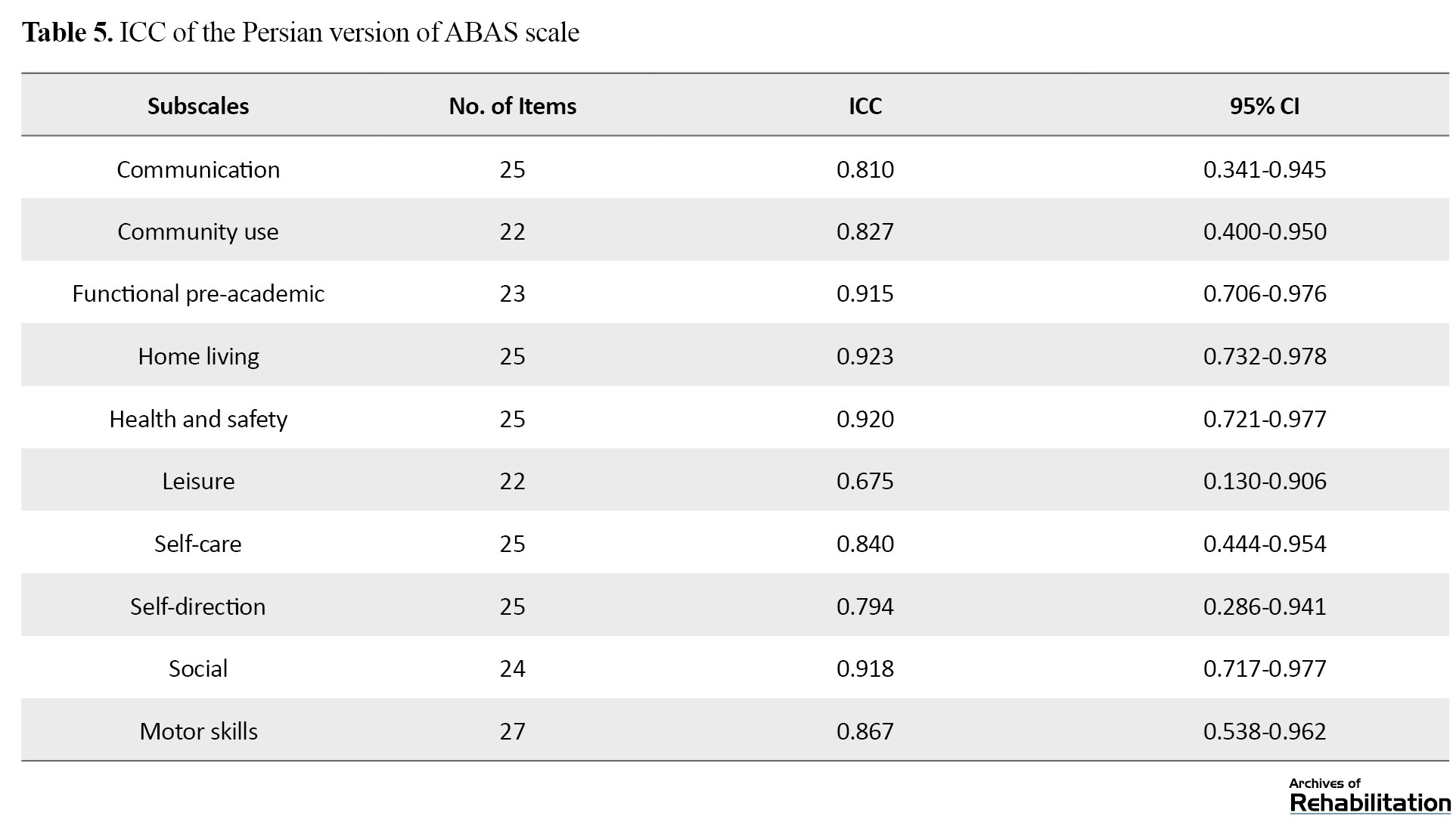

The test reliability was assessed by measuring the ICC, with the results presented in Table 5.

This analysis revealed a good correlation in nine subscales and an average correlation in one subscale.

The internal consistency of the test, determined using the Cronbach α coefficient for the subscales is detailed in Table 6, indicating a value >0.70.

Discussion

In the process of creating and adapting the Persian version of the ABAS, three phases were undertaken: translation, back-translation, and creation of the Persian version. This version underwent several rounds of review and revision by the research group. Subsequently, assessments of face, content, and construct validity were conducted. For face validity, modifications were made to the sub-scale items related to functional pre-academic, self-care, motor and social skills. At this phase, while no items were removed, revisions were made to the content of certain items in consultation with kindergarten teachers and individuals knowledgeable in preschool education. The CVR and CVI for all items were estimated as acceptable. The construct validity of all subscales was verified. The ICC across two parental assessments with a two-week interval demonstrated a good correlation in nine subscales and an average correlation in one. The Cronbach α coefficient exceeded 0.9 for all subscales, reaching 0.991 for the entire scale. On average, nearly 1% of responses were reportedly based on guessing, with the highest proportion of guessing in mothers’ responses about community use and functional pre-academic subscales. This suggests a lack of sufficient education in adaptive skills during the preschool years and a general unfamiliarity among parents with these skills.

One significant challenge researchers and experts encounter in analyzing functional outcomes across various individual and societal levels is developing suitable evaluation scales. When these scales are globally available, the task involves selecting the most fitting one from the options at hand [25]. Researchers typically seek tools that accurately and comprehensively cover their targeted concepts. These concepts are intended to assess the effects of injuries and diseases, evaluate the impact of strategies, interventions, treatments, and rehabilitation programs, monitor patient progress both collectively and individually and ultimately inform clinical decisions regarding the continuation, cessation, or modification of the actions under review. During this process, considerations include the tool’s focus on different target populations, its application through observation or patient inquiries, its psychometric properties and its sub-scales, among other factors [25]. An essential attribute to consider when selecting a tool, as emphasized by experts, is the ease of translating it and the quality of its translation into another language. Designers aim to select words, phrases, and sentences that minimize ambiguity, unfamiliarity, indistinctness, and potential for multiple interpretations, thereby simplifying the translation process and ensuring the tool’s text is as clear as possible in another language [25]. A tool with fluent and unambiguous text enables translators to efficiently produce initial translated versions, facilitating subsequent research stages [26].

In the literature review, factor analysis of the adaptive behavior scale has only been reported for American, Romanian, and Taiwanese versions. Two competing models were tested: A one-factor model and a three-factor model. The latter includes three interrelated factors, namely conceptual, practical and social. The one-factor model supports a composite adaptive behavior score, derived from aggregating scores across all skill domains, while the three-factor model advocates for the utilization of three separate domain scores. A comparison of the adjusted goodness-of-fit index and root mean square error of approximations (RMSEA) values shows a slightly better fit for the three-factor model in the American version and a slightly better acceptable for the one-factor model in the Romanian and Taiwanese versions. The fit indices for all versions fall below the conservative threshold (RMSEA<0.05 or RMSEA<0.08) typically applied in stringent fit criteria. The distinctions between the one and three-factor models are negligible across all three versions. Conservatively interpreted, the analyses do not decidedly favor either the one-factor or three-factor models. Nonetheless, there is slightly stronger support for the three-factor model [27]. In our study, we determined that the most suitable conditions for implementing factor analysis on the items of each subscale favor a one-factor model.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was undertaken for the Arabic version to evaluate its one-factor structure, with the assumption that the ten subscales would converge on one factor. To evaluate the three-factor model, encompassing conceptual, practical, and social factors, CFA was also applied to the entire sample. Overall, the fit indices for the three-factor model demonstrated a poor fit with the data when compared to the one-factor model. Additionally, exploratory factor analysis was employed to investigate the existence of a potentially more apt structure than the two models scrutinized through CFA. Exploratory factor analysis with PCA was conducted on the subscales to explore alternative factor structures that might better represent participant responses. The findings indicated the presence of only one component with an eigenvalue exceeding one [28].

The reliability of scores derived from a tool is a crucial attribute that supports its dependable application in clinical and research contexts, earning attention from researchers. The reliability measurement of scale scores should exhibit two characteristics: Consistency in score values with minimal error when the measured concept remains unchanged. For scales involving multiple questions or tests, score changes should be synchronous, reflecting internal consistency [29]. The ICC of scores yielded a good correlation in nine subscales and a moderate correlation in one subscale.

For ten subscales and a total of 241 items, Cronbach α coefficient exceeded 0.70, indicating an acceptable level of reliability. Concerning other Persian versions of adaptive behavior scales, the standardization of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale for individuals from 1-18 years within the Iranian population was conducted by Tavakkoli et al. in 2019. The re-test coefficients ranged from 0.81 to 0.94 for communication, 0.79 to 0.89 for life skills, 0.80 to 0.88 for social skills, 0.83 to 0.92 for motor skills, and 0.84 to 0.92 for the composite score [16, 17].

Akrami et al. in a 2018 study with adolescents aged 12 to 16 years in Yazd City, Iran, implemented the third edition of the children’s behavior assessment system for both parents and teachers, which evaluates behavioral and adjustment issues in the home and school settings. The Cronbach α coefficient was reported at 0.82 for the clinical scale, 0.87 for the adaptation scale, 0.80 for the content scale, 0.8 for compound scales, 0.82 for introversion, 0.85 for extraversion and 0.89 for the behavior problems index. The Pearson correlation coefficient, through the test-retest method over two administrations, was 0.85 for the parent form and 0.87 for the teacher form in the behavior problems index [30, 31].

Conclusion

The results showed that the ABAS can be easily implemented by parents or caregivers. This scale has suitable validity and reliability in 1-42 months children.

Study limitations

Due to the exceeded number of items and extended response time, the number of respondents in some subscales was less than 253 samples. Due to the age group of the research population (1 to 42 months), it was not possible to determine the differential validity with children with special needs due to the uncertainty of the diagnosis of mental and pervasive developmental disorders in this age group, and because the respondents in this age group are only parents, the Inter-rater reliability was not done.

Future study suggestions

This research examined the validity and reliability of ABAS to measure adaptive behavior in 1-42-month-old children. Considering the problems that parents not being familiar with the concepts of the items in the subscales of community use and pre-primary school functions, especially in the case of children who did not use pre-primary education services, the possibility of parents accessing other methods for these training must be checked. It is recommended that the researchers complete it in several sessions due to the large number of items in this scale.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.283). Written consent was obtained from the main caregiver.

Funding

This study was supported by the Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Grant No. 2746).

Authors' contributions

Research and Fieldwork: Farin Soleimani and Nadia Azari, Zahra Nobakht; Analyzing and writing the draft: Adis Kraskian, Zahra Nobakht, Fateme Hasanati and Zahra Gorbanpour; Methodology, editing and finalization: Farin Soleimani, Zahra Nobakht; Project Management and funding: Farin Soleimani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to acknowledge the families that participated in this study.

Refrences

The concept of adaptive behavior typically refers to an individual’s capacity to take on greater responsibility for themselves and subsequently assist others in developing essential daily life skills. Conducting a thorough and accurate assessment of adaptive behaviors is crucial as it forms the foundation for early identification and subsequent intervention. This information can be gathered from various informants familiar with the behaviors of young children, or through reliable tests. Assessing the behavior of children from birth to 5 years old often presents challenges due to changes in behavior and the difficulty in engaging them in the assessment process. Utilizing adaptive behavior scales can mitigate some of these challenges, making them a common tool for evaluating young children [1, 2]. Adaptive skills in children, such as social self-care, communication, social behaviors, and motor skills, develop in response to their living environments. These along with other adaptive skills are essential for sufficient and independent performance at home, in school and within the community. Early disruptions in these skills can predict more persistent disorders later on. Consequently, early intervention based on accurate and practical assessments can reduce or even prevent the emergence of chronic conditions [3]. Additionally, specialists can assess adaptive behavior to determine the performance levels of individuals with various disorders.

Throughout the 20th century, the evaluation of adaptive behavior emerged as an essential factor for diagnosing mental retardation and devising interventions for individuals with this condition [3]. According to the 2002 definition by the American Association for Mental Retardation, adaptive behavior is categorized into three domains: conceptual, social and practical, all of which are essential for daily functioning [4]. Moreover, current diagnostic and classification systems, including the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, American Association for Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, and International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision, share three universal criteria for confirming or dismissing a diagnosis of intellectual disability (ID): a) Notable restrictions in intellectual functioning, b) Notable restrictions in adaptive behavior and c) Onset during the period of development [5, 6, 7, 8]. Since 2002, the significance of adaptive behavior’s structure and its importance in identifying intellectual disability have been established [4, 9, 10]. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition moves away from relying solely on intelligence quotient scores to measure the severity of intellectual disability, rather employing adaptive behavior assessments as a measure of severity [5]. Although over 200 adaptive behavior scales exist, only four have been standardized with criteria for testing, and a limited number have been known to be particularly effective in the diagnosis of intellectual disability [7, 11]. The four instruments standardized for US samples include the Vineland adaptive behavior scales [12], the adaptive behavior assessment system (ABAS) [13], the scales of independent behavior-revised [14] and the school function assessment [15].

Determining the instrument’s validity, sensitivity and specificity is important. For instance, concerning the ABAS, its authors noted that the average scores for the group with developmental disabilities were significantly less than those for the normative group [15]. However, they did not disclose the exact percentage of individuals accurately identified; thus, the precision of the school ABAS in correctly diagnosing someone with a developmental disability remains uncertain.

In the comprehensive manual for the revised independent behavior scale, Bruininks et al. [14] offered a more thorough analysis of sensitivity and specificity. They reported that 76% of individuals in the standard sample were accurately classified into their respective groups: 51% in the group with mild, 74% with moderate, and 82% without disability. From a decision-making standpoint, the lowest accuracy rate (i.e. 51% sensitivity) on the revised independent behavior scale was observed in the group with mild disability, given the narrow margin for differentiating this group from the normative group. Nonetheless, if only half of those diagnosed with mild intellectual disability have scores indicative of such a diagnosis, the revised independent behavior scale might lack the sensitivity required for accurately distinguishing individuals with mild conditions from those with mental retardation. Moreover, while the revised independent behavior scale spans various age groups from infancy onwards, it does not provide sensitivity and specificity figures for distinct age categories. On the Vineland adaptive behavior scales, the accuracy of classification ranged from 71% to 100% among individuals aged 6 to 18 years (71% for mild, 87% for moderate, and 100% for severe disability). The Vineland adaptive behavior scales also offer data on sensitivity across different skill domains (e.g. daily living skills, communication, social skills, and motor skills). However, details regarding the rate at which individuals were correctly diagnosed with a disability (i.e. specificity) have not been reported [12].

ABAS stands out as a reliable questionnaire for evaluating adaptive behavior in children. Initially designed for individuals aged 5 to 89 years, its second version extends its applicability to ages 0 to 89 years. ABAS includes four different forms targeting parents (for children aged birth to 21 years), teachers (for children and young adults aged 5 to 21 years) and adults (aged 16 to 89 years), with two assessment options available: Self-assessment or assessment by others, across various age categories. This scale provides normative scores across 10 skill areas covering community use, communication, functional pre-academic, home living, health and safety, leisure, self-care, self-direction, social and motor skills, all with an average score of 10 and a standard deviation of 3. It offers standard scores for conceptual, social and practical domains, alongside a general adaptive composite score with an average of 100, a standard deviation of 15, 90% and 95% confidence intervals (CI) and percentile rankings [13].

The adaptive behavior scales in the Persian language is the survey form of Vineland adaptive behavior scales that have been standardized for individuals from birth to 18 years [16, 17]. The Vineland scales feature three forms: The survey interview, parent/caregiver rating, expanded interview, and teacher rating. This form assesses the following four domains: Communication, daily living skills, socialization, motor skills, and maladaptive behavior. Another notable Persian adaptive behavior questionnaire is the third edition of the children’s behavior assessment system, designed for parents and teachers. It was administered to a cohort of adolescents aged 12 to 16 years in Yazd City, Iran [18]. This questionnaire extensively evaluates emotional challenges within school and clinical settings, offering multiple assessments to aid in the identification and development of treatment plans, including a comprehensive evaluation of both externalized and internalized behavioral symptoms [19]. Furthermore, the indicators of this questionnaire play an important role in diagnosing various disorders [18].

One of the primary challenges faced by researchers and professionals in analyzing functional outcomes across various individual and societal levels is the creation of suitable scales for assessment. When these scales are internationally available, the task becomes selecting the most appropriate one from the existing tools. The goal of this selection process is to find tools that best satisfy the clinical and research needs of researchers, enabling them to evaluate the effects of injuries and diseases, the impact of strategies, interventions, treatment, and rehabilitation programs, monitor patient progress, and ultimately make clinical decisions about whether to continue, halt, or adjust these actions. Factors such as the tool’s focus on different target populations, its application through observation or patient interviews, its psychometric properties, its sub-scales, etc. are considered during this process.

Given the absence of a comprehensive and suitable tool for assessing adaptive behavior and evaluating this aspect of development in young children across various skill areas, and considering the high validity and reliability of the ABAS, along with its coverage of ten primary skill areas in young children (including communication, community use, functional pre-academic, home living, health and safety, leisure, self-care, self-direction, social skills and motor skills) as rated by parents and caregivers, this study translates and culturally adapts ABAS and then assesses the validity and reliability of its Persian version for use by researchers and the healthcare system in early detection and intervention in behavioral disorders.

Materials and Methods

This study employed a methodological approach. The Persian version of the ABAS was created through a meticulous process of translation and back-translation. The translation to Persian and the cross-cultural adaptation of the ABAS followed the international quality of life assessment project approach guidelines [20]. Initially, two independent translators, both fluent in Persian and English and knowledgeable about children’s adaptive behavior development, translated the original scale from English to Persian. These versions were then reviewed by the research team, resulting in the first Persian draft. This draft was subsequently translated back into English by two native English speakers. The research group convened to compare these re-translated versions with the original English text, identify any translation discrepancies, and produce a second Persian draft. This version was then evaluated by 11 experts in child development, including psychologists, pediatricians specialized in child development, occupational therapists and child psychiatrists, for face and content validity. Their feedback led to cultural and linguistic modifications. Additionally, to assess face validity, cognitive interviews were conducted with 11 mothers of children aged 1 to 42 months. The research team reviewed their feedback, leading to the final version of the instrument. For structural validity, factor analysis using principal component analysis (PCA) was applied. The Cronbach α and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with a 95% CI were calculated to assess test-retest reliability and internal consistency, respectively. Given the absence of a specific formula for estimating sample size in studies evaluating the validity and reliability of tests, and using of factor analysis method in this research, it was recommended to have a minimum sample of 200 individuals for a vigorous assessment of construct validity [21]. Thus, a target sample size of 200 children was set, ultimately including 253 parents of children aged 1 to 42 months in the study.

Study instruments

In this study, the second edition of ABAS by Harrison and Oakland (2003) was utilized to evaluate the daily functional abilities of children aged 0-5 years. This scale identifies the skills a child currently has or is likely to develop in the future. The ABAS functions as a screening tool across ten skill domains. For children under one year of age, the scale evaluates the following seven skill domains: Communication, health and safety, leisure, self-care, self-direction, social skills, and motor skills. For children aged 1 to 5 years, it assesses ten skill domains as follows: Communication, community use, Functional pre-academic, home living, health and safety, leisure, self-care, self-direction, social, and motor skills. The assessment is completed by parents or caregivers and aims to measure significant behaviors demonstrated by the child at home, in preschool settings, and other contexts [13].

The scoring range for this scale spans from 0 ("Is not able") to 3 ("Always when needed"), with the scoring conducted by the respondent. Concurrently, the respondent denotes whether the behavior was directly observed or is based on a guess about its repetition and frequency. If the scoring is speculative, the respondent marks a check (√) in the box labeled check if you guessed. If the assessment is based on direct observation or firsthand knowledge, this column is left blank. The scale assesses the child’s abilities in 7 to 10 domains according to age, as follows: Communication, which includes 25 questions; community use, comprising 22 questions about interest in external activities and recognizing different facilities; functional pre-academic, with 23 questions on letter recognition, counting and simple drawing; home living, including 25 questions about assisting with daily tasks and managing personal belongings; health and safety, with 24 questions on precaution and avoiding physical hazards; leisure, comprising 22 questions on the play, game rules adherence, and creativity at home; self-care, including 24 questions on eating, toileting, and bathing; self-direction, with 25 questions on self-control, rule adherence, and making choices; social skills, comprising 24 questions on empathy, assistance, emotional and mental state recognition, and etiquette; and motor skills, with 27 questions on moving and manipulating objects in the environment [22].

The original version’s reliability coefficients in the parent form for conceptual, social and practical domains were reported as 96%, 94% and 96%, respectively. Inter-rater reliability among parents and teachers for the 10 skill domains was reported in the range of 60-70%. Additionally, the correlation between the school-age teacher form and the Vineland adaptive behavior scales-classroom Version was 82% [13].

Reliability and validity

The content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were employed to quantitatively assess content validity. Following the survey questionnaires, the feedback received was thoroughly reviewed and subjected to statistical analysis using the relative content validity coefficient and the CVI. Based on these analyses, necessary modifications were made, including the deletion, addition, or revision of items.

To evaluate CVR, the Lawshe method was applied [23]. The validated Persian version was then presented to a panel of experts, who were asked to rate the importance and necessity ("necessary," "useful but not necessary," and "not necessary") of items. Additionally, experts assessed each item for clarity, simplicity, and relevance. Items that fell below the predetermined threshold for the relative content validity coefficient, as per the number of experts reviewing the item, were eliminated.

Following the guidelines by Waltz and Bausell for determining the CVI [24], experts were instructed to rate the clarity, simplicity, and relevance of each item based on a 4-point scale. The proportion of experts who selected the top two ratings was calculated against the total number of experts. Items with a resulting value below 0.7 were rejected, those between 0.7 and 0.79 were revised and those with a value above 0.79 were considered acceptable.

To assess the face validity of the scale, cognitive interviews were conducted with 11 mothers from the target group. The process began with an explanation of the research’s objectives, followed by instructing the mother to read each question aloud and then rephrase it in her words. Subsequently, parents were asked if the overall meaning of the question was understandable, whether any words or phrases were confusing if they had any suggestions for improvement, and if the question was culturally and linguistically appropriate for Persian speakers. The findings from these 11 interviews were discussed within the research group, leading to modifications in the second version and the creation of a third iteration. A preliminary study was then conducted to refine the grammar and enhance comprehension.

Acknowledging that an instrument’s psychometric properties may vary with changes in society and sample, factor analysis with PCA was applied to evaluate construct validity among Persian-speaking children. Internal consistency and test-retest were assessed for reliabiliwwty. The Cronbach α coefficient, a widely recognized measure for evaluating internal consistency, is considered acceptable when it exceeds 0.70 [23].

In this study, to ascertain test reliability, the ICC (95% CI) was employed, comparing scores from parents over a two-week interval. Reliability was categorized as weak for correlations below 0.40, moderate for correlations between 0.40 and 0.75 and good for correlations exceeding 0.75 [21, 22].

Study participants and methods

The convenience sampling method was employed to select the parents of children who visited health centers in Tehran City, Iran, from 2021 to 2023. Coordination was established with three medical science universities in Tehran City, Iran, collectively serving approximately 60% of children across three regions: The north and east, the west, and central and south Tehran City, Iran. The researchers then selected the parents of these children. The inclusion criteria specified children aged 1 to 42 months, exhibiting normal growth without developmental or sensory-motor disorders, or any referrals to rehabilitation centers. Meanwhile, the exclusion criterion was for parents who did not speak Persian. Upon receiving approval from the health centers, informed consent was obtained from parents, and they were informed on how to complete the items by the researcher. Subsequently, the parents filled out a demographic questionnaire detailing parental age, gender and education level and completed the adaptive behavior scale.

Data analysis

To assess the structural validity, factor analysis employing PCA was utilized. Before conducting factor analysis, two critical metrics were examined: The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity, followed by the calculation of the chi-square value. To determine the saturation of test components with significant factors, three key elements were considered: The eigenvalue, the proportion of variance in each factor explained and the scree plot. Given the significance of calculating the general adaptive composite score in young children, derived from the sum of subscale scores across seven skill areas for children under one year and ten skill areas for those older than one year, factor analysis was conducted for each subscale.

Descriptive statistics were utilized to characterize the study participants. The threshold for statistical significance was set at P<0.01. Data analysis was done using the SPSS software, version 19 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

This study included 130 boys (51.3%) and 123 girls (48.7%), totaling 253 participants. The distribution of the sample group is presented in Table 1.

To assess the face validity, cognitive interviews were conducted with 11 mothers of participants. As a result of these interviews, changes were made to eight items: Functional pre-academic (items 4 and 9), self-direction (item 25), community use (items 16, 18,and 22), motor (item 24) and social skills (item 3) and the titles used for grading.

The CVR for item 25 (communication), items 18, 20, and 22 (community use), items 11, 14, 15, 17, 18 and 21 (functional pre-academic), and item 18 (leisure) was below the minimum acceptable value (0.59); however, the remaining items demonstrated an acceptable CVR, leading to no items being removed.

The CVI regarding relevance for item 25 (communication), items 18 and 22 (community use), items 11, 18, 23 and 22 (functional pre-academic) and the clarity for item 9 (functional pre-academic) scored between 0.7 and 0.79, indicating they required revision. Other items achieved an acceptable CVI value. The KMO measure and the Bartlett test of sphericity values for each subscale are presented in Table 2.

Table 3 reports the eigenvalues and the percentage of variance explained by the first factor within each subscale.

Furthermore, the scree plot (Figure 1) for the subscales suggests that the first factor’s contribution to the total variance was significant and distinct from that of the other factors. To examine the relationships between the items on the scale and define the factors, it was established that coefficients >0.3 significantly contribute to the factor definitions. Consequently, coefficients below this threshold were deemed to represent random factors. The factor loadings, which reflect the correlation of items with the extracted factors, are documented in Table 4.

The test reliability was assessed by measuring the ICC, with the results presented in Table 5.

This analysis revealed a good correlation in nine subscales and an average correlation in one subscale.

The internal consistency of the test, determined using the Cronbach α coefficient for the subscales is detailed in Table 6, indicating a value >0.70.

Discussion

In the process of creating and adapting the Persian version of the ABAS, three phases were undertaken: translation, back-translation, and creation of the Persian version. This version underwent several rounds of review and revision by the research group. Subsequently, assessments of face, content, and construct validity were conducted. For face validity, modifications were made to the sub-scale items related to functional pre-academic, self-care, motor and social skills. At this phase, while no items were removed, revisions were made to the content of certain items in consultation with kindergarten teachers and individuals knowledgeable in preschool education. The CVR and CVI for all items were estimated as acceptable. The construct validity of all subscales was verified. The ICC across two parental assessments with a two-week interval demonstrated a good correlation in nine subscales and an average correlation in one. The Cronbach α coefficient exceeded 0.9 for all subscales, reaching 0.991 for the entire scale. On average, nearly 1% of responses were reportedly based on guessing, with the highest proportion of guessing in mothers’ responses about community use and functional pre-academic subscales. This suggests a lack of sufficient education in adaptive skills during the preschool years and a general unfamiliarity among parents with these skills.

One significant challenge researchers and experts encounter in analyzing functional outcomes across various individual and societal levels is developing suitable evaluation scales. When these scales are globally available, the task involves selecting the most fitting one from the options at hand [25]. Researchers typically seek tools that accurately and comprehensively cover their targeted concepts. These concepts are intended to assess the effects of injuries and diseases, evaluate the impact of strategies, interventions, treatments, and rehabilitation programs, monitor patient progress both collectively and individually and ultimately inform clinical decisions regarding the continuation, cessation, or modification of the actions under review. During this process, considerations include the tool’s focus on different target populations, its application through observation or patient inquiries, its psychometric properties and its sub-scales, among other factors [25]. An essential attribute to consider when selecting a tool, as emphasized by experts, is the ease of translating it and the quality of its translation into another language. Designers aim to select words, phrases, and sentences that minimize ambiguity, unfamiliarity, indistinctness, and potential for multiple interpretations, thereby simplifying the translation process and ensuring the tool’s text is as clear as possible in another language [25]. A tool with fluent and unambiguous text enables translators to efficiently produce initial translated versions, facilitating subsequent research stages [26].

In the literature review, factor analysis of the adaptive behavior scale has only been reported for American, Romanian, and Taiwanese versions. Two competing models were tested: A one-factor model and a three-factor model. The latter includes three interrelated factors, namely conceptual, practical and social. The one-factor model supports a composite adaptive behavior score, derived from aggregating scores across all skill domains, while the three-factor model advocates for the utilization of three separate domain scores. A comparison of the adjusted goodness-of-fit index and root mean square error of approximations (RMSEA) values shows a slightly better fit for the three-factor model in the American version and a slightly better acceptable for the one-factor model in the Romanian and Taiwanese versions. The fit indices for all versions fall below the conservative threshold (RMSEA<0.05 or RMSEA<0.08) typically applied in stringent fit criteria. The distinctions between the one and three-factor models are negligible across all three versions. Conservatively interpreted, the analyses do not decidedly favor either the one-factor or three-factor models. Nonetheless, there is slightly stronger support for the three-factor model [27]. In our study, we determined that the most suitable conditions for implementing factor analysis on the items of each subscale favor a one-factor model.

A confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was undertaken for the Arabic version to evaluate its one-factor structure, with the assumption that the ten subscales would converge on one factor. To evaluate the three-factor model, encompassing conceptual, practical, and social factors, CFA was also applied to the entire sample. Overall, the fit indices for the three-factor model demonstrated a poor fit with the data when compared to the one-factor model. Additionally, exploratory factor analysis was employed to investigate the existence of a potentially more apt structure than the two models scrutinized through CFA. Exploratory factor analysis with PCA was conducted on the subscales to explore alternative factor structures that might better represent participant responses. The findings indicated the presence of only one component with an eigenvalue exceeding one [28].

The reliability of scores derived from a tool is a crucial attribute that supports its dependable application in clinical and research contexts, earning attention from researchers. The reliability measurement of scale scores should exhibit two characteristics: Consistency in score values with minimal error when the measured concept remains unchanged. For scales involving multiple questions or tests, score changes should be synchronous, reflecting internal consistency [29]. The ICC of scores yielded a good correlation in nine subscales and a moderate correlation in one subscale.

For ten subscales and a total of 241 items, Cronbach α coefficient exceeded 0.70, indicating an acceptable level of reliability. Concerning other Persian versions of adaptive behavior scales, the standardization of the Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale for individuals from 1-18 years within the Iranian population was conducted by Tavakkoli et al. in 2019. The re-test coefficients ranged from 0.81 to 0.94 for communication, 0.79 to 0.89 for life skills, 0.80 to 0.88 for social skills, 0.83 to 0.92 for motor skills, and 0.84 to 0.92 for the composite score [16, 17].

Akrami et al. in a 2018 study with adolescents aged 12 to 16 years in Yazd City, Iran, implemented the third edition of the children’s behavior assessment system for both parents and teachers, which evaluates behavioral and adjustment issues in the home and school settings. The Cronbach α coefficient was reported at 0.82 for the clinical scale, 0.87 for the adaptation scale, 0.80 for the content scale, 0.8 for compound scales, 0.82 for introversion, 0.85 for extraversion and 0.89 for the behavior problems index. The Pearson correlation coefficient, through the test-retest method over two administrations, was 0.85 for the parent form and 0.87 for the teacher form in the behavior problems index [30, 31].

Conclusion

The results showed that the ABAS can be easily implemented by parents or caregivers. This scale has suitable validity and reliability in 1-42 months children.

Study limitations

Due to the exceeded number of items and extended response time, the number of respondents in some subscales was less than 253 samples. Due to the age group of the research population (1 to 42 months), it was not possible to determine the differential validity with children with special needs due to the uncertainty of the diagnosis of mental and pervasive developmental disorders in this age group, and because the respondents in this age group are only parents, the Inter-rater reliability was not done.

Future study suggestions

This research examined the validity and reliability of ABAS to measure adaptive behavior in 1-42-month-old children. Considering the problems that parents not being familiar with the concepts of the items in the subscales of community use and pre-primary school functions, especially in the case of children who did not use pre-primary education services, the possibility of parents accessing other methods for these training must be checked. It is recommended that the researchers complete it in several sessions due to the large number of items in this scale.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.283). Written consent was obtained from the main caregiver.

Funding

This study was supported by the Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center affiliated with the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Grant No. 2746).

Authors' contributions

Research and Fieldwork: Farin Soleimani and Nadia Azari, Zahra Nobakht; Analyzing and writing the draft: Adis Kraskian, Zahra Nobakht, Fateme Hasanati and Zahra Gorbanpour; Methodology, editing and finalization: Farin Soleimani, Zahra Nobakht; Project Management and funding: Farin Soleimani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors like to acknowledge the families that participated in this study.

Refrences

- Sattler JM, Hoge RD. Assessment of children: Behavioral, social, and clinical foundations. San Diego: Publisher Inc. 2006. [Link]

- Alfonso VC, Bracken BA, Nagle RJ. PsychoeducationAL ASsessment of preschool children. New York: Routledge; 2020. [DOI:10.4324/9780429054099]

- Oakland T, Algina J. Adaptive behavior assessment system-II parent/primary caregiver form: Ages 0-5: Its factor structure and other implications for practice. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2011; 27(2):103-17. [DOI:10.1080/15377903.2011.565267]

- Luckasson R, Borthwick-Duffy S, Buntinx WH, Coulter DL, Craig EMP, Reeve A, et al. Mental retardation: Definition, classification, and systems of supports. Silver Spring: American Association on Mental Retardation; 2002. [Link]

- Edition F. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. American Psychiatric Association. 2013; 21(21):591-643. [Link]

- Schalock RL, Borthwick-Duffy SA, Bradley VJ, Buntinx WH, Coulter DL, Craig EM, et al. Intellectual disability: Definition, classification, and systems of supports. Washington DC: American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; 2010. [Link]

- Braddock DL, Schalock RL. Adaptive behavior and its measurement: Implications for the field of mental retardation. Washington DC: Amer Assn on Intellectual & Devel; 1999. [Link]

- Balboni G, Tassé MJ, Schalock RL, Borthwick-Duffy SA, Spreat S, Thissen D, et al. The diagnostic adaptive behavior scale: Evaluating its diagnostic sensitivity and specificity. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014; 35(11):2884-93. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.07.032]

- Harrison PL. Scientific practitioner: Adaptive behavior: Research to practice. Journal of School Psychology. 1989; 27(3):301-17. [DOI:10.1016/0022-4405(89)90045-9]

- Greenspan S, Granfield JM. Reconsidering the construct of mental retardation: Implications of a model of social competence. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1992; 96(4):442-53. [PMID]

- Tassé MJ, Schalock RL, Balboni G, Bersani Jr H, Borthwick-Duffy SA, Spreat S, et al. The construct of adaptive behavior: Its conceptualization, measurement, and use in the field of intellectual disability. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2012; 117(4):291-303. [DOI:10.1352/1944-7558-117.4.291]

- Sparrow S, Balla D, Cicchetti D. Vineland-S. Göttingen: Hogrefe Publishing; 2016. [Link]

- Harrison P. Oakland T. Adaptive behavior assessment system System-II: Clinical use and interpretation. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2011. [Link]

- Bruininks R, McGrew K, Maruyama G. Structure of adaptive behavior in samples with and without mental retardation. American Journal of Mental Retardation. 1988; 93(3):265-72. [PMID]

- Lambert N, Nihira K, Leland H. ABS-S 2: AAMR adaptive behavior scale: School. Austin: Pro-ed; 1993. [Link]

- Tavakkoli MA, Baghooli H, Ghamat Boland HR, Bolhari J, Birashk B. [Standardizing vineland adaptive behavior scale among iranian population (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2000; 5(4):27-37. [Link]

- Zamyad A, Yasemi M, Vaezi SA. [Preliminary Standardization of Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scale in Urban and Rural Population of Kerman (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 1996; 2(4):44-55. [Link]

- Akrami L, Malekpour M, Abedi A. Developing and accessing psychometric properties of the persian version of behavior assessment system for children in children with mild intellectual disabilities and normal children. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology. 2021; 27(3):388-405. [DOI:10.32598/ijpcp.27.4.3462.1]

- Bradstreet LE, Juechter JI, Kamphaus RW, Kerns CM, Robins DL. Using the BASC-2 parent rating scales to screen for autism spectrum disorder in toddlers and preschool-aged children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2017; 45:359-70. [DOI:10.1007/s10802-016-0167-3]

- Bullinger M, Alonso J, Apolone G, Leplege A, Sullivan M, Wood-Dauphinee S, et al. Translating health status questionnaires and evaluating their quality: The IQOLA project approach. international quality of life assessment. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1998; 51(11):913-23. [DOI:10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00082-1]

- Comrey AL, Lee HB. A first course in factor analysis. New York: Psychology press; 2013. [DOI:10.4324/9781315827506]

- Pearson. Harrison PL OT. London: Pearson; 2012. [Link]

- Ayre C, Scally AJ. Critical values for Lawshe’s content validity ratio: Revisiting the original methods of calculation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2014; 47(1):79-86. [DOI:10.1177/0748175613513808]

- Waltz CF, Bausell BR. Nursing research: Design statistics and computer analysis. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis; 1981. [Link]

- Khosrozade F. [Evaluation and validity of the Persian version of the LCI5 questionnaire in lower limb amputees in Iran (Persian)] [MA thesis]. Tehran: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences; 2010. [Link]

- Bahrami H. [Psychological tests: Theoretical foundations and applied techniques (Persian)]. Tehran: Allameh Tabataba'i University; 2014. [Link]

- Oakland T, Iliescu D, Chen HY, Chen JH. Cross-national assessment of adaptive behavior in three countries. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 2013; 31(5):435-47. [DOI:10.1177/0734282912469492]

- Mohamed Emam M, Al-Sulaimani H, Omara E, Al-Nabhany R. Assessment of adaptive behaviour in children with intellectual disability in Oman: An examination of ABAS-3 factor structure and validation in the Arab context. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities. 2020; 66(4):317-26. [DOI:10.1080/20473869.2019.1587939]

- Fardipor S, Salvati M, Bahrami Zadeh M, Hadadi M, Mazaheri M. [Cross-cultural adaptation and evaluation of validity and reliability of trinity amputation and prosthesis experience scales in an iranian people with lower limb amputation (Persian)]. Koomesh. 2011; 12(4):413-8. [Link]

- Akrami L, Malekpur M, Faramarzi S, Abedi A. [The effect of behavioral management and social skills training program on behavioral and adaptive problems of male adolescents with high-functioning autism (Persian)]. Archives of Re-habilitation. 2020; 20(4):322-39. [DOI:10.32598/rj.20.4.322]

- Akrami L, Malekpour M, Abedi A. [The impact of kate ripley program on behavioral problems and adaptive skills of boys with high-functioning autism (Persian)]. Journal of Modern Psychological Researches. 2020; 15(58):124-39. [Link]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Pediatric Neurology

Received: 17/09/2023 | Accepted: 18/08/2024 | Published: 1/11/2024

Received: 17/09/2023 | Accepted: 18/08/2024 | Published: 1/11/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |