Volume 26, Issue 4 (Winter 2026)

jrehab 2026, 26(4): 572-605 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.UMA.REC.1404.019

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Piri E, Jafarnezhadgero A, Dehghani M. Effects of Insole Type and Fatigue on the Electrical Activity of Lower Limb Muscles During Running in Men With Foot Pronation and ACL Reconstruction: A Clinical Trial. jrehab 2026; 26 (4) :572-605

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3700-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3700-en.html

1- Department of Sports Biomechanics, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran.

2- Department of Sports Biomechanics, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. ,amiralijafarnezhad@gmail.com

2- Department of Sports Biomechanics, Faculty of Educational Sciences and Psychology, University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. ,

Keywords: Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), Fatigue, Frequency spectrum, foot pronation (FP), Running

Full-Text [PDF 6281 kb]

(85 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1136 Views)

References

Full-Text: (69 Views)

Introduction

Running, despite its well-established benefits for enhancing cardiorespiratory fitness and contributing to body type determination, carries a considerable risk of lower-extremity injury. Reports indicate that 2-38 injuries per 1,000 hours of running may occur [1]. Severe injuries such as complete rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) generally require surgical intervention followed by a prolonged, structured rehabilitation program to restore knee joint stability and normal functional performance [2]. The concurrent presence of a pronation deformity (excessive foot inward rotation) alongside ACL rupture introduces significant clinical challenges, as the ACL plays a critical role in preventing anterior tibial translation relative to the femur and controlling knee internal rotation. Inadequate postoperative rehabilitation may lead to complications such as joint instability, reduced muscular strength, particularly in the quadriceps, altered movement patterns, and an increased risk of secondary injuries to the meniscus and articular cartilage [3, 4].

The prevalence of foot pronation (FP) is estimated to range from 48% to 78% in youth and from 20% to 23% in adults [5, 6]. In contrast, epidemiological data indicate that 30-70 new ACL injuries per 100,000 individuals occur annually in the general population. In the United States alone, more than 200,000 new ACL injuries are reported each year, and approximately 100,000 ACL reconstruction (ACLR) surgeries are performed [7]. FP is a structural abnormality characterized by a reduced medial longitudinal arch and altered alignment of the ankle joint [8].

Multiple surgical techniques are available for ACLR; their choice depends on the injury severity and the patient’s functional goals. These techniques involve grafts harvested from the hamstring tendons, the patellar tendon, the quadriceps tendon, or the Achilles tendon. When selecting a graft type, key considerations include the individual’s activity level, the biological compatibility of the transplanted tissue, and its mechanical strength in resisting re-injury or graft failure [9]. Recent studies indicate that the rate of ACLR failure ranges from 5% to 25%, influenced by factors such as inadequate rehabilitation, premature return to sport, muscular weakness, and insufficient graft fixation, with the highest risk of reinjury occurring within the first two postoperative years [10, 11]. FP is recognized as an independent risk factor for ACL re-rupture. One proposed mechanism involves the induction of excessive internal rotation of the tibia, which imposes abnormal stress on the reconstructed ligament and increases the risk of subsequent injury. Additionally, the uneven distribution of pressure across the lower-extremity joints may diminish muscular efficiency and ultimately lead to functional impairments and neuromuscular deficits [12].

Studies indicate that during forward dynamic activities such as running, the quadriceps muscles play a critical role in preventing unwanted movements and maintaining body balance [13]. An increase in the frequency spectrum of electromyographic (EMG) signals may reflect enhanced neuromuscular coordination and muscle efficiency. This change is likely due to the recruitment of more fast-twitch motor units, which can generate higher-frequency signals, thereby contributing to increased strength and improved muscular performance during activities like running [14]. Overall, an increase in muscle EMG frequency generally indicates heightened muscle activation or contraction intensity and is associated with the engagement of fast-twitch muscle fibers [15].

Muscle fatigue is a physiological phenomenon defined as a decrease in the muscle’s force-generating capacity. This condition leads to decreased contractile activity, impaired muscle coordination, and an overall decline in neuromuscular efficiency [16]. Fatigue can alter the patterns of muscle electrical activity, which may be associated with an increased risk of muscular injuries [17]. At the physiological level, fatigue is linked to impaired function of contractile proteins (actin and myosin) and depletion of energy-carrying molecules (e.g. adenosine triphosphate), ultimately resulting in compromised muscle performance and heightened susceptibility to injury [18].

One of the most common interventions for correcting lower-extremity movement patterns is the use of shoe insoles. Corrective movement specialists widely employ these devices to address FP, and studies have confirmed their significant effectiveness in reducing tibial internal rotation [19, 20]. Among the benefits of using insoles is the reduction of electrical activity in muscles responsible for controlling axial rotations and maintaining lower-extremity alignment. Therefore, compensating for FP with orthotic insoles can be a highly effective intervention [21]. Research has shown that in individuals with FP, the line of body weight application shifts medially, generating an evertor moment. In contrast, insoles with medial arch support redirect the load laterally and, by reducing center-of-pressure fluctuations, enhance balance in both static and dynamic conditions [22].

Although numerous studies have examined the effects of different insoles on muscle activity patterns or the influence of fatigue on muscle performance, no research has investigated the interactive effects of insole type and muscle fatigue on the frequency of muscle EMG activity in patients with ACLR-FP. These patients experience muscle fatigue and often use insoles during daily activities and sports. Understanding these interactive effects can help develop more precise rehabilitation protocols, optimize the prescription of assistive devices, such as insoles, and ultimately contribute to the prevention of ACL re-injury in this population.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a randomized clinical trial with a pretest-posttest design conducted at the Sports Biomechanics Laboratory of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. The study population consists of all male patients with ACLR-FP and healthy individuals in Ardabil province. To determine the minimum sample size, G*Power software, version 3.1 was used. By considering a significance level of 0.05, an effect size of 0.8, and a test power of 0.8 [23], the minimum sample size was determined to be 16. We selected 30 men (with ACLR and FP) and 10 healthy men, aged 18–45 years, using a convenience sampling method. Participants were divided into four groups: ACLR-FP men with <6 months post-ACLR (Group A), ACLR-FP men with 6–12 months post-ACLR (Group B), ACLR-FP men with >12 months post-ACLR (Group C), and healthy men (Group D). The right foot was identified as the dominant foot for all participants during a soccer kick test [24].

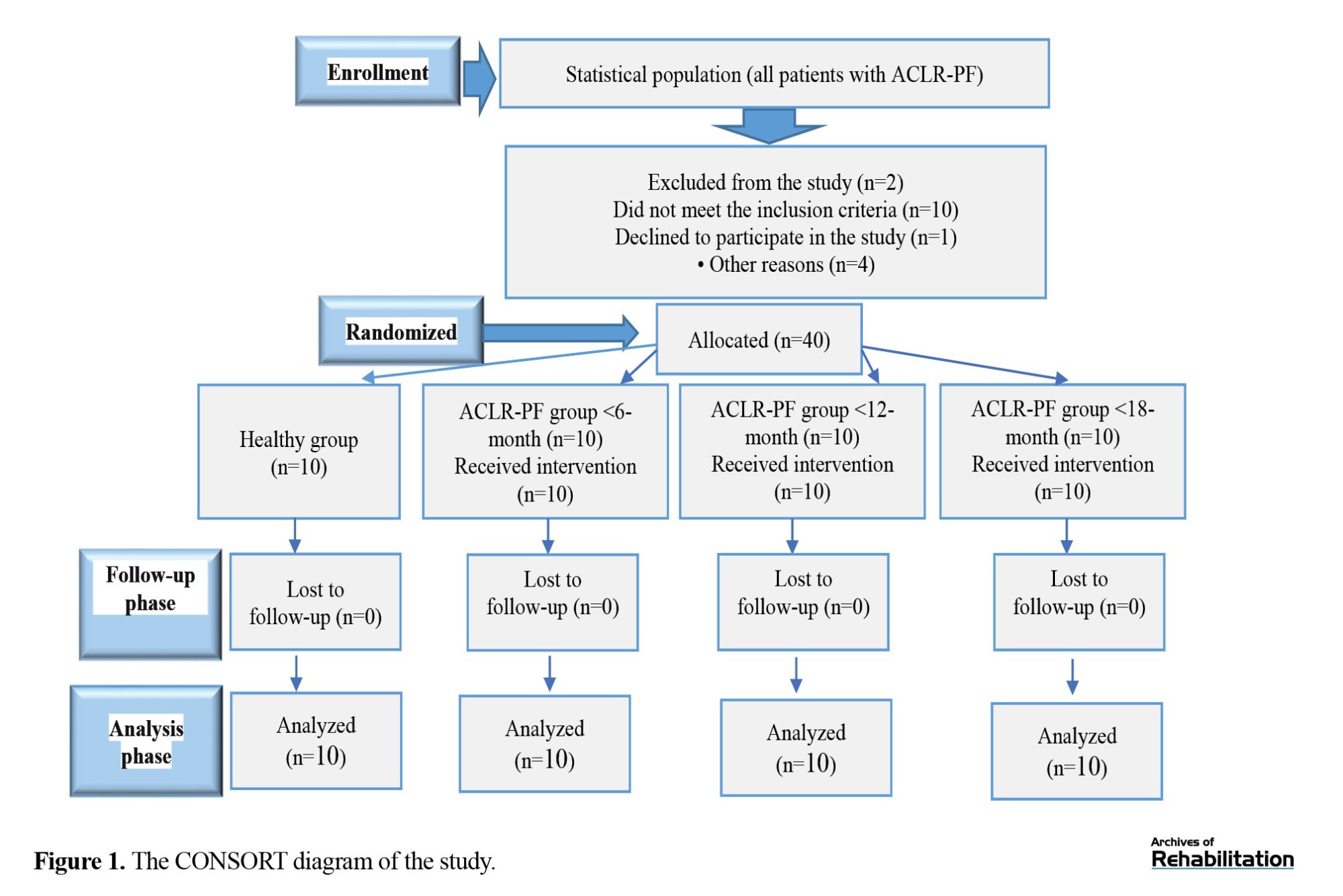

Inclusion criteria were: Having ACLR and FP, at least 6 months post-ACLR surgery, no pain during range of motion, ability to run without any limitations, willingness to participate in the study, age between 18–45 years, no other lower limb abnormalities such as genu varum, no long-term history of medication use affecting the musculoskeletal system, a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 25 kg/m², having a hamstring graft, a rearfoot deviation angle >4 degrees; a foot posture index >10 mm, and navicular drop greater than 1 cm. Exclusion criteria were lower-limb length asymmetry >5 mm and unwillingness to cooperate in the study. Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the sampling and group allocation processes.

Running, despite its well-established benefits for enhancing cardiorespiratory fitness and contributing to body type determination, carries a considerable risk of lower-extremity injury. Reports indicate that 2-38 injuries per 1,000 hours of running may occur [1]. Severe injuries such as complete rupture of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) generally require surgical intervention followed by a prolonged, structured rehabilitation program to restore knee joint stability and normal functional performance [2]. The concurrent presence of a pronation deformity (excessive foot inward rotation) alongside ACL rupture introduces significant clinical challenges, as the ACL plays a critical role in preventing anterior tibial translation relative to the femur and controlling knee internal rotation. Inadequate postoperative rehabilitation may lead to complications such as joint instability, reduced muscular strength, particularly in the quadriceps, altered movement patterns, and an increased risk of secondary injuries to the meniscus and articular cartilage [3, 4].

The prevalence of foot pronation (FP) is estimated to range from 48% to 78% in youth and from 20% to 23% in adults [5, 6]. In contrast, epidemiological data indicate that 30-70 new ACL injuries per 100,000 individuals occur annually in the general population. In the United States alone, more than 200,000 new ACL injuries are reported each year, and approximately 100,000 ACL reconstruction (ACLR) surgeries are performed [7]. FP is a structural abnormality characterized by a reduced medial longitudinal arch and altered alignment of the ankle joint [8].

Multiple surgical techniques are available for ACLR; their choice depends on the injury severity and the patient’s functional goals. These techniques involve grafts harvested from the hamstring tendons, the patellar tendon, the quadriceps tendon, or the Achilles tendon. When selecting a graft type, key considerations include the individual’s activity level, the biological compatibility of the transplanted tissue, and its mechanical strength in resisting re-injury or graft failure [9]. Recent studies indicate that the rate of ACLR failure ranges from 5% to 25%, influenced by factors such as inadequate rehabilitation, premature return to sport, muscular weakness, and insufficient graft fixation, with the highest risk of reinjury occurring within the first two postoperative years [10, 11]. FP is recognized as an independent risk factor for ACL re-rupture. One proposed mechanism involves the induction of excessive internal rotation of the tibia, which imposes abnormal stress on the reconstructed ligament and increases the risk of subsequent injury. Additionally, the uneven distribution of pressure across the lower-extremity joints may diminish muscular efficiency and ultimately lead to functional impairments and neuromuscular deficits [12].

Studies indicate that during forward dynamic activities such as running, the quadriceps muscles play a critical role in preventing unwanted movements and maintaining body balance [13]. An increase in the frequency spectrum of electromyographic (EMG) signals may reflect enhanced neuromuscular coordination and muscle efficiency. This change is likely due to the recruitment of more fast-twitch motor units, which can generate higher-frequency signals, thereby contributing to increased strength and improved muscular performance during activities like running [14]. Overall, an increase in muscle EMG frequency generally indicates heightened muscle activation or contraction intensity and is associated with the engagement of fast-twitch muscle fibers [15].

Muscle fatigue is a physiological phenomenon defined as a decrease in the muscle’s force-generating capacity. This condition leads to decreased contractile activity, impaired muscle coordination, and an overall decline in neuromuscular efficiency [16]. Fatigue can alter the patterns of muscle electrical activity, which may be associated with an increased risk of muscular injuries [17]. At the physiological level, fatigue is linked to impaired function of contractile proteins (actin and myosin) and depletion of energy-carrying molecules (e.g. adenosine triphosphate), ultimately resulting in compromised muscle performance and heightened susceptibility to injury [18].

One of the most common interventions for correcting lower-extremity movement patterns is the use of shoe insoles. Corrective movement specialists widely employ these devices to address FP, and studies have confirmed their significant effectiveness in reducing tibial internal rotation [19, 20]. Among the benefits of using insoles is the reduction of electrical activity in muscles responsible for controlling axial rotations and maintaining lower-extremity alignment. Therefore, compensating for FP with orthotic insoles can be a highly effective intervention [21]. Research has shown that in individuals with FP, the line of body weight application shifts medially, generating an evertor moment. In contrast, insoles with medial arch support redirect the load laterally and, by reducing center-of-pressure fluctuations, enhance balance in both static and dynamic conditions [22].

Although numerous studies have examined the effects of different insoles on muscle activity patterns or the influence of fatigue on muscle performance, no research has investigated the interactive effects of insole type and muscle fatigue on the frequency of muscle EMG activity in patients with ACLR-FP. These patients experience muscle fatigue and often use insoles during daily activities and sports. Understanding these interactive effects can help develop more precise rehabilitation protocols, optimize the prescription of assistive devices, such as insoles, and ultimately contribute to the prevention of ACL re-injury in this population.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a randomized clinical trial with a pretest-posttest design conducted at the Sports Biomechanics Laboratory of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. The study population consists of all male patients with ACLR-FP and healthy individuals in Ardabil province. To determine the minimum sample size, G*Power software, version 3.1 was used. By considering a significance level of 0.05, an effect size of 0.8, and a test power of 0.8 [23], the minimum sample size was determined to be 16. We selected 30 men (with ACLR and FP) and 10 healthy men, aged 18–45 years, using a convenience sampling method. Participants were divided into four groups: ACLR-FP men with <6 months post-ACLR (Group A), ACLR-FP men with 6–12 months post-ACLR (Group B), ACLR-FP men with >12 months post-ACLR (Group C), and healthy men (Group D). The right foot was identified as the dominant foot for all participants during a soccer kick test [24].

Inclusion criteria were: Having ACLR and FP, at least 6 months post-ACLR surgery, no pain during range of motion, ability to run without any limitations, willingness to participate in the study, age between 18–45 years, no other lower limb abnormalities such as genu varum, no long-term history of medication use affecting the musculoskeletal system, a body mass index (BMI) between 18.5 and 25 kg/m², having a hamstring graft, a rearfoot deviation angle >4 degrees; a foot posture index >10 mm, and navicular drop greater than 1 cm. Exclusion criteria were lower-limb length asymmetry >5 mm and unwillingness to cooperate in the study. Figure 1 presents the flowchart of the sampling and group allocation processes.

Throughout all stages of the study, research ethics were observed, and informed consent was obtained from all participants [25].

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration [26]. All participants were requested to refrain from intense physical activity 48 hours before the test. This precaution ensured that only the effect of acute, standardized laboratory-induced fatigue (under uniform conditions) would be examined [27, 28].

Data collection and protocols

Participants performed the running task on an 18-meter path towards the laboratory after electrode placement on the muscles. Each condition was recorded with three correct trials. To control and monitor running speed (3.2 m/s), two sets of infrared beam sensors (Wellsway, Australia) were used [3]. To familiarize themselves with the path, participants ran three times before data collection. To compare the potential effect of running speed and control it during data analysis, each individual’s running speed was monitored with a speedometer to ensure no variations in speed across trials. Three trials were performed under each condition. The trial was discarded if the data were incomplete or noisy, if the participant lost balance during the trial, or if the participant ran with an atypical pattern. It should be noted that a trial was considered correct only if the EMG signal from all muscles was recorded properly [29].

Muscle activity from the right leg was recorded during running for the following muscles: Tibialis anterior (TA), gastrocnemius (GC), vastus medialis (VM), vastus lateralis (VL), rectus femoris (RF), biceps femoris (BF), semitendinosus (ST), and gluteus medius (GM). To record muscle electrical activity, an 8-channel wireless EMG system (Biometrics Ltd, UK) with bipolar surface electrodes (circular Ag/AgCl electrode pairs with a diameter of 11 mm; inter-electrode distance of 25 mm, input impedance of 100 MΩ, common mode rejection ratio >110 dB at 50-60 Hz) was used. For filtering the raw EMG data, a low-pass filter of 500 Hz, a high-pass filter of 10 Hz, and a notch filter (to remove mains electricity noise) of 60 Hz were selected [30]. The sampling rate for muscle EMG activity was set at 1000 Hz. The location of the selected muscles and preparatory procedures, such as shaving the electrode site and cleaning with 70% alcohol (C₂H₅OH), were performed according to the Surface Electromyography (EMG) for the non-invasive assessment of muscles (SENIAM) recommendations [31, 32].

Participants from all four groups ran the path at pre-fatigue and post-fatigue stages under four conditions: Control shoe, placebo insole, arch support insole, and double-density insole. Different sizes of insoles were available for each type. The arch support insole (Figure 2) had a medial wedge.

All procedures were conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration [26]. All participants were requested to refrain from intense physical activity 48 hours before the test. This precaution ensured that only the effect of acute, standardized laboratory-induced fatigue (under uniform conditions) would be examined [27, 28].

Data collection and protocols

Participants performed the running task on an 18-meter path towards the laboratory after electrode placement on the muscles. Each condition was recorded with three correct trials. To control and monitor running speed (3.2 m/s), two sets of infrared beam sensors (Wellsway, Australia) were used [3]. To familiarize themselves with the path, participants ran three times before data collection. To compare the potential effect of running speed and control it during data analysis, each individual’s running speed was monitored with a speedometer to ensure no variations in speed across trials. Three trials were performed under each condition. The trial was discarded if the data were incomplete or noisy, if the participant lost balance during the trial, or if the participant ran with an atypical pattern. It should be noted that a trial was considered correct only if the EMG signal from all muscles was recorded properly [29].

Muscle activity from the right leg was recorded during running for the following muscles: Tibialis anterior (TA), gastrocnemius (GC), vastus medialis (VM), vastus lateralis (VL), rectus femoris (RF), biceps femoris (BF), semitendinosus (ST), and gluteus medius (GM). To record muscle electrical activity, an 8-channel wireless EMG system (Biometrics Ltd, UK) with bipolar surface electrodes (circular Ag/AgCl electrode pairs with a diameter of 11 mm; inter-electrode distance of 25 mm, input impedance of 100 MΩ, common mode rejection ratio >110 dB at 50-60 Hz) was used. For filtering the raw EMG data, a low-pass filter of 500 Hz, a high-pass filter of 10 Hz, and a notch filter (to remove mains electricity noise) of 60 Hz were selected [30]. The sampling rate for muscle EMG activity was set at 1000 Hz. The location of the selected muscles and preparatory procedures, such as shaving the electrode site and cleaning with 70% alcohol (C₂H₅OH), were performed according to the Surface Electromyography (EMG) for the non-invasive assessment of muscles (SENIAM) recommendations [31, 32].

Participants from all four groups ran the path at pre-fatigue and post-fatigue stages under four conditions: Control shoe, placebo insole, arch support insole, and double-density insole. Different sizes of insoles were available for each type. The arch support insole (Figure 2) had a medial wedge.

The peak height of the medial longitudinal arch in this insole was 25 mm, with a posting (maximum height difference between the medial and lateral wedges) of 15 mm. The length of this insole was designed to cover the rearfoot and midfoot, without extending into the forefoot. It was made of rigid polyurethane and provided full arch coverage. An insole of the appropriate size was used for each participant based on their foot measurements. The placebo insoles (Figure 3) were standard, commercially available type.

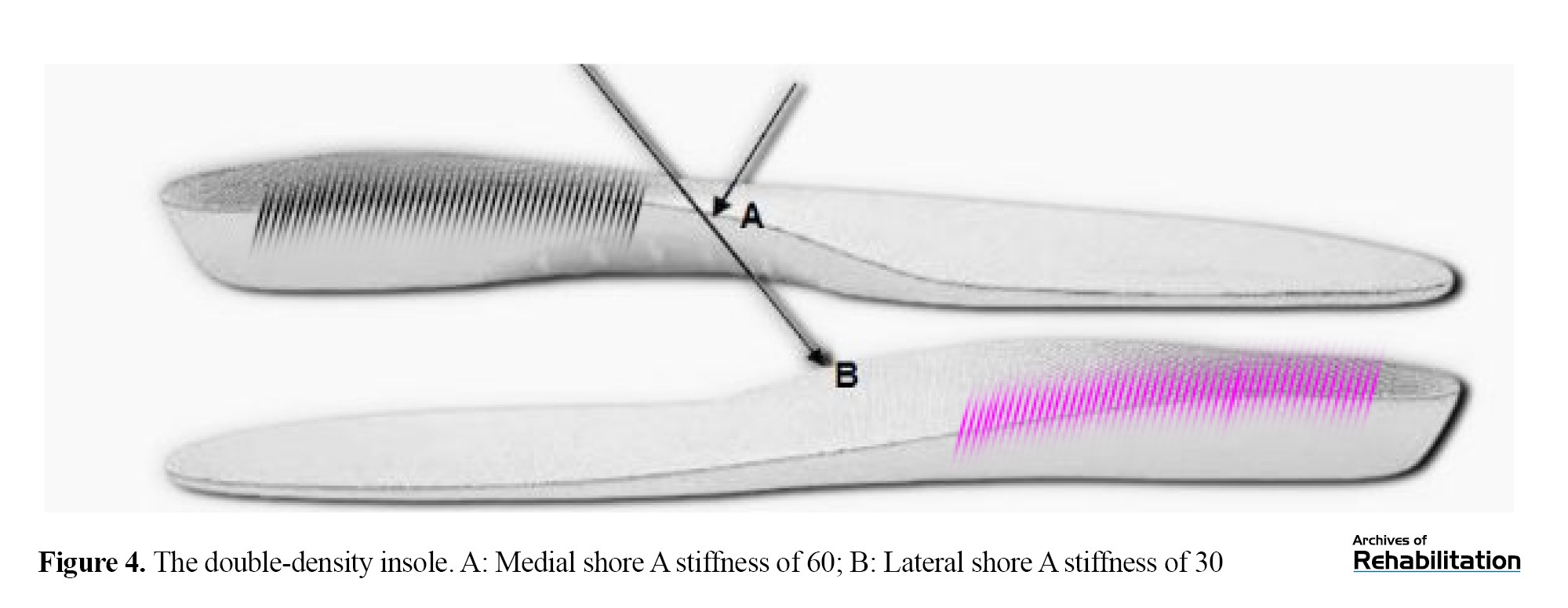

To standardize data collection conditions, control shoes in various sizes were used for all groups. The double-density insole (Figure 4) was made of ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), with a medial Shore A hardness of 60 and a lateral Shore A hardness of 30, while maintaining the elevated support for the medial longitudinal arch.

The double-density insole had varied stiffness in the heel pad region and an 8-degree medial-to-lateral incline. Due to its intentionally varied stiffness, this insole may have distinct effects on the attenuation and release of ground reaction forces during running mechanics. A key distinguishing feature of this insole type was its approach to addressing the height discrepancy between the medial and lateral sides, an aspect overlooked in some previous studies, which can potentially induce minor alterations in movement patterns from a biomechanical perspective [33].

The fatigue protocol was performed on an advanced treadmill (Horizon Fitness, Omega GT, USA) at zero incline. At the start of the protocol, participants began walking at 6 km/h, and the speed increased by 1 km/h every 2 minutes. Borg’s rate of perceived exertion (RPE) scale of 6–20 was used to determine the final level of fatigue for each participant [34]. Once participants reported a perceived exertion rating of 13 or higher, the treadmill speed was held constant to allow for steady-state running. During the steady-state phase, the perceived exertion score was assessed every 30 seconds. The fatigue protocol was terminated after two minutes of steady-state running when the RPE scale score was above 17, or upon reaching 80% of maximum heart rate [35].

Statistical analysis

Normality of the data distribution was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Homogeneity of variances was confirmed using Levene’s test (P>0.05). A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed for data analysis. All analyses were performed in SPSS software, version 23, considering a significance level at P<0.05.

Results

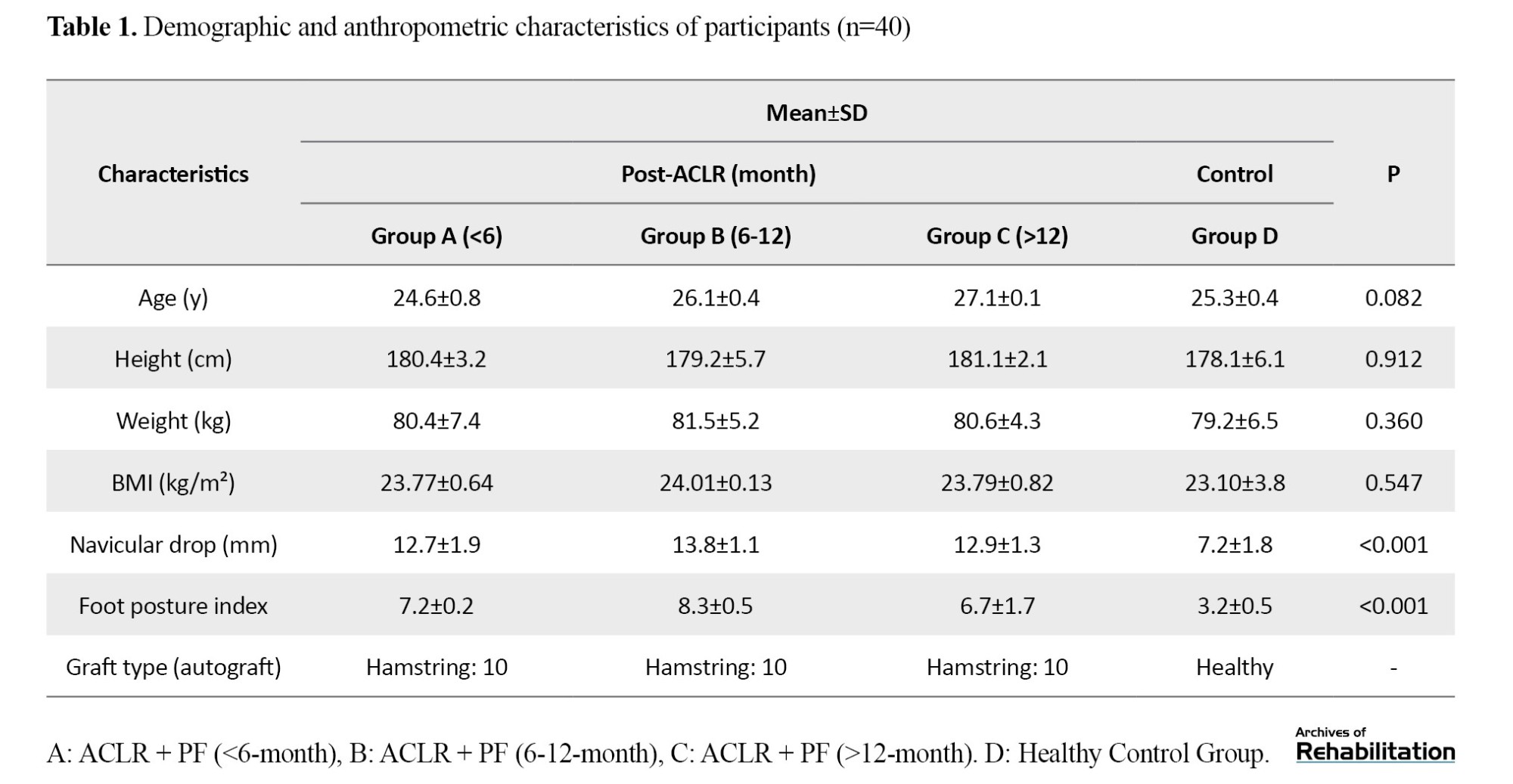

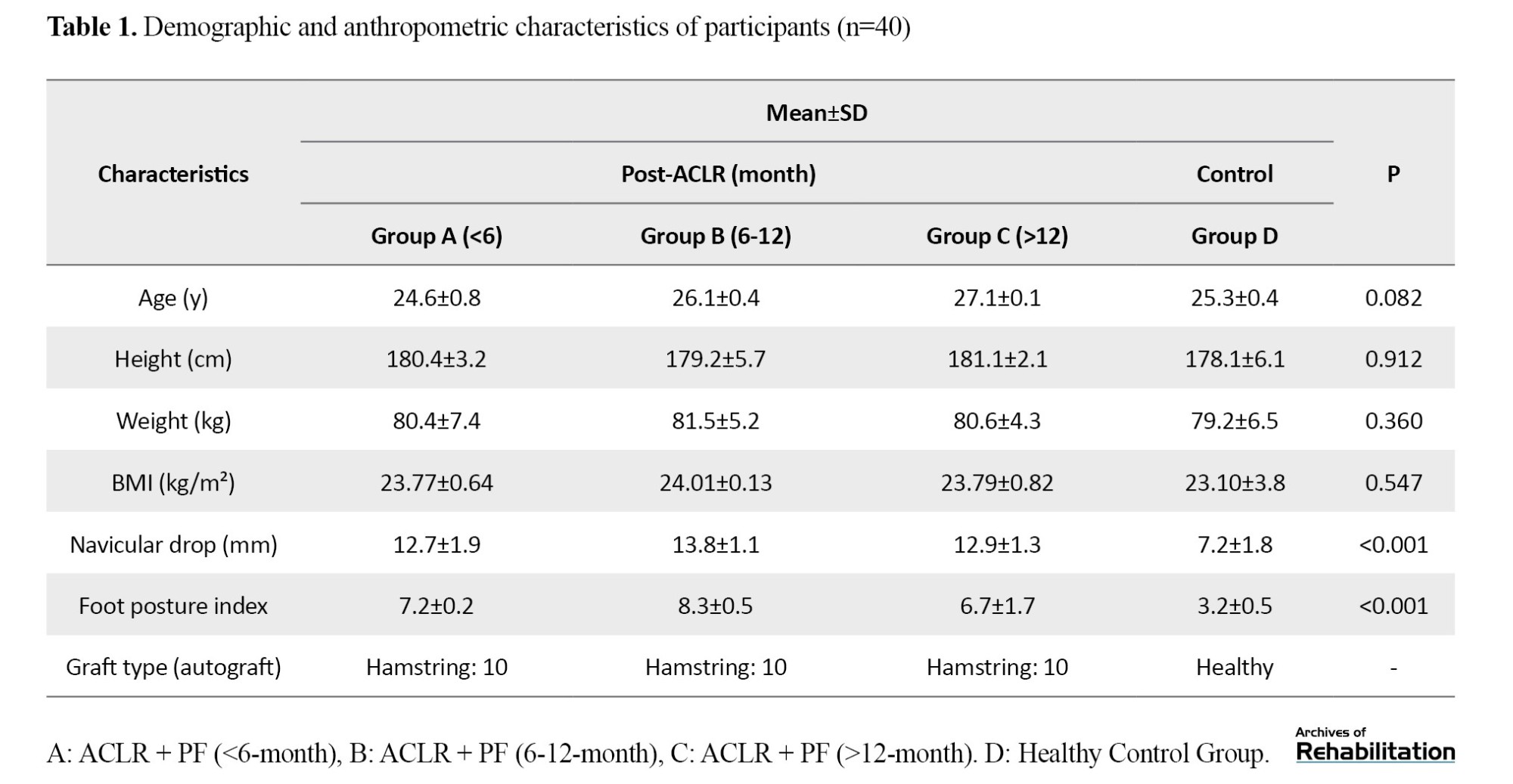

The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

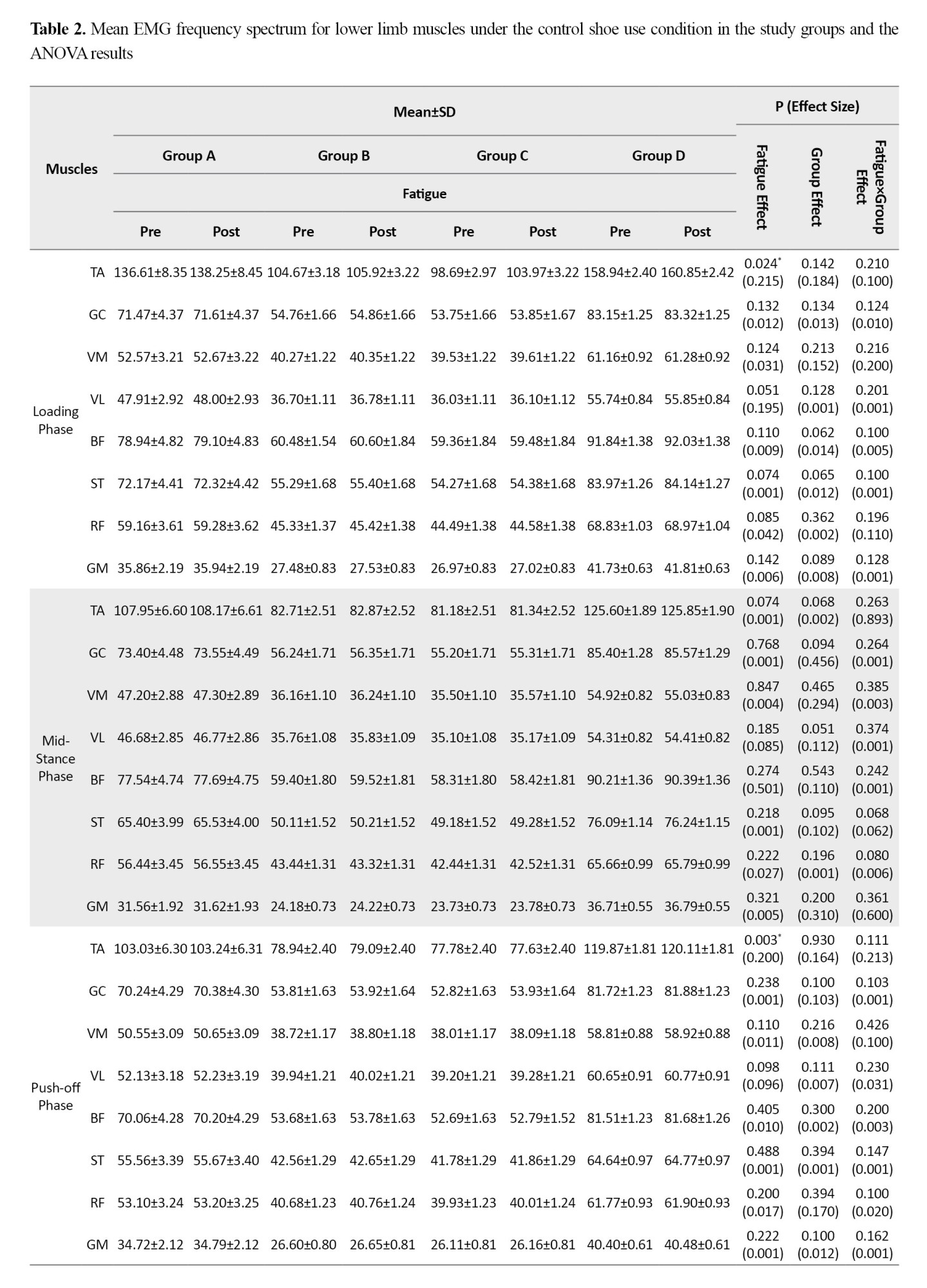

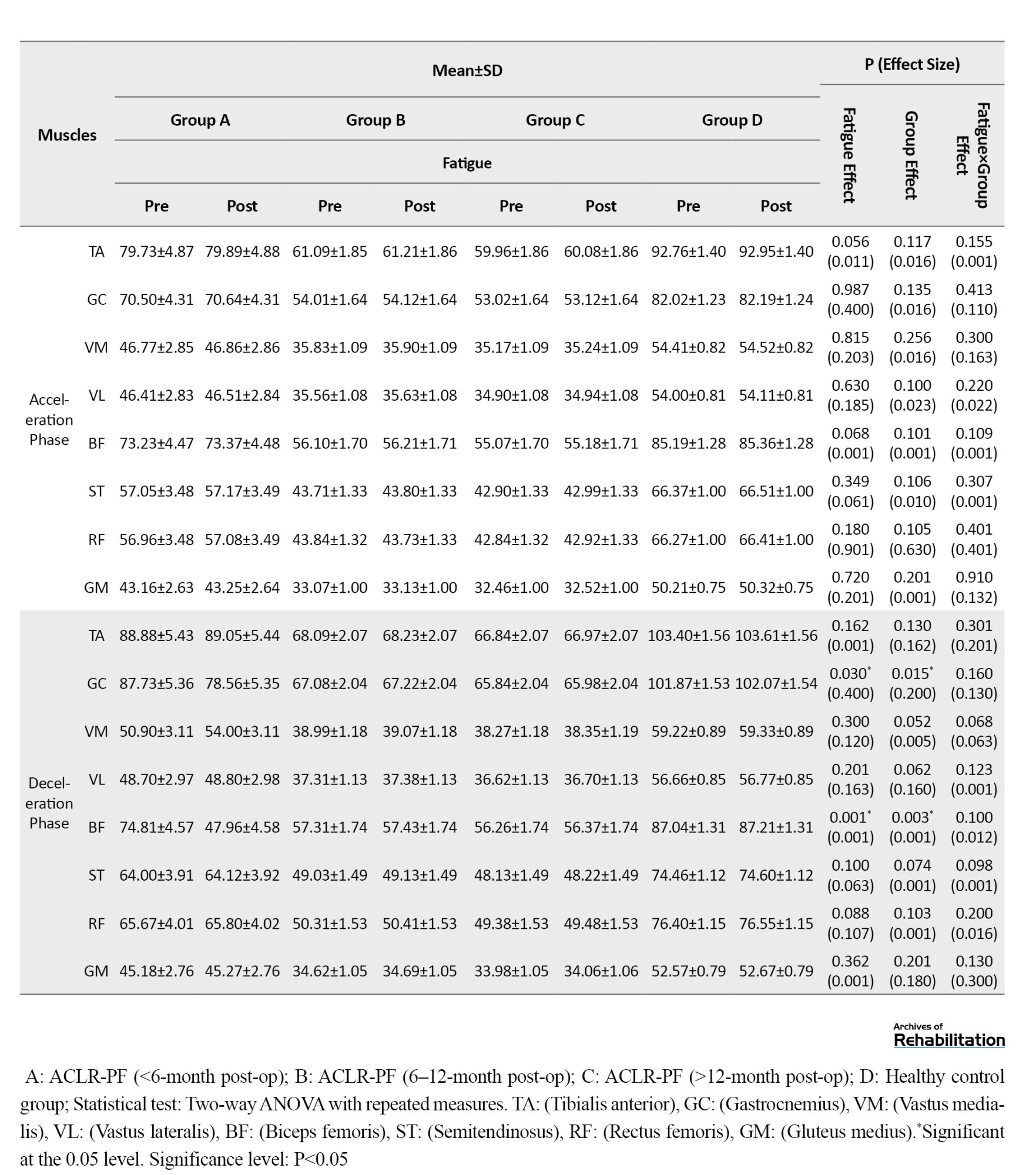

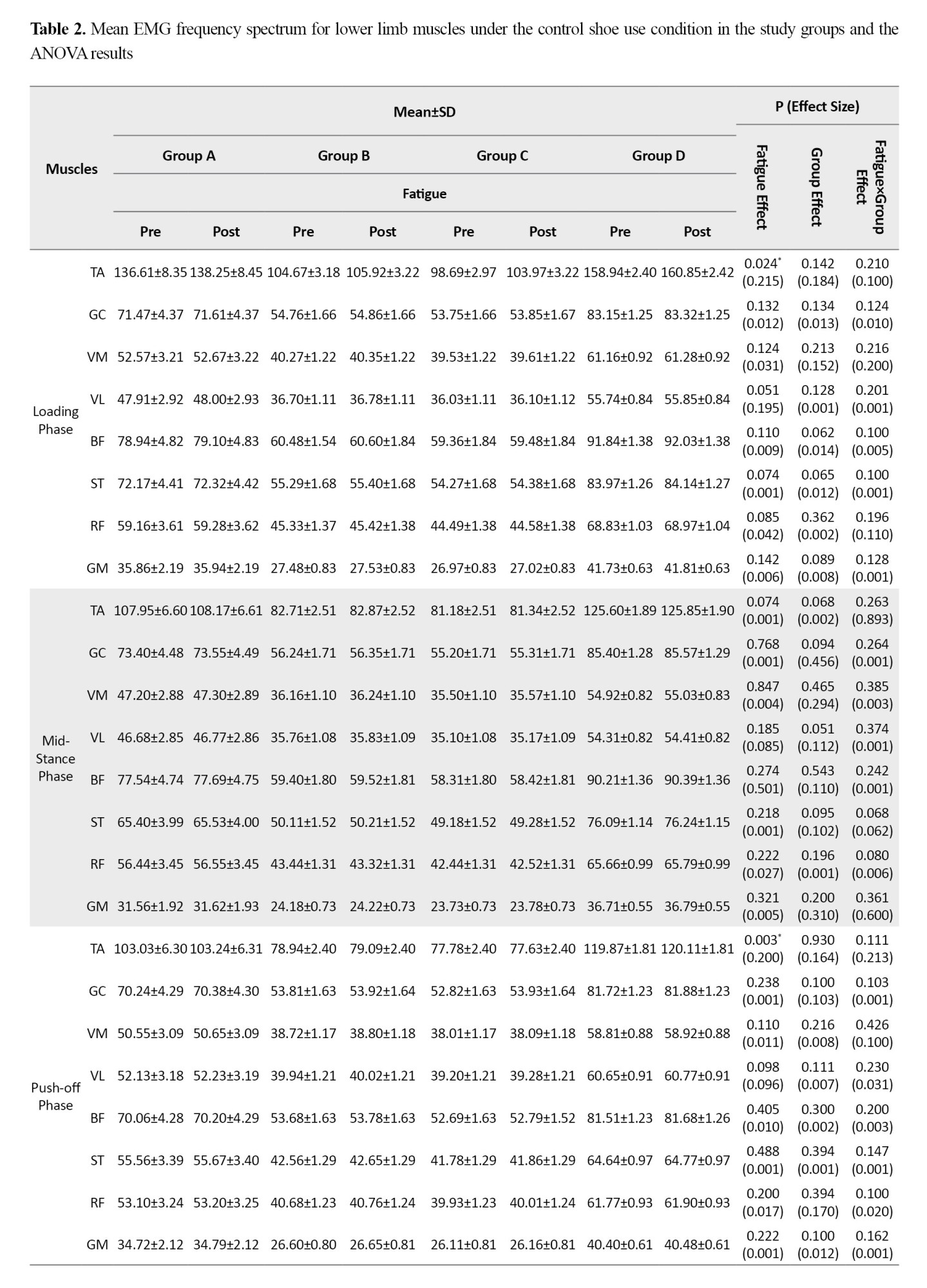

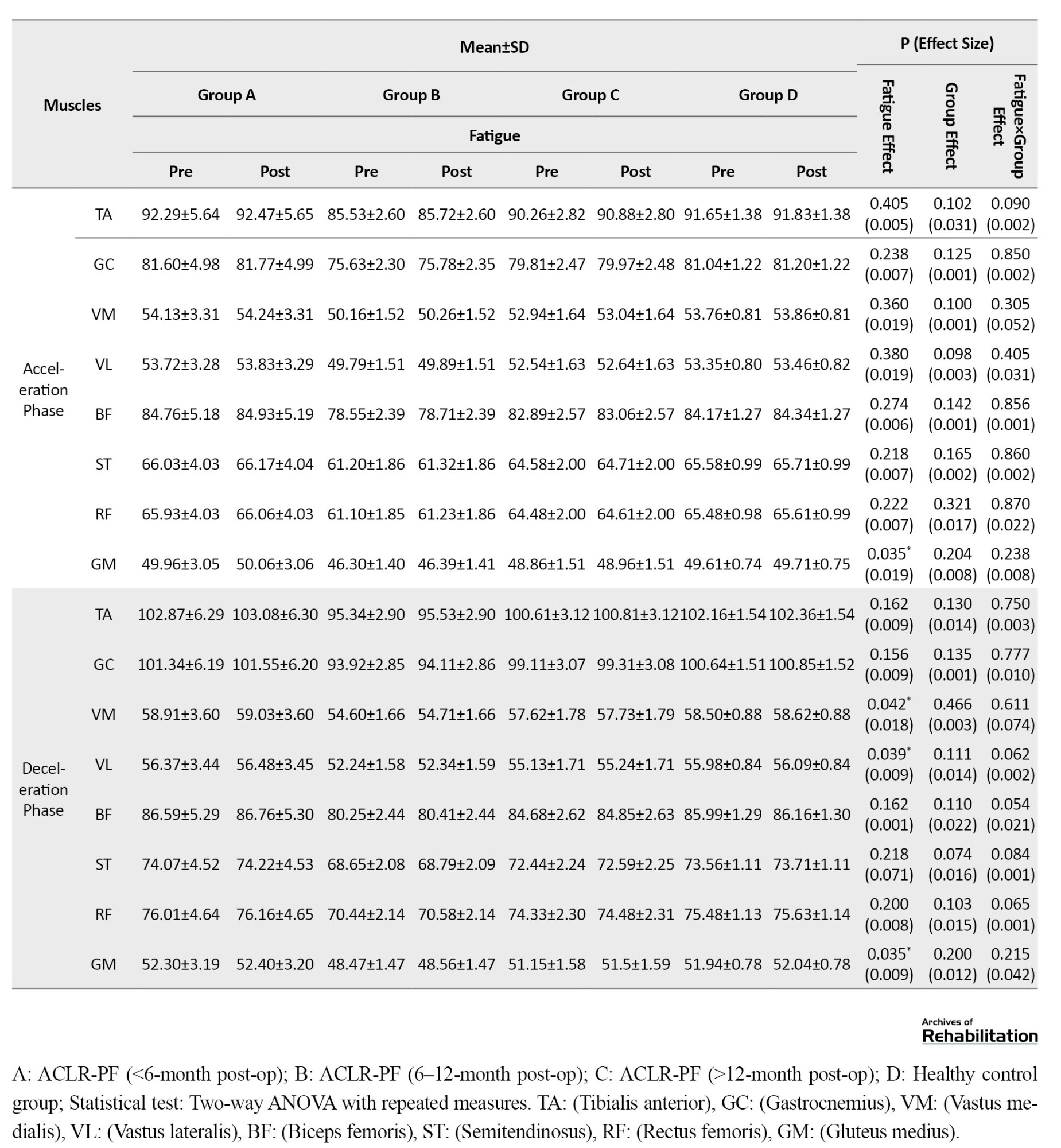

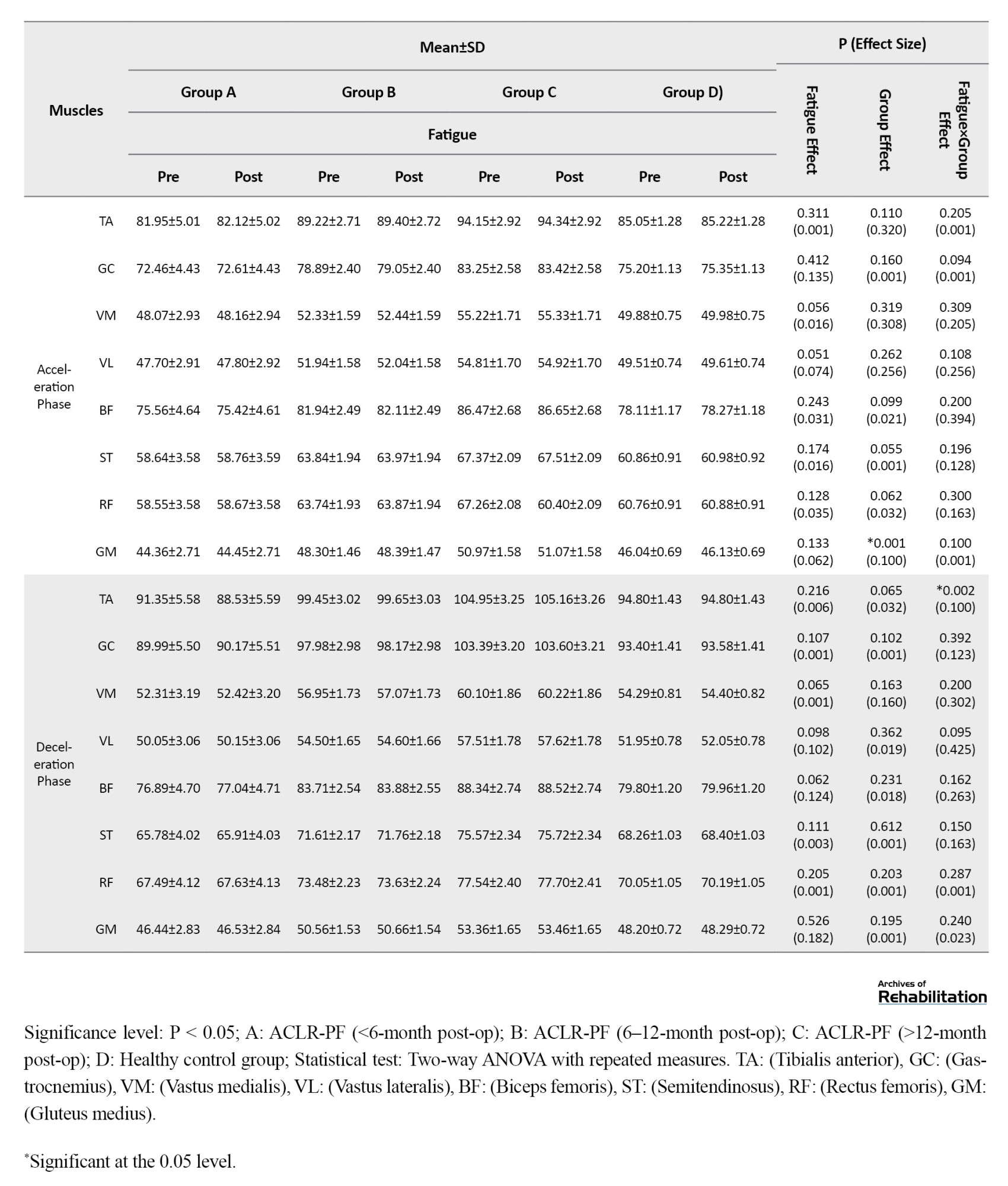

The frequency spectrum of the EMG activity for the lower limb muscles across different running phases showed no significant differences between the study groups in the pre-test stage (P>0.05). According to the results in Table 2, under the control shoe use condition, the effect of the fatigue factor was statistically significant for the TA muscle during the loading response (Effect size (d)=0.215; P=0.024) and the push-off phase (d=0.200; P=0.003).

The effect of fatigue was also statistically significant for the GC (d=0.400; P=0.030) and BF (d=0.001; P=0.001) muscles during the deceleration phase. Furthermore, the group factor showed a significant effect on EMG frequency spectrum for the GC (d=0.200; P=0.015) and BF (d=0.001; P=0.003) muscles during the deceleration phase. The findings revealed no significant interaction effect of fatigue and group on the EMG activity of lower limb muscles across any running phases when control shoes were used.

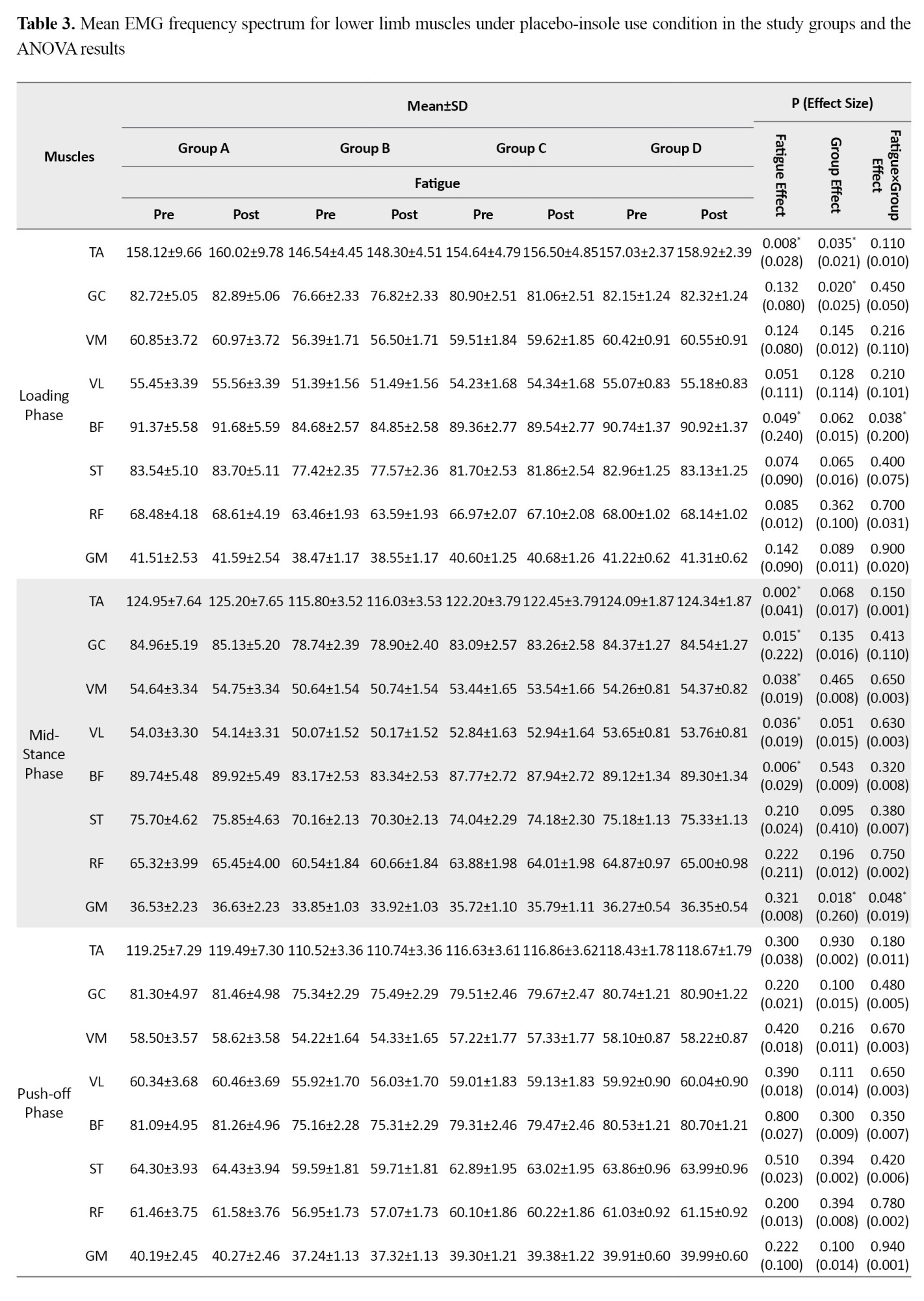

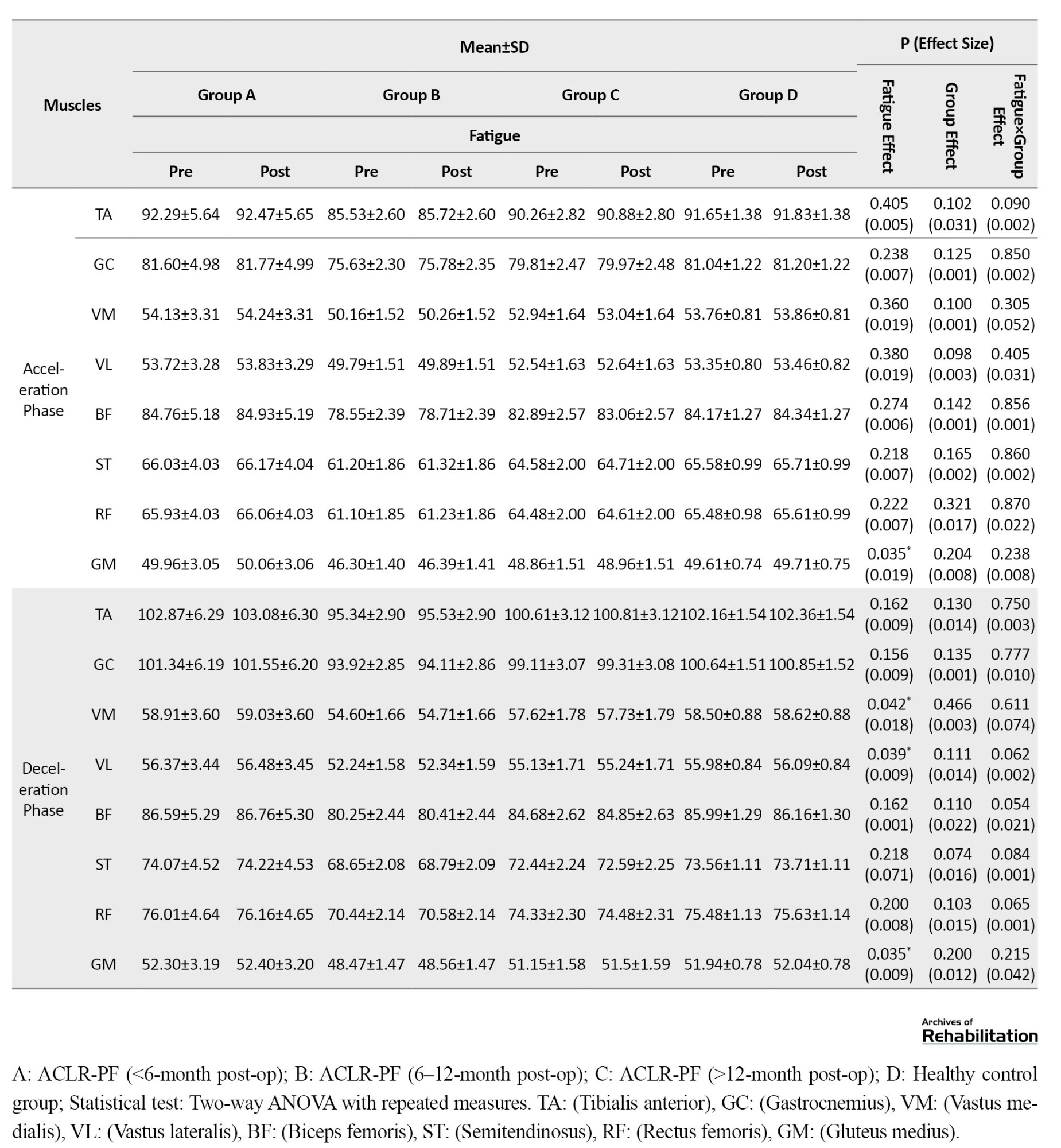

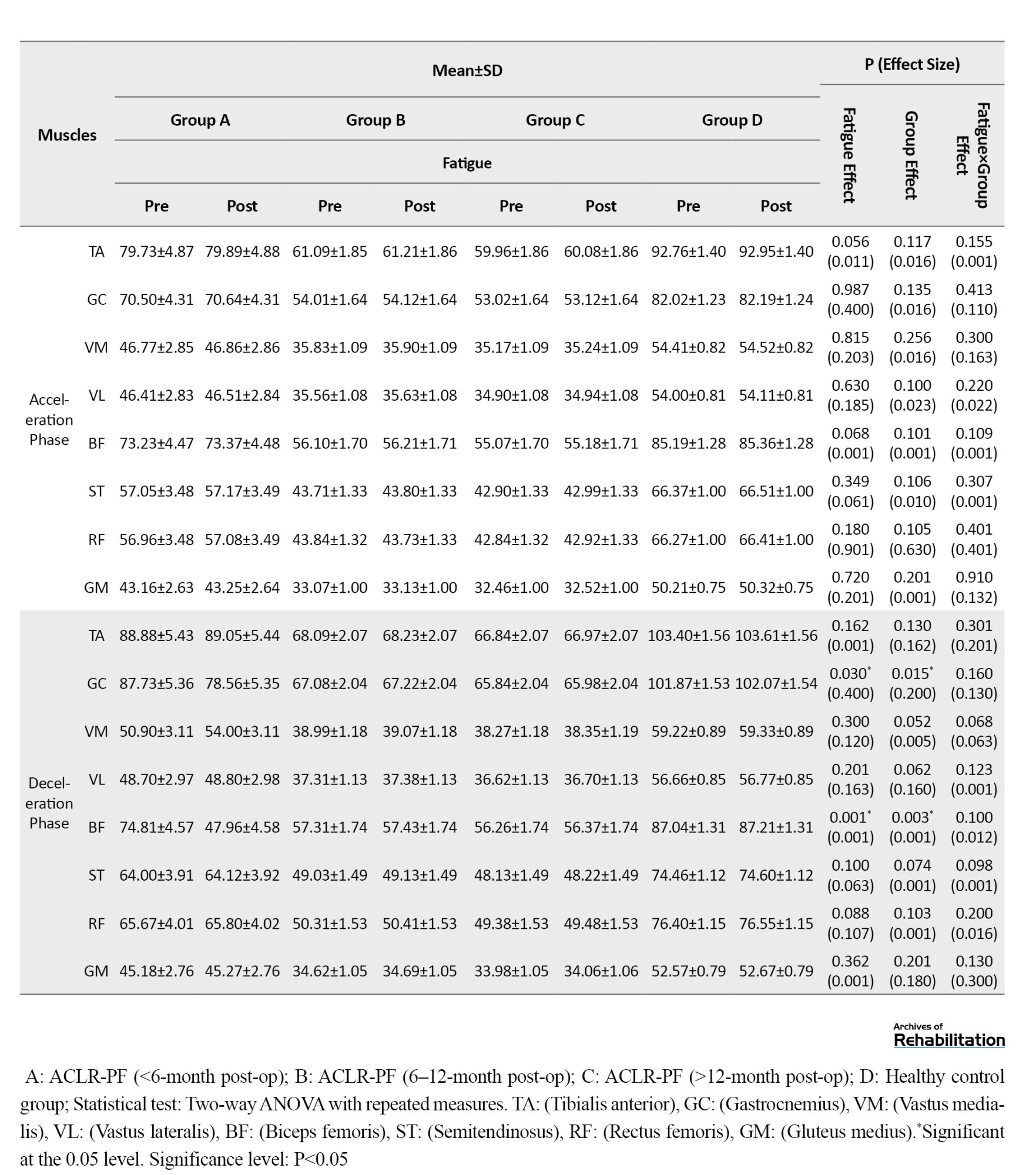

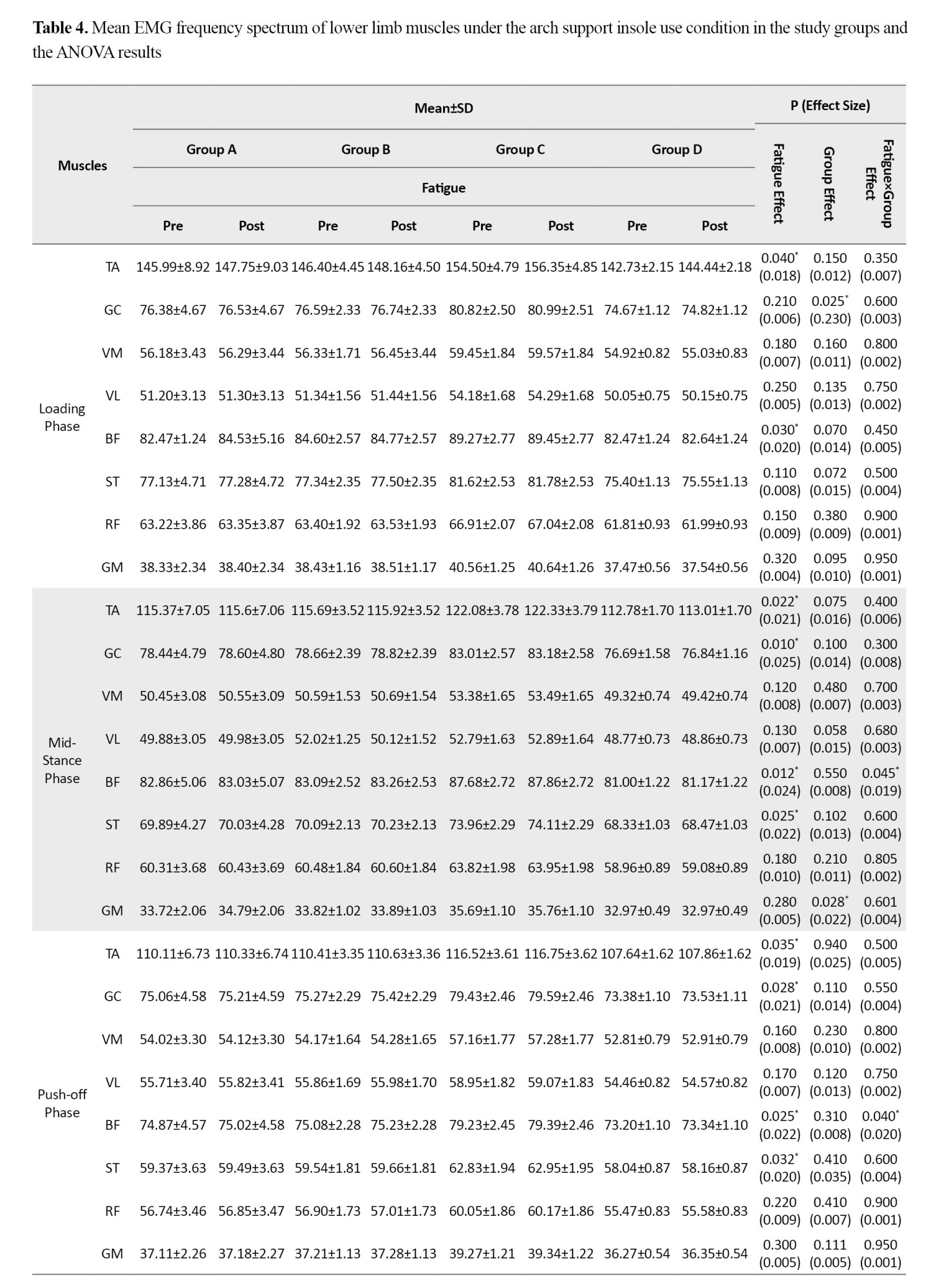

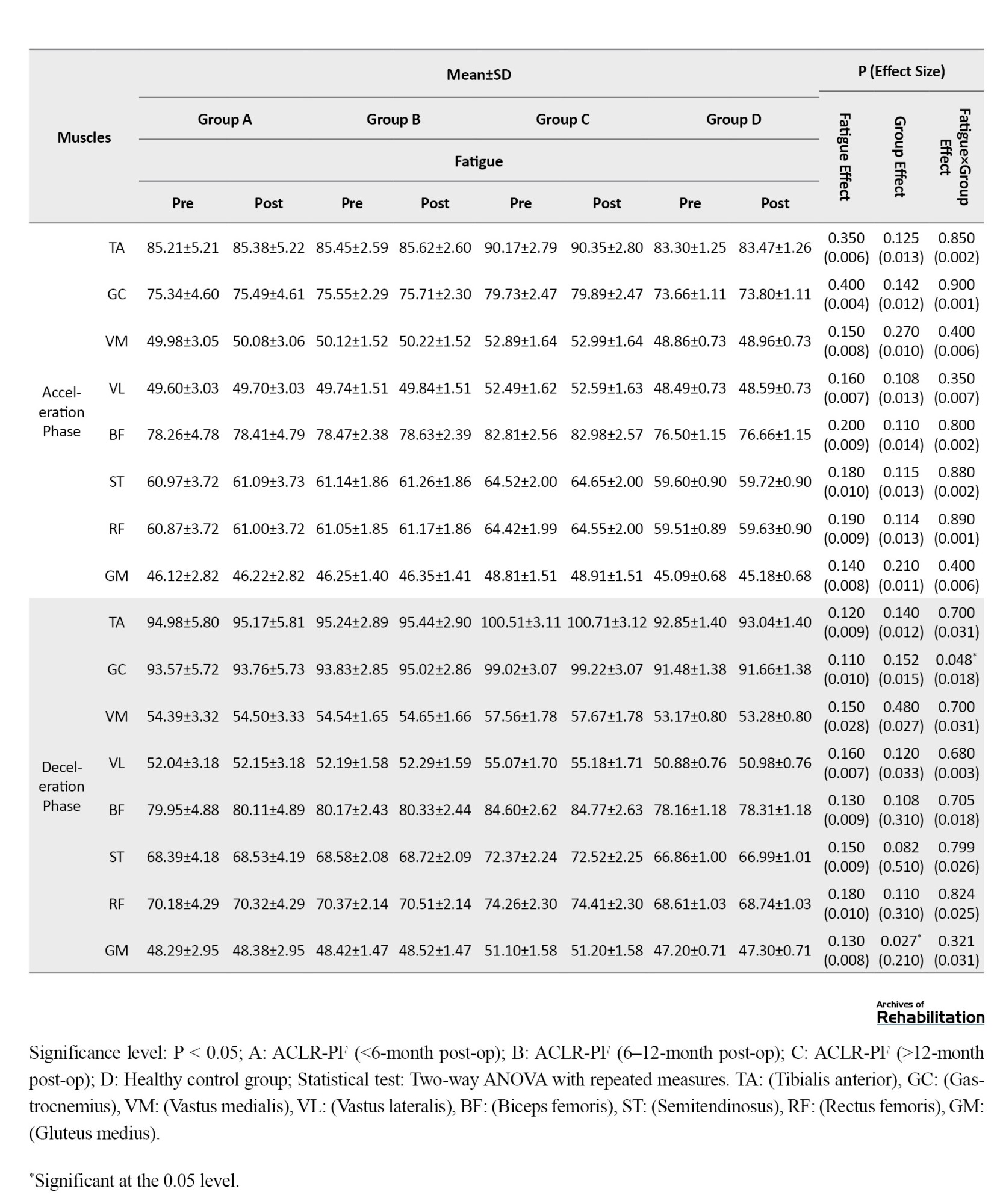

Based on the results in Table 3, when running with placebo insoles, the effect of the fatigue factor was statistically significant for the TA (d=0.028, P=0.008) and BF (d=0.240, P=0.049) muscles during the loading phase.

Significant fatigue effects were also observed during the mid-stance phase for the TA (d=0.041, P=0.002), GC (d=0.222, P=0.015), VM (d=0.019, P=0.038), VL (d=0.019, P=0.036), and BF (d=0.029, P=0.006); during the deceleration phase for the VM (d=0.018, P=0.042), VL (d=0.009, P=0.039), and GM (d=0.009, P=0.035); and during the acceleration phase for the GM (d=0.019, P=0.035). Furthermore, the group factor effect was statistically significant for the TA (d=0.021, P=0.035) and GC (d=0.025, P=0.020) during the loading phase, and for the GM during the mid-stance phase (d=0.260, P=0.018). The findings revealed a significant fatigue×group interaction effect for the BF during the loading phase (d=0.200, P=0.038) and for the GM during the mid-stance phase (d=0.019, P=0.048). Post-hoc test results indicated that the highest rate of increase was observed in the <6-month post-ACLR group compared to the other groups.

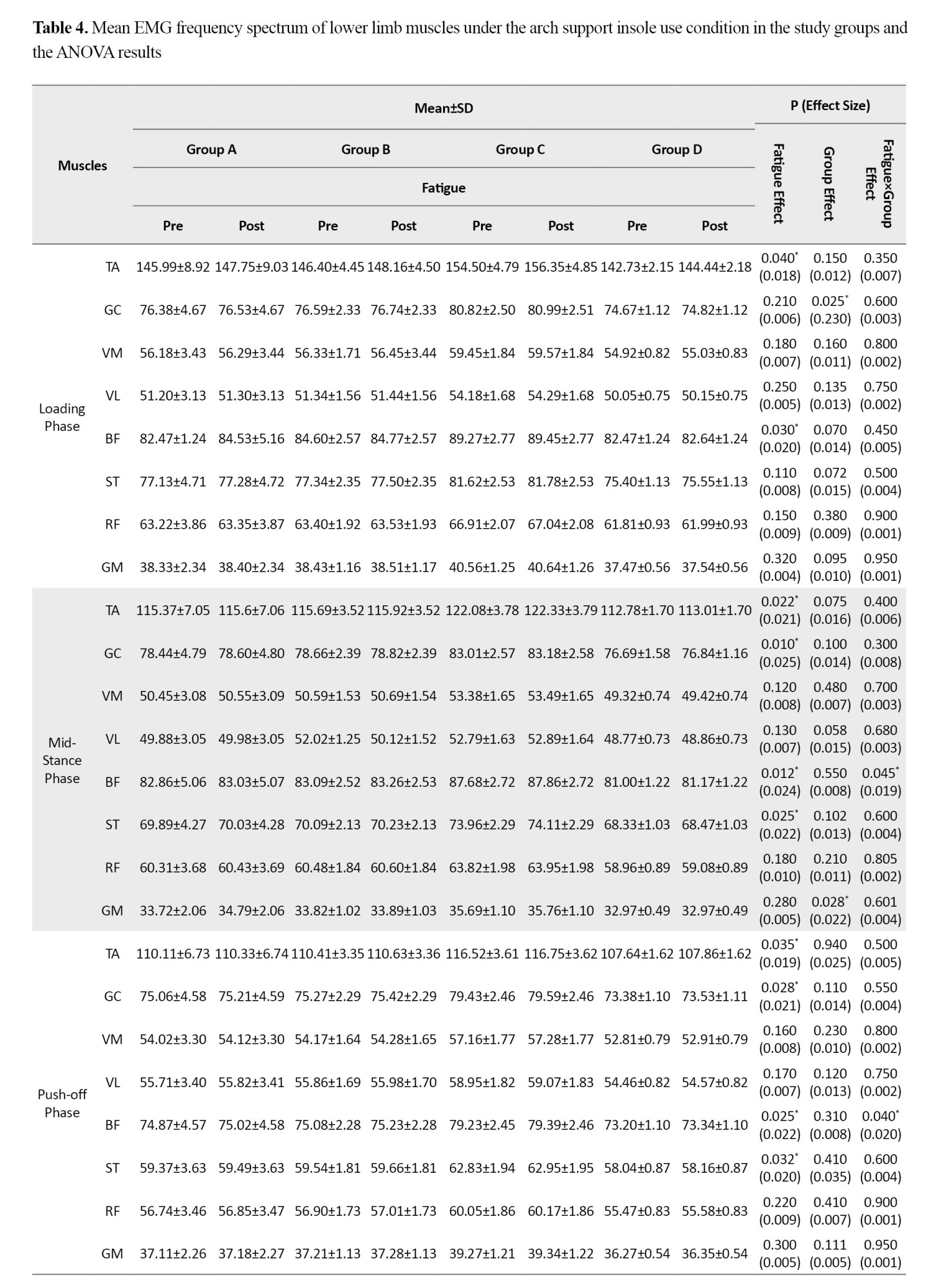

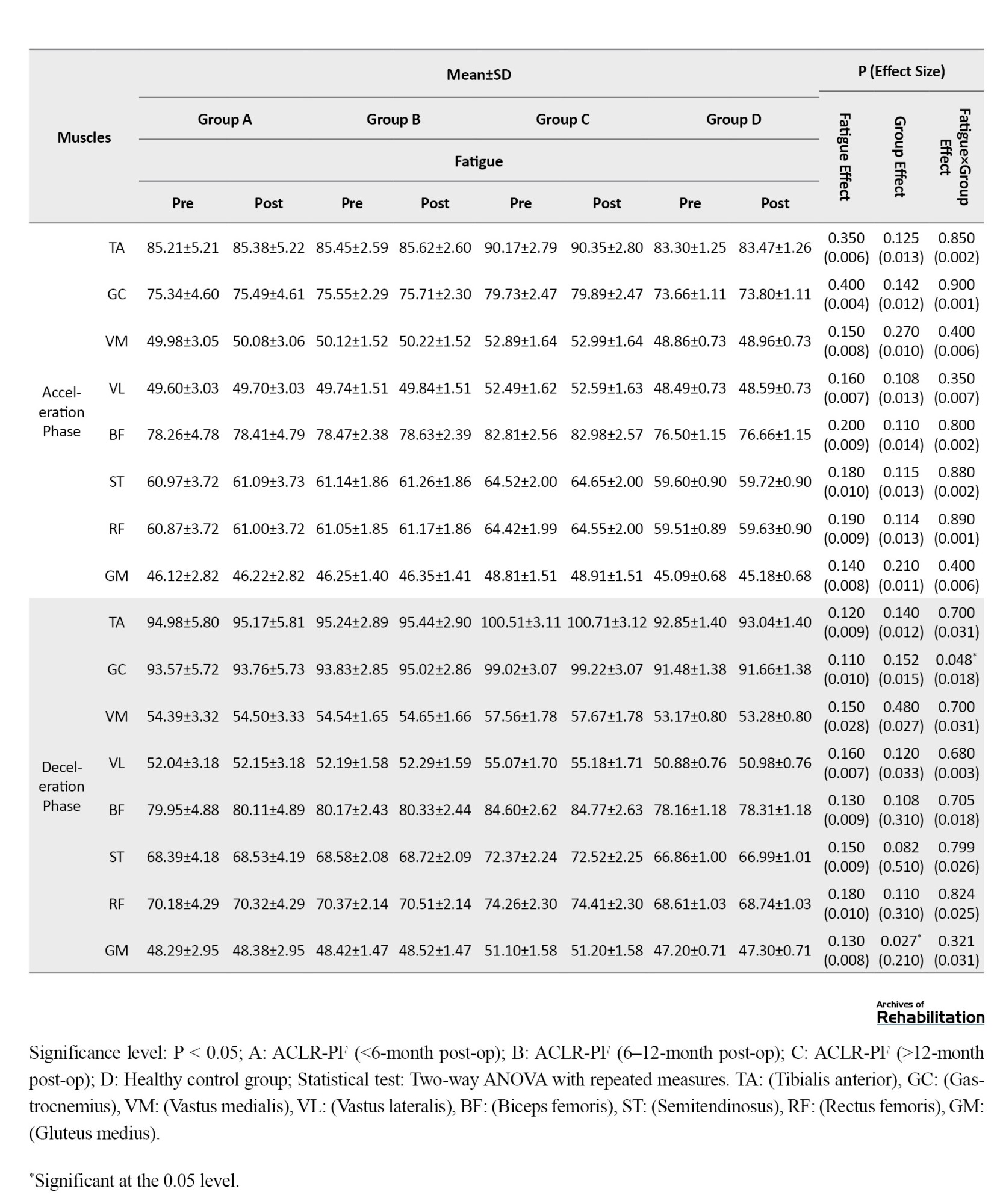

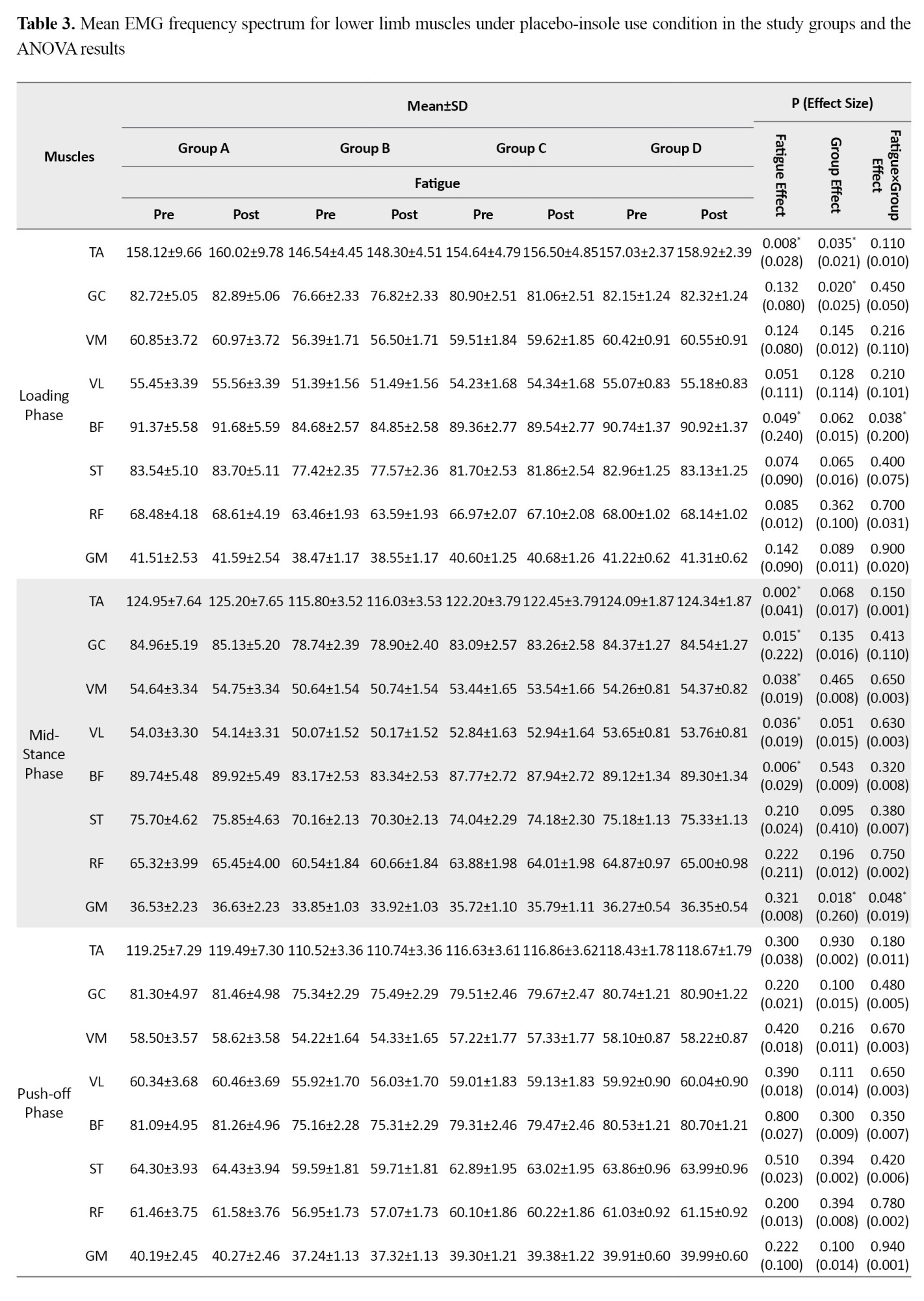

Based on the results in Table 4, when running with arch support insoles, the effect of fatigue factor was statistically significant for the TA (d=0.018, P=0.040) and BF (d=0.020, P=0.030) muscles during the loading phase.

During the mid-stance phase, significant fatigue effects were observed for the TA (d=0.021, P=0.022), GC (d=0.025, P=0.010), BF (d=0.024, P=0.012), and ST (d=0.022, P=0.025). Furthermore, during the push-off phase, significant fatigue effects were found for the TA (d=0.019, P=0.035), GC (d=0.021, P=0.028), BF (d=0.022, P=0.025), and ST (d=0.020, P=0.032). Additionally, the group factor effect was statistically significant for the GC during the loading phase (d=0.230, P=0.025), and for the GM during both the mid-stance phase (d=0.022, P=0.028) and the deceleration phase (d=0.210, P=0.027). The findings revealed a significant fatigue×group interaction effect for the BF, which showed a significant increase during both mid-stance (d=0.019, P=0.045) and push-off (d=0.020, P=0.040) phases. A significant interaction effect was also observed for the GC during the deceleration phase (d=0.018, P=0.048). Post-hoc test results indicated that the highest rate of increase in EMG frequency spectrum for the BF during the mid-stance and pushing phases was related to the <6-month post-ACLR group, while the highest increase for the GC during the deceleration phase was related to the <12-month post-ACLR group.

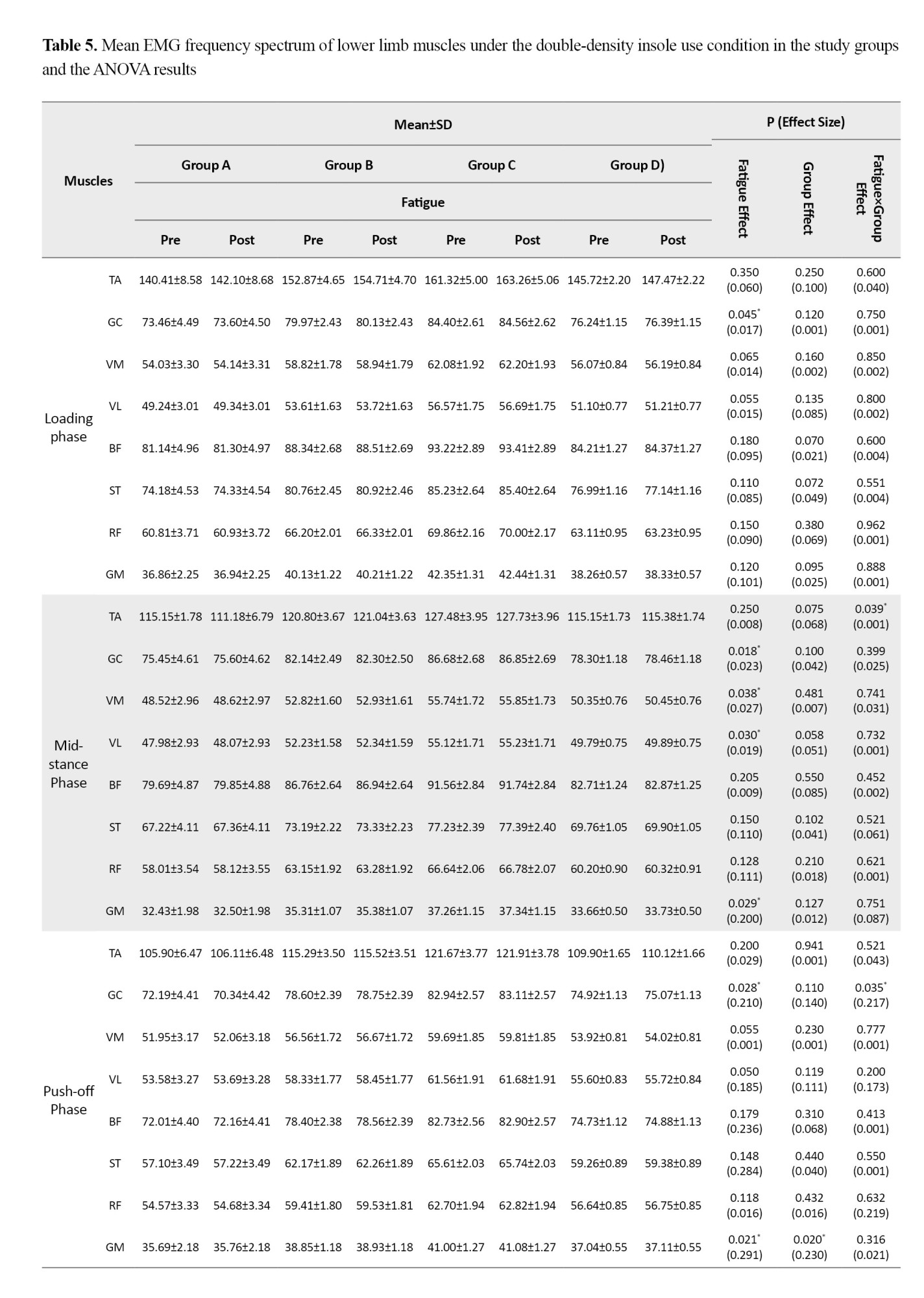

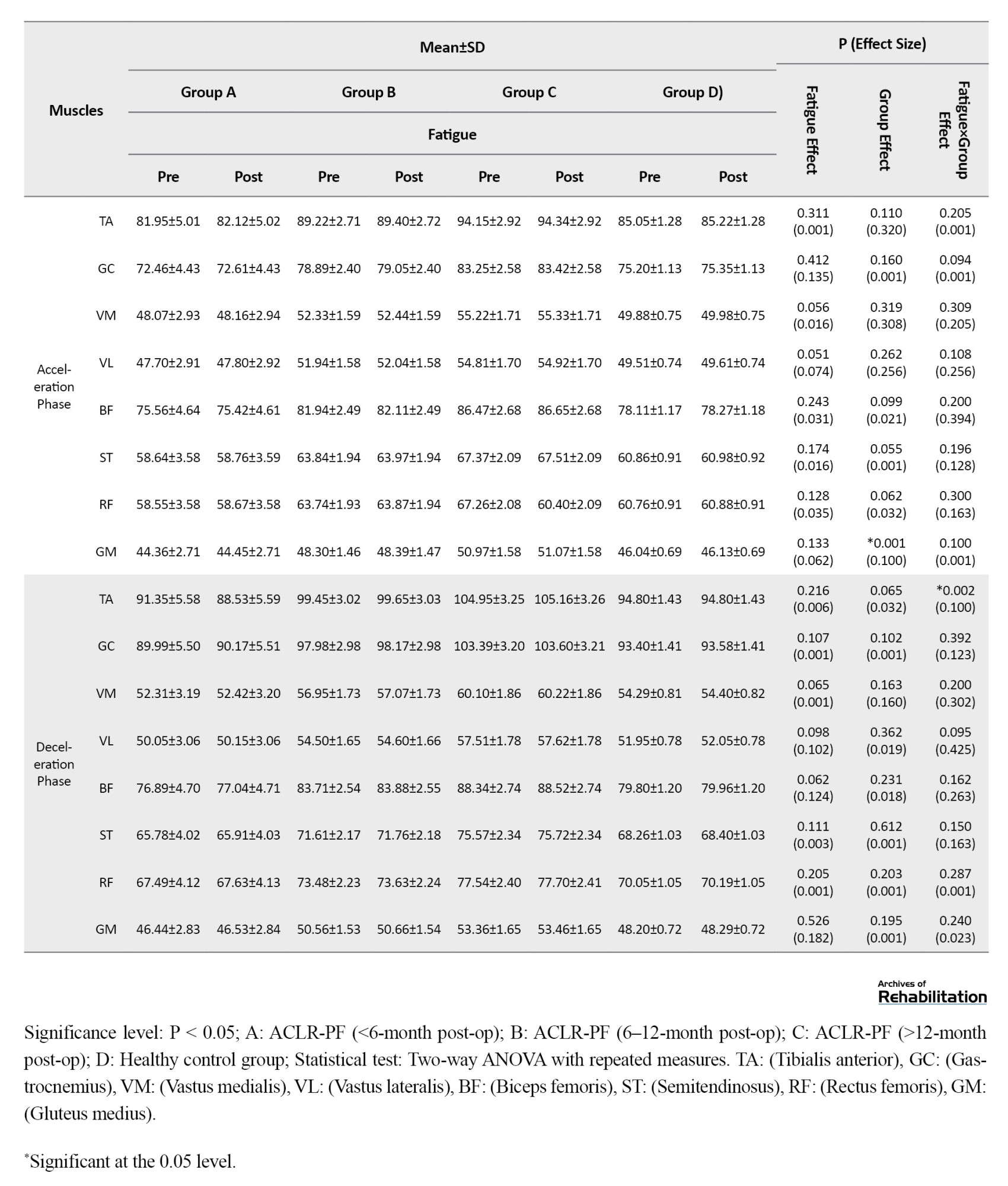

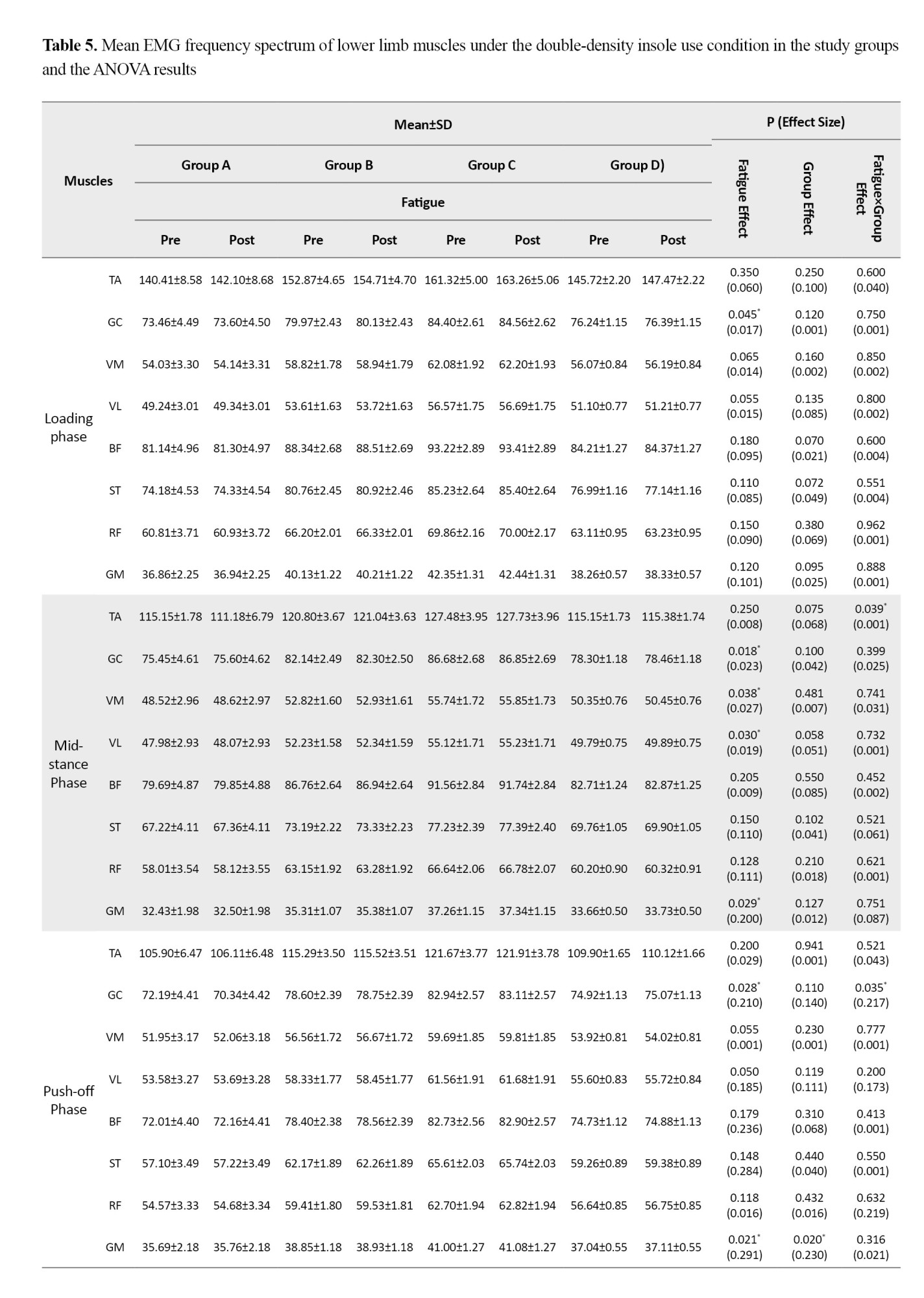

Based on the results in Table 5, when running with double-density insoles, the effect of the fatigue factor was statistically significant for the GC (d=0.017, P=0.045) during the loading phase.

During the mid-stance phase, significant fatigue effects were observed for the GC (d=0.023, P=0.018), VM (d=0.027, P=0.038), VL (d=0.019, P=0.030), and GM (d=0.200, P=0.029). Furthermore, during the push-off phase, significant effects of fatigue factor were found for the GC (d=0.210, P=0.028) and the GM (d=0.291, P=0.021). Additionally, the group factor effect was statistically significant for the GM during the push-off phase (d=0.230, P=0.020) and during the acceleration phase (d=0.100, P=0.001). The findings revealed a significant fatigue×group interaction effect, showing a statistically significant decrease for the TA during the mid-stance phase (d=0.001, P=0.039); for the GC during the push-off phase (d=0.217, P=0.035); and for the TA during the deceleration phase (d=0.100, P=0.002). Post-hoc test results indicated that the highest rate of decrease was related to the <6-month post-ACLR group compared to the other groups.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of different insole types and fatigue on the EMG frequency spectrum of lower limb muscles during running in men with ACLR-FP at 6, 12, and 18 months post-ACLR.

Under the control shoe use condition, the observed increase in the EMG frequency spectrum of the TA muscle in response to fatigue may indicate a neuromuscular compensatory strategy [36]. Typically, fatigue is expected to reduce the muscle electrical activity due to factors such as metabolic acidosis and reduced neural conduction velocity. However, the increase observed in this study can be attributed to the preferential recruitment of fast-twitch motor units. Under fatigue conditions, the efficiency of slow-twitch fibers declines, and the central nervous system is compelled to recruit larger, fast-twitch motor units with higher firing rates to maintain performance levels and joint stability. This manifests as an increase in higher-frequency spectral components of the muscle EMG signal [14, 15]. While this compensatory mechanism is essential in the short term to counter instability and absorb shock, in the long term, it can alter optimal movement patterns and predispose individuals to conditions such as anterior compartment syndrome or shin splints [37, 38]. Jafarnezhadgero et al. also reported that fatigue can alter the activity pattern of the hamstring muscles during dynamic activities [17]. Based on our findings, in the ACLR groups, the EMG frequency spectrum of the BF muscle showed a significant decrease during the deceleration phase of running when the control shoes were used. According to previous studies, this muscle is highly active during the swing phase to prevent excessive forward translation of the tibia relative to the femur, which can stretch the ACL [39]. Reduced activity or altered EMG frequency spectrum of this muscle following fatigue is highly concerning. This indicates that fatigue can weaken the protective mechanism of the hamstrings, particularly exposing ACLR patients in the early stages of recovery (<6 months post-surgery) to a higher risk of re-injury. In line with this, Fontenay et al. [40] stated that fatigue exacerbates asymmetry and specifically jeopardizes the knee’s protective mechanism in the early stages of recovery (<6 months).

Under the placebo insole use condition, the highest rate of increase in the EMG frequency spectrum was observed in the BF during the loading phase and the GM during the stance phase. This increase was significantly higher in the ACLR group with <6 months post-surgery than in the other groups. From a biomechanical perspective, the BF plays a pivotal role during the loading phase of running. Through eccentric contraction, it controls the anterior translation of the tibia and applies posteriorly-directed (restraint) forces on the knee joint [41]. Since the ACL is primarily responsible for restraining this displacement, the limb employs a compensatory mechanism after injury, such as increasing the activation of the BF, to substitute for the function of the damaged ligament and maintain dynamic knee stability. Concurrently, the increased GM activity during the stance phase indicates the neuromuscular system’s effort to maintain pelvic stability. This pattern of augmented activation in patients less than 6 months post-ACLR may reflect the central nervous system’s maximal effort to utilize compensatory mechanisms and re-learn optimal movement patterns during the early stages of returning to dynamic activities such as running. This phenomenon may indicate greater neuroplasticity and neuromuscular adaptation during this specific timeframe. Although these changes were statistically significant, the calculated effect size for these interactions was small in many cases. This suggests that while the pattern of changes is directional and interpretable, their magnitude is lower and may not have immediate, pronounced clinical significance. However, identifying these subtle changes in the early stages of recovery can be a sensitive indicator of the neuromuscular system’s compensatory strategies, which, if sustained, can influence running mechanics in the long term.

Under the arch support insole use condition, analysis indicated that the pattern of neuromuscular recovery follows distinct trajectories across different time points post-ACLR. In patients with less than 6 months post-surgery, the most pronounced improvement in muscle electrical activity was observed in the BF during the mid-stance and push-off phases. This pattern can be interpreted as an initial neuromuscular compensatory strategy, emphasizing dynamic knee joint stability through enhanced hamstring activation during the early stages of returning to activity [42]. This pattern evolves with increased time since surgery. In the group with 6-12 months post-ACLR, the greatest improvement in electrical activity was recorded for the GC muscle during the deceleration phase. This shift indicates a gradual transition in the motor control system’s focus from knee joint stability to improved control of center of mass oscillations and postural stability throughout the gait cycle [43].

The use of the arch-support insole led to a significant increase in the electrical activity of the GM muscle during the mid-stance phase. This muscle, which is considered the primary stabilizer of the pelvis in the frontal plane, with its weakness, causes increased femoral internal rotation and stress on the ACL. The arch-support insole, by providing structured support for the medial longitudinal arch, reduces the speed and magnitude of pronation during the mid-stance phase, thereby influencing the higher kinetic chain. These changes enable the neuromuscular system to optimize GM activation as the primary pelvic stabilizer [44]. Under the placebo insole use condition, the effect of fatigue on the electrical activity of the GC was clearly evident, whereas this effect was noticeably moderated when the arch support insoles used. It seems that these insoles facilitate neuromuscular coordination even under fatigue, not only by reducing direct mechanical load but also by providing enhanced proprioceptive inputs.

Regarding the double-density insoles, with their dual design, they not only support the arch but also provide stronger proprioceptive feedback and more active control over pronation. The significant effect of fatigue on the VM and VL muscles during the mid-stance phase indicates that, despite the support of the double-density insoles, the quadriceps muscles remain under considerable load. This may be because the insole, by improving lower limb alignment, allows the individual to run with greater efficiency and consequently utilize their quadriceps more, which ultimately leads to their fatigue. This finding likely indicates a normalization of running and muscle activation patterns [45]. Erkan et al. demonstrated that corrective insoles lead to a significant increase in the EMG activity of the VM and VL muscles during the stance phase, which aligns with the normalization of muscle patterns and increased workload on the quadriceps [46]. In the present study, the limitations included the non-inclusion of women and the lack of study on the long-term effects of therapeutic insoles. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies be conducted by addressing these limitations.

Conclusion

It seems that both fatigue and different types of therapeutic insoles can alter the neuromuscular activity pattern in men with ACLR-FP. Among the insoles examined, arch-support insoles and double-density insoles showed greater potential in mitigating the negative effects of fatigue and improving muscle electrical activity, particularly in patients in the early postoperative stages (less than 6 months post-ACLR).

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran (Code: IR.UMA.REC.1404.019) and was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20220129053865N2).

Funding

This article was extracted from the dissertation of Ebrahim Piri at the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this research.

The fatigue protocol was performed on an advanced treadmill (Horizon Fitness, Omega GT, USA) at zero incline. At the start of the protocol, participants began walking at 6 km/h, and the speed increased by 1 km/h every 2 minutes. Borg’s rate of perceived exertion (RPE) scale of 6–20 was used to determine the final level of fatigue for each participant [34]. Once participants reported a perceived exertion rating of 13 or higher, the treadmill speed was held constant to allow for steady-state running. During the steady-state phase, the perceived exertion score was assessed every 30 seconds. The fatigue protocol was terminated after two minutes of steady-state running when the RPE scale score was above 17, or upon reaching 80% of maximum heart rate [35].

Statistical analysis

Normality of the data distribution was confirmed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Homogeneity of variances was confirmed using Levene’s test (P>0.05). A repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed for data analysis. All analyses were performed in SPSS software, version 23, considering a significance level at P<0.05.

Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1.

The frequency spectrum of the EMG activity for the lower limb muscles across different running phases showed no significant differences between the study groups in the pre-test stage (P>0.05). According to the results in Table 2, under the control shoe use condition, the effect of the fatigue factor was statistically significant for the TA muscle during the loading response (Effect size (d)=0.215; P=0.024) and the push-off phase (d=0.200; P=0.003).

The effect of fatigue was also statistically significant for the GC (d=0.400; P=0.030) and BF (d=0.001; P=0.001) muscles during the deceleration phase. Furthermore, the group factor showed a significant effect on EMG frequency spectrum for the GC (d=0.200; P=0.015) and BF (d=0.001; P=0.003) muscles during the deceleration phase. The findings revealed no significant interaction effect of fatigue and group on the EMG activity of lower limb muscles across any running phases when control shoes were used.

Based on the results in Table 3, when running with placebo insoles, the effect of the fatigue factor was statistically significant for the TA (d=0.028, P=0.008) and BF (d=0.240, P=0.049) muscles during the loading phase.

Significant fatigue effects were also observed during the mid-stance phase for the TA (d=0.041, P=0.002), GC (d=0.222, P=0.015), VM (d=0.019, P=0.038), VL (d=0.019, P=0.036), and BF (d=0.029, P=0.006); during the deceleration phase for the VM (d=0.018, P=0.042), VL (d=0.009, P=0.039), and GM (d=0.009, P=0.035); and during the acceleration phase for the GM (d=0.019, P=0.035). Furthermore, the group factor effect was statistically significant for the TA (d=0.021, P=0.035) and GC (d=0.025, P=0.020) during the loading phase, and for the GM during the mid-stance phase (d=0.260, P=0.018). The findings revealed a significant fatigue×group interaction effect for the BF during the loading phase (d=0.200, P=0.038) and for the GM during the mid-stance phase (d=0.019, P=0.048). Post-hoc test results indicated that the highest rate of increase was observed in the <6-month post-ACLR group compared to the other groups.

Based on the results in Table 4, when running with arch support insoles, the effect of fatigue factor was statistically significant for the TA (d=0.018, P=0.040) and BF (d=0.020, P=0.030) muscles during the loading phase.

During the mid-stance phase, significant fatigue effects were observed for the TA (d=0.021, P=0.022), GC (d=0.025, P=0.010), BF (d=0.024, P=0.012), and ST (d=0.022, P=0.025). Furthermore, during the push-off phase, significant fatigue effects were found for the TA (d=0.019, P=0.035), GC (d=0.021, P=0.028), BF (d=0.022, P=0.025), and ST (d=0.020, P=0.032). Additionally, the group factor effect was statistically significant for the GC during the loading phase (d=0.230, P=0.025), and for the GM during both the mid-stance phase (d=0.022, P=0.028) and the deceleration phase (d=0.210, P=0.027). The findings revealed a significant fatigue×group interaction effect for the BF, which showed a significant increase during both mid-stance (d=0.019, P=0.045) and push-off (d=0.020, P=0.040) phases. A significant interaction effect was also observed for the GC during the deceleration phase (d=0.018, P=0.048). Post-hoc test results indicated that the highest rate of increase in EMG frequency spectrum for the BF during the mid-stance and pushing phases was related to the <6-month post-ACLR group, while the highest increase for the GC during the deceleration phase was related to the <12-month post-ACLR group.

Based on the results in Table 5, when running with double-density insoles, the effect of the fatigue factor was statistically significant for the GC (d=0.017, P=0.045) during the loading phase.

During the mid-stance phase, significant fatigue effects were observed for the GC (d=0.023, P=0.018), VM (d=0.027, P=0.038), VL (d=0.019, P=0.030), and GM (d=0.200, P=0.029). Furthermore, during the push-off phase, significant effects of fatigue factor were found for the GC (d=0.210, P=0.028) and the GM (d=0.291, P=0.021). Additionally, the group factor effect was statistically significant for the GM during the push-off phase (d=0.230, P=0.020) and during the acceleration phase (d=0.100, P=0.001). The findings revealed a significant fatigue×group interaction effect, showing a statistically significant decrease for the TA during the mid-stance phase (d=0.001, P=0.039); for the GC during the push-off phase (d=0.217, P=0.035); and for the TA during the deceleration phase (d=0.100, P=0.002). Post-hoc test results indicated that the highest rate of decrease was related to the <6-month post-ACLR group compared to the other groups.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of different insole types and fatigue on the EMG frequency spectrum of lower limb muscles during running in men with ACLR-FP at 6, 12, and 18 months post-ACLR.

Under the control shoe use condition, the observed increase in the EMG frequency spectrum of the TA muscle in response to fatigue may indicate a neuromuscular compensatory strategy [36]. Typically, fatigue is expected to reduce the muscle electrical activity due to factors such as metabolic acidosis and reduced neural conduction velocity. However, the increase observed in this study can be attributed to the preferential recruitment of fast-twitch motor units. Under fatigue conditions, the efficiency of slow-twitch fibers declines, and the central nervous system is compelled to recruit larger, fast-twitch motor units with higher firing rates to maintain performance levels and joint stability. This manifests as an increase in higher-frequency spectral components of the muscle EMG signal [14, 15]. While this compensatory mechanism is essential in the short term to counter instability and absorb shock, in the long term, it can alter optimal movement patterns and predispose individuals to conditions such as anterior compartment syndrome or shin splints [37, 38]. Jafarnezhadgero et al. also reported that fatigue can alter the activity pattern of the hamstring muscles during dynamic activities [17]. Based on our findings, in the ACLR groups, the EMG frequency spectrum of the BF muscle showed a significant decrease during the deceleration phase of running when the control shoes were used. According to previous studies, this muscle is highly active during the swing phase to prevent excessive forward translation of the tibia relative to the femur, which can stretch the ACL [39]. Reduced activity or altered EMG frequency spectrum of this muscle following fatigue is highly concerning. This indicates that fatigue can weaken the protective mechanism of the hamstrings, particularly exposing ACLR patients in the early stages of recovery (<6 months post-surgery) to a higher risk of re-injury. In line with this, Fontenay et al. [40] stated that fatigue exacerbates asymmetry and specifically jeopardizes the knee’s protective mechanism in the early stages of recovery (<6 months).

Under the placebo insole use condition, the highest rate of increase in the EMG frequency spectrum was observed in the BF during the loading phase and the GM during the stance phase. This increase was significantly higher in the ACLR group with <6 months post-surgery than in the other groups. From a biomechanical perspective, the BF plays a pivotal role during the loading phase of running. Through eccentric contraction, it controls the anterior translation of the tibia and applies posteriorly-directed (restraint) forces on the knee joint [41]. Since the ACL is primarily responsible for restraining this displacement, the limb employs a compensatory mechanism after injury, such as increasing the activation of the BF, to substitute for the function of the damaged ligament and maintain dynamic knee stability. Concurrently, the increased GM activity during the stance phase indicates the neuromuscular system’s effort to maintain pelvic stability. This pattern of augmented activation in patients less than 6 months post-ACLR may reflect the central nervous system’s maximal effort to utilize compensatory mechanisms and re-learn optimal movement patterns during the early stages of returning to dynamic activities such as running. This phenomenon may indicate greater neuroplasticity and neuromuscular adaptation during this specific timeframe. Although these changes were statistically significant, the calculated effect size for these interactions was small in many cases. This suggests that while the pattern of changes is directional and interpretable, their magnitude is lower and may not have immediate, pronounced clinical significance. However, identifying these subtle changes in the early stages of recovery can be a sensitive indicator of the neuromuscular system’s compensatory strategies, which, if sustained, can influence running mechanics in the long term.

Under the arch support insole use condition, analysis indicated that the pattern of neuromuscular recovery follows distinct trajectories across different time points post-ACLR. In patients with less than 6 months post-surgery, the most pronounced improvement in muscle electrical activity was observed in the BF during the mid-stance and push-off phases. This pattern can be interpreted as an initial neuromuscular compensatory strategy, emphasizing dynamic knee joint stability through enhanced hamstring activation during the early stages of returning to activity [42]. This pattern evolves with increased time since surgery. In the group with 6-12 months post-ACLR, the greatest improvement in electrical activity was recorded for the GC muscle during the deceleration phase. This shift indicates a gradual transition in the motor control system’s focus from knee joint stability to improved control of center of mass oscillations and postural stability throughout the gait cycle [43].

The use of the arch-support insole led to a significant increase in the electrical activity of the GM muscle during the mid-stance phase. This muscle, which is considered the primary stabilizer of the pelvis in the frontal plane, with its weakness, causes increased femoral internal rotation and stress on the ACL. The arch-support insole, by providing structured support for the medial longitudinal arch, reduces the speed and magnitude of pronation during the mid-stance phase, thereby influencing the higher kinetic chain. These changes enable the neuromuscular system to optimize GM activation as the primary pelvic stabilizer [44]. Under the placebo insole use condition, the effect of fatigue on the electrical activity of the GC was clearly evident, whereas this effect was noticeably moderated when the arch support insoles used. It seems that these insoles facilitate neuromuscular coordination even under fatigue, not only by reducing direct mechanical load but also by providing enhanced proprioceptive inputs.

Regarding the double-density insoles, with their dual design, they not only support the arch but also provide stronger proprioceptive feedback and more active control over pronation. The significant effect of fatigue on the VM and VL muscles during the mid-stance phase indicates that, despite the support of the double-density insoles, the quadriceps muscles remain under considerable load. This may be because the insole, by improving lower limb alignment, allows the individual to run with greater efficiency and consequently utilize their quadriceps more, which ultimately leads to their fatigue. This finding likely indicates a normalization of running and muscle activation patterns [45]. Erkan et al. demonstrated that corrective insoles lead to a significant increase in the EMG activity of the VM and VL muscles during the stance phase, which aligns with the normalization of muscle patterns and increased workload on the quadriceps [46]. In the present study, the limitations included the non-inclusion of women and the lack of study on the long-term effects of therapeutic insoles. Therefore, it is recommended that future studies be conducted by addressing these limitations.

Conclusion

It seems that both fatigue and different types of therapeutic insoles can alter the neuromuscular activity pattern in men with ACLR-FP. Among the insoles examined, arch-support insoles and double-density insoles showed greater potential in mitigating the negative effects of fatigue and improving muscle electrical activity, particularly in patients in the early postoperative stages (less than 6 months post-ACLR).

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran (Code: IR.UMA.REC.1404.019) and was registered by the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (ID: IRCT20220129053865N2).

Funding

This article was extracted from the dissertation of Ebrahim Piri at the University of Mohaghegh Ardabili, Ardabil, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally to the conception and design of the study, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the results, and drafting of the manuscript. Each author approved the final version of the manuscript for submission.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this research.

References

- Piri E, Sobhani V, Jafarnezhadgero A, Arabzadeh E, Shamsoddini A, Zago M, et al. Effect of double-density foot orthoses on ground reaction forces and lower limb muscle activities during running in adults with and without pronated feet. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2025; 17(1):54. [DOI:10.1186/s13102-025-01095-5] [PMID]

- Piri E, Jafarnezhadgero A, Dehghani M, Rezazadeh F, Enteshari-Moghaddam A. [Running mechanics in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction 6–12 months after surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (Persian)]. Journal of Sport Biomechanics.. 2026; 12(1):52-69. [DOI:10.61882/JSportBiomech.12.1.52]

- Jafarnezhadgero AA, Alizadeh R, Mirzanag EF, Dionisio VC. Could the anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and pronated feet affect the plantar pressure variables and muscular activity during running? A comparative study. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 2024; 40:986-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbmt.2024.07.020] [PMID]

- Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: The delaware-oslo ACL cohort study. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2016; 50(13):804-8. [DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096031] [PMID]

- Dunn J, Link C, Felson D, Crincoli M, Keysor J, McKinlay J. Prevalence of foot and ankle conditions in a multiethnic community sample of older adults. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004; 159(5):491-8. [DOI:10.1093/aje/kwh071] [PMID]

- Chen KC, Tung LC, Tung CH, Yeh CJ, Yang JF, Wang CH. An investigation of the factors affecting flatfoot in children with delayed motor development. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2014; 35(3):639-45. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2013.12.012] [PMID]

- Dolk DC, Hedevik H, Stigson H, Wretenberg P, Kvist J, Stålman A. Nationwide incidence of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in higher-level athletes in Sweden: A cohort study from the swedish national knee ligament registry linked to six sports organisations. British Journal of Sports Medicine. 2025; 59(7):470-9. [DOI:10.1136/bjsports-2024-108343] [PMID]

- Koreili Z, Fatahi A, Azarbayjani MA, Sharifnezhad A. [Comparison of static balance performance and plantar selected parameters in dominant and non-dominant leg active female adolescents with ankle pronation (Persian)]. The Scientific Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2023; 12(2):306-19. [Link]

- Piri E, Jafarnezhadgero A, Stålman A. Advantages and disadvantages of different surgical grafts in anterior cruciate ligament injuries: A letter to the editor. Journal of Sport Biomechanics. 2024; 10(3):254-60. [DOI:10.61186/JSportBiomech.10.3.254]

- Cristiani R, Forssblad M, Edman G, Eriksson K, Stålman A. Age, time from injury to surgery and hop performance after primary ACLR affect the risk of contralateral ACLR. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 2022; 30(5):1828-35. [DOI:10.1007/s00167-021-06759-6] [PMID]

- Pfeiffer TR, Burnham JM, Hughes JD, Kanakamedala AC, Herbst E, Popchak A, et al. An increased lateral femoral condyle ratio is a risk factor for anterior cruciate ligament injury. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American volume. 2018; 100(10):857-64. [DOI:10.2106/JBJS.17.01011] [PMID]

- Ghorbanlou F, Jaafarnejad A, Fatollahi A. Effects of corrective exercise protocol utilizing a theraband on muscle activity during running in individuals with genu valgum. The Scientific Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2021; 10(5):1052-65. [DOI:10.32598/SJRM.10.5.2]

- Hewett TE, Myer GD, Ford KR, Heidt Jr RS, Colosimo AJ, McLean SG, et al. Biomechanical measures of neuromuscular control and valgus loading of the knee predict anterior cruciate ligament injury risk in female athletes: A prospective study. The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 2005; 33(4):492-501. [DOI:10.1177/0363546504269591] [PMID]

- Gray EG, Basmajian JV. Electromyography and cinematography of leg and foot (“normal” and flat) during walking. The Anatomical Record. 1968; 161(1):1-15. [DOI:10.1002/ar.1091610101] [PMID]

- Lim BW, Hinman RS, Wrigley TV, Sharma L, Bennell KL. Does knee malalignment mediate the effects of quadriceps strengthening on knee adduction moment, pain, and function in medial knee osteoarthritis? A randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Care & Research: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology. 2008; 59(7):943-51. [DOI:10.1002/art.23823] [PMID]

- Naderi A, Baloochi R, Rostami KD, Fourchet F, Degens H. Obesity and foot muscle strength are associated with high dynamic plantar pressure during running. The Foot. 2020; 44:101683. [DOI:10.1016/j.foot.2020.101683] [PMID]

- Jaafarnejad A, Valizade-Orang A, Ghaderi K. [Comparison of muscular activities in patients with covid19 and healthy control individuals during gait (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2021; 10(1):168-74. [DOI:10.22037/jrm.2021.114587.2563]

- Gerlach KE, White SC, Burton HW, Dorn JM, Leddy JJ, Horvath PJ. Kinetic changes with fatigue and relationship to injury in female runners. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2005; 37(4):657-63. [DOI:10.1249/01.MSS.0000158994.29358.71] [PMID]

- McPoil TG, Cornwall MW. The effect of foot orthoses on transverse tibial rotation during walking. Journal of the American Podiatric Medical Association. 2000; 90(1):2-11. [DOI:10.7547/87507315-90-1-2] [PMID]

- Klingman RE, Liaos SM, Hardin KM. The effect of subtalar joint posting on patellar glide position in subjects with excessive rearfoot pronation. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 1997; 25(3):185-91. [DOI:10.2519/jospt.1997.25.3.185] [PMID]

- Nawoczenski DA, Ludewig PM. Electromyographic effects of foot orthotics on selected lower extremity muscles during running. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 1999; 80(5):540-4. [DOI:10.1016/S0003-9993(99)90196-X] [PMID]

- Hsieh RL, Peng HL, Lee WC. Short-term effects of customized arch support insoles on symptomatic flexible flatfoot in children: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine. 2018; 97(20). [DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000010655] [PMID]

- Yip CH, Chiu TT, Poon AT. The relationship between head posture and severity and disability of patients with neck pain. Manual Therapy. 2008; 13(2):148-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.math.2006.11.002] [PMID]

- Jafarnezhadgero AA, Majlesi M, Azadian E. Gait ground reaction force characteristics in deaf and hearing children. Gait & Posture. 2017; 53:236-40. [DOI:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2017.02.006] [PMID]

- Picciano AM, Rowlands MS, Worrell T. Reliability of open and closed kinetic chain subtalar joint neutral positions and navicular drop test. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 1993; 18(4):553-8. [DOI:10.2519/jospt.1993.18.4.553] [PMID]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2001;79(4):373-4. [PMID]

- McWalter EJ, Cibere J, MacIntyre NJ, Nicolaou S, Schulzer M, Wilson DR. Relationship between varus-valgus alignment and patellar kinematics in individuals with knee osteoarthritis. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American volume. 2007; 89(12):2723-31. [DOI:10.2106/JBJS.F.01016] [PMID]

- Williams DS, McClay IS. Measurements used to characterize the foot and the medial longitudinal arch: reliability and validity. Physical Therapy. 2000; 80(9):864-71. [DOI:10.1093/ptj/80.9.864]

- Valizadeorang A, Ghorbanlou F, Jafarnezhadgero A, Alipoor Sarinasilou M. [Effect of knee brace on frequency spectrum of ground reaction forces during landing from two heights of 30 and 50 cm in athletes with anterior cruciate ligament injury (Persian)]. The Scientific Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2019; 8(2):159-68. [DOI:10.22037/jrm.2018.111377.1950]

- Kamonseki DH, Gonçalves GA, Yi LC, Júnior IL. Effect of stretching with and without muscle strengthening exercises for the foot and hip in patients with plantar fasciitis: A randomized controlled single-blind clinical trial. Manual Therapy. 2016; 23:76-82. [DOI:10.1016/j.math.2015.10.006] [PMID]

- Farahpour N, Jafarnezhadgero A, Allard P, Majlesi M. Muscle activity and kinetics of lower limbs during walking in pronated feet individuals with and without low back pain. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2018; 39:35-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.jelekin.2018.01.006] [PMID]

- Cohen J. Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin. 112:1155-9. [Link]

- Alizadeh R, Jafarnezhadgero AA, Khezri D, Sajedi H, Fakhri Mirzanag E. [Effect of short-term use of anti-pronation insoles on plantar pressure variables following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with a pronated foot during gait (Persian)]. Journal of Gorgan University of Medical Sciences. 2024; 26(3):36-44. [DOI:10.61186/goums.26.3.36]

- Jafarnezhadgero AA, Noroozi Z, Piri E. [Evaluating the frequency of the electrical activity of lower limb muscles before and after fatigue during running in individuals with a history of coronavirus disease 2019 compared to healthy individuals (Persian)]. Journal of Gorgan University of Medical Sciences. 2024; 26(1):56-65. [DOI:10.61882/goums.26.1.56]

- Koblbauer IF, van Schooten KS, Verhagen EA, van Dieën JH. Kinematic changes during running-induced fatigue and relations with core endurance in novice runners. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 2014; 17(4):419-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.jsams.2013.05.013] [PMID]

- Ushiyama J, Katsu M, Masakado Y, Kimura A, Liu M, Ushiba J. Muscle fatigue-induced enhancement of corticomuscular coherence following sustained submaximal isometric contraction of the tibialis anterior muscle.Journal of Applied Physiology. 2011; 110(5):1233-40. [DOI:10.1152/japplphysiol.01194.2010] [PMID]

- Kaya Keles CS, Hiller J, Zimmer M, Ates F. In vivo tibialis anterior muscle mechanics through force estimation using ankle joint moment and shear wave elastography. Scientific Reports. 2025; 15(1):32461. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-025-18292-4] [PMID]

- Shan W, Zheng T, Zhang J, Pang R. Effect of electrical stimulation on functional recovery of lower limbs in patients after anterior cruciate ligament surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2025; 15(7):e089702. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2024-089702] [PMID]

- Kakehata G, Goto Y, Iso S, Kanosue K. The timing of thigh muscle activity is a factor limiting performance in the deceleration phase of the 100-m dash. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2022; 54(6):1002-12. [DOI:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002876] [PMID]

- Pairot-de-Fontenay B, Willy RW, Elias ARC, Mizner RL, Dubé MO, Roy JS. Running biomechanics in individuals with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review. Sports Medicine. 2019; 49(9):1411-24. [DOI:10.1007/s40279-019-01120-x] [PMID]

- Sahinis C, Amiridis IG, Enoka RM, Kellis E. Differences in activation amplitude between semitendinosus and biceps femoris during hamstring exercises: A systematic and critical review with meta-analysis. Journal of Sports Sciences. 2025; 43(11):1054-69. [DOI:10.1080/02640414.2025.2486879] [PMID]

- Chen B, Wu J, Jiang J, Wang G. Neuromuscular and biomechanical adaptations of the lower limbs during the pre-landing and landing phase of running under fatigue conditions. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(5):2449. [DOI:10.3390/app15052449]

- Thorp JE, Adamczyk PG. Mechanisms of gait phase entrainment in healthy subjects during rhythmic electrical stimulation of the medial gastrocnemius. Plos One. 2020; 15(10):e0241339. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0241339] [PMID]

- Meekins MM, Zucker-Levin A, Harris-Hayes M, Singhal K, Huffman K, Kasser R. The effect of chronic low back pain and lumbopelvic stabilization instructions on gluteus medius activation during sidelying hip movements. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2025; 41(3):563-70. [DOI:10.1080/09593985.2024.2357130] [PMID]

- Zhang X, Ren W, Wang X, Yao J, Pu F. Quantitative analysis of quadriceps forces in adolescent females during running with infrapatellar straps. Journal of Sports Science & Medicine. 2024; 23(4):787-98. [DOI:10.52082/jssm.2024.787] [PMID]

- Erkan E, Çankaya T. Investigation of the effect of different types of insoles on electromyographic muscle activation in individuals with pes planus. Karya Journal of Health Science. 2025; 6(1):38-43. [DOI:10.52831/kjhs.1537793]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Orthotics & Prosthetics

Received: 20/10/2025 | Accepted: 12/12/2025 | Published: 1/01/2026

Received: 20/10/2025 | Accepted: 12/12/2025 | Published: 1/01/2026

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |