Volume 25, Issue 2 (Summer 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(2): 208-231 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Tajik Z, Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi M, Posht Mashhadi M, Bidhendi Yarandi R. Investigating the Effectiveness of Cogniplus Cognitive Training Program on Social Cognition (Theory of Mind) in 6- to 8-year-old Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder. jrehab 2024; 25 (2) :208-231

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3406-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3406-en.html

Zahra Tajik1

, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi *2

, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi *2

, Marjan Posht Mashhadi3

, Marjan Posht Mashhadi3

, Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi4

, Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi4

, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi *2

, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi *2

, Marjan Posht Mashhadi3

, Marjan Posht Mashhadi3

, Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi4

, Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi4

1- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,mpmrtajrishi@gmail.com

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Cognitive training, Social cognition, Theory of mind (ToM)

Full-Text [PDF 2530 kb]

(1719 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6528 Views)

Full-Text: (2282 Views)

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is classified as a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairments in communication, and social interaction, and the presence of repetitive and restricted behavioral patterns. These hallmark symptoms manifest early in childhood and can significantly impede daily functioning. As of 2023, the reported prevalence rate of ASD in children stands at 1 per 36 births [1]. In Iran, the prevalence of this disorder has been documented at 6.26 per 10,000 [2].

One of the crucial components of communication and interaction is social cognition. Social cognition encompasses all the skills necessary for children to comprehend desires, emotions, and feelings [3], serving as a mechanism to interpret and process societal cues and align them with an individual’s internal physiological state. This process elicits a behavioral response that is appropriate to a given situation [4]. The development of social cognition commences in the early stages of life, with infants’ observation of how individuals react to social stimuli and occurrences serving as the foundation for the advancement and comprehension of social cognition. Furthermore, the development of social cognition is a product of the development of the theory of mind (ToM) [4]. ToM refers to the capacity to comprehend the thoughts and emotions of others and comprises the following three levels. The initial ToM (first level) which entails the identification of emotions. The realistic ToM (second level) involves the recognition that individuals’ beliefs or mental states can diverge, even when some of these beliefs are not in alignment with reality. The advanced ToM (third level) which signifies that individuals may occasionally hold incorrect and mistaken notions about others’ beliefs. Additionally, it denotes an individual’s proficiency in making informal declarations like joking, teasing, and deceiving [5]. Deficiencies in these factors are linked to challenges in comprehending the self and others’ thoughts, desires, and emotions, resulting in a failure to establish effective communication structures with others and impacting the quality of a child’s life [6]. The social impairments seen in children with ASD are partly attributed to deficits in ToM [7, 8]. The absence or impairment of social cognition influences social interactions, relationships, educational and occupational settings, and overall independent living [8].

Playing as a component of educational and rehabilitative interventions is consistently regarded as a beneficial approach to enhancing and refining the social cognition of children with ASD [9]. The efficacy of physical and movement games [8], cognitive games [9], and social games [10] in ameliorating the symptoms of ASD has been substantiated. Among the various games utilized today, digital and computer-based games are prevalent. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation through computer games in enhancing ToM [11], mitigating behavioral issues, enhancing ToM [12], and improving skills and social performance [13] in children with ASD. Due to the visual presentation of information in computer-based games, they hold an appeal for children with ASD [10]. Computer-based games exhibit significant potential in the realm of special education, serving as tools for assessing autism-related challenges and as valuable resources for therapeutic and educational purposes. Given that children with autism may experience confusion and tension in traditional educational and therapeutic settings, they often miss out on learning opportunities. Engaging in computer-based games offers them a controlled educational environment conducive to learning [14]. These games can enhance social skills by bolstering essential cognitive abilities such as attention, memory, and motivation [3]. Because of children’s limited interest in conventional cognitive approaches [8] and the beneficial impact of cognitive software on the cognitive capabilities of individuals with ASD [15], there is a growing trend toward utilizing digitally presented cognitive training programs, some of which are referred to as cognitive rehabilitation programs.

Cognitive rehabilitation, as explored in current research, involves a computer-based approach that relies on the fundamental information processing system. It offers feedback on an individual’s abilities and self-efficacy, tailoring educational programs to match the individual’s skill set. This intervention method begins by enhancing basic skills, gradually increasing the complexity of exercises. Progress reports on the individual’s performance in these exercises are shared with therapists, enabling them to assist individuals in enhancing crucial mental processes essential for advanced learning [16]. The exercises within cognitive training programs aim to enhance cognitive functions related to sustained concentration, response inhibition, visual and auditory processing, reading, and memory [17].

Given the rising prevalence of ASD globally and in Iran, along with growing concerns regarding social interaction and cognition challenges faced by these children, there is a pressing need to focus on programs tailored to address the specific needs of individuals within the autism spectrum. These programs should aim to simulate real-life scenarios and facilitate the child’s progress in daily activities. Cognitive software emerges as a promising tool for educational and rehabilitative purposes for these children [18]. Notably, individuals with ASD often process information more effectively through visual stimuli [8], making the use of images and software particularly beneficial in their training. Cognitive digital programs, which incorporate simple games, prompt users to perceive the structure of cognitive software akin to computer games. A key distinction of this software lies in its emphasis on learning through classical conditioning. Implementing such educational and cognitive rehabilitation programs within a gaming framework enhances their appeal and boosts the child’s motivation to engage and complete tasks associated with the game [17].

The social challenges present in children with ASD stem, in part, from deficits in ToM and deficiencies in social cognition [7, 8]. These impairments subsequently impact various aspects of social interactions, relationships, academic pursuits, career prospects, and overall independent living [13]. Cognitive training programs, which introduce fundamental emotions to facilitate the recognition of emotions through visual faces at varying levels and provide computerized feedback based on individual responses, are effective in identifying emotions, such as happiness, sadness, anger, and fear [19]. The instruction of social and emotional skills through cognitive training programs has been linked to a reduction in interpersonal difficulties among children [18], as well as a positive influence on the adoption of constructive emotional strategies, enhancement of social skills [20], and overall mental and social performance in children [18]. Recent research underscores the efficacy of cognitive training programs, particularly those based on computerized platforms, in mitigating behavioral challenges [12], enhancing ToM [18], boosting levels of social interaction and communication [19], facilitating eye contact and shared attention [22], and fostering empathy [23] in children diagnosed with ASD.

The Cogniplus cognitive training program is recognized as computer-based cognitive software and an intelligent interactive system designed to enhance cognitive functions [24]. Developed by the Shepherd company utilizing the Vienna test system, the program’s content validity has been endorsed by the Austrian Neurological Society. The Vienna system stands as a prominent measurement tool globally for digital psychological assessments. Through the utilization of the Cogniplus cognitive training program, individuals can engage in training to enhance general cognitive abilities, working memory, executive functions, and various other cognitive domains. This software offers a moderate level of challenge to users, ensuring reliable assessment of client abilities and automatic adjustment to individual needs. Furthermore, in addition to its cognitive benefits, the Cogniplus software also contributes to improvements in social aspects [25]. This program comprises various game categories, namely the following items: a) Attention (alertness)-based games, b) Working memory-based games, c) Long-term memory involving the learning of face-name associations, d) Executive functions games, e) Spatial processing, and f) Coordination games. The gameplay within this program is structured such that after each successful game completion, the individual receives feedback. As the player progresses, the game speed increases following the individual’s cognitive level. Players can begin with simpler games and gradually advance to more challenging ones [26]. Moreover, the program can automatically adapt and adjust exercises to match the individual’s skill level without altering the core gameplay mechanics. Improved performance leads to faster gameplay [20].

Given that the Cogniplus cognitive rehabilitation program operates on the premise of brain plasticity and self-repair, engaging in its exercises and systematically stimulating underactive brain regions results in the establishment of stable synaptic changes within these areas. This process ultimately enhances cognitive functions, addressing a significant challenge faced by individuals on the autism spectrum. Consequently, the primary hypothesis sought to explore the impact of the Cogniplus cognitive training program on altering social cognition dimensions and varying levels of ToM in children aged 6 to 11 years with ASD.

Materials and Methods

In this semi-experimental study, a pre-test, and post-test design was employed with a control group in addition to a two-month follow-up. The statistical population comprised all children aged 6 to 11 years with ASD in Shahr-e-Ray City, Iran, during the academic year 2022-2023. They were referred to the Noyan Autism Center. Out of this population, 65 children were chosen through the available and non-random sampling method and underwent evaluation using the autism spectrum screening questionnaire [27]. To determine the minimum required sample size for the study, considering financial and time constraints, previous research [16] with a test power of 0.80, a type 1 error rate of 0.05, and accounting for a 10% dropout probability, a total of 50 individuals (25 individuals in each the experimental and control groups) were calculated. After scoring the questionnaire, 50 children diagnosed with high-functioning autism (33 boys and 17 girls) who met the inclusion criteria (demonstrating an interest in playing computer games and scoring 19 or higher on the parent form of the autism spectrum screening questionnaire) were selected. The inclusion criteria were also having 6 to 11 years of age, verbal ability, and the absence of motor disabilities, intellectual impairments, as well as normal visual and auditory functions. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria encompassed concurrent participation in computer cognitive rehabilitation programs within the past six months. Following the selection, the participants were matched based on age and allocated into either the experimental or control group, each consisting of 25 individuals. Data collection involved the administration of the autism spectrum screening questionnaire [27] and the ToM test [28]. The experimental group underwent 20 cognitive rehabilitation sessions, while the control group received standard services offered at the center, including music therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy. Both groups underwent pre- and post-intervention assessments using the ToM test, with a follow-up evaluation conducted two months after the final intervention session. Data analysis was performed using non-parametric regression modeling, specifically generalized estimating equations, with the SPSS software, version 27, for statistical analysis.

Data collection tools

Autism spectrum screening questionnaire

The Ehlers and Gilberg (1999) questionnaire, consisting of 27 items, was designed to assess various aspects of communication, social behavior, restricted and repetitive interests, gross motor skills, and tic disorders in children. Administered by parents or teachers, the questionnaire evaluates auditory and motor functions and typically takes around 10 min to complete. Responses are scored based on a 3-point Likert scale (0=no, 1=somewhat, and 2=yes), with a maximum total score of 54. A total score of 19 or higher on the parent form indicates a diagnosis of high-functioning autism. The questionnaire was translated and validated in Persian by Kasechi et al. [29]. The Cronbach α coefficients were calculated to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire among different groups: Parents of typically developing children (0.77), parents of children with autism (0.68), teachers of typically developing children (0.81), and teachers of children with autism (0.70). Additionally, test re-test reliability coefficients were determined for parents (r=0.467) and teachers (r=0.614), indicating moderate to good reliability over time. To assess the questionnaire’s convergence validity, correlations were computed with two additional child behavior assessments as follows: The Rutter child behavior questionnaires and the child symptoms inventory (CSI-4). The parent form of the questionnaire exhibited a correlation coefficient of 0.715 with the Rutter and 0.486 with the CSI-4. Similarly, the teacher form of the questionnaire showed correlations of 0.495 with the Rutter and 0.411 with the CSI-4. Significant associations were observed between the scores derived from the parent form of the questionnaire in both typically developing children and those with ASD. Furthermore, the Cronbach α coefficient analysis for the teacher form of the questionnaire, conducted among typically developing children and those with ASD, indicated that the questionnaire items are effective in identifying children with high-functioning autism [19]. In this study, the parent form of the questionnaire was utilized for data collection.

ToM test

The ToM test was employed to evaluate social cognition and its various dimensions. Developed in 1999 by Muris et al. [28], this assessment comprises 72 questions. The primary version of the test has been utilized to assess ToM abilities in typically developing children aged 5 to 12 years, as well as subjects with pervasive developmental disorders. It aims to gauge the child’s social understanding, sensitivity, insight, and capacity to articulate emotions and thoughts, offering insights into the individual’s perspective-taking abilities. Ghamarani et al. [30] translated the ToM test into Persian in 2005, adapting the text to align with Persian language concepts. This adaptation led to a reduction in the number of questions from 72 to 38, with Persian names replacing foreign names. Subsequently, the validity and reliability of the adapted test were assessed on a sample of 40 students with educable intellectual disabilities and 40 typically developing students in Shiraz City, Iran. This test serves as a comprehensive and objective assessment designed to measure distinct levels of ToM proficiency as follows: 1) The initial level or ToM1 (comprising 20 questions), 2) The realistic level or TOM2 (comprising 13 questions), and 3) the advanced level or TOM3 (comprising 5 questions). Responses are scored with either zero or one point allocated per answer. An individual’s score for TOM1 falls within the range of 0 to 20, for TOM2 between 0 and 13, and for TOM3 within 0 to 5. By summing the scores across all three levels, the total ToM score (reflecting social cognition) is derived, ranging from 0 to 38. A higher score on the test indicates a more advanced level of ToM attainment. To assess the test’s content validity, correlations were examined between the ToM levels and the total score. Concurrent validity was evaluated by correlating the test results with the doll’s house assignment, yielding a coefficient of 0.89, significant at the P<0.01 level. The correlation coefficients between the ToM levels and the total test score ranged from 0.82 to 0.96. Meanwhile, P<0.01 indicated the statistically significant level. To assess the validity, the test was re-administered to 30 children with a time interval of two to three weeks. Reliability coefficients for the entire test and each of its three levels of ToM were calculated as 0.94, 0.91, 0.70, and 0.93, respectively, with all coefficients showing a significant level at P<0.01. Test reliability was evaluated using the Cronbach α and scorer reliability coefficients. The internal consistency of the test was examined through the Cronbach α coefficient, yielding values of 0.86 for the whole test, 0.72 for the first level, 0.80 for the second level, and 0.81 for the third level of ToM. These results indicate strong internal validity of the test. Additionally, two experts independently assessed and scored the responses of 30 children. The correlation coefficient between the evaluators’ scores served as the reliability index for the scorers, resulting in a value of 0.98, significant at P<0.01 level [30].

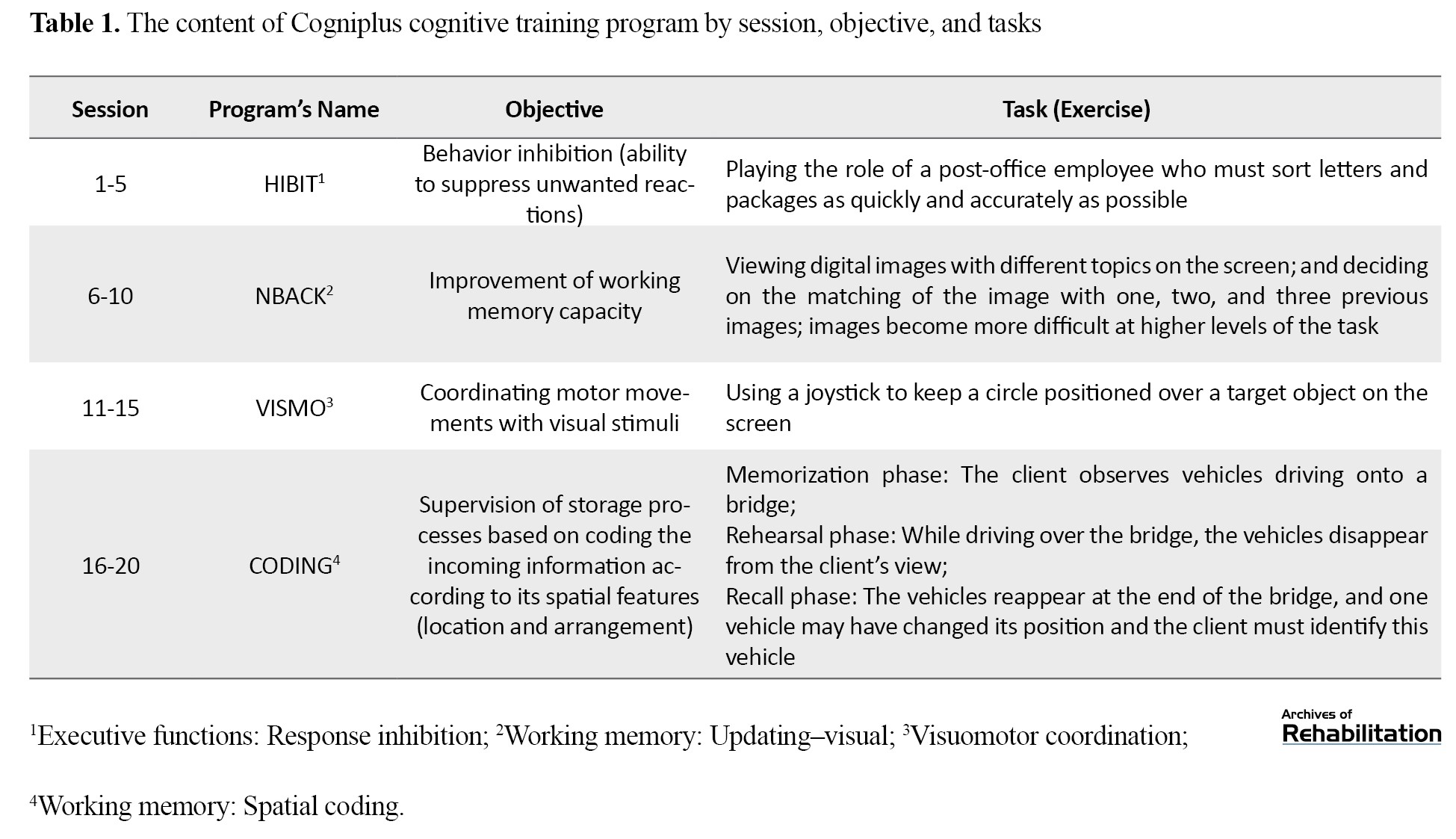

Cogniplus cognitive training program

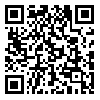

This cognitive software program, developed by Shepherd Company and built upon the Vienna test system, has had its content validity endorsed by the Austrian Neurological Society. The primary objective of this software is to enhance cognitive functions [24]. It operates by dynamically adjusting the difficulty level of exercises based on individual performance and delivering them accordingly. Within the Cogniplus cognitive training program, the speed of gameplay increases in tandem with the player’s proficiency [31]. Feedback is provided after each stage of the game, and as the individual progresses, the game’s speed escalates [32]. Tailoring the game’s complexity to match the player’s cognitive abilities, the program initiates simpler tasks and gradually introduces more challenging gameplay [33]. Improving cognitive functions is anticipated to enhance social skills, particularly social cognition and its various dimensions [31]. This program is computer-based and comprises multiple game categories. The games utilized in this study encompass the following items: a) Attention (alertness)-based games, covering aspects such as alertness phasic, alertness intrinsic, divided attention, focused attention visual, focused attention auditory, selective attention visual, selective attention auditory, visual spatial attention, and vigilance; b) Working memory-based games, involving tasks like spatial coding, updating – spatial, updating – visual, rehearsal, visuospatial; c) Long-term memory, involving the learning of face-name associations; d) Executive functions games, incorporating activities, such as response inhibition, planning and action skills; e) Spatial processing, like mental rotation; and f) Coordination games, like visuomotor coordination. In this research, the Cogniplus cognitive training program was individually administered to participants over 20 sessions (twice weekly, each session lasting 30 min). The meeting’s agenda is outlined in Table 1, detailing the objectives and tasks.

Study procedure

After obtaining the Code of Ethics from the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences and obtaining permission from the Tehran City Welfare Organization, the study sample was selected from the Noyan Rehabilitation Center in Shahr-e-Ray City, Iran, via the available sampling method. After visiting the center, the research objectives were explained to the officials. Subsequently, during individual meetings with the parents, the purpose of the study was communicated, and 65 volunteer parents, whose children had been diagnosed with high-functioning autism, provided written consent for their child’s participation in the study. The parents completed and responded to the autism spectrum screening questionnaire.

After the questionnaire was scored by one of the resident psychologists at the center, 50 out of the 58 children who scored 19 or higher in the questionnaire (33 boys and 17 girls) met the inclusion criteria (such as the child’s interest in playing computer games, age between 6 and 11 years, scoring 19 or above in the parent form of the autism spectrum screening questionnaire, the child’s ability to speak, and the absence of motor disability, intellectual disability, and sensory impairments including vision and hearing). They also met the exclusion criteria (not participating in similar computer-based cognitive training programs in the last six months or at the same time).

The children were selected via the available sampling method. Subsequently, after age matching, the children were randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group. The parents were then requested to complete the ToM test. The experimental group underwent the Cogniplus cognitive training program in 20 individual sessions, each lasting 30 min (twice a week at varying times outside the center’s regular programs). In contrast, the control group received standard services at the center (occupational therapy, speech therapy, art therapy, and music therapy) along with piano and puzzle mobile games. Following the final training session (at the end of the tenth week) and two months later, all participants in both the experimental and control groups underwent evaluation using the ToM test. The administration of the questionnaires and the Cogniplus cognitive training program was conducted by the researcher. The scoring of all questionnaires was performed by a resident psychologist in the Center with the requisite expertise in questionnaire evaluation. Meanwhile, the psychologist was unaware of whether the questionnaire pertained to the experimental or control group. The research data were analyzed utilizing correlation analysis, regression analysis, and generalized estimating equations in the SPSS software, version 27.

Results

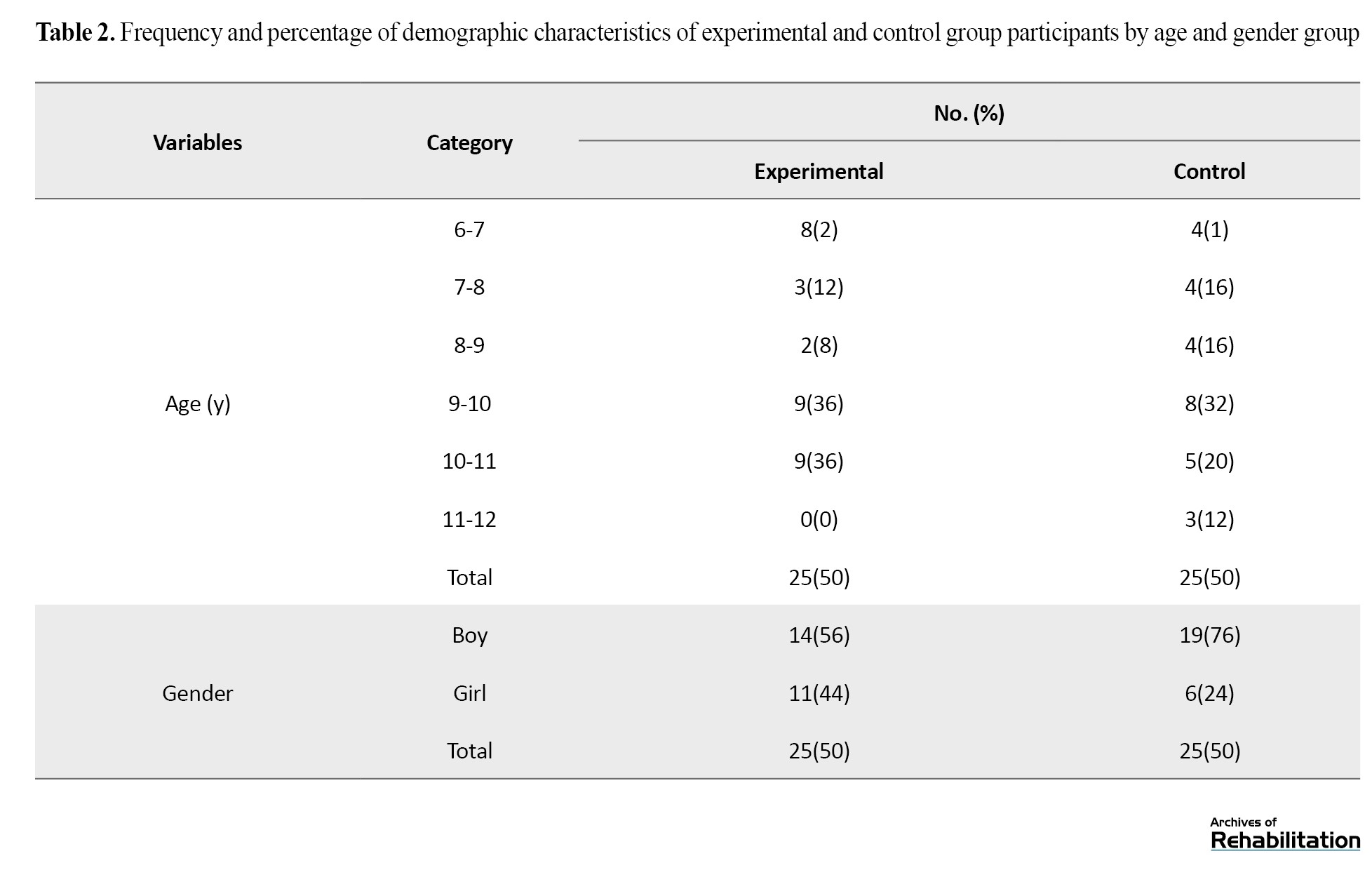

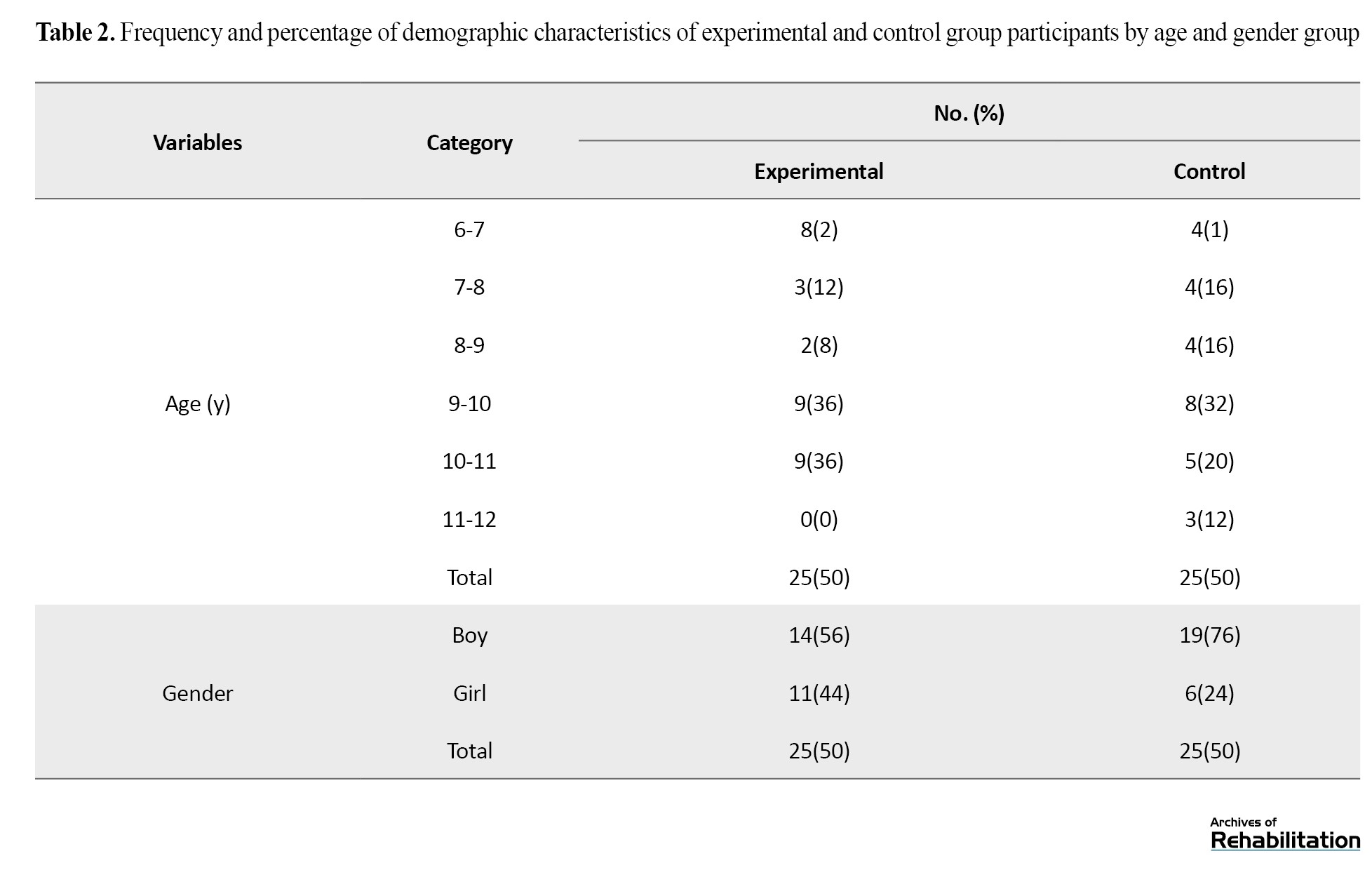

Descriptive indices of age variables are presented separately in two experimental and control groups in Table 2.

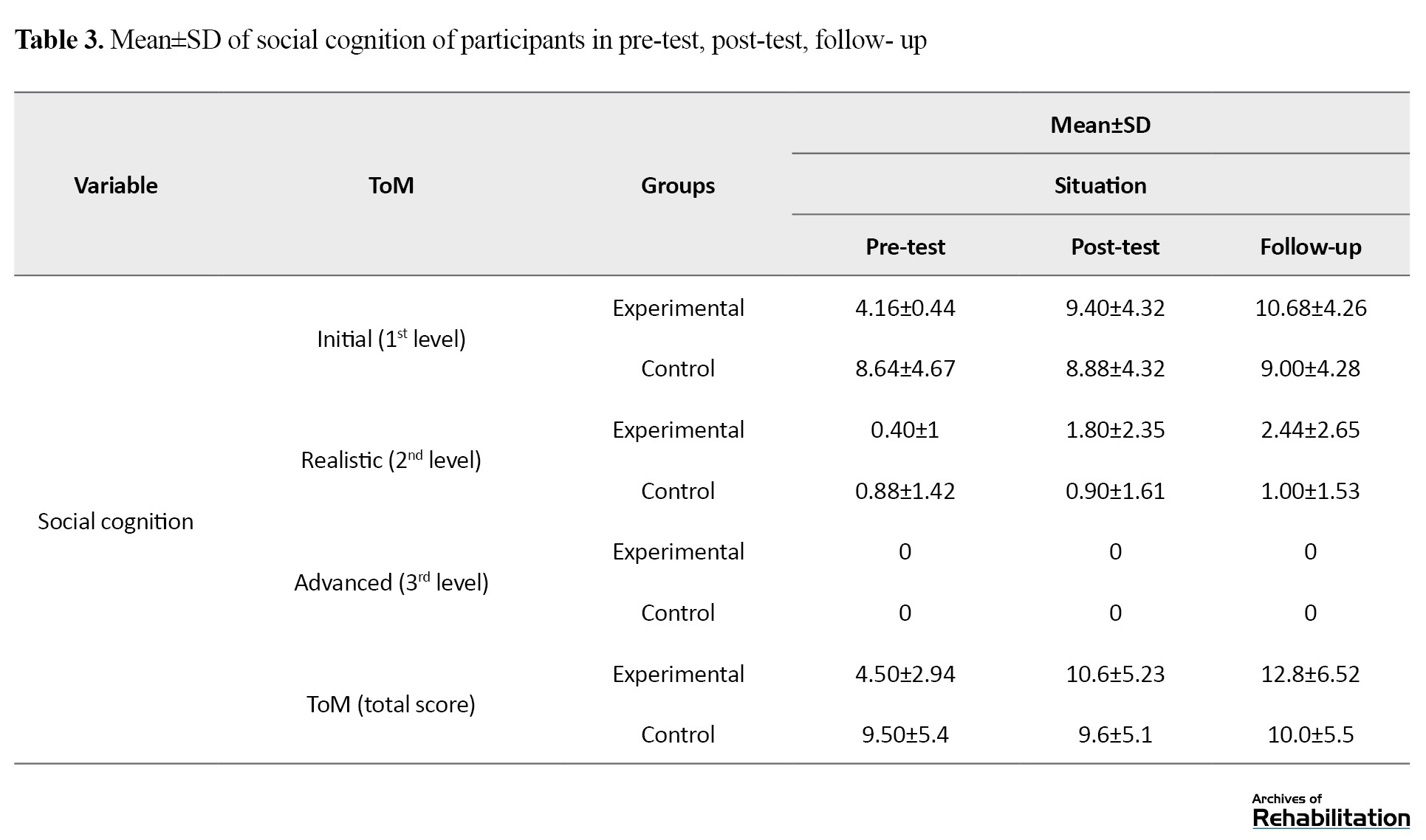

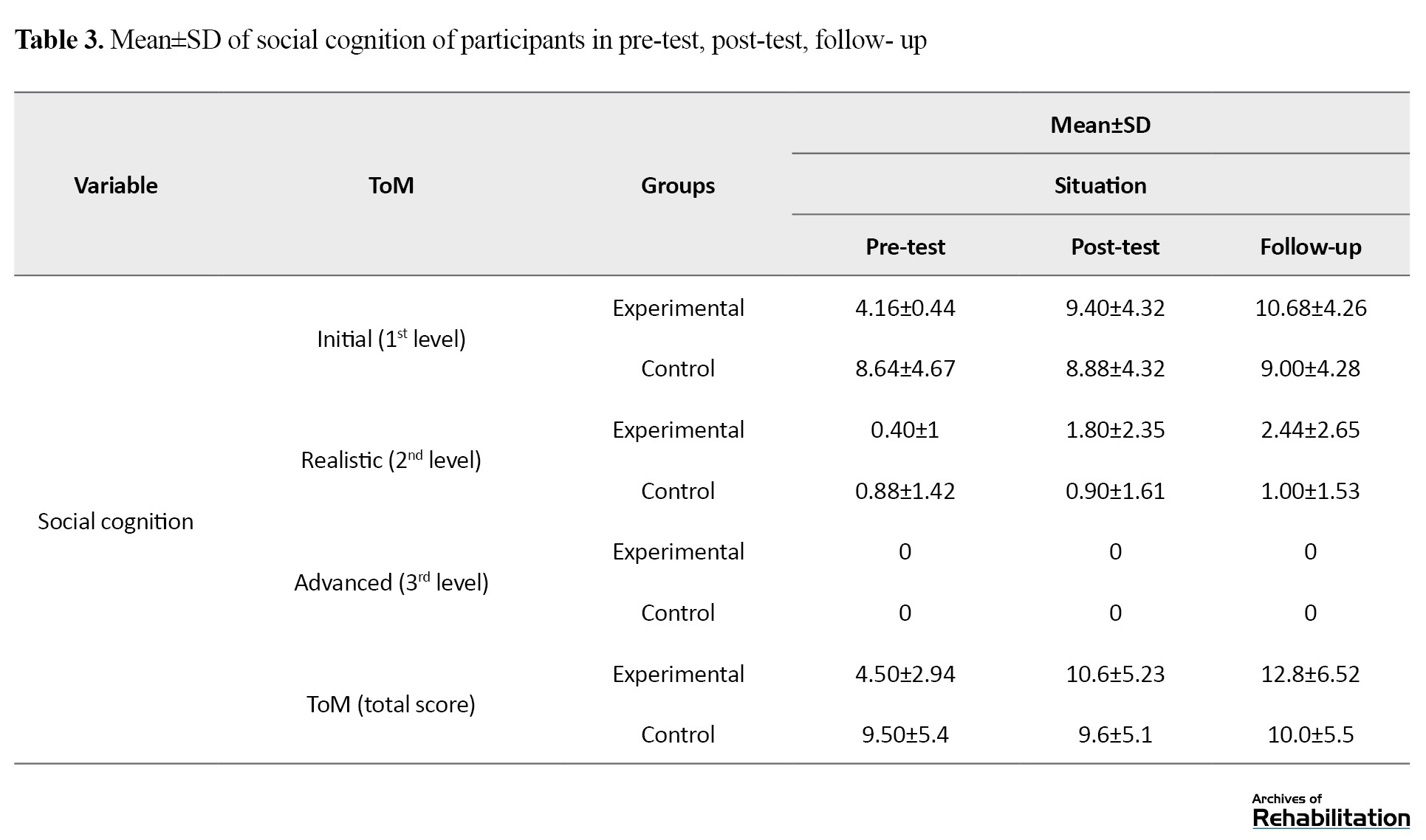

To determine the equality of the two groups in terms of age, the chi-square test was employed, with the results detailed in Table 2. As illustrated in Table 2, the highest proportion of participants in the experimental group falls within the age brackets of 9 to 10 years and 10 to 11 years (36%), while the majority of participants in the control group are aged 9 to 10 years (32%). Based on the chi-square statistic’s significance level (P=0.375), the age differential between the experimental and control groups is not significant, indicating equality in age distribution between both groups. The Mean±SD of the social cognition variable (comprising ToM and its levels) for participants in both the experimental and control groups are outlined in Table 3.

As depicted in Table 3, the mean social cognition scores (the first level: Initial ToM; second level: Realistic ToM; and the total ToM score) in the experimental group showed an increase in the post-test and follow-up assessments compared to the pre-test evaluation. Conversely, such a notable change was not observed in the control group, despite an increase in scores from the pre-test to the post-test phase. The participants struggled to attain any marks in the tasks associated with the third level of ToM, which is known to be more challenging than the preceding levels.

To examine the hypothesis that the Cogniplus cognitive training program alters the facets of social cognition and various levels of ToM in children aged 6 to 11 years with ASD, a non-parametric regression modeling analysis method (employing generalized estimation equations to assess longitudinal data) was utilized. Initially, the normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics for the initial ToM (first level=0.093), realistic ToM (second level=0.292), and the total ToM score (0.094), all obtained results are statistically significant at the P<0.01 level. Furthermore, considering the Shapiro-Wilk scores for the initial ToM (first level=0.976), realistic ToM (second level=0.685), and the total ToM score (0.967), all statistics are significant at the P>0.01 level.

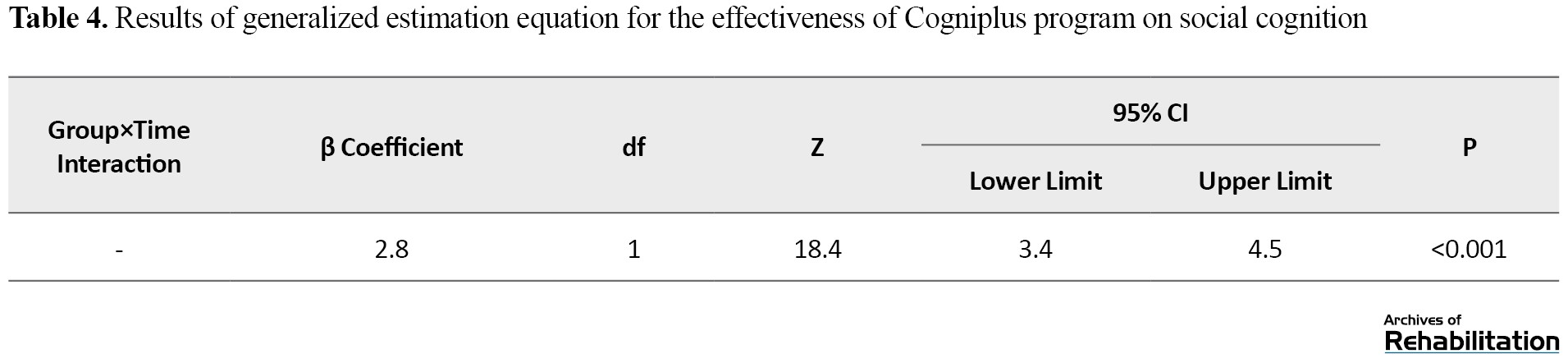

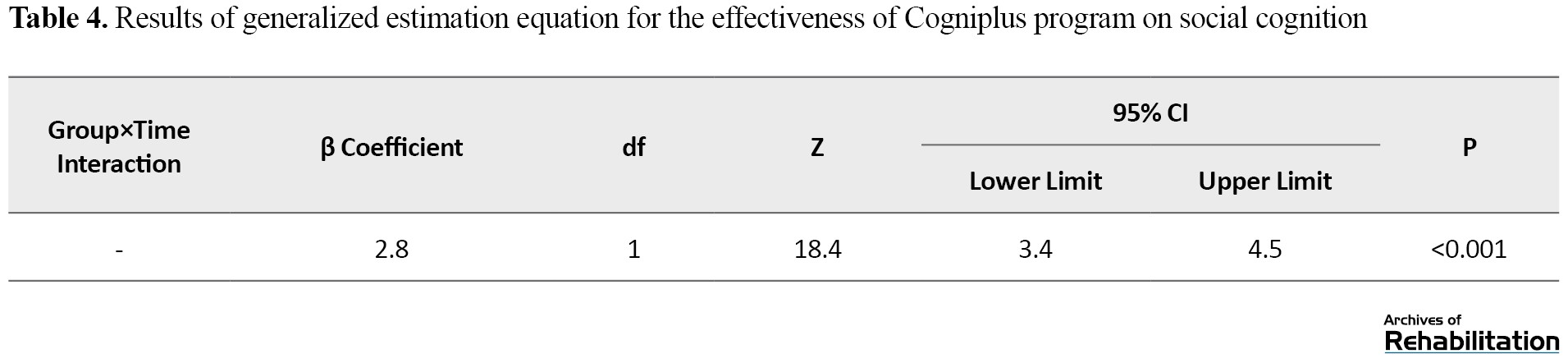

Consequently, the variables exhibit non-normal distribution and the presence of outliers in the data distribution is noted. The data distribution is not bell-shaped, and with a significance level P<0.01, the analysis was conducted using the generalized estimation equation method, with the results outlined in Table 4.

Based on the findings from Table 4, the progression of alterations in social cognition (specifically the overall ToM score) has exhibited a significant increase (P<0.001) in the experimental group compared to the control group, with a difference of 2.8 observed over time. As a result, the research hypothesis has been validated, indicating that the effectiveness of the cognitive rehabilitation program on social cognition has been sustained even after a two-month follow-up period.

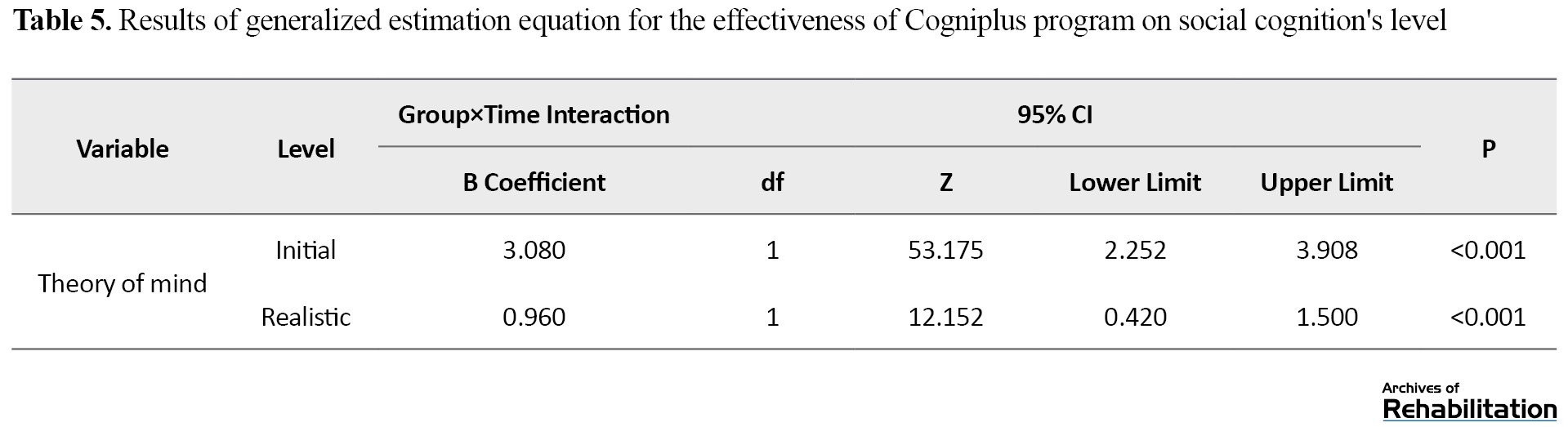

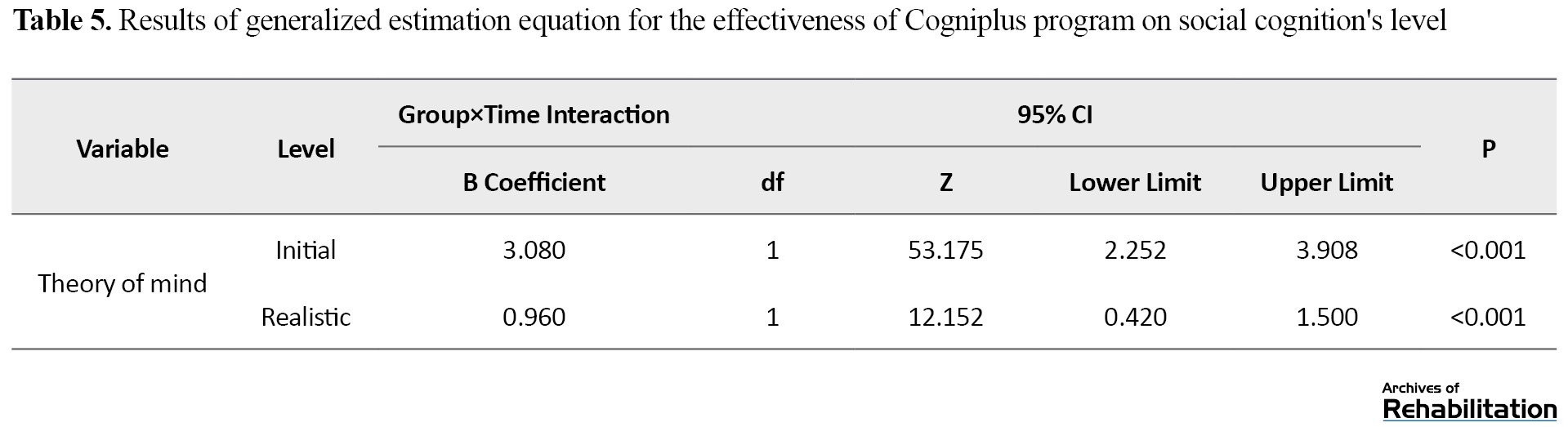

The method of generalized estimating equations was employed to explore the research inquiries surrounding whether the cognitive rehabilitation program impacts the facets of social cognition (including initial and realistic levels of ToM) in children aged 6 to 11 years with ASD. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 5.

According to Table 5, the trajectory of variations in the initial level and the realistic level (corresponding to the first and second levels of ToM) over time in the experimental group, in comparison to the control group, has demonstrated a significant increase of 3.08 and 0.96 units, respectively (P<0.001). Consequently, it is plausible to deduce that the Cogniplus cognitive training program has influenced the initial and realistic ToM (the first and second levels of ToM) in children aged 6 to 11 years of ASD.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of the Cogniplus cognitive training program on social cognition and ToM levels in children aged 6 to 11 years diagnosed with ASD. The initial finding of the research suggests that the Cogniplus cognitive training program enhances social cognition in children within this age group who have high-functioning ASD. This outcome aligns with the findings reported by Darvishi et al. [11], and Yaghini et al. [12], further supporting the positive impact of such cognitive training programs on social cognition in children with ASD. Accordingly, the Cogniplus cognitive training program places a significant emphasis on instructing emotion recognition and enhancing imitation skills in children diagnosed with ASD. The acquisition of these skills aids in the learning of self-regulation strategies for children on the autism spectrum, who may exhibit slower development in these areas. As a consequence, the enhancement of social cognition, particularly in terms of ToM levels, is observed. In line with the theory of disrupted mirror neurons, impairment in the mirror neuron system of the brain may impede communication, imitation abilities, and the advancement of ToM in children with ASD. Engaging in the exercises and tasks incorporated in the Cogniplus cognitive training program has been suggested to ameliorate the functioning of mirror neurons [12], thereby facilitating the child’s capacity to engage in appropriate imitation activities. This improvement in imitation skills can contribute to the child’s ability to comprehend and interpret the emotions and sentiments of others, ultimately fostering the growth and evolution of their social cognition.

The second key finding of the study suggests that the Cogniplus cognitive training program has effectively altered and enhanced both the initial ToM (level one) and the realistic ToM (level two) in children aged 6 to 11 years diagnosed with ASD. This result is in line with the outcomes of a previous study [34]. Existing research indicates that engaging in movement games [35] and participating in exercises focused on response inhibition and working memory can positively influence the enhancement of the first and second levels of ToM. Given that the Cogniplus cognitive training program incorporates movement games designed to bolster working memory and exercises targeting response inhibition, as shown in a study [36], these movement-based activities enhance cognitive flexibility in children. This enhanced cognitive flexibility plays a pivotal role in the development of ToM. Accordingly, the ability of individuals to dissect components of a unified whole and identify various emotions and feelings necessitates a robust active memory capacity. Therefore, engaging in movement exercises has improved active memory capacity and visual-spatial memory, consequently leading to enhancements in both the initial and realistic levels of ToM [36].

One of the findings from the research indicated that undergoing the cognitive rehabilitation program did not have a significant impact on the advanced ToM (third level) in children aged 6 to 11 years diagnosed with ASD. These results are in line with findings from previous studies [33, 37] and are contradictory to the outcomes of two other studies [38, 39]. According to Sayfi’s study [37], interventions and training based on ToM may only enhance certain levels of ToM in children with ASD. The research by Mansuri et al. [40] revealed that children with ASD possess a ToM, albeit in a rudimentary and preliminary form. These findings are at odds with some earlier studies [38, 39] suggesting that children with ASD can attain the third and advanced level of ToM. Hence, the children in the present study may belong to a subgroup of individuals with ASD who exhibit different cognitive abilities and IQ levels compared to those examined in previous research. In the recent explanation provided, it is highlighted that the tasks associated with the second level of ToM are more challenging in comparison to those linked to the first level. Therefore, tasks at the third level of ToM are more intricate. The advanced skills required for ToM surpass the comprehension needed for the basic level tasks and necessitate an understanding of complex cognitive, epistemic, and emotional states. In essence, the third-level tasks involve interpreting mental states in situations characterized by uncertainty or lack of transparency, demanding multiple inferences to be drawn. Due to these heightened complexities, children with ASD may struggle to complete tasks at this level of ToM. As per Ganea’s perspective [41], advanced ToM skills play a crucial role in facilitating sophisticated social interactions and academic achievements.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of the current research, it was observed that social cognition, including the overall score of ToM and its first and second levels, improved in children with ASD following their participation in the Cogniplus cognitive training program. Furthermore, this improvement was sustained even after two months post-training. Cognitive training program are designed to retain cognitive functions through practice, adaptation, and implicit learning. These programs are rooted in the concept of brain plasticity and self-repair, where engaging in exercises that stimulate fewer active areas of the brain can lead to stable synaptic changes in those regions. This, in turn, can result in enhanced cognitive functions.

The cognitive training program, such as Cogniplus, operates on the principles of information processing, providing individuals with feedback on their abilities and self-efficacy. By engaging individuals in exercises and computer activities, the program can foster interest and motivation, encouraging continued participation. Therefore, incorporating the exercises used in the Cogniplus program as part of training for children with ASD could be beneficial. The findings from the research may be of interest to special education specialists and educational program designers, enabling them to develop educational programs that incorporate computer games. These programs can enhance motivation for educational activities among children with ASD and cater to the individual needs of each child, allowing for personalized learning experiences based on their abilities. Given that ASD is associated with significant impairments in social cognition functions, particularly ToM, as well as challenges in communication and social interaction, parents and educators must provide a supportive and enriching environment for children with ASD from the early stages of diagnosis. By offering appropriate training to nurture the hidden mental and cognitive talents of these children, the severity of the impairments caused by ASD on social cognition functions can be mitigated. This approach can help individuals with ASD develop and thrive in their social interactions and communication skills.

Study limitations

The research study outlined several significant limitations that could impact the generalizability and robustness of the findings. These limitations include the use of a non-random and limited sampling method, the absence of multiple assessment tools for evaluating social cognition, the inability to compare experimental and control groups based on gender and age variables, and the lack of IQ measurement among study participants. Furthermore, relying solely on parent reports through an autism spectrum screening questionnaire may restrict the generalizability of the results. To address these limitations and enhance the validity of future research efforts, it is recommended to employ random sampling methods that encompass both genders and a wider age range. Additionally, measuring the IQ levels of children with ASD, utilizing multiple tools for assessing social cognition and ToM, and moving beyond sole reliance on parent reports can contribute to more comprehensive and accurate results regarding the efficacy of cognitive training programs like Cogniplus on social cognition in children with disorders. Moreover, extending the follow-up period post-intervention can offer insights into the long-term effectiveness of cognitive training programs in strengthening social cognition and ToM dimensions in children with ASD. This extended evaluation period can help determine whether the benefits of such interventions persist over time.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.063). To comply with ethical considerations, the objectives of the research were fully informed to the officials of the Noyan Rehabilitation Center and parents of children with ASD. After obtaining written consent from mothers, they were assured that the information obtained from the questionnaires would remain confidential. Their children’s participation in the research will not involve any losses and children who did not want to continue cooperation could withdraw from the research. While paying attention to the mental states and fatigue of children, efforts were made to respect their dignity and human rights during the research.

Funding

This article is a part of the master’s thesis of Zahra Tajik, approved by Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Zahra Tajik, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi and Marjan Poshtmashhadi; Methodology and data analysis: Zahra Tajik, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi and Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi; Validation and sources Zahra Tajik, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi, Marjan Poshtmashhadi and Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi; Writing the original draft: Zahra Tajik and Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi; Visualization, review and editing: Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi; Supervision: Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi, Marjan Poshtmashhadi and Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi; Project management: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors hereby express their gratitude to the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, and Welfare Organization in Tehran City, Iran and the officials of the Noyan Rehabilitation Center in Shahr-e-Ray City, Iran.

References

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is classified as a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by impairments in communication, and social interaction, and the presence of repetitive and restricted behavioral patterns. These hallmark symptoms manifest early in childhood and can significantly impede daily functioning. As of 2023, the reported prevalence rate of ASD in children stands at 1 per 36 births [1]. In Iran, the prevalence of this disorder has been documented at 6.26 per 10,000 [2].

One of the crucial components of communication and interaction is social cognition. Social cognition encompasses all the skills necessary for children to comprehend desires, emotions, and feelings [3], serving as a mechanism to interpret and process societal cues and align them with an individual’s internal physiological state. This process elicits a behavioral response that is appropriate to a given situation [4]. The development of social cognition commences in the early stages of life, with infants’ observation of how individuals react to social stimuli and occurrences serving as the foundation for the advancement and comprehension of social cognition. Furthermore, the development of social cognition is a product of the development of the theory of mind (ToM) [4]. ToM refers to the capacity to comprehend the thoughts and emotions of others and comprises the following three levels. The initial ToM (first level) which entails the identification of emotions. The realistic ToM (second level) involves the recognition that individuals’ beliefs or mental states can diverge, even when some of these beliefs are not in alignment with reality. The advanced ToM (third level) which signifies that individuals may occasionally hold incorrect and mistaken notions about others’ beliefs. Additionally, it denotes an individual’s proficiency in making informal declarations like joking, teasing, and deceiving [5]. Deficiencies in these factors are linked to challenges in comprehending the self and others’ thoughts, desires, and emotions, resulting in a failure to establish effective communication structures with others and impacting the quality of a child’s life [6]. The social impairments seen in children with ASD are partly attributed to deficits in ToM [7, 8]. The absence or impairment of social cognition influences social interactions, relationships, educational and occupational settings, and overall independent living [8].

Playing as a component of educational and rehabilitative interventions is consistently regarded as a beneficial approach to enhancing and refining the social cognition of children with ASD [9]. The efficacy of physical and movement games [8], cognitive games [9], and social games [10] in ameliorating the symptoms of ASD has been substantiated. Among the various games utilized today, digital and computer-based games are prevalent. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation through computer games in enhancing ToM [11], mitigating behavioral issues, enhancing ToM [12], and improving skills and social performance [13] in children with ASD. Due to the visual presentation of information in computer-based games, they hold an appeal for children with ASD [10]. Computer-based games exhibit significant potential in the realm of special education, serving as tools for assessing autism-related challenges and as valuable resources for therapeutic and educational purposes. Given that children with autism may experience confusion and tension in traditional educational and therapeutic settings, they often miss out on learning opportunities. Engaging in computer-based games offers them a controlled educational environment conducive to learning [14]. These games can enhance social skills by bolstering essential cognitive abilities such as attention, memory, and motivation [3]. Because of children’s limited interest in conventional cognitive approaches [8] and the beneficial impact of cognitive software on the cognitive capabilities of individuals with ASD [15], there is a growing trend toward utilizing digitally presented cognitive training programs, some of which are referred to as cognitive rehabilitation programs.

Cognitive rehabilitation, as explored in current research, involves a computer-based approach that relies on the fundamental information processing system. It offers feedback on an individual’s abilities and self-efficacy, tailoring educational programs to match the individual’s skill set. This intervention method begins by enhancing basic skills, gradually increasing the complexity of exercises. Progress reports on the individual’s performance in these exercises are shared with therapists, enabling them to assist individuals in enhancing crucial mental processes essential for advanced learning [16]. The exercises within cognitive training programs aim to enhance cognitive functions related to sustained concentration, response inhibition, visual and auditory processing, reading, and memory [17].

Given the rising prevalence of ASD globally and in Iran, along with growing concerns regarding social interaction and cognition challenges faced by these children, there is a pressing need to focus on programs tailored to address the specific needs of individuals within the autism spectrum. These programs should aim to simulate real-life scenarios and facilitate the child’s progress in daily activities. Cognitive software emerges as a promising tool for educational and rehabilitative purposes for these children [18]. Notably, individuals with ASD often process information more effectively through visual stimuli [8], making the use of images and software particularly beneficial in their training. Cognitive digital programs, which incorporate simple games, prompt users to perceive the structure of cognitive software akin to computer games. A key distinction of this software lies in its emphasis on learning through classical conditioning. Implementing such educational and cognitive rehabilitation programs within a gaming framework enhances their appeal and boosts the child’s motivation to engage and complete tasks associated with the game [17].

The social challenges present in children with ASD stem, in part, from deficits in ToM and deficiencies in social cognition [7, 8]. These impairments subsequently impact various aspects of social interactions, relationships, academic pursuits, career prospects, and overall independent living [13]. Cognitive training programs, which introduce fundamental emotions to facilitate the recognition of emotions through visual faces at varying levels and provide computerized feedback based on individual responses, are effective in identifying emotions, such as happiness, sadness, anger, and fear [19]. The instruction of social and emotional skills through cognitive training programs has been linked to a reduction in interpersonal difficulties among children [18], as well as a positive influence on the adoption of constructive emotional strategies, enhancement of social skills [20], and overall mental and social performance in children [18]. Recent research underscores the efficacy of cognitive training programs, particularly those based on computerized platforms, in mitigating behavioral challenges [12], enhancing ToM [18], boosting levels of social interaction and communication [19], facilitating eye contact and shared attention [22], and fostering empathy [23] in children diagnosed with ASD.

The Cogniplus cognitive training program is recognized as computer-based cognitive software and an intelligent interactive system designed to enhance cognitive functions [24]. Developed by the Shepherd company utilizing the Vienna test system, the program’s content validity has been endorsed by the Austrian Neurological Society. The Vienna system stands as a prominent measurement tool globally for digital psychological assessments. Through the utilization of the Cogniplus cognitive training program, individuals can engage in training to enhance general cognitive abilities, working memory, executive functions, and various other cognitive domains. This software offers a moderate level of challenge to users, ensuring reliable assessment of client abilities and automatic adjustment to individual needs. Furthermore, in addition to its cognitive benefits, the Cogniplus software also contributes to improvements in social aspects [25]. This program comprises various game categories, namely the following items: a) Attention (alertness)-based games, b) Working memory-based games, c) Long-term memory involving the learning of face-name associations, d) Executive functions games, e) Spatial processing, and f) Coordination games. The gameplay within this program is structured such that after each successful game completion, the individual receives feedback. As the player progresses, the game speed increases following the individual’s cognitive level. Players can begin with simpler games and gradually advance to more challenging ones [26]. Moreover, the program can automatically adapt and adjust exercises to match the individual’s skill level without altering the core gameplay mechanics. Improved performance leads to faster gameplay [20].

Given that the Cogniplus cognitive rehabilitation program operates on the premise of brain plasticity and self-repair, engaging in its exercises and systematically stimulating underactive brain regions results in the establishment of stable synaptic changes within these areas. This process ultimately enhances cognitive functions, addressing a significant challenge faced by individuals on the autism spectrum. Consequently, the primary hypothesis sought to explore the impact of the Cogniplus cognitive training program on altering social cognition dimensions and varying levels of ToM in children aged 6 to 11 years with ASD.

Materials and Methods

In this semi-experimental study, a pre-test, and post-test design was employed with a control group in addition to a two-month follow-up. The statistical population comprised all children aged 6 to 11 years with ASD in Shahr-e-Ray City, Iran, during the academic year 2022-2023. They were referred to the Noyan Autism Center. Out of this population, 65 children were chosen through the available and non-random sampling method and underwent evaluation using the autism spectrum screening questionnaire [27]. To determine the minimum required sample size for the study, considering financial and time constraints, previous research [16] with a test power of 0.80, a type 1 error rate of 0.05, and accounting for a 10% dropout probability, a total of 50 individuals (25 individuals in each the experimental and control groups) were calculated. After scoring the questionnaire, 50 children diagnosed with high-functioning autism (33 boys and 17 girls) who met the inclusion criteria (demonstrating an interest in playing computer games and scoring 19 or higher on the parent form of the autism spectrum screening questionnaire) were selected. The inclusion criteria were also having 6 to 11 years of age, verbal ability, and the absence of motor disabilities, intellectual impairments, as well as normal visual and auditory functions. Meanwhile, the exclusion criteria encompassed concurrent participation in computer cognitive rehabilitation programs within the past six months. Following the selection, the participants were matched based on age and allocated into either the experimental or control group, each consisting of 25 individuals. Data collection involved the administration of the autism spectrum screening questionnaire [27] and the ToM test [28]. The experimental group underwent 20 cognitive rehabilitation sessions, while the control group received standard services offered at the center, including music therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy. Both groups underwent pre- and post-intervention assessments using the ToM test, with a follow-up evaluation conducted two months after the final intervention session. Data analysis was performed using non-parametric regression modeling, specifically generalized estimating equations, with the SPSS software, version 27, for statistical analysis.

Data collection tools

Autism spectrum screening questionnaire

The Ehlers and Gilberg (1999) questionnaire, consisting of 27 items, was designed to assess various aspects of communication, social behavior, restricted and repetitive interests, gross motor skills, and tic disorders in children. Administered by parents or teachers, the questionnaire evaluates auditory and motor functions and typically takes around 10 min to complete. Responses are scored based on a 3-point Likert scale (0=no, 1=somewhat, and 2=yes), with a maximum total score of 54. A total score of 19 or higher on the parent form indicates a diagnosis of high-functioning autism. The questionnaire was translated and validated in Persian by Kasechi et al. [29]. The Cronbach α coefficients were calculated to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire among different groups: Parents of typically developing children (0.77), parents of children with autism (0.68), teachers of typically developing children (0.81), and teachers of children with autism (0.70). Additionally, test re-test reliability coefficients were determined for parents (r=0.467) and teachers (r=0.614), indicating moderate to good reliability over time. To assess the questionnaire’s convergence validity, correlations were computed with two additional child behavior assessments as follows: The Rutter child behavior questionnaires and the child symptoms inventory (CSI-4). The parent form of the questionnaire exhibited a correlation coefficient of 0.715 with the Rutter and 0.486 with the CSI-4. Similarly, the teacher form of the questionnaire showed correlations of 0.495 with the Rutter and 0.411 with the CSI-4. Significant associations were observed between the scores derived from the parent form of the questionnaire in both typically developing children and those with ASD. Furthermore, the Cronbach α coefficient analysis for the teacher form of the questionnaire, conducted among typically developing children and those with ASD, indicated that the questionnaire items are effective in identifying children with high-functioning autism [19]. In this study, the parent form of the questionnaire was utilized for data collection.

ToM test

The ToM test was employed to evaluate social cognition and its various dimensions. Developed in 1999 by Muris et al. [28], this assessment comprises 72 questions. The primary version of the test has been utilized to assess ToM abilities in typically developing children aged 5 to 12 years, as well as subjects with pervasive developmental disorders. It aims to gauge the child’s social understanding, sensitivity, insight, and capacity to articulate emotions and thoughts, offering insights into the individual’s perspective-taking abilities. Ghamarani et al. [30] translated the ToM test into Persian in 2005, adapting the text to align with Persian language concepts. This adaptation led to a reduction in the number of questions from 72 to 38, with Persian names replacing foreign names. Subsequently, the validity and reliability of the adapted test were assessed on a sample of 40 students with educable intellectual disabilities and 40 typically developing students in Shiraz City, Iran. This test serves as a comprehensive and objective assessment designed to measure distinct levels of ToM proficiency as follows: 1) The initial level or ToM1 (comprising 20 questions), 2) The realistic level or TOM2 (comprising 13 questions), and 3) the advanced level or TOM3 (comprising 5 questions). Responses are scored with either zero or one point allocated per answer. An individual’s score for TOM1 falls within the range of 0 to 20, for TOM2 between 0 and 13, and for TOM3 within 0 to 5. By summing the scores across all three levels, the total ToM score (reflecting social cognition) is derived, ranging from 0 to 38. A higher score on the test indicates a more advanced level of ToM attainment. To assess the test’s content validity, correlations were examined between the ToM levels and the total score. Concurrent validity was evaluated by correlating the test results with the doll’s house assignment, yielding a coefficient of 0.89, significant at the P<0.01 level. The correlation coefficients between the ToM levels and the total test score ranged from 0.82 to 0.96. Meanwhile, P<0.01 indicated the statistically significant level. To assess the validity, the test was re-administered to 30 children with a time interval of two to three weeks. Reliability coefficients for the entire test and each of its three levels of ToM were calculated as 0.94, 0.91, 0.70, and 0.93, respectively, with all coefficients showing a significant level at P<0.01. Test reliability was evaluated using the Cronbach α and scorer reliability coefficients. The internal consistency of the test was examined through the Cronbach α coefficient, yielding values of 0.86 for the whole test, 0.72 for the first level, 0.80 for the second level, and 0.81 for the third level of ToM. These results indicate strong internal validity of the test. Additionally, two experts independently assessed and scored the responses of 30 children. The correlation coefficient between the evaluators’ scores served as the reliability index for the scorers, resulting in a value of 0.98, significant at P<0.01 level [30].

Cogniplus cognitive training program

This cognitive software program, developed by Shepherd Company and built upon the Vienna test system, has had its content validity endorsed by the Austrian Neurological Society. The primary objective of this software is to enhance cognitive functions [24]. It operates by dynamically adjusting the difficulty level of exercises based on individual performance and delivering them accordingly. Within the Cogniplus cognitive training program, the speed of gameplay increases in tandem with the player’s proficiency [31]. Feedback is provided after each stage of the game, and as the individual progresses, the game’s speed escalates [32]. Tailoring the game’s complexity to match the player’s cognitive abilities, the program initiates simpler tasks and gradually introduces more challenging gameplay [33]. Improving cognitive functions is anticipated to enhance social skills, particularly social cognition and its various dimensions [31]. This program is computer-based and comprises multiple game categories. The games utilized in this study encompass the following items: a) Attention (alertness)-based games, covering aspects such as alertness phasic, alertness intrinsic, divided attention, focused attention visual, focused attention auditory, selective attention visual, selective attention auditory, visual spatial attention, and vigilance; b) Working memory-based games, involving tasks like spatial coding, updating – spatial, updating – visual, rehearsal, visuospatial; c) Long-term memory, involving the learning of face-name associations; d) Executive functions games, incorporating activities, such as response inhibition, planning and action skills; e) Spatial processing, like mental rotation; and f) Coordination games, like visuomotor coordination. In this research, the Cogniplus cognitive training program was individually administered to participants over 20 sessions (twice weekly, each session lasting 30 min). The meeting’s agenda is outlined in Table 1, detailing the objectives and tasks.

Study procedure

After obtaining the Code of Ethics from the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences and obtaining permission from the Tehran City Welfare Organization, the study sample was selected from the Noyan Rehabilitation Center in Shahr-e-Ray City, Iran, via the available sampling method. After visiting the center, the research objectives were explained to the officials. Subsequently, during individual meetings with the parents, the purpose of the study was communicated, and 65 volunteer parents, whose children had been diagnosed with high-functioning autism, provided written consent for their child’s participation in the study. The parents completed and responded to the autism spectrum screening questionnaire.

After the questionnaire was scored by one of the resident psychologists at the center, 50 out of the 58 children who scored 19 or higher in the questionnaire (33 boys and 17 girls) met the inclusion criteria (such as the child’s interest in playing computer games, age between 6 and 11 years, scoring 19 or above in the parent form of the autism spectrum screening questionnaire, the child’s ability to speak, and the absence of motor disability, intellectual disability, and sensory impairments including vision and hearing). They also met the exclusion criteria (not participating in similar computer-based cognitive training programs in the last six months or at the same time).

The children were selected via the available sampling method. Subsequently, after age matching, the children were randomly assigned to either the experimental or control group. The parents were then requested to complete the ToM test. The experimental group underwent the Cogniplus cognitive training program in 20 individual sessions, each lasting 30 min (twice a week at varying times outside the center’s regular programs). In contrast, the control group received standard services at the center (occupational therapy, speech therapy, art therapy, and music therapy) along with piano and puzzle mobile games. Following the final training session (at the end of the tenth week) and two months later, all participants in both the experimental and control groups underwent evaluation using the ToM test. The administration of the questionnaires and the Cogniplus cognitive training program was conducted by the researcher. The scoring of all questionnaires was performed by a resident psychologist in the Center with the requisite expertise in questionnaire evaluation. Meanwhile, the psychologist was unaware of whether the questionnaire pertained to the experimental or control group. The research data were analyzed utilizing correlation analysis, regression analysis, and generalized estimating equations in the SPSS software, version 27.

Results

Descriptive indices of age variables are presented separately in two experimental and control groups in Table 2.

To determine the equality of the two groups in terms of age, the chi-square test was employed, with the results detailed in Table 2. As illustrated in Table 2, the highest proportion of participants in the experimental group falls within the age brackets of 9 to 10 years and 10 to 11 years (36%), while the majority of participants in the control group are aged 9 to 10 years (32%). Based on the chi-square statistic’s significance level (P=0.375), the age differential between the experimental and control groups is not significant, indicating equality in age distribution between both groups. The Mean±SD of the social cognition variable (comprising ToM and its levels) for participants in both the experimental and control groups are outlined in Table 3.

As depicted in Table 3, the mean social cognition scores (the first level: Initial ToM; second level: Realistic ToM; and the total ToM score) in the experimental group showed an increase in the post-test and follow-up assessments compared to the pre-test evaluation. Conversely, such a notable change was not observed in the control group, despite an increase in scores from the pre-test to the post-test phase. The participants struggled to attain any marks in the tasks associated with the third level of ToM, which is known to be more challenging than the preceding levels.

To examine the hypothesis that the Cogniplus cognitive training program alters the facets of social cognition and various levels of ToM in children aged 6 to 11 years with ASD, a non-parametric regression modeling analysis method (employing generalized estimation equations to assess longitudinal data) was utilized. Initially, the normality of data distribution was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistics for the initial ToM (first level=0.093), realistic ToM (second level=0.292), and the total ToM score (0.094), all obtained results are statistically significant at the P<0.01 level. Furthermore, considering the Shapiro-Wilk scores for the initial ToM (first level=0.976), realistic ToM (second level=0.685), and the total ToM score (0.967), all statistics are significant at the P>0.01 level.

Consequently, the variables exhibit non-normal distribution and the presence of outliers in the data distribution is noted. The data distribution is not bell-shaped, and with a significance level P<0.01, the analysis was conducted using the generalized estimation equation method, with the results outlined in Table 4.

Based on the findings from Table 4, the progression of alterations in social cognition (specifically the overall ToM score) has exhibited a significant increase (P<0.001) in the experimental group compared to the control group, with a difference of 2.8 observed over time. As a result, the research hypothesis has been validated, indicating that the effectiveness of the cognitive rehabilitation program on social cognition has been sustained even after a two-month follow-up period.

The method of generalized estimating equations was employed to explore the research inquiries surrounding whether the cognitive rehabilitation program impacts the facets of social cognition (including initial and realistic levels of ToM) in children aged 6 to 11 years with ASD. The results of this analysis are presented in Table 5.

According to Table 5, the trajectory of variations in the initial level and the realistic level (corresponding to the first and second levels of ToM) over time in the experimental group, in comparison to the control group, has demonstrated a significant increase of 3.08 and 0.96 units, respectively (P<0.001). Consequently, it is plausible to deduce that the Cogniplus cognitive training program has influenced the initial and realistic ToM (the first and second levels of ToM) in children aged 6 to 11 years of ASD.

Discussion

The primary objective of this study was to assess the effectiveness of the Cogniplus cognitive training program on social cognition and ToM levels in children aged 6 to 11 years diagnosed with ASD. The initial finding of the research suggests that the Cogniplus cognitive training program enhances social cognition in children within this age group who have high-functioning ASD. This outcome aligns with the findings reported by Darvishi et al. [11], and Yaghini et al. [12], further supporting the positive impact of such cognitive training programs on social cognition in children with ASD. Accordingly, the Cogniplus cognitive training program places a significant emphasis on instructing emotion recognition and enhancing imitation skills in children diagnosed with ASD. The acquisition of these skills aids in the learning of self-regulation strategies for children on the autism spectrum, who may exhibit slower development in these areas. As a consequence, the enhancement of social cognition, particularly in terms of ToM levels, is observed. In line with the theory of disrupted mirror neurons, impairment in the mirror neuron system of the brain may impede communication, imitation abilities, and the advancement of ToM in children with ASD. Engaging in the exercises and tasks incorporated in the Cogniplus cognitive training program has been suggested to ameliorate the functioning of mirror neurons [12], thereby facilitating the child’s capacity to engage in appropriate imitation activities. This improvement in imitation skills can contribute to the child’s ability to comprehend and interpret the emotions and sentiments of others, ultimately fostering the growth and evolution of their social cognition.

The second key finding of the study suggests that the Cogniplus cognitive training program has effectively altered and enhanced both the initial ToM (level one) and the realistic ToM (level two) in children aged 6 to 11 years diagnosed with ASD. This result is in line with the outcomes of a previous study [34]. Existing research indicates that engaging in movement games [35] and participating in exercises focused on response inhibition and working memory can positively influence the enhancement of the first and second levels of ToM. Given that the Cogniplus cognitive training program incorporates movement games designed to bolster working memory and exercises targeting response inhibition, as shown in a study [36], these movement-based activities enhance cognitive flexibility in children. This enhanced cognitive flexibility plays a pivotal role in the development of ToM. Accordingly, the ability of individuals to dissect components of a unified whole and identify various emotions and feelings necessitates a robust active memory capacity. Therefore, engaging in movement exercises has improved active memory capacity and visual-spatial memory, consequently leading to enhancements in both the initial and realistic levels of ToM [36].

One of the findings from the research indicated that undergoing the cognitive rehabilitation program did not have a significant impact on the advanced ToM (third level) in children aged 6 to 11 years diagnosed with ASD. These results are in line with findings from previous studies [33, 37] and are contradictory to the outcomes of two other studies [38, 39]. According to Sayfi’s study [37], interventions and training based on ToM may only enhance certain levels of ToM in children with ASD. The research by Mansuri et al. [40] revealed that children with ASD possess a ToM, albeit in a rudimentary and preliminary form. These findings are at odds with some earlier studies [38, 39] suggesting that children with ASD can attain the third and advanced level of ToM. Hence, the children in the present study may belong to a subgroup of individuals with ASD who exhibit different cognitive abilities and IQ levels compared to those examined in previous research. In the recent explanation provided, it is highlighted that the tasks associated with the second level of ToM are more challenging in comparison to those linked to the first level. Therefore, tasks at the third level of ToM are more intricate. The advanced skills required for ToM surpass the comprehension needed for the basic level tasks and necessitate an understanding of complex cognitive, epistemic, and emotional states. In essence, the third-level tasks involve interpreting mental states in situations characterized by uncertainty or lack of transparency, demanding multiple inferences to be drawn. Due to these heightened complexities, children with ASD may struggle to complete tasks at this level of ToM. As per Ganea’s perspective [41], advanced ToM skills play a crucial role in facilitating sophisticated social interactions and academic achievements.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of the current research, it was observed that social cognition, including the overall score of ToM and its first and second levels, improved in children with ASD following their participation in the Cogniplus cognitive training program. Furthermore, this improvement was sustained even after two months post-training. Cognitive training program are designed to retain cognitive functions through practice, adaptation, and implicit learning. These programs are rooted in the concept of brain plasticity and self-repair, where engaging in exercises that stimulate fewer active areas of the brain can lead to stable synaptic changes in those regions. This, in turn, can result in enhanced cognitive functions.

The cognitive training program, such as Cogniplus, operates on the principles of information processing, providing individuals with feedback on their abilities and self-efficacy. By engaging individuals in exercises and computer activities, the program can foster interest and motivation, encouraging continued participation. Therefore, incorporating the exercises used in the Cogniplus program as part of training for children with ASD could be beneficial. The findings from the research may be of interest to special education specialists and educational program designers, enabling them to develop educational programs that incorporate computer games. These programs can enhance motivation for educational activities among children with ASD and cater to the individual needs of each child, allowing for personalized learning experiences based on their abilities. Given that ASD is associated with significant impairments in social cognition functions, particularly ToM, as well as challenges in communication and social interaction, parents and educators must provide a supportive and enriching environment for children with ASD from the early stages of diagnosis. By offering appropriate training to nurture the hidden mental and cognitive talents of these children, the severity of the impairments caused by ASD on social cognition functions can be mitigated. This approach can help individuals with ASD develop and thrive in their social interactions and communication skills.

Study limitations

The research study outlined several significant limitations that could impact the generalizability and robustness of the findings. These limitations include the use of a non-random and limited sampling method, the absence of multiple assessment tools for evaluating social cognition, the inability to compare experimental and control groups based on gender and age variables, and the lack of IQ measurement among study participants. Furthermore, relying solely on parent reports through an autism spectrum screening questionnaire may restrict the generalizability of the results. To address these limitations and enhance the validity of future research efforts, it is recommended to employ random sampling methods that encompass both genders and a wider age range. Additionally, measuring the IQ levels of children with ASD, utilizing multiple tools for assessing social cognition and ToM, and moving beyond sole reliance on parent reports can contribute to more comprehensive and accurate results regarding the efficacy of cognitive training programs like Cogniplus on social cognition in children with disorders. Moreover, extending the follow-up period post-intervention can offer insights into the long-term effectiveness of cognitive training programs in strengthening social cognition and ToM dimensions in children with ASD. This extended evaluation period can help determine whether the benefits of such interventions persist over time.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research has been approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.063). To comply with ethical considerations, the objectives of the research were fully informed to the officials of the Noyan Rehabilitation Center and parents of children with ASD. After obtaining written consent from mothers, they were assured that the information obtained from the questionnaires would remain confidential. Their children’s participation in the research will not involve any losses and children who did not want to continue cooperation could withdraw from the research. While paying attention to the mental states and fatigue of children, efforts were made to respect their dignity and human rights during the research.

Funding

This article is a part of the master’s thesis of Zahra Tajik, approved by Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Zahra Tajik, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi and Marjan Poshtmashhadi; Methodology and data analysis: Zahra Tajik, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi and Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi; Validation and sources Zahra Tajik, Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi, Marjan Poshtmashhadi and Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi; Writing the original draft: Zahra Tajik and Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi; Visualization, review and editing: Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi; Supervision: Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi, Marjan Poshtmashhadi and Razieh Bidhendi Yarandi; Project management: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors hereby express their gratitude to the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, and Welfare Organization in Tehran City, Iran and the officials of the Noyan Rehabilitation Center in Shahr-e-Ray City, Iran.

References

- Maenner MJ. Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years—Autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2020. MMWR. Surveillance Summaries. 2023; 72(2):1-14. [Link]

- Hassannattaj F, Abbasali Taghipour Javan A, Pourfatemi F, Aram S. [Screening and epidemiology of autism spectrum disorder in 3 to 6 year-old children of kindergartens supervised by Mazandaran Welfare Organization (Persian)]. Journal of Child Mental Health. 2020; 7(3):205-18. [DOI:10.52547/jcmh.7.3.17]

- Pino MC, Masedu F, Vagnetti R, Attanasio M, Di Giovanni C, Valenti M, et al. Validity of social cognition measures in the clinical services for autism spectrum disorder. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020; 11:4. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00004] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Fernández M, Mollinedo-Gajate I, Peñagarikano O. Neural circuits for social cognition: implications for autism. Neuroscience. 2018; 370:148-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.07.013] [PMID]

- Flavell JH. The development of knowledge about visual perception. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation. 1977; 25:43-76. [PMID]

- Martinez G, Mosconi E, Daban-Huard C, Parellada M, Fananas L, Gaillard R, et al. "A circle and a triangle dancing together": Alteration of social cognition in schizophrenia compared to autism spectrum disorders. Schizophrenia Research. 2019; 210:94-100. [DOI:10.1016/j.schres.2019.05.043] [PMID]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Minshew NJ, Mazefsky CA, Eack SM. Perception of life as stressful, not biological response to stress, is associated with greater social disability in adults with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2017; 47(1):1-16. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-016-2910-6] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lei J, Ventola P. Characterising the relationship between theory of mind and anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorder and typically developing children. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2018; 49:1-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.rasd.2018.01.005]

- Fathabadi R, Bakhtiarvand M, Hajiali P. [The effectiveness of cognitive computer games on the working memory of children with high functioning autism disorder (Persian)]. Educational Technologies in Learning. 2020; 3(10):113-24. [DOI:10.22054/jti.2020.44948.1280]

- Montes CPG, Fuentes AR, Cara MJC. Apps for people with autism: Assessment, classification and ranking of the best. Technology in Society. 2021; 64:101474. [DOI:10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101474]

- Darvishi S, Al Hosseini KA, Rafiepoor A, Dortaj F. [The effectiveness of a music-based developmental relation therapy program on promotion of mothers-child relationship of children with autistic spectrum disorder (Persian)]. Psychology of Exceptional Individuals. 2022; 12(45):89-112. [DOI:10.22054/JPE.2021.59264.2293]