Volume 24, Issue 1 (Spring 2023)

jrehab 2023, 24(1): 2-27 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khakbaz H, Khanjani M S, Younesi S J, Khodaie Ardakani M R, Safi M H, Hosseinzadeh S. Effectiveness of Cognitive-behavioral Therapy on the Positive and Negative Psychotic Symptoms and Emotion Regulation of Patients With Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders. jrehab 2023; 24 (1) :2-27

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3158-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3158-en.html

Hamid Khakbaz1

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani1

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani1

, Seyyed Jallal Younesi *2

, Seyyed Jallal Younesi *2

, Mohammad Reza Khodaie Ardakani3

, Mohammad Reza Khodaie Ardakani3

, Mohammad Hadi Safi4

, Mohammad Hadi Safi4

, Samaneh Hosseinzadeh5

, Samaneh Hosseinzadeh5

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani1

, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani1

, Seyyed Jallal Younesi *2

, Seyyed Jallal Younesi *2

, Mohammad Reza Khodaie Ardakani3

, Mohammad Reza Khodaie Ardakani3

, Mohammad Hadi Safi4

, Mohammad Hadi Safi4

, Samaneh Hosseinzadeh5

, Samaneh Hosseinzadeh5

1- Department of Counselling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Counselling

2- Department of Counselling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,ja.younesi@uswr.ac.ir

3- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Psychosis Research, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of psychiatry

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Science, University of Ardakan, Ardakan, Iran., Department of psychology

5- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., department of biostatistics

2- Department of Counselling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Psychosis Research, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of psychiatry

4- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Science, University of Ardakan, Ardakan, Iran., Department of psychology

5- Department of Biostatistics, Faculty of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., department of biostatistics

Keywords: Cognitive-behavioral therapy, Schizophrenia, Positive and negative symptoms, Emotion regulation

Full-Text [PDF 3718 kb]

(2279 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4886 Views)

Full-Text: (3088 Views)

Introduction

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders are characterized by positive and negative symptoms [1] and defects in emotional regulation [2]. Schizophrenia is the most debilitating psychiatric disorder and is resistant to psychotherapy [3]. The disease accounts for 25% to 38% of hospitalizations in psychiatric centers [4]. The prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Iran varies from 0.05% to 0.89% according to diagnostic criteria [5], but other studies report its prevalence as 1% [6].

In treating schizophrenia, although drugs are prescribed for positive psychotic symptoms, many treatments are not available for negative psychotic symptoms. Despite progress in treating schizophrenia, negative symptoms have remained an unmet therapeutic need [7], which causes patients to become functionally disabled [8]. Antipsychotic drugs significantly reduce the severity and recurrence of symptoms but have minimal effects on negative symptoms, cognitive impairment, or social functioning [9]. One of the problems and weaknesses of drug use is that patients continue to experience psychotic symptoms [10], which increases their stress levels and prevents them from performing daily functions [11]. Various treatments, such as social skills training, cognitive modification, cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychological principles training, supportive counseling [12], family therapy, and group therapy [13], exist for people with psychosis. Still, meta-analyses have shown that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most effective psychological interventions for those with schizophrenia spectrum disorders [14, 15]. It has been suggested as a psychosocial treatment for patients [16, 17]. This treatment is effective in reducing psychotic symptoms and disabilities related to psychotic disorders, reducing the number of hospitalizations [18], reducing stress, improving coping strategies, and increasing the quality of life (QoL) of intervention patients [19].

Although using CBT for psychosis has good research support, it is faced with contradictory findings in various fields in improving positive and negative psychotic symptoms, reducing the recurrence of symptoms, reducing the re-hospitalization of patients, and improving their mental status [13, 20, 21, 22]. Also, based on the results of a study, the effect size obtained from effectiveness studies cannot be generalized to different clinical environments or different populations [23]. Therefore, the use of CBT for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in the inpatient departments of psychiatric hospitals should be used with caution and if necessary [24]. Considering the contradictory findings of the research on the effectiveness of CBT for people with schizophrenia in samples from different cultures and the recurrence of symptoms in the follow-up phase, it is required to implement the protocol of CBT in the native culture of Iran with different patients, including the patients in the psychiatric department of a hospital and paying attention to their needs and problems when using CBT as a complement to psychological treatment covers the weaknesses of drug treatment of schizophrenia patients and reduces the treatment costs of patients and their families. This study was conducted to investigate the effectiveness of CBT on positive and negative psychotic symptoms and emotional regulation of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders as a single-subject study.

Materials and Methods

Research design

The experimental design of the present study was single-subject type AB with follow-up. The statistical population comprised all patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders admitted from December to March 2020 in Razi Psychiatry Educational, Therapeutic and Research Center in Tehran City, Iran. At first, 30 patients were selected by convenience sampling to enter the research. Then, 10 patients were excluded from the study according to the exclusion criteria. Among the remaining 20 participants, 5 participants (three men and two women, age range of 32 to 43 years) were randomly assigned to CBT. The inclusion criteria included patients diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, relative control of acute symptoms of patients, the average age of 18 to 45 years, a minimum education with a diploma, patients who have been hospitalized at least one week, obtaining scores higher than 90 in the scale of positive and negative psychotic symptoms and obtaining scores higher than 120 in the scale of emotional regulation difficulties. The exclusion criteria by referring to the psychiatric file of the patients included having criminal and judicial problems, alcohol or drug addiction, neurological disorders, high levels of disturbed behavior, or high risk of suicide or murder.

Measuring tools

Positive and negative symptom scale (PANSS)

This scale was created in 1986 by Kay, Fisbein, and Oppler [25] to measure the severity of positive and negative psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. It has 30 questions and 5 subscales: negative symptoms (8 questions), positive symptoms (6 questions), dissociation (7 questions), agitation (4 questions), and anxiety and depression (5 questions). The alpha coefficients of the original version of the positive and negative symptoms scale were reported as 73% and 83% for the subscales of positive and negative symptoms, respectively, and 79% for the subscales related to general pathology. Due to the determination of structural validity, a significant inverse relationship was observed between the score of positive and negative scales (R=23%) [25]. The Cronbach alpha of this scale has been obtained in Iran at 80% [26] and 77%, and its validity has been reported as acceptable using factor analysis [27, 28].

Difficulty in emotion regulation scale (DERS)

Gratz and Roemer (2004) [29] developed the “difficulty in emotion regulation scale” (DERS) and reported its reliability based on test-retest as 88% and internal consistency based on the Cronbach alpha as 93%. The final version of DERS has 36 items and 6 subscales that evaluate multiple aspects of emotional dysregulation. The subscales include non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulty engaging in purposeful behavior, difficulty in impulse control, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity [29]. Asgari et al. reported the reliability of the Persian version of this scale as 86% and 80% [30] based on the Cronbach alpha and Tasneef method [30], respectively, and Mazloum et al. reported the Cronbach alpha coefficient as 85% [31].

Study intervention

The protocol was adapted from the handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Psychotic Symptoms, which was developed and authored at the Australian Center for Clinical Interventions (CCI) by Smith, Nathan, Juniper, Kingsap, and Lim [32]. It provides clinical treatments, training, and applied and clinical training programs for professionals. The main topics of CBT in the sessions included the logical basis of therapy, assessment of psychotic symptoms of patients, commitment to follow-up treatment, training of psychological principles, cognitive therapy for hallucinations and delusions, training of behavioral skills, planning for self-management, training of problem-solving skills, and relaxation training.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software, version 16 and Excel 2013 applyed for Statistical analysis. The obtained data were analyzed by visual analysis of the data graph, indices of non-overlap of all pairs (NAP), percentage of non-overlapping data (PND), percentage of all non-overlapping data (PAND), percentage of data points exceeding the median (PEM), Cohen’s d effect size and analysis improvement percentage. Ferguson (2009) reported values of 0.41, 1.1, and 2.7 for low, medium, and high effects, respectively, in single-subject designs [33].

Results

Description and characteristics of the participants

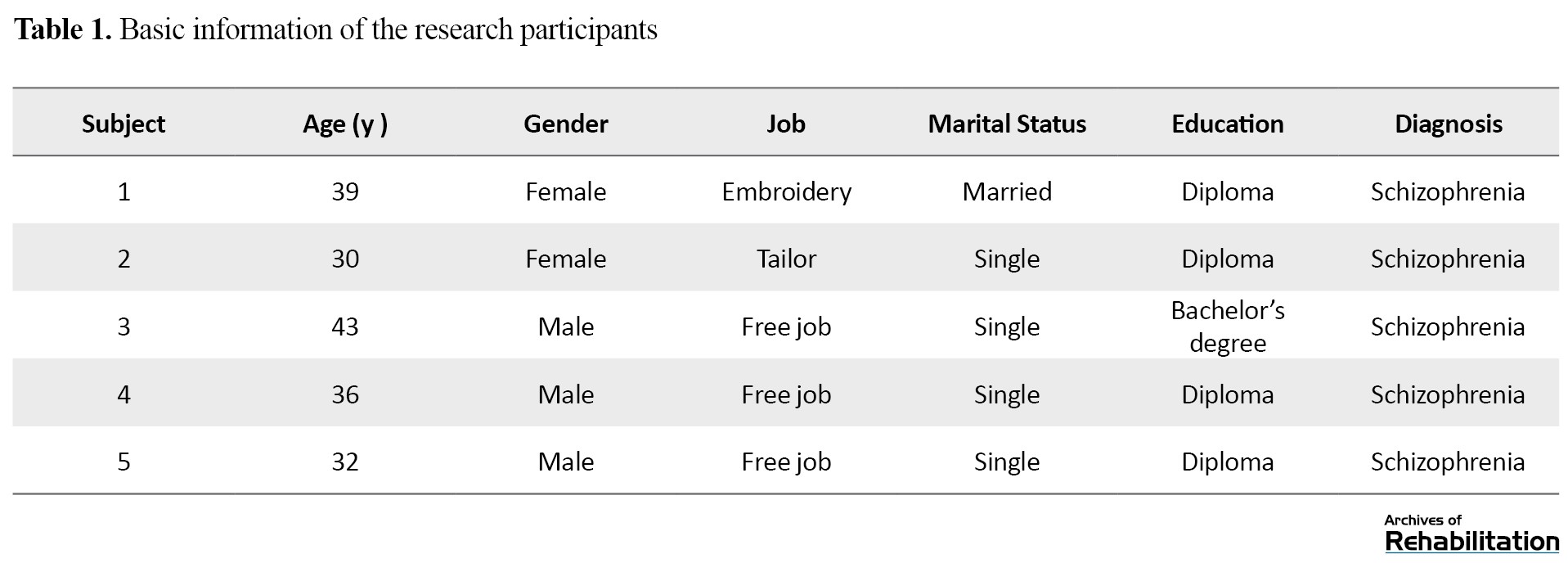

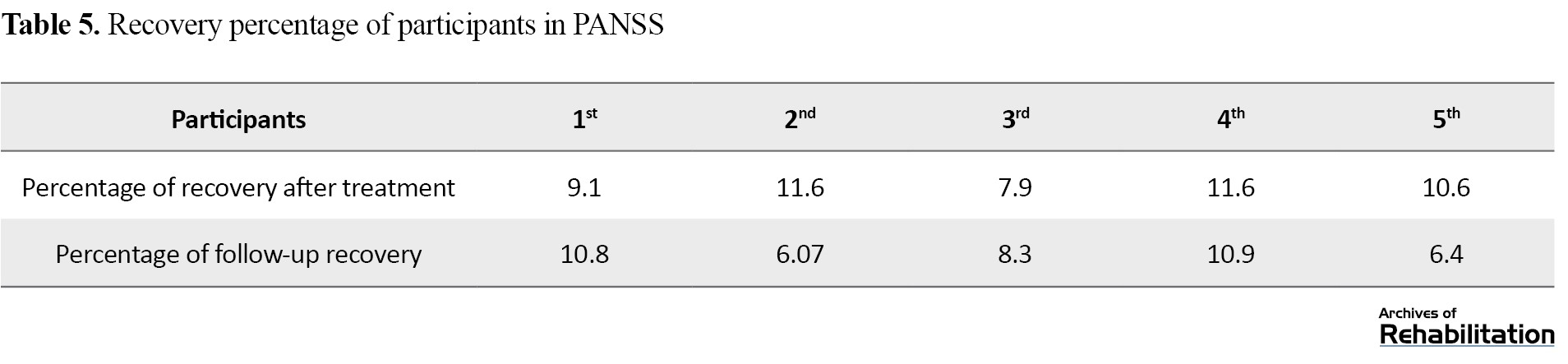

In this study, 5 patients with an average age of 36 and a standard deviation of 5.2 years participated in cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 1).

Table 2 presents the difference in Mean±SD and median of the total scores of the PANSS and the DERS.

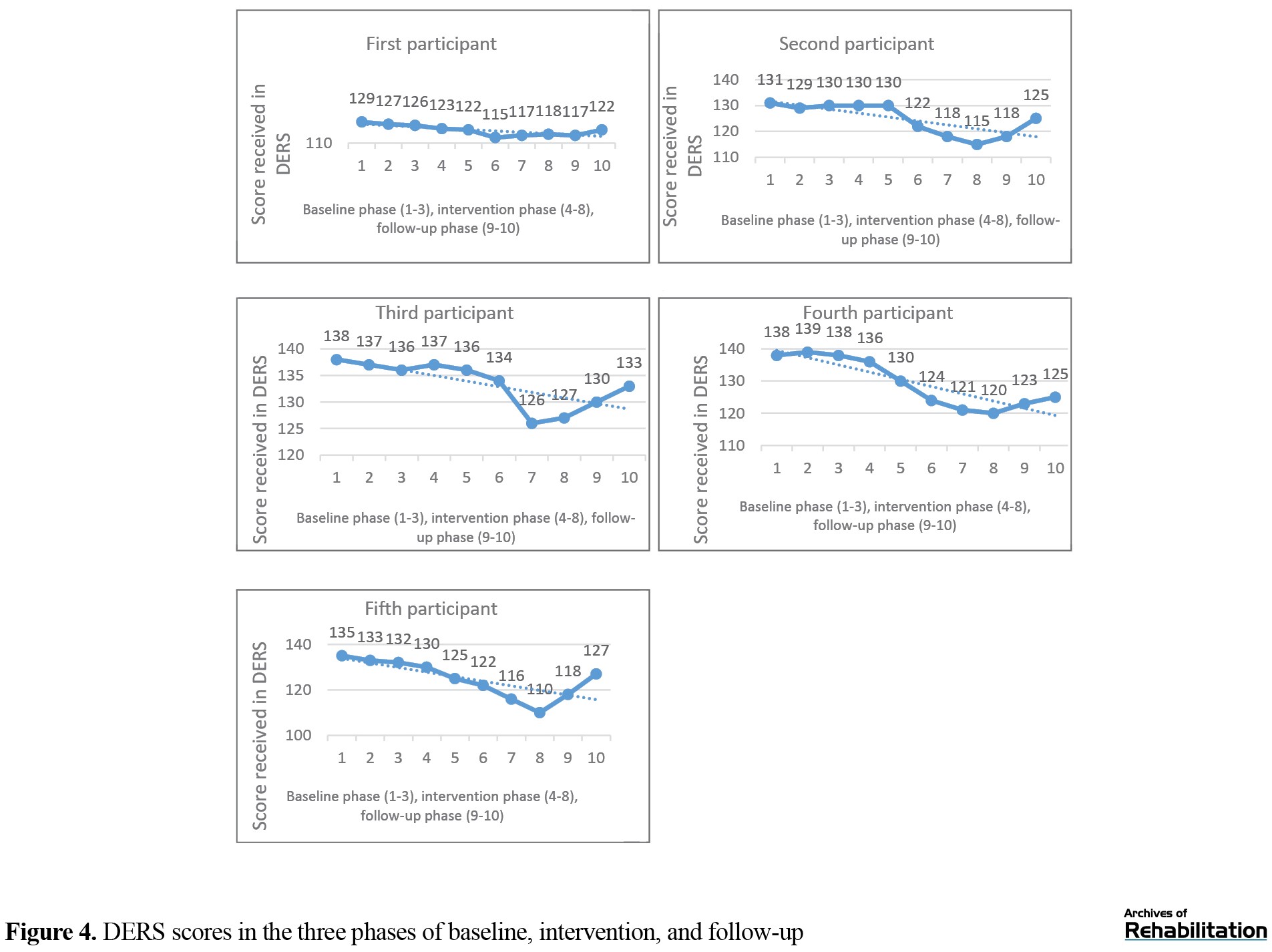

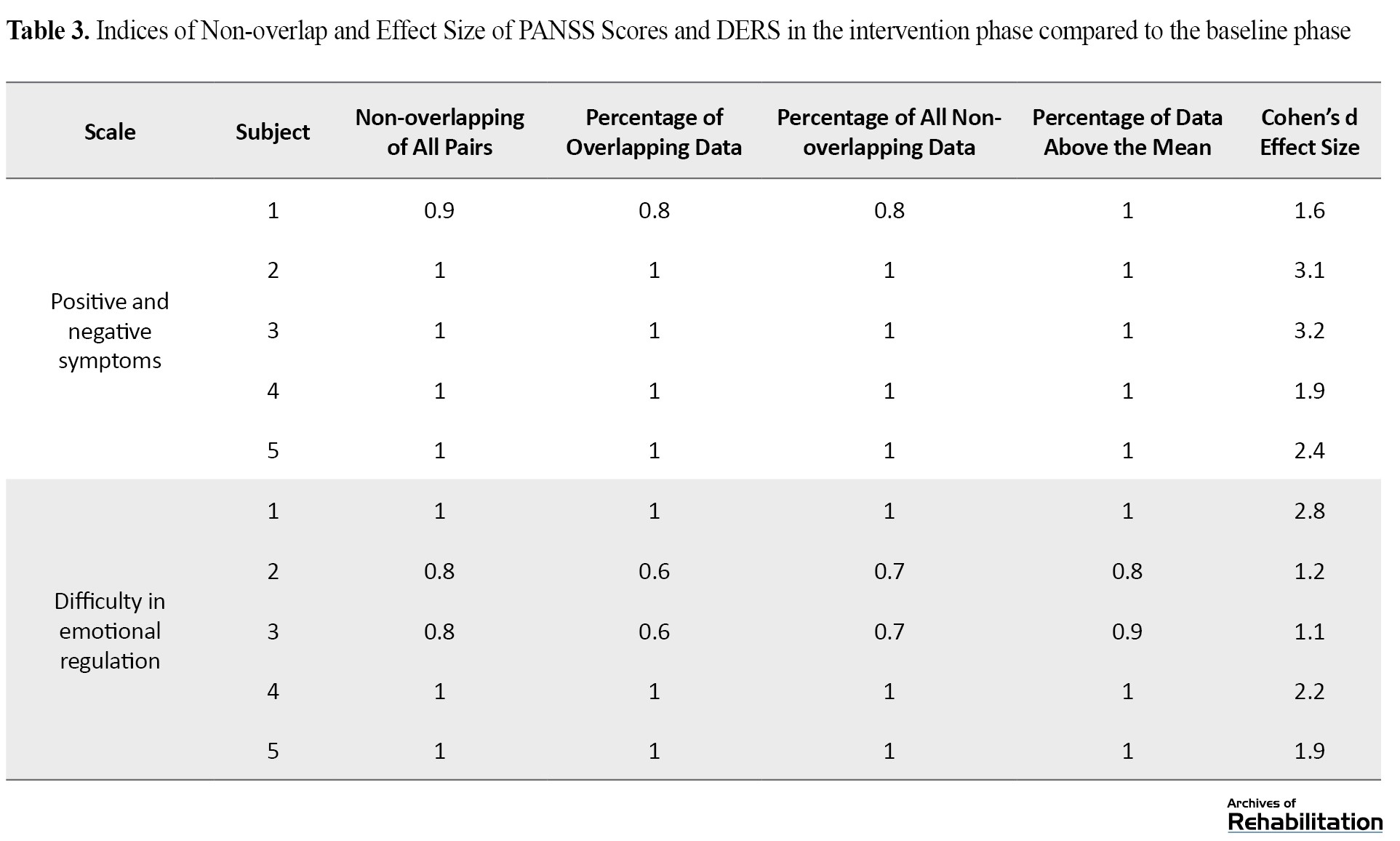

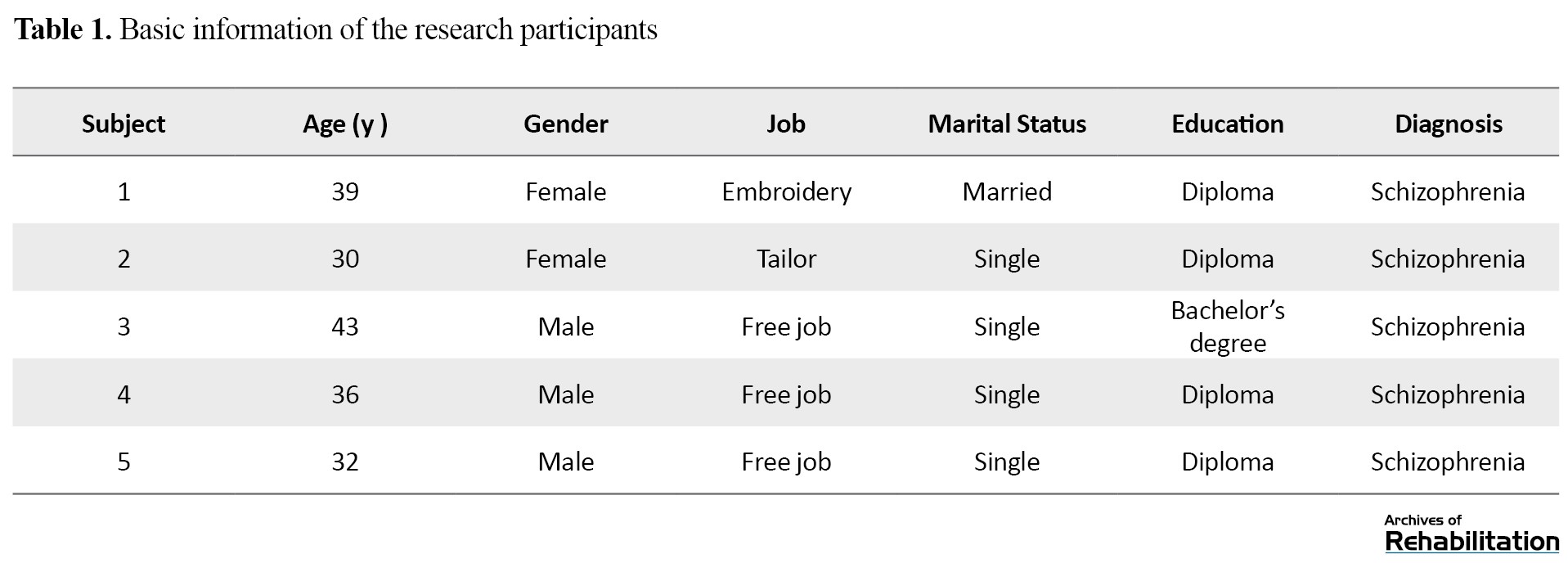

As seen in Table 2, the average scores of the PANSS and DERS for all subjects in the two phases of intervention and follow-up decreased compared to the baseline. The reduced total score of the scale indicates a decrease in the score of the subscales of positive and negative symptoms. On the other hand, the increased total score of the scale shows an increase in the score of the subscales of positive and negative symptoms. The trial can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. According to Figures 3 and 4, the slope of the trend line in all participants is small and downward, which indicates a decrease in the scores of PANSS and DERS and the formation of small changes, which means that the change occurred with a small amount and speed. According to Table 3, Cohen’s d effect size and non-overlapping indices in the second and third participants in the PANSS and the first participant in the DERS have large values showing a lot of non-overlapping, meaning a large effect size of the intervention.

The effect size in other participants (except the third participant in the DERS) in both scales shows average values, which indicates the average non-overlapping in the intervention phase compared to the baseline phase.

In Table 4, the percentage of overlapping data in all subjects in both scales is 0.0, which shows the percentage of points in the follow-up phase and states that the downward trend in the follow-up phase has not continued like the intervention phase and the scores of these two scales in the follow-up phase are higher.

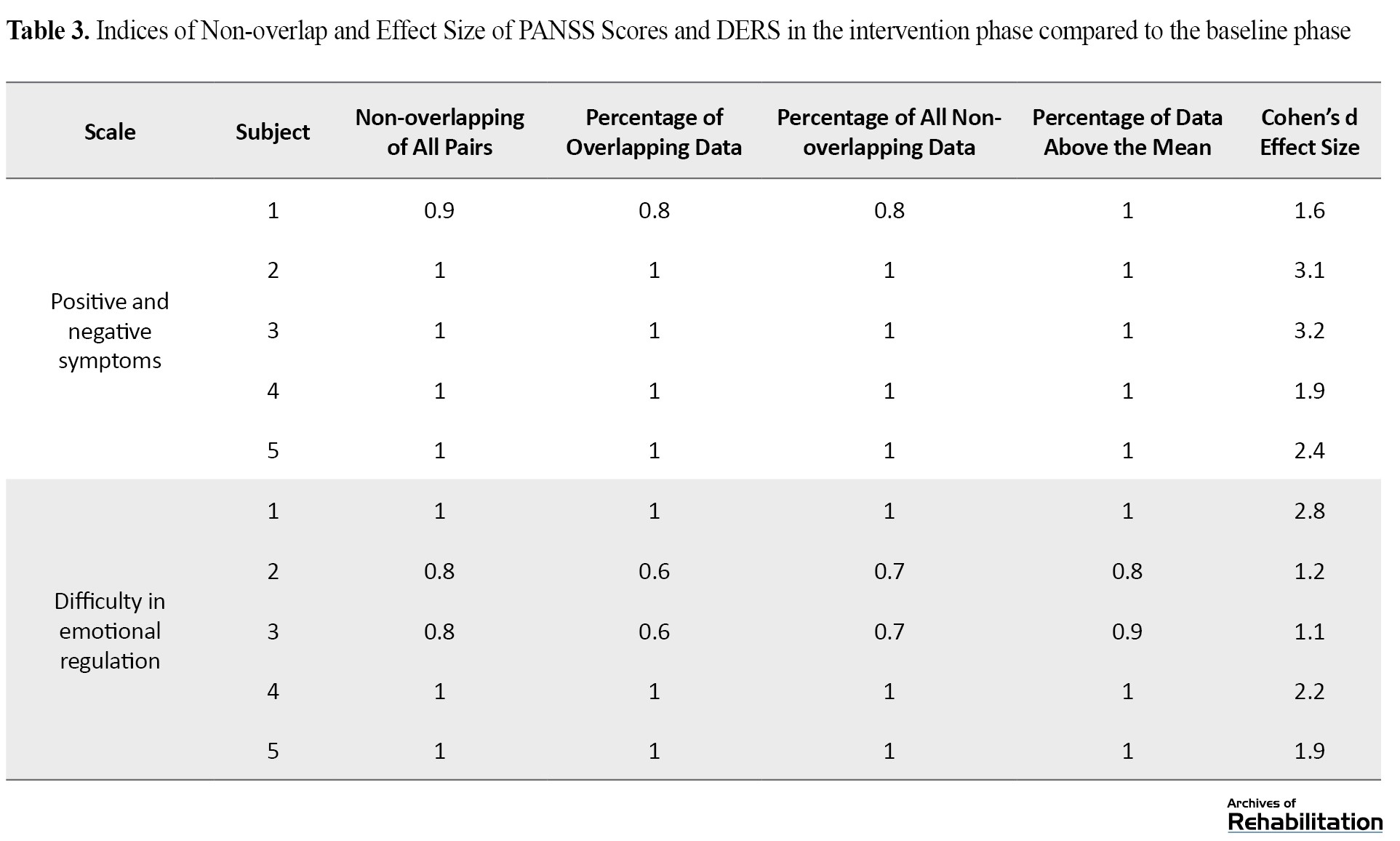

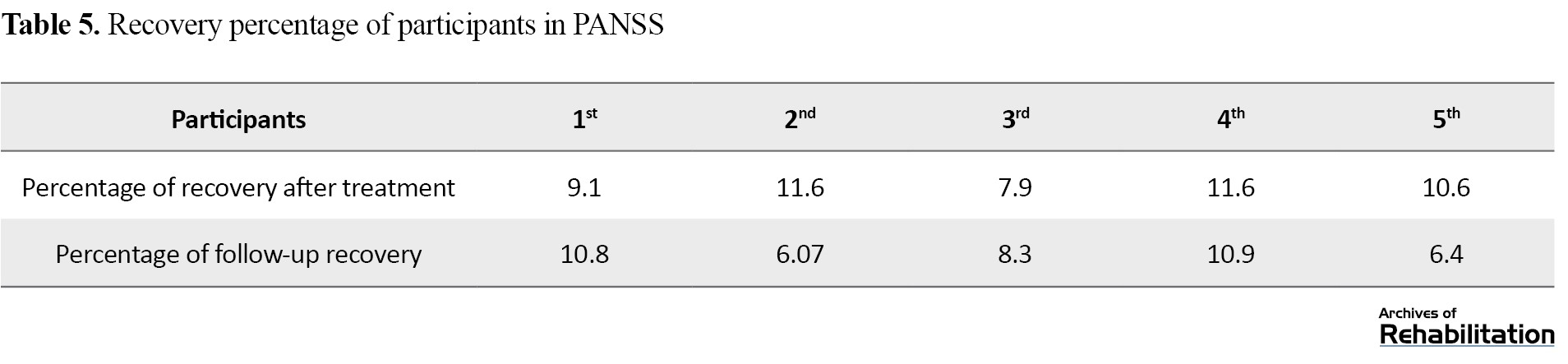

Therefore, a slight overlapping exists. The other three indicators show small, medium, and high values, respectively, indicating a low, medium, and high overlap in the follow-up phase compared to the intervention phase. Also, the effect size of Cohen’s d in all participants in the two scales has a small effect size (except for the second participant in the PANSS, which has a medium effect size), and this means that the intervention in the follow-up phase has a small effect size compared to the intervention. In addition, according to the small number of samples in the current research design, the recovery percentage was also used to evaluate the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy [34].

Considering the results obtained in Tables 5 and 6, although CBT effectively reduces positive and negative symptoms and improves emotional regulation, their effect size is not clinically significant.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) on positive and negative symptoms and emotional regulation in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. This research was conducted as a single-subject study in the educational, therapeutic, and research center of psychiatry in Tehran City. The results showed the effectiveness of CBT in reducing positive and negative symptoms and improving emotional regulation. However, the results were not clinically significant. In explaining this result, it can be said that according to the relationship between strong therapeutic cooperation and high effectiveness of treatment [35], it seems that one of the reasons for the low effectiveness of treatment is the lack of strong therapeutic cooperation between the therapist and the patients, the patients resisted solving their problems, and this issue contributed to the effectiveness of the treatment. Perhaps this factor has also caused a little focus on stress and fears related to psychotic symptoms and emotional regulation difficulties of patients, which has played a role in forming negative emotional experiences, such as anxiety and stress, and psychotic symptoms. On the other hand, since schizophrenic patients have weaknesses in monitoring resources and problems [36], they may not perform the therapeutic tasks of the sessions well. This factor has also had a negative effect on them the effectiveness of the treatment.

The decrease in the amount of positive and negative symptoms and difficulty in emotional regulation of the participants shows that the results are consistent with the research findings of Silva et al. [22] and Krakovik et al. [21]. According to Krakovik [21], lack of sufficient motivation of patients in doing therapy tasks and dealing with psychotic symptoms played a crucial role in the low effectiveness of treatment. Also, more focus on intervention sessions on cognitive reconstruction and challenges with beliefs and voices and less focus on intervention sessions on the relationship between the patient and psychotic symptoms may be vital in the low effectiveness of the treatment.

Considering the relationship between CBT and improving emotional regulation [37], CBT can effectively reduce patients’ anxiety by improving emotional regulation. This strategy can be effective in reducing positive and negative psychotic symptoms. Since people with psychosis show cognitive distortions, the goal of cognitive-behavioral therapy is to change dysfunctional thoughts and replace them with more realistic and compatible thoughts, which results in reducing the person’s involvement with their delusions and, as a result, improving emotional regulation and consequently reducing positive and negative symptoms [15]. Therefore, according to the emphasis of CBT experts [38], through cognitive restructuring, providing alternative coping cards, questioning delusional beliefs, re-evaluating one’s experiences and creating alternative strategies, normalization techniques to reduce negative emotions related to positive and negative symptoms, examining the evidence, and relaxation techniques, CBT reduces the anxiety and negative emotions of the patients and plays an effective role in reducing the positive and negative symptoms and improving the emotional regulation. However, these therapeutic consequences are not permanent, and even after two months of follow-up, the results showed that the patient’s symptoms recurred. Another possible interpretation is that due to the weakness of patients with schizophrenia in using coping strategies [35], they cannot replace ineffective coping strategies with efficient coping strategies in the long term, which could be due to patients’ poor self-monitoring. On the other hand, according to the relationship between emotional dysregulation and patients’ reluctance to talk more about their symptoms [22, 39], patients could not use cognitive behavioral therapy to treat their problems by not expressing their full and sufficient opinion about their emotions and problems, and this can be another reason for the low effectiveness of the treatment.

The trend changes in the graphs showed that the participants experienced psychotic symptoms after the treatment and follow-up phase. Therefore, according to the relationship between emotion regulation and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia [2], CBT reduces the problems related to emotional regulation by reducing patients’ anxiety. In the same way, it has affected patients’ positive and negative symptoms. Also, according to the effect size of Cohen’s d and the percentage of recovery, it can be said that these results are consistent with the findings of the research of Lincoln et al. [37] shows that by correcting beliefs and challenging automatic thoughts, problems caused by emotional regulation of psychopaths can be reduced.

Considering the average effect size of Cohen’s d and the low percentage of recovery, the findings of the present study are consistent with the research results of Weeks et al. [40]. Also, the findings of the research of Naeem et al. [41] show that patients who experience acute psychotic symptoms respond more to CBT. Therefore, the average effect size index in the participants means that although the participants in CBT in decreasing positive and negative symptoms have improved slightly, this effect was not significant, and subjects continued to experience psychotic symptoms along with emotional dysregulation even after treatment.

The findings of Naeem et al.’s research [42] showed that after receiving CBT, patients with schizophrenia showed significant improvement in all measures of psychological damage in the PANSS. They noted that there might be pressure on participants to recover early due to financial poverty in third-world countries, which is a motivation. In these countries, people with schizophrenia usually have little information about non-pharmacological treatment services. Still, by receiving cognitive-behavioral treatment, they gain insight into their disease, which is effective in their treatment [43, 44]. These results are consistent with the present study on the moderate effect size of CBT on psychotic symptoms.

The most critical limitation of the present study was that due to the COVID-19 epidemic, the sampling and implementation of the trial were carried out with strict adherence to health protocols. The small sample size was another limitation of the present study, and if the sample size had been larger, it would have been possible to generalize the results. Also, the findings of this research cannot be generalized to the entire society, so it is suggested to conduct the research with a larger sample size and in a wider geographical area to include a larger population of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Unique and focused treatment on each patient, collaboration with other therapists (such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, nurse, and social worker), and starting treatment after drug stabilization were the strengths of this study.

Conclusion

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is effective in reducing positive and negative psychotic symptoms and improving the emotional regulation of patients with schizophrenia. Still, the data obtained from Cohen’s d effect size and improvement indices showed that the findings are not clinically significant. According to the above results, cognitive-behavioral therapy should be used cautiously as adjunctive therapy in psychiatric centers.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.UWSR.REC.1399.013). Also, the current research was registered in the Clinical Trial Center of Iran under the registration No. IRCT20210412050937N2 on December 14, 2021. The study was conducted at Razi Psychiatry Educational, Therapeutic and Research Center in Tehran City. Written consent was obtained from the participants and their legal guardians to participate in the research. All patients participated in the study with the permission of their legal guardians, and no coercion existed to convince the participants of the study. They had the right to withdraw from the research at any time. Also, the patients and their legal guardians were told that all information would remain confidential and no one would disclose it unless the patient and their guardian requested it. Efforts were made to avoid harming the patients.

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD thesis of Hamid Khakbazin in Rehabilitation Counseling Training Department of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and writing the draft: Hamid Khakbaz, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Seyed Jalal Younisi; Methodology and validation: Hamid Khakbaz and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Analysis: Hamid Khakbaz, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Research and review: Hamid Khakbaz, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Seyed Jalal Younisi, Mohdreza Khodayi Ardakani, Mohammad Hadi Safi, and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Sources: Hamid Khakbaz; Edited and finalized: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Seyed Jalal Younisi, Mohammad Reza Khodayi Ardakani, and Mohammad Hadi Safi; Supervision: Seyed Jalal Younisi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to staff and officials of the Razi Educational and Therapeutic Psychiatric Center, who prepared the groundwork for this research.

References

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders are characterized by positive and negative symptoms [1] and defects in emotional regulation [2]. Schizophrenia is the most debilitating psychiatric disorder and is resistant to psychotherapy [3]. The disease accounts for 25% to 38% of hospitalizations in psychiatric centers [4]. The prevalence of schizophrenia spectrum disorders in Iran varies from 0.05% to 0.89% according to diagnostic criteria [5], but other studies report its prevalence as 1% [6].

In treating schizophrenia, although drugs are prescribed for positive psychotic symptoms, many treatments are not available for negative psychotic symptoms. Despite progress in treating schizophrenia, negative symptoms have remained an unmet therapeutic need [7], which causes patients to become functionally disabled [8]. Antipsychotic drugs significantly reduce the severity and recurrence of symptoms but have minimal effects on negative symptoms, cognitive impairment, or social functioning [9]. One of the problems and weaknesses of drug use is that patients continue to experience psychotic symptoms [10], which increases their stress levels and prevents them from performing daily functions [11]. Various treatments, such as social skills training, cognitive modification, cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychological principles training, supportive counseling [12], family therapy, and group therapy [13], exist for people with psychosis. Still, meta-analyses have shown that cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is one of the most effective psychological interventions for those with schizophrenia spectrum disorders [14, 15]. It has been suggested as a psychosocial treatment for patients [16, 17]. This treatment is effective in reducing psychotic symptoms and disabilities related to psychotic disorders, reducing the number of hospitalizations [18], reducing stress, improving coping strategies, and increasing the quality of life (QoL) of intervention patients [19].

Although using CBT for psychosis has good research support, it is faced with contradictory findings in various fields in improving positive and negative psychotic symptoms, reducing the recurrence of symptoms, reducing the re-hospitalization of patients, and improving their mental status [13, 20, 21, 22]. Also, based on the results of a study, the effect size obtained from effectiveness studies cannot be generalized to different clinical environments or different populations [23]. Therefore, the use of CBT for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders in the inpatient departments of psychiatric hospitals should be used with caution and if necessary [24]. Considering the contradictory findings of the research on the effectiveness of CBT for people with schizophrenia in samples from different cultures and the recurrence of symptoms in the follow-up phase, it is required to implement the protocol of CBT in the native culture of Iran with different patients, including the patients in the psychiatric department of a hospital and paying attention to their needs and problems when using CBT as a complement to psychological treatment covers the weaknesses of drug treatment of schizophrenia patients and reduces the treatment costs of patients and their families. This study was conducted to investigate the effectiveness of CBT on positive and negative psychotic symptoms and emotional regulation of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders as a single-subject study.

Materials and Methods

Research design

The experimental design of the present study was single-subject type AB with follow-up. The statistical population comprised all patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders admitted from December to March 2020 in Razi Psychiatry Educational, Therapeutic and Research Center in Tehran City, Iran. At first, 30 patients were selected by convenience sampling to enter the research. Then, 10 patients were excluded from the study according to the exclusion criteria. Among the remaining 20 participants, 5 participants (three men and two women, age range of 32 to 43 years) were randomly assigned to CBT. The inclusion criteria included patients diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, relative control of acute symptoms of patients, the average age of 18 to 45 years, a minimum education with a diploma, patients who have been hospitalized at least one week, obtaining scores higher than 90 in the scale of positive and negative psychotic symptoms and obtaining scores higher than 120 in the scale of emotional regulation difficulties. The exclusion criteria by referring to the psychiatric file of the patients included having criminal and judicial problems, alcohol or drug addiction, neurological disorders, high levels of disturbed behavior, or high risk of suicide or murder.

Measuring tools

Positive and negative symptom scale (PANSS)

This scale was created in 1986 by Kay, Fisbein, and Oppler [25] to measure the severity of positive and negative psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia. It has 30 questions and 5 subscales: negative symptoms (8 questions), positive symptoms (6 questions), dissociation (7 questions), agitation (4 questions), and anxiety and depression (5 questions). The alpha coefficients of the original version of the positive and negative symptoms scale were reported as 73% and 83% for the subscales of positive and negative symptoms, respectively, and 79% for the subscales related to general pathology. Due to the determination of structural validity, a significant inverse relationship was observed between the score of positive and negative scales (R=23%) [25]. The Cronbach alpha of this scale has been obtained in Iran at 80% [26] and 77%, and its validity has been reported as acceptable using factor analysis [27, 28].

Difficulty in emotion regulation scale (DERS)

Gratz and Roemer (2004) [29] developed the “difficulty in emotion regulation scale” (DERS) and reported its reliability based on test-retest as 88% and internal consistency based on the Cronbach alpha as 93%. The final version of DERS has 36 items and 6 subscales that evaluate multiple aspects of emotional dysregulation. The subscales include non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulty engaging in purposeful behavior, difficulty in impulse control, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity [29]. Asgari et al. reported the reliability of the Persian version of this scale as 86% and 80% [30] based on the Cronbach alpha and Tasneef method [30], respectively, and Mazloum et al. reported the Cronbach alpha coefficient as 85% [31].

Study intervention

The protocol was adapted from the handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for Psychotic Symptoms, which was developed and authored at the Australian Center for Clinical Interventions (CCI) by Smith, Nathan, Juniper, Kingsap, and Lim [32]. It provides clinical treatments, training, and applied and clinical training programs for professionals. The main topics of CBT in the sessions included the logical basis of therapy, assessment of psychotic symptoms of patients, commitment to follow-up treatment, training of psychological principles, cognitive therapy for hallucinations and delusions, training of behavioral skills, planning for self-management, training of problem-solving skills, and relaxation training.

Statistical analysis

SPSS software, version 16 and Excel 2013 applyed for Statistical analysis. The obtained data were analyzed by visual analysis of the data graph, indices of non-overlap of all pairs (NAP), percentage of non-overlapping data (PND), percentage of all non-overlapping data (PAND), percentage of data points exceeding the median (PEM), Cohen’s d effect size and analysis improvement percentage. Ferguson (2009) reported values of 0.41, 1.1, and 2.7 for low, medium, and high effects, respectively, in single-subject designs [33].

Results

Description and characteristics of the participants

In this study, 5 patients with an average age of 36 and a standard deviation of 5.2 years participated in cognitive-behavioral therapy (Table 1).

Table 2 presents the difference in Mean±SD and median of the total scores of the PANSS and the DERS.

As seen in Table 2, the average scores of the PANSS and DERS for all subjects in the two phases of intervention and follow-up decreased compared to the baseline. The reduced total score of the scale indicates a decrease in the score of the subscales of positive and negative symptoms. On the other hand, the increased total score of the scale shows an increase in the score of the subscales of positive and negative symptoms. The trial can be seen in Figures 1 and 2, respectively. According to Figures 3 and 4, the slope of the trend line in all participants is small and downward, which indicates a decrease in the scores of PANSS and DERS and the formation of small changes, which means that the change occurred with a small amount and speed. According to Table 3, Cohen’s d effect size and non-overlapping indices in the second and third participants in the PANSS and the first participant in the DERS have large values showing a lot of non-overlapping, meaning a large effect size of the intervention.

The effect size in other participants (except the third participant in the DERS) in both scales shows average values, which indicates the average non-overlapping in the intervention phase compared to the baseline phase.

In Table 4, the percentage of overlapping data in all subjects in both scales is 0.0, which shows the percentage of points in the follow-up phase and states that the downward trend in the follow-up phase has not continued like the intervention phase and the scores of these two scales in the follow-up phase are higher.

Therefore, a slight overlapping exists. The other three indicators show small, medium, and high values, respectively, indicating a low, medium, and high overlap in the follow-up phase compared to the intervention phase. Also, the effect size of Cohen’s d in all participants in the two scales has a small effect size (except for the second participant in the PANSS, which has a medium effect size), and this means that the intervention in the follow-up phase has a small effect size compared to the intervention. In addition, according to the small number of samples in the current research design, the recovery percentage was also used to evaluate the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy [34].

Considering the results obtained in Tables 5 and 6, although CBT effectively reduces positive and negative symptoms and improves emotional regulation, their effect size is not clinically significant.

Discussion

This study was conducted to determine the effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) on positive and negative symptoms and emotional regulation in patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. This research was conducted as a single-subject study in the educational, therapeutic, and research center of psychiatry in Tehran City. The results showed the effectiveness of CBT in reducing positive and negative symptoms and improving emotional regulation. However, the results were not clinically significant. In explaining this result, it can be said that according to the relationship between strong therapeutic cooperation and high effectiveness of treatment [35], it seems that one of the reasons for the low effectiveness of treatment is the lack of strong therapeutic cooperation between the therapist and the patients, the patients resisted solving their problems, and this issue contributed to the effectiveness of the treatment. Perhaps this factor has also caused a little focus on stress and fears related to psychotic symptoms and emotional regulation difficulties of patients, which has played a role in forming negative emotional experiences, such as anxiety and stress, and psychotic symptoms. On the other hand, since schizophrenic patients have weaknesses in monitoring resources and problems [36], they may not perform the therapeutic tasks of the sessions well. This factor has also had a negative effect on them the effectiveness of the treatment.

The decrease in the amount of positive and negative symptoms and difficulty in emotional regulation of the participants shows that the results are consistent with the research findings of Silva et al. [22] and Krakovik et al. [21]. According to Krakovik [21], lack of sufficient motivation of patients in doing therapy tasks and dealing with psychotic symptoms played a crucial role in the low effectiveness of treatment. Also, more focus on intervention sessions on cognitive reconstruction and challenges with beliefs and voices and less focus on intervention sessions on the relationship between the patient and psychotic symptoms may be vital in the low effectiveness of the treatment.

Considering the relationship between CBT and improving emotional regulation [37], CBT can effectively reduce patients’ anxiety by improving emotional regulation. This strategy can be effective in reducing positive and negative psychotic symptoms. Since people with psychosis show cognitive distortions, the goal of cognitive-behavioral therapy is to change dysfunctional thoughts and replace them with more realistic and compatible thoughts, which results in reducing the person’s involvement with their delusions and, as a result, improving emotional regulation and consequently reducing positive and negative symptoms [15]. Therefore, according to the emphasis of CBT experts [38], through cognitive restructuring, providing alternative coping cards, questioning delusional beliefs, re-evaluating one’s experiences and creating alternative strategies, normalization techniques to reduce negative emotions related to positive and negative symptoms, examining the evidence, and relaxation techniques, CBT reduces the anxiety and negative emotions of the patients and plays an effective role in reducing the positive and negative symptoms and improving the emotional regulation. However, these therapeutic consequences are not permanent, and even after two months of follow-up, the results showed that the patient’s symptoms recurred. Another possible interpretation is that due to the weakness of patients with schizophrenia in using coping strategies [35], they cannot replace ineffective coping strategies with efficient coping strategies in the long term, which could be due to patients’ poor self-monitoring. On the other hand, according to the relationship between emotional dysregulation and patients’ reluctance to talk more about their symptoms [22, 39], patients could not use cognitive behavioral therapy to treat their problems by not expressing their full and sufficient opinion about their emotions and problems, and this can be another reason for the low effectiveness of the treatment.

The trend changes in the graphs showed that the participants experienced psychotic symptoms after the treatment and follow-up phase. Therefore, according to the relationship between emotion regulation and psychotic symptoms in patients with schizophrenia [2], CBT reduces the problems related to emotional regulation by reducing patients’ anxiety. In the same way, it has affected patients’ positive and negative symptoms. Also, according to the effect size of Cohen’s d and the percentage of recovery, it can be said that these results are consistent with the findings of the research of Lincoln et al. [37] shows that by correcting beliefs and challenging automatic thoughts, problems caused by emotional regulation of psychopaths can be reduced.

Considering the average effect size of Cohen’s d and the low percentage of recovery, the findings of the present study are consistent with the research results of Weeks et al. [40]. Also, the findings of the research of Naeem et al. [41] show that patients who experience acute psychotic symptoms respond more to CBT. Therefore, the average effect size index in the participants means that although the participants in CBT in decreasing positive and negative symptoms have improved slightly, this effect was not significant, and subjects continued to experience psychotic symptoms along with emotional dysregulation even after treatment.

The findings of Naeem et al.’s research [42] showed that after receiving CBT, patients with schizophrenia showed significant improvement in all measures of psychological damage in the PANSS. They noted that there might be pressure on participants to recover early due to financial poverty in third-world countries, which is a motivation. In these countries, people with schizophrenia usually have little information about non-pharmacological treatment services. Still, by receiving cognitive-behavioral treatment, they gain insight into their disease, which is effective in their treatment [43, 44]. These results are consistent with the present study on the moderate effect size of CBT on psychotic symptoms.

The most critical limitation of the present study was that due to the COVID-19 epidemic, the sampling and implementation of the trial were carried out with strict adherence to health protocols. The small sample size was another limitation of the present study, and if the sample size had been larger, it would have been possible to generalize the results. Also, the findings of this research cannot be generalized to the entire society, so it is suggested to conduct the research with a larger sample size and in a wider geographical area to include a larger population of people with schizophrenia spectrum disorders. Unique and focused treatment on each patient, collaboration with other therapists (such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, nurse, and social worker), and starting treatment after drug stabilization were the strengths of this study.

Conclusion

Cognitive-behavioral therapy is effective in reducing positive and negative psychotic symptoms and improving the emotional regulation of patients with schizophrenia. Still, the data obtained from Cohen’s d effect size and improvement indices showed that the findings are not clinically significant. According to the above results, cognitive-behavioral therapy should be used cautiously as adjunctive therapy in psychiatric centers.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.UWSR.REC.1399.013). Also, the current research was registered in the Clinical Trial Center of Iran under the registration No. IRCT20210412050937N2 on December 14, 2021. The study was conducted at Razi Psychiatry Educational, Therapeutic and Research Center in Tehran City. Written consent was obtained from the participants and their legal guardians to participate in the research. All patients participated in the study with the permission of their legal guardians, and no coercion existed to convince the participants of the study. They had the right to withdraw from the research at any time. Also, the patients and their legal guardians were told that all information would remain confidential and no one would disclose it unless the patient and their guardian requested it. Efforts were made to avoid harming the patients.

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD thesis of Hamid Khakbazin in Rehabilitation Counseling Training Department of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and writing the draft: Hamid Khakbaz, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Seyed Jalal Younisi; Methodology and validation: Hamid Khakbaz and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Analysis: Hamid Khakbaz, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Research and review: Hamid Khakbaz, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Seyed Jalal Younisi, Mohdreza Khodayi Ardakani, Mohammad Hadi Safi, and Samaneh Hosseinzadeh; Sources: Hamid Khakbaz; Edited and finalized: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Seyed Jalal Younisi, Mohammad Reza Khodayi Ardakani, and Mohammad Hadi Safi; Supervision: Seyed Jalal Younisi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to staff and officials of the Razi Educational and Therapeutic Psychiatric Center, who prepared the groundwork for this research.

References

- Galderisi S, Kaiser S, Bitter I, Nordentoft M, Mucci A, Sabé M, et al. EPA guidance on treatment of negative symptoms in schizophrenia. European Psychiatry. 2021; 64(1):E21. [DOI:10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.13] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Upthegrove R, Marwaha S, Birchwood M. Depression and schizophrenia: Cause, consequence, or trans-diagnostic issue? Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2017; 43(2):240-4. [DOI:10.1093/schbul/sbw097] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lincoln TM, Sundag J, Schlier B, Karow A. The relevance of emotion regulation in explaining why social exclusion triggers paranoia in individuals at clinical high risk of psychosis. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2018; 44(4):757-67. [DOI:10.1093/schbul/sbx135] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Nugent KL, Chiappelli J, Rowland LM, Daughters SB, Hong LE. Distress intolerance and clinical functioning in persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Research. 2014; 220(1-2):31-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.07.026] [PMID] [PMCID]

- McGurk SR, Mueser KT. Cognitive functioning, symptoms, and work in supported employment: A review and heuristic model. Schizophrenia Research. 2004; 70(2-3):147-73. [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2004.01.009] [PMID]

- Wheeler A, Robinson E, Robinson G. Admissions to acute psychiatric inpatient services in Auckland, New Zealand: A demographic and diagnostic review. The New Zealand Medical Journal. 2005; 118(1226):U1752. [PMID]

- Mirghaed MT, Gorji HA, Panahi S. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iran: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020; 11:64. [DOI:10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_489_18] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rahimi-Movaghar A, Amin-Esmaeili M, Sharifi V, Hajebi A, Radgoodarzi R, Hefazi M, et al. Iranian mental health survey: Design and field proced. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2014; 9(2):96. [PMID]

- Davarinejad O, Mohammadi Majd T, Golmohammadi F, Mohammadi P, Radmehr F, Alikhani M, et al. Identification of risk factors to predict the occurrences of relapses in individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorder in Iran. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(2):546. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18020546] [PMID] [PMCID]

- McGrath JJ, Richards LJ. Why schizophrenia epidemiology needs neurobiology-and vice versa. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2009; 35(3):577-81. [DOI:10.1093/schbul/sbp004] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Galderisi S, Mucci A, Buchanan RW, Arango C. Negative symptoms of schizophrenia: New developments and unanswered research questions. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2018; 5(8):664-77. [DOI:10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30050-6] [PMID]

- Carbon M, Correll CU. Thinking and acting beyond the positive: The role of the cognitive and negative symptoms in schizophrenia. CNS Spectrums. 2014; 19(S1):35-53. [DOI:10.1017/S1092852914000601] [PMID]

- Correll CU, Schooler NR. Negative symptoms in schizophrenia: A review and clinical guide for recognition, assessment, and treatment. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 2020; 16:519-34. [DOI:10.2147/NDT.S225643] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Milev P, Ho BC, Arndt S, Andreasen NC. Predictive values of neurocognition and negative symptoms on functional outcome in schizophrenia: A longitudinal first-episode study with 7-year follow-up. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005; 162(3):495-506. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.495] [PMID]

- Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005; 353(12):1209-23. [DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa051688] [PMID]

- Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, Diminic S, Stockings E, Scott JG, et al. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2016. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2018; 44(6):1195-203. [DOI:10.1093/schbul/sby058] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mueser KT, Deavers F, Penn DL, Cassisi JE. Psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2013; 9:465-97. [DOI:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185620] [PMID]

- McGregor N, Thompson N, O’Connell KS, Emsley R, van der Merwe L, Warnich L. Modification of the association between antipsychotic treatment response and childhood adversity by MMP9 gene variants in a first-episode schizophrenia cohort. Psychiatry Research. 2018; 262:141-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2018.01.044] [PMID]

- Racenstein JM, Harrow M, Reed R, Martin E, Herbener E, Penn DL. The relationship between positive symptoms and instrumental work functioning in schizophrenia: A 10 year follow-up study. Schizophrenia Research. 2002; 56(1-2):95-103. [DOI:10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00273-0] [PMID]

- Wu EQ, Birnbaum HG, Shi L, Ball DE, Kessler RC, Moulis M, et al. The economic burden of schizophrenia in the United States in 2002. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2005; 66(9):1122-9. [DOI:10.4088/JCP.v66n0906] [PMID]

- Grezellschak S, Lincoln TM, Westermann S. Cognitive emotion regulation in patients with schizophrenia: Evidence for effective reappraisal and distraction. Psychiatry Research. 2015; 229(1-2):434-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.103] [PMID]

- Turner DT, van der Gaag M, Karyotaki E, Cuijpers P. Psychological interventions for psychosis: A meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2014; 171(5):523-38. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13081159] [PMID]

- Jones C, Hacker D, Cormac I, Meaden A, Irving CB. Cognitive behavioural therapy versus other psychosocial treatments for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012; 4:CD008712. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD008712.pub2]

- Mehl S, Werner D, Lincoln TM. Does cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis (CBTp) show a sustainable effect on delusions? A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015; 6:1450. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01450] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Naeem F, Khoury B, Munshi T, Ayub M, Lecomte T, Kingdon D, et al. Brief cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis (CBTp) for schizophrenia: Literature review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy. 2016; 9(1):73-86. [DOI:10.1521/ijct_2016_09_04]

- Gaudiano BA. Cognitive behavior therapies for psychotic disorders: Current empirical status and future directions. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2005; 12(1):33. [DOI:10.1093/clipsy.bpi004]

- Rathod S, Kingdon D, Weiden P, Turkington D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for medication-resistant schizophrenia: A review. Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 2008; 14(1):22-33. [DOI:10.1097/01.pra.0000308492.93003.db] [PMID]

- Turner DT, Burger S, Smit F, Valmaggia LR, van der Gaag M. What constitutes sufficient evidence for case formulation-driven CBT for psychosis? Cumulative meta-analysis of the effect on hallucinations and delusions. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2020; 46(5):1072-85. [DOI:10.1093/schbul/sbaa045] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Beck AT, Rector NA, Stolar N, Grant P. Schizophrenia: Cognitive theory, research, and therapy: New York: Guilford Publications; 2011. [Link]

- Colling C, Evans L, Broadbent M, Chandran D, Craig TJ, Kolliakou A, et al. Identification of the delivery of cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp) using a cross-sectional sample from electronic health records and open-text information in a large UK-based mental health case register. BMJ Open. 2017; 7(7):e015297. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015297] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ince P, Haddock G, Tai S. A systematic review of the implementation of recommended psychological interventions for schizophrenia: Rates, barriers, and improvement strategies. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice. 2016; 89(3):324-50. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12084] [PMID]

- Wykes T. Cognitive-behaviour therapy and schizophrenia. Evidence-Based Mental Health. 2014; 17(3):67-8. [DOI:10.1136/eb-2014-101887] [PMID]

- Morrison AP, Pyle M, Chapman N, French P, Parker SK, Wells A. Metacognitive therapy in people with a schizophrenia spectrum diagnosis and medication resistant symptoms: A feasibility study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2014; 45(2):280-4. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.11.003] [PMID]

- Kråkvik B, Gråwe RW, Hagen R, Stiles TC. Cognitive behaviour therapy for psychotic symptoms: A randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2013; 41(5):511-24. [DOI:10.1017/S1352465813000258] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Silva D, Maguire T, McSherry P, Newman-Taylor K. Targeting affect leads to reduced paranoia in people with psychosis: A single case series. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2021; 49(3):302-13. [DOI:10.1017/S1352465820000788] [PMID]

- Jauhar S, McKenna P, Radua J, Fung E, Salvador R, Laws K. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for the symptoms of schizophrenia: Systematic review and meta-analysis with examination of potential bias. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2014; 204(1):20-9. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.bp.112.116285] [PMID]

- van der Gaag M, Stant AD, Wolters KJ, Buskens E, Wiersma D. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for persistent and recurrent psychosis in people with schizophrenia-spectrum disorder: Cost-effectiveness analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2011; 198(1):59-65. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.071522] [PMID]

- Zimmermann G, Favrod J, Trieu V, Pomini V. The effect of cognitive behavioral treatment on the positive symptoms of schizophrenia spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis. Schizophrenia Research. 2005; 77(1):1-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.018] [PMID]

- Startup M, Jackson M, Bendix S. North Wales randomized controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy for acute schizophrenia spectrum disorders: Outcomes at 6 and 12 months. Psychological Medicine. 2004; 34(3):413-22. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291703001211] [PMID]

- Morrison AP, Nothard S, Bowe SE, Wells A. Interpretations of voices in patients with hallucinations and non-patient controls: A comparison and predictors of distress in patients. Behaviour research and Therapy. 2004; 42(11):1315-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2003.08.009] [PMID]

- Jacobsen P, Tan M. Provision of national institute for health and care excellence-adherent cognitive behavior therapy for psychosis from inpatient to community settings: A national survey of care pathways in NHS mental health trusts. Health Science Reports. 2020; 3(4):e198. [DOI:10.1002/hsr2.198] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Perivoliotis D, Cather C. Cognitive behavioral therapy of negative symptoms. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2009; 65(8):815-30. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.20614] [PMID]

- Saksa JR, Cohen SJ, Srihari VH, Woods SW. Cognitive behavior therapy for early psychosis: A comprehensive review of individual vs. group treatment studies. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy. 2009; 59(3):357-83. [DOI:10.1521/ijgp.2009.59.3.357] [PMID]

- Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006; 163(3):365-73. [DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.365] [PMID]

- Veltro F, Falloon I, Vendittelli N, Oricchio I, Scinto A, Gigantesco A, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural group therapy for inpatients. Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2006; 2(1):1-6. [DOI:10.1186/1745-0179-2-16] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zuidersma M, Riese H, Snippe E, Booij SH, Wichers M, Bos EH. Single-subject research in psychiatry: Facts and fictions. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2020; 11:1174. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.539777] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Voigt A, Kreiter D, Jacobs C, Revenich E, Serafras N, Wiersma M. Clinical network analysis in a bipolar patient using an experience sampling mobile health tool: An n=1 study. Bipolar Disorder. 2018; 4(1):2472-1077.1000121. [DOI:10.4172/2472-1077.1000121]

- Fisher AJ, Bosley HG, Fernandez KC, Reeves JW, Soyster PD, Diamond AE, et al. Open trial of a personalized modular treatment for mood and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2019; 116:69-79. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2019.01.010] [PMID]

- Naeem F, Saeed S, Irfan M, Kiran T, Mehmood N, Gul M, et al. Brief culturally adapted CBT for psychosis (CaCBTp): A randomized controlled trial from a low income country. Schizophrenia Research. 2015; 164(1-3):143-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2015.02.015] [PMID]

- Horner RH, Carr EG, Halle J, McGee G, Odom S, Wolery M. The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education. Exceptional Children. 2005; 71(2):165-79. [DOI:10.1177/001440290507100203]

- Kazdin AE. Single-case experimental designs. Evaluating interventions in research and clinical practice. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2019; 117:3-17. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2018.11.015] [PMID]

- Spidel A, Lecomte T, Kealy D, Daigneault I. Acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis and trauma: Improvement in psychiatric symptoms, emotion regulation, and treatment compliance following a brief group intervention. Psychology and Psychotherapy. 2018; 91(2):248-61. [DOI:10.1111/papt.12159] [PMID]

- Smith L, Centre for Clinical Interventions. Cognitive behavioural therapy for psychotic symptoms: A therapist’s manual. Perth: Centre for Clinical Interventions; 2003. [Link]

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1987; 13(2):261-76. [DOI:10.1093/schbul/13.2.261] [PMID]

- Abolghasemi A. [The relationship of meta-cognitive beliefs with positive and negative symptomes in the schizophrenia patients (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology and Personality. 2007; 5(2):1-10. [Link]

- Ghamari Givi H, Moulavi P, Heshmati R. [Exploration of the factor structure of positive and negative syndrome scale in schizophernia spectrum disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2010; 2(2):1-10. [DOI:10.22075/JCP.2017.2018]

- Mirzaei M, Gharraee B, Birashk B. [The role of positive and negative perfectionism, self-efficacy, worry and emotion regulation in predicting behavioral and decisional procrastination (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry & Clinical Psychology. 2013; 19(3); 230-40. [Link]

- Gratz KL, Roemer L. Multidimensional assessment of emotion regulation and dysregulation: Development, factor structure, and initial validation of the difficulties in emotion regulation scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2004; 26(1):41-54. [DOI:10.1023/B:JOBA.0000007455.08539.94]

- Asgari P, Pasha GR, Aminiyan M. [Relationship between emotion regulation, mental stresses and body image with eating disorders of women (Persian)]. Journal of Thought & Behavior in Clinical Psychology. 2009; 4(13):65-78. [Link]

- Mazloom M, Yaghubi H, Mohammadkhani SH. [The relationship of metacognitive beliefs and emotion regulation difficulties with post traumatic stress disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2014; 8(2):105-13. [Link]

- Ferguson, CJ. An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. In: Kazdin AE, editor. Methodological issues and strategies in clinical research. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association; 2016. [Link]

- Kay SR, Sevy S. Pyramidical model of schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990; 16(3):537-45. [DOI:10.1093/schbul/16.3.537] [PMID]

- Salmani B, Hasani J, Hassan Abadi H, Mohammad Khani S. [Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy with or without metacognitive techniques and zolpidem 10 mg. for people with chronic insomnia disorder (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Psychological Health. 2019; 13(1):1-23. [DOI: 10.52547/rph.13.1.1]

- Keefe RS, Arnold MC, Bayen UJ, McEvoy JP, Wilson WH. Source-monitoring deficits for self-generated stimuli in schizophrenia: Multinomial modeling of data from three sources. Schizophrenia Research. 2002; 57(1):51-67. [DOI:10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00306-1] [PMID]

- Hayward M, Berry K, Ashton A. Applying interpersonal theories to the understanding of and therapy for auditory hallucinations: A review of the literature and directions for further research. Clinical Psychology Review. 2011; 31(8):1313-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2011.09.001] [PMID]

- Paulik G. The role of social schema in the experience of auditory hallucinations: A systematic review and a proposal for the inclusion of social schema in a cognitive behavioural model of voice hearing. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2012; 19(6):459-72. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.768] [PMID]

- Morrison AP, Turkington D, Wardle M, Spencer H, Barratt S, Dudley R, et al. A preliminary exploration of predictors of outcome and cognitive mechanisms of change in cognitive behaviour therapy for psychosis in people not taking antipsychotic medication. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012; 50(2):163-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.brat.2011.12.001] [PMID]

- Wykes T, Steel C, Everitt B, Tarrier N. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia: Effect sizes, clinical models, and methodological rigor. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 2008; 34(3):523-37. [DOI:10.1093/schbul/sbm114] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Naeem F, Kingdon D, Turkington D. Predictors of response to cognitive behaviour therapy in the treatment of schizophrenia: A comparison of brief and standard interventions. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2008; 32(5):651-6. [DOI:10.1007/s10608-008-9186-x]

- Naeem F, Ayub M, Kingdon D, Gobbi M. Views of depressed patients in Pakistan concerning their illness, its causes, and treatments. Qualitative Health Research. 2012; 22(8):1083-93. [DOI:10.1177/1049732312450212] [PMID]

- Naeem F, Sarhandi I, Gul M, Khalid M, Aslam M, Anbrin A, et al. A multicentre randomised controlled trial of a carer supervised culturally adapted CBT (CaCBT) based self-help for depression in Pakistan. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2014; 156:224-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.051] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Clinical Psycology

Received: 19/07/2022 | Accepted: 17/12/2022 | Published: 1/01/2023

Received: 19/07/2022 | Accepted: 17/12/2022 | Published: 1/01/2023

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |