Volume 25, Issue 2 (Summer 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(2): 180-207 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Alizadeh T, Bahmani B, khanjani M S, Azkhosh M, Shakiba S, Vahedi M. Psychosocial Experiences and Support Resources of People With Albinism: A Thematic Synthesis. jrehab 2024; 25 (2) :180-207

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3277-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3277-en.html

Taher Alizadeh1

, Bahman Bahmani *2

, Bahman Bahmani *2

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani1

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani1

, Manouchehr Azkhosh1

, Manouchehr Azkhosh1

, Shima Shakiba3

, Shima Shakiba3

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Bahman Bahmani *2

, Bahman Bahmani *2

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani1

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani1

, Manouchehr Azkhosh1

, Manouchehr Azkhosh1

, Shima Shakiba3

, Shima Shakiba3

, Mohsen Vahedi4

, Mohsen Vahedi4

1- Department of Counselling, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Counselling, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,bbahmani43@yahoo.com

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Counselling, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 3450 kb]

(1318 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5422 Views)

Full-Text: (2228 Views)

Introduction

Albinism is derived from the Latin word “albus”, meaning white. This word shows an outward description of the condition of the sufferers. Oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) is a rare autosomal recessive, inherited, non-transmissible disorder that is associated with a significant reduction or absence of pigmentation in the skin, hair, and eyes. This disorder is incurable and can be found in any population worldwide, regardless of gender and ethnicity [1]. Melanin is a pigment that protects the skin from ultraviolet rays and helps produce color [1]. Since people with albinism (PWA) have a complete lack or reduction in melanin biosynthesis, which causes white and pale skin and hair that become sensitive to sunburn, the lack of melanin, which is a skincare factor, increases the risk of skin cancer in these people. If proper care measures are not taken, only a few of these people will survive to the age of 40 years [2]. A rarer form of albinism, known as ocular albinism, affects only the eyes of the affected person. Albinism causes problems and defects related to vision, such as reduced visual acuity, involuntary eye movements, deviation, and sensitivity to light [3]. This genetic disease begins at birth and continues until the end of life, and in case both parents are affected or carry the albinism gene, they are likely to pass it on to their children [4]. In Iran, there are no official statistics about the number of PWA; however, according to estimates, it can reach 35000 people [5]. In most regions of the world, the prevalence of albinism is approximately 1 in every 20000 people; nevertheless, in some areas, such as East African countries, this number is 1 in every 1000. This trend is also increasing [6]. These people are exposed to many challenges, discrimination, and abuses since childhood. In social environments, they suffer all kinds of academic challenges, ridicule, rejection, stigma, and physical and sexual violence [7]. In addition, PWA faces many challenges in communicating with others due to their different appearance and limitations caused by albinism. The conditions of PWA in some parts of Africa have been complicated, and these people have been threatened, persecuted, and even killed and mutilated due to superstitions and myths related to albinism, which cause constant worries and isolation. Meanwhile, these people have withdrawn from social situations [8, 9]. Numerous qualitative studies have been conducted on the experiences of PWA in African countries. However, in other regions of the world, such as Iran, studies that investigate the psychosocial experiences of PWA are limited. In Iran, the psychological experiences of this population have been investigated in studies by Alizadeh et al. [5] and Zamani et al. [10].

Compared to other diseases that do not have a negative impact on the baby’s appearance from the beginning (such as hemophilia), in albinism, the possibility of establishing a sufficient connection and healthy support, mother-infant, is reduced and can increase the possibility of attachment problems in these people. Therefore, the insecure attachment style increases the probability of many problems and mental disorders, such as depression [11], social anxiety [12], substance dependence disorders [13]; therefore, probably most people with albinism, due to problems and disorders related to the skin, hair, and eyes, have been exposed to wide psychological consequences, such as depression, anxiety, suicide, body deformity, obsession, and so on. Meanwhile, since the main focus of qualitative research in African countries is on the concepts of stigma and discrimination and issues related to killing, the psychological and coping issues of these people against tensions have not been considered sufficiently. Given the limitations of this type of study in Iran, presenting a comprehensive picture of the psycho-social experiences of PWA in the field of health, rehabilitation, and psychologists can help in planning and designing educational and treatment packages for a better understanding of albinism and the problems of this population. Also, because of the limitations that are directly and indirectly caused by albinism, PWA experience difficult conditions concerning family, teachers, peers, and friends; hence, providing a direct understanding of their experiences and conditions can help other non-specialist populations, such as families, teachers, and other people who are involved with the problem of albinism to help them experience healthier and harm-free relationships. Accordingly, this study identifies and combines the available evidence from the existing literature to provide a better understanding of the psycho-social experiences of PWA.

Materials and Methods

Analysis method

This is a thematic synthesis type review study which is one of the available methods for synthesis qualitative research [14]. Data extraction, analysis, and synthesis of this review follow the approach of thematic synthesis of Thomas and Harden [15], which transforms the concept of thematic analysis of primary data into secondary data. First, the primary studies were coded line by line. Descriptive themes were created from the themes that appeared initially, and finally, by going beyond the descriptive themes, analytical themes were generated. This approach moves beyond the findings of the main research to build a new and comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of albinism.

Search strategy

Relevant studies until January 2023 were identified using a structured search strategy in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Magiran databases. No time limit was applied in searching the databases. A manual search was also done in the index of some African journals (due to the higher prevalence of albinism in Africa), such as Society and Disability, African Journal of Disability, African Identities, and Journal of African Cultural Studies. Meanwhile, the Google Scholar search engine and the list of related study sources were searched for potential studies. No related Persian articles were found in the search and all the found articles were in English. The search strategy is presented in Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Qualitative studies that described the psychosocial experiences and perceptions of PWA were included, and studies that examined the perceptions and experiences of caregivers and those around them or used quantitative methods were excluded from the research.

Data selection and extraction

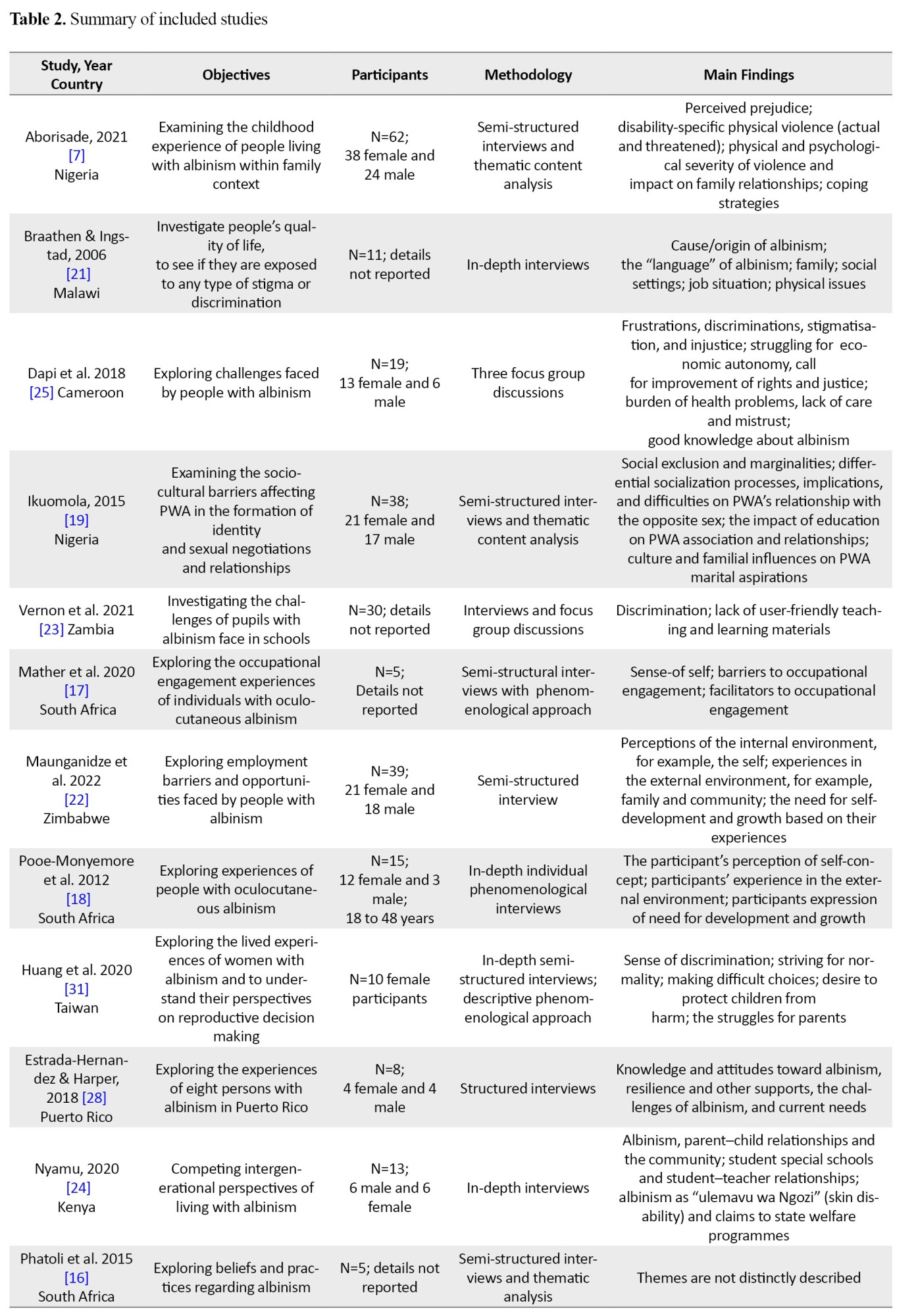

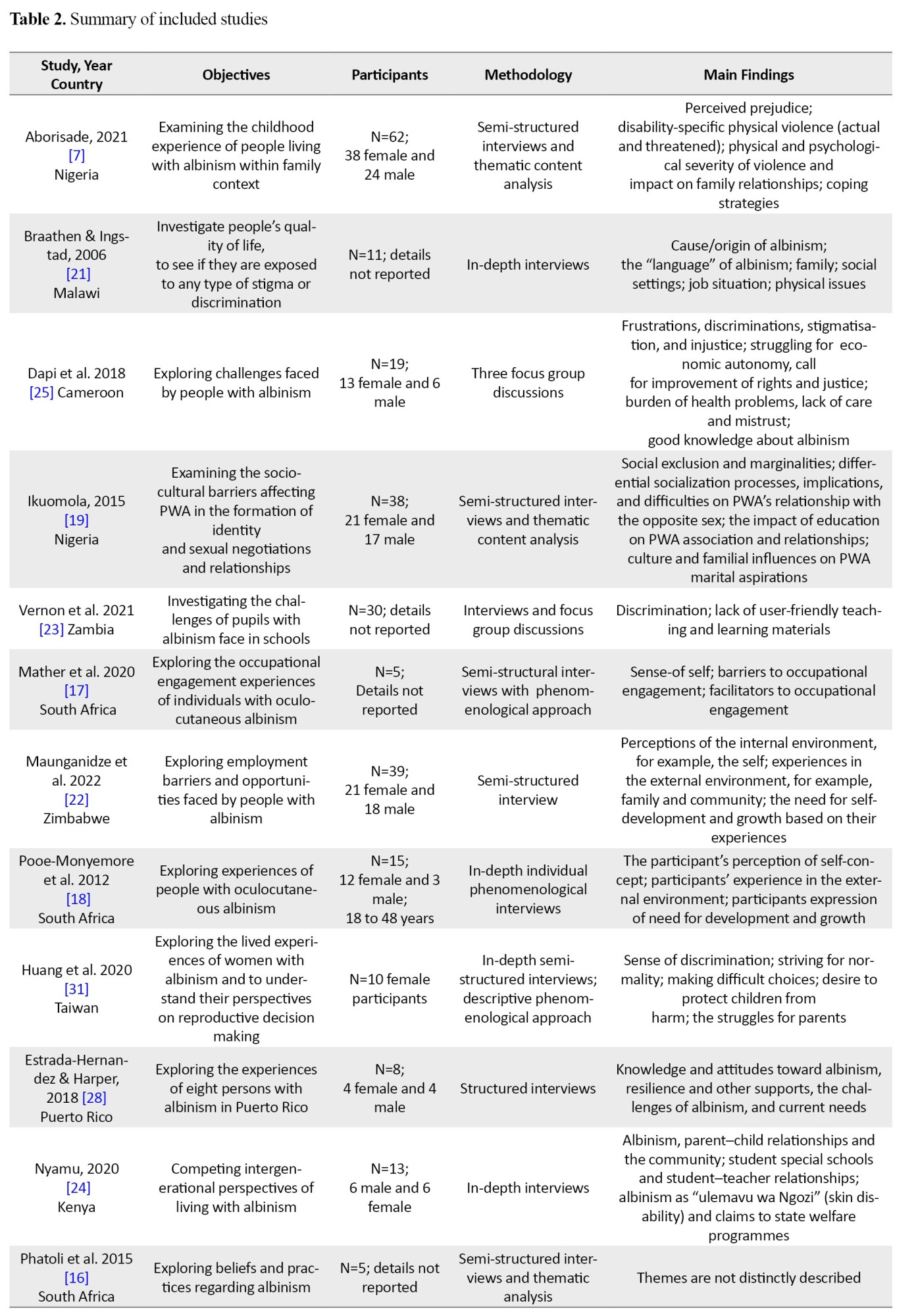

The reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts. Evaluation of full-text studies was done independently by two reviewers. The reasons for exclusion were recorded and any disagreements between the first and second reviewers were resolved with the third reviewer. All phenomenology and grounded theory studies qualitative content analysis, case studies, and other types of qualitative studies that were extracted through interviews and focus groups, in addition to observation of the experiences and perceptions of PWA were included. Non-English and non-Persian articles were excluded to avoid the influence of the translator’s bias, only original articles were included in the research, and other articles, such as reviews, letters to the editor, and commentaries were excluded. The information is presented in Table 2 which includes data on the country under study, the date of the study, the study plan, the purpose of the study, the study method, and the findings.

Quality assessment

The critical appraisal skills program (CASP) was used to evaluate the methodological quality of qualitative studies (Table 3).

The items were scored with “yes/no” according to the adequate description of the research parts, and the unclear option to indicate the unidentifiable status. Studies were independently evaluated by two authors (Taher Alizadeh and Bahman Bahmani) and disagreements in scoring and evaluation were resolved through discussion.

Extraction and synthesis

All articles were read several times during the analysis. The characteristics of the research, including the objectives and design of the research, the number of samples, and the main data were extracted and tabulated. Then, all the quotes of the participants in the results, findings, conclusion, and discussion section of the articles were extracted word by word for coding and entered into the MAXQDA ANALTIC PRO software, version 2020.1. If a group of people without albinism participated in the study, only the findings related to them were analyzed. The analysis and synthesis of data included three steps. First, the meaningful parts of the text were extracted and after the study, they were labeled as open codes. In the second step, these codes were created according to the related fields, and descriptive themes that had the closest meaning to the same open codes. In the third stage, these descriptive themes were more abstract, and analytical themes were created.

Results

Characteristics of the studies

A total of 16 studies from 12 different countries from 2006 to 2022 (Table 2) passed the criteria to enter the review. Ten studies were conducted in the African continent and in the countries of South Africa [16-18], Nigeria [7, 19], Malawi [20, 21], Zimbabwe [22], Zambia [23], Kenya [24], Cameroon [25], and the rest were in other countries, such as Iran [10], Canada [26], England [27], Puerto Rico [28]. The number of participants was 326 with the age range of 18 to 60 years. In-depth semi-structured interviews and focus groups were used to collect data.

Search results

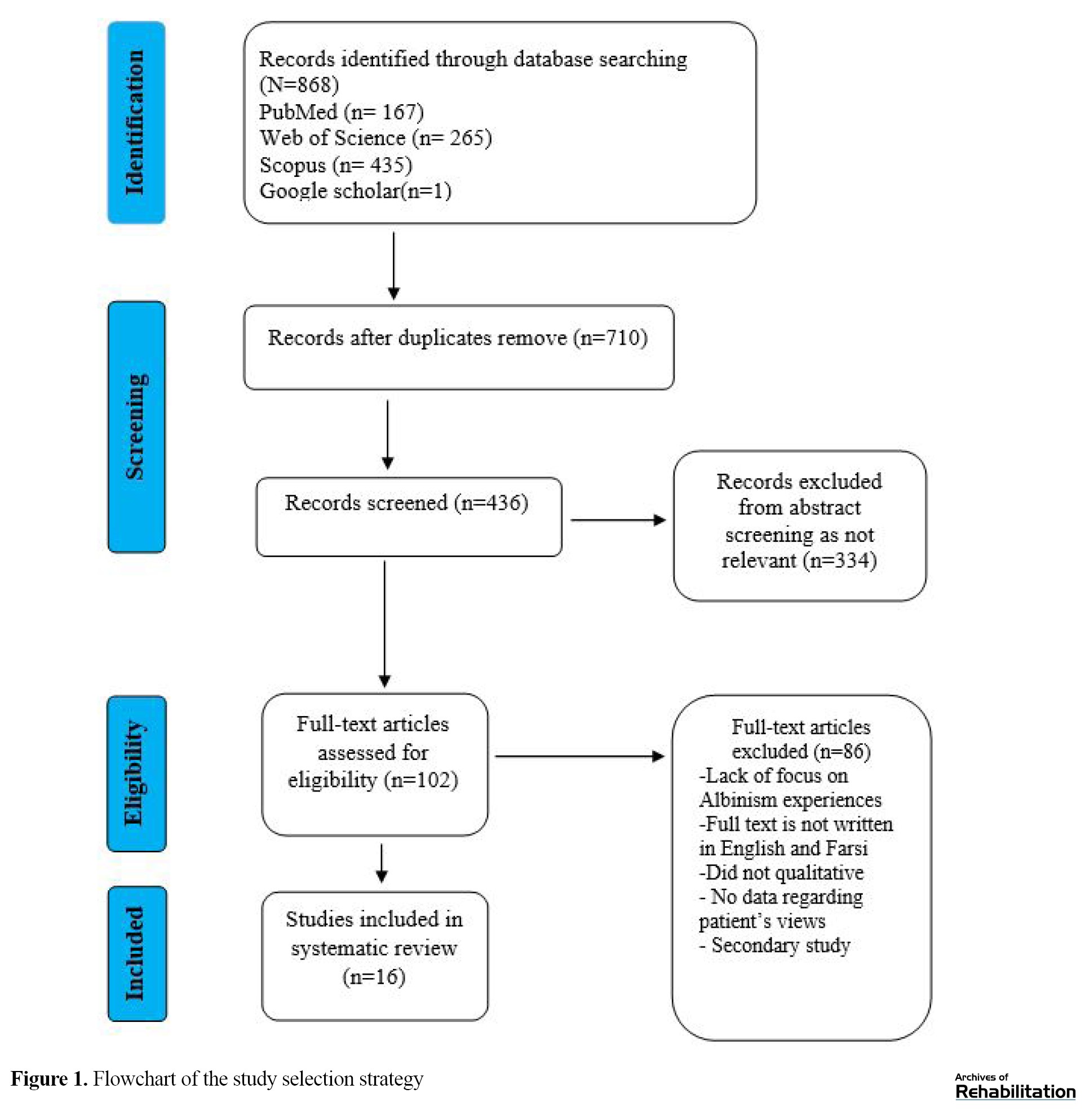

According to the search strategy (Table 1), 868 studies were obtained in 3 databases (PubMed: n=167; Scopus: n=435; Web of Science: n=265). Meanwhile, one article was selected from the Google Scholar search engine. After removing duplicate and irrelevant items, 436 articles were identified. In the screening phase, the titles and abstracts of the identified studies were examined, which led to the exclusion of 334 studies, as they were considered unsuitable for the present review. Finally, 16 studies related to the review were included in the review. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses diagram (Figure 1) provide more detailed information about the study selection process.

Qualitative results

The main themes identified are summarized in two areas: Psychosocial challenges of PWA and support resources and coping strategies in PWA.

The psychosocial challenges of PWA included 6 sub-themes of stigma/myth, severe violence, challenges related to emotional relationships/marriage/childbearing, job issues, academic challenges, rejection and struggle to be normal, and psychological challenges, which will be explained below.

Stigma, myths, and extreme violence

The majority of participants reported many experiences of receiving prejudice and dealing with myths related to albinism in social interactions [7, 20, 25, 29]. These stereotypical beliefs and widespread negative prejudices in society, in some cases, led to the experience of stigma in these people. PWA were also subject to being addressed with derogatory names and derisive labels in most African countries because PWA skin was lighter and whiter than the rest of society and this difference in appearance exposed them to the center. Being attentive and asking questions and curiosity and wondering and staring and this issue caused them a lot of anxiety. There were many superstitions and legends about the causes of albinism and PWA and these superstitions and misunderstandings intensified the stereotypical view of this population, which exposed them to a lot of abuse and harm. In some cases, because of albinism, PWA was subjected to abuse and beating by their parents and suffered physical injuries. One of the participants of Aborside research maintained the following memory:

“My dad would lock me inside a room and beat me up until I became very weak. Since I was considered stubborn and rude, the entire family believed I possessed more evil spirit than that of my twin brother” [7].

In some African regions, due to witchcraft-related beliefs that PWA body parts bring good luck to people, they were hunted and killed, and the cut parts were used in witchcraft ceremonies. Even though the severity of this problem has decreased, PWA experienced extreme trauma, fear, worry, and avoidance in this case [7, 21, 27, 30].

Challenges related to emotional relationships, marriage, and childbearing

Due to the prevalence of widespread prejudices about PWA and their apparent differences, especially in the African population, these people experienced many cases of reluctance to communicate with others [19], even sometimes people refused to approach and make normal contact, such as greetings. They were avoided in social communication [20]. PWA believed that these communication limitations associated with albinism caused many problems and failures for them in starting an emotional relationship and marriage [19], many of them experienced the feeling of need and lack of emotional relationships and finding a friend. They described heterosexuality as a difficult experience [28], and believed that to increase the probability of accepting an emotional relationship and marriage, they should get a job and a higher education. In addition to the issues and challenges related to the emotional relationship, PWA and marriage cases with these people were concerned about the possibility of their future children suffering from albinism [31]. This issue itself affects their chances of getting married. As a result of these challenges, some PWA experienced emotional relationships and delayed marriage, or sometimes they were disappointed in the ideal marriage [19]. As one participant said:

“I got to a stage in my life that with a good education and job, I knew it was the time, despite being in my late 40s. I was getting old and I have no female friends outside my siblings, due to several rejections in the past” [19].

Career issues

Most PWA experienced limitations in the possibility of employment in some jobs due to their weakness and vision problems. Vision problems can interfere with the completion of tasks according to the employer’s expectations and cause the employer’s dissatisfaction and dismissal from their jobs [21]. In addition, because of the sensitivity and vulnerability of the skin to the sun, PWA experienced limitations in working in open environments [29]. On the other hand, the existence of prejudices, discrimination, and stigma related to albinism in society reduced their chances to get desirable jobs and sometimes made them disappointed about the possibility of employment in the desired jobs [7]. One of the participants said:

“I am sorry to tell you this, I have seen it all. I have been sidelined, I have been stigmatized, I have been left alone when I desperately needed company. These experiences have taught me one thing, never to look for formal employment. I have lost trust in these formal organizations. I no longer have an interest in joining them. I just have to do my things” [22].

These conditions described in some cases prevented the financial independence of PWA. It kept those who did not have the necessary support resources in a state of dependence and created serious problems in meeting their essential needs [20].

Academic issues

All participants experienced many problems and challenges related to the visual limitations caused by albinism, visual impairment, and nystagmus, making it difficult for them to see the blackboard in the classroom and the process of reading books, especially subjects such as mathematics that require more visual attention [10]. They generally had to sit in the front rows of the class to have more understanding of the teaching [27]. PWA, compared to students without albinism, due to the problems caused by albinism, spend relatively more time and effort on learning. These limitations were not understood by the teachers [23] and even sometimes the attempts and mistakes in the lesson that were directly or indirectly caused by the conditions of albinism became the subject of abuse and ridicule by teachers and students [26]. On the other hand, due to visual limitations and the impossibility of accompanying most of the teachers, some PWA experienced a lot of dependence on some of their classmates to learn and do homework in class. This issue caused concerns and problems about being a burden and caused avoidance by other students for some participants [28]. One participant said:

«When I was at school, I always needed to have somebody to dictate to me what the teacher wrote on the blackboard and often wondered if the person helping me perceived me as a burden and avoided me in more social-related situations” [28].

Rejection and struggle to be normal

PWA reported many hard experiences centered on rejection in the family environment and other social environments, such as educational and work situations, they were sometimes not allowed into friendly and school groups [23], and people who did not have albinism avoided them [19], fearing that the presence of a person with albinism will cause the bride’s possible child to suffer from albinism. Some people prevented them from attending weddings [7]. They were mostly not invited to parties [19]. Since PWA considered these social exclusions as a result of having albinism and their different appearance, these experiences created heavy pressure and discomfort for them and exposed them to social isolation. One of the participants said:

“They may choose not to go ahead with the wedding, as they may fear my sister could also produce an albino for their son (the groom)” [7].

Because of the difficulty that this situation created for them, some PWA tried to look “normal” by not attracting attention and putting more effort into doing their homework [16, 27] and not to provoke people’s attention and judgment. However, this effort to appear normal also became a source of additional pressure for them.

Psychological challenges

External pressures and challenges related to albinism negatively affect the mental health of people with albinism. These events sometimes caused serious problems for them. Some of them reported problems related to sleep [7], they sometimes experienced isolation and loneliness, feelings of unlovability and shame [7], and they sometimes even engaged in self-destructive and self-attacking patterns [26, 27]. Subsequently, they reported damage to their self-esteem [16]. These damages expose some of PWA to the use of illegal drugs and alcohol [7] and even in more severe cases, the person has suicidal ideation [20]. Some people also felt anxious and avoided talking and facing the issue of albinism [19]. These psychological challenges, as one of them said, were the source of many annoyances for PWA:

“I have bitterness in my heart and I cannot pretend that all is well with me, despite the love my parents show me. At times, I feel like I should just end my life” [20].

Support resources and coping strategies

In none of the reviewed studies, the role of governmental and non-governmental organizations in supporting PWA has been prominent. They used some support resources and coping strategies to reduce the negative effects of challenges and tensions related to albinism. The sub-theme of family and supporting teachers, auxiliary tools and equipment, and coping strategies are explained below.

Supportive family and teachers

The family, especially the parents, had the most important supporting role for the participants. They played an essential role with their care support and empathy in the acceptance and adaptation of PWA [17]. The love and support of parents and nurses made it easier for them to bear the challenges [31]. In addition to giving them the feeling of love and support, the family also prepared them for the tough conditions outside [26], for example, one of the participants said:

“My mother always told me, ‘When you are inside this home, everyone here loves you, but when you step over the threshold, there is a world out there that does not and may not.’ And she was right and I understood that. That was the way I was raised, to enjoy the opportunities that my family presented to me and, of course, understand later that the world was very cold” [31].

Considering that the participants spent a lot of their time in academic environments and these environments were the source of many challenges and problems for PWA, the role of teachers in reducing tensions and their adaptation was highlighted and some participants had positive experiences of supportive teachers reported in the school environment [17, 24]. Teachers even helped them with skincare and practical recommendations to prevent sunburn in addition to psychological support for PWA [24].

Tools and auxiliary equipment assistive

Tools and equipment played an important role in reducing the limitations related to vision and skin in PWA, although due to the high cost of the equipment, not all of them could use assistive equipment [10]; however, most of them used sunscreen lotions and They used the appropriate cover to take care of the skin against the scorching sun and reduce the possibility of skin cancer [21]. To compensate for poor eyesight and improve academic performance, the participants use glasses, laptops, and magnifying glasses [20, 23]. Because of various problems, such as the difficulty of carrying the tool or being bothered by attracting attention and being judged by others, using this tool was uncomfortable for some of them. A proportion of the participants sometimes preferred to wear it regularly, while some of them did not use that equipment even at the cost of enduring vision problems [27]. One of the participants said:

“Well, I used to have … when I was … kind of, kind of, like, three years ago, I had, like, a laptop and a stand with a camera on, so I could see the board, but I did not use it because it was just too big and too heavy and too complicated to set up, it just, kind of, annoyed me and I didn’t really like it so, I just kind of ditched” [27].

Coping strategies

This subcategory describes the strategies of PWA to reduce the pressure of negative emotions. All participants used coping strategies to face challenges and reduce the negative effect of pressure, which is explained in the two sub-themes of emotion-oriented and problem-oriented coping strategies.

Emotion-oriented coping strategy

In the emotion-oriented coping strategy, the person responds emotionally to stress and challenges, although the healthy experience of emotions can prevent the formation of mental disorders. If the intensity of these emotions and anxieties is beyond the tolerance of the individual, it may aggravate the injury and make wrong decisions. For example, some PWA used religious and spiritual beliefs in facing difficult conditions and challenges related to albinism. Believing that they were created by God in this way and that they are no different from other people helped them to face the myths and superstitions common in society and made them feel comfortable [21, 23]. Even some of them believed that God takes revenge on those whom he annoys [29]. Some of them were thankful to God for their situation [30, 31]. Some of them used to avoid confrontation by talking about annoying issues [32] and experienced anger and guilt, pessimism and self-attack [7]. For example, one of the participants said:

“Albinism has made me try to avoid and keep myself away from situations that are very anxiety-provoking and stressful due to my visual impairment” [10].

Problem-oriented coping strategy

The problem-solving-oriented strategy refers to the direct effort to eliminate the stressful factor and includes practical solutions to eliminate the stressful factor. Some participants use problem-oriented and efficient strategies, such as humor, assertive behavior [26, 29], trying to accept themselves and illness [10], positivity [26], exercise, forgiveness, and action to find friends [7], exercise and hard work [28], were used which played an important role in helping participants manage problems and stress related to albinism. One of the participants said:

“I also use my sense of humor and often joke about myself in a not too derogatory way” [26].

Discussion

This thematic synthesis of qualitative data has provided an in-depth understanding of the psychosocial experiences of PWA. Through the synthesis of existing qualitative literature, two main themes were identified that represent the challenges and supportive resources of PWA. This review shows what psychosocial challenges PWA experience what support resources they use to face these challenges and how their experiences of living with albinism have been.

Psycho-social challenges related to albinism

The challenges that originated because PWA is different from others, including stigma, discrimination, prejudice, superstitions, and myths related to PWA were the key concepts in the literature review. Following these beliefs and negative views on PWA, they were exposed to severe abuses and violence, such as murder, which caused serious psycho-social consequences for them. These frequent small and large challenges made them vulnerable to other challenges. The problems that other people without albinism might have faced more easily made them vulnerable. This finding is in line with the results of previous studies [26, 29, 32, 33]. Some of the participants of a study who suffered from skin diseases, such as eczema and psoriasis also had serious challenges in their emotional relationships [34]. Pinquart and Pfeiffer’s observations in 2011 showed that people with visual impairments were less active in forming emotional relationships [35]. Since not having healthy and natural skin plays an important role in provoking the traumatic reactions of others, the interaction of these attitudes and traumatic actions of others with the emotional and avoidant reactions of PWA and many difficulties in finding a suitable job can form a vicious circle that to keep PWA away from the society and deprive them of the possibility of creating emotional relationships and expose them to more psychological harm.

One of the basic challenges of PWA was having limitations in finding a suitable job, they were limited in choosing some jobs due to having vision defects; meanwhile, PWA skin sensitivity prevented them from working in open places where they were exposed to strong sunlight. In some countries, such as Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and South Africa [22, 23, 36, 37], employment opportunities have been designed and implemented according to the conditions of these people, and some non-governmental organizations provide job rehabilitation. They practiced jobs, such as teaching, secretarial work, music work, and working in the field that did not require being in the open air and direct exposure to the sun, as well as high visual acuity. Apart from the limitations that were directly related to albinism, the differences and prejudices of the society toward them were another factor that created challenges and problems related to the jobs of these people. These issues were in line with the results of previous research [17, 22]. In addition to the mentioned factors, the numerous damages that have been inflicted on the self-esteem of PWA since childhood and because they were more likely to be driven to avoid patterns to reduce anxiety and environmental pressures, the possibility of self-presentation and abilities are limited. Subsequently, their chances of getting a suitable job and profession will decrease.

The research of Vernon et al. in 2021 showed the problems and challenges related to education that PWA experienced are because of issues caused by different vision and appearance [23]; namely, albinism-related visual effects, such as visual weakness and nystagmus and strabismus. It played a major role in their problems and exposed them to academic failure and teacher misbehavior. The interaction of vision problems and the misbehavior of teachers and peers sometimes made it difficult to tolerate educational environments. The studies of Tambala-Kaliati et al. in 2021 and Vernon et al. in 2021 confirmed these findings [20, 23]. The importance and necessity of having emotional relationships in the mental health of people is well known [38], failures and delays in starting emotional relationships and receiving the feeling of reluctance of others to marry with PWA were among the communication challenges of this population [19]. In a 2017 study, Gao et al. showed these challenges of emotional connection and marriage in people with chronic skin diseases [39]. In the present review, PWA pointed to multiple experiences of rejection and the struggle to appear normal as one of the most important challenges associated with albinism. Similar to this finding, Huang et al. in a 2020 study showed that PWA, because of the negative feeling of being different, struggled a lot to look normal [31]. This review highlights the impact that having albinism has on a person’s mental health. Estrada in 2007 showed in a study the psychological and emotional challenges experienced by PWA reported psychological issues, such as lack of self-esteem, depression, anger, and guilt experienced by PWA concerning albinism [40], which was in line with the findings of this review.

Support resources and coping strategies

To reduce the pressure of tensions and cope with the situation, PWA used support resources and emotional and problem-oriented coping strategies, when their family, teachers, and friends had good awareness and mental health. Similar to the findings of previous research [17, 26, 28], they played an outstanding supporting role for PWA, but the misbehavior of these groups (family, friends, and teachers) in other populations of PWA was one of the difficult challenges that they had to face. Accordingly, the existence and spread of superstitious beliefs and legends related to albinism and the lack of scientific knowledge about these people can be a variable that turns these supportive factors into harmful factors.

Stevelink et al. in 2015 showed the positive role of using aids related to low vision in low-vision people [41], in this review, PWA used tools, such as glasses, cameras, and laptops to a large extent They compensated for vision limitations, especially in educational situations, they also used lotions and covers that took care of their skin against intense sun and skin cancer, the findings of this section were consistent with previous studies [17, 29]. The experience of useful use of tools and equipment can help PWA in dealing with the feeling of hopelessness and helplessness caused by the challenges of albinism and facilitate their presence in the fields of work and education. Also, in 2016, Thurston showed in research [27] that it was not possible to use the tool all the time and for all people, the continuous and high use of cameras and mobile phones sometimes attracts the attention of others and worries about being judged by others. Meanwhile, problems such as the difficulty of always carrying tools aggravated these problems. Hence, probably the type of attitude and the level of preparation and correct knowledge of PWA and people about albinism can be a factor that overshadows the positive effect of using the tool.

In line with previous studies [26, 28, 42], this review also showed the coping strategies used by PWA in response to related limitations and challenges. PWA seems to be appropriate to the personality structure and the level of acceptance of albinism, they used emotion-oriented or problem-oriented coping strategies; that is, a higher level of acceptance and healthier personality structure (being equipped with traits, such as resilience, positivity, psychological mindedness) indicates more problem solving-oriented coping strategies such as evaluation. They used choices, reading, sports, games, drawing, and counseling [10] and experienced more adaptation. Although probably the intensity and prevalence of external challenges such as myths, discrimination, and stigma in the living environment of PWA can prevent these people from using their inner psychological capacities and cause them to use some kind of regressive defense mechanisms and emotion-oriented coping strategies and suffer uncomfortable conditions.

Conclusion

This review investigated the psycho-social experiences of PWA. This review concludes that the experiences of PWA are strongly influenced by cultural, religious, family, and social contexts. Many of PWA’s experiences were negative and disturbing and included difficult challenges. They used support resources and coping strategies to moderate these difficulties and negative experiences. In many African countries where the prevalence of albinism is higher, probably the low level of development and poverty and the low general well-being of the society and the higher prevalence of superstitions act as a serious obstacle in improving the conditions of this population, even though these conditions in Iran are worse than in other countries. The aforementioned is not African, but Iranian PWA also experiences many psychosocial challenges [5]. Addressing the challenges of this population is still one of the serious concerns of government systems, and the lack of systematic support to diminish these challenges is noticeable. Supporting the PWA and facilitating the access of these people to support and health facilities and equipment are essential points that government organizations and related non-governmental organizations should consider. Through identifying and extracting injuries, needs, and psychological coordinates, strengthening albinism associations, and psycho-social empowerment through holding workshops and rounds, these organizations can facilitate this group in finding suitable jobs and entering into healthy relationships. These actions and gaining insight from the psychosocial experiences of PWA will provide valuable understanding of how to manage and deal with the consequences of this disorder to people who deal with this population; therefore, conducting more studies to understand the psychosocial experiences of people Having albinism seems essential.

In addition, considering that most of the qualitative research has been done in African countries, the main focus of research related to albinism is different in Africa and other regions. For example, in Africa, the focus is mainly on violence and superstitions related to albinism. Considering the whiteness of the skin and hair in the generally black population creates a clear difference in appearance and puts them in the center of negative attention, but in non-black countries, such as Iran, due to the lack of a strong difference in appearance between sufferers and non-sufferers, this difference in appearance and attention is less, and in addition, superstitious and magical beliefs about albinism in non-African countries are not reported as strongly as in African regions, it can be assumed that the consequences and experiences of albinism in black and non-black people can be somewhat different. Therefore, for a more comprehensive understanding of the experiences of this population, we need to study and pay attention to the challenges and issues of PWA in non-African countries. It is also suggested that the results of this review be used to develop training packages for therapists and rehabilitators in the physical and psycho-social fields, and according to the needs and experiences of this population, the development of auxiliary tools and equipment and more activity of governmental and non-governmental organizations in support and assistance Support people with albinism.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This review has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.017), and was registered in the PROSPERO, International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (Code: CRD42023393183).

Funding

The present article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Taher Alizadeh, approved by Department of Counselling, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Project management: Taher Alizadeh and Bahman Bahmani; Writing the original draft: Taher Alizadeh; Conceptualization, review and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the officials of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences for approving and supporting this study.

References

Albinism is derived from the Latin word “albus”, meaning white. This word shows an outward description of the condition of the sufferers. Oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) is a rare autosomal recessive, inherited, non-transmissible disorder that is associated with a significant reduction or absence of pigmentation in the skin, hair, and eyes. This disorder is incurable and can be found in any population worldwide, regardless of gender and ethnicity [1]. Melanin is a pigment that protects the skin from ultraviolet rays and helps produce color [1]. Since people with albinism (PWA) have a complete lack or reduction in melanin biosynthesis, which causes white and pale skin and hair that become sensitive to sunburn, the lack of melanin, which is a skincare factor, increases the risk of skin cancer in these people. If proper care measures are not taken, only a few of these people will survive to the age of 40 years [2]. A rarer form of albinism, known as ocular albinism, affects only the eyes of the affected person. Albinism causes problems and defects related to vision, such as reduced visual acuity, involuntary eye movements, deviation, and sensitivity to light [3]. This genetic disease begins at birth and continues until the end of life, and in case both parents are affected or carry the albinism gene, they are likely to pass it on to their children [4]. In Iran, there are no official statistics about the number of PWA; however, according to estimates, it can reach 35000 people [5]. In most regions of the world, the prevalence of albinism is approximately 1 in every 20000 people; nevertheless, in some areas, such as East African countries, this number is 1 in every 1000. This trend is also increasing [6]. These people are exposed to many challenges, discrimination, and abuses since childhood. In social environments, they suffer all kinds of academic challenges, ridicule, rejection, stigma, and physical and sexual violence [7]. In addition, PWA faces many challenges in communicating with others due to their different appearance and limitations caused by albinism. The conditions of PWA in some parts of Africa have been complicated, and these people have been threatened, persecuted, and even killed and mutilated due to superstitions and myths related to albinism, which cause constant worries and isolation. Meanwhile, these people have withdrawn from social situations [8, 9]. Numerous qualitative studies have been conducted on the experiences of PWA in African countries. However, in other regions of the world, such as Iran, studies that investigate the psychosocial experiences of PWA are limited. In Iran, the psychological experiences of this population have been investigated in studies by Alizadeh et al. [5] and Zamani et al. [10].

Compared to other diseases that do not have a negative impact on the baby’s appearance from the beginning (such as hemophilia), in albinism, the possibility of establishing a sufficient connection and healthy support, mother-infant, is reduced and can increase the possibility of attachment problems in these people. Therefore, the insecure attachment style increases the probability of many problems and mental disorders, such as depression [11], social anxiety [12], substance dependence disorders [13]; therefore, probably most people with albinism, due to problems and disorders related to the skin, hair, and eyes, have been exposed to wide psychological consequences, such as depression, anxiety, suicide, body deformity, obsession, and so on. Meanwhile, since the main focus of qualitative research in African countries is on the concepts of stigma and discrimination and issues related to killing, the psychological and coping issues of these people against tensions have not been considered sufficiently. Given the limitations of this type of study in Iran, presenting a comprehensive picture of the psycho-social experiences of PWA in the field of health, rehabilitation, and psychologists can help in planning and designing educational and treatment packages for a better understanding of albinism and the problems of this population. Also, because of the limitations that are directly and indirectly caused by albinism, PWA experience difficult conditions concerning family, teachers, peers, and friends; hence, providing a direct understanding of their experiences and conditions can help other non-specialist populations, such as families, teachers, and other people who are involved with the problem of albinism to help them experience healthier and harm-free relationships. Accordingly, this study identifies and combines the available evidence from the existing literature to provide a better understanding of the psycho-social experiences of PWA.

Materials and Methods

Analysis method

This is a thematic synthesis type review study which is one of the available methods for synthesis qualitative research [14]. Data extraction, analysis, and synthesis of this review follow the approach of thematic synthesis of Thomas and Harden [15], which transforms the concept of thematic analysis of primary data into secondary data. First, the primary studies were coded line by line. Descriptive themes were created from the themes that appeared initially, and finally, by going beyond the descriptive themes, analytical themes were generated. This approach moves beyond the findings of the main research to build a new and comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of albinism.

Search strategy

Relevant studies until January 2023 were identified using a structured search strategy in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Magiran databases. No time limit was applied in searching the databases. A manual search was also done in the index of some African journals (due to the higher prevalence of albinism in Africa), such as Society and Disability, African Journal of Disability, African Identities, and Journal of African Cultural Studies. Meanwhile, the Google Scholar search engine and the list of related study sources were searched for potential studies. No related Persian articles were found in the search and all the found articles were in English. The search strategy is presented in Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Qualitative studies that described the psychosocial experiences and perceptions of PWA were included, and studies that examined the perceptions and experiences of caregivers and those around them or used quantitative methods were excluded from the research.

Data selection and extraction

The reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts. Evaluation of full-text studies was done independently by two reviewers. The reasons for exclusion were recorded and any disagreements between the first and second reviewers were resolved with the third reviewer. All phenomenology and grounded theory studies qualitative content analysis, case studies, and other types of qualitative studies that were extracted through interviews and focus groups, in addition to observation of the experiences and perceptions of PWA were included. Non-English and non-Persian articles were excluded to avoid the influence of the translator’s bias, only original articles were included in the research, and other articles, such as reviews, letters to the editor, and commentaries were excluded. The information is presented in Table 2 which includes data on the country under study, the date of the study, the study plan, the purpose of the study, the study method, and the findings.

Quality assessment

The critical appraisal skills program (CASP) was used to evaluate the methodological quality of qualitative studies (Table 3).

The items were scored with “yes/no” according to the adequate description of the research parts, and the unclear option to indicate the unidentifiable status. Studies were independently evaluated by two authors (Taher Alizadeh and Bahman Bahmani) and disagreements in scoring and evaluation were resolved through discussion.

Extraction and synthesis

All articles were read several times during the analysis. The characteristics of the research, including the objectives and design of the research, the number of samples, and the main data were extracted and tabulated. Then, all the quotes of the participants in the results, findings, conclusion, and discussion section of the articles were extracted word by word for coding and entered into the MAXQDA ANALTIC PRO software, version 2020.1. If a group of people without albinism participated in the study, only the findings related to them were analyzed. The analysis and synthesis of data included three steps. First, the meaningful parts of the text were extracted and after the study, they were labeled as open codes. In the second step, these codes were created according to the related fields, and descriptive themes that had the closest meaning to the same open codes. In the third stage, these descriptive themes were more abstract, and analytical themes were created.

Results

Characteristics of the studies

A total of 16 studies from 12 different countries from 2006 to 2022 (Table 2) passed the criteria to enter the review. Ten studies were conducted in the African continent and in the countries of South Africa [16-18], Nigeria [7, 19], Malawi [20, 21], Zimbabwe [22], Zambia [23], Kenya [24], Cameroon [25], and the rest were in other countries, such as Iran [10], Canada [26], England [27], Puerto Rico [28]. The number of participants was 326 with the age range of 18 to 60 years. In-depth semi-structured interviews and focus groups were used to collect data.

Search results

According to the search strategy (Table 1), 868 studies were obtained in 3 databases (PubMed: n=167; Scopus: n=435; Web of Science: n=265). Meanwhile, one article was selected from the Google Scholar search engine. After removing duplicate and irrelevant items, 436 articles were identified. In the screening phase, the titles and abstracts of the identified studies were examined, which led to the exclusion of 334 studies, as they were considered unsuitable for the present review. Finally, 16 studies related to the review were included in the review. The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses diagram (Figure 1) provide more detailed information about the study selection process.

Qualitative results

The main themes identified are summarized in two areas: Psychosocial challenges of PWA and support resources and coping strategies in PWA.

The psychosocial challenges of PWA included 6 sub-themes of stigma/myth, severe violence, challenges related to emotional relationships/marriage/childbearing, job issues, academic challenges, rejection and struggle to be normal, and psychological challenges, which will be explained below.

Stigma, myths, and extreme violence

The majority of participants reported many experiences of receiving prejudice and dealing with myths related to albinism in social interactions [7, 20, 25, 29]. These stereotypical beliefs and widespread negative prejudices in society, in some cases, led to the experience of stigma in these people. PWA were also subject to being addressed with derogatory names and derisive labels in most African countries because PWA skin was lighter and whiter than the rest of society and this difference in appearance exposed them to the center. Being attentive and asking questions and curiosity and wondering and staring and this issue caused them a lot of anxiety. There were many superstitions and legends about the causes of albinism and PWA and these superstitions and misunderstandings intensified the stereotypical view of this population, which exposed them to a lot of abuse and harm. In some cases, because of albinism, PWA was subjected to abuse and beating by their parents and suffered physical injuries. One of the participants of Aborside research maintained the following memory:

“My dad would lock me inside a room and beat me up until I became very weak. Since I was considered stubborn and rude, the entire family believed I possessed more evil spirit than that of my twin brother” [7].

In some African regions, due to witchcraft-related beliefs that PWA body parts bring good luck to people, they were hunted and killed, and the cut parts were used in witchcraft ceremonies. Even though the severity of this problem has decreased, PWA experienced extreme trauma, fear, worry, and avoidance in this case [7, 21, 27, 30].

Challenges related to emotional relationships, marriage, and childbearing

Due to the prevalence of widespread prejudices about PWA and their apparent differences, especially in the African population, these people experienced many cases of reluctance to communicate with others [19], even sometimes people refused to approach and make normal contact, such as greetings. They were avoided in social communication [20]. PWA believed that these communication limitations associated with albinism caused many problems and failures for them in starting an emotional relationship and marriage [19], many of them experienced the feeling of need and lack of emotional relationships and finding a friend. They described heterosexuality as a difficult experience [28], and believed that to increase the probability of accepting an emotional relationship and marriage, they should get a job and a higher education. In addition to the issues and challenges related to the emotional relationship, PWA and marriage cases with these people were concerned about the possibility of their future children suffering from albinism [31]. This issue itself affects their chances of getting married. As a result of these challenges, some PWA experienced emotional relationships and delayed marriage, or sometimes they were disappointed in the ideal marriage [19]. As one participant said:

“I got to a stage in my life that with a good education and job, I knew it was the time, despite being in my late 40s. I was getting old and I have no female friends outside my siblings, due to several rejections in the past” [19].

Career issues

Most PWA experienced limitations in the possibility of employment in some jobs due to their weakness and vision problems. Vision problems can interfere with the completion of tasks according to the employer’s expectations and cause the employer’s dissatisfaction and dismissal from their jobs [21]. In addition, because of the sensitivity and vulnerability of the skin to the sun, PWA experienced limitations in working in open environments [29]. On the other hand, the existence of prejudices, discrimination, and stigma related to albinism in society reduced their chances to get desirable jobs and sometimes made them disappointed about the possibility of employment in the desired jobs [7]. One of the participants said:

“I am sorry to tell you this, I have seen it all. I have been sidelined, I have been stigmatized, I have been left alone when I desperately needed company. These experiences have taught me one thing, never to look for formal employment. I have lost trust in these formal organizations. I no longer have an interest in joining them. I just have to do my things” [22].

These conditions described in some cases prevented the financial independence of PWA. It kept those who did not have the necessary support resources in a state of dependence and created serious problems in meeting their essential needs [20].

Academic issues

All participants experienced many problems and challenges related to the visual limitations caused by albinism, visual impairment, and nystagmus, making it difficult for them to see the blackboard in the classroom and the process of reading books, especially subjects such as mathematics that require more visual attention [10]. They generally had to sit in the front rows of the class to have more understanding of the teaching [27]. PWA, compared to students without albinism, due to the problems caused by albinism, spend relatively more time and effort on learning. These limitations were not understood by the teachers [23] and even sometimes the attempts and mistakes in the lesson that were directly or indirectly caused by the conditions of albinism became the subject of abuse and ridicule by teachers and students [26]. On the other hand, due to visual limitations and the impossibility of accompanying most of the teachers, some PWA experienced a lot of dependence on some of their classmates to learn and do homework in class. This issue caused concerns and problems about being a burden and caused avoidance by other students for some participants [28]. One participant said:

«When I was at school, I always needed to have somebody to dictate to me what the teacher wrote on the blackboard and often wondered if the person helping me perceived me as a burden and avoided me in more social-related situations” [28].

Rejection and struggle to be normal

PWA reported many hard experiences centered on rejection in the family environment and other social environments, such as educational and work situations, they were sometimes not allowed into friendly and school groups [23], and people who did not have albinism avoided them [19], fearing that the presence of a person with albinism will cause the bride’s possible child to suffer from albinism. Some people prevented them from attending weddings [7]. They were mostly not invited to parties [19]. Since PWA considered these social exclusions as a result of having albinism and their different appearance, these experiences created heavy pressure and discomfort for them and exposed them to social isolation. One of the participants said:

“They may choose not to go ahead with the wedding, as they may fear my sister could also produce an albino for their son (the groom)” [7].

Because of the difficulty that this situation created for them, some PWA tried to look “normal” by not attracting attention and putting more effort into doing their homework [16, 27] and not to provoke people’s attention and judgment. However, this effort to appear normal also became a source of additional pressure for them.

Psychological challenges

External pressures and challenges related to albinism negatively affect the mental health of people with albinism. These events sometimes caused serious problems for them. Some of them reported problems related to sleep [7], they sometimes experienced isolation and loneliness, feelings of unlovability and shame [7], and they sometimes even engaged in self-destructive and self-attacking patterns [26, 27]. Subsequently, they reported damage to their self-esteem [16]. These damages expose some of PWA to the use of illegal drugs and alcohol [7] and even in more severe cases, the person has suicidal ideation [20]. Some people also felt anxious and avoided talking and facing the issue of albinism [19]. These psychological challenges, as one of them said, were the source of many annoyances for PWA:

“I have bitterness in my heart and I cannot pretend that all is well with me, despite the love my parents show me. At times, I feel like I should just end my life” [20].

Support resources and coping strategies

In none of the reviewed studies, the role of governmental and non-governmental organizations in supporting PWA has been prominent. They used some support resources and coping strategies to reduce the negative effects of challenges and tensions related to albinism. The sub-theme of family and supporting teachers, auxiliary tools and equipment, and coping strategies are explained below.

Supportive family and teachers

The family, especially the parents, had the most important supporting role for the participants. They played an essential role with their care support and empathy in the acceptance and adaptation of PWA [17]. The love and support of parents and nurses made it easier for them to bear the challenges [31]. In addition to giving them the feeling of love and support, the family also prepared them for the tough conditions outside [26], for example, one of the participants said:

“My mother always told me, ‘When you are inside this home, everyone here loves you, but when you step over the threshold, there is a world out there that does not and may not.’ And she was right and I understood that. That was the way I was raised, to enjoy the opportunities that my family presented to me and, of course, understand later that the world was very cold” [31].

Considering that the participants spent a lot of their time in academic environments and these environments were the source of many challenges and problems for PWA, the role of teachers in reducing tensions and their adaptation was highlighted and some participants had positive experiences of supportive teachers reported in the school environment [17, 24]. Teachers even helped them with skincare and practical recommendations to prevent sunburn in addition to psychological support for PWA [24].

Tools and auxiliary equipment assistive

Tools and equipment played an important role in reducing the limitations related to vision and skin in PWA, although due to the high cost of the equipment, not all of them could use assistive equipment [10]; however, most of them used sunscreen lotions and They used the appropriate cover to take care of the skin against the scorching sun and reduce the possibility of skin cancer [21]. To compensate for poor eyesight and improve academic performance, the participants use glasses, laptops, and magnifying glasses [20, 23]. Because of various problems, such as the difficulty of carrying the tool or being bothered by attracting attention and being judged by others, using this tool was uncomfortable for some of them. A proportion of the participants sometimes preferred to wear it regularly, while some of them did not use that equipment even at the cost of enduring vision problems [27]. One of the participants said:

“Well, I used to have … when I was … kind of, kind of, like, three years ago, I had, like, a laptop and a stand with a camera on, so I could see the board, but I did not use it because it was just too big and too heavy and too complicated to set up, it just, kind of, annoyed me and I didn’t really like it so, I just kind of ditched” [27].

Coping strategies

This subcategory describes the strategies of PWA to reduce the pressure of negative emotions. All participants used coping strategies to face challenges and reduce the negative effect of pressure, which is explained in the two sub-themes of emotion-oriented and problem-oriented coping strategies.

Emotion-oriented coping strategy

In the emotion-oriented coping strategy, the person responds emotionally to stress and challenges, although the healthy experience of emotions can prevent the formation of mental disorders. If the intensity of these emotions and anxieties is beyond the tolerance of the individual, it may aggravate the injury and make wrong decisions. For example, some PWA used religious and spiritual beliefs in facing difficult conditions and challenges related to albinism. Believing that they were created by God in this way and that they are no different from other people helped them to face the myths and superstitions common in society and made them feel comfortable [21, 23]. Even some of them believed that God takes revenge on those whom he annoys [29]. Some of them were thankful to God for their situation [30, 31]. Some of them used to avoid confrontation by talking about annoying issues [32] and experienced anger and guilt, pessimism and self-attack [7]. For example, one of the participants said:

“Albinism has made me try to avoid and keep myself away from situations that are very anxiety-provoking and stressful due to my visual impairment” [10].

Problem-oriented coping strategy

The problem-solving-oriented strategy refers to the direct effort to eliminate the stressful factor and includes practical solutions to eliminate the stressful factor. Some participants use problem-oriented and efficient strategies, such as humor, assertive behavior [26, 29], trying to accept themselves and illness [10], positivity [26], exercise, forgiveness, and action to find friends [7], exercise and hard work [28], were used which played an important role in helping participants manage problems and stress related to albinism. One of the participants said:

“I also use my sense of humor and often joke about myself in a not too derogatory way” [26].

Discussion

This thematic synthesis of qualitative data has provided an in-depth understanding of the psychosocial experiences of PWA. Through the synthesis of existing qualitative literature, two main themes were identified that represent the challenges and supportive resources of PWA. This review shows what psychosocial challenges PWA experience what support resources they use to face these challenges and how their experiences of living with albinism have been.

Psycho-social challenges related to albinism

The challenges that originated because PWA is different from others, including stigma, discrimination, prejudice, superstitions, and myths related to PWA were the key concepts in the literature review. Following these beliefs and negative views on PWA, they were exposed to severe abuses and violence, such as murder, which caused serious psycho-social consequences for them. These frequent small and large challenges made them vulnerable to other challenges. The problems that other people without albinism might have faced more easily made them vulnerable. This finding is in line with the results of previous studies [26, 29, 32, 33]. Some of the participants of a study who suffered from skin diseases, such as eczema and psoriasis also had serious challenges in their emotional relationships [34]. Pinquart and Pfeiffer’s observations in 2011 showed that people with visual impairments were less active in forming emotional relationships [35]. Since not having healthy and natural skin plays an important role in provoking the traumatic reactions of others, the interaction of these attitudes and traumatic actions of others with the emotional and avoidant reactions of PWA and many difficulties in finding a suitable job can form a vicious circle that to keep PWA away from the society and deprive them of the possibility of creating emotional relationships and expose them to more psychological harm.

One of the basic challenges of PWA was having limitations in finding a suitable job, they were limited in choosing some jobs due to having vision defects; meanwhile, PWA skin sensitivity prevented them from working in open places where they were exposed to strong sunlight. In some countries, such as Zimbabwe, Tanzania, and South Africa [22, 23, 36, 37], employment opportunities have been designed and implemented according to the conditions of these people, and some non-governmental organizations provide job rehabilitation. They practiced jobs, such as teaching, secretarial work, music work, and working in the field that did not require being in the open air and direct exposure to the sun, as well as high visual acuity. Apart from the limitations that were directly related to albinism, the differences and prejudices of the society toward them were another factor that created challenges and problems related to the jobs of these people. These issues were in line with the results of previous research [17, 22]. In addition to the mentioned factors, the numerous damages that have been inflicted on the self-esteem of PWA since childhood and because they were more likely to be driven to avoid patterns to reduce anxiety and environmental pressures, the possibility of self-presentation and abilities are limited. Subsequently, their chances of getting a suitable job and profession will decrease.

The research of Vernon et al. in 2021 showed the problems and challenges related to education that PWA experienced are because of issues caused by different vision and appearance [23]; namely, albinism-related visual effects, such as visual weakness and nystagmus and strabismus. It played a major role in their problems and exposed them to academic failure and teacher misbehavior. The interaction of vision problems and the misbehavior of teachers and peers sometimes made it difficult to tolerate educational environments. The studies of Tambala-Kaliati et al. in 2021 and Vernon et al. in 2021 confirmed these findings [20, 23]. The importance and necessity of having emotional relationships in the mental health of people is well known [38], failures and delays in starting emotional relationships and receiving the feeling of reluctance of others to marry with PWA were among the communication challenges of this population [19]. In a 2017 study, Gao et al. showed these challenges of emotional connection and marriage in people with chronic skin diseases [39]. In the present review, PWA pointed to multiple experiences of rejection and the struggle to appear normal as one of the most important challenges associated with albinism. Similar to this finding, Huang et al. in a 2020 study showed that PWA, because of the negative feeling of being different, struggled a lot to look normal [31]. This review highlights the impact that having albinism has on a person’s mental health. Estrada in 2007 showed in a study the psychological and emotional challenges experienced by PWA reported psychological issues, such as lack of self-esteem, depression, anger, and guilt experienced by PWA concerning albinism [40], which was in line with the findings of this review.

Support resources and coping strategies

To reduce the pressure of tensions and cope with the situation, PWA used support resources and emotional and problem-oriented coping strategies, when their family, teachers, and friends had good awareness and mental health. Similar to the findings of previous research [17, 26, 28], they played an outstanding supporting role for PWA, but the misbehavior of these groups (family, friends, and teachers) in other populations of PWA was one of the difficult challenges that they had to face. Accordingly, the existence and spread of superstitious beliefs and legends related to albinism and the lack of scientific knowledge about these people can be a variable that turns these supportive factors into harmful factors.

Stevelink et al. in 2015 showed the positive role of using aids related to low vision in low-vision people [41], in this review, PWA used tools, such as glasses, cameras, and laptops to a large extent They compensated for vision limitations, especially in educational situations, they also used lotions and covers that took care of their skin against intense sun and skin cancer, the findings of this section were consistent with previous studies [17, 29]. The experience of useful use of tools and equipment can help PWA in dealing with the feeling of hopelessness and helplessness caused by the challenges of albinism and facilitate their presence in the fields of work and education. Also, in 2016, Thurston showed in research [27] that it was not possible to use the tool all the time and for all people, the continuous and high use of cameras and mobile phones sometimes attracts the attention of others and worries about being judged by others. Meanwhile, problems such as the difficulty of always carrying tools aggravated these problems. Hence, probably the type of attitude and the level of preparation and correct knowledge of PWA and people about albinism can be a factor that overshadows the positive effect of using the tool.

In line with previous studies [26, 28, 42], this review also showed the coping strategies used by PWA in response to related limitations and challenges. PWA seems to be appropriate to the personality structure and the level of acceptance of albinism, they used emotion-oriented or problem-oriented coping strategies; that is, a higher level of acceptance and healthier personality structure (being equipped with traits, such as resilience, positivity, psychological mindedness) indicates more problem solving-oriented coping strategies such as evaluation. They used choices, reading, sports, games, drawing, and counseling [10] and experienced more adaptation. Although probably the intensity and prevalence of external challenges such as myths, discrimination, and stigma in the living environment of PWA can prevent these people from using their inner psychological capacities and cause them to use some kind of regressive defense mechanisms and emotion-oriented coping strategies and suffer uncomfortable conditions.

Conclusion

This review investigated the psycho-social experiences of PWA. This review concludes that the experiences of PWA are strongly influenced by cultural, religious, family, and social contexts. Many of PWA’s experiences were negative and disturbing and included difficult challenges. They used support resources and coping strategies to moderate these difficulties and negative experiences. In many African countries where the prevalence of albinism is higher, probably the low level of development and poverty and the low general well-being of the society and the higher prevalence of superstitions act as a serious obstacle in improving the conditions of this population, even though these conditions in Iran are worse than in other countries. The aforementioned is not African, but Iranian PWA also experiences many psychosocial challenges [5]. Addressing the challenges of this population is still one of the serious concerns of government systems, and the lack of systematic support to diminish these challenges is noticeable. Supporting the PWA and facilitating the access of these people to support and health facilities and equipment are essential points that government organizations and related non-governmental organizations should consider. Through identifying and extracting injuries, needs, and psychological coordinates, strengthening albinism associations, and psycho-social empowerment through holding workshops and rounds, these organizations can facilitate this group in finding suitable jobs and entering into healthy relationships. These actions and gaining insight from the psychosocial experiences of PWA will provide valuable understanding of how to manage and deal with the consequences of this disorder to people who deal with this population; therefore, conducting more studies to understand the psychosocial experiences of people Having albinism seems essential.

In addition, considering that most of the qualitative research has been done in African countries, the main focus of research related to albinism is different in Africa and other regions. For example, in Africa, the focus is mainly on violence and superstitions related to albinism. Considering the whiteness of the skin and hair in the generally black population creates a clear difference in appearance and puts them in the center of negative attention, but in non-black countries, such as Iran, due to the lack of a strong difference in appearance between sufferers and non-sufferers, this difference in appearance and attention is less, and in addition, superstitious and magical beliefs about albinism in non-African countries are not reported as strongly as in African regions, it can be assumed that the consequences and experiences of albinism in black and non-black people can be somewhat different. Therefore, for a more comprehensive understanding of the experiences of this population, we need to study and pay attention to the challenges and issues of PWA in non-African countries. It is also suggested that the results of this review be used to develop training packages for therapists and rehabilitators in the physical and psycho-social fields, and according to the needs and experiences of this population, the development of auxiliary tools and equipment and more activity of governmental and non-governmental organizations in support and assistance Support people with albinism.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This review has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.017), and was registered in the PROSPERO, International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (Code: CRD42023393183).

Funding

The present article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Taher Alizadeh, approved by Department of Counselling, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Project management: Taher Alizadeh and Bahman Bahmani; Writing the original draft: Taher Alizadeh; Conceptualization, review and editing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the officials of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences for approving and supporting this study.

References

- Franklin A, Lund P, Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor J. Children with albinism in African regions: Their rights to 'being' and 'doing'. BMC International Health and Human Rights. 2018; 18(1):2. [DOI:10.1186/s12914-018-0144-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mcbride GR. Oculocutaneous albinism: An African perspective. British and Irish Orthoptic Journal. 2014; 11:3-8. [DOI:10.22599/bioj.78]

- Mashige KP, Jhetam S. Ocular findings and vision status of learners with oculocutaneous albinism. African Vision and Eye Health. 2019; 78(1):1-6. [DOI:10.4102/aveh.v78i1.466]

- Lynch P, Lund P, Massah B. Identifying strategies to enhance the educational inclusion of visually impaired children with albinism in Malawi. International Journal of Educational Development. 2014; 39:216-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.07.002]

- Alizadeh T, Bahmani B, Khanjani MS, Azkhosh M, Shakiba S, Vahedi M. Surveying the experiences of people with albinism in Iran: Qualitative research. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2023; 17(1):e132504. [DOI:10.5812/ijpbs-132504]

- Hong ES, Zeeb H, Repacholi MH. Albinism in Africa as a public health issue. BMC Public Health. 2006; 6:212. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-6-212] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Aborisade RA. "Why always me?": Childhood experiences of family violence and prejudicial treatment against people living with albinism in Nigeria. Journal of Family Violence. 2021; 36(8):1081-94. [DOI:10.1007/s10896-021-00264-7] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Burke J, Kaijage TJ, John-Langba J. Media analysis of albino killings in Tanzania: A social work and human rights perspective. Ethics and Social Welfare. 2014; 8(2):117-34. [DOI:10.1080/17496535.2014.895398]

- Machoko CG. Albinism: A life of ambiguity-a Zimbabwean experience. African Identities. 2013; 11(3):318-33. [DOI:10.1080/14725843.2013.838896]

- Zamani Varkaneh M, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee A, Sheikhi MR. Identifying psychosocial challenges and introducing coping strategies for people with albinism. British Journal of Visual Impairment. 2022; 41(4):791-806. [DOI:10.1177/02646196221099155]

- Palitsky D, Mota N, Afifi TO, Downs AC, Sareen J. The association between adult attachment style, mental disorders, and suicidality: Findings from a population-based study. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2013; 201(7):579-86. [DOI:10.1097/NMD.0b013e31829829ab] [PMID]

- Read DL, Clark GI, Rock AJ, Coventry WL. Adult attachment and social anxiety: The mediating role of emotion regulation strategies. Plos One. 2018; 13(12):e0207514. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0207514] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fairbairn CE, Briley DA, Kang D, Fraley RC, Hankin BL, Ariss T. A meta-analysis of longitudinal associations between substance use and interpersonal attachment security. Psychological Bulletin. 2018; 144(5):532-55. [DOI:10.1037/bul0000141] [PMID] [PMCID]