Volume 25 - Special Issue

jrehab 2024, 25 - Special Issue: 702-725 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Amini B, Hosseini S A, Pishyareh E, Bakhshi E, Haghgoo H A. Designing an Exercise Protocol to Improve Impulsivity Control in Children With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Pilot Study. jrehab 2024; 25 (S3) :702-725

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3400-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3400-en.html

Behzad Amini1

, Seyed Ali Hosseini2

, Seyed Ali Hosseini2

, Ebrahim Pishyareh *3

, Ebrahim Pishyareh *3

, Enayatollah Bakhshi4

, Enayatollah Bakhshi4

, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo1

, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo1

, Seyed Ali Hosseini2

, Seyed Ali Hosseini2

, Ebrahim Pishyareh *3

, Ebrahim Pishyareh *3

, Enayatollah Bakhshi4

, Enayatollah Bakhshi4

, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo1

, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo1

1- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,eb.pishyareh@uswr.ac.ir

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 2533 kb]

(1279 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4806 Views)

Full-Text: (1207 Views)

Introduction

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with a prevalence of 7.2% is one of the most common disorders of school-aged children [1]. ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that is identified through symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity, which occur stably for 6 months in at least two areas of life and these symptoms should be observed before the age of 7 years [2]. One of the important complications of ADHD is that these children are more at risk of academic achievement disorders than others [3].

According to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition, impulsivity is a main diagnostic feature in ADHD [2], which many experts consider as the core of all symptoms of this disorder [4]. As the root cause of ADHD, deficits in control of irritability are also attributed to it and are considered to be the foundation of behavioral disorders [4، 5]. In children, hyperactivity and impulsivity are often manifested as the inability to wait in different situations, such as the tendency to interrupt others during a conversation or to answer before the end of a question [5]. Children and adolescents with ADHD show relatively more impulsive decision-making than children and adolescents without ADHD [6]. Even the coordination disorder and the amount of the center of gravity fluctuations in these children can also be considered to be in line with the disturbance in control and impulsivity in them [7، 8].

Self-regulation and self-control of attention and impulse (emotion and behavior) are essential components for a person’s adaptation, required as a prerequisite for a person’s daily activities, and both of them work completely intertwined and inseparable [9]. Impulsivity, defined as acting without foresight, is a component of several psychiatric disorders, including ADHD, mania, and substance abuse [10]. To investigate the underlying mechanisms of impulsive behavior, the nature of impulsivity needs a practical definition that can be used as a basis for empirical investigation. Impulsivity has a complex and multidimensional structure. The main components of impulsivity can be considered cognitive, and motor, along with a lack of planning. The motor component is defined as action without thinking, the cognitive component as quick cognitive decision-making, and the lack of planning component as a disregard for the future. Therefore, in designing impulsivity control exercises, the presence of both motor and cognitive indicators simultaneously in one exercise can be considered a special advantage [11]. In this context, epidemiological studies show a decrease in the prevalence of impulsivity with increasing age, one of the reasons for which can be the growth of different areas and the development of the network of the brain as a result of aging [12].

Some symptoms and problems may be caused by other primary disorders that overlap with ADHD, such as movement perception disorder, which has a strong relationship with ADHD [13]. Studies show that 50% of all children with ADHD have some kind of deficit in their motor performance [4].

On the other hand, executive function deficits are also observed in this category of children [14], which causes impairment in important aspects of learning, such as motivation, attitude toward learning, or persistence, along with ADHD symptoms [3]. Executive functions have more power than typical symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in predicting the learning behaviors of children with ADHD. These executive functions enable us to perform law-based behaviors. In ADHD children, three areas of executive functions show more impairment, which include inhibition or control of behavior, cognitive flexibility and working memory. Working memory refers to the ability of brain systems to temporarily store essential data and manipulate them to give an appropriate response [15]. Inhibition means inhibiting an overlearned, competitive, or disruptive response [16]. According to Barkley, children with ADHD are more impaired in inhibiting the preventive response. Anticipatory response inhibition is an indication of executive control that allows individuals to adapt to a changing environment. This ability is defined as the capacity to withhold a persistent response that is no longer relevant [17]. Cognitive flexibility refers to the ability to switch the flow of thought between two different topics or to think about several topics at the same time. This ability can show itself in response to various and unexpected conditions [4، 18، 19].

Scientific findings highlight the importance of including executive function development programs as the main priority from a young age and in the school environment for ADHD children to strengthen learning behaviors [3]. Therefore, according to the pattern of brain networking in the development of subcortical circuits during the growing age as a developmental norm neural mechanism for reducing impulsivity [20], it is possible to strengthen the function of motor planning and improve the ability to delay decision making in the form of using the dual tasks paradigm as a suggested solution to improve executive function and inhibit impulsivity [21]]. Considering that impulsivity is considered an unplanned action [11], in the dual-task paradigm, it is possible to replace this feature with planned action. In the dual-task paradigm, performing mental tasks while performing physical functions can cause a decrease in the speed of gross physical functions; accordingly, simultaneous presentation of these tasks will be a challenge to develop the ability of the brain to control ADHD symptoms [22].

Another aspect of the disorder in ADHD children is the defects related to timing [23], rhythm disorders in these children include both understanding of circadian rhythm and awareness of time and movement rhythm [24]. This disorder has become the basis for the design of some exercises based on musical rhythm in ADHD children. By using and harmonizing auditory and movement rhythmic patterns, the benefits of rhythmic patterns can be used in the development of cognitive abilities of ADHD children [25]. Accordingly, computer games have been designed to improve the cognitive functions of ADHD children, and participation in them has improved performance in these children to some extent [26].

According to the literature, there is a one-dimensional view in the presentation of exercises in most of the studies, for example, in most of the exercises presented, either only movement patterns were used, or only educational and cognitive patterns were used, or, for example, only stimulations of certain areas of the brain that are disturbed in ADHD children have been considered or rhythm has been considered, and there is no comprehensive and holistic view of all cases. Therefore, it is possible to fill this serious gap by using the dual-task paradigm. So far, dual tasks have been used as a concept to explain the conditions of ADHD children and adults, it is possible to use the dynamic space of this concept to place different parts affecting the impulsivity of ADHD children, such as rhythmic motor parts, cognitive parts, and executive functions in the design of exercises.

According to past studies, the exercises have been presented with a one-dimensional, non-comprehensive view, without using the dual-task paradigm, and without paying enough attention to the role of executive function defects resulting in the impulsivity symptoms of ADHD children. In addition, in most studies, the level of cooperation and effectiveness of exercises and the possibility of their implementation in most places have not been considered. Therefore, considering these cases in the design of a package of interventional exercises can be the beginning of a path to eliminate this deficiency and gap. Therefore, in this study, the design of dual tasks involving motor skills and cognitive decisions simultaneously in ADHD children with impulsivity is discussed. In addition, this pilot study investigates impulsivity and other cognitive aspects, such as attention.

Materials and Methods

Exercise design

Considering that this study included designing exercises and their initial evaluation in terms of feasibility, it was conducted in a combined two sections, namely designing the exercises and evaluating of their feasibility in a pilot study.

ADHD is considered one of the most heterogeneous psychiatric disorders of children, and this causes the complexity and variety of treatments and interventions. The review of past studies indicates a great heterogeneity in the field of proposed interventions for this category of children. For instance, in a review study to examine the types of treatment related to ADHD, 23 different types of treatment have been stated, which indicates the complexity of the problem [27]. Studies have shown that Go/NoGo paradigms and other cognitive paradigms and drug therapy could not obtain a complete position in the field of impulsivity control, although they have been acceptable in other fields of symptoms of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity. Therefore, the necessity of providing an exercise package with rhythmic cognitive-motor characteristics as the foundation of interventions for a single and integrated approach in the rehabilitation of this group of children can solve the problem and be considered as a multi-dimensional solution.

Exercise design components in the present study

According to studies, physical activities are a strong moderator of gene effects that cause structural and functional changes in the brain and have a great impact on cognitive performance and health [28]. Animal studies and human studies have shown that after a period of physical training, the levels of several neurotrophic factors related to cognitive function, neurogenesis, angiogenesis, plasticity, and malleability increase [12، 29، 30]. According to previous studies, physical exercises can increase the participation of ADHD children and reduce their symptoms, at the same time, the principle of acceptance of exercises by the family and the ability to perform them at home has also been emphasized in the studies as a basic pillar in the proposed interventions.

If rhythmic movements are also used in the design of exercises, in addition to using the benefits of physical exercises, it is possible to benefit from the improvement of restraint abilities. Rhythm is the main feature of many human behaviors that are expressed through motor actions, such as clapping, walking, dancing and talking [31، 32]. Also, rhythm is useful for perception, because its inherent temporal predictability allows anticipation and preparation for future stimuli. Rhythm is important for a wide range of cognitive abilities, but reduced temporal acuity and precision caused by rhythm disturbances have been linked to difficulties in attention and language processing. In particular, people with ADHD show less accuracy in a variety of time-related tasks and rhythmic behaviors [33].

To clarify the nature of the rhythm deficit in ADHD, it is useful to distinguish between two types of rhythmic behavior. The first is the spontaneous production of rhythms generated internally by the motor system and the second is coordination with environmental rhythms, which involves intrinsic interactions between the sensory and motor systems. However, the relationship between the spontaneous production of motor rhythms and the synchronization of motor actions with external rhythms has not been sufficiently determined [34-36]. It has also been shown in studies that music significantly helps children maintain their long-term attention as well as the timed structure around their actions [37].

In designing the exercises, it was tried to pay attention to all three main parts of impaired executive function in ADHD, i.e. behavior control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory. For this purpose, the dual-task paradigm was used. In this paradigm, attention needs are increased and working memory and cognitive flexibility are challenged. Both physical and cognitive exercises were used to design exercises based on past studies. In the movement part, by presenting a simple rhythmic sound pattern to the child and his effort to maintain, control, and internalize it, it was tried to improve the rhythmic abilities to reduce the inhibition disorders of ADHD children.

The use of an external sound rhythm and movement rhythm to synchronize and coordinate sensory and understanding inputs with movement outputs can be the basis for improving the child’s restraining abilities in behavioral patterns. Overall, the review of these studies showed that physical exercises can improve emotion regulation, behavioral problems, ADHD symptoms and social skills [38].

In this protocol, the use of working memory functions as well as delayed decision-making can lead to the expansion of neural networks that develop executive functions in the fields of inhibition and planning. For this purpose, a proposed package consisting of three areas was considered.

The initial design of the exercises was done based on the mentioned cases and using the results of the review of past studies, then it was discussed in the expert panel. The expert panel consisted of 25 specialists in the fields of occupational therapy, physiotherapy, neuroscience, speech therapy, and audiology, who were experts in related fields, such as ADHD, recognition of rhythmic patterns, dual-task paradigm, and design of clinical exercises. In this proposed package, in addition to the type of exercises, various aspects, such as timing, consistency, attractiveness, level of difficulty and the process of arranging the exercises were examined and the final result was approved by all the experts of the expert assembly after several amendments and obtaining consensus.

The design of exercises based on the above findings in the paradigm of dual tasks and using rhythmic physical movements and simple cognitive exercises that started in the occupational therapy department of the University of Rehabilitation and Social Health Sciences in 2022 with the review of studies and the entire work process until the final version was obtained as the recommended training package took six months. The steps of this process are explained with detailed explanations as follows.

Reviewing and extracting the infrastructure factors of exercises from other studies and reviewing the results of previous interventions

In the review of previous studies related to physical and rhythmic exercises in the field of ADHD children, articles published in 2010 with the keywords “ADHD,” “dual task,” “rhythm,” “physical exercise,” and “impulsivity” were reviewed. Based on the extracted information, the type of exercises, the stages of the training sessions, the age group of the participants in the intervention, as well as the motivators were formed in the initial proposed package.

In the previous studies, which were based on the pattern of using physical exercises or dual tasks and rhythmic patterns, various exercises, such as jogging, aerobics, running, water aerobics, treadmill, high-pressure physical activity that makes the child breathless, stationary bicycle, sports, such as tennis on the table, games and rhythmic dance, balance games and virtual games such as Kinect and Xbox have been used. In terms of type of exercise, the most frequent among different studies is related to aerobic exercises. In examining the age of children participating in studies between the ages of 6 and 16 years, most of the studies were focused on themselves. The number of sessions in some studies was only one session; however, the exercises were performed for a minimum of 6 weeks and a maximum of 20 weeks. The number of sessions per week was between three and six sessions and the duration of one session was between 30 and 90 min [39-48].

In the reviewed studies, various motivators, such as verbal incentives, chocolates, toys, physical gestures, economic tokens and sports such as football, basketball, and handball were used. Overall, reviewed studies showed that physical exercises can improve emotion regulation, behavioral problems, ADHD symptoms, and social skills.

The integration of physical and cognitive exercises in the dual-task paradigm to control impulsivity has not been considered in reviewed studies, and usually, only one type of exercise was presented at each level and the variety and taste of the child were not considered. Likewise, in many studies, continuing exercises at home were either not possible or not mentioned as part of the treatment process. Also, performing movements rhythmically based on an auditory cue or sign has been less investigated in these studies, or the use of auditory systems, especially the coordination of body movements with a beat, has not been used and neglected.

The initial design of the exercises and the formation of an expert panel to check the theoretical compatibility of the various dimensions of the exercises In the beginning, the group was provided with the package of preliminary proposed exercises along with a complete description of the process of the sessions and phases and the implementation of the exercises and a questionnaire, including questions about the possibility of performing the exercises in the clinic environment, having rhythmic movements, being in the paradigm of dual tasks. In other parts of this questionnaire, timing, attractiveness, compatibility, and exercises were questioned.

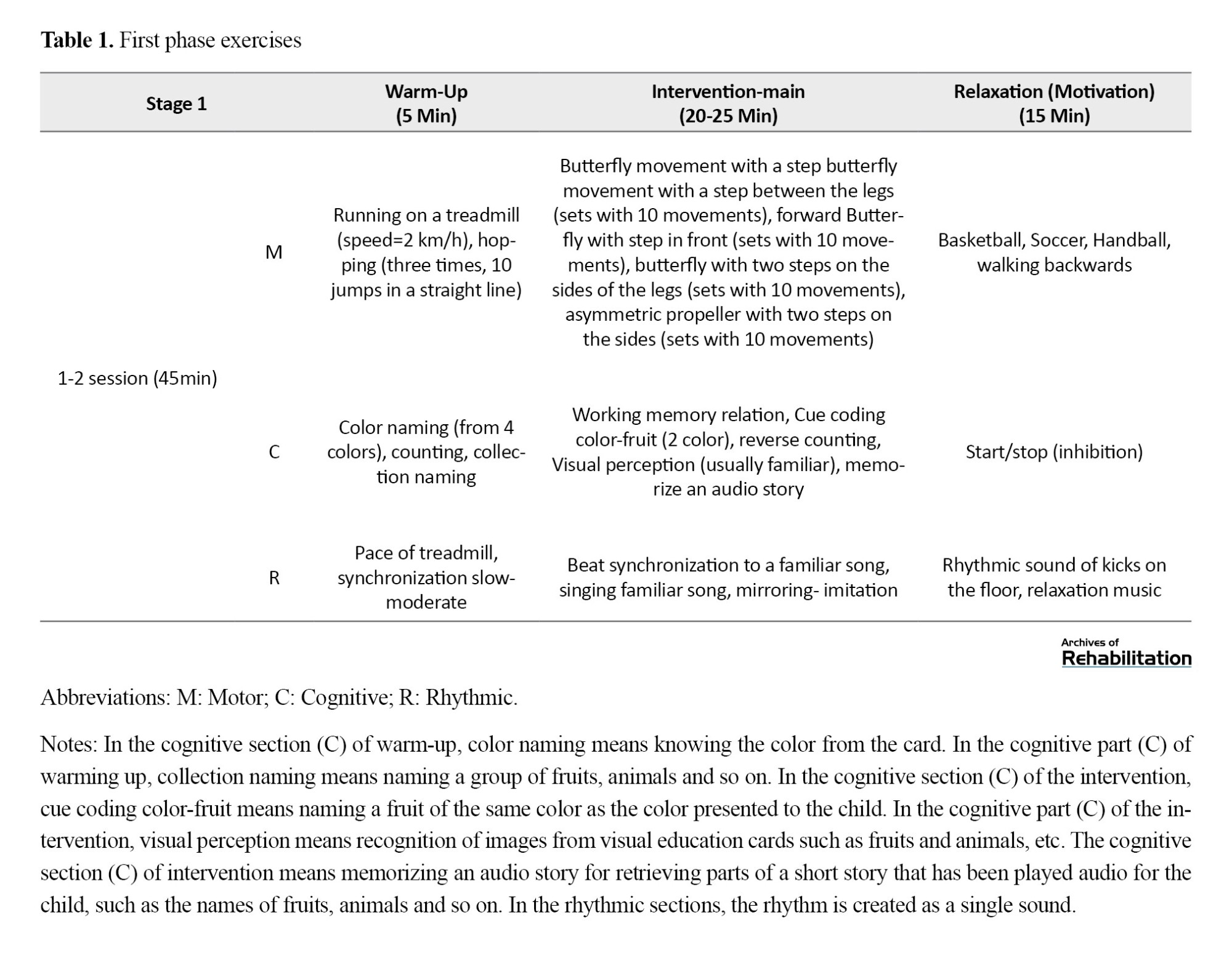

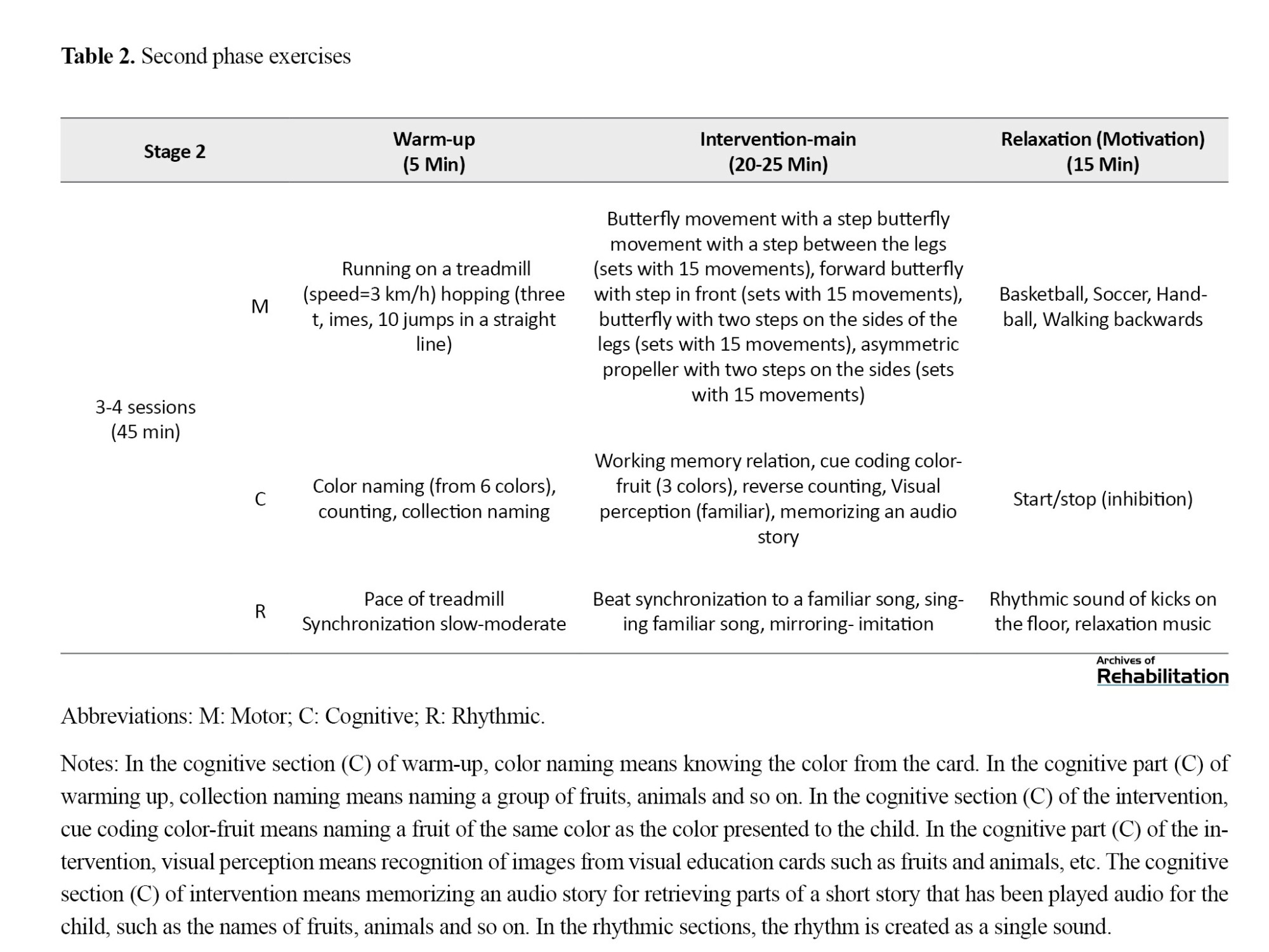

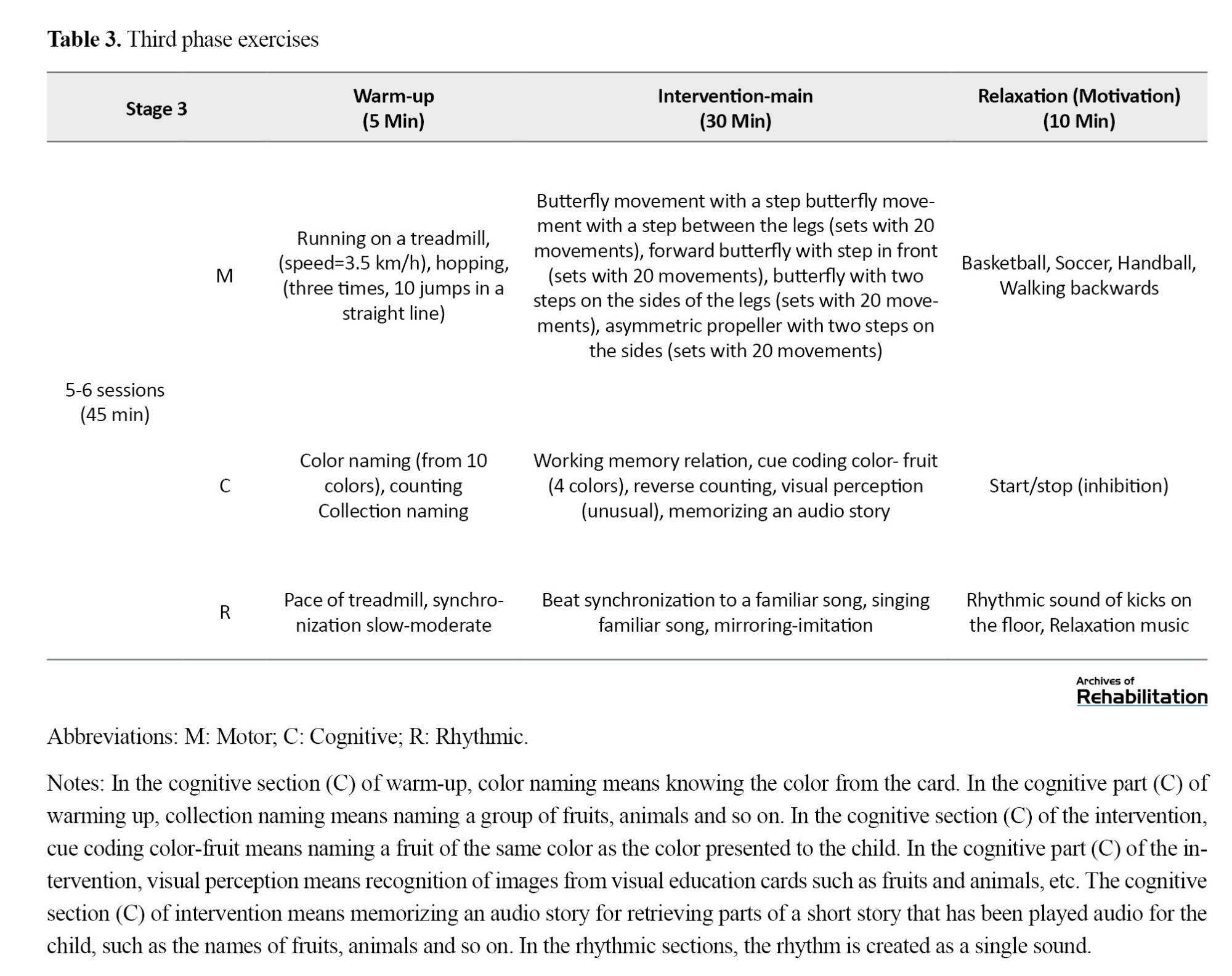

Finally, by applying the opinions of the expert panel members, the final number and time of the exercises and the prioritization and layout of the exercises were determined. In the final proposed exercise package, each phase consists of two sessions, each session is 45 min and includes three different parts, namely warm-up, intervention, and relaxation. In each of these sections, according to the child’s level and their performance in the evaluations, some specific exercises were presented to them, and the child was asked to perform a combination of motor-cognitive-rhythmic exercises.

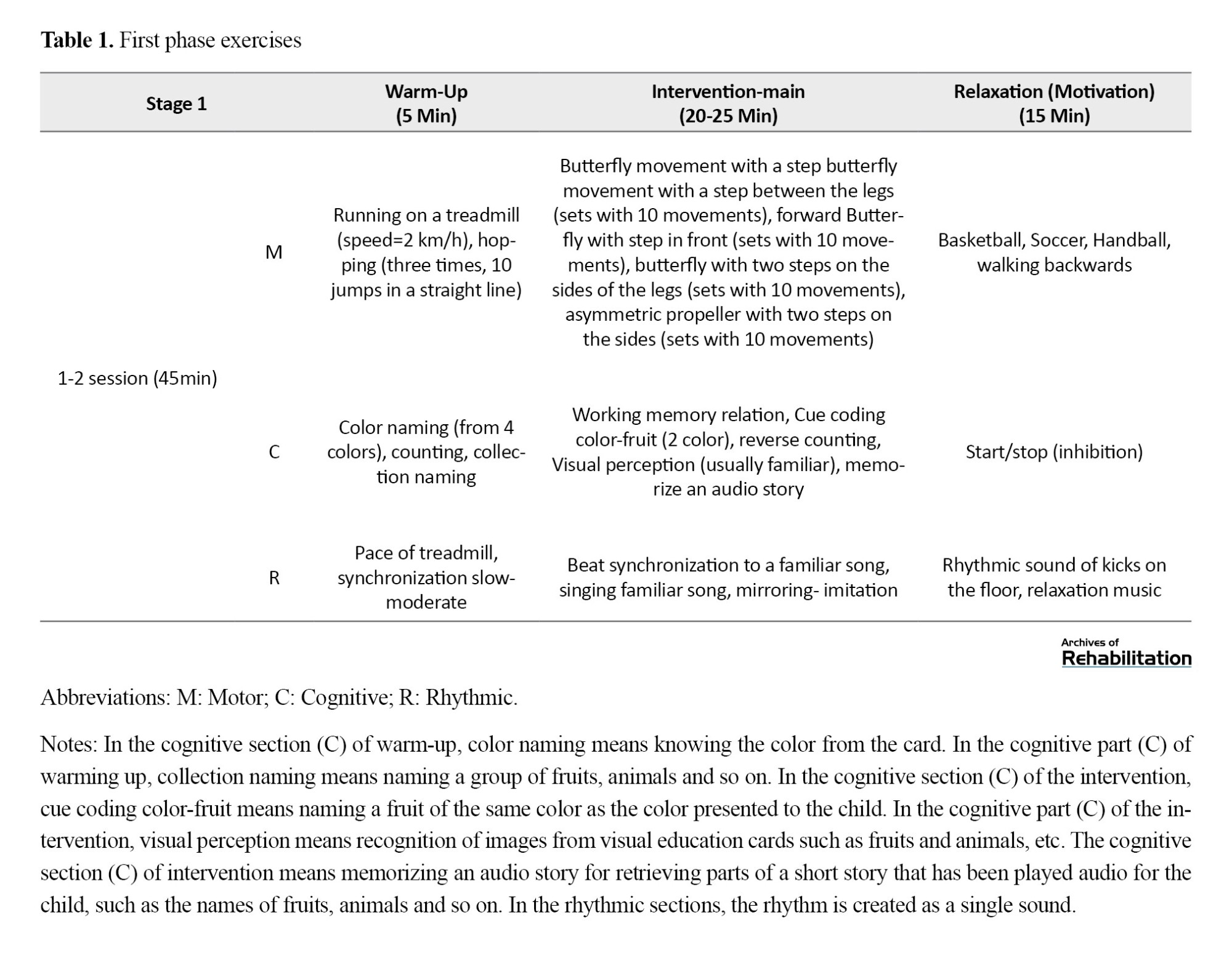

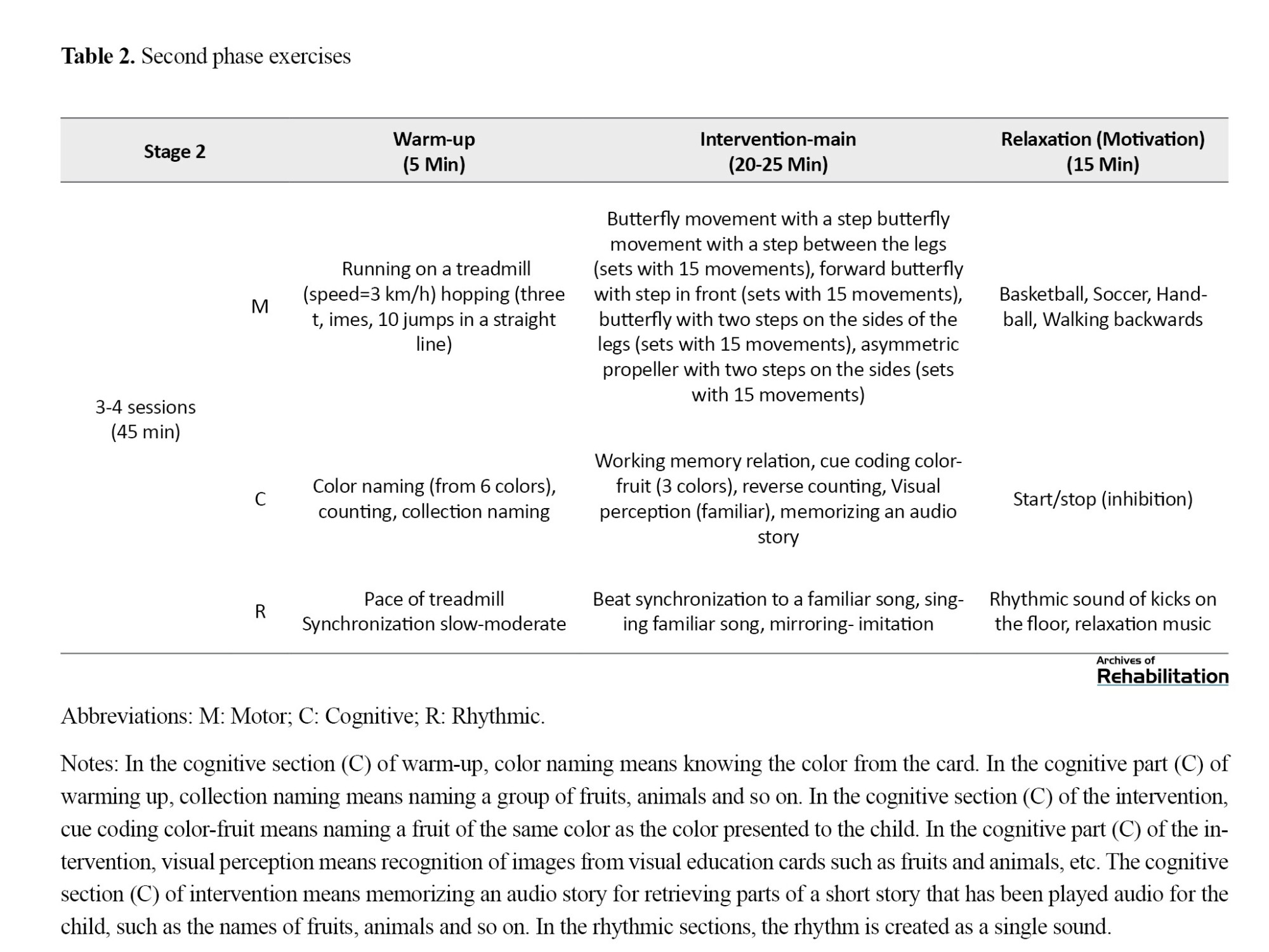

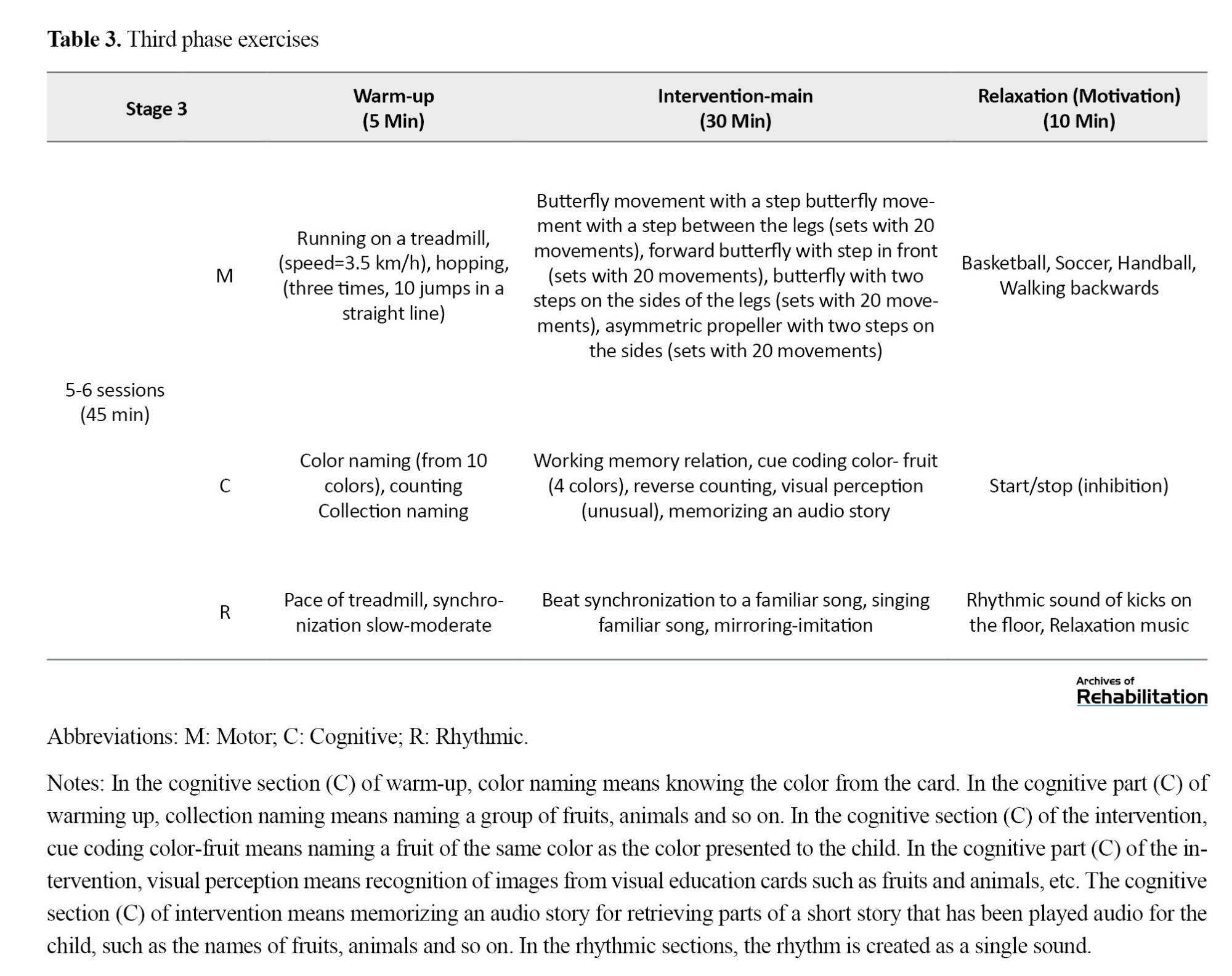

The final exercise package is in the following order in three phases (Tables 1, 2 and 3) of successive progress.

Designing and implementation of a pilot study

Objectives of the pilot study

A pilot study was designed with a limited number of participants to investigate the feasibility of the proposed exercise package and its use as a codified intervention solution for ADHD children and its effect on the indicators of prudence, response inhibition, and attention.

Study participants

The target population in this study were children with ADHD aged 6 to 9 years in Tehran, and four children with ADHD based on DSM-5 diagnostic symptoms diagnosed by a child and adolescent psychiatrist participated in this study to implement a pilot study. The inclusion criteria for the pilot study include: Having ADHD diagnostic symptoms based on DSM-5, age 6 to 9 years, being accepted in the school entrance assessment test, having impulsivity based on the impulsivity items of the Connors short form of parents, not having a physical disability, not having a history of attending class. The rhythmic movements were like (dance and gymnastics). Exclusion criteria included: Changes in drug therapy and initiation of new treatment during the study process, as well as effective family events such as divorce, immigration, death of one of the main family members, and non-participation in all intervention sessions.

Study measurements

The integrated visual and auditory (IVA-2) test was used as a specialized test to diagnose ADHD symptoms in this study. The IVA-2 is a type of continuous performance testing, which is used to help diagnose ADHD and determine indicators of attention and concentration. The IVA-2 test separates 5 types of attention, including focused attention, sustained attention, selective attention, divided attention, and transfer and displacement of attention in both visual and auditory areas. It takes 20 min to run this computerized diagnostic tool. The first 2 min are for familiarizing yourself with the test, 16 min for tests, and the last 2 min for assessing the validity of the test, which is called the relaxation phase.

Study procedure

After selecting the children with ADHD based on the criteria for entering the study, before the implementation, their parents were informed about the training process and study objectives and completed the consent form. At first, the IVA-2 test was performed, and the examiner was unaware of the type of exercises and intervention program. Then, for each of the clients, for three weeks (three phases) and two sessions every week, a total of six sessions of exercises were performed in the environment of one of the occupational therapy clinics in Tehran City, Iran. The first two sessions of the first phase exercises, the middle two sessions of the second phase exercises, and the last two sessions of the third phase exercises were used. For this purpose, every week’s exercise design was given to the children’s families in printed form at the beginning of that week. In the end, the IVA-2 test was performed again for the participating children. In the end, it was explained to the parents, and the family’s questions were answered by the experts.

Results

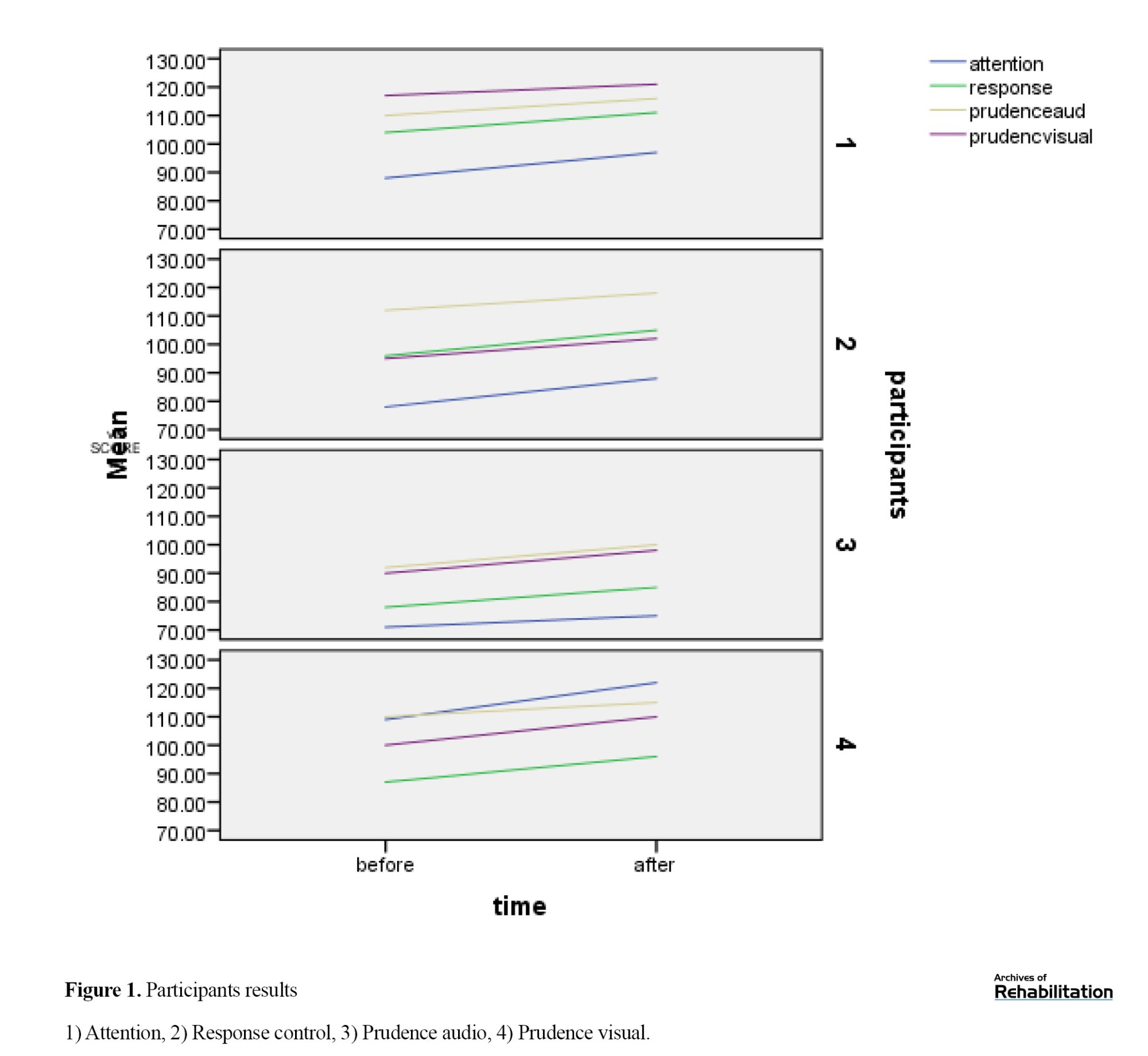

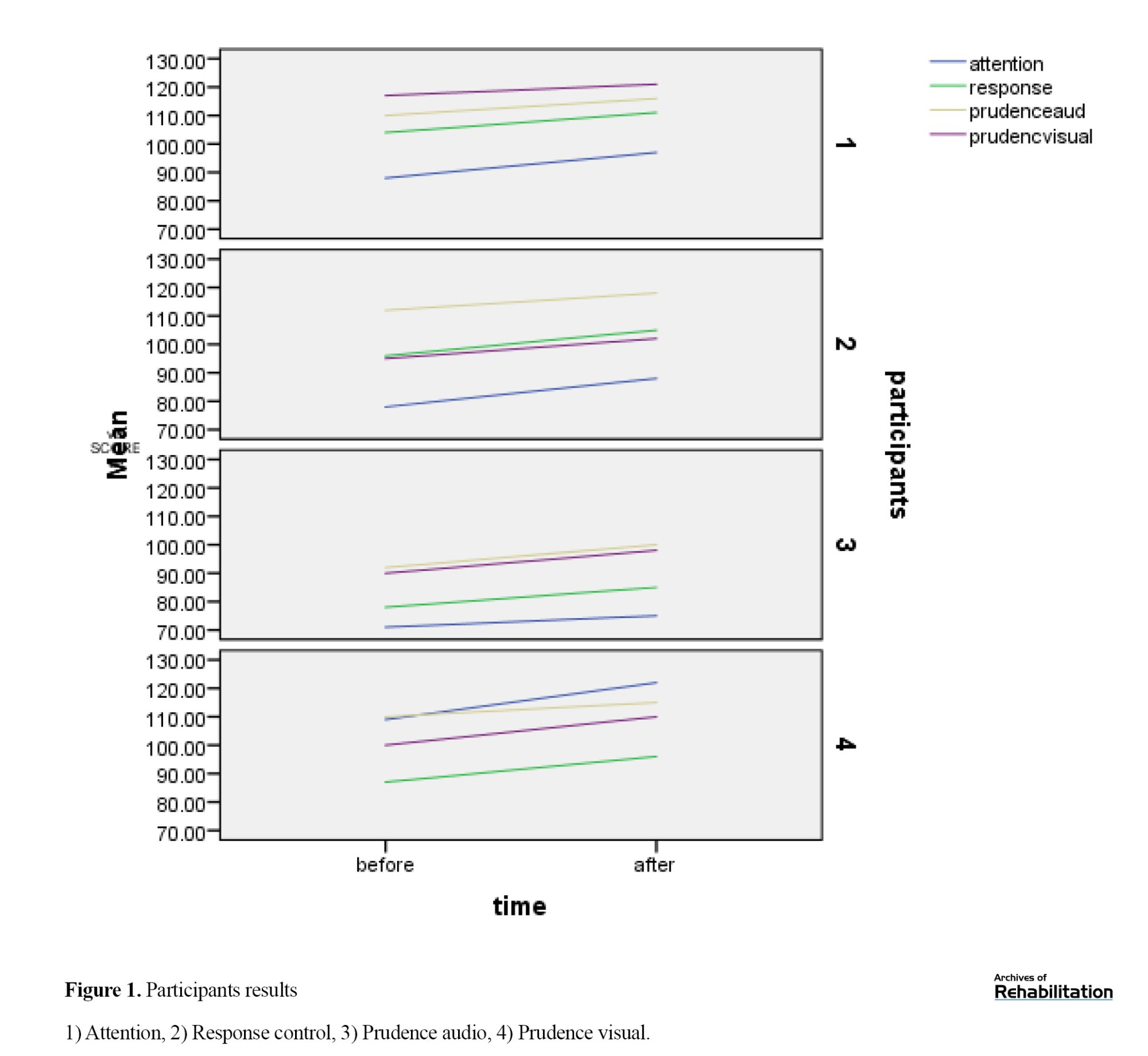

Based on the design objectives of the pilot study, the possibility of implementing the exercises was approved. These exercises can be used in rehabilitation clinics and for ADHD children. The cooperation of children and families was also reported as suitable. The results were analyzed in the indicators of attention, response control, prudence audio, and prudence visual, which are shown in Figure 1. The results indicated positive changes in all four participants in indicators related to impulsivity, i.e. prudence and response control. In the attention section, the results showed positive changes in all four participants. Due to the number of participants the pilot nature of the study, and the lack of comprehensive and multiple evaluations, these results can only be a reason for the foundation of extensive randomized clinical intervention trial research. It is not considered clinically generalizable to ADHD children.

Clinical observations

During the study, interesting aspects were observed in the form of additional information, which included the following items:

1. All the participants attended the sessions with great enthusiasm from the second session and after familiarizing themselves with the type of exercises. According to the report, three families reported that the children were waiting to come to the rehabilitation clinic even in the interval between two consecutive sessions to participate in the next session.

2. In the training phases, all children show better participation in the second session of each stage than in the first session.

3. One of the children sometimes reported feeling pain in the area of the ankles and soles of the feet, which was referred to an orthopedic specialist, and the cause was reported to be improper indoor flooring. Suitable flooring for use at home was provided to the participants.

4. According to the reports of two families, the implementation of indoor exercises had improved the parent-child relationship to a large extent.

5. Three families reported that the child has developed a better sleep routine at night and the day after training.

Discussion

This package of proposed interventional exercises considered two aspects as follows: 1) Using rhythm and movement coordination with external music (paying attention to the external stimulus) while performing movement exercises and aligning in harmony with it and, 2) Using dual activity, including motor-cognitive tasks combined with the ability to perform fully by ADHD children. In the preliminary research, two goals were pursued, which were to investigate the clinical feasibility of these exercises and identify the problems during the exercises and second, to examine their initial effect on impulsivity indicators. The initial results indicated that the proposed package could achieve a high implementation capability and all four children participating in the pilot could easily handle the exercises and welcomed this challenge with great enthusiasm after the first session of each phase They showed enthusiasm and interest to attend again and perform exercises of this type. Also, noticeable changes occurred in the fields of response control, attention, and prudence. According to the results of previous studies, such as the research conducted by Rapp and Su [34] in emphasizing the use of movement rhythm and its homogeneity with environmental rhythmic sequences, the occurrence of these changes was expected because many researchers found the underlying cause of hyperactivity and impulsivity. In this group of children, they know the function of the anterior cingulate and motor planning areas in areas 6 and 32 Brodmann areas of the cerebral cortex and the role of these areas in planning and coordinating rhythm and movement sequences and targeting movements according to specific patterns can be considered to some extent justify the noticeable changes that have occurred [49]. Also, based on Mostofsky’s comments in describing the interactive and reciprocal relationship between movement and cognitive process, as well as noticeable changes in previous research reports on the application and use of dual motor tasks, these cases can be considered as possible reasons for these changes [50، 51]. Perhaps according to the results of the side findings and the reports of the families about the high enthusiasm and cooperation of the participants in this proposed package, these things can be aligned with the research results in the field of using fun sports movement activities and favorite skillful movement training. Children know that it has created a double motivation to acquire movement skills in the activities that these children like and taste, which is one of the important reasons for the results.

Another issue that can be considered one of the advantages of this package is the simplicity of the proposed package and its inclusion of all three cognitive, movement, and rhythmic parts, as well as its innovative advantage in using listening functions. The results of several studies have also indicated the effect of using auditory rhythms in children with ADHD in motor control and improving attention functions [25، 26، 51]. Considering that rhythmic complexity can modulate neural and behavioral actions, the effect of rhythmic movement patterns in the obtained results can be interpreted following past findings [52].

The positive changes in the results of attention can also be taken into consideration by considering the use of external audio cues in exercises, which is the same feature of synchronizing selective attention with a specific external rhythm and melody (emphasized in previous studies) [53].

One of the important and reportable features of this proposed package is the possibility of doing it in children’s clinics, as well as the expansion and coordination of exercises at home. The motivation and interest of children to perform such exercises in the form of targeted activities and games in line with the improvement and strengthening of parents’ relationship with participants and the willingness and cooperation of families to participate in the training sessions of this proposed package have also been among the possible basic causes of changes.

The possible reason for the high willingness and cooperation of families to participate in the training sessions of this proposed package can be attributed to excessive caution toward the follow-up of drug treatments and avoiding its possible side effects. When performing the designed exercises, the child will experience a higher level of executive functions in the form of motor challenges, and with greater ability in the fields of response control and working memory, it is expected that he will show more ability in controlling the symptoms of impulsivity. Considering that this study is only a pilot study and the statistical results are not generalizable to use the exercise package as a treatment, and it is only the beginning of a research process that requires additional research. Another limitation of this study is the impossibility of directly monitoring the way exercises are performed at home, which requires further investigation and planning in this field in future designs.

Conclusion

Considering previous studies and basic science information in this field about the impairment in the performance of ADHD children and the essential role and serious impact of impulsivity of these children on all their functional areas and the existence of rhythm and control disorders and based on clinical findings about the effectiveness of interventions Physically, the results of the designed exercise package can be accepted on the symptoms of ADHD. In addition, the possibility of implementation and its attractiveness and acceptability by children and parents can be confirmed and used in future studies. This proposed package covers a larger field of ADHD children’s functions and provides wider challenges for the child in line with the complexity of impulsivity symptoms in the context of the dual tasks paradigm.

Future study recommendations:

Examining and redefining the duration of sessions the number of sessions and their timing should be done. Designing a randomized controlled trial study to implement this package using more samples and accurate and reliable multiple assessment tools to check the impact and durability of the results after the follow-up period and compare it with existing approaches in the rehabilitation of ADHD children in the form of research, using several test and control groups is suggested. Examining the correlation coefficient between impulsivity changes with other ADHD symptoms and also with the satisfaction and quality of family life will be of study value. At the same time, it is recommended to implement this package in different cities and regions and different age ranges.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The parents of the children were fully aware of the study process, goals, and methods and signed a consent form for voluntary participation in the study. They were free to leave the study and were assured of the confidentiality of their information This study was approved by the ethics committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.207)

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Behzad Amini, approved by the Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Behzad Amini, Ebrahim Peshiareh, and Seyed Ali Hosseini; Methodology: Behzad Amini, Ebrahim Pishyareh, Seyed Ali Hosseini and Enayatullah Bakshi; validation, research and investigation: Behzad Amini, Ebrahim Peshyareh and Hojat Elha Haqgoo; data analysis: Behzad Amini and Enayatullah Bakshi; Writing the original draft: Behzad Amini; Review and editing: Behzad Amini and Ebrahim Peshyareh; Supervision and project management: Ebrahim Peshiareh and Seyed Ali Hosseini.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and their families as well as the clinical therapists for their cooperation and assistance in this study.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with a prevalence of 7.2% is one of the most common disorders of school-aged children [1]. ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that is identified through symptoms of inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity, which occur stably for 6 months in at least two areas of life and these symptoms should be observed before the age of 7 years [2]. One of the important complications of ADHD is that these children are more at risk of academic achievement disorders than others [3].

According to the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition, impulsivity is a main diagnostic feature in ADHD [2], which many experts consider as the core of all symptoms of this disorder [4]. As the root cause of ADHD, deficits in control of irritability are also attributed to it and are considered to be the foundation of behavioral disorders [4، 5]. In children, hyperactivity and impulsivity are often manifested as the inability to wait in different situations, such as the tendency to interrupt others during a conversation or to answer before the end of a question [5]. Children and adolescents with ADHD show relatively more impulsive decision-making than children and adolescents without ADHD [6]. Even the coordination disorder and the amount of the center of gravity fluctuations in these children can also be considered to be in line with the disturbance in control and impulsivity in them [7، 8].

Self-regulation and self-control of attention and impulse (emotion and behavior) are essential components for a person’s adaptation, required as a prerequisite for a person’s daily activities, and both of them work completely intertwined and inseparable [9]. Impulsivity, defined as acting without foresight, is a component of several psychiatric disorders, including ADHD, mania, and substance abuse [10]. To investigate the underlying mechanisms of impulsive behavior, the nature of impulsivity needs a practical definition that can be used as a basis for empirical investigation. Impulsivity has a complex and multidimensional structure. The main components of impulsivity can be considered cognitive, and motor, along with a lack of planning. The motor component is defined as action without thinking, the cognitive component as quick cognitive decision-making, and the lack of planning component as a disregard for the future. Therefore, in designing impulsivity control exercises, the presence of both motor and cognitive indicators simultaneously in one exercise can be considered a special advantage [11]. In this context, epidemiological studies show a decrease in the prevalence of impulsivity with increasing age, one of the reasons for which can be the growth of different areas and the development of the network of the brain as a result of aging [12].

Some symptoms and problems may be caused by other primary disorders that overlap with ADHD, such as movement perception disorder, which has a strong relationship with ADHD [13]. Studies show that 50% of all children with ADHD have some kind of deficit in their motor performance [4].

On the other hand, executive function deficits are also observed in this category of children [14], which causes impairment in important aspects of learning, such as motivation, attitude toward learning, or persistence, along with ADHD symptoms [3]. Executive functions have more power than typical symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity in predicting the learning behaviors of children with ADHD. These executive functions enable us to perform law-based behaviors. In ADHD children, three areas of executive functions show more impairment, which include inhibition or control of behavior, cognitive flexibility and working memory. Working memory refers to the ability of brain systems to temporarily store essential data and manipulate them to give an appropriate response [15]. Inhibition means inhibiting an overlearned, competitive, or disruptive response [16]. According to Barkley, children with ADHD are more impaired in inhibiting the preventive response. Anticipatory response inhibition is an indication of executive control that allows individuals to adapt to a changing environment. This ability is defined as the capacity to withhold a persistent response that is no longer relevant [17]. Cognitive flexibility refers to the ability to switch the flow of thought between two different topics or to think about several topics at the same time. This ability can show itself in response to various and unexpected conditions [4، 18، 19].

Scientific findings highlight the importance of including executive function development programs as the main priority from a young age and in the school environment for ADHD children to strengthen learning behaviors [3]. Therefore, according to the pattern of brain networking in the development of subcortical circuits during the growing age as a developmental norm neural mechanism for reducing impulsivity [20], it is possible to strengthen the function of motor planning and improve the ability to delay decision making in the form of using the dual tasks paradigm as a suggested solution to improve executive function and inhibit impulsivity [21]]. Considering that impulsivity is considered an unplanned action [11], in the dual-task paradigm, it is possible to replace this feature with planned action. In the dual-task paradigm, performing mental tasks while performing physical functions can cause a decrease in the speed of gross physical functions; accordingly, simultaneous presentation of these tasks will be a challenge to develop the ability of the brain to control ADHD symptoms [22].

Another aspect of the disorder in ADHD children is the defects related to timing [23], rhythm disorders in these children include both understanding of circadian rhythm and awareness of time and movement rhythm [24]. This disorder has become the basis for the design of some exercises based on musical rhythm in ADHD children. By using and harmonizing auditory and movement rhythmic patterns, the benefits of rhythmic patterns can be used in the development of cognitive abilities of ADHD children [25]. Accordingly, computer games have been designed to improve the cognitive functions of ADHD children, and participation in them has improved performance in these children to some extent [26].

According to the literature, there is a one-dimensional view in the presentation of exercises in most of the studies, for example, in most of the exercises presented, either only movement patterns were used, or only educational and cognitive patterns were used, or, for example, only stimulations of certain areas of the brain that are disturbed in ADHD children have been considered or rhythm has been considered, and there is no comprehensive and holistic view of all cases. Therefore, it is possible to fill this serious gap by using the dual-task paradigm. So far, dual tasks have been used as a concept to explain the conditions of ADHD children and adults, it is possible to use the dynamic space of this concept to place different parts affecting the impulsivity of ADHD children, such as rhythmic motor parts, cognitive parts, and executive functions in the design of exercises.

According to past studies, the exercises have been presented with a one-dimensional, non-comprehensive view, without using the dual-task paradigm, and without paying enough attention to the role of executive function defects resulting in the impulsivity symptoms of ADHD children. In addition, in most studies, the level of cooperation and effectiveness of exercises and the possibility of their implementation in most places have not been considered. Therefore, considering these cases in the design of a package of interventional exercises can be the beginning of a path to eliminate this deficiency and gap. Therefore, in this study, the design of dual tasks involving motor skills and cognitive decisions simultaneously in ADHD children with impulsivity is discussed. In addition, this pilot study investigates impulsivity and other cognitive aspects, such as attention.

Materials and Methods

Exercise design

Considering that this study included designing exercises and their initial evaluation in terms of feasibility, it was conducted in a combined two sections, namely designing the exercises and evaluating of their feasibility in a pilot study.

ADHD is considered one of the most heterogeneous psychiatric disorders of children, and this causes the complexity and variety of treatments and interventions. The review of past studies indicates a great heterogeneity in the field of proposed interventions for this category of children. For instance, in a review study to examine the types of treatment related to ADHD, 23 different types of treatment have been stated, which indicates the complexity of the problem [27]. Studies have shown that Go/NoGo paradigms and other cognitive paradigms and drug therapy could not obtain a complete position in the field of impulsivity control, although they have been acceptable in other fields of symptoms of attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity. Therefore, the necessity of providing an exercise package with rhythmic cognitive-motor characteristics as the foundation of interventions for a single and integrated approach in the rehabilitation of this group of children can solve the problem and be considered as a multi-dimensional solution.

Exercise design components in the present study

According to studies, physical activities are a strong moderator of gene effects that cause structural and functional changes in the brain and have a great impact on cognitive performance and health [28]. Animal studies and human studies have shown that after a period of physical training, the levels of several neurotrophic factors related to cognitive function, neurogenesis, angiogenesis, plasticity, and malleability increase [12، 29، 30]. According to previous studies, physical exercises can increase the participation of ADHD children and reduce their symptoms, at the same time, the principle of acceptance of exercises by the family and the ability to perform them at home has also been emphasized in the studies as a basic pillar in the proposed interventions.

If rhythmic movements are also used in the design of exercises, in addition to using the benefits of physical exercises, it is possible to benefit from the improvement of restraint abilities. Rhythm is the main feature of many human behaviors that are expressed through motor actions, such as clapping, walking, dancing and talking [31، 32]. Also, rhythm is useful for perception, because its inherent temporal predictability allows anticipation and preparation for future stimuli. Rhythm is important for a wide range of cognitive abilities, but reduced temporal acuity and precision caused by rhythm disturbances have been linked to difficulties in attention and language processing. In particular, people with ADHD show less accuracy in a variety of time-related tasks and rhythmic behaviors [33].

To clarify the nature of the rhythm deficit in ADHD, it is useful to distinguish between two types of rhythmic behavior. The first is the spontaneous production of rhythms generated internally by the motor system and the second is coordination with environmental rhythms, which involves intrinsic interactions between the sensory and motor systems. However, the relationship between the spontaneous production of motor rhythms and the synchronization of motor actions with external rhythms has not been sufficiently determined [34-36]. It has also been shown in studies that music significantly helps children maintain their long-term attention as well as the timed structure around their actions [37].

In designing the exercises, it was tried to pay attention to all three main parts of impaired executive function in ADHD, i.e. behavior control, cognitive flexibility, and working memory. For this purpose, the dual-task paradigm was used. In this paradigm, attention needs are increased and working memory and cognitive flexibility are challenged. Both physical and cognitive exercises were used to design exercises based on past studies. In the movement part, by presenting a simple rhythmic sound pattern to the child and his effort to maintain, control, and internalize it, it was tried to improve the rhythmic abilities to reduce the inhibition disorders of ADHD children.

The use of an external sound rhythm and movement rhythm to synchronize and coordinate sensory and understanding inputs with movement outputs can be the basis for improving the child’s restraining abilities in behavioral patterns. Overall, the review of these studies showed that physical exercises can improve emotion regulation, behavioral problems, ADHD symptoms and social skills [38].

In this protocol, the use of working memory functions as well as delayed decision-making can lead to the expansion of neural networks that develop executive functions in the fields of inhibition and planning. For this purpose, a proposed package consisting of three areas was considered.

The initial design of the exercises was done based on the mentioned cases and using the results of the review of past studies, then it was discussed in the expert panel. The expert panel consisted of 25 specialists in the fields of occupational therapy, physiotherapy, neuroscience, speech therapy, and audiology, who were experts in related fields, such as ADHD, recognition of rhythmic patterns, dual-task paradigm, and design of clinical exercises. In this proposed package, in addition to the type of exercises, various aspects, such as timing, consistency, attractiveness, level of difficulty and the process of arranging the exercises were examined and the final result was approved by all the experts of the expert assembly after several amendments and obtaining consensus.

The design of exercises based on the above findings in the paradigm of dual tasks and using rhythmic physical movements and simple cognitive exercises that started in the occupational therapy department of the University of Rehabilitation and Social Health Sciences in 2022 with the review of studies and the entire work process until the final version was obtained as the recommended training package took six months. The steps of this process are explained with detailed explanations as follows.

Reviewing and extracting the infrastructure factors of exercises from other studies and reviewing the results of previous interventions

In the review of previous studies related to physical and rhythmic exercises in the field of ADHD children, articles published in 2010 with the keywords “ADHD,” “dual task,” “rhythm,” “physical exercise,” and “impulsivity” were reviewed. Based on the extracted information, the type of exercises, the stages of the training sessions, the age group of the participants in the intervention, as well as the motivators were formed in the initial proposed package.

In the previous studies, which were based on the pattern of using physical exercises or dual tasks and rhythmic patterns, various exercises, such as jogging, aerobics, running, water aerobics, treadmill, high-pressure physical activity that makes the child breathless, stationary bicycle, sports, such as tennis on the table, games and rhythmic dance, balance games and virtual games such as Kinect and Xbox have been used. In terms of type of exercise, the most frequent among different studies is related to aerobic exercises. In examining the age of children participating in studies between the ages of 6 and 16 years, most of the studies were focused on themselves. The number of sessions in some studies was only one session; however, the exercises were performed for a minimum of 6 weeks and a maximum of 20 weeks. The number of sessions per week was between three and six sessions and the duration of one session was between 30 and 90 min [39-48].

In the reviewed studies, various motivators, such as verbal incentives, chocolates, toys, physical gestures, economic tokens and sports such as football, basketball, and handball were used. Overall, reviewed studies showed that physical exercises can improve emotion regulation, behavioral problems, ADHD symptoms, and social skills.

The integration of physical and cognitive exercises in the dual-task paradigm to control impulsivity has not been considered in reviewed studies, and usually, only one type of exercise was presented at each level and the variety and taste of the child were not considered. Likewise, in many studies, continuing exercises at home were either not possible or not mentioned as part of the treatment process. Also, performing movements rhythmically based on an auditory cue or sign has been less investigated in these studies, or the use of auditory systems, especially the coordination of body movements with a beat, has not been used and neglected.

The initial design of the exercises and the formation of an expert panel to check the theoretical compatibility of the various dimensions of the exercises In the beginning, the group was provided with the package of preliminary proposed exercises along with a complete description of the process of the sessions and phases and the implementation of the exercises and a questionnaire, including questions about the possibility of performing the exercises in the clinic environment, having rhythmic movements, being in the paradigm of dual tasks. In other parts of this questionnaire, timing, attractiveness, compatibility, and exercises were questioned.

Finally, by applying the opinions of the expert panel members, the final number and time of the exercises and the prioritization and layout of the exercises were determined. In the final proposed exercise package, each phase consists of two sessions, each session is 45 min and includes three different parts, namely warm-up, intervention, and relaxation. In each of these sections, according to the child’s level and their performance in the evaluations, some specific exercises were presented to them, and the child was asked to perform a combination of motor-cognitive-rhythmic exercises.

The final exercise package is in the following order in three phases (Tables 1, 2 and 3) of successive progress.

Designing and implementation of a pilot study

Objectives of the pilot study

A pilot study was designed with a limited number of participants to investigate the feasibility of the proposed exercise package and its use as a codified intervention solution for ADHD children and its effect on the indicators of prudence, response inhibition, and attention.

Study participants

The target population in this study were children with ADHD aged 6 to 9 years in Tehran, and four children with ADHD based on DSM-5 diagnostic symptoms diagnosed by a child and adolescent psychiatrist participated in this study to implement a pilot study. The inclusion criteria for the pilot study include: Having ADHD diagnostic symptoms based on DSM-5, age 6 to 9 years, being accepted in the school entrance assessment test, having impulsivity based on the impulsivity items of the Connors short form of parents, not having a physical disability, not having a history of attending class. The rhythmic movements were like (dance and gymnastics). Exclusion criteria included: Changes in drug therapy and initiation of new treatment during the study process, as well as effective family events such as divorce, immigration, death of one of the main family members, and non-participation in all intervention sessions.

Study measurements

The integrated visual and auditory (IVA-2) test was used as a specialized test to diagnose ADHD symptoms in this study. The IVA-2 is a type of continuous performance testing, which is used to help diagnose ADHD and determine indicators of attention and concentration. The IVA-2 test separates 5 types of attention, including focused attention, sustained attention, selective attention, divided attention, and transfer and displacement of attention in both visual and auditory areas. It takes 20 min to run this computerized diagnostic tool. The first 2 min are for familiarizing yourself with the test, 16 min for tests, and the last 2 min for assessing the validity of the test, which is called the relaxation phase.

Study procedure

After selecting the children with ADHD based on the criteria for entering the study, before the implementation, their parents were informed about the training process and study objectives and completed the consent form. At first, the IVA-2 test was performed, and the examiner was unaware of the type of exercises and intervention program. Then, for each of the clients, for three weeks (three phases) and two sessions every week, a total of six sessions of exercises were performed in the environment of one of the occupational therapy clinics in Tehran City, Iran. The first two sessions of the first phase exercises, the middle two sessions of the second phase exercises, and the last two sessions of the third phase exercises were used. For this purpose, every week’s exercise design was given to the children’s families in printed form at the beginning of that week. In the end, the IVA-2 test was performed again for the participating children. In the end, it was explained to the parents, and the family’s questions were answered by the experts.

Results

Based on the design objectives of the pilot study, the possibility of implementing the exercises was approved. These exercises can be used in rehabilitation clinics and for ADHD children. The cooperation of children and families was also reported as suitable. The results were analyzed in the indicators of attention, response control, prudence audio, and prudence visual, which are shown in Figure 1. The results indicated positive changes in all four participants in indicators related to impulsivity, i.e. prudence and response control. In the attention section, the results showed positive changes in all four participants. Due to the number of participants the pilot nature of the study, and the lack of comprehensive and multiple evaluations, these results can only be a reason for the foundation of extensive randomized clinical intervention trial research. It is not considered clinically generalizable to ADHD children.

Clinical observations

During the study, interesting aspects were observed in the form of additional information, which included the following items:

1. All the participants attended the sessions with great enthusiasm from the second session and after familiarizing themselves with the type of exercises. According to the report, three families reported that the children were waiting to come to the rehabilitation clinic even in the interval between two consecutive sessions to participate in the next session.

2. In the training phases, all children show better participation in the second session of each stage than in the first session.

3. One of the children sometimes reported feeling pain in the area of the ankles and soles of the feet, which was referred to an orthopedic specialist, and the cause was reported to be improper indoor flooring. Suitable flooring for use at home was provided to the participants.

4. According to the reports of two families, the implementation of indoor exercises had improved the parent-child relationship to a large extent.

5. Three families reported that the child has developed a better sleep routine at night and the day after training.

Discussion

This package of proposed interventional exercises considered two aspects as follows: 1) Using rhythm and movement coordination with external music (paying attention to the external stimulus) while performing movement exercises and aligning in harmony with it and, 2) Using dual activity, including motor-cognitive tasks combined with the ability to perform fully by ADHD children. In the preliminary research, two goals were pursued, which were to investigate the clinical feasibility of these exercises and identify the problems during the exercises and second, to examine their initial effect on impulsivity indicators. The initial results indicated that the proposed package could achieve a high implementation capability and all four children participating in the pilot could easily handle the exercises and welcomed this challenge with great enthusiasm after the first session of each phase They showed enthusiasm and interest to attend again and perform exercises of this type. Also, noticeable changes occurred in the fields of response control, attention, and prudence. According to the results of previous studies, such as the research conducted by Rapp and Su [34] in emphasizing the use of movement rhythm and its homogeneity with environmental rhythmic sequences, the occurrence of these changes was expected because many researchers found the underlying cause of hyperactivity and impulsivity. In this group of children, they know the function of the anterior cingulate and motor planning areas in areas 6 and 32 Brodmann areas of the cerebral cortex and the role of these areas in planning and coordinating rhythm and movement sequences and targeting movements according to specific patterns can be considered to some extent justify the noticeable changes that have occurred [49]. Also, based on Mostofsky’s comments in describing the interactive and reciprocal relationship between movement and cognitive process, as well as noticeable changes in previous research reports on the application and use of dual motor tasks, these cases can be considered as possible reasons for these changes [50، 51]. Perhaps according to the results of the side findings and the reports of the families about the high enthusiasm and cooperation of the participants in this proposed package, these things can be aligned with the research results in the field of using fun sports movement activities and favorite skillful movement training. Children know that it has created a double motivation to acquire movement skills in the activities that these children like and taste, which is one of the important reasons for the results.

Another issue that can be considered one of the advantages of this package is the simplicity of the proposed package and its inclusion of all three cognitive, movement, and rhythmic parts, as well as its innovative advantage in using listening functions. The results of several studies have also indicated the effect of using auditory rhythms in children with ADHD in motor control and improving attention functions [25، 26، 51]. Considering that rhythmic complexity can modulate neural and behavioral actions, the effect of rhythmic movement patterns in the obtained results can be interpreted following past findings [52].

The positive changes in the results of attention can also be taken into consideration by considering the use of external audio cues in exercises, which is the same feature of synchronizing selective attention with a specific external rhythm and melody (emphasized in previous studies) [53].

One of the important and reportable features of this proposed package is the possibility of doing it in children’s clinics, as well as the expansion and coordination of exercises at home. The motivation and interest of children to perform such exercises in the form of targeted activities and games in line with the improvement and strengthening of parents’ relationship with participants and the willingness and cooperation of families to participate in the training sessions of this proposed package have also been among the possible basic causes of changes.

The possible reason for the high willingness and cooperation of families to participate in the training sessions of this proposed package can be attributed to excessive caution toward the follow-up of drug treatments and avoiding its possible side effects. When performing the designed exercises, the child will experience a higher level of executive functions in the form of motor challenges, and with greater ability in the fields of response control and working memory, it is expected that he will show more ability in controlling the symptoms of impulsivity. Considering that this study is only a pilot study and the statistical results are not generalizable to use the exercise package as a treatment, and it is only the beginning of a research process that requires additional research. Another limitation of this study is the impossibility of directly monitoring the way exercises are performed at home, which requires further investigation and planning in this field in future designs.

Conclusion

Considering previous studies and basic science information in this field about the impairment in the performance of ADHD children and the essential role and serious impact of impulsivity of these children on all their functional areas and the existence of rhythm and control disorders and based on clinical findings about the effectiveness of interventions Physically, the results of the designed exercise package can be accepted on the symptoms of ADHD. In addition, the possibility of implementation and its attractiveness and acceptability by children and parents can be confirmed and used in future studies. This proposed package covers a larger field of ADHD children’s functions and provides wider challenges for the child in line with the complexity of impulsivity symptoms in the context of the dual tasks paradigm.

Future study recommendations:

Examining and redefining the duration of sessions the number of sessions and their timing should be done. Designing a randomized controlled trial study to implement this package using more samples and accurate and reliable multiple assessment tools to check the impact and durability of the results after the follow-up period and compare it with existing approaches in the rehabilitation of ADHD children in the form of research, using several test and control groups is suggested. Examining the correlation coefficient between impulsivity changes with other ADHD symptoms and also with the satisfaction and quality of family life will be of study value. At the same time, it is recommended to implement this package in different cities and regions and different age ranges.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The parents of the children were fully aware of the study process, goals, and methods and signed a consent form for voluntary participation in the study. They were free to leave the study and were assured of the confidentiality of their information This study was approved by the ethics committee of University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.207)

Funding

The paper was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Behzad Amini, approved by the Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Behzad Amini, Ebrahim Peshiareh, and Seyed Ali Hosseini; Methodology: Behzad Amini, Ebrahim Pishyareh, Seyed Ali Hosseini and Enayatullah Bakshi; validation, research and investigation: Behzad Amini, Ebrahim Peshyareh and Hojat Elha Haqgoo; data analysis: Behzad Amini and Enayatullah Bakshi; Writing the original draft: Behzad Amini; Review and editing: Behzad Amini and Ebrahim Peshyareh; Supervision and project management: Ebrahim Peshiareh and Seyed Ali Hosseini.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants and their families as well as the clinical therapists for their cooperation and assistance in this study.

References

- Wang T, Liu K, Li Z, Xu Y, Liu Y, Shi W, et al. Prevalence of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder among children and adolescents in China: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC psychiatry. 2017; 17:1-1. [DOI:10.1186/s12888-016-1187-9]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). San Francisco: Booksmith Publishing LLC; 2021. [Link]

- Colomer C, Berenguer C, Roselló B, Baixauli I, Miranda A. The impact of inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms, and executive functions on learning behaviors of children with ADHD. Frontiers in psychology. 2017; 8:540. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00540]

- Barkley RA. Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: Constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological Bulletin. 1997; 121(1):65-94. [DOI:10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65]

- Torto-Seidu E. Effects of reflective teaching strategies on problem-solving abilities of impulsive children [PhD dissertation]. Cape Coas: University of Cape Coast; 2020. [Link]

- Patros CH, Alderson RM, Kasper LJ, Tarle SJ, Lea SE, Hudec KL. Choice-impulsivity in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2016;43:162-74. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.001]

- Amini B, Hosseini SA, Akbarfahimi N. Balance performance disorders and sway of the center of gravity in children with ADHD. Journal of Modern Rehabilitation. 2018; 12(1):3-12. [DOI:10.32598/jmr.12.1.3]

- Jahani M, Pishyareh E, Haghgoo HA, Hosseini SA, Ghadamgahi Sani SN. Neurofeedback effect on perceptual-motor skills of children with ADHD. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2016; 14(1):43-50. [DOI:10.15412/J.IRJ.08140107]

- Nigg JT. Attention and impulsivity. Developmental Psychopathology. 2016; 1-56. [DOI:10.1002/9781119125556.devpsy314]

- Winstanley CA, Eagle DM, Robbins TW. Behavioral models of impulsivity in relation to ADHD: Translation between clinical and preclinical studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2006; 26(4):379-95. [DOI:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.001]

- Amini B, Hosseini A, Azadi H, Pishyareh E. [Review: Impulsivity in children: Causes, definitions, and theories (Persian)]. Journal of exceptional children. 2023; 23(1):19-34. [DOI:10.52547/joec.23.1.19]

- Chamorro J, Bernardi S, Potenza MN, Grant JE, Marsh R, Wang S, et al. Impulsivity in the general population: A national study. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012; 46(8):994-1001. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.04.023]

- Kadesjö B, Gillberg C. Attention deficits and clumsiness in Swedish 7-year-old children. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 1998; 40(12):796-804. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.1998.tb12356.x]

- Walerius DM, Reyes RA, Rosen PJ, Factor PI. Functional impairment variability in children with ADHD due to emotional impulsivity. Journal of attention disorders. 2018; 22(8):724-37. [DOI:10.1177/1087054714561859]

- Baddeley A. Working memory. Science. 1992; 255(5044):556-9. [DOI:10.1126/science.1736359]

- Cepeda NJ, Cepeda ML, Kramer AF. Task switching and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000; 28:213-26. [DOI:10.1023/A:1005143419092]

- Sergeant JA, Geurts H, Oosterlaan J. How specific is a deficit of executive functioning for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder? Behavioural Brain Research. 2002; 130(1-2):3-28. [DOI:10.1016/S0166-4328(01)00430-2]

- Ionescu T. Exploring the nature of cognitive flexibility. New Ideas in Psychology. 2012; 30(2):190-200. [DOI:10.1016/j.newideapsych.2011.11.001]

- Monsell S. Task switching. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2003; 7(3):134-40. [DOI:10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00028-7]

- Leshem R. Using dual process models to examine impulsivity throughout neural maturation. Developmental Neuropsychology. 2016; 41(1-2):125-43. [DOI:10.1080/87565641.2016.1178266]

- Wu K, Anderson V, Castiello U. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and working memory: A task switching paradigm. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2006; 28(8):1288-306. [DOI:10.1080/13803390500477267]

- Caldani S, Razuk M, Septier M, Barela JA, Delorme R, Acquaviva E, et al. The effect of dual task on attentional performance in children with ADHD. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. 2019; 12:67. [DOI:10.3389/fnint.2018.00067]

- Slater JL, Tate MC. Timing deficits in ADHD: Insights from the neuroscience of musical rhythm. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience. 2018; 12:51. [DOI:10.3389/fncom.2018.00051]

- Bijlenga D, Vollebregt MA, Kooij JS, Arns M. The role of the circadian system in the etiology and pathophysiology of ADHD: Time to redefine ADHD? ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders. 2019; 11(1):5-19. [DOI:10.1007/s12402-018-0271-z]

- Shin HJ, Lee HJ, Kang D, Kim JI, Jeong E. Rhythm-based assessment and training for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A feasibility study protocol. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2023; 17. [DOI:10.3389/fnhum.2023.1190736]

- Jamey K, Laflamme H, Foster NE, Rigoulot S, Kotz SA, Dalla Bella S. Can you beat the music? Validation of a gamified rhythmic training in children with ADHD. Medrxiv. 2024; [Unpublished]. [DOI:10.1101/2024.03.19.24304539]

- Bloch MH, Panza KE, Landeros-Weisenberger A, Leckman JF. Meta-analysis: Treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children with comorbid tic disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2009; 48(9):884-93. [DOI:10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b26e9f]

- Deslandes A, Moraes H, Ferreira C, Veiga H, Silveira H, Mouta R, et al. Exercise and mental health: Many reasons to move. Neuropsychobiology. 2009; 59(4):191-8. [DOI:10.1159/000223730]

- Kramer AF, Erickson KI. Capitalizing on cortical plasticity: influence of physical activity on cognition and brain function. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2007; 11(8):342-8. [DOI:10.1016/j.tics.2007.06.009]

- McAuley E, Elavsky S, Jerome GJ, Konopack JF, Marquez DX. Physical activity-related well-being in older adults: Social cognitive influences. Psychology and Aging. 2005; 20(2):295. [DOI:10.1037/0882-7974.20.2.295]

- Buchanan J, Kelso J, DeGuzman G, Ding M. The spontaneous recruitment and suppression of degrees of freedom in rhythmic hand movements. Human Movement Science. 1997; 16(1):1-32. [DOI:10.1016/S0167-9457(96)00040-1]

- Ohgi S, Morita S, Loo KK, Mizuike C. Time series analysis of spontaneous upper-extremity movements of premature infants with brain injuries. Physical Therapy. 2008; 88(9):1022-33. [DOI:10.2522/ptj.20070171]

- Amrani AK, Golumbic EZ. Spontaneous and stimulus-driven rhythmic behaviors in ADHD adults and controls. Neuropsychologia. 2020; 146:107544. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107544]

- Repp BH, Su YH. Sensorimotor synchronization: A review of recent research (2006-2012). Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 2013; 20:403-52. [DOI:10.3758/s13423-012-0371-2]

- Glass L. Synchronization and rhythmic processes in physiology. Nature. 2001; 410:277-84. [DOI:10.1038/35065745]

- Lense MD, Ladányi E, Rabinowitch TC, Trainor L, Gordon R. Rhythm and timing as vulnerabilities in neurodevelopmental disorders. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 2021; 376(1835):20200327. [DOI:10.1098/rstb.2020.0327]

- Giannaraki M, Moumoutzis N, Papatzanis Y, Kourkoutas E, Mania K. A 3D rhythm-based serious game for collaboration improvement of children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Paper presented at: 2021 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON); 23 April 2021; Vienna, Austria. [DOI:10.1109/EDUCON46332.2021.9453999]

- Burnham B. Make a move: A multi-sensory, movement coordinated furnishing support system for children with ADHD: A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the degree of master of design [master thesis]. Palmerston North: Massey University; 2012. [Link]

- Ahmed GM, Mohamed S. Effect of regular aerobic exercises on behavioral, cognitive and psychological response in patients with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Life Science Journal. 2011; 8(2):366-71. [Link]

- Bustamante EE. Physical activity intervention for ADHD and DBD. Chicago: University of Massachusetts; 2006. [Link]

- Chen LJ, Stevinson C, Ku PW, Chang YK, Chu DC. Relationships of leisure-time and non-leisure-time physical activity with depressive symptoms: A population-based study of Taiwanese older adults. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2012; 9(28):1-10. [DOI:10.1186/1479-5868-9-28]

- Cornelius C, Fedewa AL, Ahn S. The effect of physical activity on children with ADHD: A quantitative review of the literature. Journal of Applied School Psychology. 2017; 33(2):136-70. [DOI:10.1080/15377903.2016.1265622]

- Hoza B, Smith AL, Shoulberg EK, Linnea KS, Dorsch TE, Blazo JA, et al. A randomized trial examining the effects of aerobic physical activity on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015; 43:655-67. [DOI:10.1007/s10802-014-9929-y]

- Kang K, Choi J, Kang S, Han D. Sports therapy for attention, cognitions and sociality. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 2011; 32(12):953-9. [DOI:10.1055/s-0031-1283175]

- Lufi D, Parish-Plass J. Sport-based group therapy program for boys with ADHD or with other behavioral disorders. Child & Family Behavior Therapy. 2011; 33(3):217-30. [DOI:10.1080/07317107.2011.596000]

- Medina JA, Netto TL, Muszkat M, Medina AC, Botter D, Orbetelli R, et al. Exercise impact on sustained attention of ADHD children, methylphenidate effects. ADHD Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders. 2010; 2:49-58. [DOI:10.1007/s12402-009-0018-y]

- Piepmeier AT, Shih CH, Whedon M, Williams LM, Davis ME, Henning DA, et al. The effect of acute exercise on cognitive performance in children with and without ADHD. Journal of Sport and Health Science. 2015; 4(1):97-104. [DOI:10.1016/j.jshs.2014.11.004]

- TSE AC, Anderson DI, Liu VH, Tsui SS. Improving executive function of children with autism spectrum disorder through cycling skill acquisition. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2021; 53(7):1417-24. [DOI:10.1249/MSS.0000000000002609]

- Vogt BA. Cingulate impairments in ADHD: Comorbidities, connections, and treatment. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. 2019; 166:297-314. [DOI:10.1016/B978-0-444-64196-0.00016-9]

- Dahan A, Reiner M. Evidence for deficient motor planning in ADHD. Scientific Reports. 2017; 7(1):9631. [DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-09984-7]

- Ferguson C, Hobson C, Hedge C, Waters C, Anning K, Van Goozen S. Disentangling the relationships between motor control and cognitive control in young children with symptoms of ADHD. Child Neuropsychology. 2024; 30(2):289-314. [DOI:10.1080/09297049.2023.2190965]

- Mathias B, Zamm A, Gianferrara PG, Ross B, Palmer C. Rhythm complexity modulates behavioral and neural dynamics during auditory-motor synchronization. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2020; 32(10):1864-80. [DOI:10.1162/jocn_a_01601]

- Laffere A, Dick F, Holt LL, Tierney A. Attentional modulation of neural entrainment to sound streams in children with and without ADHD. NeuroImage. 2021; 224:117396. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117396]

Type of Study: Applicable |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 29/11/2023 | Accepted: 16/06/2024 | Published: 1/11/2024

Received: 29/11/2023 | Accepted: 16/06/2024 | Published: 1/11/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |