Volume 24, Issue 4 (Winter 2024)

jrehab 2024, 24(4): 472-495 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Fekar Gharamaleki F, Darouie A, Ebadi A, Zarifian T, Ahadi H. Designing and Preliminary Validation of an Azerbaijani-Turkish Grammar Comprehension Test for 4-6 Years Old Children. jrehab 2024; 24 (4) :472-495

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3272-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3272-en.html

1- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,adarouie@hotmail.com

3- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Faculty of Nursing, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Life Style Institute, Faculty of Nursing, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5- Department of Linguistics, Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, Tehran, Iran., Department of Linguistics, Institute for Humanities and cultural studies, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Faculty of Nursing, Life Style Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Life Style Institute, Faculty of Nursing, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

5- Department of Linguistics, Institute for Humanities and Cultural Studies, Tehran, Iran., Department of Linguistics, Institute for Humanities and cultural studies, Tehran, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 2909 kb]

(1105 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (7077 Views)

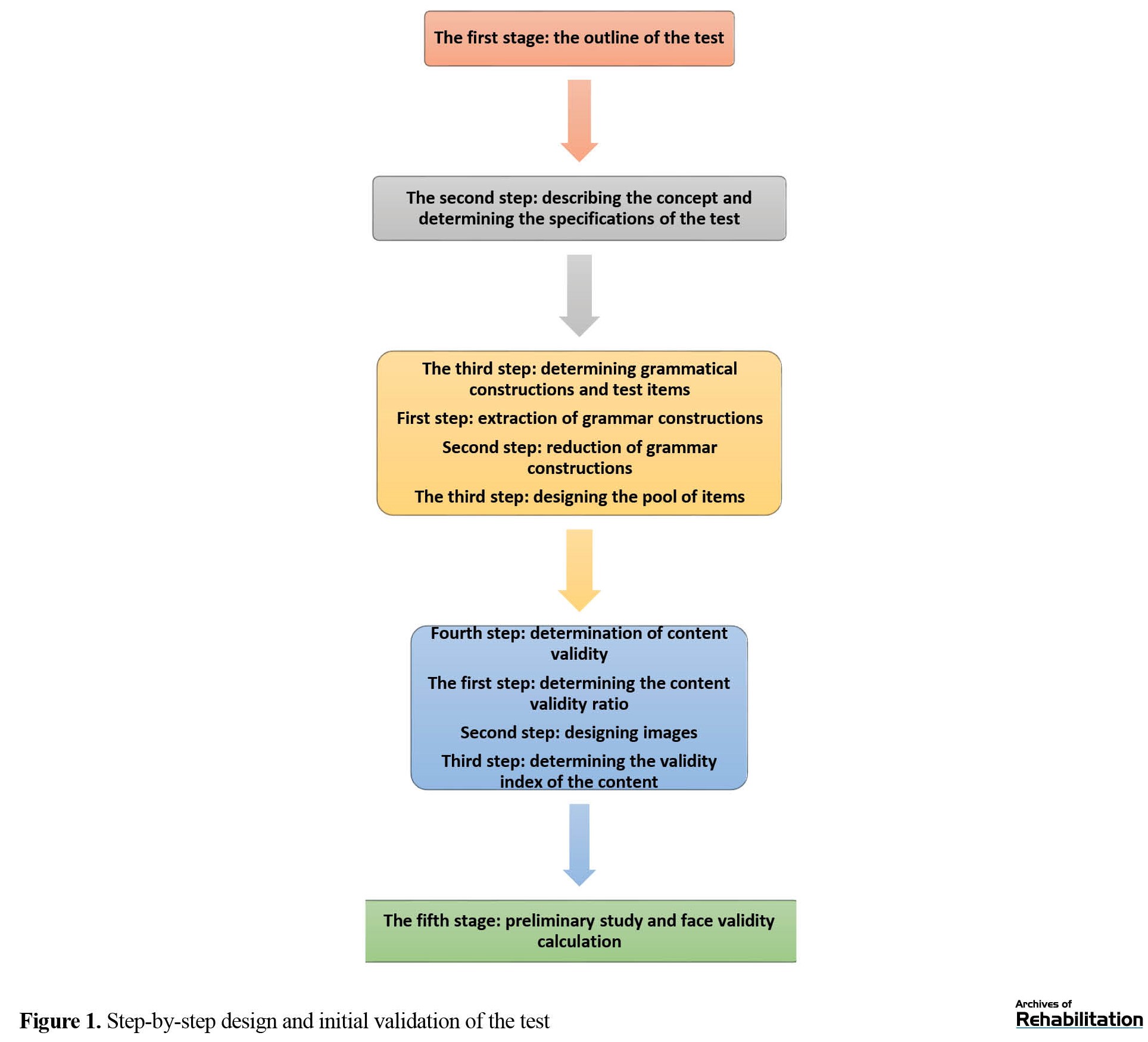

The first stage: Test outline

In the first step, the grammatical constructions of the Azerbaijani-Turkish language were determined, and the necessary steps for content and formal validity were carried out. The ATGCT exam format is paper-based and evaluates grammar using visual stimuli and images.

The second stage: Describing the concept and determining the specifications of the test

First, grammatical constructions in the Azerbaijani-Turkish language test should be determined [26]. To select the structure of the test, four main criteria were considered based on the review of reports of other similar tests and the opinions of the research team [28]. The first criterion was frequency [29]. The second criterion was the imageability test, considered in all stages [30]. The third criterion was the simplicity or complexity of grammatical construction [3]. The fourth criterion was the clinical importance of grammatical construction [31]. Finally, all grammatical constructions with low frequency and high clinical importance were included in the initial version of the test [26].

At this stage, the general characteristics of the test were determined. Finally, 2 items were designed to evaluate each grammar construct. One of the most essential features of ATGCT was that the examiner expressed the target sentence colloquially.

The third stage: Determining grammatical constructions and test items

Three consecutive steps were done: Extracting grammatical constructions, reducing grammatical constructions, and creating a pool of items.

The first step: Extraction of grammar constructions

Six steps were followed to select grammatical constructions:

1. All old and new sources, including Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar books and articles, were reviewed [22-24, 33, 36].

2. Existing empirical evidence on grammar comprehension deficits in DLDs and other language disorders was reviewed [37].

3. Also, a sample of spontaneous speech of 10 Azeri-Turkish-speaking children from Tabriz City, Iran, aged 3-9 years old, was analyzed to extract some constructions from their speech.

4. Studies related to common keywords and syllabic construction in Azeri-Turkish-speaking children aged 18-24 months were used to design test items [39].

5. Informal individual and group interviews with speech therapy and linguistics experts were conducted through a panel of experts and semi-structured interviews. The experts were asked to express their opinions on each grammar construction for 4-6 years old children in the Azeri-Turkish language. Finally, approved grammatical constructions were listed.

6. At this stage, English, Farsi, Azerbaijani-Turkish language tests were examined to identify and adapt suitable constructions. Azerbaijani-Turkish version of the bilingual aphasia test, Azari aphasia screening test, Turkish-Azari aphasia test, Persian and English language development test, grammar comprehension test-version 2, Farsi syntax comprehension test, and other language versions of the test for reception of grammar (TROG-2) were investigated to extract constructs [16, 18, 19, 33, 34, 36, 38, 41, 43].

Finally, after 6 stages, 39 grammatical constructs were determined based on the literature review, clinical experience of the research team, and experimental evidence, and 3 new constructs were extracted from expert interviews. Finally, 42 grammar constructions suitable for the design of the ATGCT test were compiled.

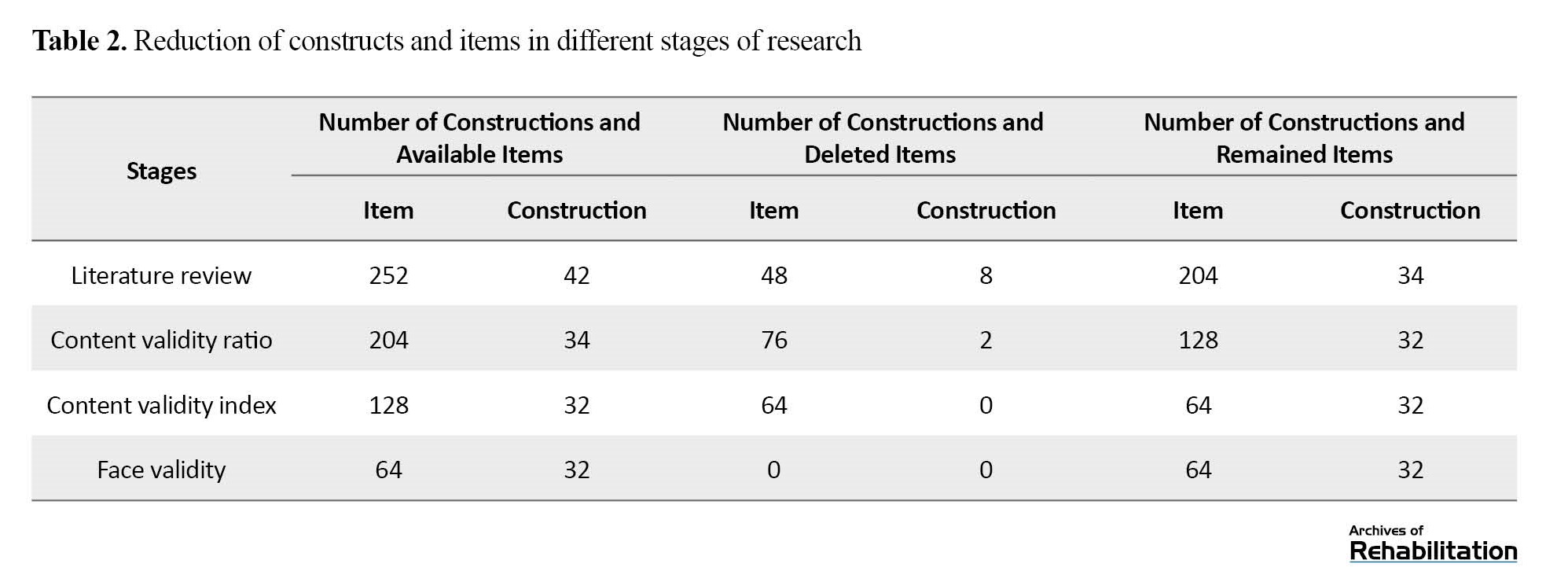

The second step: Reduction of grammatical constructions

At this stage, some command constructions were removed. In other words, eight constructions were removed, and finally, 34 grammatical constructions remained.

The third step: Designing the pool of items

At first, 6 items were designed for each grammatical structure. The expected number of items for the final version of the test was about 50 to 60 items. In this stage, 204 items were designed, almost four times as many as the final items.

1. Keywords based on the study of children’s vocabulary between 18 and 24 months were used to design items [44].

2. Since the test was designed to evaluate the understanding of grammatical relations and checking vocabulary skills was not the test’s purpose, limited vocabulary was used [41].

3. The most frequent syllabic constructions in the Azerbaijani-Turkish language were used to select the test words [39].

4. To reduce the possibility of poor performance due to attention disorders, subjects could repeat all the test items if necessary [45].

5. One of the essential features of the grammar comprehension test for designing items was imageability [29].

6. All the test items, except for the irreversible construction, were designed to be reversible [45, 46].

7. The last criterion for the design of items was to match the features of the Azerbaijani-Turkish language and not to translate from another language. The set of initial items consisted of 204 items, including 985 words (496 content words and 206 miscellaneous content words).

The fourth stage: Determination of content validity

A list of grammatical constructions and test items was presented to 11 experts (6 speech and language pathologists and 5 linguists) in two separate forms to check its content validity. A systematic analysis of experts’ opinions was done by the research team, and finally, the content validity of the selected items was examined. To calculate content validity quantitatively, the content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were calculated [48, 49].

Results

The first step: Determining the content validity ratio

The minimum CVR values for constructions and grammatical items were 0.59. In other words, 128 items were selected based on CVR values (CVR >0.59), and all selected items were selected for image design and CVI calculation.

The second step: Designing images

We aimed to design a visual, colored, cartoony, and four-choice test. At this stage, the images of 128 items were designed based on Iranian and Azerbaijani culture. A series of electronic images were designed for the subjects and arranged in a file. The design of target images and distracting factors was of special importance. After being designed and modified by the research team members, the images were presented to 5 speech and language pathologists and a professional illustrator to express their opinions about the clarity of the images. Finally, their comments were reviewed by the research team and transferred to the illustrator.

The third step: Determining the content validity index

To calculate the content validity index, 11 other experts were asked to rate the test items. The criterion of the present study to report the CVI index was the scale-content validity index/average (S-CVI/Ave) method [50]. In this research, a score greater than or equal to 0.79 was considered to have a suitable content validity index, and according to the CVI results, no items were excluded. However, according to the research team members’ decision, it was decided that for each grammatical construction, 2 items with high CVI should be selected from 4 items and included in the test. For this reason, 64 other items were also removed at this stage, and the initial version of the test had 32 grammatical constructions and 64 items.

The fifth stage: Preliminary study and face validity calculation

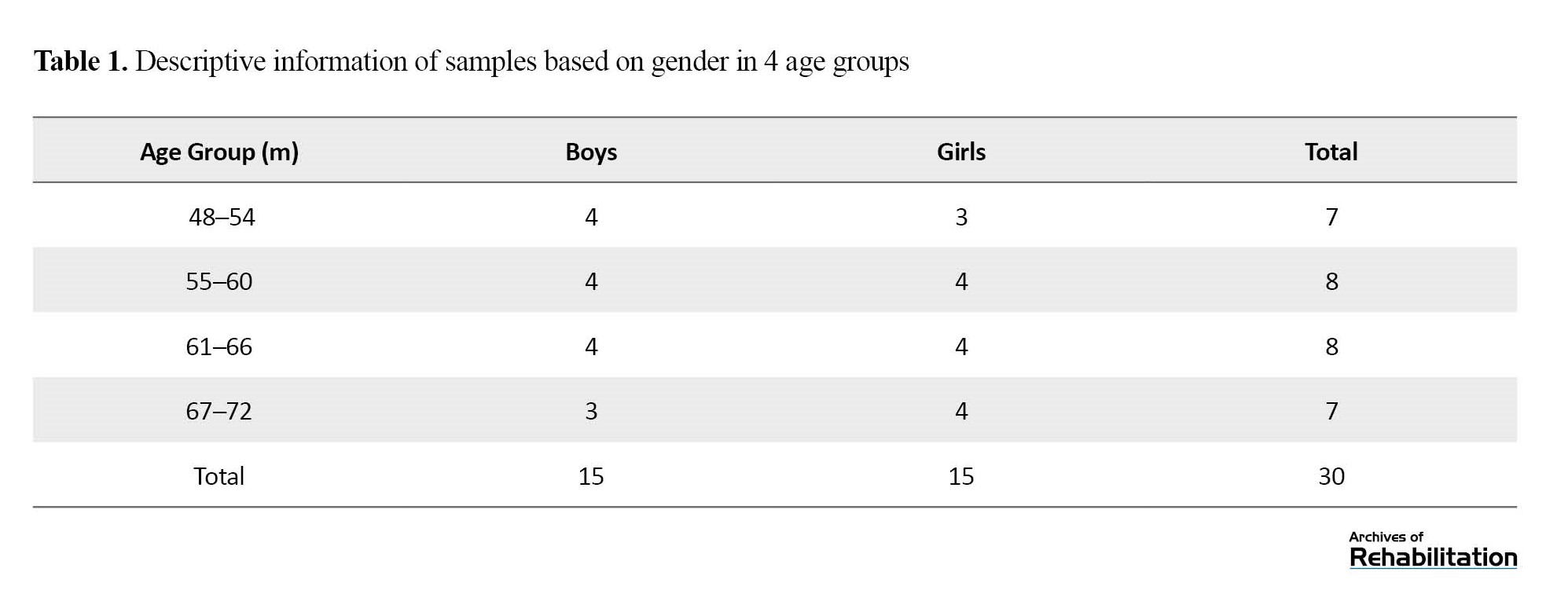

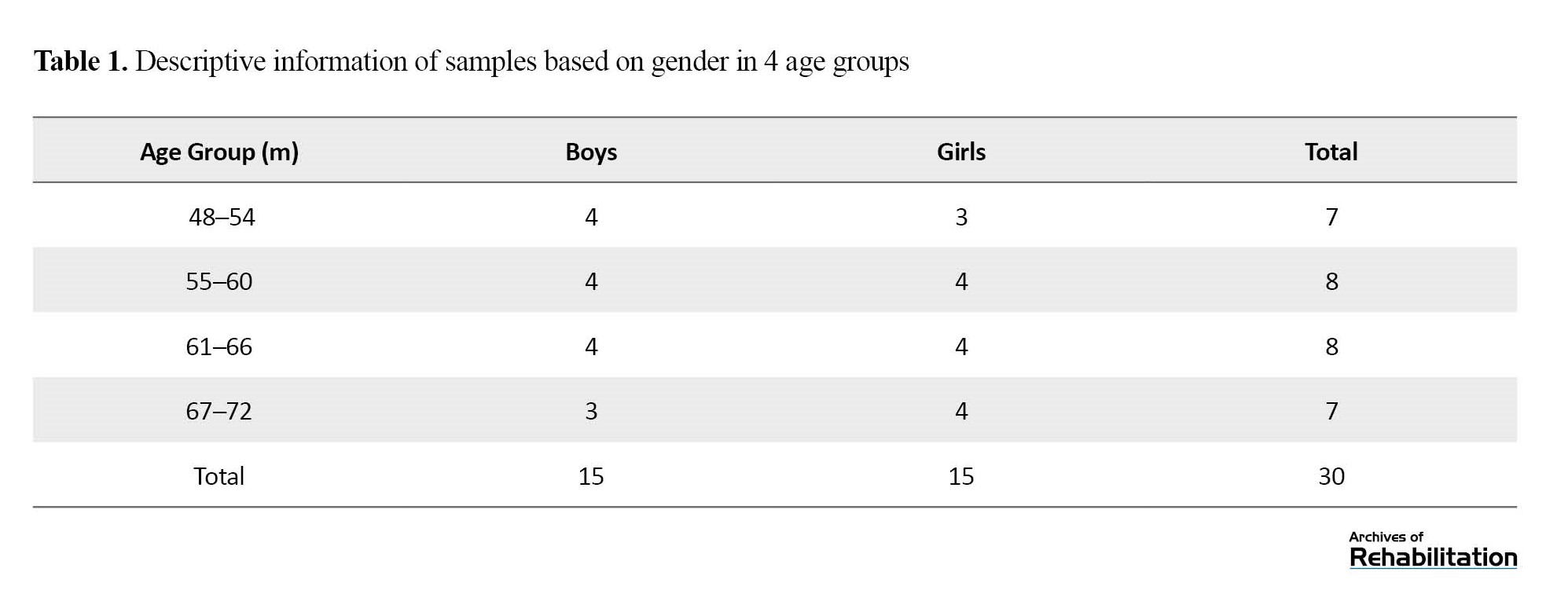

The initial study to remove or edit images, words, and objects was conducted on 30 children aged 4-6 years in a quiet room by the first author for one month (Table 1).

The samples were recruited by cluster random sampling. The studied samples were selected from the kindergartens of the 5 educational districts in Tabriz City, Iran. The inclusion criteria included the age range of 4 to 6 years, Azerbaijani-Turkish as the first language, absence of hearing loss and otitis media, absence of brain damage, or congenital and chromosomal abnormalities. It was necessary to have a normal history of speech and language development, a score above 85 on Wechsler’s preschool IQ scale, and a score corresponding to each age group in the ages and stages questionnaire [51]. Children were excluded from the study if they or their parents did not want to participate in the test. In addition, children were excluded from the study if they had any speech and language disorders. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were evaluated using formal and informal evaluations by speech and language pathologists and psychologists, completion of questionnaires by parents, examination of children’s medical history, and teachers’ reports in kindergarten.

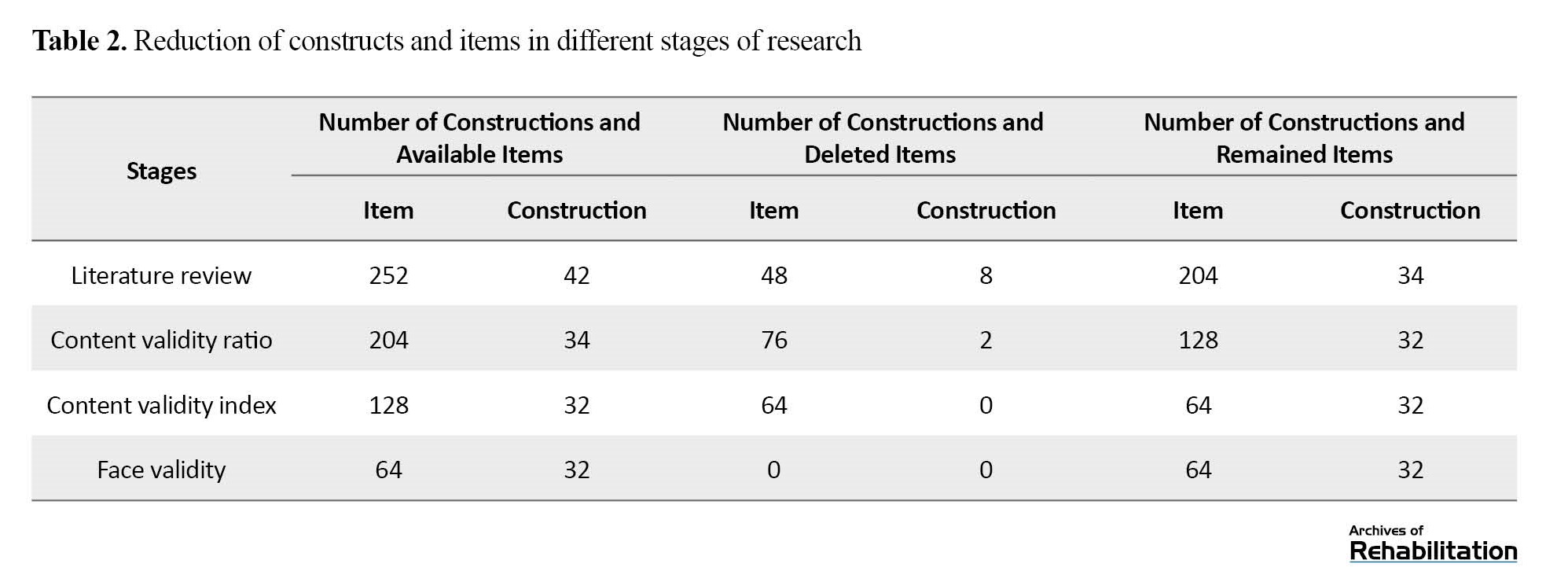

The purpose of the preliminary study was a qualitative analysis of images and items and a calculation of face validity. Therefore, not only the children’s responses to the test items but also their executive performance and verbal expression were recorded, which is important for compiling the final version of the ATGCT. After the initial implementation of the test on 30 children aged 4 to 6 years, there were no incorrect items, and only 10 items were corrected (Table 2).

Finally, the face validity of the items was considered appropriate.

Discussion

This study was conducted to design and examine the content and face validity of an Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test for 4-6 years old children. The grammatical constructions of the test were extracted through a systematic process, interviews with a team of experts, examination of Azeri-Turkish grammar texts (published books and articles), and examination of tests and assignments in other languages. Considering that the present study was the design of the first Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar test, various grammar constructions should be extracted with a different range of complexity, and the constructions should be selected according to the experts’ point of view. In the first stage, 46 grammatical constructions were extracted. Then, based on experts’ opinions, 8 grammatical constructions were removed, and 34 suitable constructions were left to evaluate children’s understanding of grammar. Experts believed these deleted constructions were difficult for preschool children and should be removed. Then, after calculating the CVR, 2 grammatical constructions and 76 items were also removed. The reason for eliminating constructions 33 and 34 was that they mostly showed lexical and semantic relations and did not have the grammatical features required by ATGCT.

In the next step, illustrating was done, and finally, after calculating the CVI, 2 items were selected for the remaining 32 grammatical constructions. The average CVI for grammatical constructions and items were 0.81 and 0.87, respectively. Also, the average CVR values for grammatical constructions and items were 0.84 and 0.91, respectively. The results showed that ATGCT has adequate content and face validity and was aligned with the second version of the TROG and Persian syntax comprehension test (PSCT). The TROG-2 test has good validity, and the psychometric properties examined in PSCT with the content validity of each item are between 0.47 and 1.00, with a total validity of 0.79 [18, 19].

Evaluating language disorders and grammar defects before children enter school is necessary. One of the most important features of the present test was the use of clear and attractive images with suitable colors for young children; the color distribution in the four options of each item was carefully considered, and the images were designed in such a way that there was no chance for paying attention to one of the options more than the others [52]. Despite the attention of the research team of the present study to the criteria related to the design of images, these features are less observed in the TROG-2 and PSCT tests. In these tests, images less visually appealing to children are often used. Also, relatively simple and practical keywords were used in the design of the test items, and colloquial language was chosen to express the items during the test. Another feature of the test was using the same and common words in all language dialects, which makes it applicable in all Azerbaijani and Turkish languages. The method of answering the ATGCT test was similar to TROG-2 and PSCT, based on matching the sentence with the target image [38]. Since this method can analyze grammatical errors, it is an effective clinical tool for diagnosing and planning therapeutic interventions [52].

Another feature of ATGCT is its short form and quick implementation, so the time required to perform this test is 15 to 20 minutes, and unlike the speech sampling method, data analysis is done in a very short period. Many versions of TROG and PSCT have different constructions and items that affect the duration of the test. The time required to perform ATGCT is shorter than TROG-2 and PSCT [16, 18, 41-43]. The TROG-2 test has 20 grammatical constructions and 80 items, the Spanish version of TROG has 20 constructions and 79 items, the French version includes 24 constructions and 20 items, the Bosnian version has 21 constructions and 21 items, and the Swedish version includes 20 constructions and 20 items. Also, PSCT includes 24 constructs and 96 items, while ATGCT has 32 constructs and 64 items [18, 43, 53-55]. Compared to other tests, ATGCT evaluates many more grammatical constructions in a shorter time, and this advantage is valuable in the clinical application of this tool because the test execution time is critical. Also, the PSCT test only evaluates syntactic skills, while ATGCT, like TROG-2, evaluates morphological and syntactic skills [19].

Conclusion

The present study was the first step towards developing a language test in the developmental area for the Azerbaijani-Turkish language, in which the sequential steps of extracting grammatical constructions, designing items, and examining its psychometric properties were described. The constructions and items of the grammar test were completely based on the characteristics of the Azerbaijani-Turkish language, and the pictures were designed based on Iranian culture. They are suitable for children aged 4-6 years. The results of the test design section and calculation of content and form validity showed that the Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test has good content and face validity. Also, the present test can be used to study the understanding of language grammar and the developmental sequence of its acquisition. It can improve the quality of services in clinical and research fields.

In the next stage and as a second pilot study, the items will be implemented on 200 children aged 4 to 6 years with Azerbaijani-Turkish language. Finally, the items will be analyzed, and the indicators of difficulty and distinction will be calculated. Also, by completing the psychometric process, checking construct validity and reliability, and calculating sensitivity and specificity, it will be possible for therapists and researchers to use the test.

One of the limitations of the present study was the lack of studies related to Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar and its acquisition sequence in children with normal speech and language development and those with language disorders. Another limitation of the present study was the absence of an official language assessment test to diagnose Azeri-Turkish-speaking children, and the research team inevitably used informal clinical judgments to diagnose children with normal speech and language development participating in the research. Finally, it is suggested that the construct validity and reliability be checked in future research so that the final version of ATGCT is published. Therefore, the strength of the present study is its innovation in designing a special test for the Azerbaijani-Turkish language in speech therapy.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences approved the current research (Code: ID IR.USWR.REC.1401.06). The principle of scientific integrity and the recording of participants’ answers were recorded without any intervention. The utmost trustworthiness and honesty were done during data collection and review of available sources.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Fatemeh Fekar Qaramelki, approved by Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. The research was supported by the Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences and the Development Headquarters of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies.

Authors' contributions

Data collection: Fatemeh Fekar Qaramalki, and Akbar Daghi; Data analysis: Fatemeh Fakar Qaramalki, Abbas Ebadi, and Akbar Daghi; Conceptualization, methodology, writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

All authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the cooperation of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, the University’s Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, and the Development Headquarters of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies in conducting this study.

References

Full-Text: (1442 Views)

Introduction

Understanding language is the ability to acquire the meaning of the language message, and understanding grammar is its integral part [1, 2, 3]. The development of grammar is an essential stage in development and enables the child to understand complex sentences and participate in daily communication [1]. In addition, grammar mastery is an important predictive factor for academic learning and is essential for success [5]. As a result, early diagnosis of children’s language disorders before entering school is crucial [7].

Two types of formal and informal assessment are prevalent in speech therapy’s clinical and research fields [8]. The lack of an official test to evaluate the Azerbaijani-Turkish language in children is one of the main problems of speech and language pathologists in Iran, Azerbaijan, and Turkey [7, 8]. Therefore, conducting valid interventions and research requires official tests in every language.

Generally, the tests available to evaluate grammar can be classified into three groups. The first group consists of the tests that assess both aspects of understanding and expressing the command. The second group of tests specifically evaluates expressive language grammar. In the third group, tests specifically evaluate grammar comprehension [9, 10, 11].

Grammar comprehension tests have several advantages. For example, they provide language evaluation in non-verbal children and examine the child’s potential grammatical constructions through comprehension evaluation before they appear in speech [20, 21]. Also, the presentation of items and answers can be controlled more in comprehension evaluation than in the expressive evaluation [13]. Grammar comprehension is the most crucial defect in developmental language disorder (DLD) [18]. For evaluation, it is inevitable to use informal or non-specialized methods [20, 21]. Since no study has been conducted worldwide to design an Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test, the lack of a valid and reliable test is one of the most important problems we face in evaluating children with language disorders.

Azerbaijani-Turkish is a branch of Altaic Turkish spoken in Iran, Iraq, and Azerbaijan [22, 23]. Also, there are Azeri-Turkish speakers in the Caucasus, Georgia, Armenia, and Dagestan [22, 23]. More than 50 million people worldwide speak the Azerbaijani-Turkish language [23]. Among non-Persian Iranian languages, Turkish-Azerbaijani accounts for the largest speakers, with about 15 to 20 million [24]. Considering the distinctive characteristics of the Azerbaijani-Turkish language, the lack of grammar comprehension tests in the world for this language, and the impossibility of using tests of other languages, such as the tests available in Farsi, there is a pressing need to design an utterly native test. This research describes the steps necessary to produce items and analyzes their content and formal validity. The present study was conducted to design and determine the preliminary validity of an Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test (ATGCT) in children aged 4-6 years based on the characteristics of Azerbaijani-Turkish language and Iranian culture.

Materials and Methods

This methodological study was conducted through exploratory mixed research (qualitative-quantitative) in two general parts: To design and preliminary validate the Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test in children 4-6 years old in northwest Iran.

Test design

The design of the Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test was done in five stages based on the systematic test design model [26]. Figure 1 shows the step-by-step design of ATGCT and its validity determination.

Understanding language is the ability to acquire the meaning of the language message, and understanding grammar is its integral part [1, 2, 3]. The development of grammar is an essential stage in development and enables the child to understand complex sentences and participate in daily communication [1]. In addition, grammar mastery is an important predictive factor for academic learning and is essential for success [5]. As a result, early diagnosis of children’s language disorders before entering school is crucial [7].

Two types of formal and informal assessment are prevalent in speech therapy’s clinical and research fields [8]. The lack of an official test to evaluate the Azerbaijani-Turkish language in children is one of the main problems of speech and language pathologists in Iran, Azerbaijan, and Turkey [7, 8]. Therefore, conducting valid interventions and research requires official tests in every language.

Generally, the tests available to evaluate grammar can be classified into three groups. The first group consists of the tests that assess both aspects of understanding and expressing the command. The second group of tests specifically evaluates expressive language grammar. In the third group, tests specifically evaluate grammar comprehension [9, 10, 11].

Grammar comprehension tests have several advantages. For example, they provide language evaluation in non-verbal children and examine the child’s potential grammatical constructions through comprehension evaluation before they appear in speech [20, 21]. Also, the presentation of items and answers can be controlled more in comprehension evaluation than in the expressive evaluation [13]. Grammar comprehension is the most crucial defect in developmental language disorder (DLD) [18]. For evaluation, it is inevitable to use informal or non-specialized methods [20, 21]. Since no study has been conducted worldwide to design an Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test, the lack of a valid and reliable test is one of the most important problems we face in evaluating children with language disorders.

Azerbaijani-Turkish is a branch of Altaic Turkish spoken in Iran, Iraq, and Azerbaijan [22, 23]. Also, there are Azeri-Turkish speakers in the Caucasus, Georgia, Armenia, and Dagestan [22, 23]. More than 50 million people worldwide speak the Azerbaijani-Turkish language [23]. Among non-Persian Iranian languages, Turkish-Azerbaijani accounts for the largest speakers, with about 15 to 20 million [24]. Considering the distinctive characteristics of the Azerbaijani-Turkish language, the lack of grammar comprehension tests in the world for this language, and the impossibility of using tests of other languages, such as the tests available in Farsi, there is a pressing need to design an utterly native test. This research describes the steps necessary to produce items and analyzes their content and formal validity. The present study was conducted to design and determine the preliminary validity of an Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test (ATGCT) in children aged 4-6 years based on the characteristics of Azerbaijani-Turkish language and Iranian culture.

Materials and Methods

This methodological study was conducted through exploratory mixed research (qualitative-quantitative) in two general parts: To design and preliminary validate the Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test in children 4-6 years old in northwest Iran.

Test design

The design of the Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test was done in five stages based on the systematic test design model [26]. Figure 1 shows the step-by-step design of ATGCT and its validity determination.

The first stage: Test outline

In the first step, the grammatical constructions of the Azerbaijani-Turkish language were determined, and the necessary steps for content and formal validity were carried out. The ATGCT exam format is paper-based and evaluates grammar using visual stimuli and images.

The second stage: Describing the concept and determining the specifications of the test

First, grammatical constructions in the Azerbaijani-Turkish language test should be determined [26]. To select the structure of the test, four main criteria were considered based on the review of reports of other similar tests and the opinions of the research team [28]. The first criterion was frequency [29]. The second criterion was the imageability test, considered in all stages [30]. The third criterion was the simplicity or complexity of grammatical construction [3]. The fourth criterion was the clinical importance of grammatical construction [31]. Finally, all grammatical constructions with low frequency and high clinical importance were included in the initial version of the test [26].

At this stage, the general characteristics of the test were determined. Finally, 2 items were designed to evaluate each grammar construct. One of the most essential features of ATGCT was that the examiner expressed the target sentence colloquially.

The third stage: Determining grammatical constructions and test items

Three consecutive steps were done: Extracting grammatical constructions, reducing grammatical constructions, and creating a pool of items.

The first step: Extraction of grammar constructions

Six steps were followed to select grammatical constructions:

1. All old and new sources, including Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar books and articles, were reviewed [22-24, 33, 36].

2. Existing empirical evidence on grammar comprehension deficits in DLDs and other language disorders was reviewed [37].

3. Also, a sample of spontaneous speech of 10 Azeri-Turkish-speaking children from Tabriz City, Iran, aged 3-9 years old, was analyzed to extract some constructions from their speech.

4. Studies related to common keywords and syllabic construction in Azeri-Turkish-speaking children aged 18-24 months were used to design test items [39].

5. Informal individual and group interviews with speech therapy and linguistics experts were conducted through a panel of experts and semi-structured interviews. The experts were asked to express their opinions on each grammar construction for 4-6 years old children in the Azeri-Turkish language. Finally, approved grammatical constructions were listed.

6. At this stage, English, Farsi, Azerbaijani-Turkish language tests were examined to identify and adapt suitable constructions. Azerbaijani-Turkish version of the bilingual aphasia test, Azari aphasia screening test, Turkish-Azari aphasia test, Persian and English language development test, grammar comprehension test-version 2, Farsi syntax comprehension test, and other language versions of the test for reception of grammar (TROG-2) were investigated to extract constructs [16, 18, 19, 33, 34, 36, 38, 41, 43].

Finally, after 6 stages, 39 grammatical constructs were determined based on the literature review, clinical experience of the research team, and experimental evidence, and 3 new constructs were extracted from expert interviews. Finally, 42 grammar constructions suitable for the design of the ATGCT test were compiled.

The second step: Reduction of grammatical constructions

At this stage, some command constructions were removed. In other words, eight constructions were removed, and finally, 34 grammatical constructions remained.

The third step: Designing the pool of items

At first, 6 items were designed for each grammatical structure. The expected number of items for the final version of the test was about 50 to 60 items. In this stage, 204 items were designed, almost four times as many as the final items.

1. Keywords based on the study of children’s vocabulary between 18 and 24 months were used to design items [44].

2. Since the test was designed to evaluate the understanding of grammatical relations and checking vocabulary skills was not the test’s purpose, limited vocabulary was used [41].

3. The most frequent syllabic constructions in the Azerbaijani-Turkish language were used to select the test words [39].

4. To reduce the possibility of poor performance due to attention disorders, subjects could repeat all the test items if necessary [45].

5. One of the essential features of the grammar comprehension test for designing items was imageability [29].

6. All the test items, except for the irreversible construction, were designed to be reversible [45, 46].

7. The last criterion for the design of items was to match the features of the Azerbaijani-Turkish language and not to translate from another language. The set of initial items consisted of 204 items, including 985 words (496 content words and 206 miscellaneous content words).

The fourth stage: Determination of content validity

A list of grammatical constructions and test items was presented to 11 experts (6 speech and language pathologists and 5 linguists) in two separate forms to check its content validity. A systematic analysis of experts’ opinions was done by the research team, and finally, the content validity of the selected items was examined. To calculate content validity quantitatively, the content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were calculated [48, 49].

Results

The first step: Determining the content validity ratio

The minimum CVR values for constructions and grammatical items were 0.59. In other words, 128 items were selected based on CVR values (CVR >0.59), and all selected items were selected for image design and CVI calculation.

The second step: Designing images

We aimed to design a visual, colored, cartoony, and four-choice test. At this stage, the images of 128 items were designed based on Iranian and Azerbaijani culture. A series of electronic images were designed for the subjects and arranged in a file. The design of target images and distracting factors was of special importance. After being designed and modified by the research team members, the images were presented to 5 speech and language pathologists and a professional illustrator to express their opinions about the clarity of the images. Finally, their comments were reviewed by the research team and transferred to the illustrator.

The third step: Determining the content validity index

To calculate the content validity index, 11 other experts were asked to rate the test items. The criterion of the present study to report the CVI index was the scale-content validity index/average (S-CVI/Ave) method [50]. In this research, a score greater than or equal to 0.79 was considered to have a suitable content validity index, and according to the CVI results, no items were excluded. However, according to the research team members’ decision, it was decided that for each grammatical construction, 2 items with high CVI should be selected from 4 items and included in the test. For this reason, 64 other items were also removed at this stage, and the initial version of the test had 32 grammatical constructions and 64 items.

The fifth stage: Preliminary study and face validity calculation

The initial study to remove or edit images, words, and objects was conducted on 30 children aged 4-6 years in a quiet room by the first author for one month (Table 1).

The samples were recruited by cluster random sampling. The studied samples were selected from the kindergartens of the 5 educational districts in Tabriz City, Iran. The inclusion criteria included the age range of 4 to 6 years, Azerbaijani-Turkish as the first language, absence of hearing loss and otitis media, absence of brain damage, or congenital and chromosomal abnormalities. It was necessary to have a normal history of speech and language development, a score above 85 on Wechsler’s preschool IQ scale, and a score corresponding to each age group in the ages and stages questionnaire [51]. Children were excluded from the study if they or their parents did not want to participate in the test. In addition, children were excluded from the study if they had any speech and language disorders. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were evaluated using formal and informal evaluations by speech and language pathologists and psychologists, completion of questionnaires by parents, examination of children’s medical history, and teachers’ reports in kindergarten.

The purpose of the preliminary study was a qualitative analysis of images and items and a calculation of face validity. Therefore, not only the children’s responses to the test items but also their executive performance and verbal expression were recorded, which is important for compiling the final version of the ATGCT. After the initial implementation of the test on 30 children aged 4 to 6 years, there were no incorrect items, and only 10 items were corrected (Table 2).

Finally, the face validity of the items was considered appropriate.

Discussion

This study was conducted to design and examine the content and face validity of an Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test for 4-6 years old children. The grammatical constructions of the test were extracted through a systematic process, interviews with a team of experts, examination of Azeri-Turkish grammar texts (published books and articles), and examination of tests and assignments in other languages. Considering that the present study was the design of the first Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar test, various grammar constructions should be extracted with a different range of complexity, and the constructions should be selected according to the experts’ point of view. In the first stage, 46 grammatical constructions were extracted. Then, based on experts’ opinions, 8 grammatical constructions were removed, and 34 suitable constructions were left to evaluate children’s understanding of grammar. Experts believed these deleted constructions were difficult for preschool children and should be removed. Then, after calculating the CVR, 2 grammatical constructions and 76 items were also removed. The reason for eliminating constructions 33 and 34 was that they mostly showed lexical and semantic relations and did not have the grammatical features required by ATGCT.

In the next step, illustrating was done, and finally, after calculating the CVI, 2 items were selected for the remaining 32 grammatical constructions. The average CVI for grammatical constructions and items were 0.81 and 0.87, respectively. Also, the average CVR values for grammatical constructions and items were 0.84 and 0.91, respectively. The results showed that ATGCT has adequate content and face validity and was aligned with the second version of the TROG and Persian syntax comprehension test (PSCT). The TROG-2 test has good validity, and the psychometric properties examined in PSCT with the content validity of each item are between 0.47 and 1.00, with a total validity of 0.79 [18, 19].

Evaluating language disorders and grammar defects before children enter school is necessary. One of the most important features of the present test was the use of clear and attractive images with suitable colors for young children; the color distribution in the four options of each item was carefully considered, and the images were designed in such a way that there was no chance for paying attention to one of the options more than the others [52]. Despite the attention of the research team of the present study to the criteria related to the design of images, these features are less observed in the TROG-2 and PSCT tests. In these tests, images less visually appealing to children are often used. Also, relatively simple and practical keywords were used in the design of the test items, and colloquial language was chosen to express the items during the test. Another feature of the test was using the same and common words in all language dialects, which makes it applicable in all Azerbaijani and Turkish languages. The method of answering the ATGCT test was similar to TROG-2 and PSCT, based on matching the sentence with the target image [38]. Since this method can analyze grammatical errors, it is an effective clinical tool for diagnosing and planning therapeutic interventions [52].

Another feature of ATGCT is its short form and quick implementation, so the time required to perform this test is 15 to 20 minutes, and unlike the speech sampling method, data analysis is done in a very short period. Many versions of TROG and PSCT have different constructions and items that affect the duration of the test. The time required to perform ATGCT is shorter than TROG-2 and PSCT [16, 18, 41-43]. The TROG-2 test has 20 grammatical constructions and 80 items, the Spanish version of TROG has 20 constructions and 79 items, the French version includes 24 constructions and 20 items, the Bosnian version has 21 constructions and 21 items, and the Swedish version includes 20 constructions and 20 items. Also, PSCT includes 24 constructs and 96 items, while ATGCT has 32 constructs and 64 items [18, 43, 53-55]. Compared to other tests, ATGCT evaluates many more grammatical constructions in a shorter time, and this advantage is valuable in the clinical application of this tool because the test execution time is critical. Also, the PSCT test only evaluates syntactic skills, while ATGCT, like TROG-2, evaluates morphological and syntactic skills [19].

Conclusion

The present study was the first step towards developing a language test in the developmental area for the Azerbaijani-Turkish language, in which the sequential steps of extracting grammatical constructions, designing items, and examining its psychometric properties were described. The constructions and items of the grammar test were completely based on the characteristics of the Azerbaijani-Turkish language, and the pictures were designed based on Iranian culture. They are suitable for children aged 4-6 years. The results of the test design section and calculation of content and form validity showed that the Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test has good content and face validity. Also, the present test can be used to study the understanding of language grammar and the developmental sequence of its acquisition. It can improve the quality of services in clinical and research fields.

In the next stage and as a second pilot study, the items will be implemented on 200 children aged 4 to 6 years with Azerbaijani-Turkish language. Finally, the items will be analyzed, and the indicators of difficulty and distinction will be calculated. Also, by completing the psychometric process, checking construct validity and reliability, and calculating sensitivity and specificity, it will be possible for therapists and researchers to use the test.

One of the limitations of the present study was the lack of studies related to Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar and its acquisition sequence in children with normal speech and language development and those with language disorders. Another limitation of the present study was the absence of an official language assessment test to diagnose Azeri-Turkish-speaking children, and the research team inevitably used informal clinical judgments to diagnose children with normal speech and language development participating in the research. Finally, it is suggested that the construct validity and reliability be checked in future research so that the final version of ATGCT is published. Therefore, the strength of the present study is its innovation in designing a special test for the Azerbaijani-Turkish language in speech therapy.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences approved the current research (Code: ID IR.USWR.REC.1401.06). The principle of scientific integrity and the recording of participants’ answers were recorded without any intervention. The utmost trustworthiness and honesty were done during data collection and review of available sources.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Fatemeh Fekar Qaramelki, approved by Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. The research was supported by the Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences and the Development Headquarters of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies.

Authors' contributions

Data collection: Fatemeh Fekar Qaramalki, and Akbar Daghi; Data analysis: Fatemeh Fakar Qaramalki, Abbas Ebadi, and Akbar Daghi; Conceptualization, methodology, writing and final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

All authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the cooperation of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, the University’s Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, and the Development Headquarters of Cognitive Sciences and Technologies in conducting this study.

References

- Meisel JM. Parameters in acquisition. In: Fletcher P, MacWhinney B, editors. The handbook of child language. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2017. [DOI:10.1111/b.9780631203124.1996.00002.x]

- Scott C. Syntactic ability in children and adolescents with language and learning disabilities. In: Berman PA, editor. Language development across childhood and adolescence. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2004. [DOI:10.1075/tilar.3.09sco]

- Tallerman M. Understanding syntax. London: Routledge; 2019. [DOI:10.4324/9780429243592]

- MacDonald MC, Seidenberg MS. Constraint satisfaction accounts of lexical and sentence comprehension. In: Traxler MJ, Gernsbacher MA, editors. Handbook of psycholinguistics. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2006. [DOI:10.1016/B978-012369374-7/50016-X]

- Saracho ON. Research, policy, and practice in early childhood literacy. Early Child Development and Care. 2017; 187(3-4):305-21. [DOI:10.1080/03004430.2016.1261512]

- Snowling MJ, Bishop DV, Stothard SE, Chipchase B, Kaplan C. Psychosocial outcomes at 15 years of children with a preschool history of speech-language impairment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2006; 47(8):759-65. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01631.x] [PMID]

- Ren Y, Rattanasone NX, Demuth K, Andronos F, Wyver S. Relationships between proficiency with grammatical morphemes and emotion regulation: A study of Mandarin-English preschoolers. Early Child Development and Care. 2018; 188(8):1055-62. [DOI:10.1080/03004430.2016.1245189]

- Khoja MA. A survey of formal and informal assessment procedures used by speech-language pathologists in Saudi Arabia. Speech, Language and Hearing. 2019; 22(2):91-9. [DOI:10.1080/2050571X.2017.1407620]

- Tran TV. Developing cross-cultural measurement. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2009. [DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195325089.001.0001]

- Khoza-Shangase K, Mophosho M. Language and culture in speech-language and hearing professions in South Africa: The dangers of a single story. The South African Journal of Communication Disorders. 2018; 65(1):e1-7. [DOI:10.4102/sajcd.v65i1.594] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Spengler PM, Pilipis LA. A comprehensive meta-reanalysis of the robustness of the experience-accuracy effect in clinical judgment. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2015; 62(3):360-78. [DOI:10.1037/cou0000065] [PMID]

- Lee LL. A screening test for syntax development. The Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1970; 35(2):103-12. [DOI:10.1044/jshd.3502.103] [PMID]

- Rice M, Wexler K. Test of early grammatical impairment (TEGI). London: Pearson Publishing; 2001. [Link]

- Shipley KG, Stone TA, Sue MB. Test for examining expressive morphology (TEEM). Tucson: Communication Skill Builders; 1983. [Link]

- Perona K, Plante E, Vance R. Diagnostic accuracy of the structured photographic expressive language test: Third edition (SPELT-3). Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2005; 36(2):103-15. [DOI:10.1044/0161-1461(2005/010)] [PMID]

- Haresabadi F, Ebadi A, Sima Shirazi T, Dastjerdi Kazemi M. Design and validate a photographic expressive persian grammar test for children aged 4-6. Child Language Teaching and Therapy. 2016; 32(2):193-204. [DOI:10.1177/0265659015595445]

- Jones BW, Grygar J. The test of syntactic abilities and microcomputers. American Annals of the Deaf. 1982; 127(5):638-44. [DOI:10.1353/aad.2012.1066] [PMID]

- Bishop DV. Test for reception of grammar: Version 2: TROG-2 manual. San Antonio: Harcourt Assessment; 2003. [Link]

- Mohamadi R, Ahmadi A, Kazemi MD, Minaei A, Damarchi Z. Development of the Persian syntax comprehension test. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2019; 124:22-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2019.05.032] [PMID]

- Snowling MJ, Hayiou-Thomas ME, Nash HM, Hulme C. Dyslexia and developmental language disorder: Comorbid disorders with distinct effects on reading comprehension. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2020; 61(6):672-80. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.13140] [PMID]

- Neugebauer J, Tóthová V, Doležalová J. Use of standardized and non-standardized tools for measuring the risk of falls and independence in clinical practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(6):3226. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18063226] [PMID]

- Lee SN. A grammar of Iranian Azerbaijani. Seoul: The Altaic Society of Korea; 1996. [Link]

- Asadpour H. Parts of speech and the placement of targets in the corpus of languages in northwestern Iran. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory. 2022; 19(3):487-522. [DOI:10.1515/cllt-2022-0001]

- Mahmoodi S. [Sonority-driven phonological processes in Turkic Languages (Persian)]. Language Related Research, 2017; 8(5):235-68. [Link]

- Windle G, Bennett KM, Noyes J. A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2011; 9:8. [DOI:10.1186/1477-7525-9-8] [PMID] []

- Downing SM. Selected-response item formats in test development. In: Dawning SM, Haladyna TM, editors. Handbook of test development. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2006. [Link]

- Larsen-Freeman D, DeCarrico J. Grammar. In: Schmitt N, Rodgers M, editors. An introduction to applied linguistics. Oxfordshire: Routledge; 2019. [DOI:10.4324/9780429424465-2]

- Fekar Gharamaleki F, Bahrami B, Masumi J. Autism screening tests: A narrative review. Journal of Public Health Research. 2021; 11(1):2308. [DOI:10.4081/jphr.2021.2308] [PMID]

- Hoff E. Language development. Pacific Grove: Brooks/Cole Pub; 2013. [Link]

- Bedny M, Thompson-Schill SL. Neuroanatomically separable effects of imageability and grammatical class during single-word comprehension. Brain and Language. 2006; 98(2):127-39. [DOI:10.1016/j.bandl.2006.04.008] [PMID]

- Daub O, Skarakis-Doyle E, Bagatto MP, Johnson AM, Cardy JO. A comment on test validation: the importance of the clinical perspective. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 2019; 28(1):204-210. [DOI:10.1044/2018_AJSLP-18-0048] [PMID]

- Language and Reading Research Consortium (LARRC). Oral language and listening comprehension: Same or different constructs? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2017; 60(5):1273-84. [DOI:10.1044/2017_JSLHR-L-16-0039] [PMID]

- Salehi S, Jahan A, Mousavi N, Hashemilar M, Razaghi Z, Moghadam-Salimi M. Developing Azeri aphasia screening test and preliminary validity and reliability. Iranian Journal of Neurology. 2016; 15( 4):183-8. [PMID]

- Paradis M, Libben G. The assessment of bilingual Aphasia. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis; 2014. [Link]

- Nilipour R. [Persian test of specific language impairment (Persian)]. Tehran: University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, 2002.

- Hasanzadeh S, Minaei A. [Adaptation and standardization of the test of TOLD-P: 3 For Farsi - speaking children of Tehran (Persian)]. Journal of Exceptional Children. 2002; 1(2):119-34. [Link]

- Bishop DVM, Bright P, James C, Bishop SJ, Van Der Lely HKJ. Grammatical SLI: A distinct subtype of developmental language impairment? Applied Psycholinguistics. 2000; 21(2):159-81. [DOI:10.1017/S0142716400002010]

- Schwartz RG. Handbook of child language disorders. New York: Psychology press; 2010. [DOI:10.4324/9780203837764]

- Mirzaee M, Khoshhal Z. [Development of syllable structure in azeri-speaking children (Persian)]. Pajouhan Scientific Journal. 2019; 18(1):30-6. [DOI:10.52547/psj.18.1.30]

- Ahadi H, Abbasi H, Fekar Gharamaleki F. Linguistic and metalinguistic characteristics of Persian-speaking children with autistic spectrum disorders: A systematic review. Journal of Public Health Research. 2023; 12(3). [DOI:10.1177/22799036231189068]

- Farmani E, Fekar Gharamaleki F, Nazari MA. Challenges and opportunities of tele-speech therapy: Before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Health Research. 2024; 13(1):22799036231222115. [PMID]

- Newcomer P, Hamill DD. Test review: Test of Language Development-Primary 3 (TOLD-P:3). Austin: Pro-Ed, Inc; 1997. [Link]

- Pereira MB, Goulart MTC, Mansur LL, Lopes DMB, Negrão EV, Agonilha DC. [Tradução e adaptação do teste de recepção gramatical TROG-2 para o português brasileiro (Portuguese)]. Paper presented at: XVII Congresso Brasileiro de Fonoaudiologia. 24 November 2009; Salvador, Brazil. [Link]

- Kkhoshhal Z, Jahan A, Mirzaee M. [Investigation of most frequent words of Azari-speaking children aged 18 to 24 months (Persian)]. Pajouhan Scientific Journal. 2017; 15(2):32-9. [DOI:10.21859/psj-15026]

- Cheng D, Chen DD, Chen Q, Zhou X. Effects of attention on arithmetic and reading comprehension in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Current Psychology, 2023; 42:17087–96. [DOI:10.1007/s12144-022-02888-4]

- Hsu HJ, Bishop DV. Training understanding of reversible sentences: A study comparing language-impaired children with age-matched and grammar-matched controls. PeerJ. 2014; 2:e656. [DOI:10.7717/peerj.656] [PMID]

- Moran S, Blasi DE, Schikowski R, Küntay AC, Pfeiler B, Allen S, et al. A universal cue for grammatical categories in the input to children: Frequent frames. Cognition. 2018; 175:131-40. [DOI:10.1016/j.cognition.2018.02.005] [PMID]

- Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel psychology. 1975; 28(4):563-75. [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x]

- Ayre C, Scally AJ. Critical values for Lawshe’s content validity ratio: Revisiting the original methods of calculation. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 2014; 47(1):79-86. [DOI:10.1177/0748175613513808]

- Yusoff MSB. ABC of content validation and content validity index calculation. Educational Resource. 2019; 11(2):49-54. [DOI:10.21315/eimj2019.11.2.6]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence-fourth edition. Bloomington: Pearson; 2012. [Link]

- Faccini L, Burke C. Psychological assessment of Autism spectrum disorder and the law. In: Volkmar FR, Loftin R, Westphal A, Woodbury-Smith M, editors. Handbook of Autism spectrum disorder and the law. Berlin: Springer; 2021. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-70913-6_21]

- Anđelković DČ, Nadežda K, Maja S, Oliver T, Nevena B. Assessment of grammar comprehension: Adaptation of TROG for Serbian language. Psihologija. 2007; 40(1):111-32. [DOI:10.2298/PSI0701111A]

- Brandt SE, Svensk A. [Åldersreferenser för TROG, Test for Reception of Grammar, på svenska för flerspråkiga barn i åldrarna 4: 6-5: 6 år (Swedish)] [Msc thesis]. Solna: Karolinska Institutet; 2007. [Link]

- Fekar Gharamaleki F, Darouie A, Ebadi A, Zarifian T, Ahadi H. Development and psychometric evaluation of an Azerbaijani-Turkish grammar comprehension test. Applied Neuropsychology: Child. 2023; 1-12. [Link]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Speech & Language Pathology

Received: 3/03/2023 | Accepted: 21/06/2023 | Published: 22/12/2023

Received: 3/03/2023 | Accepted: 21/06/2023 | Published: 22/12/2023

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |