Volume 26, Issue 1 (Spring 2025)

jrehab 2025, 26(1): 66-87 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khanjani M S, Ebrahimgol F, Azkhosh M, Hoseinzadeh S, Latifian M, Esmaeili S. Assessing the Psychometric Properties of the Persian Version of the Adaptation to Chronic Illness Scale for Patients With Cardiovascular Diseases. jrehab 2025; 26 (1) :66-87

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3487-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3487-en.html

Mohammad Saeed Khanjani1

, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol1

, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol1

, Manoochehr Azkhosh1

, Manoochehr Azkhosh1

, Samaneh Hoseinzadeh2

, Samaneh Hoseinzadeh2

, Maryam Latifian *3

, Maryam Latifian *3

, Sahar Esmaeili4

, Sahar Esmaeili4

, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol1

, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol1

, Manoochehr Azkhosh1

, Manoochehr Azkhosh1

, Samaneh Hoseinzadeh2

, Samaneh Hoseinzadeh2

, Maryam Latifian *3

, Maryam Latifian *3

, Sahar Esmaeili4

, Sahar Esmaeili4

1- Department of Counseling, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Substance Abuse and Dependence Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,maryamlatifian1993@gmail.com

4- Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada.

2- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Substance Abuse and Dependence Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

4- Faculty of Social Work, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada.

Full-Text [PDF 1868 kb]

(785 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3120 Views)

Full-Text: (930 Views)

Introduction

Achronic disease is a long-lasting condition that leads to physical limitations in the body and restricts the patient’s daily living activities. For these diseases, the treatment takes along time and the recovery is difficult. In some cases, there is no definitive cure [1]. Although these diseases are not directly fatal, they can disrupt the quality of life (QoL) and lead to early and severe disabilities [2]. Chronic diseases account for 60% of all deaths worldwide, and their prevalence can be seen in all regions and socioeconomic classes [3]. Chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the major causes of death and contribute significantly to disability and mortality [4]. The CVDs are a group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels [5]. Heart failure is defined as progressive damage to the heart due to its inability to circulate blood properly throughout the body. This disease is one of the three main causes of death in industrialized countries. Although mortality from CVDs has decreased in recent years in developed countries, evidence suggests that lifestyle changes have led to an increasing prevalence of CVDs in Iran [6], where it is the leading cause of death for individuals over 35 years of age [7].

The CVDs can cause many symptoms such as shortness of breath, severe fatigue, dizziness, heart palpitations, appetite problems, and constipation. They also lead to lifestyle modifications that affect the patient’s psychological well-being and QoL and increase their susceptibility to psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression, all of which can disrupt various aspects of their lives and hinder adjustment to the disease [8]. Adjustment to these diseases is considered a crucial transition period in a patient’s life [9]. Adjustment refers to a personal characteristic that helps individuals manage psychosocial factors for improvement in their lives. The process of adjustment to a chronic disease is dynamic and continually influenced by individual and environmental factors. Throughout this process, individuals should cope with personal and environmental challenges to reach an acceptable level of health and physical, mental, and social functioning and, as a result, achieve successful adjustment [10]. Impaired psycho-social adjustment can lead to issues such as sleep disturbances, restlessness, irritability, nervousness, fatigue, anxiety, lack of concentration, emotional instability, and social withdrawal [11]. Samadzade reported that, among 215 individuals with diabetes, those with low psycho-social adjustment to their illness utilized healthcare services 2-6 times more frequently and spent 2.5-4 times higher costs compared to those with high adjustment [12]. The inability to adjust to the disease may also have negative consequences such as non-acceptance of treatment, reduced QoL [13], lower adherence to treatment regimens [14], and slower recovery rate [3].

Despite advancements in pharmaceutical and psychological treatments, changing patient behavior to promote their adjustment to chronic diseases and their treatment adherence remains controversial [15]. There is currently no validated tool to measure the overall level of adjustment to chronic diseases in Iran. There is one available tool called the psychosocial adjustment to illness scale (PAIS), developed by Derogatis in 1990, that evaluates seven domains: Healthcare orientation, sexual relationships, vocational environment, domestic environment, extended family relationships, psychological distress, and social environment [16]. However, it is not specifically for chronic diseases. Hence, there is a need for a tool specific to chronic diseases, particularly CVDs. In this regard, the adaptation to chronic illness scale (ACIS) was developed for patients with CVDs (coronary artery disease) in Turkey in 2016 [17]. It has 25 items and three subscales of physical, psychological, and social adaptation. This questionnaire has several advantages, including its low number of items suitable for individuals with chronic illnesses and its novelty compared to existing tools.

Given that the QoL improvement process for individuals with CVDs is influenced by their level of adaptation to the disease, and the need for a specific tool for its measurement, and considering the lack of a tool for assessing adaptation to the disease in CVD patients in Iran, this study aimed to assess the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the ACIS for this group.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional and psychometrics study. The study population consists of individuals diagnosed with CVDs referred to the hospitals in Tehran, Iran. Inclusion criteria were: Having heart failure, coronary artery disease, angina pectoris, or myocardial infarction, undergoing angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery confirmed by a cardiologist, awareness of the chronic condition, diagnosis with the disease for at least three months, proficiency in Persian language, ability to read and write, and willingness to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were the distortion of the questionnaire and unwillingness to continue cooperation in the study.

For developing a psychometric instrument, Ghasemi suggests that a sample size of <100 is inadequate, and it should be more than 200 [18]. Given that the ACIS has 25 items, and following statistical recommendations [19], 250 CVD patients were initially determined (10 participants per item). However, due to limited access to participants in hospitals, the final sample size was 211. Among these samples, 10 participated in the face validity assessment, 50 completed the questionnaire for test re-test reliability assessment, and another 50 filled out the PAIS questionnaire for concurrent validity assessment. The participants were selected from Shahid Rajaee Hospital (n=105) and Shariati Heart Center (n=106) in Tehran, who visited these hospitals from July to September 2021.

Instruments

Data collection was done using a demographic form and the Persian versions of the ACIS and PAIS. The ACIS scale, developed by Atik and Karatepe [17], assesses the adaptation to chronic diseases. The scale has 25 items divided into three components: 11 items for physical adaptation (1, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 22, 23, 24), 7 items for psychological adaptation (4, 6, 8, 11, 12, 20, 21), and 7 questions for social adaptation (2, 3, 5, 7, 17, 19, 25). The scale employs a Likert-type scoring system as 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (undecided), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree). Items 5, 6, 12, 17, 19, 20, 24, and 25 have reversed scoring. The total score for the physical domain ranges from 11 to 55, while for psychological and social domains, it ranges from 7 to 35. The total score of the scale ranges from 25 to 125, with higher scores indicating higher adaptation to the chronic disease. The ACIS has Cronbach’s α (internal consistency) and Spearman-Brown and Guttman split-half reliability coefficients >0.70 for all subscales.

The PAIS, developed by Derogatis et al. in 1990, evaluates the psychosocial adjustment to the illness or its residual effects. It has 46 items and seven domains: Health care orientation (8 items), domestic environment (8 items), vocational environment (6 items), sexual relationships (6 items), social environment (6 items), extended family relationships (5 items), and psychological distress (7 items) [20]. The questionnaire uses a four-point Likert scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (slightly), 2 (to some extent), and 3 (completely). The average score for each domain is determined by summing of the scores of each domain divided by the number of items in that domain. The total score is calculated by summing up of the scores of all domains divided by the total number of items. In this regard, the PAIS has an average total score of 33%. Based on this score, the adjustment is categorized into three levels: High (<1), moderate (1-2), and low (>2) [10]. The PAIS has advantages such as strong psychometric properties, availability in both self-report form and physician interview format, and norm scores for various medical conditions such as cancer, multiple sclerosis, and renal failure. However, it provides no information about the effects of possible biases [21]. Feghhi et al. translated the PAIS to Persian in 2012. Content validity was verified by 10 experts, and Cronbach’s α was obtained as 0.94 for patients with type 2 diabetes [10].

Study procedure

The ACIS’s translation process started after obtaining permission from the developer and ethics approval. The forward-backward method was employed for translation. First, it was translated into Persian by two translators fluent in English. After meeting with the translators, a unified Persian draft was prepared. Then, it was back translated into English by two other experts. After solving the disagreements, a unified English draft was prepared and sent to the developer for approval. The supervisors and the developer both approved the final draft. After obtaining a written informed consent from the participants, the questionnaires were administered for completion.

To assess face validity, the questionnaire was administered to 5 experts in counseling and psychology to give their opinions about the clarity, simplicity, relevance, and necessity of the items. The content validity ratio (CVR) was then calculated based on their ratings for the necessity of each item, using the formula CVR=(ne-N⁄2)/(N⁄2), where denotes the number of experts who considered the item “necessary” or “useful but unnecessary,” and N is the total number of experts. For assessing the item content validity index (I-CVI), experts were asked to rate the relevance of each item. The CVI for each item was calculated by dividing the number of experts who rated either 3 or 4 by the total number of experts, producing a ratio between 0 and 1 that indicates the degree of consensus on relevance. Concurrent validity was evaluated by administering both ACIS and PAIS to 50 participants and using Pearson’s correlation test to examine the correlation between their scores. To evaluate the reliability, Cronbach’s α was calculated to measure internal consistency, and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to assess the test re-test reliability. In this regard, the ACIS was administered to 50 participants at a two-week interval. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 23. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was utilized to confirm the construct validity of the Persian ACIS. This method tests the optimal fit of the observed and theoretical factor structures to the dataset [22]. The CFA was conducted in LISREL software.

Results

Among 211 participants, 115 were male (54.5%) and 96 were female (45.5%). They had a mean age of 58.07±8.435 years, ranged 35-85. There were 63 patients with heart failure, 10 with a history of myocardial infarction, 78 with a history of angioplasty, 37 with a history of bypass surgery, and 14 with coronary artery disease. Regarding the disease duration, 42 participants had the diagnosis for less than a year (more than three months), 84 for 1-4 years, 65 for 5-9 years, and 18 for ≥10 years.

In assessing the face validity, the patients and experts approved the appearance or wording of the questions. In evaluating the content validity, the CVR was obtained as 0.99, and the I-CVI ranged from 0.8 to 1, showing acceptable content validity. The calculated kappa values (0.76-1) also confirmed the content validity.

The Pearson correlation test results showed a significant negative correlation between the total scores of the ACIS and PAIS (r=-0.757, P<0.05). Also, a significant negative correlation was found between the scores of the PAIS subscale of psychological distress and the ACIS subscale of psychological adaptation (r=-0.642, P<0.05) and between the scores of the PAIS health care orientation subscale and the ACIS physical adaptation subscale (r=-0.655, P<0.05). Additionally, the scores of the social environment and vocational environment, as two subscales of the PAIS, had a significant and negative correlation with the ACIS social adaptation subscale score (R=-0.585 and -0.580, respectively; P<0.05). Since the higher ACIS score shows better adaptation, while higher PAIS scores indicate poorer adjustment to the disease, the observed negative correlation coefficients were expected. These findings confirmed the concurrent validity of the Persian ACIS.

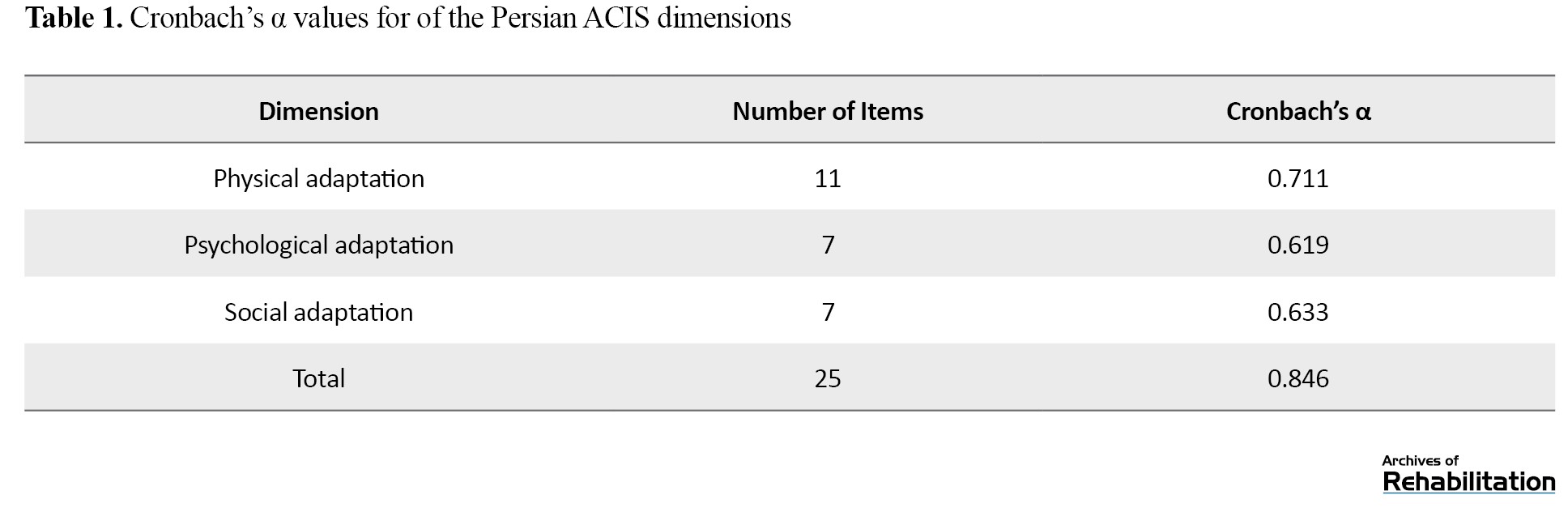

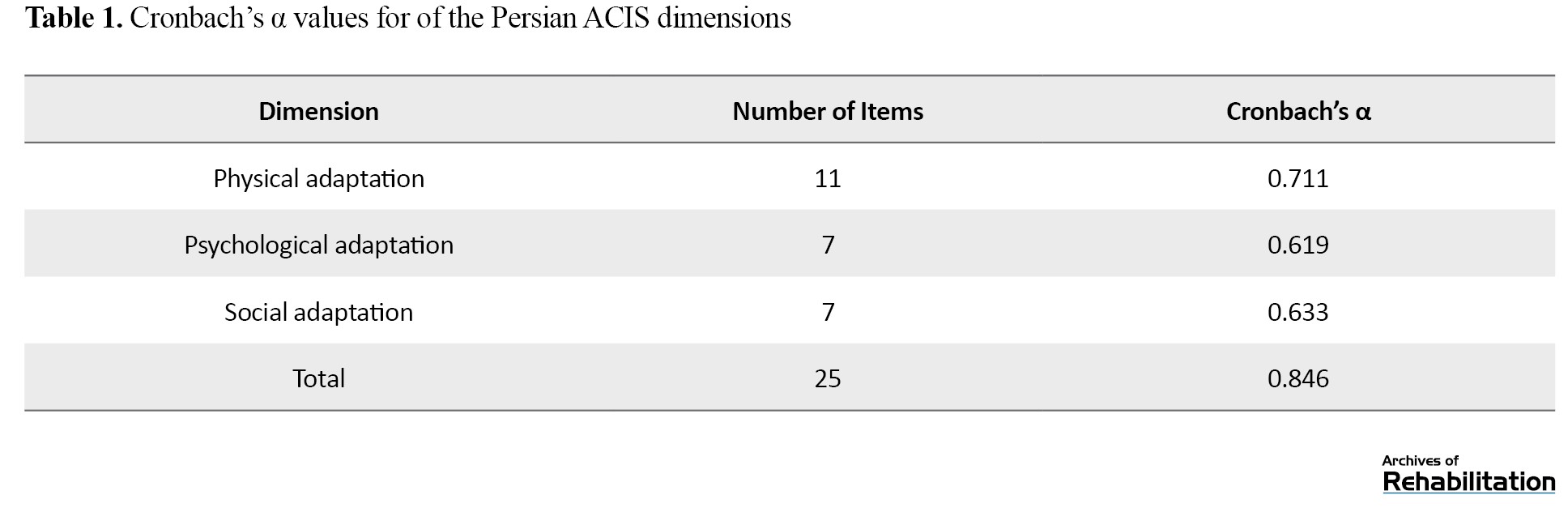

Cronbach’s α for the overall ACIS was obtained at 0.846, indicating the excellent internal consistency of the Persian version. Table 1 presents the Cronbach’s α values for the subscales of the ACIS (Table 1).

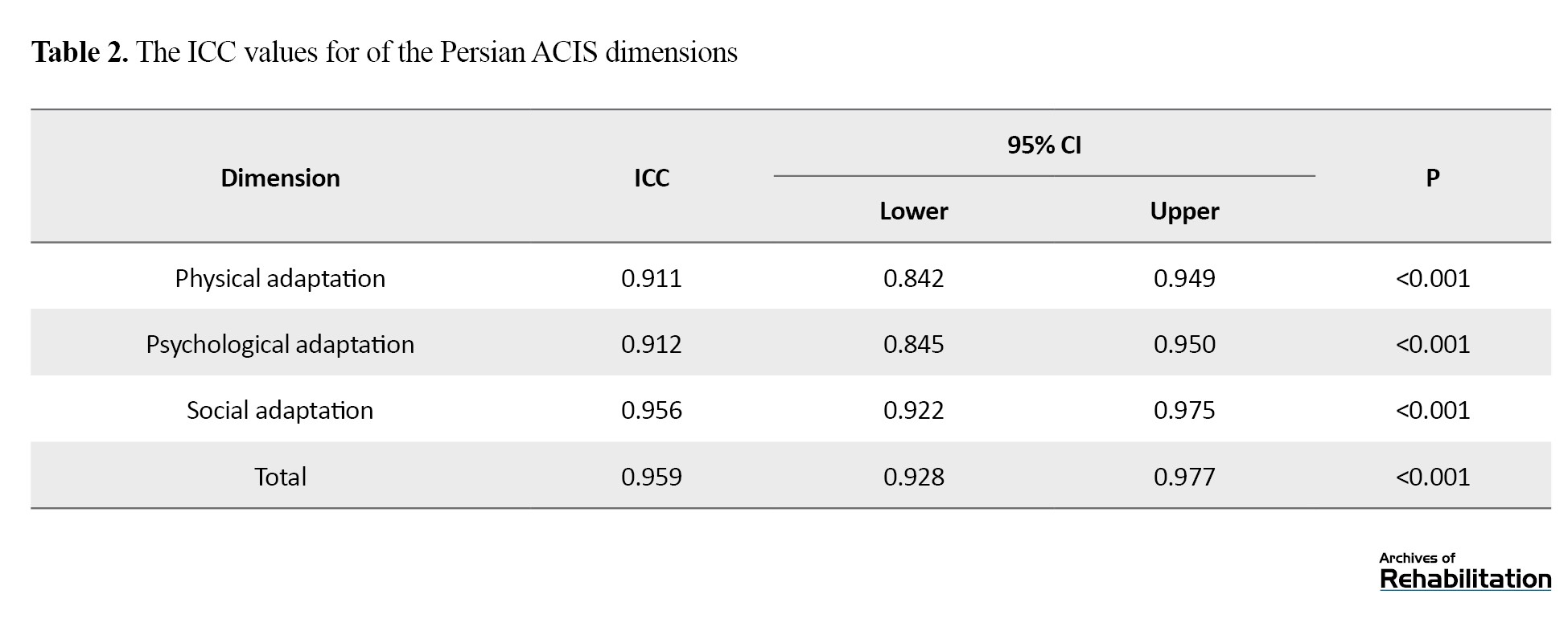

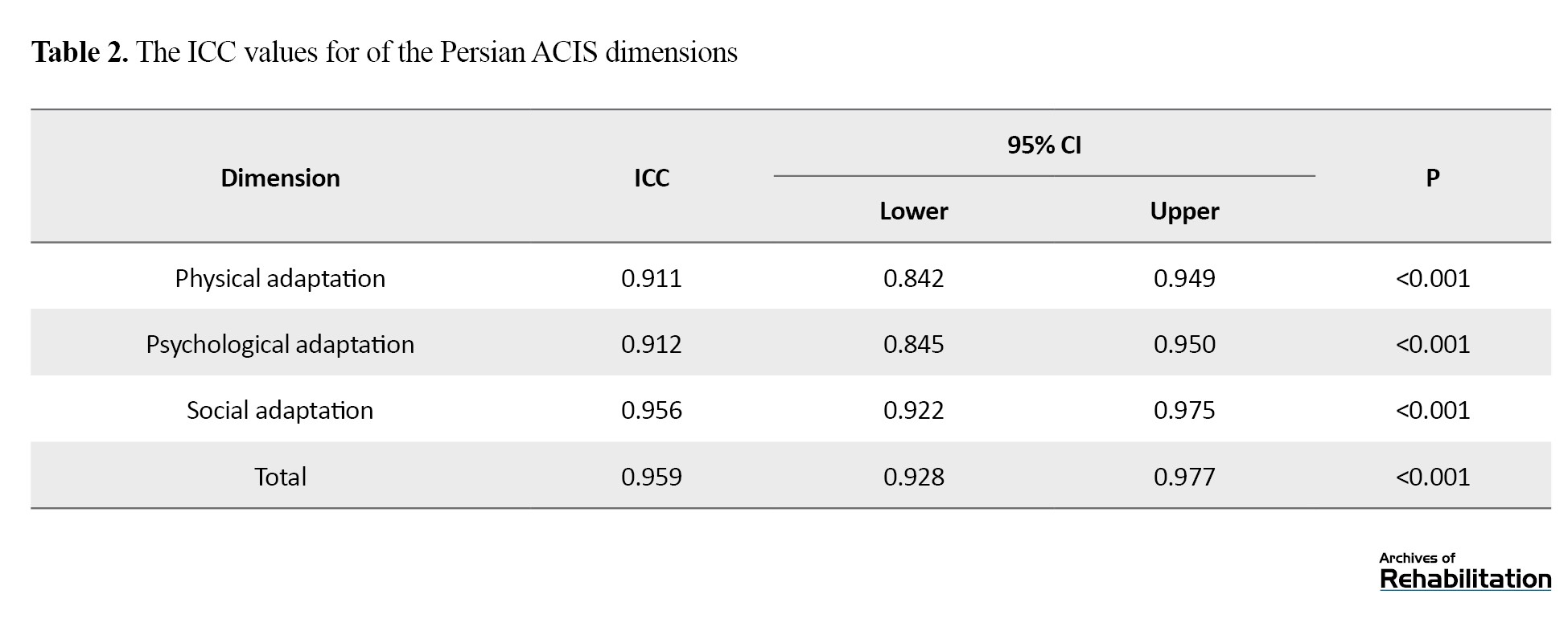

The results indicated that the three subscales also had good internal consistency. The ICC value for the overall ACIS was 0.95, indicating its appropriate test re-test reliability. Table 2 presents the ICC values for the subscales.

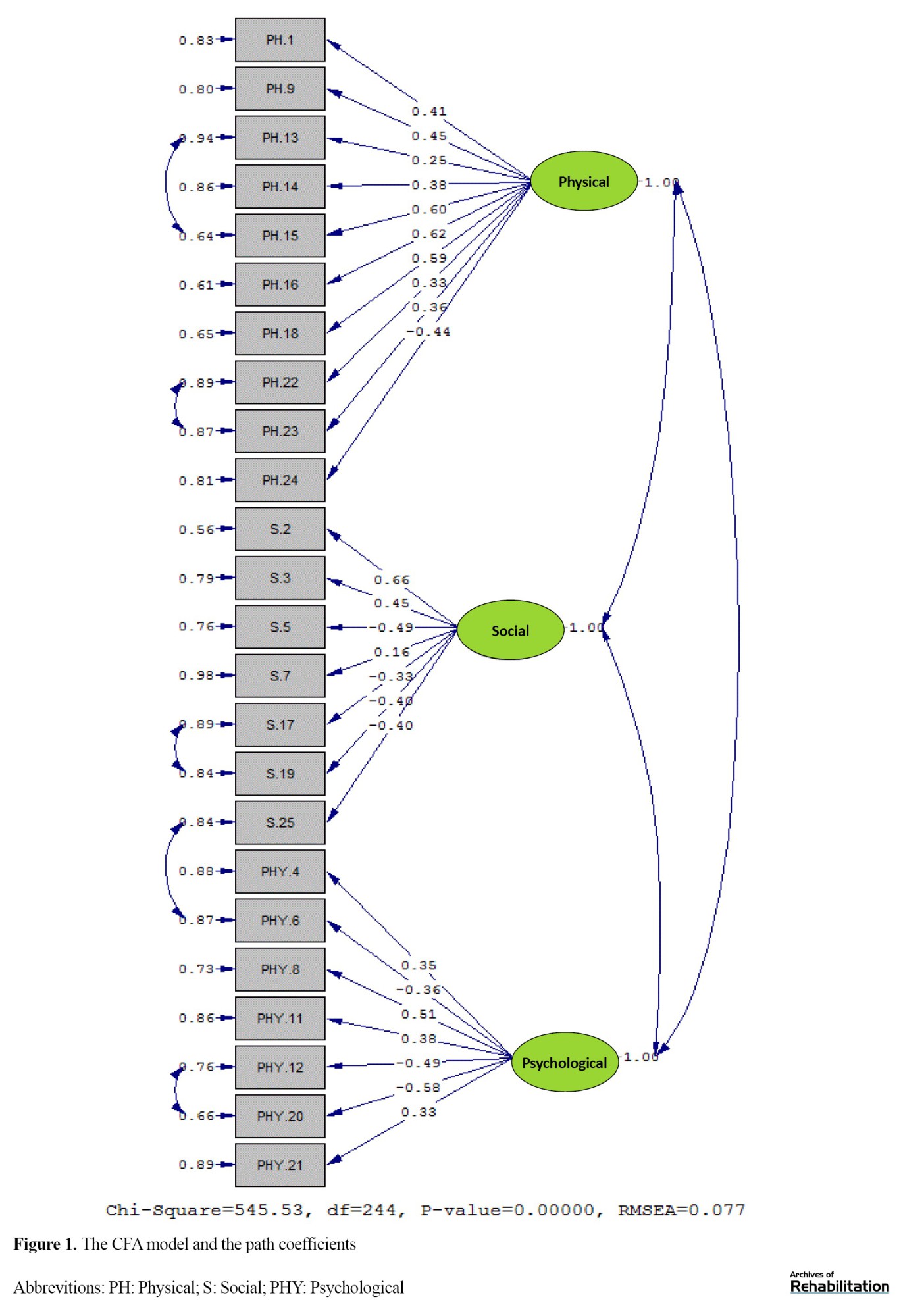

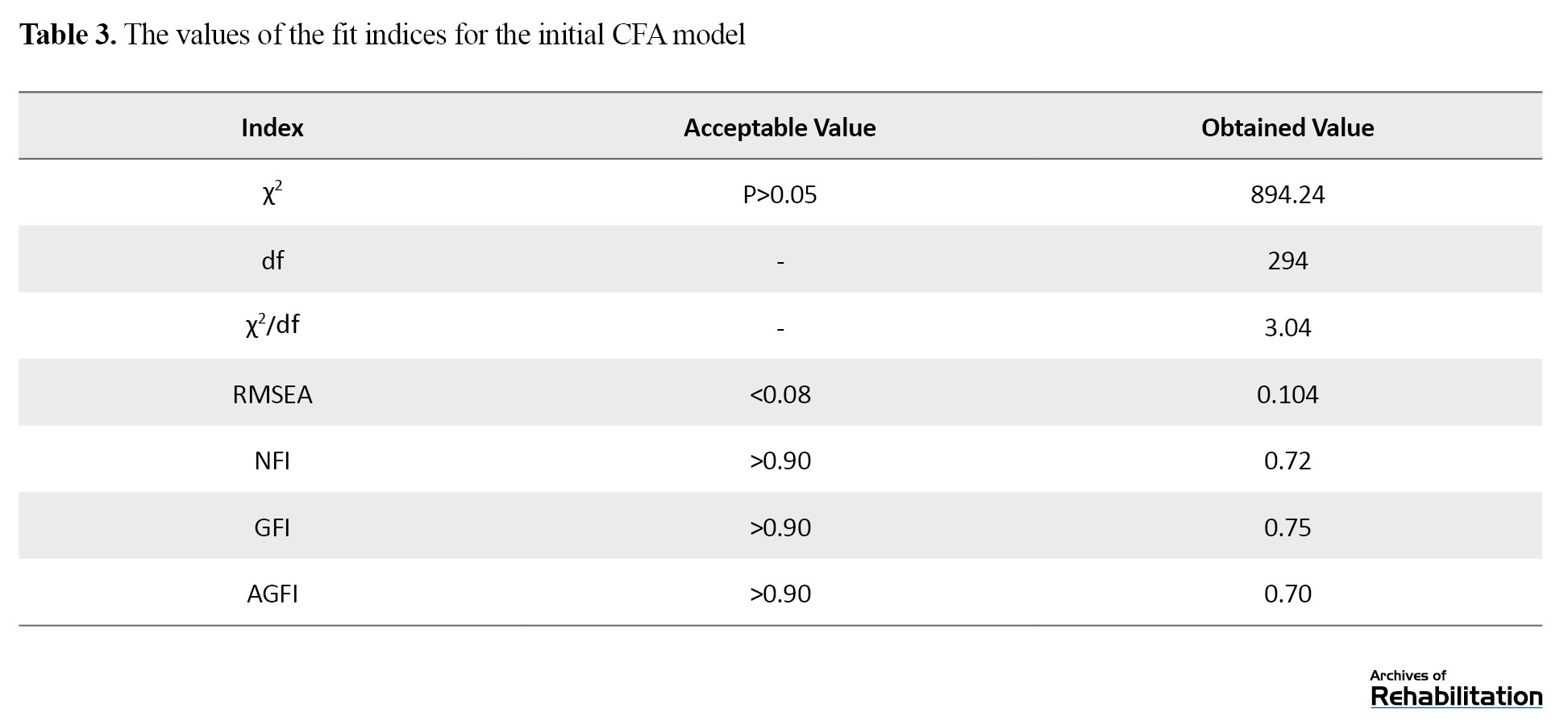

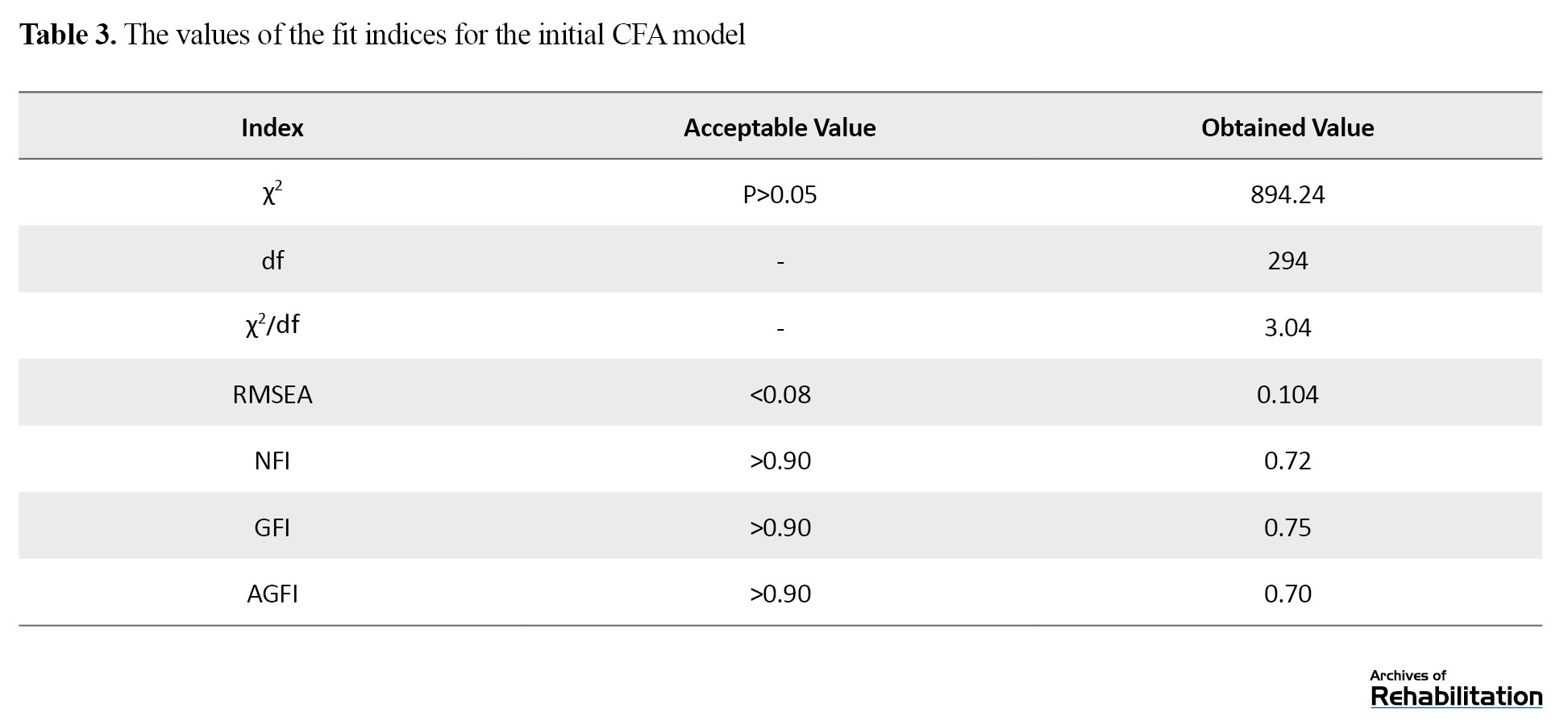

Table 3 reports the values for the fit indices in the initial CFA model.

The P was >0.05, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.08. Additionally, the values of the fit indices were less than the acceptable value (0.9). Based on these calculated values, the fit of the initial model to the observed data was not approved. To improve the model, item 10 from the physical subscale (“Due to my illness, I should be under supervision for a long time”) was removed due to its low factor loading and statistics. Additionally, the covariation of observed errors was calculated for the following pairs of items which were for the same constructs:

“I do my own chores at home” and “I have a regular diet due to my disease.”

“I feel like a burden to my family because of my disease” and “The disease has a negative impact on my friendships.”

“I have enough information about my disease” and “I have enough information about my treatment.”

“It is very difficult for me to live cautiously due to my disease” and “The disease makes me worried.”

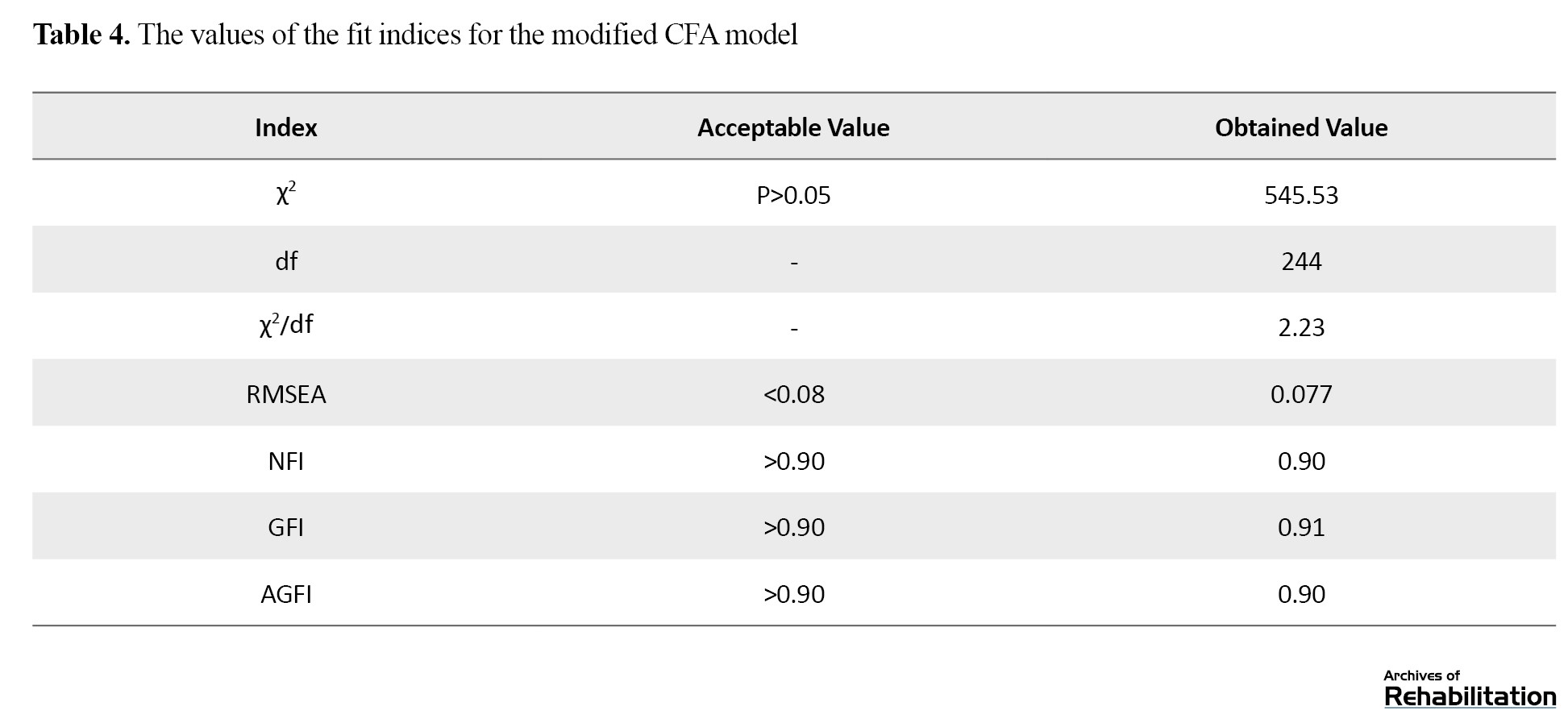

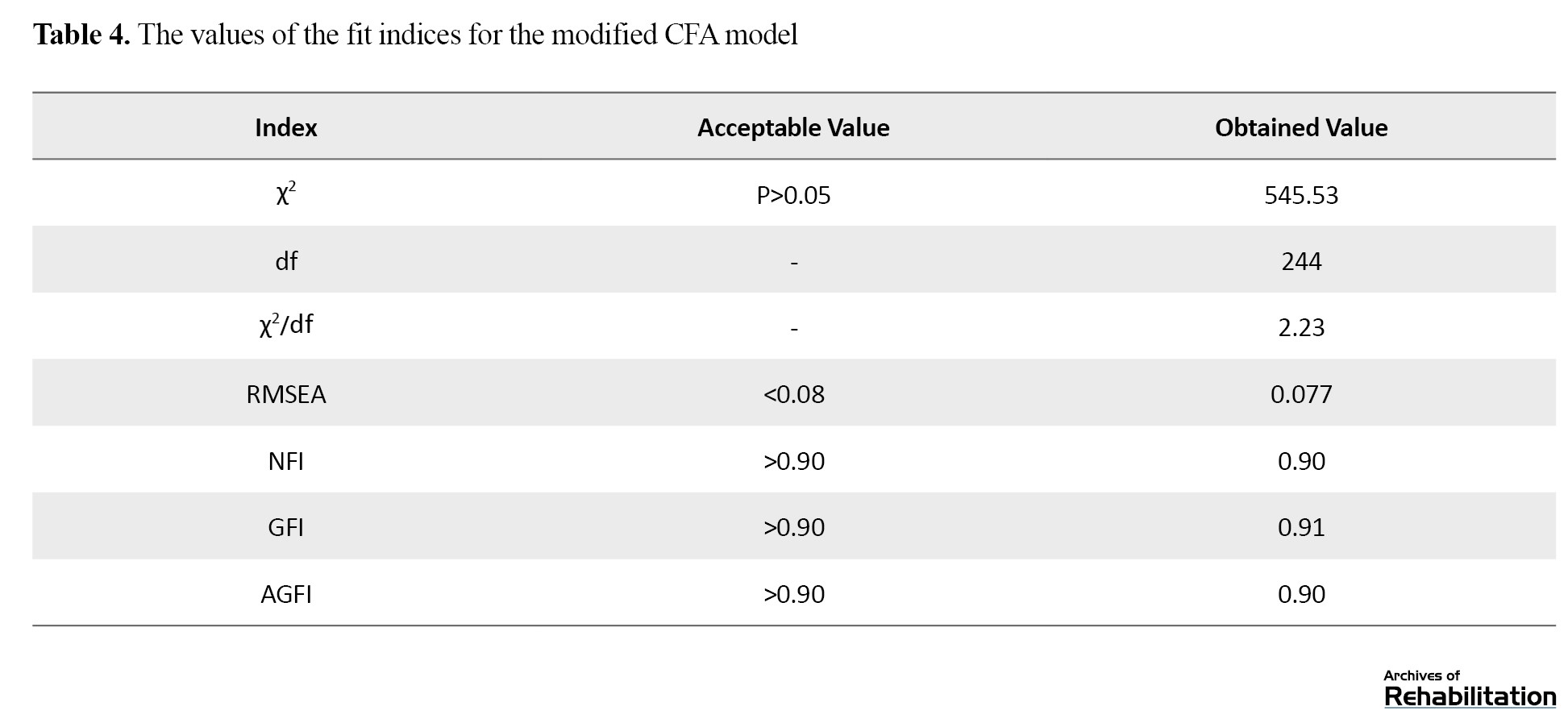

The covariation of errors for the items “The disease has had a negative impact on my work life” and “My disease prevents me from planning for the future” was assessed due to overlapping. The fit indices were then re-calculated to ensure the fit of the model. Table 4 shows the results after modification.

As can be seen, RMSEA=0.077, goodness of fit index (GFI)=0.91, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI)=0.90, and normed fit index (NFI)= 0.90. Since the RMSEA was below 0.08 and the values of all fit indicators were >0.9, the results suggest that the theoretical model had a good fit to the observed data. Table 4 shows the standard path coefficients and T values for the modified model. As shown in Figure 1, the significance level of all the paths in the model was less than 0.01, indicating that these paths were statistically significant. Therefore, it can be said that the mentioned paths are statistically significant. For example, the standard path coefficient and the coefficient of determination for the first item in the physical subscale were 0.41 and 16.81, respectively.

In summary, considering the calculated indicators (both good and bad), the exploratory factors identified in the previous study, with the exception of item 10, are confirmed in the present study

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the ACIS. The results showed its appropriate content validity (CVR=0.99). This is consistent with the results for the original version [17]. In Vicdan and Birgili’s study, CVR ranged from 0.87 to 0.99 [23]. In assessing concurrent validity, a significant negative correlation was observed between the total scores of the Persian ACIS and PAIS, which confirmed the concurrent validity of the Persian ACIS. For the original version, a significant correlation was also reported between the ACIS and PAIS total scores [17]. Rodrigue et al. identified significant correlations between the scores of the subscales of the PAIS and the 36-item short form health survey (SF-36), indicating that better QoL was associated with improved adjustment to the disease [24]. Merluzzi and Sanchez reported an association between the PAIS score and mental health indicators [25]. These findings indirectly support the results of the present study.

In our study, a negative correlation was observed between social environment and vocational environment, as two subscales of the PAIS, with the ACIS social adaptation subscale score. This is consistent with the findings of Ghamary et al. [26], Moosavi et al. [27], and Besharat et al. [9]. They also reported a significant positive correlation between social support and psychosocial adjustment in patients. These studies suggested that social support generally helps patients, their families, and friends cope with the diseases.

Our results also indicated a negative correlation between the PAIS healthcare orientation subscale and the ACIS physical adaptation subscale, suggesting that a positive attitude towards the disease correlates with higher physical adaptation to the disease. These results are supported by Dennison et al. [28] and Michael L Miller [29], who emphasized that individuals’ mental perceptions and attitudes towards their illness, along with their coping strategies, surpass biomedical factors in influencing the disease process.

We also found a negative correlation between the scores of the PAIS subscale of psychological distress and the ACIS subscale of psychological adaptation, which is consistent with the results reported by Kocaman et al. [30] and Lacombe-Trejo et al. [31]. These studies suggest that individuals who fully understand the nature, severity, and consequences of their illness and disabilities may experience symptoms such as depression, helplessness, frustration, and discouragement.

In this study, the reliability of the Persian ACIS was confirmed by evaluating its internal consistency and test re-test reliability. According to Cronbach’s α values, the psychological and social subscales had acceptable internal consistency, while the physical subscale had good internal consistency. The ICC values also showed the good testre-test reliability of the Persian version. These results are consistent with those reported by Atik and Karatepe [17] and Vicdan and Birgili [23].

In assessing the construct validity of the Persian ACIS, the results did not show the acceptable fit of the CFA model, since item 10 in the physical subscale had low factor loading and was not significant. In this regard, this item was removed. The inconsistency in construct validity of the Persian and original versions may be due to cultural and societal differences regarding patient support and perception. Iranian patients may perceive and respond to items differently compared to their counterparts in Turkey. In Vicdan and Birgili’s study, the CFA confirmed the 4-dimensional model (physical, psychological, social, and spiritual) with 28 items [23].

This study faced some limitations. Firstly, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was limited cooperation from hospital staff at Tehran Heart Hospital regarding sampling, and there was a reduced number of CVD patients referred to hospitals during this period. Additionally, the questionnaire may need to be used cautiously for patients who are not literate.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings showed the validity and reliability of the Persian version of the ACIS for assessing the adaptation to disease in Iranian Patients with CVDs. It has acceptable concurrent validity, face and content validity, internal consistency, and test re-test reliability. The three-factor structure of the ACIS was confirmed after removing one item. As a result, the Persian ACIS has 24 items across three subscales of mental, physical, and social adaptation. It is the first scale in Persian that was validated to measure adaptation to chronic illness in Iranian patients, and can be used in clinical settings and research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards set by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.240). Prior to the study, all participants signed an informed consent form to participate in the study. They were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master’s thesis of Farzaneh Ebrahimgol, approved by the Department of Counseling, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol, and Manoochehr Azkhosh; Methodology: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol, and Samaneh Hossinzadeh; Analysis: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani and Farzaneh Ebrahimgol; Investigation and resources: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol, and Maryam Latifian; Preparing the initial draft: Maryam Latifian and Mohammad Saeed Khanjani; Review and editing: Maryam Latifian, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Sahar Esmaeili; Supervision: Manoochehr Azkhosh, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Maryam Latifian; Translation: Sahar Esmaeili.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients and experts who participated in this study, as well as the officials of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, for their valuable cooperation.

References

Achronic disease is a long-lasting condition that leads to physical limitations in the body and restricts the patient’s daily living activities. For these diseases, the treatment takes along time and the recovery is difficult. In some cases, there is no definitive cure [1]. Although these diseases are not directly fatal, they can disrupt the quality of life (QoL) and lead to early and severe disabilities [2]. Chronic diseases account for 60% of all deaths worldwide, and their prevalence can be seen in all regions and socioeconomic classes [3]. Chronic diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the major causes of death and contribute significantly to disability and mortality [4]. The CVDs are a group of disorders of the heart and blood vessels [5]. Heart failure is defined as progressive damage to the heart due to its inability to circulate blood properly throughout the body. This disease is one of the three main causes of death in industrialized countries. Although mortality from CVDs has decreased in recent years in developed countries, evidence suggests that lifestyle changes have led to an increasing prevalence of CVDs in Iran [6], where it is the leading cause of death for individuals over 35 years of age [7].

The CVDs can cause many symptoms such as shortness of breath, severe fatigue, dizziness, heart palpitations, appetite problems, and constipation. They also lead to lifestyle modifications that affect the patient’s psychological well-being and QoL and increase their susceptibility to psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression, all of which can disrupt various aspects of their lives and hinder adjustment to the disease [8]. Adjustment to these diseases is considered a crucial transition period in a patient’s life [9]. Adjustment refers to a personal characteristic that helps individuals manage psychosocial factors for improvement in their lives. The process of adjustment to a chronic disease is dynamic and continually influenced by individual and environmental factors. Throughout this process, individuals should cope with personal and environmental challenges to reach an acceptable level of health and physical, mental, and social functioning and, as a result, achieve successful adjustment [10]. Impaired psycho-social adjustment can lead to issues such as sleep disturbances, restlessness, irritability, nervousness, fatigue, anxiety, lack of concentration, emotional instability, and social withdrawal [11]. Samadzade reported that, among 215 individuals with diabetes, those with low psycho-social adjustment to their illness utilized healthcare services 2-6 times more frequently and spent 2.5-4 times higher costs compared to those with high adjustment [12]. The inability to adjust to the disease may also have negative consequences such as non-acceptance of treatment, reduced QoL [13], lower adherence to treatment regimens [14], and slower recovery rate [3].

Despite advancements in pharmaceutical and psychological treatments, changing patient behavior to promote their adjustment to chronic diseases and their treatment adherence remains controversial [15]. There is currently no validated tool to measure the overall level of adjustment to chronic diseases in Iran. There is one available tool called the psychosocial adjustment to illness scale (PAIS), developed by Derogatis in 1990, that evaluates seven domains: Healthcare orientation, sexual relationships, vocational environment, domestic environment, extended family relationships, psychological distress, and social environment [16]. However, it is not specifically for chronic diseases. Hence, there is a need for a tool specific to chronic diseases, particularly CVDs. In this regard, the adaptation to chronic illness scale (ACIS) was developed for patients with CVDs (coronary artery disease) in Turkey in 2016 [17]. It has 25 items and three subscales of physical, psychological, and social adaptation. This questionnaire has several advantages, including its low number of items suitable for individuals with chronic illnesses and its novelty compared to existing tools.

Given that the QoL improvement process for individuals with CVDs is influenced by their level of adaptation to the disease, and the need for a specific tool for its measurement, and considering the lack of a tool for assessing adaptation to the disease in CVD patients in Iran, this study aimed to assess the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the ACIS for this group.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional and psychometrics study. The study population consists of individuals diagnosed with CVDs referred to the hospitals in Tehran, Iran. Inclusion criteria were: Having heart failure, coronary artery disease, angina pectoris, or myocardial infarction, undergoing angioplasty or coronary artery bypass surgery confirmed by a cardiologist, awareness of the chronic condition, diagnosis with the disease for at least three months, proficiency in Persian language, ability to read and write, and willingness to participate in the study. Exclusion criteria were the distortion of the questionnaire and unwillingness to continue cooperation in the study.

For developing a psychometric instrument, Ghasemi suggests that a sample size of <100 is inadequate, and it should be more than 200 [18]. Given that the ACIS has 25 items, and following statistical recommendations [19], 250 CVD patients were initially determined (10 participants per item). However, due to limited access to participants in hospitals, the final sample size was 211. Among these samples, 10 participated in the face validity assessment, 50 completed the questionnaire for test re-test reliability assessment, and another 50 filled out the PAIS questionnaire for concurrent validity assessment. The participants were selected from Shahid Rajaee Hospital (n=105) and Shariati Heart Center (n=106) in Tehran, who visited these hospitals from July to September 2021.

Instruments

Data collection was done using a demographic form and the Persian versions of the ACIS and PAIS. The ACIS scale, developed by Atik and Karatepe [17], assesses the adaptation to chronic diseases. The scale has 25 items divided into three components: 11 items for physical adaptation (1, 9, 10, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 22, 23, 24), 7 items for psychological adaptation (4, 6, 8, 11, 12, 20, 21), and 7 questions for social adaptation (2, 3, 5, 7, 17, 19, 25). The scale employs a Likert-type scoring system as 1 (strongly disagree), 2 (disagree), 3 (undecided), 4 (agree), and 5 (strongly agree). Items 5, 6, 12, 17, 19, 20, 24, and 25 have reversed scoring. The total score for the physical domain ranges from 11 to 55, while for psychological and social domains, it ranges from 7 to 35. The total score of the scale ranges from 25 to 125, with higher scores indicating higher adaptation to the chronic disease. The ACIS has Cronbach’s α (internal consistency) and Spearman-Brown and Guttman split-half reliability coefficients >0.70 for all subscales.

The PAIS, developed by Derogatis et al. in 1990, evaluates the psychosocial adjustment to the illness or its residual effects. It has 46 items and seven domains: Health care orientation (8 items), domestic environment (8 items), vocational environment (6 items), sexual relationships (6 items), social environment (6 items), extended family relationships (5 items), and psychological distress (7 items) [20]. The questionnaire uses a four-point Likert scale: 0 (not at all), 1 (slightly), 2 (to some extent), and 3 (completely). The average score for each domain is determined by summing of the scores of each domain divided by the number of items in that domain. The total score is calculated by summing up of the scores of all domains divided by the total number of items. In this regard, the PAIS has an average total score of 33%. Based on this score, the adjustment is categorized into three levels: High (<1), moderate (1-2), and low (>2) [10]. The PAIS has advantages such as strong psychometric properties, availability in both self-report form and physician interview format, and norm scores for various medical conditions such as cancer, multiple sclerosis, and renal failure. However, it provides no information about the effects of possible biases [21]. Feghhi et al. translated the PAIS to Persian in 2012. Content validity was verified by 10 experts, and Cronbach’s α was obtained as 0.94 for patients with type 2 diabetes [10].

Study procedure

The ACIS’s translation process started after obtaining permission from the developer and ethics approval. The forward-backward method was employed for translation. First, it was translated into Persian by two translators fluent in English. After meeting with the translators, a unified Persian draft was prepared. Then, it was back translated into English by two other experts. After solving the disagreements, a unified English draft was prepared and sent to the developer for approval. The supervisors and the developer both approved the final draft. After obtaining a written informed consent from the participants, the questionnaires were administered for completion.

To assess face validity, the questionnaire was administered to 5 experts in counseling and psychology to give their opinions about the clarity, simplicity, relevance, and necessity of the items. The content validity ratio (CVR) was then calculated based on their ratings for the necessity of each item, using the formula CVR=(ne-N⁄2)/(N⁄2), where denotes the number of experts who considered the item “necessary” or “useful but unnecessary,” and N is the total number of experts. For assessing the item content validity index (I-CVI), experts were asked to rate the relevance of each item. The CVI for each item was calculated by dividing the number of experts who rated either 3 or 4 by the total number of experts, producing a ratio between 0 and 1 that indicates the degree of consensus on relevance. Concurrent validity was evaluated by administering both ACIS and PAIS to 50 participants and using Pearson’s correlation test to examine the correlation between their scores. To evaluate the reliability, Cronbach’s α was calculated to measure internal consistency, and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was used to assess the test re-test reliability. In this regard, the ACIS was administered to 50 participants at a two-week interval. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software, version 23. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was utilized to confirm the construct validity of the Persian ACIS. This method tests the optimal fit of the observed and theoretical factor structures to the dataset [22]. The CFA was conducted in LISREL software.

Results

Among 211 participants, 115 were male (54.5%) and 96 were female (45.5%). They had a mean age of 58.07±8.435 years, ranged 35-85. There were 63 patients with heart failure, 10 with a history of myocardial infarction, 78 with a history of angioplasty, 37 with a history of bypass surgery, and 14 with coronary artery disease. Regarding the disease duration, 42 participants had the diagnosis for less than a year (more than three months), 84 for 1-4 years, 65 for 5-9 years, and 18 for ≥10 years.

In assessing the face validity, the patients and experts approved the appearance or wording of the questions. In evaluating the content validity, the CVR was obtained as 0.99, and the I-CVI ranged from 0.8 to 1, showing acceptable content validity. The calculated kappa values (0.76-1) also confirmed the content validity.

The Pearson correlation test results showed a significant negative correlation between the total scores of the ACIS and PAIS (r=-0.757, P<0.05). Also, a significant negative correlation was found between the scores of the PAIS subscale of psychological distress and the ACIS subscale of psychological adaptation (r=-0.642, P<0.05) and between the scores of the PAIS health care orientation subscale and the ACIS physical adaptation subscale (r=-0.655, P<0.05). Additionally, the scores of the social environment and vocational environment, as two subscales of the PAIS, had a significant and negative correlation with the ACIS social adaptation subscale score (R=-0.585 and -0.580, respectively; P<0.05). Since the higher ACIS score shows better adaptation, while higher PAIS scores indicate poorer adjustment to the disease, the observed negative correlation coefficients were expected. These findings confirmed the concurrent validity of the Persian ACIS.

Cronbach’s α for the overall ACIS was obtained at 0.846, indicating the excellent internal consistency of the Persian version. Table 1 presents the Cronbach’s α values for the subscales of the ACIS (Table 1).

The results indicated that the three subscales also had good internal consistency. The ICC value for the overall ACIS was 0.95, indicating its appropriate test re-test reliability. Table 2 presents the ICC values for the subscales.

Table 3 reports the values for the fit indices in the initial CFA model.

The P was >0.05, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was 0.08. Additionally, the values of the fit indices were less than the acceptable value (0.9). Based on these calculated values, the fit of the initial model to the observed data was not approved. To improve the model, item 10 from the physical subscale (“Due to my illness, I should be under supervision for a long time”) was removed due to its low factor loading and statistics. Additionally, the covariation of observed errors was calculated for the following pairs of items which were for the same constructs:

“I do my own chores at home” and “I have a regular diet due to my disease.”

“I feel like a burden to my family because of my disease” and “The disease has a negative impact on my friendships.”

“I have enough information about my disease” and “I have enough information about my treatment.”

“It is very difficult for me to live cautiously due to my disease” and “The disease makes me worried.”

The covariation of errors for the items “The disease has had a negative impact on my work life” and “My disease prevents me from planning for the future” was assessed due to overlapping. The fit indices were then re-calculated to ensure the fit of the model. Table 4 shows the results after modification.

As can be seen, RMSEA=0.077, goodness of fit index (GFI)=0.91, adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI)=0.90, and normed fit index (NFI)= 0.90. Since the RMSEA was below 0.08 and the values of all fit indicators were >0.9, the results suggest that the theoretical model had a good fit to the observed data. Table 4 shows the standard path coefficients and T values for the modified model. As shown in Figure 1, the significance level of all the paths in the model was less than 0.01, indicating that these paths were statistically significant. Therefore, it can be said that the mentioned paths are statistically significant. For example, the standard path coefficient and the coefficient of determination for the first item in the physical subscale were 0.41 and 16.81, respectively.

In summary, considering the calculated indicators (both good and bad), the exploratory factors identified in the previous study, with the exception of item 10, are confirmed in the present study

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to assess the psychometric properties of the Persian version of the ACIS. The results showed its appropriate content validity (CVR=0.99). This is consistent with the results for the original version [17]. In Vicdan and Birgili’s study, CVR ranged from 0.87 to 0.99 [23]. In assessing concurrent validity, a significant negative correlation was observed between the total scores of the Persian ACIS and PAIS, which confirmed the concurrent validity of the Persian ACIS. For the original version, a significant correlation was also reported between the ACIS and PAIS total scores [17]. Rodrigue et al. identified significant correlations between the scores of the subscales of the PAIS and the 36-item short form health survey (SF-36), indicating that better QoL was associated with improved adjustment to the disease [24]. Merluzzi and Sanchez reported an association between the PAIS score and mental health indicators [25]. These findings indirectly support the results of the present study.

In our study, a negative correlation was observed between social environment and vocational environment, as two subscales of the PAIS, with the ACIS social adaptation subscale score. This is consistent with the findings of Ghamary et al. [26], Moosavi et al. [27], and Besharat et al. [9]. They also reported a significant positive correlation between social support and psychosocial adjustment in patients. These studies suggested that social support generally helps patients, their families, and friends cope with the diseases.

Our results also indicated a negative correlation between the PAIS healthcare orientation subscale and the ACIS physical adaptation subscale, suggesting that a positive attitude towards the disease correlates with higher physical adaptation to the disease. These results are supported by Dennison et al. [28] and Michael L Miller [29], who emphasized that individuals’ mental perceptions and attitudes towards their illness, along with their coping strategies, surpass biomedical factors in influencing the disease process.

We also found a negative correlation between the scores of the PAIS subscale of psychological distress and the ACIS subscale of psychological adaptation, which is consistent with the results reported by Kocaman et al. [30] and Lacombe-Trejo et al. [31]. These studies suggest that individuals who fully understand the nature, severity, and consequences of their illness and disabilities may experience symptoms such as depression, helplessness, frustration, and discouragement.

In this study, the reliability of the Persian ACIS was confirmed by evaluating its internal consistency and test re-test reliability. According to Cronbach’s α values, the psychological and social subscales had acceptable internal consistency, while the physical subscale had good internal consistency. The ICC values also showed the good testre-test reliability of the Persian version. These results are consistent with those reported by Atik and Karatepe [17] and Vicdan and Birgili [23].

In assessing the construct validity of the Persian ACIS, the results did not show the acceptable fit of the CFA model, since item 10 in the physical subscale had low factor loading and was not significant. In this regard, this item was removed. The inconsistency in construct validity of the Persian and original versions may be due to cultural and societal differences regarding patient support and perception. Iranian patients may perceive and respond to items differently compared to their counterparts in Turkey. In Vicdan and Birgili’s study, the CFA confirmed the 4-dimensional model (physical, psychological, social, and spiritual) with 28 items [23].

This study faced some limitations. Firstly, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, there was limited cooperation from hospital staff at Tehran Heart Hospital regarding sampling, and there was a reduced number of CVD patients referred to hospitals during this period. Additionally, the questionnaire may need to be used cautiously for patients who are not literate.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings showed the validity and reliability of the Persian version of the ACIS for assessing the adaptation to disease in Iranian Patients with CVDs. It has acceptable concurrent validity, face and content validity, internal consistency, and test re-test reliability. The three-factor structure of the ACIS was confirmed after removing one item. As a result, the Persian ACIS has 24 items across three subscales of mental, physical, and social adaptation. It is the first scale in Persian that was validated to measure adaptation to chronic illness in Iranian patients, and can be used in clinical settings and research.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

All procedures were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards set by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, and the 1964 Helsinki Declaration. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.240). Prior to the study, all participants signed an informed consent form to participate in the study. They were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Funding

This article was extracted from the master’s thesis of Farzaneh Ebrahimgol, approved by the Department of Counseling, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol, and Manoochehr Azkhosh; Methodology: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol, and Samaneh Hossinzadeh; Analysis: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani and Farzaneh Ebrahimgol; Investigation and resources: Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, Farzaneh Ebrahimgol, and Maryam Latifian; Preparing the initial draft: Maryam Latifian and Mohammad Saeed Khanjani; Review and editing: Maryam Latifian, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Sahar Esmaeili; Supervision: Manoochehr Azkhosh, Mohammad Saeed Khanjani, and Maryam Latifian; Translation: Sahar Esmaeili.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the patients and experts who participated in this study, as well as the officials of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, for their valuable cooperation.

References

- Maghsoudi A, Mohammadi Z. [The study of prevalence of chronic diseases and its association with quality of life in the elderly of Ewaz (South of Fars province), 2014 (Persian)]. Navid No. 2016; 18(61):35-42. [DOI:10.22038/nnj.2016.6610]

- Hosseini SR, Moslehi A, Hamidian SM, Taghian SA. [The relation between chronic diseases and disability in elderly of Amirkola (Persian)]. Salmand. 2014; 9(2):80-7. [Link]

- Sahranavard S, Ahadi H, Taghdisi MH, Kazemi T, Krasekian A. [The role of psychological factors on the psychological and social adjustment through the mediation of ischemic heart disease hypertension (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Health Education and Health Promotion. 2017; 5(2):139-46. [DOI:10.30699/acadpub.ijhehp.5.2.139]

- Mahmoodi MS. [Designing a heart disease prediction system using support vector machine (Persian)]. Journal of Health and Biomedical Informatics. 2017; 4(1):1-10. [Link]

- Nazarpour S, Mehrabizadeh Honarmand M, Davoudi I, Saidean M. [Psychological and physical-biological traits as predictors of cardiovascular disease and type 2 diabetes. (Persian)]. Psychological Achievements. 2012; 19(1):139-74. [Link]

- Jafari Sejzi F, Morovati Z, Heidari R. Validation of the cardiovascular management self-efficacy scale. Medical Journal of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. 2018; 61(4):1112-21. [Link]

- DoustdarTousi SA, Golshani S. [Effect of resilience in patients hospitalized with cardiovascular diseases (Persian)]. Journal of Mazandaran University of Medical Sciences. 2014; 24(116):102-9. [Link]

- Moradi A, Hassani J, Barajali M, Abdollah Zadeh B. [Modeling structural relations of executive functions and psychological flexibility and beliefs of disease in adaptation to disease and psychological health in cardiovascular patients (Persian)]. Medical Journal of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. 2019; 62(December):147-59. [DOI:10.22038/mjms.2019.14207]

- Besharat MA, Ramesh S, Nogh H. [The predicting role of worry, anger rumination and social loneliness in adjustment to coronary artery disease (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2018; 6(4):6-15. [Link]

- Feghhi H, Saadatjoo SA, Dastjerdi R. [Psychosocial adaptation in patients with type 2 diabetes referring to Diabetes Research Center of Birjand in 2013 (Persian)]. Modern Care Journal. 2013; 10(4):249-56. [Link]

- Hassani SN, Tabiee S, Saadatjoo S, Kazemi T. The effect of an educational program based on Roy adaptation model on the psychological adaptation of patients with heart failure. Modern Care Journal. 2013; 10(4):231-40. [Link]

- Samadzade N, Poursharifi H, Babapour J. [The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral therapy on the psycho-social adjustment to illness and symptoms of depression in individuals with type II diabetes (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology Studies. 2014; 5(17):77-96.[Link]

- Aghakhani N, Hazrati Marangaloo A, Vahabzadeh D, Tayyar F. [The effect of Roy’s adaptation model-based care plan on the severity of depression, anxiety and stress in hospitalized patients with colorectal cancer (Persian)]. Hayat. 2019; 25(2):208-19. [Link]

- Halford J, Brown T. Cognitive-behavioural therapy as an adjunctive treatment in chronic physical illness. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2009; 15(4):306-17. [DOI:10.1192/apt.bp.107.003731]

- Movahedi M. [Design and test a biopsychosocial model adaptation with the disease of breast cancer (Persian)] [PhD dissertation]. Tehran: Kharazmi University; 2018.

- Babaei V, Khoshnevis E, Shabani Z. [Determining levels of psychosocial compatibility based on coping strategies and religious orientation in patients with multiple sclerosis (Persian)]. Scientific Journal of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedical Faculty. 2017; 2(4):1-12. [DOI:10.29252/sjnmp.2.4.1]

- Atik D, Karatepe H. Scale development study: Adaptation to chronic illness. Acta Medica Mediterranea. 2016; 32(1):135-42. [Link]

- Ghasemi F, Ebrahimi A, Samouei R. [A review of mental health indicators in national studies (Persian)]. Journal of Isfahan Medical School. 2018; 36(470):209-15. [DOI:10.22122/jims.v36i470.9167]

- Munro BH. Statistical methods for health care research. Philadelphia: lippincott williams & wilkins; 2005. [Link]

- Keyvan Sh, Khezri Moghadam N, Rajab A. [The effectiveness of mindfulness based stress reduction (Mbsr) on psychosocial adjustment to illness in patient with type 2 diabetes (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Diabetes and Metabolism. 2018; 17(2):105-16. [Link]

- Livneh H, Antonak RF. Psychosocial adaptation to chronic illness and disability: A primer for counselors. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2005; 83(1):12-20. [DOI:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00575.x]

- Yu Y, Choi Y. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance through the mediating effect of organizational trust in Chinese firms. Chinese Management Studies. 2014; 8(4):577-92. [DOI:10.1108/CMS-10-2013-0196]

- Vicdan AK, Birgili F. The validity and reliability study for developing an assessment scale for adaptation to chronic diseases. Journal of Current Researches on Health Sector. 2018; 8(2):135-44. [Link]

- Rodrigue JR, Kanasky WF, Jackson SI, Perri MG. The Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale-Self Report: Factor structure and item stability. Psychological Assessment. 2000; 12(4):409-13. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.12.4.409] [PMID]

- Merluzzi TV, Martinez Sanchez MA. Factor structure of the Psychosocial Adjustment to Illness Scale (Self-Report) for persons with cancer. Psychological Assessment. 1997; 9(3):269-76. [DOI:10.1037/1040-3590.9.3.269]

- Ghamary L, Sadeghi N, Azarbarzin M. [The correlations between perceived family support and psychosocial adjustment in disease in adolescents with cancer (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Nursing. 2020; 33(125):28-41. [DOI:10.29252/ijn.33.125.28]

- Moosavi T, Besharat MA, Gholamali Lavasani M. [Predicting cancer adaptation in family environment based on attachment styles, hardiness, and social support (Persian)]. Journal of Psychological Science. 2020; 19:969-79. [Link]

- Dennison L, Moss-Morris R, Silber E, Galea I, Chalder T. Cognitive and behavioural correlates of different domains of psychological adjustment in early-stage multiple sclerosis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2010; 69(4):353-61. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.04.009] [PMID]

- LeBovidge JS, Lavigne JV, Miller ML. Adjustment to chronic arthritis of childhood: The roles of illness-related stress and attitude toward illness. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005; 30(3):273-86. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsi037] [PMID]

- Kocaman N, Kutlu Y, Özkan M, Özkan S. Predictors of psychosocial adjustment in people with physical disease. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2007; 16(3a):6-16. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01809.x] [PMID]

- Lacomba-Trejo L, Valero-Moreno S, Casaña-Granell S, Prado-Gascó VJ, Pérez-Marín M, Montoya-Castilla I. Questionnaire on adaptation to type 1 diabetes among children and its relationship to psychological disorders. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem. 2018; 26:e3088. [DOI:10.1590/1518-8345.2759.3088] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Rehabilitation Management

Received: 26/05/2024 | Accepted: 24/08/2024 | Published: 1/04/2025

Received: 26/05/2024 | Accepted: 24/08/2024 | Published: 1/04/2025

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |