Volume 26, Issue 4 (Winter 2026)

jrehab 2026, 26(4): 552-571 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.USWR.REC.1403.130

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Faghihi T, Sadeghi Z, Ghoreishi Z S, Mokhlessin M, Vahedi M, Bagherpour P. Translation, Cross-Cultural Adaptation, and Psychometric Evaluation of Features of the Infant and Child Feeding Questionnaire (ICFQ). jrehab 2026; 26 (4) :552-571

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3662-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3662-en.html

Tayebeh Faghihi1

, Zahra Sadeghi *2

, Zahra Sadeghi *2

, Zahra Sadat Ghoreishi3

, Zahra Sadat Ghoreishi3

, Maryam Mokhlessin4

, Maryam Mokhlessin4

, Mohsen Vahedi5

, Mohsen Vahedi5

, Pouran Bagherpour6

, Pouran Bagherpour6

, Zahra Sadeghi *2

, Zahra Sadeghi *2

, Zahra Sadat Ghoreishi3

, Zahra Sadat Ghoreishi3

, Maryam Mokhlessin4

, Maryam Mokhlessin4

, Mohsen Vahedi5

, Mohsen Vahedi5

, Pouran Bagherpour6

, Pouran Bagherpour6

1- Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Student Research Committee, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,z.sadeghi.st@gmail.com

3- Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Neuromuscular Rehabilitation Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

5- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

6- PhD Candidate in Rehabilitation Sciences, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

2- Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Speech and Language Pathology, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Neuromuscular Rehabilitation Research Center, Semnan University of Medical Sciences, Semnan, Iran.

5- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

6- PhD Candidate in Rehabilitation Sciences, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada.

Full-Text [PDF 2171 kb]

(75 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (1120 Views)

Full-Text: (39 Views)

Introduction

Adequate nutrition during infancy and early childhood is a fundamental component of growth and overall health. Evidence indicates that optimal feeding not only influences physical growth but also plays a crucial role in cognitive, emotional, and social development [1]. Nevertheless, pediatric feeding disorders are recognized as a significant global health challenge, with reported prevalence rates of 25–45% in typically developing children and up to 80% in children with special needs [2, 3]. The consequences of these disorders can manifest in both short- and long-term outcomes. In the short term, issues such as growth delays and increased susceptibility to infections are observed, whereas long-term consequences may include cognitive impairments and chronic medical conditions [4, 5]. Pediatric feeding disorders may result in serious nutritional, developmental, and psychological complications, and if not diagnosed and managed promptly, these problems can progressively worsen and may even lead to mortality [2, 6]. A particularly concerning issue is that the diagnosis of these disorders is often delayed until 2–4 years of age [7], which can have irreversible effects on the child’s growth and the family’s quality of life [8–10]. The key strategy to prevent these outcomes lies in early identification and timely intervention for feeding disorders (from birth and within the first two years of life) [11, 12]. Implementing any timely intervention requires the availability of appropriate assessment tools.

Currently, several instruments are available for assessing children’s feeding behaviors. The child eating behavior questionnaire (CEBQ), whose Persian version has been evaluated in Iran for children aged 1–5 years, demonstrates acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.71 to 0.83) and adequate construct validity (explaining over 50% of the variance across multiple factors). However, due to the large number of items, its administration is relatively time-consuming, and it is not applicable for children under one year of age [13]. The screening tool for eating problems (STEP) consists of 23 items and is completed by psychologists or therapists who have worked with the patient for at least six months. This instrument was designed for the rapid identification of feeding problems in individuals with intellectual disabilities and has demonstrated acceptable inter-rater reliability and construct validity in previous evaluations [14].

Additionally, the pediatric eating assessment tool (Pedi-EAT) is available, with its Persian version used to assess feeding behaviors in children up to seven years of age. This tool comprises four subscales, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.83 to 0.92 and strong test-retest reliability (r=0.95), although its completion is also time-consuming [15]. Another instrument with a Persian version is the anderson dysphagia inventory (MDADI), designed to evaluate the quality of life in patients with dysphagia. Nevertheless, many of the existing instruments are not suitable for children under six months of age and are relatively time-consuming and complex to administer. Therefore, there is a need to develop a brief, valid, and practical questionnaire for initial screening in this population [16]. Notably, none of these tools cover children under six months, highlighting the necessity for a short, valid, and appropriate instrument for early screening in Persian-speaking infants under six months of age.

The infant and child feeding questionnaire (ICFQ) is a parent-report screening tool developed by Silverman and colleagues for children aged 0–4 years, aimed at the early identification of warning signs related to feeding. The questionnaire consists of 12 items completed by parents, which, through the evaluation of behavioral patterns and feeding-related indicators, enables the preliminary detection of feeding disorders. With its simple and easily comprehensible design, the ICFQ can be administered in both clinical and care settings by parents and professionals. The original version of this tool demonstrated favorable psychometric properties. Silverman confirmed its construct validity through comparisons between two known groups (children with feeding disorders and children without disorders). Additionally, criterion validity was supported by significant correlations with expert evaluations. receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis indicated that the questionnaire exhibits notable diagnostic accuracy in identifying cases requiring referral, with high sensitivity and specificity [17]. Key advantages of the ICFQ include: Samall number of items, reliance on parent-report, and coverage of infants under six months, making it suitable for cultural adaptation in the Iranian population and highly practical for early screening of feeding disorders in clinical and research settings. Therefore, the present study was conducted to translate and adapt the ICFQ into Persian and evaluate its psychometric properties.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This methodological study was conducted to translate and validate a screening tool for feeding disorders in Persian-speaking children. The study employed a cross-sectional design with two distinct groups of participants, including children with feeding disorders and typically developing children, along with their parents. The sample size was determined based on the sensitivity and specificity of the original version, comprising 220 children (100 children with feeding disorders and 120 typically developing children). Participants were recruited through convenience sampling from children aged 0–4 years whose at least one parent was fluent in Persian. Inclusion criteria for the feeding disorder group were a diagnosis of feeding disorder by a pediatrician, whereas for the typically developing group, children were included if they demonstrated normal development according to the ages and stages questionnaire (ASQ) and pediatrician evaluation, with no medical conditions predisposing them to feeding problems (e.g. surgical or traumatic injury, pneumonia, chronic dehydration, malnutrition, seizures, etc.). Exclusion criteria for both groups included incomplete questionnaire responses, parents withdrawal from participation, or loss of eligibility criteria for either the parent or the child. Prior to administration of the questionnaire to parents, the face and content validity of the instrument were assessed by 10 experienced speech-language pathologists.

Research instrument

The ICFQ, consisting of 12 items, was the primary instrument for this study [17]. This questionnaire completed by parents using yes/no responses, except for item 5, which includes two options “less than 5 minutes” and “more than 30 minutes” to assess feeding duration, and item 11, which is multiple-choice and allows parents to mark more than one behavior. All other items are scored dichotomously (yes/no). Scoring, except for item 11, is based on the presence or absence of warning behaviors: a score of 1 is assigned if the behavior is observed, and 0 if not. Item 11 is not included in the total score and is used solely for clinical referral purposes. Parents read the items and complete the questionnaire, and may ask the interviewer any questions if needed. The total score of the instrument is calculated by summing responses, excluding item 11. This scoring structure allows determination of a cut-off point for identifying children at risk of feeding disorders and provides clarity regarding the total score calculation and its relation to parental responses. Silverman’s study demonstrated that the questionnaire possesses favorable psychometric properties, with indicators such as area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity (73%), and specificity (93%) [17]. When two or more items are endorsed, sensitivity decreases while specificity increases. Furthermore, the behaviors included in the questionnaire can assist in identifying children requiring prompt referral to specialists.

Procedure

This study was conducted from December 2024 to June 2025. The methods employed included translation, cognitive interviews, evaluation of face and content validity, construct and criterion validity, descriptive analyses, and diagnostic accuracy assessment, following procedures similar to those used in previous studies [18, 19]. After obtaining permission for translation from the original questionnaire developer, the process of translating and culturally adapting the ICFQ was conducted in accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for the cultural adaptation of assessment instruments [20]. This protocol includes four main steps: forward translation, assessment of face and content validity, backward translation, and face validity assessment (cognitive interviews). In the forward translation phase, the questionnaire was independently translated by two speech-language pathologists whose native language was Persian and who were proficient in English. Subsequently, a third speech-language pathologist who was also proficient in English compared the two translations, analyzed discrepancies, and prepared the initial merged version. In the next step, two separate expert panels were established to assess face and content validity: the first panel included three specialists (the two original SLP translators and a nutritionist) who supervised the accurate transfer of concepts, precision of technical terminology, and clarity of language. After initial approval, the translated version was presented to a second panel consisting of 10 speech-language pathologists with varying educational backgrounds. This group carefully reviewed the items in terms of comprehensibility, simplicity, and cultural appropriateness. Then, they provided suggestions to improve the structure and content of the questionnaire.

To assess content validity, a quantitative approach based on the framework proposed by Waltz and Basel was employed, concurrently with the evaluation of face validity, similar to previous studies [21, 22]. In this phase, the questionnaire was independently reviewed by 10 experienced speech-language pathologists specialized in pediatric feeding disorders. Then, they rated the adequacy of each item based on three indices: clarity, relevance, and simplicity, using a four-point Likert scale (1=not suitable to 4=highly suitable). The use of a four-point scale in this step follows common procedures in content validity assessment, aiming to reduce midpoint responses and facilitate expert judgment. The item-level content validity index (I-CVI) was calculated with the ratio of the number of experts who gave a score of 3 or 4 to that item to the total number of raters. Values above 0.79 were considered acceptable. Additionally, the scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) was calculated using the average of I-CVIs across all items (S-CVI/Ave).

For backward translation, the Persian version of the questionnaire was translated back into English by a fourth translator who was proficient in English and blinded to the original version. The translated version was then compared with the original questionnaire to ensure conceptual equivalence and cultural adaptation. This step ensures that the core concepts of the questionnaire are preserved in the Persian version and are consistent with the original version.

To assess face validity and ensure clarity and comprehensibility of the translated version in the target population, cognitive interviews were conducted with 10 Persian-speaking parents of children aged 0–4 years (3 parents of children with feeding disorders and 7 parents of typically developing children). Parents read the questionnaire aloud and shared their interpretations, ambiguities, and suggestions. This process led to revisions of certain expressions, simplification of language, and improvement of the cultural appropriateness of the instrument, confirming that the Persian version was conceptually and linguistically understandable for respondents.

After preparing the Persian version of the questionnaire, data were collected from health centers, developmental clinics, and kindergartens in Qom. Parents completed the consent form and a demographic information questionnaire. For children with feeding disorders, participants were recruited through referrals by pediatricians based at comprehensive developmental centers, and feeding problems were confirmed by pediatric evaluation prior to questionnaire administration. For the typically developing group, some participants were directly selected from staff kindergartens affiliated with the comprehensive developmental centers, where pediatricians confirmed their health and nutritional status. Other typically developing children from different kindergartens were referred to pediatricians at the comprehensive developmental centers for health and nutritional assessment before entering the study. Subsequently, all children in the typically developing group completed the ASQ form to ensure developmental and nutritional health. Additionally, pediatrician evaluations in both groups were considered to confirm health status and diagnosis of feeding disorders. The Persian version of the ICFQ was completed by parents in both groups, while the Pedi-EAT questionnaire was administered only to children with feeding disorders to assess the construct validity of the Persian ICFQ. Questionnaires were completed in a quiet, undisturbed environment at the comprehensive developmental center or in the kindergartens. Parents personally filled out the questionnaires after receiving the necessary explanations, with the researcher present if clarification was needed. Completing each questionnaire took an average of 5 to 7 minutes.

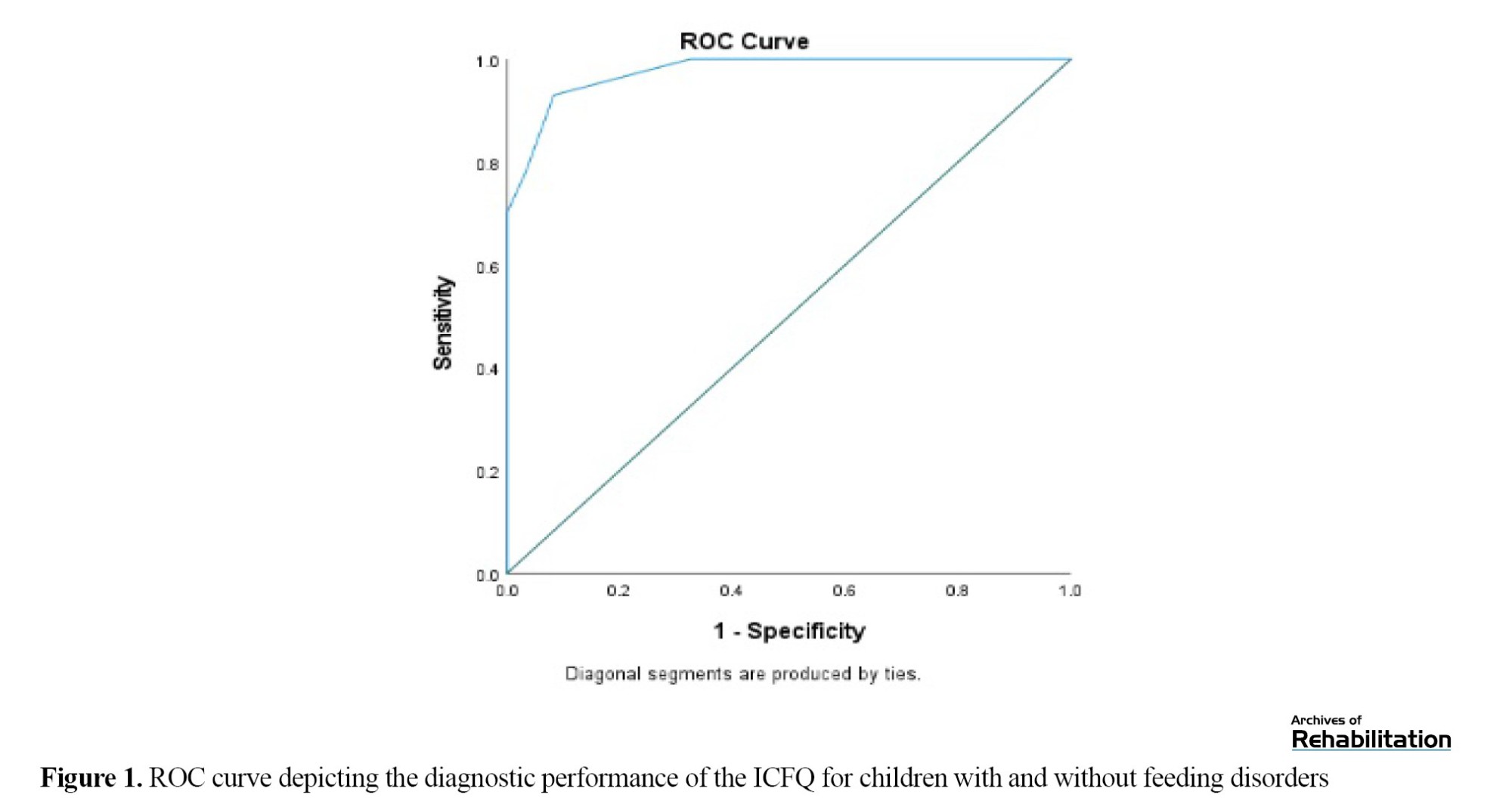

Construct validity was assessed using two approaches. First, known-groups validity was evaluated by comparing the mean ICFQ scores between children with feeding disorders and typically developing children. Next, convergent validity was examined by calculating the correlation between ICFQ scores and the Persian version of the validated Pedi-EAT questionnaire, which assesses feeding status in children. Criterion validity was also evaluated by comparing questionnaire results with pediatrician diagnoses. Finally, to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the instrument, ROC curve analysis was conducted to assess the questionnaire’s ability to discriminate between children with feeding disorders and typically developing children. Based on the ROC curve, the optimal cut-off point was identified, and the sensitivity and specificity of the tool at this threshold were calculated. In this analysis, pediatrician diagnosis was considered the gold standard for determining the presence or absence of feeding disorders in children.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis in this study was conducted at both descriptive and inferential levels. Initially, descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage, were used to summarize participants’ demographic characteristics and questionnaire scores.

At the inferential level, construct validity was assessed using known-groups validity and convergent validity. For known-groups validity, an independent t-test was used to compare mean ICFQ scores between children with feeding disorders and typically developing children. For convergent validity, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated between ICFQ scores and the Pedi-EAT questionnaire and its subscales. Criterion validity was evaluated using the Chi-square test to compare questionnaire results with pediatrician diagnoses. To determine the diagnostic accuracy of the instrument, ROC curve analysis was performed, and sensitivity, specificity, and the optimal cut-off point were reported. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25, with a significance level set at P<0.05 for all tests.

Results

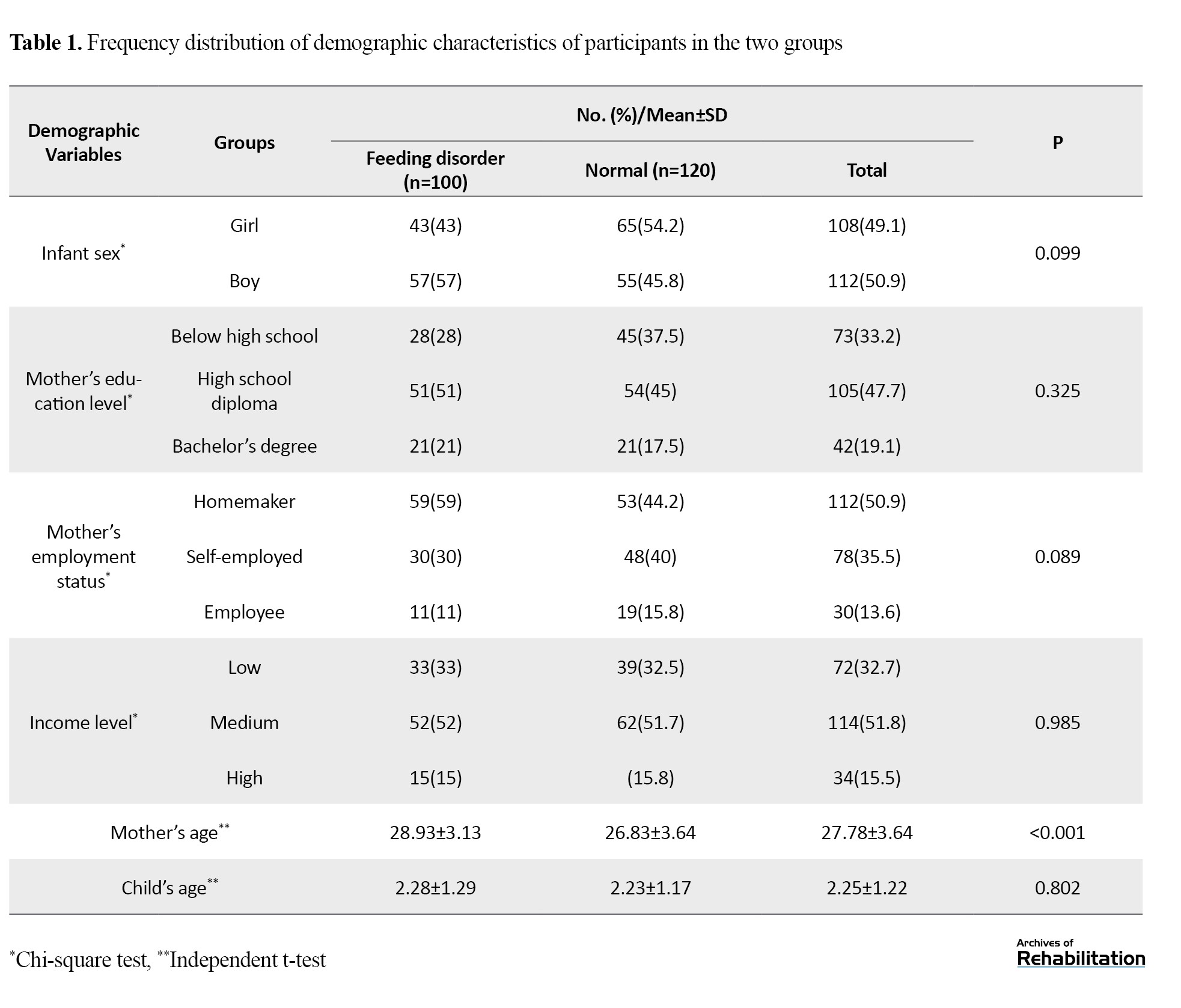

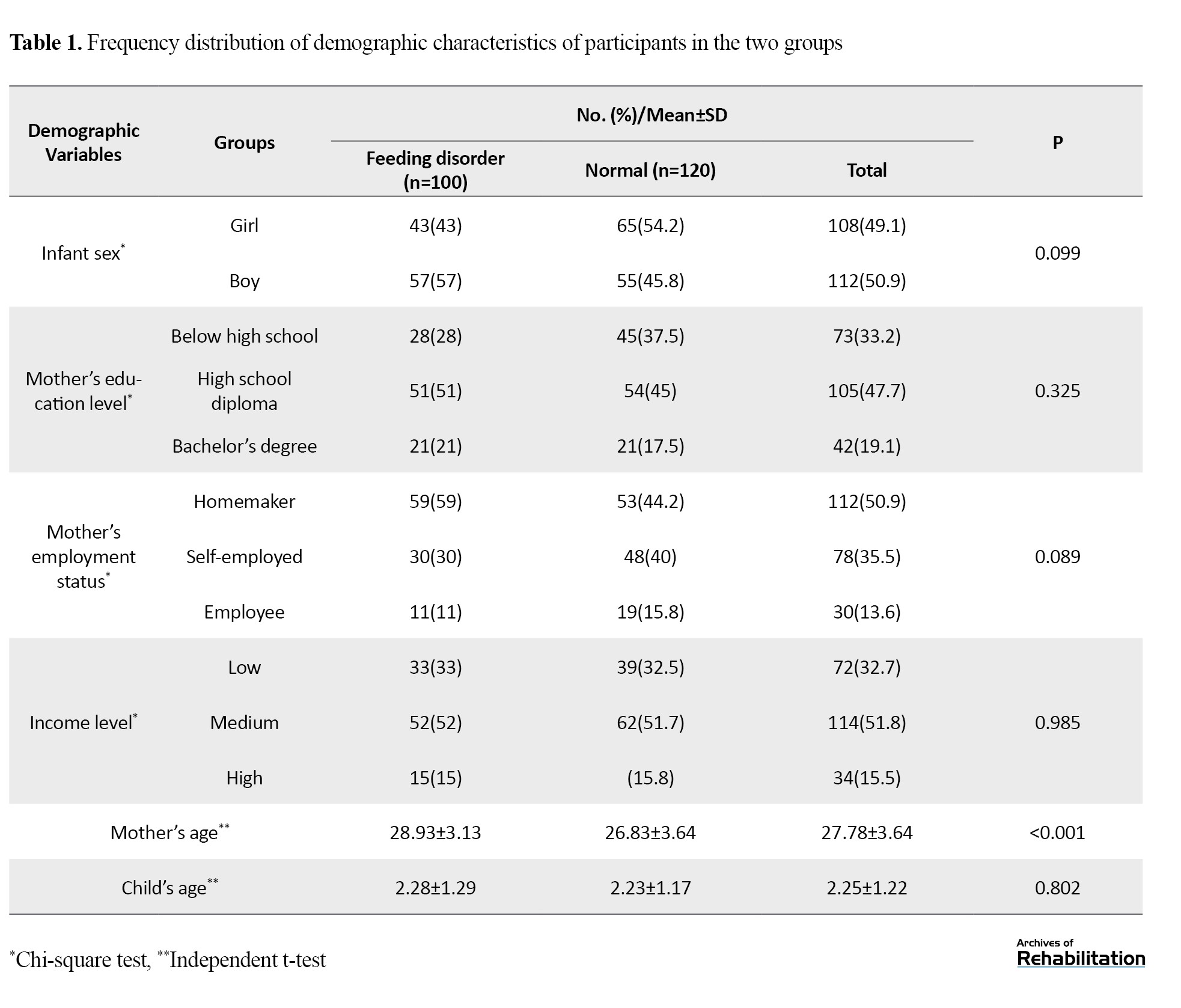

This study was conducted on 220 children aged 0–4 years, including 100 children with feeding disorders and 120 typically developing children, as determined by the ASQ form and pediatrician evaluation. Participants’ demographic characteristics, including child’s sex, mother’s education and employment status, family income, and mean age of mothers and children, are summarized in Table 1.

This information was collected via the demographic questionnaire and direct parental responses. The characteristics of the speech therapists who collected the data included ages ranging from 29 to 50 years, educational levels from bachelor’s to doctoral degrees, and work experience of 5 to 20 years. Due to the limited number of participating therapists and the simplicity of the data, the information was reported in text form, and no separate table was provided. Forward translation and panel reviews led to the revision of items and confirmed the accuracy of concept transfer, language clarity, and cultural appropriateness, resulting in a final version ready for psychometric evaluation.

Results from the cognitive interviews indicated that most items were understandable to parents, with only a few requiring minor modifications. The applied revisions included the following:

Item 1: Changed from “Does your infant/child show interest in drinking milk/food?” to “Does your infant/child like to drink milk/eat food?”

Item 3: Changed from “Does your infant/child do anything when hungry?” to “Does your infant/child show you when they are hungry?”

Item 10: Changed from “Do you feel satisfied when feeding your infant/child?” to “Do you enjoy the time you spend feeding your infant/child?”

The average time for parents to complete the questionnaire was approximately 5–7 minutes, and most parents reported that the questionnaire was neither lengthy nor difficult. These revisions enhanced the clarity and cultural consistency of the Persian version, facilitating its preparation for subsequent psychometric evaluation.

Content validity of the ICFQ

Content validity of the questionnaire was evaluated using the CVI and CVR indices by 10 speech-language pathologists. The I-CVI values for all items were above 0.8, and the overall S-CVI was 0.95, indicating a high level of agreement among experts and satisfactory content adequacy of the Persian version. Additionally, a good conceptual alignment between the Persian version and the original questionnaire was confirmed.

Construct validity of the ICFQ

Known-groups validity

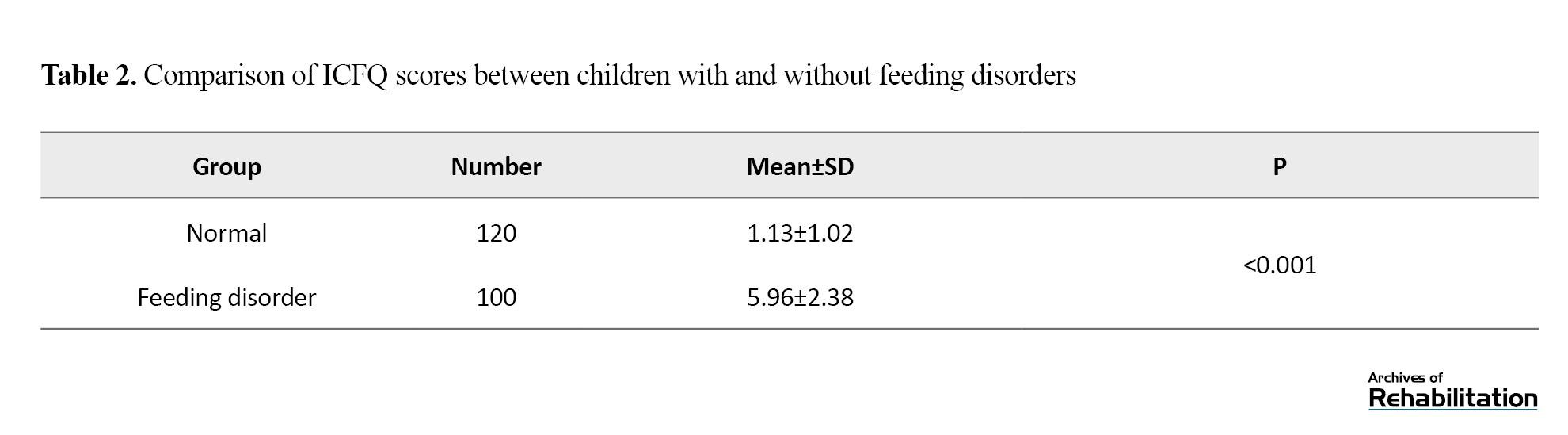

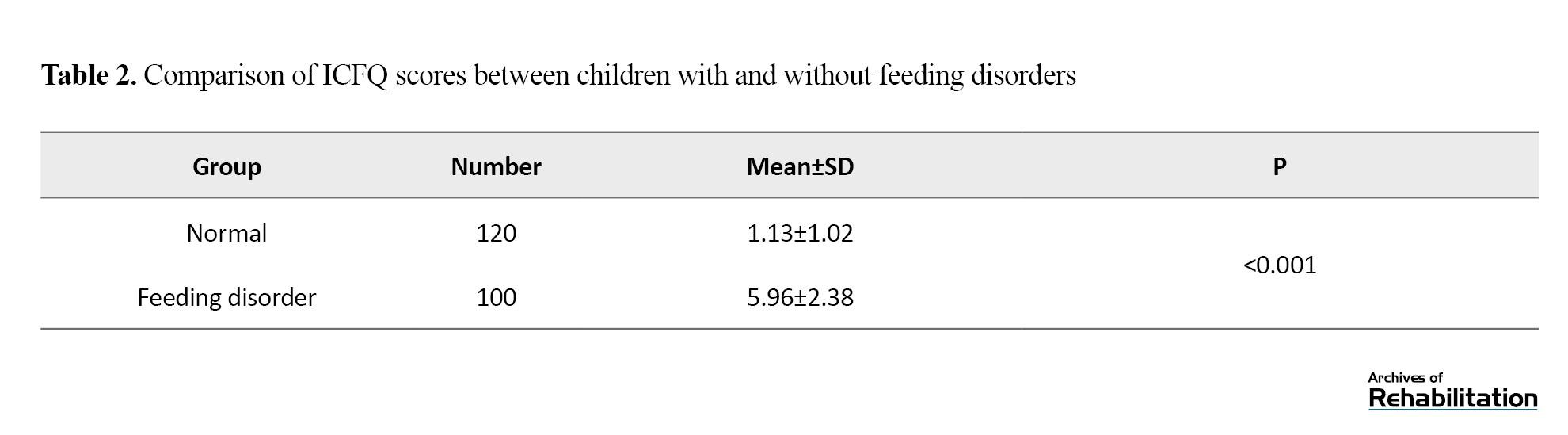

To assess known-groups validity, the mean total ICFQ scores were compared between children with feeding disorders and typically developing children using an independent t-test. As shown in Table 2, a significant difference was observed between the scores of the two groups (P<0.001).

Convergent validity

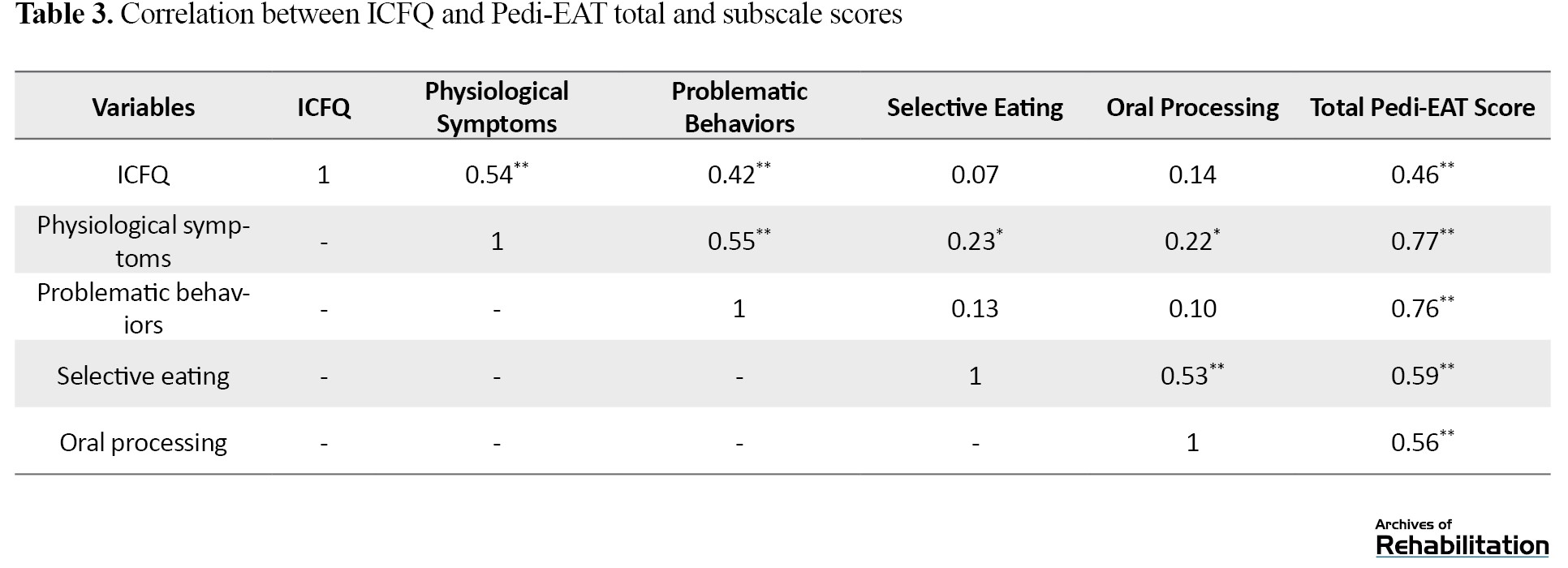

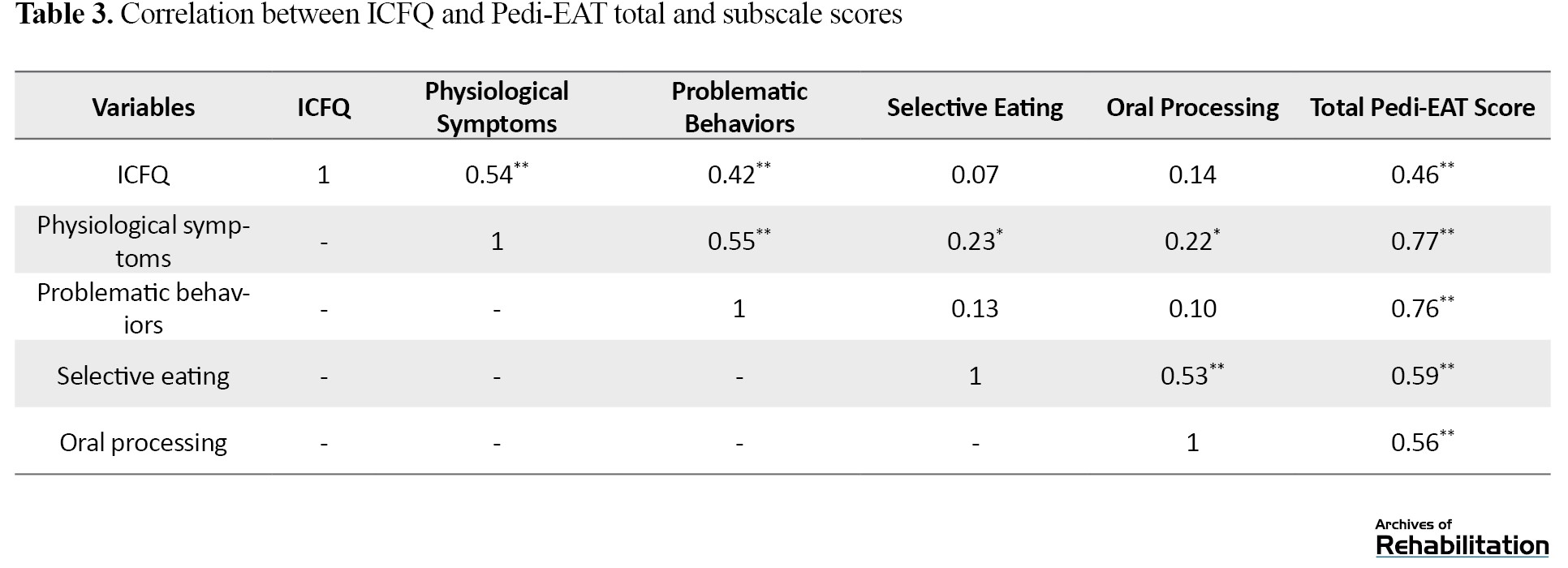

Correlation analysis indicated that the ICFQ questionnaire had a significant positive correlation with the total score of the Pedi-EAT (r=0.46, P<0.01). The correlation analysis included the relationship between the ICFQ and the total Pedi-EAT score as well as correlations between the ICFQ and various subscales of the Pedi-EAT. Furthermore, the ICFQ demonstrated significant correlations with the physiological symptoms subscale (r=0.54, P<0.01) and the problematic mealtime behaviors subscale (r=0.46, P<0.01) of the Pedi-EAT questionnaire (Table 3).

Diagnostic accuracy and cut-off determination of the ICFQ

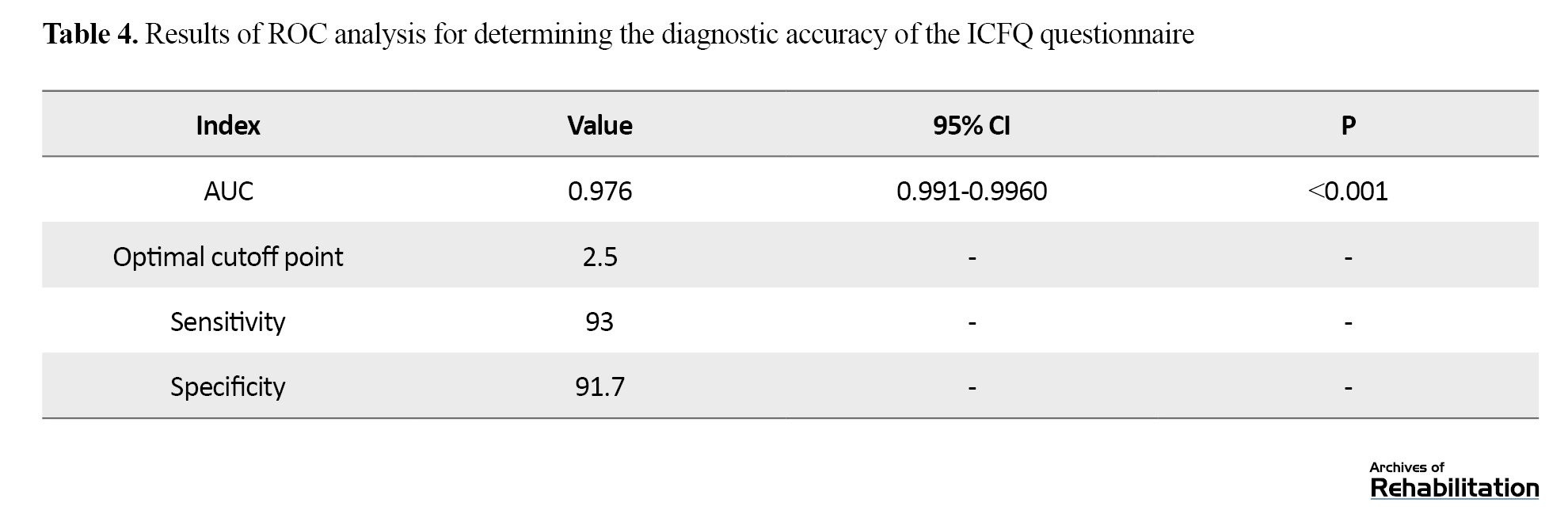

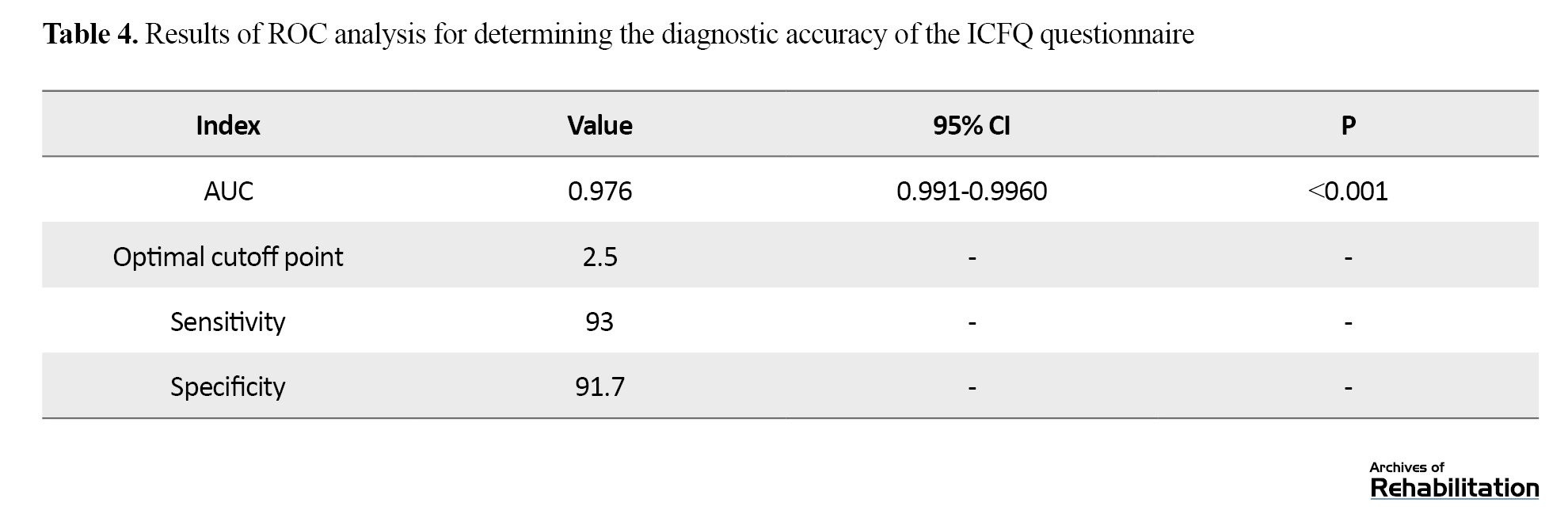

Based on ROC curve analysis, the sensitivity and specificity of the ICFQ were 93% and 91.7%, respectively (Figure 1). The optimal cut-off point for the instrument was determined to be 2.5. The AUC was 0.97, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.96 to 0.99, indicating very high accuracy of the instrument (P<0.001) (Table 4).

Criterion validity of the ICFQ

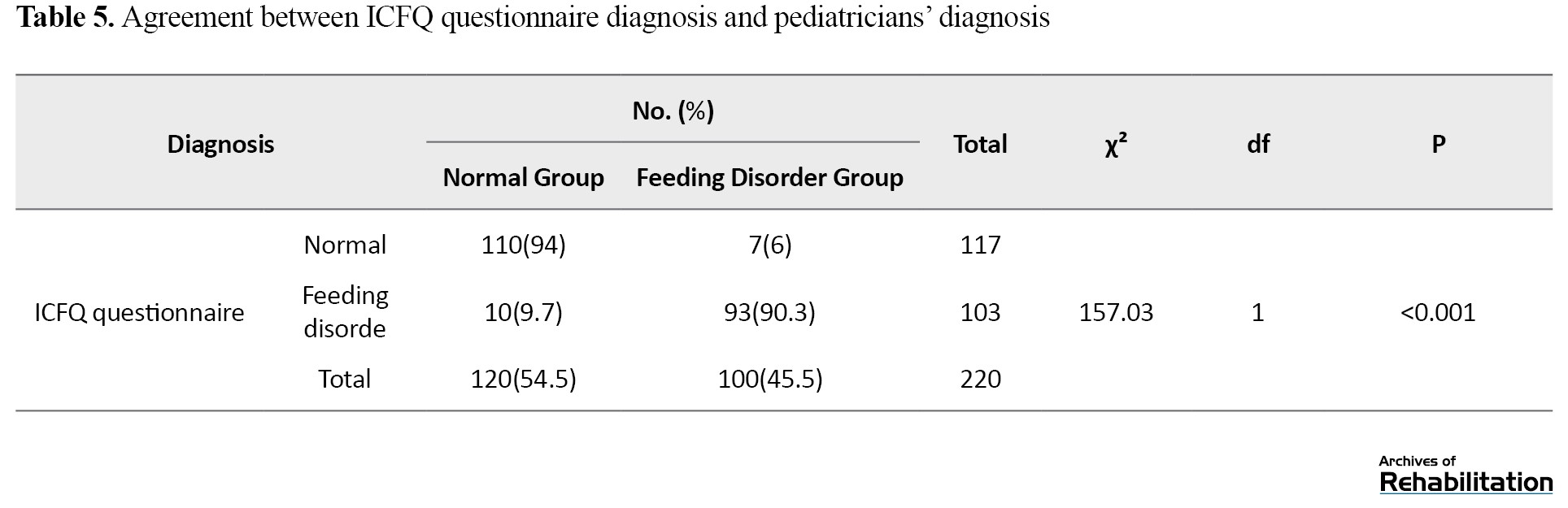

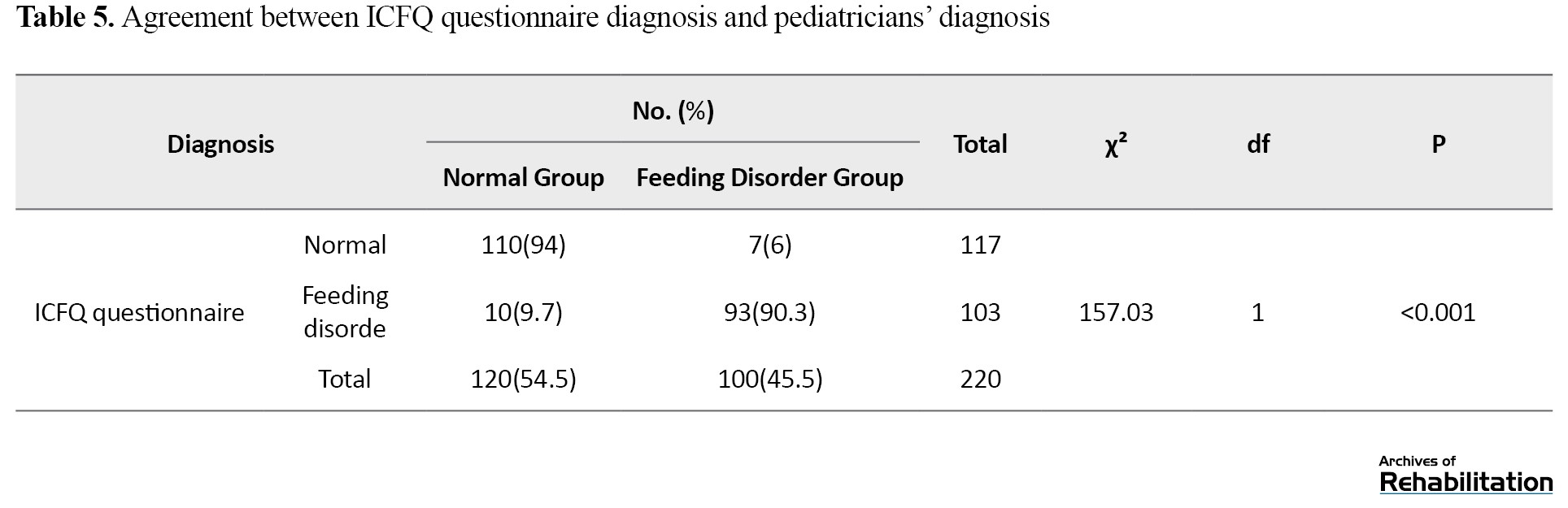

Chi-square analysis showed a significant agreement between ICFQ-based diagnoses and pediatrician evaluations in identifying children with feeding disorders (χ²=157.03, df=1, P<0.001). Specifically, the questionnaire agreed with pediatrician diagnoses in 90.3% of cases (93 out of 103 children). Additionally, 94% agreement was observed in identifying typically developing children (110 out of 117 children) (Table 5).

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was the translation, cultural adaptation, and psychometric evaluation of the Persian version of the ICFQ. The 12-item ICFQ, focusing on parent-observable feeding behaviors, maintains the efficiency of the instrument while being practical in terms of time and comprehensibility for both parents and clinicians. The translation and validation process followed international guidelines, and results indicated that the Persian version was clear and understandable for parents, who were able to respond to the items without ambiguity; notably, there were no complex or technical terms in the questionnaire. Furthermore, due to the small number of items (12 questions), the questionnaire could be completed in a very short time, which represents an important clinical advantage. According to the literature, questionnaires that can be completed in less than 5 minutes are considered rapid and efficient tools, and the ICFQ, with an average completion time of 5–7 minutes, is very close to this category. This advantage, combined with the simplicity of the items, is particularly valuable, as even short questionnaires in other instruments may be time-consuming if the items are conceptually complex [23].

In terms of content validity, all items of the questionnaire demonstrated acceptable CVI levels, and the overall S-CVI indicated excellent alignment of the Persian version with the original. This level of content validity, based on commonly used psychometric indices, falls within the “excellent” range and is consistent with reports from similar studies [24]. These results are in line with findings from Nasirzadeh et al. [25] and Dasht Bozorgi et al. [26] on the CEBQ, which employed similar validation methods, although CVI values were not reported in those studies. Additionally, Mehdizadeh et al. [27], in the validation of NutriSTEP, used CVI to assess content validity and reported high values.

In the assessment of construct validity, known-groups analysis demonstrated that the ICFQ could significantly differentiate children with feeding disorders from typically developing children. A significant difference was observed between the scores of the two groups (P<0.001), indicating the discriminative power of the ICFQ in identifying feeding disorders in children. Furthermore, a significant correlation was found between ICFQ scores and the Persian version of the validated Pedi-EAT questionnaire, confirming acceptable convergent validity of the Persian version. This finding suggests that the two instruments partially measure overlapping dimensions of feeding problems. The results indicate that the ICFQ demonstrates good convergent validity, particularly in assessing physiological and behavioral aspects of feeding difficulties. However, the low correlation with the “picky eating” and “oral processing” subscales suggests that the questionnaire may capture different dimensions of feeding problems compared to the Pedi-EAT. These findings are consistent with Pados et al. [15], who reported a high correlation between Pedi-EAT and the MBQ in their study.

In the original ICFQ, construct validity was only partially examined, and correlations with validated instruments were not reported. In other studies, Nasirzadeh and Dasht Bozorgi assessed the construct validity of the CEBQ using exploratory factor analysis, extracting six and seven factors, respectively. Additionally, Camcı et al. [28] confirmed construct validity of the Turkish CFQ through factor analysis, reporting a seven-factor structure. Comparison of these findings indicates that, although the number of factors varies across instruments, convergence among subscales related to feeding behaviors is generally observed. It should be noted that due to the characteristics of the Persian ICFQ, including its limited 12 items and predominantly dichotomous responses, factor analysis was not appropriate for assessing the factor structure. Factor analysis is typically applicable when there is a sufficient number of items to extract subscales or latent factors; in the short version of the ICFQ, the small number of items and the defined structure of the original version limit the possibility of extracting reliable factors [29]. Therefore, to assess construct validity, the approaches of comparing mean scores between known groups and evaluating correlations with the validated Pedi-EAT were chosen as scientifically appropriate and commonly used methods for short, dichotomous instruments.

In assessing criterion validity, the results indicated a strong agreement between the ICFQ’s classification of children with feeding problems and the pediatricians’ clinical diagnoses. Most of the children identified by the questionnaire as having feeding difficulties were likewise diagnosed by pediatric specialists, demonstrating satisfactory criterion validity of the Persian version. In the original ICFQ, qualitative concordance with expert judgment was reported, but no numerical indices were provided. Similarly, other comparable instruments, such as the NutriSTEP [27], Pedi-EAT [15], and CEBQ [25], have also employed expert judgment to evaluate criterion validity; however, the degree of agreement in those studies was not reported quantitatively and was primarily based on professional assessment.

In the analysis of diagnostic accuracy, the ROC curve results demonstrated that the Persian version of the ICFQ exhibited satisfactory sensitivity, specificity, and a substantial AUC, indicating the strong diagnostic power and high capability of the questionnaire in distinguishing between typically developing children and those with feeding disorders. Compared with the original version reported by Silverman et al. [17], in which diagnostic indices were presented only for the 6-item version, the performance of the 12-item Persian version showed improved ability of the tool to correctly differentiate between groups.

In the study by Silverman et al. [17], the analysis of diagnostic accuracy was conducted only for the shortened 6-item version, and no specific cutoff point was reported for the 12-item ICFQ. However, in the present study, the 12-item version was used with the aim of providing a more comprehensive screening of children’s feeding behaviors. This version encompasses a wider range of subscales, allowing the evaluation of a broader spectrum of feeding difficulties and offering greater content richness. Furthermore, the 12-item version enables a more detailed analysis of different aspects of child feeding behavior and provides higher discriminative power in identifying children with feeding disorders. Based on the findings of the present study, the optimal cutoff point for the Persian version of the ICFQ was determined to be 2.5, at which the questionnaire demonstrated high accuracy in distinguishing children with feeding difficulties from typically developing peers.

Finally, it is recommended that future studies examine the outcomes of using this instrument in primary healthcare centers for screening of children’s feeding status. In addition to determining the prevalence of feeding disorders during the screening phase, future research should also investigate the impact of early identification of these disorders on children’s developmental outcomes. Moreover, the concurrent use of the ICFQ with other validated instruments could allow for a more comprehensive and multidimensional evaluation and assessment of pediatric feeding problems and provide more complete information to support clinical and public health decision-making.

Conclusion

The Persian version of the ICFQ demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties and proved to be a valid and efficient screening tool for the early identification of feeding disorders in children aged 0–4 years. With an average completion time of approximately 5–7 minutes, this questionnaire allows for the rapid early detection of feeding difficulties and facilitates timely referral to specialists for comprehensive evaluation and assessment. The Persian version also showed superior diagnostic accuracy compared to the original version in certain aspects, suggesting its potential utility as a brief monitoring and screening instrument in health centers and primary care settings for exploring children’s feeding and growth status.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences under the ethics code IR.USWR.REC.1403.130. All procedures were conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines. Confidentiality and data privacy were strictly observed throughout the study. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians. The participants were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This study was extracted from the Master’s thesis of Tayebe Faqihi at the Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design, resources, writing the initial draft: Tayebe Faqihi, Zahra Sadat Gharishi, and Maryam Mokhlesin; Project management and supervision: Zahra Sadeghi and Zahra Sadat Gharishi; methodology, validation, and editing: Zahra Sadeghi, Mohsen Vahedi, Tayebe Faqihi, Pouran Bagherpour; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

Adequate nutrition during infancy and early childhood is a fundamental component of growth and overall health. Evidence indicates that optimal feeding not only influences physical growth but also plays a crucial role in cognitive, emotional, and social development [1]. Nevertheless, pediatric feeding disorders are recognized as a significant global health challenge, with reported prevalence rates of 25–45% in typically developing children and up to 80% in children with special needs [2, 3]. The consequences of these disorders can manifest in both short- and long-term outcomes. In the short term, issues such as growth delays and increased susceptibility to infections are observed, whereas long-term consequences may include cognitive impairments and chronic medical conditions [4, 5]. Pediatric feeding disorders may result in serious nutritional, developmental, and psychological complications, and if not diagnosed and managed promptly, these problems can progressively worsen and may even lead to mortality [2, 6]. A particularly concerning issue is that the diagnosis of these disorders is often delayed until 2–4 years of age [7], which can have irreversible effects on the child’s growth and the family’s quality of life [8–10]. The key strategy to prevent these outcomes lies in early identification and timely intervention for feeding disorders (from birth and within the first two years of life) [11, 12]. Implementing any timely intervention requires the availability of appropriate assessment tools.

Currently, several instruments are available for assessing children’s feeding behaviors. The child eating behavior questionnaire (CEBQ), whose Persian version has been evaluated in Iran for children aged 1–5 years, demonstrates acceptable reliability (Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.71 to 0.83) and adequate construct validity (explaining over 50% of the variance across multiple factors). However, due to the large number of items, its administration is relatively time-consuming, and it is not applicable for children under one year of age [13]. The screening tool for eating problems (STEP) consists of 23 items and is completed by psychologists or therapists who have worked with the patient for at least six months. This instrument was designed for the rapid identification of feeding problems in individuals with intellectual disabilities and has demonstrated acceptable inter-rater reliability and construct validity in previous evaluations [14].

Additionally, the pediatric eating assessment tool (Pedi-EAT) is available, with its Persian version used to assess feeding behaviors in children up to seven years of age. This tool comprises four subscales, with Cronbach’s α ranging from 0.83 to 0.92 and strong test-retest reliability (r=0.95), although its completion is also time-consuming [15]. Another instrument with a Persian version is the anderson dysphagia inventory (MDADI), designed to evaluate the quality of life in patients with dysphagia. Nevertheless, many of the existing instruments are not suitable for children under six months of age and are relatively time-consuming and complex to administer. Therefore, there is a need to develop a brief, valid, and practical questionnaire for initial screening in this population [16]. Notably, none of these tools cover children under six months, highlighting the necessity for a short, valid, and appropriate instrument for early screening in Persian-speaking infants under six months of age.

The infant and child feeding questionnaire (ICFQ) is a parent-report screening tool developed by Silverman and colleagues for children aged 0–4 years, aimed at the early identification of warning signs related to feeding. The questionnaire consists of 12 items completed by parents, which, through the evaluation of behavioral patterns and feeding-related indicators, enables the preliminary detection of feeding disorders. With its simple and easily comprehensible design, the ICFQ can be administered in both clinical and care settings by parents and professionals. The original version of this tool demonstrated favorable psychometric properties. Silverman confirmed its construct validity through comparisons between two known groups (children with feeding disorders and children without disorders). Additionally, criterion validity was supported by significant correlations with expert evaluations. receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis indicated that the questionnaire exhibits notable diagnostic accuracy in identifying cases requiring referral, with high sensitivity and specificity [17]. Key advantages of the ICFQ include: Samall number of items, reliance on parent-report, and coverage of infants under six months, making it suitable for cultural adaptation in the Iranian population and highly practical for early screening of feeding disorders in clinical and research settings. Therefore, the present study was conducted to translate and adapt the ICFQ into Persian and evaluate its psychometric properties.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This methodological study was conducted to translate and validate a screening tool for feeding disorders in Persian-speaking children. The study employed a cross-sectional design with two distinct groups of participants, including children with feeding disorders and typically developing children, along with their parents. The sample size was determined based on the sensitivity and specificity of the original version, comprising 220 children (100 children with feeding disorders and 120 typically developing children). Participants were recruited through convenience sampling from children aged 0–4 years whose at least one parent was fluent in Persian. Inclusion criteria for the feeding disorder group were a diagnosis of feeding disorder by a pediatrician, whereas for the typically developing group, children were included if they demonstrated normal development according to the ages and stages questionnaire (ASQ) and pediatrician evaluation, with no medical conditions predisposing them to feeding problems (e.g. surgical or traumatic injury, pneumonia, chronic dehydration, malnutrition, seizures, etc.). Exclusion criteria for both groups included incomplete questionnaire responses, parents withdrawal from participation, or loss of eligibility criteria for either the parent or the child. Prior to administration of the questionnaire to parents, the face and content validity of the instrument were assessed by 10 experienced speech-language pathologists.

Research instrument

The ICFQ, consisting of 12 items, was the primary instrument for this study [17]. This questionnaire completed by parents using yes/no responses, except for item 5, which includes two options “less than 5 minutes” and “more than 30 minutes” to assess feeding duration, and item 11, which is multiple-choice and allows parents to mark more than one behavior. All other items are scored dichotomously (yes/no). Scoring, except for item 11, is based on the presence or absence of warning behaviors: a score of 1 is assigned if the behavior is observed, and 0 if not. Item 11 is not included in the total score and is used solely for clinical referral purposes. Parents read the items and complete the questionnaire, and may ask the interviewer any questions if needed. The total score of the instrument is calculated by summing responses, excluding item 11. This scoring structure allows determination of a cut-off point for identifying children at risk of feeding disorders and provides clarity regarding the total score calculation and its relation to parental responses. Silverman’s study demonstrated that the questionnaire possesses favorable psychometric properties, with indicators such as area under the curve (AUC), sensitivity (73%), and specificity (93%) [17]. When two or more items are endorsed, sensitivity decreases while specificity increases. Furthermore, the behaviors included in the questionnaire can assist in identifying children requiring prompt referral to specialists.

Procedure

This study was conducted from December 2024 to June 2025. The methods employed included translation, cognitive interviews, evaluation of face and content validity, construct and criterion validity, descriptive analyses, and diagnostic accuracy assessment, following procedures similar to those used in previous studies [18, 19]. After obtaining permission for translation from the original questionnaire developer, the process of translating and culturally adapting the ICFQ was conducted in accordance with World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines for the cultural adaptation of assessment instruments [20]. This protocol includes four main steps: forward translation, assessment of face and content validity, backward translation, and face validity assessment (cognitive interviews). In the forward translation phase, the questionnaire was independently translated by two speech-language pathologists whose native language was Persian and who were proficient in English. Subsequently, a third speech-language pathologist who was also proficient in English compared the two translations, analyzed discrepancies, and prepared the initial merged version. In the next step, two separate expert panels were established to assess face and content validity: the first panel included three specialists (the two original SLP translators and a nutritionist) who supervised the accurate transfer of concepts, precision of technical terminology, and clarity of language. After initial approval, the translated version was presented to a second panel consisting of 10 speech-language pathologists with varying educational backgrounds. This group carefully reviewed the items in terms of comprehensibility, simplicity, and cultural appropriateness. Then, they provided suggestions to improve the structure and content of the questionnaire.

To assess content validity, a quantitative approach based on the framework proposed by Waltz and Basel was employed, concurrently with the evaluation of face validity, similar to previous studies [21, 22]. In this phase, the questionnaire was independently reviewed by 10 experienced speech-language pathologists specialized in pediatric feeding disorders. Then, they rated the adequacy of each item based on three indices: clarity, relevance, and simplicity, using a four-point Likert scale (1=not suitable to 4=highly suitable). The use of a four-point scale in this step follows common procedures in content validity assessment, aiming to reduce midpoint responses and facilitate expert judgment. The item-level content validity index (I-CVI) was calculated with the ratio of the number of experts who gave a score of 3 or 4 to that item to the total number of raters. Values above 0.79 were considered acceptable. Additionally, the scale-level content validity index (S-CVI) was calculated using the average of I-CVIs across all items (S-CVI/Ave).

For backward translation, the Persian version of the questionnaire was translated back into English by a fourth translator who was proficient in English and blinded to the original version. The translated version was then compared with the original questionnaire to ensure conceptual equivalence and cultural adaptation. This step ensures that the core concepts of the questionnaire are preserved in the Persian version and are consistent with the original version.

To assess face validity and ensure clarity and comprehensibility of the translated version in the target population, cognitive interviews were conducted with 10 Persian-speaking parents of children aged 0–4 years (3 parents of children with feeding disorders and 7 parents of typically developing children). Parents read the questionnaire aloud and shared their interpretations, ambiguities, and suggestions. This process led to revisions of certain expressions, simplification of language, and improvement of the cultural appropriateness of the instrument, confirming that the Persian version was conceptually and linguistically understandable for respondents.

After preparing the Persian version of the questionnaire, data were collected from health centers, developmental clinics, and kindergartens in Qom. Parents completed the consent form and a demographic information questionnaire. For children with feeding disorders, participants were recruited through referrals by pediatricians based at comprehensive developmental centers, and feeding problems were confirmed by pediatric evaluation prior to questionnaire administration. For the typically developing group, some participants were directly selected from staff kindergartens affiliated with the comprehensive developmental centers, where pediatricians confirmed their health and nutritional status. Other typically developing children from different kindergartens were referred to pediatricians at the comprehensive developmental centers for health and nutritional assessment before entering the study. Subsequently, all children in the typically developing group completed the ASQ form to ensure developmental and nutritional health. Additionally, pediatrician evaluations in both groups were considered to confirm health status and diagnosis of feeding disorders. The Persian version of the ICFQ was completed by parents in both groups, while the Pedi-EAT questionnaire was administered only to children with feeding disorders to assess the construct validity of the Persian ICFQ. Questionnaires were completed in a quiet, undisturbed environment at the comprehensive developmental center or in the kindergartens. Parents personally filled out the questionnaires after receiving the necessary explanations, with the researcher present if clarification was needed. Completing each questionnaire took an average of 5 to 7 minutes.

Construct validity was assessed using two approaches. First, known-groups validity was evaluated by comparing the mean ICFQ scores between children with feeding disorders and typically developing children. Next, convergent validity was examined by calculating the correlation between ICFQ scores and the Persian version of the validated Pedi-EAT questionnaire, which assesses feeding status in children. Criterion validity was also evaluated by comparing questionnaire results with pediatrician diagnoses. Finally, to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the instrument, ROC curve analysis was conducted to assess the questionnaire’s ability to discriminate between children with feeding disorders and typically developing children. Based on the ROC curve, the optimal cut-off point was identified, and the sensitivity and specificity of the tool at this threshold were calculated. In this analysis, pediatrician diagnosis was considered the gold standard for determining the presence or absence of feeding disorders in children.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis in this study was conducted at both descriptive and inferential levels. Initially, descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage, were used to summarize participants’ demographic characteristics and questionnaire scores.

At the inferential level, construct validity was assessed using known-groups validity and convergent validity. For known-groups validity, an independent t-test was used to compare mean ICFQ scores between children with feeding disorders and typically developing children. For convergent validity, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated between ICFQ scores and the Pedi-EAT questionnaire and its subscales. Criterion validity was evaluated using the Chi-square test to compare questionnaire results with pediatrician diagnoses. To determine the diagnostic accuracy of the instrument, ROC curve analysis was performed, and sensitivity, specificity, and the optimal cut-off point were reported. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25, with a significance level set at P<0.05 for all tests.

Results

This study was conducted on 220 children aged 0–4 years, including 100 children with feeding disorders and 120 typically developing children, as determined by the ASQ form and pediatrician evaluation. Participants’ demographic characteristics, including child’s sex, mother’s education and employment status, family income, and mean age of mothers and children, are summarized in Table 1.

This information was collected via the demographic questionnaire and direct parental responses. The characteristics of the speech therapists who collected the data included ages ranging from 29 to 50 years, educational levels from bachelor’s to doctoral degrees, and work experience of 5 to 20 years. Due to the limited number of participating therapists and the simplicity of the data, the information was reported in text form, and no separate table was provided. Forward translation and panel reviews led to the revision of items and confirmed the accuracy of concept transfer, language clarity, and cultural appropriateness, resulting in a final version ready for psychometric evaluation.

Results from the cognitive interviews indicated that most items were understandable to parents, with only a few requiring minor modifications. The applied revisions included the following:

Item 1: Changed from “Does your infant/child show interest in drinking milk/food?” to “Does your infant/child like to drink milk/eat food?”

Item 3: Changed from “Does your infant/child do anything when hungry?” to “Does your infant/child show you when they are hungry?”

Item 10: Changed from “Do you feel satisfied when feeding your infant/child?” to “Do you enjoy the time you spend feeding your infant/child?”

The average time for parents to complete the questionnaire was approximately 5–7 minutes, and most parents reported that the questionnaire was neither lengthy nor difficult. These revisions enhanced the clarity and cultural consistency of the Persian version, facilitating its preparation for subsequent psychometric evaluation.

Content validity of the ICFQ

Content validity of the questionnaire was evaluated using the CVI and CVR indices by 10 speech-language pathologists. The I-CVI values for all items were above 0.8, and the overall S-CVI was 0.95, indicating a high level of agreement among experts and satisfactory content adequacy of the Persian version. Additionally, a good conceptual alignment between the Persian version and the original questionnaire was confirmed.

Construct validity of the ICFQ

Known-groups validity

To assess known-groups validity, the mean total ICFQ scores were compared between children with feeding disorders and typically developing children using an independent t-test. As shown in Table 2, a significant difference was observed between the scores of the two groups (P<0.001).

Convergent validity

Correlation analysis indicated that the ICFQ questionnaire had a significant positive correlation with the total score of the Pedi-EAT (r=0.46, P<0.01). The correlation analysis included the relationship between the ICFQ and the total Pedi-EAT score as well as correlations between the ICFQ and various subscales of the Pedi-EAT. Furthermore, the ICFQ demonstrated significant correlations with the physiological symptoms subscale (r=0.54, P<0.01) and the problematic mealtime behaviors subscale (r=0.46, P<0.01) of the Pedi-EAT questionnaire (Table 3).

Diagnostic accuracy and cut-off determination of the ICFQ

Based on ROC curve analysis, the sensitivity and specificity of the ICFQ were 93% and 91.7%, respectively (Figure 1). The optimal cut-off point for the instrument was determined to be 2.5. The AUC was 0.97, with a 95% confidence interval ranging from 0.96 to 0.99, indicating very high accuracy of the instrument (P<0.001) (Table 4).

Criterion validity of the ICFQ

Chi-square analysis showed a significant agreement between ICFQ-based diagnoses and pediatrician evaluations in identifying children with feeding disorders (χ²=157.03, df=1, P<0.001). Specifically, the questionnaire agreed with pediatrician diagnoses in 90.3% of cases (93 out of 103 children). Additionally, 94% agreement was observed in identifying typically developing children (110 out of 117 children) (Table 5).

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was the translation, cultural adaptation, and psychometric evaluation of the Persian version of the ICFQ. The 12-item ICFQ, focusing on parent-observable feeding behaviors, maintains the efficiency of the instrument while being practical in terms of time and comprehensibility for both parents and clinicians. The translation and validation process followed international guidelines, and results indicated that the Persian version was clear and understandable for parents, who were able to respond to the items without ambiguity; notably, there were no complex or technical terms in the questionnaire. Furthermore, due to the small number of items (12 questions), the questionnaire could be completed in a very short time, which represents an important clinical advantage. According to the literature, questionnaires that can be completed in less than 5 minutes are considered rapid and efficient tools, and the ICFQ, with an average completion time of 5–7 minutes, is very close to this category. This advantage, combined with the simplicity of the items, is particularly valuable, as even short questionnaires in other instruments may be time-consuming if the items are conceptually complex [23].

In terms of content validity, all items of the questionnaire demonstrated acceptable CVI levels, and the overall S-CVI indicated excellent alignment of the Persian version with the original. This level of content validity, based on commonly used psychometric indices, falls within the “excellent” range and is consistent with reports from similar studies [24]. These results are in line with findings from Nasirzadeh et al. [25] and Dasht Bozorgi et al. [26] on the CEBQ, which employed similar validation methods, although CVI values were not reported in those studies. Additionally, Mehdizadeh et al. [27], in the validation of NutriSTEP, used CVI to assess content validity and reported high values.

In the assessment of construct validity, known-groups analysis demonstrated that the ICFQ could significantly differentiate children with feeding disorders from typically developing children. A significant difference was observed between the scores of the two groups (P<0.001), indicating the discriminative power of the ICFQ in identifying feeding disorders in children. Furthermore, a significant correlation was found between ICFQ scores and the Persian version of the validated Pedi-EAT questionnaire, confirming acceptable convergent validity of the Persian version. This finding suggests that the two instruments partially measure overlapping dimensions of feeding problems. The results indicate that the ICFQ demonstrates good convergent validity, particularly in assessing physiological and behavioral aspects of feeding difficulties. However, the low correlation with the “picky eating” and “oral processing” subscales suggests that the questionnaire may capture different dimensions of feeding problems compared to the Pedi-EAT. These findings are consistent with Pados et al. [15], who reported a high correlation between Pedi-EAT and the MBQ in their study.

In the original ICFQ, construct validity was only partially examined, and correlations with validated instruments were not reported. In other studies, Nasirzadeh and Dasht Bozorgi assessed the construct validity of the CEBQ using exploratory factor analysis, extracting six and seven factors, respectively. Additionally, Camcı et al. [28] confirmed construct validity of the Turkish CFQ through factor analysis, reporting a seven-factor structure. Comparison of these findings indicates that, although the number of factors varies across instruments, convergence among subscales related to feeding behaviors is generally observed. It should be noted that due to the characteristics of the Persian ICFQ, including its limited 12 items and predominantly dichotomous responses, factor analysis was not appropriate for assessing the factor structure. Factor analysis is typically applicable when there is a sufficient number of items to extract subscales or latent factors; in the short version of the ICFQ, the small number of items and the defined structure of the original version limit the possibility of extracting reliable factors [29]. Therefore, to assess construct validity, the approaches of comparing mean scores between known groups and evaluating correlations with the validated Pedi-EAT were chosen as scientifically appropriate and commonly used methods for short, dichotomous instruments.

In assessing criterion validity, the results indicated a strong agreement between the ICFQ’s classification of children with feeding problems and the pediatricians’ clinical diagnoses. Most of the children identified by the questionnaire as having feeding difficulties were likewise diagnosed by pediatric specialists, demonstrating satisfactory criterion validity of the Persian version. In the original ICFQ, qualitative concordance with expert judgment was reported, but no numerical indices were provided. Similarly, other comparable instruments, such as the NutriSTEP [27], Pedi-EAT [15], and CEBQ [25], have also employed expert judgment to evaluate criterion validity; however, the degree of agreement in those studies was not reported quantitatively and was primarily based on professional assessment.

In the analysis of diagnostic accuracy, the ROC curve results demonstrated that the Persian version of the ICFQ exhibited satisfactory sensitivity, specificity, and a substantial AUC, indicating the strong diagnostic power and high capability of the questionnaire in distinguishing between typically developing children and those with feeding disorders. Compared with the original version reported by Silverman et al. [17], in which diagnostic indices were presented only for the 6-item version, the performance of the 12-item Persian version showed improved ability of the tool to correctly differentiate between groups.

In the study by Silverman et al. [17], the analysis of diagnostic accuracy was conducted only for the shortened 6-item version, and no specific cutoff point was reported for the 12-item ICFQ. However, in the present study, the 12-item version was used with the aim of providing a more comprehensive screening of children’s feeding behaviors. This version encompasses a wider range of subscales, allowing the evaluation of a broader spectrum of feeding difficulties and offering greater content richness. Furthermore, the 12-item version enables a more detailed analysis of different aspects of child feeding behavior and provides higher discriminative power in identifying children with feeding disorders. Based on the findings of the present study, the optimal cutoff point for the Persian version of the ICFQ was determined to be 2.5, at which the questionnaire demonstrated high accuracy in distinguishing children with feeding difficulties from typically developing peers.

Finally, it is recommended that future studies examine the outcomes of using this instrument in primary healthcare centers for screening of children’s feeding status. In addition to determining the prevalence of feeding disorders during the screening phase, future research should also investigate the impact of early identification of these disorders on children’s developmental outcomes. Moreover, the concurrent use of the ICFQ with other validated instruments could allow for a more comprehensive and multidimensional evaluation and assessment of pediatric feeding problems and provide more complete information to support clinical and public health decision-making.

Conclusion

The Persian version of the ICFQ demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties and proved to be a valid and efficient screening tool for the early identification of feeding disorders in children aged 0–4 years. With an average completion time of approximately 5–7 minutes, this questionnaire allows for the rapid early detection of feeding difficulties and facilitates timely referral to specialists for comprehensive evaluation and assessment. The Persian version also showed superior diagnostic accuracy compared to the original version in certain aspects, suggesting its potential utility as a brief monitoring and screening instrument in health centers and primary care settings for exploring children’s feeding and growth status.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences under the ethics code IR.USWR.REC.1403.130. All procedures were conducted in accordance with ethical guidelines. Confidentiality and data privacy were strictly observed throughout the study. Informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians. The participants were free to leave the study at any time.

Funding

This study was extracted from the Master’s thesis of Tayebe Faqihi at the Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Study design, resources, writing the initial draft: Tayebe Faqihi, Zahra Sadat Gharishi, and Maryam Mokhlesin; Project management and supervision: Zahra Sadeghi and Zahra Sadat Gharishi; methodology, validation, and editing: Zahra Sadeghi, Mohsen Vahedi, Tayebe Faqihi, Pouran Bagherpour; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all participants for their cooperation in this study.

References

- World Health Organization. Nutrition [Internet]. 2019 [Updated 2025 July 10]. Available from: [Link]

- Manikam R, Perman JA. Pediatric feeding disorders. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2000; 30(1):34-46. [DOI:10.1097/00004836-200001000-00007] [PMID]

- Kerzner B, Milano K, MacLean WC Jr, Berall G, Stuart S, Chatoor I. A practical approach to classifying and managing feeding difficulties. Pediatrics. 2015; 135(2):344-53. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2014-1630] [PMID]

- Uauy R, Kain J, Corvalan C. How can the developmental origins of health and disease (DOHaD) hypothesis contribute to improving health in developing countries? The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2011; 94(Suppl):S1759-64. [DOI:10.3945/ajcn.110.000562] [PMID]

- Gruszfeld D, Socha P. Early nutrition and health: Short- and long-term outcomes. World Review of Nutrition and Dietetics. 2013; 108:32-9. [DOI:10.1159/000351482] [PMID]

- Silverman AH. Interdisciplinary care for feeding problems in children. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2010; 25(2):160-5. [DOI:10.1177/0884533610361609] [PMID]

- Rommel N, De Meyer AM, Feenstra L, Veereman-Wauters G. The complexity of feeding problems in 700 infants and young children presenting to a tertiary care institution. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2003; 37(1):75-84. [DOI:10.1097/00005176-200307000-00014] [PMID]

- Greer AJ, Gulotta CS, Masler EA, Laud RB. Caregiver stress and outcomes of children with pediatric feeding disorders treated in an intensive interdisciplinary program. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2008; 33(6):612-20. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsm116] [PMID]

- Singer LT, Song LY, Hill BP, Jaffe AC. Stress and depression in mothers of failure-to-thrive children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1990; 15(6):711-20. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/15.6.711] [PMID]

- Batchelor J. Failure to thrive’ revisited. Child Abuse Review. 2008; 17(3):147-59. [DOI:10.1002/car.1018]

- Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health. 2006; 29(5):489-97. [DOI:10.1002/nur.20147] [PMID]

- Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, Eremenco S, McElroy S, Verjee-Lorenz A, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value in Health. 2005; 8(2):94-104. [DOI:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x] [PMID]

- Ek A, Sorjonen K, Eli K, Lindberg L, Nyman J, Marcus C, et al. Associations between parental concerns about preschoolers’ weight and eating and parental feeding practices: Results from analyses of the child eating behavior questionnaire, the child feeding questionnaire, and the lifestyle behavior checklist. Plos One. 2016; 11(1):e0147257. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0147257] [PMID]

- Kuhn DE, Matson JL. A validity study of the screening tool of feeding problems (STEP). Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability. 2002; 27(3):161-7. [DOI:10.1080/1366825021000008594]

- Pados BF, Thoyre SM, Park J. Age-based norm-reference values for the pediatric eating assessment tool. Pediatric Research. 2018; 84(2):233-9. [DOI:10.1038/s41390-018-0067-z] [PMID]

- Sharifi F, Qoreishi ZS, Bakhtiyari J, Ebadi A, Houshyari M, Azghandi S. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Persian version of the M.D. Anderson dysphagia inventory. International Archives of Otorhinolaryngology. 2024; 28(2):e288-93. [DOI:10.1055/s-0043-1776725] [PMID]

- Silverman AH, Berlin KS, Linn C, Pederson J, Schiedermayer B, Barkmeier-Kraemer J. Psychometric properties of the infant and child feeding questionnaire. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2020; 223:81-6.e2. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.04.040] [PMID]

- Mehboodi R, Javanbakht M, Ramezani M, Ebrahimi AA, Bakhshi E. Normalization and validation of the Persian version of the Scale of Auditory Behaviors. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2025; 26(1):134-49. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.26.1.3923.1]

- Kaviani-Broujeni R, Rezaee M, Pashazadeh Z, Tabatabaei SM, Gerivani H. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of the measure of processes of care-20 item (MPOC-20). Archives of Rehabilitation. 2021; 22(1):102-17. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.22.1.3213.1]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Process of translation and adaptation of instruments [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2025. [Link]

- Waltz CF, Bausell BR. Nursing research: Design, statistics and computer analysis. Philadelphia: F.A. Davis; 1981. [Link]

- Soleimani F, Nobakht Z, Azari N, Kraskian A, Hassanati F, Ghorbanpor Z. [Validity and reliability determination of the Persian version of the adaptive behavior assessment system (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2024; 25(Special Issue):3413. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.25.specialissue.3413.2]

- National Academy of Medicine. Valid and reliable survey instruments to measure burnout, well-being, and other work-related dimensions. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2017. [Link]

- Polit DF, Beck CT, Owen SV. Is the CVI an acceptable indicator of content validity? Appraisal and recommendations. Research in Nursing & Health. 2007; 30(4):459-67. [DOI:10.1002/nur.20199] [PMID]

- Nasirzadeh R. Validity and reliability of children’s eating Behavior Questionnaire. Sadra Medical Science Journal. 2017; 5(2):77-86. [Link]

- Dasht Bozorgi Z, Askary P. [Validity and reliability of the children’s eating behavior questionnaire in Ahvaz city (Persian)]. Journal of Psychology New Ideas. 2017; 1(2):27-34. [Link]

- Mehdizadeh A, Vatanparast H, Khadem-Rezaiyan M, Norouzy A, Abasalti Z, Rajabzadeh M, et al. Validity and reliability of the Persian version of Nutrition Screening Tool for Every Preschooler (NutriSTEP) in Iranian preschool children. Journal of Pediatric Nursing. 2020; 52:e90-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.pedn.2020.01.011] [PMID]

- Camcı N, Bas M, Buyukkaragoz AH. The psychometric properties of the Child Feeding Questionnaire (CFQ) in Turkey. Appetite. 2014; 78:49-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.appet.2014.03.009] [PMID]

- De Bruin G. Problems with the factor analysis of items: Solutions based on item response theory and item parcelling. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology. 2004; 30(4):16-26. [Link]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Speech & Language Pathology

Received: 14/07/2025 | Accepted: 15/11/2025 | Published: 1/01/2026

Received: 14/07/2025 | Accepted: 15/11/2025 | Published: 1/01/2026

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |