Volume 21, Issue 3 (Autumn 2020)

jrehab 2020, 21(3): 406-421 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Yousefi M, Younesi S J, Farhoudian A, Safi M H. Effect of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy on Impulsivity of Patients With Methamphetamine Use Disorder. jrehab 2020; 21 (3) :406-421

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2637-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2637-en.html

1- Department of Counseling, Islamic Azad University, Roodehen Branch, Roodehen, Iran. , mehdi.y.71@gmail.com

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Substance abuse and Dependency Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Educational Sciences & Psychology, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran.

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Substance abuse and Dependency Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Educational Sciences & Psychology, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 5621 kb]

(1991 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5320 Views)

Full-Text: (3608 Views)

Introduction

mphetamine dependence is a significant health concern that contributes to the global burden of disease [1]. It is also considered a new health problem in Iranian society [2]. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Iran ranks fifth among the countries with the highest amphetamine use rate [3]. Alammehrjerdi et al. reported that the prevalence of methamphetamine dependence increased from 3.9% among men and women in 2007 to 60.3% among men in 2014 and 89.5% among women in 2015-2016. The prevalence was higher in women than in men [4]. Some studies have shown a difference between the personality traits of men addicted to opiates and methamphetamine. Therefore, recognizing personality and its characteristics can be effective in the prevention and treatment of this problem [9].

Impulsivity is conceptualized as a cognitive dimension. Impulsivity is associated with a lack of cognitive inhibition and an incomplete decision-making process in individuals. Impulsivity is one of the characteristics of different types of addiction. Functional problems due to impulsivity such as low inhibition, decision making, and planning are major obstacles in treating people with substance use disorders at the beginning, progression, and continuation of treatment. Decreased stimulus or impulse control ability is known as an indicator of addiction [10]. Bickel et al. showed that because of prefrontal cortex damage, executive functions and impulse control ability in impulsive individuals are very poor [12]. For this reason, these people have many problems with purposeful behaviors and self-regulation. Impulsivity causes poor therapeutic outcomes in substance abusers [5, 13].

Based on the evidence, the acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a promising intervention for substance users [14]. Khalbaz et al. reported the effectiveness of group ACT in improving the emotional regulation of methamphetamine-dependent individuals undergoing rehabilitation [15]. Ghouchani et al. reported the effectiveness of ACT in improving aggression of patients with psychosis due to methamphetamine use compared to controls [16]. ACT is a behavioral therapy that focuses on behavior change using acceptance and mindfulness strategies instead of focusing on reducing symptoms. Therefore, we hypothesized that ACT could treat impulsivity in rehabilitated methamphetamine-dependent individuals.

Materials and Methods

This is a quasi-experimental study with a pre-test and post-test and follow-up design. The study population consists of all men with methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) who were in the abstinence period and participated in the meetings of the Association of Anonymous Addicts in Yazd City, Iran, in 2018. Through the purposive sampling method, 24 samples were selected from among those who had a larger Barratt impulsiveness scale (BIS) score and met the inclusion criteria, and then randomly divided into the intervention (n=12) and control (n=12) groups. The inclusion criteria were the ability to communicate verbally, minimum literacy to read and answer the questions, complete abstinence and non-use of methamphetamine at least in the last 6 months, completion of treatment in the past 6 months, aged 18-60 years, and no mental or physical disability that can avoid participation and evaluation. The exclusion criteria were recurrence and re-use of methamphetamine at the time of participation in the study and having AIDS or hepatitis.

To collect data, a demographic form with 13 items (surveying age, education, occupation, etc.) and the BIS questionnaire were used. Barratt developed the BIS in 1994 [20]. Its scores are very well related to Eisenhower’s impulsivity questionnaire, and the questions indicate dimensions of bad decision-making and lack of planning. It has 30 items rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale and three subscales of attentional impulsiveness, motor impulsiveness, and non-planning impulsiveness. By summing the scores of the three subscales, the total score is obtained. The maximum score is 120. ACT was applied to the intervention group in eight sessions of 60 minutes, while the control group received no intervention. However, to comply with the ethical principles, a meeting was held for the control group to become familiar with the concepts of ACT. The ACT protocol was adapted from Khalbaz et al. study [15]. The obtained data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential statistics such as ANCOVA and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (to evaluate the normality of data distribution).

Results

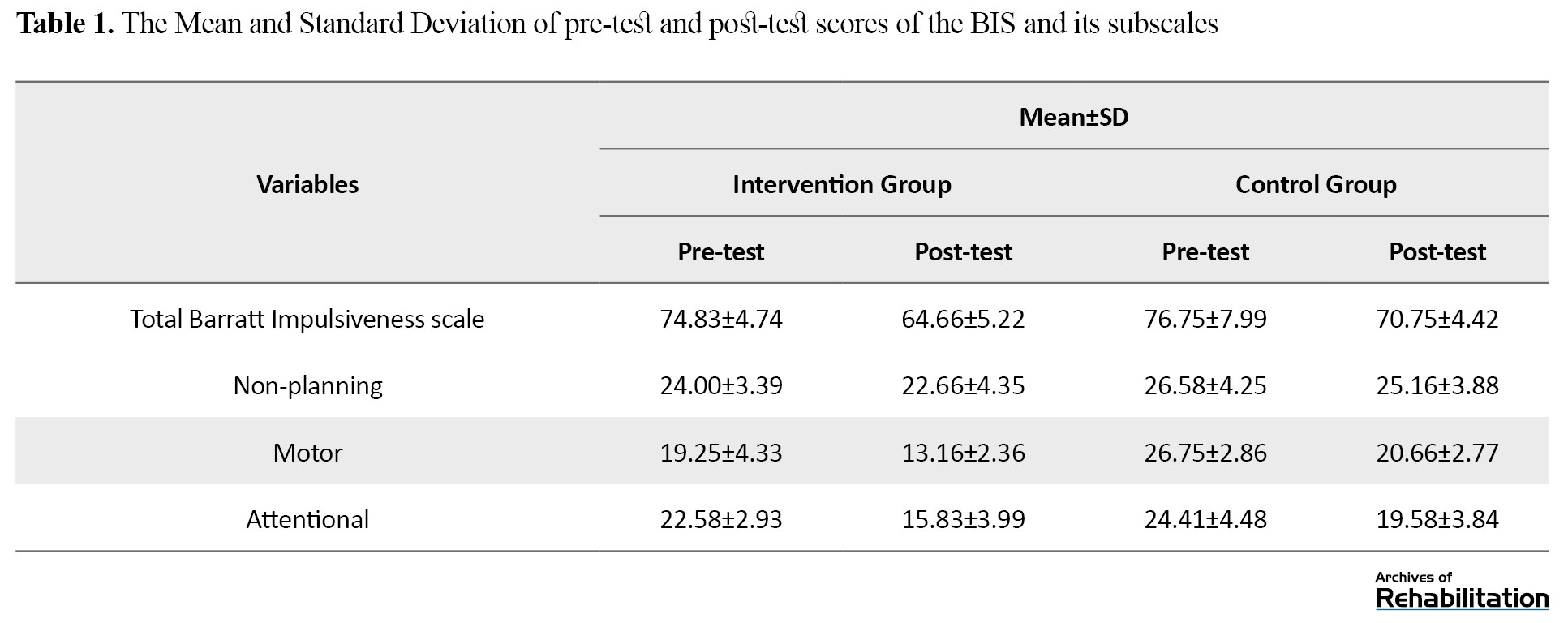

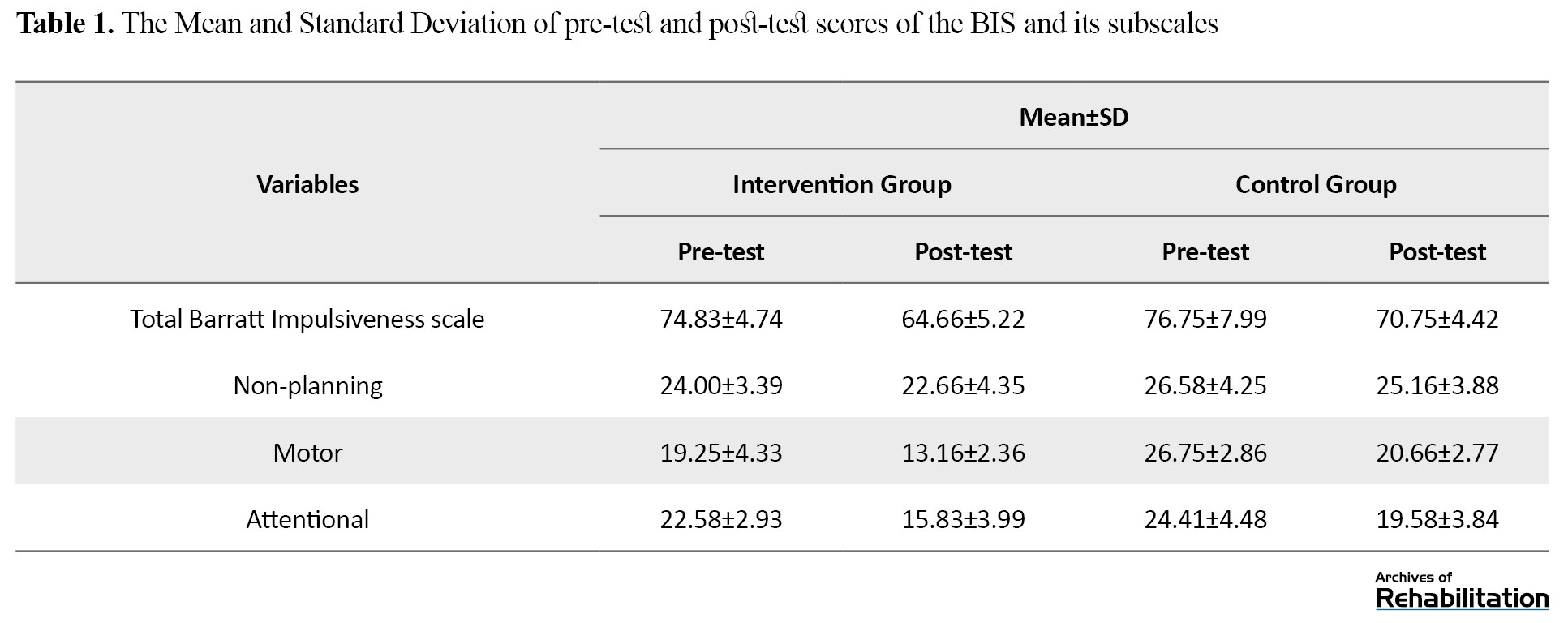

The mean age of participants in the intervention group was 38.66 years, and the mean age of the control group was 38.00 years. Most participants in the intervention group (25%) had primary and secondary education, and in the control group (33.3%) had primary education. Most of them in the intervention and control groups were employed in the private sector (33.3% and 41.7%, respectively) and lived in rented houses (83.3% and 41.7%, respectively). Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviation of pre-test and post-test scores of the BIS and its subscales.

The results showed a decrease in the overall score and subscale scores of the BIS after the intervention. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results showed the normal distribution of scores of the two groups in all variables (P>0.05). The results of Levene’s test showed the equality of variances in the scores. To investigate the homogeneity of regression slope, the interaction of the independent variable with the covariates was measured. Since the value of the F statistic was not significant for any of the variables, so the assumption of homogeneity of regression slope was confirmed. It should be noted that in this study, post-test scores of attentional, motor, and non-planning impulsiveness were considered as dependent variables, and their pre-test scores were considered as covariates. If the interaction between the pre-test and the group is not significant for the dependent variables (post-test), then the regression slopes are parallel in the intervention and control groups.

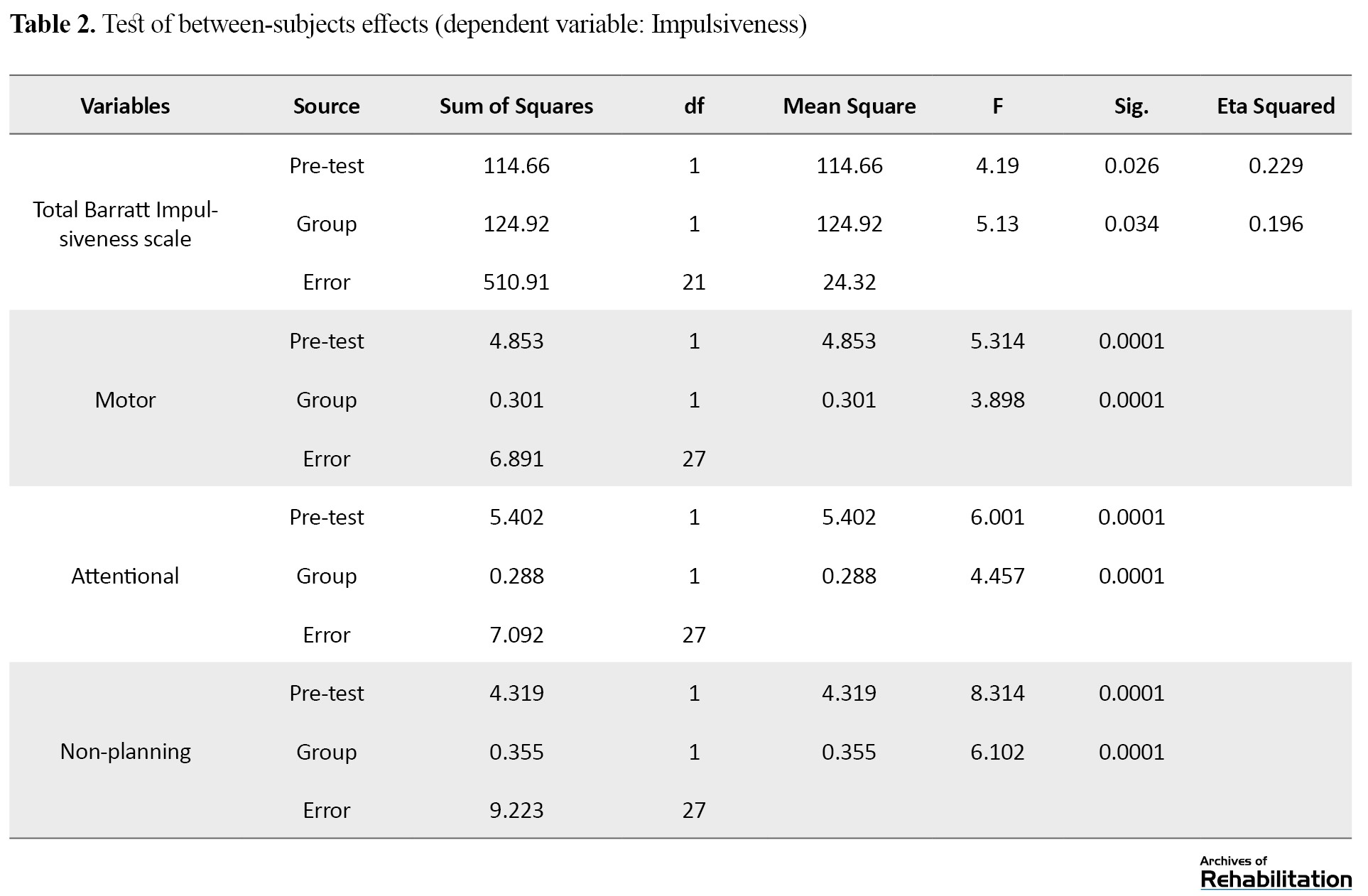

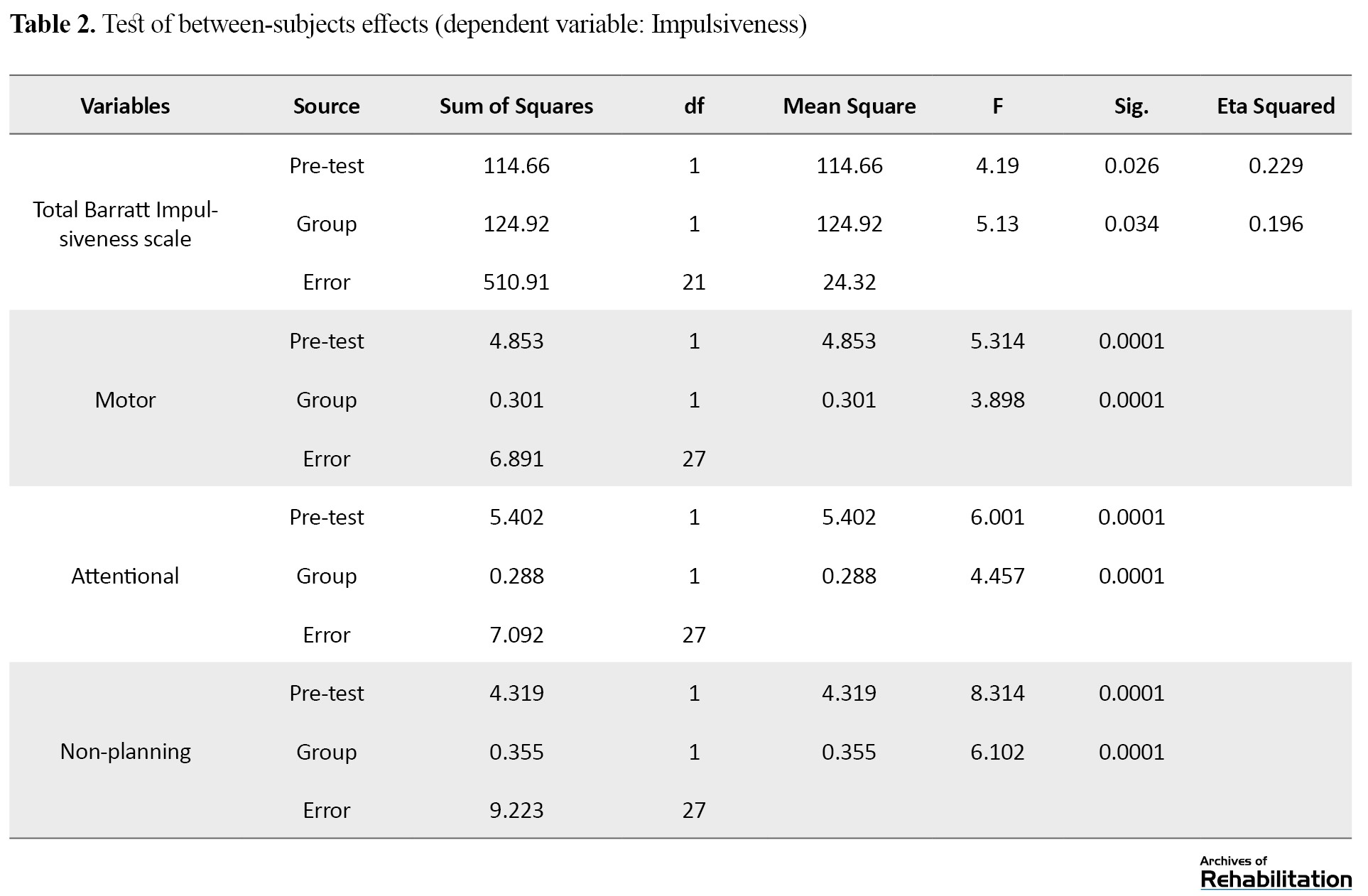

The research hypothesis was that ACT reduces the impulsivity of improved patients with MUD. ANCOVA was used to test the hypothesis. The results are presented in Table 2.

The value of F for the overall BIS pre-test score was 4.19 (P<0.05). Hence, there was a significant correlation between the pre-test overall BIS and the group factor (independent variable). The value of F for the group factor of pre-test overall BIS was 5.13 (P<0.05). Hence, there was a significant difference in the mean overall BIS score of MUD patients between the control and intervention groups in the post-test phase. Therefore, this result supports our hypothesis. The values of F for the pre-test scores of the three BIS dimensions were also significant (P<0.05). Thus, the correlation between the pre-test scores of these BIS dimensions and the group factor was reported. The values of F for the group factor of BIS dimensions were also significant (P<0.05). Hence, there was a significant difference in the mean scores of BIS dimensions in MUD patients between the control and intervention groups in the post-test phase.

Discussion

In this study, ACT in 8 sessions of 60 minutes reduced impulsivity and its three dimensions in rehabilitated MUD patients. Despite the low number of studies on the effect of ACT on impulsivity of MUD patients, it can be said that the results of the present study are consistent with the results of Morrison et al. [22], Gomez et al. [23], Nadimi [24], Borjali et al. [25] and Aazam et al. [26]. They reported that the third-wave behavioral therapies, including ACT, could effectively reduce impulsivity and impulsive behaviors. People addicted to methamphetamine have difficulty controlling their impulses. Improving impulse control ability by ACT can reduce aggression and its dimensions [27]. Impulsivity is recognized as a hallmark of addiction. It is associated with various high-risk behaviors and poor therapeutic outcomes in substance abusers [10, 13]. Addicted people, who lack a rational and efficient strategy towards problems, often use inefficient and often aggressive methods in dealing with issues and people [28]. However, lower impulsivity decreases the likelihood of substance abuse and related problems [29].

One of the reasons for the effectiveness of ACT on reducing impulsivity is the mindfulness technique, which is one of the important processes of ACT. Although Mindfulness and impulsivity have common features, they have fundamental functional differences [31]. Both focus on the present time, but in a different way. Mindfulness highlights the transient nature of everything. Mindfulness emphasizes the value of awareness of actions that involve paying attention to, observing, and describing an experience without judgment. Impulsivity indicates an excessive focus on the present time, which prevents people from watching the consequences of their actions. Therefore, mindfulness aims to increase awareness of values and promote activities following the pursued goals, while impulsivity is defined as behaving without thinking about its long-term consequences. Mindfulness can help raise awareness of automatic thoughts, thus increasing a person’s ability to consider the potential consequences of actions before engaging in them.

Raising awareness may improve self-regulation, which is essential when facing severe sudden pulses for having behaviors that may have negative consequences. ACT is based on the premise that distorting cognitive processes increases unpleasant feelings. It can help people avoid problematic behaviors such as alcohol consumption, substance abuse, or high-risk sexual behaviors [32], resulting in reduced unpleasant feelings. In facing negative emotions, people cannot focus on their purposeful activities. People who experience negative emotions face more problems, such as loss of concentration or ineffective problem-solving. After receiving ACT and directly accepting and experiencing unpleasant feelings, one focuses on having a worthwhile life instead of cognitive change or reducing the intensity of emotions [33]. Emotional disturbances lead to loss of control, and people become prone to do and say things they do not usually commit. Therefore, it can be said that people with these conditions are drawn to substance abuse, which is a lousy option in response to difficulties and problems. This issue can be raised to increase positive emotions and avoiding negative emotions. From the perspective of ACT, the limitation of behavioral options is the heart of psychotherapy. MUD patients choose more flexible and sustainable options for their value-based behaviors [34]. Therefore, strategies such as mindfulness and ACT can reduce impulsivity and especially behaviors such as substance abuse.

Conclusion

The ACT, as emerging third-wave behavior therapy, is a beneficial interventional method for rehabilitated MUD patients to reduce their impulsive behaviors. Therefore, applying the main concepts of ACT to these patients has a significant and undeniable role in increasing their mental health and improving their quality of life and lifestyle.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study obtained its ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (code: IR.USWR.REC.1397.110).

Funding

This study was extracted from the MA. thesis of first author at Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

All authors would like to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

References

mphetamine dependence is a significant health concern that contributes to the global burden of disease [1]. It is also considered a new health problem in Iranian society [2]. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Iran ranks fifth among the countries with the highest amphetamine use rate [3]. Alammehrjerdi et al. reported that the prevalence of methamphetamine dependence increased from 3.9% among men and women in 2007 to 60.3% among men in 2014 and 89.5% among women in 2015-2016. The prevalence was higher in women than in men [4]. Some studies have shown a difference between the personality traits of men addicted to opiates and methamphetamine. Therefore, recognizing personality and its characteristics can be effective in the prevention and treatment of this problem [9].

Impulsivity is conceptualized as a cognitive dimension. Impulsivity is associated with a lack of cognitive inhibition and an incomplete decision-making process in individuals. Impulsivity is one of the characteristics of different types of addiction. Functional problems due to impulsivity such as low inhibition, decision making, and planning are major obstacles in treating people with substance use disorders at the beginning, progression, and continuation of treatment. Decreased stimulus or impulse control ability is known as an indicator of addiction [10]. Bickel et al. showed that because of prefrontal cortex damage, executive functions and impulse control ability in impulsive individuals are very poor [12]. For this reason, these people have many problems with purposeful behaviors and self-regulation. Impulsivity causes poor therapeutic outcomes in substance abusers [5, 13].

Based on the evidence, the acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is a promising intervention for substance users [14]. Khalbaz et al. reported the effectiveness of group ACT in improving the emotional regulation of methamphetamine-dependent individuals undergoing rehabilitation [15]. Ghouchani et al. reported the effectiveness of ACT in improving aggression of patients with psychosis due to methamphetamine use compared to controls [16]. ACT is a behavioral therapy that focuses on behavior change using acceptance and mindfulness strategies instead of focusing on reducing symptoms. Therefore, we hypothesized that ACT could treat impulsivity in rehabilitated methamphetamine-dependent individuals.

Materials and Methods

This is a quasi-experimental study with a pre-test and post-test and follow-up design. The study population consists of all men with methamphetamine use disorder (MUD) who were in the abstinence period and participated in the meetings of the Association of Anonymous Addicts in Yazd City, Iran, in 2018. Through the purposive sampling method, 24 samples were selected from among those who had a larger Barratt impulsiveness scale (BIS) score and met the inclusion criteria, and then randomly divided into the intervention (n=12) and control (n=12) groups. The inclusion criteria were the ability to communicate verbally, minimum literacy to read and answer the questions, complete abstinence and non-use of methamphetamine at least in the last 6 months, completion of treatment in the past 6 months, aged 18-60 years, and no mental or physical disability that can avoid participation and evaluation. The exclusion criteria were recurrence and re-use of methamphetamine at the time of participation in the study and having AIDS or hepatitis.

To collect data, a demographic form with 13 items (surveying age, education, occupation, etc.) and the BIS questionnaire were used. Barratt developed the BIS in 1994 [20]. Its scores are very well related to Eisenhower’s impulsivity questionnaire, and the questions indicate dimensions of bad decision-making and lack of planning. It has 30 items rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale and three subscales of attentional impulsiveness, motor impulsiveness, and non-planning impulsiveness. By summing the scores of the three subscales, the total score is obtained. The maximum score is 120. ACT was applied to the intervention group in eight sessions of 60 minutes, while the control group received no intervention. However, to comply with the ethical principles, a meeting was held for the control group to become familiar with the concepts of ACT. The ACT protocol was adapted from Khalbaz et al. study [15]. The obtained data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation) and inferential statistics such as ANCOVA and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test (to evaluate the normality of data distribution).

Results

The mean age of participants in the intervention group was 38.66 years, and the mean age of the control group was 38.00 years. Most participants in the intervention group (25%) had primary and secondary education, and in the control group (33.3%) had primary education. Most of them in the intervention and control groups were employed in the private sector (33.3% and 41.7%, respectively) and lived in rented houses (83.3% and 41.7%, respectively). Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviation of pre-test and post-test scores of the BIS and its subscales.

The results showed a decrease in the overall score and subscale scores of the BIS after the intervention. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test results showed the normal distribution of scores of the two groups in all variables (P>0.05). The results of Levene’s test showed the equality of variances in the scores. To investigate the homogeneity of regression slope, the interaction of the independent variable with the covariates was measured. Since the value of the F statistic was not significant for any of the variables, so the assumption of homogeneity of regression slope was confirmed. It should be noted that in this study, post-test scores of attentional, motor, and non-planning impulsiveness were considered as dependent variables, and their pre-test scores were considered as covariates. If the interaction between the pre-test and the group is not significant for the dependent variables (post-test), then the regression slopes are parallel in the intervention and control groups.

The research hypothesis was that ACT reduces the impulsivity of improved patients with MUD. ANCOVA was used to test the hypothesis. The results are presented in Table 2.

The value of F for the overall BIS pre-test score was 4.19 (P<0.05). Hence, there was a significant correlation between the pre-test overall BIS and the group factor (independent variable). The value of F for the group factor of pre-test overall BIS was 5.13 (P<0.05). Hence, there was a significant difference in the mean overall BIS score of MUD patients between the control and intervention groups in the post-test phase. Therefore, this result supports our hypothesis. The values of F for the pre-test scores of the three BIS dimensions were also significant (P<0.05). Thus, the correlation between the pre-test scores of these BIS dimensions and the group factor was reported. The values of F for the group factor of BIS dimensions were also significant (P<0.05). Hence, there was a significant difference in the mean scores of BIS dimensions in MUD patients between the control and intervention groups in the post-test phase.

Discussion

In this study, ACT in 8 sessions of 60 minutes reduced impulsivity and its three dimensions in rehabilitated MUD patients. Despite the low number of studies on the effect of ACT on impulsivity of MUD patients, it can be said that the results of the present study are consistent with the results of Morrison et al. [22], Gomez et al. [23], Nadimi [24], Borjali et al. [25] and Aazam et al. [26]. They reported that the third-wave behavioral therapies, including ACT, could effectively reduce impulsivity and impulsive behaviors. People addicted to methamphetamine have difficulty controlling their impulses. Improving impulse control ability by ACT can reduce aggression and its dimensions [27]. Impulsivity is recognized as a hallmark of addiction. It is associated with various high-risk behaviors and poor therapeutic outcomes in substance abusers [10, 13]. Addicted people, who lack a rational and efficient strategy towards problems, often use inefficient and often aggressive methods in dealing with issues and people [28]. However, lower impulsivity decreases the likelihood of substance abuse and related problems [29].

One of the reasons for the effectiveness of ACT on reducing impulsivity is the mindfulness technique, which is one of the important processes of ACT. Although Mindfulness and impulsivity have common features, they have fundamental functional differences [31]. Both focus on the present time, but in a different way. Mindfulness highlights the transient nature of everything. Mindfulness emphasizes the value of awareness of actions that involve paying attention to, observing, and describing an experience without judgment. Impulsivity indicates an excessive focus on the present time, which prevents people from watching the consequences of their actions. Therefore, mindfulness aims to increase awareness of values and promote activities following the pursued goals, while impulsivity is defined as behaving without thinking about its long-term consequences. Mindfulness can help raise awareness of automatic thoughts, thus increasing a person’s ability to consider the potential consequences of actions before engaging in them.

Raising awareness may improve self-regulation, which is essential when facing severe sudden pulses for having behaviors that may have negative consequences. ACT is based on the premise that distorting cognitive processes increases unpleasant feelings. It can help people avoid problematic behaviors such as alcohol consumption, substance abuse, or high-risk sexual behaviors [32], resulting in reduced unpleasant feelings. In facing negative emotions, people cannot focus on their purposeful activities. People who experience negative emotions face more problems, such as loss of concentration or ineffective problem-solving. After receiving ACT and directly accepting and experiencing unpleasant feelings, one focuses on having a worthwhile life instead of cognitive change or reducing the intensity of emotions [33]. Emotional disturbances lead to loss of control, and people become prone to do and say things they do not usually commit. Therefore, it can be said that people with these conditions are drawn to substance abuse, which is a lousy option in response to difficulties and problems. This issue can be raised to increase positive emotions and avoiding negative emotions. From the perspective of ACT, the limitation of behavioral options is the heart of psychotherapy. MUD patients choose more flexible and sustainable options for their value-based behaviors [34]. Therefore, strategies such as mindfulness and ACT can reduce impulsivity and especially behaviors such as substance abuse.

Conclusion

The ACT, as emerging third-wave behavior therapy, is a beneficial interventional method for rehabilitated MUD patients to reduce their impulsive behaviors. Therefore, applying the main concepts of ACT to these patients has a significant and undeniable role in increasing their mental health and improving their quality of life and lifestyle.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study obtained its ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (code: IR.USWR.REC.1397.110).

Funding

This study was extracted from the MA. thesis of first author at Department of Counseling, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran.

Authors' contributions

All authors equally contributed to preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

All authors would like to thank the Vice Chancellor for Research of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

References

- Degenhardt L, Baxter AJ, Lee YY, Hall W, Sara GE, Johns N, et al. The global epidemiology and burden of psychostimulant dependence: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2014; 137:36-47. [DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.12.025] [PMID]

- Noori R, Daneshmand R, Farhoudian A, Ghaderi S, Aryanfard S, Moradi A. Amphetamine-type stimulants in a group of adults in Tehran, Iran: A rapid situation assessment in twenty-two districts. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences. 2016; 10(4):e7704. [DOI:10.17795/ijpbs-7704]

- Hadadi R, Ghorbani M, Rostami R, Keshavarz G, Farahani E. [The outcome of matrix model of therapy on quality of life in methamphetamine abusers (Persian)]. Research on Addiction. 2016; 10(39):95-108. http://etiadpajohi.ir/article-1-943-en.html

- Alammehrjerdi Z, Ezard N, Dolan K. Methamphetamine dependence in methadone treatment services in Iran: The first literature review of a new health concern. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2018; 31:49-55. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajp.2018.01.001] [PMID]

- Stevens L, Verdejo-García A, Goudriaan AE, Roeyers H, Dom G, Vanderplasschen W. Impulsivity as a vulnerability factor for poor addiction treatment outcomes: A review of neurocognitive findings among individuals with substance use disorders. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2014; 47(1):58-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsat.2014.01.008] [PMID]

- Siyam Sh. [Drug abuse prevalence between male students of different universities in Rasht in 2005 (Persian)]. Zahedan Journal of Research in Medical Sciences. 2006; 8(4):e94869. https://sites.kowsarpub.com/zjrms/articles/94869.html

- Farnam A. [The effectiveness of matrix model in relapse prevention and coping skills enhancement in participants with substance dependency (Persian)]. Research on Addiction. 2013; 7(25):25-38. http://etiadpajohi.ir/article-1-298-en.html

- Najafi M, Farhoudian A, Alivandi-Vafa M, Ekhtiari H, Massah O. [Comparing emotion regulation in methamphetamine abuser with and without risky behavior (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2014; 14(S1):9-14. http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1452-en.html

- A'rab A, Azkhosh M, Farhoudian A, Dolatshahi B, Farzi M. [The Comparison of Personality Traits of Two Groups of Men Who Are Dependent to Opiates or Methamphetamine (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2012; 12:14-20. http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-993-en.html

- Maraz A, Andó B, Rigó P, Harmatta J, Takách G, Zalka Z, et al. The two-faceted nature of impulsivity in patients with borderline personality disorder and substance use disorder. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016; 163:48-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.03.015] [PMID]

- Doustian Y, Bahmani B, A'zami Y, Godini AA. [The relationship between aggression and impulsiveness with susceptibility for addiction in male student (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2013; 14(2):102-9. http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1220-en.html

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Gatchalian KM, McClure SM. Are executive function and impulsivity antipodes? A conceptual reconstruction with special reference to addiction. Psychopharmacology. 2012; 221(3):361-87. [DOI:10.1007/s00213-012-2689-x] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Loree AM, Lundahl LH, Ledgerwood DM. Impulsivity as a predictor of treatment outcome in substance use disorders: Review and synthesis. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2015; 34(2):119-34. [DOI:10.1111/dar.12132] [PMID]

- Forouzanfar A. [Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and substance abuse disorders: A theoretical and research review (Persian)]. Social Health & Addiction. 2016; 3(9):131-60. http://ensani.ir/fa/article/364648/

- Khakbaz H, Farhoudian A, Azkhosh M, Dolatshahi B, Karami H, Massah O. The effectiveness of group acceptance and commitment therapy on emotion regulation in methamphetamine-dependent individuals undergoing rehabilitation. International Journal of High Risk Behaviors and Addiction. 2016; 5(4):e28329. [DOI:10.5812/ijhrba.28329]

- Ghouchani Sh, Molavi N, Massah O, Sadeghi M, Mousavi SH, Noroozi M, et al. Effectiveness of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) on aggression of patients with psychosis due to methamphetamine use: A pilot study. Journal of Substance Use. 2018; 23(4):402-7. [DOI:10.1080/14659891.2018.1436602]

- Gaudiano BA, Herbert JD, Hayes SC. Is it the symptom or the relation to it? Investigating potential mediators of change in acceptance and commitment therapy for psychosis. Behavior Therapy. 2010; 41(4):543-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.beth.2010.03.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zarling AN. A preliminary trial of ACT skills training for aggressive behavior [PhD. dissertation]. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa; 2013. [DOI:10.17077/etd.vevz0zh6]

- Stotts AL, Green C, Masuda A, Grabowski J, Wilson K, Northrup TF, et al. A stage I pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy for methadone detoxification. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2012; 125(3):215-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.02.015] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ekhtiari H, Safaei H, Shirzad H, Mokri A, Mahintorabi S. [Is there any relationship between demographics and impulsive behavior indices with HIV infection in homeless heroin injectors? (Persian)]. Social Welfare Quarterly. 2009; 9(34):207-23. http://refahj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1845-en.html

- Naderi F, Haghshenas F. [The relationship between impulsivity, loneliness and the mobile phone usage rate in male and female students of Ahvaz Islamic Azad University (Persian)]. Journal of Social Psychology (New Findings in Psychology). 2009; 4(12);111-21. https://www.sid.ir/fa/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?ID=124263

- Morrison KL, Smith BM, Ong CW, Lee EB, Friedel JE, Odum A, et al. Effects of acceptance and commitment therapy on impulsive decision-making. Behavior Modification. 2020; 44(4):600-23. [DOI:10.1177/0145445519833041] [PMID]

- Gómez MJ, Luciano C, Páez-Blarrina M, Ruiz FJ, Valdivia-Salas S, Gil-Luciano B. Brief ACT protocol in at-risk adolescents with conduct disorder and impulsivity. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2014; 14(3):307-32. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2014-47636-001

- Nadimi M. [Effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy (based on skills training) on reduce impulsivity and increase emotional regulation in women dependent on methamphetamine (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal. 2016; 5(1):47-74. http://frooyesh.ir/article-1-310-en.html

- Borjali A, Bagiyan MJ, Yazdanpanah MA, Rajabi M. [The effectiveness of group mindfulness-based cognitive therapy on obsessive-compulsive disorder, metacognition beliefs and rumination (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Studies. 2015; 5(20):133-61. https://jcps.atu.ac.ir/article_1867.html

- Aazam Y, Sohrabi F, Borjali A, Chopan H. [The effectiveness of teaching emotion regulation based on gross model in reducing impulsivity in drug-dependent people (Persian)]. Research on Addiction. 2014; 8(30):127-41. http://etiadpajohi.ir/article-1-648-fa.html

- Mohammadi M, Farhoudian A, Shoaee F, Younesi SJ, Dolatshahi B. Aggression in juvenile delinquents and mental rehabilitation group therapy based on acceptance and commitment. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2015; 13(2):5-9. http://irj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-419-en.html

- Nutt D. Drugs-without the hot air: Minimising the harms of legal and illegal drugs. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie. 2012; 54(12):1060-1. https://www.tijdschriftvoorpsychiatrie.nl/en/issues/460/articles/9630

- King KM, Fleming CB, Monahan KC, Catalano RF. Changes in self-control problems and attention problems during middle school predict alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use during high school. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2011; 25(1):69-79. [DOI:10.1037/a0021958] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gullo MJ, Dawe Sh. Impulsivity and adolescent substance use: Rashly dismissed as “all-bad”? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008; 32(8):1507-18. [DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.06.003] [PMID]

- Murphy C, MacKillop J. Living in the here and now: Interrelationships between impulsivity, mindfulness, and alcohol misuse. Psychopharmacology. 2012; 219(2):527-36. [DOI:10.1007/s00213-011-2573-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Blackledge JT, Hayes SC. Emotion regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2001; 57(2):243-55. [DOI:10.1002/1097-4679(200102)57:2<243::aid-jclp9>3.0.co;2-x] [PMID]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, editors. A practical guide to acceptance and commitment therapy. Boston, MA: Springer; 2004. [DOI:10.1007/978-0-387-23369-7]

- Eifert GH, Forsyth JP. The application of acceptance and commitment therapy to problem anger. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2011; 18(2):241-50. [DOI:10.1016/j.cbpra.2010.04.004]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Addiction

Received: 14/05/2019 | Accepted: 16/07/2020 | Published: 1/10/2020

Received: 14/05/2019 | Accepted: 16/07/2020 | Published: 1/10/2020

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |