Volume 26, Issue 1 (Spring 2025)

jrehab 2025, 26(1): 24-43 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shiani A, Karamimatin B, Soofi M, Rezaei L, Headarzadeh-Esfahani N, Moradi F et al . An Insight Into Perceptions of Speech-language Pathologists About the Barriers to Providing Online Speech-language Therapy in Iran. jrehab 2025; 26 (1) :24-43

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3470-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3470-en.html

Amir Shiani1

, Behzad Karamimatin2

, Behzad Karamimatin2

, Moslem Soofi3

, Moslem Soofi3

, Leeba Rezaei4

, Leeba Rezaei4

, Neda Headarzadeh-Esfahani2

, Neda Headarzadeh-Esfahani2

, Fardin Moradi2

, Fardin Moradi2

, Shahin Soltani *5

, Shahin Soltani *5

, Behzad Karamimatin2

, Behzad Karamimatin2

, Moslem Soofi3

, Moslem Soofi3

, Leeba Rezaei4

, Leeba Rezaei4

, Neda Headarzadeh-Esfahani2

, Neda Headarzadeh-Esfahani2

, Fardin Moradi2

, Fardin Moradi2

, Shahin Soltani *5

, Shahin Soltani *5

1- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

2- Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

3- Social Development and Health Promotion Research Center, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

4- Sleep Disorders Research Center, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

5- Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. & Committee Research Student, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. ,shahin.soltani@kums.ac.ir

2- Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

3- Social Development and Health Promotion Research Center, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

4- Sleep Disorders Research Center, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran.

5- Research Center for Environmental Determinants of Health, Health Institute, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. & Committee Research Student, Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 2079 kb]

(668 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3118 Views)

Full-Text: (705 Views)

Introduction

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, the delivery of rehabilitation services for people with disabilities faced significant disruptions. Due to the interruptions in rehabilitation services and the increasing demand from patients and their families for rehabilitation services such as speech therapy and occupational therapy, the process of transitioning these services to virtual platforms accelerated during this period. Although virtual service delivery can be an effective option for preventing the spread of COVID-19 and can ensure the continuation of service delivery, providing such services is challenging for therapists and may also affect the effectiveness of treatments. Various studies indicated that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telehealth services increased compared to the pre-COVID period. For instance, Lee et al. in 2023 showed that while the use of telehealth services was lower than in the initial weeks of the pandemic, its level was above the pre-pandemic level. The rate of telehealth service use ranged from 20.5 to 24.2%, where 22% of adults had used telehealth services. Their results demonstrated that factors such as insurance coverage, age, place of residence, and race influenced the utilization of telehealth services [1]. Shaver, in a study in 2022 in the United States, also indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic increased the provision of telehealth services by healthcare professionals, especially physicians. The number of physicians engaged in providing telehealth services doubled in 2020 (from 20% to about 40%). The physician’s specialty influenced the extent of telehealth service delivery. Physicians who were more active in this field typically treated patients with chronic diseases, including those experts in endocrinology, gastroenterology, rheumatology, nephrology, cardiology, and psychiatry. In contrast, physicians with specialties such as dermatology, orthopedic surgery, or optometry were less likely to provide telehealth services. These physicians were mostly female, aged 40-60, and primarily resided in large urban areas [2].

In Iran, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education started to prepare the conditions for online delivery of consultations. A system was launched within the Ministry, offering telehealth services such as psychological counseling, chronic disease management, and other services to the public free of charge. One of the most significant actions by the Ministry for early detection of COVID-19 was the national electronic screening program. In the first phase of this program, more than 70 million people were screened using a self-reporting system [3]. Telehealth was introduced as a beneficial alternative for use in rural and urban areas, particularly in the “family physician” project implemented by the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Security issues were one of the challenges faced by telehealth services. Nevertheless, its benefits included reduced hospital stays and decreased morbidity and mortality rates, making it a cost-effective method. However, cultural barriers, language differences, and literacy levels were among the challenges in providing telehealth services [4].

There are limited studies on the provision of online or remote speech therapy services in Iran, and various aspects of this topic have not been fully explored. Poursaeid et al. examined the barriers and facilitators of accessing speech therapy services in Iran, and indicated that online delivery of speech therapy services prevented the interruption of treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic [5]. A study conducted in another country suggested that telehealth-delivered speech therapy services can be beneficial for children in rural areas and those with a lack of access to such services [6]. However, it requires internet infrastructure, specialist training, the existence of guidelines, and necessary hardware such as computers and smartphones [7, 8]. Some studies also suggested that telepractice services are less effective than in-person services due to environmental factors, the lack of physical interaction, ethical concerns, and the absence of therapeutic relationships [9, 10].

The advancements in information and communication technology have led to significant changes in delivering healthcare services, including speech therapy services, and have become available to patients. Assessing the impact of these services is crucial, as they can reduce geographic barriers, time constraints, and the costs of in-person visits, thereby improving access to essential treatments. Moreover, understanding the challenges and opportunities in delivering online speech therapy services can help improve the quality and efficiency of these services, ultimately leading to better treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction. Considering the paucity of studies on the advantages and disadvantages of online speech therapy services in Iran, this qualitative study aims to identify the challenges of delivering online speech therapy services from the perspective of speech-language pathologists in Iran.

Materials and Methods

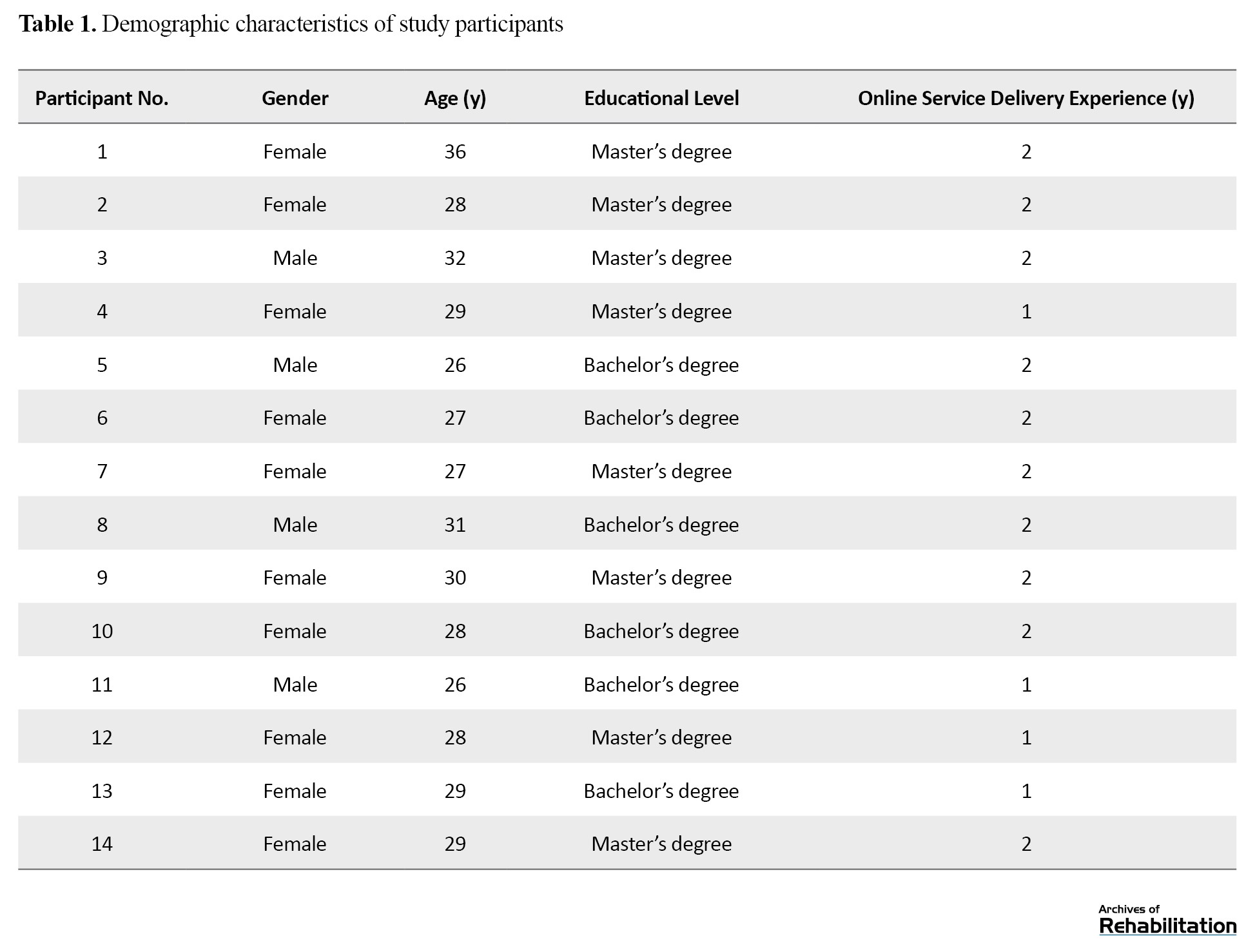

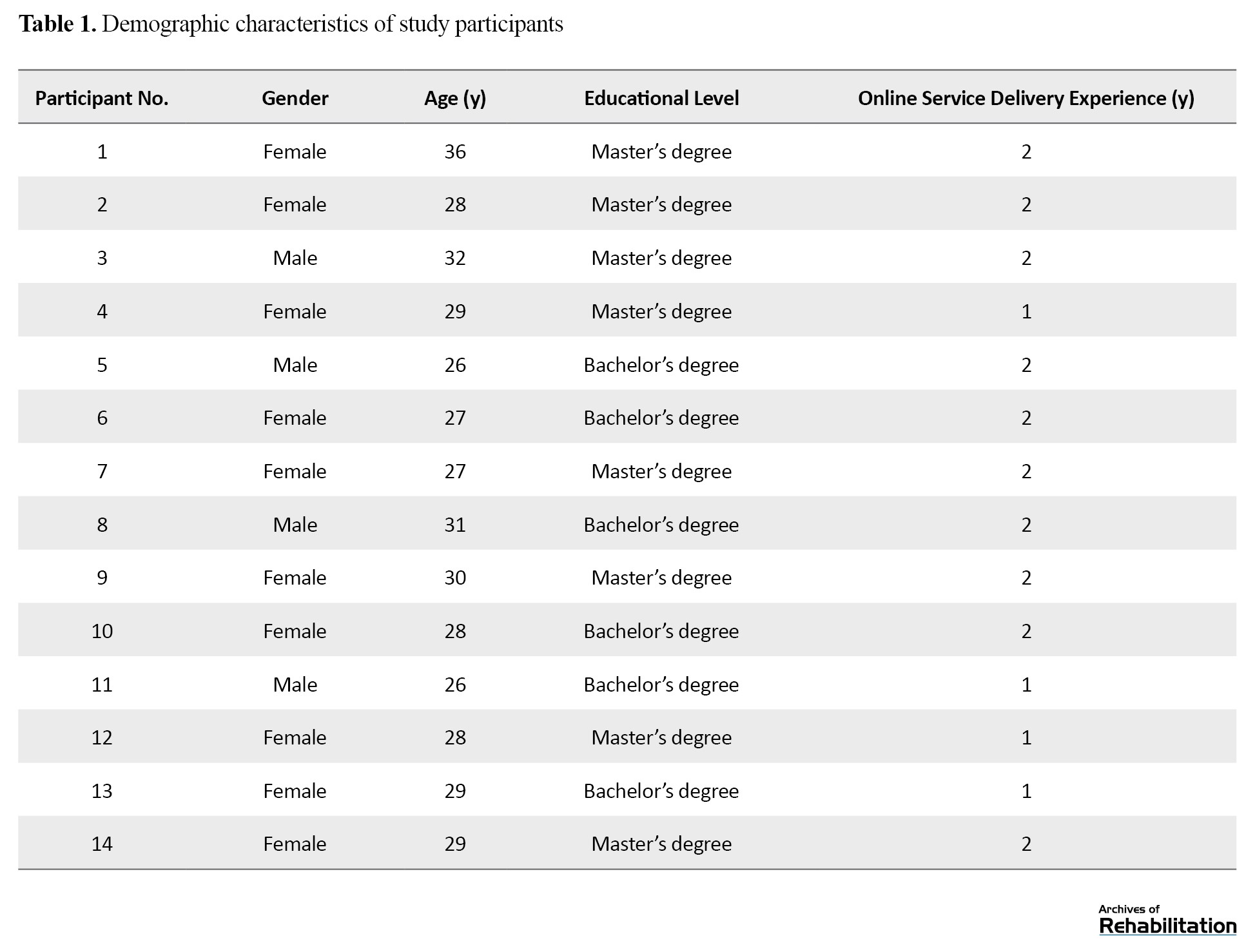

This is a qualitative study utilizing the content analysis method. The study population consisted of speech-language pathologists in Iran who offered online speech therapy services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many therapists had active Instagram accounts where they promoted their services. We sent a direct message to these therapists to invite them to participate in the study. They were asked to introduce other professionals who were also providing online speech therapy services to join the study. A total of 14 pathologists were finally selected using a snowball sampling method and based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Their demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Sampling continued until data saturation. The inclusion criteria were the provision of online speech therapy services for at least one year during the COVID-19 pandemic, Iranian nationality, and Persian speaking. Exclusion criteria were the inability to conduct voice or video calls and the unwillingness to participate in the interview.

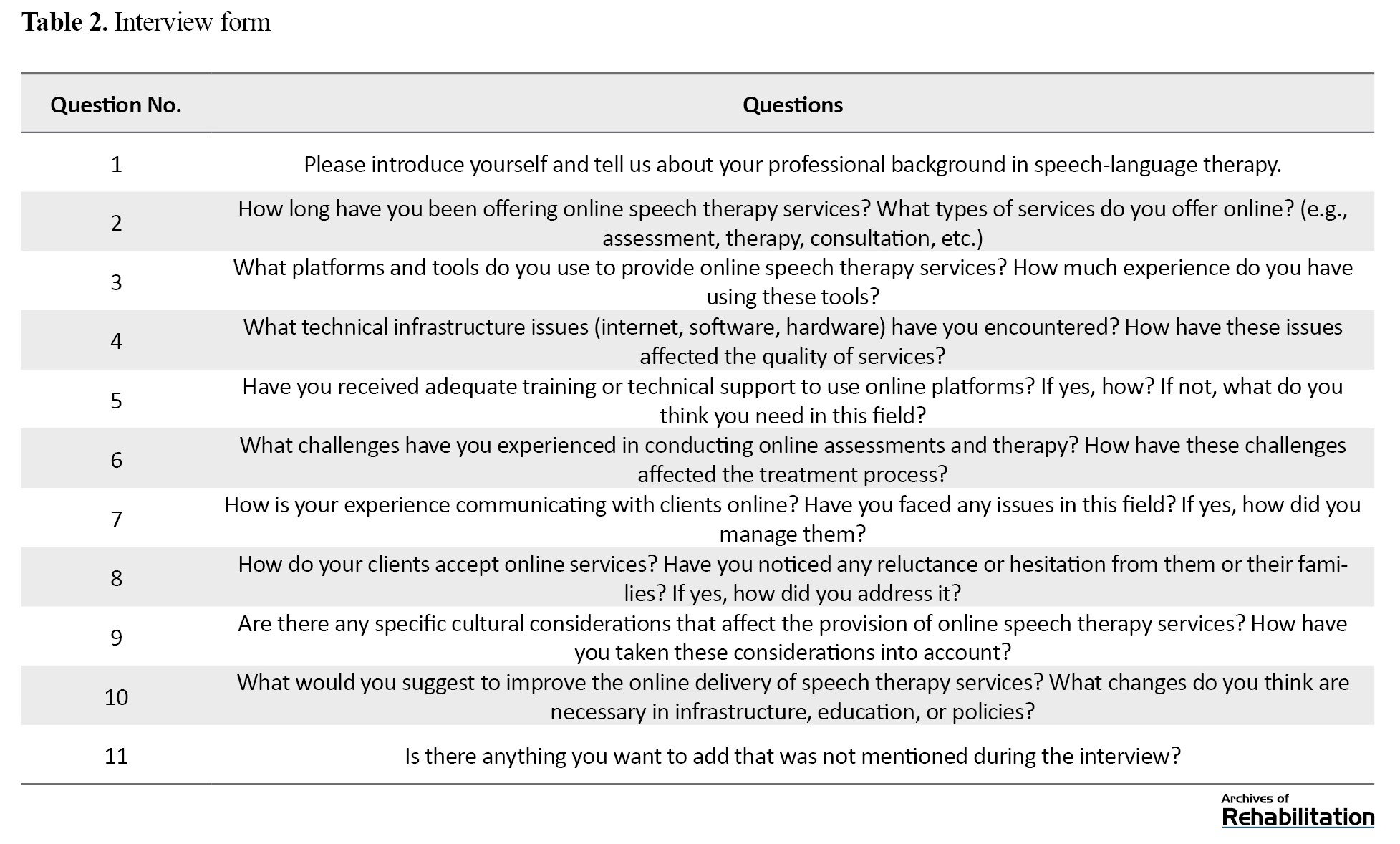

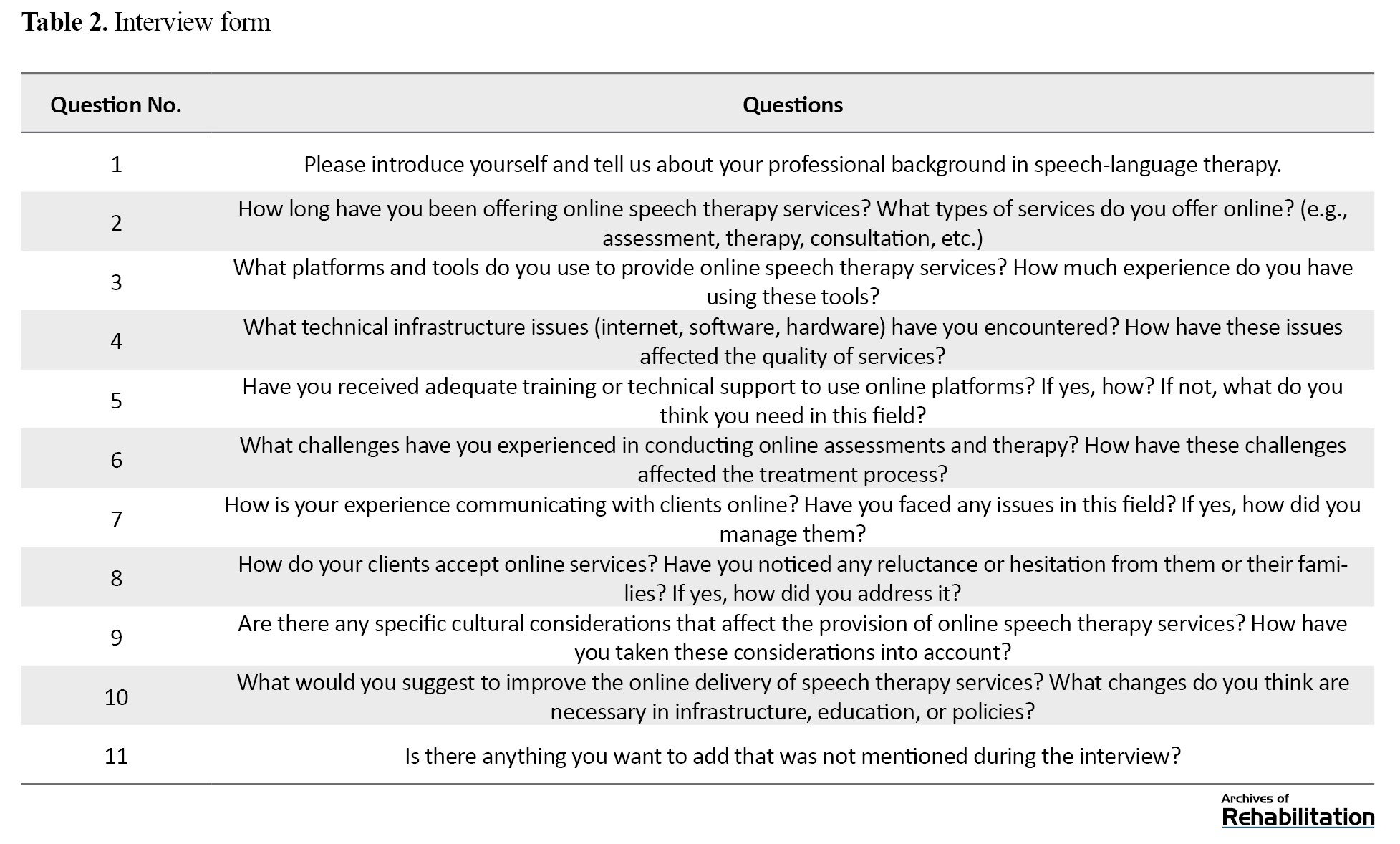

Data were collected through individual, semi-structured interviews. The interviews were conducted via voice and video calls on messaging platforms such as WhatsApp and Skype. In this regard, an interview form was designed based on the study objectives, which included several key questions and was provided to the participants (Table 2).

Data analysis was conducted using the thematic data analysis method. Coding and categorization of the data were performed in MAXQDA 2020 software. To ensure the accuracy and validity of the data, the member-checking technique was employed. The interview transcriptions and the initial emerged categories were provided to the participants. This allowed them to review the information obtained from the interview sessions, confirm their accuracy and research findings, and add any new information if necessary.

Results

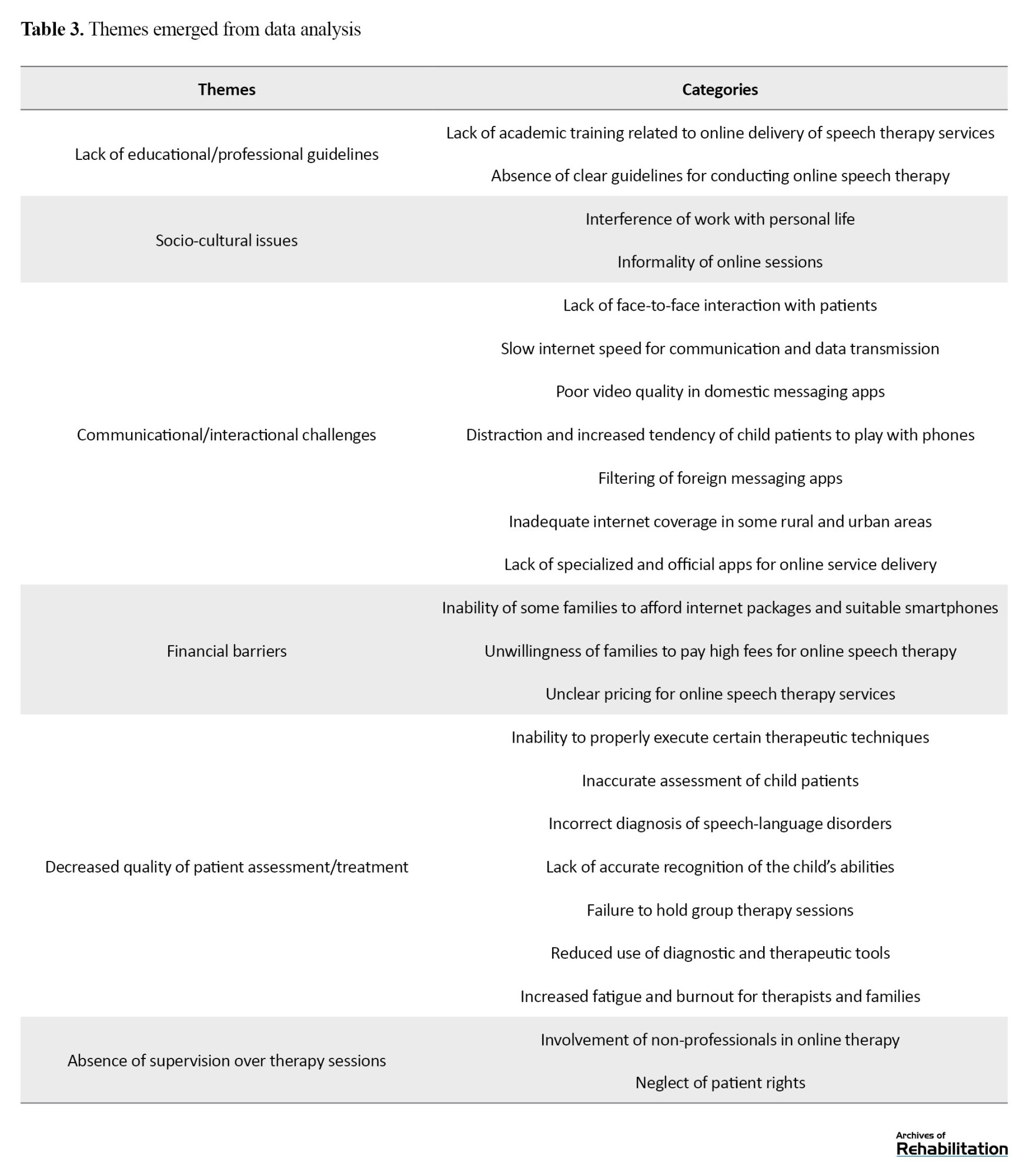

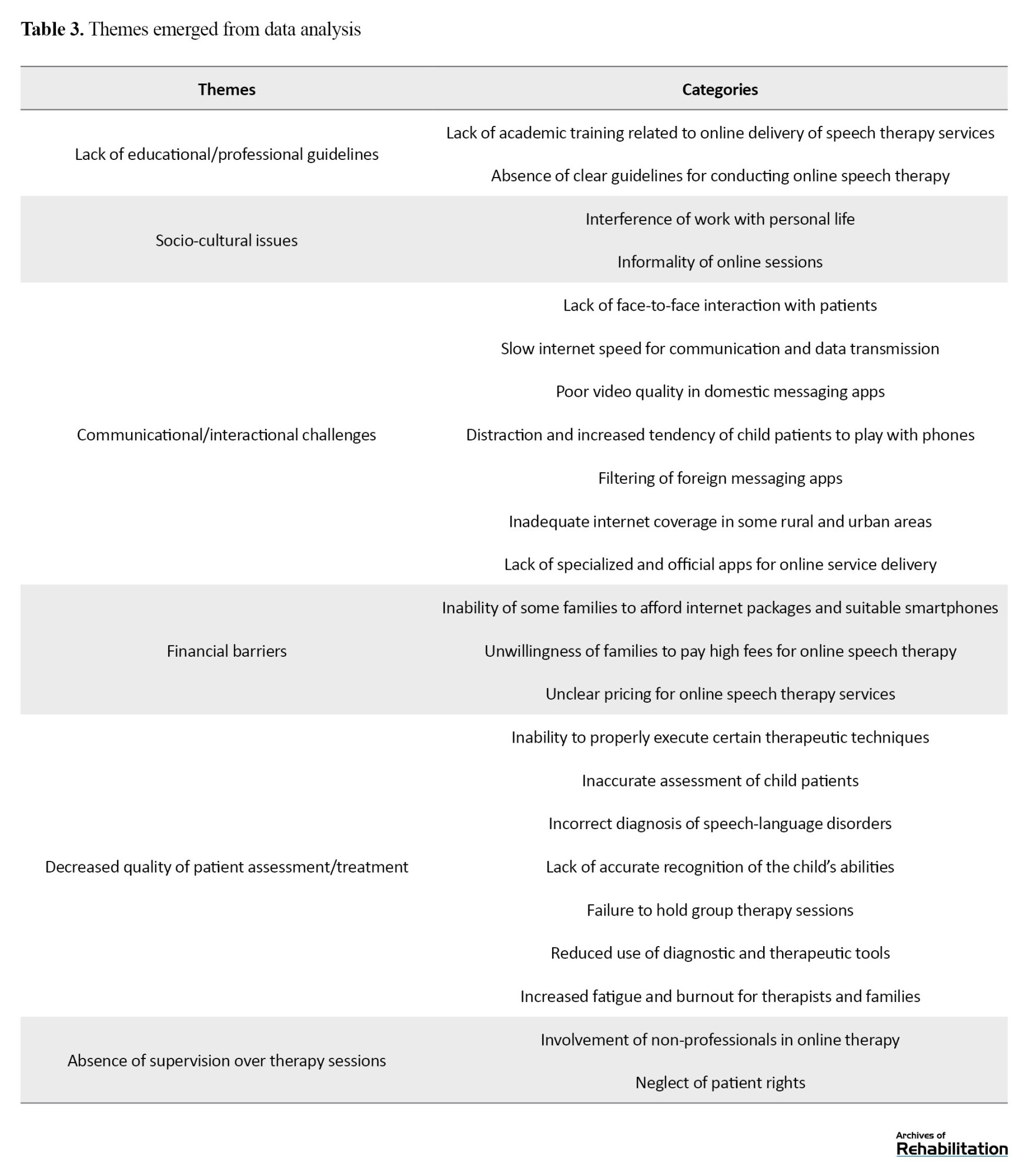

The participants included 14 speech-language pathologists (10 females and 4 males) with a mean age of 29 years. Six main themes emerged from the analysis: Lack of educational/professional guidelines, socio-cultural issues, communicational/interactional challenges, financial barriers, reduced quality of assessment/treatment, and absence of supervision over therapy sessions (Table 3).

Lack of educational/professional guidelines

The theme “lack of educational/professional guidelines” had two sub-themes: Lack of academic training related to the provision of online speech therapy services, and absence of clear guidelines for conducting online speech therapy. Participants reported that they had not received any formal education on how to deliver speech therapy services online at the university, which created challenges for them in practice. No specific guidelines had been developed for these sessions, leading to variability in conducting sessions based on personal preference and circumstances. As participant No.1 (P1) noted, “We haven’t received any training, not even a workshop. Everyone is doing it in their own ways.”

Socio-cultural issues

The theme “socio-cultural issues” also had two sub-themes: Interference of work with personal life, and informality of online sessions. Therapists mentioned that the culture of virtual communication had not fully developed among clients, leading to issues such as families calling them at inappropriate times without prior arrangement. “At 11 PM, the child’s mother called me to ask a question!” (P2). Additionally, therapists noted that the work-life interference during online sessions can disturb their concentration, negatively affecting the quality of therapy. “In online sessions, sometimes I see on camera that the father is wearing shorts or pajamas, and they don’t care about it!” (P9). Participants also expressed concerns that online sessions are less formal, potentially hindering the creation of a professional and effective therapeutic environment, which can reduce the effectiveness of the therapy.

Communicational/interactional challenges

The theme “communicational/interactional challenges” had seven sub-themes, including the lack of face-to-face interaction with patients, slow internet speed for communication and data transmission, poor video quality in Iranian apps, distraction and increased inclination of children to play with phones, filtering of foreign messaging apps, inadequate internet coverage in some rural and urban areas, and lack of specialized and official apps for online service delivery. “Some families insist on using [filtered] WhatsApp, so we have to use a VPN, which slows down the speed and quality.” (P5). Participants noted that the filtering of foreign messaging apps such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Telegram in Iran reduced the quality of audio and video calls during online sessions and disrupted the regularity of sessions. Furthermore, some clients had no trust in domestic messaging apps, leading them to use VPNs for communication. Some participants also mentioned that children often got distracted by the phone and started playing games during the session, disrupting the therapy. “For example, during the session, the child starts playing with the phone, disrupting the session!” (P6).

Financial barriers

The theme “financial barriers” had three sub-themes, including the inability of some families to afford internet packages and suitable phones, unwillingness of some families to pay high fees for online speech therapy, and unclear pricing for online speech therapy services. Participants said that some families were not financially well-off and could not even afford to buy an internet package. On the other hand, some families expected therapists to charge much less for online sessions. “[One said:] You talked only for half an hour! [Why do] you ask for more money?” (P9).

Decreased quality of patient assessment/treatment

The theme “decreased quality of patient assessment/treatment” had seven sub-themes, including inability to correctly implement certain therapeutic techniques, inaccurate assessment of children, incorrect diagnosis of speech-language disorders, lack of accurate recognition of the child’s abilities, failure to hold group therapy sessions, the use of diagnostic and therapeutic tools, and increased fatigue and burnout for therapists and families. Some therapists noted that not all therapeutic techniques could be implemented during online sessions and that it was sometimes impossible to treat certain patients online. “It depends on the child’s condition, age, and the type of disorder” (P14). Additionally, some participants mentioned that it was challenging to recognize all abilities of a child during online sessions, which can lead to improper treatment planning. Therapists also argued that online sessions increased the workload for both therapists and families. The families of patients have a higher role in managing the therapy sessions and implementing therapeutic techniques. Therapists had to design more and different exercises for clients during online sessions. “The number of exercises in online sessions needs to be high and varied, and you need to be more creative” (P12).

Lack of supervision over therapy sessions

The final theme, “lack of supervision over therapy sessions,” had two sub-themes: Involvement of non-professionals in online therapy, and neglect of patient rights. Some therapists reported that due to the lack of supervision over these sessions, families were being exploited, and individuals who were not even certified therapists were offering speech therapy services. “There are high exploitations nowadays, and people who aren’t even speech therapists are offering stuttering treatment services and charging high fees for online sessions!” (P7).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify the barriers to providing online speech therapy services in Iran, where interviews were conducted with 14 speech-language pathologists. They highlighted significant barriers, including communicational/interactional challenges such as filtering foreign messaging apps and poor internet quality. Communication infrastructure, the internet, and messaging apps can significantly impact the quality of online speech therapy services in Iran. Contacting therapists at inappropriate times can also disrupt the speech-language treatment process, leading to their reduced commitment to the therapy sessions. This challenge can result in reduced emotional connection and direct interaction between therapists and patients, hindering effective therapy delivery. Distractions and children’s playing with the phone can also lead to reduced concentration and active participation in therapy sessions.

Chaudhary et al., in a study in India compared the outcomes of face-to-face and teletherapy for speech/language disorders in 20 patients with psychogenic disorders, voice disorders, swallowing disorders, and neurological disorders. Their findings indicated that, after completing the therapy courses, 4 patients chose face-to-face therapy as their preferred method, while 16 preferred tele-therapy. Except for 3 patients who rated their overall satisfaction as 3, the rest gave a score of 4 or 5. Moreover, the therapists were satisfied with the therapy outcomes in 17 cases and were pleased with the overall progress of all patients (scored 4 or 5). The authors suggested that tele-therapy is a reliable and high-quality method for providing speech-language services in the long term [11]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the cessation of face-to-face speech-language therapies affected the patients (especially children) and their families physically, socially, psychologically, and most importantly, economically [12]. For families living in rural or medically underserved areas who have access to the internet and apps, telehealth can facilitate their access to medical services. Telehealth during the pandemic offered an opportunity to deliver timely, patient- and family-centered rehabilitation services while maintaining social distancing and reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission [13]. In a review study by Guglani et al. in 2023, the effectiveness of telepractice for speech-language therapy for patients with voice disorders during the pandemic was examined. It was shown that satisfaction with these services was higher in women than in men, as women could schedule their therapy sessions at home and easily manage household chores. Telepractice also had benefits such as easy access to care, increased convenience, reduced travel costs, and enhanced privacy. The patients sought to continue receiving these sessions even after the pandemic [14]. Given the need for continuous therapy sessions to treat speech-language disorders, the use of telehealth for speech-language therapy may solve some challenges in this field while preventing the spread of COVID-19 [13]. Nakarmi et al. examined the effects of online speech therapy during the pandemic for patients with cleft palate in rural areas of Nepal and found that the most important strengths of online speech therapy were the proper use of time, ability to use audiovisual aids, elimination of travel constraints, and quick progress. The most common challenges were internet disconnection, unclear voice, lack of direct interaction, and unstable internet sources. The strategies to improve online speech therapy were better internet connectivity, a fixed schedule, and utilizing free or affordable Wi-Fi [15]. A study by Chang et al. in South Korea showed that the video-call speech therapy method was as effective as the face-to-face method for patients with Parkinson’s disease and could be effective in treating speech-language disorders [16]. The studies have indicated that online sessions can have significant benefits such as time savings for both the therapist and the patient, reduced costs associated with frequent in-person visits to the therapist, reduced spread of infectious diseases, and the ability to receive services for patients who are unable to visit the therapist [17, 18]. Shahouzaie and Gholamiyan indicated that the reduced access to in-person rehabilitative care during the COVID-19 pandemic, along with changes in healthcare finance, contributed to an exponential increase in telehealth. According to them, beyond infection control, eliminating travel time and providing convenient services in familiar environments to pediatric patients are all benefits of telehealth in speech-language therapy even after the pandemic [13].

In general, multiple measures should be taken in various areas to facilitate telehealth for speech-language therapy in Iran. First, special attention should be paid to improving technical infrastructure. Proper planning and investment in developing digital infrastructure play an important role in ensuring the success of this method. Access to stable and high-speed internet in all parts of the country should also be facilitated, especially in rural and less developed areas. Without proper internet speed, conducting high-quality and uninterrupted online sessions will not be possible. In addition, using or developing efficient apps for conducting speech-language sessions is highly important. These apps should be able to handle a high number of users while having advanced security to protect their information. User education and empowerment are also important. Appropriate training should be provided to users on how to use online platforms and apps. The use of strong technical support systems that can quickly identify and solve technical issues can also help enhance telehealth for speech-language therapy. Policy-making and the formulation of laws related to user privacy and information security are also important. These laws should ensure the protection of users’ personal information in virtual environments. Providing financial facilities to equip speech-language therapists with the necessary online tools to offer online services, especially for low-income people, is another necessary measure. Equal access to the internet and apps should be provided to those living in rural areas and vulnerable groups, such as older adults and people with disabilities. Finally, the intersectoral collaborations between governmental and private organizations, as well as continuous monitoring and assessment of the performance of apps and platforms, are essential for improving the process of online speech-language therapy and ensuring that the services have the highest quality.

The limitations of the present study included the non-cooperation of some participants due to being busy at work and the unwillingness of some participants to have video calling. Some participants were identified on the Instagram, and others were included by snowball sampling. Therefore, it is possible that some age groups and residents of other provinces in Iran were not included. It should also be noted that due to the wide range of specialized fields in speech-language pathology (swallowing and cleft/palate disorders, hearing impairment, speech production, fluency, etc.), this study could not include participants from all specialized fields. Therefore, the included therapists might have different experiences in providing online speech therapy services. Further studies are recommended by considering the specialty and experiences of speech-language pathologists in Iran.

Conclusion

Various structural, professional, cultural, and ethical barriers can affect the provision of online speech-language therapy services in Iran. Providing related educational materials in medical universities, developing necessary guidelines to ensure the rights of therapists and patients, creating specialized and efficient applications with appropriate quality, and establishing the necessary infrastructure by policymakers can facilitate the utilization of telehealth methods for speech-language therapy in Iran.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iarn (Code: IR.KUMS.REC.1400.222). The content of the interviews was kept confidential, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding

This research was funded by Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iarn.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and writing the initial draft: Shahin Soltani and Amir Shiani; Methodology: Shahin Soltani and Behzad Karami Matin; Data analysis: Fardin Moradi; Review and editing: All authors; Supervision: Behzad Karami Matin; Project administration: Shahin Soltani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran, for financial support, and all the pathologists who participated in the study for their cooperation.

References

Following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, the delivery of rehabilitation services for people with disabilities faced significant disruptions. Due to the interruptions in rehabilitation services and the increasing demand from patients and their families for rehabilitation services such as speech therapy and occupational therapy, the process of transitioning these services to virtual platforms accelerated during this period. Although virtual service delivery can be an effective option for preventing the spread of COVID-19 and can ensure the continuation of service delivery, providing such services is challenging for therapists and may also affect the effectiveness of treatments. Various studies indicated that during the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of telehealth services increased compared to the pre-COVID period. For instance, Lee et al. in 2023 showed that while the use of telehealth services was lower than in the initial weeks of the pandemic, its level was above the pre-pandemic level. The rate of telehealth service use ranged from 20.5 to 24.2%, where 22% of adults had used telehealth services. Their results demonstrated that factors such as insurance coverage, age, place of residence, and race influenced the utilization of telehealth services [1]. Shaver, in a study in 2022 in the United States, also indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic increased the provision of telehealth services by healthcare professionals, especially physicians. The number of physicians engaged in providing telehealth services doubled in 2020 (from 20% to about 40%). The physician’s specialty influenced the extent of telehealth service delivery. Physicians who were more active in this field typically treated patients with chronic diseases, including those experts in endocrinology, gastroenterology, rheumatology, nephrology, cardiology, and psychiatry. In contrast, physicians with specialties such as dermatology, orthopedic surgery, or optometry were less likely to provide telehealth services. These physicians were mostly female, aged 40-60, and primarily resided in large urban areas [2].

In Iran, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Health and Medical Education started to prepare the conditions for online delivery of consultations. A system was launched within the Ministry, offering telehealth services such as psychological counseling, chronic disease management, and other services to the public free of charge. One of the most significant actions by the Ministry for early detection of COVID-19 was the national electronic screening program. In the first phase of this program, more than 70 million people were screened using a self-reporting system [3]. Telehealth was introduced as a beneficial alternative for use in rural and urban areas, particularly in the “family physician” project implemented by the Iranian Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Security issues were one of the challenges faced by telehealth services. Nevertheless, its benefits included reduced hospital stays and decreased morbidity and mortality rates, making it a cost-effective method. However, cultural barriers, language differences, and literacy levels were among the challenges in providing telehealth services [4].

There are limited studies on the provision of online or remote speech therapy services in Iran, and various aspects of this topic have not been fully explored. Poursaeid et al. examined the barriers and facilitators of accessing speech therapy services in Iran, and indicated that online delivery of speech therapy services prevented the interruption of treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic [5]. A study conducted in another country suggested that telehealth-delivered speech therapy services can be beneficial for children in rural areas and those with a lack of access to such services [6]. However, it requires internet infrastructure, specialist training, the existence of guidelines, and necessary hardware such as computers and smartphones [7, 8]. Some studies also suggested that telepractice services are less effective than in-person services due to environmental factors, the lack of physical interaction, ethical concerns, and the absence of therapeutic relationships [9, 10].

The advancements in information and communication technology have led to significant changes in delivering healthcare services, including speech therapy services, and have become available to patients. Assessing the impact of these services is crucial, as they can reduce geographic barriers, time constraints, and the costs of in-person visits, thereby improving access to essential treatments. Moreover, understanding the challenges and opportunities in delivering online speech therapy services can help improve the quality and efficiency of these services, ultimately leading to better treatment outcomes and patient satisfaction. Considering the paucity of studies on the advantages and disadvantages of online speech therapy services in Iran, this qualitative study aims to identify the challenges of delivering online speech therapy services from the perspective of speech-language pathologists in Iran.

Materials and Methods

This is a qualitative study utilizing the content analysis method. The study population consisted of speech-language pathologists in Iran who offered online speech therapy services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many therapists had active Instagram accounts where they promoted their services. We sent a direct message to these therapists to invite them to participate in the study. They were asked to introduce other professionals who were also providing online speech therapy services to join the study. A total of 14 pathologists were finally selected using a snowball sampling method and based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Their demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Sampling continued until data saturation. The inclusion criteria were the provision of online speech therapy services for at least one year during the COVID-19 pandemic, Iranian nationality, and Persian speaking. Exclusion criteria were the inability to conduct voice or video calls and the unwillingness to participate in the interview.

Data were collected through individual, semi-structured interviews. The interviews were conducted via voice and video calls on messaging platforms such as WhatsApp and Skype. In this regard, an interview form was designed based on the study objectives, which included several key questions and was provided to the participants (Table 2).

Data analysis was conducted using the thematic data analysis method. Coding and categorization of the data were performed in MAXQDA 2020 software. To ensure the accuracy and validity of the data, the member-checking technique was employed. The interview transcriptions and the initial emerged categories were provided to the participants. This allowed them to review the information obtained from the interview sessions, confirm their accuracy and research findings, and add any new information if necessary.

Results

The participants included 14 speech-language pathologists (10 females and 4 males) with a mean age of 29 years. Six main themes emerged from the analysis: Lack of educational/professional guidelines, socio-cultural issues, communicational/interactional challenges, financial barriers, reduced quality of assessment/treatment, and absence of supervision over therapy sessions (Table 3).

Lack of educational/professional guidelines

The theme “lack of educational/professional guidelines” had two sub-themes: Lack of academic training related to the provision of online speech therapy services, and absence of clear guidelines for conducting online speech therapy. Participants reported that they had not received any formal education on how to deliver speech therapy services online at the university, which created challenges for them in practice. No specific guidelines had been developed for these sessions, leading to variability in conducting sessions based on personal preference and circumstances. As participant No.1 (P1) noted, “We haven’t received any training, not even a workshop. Everyone is doing it in their own ways.”

Socio-cultural issues

The theme “socio-cultural issues” also had two sub-themes: Interference of work with personal life, and informality of online sessions. Therapists mentioned that the culture of virtual communication had not fully developed among clients, leading to issues such as families calling them at inappropriate times without prior arrangement. “At 11 PM, the child’s mother called me to ask a question!” (P2). Additionally, therapists noted that the work-life interference during online sessions can disturb their concentration, negatively affecting the quality of therapy. “In online sessions, sometimes I see on camera that the father is wearing shorts or pajamas, and they don’t care about it!” (P9). Participants also expressed concerns that online sessions are less formal, potentially hindering the creation of a professional and effective therapeutic environment, which can reduce the effectiveness of the therapy.

Communicational/interactional challenges

The theme “communicational/interactional challenges” had seven sub-themes, including the lack of face-to-face interaction with patients, slow internet speed for communication and data transmission, poor video quality in Iranian apps, distraction and increased inclination of children to play with phones, filtering of foreign messaging apps, inadequate internet coverage in some rural and urban areas, and lack of specialized and official apps for online service delivery. “Some families insist on using [filtered] WhatsApp, so we have to use a VPN, which slows down the speed and quality.” (P5). Participants noted that the filtering of foreign messaging apps such as WhatsApp, Instagram, and Telegram in Iran reduced the quality of audio and video calls during online sessions and disrupted the regularity of sessions. Furthermore, some clients had no trust in domestic messaging apps, leading them to use VPNs for communication. Some participants also mentioned that children often got distracted by the phone and started playing games during the session, disrupting the therapy. “For example, during the session, the child starts playing with the phone, disrupting the session!” (P6).

Financial barriers

The theme “financial barriers” had three sub-themes, including the inability of some families to afford internet packages and suitable phones, unwillingness of some families to pay high fees for online speech therapy, and unclear pricing for online speech therapy services. Participants said that some families were not financially well-off and could not even afford to buy an internet package. On the other hand, some families expected therapists to charge much less for online sessions. “[One said:] You talked only for half an hour! [Why do] you ask for more money?” (P9).

Decreased quality of patient assessment/treatment

The theme “decreased quality of patient assessment/treatment” had seven sub-themes, including inability to correctly implement certain therapeutic techniques, inaccurate assessment of children, incorrect diagnosis of speech-language disorders, lack of accurate recognition of the child’s abilities, failure to hold group therapy sessions, the use of diagnostic and therapeutic tools, and increased fatigue and burnout for therapists and families. Some therapists noted that not all therapeutic techniques could be implemented during online sessions and that it was sometimes impossible to treat certain patients online. “It depends on the child’s condition, age, and the type of disorder” (P14). Additionally, some participants mentioned that it was challenging to recognize all abilities of a child during online sessions, which can lead to improper treatment planning. Therapists also argued that online sessions increased the workload for both therapists and families. The families of patients have a higher role in managing the therapy sessions and implementing therapeutic techniques. Therapists had to design more and different exercises for clients during online sessions. “The number of exercises in online sessions needs to be high and varied, and you need to be more creative” (P12).

Lack of supervision over therapy sessions

The final theme, “lack of supervision over therapy sessions,” had two sub-themes: Involvement of non-professionals in online therapy, and neglect of patient rights. Some therapists reported that due to the lack of supervision over these sessions, families were being exploited, and individuals who were not even certified therapists were offering speech therapy services. “There are high exploitations nowadays, and people who aren’t even speech therapists are offering stuttering treatment services and charging high fees for online sessions!” (P7).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify the barriers to providing online speech therapy services in Iran, where interviews were conducted with 14 speech-language pathologists. They highlighted significant barriers, including communicational/interactional challenges such as filtering foreign messaging apps and poor internet quality. Communication infrastructure, the internet, and messaging apps can significantly impact the quality of online speech therapy services in Iran. Contacting therapists at inappropriate times can also disrupt the speech-language treatment process, leading to their reduced commitment to the therapy sessions. This challenge can result in reduced emotional connection and direct interaction between therapists and patients, hindering effective therapy delivery. Distractions and children’s playing with the phone can also lead to reduced concentration and active participation in therapy sessions.

Chaudhary et al., in a study in India compared the outcomes of face-to-face and teletherapy for speech/language disorders in 20 patients with psychogenic disorders, voice disorders, swallowing disorders, and neurological disorders. Their findings indicated that, after completing the therapy courses, 4 patients chose face-to-face therapy as their preferred method, while 16 preferred tele-therapy. Except for 3 patients who rated their overall satisfaction as 3, the rest gave a score of 4 or 5. Moreover, the therapists were satisfied with the therapy outcomes in 17 cases and were pleased with the overall progress of all patients (scored 4 or 5). The authors suggested that tele-therapy is a reliable and high-quality method for providing speech-language services in the long term [11]. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the cessation of face-to-face speech-language therapies affected the patients (especially children) and their families physically, socially, psychologically, and most importantly, economically [12]. For families living in rural or medically underserved areas who have access to the internet and apps, telehealth can facilitate their access to medical services. Telehealth during the pandemic offered an opportunity to deliver timely, patient- and family-centered rehabilitation services while maintaining social distancing and reducing the risk of COVID-19 transmission [13]. In a review study by Guglani et al. in 2023, the effectiveness of telepractice for speech-language therapy for patients with voice disorders during the pandemic was examined. It was shown that satisfaction with these services was higher in women than in men, as women could schedule their therapy sessions at home and easily manage household chores. Telepractice also had benefits such as easy access to care, increased convenience, reduced travel costs, and enhanced privacy. The patients sought to continue receiving these sessions even after the pandemic [14]. Given the need for continuous therapy sessions to treat speech-language disorders, the use of telehealth for speech-language therapy may solve some challenges in this field while preventing the spread of COVID-19 [13]. Nakarmi et al. examined the effects of online speech therapy during the pandemic for patients with cleft palate in rural areas of Nepal and found that the most important strengths of online speech therapy were the proper use of time, ability to use audiovisual aids, elimination of travel constraints, and quick progress. The most common challenges were internet disconnection, unclear voice, lack of direct interaction, and unstable internet sources. The strategies to improve online speech therapy were better internet connectivity, a fixed schedule, and utilizing free or affordable Wi-Fi [15]. A study by Chang et al. in South Korea showed that the video-call speech therapy method was as effective as the face-to-face method for patients with Parkinson’s disease and could be effective in treating speech-language disorders [16]. The studies have indicated that online sessions can have significant benefits such as time savings for both the therapist and the patient, reduced costs associated with frequent in-person visits to the therapist, reduced spread of infectious diseases, and the ability to receive services for patients who are unable to visit the therapist [17, 18]. Shahouzaie and Gholamiyan indicated that the reduced access to in-person rehabilitative care during the COVID-19 pandemic, along with changes in healthcare finance, contributed to an exponential increase in telehealth. According to them, beyond infection control, eliminating travel time and providing convenient services in familiar environments to pediatric patients are all benefits of telehealth in speech-language therapy even after the pandemic [13].

In general, multiple measures should be taken in various areas to facilitate telehealth for speech-language therapy in Iran. First, special attention should be paid to improving technical infrastructure. Proper planning and investment in developing digital infrastructure play an important role in ensuring the success of this method. Access to stable and high-speed internet in all parts of the country should also be facilitated, especially in rural and less developed areas. Without proper internet speed, conducting high-quality and uninterrupted online sessions will not be possible. In addition, using or developing efficient apps for conducting speech-language sessions is highly important. These apps should be able to handle a high number of users while having advanced security to protect their information. User education and empowerment are also important. Appropriate training should be provided to users on how to use online platforms and apps. The use of strong technical support systems that can quickly identify and solve technical issues can also help enhance telehealth for speech-language therapy. Policy-making and the formulation of laws related to user privacy and information security are also important. These laws should ensure the protection of users’ personal information in virtual environments. Providing financial facilities to equip speech-language therapists with the necessary online tools to offer online services, especially for low-income people, is another necessary measure. Equal access to the internet and apps should be provided to those living in rural areas and vulnerable groups, such as older adults and people with disabilities. Finally, the intersectoral collaborations between governmental and private organizations, as well as continuous monitoring and assessment of the performance of apps and platforms, are essential for improving the process of online speech-language therapy and ensuring that the services have the highest quality.

The limitations of the present study included the non-cooperation of some participants due to being busy at work and the unwillingness of some participants to have video calling. Some participants were identified on the Instagram, and others were included by snowball sampling. Therefore, it is possible that some age groups and residents of other provinces in Iran were not included. It should also be noted that due to the wide range of specialized fields in speech-language pathology (swallowing and cleft/palate disorders, hearing impairment, speech production, fluency, etc.), this study could not include participants from all specialized fields. Therefore, the included therapists might have different experiences in providing online speech therapy services. Further studies are recommended by considering the specialty and experiences of speech-language pathologists in Iran.

Conclusion

Various structural, professional, cultural, and ethical barriers can affect the provision of online speech-language therapy services in Iran. Providing related educational materials in medical universities, developing necessary guidelines to ensure the rights of therapists and patients, creating specialized and efficient applications with appropriate quality, and establishing the necessary infrastructure by policymakers can facilitate the utilization of telehealth methods for speech-language therapy in Iran.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iarn (Code: IR.KUMS.REC.1400.222). The content of the interviews was kept confidential, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Funding

This research was funded by Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iarn.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and writing the initial draft: Shahin Soltani and Amir Shiani; Methodology: Shahin Soltani and Behzad Karami Matin; Data analysis: Fardin Moradi; Review and editing: All authors; Supervision: Behzad Karami Matin; Project administration: Shahin Soltani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Vice-Chancellor for Research and Technology of Kermanshah University of Medical Sciences, Kermanshah, Iran, for financial support, and all the pathologists who participated in the study for their cooperation.

References

- Lee EC, Grigorescu V, Enogieru I, Smith SR, Samson LW, Conmy AB, et al. Updated national survey trends in telehealth utilization and modality (2021-2022). Washington (DC): Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE); 2023. [Link]

- Shaver J. The State of Telehealth Before and After the COVID-19 Pandemic. Primary Care. 2022; 49(4):517-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.pop.2022.04.002] [PMID]

- Hajizadeh A, Monaghesh E. Telehealth services support community during the COVID-19 outbreak in Iran: Activities of Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Informatics in Medicine Unlocked. 2021; 24:100567. [DOI:10.1016/j.imu.2021.100567] [PMID]

- Salehahmadi Z, Hajialiasghari F. Telemedicine in iran: Chances and challenges. World Journal of Plastic Surgery. 2013; 2(1):18-25. [PMID]

- Poursaeid Z, Mohsenpour M, Ghasisin L. [The experiences of the families of people with Aphasia about the barriers and facilitators of receiving speech therapy services in Iran. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2023; 24(2):150-71. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.24.2.141.3]

- Wales D, Skinner L, Hayman M. The efficacy of telehealth-delivered speech and language intervention for primary school-age children: A systematic review. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2017; 9(1):55-70. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2017.6219] [PMID]

- Isaki E, Fangman Farrell C. Provision of speech-language pathology telepractice services using Apple iPads. Telemedicine Journal and e-Health : The Official Journal of the American Telemedicine Association. 2015; 21(7):538-49. [DOI:10.1089/tmj.2014.0153] [PMID]

- Tucker JK. Perspectives of speech-language pathologists on the use of telepractice in schools: The qualitative view. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2012; 4(2):47-60. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2012.6102] [PMID]

- Hines M, Lincoln M, Ramsden R, Martinovich J, Fairweather C. Speech pathologists’ perspectives on transitioning to telepractice: What factors promote acceptance? Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2015; 21(8):469-73. [DOI:10.1177/1357633X15604555] [PMID]

- Mohan HS, Anjum A, Rao PKS. A survey of telepractice in speech-language pathology and audiology in India. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2017; 9(2):69-80. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2017.6233] [PMID]

- Chaudhary T, Kanodia A, Verma H, Singh CA, Mishra AK, Sikka K. A pilot study comparing teletherapy with the conventional face-to-face therapy for speech-language disorders. Indian Journal of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery. 2021; 73(3):366-70. [DOI:10.1007/s12070-021-02647-0] [PMID]

- Tohidast SA, Mansuri B, Bagheri R, Azimi H. Provision of speech-language pathology services for the treatment of speech and language disorders in children during the COVID-19 pandemic: Problems, concerns, and solutions. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2020; 138:110262. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110262] [PMID]

- Shahouzaie N, Gholamiyan Arefi M. Telehealth in speech and language therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Disability and Rehabilitation. Assistive Technology. 2024; 19(3):761-8. [DOI:10.1080/17483107.2022.2122605] [PMID]

- Guglani I, Sanskriti S, Joshi SH, Anjankar A. Speech-Language therapy through telepractice during covid-19 and its way forward: A scoping review. Cureus. 2023; 15(9):e44808. [DOI:10.7759/cureus.44808] [PMID]

- Nakarmi KK, Mehta K, Shakya P, Rai SK, Bhattarai Gurung K, Koirala R, et al. Online speech therapy for cleft palate patients in rural Nepal: Innovations in providing essential care during covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Nepal Health Research Council. 2022; 20(1):154-9. [DOI:10.33314/jnhrc.v20i01.3781] [PMID]

- Chang HJ, Kim J, Joo JY, Kim HJ. Feasibility and efficacy of video-call speech therapy in patients with Parkinson’s disease: A preliminary study. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders. 2023; 114:105772. [DOI:10.1016/j.parkreldis.2023.105772] [PMID]

- Ansarian M, Baharlouei Z. Applications and challenges of telemedicine: Privacy-preservation as a case study. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2023; 26(11):654-61. [DOI:10.34172/aim.2023.96] [PMID]

- Shamsabadi A, Qaderi K, Mirzapour P, Mojdeganlou H, Mojdeganlou P, Pashaei Z, et al. Telehealth systems for midwifery care management during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Iranian Medical Council. 2023; 6(2):240-50.

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Rehabilitation Management

Received: 9/04/2024 | Accepted: 22/09/2024 | Published: 1/04/2025

Received: 9/04/2024 | Accepted: 22/09/2024 | Published: 1/04/2025

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |