Volume 25, Issue 3 (Autumn 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(3): 396-423 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Vahidi H, Mandani G, Hosseini S A, AkbarFahimi N, Rahmani A. Barriers and Facilitators of Occupational Performance of People With Stroke: A Meta-synthesis. jrehab 2024; 25 (3) :396-423

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3397-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3397-en.html

1- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,ghazal.mandani@gmail.com

3- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, Faculty of Nursing and Midwifery, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 2323 kb]

(1099 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5811 Views)

Full-Text: (1762 Views)

Introduction

Stroke is an acute neurological event with vascular origin, which leaves lasting and destructive effects on the brain function of the victims. This illness is prevalent, leading to mortality and incapacity, posing a significant issue for the global public health domain [1]. According to the assessment of the World Health Organization (WHO), stroke is “an acute neurological disorder lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death in less than 24 hours” [2]. The frequency of initial stroke occurrence in Iran is recorded at 150 cases per 100000 individuals. The findings from research conducted in Iran indicate a notably elevated prevalence of stroke compared to the majority of Western nations, with a tendency for manifestation at a relatively younger age. The rate of ischemic stroke in Iran also shows a notably elevated rate compared to other geographical areas [3]. Stroke is often experienced as a major disorder in a person’s life and causes tremendous changes in different dimensions of the survivors’ lives [4]. This disorder usually occurs suddenly without warning and leads to major changes in the lives of patients and their families [5].

Upon discharge from the hospital following a stroke, several patients undergo enduring impairments, comprising weakness, balance issues, cognitive impairments, and immobility [6]. All these problems can have destructive effects on occupational performance, particularly the daily activities of individuals affected, which were previously viewed as uncomplicated in their daily routines. Therefore, it is necessary to take all measures required to improve the occupational performance of these people that can facilitate their participation in purposeful activities [7].

Occupational performance can be characterized as the capacity to select, arrange, and effectively engage in significant activities that are culturally determined and suitable for one’s age. It encompasses the ability to attend to one’s needs, derive pleasure from life, and engage in societal participation and interaction within a given community’s social and economic framework [8]. Occupational performance in occupational therapy is one of the main and essential concepts that is also developing and evolving [9]. Recognizing and understanding the various life problems of stroke sufferers can help occupational therapists and other rehabilitation staff [10] to design more effective measures to meet the needs of clients in the field of occupational performance because the improvement in occupational performance after being discharged from the hospital can improve the overall quality of life (QoL) after experiencing a stroke [11].

Numerous investigations have been conducted within the domain of postdischarge care and transitioning to home for individuals who have suffered a stroke, particularly within the discipline of nursing [12]. Studies conducted in other countries using a qualitative approach frequently focus on delineating various aspects, such as the patient’s recovery and expectations from the recovery period after a stroke, understanding society’s thoughts about stroke disease, or understanding the patient’s fatigue after a stroke. From Chen’s (2021) perspective, the passage from hospitalization to home constitutes a complex phase in the process of rehabilitation and recovery following a stroke. Additional investigations are essential to enhance comprehension of the viewpoints held by various parties involved and to tackle unaddressed requirements in transitional healthcare [12].

Many individuals who have experienced a stroke and are released from medical facilities to continue their rehabilitation and recovery process at home encounter a multitude of obstacles related to home care [13]. Most stroke survivors enter an environment that presents many challenges when they return home, and occupational therapy to reduce these challenges is often prescribed to stroke survivors to enhance the shift from medical facility to home [14]. From Simeone’s (2015) perspective, the treatment and rehabilitation team should improve their interventions to support survivors in effectively managing the impactful changes in their post-stroke lives, while also motivating them to adjust to the challenges that arise in their daily activities due to the stroke [15].

Cobley (2013) stated in her study, based on the experience of patients, that failure to pursue rehabilitation puts them in danger. An apparent discrepancy was evident in the delivery of rehabilitation services between the period of hospitalization and the phase in the community. The prolonged waiting period for community-based rehabilitation programs, which certain survivors encountered, directly influenced the attainment of their objectives [16].

Brannigan (2017) concluded that resuming occupational performance following a stroke is intricate and can be influenced positively or negatively by factors within the organization, social environment, personal characteristics and the availability of suitable services. The consequences of a stroke, such as fatigue and various other elements, influence the reintegration into post-stroke occupational performance. Collaborative communication among healthcare providers and interdisciplinary team members may facilitate the reintegration process for individuals who have experienced a stroke. Furthermore, environmental modifications and activity adjustments are among the enabling factors that can support the integration of stroke survivors into their living environment [17].

Numerous research endeavors have been conducted concerning the challenges of post-hospital care for individuals who have survived a stroke [12]. Nevertheless, there is a notable scarcity of meta-synthesized research findings about the daily occupational performance of stroke patients and their caregivers following discharge within the realm of occupational therapy. This knowledge gap is further exacerbated by the predominant focus of existing studies on nursing, with a limited exploration from the vantage point of the occupational therapy discipline. This meta-synthesis tries to fill this gap. The outcomes of this study contribute to an enhanced comprehension of occupational performance post-stroke, gaining insight into the challenges and requirements of individuals affected by this condition and their support system and creating interventions focused on the individual. This meta-synthesis review aimed to combine qualitative research outcomes regarding the firsthand encounters of individuals who have suffered from stroke and their caregivers concerning occupational performance following a stroke.

Materials and Methods

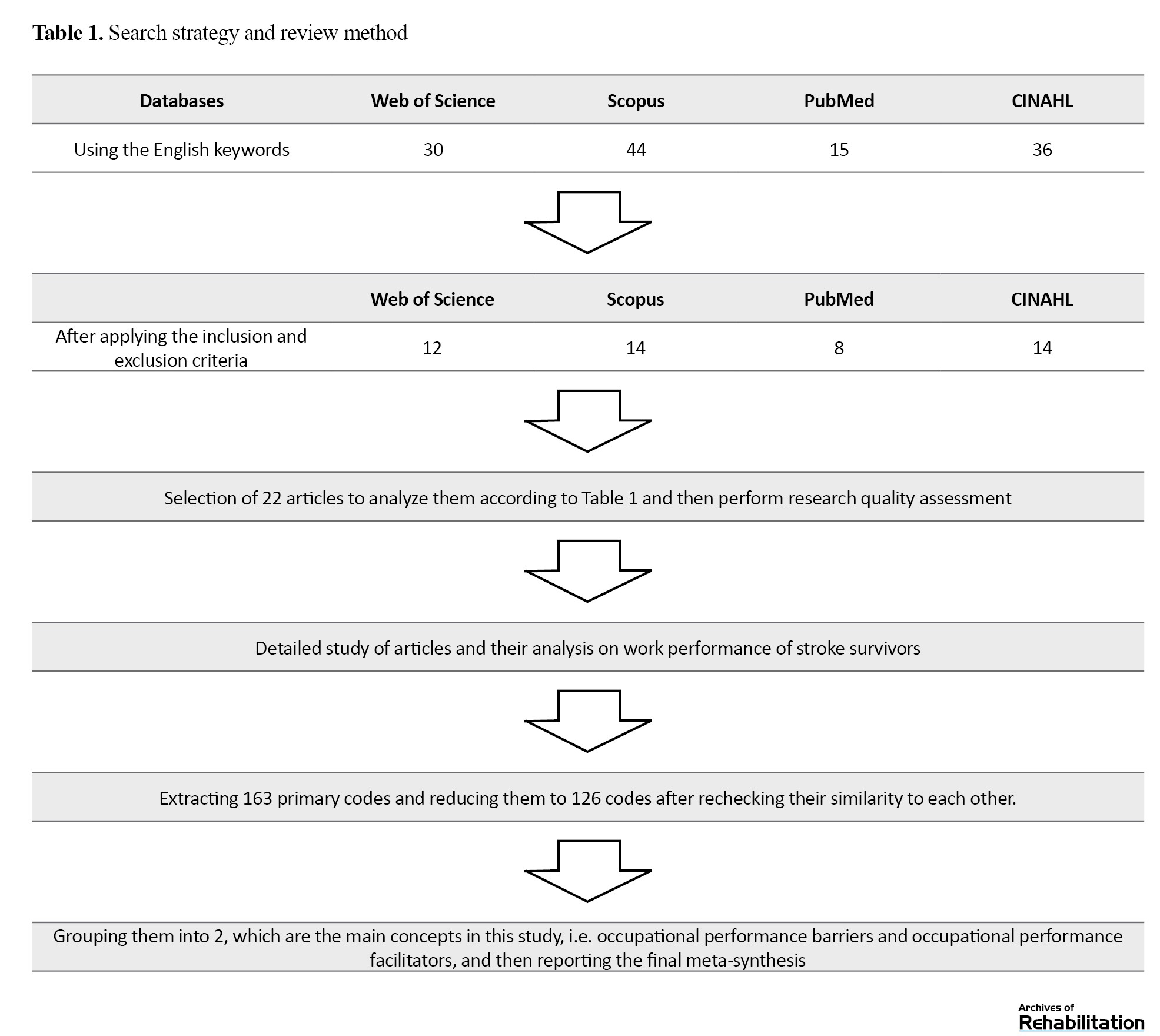

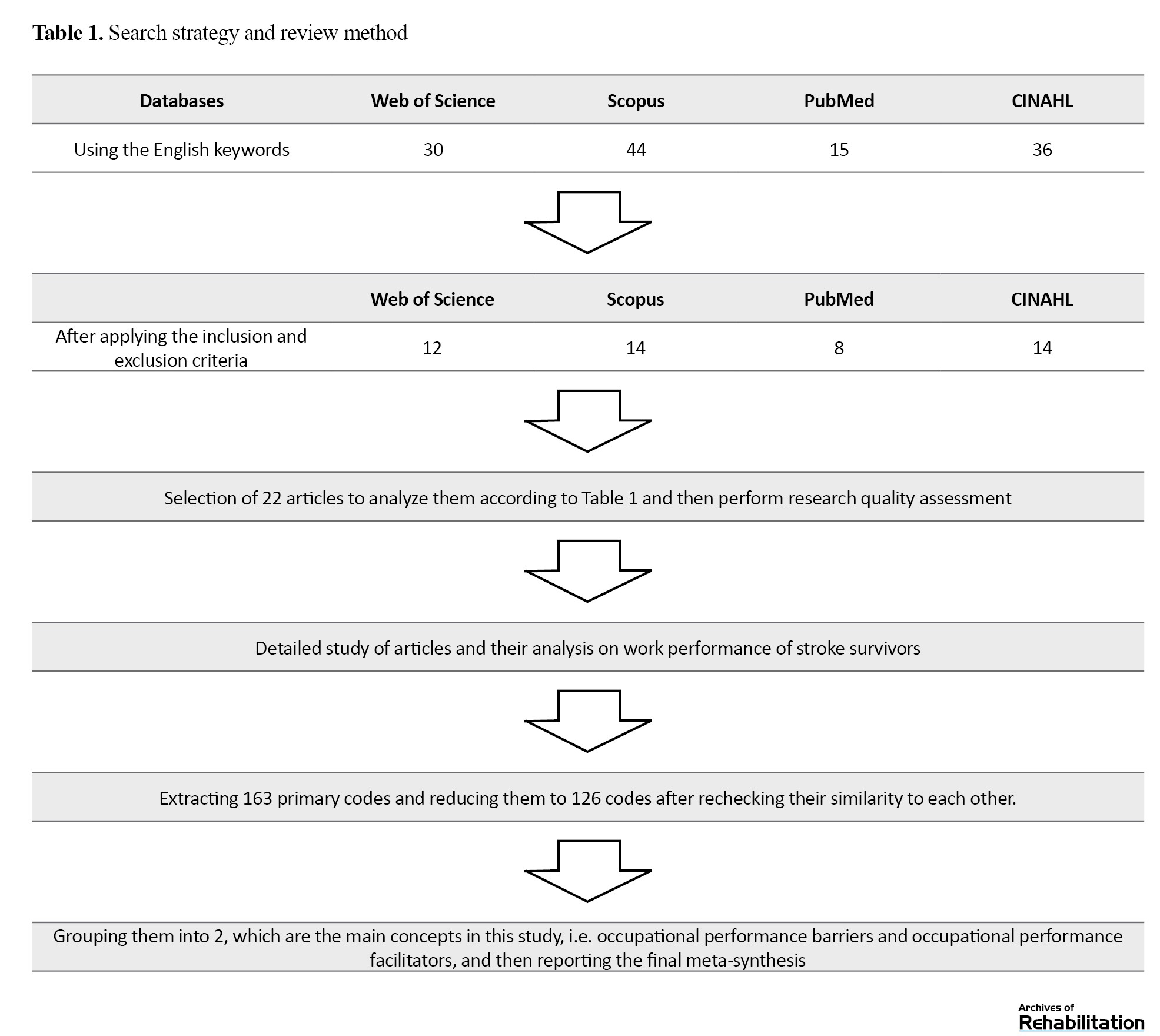

This review employs a meta-synthesis methodology defined by Edwards and Kaimal (2016), which extracts qualitative data from different articles, integrates them, and then creates new data and results [18]. Despite the variations in methodologies utilized in different categories of literary examinations, all reviews can be conducted by adhering to 8 fundamental steps: 1) Articulation of the research inquiry, 2) Establishment and authentication of the review protocol, 3) Retrieval of relevant articles, 4) Evaluation for the inclusion of studies, 5) Assessment of quality, 6) Extraction of data, 7) Analysis and synthesis of data and 8) Presentation of findings [19]. All these steps have been followed in this study. The articles were searched after formulating the research question and developing the review protocol. After screening for the inclusion criteria, the research quality was assessed using the critical appraisal skills program (CASP) questionnaire. The data have been extracted and analyzed, and the findings are reported in this study (Table 1).

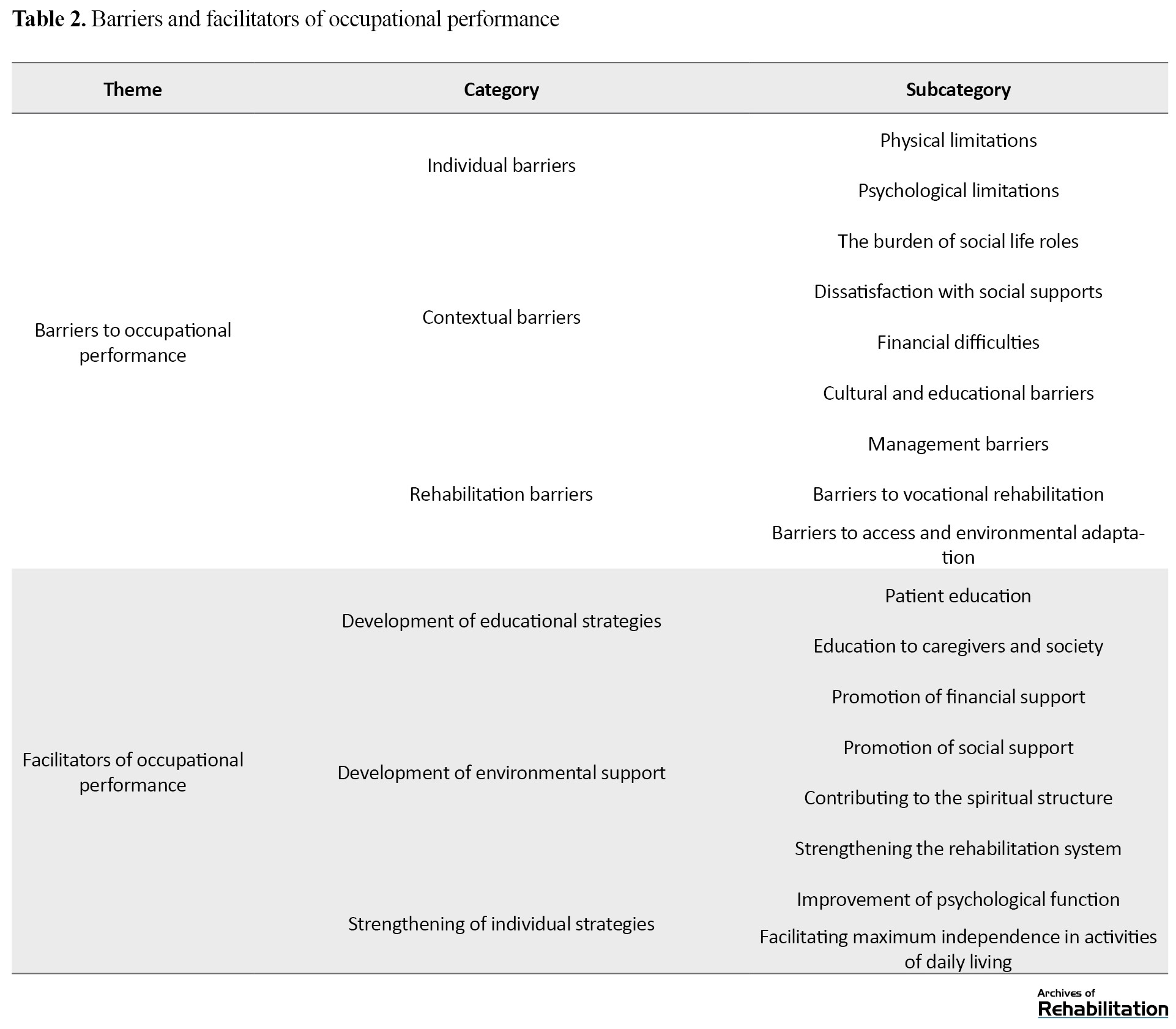

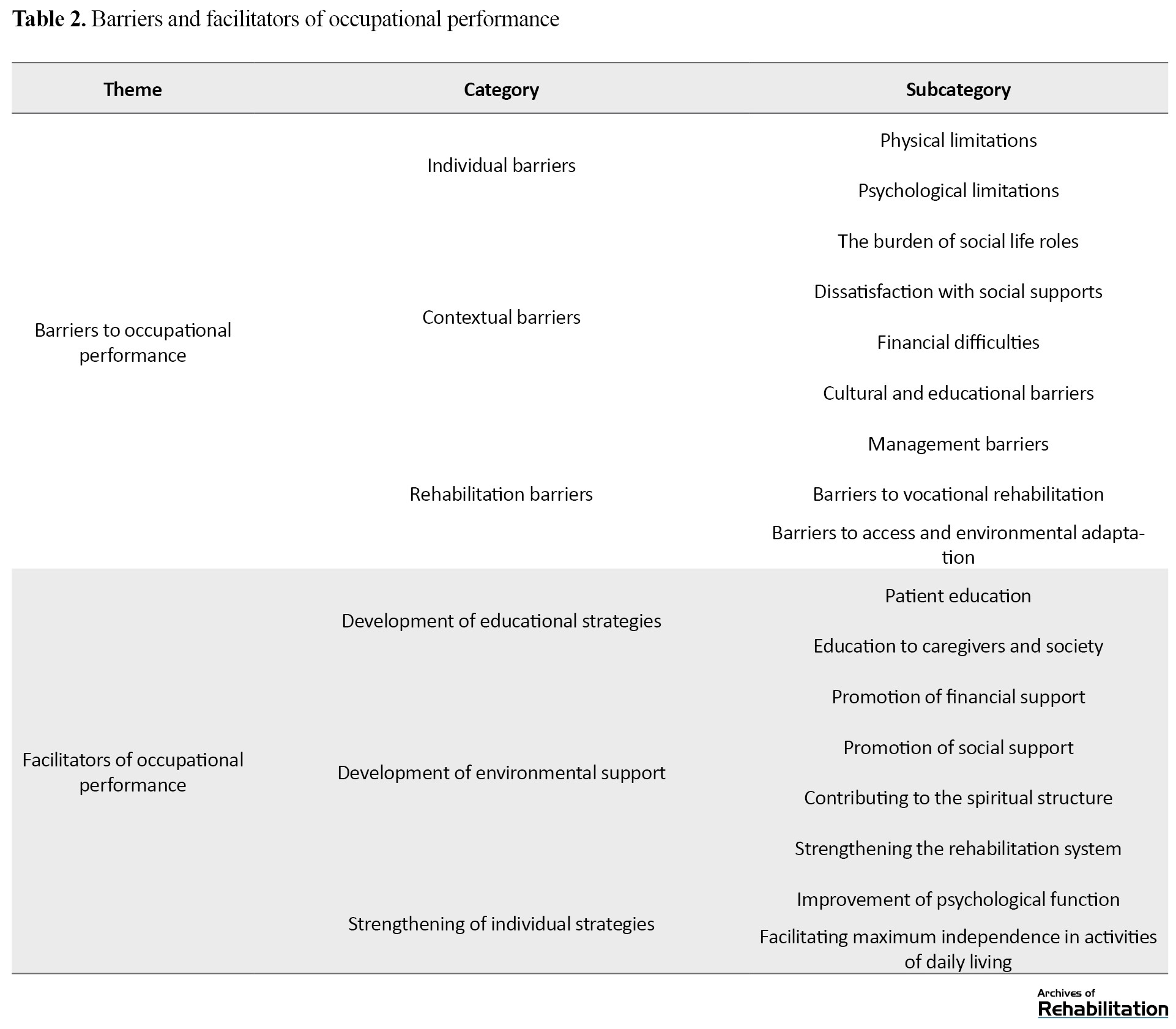

In this review, three important points were noted; the first thing is what experience clients with stroke had throughout their hospital stay and following their release from the medical facility in connection to their disability. The next thing is how these clients performed the tasks related to self-care after living with the problem of stroke and what experience their caregivers have in this field. The last thing is how, after recovery, the client’s occupational performance regarding returning to the former job has been affected. Therefore, after repeatedly reading and analyzing the articles in the results section, each article was analyzed line by line, and the meaning units were extracted from the articles’ text based on the research purpose. Then, the meaning units were converted into codes, and in the third stage, the classification of codes began until finally, classes and sub-classes were formed, and codes similar to each other were placed in one class. These classes were revised several times to compare with each other and form newer classes. At first, after analyzing the studies, 163 primary codes were extracted, which were reduced to 126 after rechecking their similarity to each other after grouping them. They were divided into 2 main groups: Occupational performance barriers and occupational performance facilitators (Table 2).

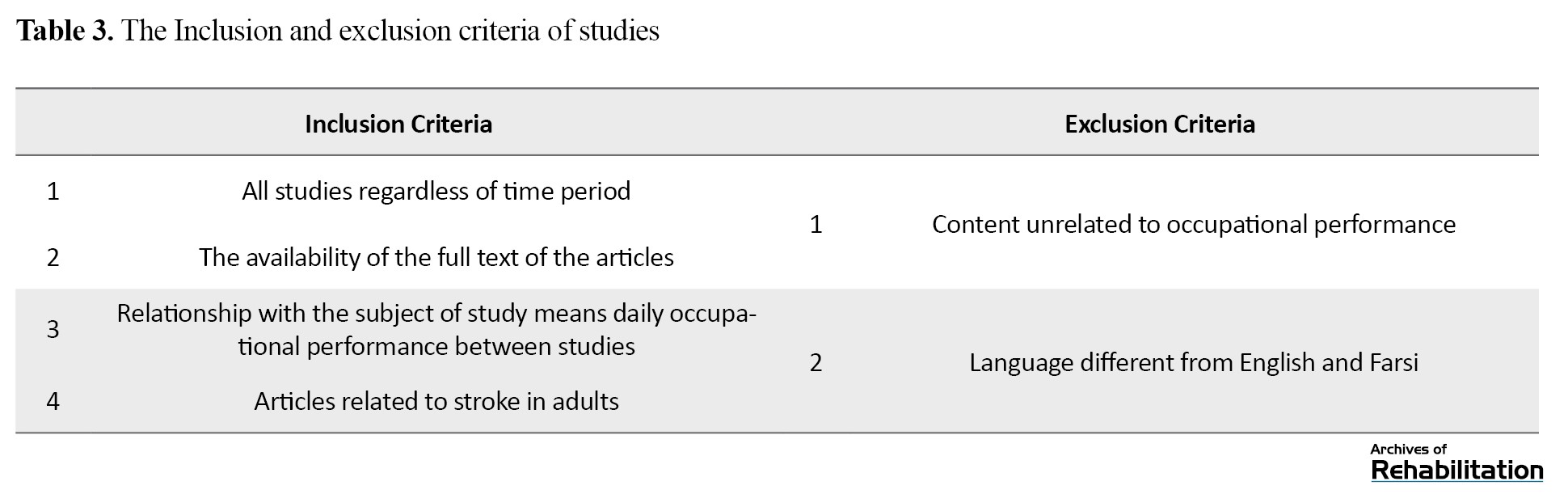

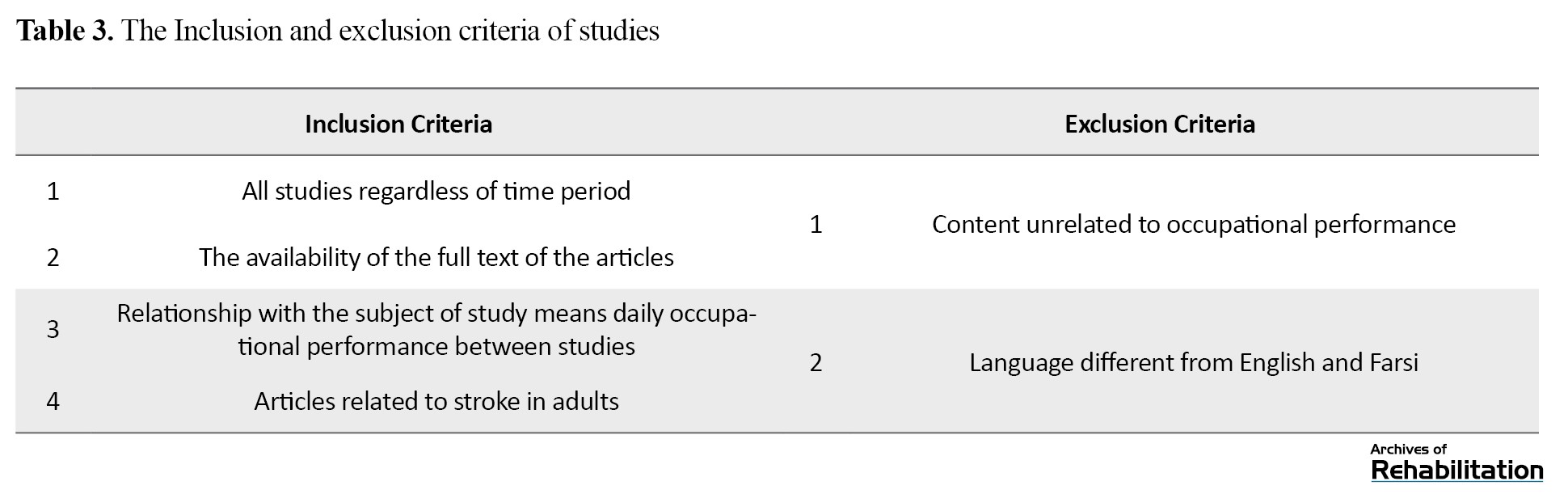

The keywords used in this study were the following: “occupational performance,” “self-care,” “activity of daily living,” “work,” “stroke,” “adult hemiplegia” and “qualitative research.” The search databases include CINAHL, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus until 2023. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study are also summarized in Table 3.

Quality assessment

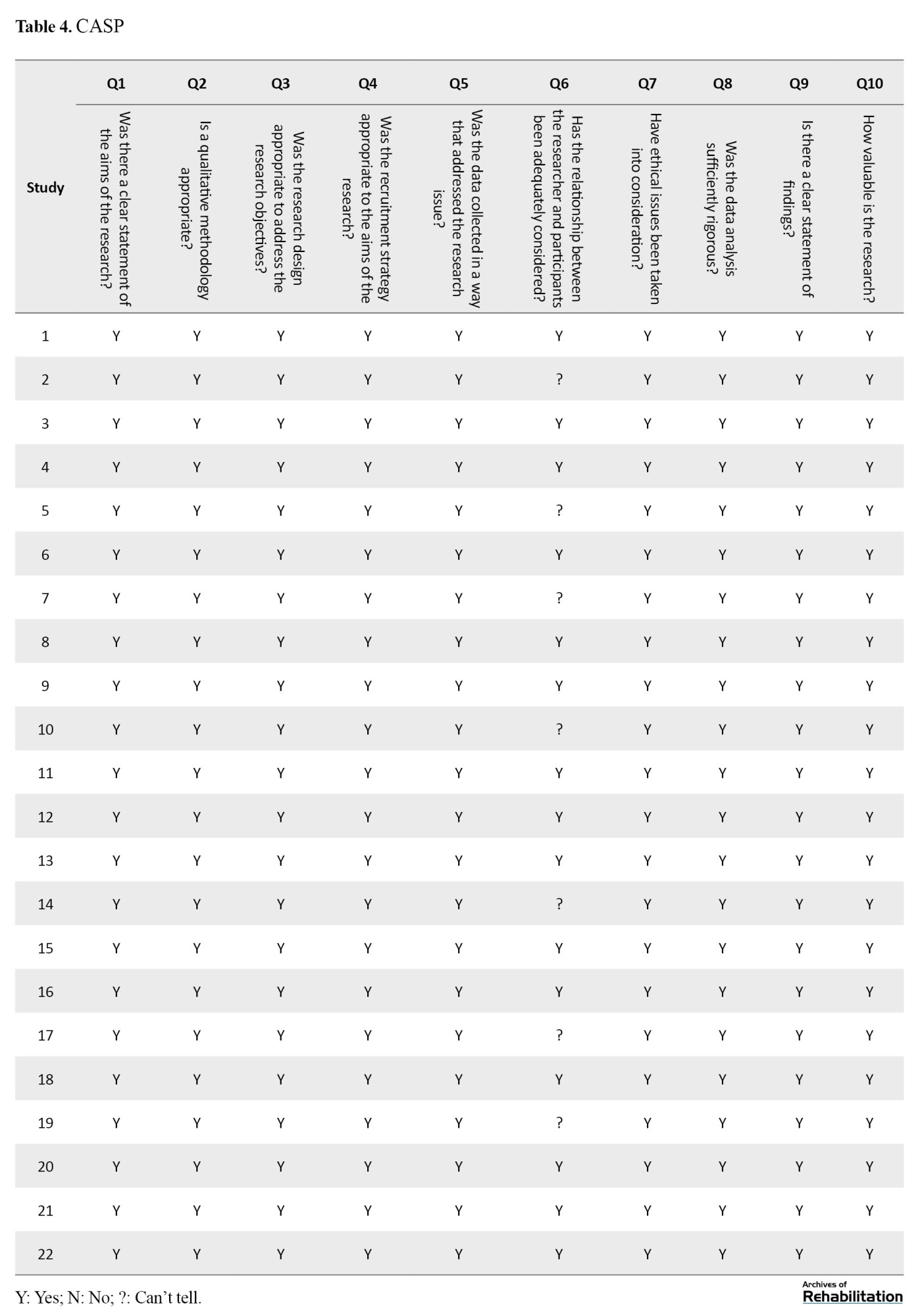

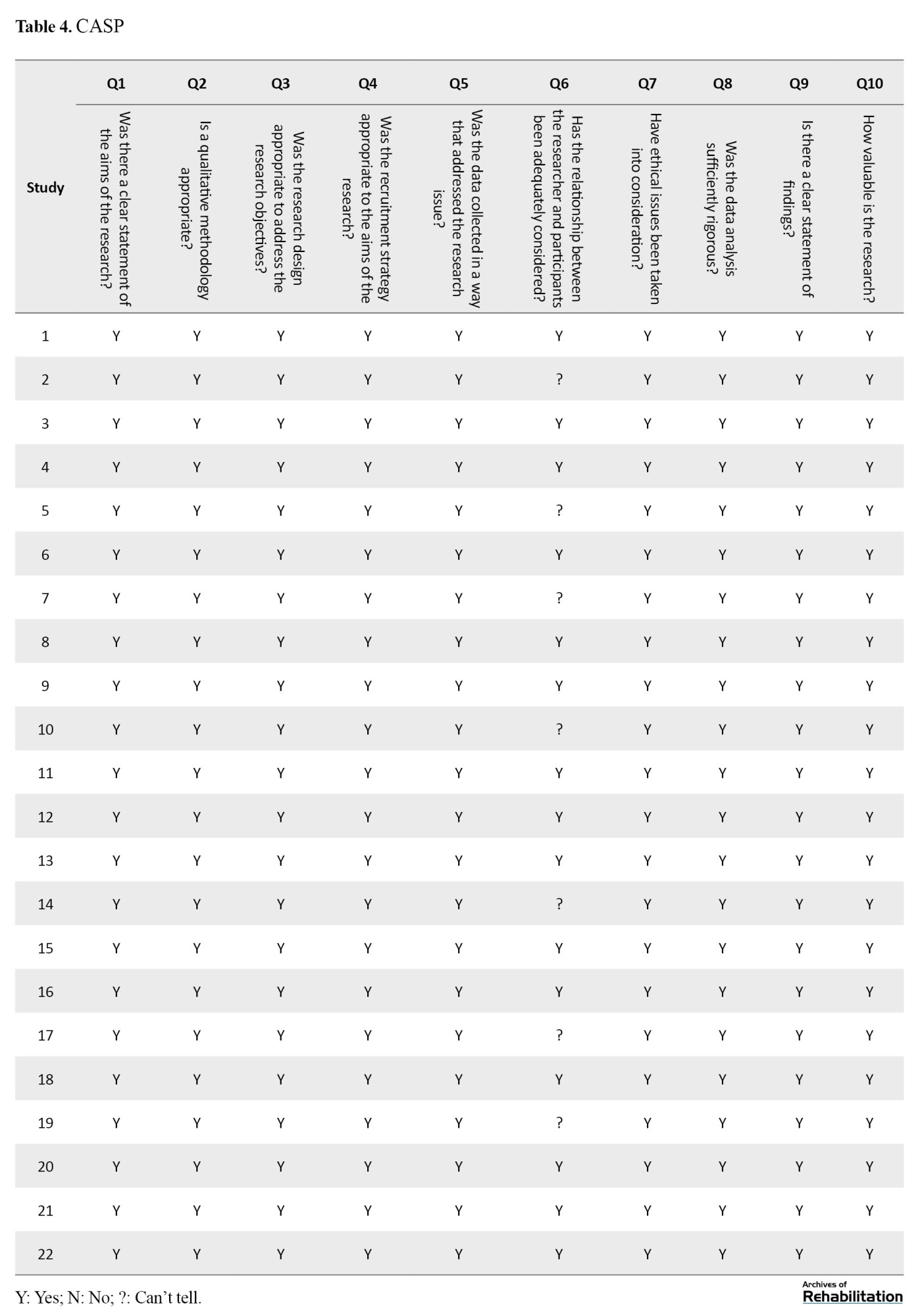

To guarantee the validity of the data employed, the instrument known as the CASP [20]. This instrument comprises a set of 10 inquiries designed to assess the caliber of research works for which the researcher has employed this survey in all publications (Table 4).

The results of this study were presented and discussed so that some practical guidance could be received for Tabriz University of Medical Sciences Nursing Researchers, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Occupational Therapy Department, and University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. Classification using predetermined categories and precise definitions, along with the dependability of coding, enhances the internal validity of the results. Extracting the context and forming theoretical abstractions from the outcomes of content analysis enables a certain level of generalizability of the results, thereby enhancing external validity [21]. In general, strategies for building trust in qualitative research were considered in this study. All authors read the articles independently, and during the analysis of classes and units of meaning, they repeatedly discussed them until they reached the final classes and subclasses.

Results

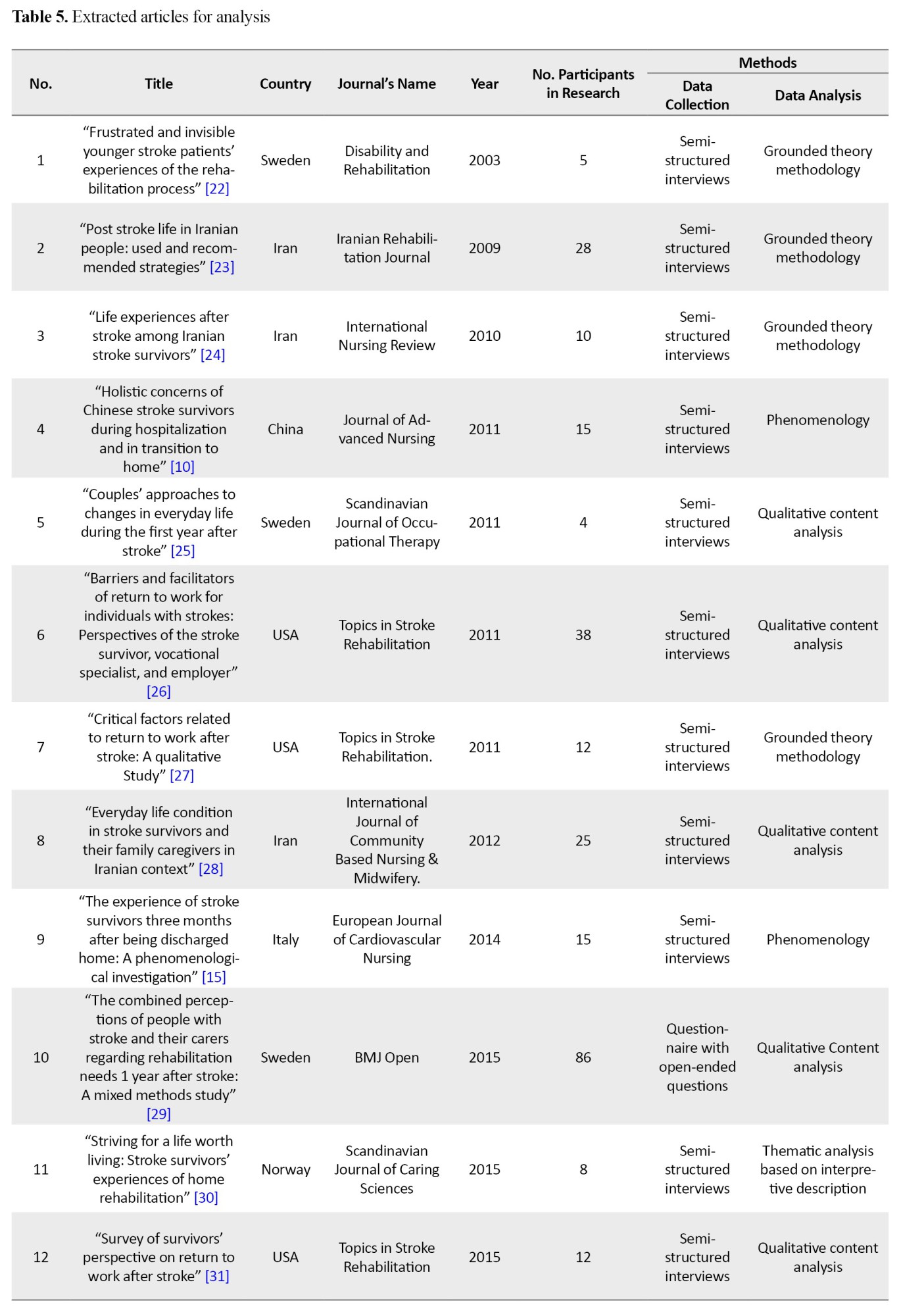

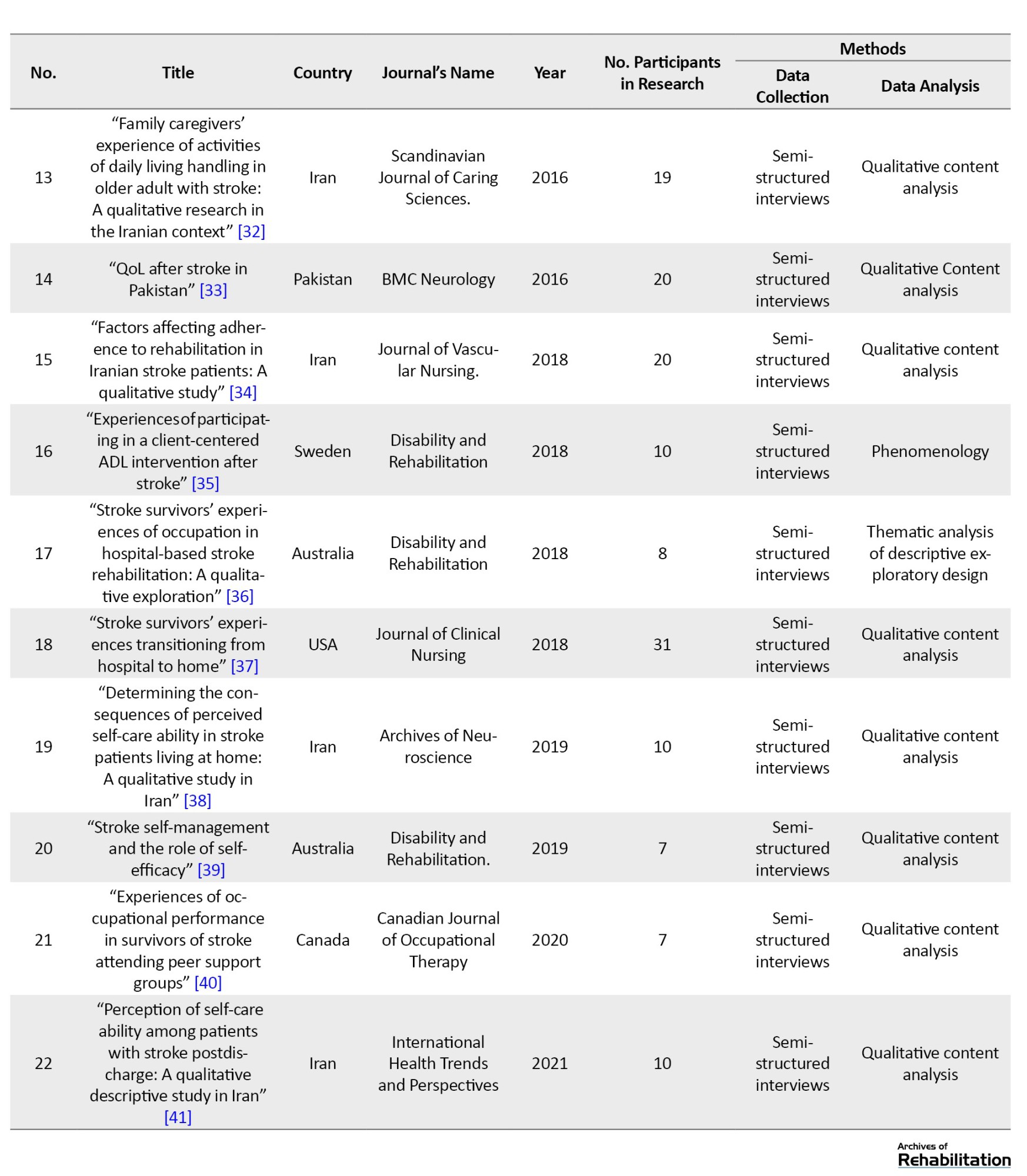

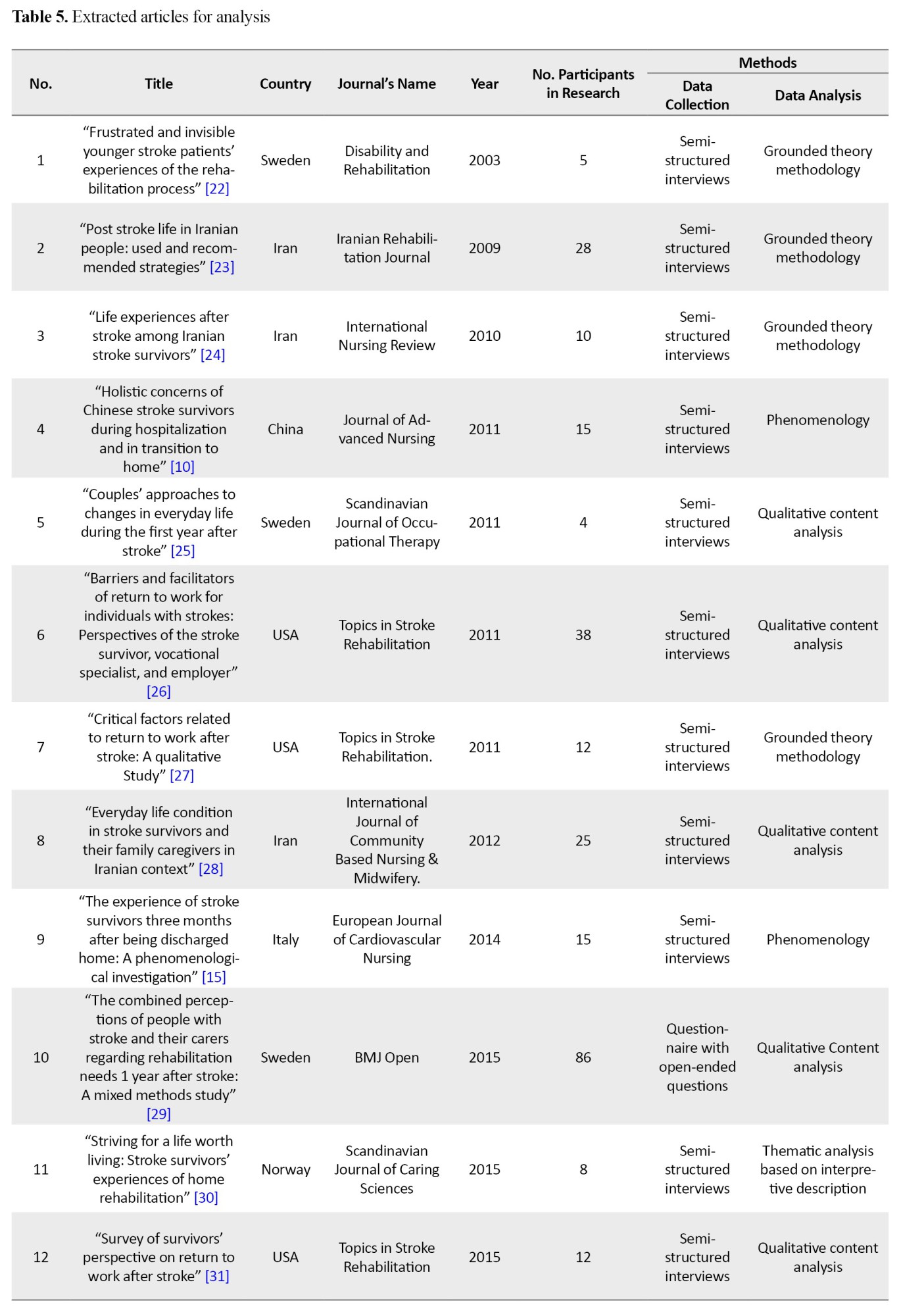

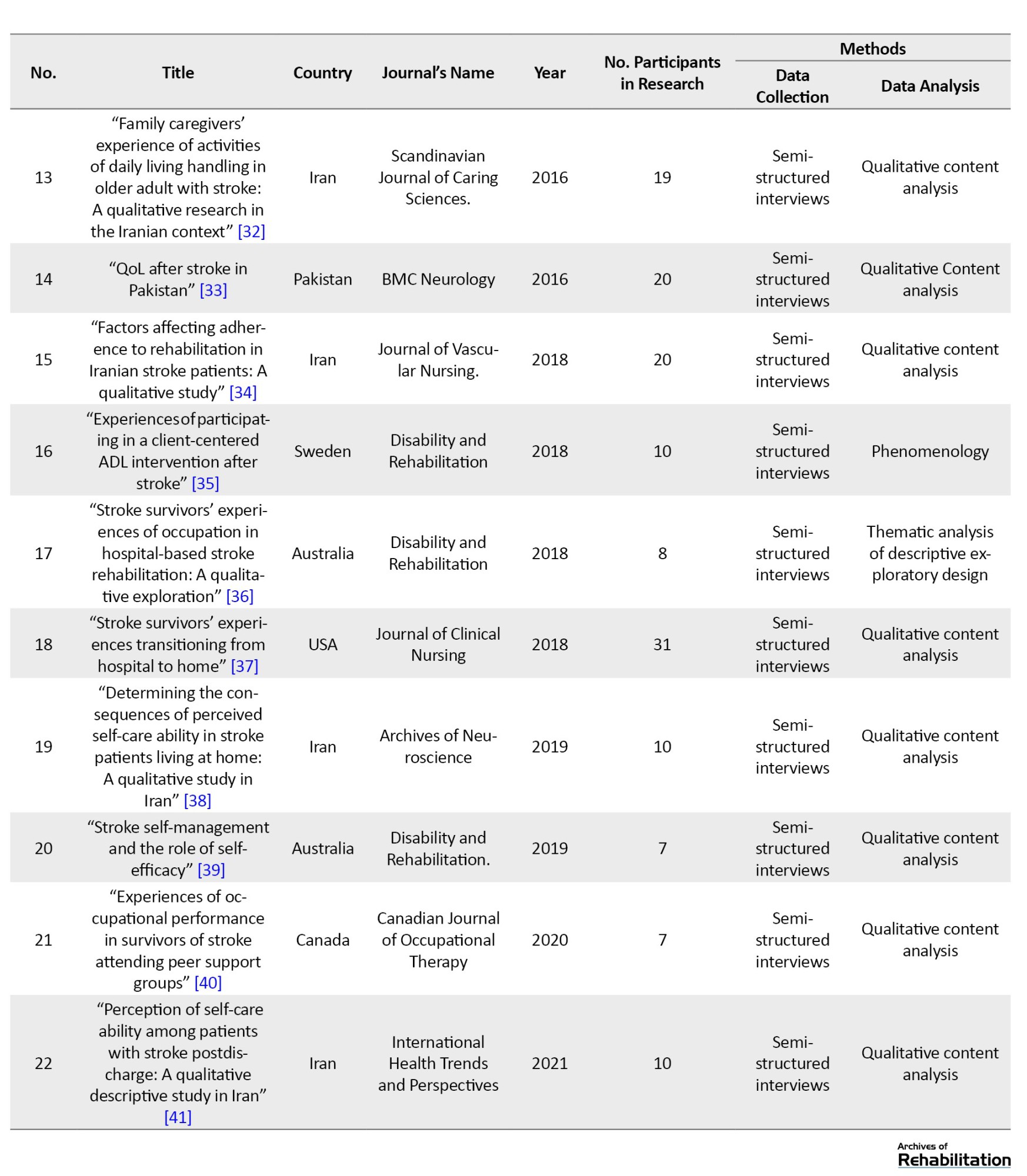

All 22 studies were incorporated into the synthesis. The sample sizes in the studies ranged from 4 to 86 individuals. The cumulative number of participants in the scrutinized articles comprised 400 stroke survivors and their caregivers. Most of the studies were conducted in Iran (Table 5).

The prevalent methodologies were descriptive qualitative, interpretive and grounded theory utilizing semi-structured interviews. This review identified two main categories with six subcategories: 1) Barriers of occupational performance with subclasses of individual barriers, contextual barriers and rehabilitation barriers, 2) Facilitators of occupational performance with subclasses of development of educational strategies, development of environmental support, strengthening of individual strategies (Table 2).

Barriers to occupational performance

Barriers to occupational performance refer to factors that cause limitations in the daily occupational performance of clients. The existence of these barriers has reduced the level of independence of clients and, as a result, can increase the severity of disability. These barriers have led to limitations in their daily living, work, and leisure activities and occupational therapists must consider them. By identifying these barriers, rehabilitation, and occupational therapy specialists can improve clients’ QoL. These barriers may be related to the clients themselves and fundamentally involve them, or may be related to background factors and cause strong effects on a person’s life. Identifying and evaluating these barriers can help reduce the intensity of their impact on the client’s occupational performance. This theme itself was classified into three separate and important subcategories: Individual barriers, contextual barriers, and rehabilitation barriers.

Individual barriers

Physical problems are among an individual’s barriers, which, in terms of physical structure, such as a disorder in the central nervous system, causes problems in the sensory and motor systems (Article 6). Also, these clients may have a series of other underlying diseases and disorders that developed after the stroke and during hospitalization (Article 22). The lack of hand function is a major factor in the client’s inability to perform occupations (Article 6). Loss of mobility and difficulty in walking (Article 6) are other barriers to clients’ physical activity and occupational performance, leading to fatigue (Article 1) and the need for help in their self-care tasks (Article 7). In general, these physical problems have caused the client to fail to meet his occupation’s physical needs and to face problems in continuing his previous job (Article 7). Following a stroke and causing physical problems for the patient, psychological issues also appear and create a lot of tension and psychological pressure for the patient (Articles 22 and 1). These negative feelings cause incompatible adaptive reactions and behaviors (Articles 14 and 22) and disrupt the way to achieve normal occupational performance (Articles 9 and 18). After being discharged from the hospital and returning home, clients feel a big change in their lives, which often has a negative aspect and evokes a negative image of themselves in their minds (Article 11). This issue also causes a feeling of change in occupational needs and demands, which itself is considered a big barrier for occupational performance (Article 11).

Contextual barriers

The context of every person’s life consists of social, cultural, political, economic, and time concerning clients suffering from stroke. This context has a negative role in implementing occupational performance due to many restrictions and barriers. This issue is two-sided: The client cannot perform social roles, and the social support for him is weak. For example, the client cannot perform social roles and feels that he burdens other family members (Articles 3, 6, 9, 22). On the other hand, the absence of familial assistance for individuals and the dearth of interpersonal backing from their social circle impose restrictions on the clients’ social interactions (Articles 1, 3, 4 and 6). The lack of financial support is another barrier and these clients face many economic problems regarding treatment, rehabilitation, and insurance matters (Articles 3, 7, 8 and 15). Cultural and educational barriers are also other contextual barriers. The lack of a suitable training program to strengthen the client’s occupational performance (Articles 3 and 8) and guiding this issue by the family and environment of the clients has magnified its importance. This condition results in insufficient knowledge of the caregivers about the interventions needed to return and strengthen the individual’s occupational performance (Articles 1, 4, 6 and 14).

Rehabilitation barriers

One of the important measures to improve the client’s ability in occupational performance is rehabilitation professions, especially occupational therapy, which, if not implemented well, becomes a significant barrier to the person’s limitations. Among the rehabilitation barriers, we can mention management barriers, such as insufficient availability of rehabilitation services, challenges associated with the rehabilitation team and fundamental gaps in managing this team (Articles 3, 4 and 15). The next issue is the vocational rehabilitation of clients, which this part of rehabilitation refers to returning clients to their previous jobs and maintaining or changing their last jobs. In this part of rehabilitation, many problems arise, such as the mismatch between specific job requirements and the patient’s current capabilities, the inability to maintain the speed required to perform work tasks, the inability to estimate the quality requirements of work, and the employer’s negative attitudes towards the phenomenon of disability (Articles 6, 7, 12). The next issue, which is considered among the areas of rehabilitation, is environmental adaptation and the implementation of adaptation and access plans, which, if not implemented well, will become a big barrier, such as the lack of a public transportation system in the region, the inability to drive to work, and the problems of adapting the workspace (Article 6).

Facilitators of occupational performance

Facilitators of occupational performance are solutions and strategies that strengthen clients’ occupational performance. These strategies can be applied to the individual by the client’s living environment and the surrounding people and family or by the client himself to compensate for the weaknesses. If all of these solutions have a good result, the severity of the client’s disability will be reduced, and occupational performance will be strengthened after discharge from the hospital. A significant percentage of these strategies is increasing the awareness and information of clients and their families. This category is also divided into three separate subcategories. They all try to provide appropriate solutions to strengthen the clients’ working performance, including developing educational strategies, environmental support, and individual strategies.

Development of educational strategies

The development of educational strategies refers to increasing the awareness and information of clients, families, and society to strengthen clients’ occupational performance with sufficient details and correct training. Teaching the patient is one of these strategies that can be used with self-education and adaptation to disability (Article 19). Teaching activities of daily living improves coping and adaptation strategies (Article 10), and it is also possible to increase and maintain a healthy lifestyle by teaching individual independence (Articles 5, 6, 14, 15). Education to caregivers and the community is another essential part of educational strategies that can be tried to increase the family’s health awareness and increase the client’s independence by providing suitable educational programs for stroke patients to the family as well as the primary caregivers of the patient (Articles 3). This training can include training on personal duties, training on client transfer, training on the use of assistive devices, and training on physical movements and physical exercises (Articles 13 and 14). It is emphasized that experts transfer these training pieces to the family and society (Article 2).

Development of environmental support

Considering that man is a social being and all human occupational performance are done in an environmental context, the person and the environment are completely connected and can affect occupational performance. If the environment is rich and provides sufficient support, it will develop the clients’ occupational performance. Social support has different dimensions. The first is financial support, which can be referred to as appropriate financial support after discharge and strengthening of health and supplementary insurance (Articles 1, 2, 3, and 13). The second is social support, such as encouraging the client’s social presence and participation in the community by the family, receiving support through peers, and participating in group meetings with other patients, plays a significant role in helping the client (Articles 13, 14, 20, 21). The third one is environmental support can help a person’s spiritual health and encourage religious activities at home and in the community (Articles 2, 8, 13). Another critical aspect of environmental support is strengthening the rehabilitation system and improving its quality by forming a suitable rehabilitation team to provide comprehensive services to the patient and family for the development of neuromuscular functions and also providing suitable discharge plans for the rehabilitation of the patient after the hospital (Articles 2, 3, 6, 14, 15).

Strengthening of individual strategies

Individual strategies refer to providing solutions to strengthen intra-individual factors. These strategies have strengthened the cognitive and functional performance of the clients. Also, by providing these solutions, it is possible to increase the client’s self-confidence and independence in daily activities. One of these strategies is to improve psychological performance by enhancing the individual’s insight about the need to use existing strategies and facilities, improving the motivation for occupation and increasing the sense of responsibility and having a positive view of the events, the occupational performance of the clients can be enhanced (Articles 2, 6, 8). Based on the findings of studies, the next factor is to facilitate maximum independence in activities of daily living. In this strategy, trying to regain independence, carrying out occupation and activities of daily living to strengthen occupational performance, and creating a balance between rest and recreation in occupational performance can have a good effect in this field (Articles 5, 6, 16, 17).

Discussion

This meta-synthesis revealed that resuming daily occupational activities post-stroke entails a multifaceted journey influenced by various factors that can either hinder or support this transition. Individuals who took part in the research incorporated in this analysis deliberated on the impact of stroke-related consequences as a hindrance to re-engaging in occupational tasks following a stroke. Independent occupational performance in daily life is necessary for individuals who have suffered from a stroke and their caregivers to optimize their overall QoL and effectively deal with their health issues and way of living. This meta-synthesis provides a comprehensive analysis of the insights gained from the viewpoints of stroke survivors, caregivers, and healthcare professionals on the obstacles to occupational performance and the factors that enhance it, taking into account both individual and environmental aspects.

The findings of this study show that the factors that cause challenges in occupational performance and the facilitators of occupational performance during the rehabilitation period after stroke need the attention of the treatment and rehabilitation staff to identify these factors and opportunities. Effective rehabilitation is achieved when specialists use the client’s active collaborative approach to improve occupational performance and to guide clients with stroke and their caregivers to use physical and psychosocial rehabilitation services to meet their needs.

The international classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF) classification system, derived from the biopsychosocial models, thoroughly examines the correlation and interplay between functioning and disability following a stroke, along with personal and environmental influences [42]. The findings of this meta-synthesis confirm that the interaction between physical and psychological disabilities after stroke, social support after discharge, and cultural barriers can disrupt occupational performance and participation in life. People’s health can be improved by creating environments where clients are active and participating actors in that environment. In these environments, people learn how to use their internal and external resources to meet occupational needs in their daily lives, and they are also supported in identifying these resources in the correct way [43].

Internationally, individuals who have experienced a stroke commonly indicate a diminished QoL as a result of various factors such as the financial burden associated with inadequate healthcare services, lifestyle choices, limited access to medical knowledge, environmental and socioeconomic circumstances, and suboptimal compliance with recommended interventions [44, 45]. In African and other developing regions, distinctive elements like limited availability of rehabilitation facilities, inadequate social assistance and care networks, socioeconomic restrictions, ineffective social reintegration initiatives for individuals with disabilities, substandard healthcare services, absence of post-disability home adjustments, as well as cultural and traditional convictions, collectively impact the QoL throughout the process of stroke recovery [44, 46, 47].

According to Brannigan’s study (2017), an adapted environment is one of the primary elements that can help one return to occupational performance. The absence of adequate treatment and rehabilitation services can pose a significant obstacle for individuals recovering from strokes. In fact, there is a necessity to access specialized stroke units during the acute phase to enhance the management of these individuals. Therefore, returning to occupational performance should be considered during rehabilitation, and specialists play an important role in this field [17]. According to the results of this review, the challenges in the field of rehabilitation can be a huge barrier to improving the occupational performance of these clients; these challenges prolong the rehabilitation period and cause the patient to become exhausted. Palmer and Glass (2003) stated that most stroke survivors eventually shift to living in the community. However, many encounter the challenge of undergoing lengthy, arduous, and draining rehabilitation. They argue that the stroke rehabilitation process goes beyond simply regaining muscle strength, range of motion, or enhancing gross movements; instead, it entails a collaborative effort involving reconstructing one’s identity, adopting new roles, and establishing relationships. The ultimate objective of rehabilitation services is to assist stroke patients in attaining a functional capacity level that enables them to resume independent living within the community [48].

Overall, this research agrees with Oswald’s (2008) findings, highlighting the ongoing significance of stroke as a primary concern for individuals who have experienced it, as well as their families and healthcare and social support providers. Most stroke survivors reside within the community and receive assistance from family caregivers, particularly their spouses. Challenges such as stroke-related complications and post-stroke depression can impede recovery progress, resulting in disturbances in relationships and diminished life contentment among clients and their partners. These findings underscore the necessity for novel interventions aimed at aiding stroke survivors and their loved ones in navigating the multifaceted physical, emotional, and environmental adjustments following a stroke, thereby facilitating their successful reintegration into society [49].

According to this review, one of the facilitators of occupational performance is educational strategies that can include both patient and caregiver education. Some level of stroke education is often provided to patients or their family caregivers through rehabilitation programs, yet studies examining the impact of these interventions have been constrained in scope. Variances in educational goals for stroke survivors and educational initiatives are evident across different healthcare facilities. Surprisingly, limited data exist regarding the efficacy of educational programs tailored specifically for stroke patients. A logical initial step in formulating stroke education strategies involves evaluating the educational requirements of both the patient and their family members [48].

A study conducted by the UK Stroke Association on counseling centers revealed that during a 4-month timeframe, around 25% of individuals expressed a desire for more comprehensive insights into stroke characteristics [50]. Among the commonly sought-after types of information by clients are assistance within their homes, involvement in stroke support groups, speech-related issues, rehabilitation programs, alterations in personality, and the presence of depression [48, 50]. Correspondingly, a research endeavor carried out by Van Veenendaal et al. (1996) highlighted similar areas of interest in terms of the educational requirements of stroke patients and their family members, particularly emphasizing the necessity for guidance on methods to mitigate the chances of experiencing a subsequent stroke [51].

According to Langduo Chen (2021), disseminating information regarding complications associated with stroke, management of medications, and lifestyle adjustments to stroke survivors and their caregivers is essential for equipping them with self-care abilities and preventive strategies in addressing risk factors [12]. From the viewpoint of Florence Denby (2016), instructing individuals with a stroke and their families on methods to prevent recurring incidents poses a significant challenge within the realm of rehabilitation. Complexities may arise from staff dynamics, patients’ medical stability, readiness to acquire knowledge, the suitability of educational materials to their specific needs, and the limited timeframe available for educational purposes. During stroke recovery, patient education is an ongoing journey. The training program should consider the individual’s readiness to learn, unique learning styles, and the timing of the sessions. Indeed, stroke rehabilitation represents an educational philosophy that aims to empower patients and their families [52].

According to this review, one way to facilitate clients’ occupational performance is to develop environmental support. This support can take different social, financial, and spiritual dimensions. According to Hanne Peoples, a significant consensus exists regarding the non-physical requirements, such as consideration of the societal repercussions of a stroke, provision of psychological assistance, offering couples therapy, and dissemination of spiritual guidance. The spiritual teachings emphasize the preservation of principles and can be viewed as a foundation of significance and direction for human endeavors.

Consequently, spirituality constitutes a crucial element of an individual’s day-to-day endeavors, and thus, meeting spiritual requirements is imperative for participation in activities and professional empowerment. This aspect may hold particular relevance for individuals recovering from a stroke, who may face constraints in occupational performance yet retain a fundamental necessity to partake in routine tasks [53, 54].

Enhancing individual strategies can facilitate patients’ self-regulation, leading to enhanced psychological functioning and improved performance in everyday tasks. Self-regulation denotes an individual’s capacity to manage a long-standing ailment in cooperation with caregivers, family members, the community, and suitable healthcare professionals. As indicated by the research conducted by Satink (2016), engagement in activities represents a critical domain for enhancing self-regulation and accountability post-stroke. Programs focusing on self-regulation post-stroke can be implemented among stroke survivors, targeting not only the survivors themselves but also their family members. Furthermore, these interventions should not solely concentrate on the functional aspect of activities but also consider the existential dimension of self-regulation post-stroke. By engaging in daily tasks, individuals can observe the implications of their stroke, subsequently acquiring the skills to cope with these consequences in their daily routines, adjusting their expectations, engaging in meaningful activities, and participating in valuable tasks. Moreover, executing daily activities within a defined role can support stroke survivors in deriving lessons from their experiences, acknowledging their capabilities, and attributing new significance to their lives [55].

This meta-synthesis incorporated research from 9 distinct nations, showcasing cultural diversity and methodological orientations. Leveraging this diversity can offer a more extensive perspective on the topic and result in a fresh interpretation of the study results. In most views, the role of clients’ lack of knowledge is colorful, and informing and training clients and their caregivers in occupational performance is a priority. Training clients and caregivers can improve occupational performance and subsequently improve the client’s QoL. The next item is changing and improving the client’s living environment.

It can include the physical environment, such as adapting the client’s home and place of residence, or other social and cultural environments that take steps to improve it with the cooperation of occupational therapists and other rehabilitation and treatment staff and fill the existing gaps by conducting research in this field. Subsequent research endeavors ought to explore issues concerning the return to occupational functioning through the viewpoints of various stakeholders, such as patients, their caregivers, families and the rehabilitation team, including service providers, utilizing a mixed methods strategy. The outcomes of these investigations can enrich our comprehension of the barriers to occupational performance and the interventions that support it, thereby enhancing comprehensive approaches to effective rehabilitation.

Conclusion

Clients with stroke have many barriers in the field of their occupational performance, and especially the barriers related to the context of rehabilitation are of particular importance. In addition to these important barriers, the existence of supportive and educational facilitators can help improve the client’s occupational performance. Educational strategies improve the QoL by enhancing clients’ knowledge and skills in life management, and by improving financial and social support, we can help the clients. A better understanding of the factors affecting the occupational performance of patients with stroke requires more studies, especially in the field of context and rehabilitation issues with the occupational performance of clients.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Supervision: Ghazaleh Mandani; Data collection: Hassan Vahidi and Ghazaleh Mandani; Conceptualization, data analysis, and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all occupational therapists and nurses who helped them in this study.

References

Stroke is an acute neurological event with vascular origin, which leaves lasting and destructive effects on the brain function of the victims. This illness is prevalent, leading to mortality and incapacity, posing a significant issue for the global public health domain [1]. According to the assessment of the World Health Organization (WHO), stroke is “an acute neurological disorder lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death in less than 24 hours” [2]. The frequency of initial stroke occurrence in Iran is recorded at 150 cases per 100000 individuals. The findings from research conducted in Iran indicate a notably elevated prevalence of stroke compared to the majority of Western nations, with a tendency for manifestation at a relatively younger age. The rate of ischemic stroke in Iran also shows a notably elevated rate compared to other geographical areas [3]. Stroke is often experienced as a major disorder in a person’s life and causes tremendous changes in different dimensions of the survivors’ lives [4]. This disorder usually occurs suddenly without warning and leads to major changes in the lives of patients and their families [5].

Upon discharge from the hospital following a stroke, several patients undergo enduring impairments, comprising weakness, balance issues, cognitive impairments, and immobility [6]. All these problems can have destructive effects on occupational performance, particularly the daily activities of individuals affected, which were previously viewed as uncomplicated in their daily routines. Therefore, it is necessary to take all measures required to improve the occupational performance of these people that can facilitate their participation in purposeful activities [7].

Occupational performance can be characterized as the capacity to select, arrange, and effectively engage in significant activities that are culturally determined and suitable for one’s age. It encompasses the ability to attend to one’s needs, derive pleasure from life, and engage in societal participation and interaction within a given community’s social and economic framework [8]. Occupational performance in occupational therapy is one of the main and essential concepts that is also developing and evolving [9]. Recognizing and understanding the various life problems of stroke sufferers can help occupational therapists and other rehabilitation staff [10] to design more effective measures to meet the needs of clients in the field of occupational performance because the improvement in occupational performance after being discharged from the hospital can improve the overall quality of life (QoL) after experiencing a stroke [11].

Numerous investigations have been conducted within the domain of postdischarge care and transitioning to home for individuals who have suffered a stroke, particularly within the discipline of nursing [12]. Studies conducted in other countries using a qualitative approach frequently focus on delineating various aspects, such as the patient’s recovery and expectations from the recovery period after a stroke, understanding society’s thoughts about stroke disease, or understanding the patient’s fatigue after a stroke. From Chen’s (2021) perspective, the passage from hospitalization to home constitutes a complex phase in the process of rehabilitation and recovery following a stroke. Additional investigations are essential to enhance comprehension of the viewpoints held by various parties involved and to tackle unaddressed requirements in transitional healthcare [12].

Many individuals who have experienced a stroke and are released from medical facilities to continue their rehabilitation and recovery process at home encounter a multitude of obstacles related to home care [13]. Most stroke survivors enter an environment that presents many challenges when they return home, and occupational therapy to reduce these challenges is often prescribed to stroke survivors to enhance the shift from medical facility to home [14]. From Simeone’s (2015) perspective, the treatment and rehabilitation team should improve their interventions to support survivors in effectively managing the impactful changes in their post-stroke lives, while also motivating them to adjust to the challenges that arise in their daily activities due to the stroke [15].

Cobley (2013) stated in her study, based on the experience of patients, that failure to pursue rehabilitation puts them in danger. An apparent discrepancy was evident in the delivery of rehabilitation services between the period of hospitalization and the phase in the community. The prolonged waiting period for community-based rehabilitation programs, which certain survivors encountered, directly influenced the attainment of their objectives [16].

Brannigan (2017) concluded that resuming occupational performance following a stroke is intricate and can be influenced positively or negatively by factors within the organization, social environment, personal characteristics and the availability of suitable services. The consequences of a stroke, such as fatigue and various other elements, influence the reintegration into post-stroke occupational performance. Collaborative communication among healthcare providers and interdisciplinary team members may facilitate the reintegration process for individuals who have experienced a stroke. Furthermore, environmental modifications and activity adjustments are among the enabling factors that can support the integration of stroke survivors into their living environment [17].

Numerous research endeavors have been conducted concerning the challenges of post-hospital care for individuals who have survived a stroke [12]. Nevertheless, there is a notable scarcity of meta-synthesized research findings about the daily occupational performance of stroke patients and their caregivers following discharge within the realm of occupational therapy. This knowledge gap is further exacerbated by the predominant focus of existing studies on nursing, with a limited exploration from the vantage point of the occupational therapy discipline. This meta-synthesis tries to fill this gap. The outcomes of this study contribute to an enhanced comprehension of occupational performance post-stroke, gaining insight into the challenges and requirements of individuals affected by this condition and their support system and creating interventions focused on the individual. This meta-synthesis review aimed to combine qualitative research outcomes regarding the firsthand encounters of individuals who have suffered from stroke and their caregivers concerning occupational performance following a stroke.

Materials and Methods

This review employs a meta-synthesis methodology defined by Edwards and Kaimal (2016), which extracts qualitative data from different articles, integrates them, and then creates new data and results [18]. Despite the variations in methodologies utilized in different categories of literary examinations, all reviews can be conducted by adhering to 8 fundamental steps: 1) Articulation of the research inquiry, 2) Establishment and authentication of the review protocol, 3) Retrieval of relevant articles, 4) Evaluation for the inclusion of studies, 5) Assessment of quality, 6) Extraction of data, 7) Analysis and synthesis of data and 8) Presentation of findings [19]. All these steps have been followed in this study. The articles were searched after formulating the research question and developing the review protocol. After screening for the inclusion criteria, the research quality was assessed using the critical appraisal skills program (CASP) questionnaire. The data have been extracted and analyzed, and the findings are reported in this study (Table 1).

In this review, three important points were noted; the first thing is what experience clients with stroke had throughout their hospital stay and following their release from the medical facility in connection to their disability. The next thing is how these clients performed the tasks related to self-care after living with the problem of stroke and what experience their caregivers have in this field. The last thing is how, after recovery, the client’s occupational performance regarding returning to the former job has been affected. Therefore, after repeatedly reading and analyzing the articles in the results section, each article was analyzed line by line, and the meaning units were extracted from the articles’ text based on the research purpose. Then, the meaning units were converted into codes, and in the third stage, the classification of codes began until finally, classes and sub-classes were formed, and codes similar to each other were placed in one class. These classes were revised several times to compare with each other and form newer classes. At first, after analyzing the studies, 163 primary codes were extracted, which were reduced to 126 after rechecking their similarity to each other after grouping them. They were divided into 2 main groups: Occupational performance barriers and occupational performance facilitators (Table 2).

The keywords used in this study were the following: “occupational performance,” “self-care,” “activity of daily living,” “work,” “stroke,” “adult hemiplegia” and “qualitative research.” The search databases include CINAHL, PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus until 2023. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study are also summarized in Table 3.

Quality assessment

To guarantee the validity of the data employed, the instrument known as the CASP [20]. This instrument comprises a set of 10 inquiries designed to assess the caliber of research works for which the researcher has employed this survey in all publications (Table 4).

The results of this study were presented and discussed so that some practical guidance could be received for Tabriz University of Medical Sciences Nursing Researchers, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Occupational Therapy Department, and University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences. Classification using predetermined categories and precise definitions, along with the dependability of coding, enhances the internal validity of the results. Extracting the context and forming theoretical abstractions from the outcomes of content analysis enables a certain level of generalizability of the results, thereby enhancing external validity [21]. In general, strategies for building trust in qualitative research were considered in this study. All authors read the articles independently, and during the analysis of classes and units of meaning, they repeatedly discussed them until they reached the final classes and subclasses.

Results

All 22 studies were incorporated into the synthesis. The sample sizes in the studies ranged from 4 to 86 individuals. The cumulative number of participants in the scrutinized articles comprised 400 stroke survivors and their caregivers. Most of the studies were conducted in Iran (Table 5).

The prevalent methodologies were descriptive qualitative, interpretive and grounded theory utilizing semi-structured interviews. This review identified two main categories with six subcategories: 1) Barriers of occupational performance with subclasses of individual barriers, contextual barriers and rehabilitation barriers, 2) Facilitators of occupational performance with subclasses of development of educational strategies, development of environmental support, strengthening of individual strategies (Table 2).

Barriers to occupational performance

Barriers to occupational performance refer to factors that cause limitations in the daily occupational performance of clients. The existence of these barriers has reduced the level of independence of clients and, as a result, can increase the severity of disability. These barriers have led to limitations in their daily living, work, and leisure activities and occupational therapists must consider them. By identifying these barriers, rehabilitation, and occupational therapy specialists can improve clients’ QoL. These barriers may be related to the clients themselves and fundamentally involve them, or may be related to background factors and cause strong effects on a person’s life. Identifying and evaluating these barriers can help reduce the intensity of their impact on the client’s occupational performance. This theme itself was classified into three separate and important subcategories: Individual barriers, contextual barriers, and rehabilitation barriers.

Individual barriers

Physical problems are among an individual’s barriers, which, in terms of physical structure, such as a disorder in the central nervous system, causes problems in the sensory and motor systems (Article 6). Also, these clients may have a series of other underlying diseases and disorders that developed after the stroke and during hospitalization (Article 22). The lack of hand function is a major factor in the client’s inability to perform occupations (Article 6). Loss of mobility and difficulty in walking (Article 6) are other barriers to clients’ physical activity and occupational performance, leading to fatigue (Article 1) and the need for help in their self-care tasks (Article 7). In general, these physical problems have caused the client to fail to meet his occupation’s physical needs and to face problems in continuing his previous job (Article 7). Following a stroke and causing physical problems for the patient, psychological issues also appear and create a lot of tension and psychological pressure for the patient (Articles 22 and 1). These negative feelings cause incompatible adaptive reactions and behaviors (Articles 14 and 22) and disrupt the way to achieve normal occupational performance (Articles 9 and 18). After being discharged from the hospital and returning home, clients feel a big change in their lives, which often has a negative aspect and evokes a negative image of themselves in their minds (Article 11). This issue also causes a feeling of change in occupational needs and demands, which itself is considered a big barrier for occupational performance (Article 11).

Contextual barriers

The context of every person’s life consists of social, cultural, political, economic, and time concerning clients suffering from stroke. This context has a negative role in implementing occupational performance due to many restrictions and barriers. This issue is two-sided: The client cannot perform social roles, and the social support for him is weak. For example, the client cannot perform social roles and feels that he burdens other family members (Articles 3, 6, 9, 22). On the other hand, the absence of familial assistance for individuals and the dearth of interpersonal backing from their social circle impose restrictions on the clients’ social interactions (Articles 1, 3, 4 and 6). The lack of financial support is another barrier and these clients face many economic problems regarding treatment, rehabilitation, and insurance matters (Articles 3, 7, 8 and 15). Cultural and educational barriers are also other contextual barriers. The lack of a suitable training program to strengthen the client’s occupational performance (Articles 3 and 8) and guiding this issue by the family and environment of the clients has magnified its importance. This condition results in insufficient knowledge of the caregivers about the interventions needed to return and strengthen the individual’s occupational performance (Articles 1, 4, 6 and 14).

Rehabilitation barriers

One of the important measures to improve the client’s ability in occupational performance is rehabilitation professions, especially occupational therapy, which, if not implemented well, becomes a significant barrier to the person’s limitations. Among the rehabilitation barriers, we can mention management barriers, such as insufficient availability of rehabilitation services, challenges associated with the rehabilitation team and fundamental gaps in managing this team (Articles 3, 4 and 15). The next issue is the vocational rehabilitation of clients, which this part of rehabilitation refers to returning clients to their previous jobs and maintaining or changing their last jobs. In this part of rehabilitation, many problems arise, such as the mismatch between specific job requirements and the patient’s current capabilities, the inability to maintain the speed required to perform work tasks, the inability to estimate the quality requirements of work, and the employer’s negative attitudes towards the phenomenon of disability (Articles 6, 7, 12). The next issue, which is considered among the areas of rehabilitation, is environmental adaptation and the implementation of adaptation and access plans, which, if not implemented well, will become a big barrier, such as the lack of a public transportation system in the region, the inability to drive to work, and the problems of adapting the workspace (Article 6).

Facilitators of occupational performance

Facilitators of occupational performance are solutions and strategies that strengthen clients’ occupational performance. These strategies can be applied to the individual by the client’s living environment and the surrounding people and family or by the client himself to compensate for the weaknesses. If all of these solutions have a good result, the severity of the client’s disability will be reduced, and occupational performance will be strengthened after discharge from the hospital. A significant percentage of these strategies is increasing the awareness and information of clients and their families. This category is also divided into three separate subcategories. They all try to provide appropriate solutions to strengthen the clients’ working performance, including developing educational strategies, environmental support, and individual strategies.

Development of educational strategies

The development of educational strategies refers to increasing the awareness and information of clients, families, and society to strengthen clients’ occupational performance with sufficient details and correct training. Teaching the patient is one of these strategies that can be used with self-education and adaptation to disability (Article 19). Teaching activities of daily living improves coping and adaptation strategies (Article 10), and it is also possible to increase and maintain a healthy lifestyle by teaching individual independence (Articles 5, 6, 14, 15). Education to caregivers and the community is another essential part of educational strategies that can be tried to increase the family’s health awareness and increase the client’s independence by providing suitable educational programs for stroke patients to the family as well as the primary caregivers of the patient (Articles 3). This training can include training on personal duties, training on client transfer, training on the use of assistive devices, and training on physical movements and physical exercises (Articles 13 and 14). It is emphasized that experts transfer these training pieces to the family and society (Article 2).

Development of environmental support

Considering that man is a social being and all human occupational performance are done in an environmental context, the person and the environment are completely connected and can affect occupational performance. If the environment is rich and provides sufficient support, it will develop the clients’ occupational performance. Social support has different dimensions. The first is financial support, which can be referred to as appropriate financial support after discharge and strengthening of health and supplementary insurance (Articles 1, 2, 3, and 13). The second is social support, such as encouraging the client’s social presence and participation in the community by the family, receiving support through peers, and participating in group meetings with other patients, plays a significant role in helping the client (Articles 13, 14, 20, 21). The third one is environmental support can help a person’s spiritual health and encourage religious activities at home and in the community (Articles 2, 8, 13). Another critical aspect of environmental support is strengthening the rehabilitation system and improving its quality by forming a suitable rehabilitation team to provide comprehensive services to the patient and family for the development of neuromuscular functions and also providing suitable discharge plans for the rehabilitation of the patient after the hospital (Articles 2, 3, 6, 14, 15).

Strengthening of individual strategies

Individual strategies refer to providing solutions to strengthen intra-individual factors. These strategies have strengthened the cognitive and functional performance of the clients. Also, by providing these solutions, it is possible to increase the client’s self-confidence and independence in daily activities. One of these strategies is to improve psychological performance by enhancing the individual’s insight about the need to use existing strategies and facilities, improving the motivation for occupation and increasing the sense of responsibility and having a positive view of the events, the occupational performance of the clients can be enhanced (Articles 2, 6, 8). Based on the findings of studies, the next factor is to facilitate maximum independence in activities of daily living. In this strategy, trying to regain independence, carrying out occupation and activities of daily living to strengthen occupational performance, and creating a balance between rest and recreation in occupational performance can have a good effect in this field (Articles 5, 6, 16, 17).

Discussion

This meta-synthesis revealed that resuming daily occupational activities post-stroke entails a multifaceted journey influenced by various factors that can either hinder or support this transition. Individuals who took part in the research incorporated in this analysis deliberated on the impact of stroke-related consequences as a hindrance to re-engaging in occupational tasks following a stroke. Independent occupational performance in daily life is necessary for individuals who have suffered from a stroke and their caregivers to optimize their overall QoL and effectively deal with their health issues and way of living. This meta-synthesis provides a comprehensive analysis of the insights gained from the viewpoints of stroke survivors, caregivers, and healthcare professionals on the obstacles to occupational performance and the factors that enhance it, taking into account both individual and environmental aspects.

The findings of this study show that the factors that cause challenges in occupational performance and the facilitators of occupational performance during the rehabilitation period after stroke need the attention of the treatment and rehabilitation staff to identify these factors and opportunities. Effective rehabilitation is achieved when specialists use the client’s active collaborative approach to improve occupational performance and to guide clients with stroke and their caregivers to use physical and psychosocial rehabilitation services to meet their needs.

The international classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF) classification system, derived from the biopsychosocial models, thoroughly examines the correlation and interplay between functioning and disability following a stroke, along with personal and environmental influences [42]. The findings of this meta-synthesis confirm that the interaction between physical and psychological disabilities after stroke, social support after discharge, and cultural barriers can disrupt occupational performance and participation in life. People’s health can be improved by creating environments where clients are active and participating actors in that environment. In these environments, people learn how to use their internal and external resources to meet occupational needs in their daily lives, and they are also supported in identifying these resources in the correct way [43].

Internationally, individuals who have experienced a stroke commonly indicate a diminished QoL as a result of various factors such as the financial burden associated with inadequate healthcare services, lifestyle choices, limited access to medical knowledge, environmental and socioeconomic circumstances, and suboptimal compliance with recommended interventions [44, 45]. In African and other developing regions, distinctive elements like limited availability of rehabilitation facilities, inadequate social assistance and care networks, socioeconomic restrictions, ineffective social reintegration initiatives for individuals with disabilities, substandard healthcare services, absence of post-disability home adjustments, as well as cultural and traditional convictions, collectively impact the QoL throughout the process of stroke recovery [44, 46, 47].

According to Brannigan’s study (2017), an adapted environment is one of the primary elements that can help one return to occupational performance. The absence of adequate treatment and rehabilitation services can pose a significant obstacle for individuals recovering from strokes. In fact, there is a necessity to access specialized stroke units during the acute phase to enhance the management of these individuals. Therefore, returning to occupational performance should be considered during rehabilitation, and specialists play an important role in this field [17]. According to the results of this review, the challenges in the field of rehabilitation can be a huge barrier to improving the occupational performance of these clients; these challenges prolong the rehabilitation period and cause the patient to become exhausted. Palmer and Glass (2003) stated that most stroke survivors eventually shift to living in the community. However, many encounter the challenge of undergoing lengthy, arduous, and draining rehabilitation. They argue that the stroke rehabilitation process goes beyond simply regaining muscle strength, range of motion, or enhancing gross movements; instead, it entails a collaborative effort involving reconstructing one’s identity, adopting new roles, and establishing relationships. The ultimate objective of rehabilitation services is to assist stroke patients in attaining a functional capacity level that enables them to resume independent living within the community [48].

Overall, this research agrees with Oswald’s (2008) findings, highlighting the ongoing significance of stroke as a primary concern for individuals who have experienced it, as well as their families and healthcare and social support providers. Most stroke survivors reside within the community and receive assistance from family caregivers, particularly their spouses. Challenges such as stroke-related complications and post-stroke depression can impede recovery progress, resulting in disturbances in relationships and diminished life contentment among clients and their partners. These findings underscore the necessity for novel interventions aimed at aiding stroke survivors and their loved ones in navigating the multifaceted physical, emotional, and environmental adjustments following a stroke, thereby facilitating their successful reintegration into society [49].

According to this review, one of the facilitators of occupational performance is educational strategies that can include both patient and caregiver education. Some level of stroke education is often provided to patients or their family caregivers through rehabilitation programs, yet studies examining the impact of these interventions have been constrained in scope. Variances in educational goals for stroke survivors and educational initiatives are evident across different healthcare facilities. Surprisingly, limited data exist regarding the efficacy of educational programs tailored specifically for stroke patients. A logical initial step in formulating stroke education strategies involves evaluating the educational requirements of both the patient and their family members [48].

A study conducted by the UK Stroke Association on counseling centers revealed that during a 4-month timeframe, around 25% of individuals expressed a desire for more comprehensive insights into stroke characteristics [50]. Among the commonly sought-after types of information by clients are assistance within their homes, involvement in stroke support groups, speech-related issues, rehabilitation programs, alterations in personality, and the presence of depression [48, 50]. Correspondingly, a research endeavor carried out by Van Veenendaal et al. (1996) highlighted similar areas of interest in terms of the educational requirements of stroke patients and their family members, particularly emphasizing the necessity for guidance on methods to mitigate the chances of experiencing a subsequent stroke [51].

According to Langduo Chen (2021), disseminating information regarding complications associated with stroke, management of medications, and lifestyle adjustments to stroke survivors and their caregivers is essential for equipping them with self-care abilities and preventive strategies in addressing risk factors [12]. From the viewpoint of Florence Denby (2016), instructing individuals with a stroke and their families on methods to prevent recurring incidents poses a significant challenge within the realm of rehabilitation. Complexities may arise from staff dynamics, patients’ medical stability, readiness to acquire knowledge, the suitability of educational materials to their specific needs, and the limited timeframe available for educational purposes. During stroke recovery, patient education is an ongoing journey. The training program should consider the individual’s readiness to learn, unique learning styles, and the timing of the sessions. Indeed, stroke rehabilitation represents an educational philosophy that aims to empower patients and their families [52].

According to this review, one way to facilitate clients’ occupational performance is to develop environmental support. This support can take different social, financial, and spiritual dimensions. According to Hanne Peoples, a significant consensus exists regarding the non-physical requirements, such as consideration of the societal repercussions of a stroke, provision of psychological assistance, offering couples therapy, and dissemination of spiritual guidance. The spiritual teachings emphasize the preservation of principles and can be viewed as a foundation of significance and direction for human endeavors.

Consequently, spirituality constitutes a crucial element of an individual’s day-to-day endeavors, and thus, meeting spiritual requirements is imperative for participation in activities and professional empowerment. This aspect may hold particular relevance for individuals recovering from a stroke, who may face constraints in occupational performance yet retain a fundamental necessity to partake in routine tasks [53, 54].

Enhancing individual strategies can facilitate patients’ self-regulation, leading to enhanced psychological functioning and improved performance in everyday tasks. Self-regulation denotes an individual’s capacity to manage a long-standing ailment in cooperation with caregivers, family members, the community, and suitable healthcare professionals. As indicated by the research conducted by Satink (2016), engagement in activities represents a critical domain for enhancing self-regulation and accountability post-stroke. Programs focusing on self-regulation post-stroke can be implemented among stroke survivors, targeting not only the survivors themselves but also their family members. Furthermore, these interventions should not solely concentrate on the functional aspect of activities but also consider the existential dimension of self-regulation post-stroke. By engaging in daily tasks, individuals can observe the implications of their stroke, subsequently acquiring the skills to cope with these consequences in their daily routines, adjusting their expectations, engaging in meaningful activities, and participating in valuable tasks. Moreover, executing daily activities within a defined role can support stroke survivors in deriving lessons from their experiences, acknowledging their capabilities, and attributing new significance to their lives [55].

This meta-synthesis incorporated research from 9 distinct nations, showcasing cultural diversity and methodological orientations. Leveraging this diversity can offer a more extensive perspective on the topic and result in a fresh interpretation of the study results. In most views, the role of clients’ lack of knowledge is colorful, and informing and training clients and their caregivers in occupational performance is a priority. Training clients and caregivers can improve occupational performance and subsequently improve the client’s QoL. The next item is changing and improving the client’s living environment.

It can include the physical environment, such as adapting the client’s home and place of residence, or other social and cultural environments that take steps to improve it with the cooperation of occupational therapists and other rehabilitation and treatment staff and fill the existing gaps by conducting research in this field. Subsequent research endeavors ought to explore issues concerning the return to occupational functioning through the viewpoints of various stakeholders, such as patients, their caregivers, families and the rehabilitation team, including service providers, utilizing a mixed methods strategy. The outcomes of these investigations can enrich our comprehension of the barriers to occupational performance and the interventions that support it, thereby enhancing comprehensive approaches to effective rehabilitation.

Conclusion

Clients with stroke have many barriers in the field of their occupational performance, and especially the barriers related to the context of rehabilitation are of particular importance. In addition to these important barriers, the existence of supportive and educational facilitators can help improve the client’s occupational performance. Educational strategies improve the QoL by enhancing clients’ knowledge and skills in life management, and by improving financial and social support, we can help the clients. A better understanding of the factors affecting the occupational performance of patients with stroke requires more studies, especially in the field of context and rehabilitation issues with the occupational performance of clients.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

There were no ethical considerations to be considered in this research.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Supervision: Ghazaleh Mandani; Data collection: Hassan Vahidi and Ghazaleh Mandani; Conceptualization, data analysis, and writing: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all occupational therapists and nurses who helped them in this study.

References

- Geyh S, Cieza A, Schouten J, Dickson H, Frommelt P, Omar Z, et al. ICF Core Sets for stroke. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2004; (44 Suppl):135-41. [DOI:10.1080/16501960410016776] [PMID]

- WHO. ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders (The) Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992. [Link]

- Azarpazhooh MR, Etemadi MM, Donnan GA, Mokhber N, Majdi MR, Ghayour-Mobarhan M, et al. Excessive incidence of stroke in Iran: Evidence from the Mashhad Stroke Incidence Study (MSIS), a population-based study of stroke in the Middle East. Stroke. 2010; 41(1):e3-10. [DOI:10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.559708] [PMID]

- Husserl E. The crisis of European sciences and transcendental phenomenology: An introduction to phenomenological philosophy. Illinois: Northwestern University Press; 1970. [Link]

- Larson J, Franzén-Dahlin A, Billing E, von Arbin M, Murray V, Wredling R. The impact of gender regarding psychological well-being and general life situation among spouses of stroke patients during the first year after the patients’ stroke event: A longitudinal study. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2008; 45(2):257-65. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2006.08.021] [PMID]

- Perry SB, Marchetti GF, Wagner S, Wilton W. Predicting caregiver assistance required for sit-to-stand following rehabilitation for acute stroke. Journal of Neurologic Physical Therapy. 2006; 30(1):2-11. [DOI:10.1097/01.NPT.0000282144.72703.cb] [PMID]

- Fisher AG. Occupational therapy intervention process model: A model for planning and implementing top-down, client-centered and occupation-based interventions. Three Star Press; 2009. [Link]

- Rebeiro KL, Polgar JM. Enabling occupational performance: Optimal experiences in therapy. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 1999; 66(1):14-22. [DOI:10.1177/000841749906600102] [PMID]

- Crabtree J. On occupational performance. Occupational Therapy in Health Care. 2003; 17(2):1-18. [DOI:10.1080/J003v17n02_01] [PMID]

- Yeung SM, Wong FK, Mok E. Holistic concerns of Chinese stroke survivors during hospitalization and in transition to home. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011; 67(11):2394-405. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05673.x] [PMID]

- Bourland EL, Neville MA, Pickens ND. Loss, gain, and the reframing of perspectives in long-term stroke survivors: A dynamic experience of quality of life. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2011; 18(5):437-49. [DOI:10.1310/tsr1805-437] [PMID]

- Chen L, Xiao LD, Chamberlain D, Newman P. Enablers and barriers in hospital -to-home transitional care for stroke survivors and caregivers: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2021; 30(19-20):2786-807. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.15807] [PMID]

- Lindblom S, Ytterberg C, Elf M, Flink M. Perceptive dialogue for linking stakeholders and units during care transitions-a qualitative study of people with stroke, significant others and healthcare professionals in Sweden. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2020; 20(1):11. [DOI:10.5334/ijic.4689] [PMID]

- Schulz CH, Hersch GI, Foust JL, Wyatt AL, Godwin KM, Virani S, et al. Identifying occupational performance barriers of stroke survivors: Utilization of a home assessment. Physical & occupational Therapy in Geriatrics. 2012; 30(2):10.3109/02703181.2012.687441. [DOI:10.3109/02703181.2012.687441] [PMID]

- Simeone S, Savini S, Cohen MZ, Alvaro R, Vellone E. The experience of stroke survivors three months after being discharged home: A phenomenological investigation. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2015; 14(2):162-9. [DOI:10.1177/1474515114522886] [PMID]

- Cobley CS, Fisher RJ, Chouliara N, Kerr M, Walker MF. A qualitative study exploring patients’ and carers’ experiences of Early Supported Discharge services after stroke. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2013; 27(8):750-7. [DOI:10.1177/0269215512474030] [PMID]

- Brannigan C, Galvin R, Walsh ME, Loughnane C, Morrissey EJ, Macey C, et al. Barriers and facilitators associated with return to work after stroke: A qualitative meta-synthesis. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2017; 39(3):211-22. [DOI:10.3109/09638288.2016.1141242] [PMID]

- Edwards J, Kaimal G. Using meta-synthesis to support application of qualitative methods findings in practice: A discussion of meta-ethnography, narrative synthesis, and critical interpretive synthesis. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2016; 51:30-5. [DOI:10.1016/j.aip.2016.07.003]

- Xiao Y, Watson M. Guidance on conducting a systematic literature review. Journal of Planning Education and Research. 2019; 39(1):93-112. [DOI:10.1177/0739456X17723971]

- Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences. 2020; 1(1):31-42. [DOI:10.1177/2632084320947559]

- Avenier MJ. Shaping a constructivist view of organizational design science. Organization Studies. 2010; 31(9-10):1229-55. [DOI:10.1177/0170840610374395]

- Röding J, Lindström B, Malm J, Öhman A. Frustrated and invisible--younger stroke patients’ experiences of the rehabilitation process. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2003; 25(15):867-74. [DOI:10.1080/0963828031000122276] [PMID]

- Dalvandi A, Ekman SL, Maddah SS, Khankeh HR, Heikkilä K. Post Stroke life in Iranian people: Used and recommended strategies. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2009; 7(1):17-24. [Link]

- Dalvandi A, Heikkilä K, Maddah SS, Khankeh HR, Ekman SL. Life experiences after stroke among Iranian stroke survivors. International Nursing Review. 2010; 57(2):247-53. [DOI:10.1111/j.1466-7657.2009.00786.x] [PMID]

- Ekstam L, Tham K, Borell L. Couples’ approaches to changes in everyday life during the first year after stroke. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2011; 18(1):49-58. [DOI:10.3109/11038120903578791] [PMID]

- Culler KH, Wang YC, Byers K, Trierweiler R. Barriers and facilitators of return to work for individuals with strokes: Perspectives of the stroke survivor, vocational specialist, and employer. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2011; 18(4):325-40. [DOI:10.1310/tsr1804-325] [PMID]

- Hartke RJ, Trierweiler R, Bode R. Critical factors related to return to work after stroke: A qualitative study. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation. 2011; 18(4):341-51. [DOI:10.1310/tsr1804-341] [PMID]

- Dalvandi A, Khankeh HR, Ekman S-L, Maddah SSB, Heikkilä K. Everyday life condition in stroke survivors and their family caregivers in Iranian context. International Journal of Community Based Nursing & Midwifery. 2013; 1(1):3-15. [Link]

- Ekstam L, Johansson U, Guidetti S, Eriksson G, Ytterberg C. The combined perceptions of people with stroke and their carers regarding rehabilitation needs 1 year after stroke: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2015; 5(2):e006784. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006784] [PMID]

- Taule T, Strand LI, Skouen JS, Råheim M. Striving for a life worth living: stroke survivors’ experiences of home rehabilitation. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences. 2015; 29(4):651-61. [DOI:10.1111/scs.12193] [PMID]