Volume 26, Issue 1 (Spring 2025)

jrehab 2025, 26(1): 150-165 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

V M, Catherine S P, Rajasekar M. Comparison of Deictic Gestures in Tamil-Speaking Toddlers at Risk for Autism Spectrum Disorder and Typically Developing Peers. jrehab 2025; 26 (1) :150-165

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3517-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3517-en.html

1- Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research (BIHER), Chennai, India. , monishslp@gmail.com

2- Department of Speech, Hearing and Communication, National Institute for Empowerment of Persons with Multiple Disabilities (Divyangjan), Chennai, India.

3- Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, India.

2- Department of Speech, Hearing and Communication, National Institute for Empowerment of Persons with Multiple Disabilities (Divyangjan), Chennai, India.

3- Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, India.

Full-Text [PDF 1766 kb]

(516 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3044 Views)

Full-Text: (550 Views)

Introduction

Gestures represent actions that are produced to communicate intentionally and involve movements in body parts such as fingers, hands, arms, and head. Deictic gestures are produced to denote a referent that is present in the immediate environment such as objects, people, or locations [1]. Deictic gestures include reaching, pointing, showing, and giving [2]. A study of the hierarchical development of deictic gestures in typically developing (TD) children aged 6-24 months showed that reaching gestures emerge at the age of 6-7 months when infants reach to be picked up. At the age of 7-11 months, infants develop more advanced reaching gestures, such as reaching with their hands or repeatedly opening and shutting their hands. The development of giving, showing, and pointing gestures normally at the age of 9-11 months [3].

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by challenges in social communication, along with restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. One of the diagnostic criteria for ASD is impairment in gesture use [4]. For children at an early age with ASD, deictic gestures are especially challenging [5, 6]. Difficulty in producing deictic gestures is more prevalent in toddlers diagnosed with ASD compared to TD toddlers [7]. The use of deictic gestures by children with ASD was found to be an effective predictor of their speaking vocabulary development 12 months later, despite the reduced rate [6, 8]. Several studies have reported the reduced usage of communicative gestures in children with ASD. For instance, Töret and Acarlar [9] compared gesture use in three groups of Turkish children with ASD, children with Down syndrome (DS), and TD children. Children with ASD used deictic gestures less compared to the other two groups. They used the pointing gesture to request an object less. Mastrogiuseppe et al. [10] compared gestural communication in Italian children with ASD, DS, and TD children during interaction with their mothers for 10 minutes. The chronological age of the ASD group ranged from 30 to 66 months. They found that children with ASD produced significantly fewer gestures than TD children and children with DS. Choi et al. [11] studied gesture production in infants at low and high risk for ASD in the U.S at 12, 18, and 24 months of age while interacting with a caregiver through playing and found that those who were later identified as ASD exhibited fewer gestures and lower gesture-speech combinations, and subsequent receptive language was predicted by gesture production. Mishra et al. [12] investigated gesture production in toddlers with ASD and TD children in the U.S. when interacting with their caregivers during play for 10 minutes. Compared to TD children, ASD children produced fewer deictic gestures in total and in their subtypes, such as pointing, showing, and giving. Monish et al. [13] investigated the deictic gestures in Tamil-speaking children with ASD (chronological age: 2.6–8 years), DS (2.8–8 years), and TD. All three groups were matched for chronological age. They found that, in comparison with the other two groups, the children with ASD used fewer deictic gestures and their subtypes, including pointing, giving, and showing. There is a lack of comprehensive studies on deictic gestures in Indian toddlers at risk of ASD, particularly those from Tamil-speaking families. Therefore, the current aimed to compare the production of deictic gestures (overall and in its subtypes) in Tamil-speaking toddlers at risk for ASD and two groups of TD children matched for developmental age (DA) and language age (LA) during parent-child dyadic interaction.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional study. Participants were 45 Tamil-speaking toddlers at risk for ASD and TD children (30 boys and 15 girls) and their parents. They were put in three groups of ASD (n=15), TD-DA (n=15, matched for age at mental development and gender), and TD-LA (n=15, matched for age at language development and gender). Ninety percent of the parents were mothers. All parent-child dyads were Indian and their native as well as primary language of communication was Tamil. All parents belonged to the middle socioeconomic class according to the revised Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic status scale [14]. Also, 20% of them had senior secondary school education, 60% were graduates, and 20% had post-graduate education.

Children in the ASD group were diagnosed using the modified checklist for autism in toddlers (M-CHAT) [15] and clinical judgment based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria [1]. Developmental age was determined using the developmental screening test (DST) [16] which was in the range of 12-36 months. Clinical psychologists conducted the M-CHAT and DST assessments as part of their routine evaluations for toddlers. The assessment of language development (ALD) tool [17] was used to evaluate the age at language development of ASD children which was in the range of 6-18 months. To select toddlers at risk for ASD, a purposive sampling technique was employed. The children and their parents were recruited from an early intervention and rehabilitation center in South India. Inclusion criteria for the ASD group included age 12-36 months, attending at least five sessions of speech-language therapy, and no any particular parental concerns related to motor, hearing, vision and cognitive skills. Exclusion criteria were seizures or any other syndromic condition, and any comorbid conditions.

For the TD-DA and TD-LA groups, the inclusion criteria were no communication, motor, or cognitive/neurological deficits according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 10-item disability screening checklist [18], and having adequate language skills based on the ALD score. Children with seizures and any reports of systemic diseases which require frequent medical attention were excluded.

Instruments

The M-CHAT has 20 yes/no items answered by parents. The risk for ASD was indicated by answering “no” to all items except for items 2,5 and 12 and by answering “yes” to items 2, 5, and 12. The DST is a rapid and reliable intelligence assessment for children aged 1-15 years, designed to evaluate developmental milestones without performance-based tasks. It includes 88 items distributed across various age categories, covering motor, speech, and social development to give an overview of the developmental progress of the children. The ALD tool is a performance-based, norm-referenced, and standardized test designed to assess the language skills (receptive and expressive) of Indian children from birth to ten years. The WHO 10-item disability screening checklist is a clinical screening tool that was administered to the parents. It has 10 items used to screen children for developmental disabilities.

Examination of deictic gestures

We examined deictic gestures during 10 minutes of naturally occurring play between parents and children. Throughout the interaction, all children used a standard set of toys, including two dolls (girl and boy), a tea set, a ball, a comb, a brush, a bike, a car, a telephone, and two books. The toy set included materials that every child was likely to know from their daily lives and were appropriate for a variety of activities that were suitable for their age. The parents were instructed to play with their children by using the toys provided, similar to how they usually play with their children at home. The main researcher at the clinic used a mobile phone camera with a resolution of 20 megapixels to record the parent-child interactions. The deictic gesture subtypes used by the children were coded using the Eudico Linguistic Annotator (ELAN) [19], which is a computer-based annotation tool for audio and video recordings. By encouraging the use of standardized terminology by offering controlled vocabulary as well as template facilities, ELAN brings a strong technological foundation [20]. Using this software, the main researcher transcribed and coded the deictic gestures and subtypes. Frequency of each deictic gesture and subtype was recorded for all children in three groups. The coding method for deictic gestures was based on literature [2, 7, 11]. The deictic gestures included reaching, pointing, giving, and showing.

Reaching refers to extending the arm with an open palm or repeatedly opening and closing the hand towards another person, object, or location.” In this study, we subdivided the reaching gesture into two types: Reaching towards the toy held by parents (RTP) and reaching towards the toy not held by parents (RTN). Pointing refers to extension and flexion of index finger. There were two subtypes of pointing: Distal pointing (DP) which refers to pointing to the toy/person that do not involve touching, and proximal pointing (PP) which refers to pointing to the toy/person by touching it with finger. Giving is defined as the act of offering a toy to another person. In this study, we subdivided the giving gesture into giving the toy spontaneously to the parent (GS) and giving the toy upon request to the parent (GR). Showing is defined as holding or extending a toy towards another person.

The coding reliability was achieved by employing a second trained speech-language pathologist for 20% of samples in each group. The percent agreement between the coders was 77% for identifying overall deictic gestures and classifying deictic gestures into four types. For identifying the pointing gesture, the intercoder agreement was 88%. The obtained Cohen’s kappa coefficient was κ=0.85 for overall deictic gestures, κ=0.73 for reaching; κ=0.85 for pointing, κ=0.73 for giving, and κ=0.65 for showing.

Statistical analysis

We considered the risk for ASD, TD-DA, and TD-LA as independent variables, while deictic gestures (reaching, pointing, giving, showing) and its subtype were considered as dependent variables. The normality of data distribution was first examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test, whose results necessitated the use of non-parametric tests. Therefore, to analyze the differences between the groups, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed.

Results

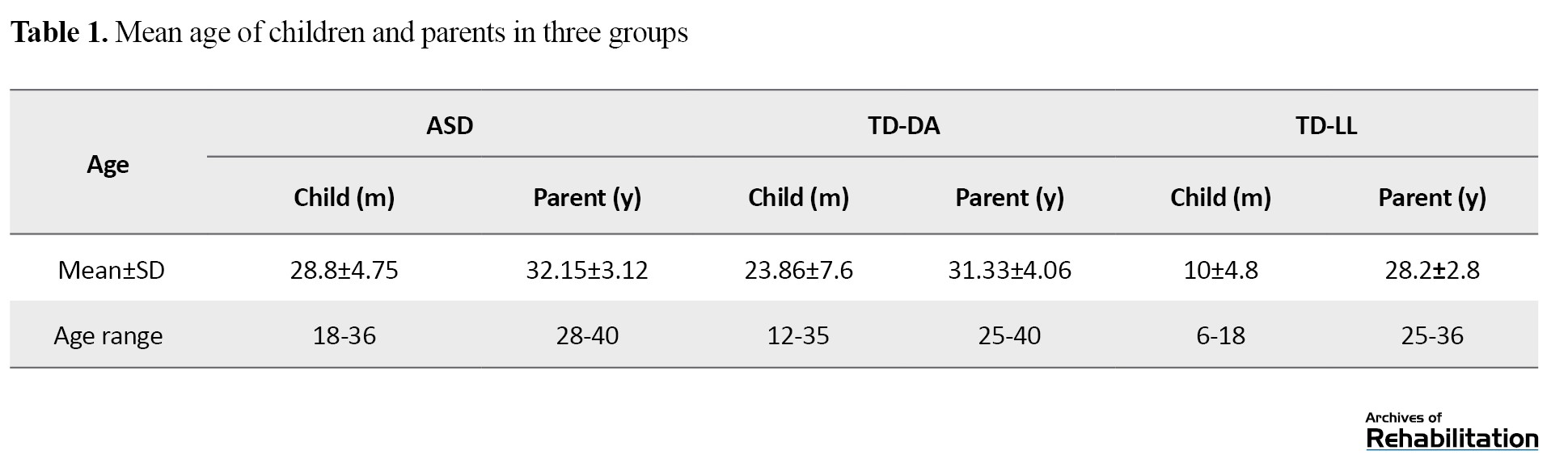

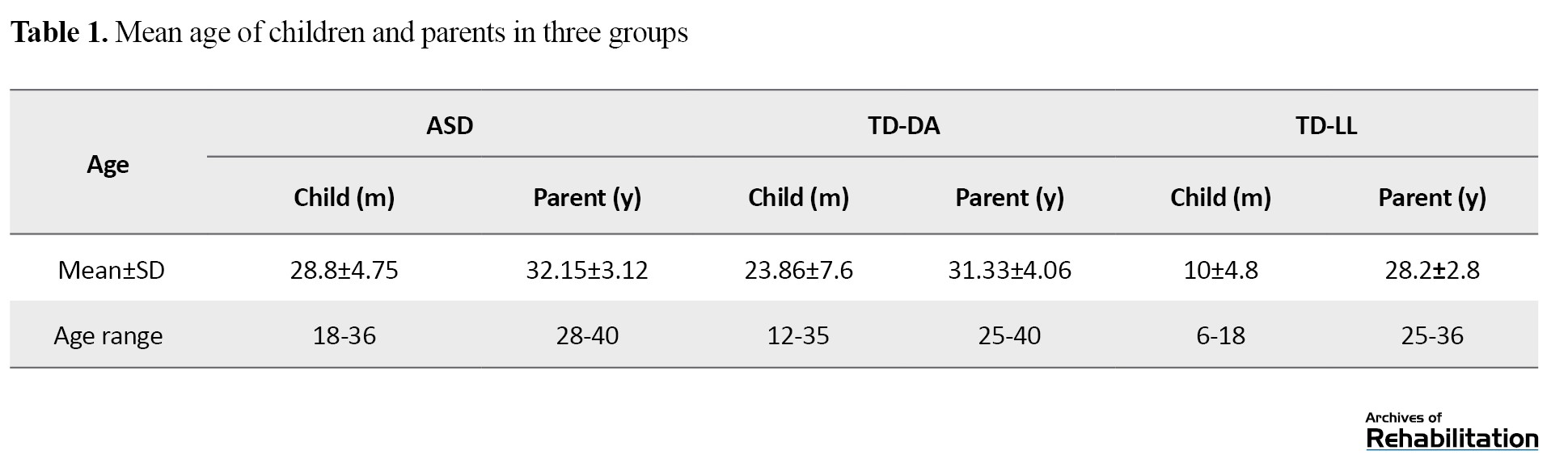

Table 1 shows the age of children and parents in three groups.

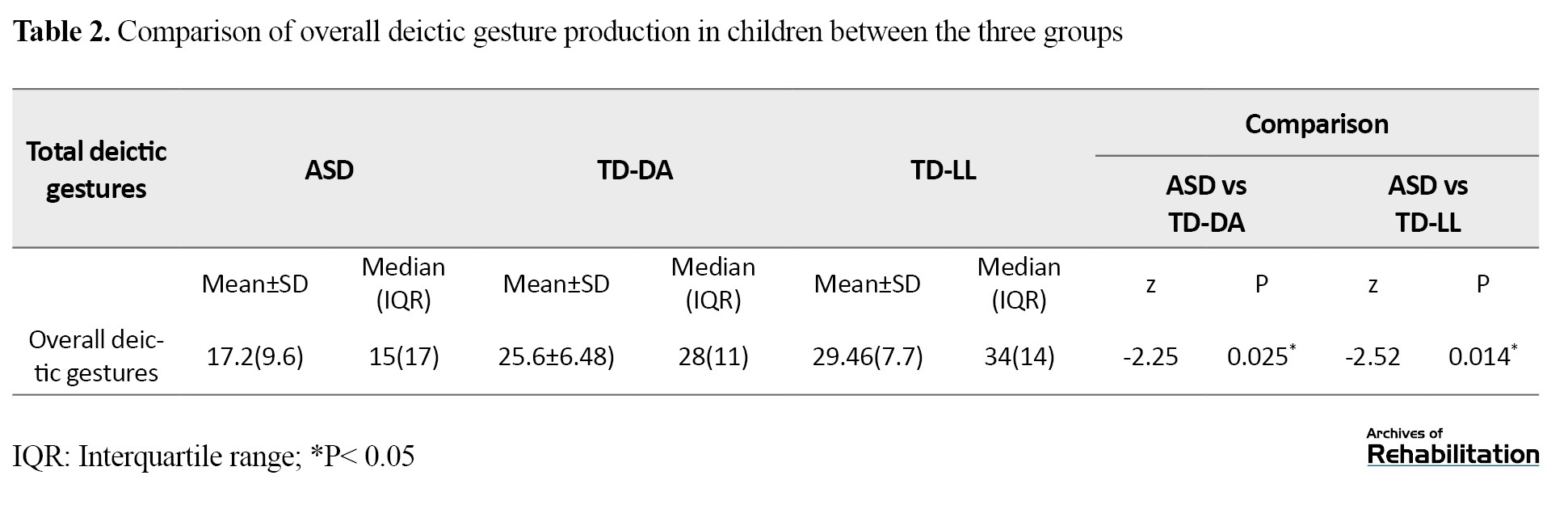

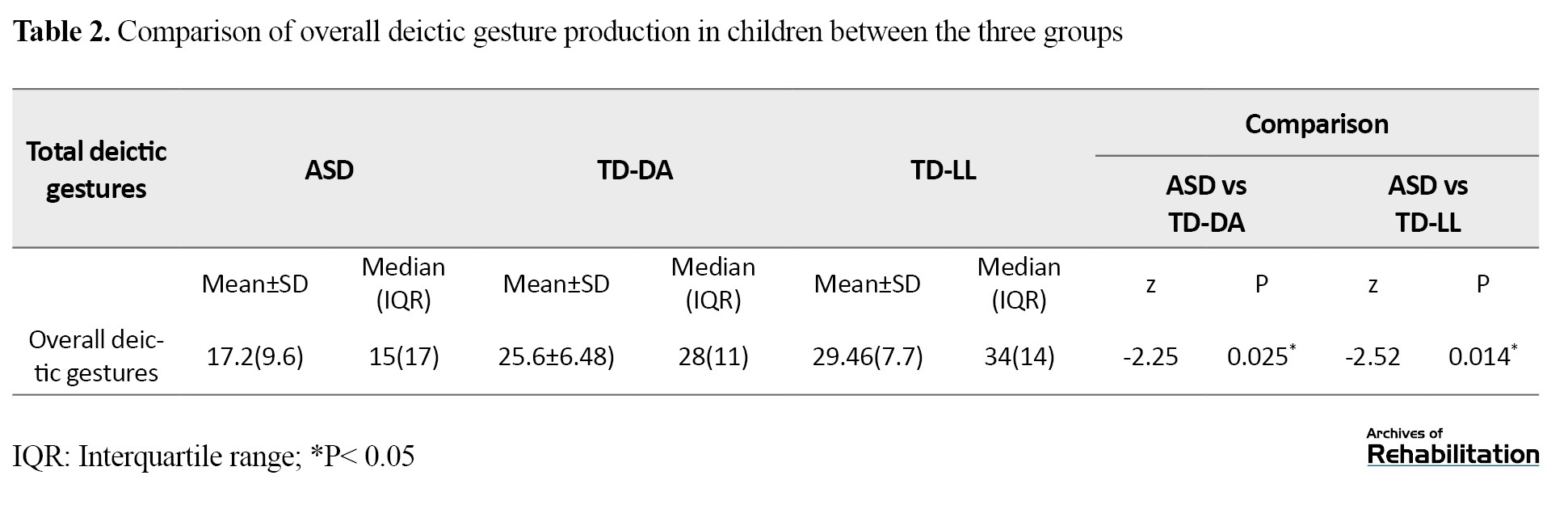

Table 2 represents the frequency of overall deictic gestures produced by children in three groups.

During parent-child interaction, there was a significant difference in the overall deictic gesture production between the three groups (P<0.05). The overall deictic gesture production was lower in the children at risk for ASD compared to other two groups.

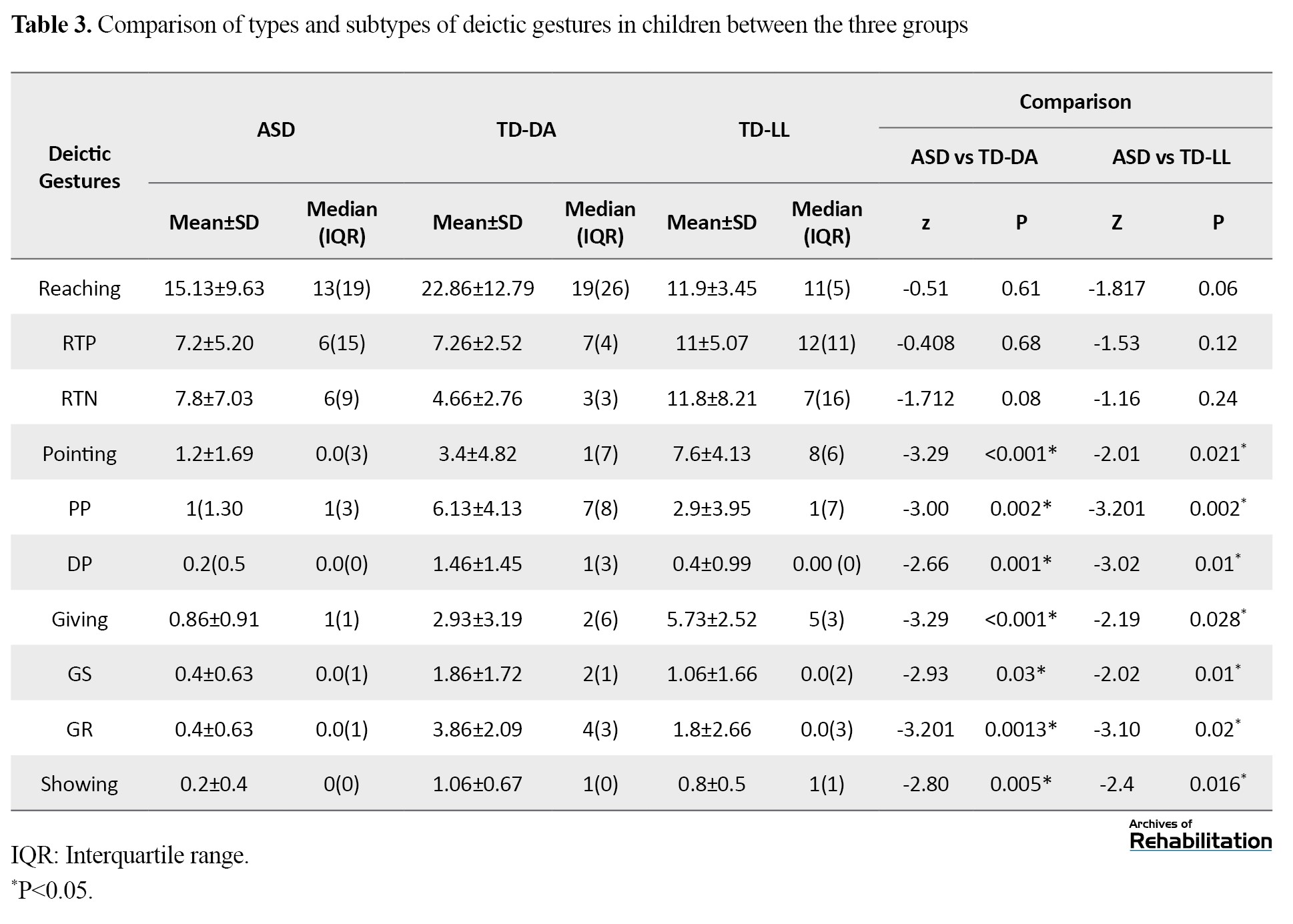

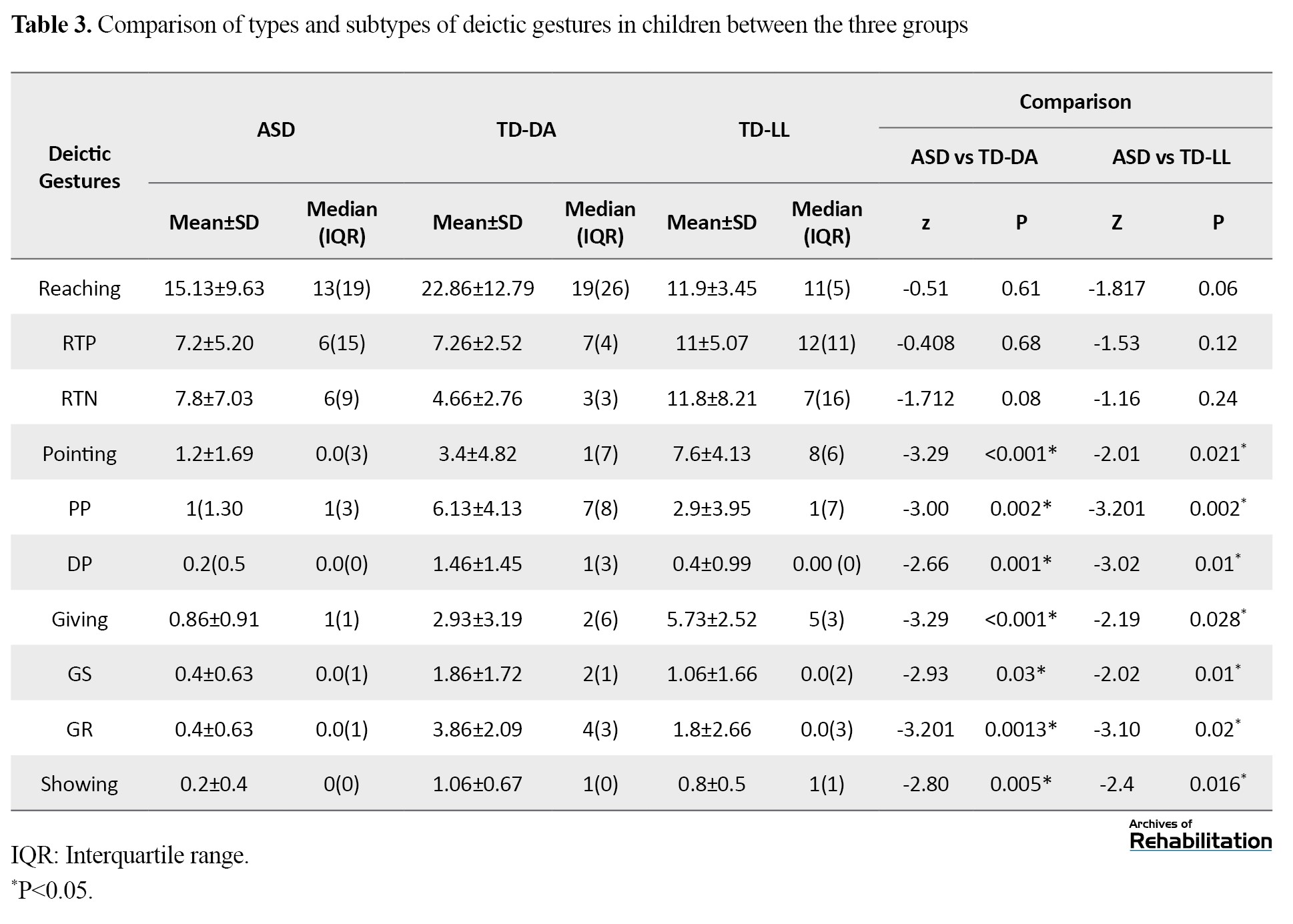

Table 3 represent the different types of deictic gestures produced by children at risk for ASD, TD-DA and TD-LA groups.

In children at risk for ASD, the mean frequency of reaching gesture was higher (15.13±9.63) followed by pointing gesture (1.2±1.69), giving gesture (0.86±0.91) and showing gesture (0.2±0.4). There was a significant difference in the subtypes of pointing gesture produced by children at risk for ASD compared to other groups, where DP (0.2±0.5) was produced fewer than PP (1±1.30). For reaching and its subtypes (RTP and RTN), there was no significant difference between the three groups. For giving gesture and its subtypes (GR and GS) and showing gesture, there was a significant difference between the three groups. Therefore, children at risk for ASD produced fewer deictic gestures than the other two groups of TD children in all types except for reaching gesture.

Discussion

This prospective study aimed to investigate and compare the use of deictic gestures by Tamil-speaking toddlers at risk for ASD and two groups of TD children matched for age at mental development and age at language development during parent-child interaction.

Based on the results, the children at risk for ASD produced fewer deictic gestures than the two groups of TD children which is in line with the results of previous studies [7, 10-12]. Deictic gestures are important for prelinguistic communication in infants since they emerge before expressive language development, allow infants to communicate in different ways, and are closely related to subsequent emerging first words and early syntax. There is a close association between deictic gestures and the emergence of first words [21]. In toddlers at risk for ASD, the fewer use of deictic gestures can influence the development of intentional communication. Since deictic gestures and the development of language are tightly connected, the emergence of first words in toddlers at risk for ASD may be affected by the reduced use of these gestures.

The findings in our study showed no significant difference in the use of reaching gesture and its subtypes (RTP and RTN) among the three groups. This finding is in line with the results of a previous study [10]. Reaching is considered a primitive gesture, and its use drops when other gestures and language develop [22]. In this study, toddlers at risk for ASD had communication deficits, inadequate language level, and reduced production of other deictic gestures (giving, showing, and pointing); therefore, reaching gesture produced more. Fewer use of pointing gesture by toddlers at risk for ASD than the TD children is in agreement with the results of previous studies [7, 10-12]. Pointing gesture is considered as a first step towards true symbolization [23]. ASD is characterized by difficulty in the use of gaze and pointing for nonverbal communication, as well as atypical language development [24]. In our study, children at risk for ASD showed different subtypes of pointing gestures; where DP was produced fewer than PP. A possible reason for this difference is that DP emerges later than PP in a typical development [25]. Also, DP involves a more cognitively advanced mechanism compared to PP [26].

In our study, toddlers at risk for ASD used fewer giving gesture than the TD children. Moreover, they produced fewer subtypes of giving gesture such as giving the toy spontaneously to parents and giving the toy upon request to parent, highlighting their deficits in joint attention/social interaction and comprehending the rules of communication during interaction, whereas the TD children could establish joint attention with their parents during the interaction. Furthermore, the toddlers at risk for ASD had a reduced use of showing gesture which is consistent with the results of previous studies [11, 12]. The production of showing gesture may distinguish infants at high risk of developing ASD from others who may develop language delays or mild difficulties in social skills [27]. In children with ASD, the showing gesture may be a more accurate indicator of ASD than the pointing gesture. Showing gesture, contrary to pointing gesture, is meant to start a shared social experience rather than expressing a need [27]. In our study, we observed that children at risk for ASD used deictic gestures predominantly for the purpose of requesting (proto-imperative) rather than sharing interests (proto-declarative). Among the deictic gestures, showing gesture was the least commonly used gesture by the children at risk for ASD.

Few studies have shown the importance of the referential communication gestures, including pointing, giving and showing, related to vocabulary learning, which may be as a possible predictor of subsequent language competence [28, 29]. Therefore, inadequate language skills in toddlers at risk for ASD can also be a reason for the reduced use of pointing, giving and showing gestures compared to TD children.

Conclusion

The Tamil-speaking toddlers at risk for ASD have inadequate production of deictic gestures in naturalistic contexts compared to TD children. The results emphasized the importance of investigating the deictic gestures used by toddlers at risk for ASD, as well as their other communication abilities, in their assessment and intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee of the Sree Balaji Medical College & Hospital (Code: 002-SBMCH-IHEC-2023-1944). Before the study, the parents gave their informed consent.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: MK Rajasekar and Monish V; Methodology: S. Powlin Arockia Catherine and Monish V; Data collection and Data analysis: Monish V; Investigation, writing and resources: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all the participants for their valuable time and support in this study.

References

Gestures represent actions that are produced to communicate intentionally and involve movements in body parts such as fingers, hands, arms, and head. Deictic gestures are produced to denote a referent that is present in the immediate environment such as objects, people, or locations [1]. Deictic gestures include reaching, pointing, showing, and giving [2]. A study of the hierarchical development of deictic gestures in typically developing (TD) children aged 6-24 months showed that reaching gestures emerge at the age of 6-7 months when infants reach to be picked up. At the age of 7-11 months, infants develop more advanced reaching gestures, such as reaching with their hands or repeatedly opening and shutting their hands. The development of giving, showing, and pointing gestures normally at the age of 9-11 months [3].

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by challenges in social communication, along with restricted interests and repetitive behaviors. One of the diagnostic criteria for ASD is impairment in gesture use [4]. For children at an early age with ASD, deictic gestures are especially challenging [5, 6]. Difficulty in producing deictic gestures is more prevalent in toddlers diagnosed with ASD compared to TD toddlers [7]. The use of deictic gestures by children with ASD was found to be an effective predictor of their speaking vocabulary development 12 months later, despite the reduced rate [6, 8]. Several studies have reported the reduced usage of communicative gestures in children with ASD. For instance, Töret and Acarlar [9] compared gesture use in three groups of Turkish children with ASD, children with Down syndrome (DS), and TD children. Children with ASD used deictic gestures less compared to the other two groups. They used the pointing gesture to request an object less. Mastrogiuseppe et al. [10] compared gestural communication in Italian children with ASD, DS, and TD children during interaction with their mothers for 10 minutes. The chronological age of the ASD group ranged from 30 to 66 months. They found that children with ASD produced significantly fewer gestures than TD children and children with DS. Choi et al. [11] studied gesture production in infants at low and high risk for ASD in the U.S at 12, 18, and 24 months of age while interacting with a caregiver through playing and found that those who were later identified as ASD exhibited fewer gestures and lower gesture-speech combinations, and subsequent receptive language was predicted by gesture production. Mishra et al. [12] investigated gesture production in toddlers with ASD and TD children in the U.S. when interacting with their caregivers during play for 10 minutes. Compared to TD children, ASD children produced fewer deictic gestures in total and in their subtypes, such as pointing, showing, and giving. Monish et al. [13] investigated the deictic gestures in Tamil-speaking children with ASD (chronological age: 2.6–8 years), DS (2.8–8 years), and TD. All three groups were matched for chronological age. They found that, in comparison with the other two groups, the children with ASD used fewer deictic gestures and their subtypes, including pointing, giving, and showing. There is a lack of comprehensive studies on deictic gestures in Indian toddlers at risk of ASD, particularly those from Tamil-speaking families. Therefore, the current aimed to compare the production of deictic gestures (overall and in its subtypes) in Tamil-speaking toddlers at risk for ASD and two groups of TD children matched for developmental age (DA) and language age (LA) during parent-child dyadic interaction.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional study. Participants were 45 Tamil-speaking toddlers at risk for ASD and TD children (30 boys and 15 girls) and their parents. They were put in three groups of ASD (n=15), TD-DA (n=15, matched for age at mental development and gender), and TD-LA (n=15, matched for age at language development and gender). Ninety percent of the parents were mothers. All parent-child dyads were Indian and their native as well as primary language of communication was Tamil. All parents belonged to the middle socioeconomic class according to the revised Kuppuswamy’s socioeconomic status scale [14]. Also, 20% of them had senior secondary school education, 60% were graduates, and 20% had post-graduate education.

Children in the ASD group were diagnosed using the modified checklist for autism in toddlers (M-CHAT) [15] and clinical judgment based on the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria [1]. Developmental age was determined using the developmental screening test (DST) [16] which was in the range of 12-36 months. Clinical psychologists conducted the M-CHAT and DST assessments as part of their routine evaluations for toddlers. The assessment of language development (ALD) tool [17] was used to evaluate the age at language development of ASD children which was in the range of 6-18 months. To select toddlers at risk for ASD, a purposive sampling technique was employed. The children and their parents were recruited from an early intervention and rehabilitation center in South India. Inclusion criteria for the ASD group included age 12-36 months, attending at least five sessions of speech-language therapy, and no any particular parental concerns related to motor, hearing, vision and cognitive skills. Exclusion criteria were seizures or any other syndromic condition, and any comorbid conditions.

For the TD-DA and TD-LA groups, the inclusion criteria were no communication, motor, or cognitive/neurological deficits according to the World Health Organization (WHO) 10-item disability screening checklist [18], and having adequate language skills based on the ALD score. Children with seizures and any reports of systemic diseases which require frequent medical attention were excluded.

Instruments

The M-CHAT has 20 yes/no items answered by parents. The risk for ASD was indicated by answering “no” to all items except for items 2,5 and 12 and by answering “yes” to items 2, 5, and 12. The DST is a rapid and reliable intelligence assessment for children aged 1-15 years, designed to evaluate developmental milestones without performance-based tasks. It includes 88 items distributed across various age categories, covering motor, speech, and social development to give an overview of the developmental progress of the children. The ALD tool is a performance-based, norm-referenced, and standardized test designed to assess the language skills (receptive and expressive) of Indian children from birth to ten years. The WHO 10-item disability screening checklist is a clinical screening tool that was administered to the parents. It has 10 items used to screen children for developmental disabilities.

Examination of deictic gestures

We examined deictic gestures during 10 minutes of naturally occurring play between parents and children. Throughout the interaction, all children used a standard set of toys, including two dolls (girl and boy), a tea set, a ball, a comb, a brush, a bike, a car, a telephone, and two books. The toy set included materials that every child was likely to know from their daily lives and were appropriate for a variety of activities that were suitable for their age. The parents were instructed to play with their children by using the toys provided, similar to how they usually play with their children at home. The main researcher at the clinic used a mobile phone camera with a resolution of 20 megapixels to record the parent-child interactions. The deictic gesture subtypes used by the children were coded using the Eudico Linguistic Annotator (ELAN) [19], which is a computer-based annotation tool for audio and video recordings. By encouraging the use of standardized terminology by offering controlled vocabulary as well as template facilities, ELAN brings a strong technological foundation [20]. Using this software, the main researcher transcribed and coded the deictic gestures and subtypes. Frequency of each deictic gesture and subtype was recorded for all children in three groups. The coding method for deictic gestures was based on literature [2, 7, 11]. The deictic gestures included reaching, pointing, giving, and showing.

Reaching refers to extending the arm with an open palm or repeatedly opening and closing the hand towards another person, object, or location.” In this study, we subdivided the reaching gesture into two types: Reaching towards the toy held by parents (RTP) and reaching towards the toy not held by parents (RTN). Pointing refers to extension and flexion of index finger. There were two subtypes of pointing: Distal pointing (DP) which refers to pointing to the toy/person that do not involve touching, and proximal pointing (PP) which refers to pointing to the toy/person by touching it with finger. Giving is defined as the act of offering a toy to another person. In this study, we subdivided the giving gesture into giving the toy spontaneously to the parent (GS) and giving the toy upon request to the parent (GR). Showing is defined as holding or extending a toy towards another person.

The coding reliability was achieved by employing a second trained speech-language pathologist for 20% of samples in each group. The percent agreement between the coders was 77% for identifying overall deictic gestures and classifying deictic gestures into four types. For identifying the pointing gesture, the intercoder agreement was 88%. The obtained Cohen’s kappa coefficient was κ=0.85 for overall deictic gestures, κ=0.73 for reaching; κ=0.85 for pointing, κ=0.73 for giving, and κ=0.65 for showing.

Statistical analysis

We considered the risk for ASD, TD-DA, and TD-LA as independent variables, while deictic gestures (reaching, pointing, giving, showing) and its subtype were considered as dependent variables. The normality of data distribution was first examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test, whose results necessitated the use of non-parametric tests. Therefore, to analyze the differences between the groups, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was employed.

Results

Table 1 shows the age of children and parents in three groups.

Table 2 represents the frequency of overall deictic gestures produced by children in three groups.

During parent-child interaction, there was a significant difference in the overall deictic gesture production between the three groups (P<0.05). The overall deictic gesture production was lower in the children at risk for ASD compared to other two groups.

Table 3 represent the different types of deictic gestures produced by children at risk for ASD, TD-DA and TD-LA groups.

In children at risk for ASD, the mean frequency of reaching gesture was higher (15.13±9.63) followed by pointing gesture (1.2±1.69), giving gesture (0.86±0.91) and showing gesture (0.2±0.4). There was a significant difference in the subtypes of pointing gesture produced by children at risk for ASD compared to other groups, where DP (0.2±0.5) was produced fewer than PP (1±1.30). For reaching and its subtypes (RTP and RTN), there was no significant difference between the three groups. For giving gesture and its subtypes (GR and GS) and showing gesture, there was a significant difference between the three groups. Therefore, children at risk for ASD produced fewer deictic gestures than the other two groups of TD children in all types except for reaching gesture.

Discussion

This prospective study aimed to investigate and compare the use of deictic gestures by Tamil-speaking toddlers at risk for ASD and two groups of TD children matched for age at mental development and age at language development during parent-child interaction.

Based on the results, the children at risk for ASD produced fewer deictic gestures than the two groups of TD children which is in line with the results of previous studies [7, 10-12]. Deictic gestures are important for prelinguistic communication in infants since they emerge before expressive language development, allow infants to communicate in different ways, and are closely related to subsequent emerging first words and early syntax. There is a close association between deictic gestures and the emergence of first words [21]. In toddlers at risk for ASD, the fewer use of deictic gestures can influence the development of intentional communication. Since deictic gestures and the development of language are tightly connected, the emergence of first words in toddlers at risk for ASD may be affected by the reduced use of these gestures.

The findings in our study showed no significant difference in the use of reaching gesture and its subtypes (RTP and RTN) among the three groups. This finding is in line with the results of a previous study [10]. Reaching is considered a primitive gesture, and its use drops when other gestures and language develop [22]. In this study, toddlers at risk for ASD had communication deficits, inadequate language level, and reduced production of other deictic gestures (giving, showing, and pointing); therefore, reaching gesture produced more. Fewer use of pointing gesture by toddlers at risk for ASD than the TD children is in agreement with the results of previous studies [7, 10-12]. Pointing gesture is considered as a first step towards true symbolization [23]. ASD is characterized by difficulty in the use of gaze and pointing for nonverbal communication, as well as atypical language development [24]. In our study, children at risk for ASD showed different subtypes of pointing gestures; where DP was produced fewer than PP. A possible reason for this difference is that DP emerges later than PP in a typical development [25]. Also, DP involves a more cognitively advanced mechanism compared to PP [26].

In our study, toddlers at risk for ASD used fewer giving gesture than the TD children. Moreover, they produced fewer subtypes of giving gesture such as giving the toy spontaneously to parents and giving the toy upon request to parent, highlighting their deficits in joint attention/social interaction and comprehending the rules of communication during interaction, whereas the TD children could establish joint attention with their parents during the interaction. Furthermore, the toddlers at risk for ASD had a reduced use of showing gesture which is consistent with the results of previous studies [11, 12]. The production of showing gesture may distinguish infants at high risk of developing ASD from others who may develop language delays or mild difficulties in social skills [27]. In children with ASD, the showing gesture may be a more accurate indicator of ASD than the pointing gesture. Showing gesture, contrary to pointing gesture, is meant to start a shared social experience rather than expressing a need [27]. In our study, we observed that children at risk for ASD used deictic gestures predominantly for the purpose of requesting (proto-imperative) rather than sharing interests (proto-declarative). Among the deictic gestures, showing gesture was the least commonly used gesture by the children at risk for ASD.

Few studies have shown the importance of the referential communication gestures, including pointing, giving and showing, related to vocabulary learning, which may be as a possible predictor of subsequent language competence [28, 29]. Therefore, inadequate language skills in toddlers at risk for ASD can also be a reason for the reduced use of pointing, giving and showing gestures compared to TD children.

Conclusion

The Tamil-speaking toddlers at risk for ASD have inadequate production of deictic gestures in naturalistic contexts compared to TD children. The results emphasized the importance of investigating the deictic gestures used by toddlers at risk for ASD, as well as their other communication abilities, in their assessment and intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Institutional Human Ethics Committee of the Sree Balaji Medical College & Hospital (Code: 002-SBMCH-IHEC-2023-1944). Before the study, the parents gave their informed consent.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: MK Rajasekar and Monish V; Methodology: S. Powlin Arockia Catherine and Monish V; Data collection and Data analysis: Monish V; Investigation, writing and resources: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors sincerely thank all the participants for their valuable time and support in this study.

References

- Bates E, Camaioni L, Volterra V. The acquisition of performatives prior to speech. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly of Behavior and Development. 1975; 21(3):205-26. [Link]

- Iverson JM, Thal D, Wetherby A, Warren S, Reichle J. Communicative transitions: There’s more to the hand than meets the eye. Transitions in Prelinguistic Communication. 1998; 7:59-86. [Link]

- Crais E, Douglas DD, Campbell CC. The intersection of the development of gestures and intentionality. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004; 47(3):678-94.[DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2004/052)] [PMID]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Virginia: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Link]

- Shumway S, Wetherby AM. Communicative acts of children with autism spectrum disorders in the second year of life. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2009; 52(5):1139-56. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2009/07-0280)] [PMID]

- Özçalışkan Ş, Adamson LB, Dimitrova N. Early deictic but not other gestures predict later vocabulary in both typical development and autism. Autism. 2016; 20(6):754-63. [DOI:10.1177/1362361315605921] [PMID]

- Manwaring SS, Stevens AL, Mowdood A, Lackey M. A scoping review of deictic gesture use in toddlers with or at-risk for autism spectrum disorder. Autism & Developmental Language Impairments. 2018; 3. [DOI:10.1177/2396941517751891]

- Gulsrud AC, Hellemann GS, Freeman SF, Kasari C. Two to ten years: Developmental trajectories of joint attention in children with ASD who received targeted social communication interventions. Autism Research. 2014; 7(2):207-15. [DOI:10.1002/aur.1360] [PMID]

- Toret G, Acarlar F. Gestures in Prelinguistic Turkish children with Autism, Down Syndrome, and Typically Developing Children. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice. 2011; 11(3):1471-8. [Link]

- Mastrogiuseppe M, Capirci O, Cuva S, Venuti P. Gestural communication in children with autism spectrum disorders during mother-child interaction. Autism. 2015; 19(4):469-81. [DOI:10.1177/1362361314528390] [PMID]

- Choi B, Shah P, Rowe ML, Nelson CA, Tager-Flusberg H. Gesture development, caregiver responsiveness, and language and diagnostic outcomes in infants at high and low risk for autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2020; 50(7):2556-72. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-019-03980-8] [PMID]

- Mishra A, Ceballos V, Himmelwright K, McCabe S, Scott L. Gesture production in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2021; 51(5):1658-67. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-020-04647-5] [PMID]

- Monish V, Catherine SP, Rajasekar MK. Deictic Gesture Production in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, Down Syndrome, and Typically Developing Children During Dyadic Interaction. Journal of Indian Association for Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2024; 24(4):344-51. [DOI:10.1177/09731342241261493]

- Sharma R. Revised Kuppuswamy’s Socioeconomic Status Scale: Explained and Updated. Indian Pediatrics. 2017; 54(10):867-70. [PMID]

- Robins DL, Fein D, Barton ML, Green JA. The Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers: an initial study investigating the early detection of autism and pervasive developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2001; 31(2):131-44. [DOI:10.1023/A:1010738829569] [PMID]

- Bharat Raj J. Developmental screening test (DST). Mysore, Karnataka, India: Swayamsiddha; 1983. [Link]

- Lakkanna S, Venkatesh K, Bhat JS. Assessment of language development. Bakersfield, CA: Omni Therapy Services; 2008.

- Singhi P, Kumar M, Malhi P, Kumar R. Utility of the WHO Ten Questions screen for disability detection in a rural community-the north Indian experience. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics. 2007; 53(6):383-7. [DOI:10.1093/tropej/fmm047] [PMID]

- Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. ELAN [computer program]. Version 6.5. Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics; 2023. [Link]

- Lausberg H, Sloetjes H. Coding gestural behavior with the NEUROGES-ELAN system. Behavior Research Methods. 2009; 41(3):841-9. [DOI:10.3758/BRM.41.3.841] [PMID]

- Liszkowski U. Deictic and other gestures in infancy. Acción Psicológica. 2010; 7(2):21-33. [Link]

- Blake J, Dolgoy SJ. Gestural development and its relation to cognition during the transition to language. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior. 1993 ; 17:87-102. [DOI:10.1007/BF01001958]

- Werner H, Kaplan B. Symbol formation: An organismic-developmental Approach to Language Development and the Expression of Thought. New York, NY: Wiley; 1963. [Link]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Link]

- Butterworth G. Pointing is the royal road to language for babies. In: Pointing: Where language, culture, and cognition meet. New York: Psychology Press; 2003. [Link]

- Ramos-Cabo S, Vulchanov V, Vulchanova M. Different ways of making a point: A study of gestural communication in typical and atypical early development. Autism Research. 2021; 14(5):984-96. [DOI:10.1002/aur.2438]

- Clements C, Chawarska K. Beyond pointing: development of the “showing” gesture in children with autism spectrum disorder. Yale Review of Undergraduate Research in Psychology. 2010; 2:1-1. [Link]

- Thal D, Bates E. Language and gesture in late talkers. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1988; 31(1):115-23. [DOI:10.1044/jshr.3101.115] [PMID]

- Thal DJ, Tobias S. Communicative gestures in children with delayed onset of oral expressive vocabulary. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1992; 35(6):1281-9. [DOI:10.1044/jshr.3506.1289] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Speech & Language Pathology

Received: 11/07/2024 | Accepted: 12/11/2024 | Published: 1/04/2025

Received: 11/07/2024 | Accepted: 12/11/2024 | Published: 1/04/2025

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |