Volume 25, Issue 3 (Autumn 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(3): 424-447 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Hadian Dehkordi S, Abdi K, Hoseinzadeh S, Sadeghi Z. Design and Psychometrics of a Satisfaction Questionnaire for Tele Speech Therapy Services in Tehran. jrehab 2024; 25 (3) :424-447

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3247-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3247-en.html

1- Department of Rehabilitation Management, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Rehabilitation Management, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,k55abdi@yahoo.com

3- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Science, University of Social welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Rehabilitation Management, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Science, University of Social welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 2077 kb]

(1084 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6062 Views)

Full-Text: (1057 Views)

Introduction

Telecommunication refers to the technology of transmitting signals, images, and messages over long distances via media, such as radio, telephone, television, satellite and so on. Alongside these technological advancements, human lifestyles have considerably been transformed. One of the changes is the use of technology to deliver healthcare services. In recent years, the adoption of telemedicine has increased significantly, driven by advancements in computer sciences and medical device technologies [1].

Telemedicine serves as an alternative and effective method for supervision, surveillance, standardization, and administration of healthcare services, as well as research and development in this field. Studies indicate telemedicine is cost-effective and productive in delivering healthcare services to the general population [2, 3]. Among its various benefits, studies mention the empowerment of patients and healthcare providers, improvements in delivering services, reducing the waiting time and delay in patients’ visits, reduction of hospitalization stays, improvements in the awareness of rural populations, caregivers, and families of the patients, improved accessibility and availability of crucial information, expanded educational networks, and saving in costs and resources of the patients, healthcare providers, and governments [4-7].

Telerehabilitation, as an essential subcategory of telemedicine, facilitates the delivery of rehabilitation services to rural and remote areas [4, 5, 8-16] from experts in telerehabilitation to older people and children with disabilities. Such experts include physiotherapists [16], speech and language therapists (SLTs) [17], occupational therapists [18], audiologists, physicians, rehabilitation engineers, nurses, teachers, psychologists, and nutritionists. Among the participants in this field, the non-expert individuals, such as the family and caregivers of the patients, can be mentioned [19].

Professional communities, such as the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and the Commission on Rehabilitation Counselor Certification (CRCC), hold various viewpoints on telerehabilitation. This method is a novel framework and each organization’s capacity to support or participate in remote activities varies [20].

Satisfaction with a service is an essential outcome, and satisfaction evaluation is regarded as a measure of effectiveness. Therefore, one crucial aspect of telerehabilitation that warrants attention is the satisfaction of families receiving such services. Overall, some studies have evaluated satisfaction, adherence, and acceptance of telerehabilitation from the viewpoint of patients, and their results support the development of this approach [21-23].

The first scientific journal on telerehabilitation was published in 1998. Since then, the number of articles on this topic has increased [1]. Based on the online databases, there is no proper questionnaire to evaluate the satisfaction of the service receiver of speech and language telerehabilitation. Given the development of technology and the spread of COVID-19, the need for such a tool became increasingly apparent. In addition, the existing questionnaires had some limitations.

Accordingly, this study aims to design and psychometrically evaluate a questionnaire assessing satisfaction with remote speech and language telerehabilitation in families with children with speech and language disorders living in Tehran City, Iran. Attempts were made to cover the essential shortcomings of previous research in designing questionnaires in this area.

Materials and Methods

Using a descriptive approach, the current research develops an instrument. The research team prepared the initial draft of the “satisfaction evaluation of families from remote speech therapy” questionnaire after translating and consolidating items in 6 questionnaires regarding the satisfaction evaluation of telemedicine in several sessions [13, 24-28]. Initially, 35 initial items were generated. Then, 11 experienced experts in the field of speech therapy and research instrument development evaluated the content validity of the questionnaire and chose for each item the following choices: “important and relevant,” “can be used, but it is not necessary” and “irrelevant.” The content validity ratio (CVR) was calculated based on these evaluations.

To evaluate the quantitative face validity, 10 parents of children with speech impediments and sound production disorders who had already participated in the remote speech therapy sessions reviewed the questionnaire. They provided their opinions on the relevance of items: “Completely relevant,” “relevant,” “somewhat relevant” and “irrelevant.” the content validity index (CVI) was calculated based on their feedback.

Considering that we had 28 items and 5 to 10 samples per item were adequate for psychometric questionnaires [29], 140 people were considered the sample size for this study (5 samples per item). Regarding the questionnaire’s structural validity, reliability, and repeatability, the samples were chosen via the available sampling from 142 parents of children with speech impediments and sound production disorders who received remote speech therapy services in Tehran City, Iran. The inclusion criteria were children under the age of 7 years, evidence of speech and impediments and sound production based on the assessment of the speech and language therapist, the active presence of at least one of the parents in the treatment sessions, and receiving remote speech and language therapy services in all sessions (to assess the satisfaction of the child, they should have received at least 10 sessions of remote speech therapy services).

The online version of the questionnaire was created in Porsline. The link was sent to families and speech therapists of children with speech impediments and sound production via social networks (Instagram, WhatsApp, Telegram, Bale, Robika, etc.). The repeatability of the questionnaire was assessed via the test re-test method by 30 people in the study sample completing the questionnaire at 2-week intervals.

The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed via CVR, and the lowest approval score of each item was 0.59, as 11 experts participated in the assessment [30]. The structural validity of the questionnaire was assessed via the exploratory factor analysis method, employing the principal axis factoring method with the promax rotation to assign the hidden factors in the questionnaire. The validity of the subscales, the whole questionnaire and the internal consistency were calculated via the Cronbach α method, and the test re-test’s repeatability was obtained by calculating the interclass correlation coefficient. Data analysis was conducted using the SPSS software, version 24.

Results

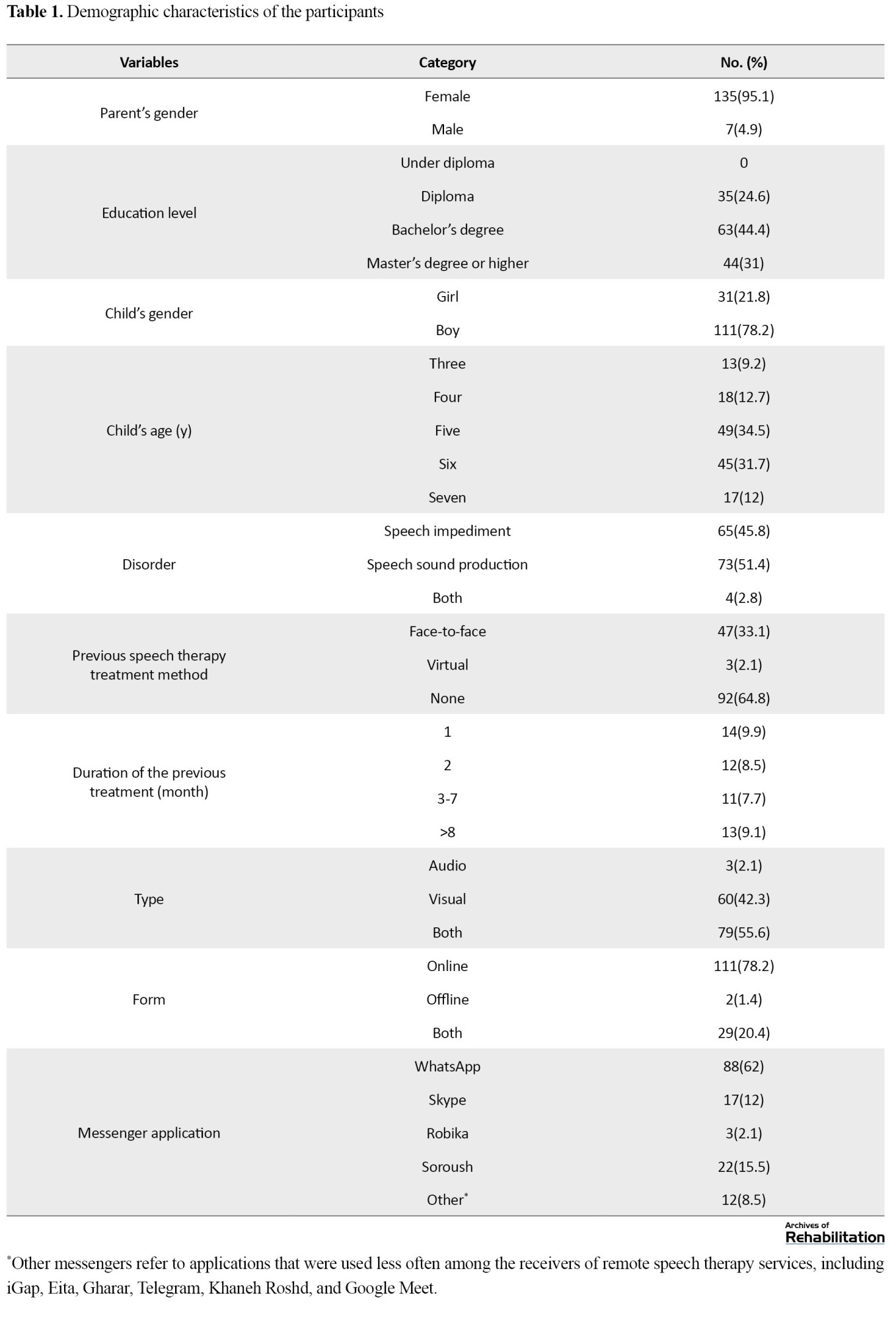

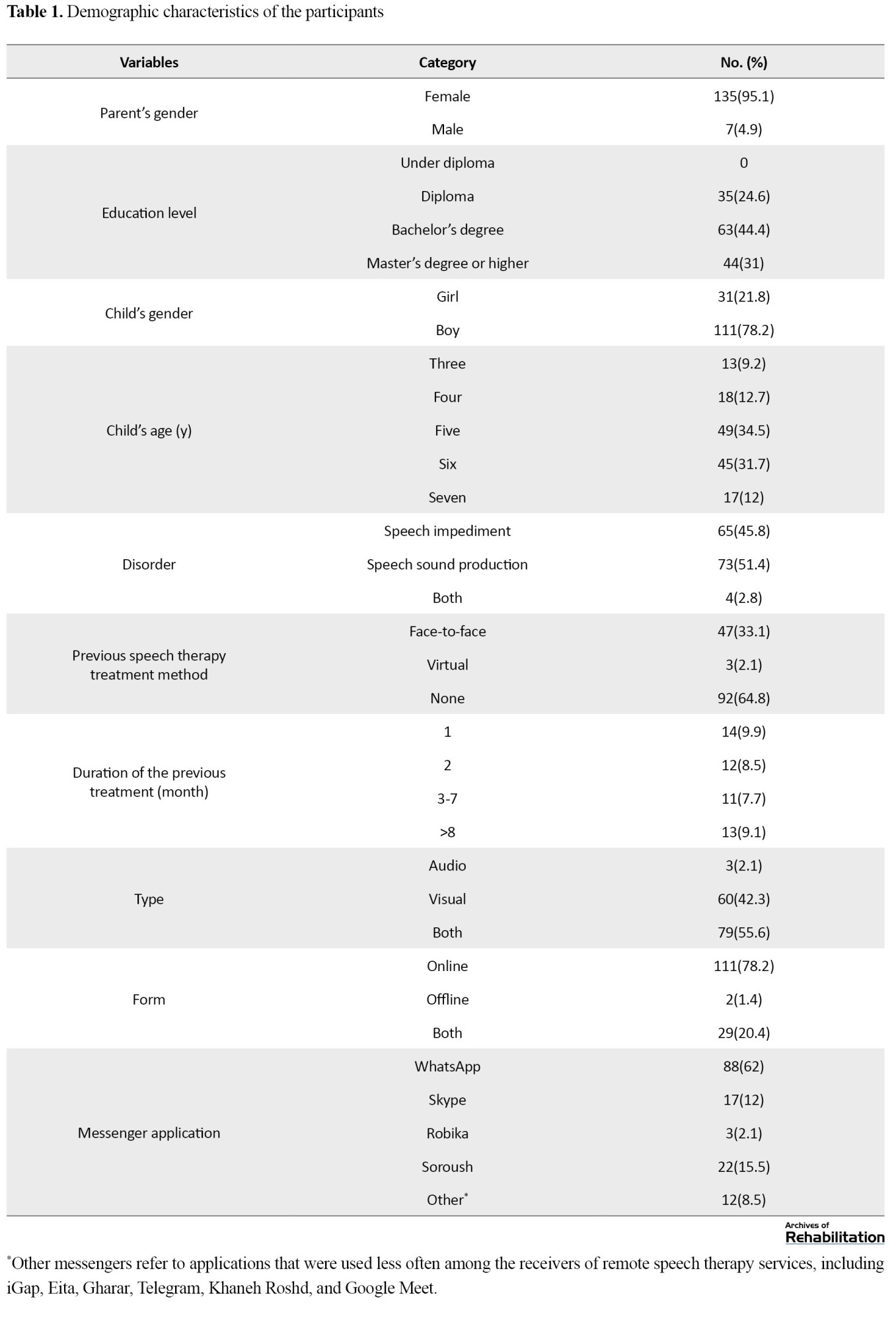

According to Table 1, 142 parents of eligible children participated in the study and completed the questionnaires.

Of them, 135(95%) were female; nearly half of them held a bachelor’s degree (n=63[44%]), and their average age was 36 years. Almost three-fourths of the families had boys (n=111[78%]) and they were mostly 5 years old (n=49[34.5%]). Further, 51% (n=73) of children living in Tehran City had speech sound production disorder. The highest frequencies of sessions considering type, form and media belonged to audio-visual (56%), online (78%), and WhatsApp (62%), respectively. Most of the participatory families had no speech therapy session before the last remote speech therapy session (n=92[65%]). Among participants who reported a history of speech therapy sessions, 94% received face-to-face treatment.

The content validity of the initial 35 items was assessed by 11 experts in speech therapy and research instrument development, and the mean CVR of the accepted items was obtained at 0.903. Six items with scores <0.059 were omitted from the questionnaire, leaving a final set of 29 items in the questionnaire.

Six items which were omitted were as follows:

My child communicated comfortably with their speech therapist. I was satisfied with my interaction/communication level with the speech therapist. I was satisfied with the level of interaction/communication my child had with the speech therapist. Remote speech therapy services satisfied the therapeutic needs of my child. Using the remote speech therapy system made us feel like we were in an in-person therapy environment. I felt dizzy or nauseous while using remote speech therapy services.

The content validity of the remaining 29 items was assessed by 10 parents of children with speech and sound production impediments who had already participated in remote speech therapy sessions. The mean CVI in the accepted items was 0.935, and 1 item with a score of less than 0.7 was removed from the questionnaire, resulting in 28 items.

The omitted items was as follows:

My eyes hurt while using the remote speech therapy service.

Regarding structural validity, this study used the principal axis factoring method with the promax rotation, yielding a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.815. Since the value is >0.7, the adequacy of the data for exploratory factor analysis was confirmed, and the results of the Bartlette test show that the items have correlations and the feasibility of conducting factor analysis (χ2=3698.59; df=378; P<0.05).

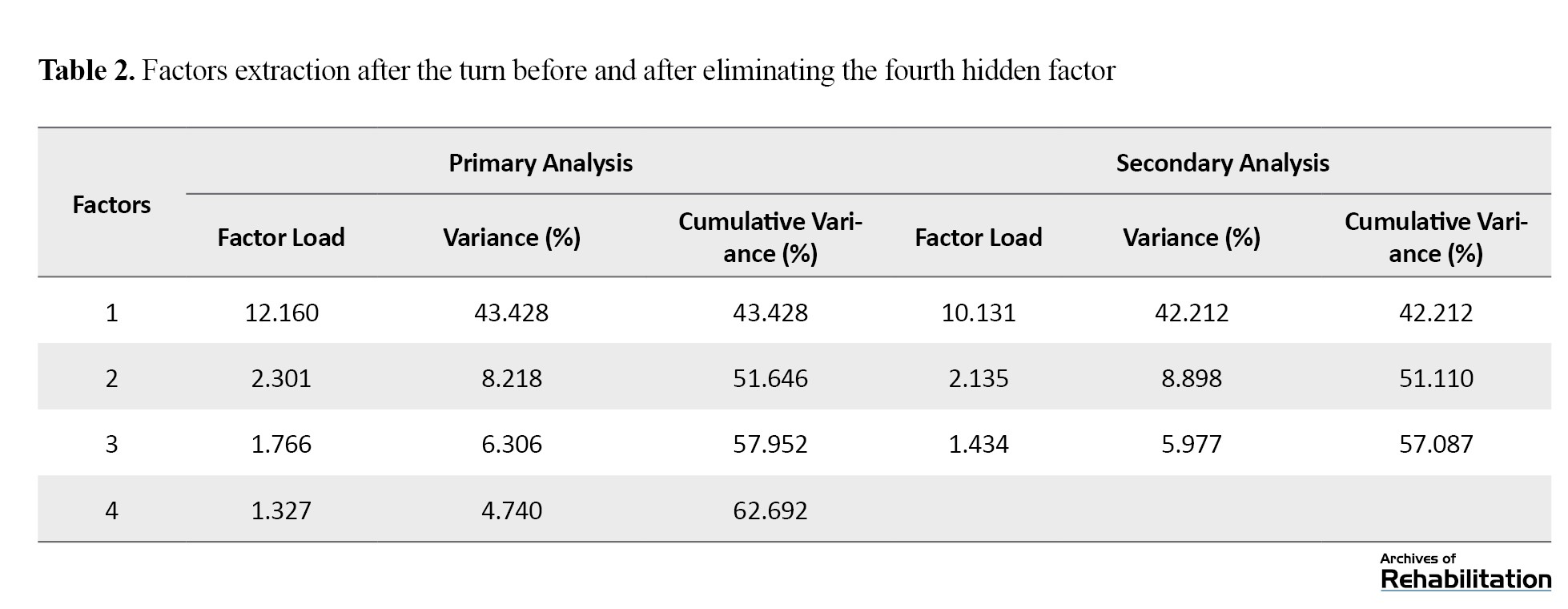

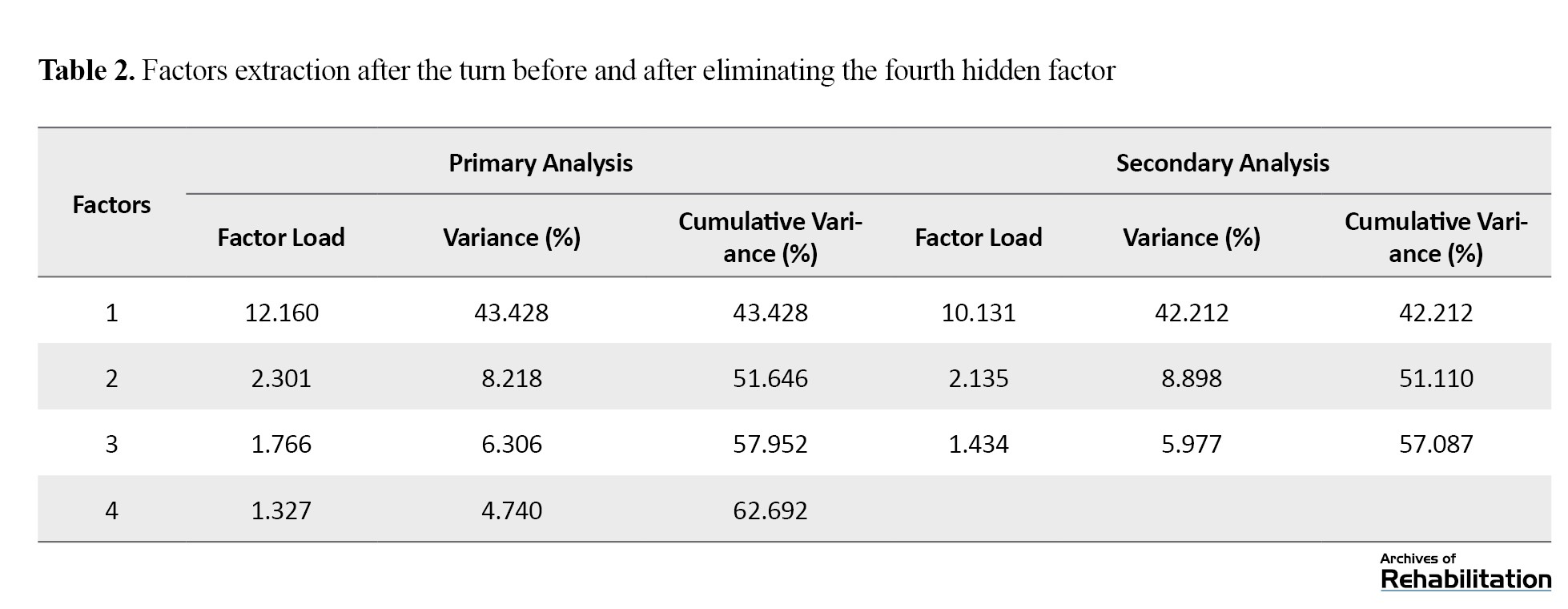

According to Table 2, four factors were initially introduced. However, the variance explained percentage by the fourth factor was <5%, resulting in the exclusion of the fourth factor, leaving 3 factors for consideration.

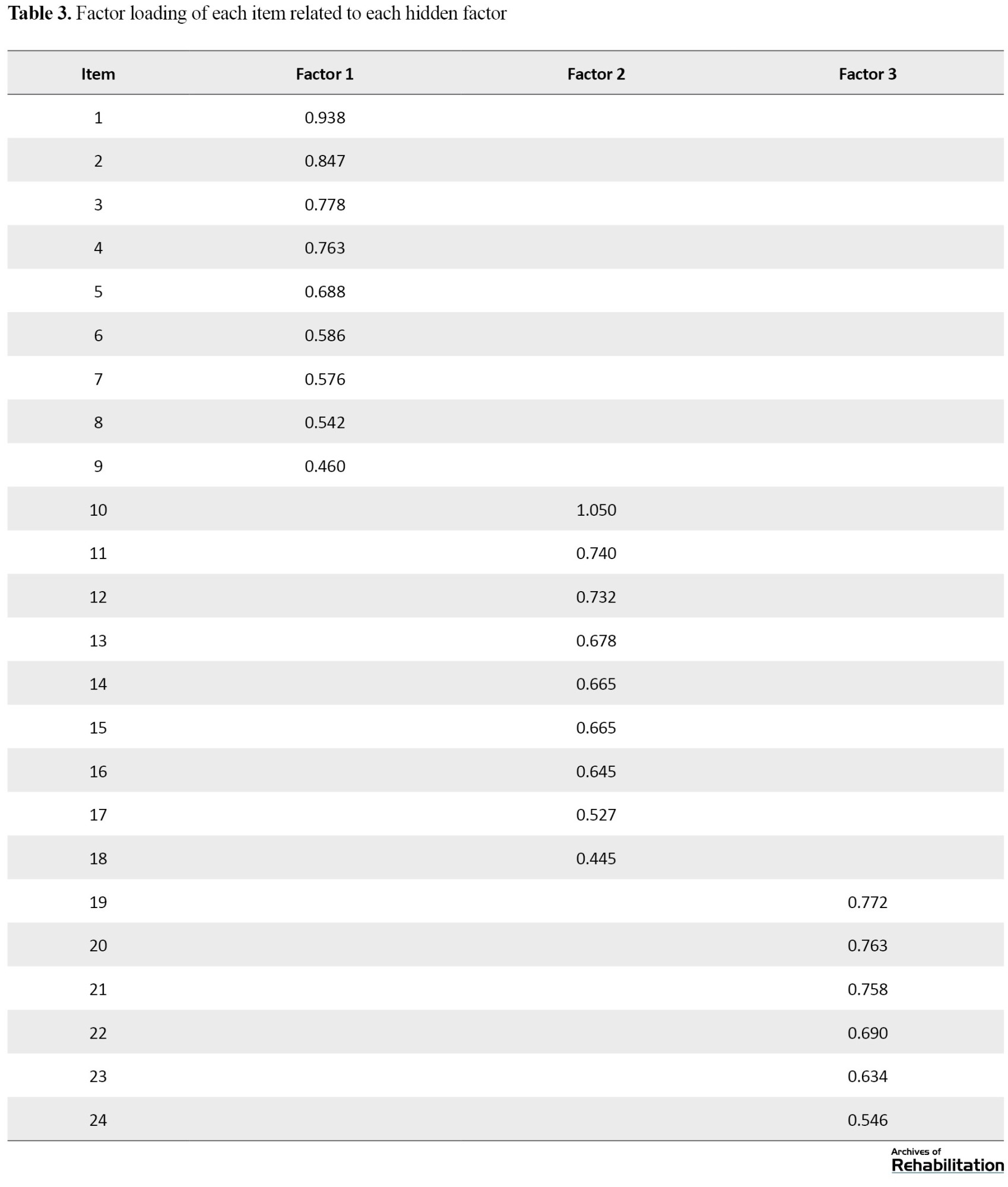

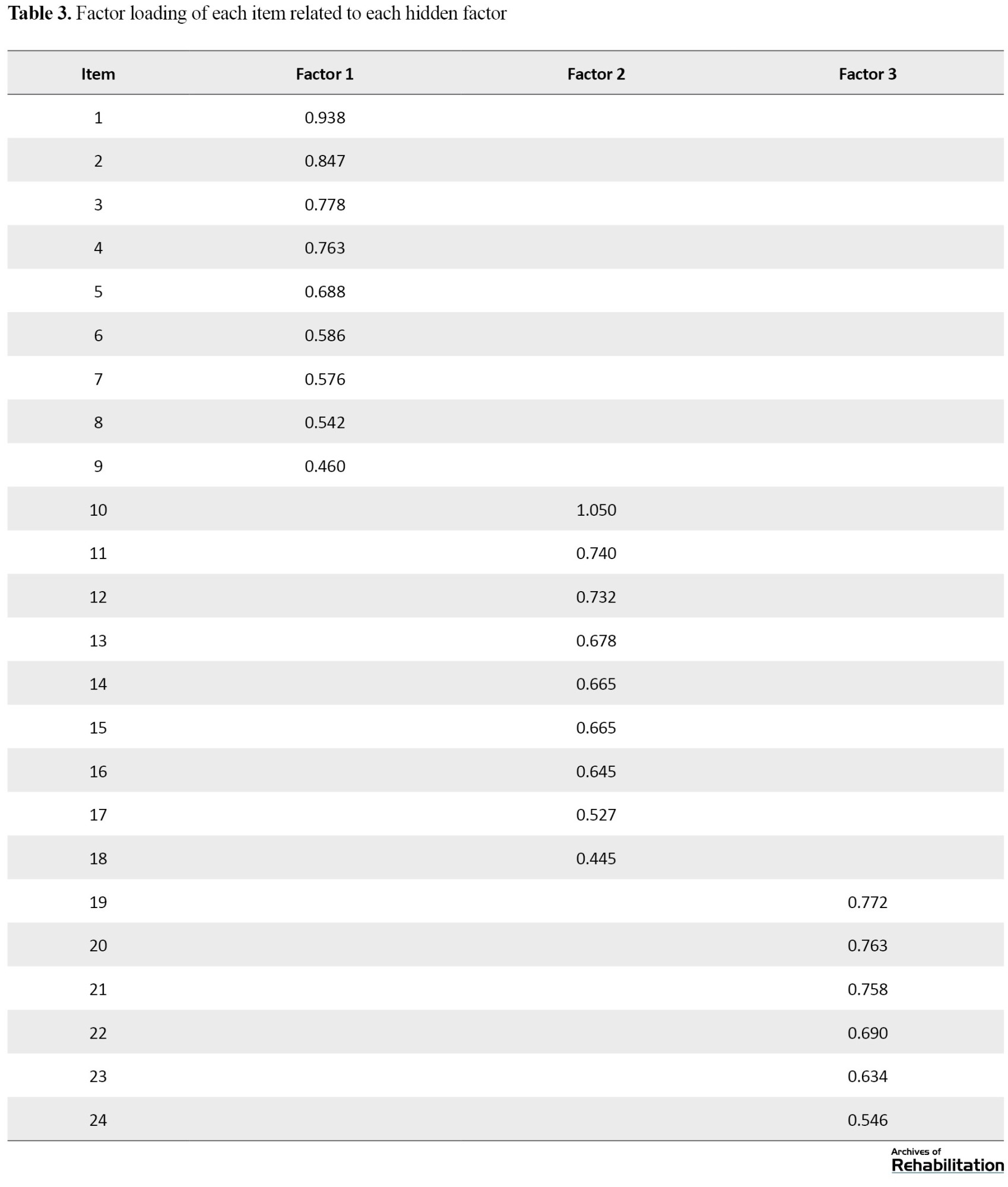

After the exploratory factor analysis of the 28 items, 4 items were removed from the questionnaire because of their cross-loading across multiple factors, and the 3 remaining factors were named as follows: efficacy, user-friendliness, therapist’s accountability, and responsiveness. The total variance percentage explained by 3 factors was around 57.1% and factor loadings of each item with the hidden factor were also calculated (Table 3).

The four omitted items were as follows:

Items 3: I felt comfortable regarding the therapist’s interaction with my child. Items 12: The speech therapist had a good grasp of my child’s development through virtual service. Items 27: My child’s attention and focus were adequate in the remote speech therapy service. Items 28: Overall, I was satisfied with the remote speech therapy service.

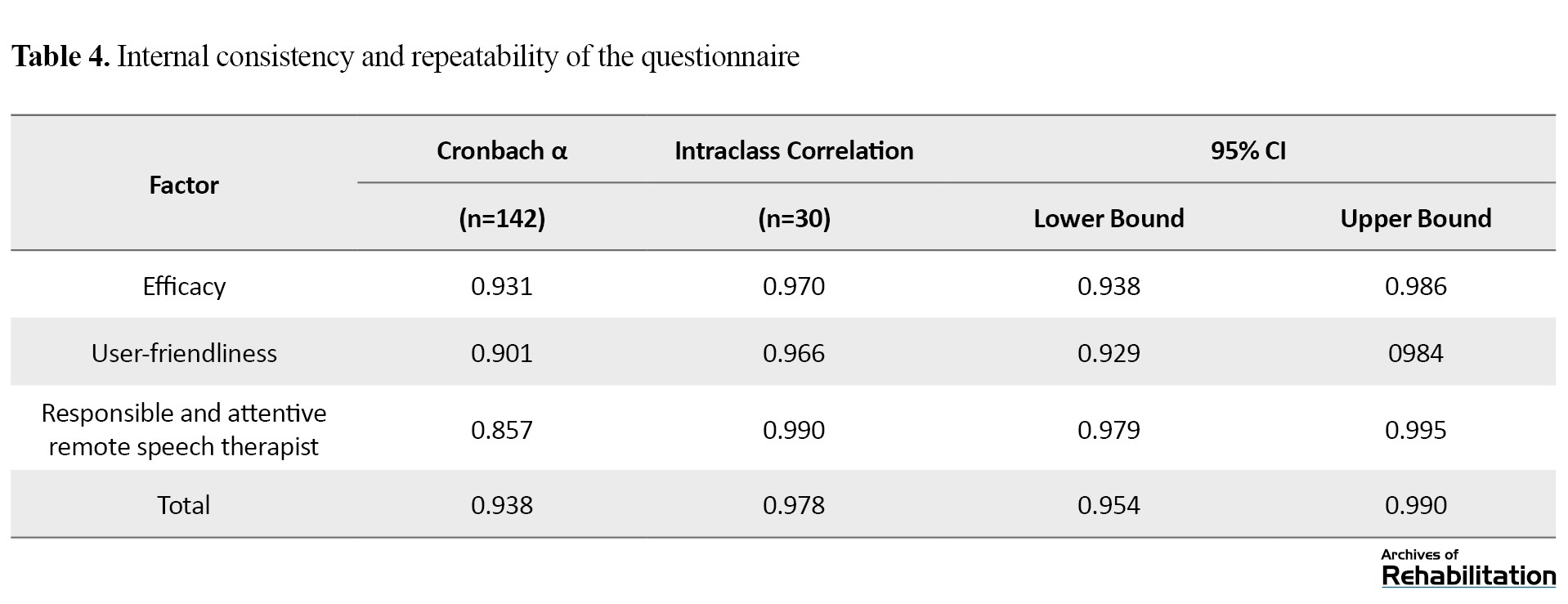

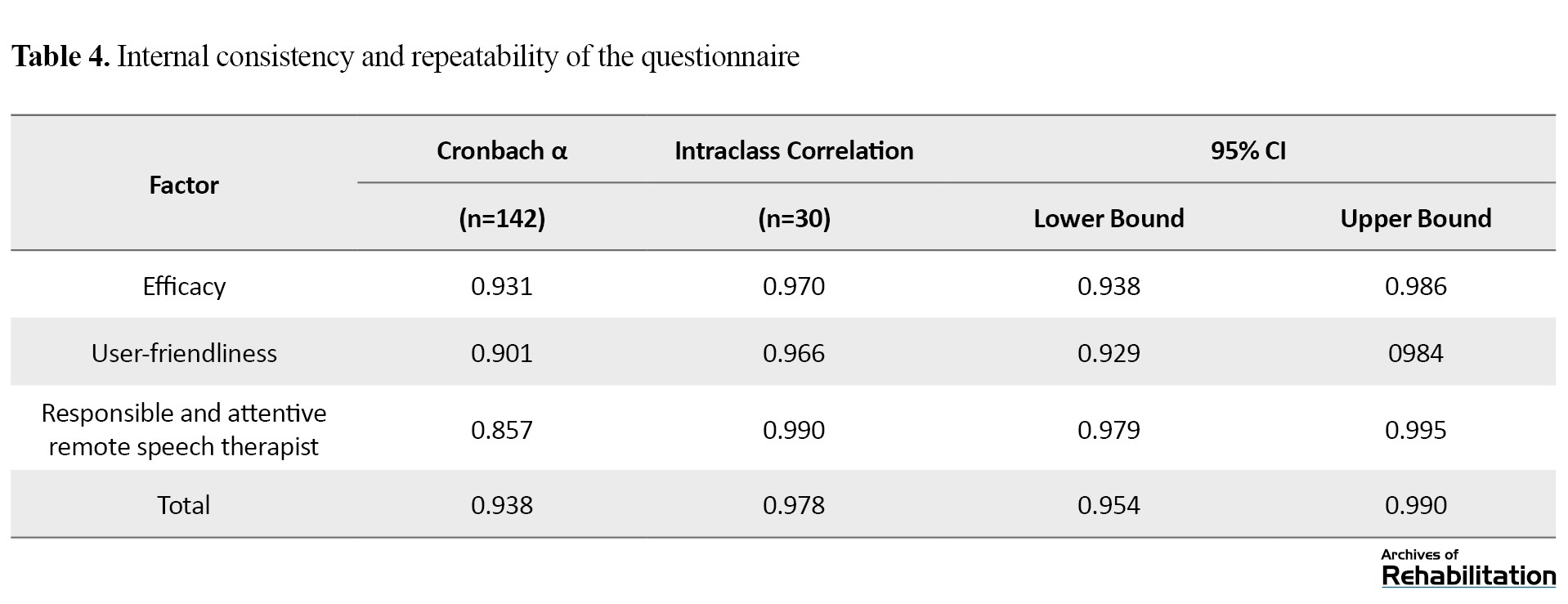

The Cronbach α coefficient of the whole questionnaire (0.938) and all three factors was >0.7, which shows the proper internal consistency of the questionnaire. Deleting any item from the questionnaire did not increase the Cronbach α coefficient. Therefore, all items remained in the questionnaire. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for the test re-test of the tool and >0.9 was obtained for all three factors and the whole questionnaire. The values >0.8 show the good reliability of the tool (Table 4).

The correlation of the items with the whole questionnaire exceeded 0.4, showing that no item needs to be removed.

Discussion

As previously mentioned, assessing parents’ satisfaction with remote speech therapy is necessary because it enables parents, researchers and experts in rehabilitation to make better decisions about treatment options based on the obtained statistics. Accordingly, a simple, reliable, and valid questionnaire is necessary, and a researcher-made questionnaire has been developed for this purpose.

The face and content validity results show that the researcher-made questionnaire is a valid tool for evaluating the satisfaction of families of children with speech and language disorders receiving the remote speech therapy service. The results align with the previous studies [26, 27]. However, Al Awaji et al. [26] only reported a CVR of 0.81 (acceptable level) and a CVI of 0.84. In the study by Yip et al. [27], content validly was assessed, but the assessment was not quantitative. In the studies by Constantinesco [28], Tenforde et al. [25], Gil-Gómez et al. [24] and another study by Gomez et al. [23], the content and face validities of the questionnaire were not evaluated. Finally, the results showed that the current research demonstrated a higher CVR than all previous studies.

The results of the structural validity in the current research were in line with previous studies [13, 27]. The current study examined structural validity via the exploratory factor analysis. The authors used the principal axis factoring with the promax rotation to determine the questionnaire’s hidden factors. In this rotation, at first, four factors were introduced. Still, the variance percentage explained by the fourth factor was <5%, resulting in its removal, and the three factors remained in the end (3 factors had a factor loading >1). The total explained variance by these three factors was nearly 57.1%. In addition, 4 items were deleted from the 28 items.

In the study of Yip et al. [27], the varimax rotation was used in the factor analysis, and 3 factors were extracted. The three selected factors explained 68% of the changes regarding the patient’s satisfaction. The questionnaire comprised 15 items and 1 question was omitted after the structural analysis.

Also, in the study by Gomez et al. [24], exploratory factor analysis and scree plot analysis were conducted. Items with particular values >1 were retained. Also, a correlation threshold correlation of an unrotated factor load >0.3 was used between the items and the factor. Since all values were >0.3, all items had good correlations with the whole scale. The above article emphasized that virtual rehabilitation systems have no applicable questionnaire or satisfaction questionnaire with valid internal consistency. Finally, in all other studies [24-26, 28], the structural validity of the questionnaire has not been evaluated.

In the current article, the Cronbach α coefficients of the whole scale (0.938) and three factors exceeded 0.7, indicating the suitable internal consistency of the scale. Deletion of any item did not enhance the Cronbach α coefficient. Therefore, all items remained in the questionnaire. The ICC value for all three factors and the whole questionnaire surpassed 0.9, with values >0.8 demonstrating the proper reliability of a scale. The correlation of the items with the whole questionnaire was >0.4, which showed no need to remove any item.

In a previous study [27], an internal consistency of 0.93 was reported (this value is almost similar to the value obtained in the current research), along with an ICC of 0.43. The authors maintained that this value is adequate considering the novelty of telemedicine. However, the ICC value was considerably lower than the value obtained in the current study. The Cronbach α coefficient of the user satisfaction evaluation questionnaire (USEQ) scale [13] was 0.716, indicating adequate internal consistency [31]. However, this value is lower than the Cronbach value coefficient obtained in the present article.

In the study of Gil-Gómez et al. [24], 13 people completed the questionnaire, which was insufficient to evaluate internal consistency properly. Nonetheless, preliminary results indicated acceptable internal consistency of suitability evaluation questionnaire (SEQ) (Cronbach α coefficient=0.7). Meanwhile, the repeatability of the questionnaire was not evaluated. In addition, the reliability of the questionnaire has not been studied in previous research on evaluating the satisfaction of families with children with speech and sound production impediments who received remote speech therapy [25, 26, 28].

In addition to the issues mentioned above, this study encountered several limitations. Firstly, considering the number of items on the questionnaire, it was difficult to reach larger samples of parents of children with speech and sound production impediments who used remote speech therapy. Also, internet disconnection was among the challenges faced in this research when therapists tried to help researchers disturbing the questionnaire link among their clients in filtered messenger applications, such as WhatsApp and Instagram. Lastly, the present study’s samples merely included 142 parents of children with speech and sound production impediments who reside in Tehran, which restricts the generalizability of the study results to other children and populations.

Conclusion

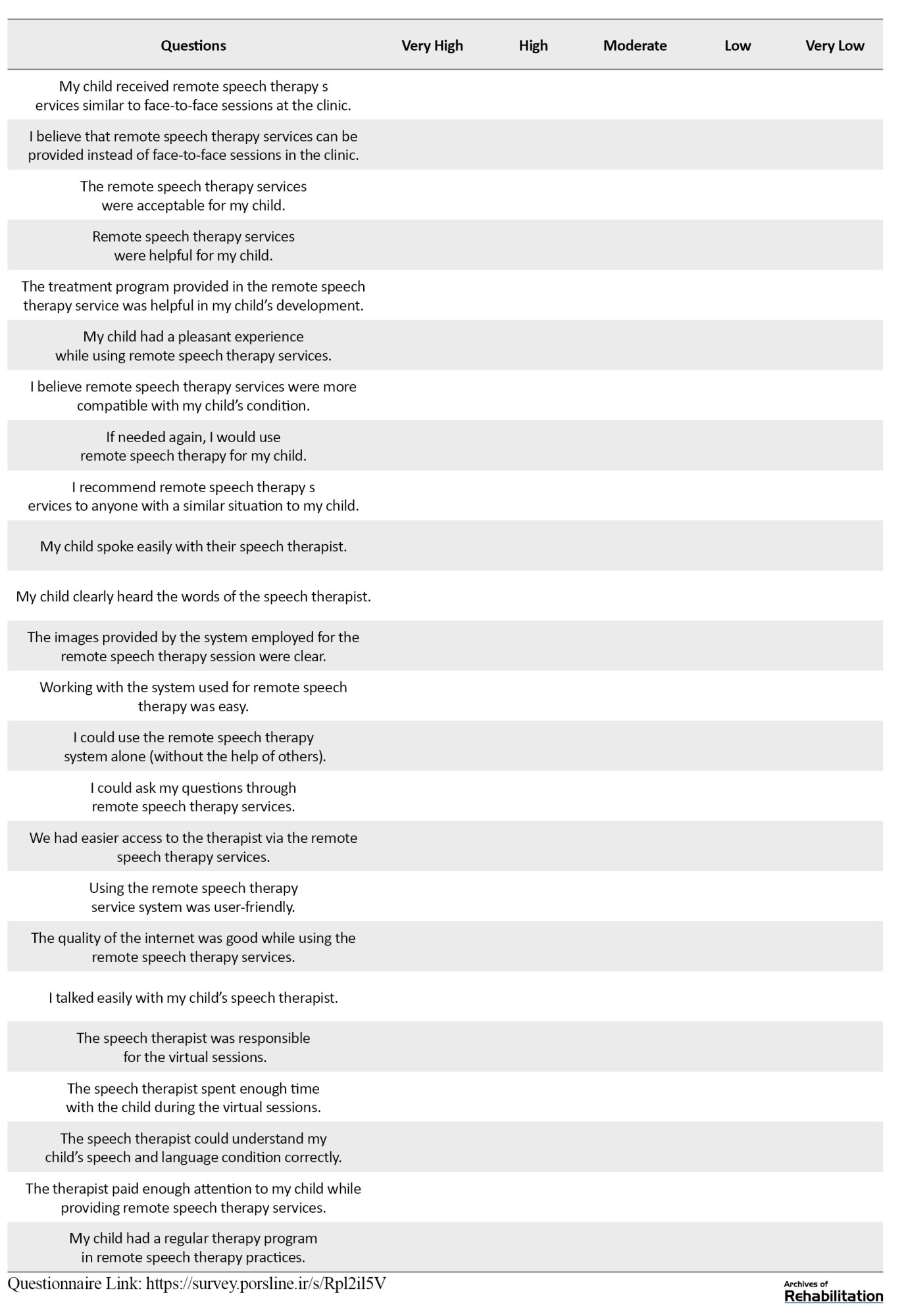

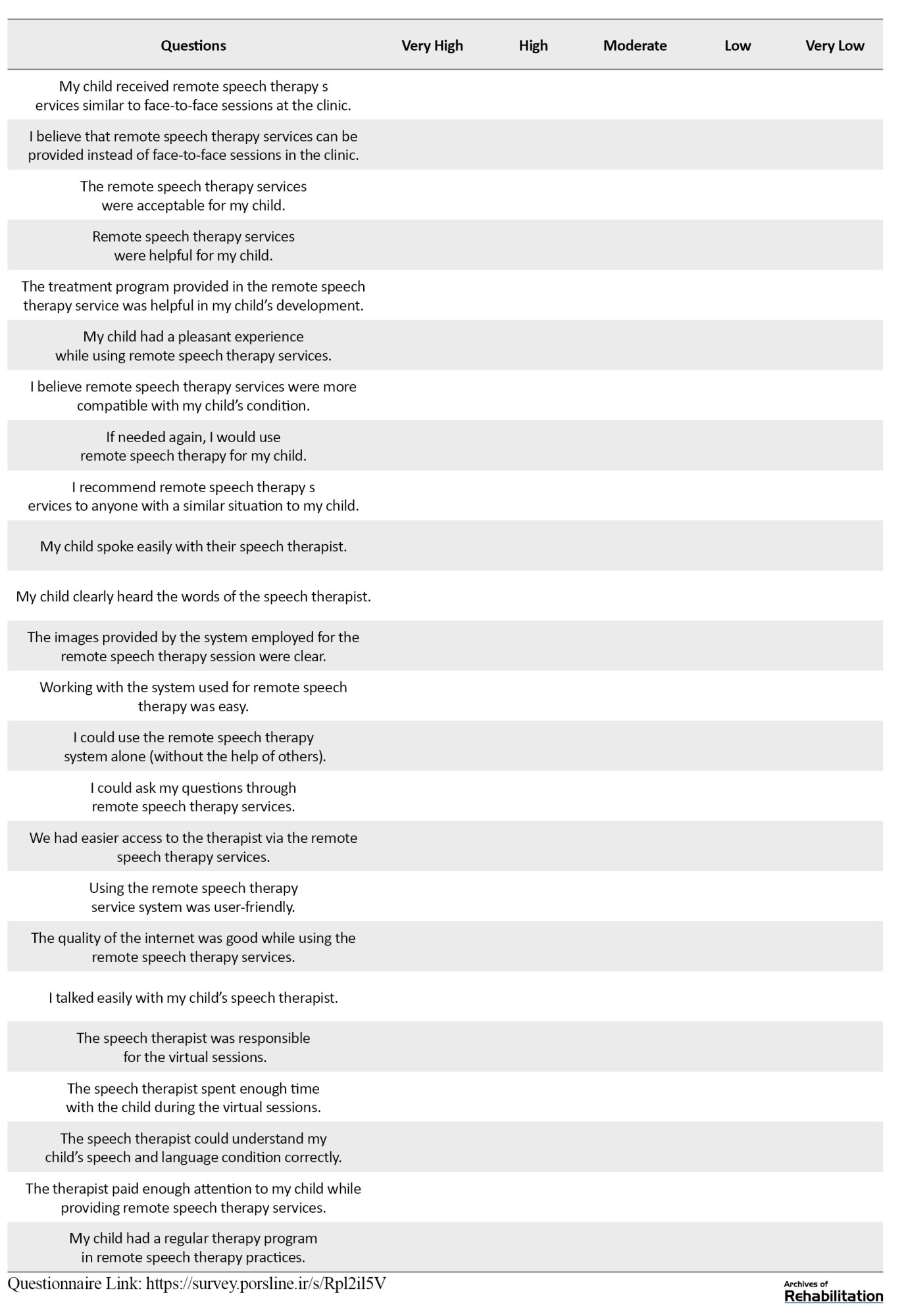

This questionnaire assessing satisfaction with remote speech therapy services among families of children with speech and sound production impediments living in Tehran consists of 24 items and 3 factors: Efficacy, user-friendliness and therapist’s accountability and responsiveness. This questionnaire stands out as one of the most comprehensive tools regarding the evaluation of the satisfaction of remote rehabilitation due to its large participant sample (n=142), accepted validity (content, face, and structural) and reliability (internal consistency and repeatability) (Appendix 1).

Appendix 1.

Final questionnaire

In the Name of God

Dear Parent,

Greetings. After the spread of COVID-19, telemedicine has increased in popularity worldwide. However, many families in Iran have remained skeptical about the effectiveness of remote speech therapy and consider it less effective compared to face-to-face speech therapy to help improve the situation of their children. Accordingly, we have decided to evaluate the satisfaction of parents of children with speech and sound production impediments who received at least 10 sessions of remote speech therapy.

Our research, titled “designing and psychometric evaluation of the satisfaction of families from remote speech therapy and its applications for children with speech and sound impediments in Tehran City, Iran,” aims to gather valuable insights to enhance remote speech therapy sessions. Therefore, we kindly ask you to complete this questionnaire carefully and help us to provide remote speech therapy services. We hope this study helps improve the quality of life and treatment of individuals with speech and sound production impediments. We are grateful in advance for your participation. After answering the last question, click the ‘send’ option to submit your answers to the therapist.

Background information

Child age; child gender: 1) Male, 2) Female; parent’s age; parent’s gender: 1) Male, 2) Female; parent’s education level: Under diploma, diploma, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree or higher; Living province: Have you ever had speech therapy (before the last remote speech therapy session)? 1) Yes, 2) No; If you answered yes, was it in-person or virtual? 1) In-person, 2) Virtual; If answered positive, for how long? What is the child’s problem? 1) Speech impediment, 2) Pronunciation problem (speech and sound production impediment), 3) Both; duration of the disorder; The type of the current remote treatment session: 1) Auditory, 2) Visual, 3) Both; The form of current remote treatment sessions: 1) Online, 2) Offline, 3) Both; remote messenger app: 1) WhatsApp, 2) Skype, 3) Robika, 4) Soroush, 5) Other; In case you use other messenger apps, please name them; The surname of the last remote speech therapist.

Speech therapists who provide remote rehabilitation can use this tool to evaluate the satisfaction of families of children with speech and sound impediments. Meanwhile, families can more accurately assess the remote speech therapy sessions. It is recommended that in future research, this subject be examined for families of children with other disorders (such as autism, speech and language delay, etc.) and with children of older ages. Also, the satisfaction from remote speech therapy services can be compared with face-to-face services, or the challenges of remote speech therapy can be examined via interviews or nominal focus groups with families using qualitative paradigms.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.127). In order to conduct the research, an informed consent form was obtained from the parents of the clients, and in order to protect the ethical principles regarding the preservation of private information and its confidentiality, the individuals were assured. The respondents were free to participate in this research and if they did not agree at any time, they could withdraw from the study.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master's thesis of Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi approved in the Department of Rehabilitation Management, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, resource, research, investigation, writing the original draft: All authors; Methodology, validation, data analysis, review and editing: Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi, Kianoosh Abdi, and Samane Hosseinzadeh; Visualization: Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi and Kianoosh Abdi; Visualization, supervision and project management: Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi and Kianoosh Abdi; Financing: Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Refrences

Telecommunication refers to the technology of transmitting signals, images, and messages over long distances via media, such as radio, telephone, television, satellite and so on. Alongside these technological advancements, human lifestyles have considerably been transformed. One of the changes is the use of technology to deliver healthcare services. In recent years, the adoption of telemedicine has increased significantly, driven by advancements in computer sciences and medical device technologies [1].

Telemedicine serves as an alternative and effective method for supervision, surveillance, standardization, and administration of healthcare services, as well as research and development in this field. Studies indicate telemedicine is cost-effective and productive in delivering healthcare services to the general population [2, 3]. Among its various benefits, studies mention the empowerment of patients and healthcare providers, improvements in delivering services, reducing the waiting time and delay in patients’ visits, reduction of hospitalization stays, improvements in the awareness of rural populations, caregivers, and families of the patients, improved accessibility and availability of crucial information, expanded educational networks, and saving in costs and resources of the patients, healthcare providers, and governments [4-7].

Telerehabilitation, as an essential subcategory of telemedicine, facilitates the delivery of rehabilitation services to rural and remote areas [4, 5, 8-16] from experts in telerehabilitation to older people and children with disabilities. Such experts include physiotherapists [16], speech and language therapists (SLTs) [17], occupational therapists [18], audiologists, physicians, rehabilitation engineers, nurses, teachers, psychologists, and nutritionists. Among the participants in this field, the non-expert individuals, such as the family and caregivers of the patients, can be mentioned [19].

Professional communities, such as the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA), American Occupational Therapy Association (AOTA), American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) and the Commission on Rehabilitation Counselor Certification (CRCC), hold various viewpoints on telerehabilitation. This method is a novel framework and each organization’s capacity to support or participate in remote activities varies [20].

Satisfaction with a service is an essential outcome, and satisfaction evaluation is regarded as a measure of effectiveness. Therefore, one crucial aspect of telerehabilitation that warrants attention is the satisfaction of families receiving such services. Overall, some studies have evaluated satisfaction, adherence, and acceptance of telerehabilitation from the viewpoint of patients, and their results support the development of this approach [21-23].

The first scientific journal on telerehabilitation was published in 1998. Since then, the number of articles on this topic has increased [1]. Based on the online databases, there is no proper questionnaire to evaluate the satisfaction of the service receiver of speech and language telerehabilitation. Given the development of technology and the spread of COVID-19, the need for such a tool became increasingly apparent. In addition, the existing questionnaires had some limitations.

Accordingly, this study aims to design and psychometrically evaluate a questionnaire assessing satisfaction with remote speech and language telerehabilitation in families with children with speech and language disorders living in Tehran City, Iran. Attempts were made to cover the essential shortcomings of previous research in designing questionnaires in this area.

Materials and Methods

Using a descriptive approach, the current research develops an instrument. The research team prepared the initial draft of the “satisfaction evaluation of families from remote speech therapy” questionnaire after translating and consolidating items in 6 questionnaires regarding the satisfaction evaluation of telemedicine in several sessions [13, 24-28]. Initially, 35 initial items were generated. Then, 11 experienced experts in the field of speech therapy and research instrument development evaluated the content validity of the questionnaire and chose for each item the following choices: “important and relevant,” “can be used, but it is not necessary” and “irrelevant.” The content validity ratio (CVR) was calculated based on these evaluations.

To evaluate the quantitative face validity, 10 parents of children with speech impediments and sound production disorders who had already participated in the remote speech therapy sessions reviewed the questionnaire. They provided their opinions on the relevance of items: “Completely relevant,” “relevant,” “somewhat relevant” and “irrelevant.” the content validity index (CVI) was calculated based on their feedback.

Considering that we had 28 items and 5 to 10 samples per item were adequate for psychometric questionnaires [29], 140 people were considered the sample size for this study (5 samples per item). Regarding the questionnaire’s structural validity, reliability, and repeatability, the samples were chosen via the available sampling from 142 parents of children with speech impediments and sound production disorders who received remote speech therapy services in Tehran City, Iran. The inclusion criteria were children under the age of 7 years, evidence of speech and impediments and sound production based on the assessment of the speech and language therapist, the active presence of at least one of the parents in the treatment sessions, and receiving remote speech and language therapy services in all sessions (to assess the satisfaction of the child, they should have received at least 10 sessions of remote speech therapy services).

The online version of the questionnaire was created in Porsline. The link was sent to families and speech therapists of children with speech impediments and sound production via social networks (Instagram, WhatsApp, Telegram, Bale, Robika, etc.). The repeatability of the questionnaire was assessed via the test re-test method by 30 people in the study sample completing the questionnaire at 2-week intervals.

The content validity of the questionnaire was assessed via CVR, and the lowest approval score of each item was 0.59, as 11 experts participated in the assessment [30]. The structural validity of the questionnaire was assessed via the exploratory factor analysis method, employing the principal axis factoring method with the promax rotation to assign the hidden factors in the questionnaire. The validity of the subscales, the whole questionnaire and the internal consistency were calculated via the Cronbach α method, and the test re-test’s repeatability was obtained by calculating the interclass correlation coefficient. Data analysis was conducted using the SPSS software, version 24.

Results

According to Table 1, 142 parents of eligible children participated in the study and completed the questionnaires.

Of them, 135(95%) were female; nearly half of them held a bachelor’s degree (n=63[44%]), and their average age was 36 years. Almost three-fourths of the families had boys (n=111[78%]) and they were mostly 5 years old (n=49[34.5%]). Further, 51% (n=73) of children living in Tehran City had speech sound production disorder. The highest frequencies of sessions considering type, form and media belonged to audio-visual (56%), online (78%), and WhatsApp (62%), respectively. Most of the participatory families had no speech therapy session before the last remote speech therapy session (n=92[65%]). Among participants who reported a history of speech therapy sessions, 94% received face-to-face treatment.

The content validity of the initial 35 items was assessed by 11 experts in speech therapy and research instrument development, and the mean CVR of the accepted items was obtained at 0.903. Six items with scores <0.059 were omitted from the questionnaire, leaving a final set of 29 items in the questionnaire.

Six items which were omitted were as follows:

My child communicated comfortably with their speech therapist. I was satisfied with my interaction/communication level with the speech therapist. I was satisfied with the level of interaction/communication my child had with the speech therapist. Remote speech therapy services satisfied the therapeutic needs of my child. Using the remote speech therapy system made us feel like we were in an in-person therapy environment. I felt dizzy or nauseous while using remote speech therapy services.

The content validity of the remaining 29 items was assessed by 10 parents of children with speech and sound production impediments who had already participated in remote speech therapy sessions. The mean CVI in the accepted items was 0.935, and 1 item with a score of less than 0.7 was removed from the questionnaire, resulting in 28 items.

The omitted items was as follows:

My eyes hurt while using the remote speech therapy service.

Regarding structural validity, this study used the principal axis factoring method with the promax rotation, yielding a Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value of 0.815. Since the value is >0.7, the adequacy of the data for exploratory factor analysis was confirmed, and the results of the Bartlette test show that the items have correlations and the feasibility of conducting factor analysis (χ2=3698.59; df=378; P<0.05).

According to Table 2, four factors were initially introduced. However, the variance explained percentage by the fourth factor was <5%, resulting in the exclusion of the fourth factor, leaving 3 factors for consideration.

After the exploratory factor analysis of the 28 items, 4 items were removed from the questionnaire because of their cross-loading across multiple factors, and the 3 remaining factors were named as follows: efficacy, user-friendliness, therapist’s accountability, and responsiveness. The total variance percentage explained by 3 factors was around 57.1% and factor loadings of each item with the hidden factor were also calculated (Table 3).

The four omitted items were as follows:

Items 3: I felt comfortable regarding the therapist’s interaction with my child. Items 12: The speech therapist had a good grasp of my child’s development through virtual service. Items 27: My child’s attention and focus were adequate in the remote speech therapy service. Items 28: Overall, I was satisfied with the remote speech therapy service.

The Cronbach α coefficient of the whole questionnaire (0.938) and all three factors was >0.7, which shows the proper internal consistency of the questionnaire. Deleting any item from the questionnaire did not increase the Cronbach α coefficient. Therefore, all items remained in the questionnaire. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated for the test re-test of the tool and >0.9 was obtained for all three factors and the whole questionnaire. The values >0.8 show the good reliability of the tool (Table 4).

The correlation of the items with the whole questionnaire exceeded 0.4, showing that no item needs to be removed.

Discussion

As previously mentioned, assessing parents’ satisfaction with remote speech therapy is necessary because it enables parents, researchers and experts in rehabilitation to make better decisions about treatment options based on the obtained statistics. Accordingly, a simple, reliable, and valid questionnaire is necessary, and a researcher-made questionnaire has been developed for this purpose.

The face and content validity results show that the researcher-made questionnaire is a valid tool for evaluating the satisfaction of families of children with speech and language disorders receiving the remote speech therapy service. The results align with the previous studies [26, 27]. However, Al Awaji et al. [26] only reported a CVR of 0.81 (acceptable level) and a CVI of 0.84. In the study by Yip et al. [27], content validly was assessed, but the assessment was not quantitative. In the studies by Constantinesco [28], Tenforde et al. [25], Gil-Gómez et al. [24] and another study by Gomez et al. [23], the content and face validities of the questionnaire were not evaluated. Finally, the results showed that the current research demonstrated a higher CVR than all previous studies.

The results of the structural validity in the current research were in line with previous studies [13, 27]. The current study examined structural validity via the exploratory factor analysis. The authors used the principal axis factoring with the promax rotation to determine the questionnaire’s hidden factors. In this rotation, at first, four factors were introduced. Still, the variance percentage explained by the fourth factor was <5%, resulting in its removal, and the three factors remained in the end (3 factors had a factor loading >1). The total explained variance by these three factors was nearly 57.1%. In addition, 4 items were deleted from the 28 items.

In the study of Yip et al. [27], the varimax rotation was used in the factor analysis, and 3 factors were extracted. The three selected factors explained 68% of the changes regarding the patient’s satisfaction. The questionnaire comprised 15 items and 1 question was omitted after the structural analysis.

Also, in the study by Gomez et al. [24], exploratory factor analysis and scree plot analysis were conducted. Items with particular values >1 were retained. Also, a correlation threshold correlation of an unrotated factor load >0.3 was used between the items and the factor. Since all values were >0.3, all items had good correlations with the whole scale. The above article emphasized that virtual rehabilitation systems have no applicable questionnaire or satisfaction questionnaire with valid internal consistency. Finally, in all other studies [24-26, 28], the structural validity of the questionnaire has not been evaluated.

In the current article, the Cronbach α coefficients of the whole scale (0.938) and three factors exceeded 0.7, indicating the suitable internal consistency of the scale. Deletion of any item did not enhance the Cronbach α coefficient. Therefore, all items remained in the questionnaire. The ICC value for all three factors and the whole questionnaire surpassed 0.9, with values >0.8 demonstrating the proper reliability of a scale. The correlation of the items with the whole questionnaire was >0.4, which showed no need to remove any item.

In a previous study [27], an internal consistency of 0.93 was reported (this value is almost similar to the value obtained in the current research), along with an ICC of 0.43. The authors maintained that this value is adequate considering the novelty of telemedicine. However, the ICC value was considerably lower than the value obtained in the current study. The Cronbach α coefficient of the user satisfaction evaluation questionnaire (USEQ) scale [13] was 0.716, indicating adequate internal consistency [31]. However, this value is lower than the Cronbach value coefficient obtained in the present article.

In the study of Gil-Gómez et al. [24], 13 people completed the questionnaire, which was insufficient to evaluate internal consistency properly. Nonetheless, preliminary results indicated acceptable internal consistency of suitability evaluation questionnaire (SEQ) (Cronbach α coefficient=0.7). Meanwhile, the repeatability of the questionnaire was not evaluated. In addition, the reliability of the questionnaire has not been studied in previous research on evaluating the satisfaction of families with children with speech and sound production impediments who received remote speech therapy [25, 26, 28].

In addition to the issues mentioned above, this study encountered several limitations. Firstly, considering the number of items on the questionnaire, it was difficult to reach larger samples of parents of children with speech and sound production impediments who used remote speech therapy. Also, internet disconnection was among the challenges faced in this research when therapists tried to help researchers disturbing the questionnaire link among their clients in filtered messenger applications, such as WhatsApp and Instagram. Lastly, the present study’s samples merely included 142 parents of children with speech and sound production impediments who reside in Tehran, which restricts the generalizability of the study results to other children and populations.

Conclusion

This questionnaire assessing satisfaction with remote speech therapy services among families of children with speech and sound production impediments living in Tehran consists of 24 items and 3 factors: Efficacy, user-friendliness and therapist’s accountability and responsiveness. This questionnaire stands out as one of the most comprehensive tools regarding the evaluation of the satisfaction of remote rehabilitation due to its large participant sample (n=142), accepted validity (content, face, and structural) and reliability (internal consistency and repeatability) (Appendix 1).

Appendix 1.

Final questionnaire

In the Name of God

Dear Parent,

Greetings. After the spread of COVID-19, telemedicine has increased in popularity worldwide. However, many families in Iran have remained skeptical about the effectiveness of remote speech therapy and consider it less effective compared to face-to-face speech therapy to help improve the situation of their children. Accordingly, we have decided to evaluate the satisfaction of parents of children with speech and sound production impediments who received at least 10 sessions of remote speech therapy.

Our research, titled “designing and psychometric evaluation of the satisfaction of families from remote speech therapy and its applications for children with speech and sound impediments in Tehran City, Iran,” aims to gather valuable insights to enhance remote speech therapy sessions. Therefore, we kindly ask you to complete this questionnaire carefully and help us to provide remote speech therapy services. We hope this study helps improve the quality of life and treatment of individuals with speech and sound production impediments. We are grateful in advance for your participation. After answering the last question, click the ‘send’ option to submit your answers to the therapist.

Background information

Child age; child gender: 1) Male, 2) Female; parent’s age; parent’s gender: 1) Male, 2) Female; parent’s education level: Under diploma, diploma, bachelor’s degree, master’s degree or higher; Living province: Have you ever had speech therapy (before the last remote speech therapy session)? 1) Yes, 2) No; If you answered yes, was it in-person or virtual? 1) In-person, 2) Virtual; If answered positive, for how long? What is the child’s problem? 1) Speech impediment, 2) Pronunciation problem (speech and sound production impediment), 3) Both; duration of the disorder; The type of the current remote treatment session: 1) Auditory, 2) Visual, 3) Both; The form of current remote treatment sessions: 1) Online, 2) Offline, 3) Both; remote messenger app: 1) WhatsApp, 2) Skype, 3) Robika, 4) Soroush, 5) Other; In case you use other messenger apps, please name them; The surname of the last remote speech therapist.

Speech therapists who provide remote rehabilitation can use this tool to evaluate the satisfaction of families of children with speech and sound impediments. Meanwhile, families can more accurately assess the remote speech therapy sessions. It is recommended that in future research, this subject be examined for families of children with other disorders (such as autism, speech and language delay, etc.) and with children of older ages. Also, the satisfaction from remote speech therapy services can be compared with face-to-face services, or the challenges of remote speech therapy can be examined via interviews or nominal focus groups with families using qualitative paradigms.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.127). In order to conduct the research, an informed consent form was obtained from the parents of the clients, and in order to protect the ethical principles regarding the preservation of private information and its confidentiality, the individuals were assured. The respondents were free to participate in this research and if they did not agree at any time, they could withdraw from the study.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the master's thesis of Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi approved in the Department of Rehabilitation Management, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, resource, research, investigation, writing the original draft: All authors; Methodology, validation, data analysis, review and editing: Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi, Kianoosh Abdi, and Samane Hosseinzadeh; Visualization: Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi and Kianoosh Abdi; Visualization, supervision and project management: Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi and Kianoosh Abdi; Financing: Shakiba Hadian Dehkordi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Refrences

- Peretti A, Amenta F, Tayebati SK, Nittari G, Mahdi SS. Telerehabilitation: Review of the state-of-the-art and areas of application. JMIR Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies. 2017; 4(2):e7. [DOI:10.2196/rehab.7511] [PMID]

- Zahid Z, Atique S, Saghir MH, Ali I, Shahid A, Malik RA. A commentary on telerehabilitation services in Pakistan: Current trends and future possibilities. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2017; 9(1):71-6. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2017.6224] [PMID]

- Cason J. A pilot telerehabilitation program: Delivering early intervention services to rural families. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2009; 1(1):29-38. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2009.6007] [PMID]

- Brennan DM, Mawson S, Brownsell S. Telerehabilitation: Enabling the remote delivery of healthcare, rehabilitation, and self management. In: Advanced technologies in rehabilitation. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2009. [Link]

- Torsney K. Advantages and disadvantages of telerehabilitation for persons with neurological disabilities. NeuroRehabilitation. 2003; 18(2):183-5. [DOI:10.3233/NRE-2003-18211] [PMID]

- Tan J. E-health care information systems: An introduction for students and professionals. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons; 2005.[Link]

- Keaton L, Pierce LL, Steiner V, Lance K, Masterson M, Rice MS, Smith JL. An E-rehabilitation team helps caregivers deal with stroke. Internet Journal of Allied Health Sciences and Practice. 2004; 2(4):1-9. [DOI:10.46743/1540-580X/2004.1057]

- Tan KK, Narayanan AS, Koh GC, Kyaw KK, Hoenig HM. Development of telerehabilitation application with designated consultation categories. Journal of Rehabilitation Research & Development. 2014; 51(9):1383-96. [DOI:10.1682/JRRD.2014.02.0052] [PMID]

- Spindler H, Leerskov K, Joensson K, Nielsen G, Andreasen JJ, Dinesen B. Conventional rehabilitation therapy versus telerehabilitation in cardiac patients: a comparison of motivation, psychological distress, and quality of life. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019; 16(3):512. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph16030512] [PMID]

- Brennan D, Tindall L, Theodoros D, Brown J, Campbell M, Christiana D, et al. A blueprint for telerehabilitation guidelines. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2010; 2(2):31-4.[DOI:10.5195/ijt.2010.6063] [PMID]

- Tsai LLY, McNamara RJ, Dennis SM, Moddel C, Alison JA, McKenzie DK, et al. Satisfaction and experience with a supervised home-based real-time videoconferencing telerehabilitation exercise program in people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2016; 8(2):27-38. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2016.6213] [PMID]

- LoPresti EF, Jinks A, Simpson RC. Consumer satisfaction with telerehabilitation service provision of alternative computer access and augmentative and alternative communication. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2015; 7(2):3-14. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2015.6180] [PMID]

- Hoaas H, Andreassen HK, Lien LA, Hjalmarsen A, Zanaboni P. Adherence and factors affecting satisfaction in long-term telerehabilitation for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A mixed methods study. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2016; 16:26. [DOI:10.1186/s12911-016-0264-9] [PMID]

- Barriga A, Conejero JM, Hernández J, Jurado E, Moguel E, Sánchez-Figueroa F. A vision-based approach for building telecare and telerehabilitation services. Sensors. 2016; 16(10):1724. [DOI:10.3390/s16101724] [PMID]

- Cassel SG, Edd AJ. A pedagogical note: Use of telepractice to link student clinicians to diverse populations. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2016; 8(1):41-8. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2016.6190] [PMID]

- Parmanto B, Saptono A. Telerehabilitation: State-of-the-art from an informatics perspective. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2009; 1(1):73-84. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2009.6015] [PMID]

- Lawford BJ, Bennell KL, Kasza J, Hinman RS. Physical therapists’ perceptions of telephone-and internet video-mediated service models for exercise management of people with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care & Research. 2018; 70(3):398-408. [DOI:10.1002/acr.23260] [PMID]

- Theodoros D. Speech-language pathology and telerehabilitation. In: Kumar S, Cohn E, editors. Telerehabilitation. Health informatics. London: Springer; 2013. [Link]

- Burrage MM. Telehealth and rehabilitation: Extending occupational therapy services to Rural Mississippi [PhD dissertation]. Mississippi: University of Southern Mississippi; 2019. [Link]

- Schmeler MR, Schein RM, McCue M, Betz K. Telerehabilitation clinical and vocational applications for assistive technology: Research, opportunities, and challenges. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2009; 1(1):59-72. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2009.6014] [PMID]

- Vatnøy TK, Thygesen E, Dale B. Telemedicine to support coping resources in home-living patients diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Patients’ experiences. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2017; 23(1):126-32. [DOI:10.1177/1357633X15626854] [PMID]

- Dinesen B, Andersen SK, Hejlesen O, Toft E. Interaction between COPD patients and healthcare professionals in a cross-sector tele-rehabilitation programme. In: Moen A, Andersen SK, Aarts J, Hurlen P, editors. User centred networked health care. Amsterdam: IOS Press; 2011. [Link]

- Gil-Gómez JA, Gil-Gómez H, Lozano-Quilis JA, Manzano-Hernández P, Albiol-Pérez S, Aula-Valero C, et al. SEQ: Suitability evaluation questionnaire for virtual rehabilitation systems. Application in a virtual rehabilitation system for balance rehabilitation. Paper presented at: Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare (PervasiveHealth), 2013 7th International Conference. May 2013; Venice, Italy. [Link]

- Gil-Gómez JA, Manzano-Hernández P, Albiol-Pérez S, Aula-Valero C, Gil-Gómez H, Lozano-Quilis JA. USEQ: A short questionnaire for satisfaction evaluation of virtual rehabilitation systems. Sensors. 2017; 17(7):1589. [DOI:10.3390/s17071589] [PMID]

- Tenforde AS, Borgstrom H, Polich G, Steere H, Davis IS, Cotton K, et al. Outpatient physical, occupational, and speech therapy synchronous telemedicine: A survey study of patient satisfaction with virtual visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2020; 99(11):977-81. [DOI:10.1097/PHM.0000000000001571] [PMID]

- Al Awaji NN, Almudaiheem AA, Mortada EM. Assessment of caregivers’ perspectives regarding speech-language services in Saudi Arabia during COVID-19. Plos One. 2021; 16(6):e0253441. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0253441] [PMID]

- Yip MP, Chang AM, Chan J, MacKenzie AE. Development of the Telemedicine Satisfaction Questionnaire to evaluate patient satisfaction with telemedicine: A preliminary study. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2003; 9(1):46-50. [DOI:10.1258/135763303321159693] [PMID]

- Constantinescu G. Satisfaction with telemedicine for teaching listening and spoken language to children with hearing loss. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2012; 18(5):267-72. [DOI:10.1258/jtt.2012.111208] [PMID]

- Newman DA. Missing data: Five practical guidelines. Organizational Research Methods. 2014; 17(4):372-411. [DOI:10.1177/1094428114548590]

- Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Personnel Psychology. 1975; 28(4):563-75. [DOI:10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x]

- Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951; 16:297-334. [DOI:10.1007/BF02310555]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Rehabilitation Management

Received: 18/01/2023 | Accepted: 24/07/2023 | Published: 1/10/2024

Received: 18/01/2023 | Accepted: 24/07/2023 | Published: 1/10/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |