Volume 25, Issue 1 (Spring 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(1): 26-47 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sabour Eghbali Mostafa Khan H, Akbar Fahimi N, Hosseini S A. Early Rehabilitation Interventions in Improving Neuromotor Skills of Preterm Infants in the Intensive Care Unit: A Scoping Review. jrehab 2024; 25 (1) :26-47

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3351-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3351-en.html

1- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., kodakyar st,daneshjo blvd,evin,tehran,iran

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,fahimi1970@yahoo.com

2- Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Keywords: Preterm infants, Physiotherapy, Occupational therapy, Early intervention, Sensory stimulation, Play

Full-Text [PDF 3515 kb]

(1593 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (3916 Views)

Full-Text: (1585 Views)

Introduction

According to the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO), infants who are born before 37 weeks of pregnancy are called premature or preterm, and based on the gestational age, they are divided into three subgroups: Extreme preterm (under 28 weeks), very preterm (28-32 weeks) and moderate to late preterm (32-37) are classified [1].

Platt et al. (2014) highlighted that preterm birth is a common issue worldwide, with an estimated 10% of all of births being preterm. Preterm infants are more prone to face short-term and long-term neurodevelopmental disorders due to intrauterine growth interruption and hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) [2]. In fact, a recent study showed that more than 25% of neonates born between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation have developmental disorders at the age of 2 years old, and this ratio reaches 40% at the age of 10 [3]. but even infants who are free of major neurodevelopmental delays are still at a higher risk of poor motor outcomes, such as subtle deficits in eye-hand coordination, sensory-motor integration, manual dexterity, and gross motor skills [4]. If these difficulties persist, integration and performance at school can be affected, leading to lower self-esteem [5].

The human brain in infancy is highly plastic and there is an active growth of dendrites and formation of synapses. Experience influences and models the brain and leads to structural changes in, e.g. the number of synapses that are developed, the synapses’ position and functioning, as well as elimination of synapses that are not needed [6]. Motor skills may be highly influenced by early intervention because the motor pathways forming the corticospinal tracts already show mature myelin at term age and myelination may be activity-dependent [7].There is some evidence that recovery from central nervous system injury in infants can be understood both by new growth of motor neurons and creation of new synapses [8]. Of these insights about brain plasticity it is suggested that early-targeted customized individual intervention could be of great importance to the development of movement quality and function of preterm children.

Evidence-based, effective early intervention programs are needed to target early motor abilities that support motor and cognitive development in infants at high risk of having cerebral palsy or minor neurological dysfunctions. Motor and cognitive development are tightly coupled, suggesting that delays in one domain could contribute to delays in other domains [9]. Motor experience provides infants an opportunity to learn about objects and interaction supports development in multiple domains [10]. Motor activity contributes to the infants attempts to attend to the environment, allowing the infant to receive and interpret important information, and solve problems by linking the mind and body in a cycle that supports development [11].

A recent Cochrane review of early developmental intervention programs to prevent motor and cognitive impairment highlighted the impact that even a minor motor impairment can have on a child and concluded that effective activities to enhance the motor skills of preterm infants need to be identified [12].

Since the evidence about rehabilitation interventions in improving the motor development of preterm infants is diverse and scattered and there is heterogeneity in the amount, time and type of therapeutic interventions, the purpose of this study is to summarize and identify the types of rehabilitation interventions (occupational therapy and physiotherapy) with the aim Improving the motor skills of infants admitted to the intensive care unit. In this way, the course of research in this field has become clear, therapeutic interventions that need more research and study are identified, and suggestions for future studies are presented.

Materials and Methods

The Scoping Review method is a structured method to obtain useful background information and find gaps in the literature. In the current study, this method was used, which was presented by Arksey et al. in 5 steps [13] and includes the following:

Identifying of the research question

The questions of the present research were: How many occupational therapy and physiotherapy intervention studies have been related to the motor development of preterm infants? What kind of treatment approaches have been used in these studies?

Identifying relevant studies

In this study, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar search engine databases were used to collect information with an advanced search strategy.

Sample syntax in PubMed

A) Preterm infants[Title/Abstract] OR premature infants[Title/Abstract] OR neonates

B) Occupational therapy[Title/Abstract] OR physiotherapy [Title/Abstract] OR early intervention OR sensory stimulation[Title/Abstract] OR play [Title]

C) A AND B

Study selection

The inclusion criteria included articles that were published in English and Farsi, were the main subject of occupational therapy and physiotherapy studies on motor skills of preterm infants, and were published between 2000 and 2023. The exclusion criteria were review studies and studies other than clinical trials.

Steps for selecting studies

After entering keywords and searching, duplicate articles were removed using endnote software, and then studies whose titles did not match the inclusion criteria were removed. In the remaining studies, the review abstract and a number of studies were excluded due to non-compliance with the inclusion criteria. After that, the remaining articles were examined in full text in detail, and at the end, studies that did not present an intervention or did not provide a proper description of the implementation of the interventions were excluded. All steps were done separately by two independent researchers. The results of each stage were discussed by two researchers, and in cases of disagreement, decisions were made with the agreement of both.

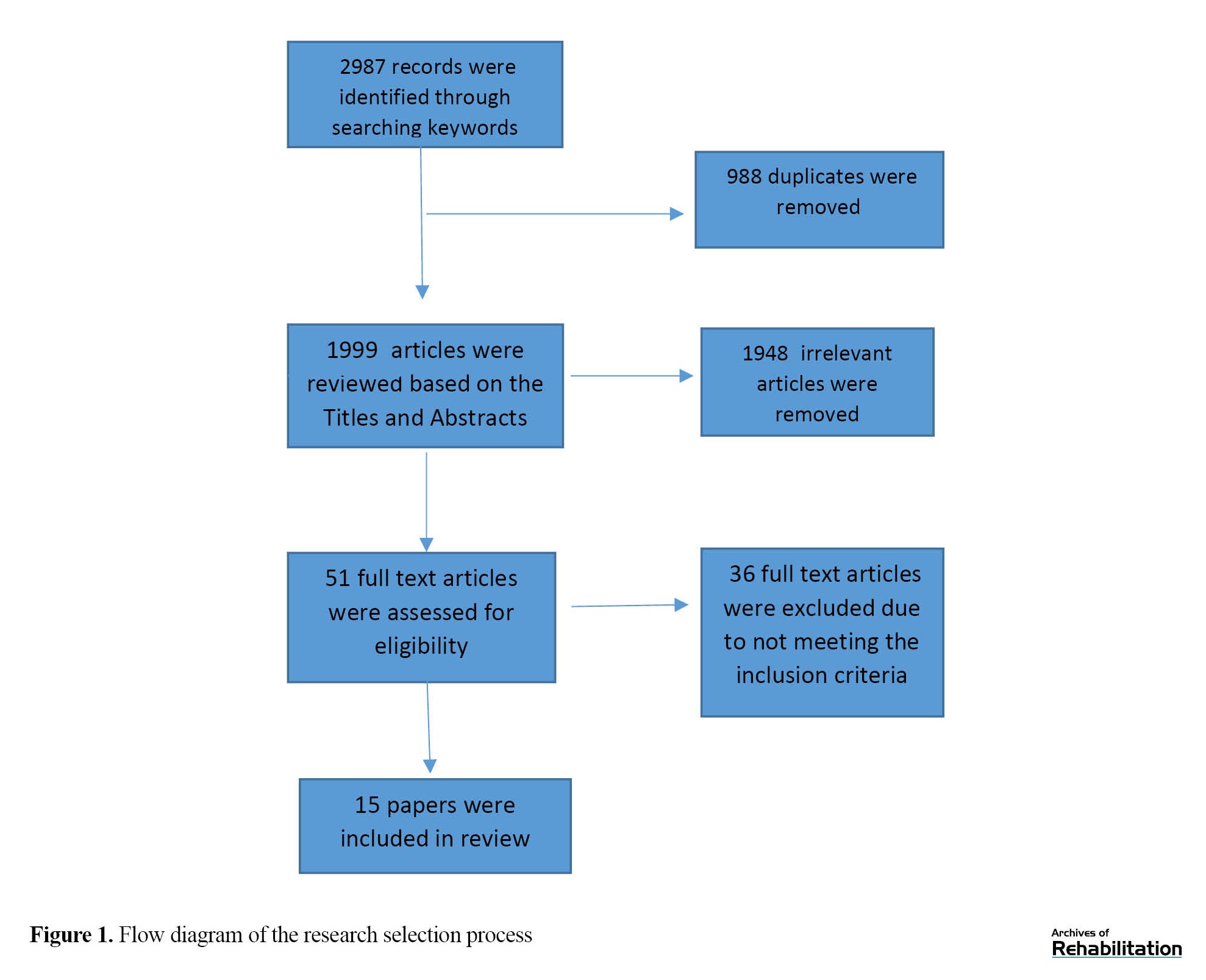

Data diagramming

In this step, the study process chart was set up along with the dropping of studies in each step and the reason for dropping.

Results

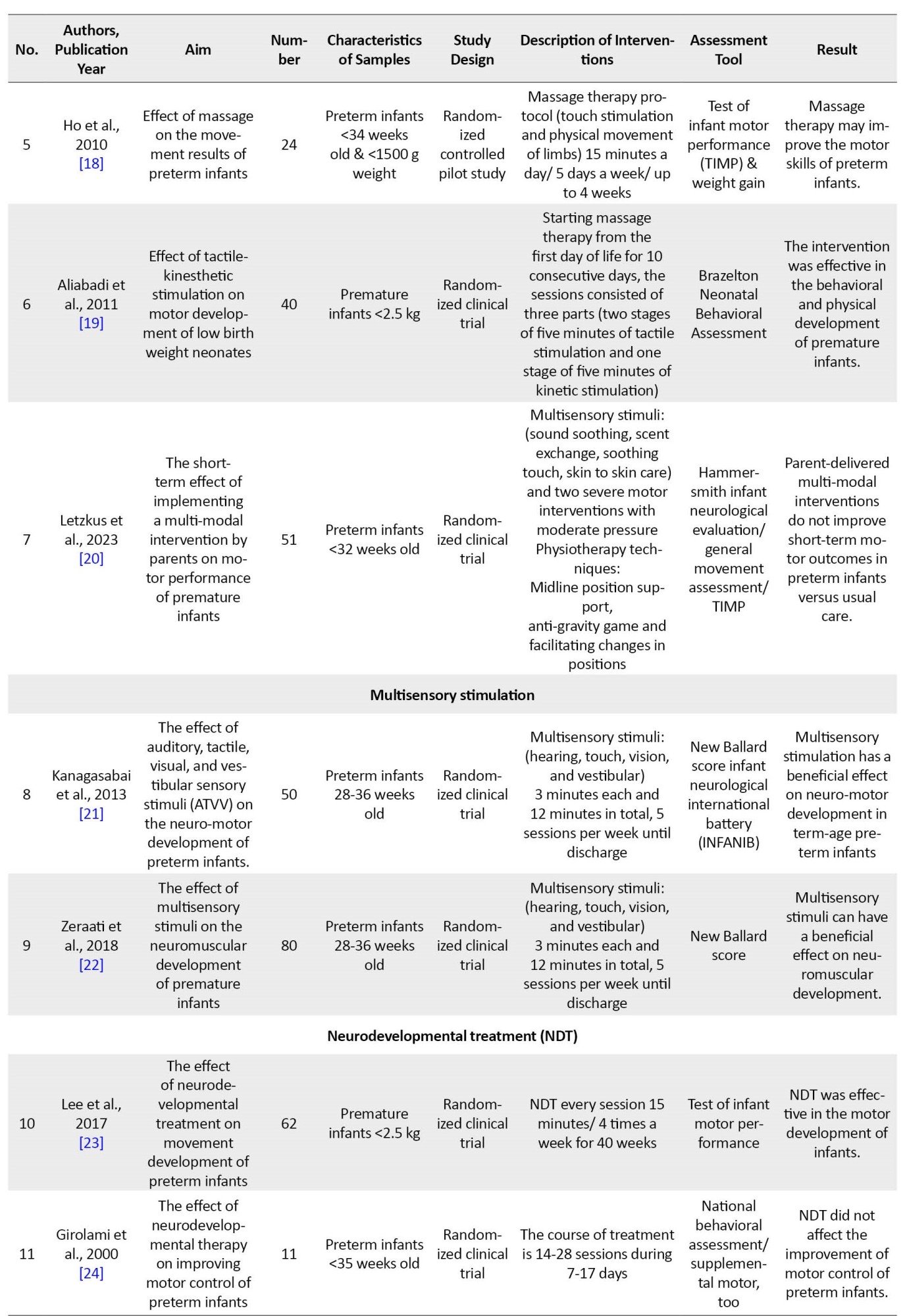

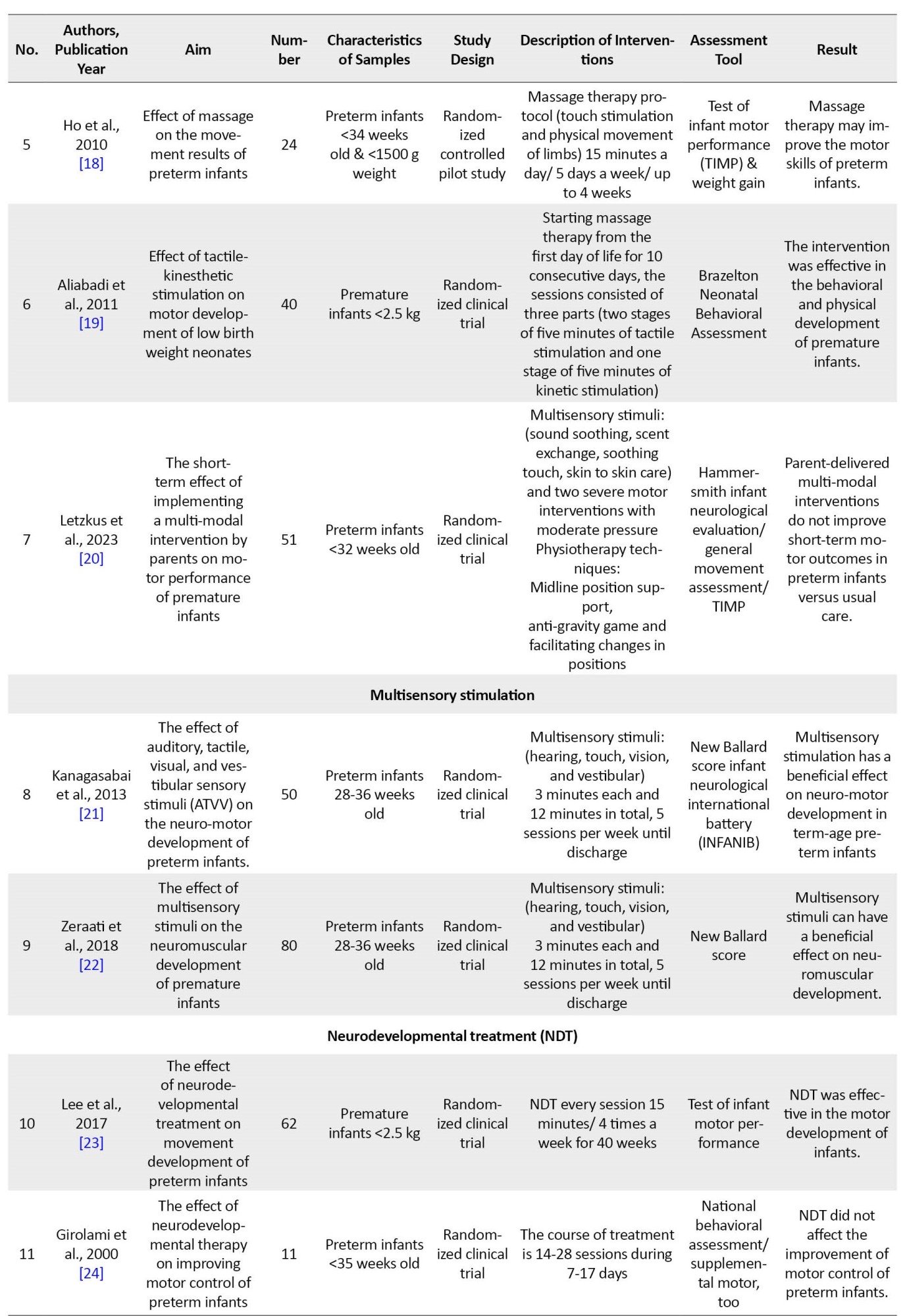

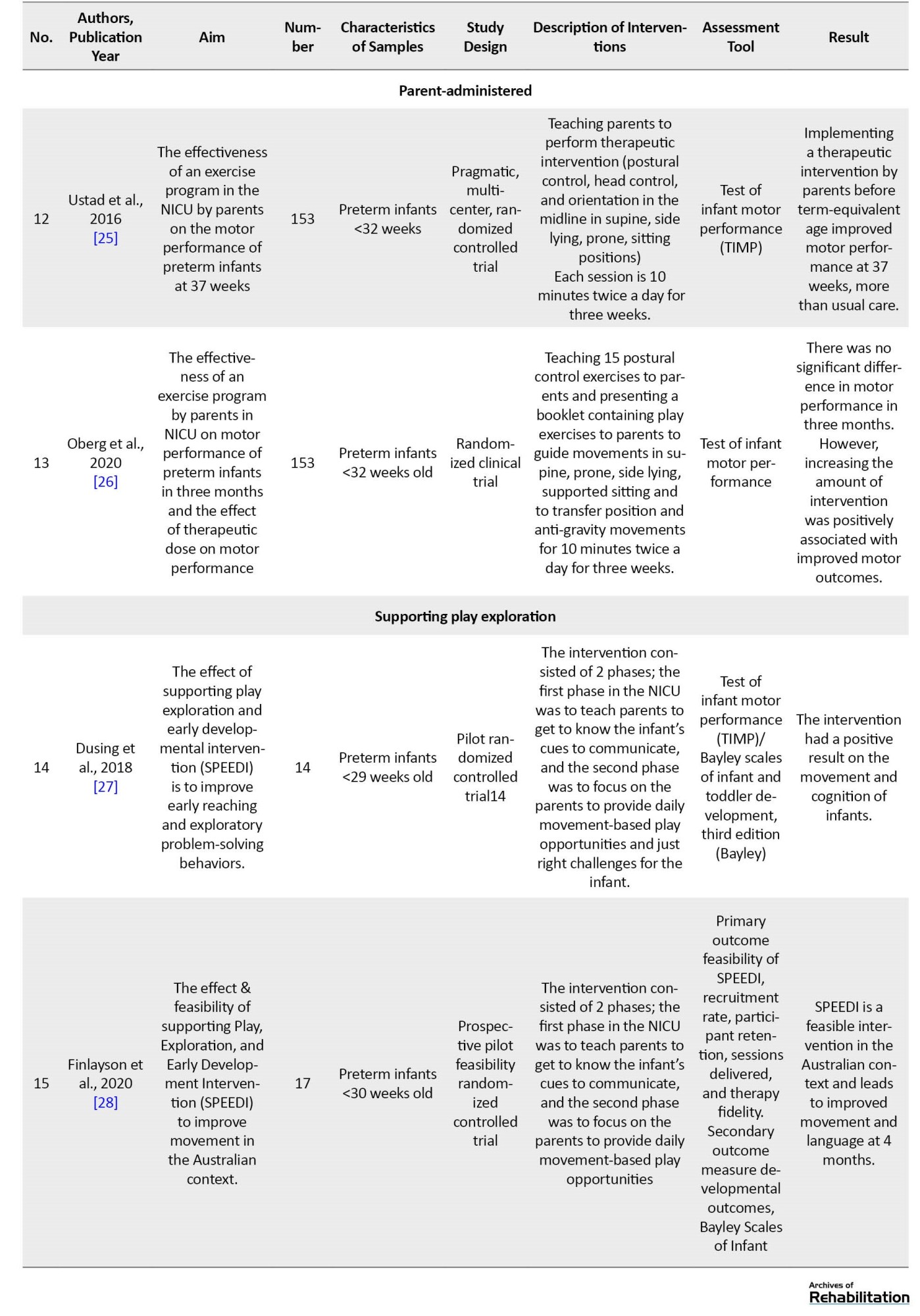

In the initial search, 2987 articles were identified. 988 duplicate articles were removed using Endnote software. The title and abstract of 1999 articles were reviewed for eligibility based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 948 articles were excluded due to their irrelevance. The full text of 51 articles was studied and finally 15 articles that met the inclusion criteria were examined (Figure 1). Neuro-motor rehabilitation studies of preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit differed based on the characteristics of the intervention and the way the outcome was measured. In general, based on the evidence in this scoping review, and during meetings with experts in this field, therapeutic interventions for motor skills of preterm infants were classified into four categories, which include: 1) Multi-sensory and multi-modal interventions, 2) Neuro-developmental interventions, 3) Parent-administered interventions, 4) Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention (Table 1).

Therefore, in the following, we provide a brief explanation about the studies.

Multi-sensory & multi-modal

9 studies are included in this classification. 7 studies included multimodal stimulation [14-20]. 2 studies include multi-sensory stimulation [21, 22]. The common feature of most of the studies in this category is the stimulation of hearing, touch, vision and vestibular senses. The stimulation method was such that for auditory stimulation, a soft lullaby between 30-40 dB was played for the infant using a miniature speaker. Tactile Stimulation, Gentle stroking massage in a sequence of chest, upper limbs and lower limbs in supine position; Visual Stimulation, Black and white visual stimulation card hung at a distance of 8–10 in. from the neonate; Vestibular Stimulation, Gentle horizontal and vertical rocking. In most of the multi-modal studies in this research, in addition to sensory stimuli in the same way as explained, movement has been used in this way; Guided movements of the upper and lower limbs, anti-gravity movements in the prone position (stretching the neck and spine), anti-gravity movements in the sitting position and vertical (supported) position. The time and amount of interventions were different. All these interventions were implemented in a short period of time in the intensive care unit and did not continue after discharge. The results of most studies indicate the short-term effect of therapeutic interventions on the neuromotor skills of infants. The details of therapeutic interventions are given in Table 1.

Neuro-developmental treatment

2 studies are included in this classification [23, 24].In these studies, neurodevelopmental therapy using manipulation techniques a key control points affects movement and the ability to maintain body posture. The method of implementing the NDT protocol; The infant was placed in supine, prone, side lying, and sitting positions, in the supine position: The infant was placed on the therapist's lap or on the isolated device, head in the midline, elongation of cervical spine, shoulders and arms on chest with scapular depression and elbow flexion, elongation of thoracic and lumbar spine, pelvis slightly off support surface. hips and knees flexed over abdomen. The goals of being in this position; ability to hold head upright and maintain in middle line, bringing hands together for reaching, assist bringing hands to mouth, life pelvis and flexed legs, rolling from supine to right and left side. in the prone position; The infant was placed on the therapist's lap or isolated device, positioned in flexion on either side of the infant's chin, pelvis tilted posteriorly with flexed hips and knees under abdomen. The goals of being in this position; ability to Lift head and turn right and left, ability to bring hands next to the mouth and shoulders, ability to stabilize the shoulders to lift and turn head, rolling from prone to the sides. in sitting position; The infant was placed sitting on the therapist's lap or bed, Head supported from behind with elongation of cervical spine, back straight, pelvis alignment natural, control over each shoulder to maintain depression and arms forward to midline, the infant should be tilted 10 to 15 degrees backward to space, hips and knees flexed in the neutral alignment, slight upward traction of the trunk to inhibit back rounding. The goals of being in this position; ability to hold head upright and maintain in midline, ability to maintain scapular depression and bring hands to midline, ability to maintain flexed hip and knees in neutral rotation. In the side lying position, the infant was placed on its side on the therapist's lap or the bed, head flexed slightly forward with capital flexion, arms forward to midline, elongation of thoracic and lumbar spine, neutral pelvis, hips and the knees flexed up toward abdomen. The goals of being in this position; ability to keep head flexed forward, the ability to bring arms forward-hands to the mouth, ability to maintain pelvis in a neutral alignment and hips and the knees flexed up toward abdomen. The duration of these interventions was 15 minutes twice a day and 4 days a week until discharge. Both of these interventions in the intensive care unit were not continued after discharge. In one study, the results indicated that the intervention was effective [23]. In another study, therapeutic intervention was not effective [24]. Details of therapeutic interventions are given in Table 1.

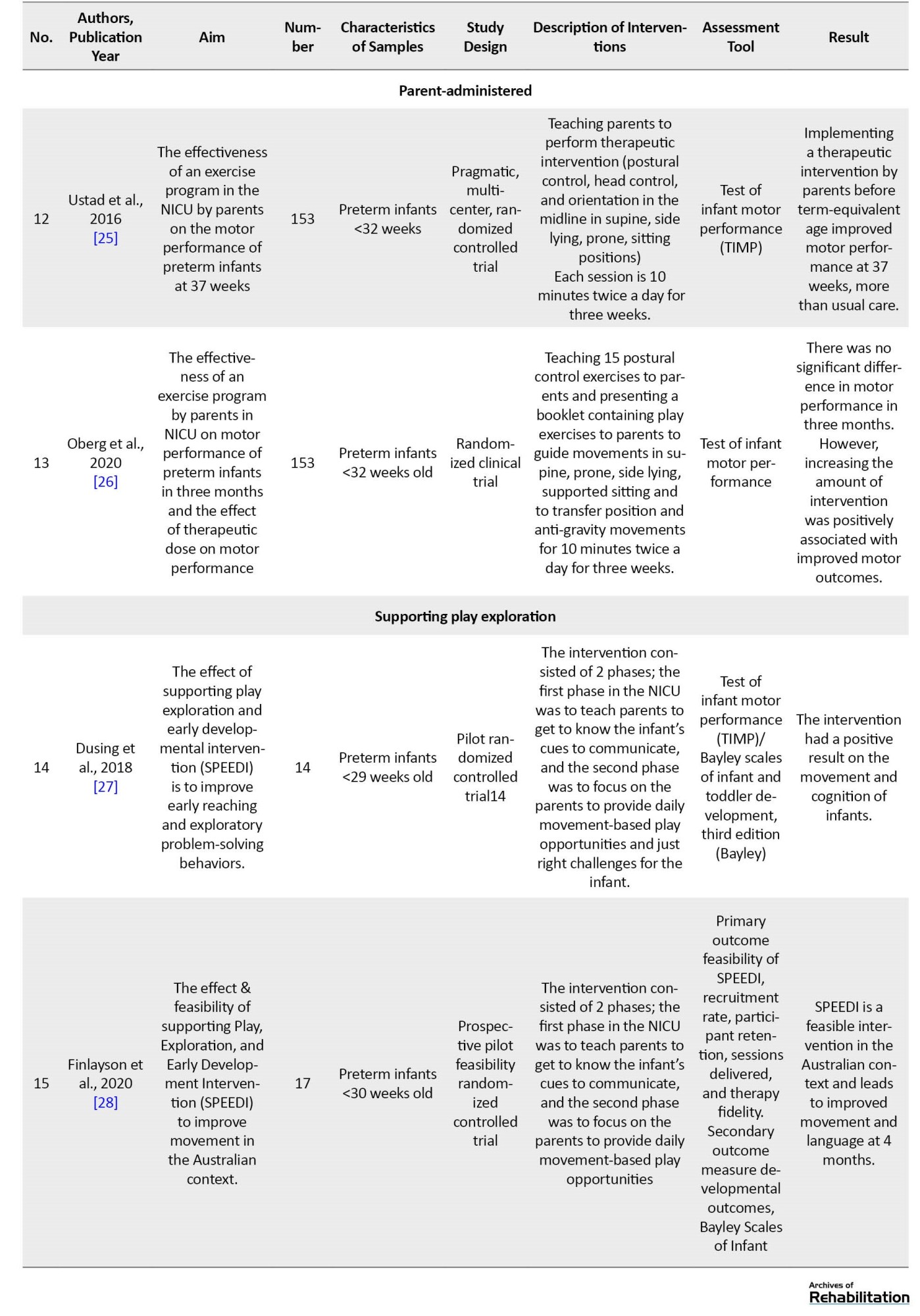

Parent-administered

2 studies are included in this classification [25, 26]. These two studies were designed based on mother-infant interaction program and family-centered practice. In these studies, the therapist met with the parents for 3 sessions to teach, revise and support parent learning. During session one, the therapist explained and demonstrated the play-exercises for the parent. During the second session, the parent performed the intervention under the supervision of the therapist. The therapist observed the parent’s performance of the exercises and provided input to enhance the delivery of each exercise in the protocol. One week later, therapist scheduled a third consultation to answer questions and clarify delivery of the protocol. Parents were invited to contact the therapist if they were in need of additional support or clarification regarding the exercise protocol. Per the protocol, the parent was asked to administer the intervention up to 10 minutes, twice a day, for 3 consecutive weeks beginning at 34 weeks and to terminate the exercise protocol at 37 weeks. These studies were also performed only while the infant was in the NICU and ended after discharge. In one study, the effect of the intervention was evaluated at 37 weeks and the results indicated that the therapeutic intervention was effective at 37 weeks [25]. In another study, the effect of therapeutic intervention was evaluated in a 3-month-old infant, and no significant difference was reported in the results of therapeutic intervention [26].

Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention (SPEEDI)

2 studies were included in this classification [27, 28]. The studies were based on action perception theory and synactive theory of development. These interventions were designed based on the enrichment of the environment and active participation of the infant for movement-based play and problem solving. The method of implementing interventions in these studies is two-phase (hospital and home). phase 1 was in NICU until discharge and included 5 sessions. All sessions were designed to include some time with the infant, discussion of behavioral cues and development, and answering the parents’ questions. Videos were provided for parents to review between sessions. The content of these videos was about the ideal times to interact, feed and play with the infant and how to prepare the infant for interaction. An activity booklet was reviewed with the parent during the last few visits in phase 1 in preparation for phase 2. phase 2 was at home. The focus of this phase was on parents to provide their infant with daily opportunities for motor and problem-solving based play with a goal of improving motor skills and early problem solving. The duration of the play was 20 minutes a day, 5 days a week, for 3 months, with the continuous support of a therapist. The intervention was focused on promoting motor control through a high amount of infant-directed exploratory behavior practice, and the instructions for playing with the infant at home were as follows; Play should be performed when infant is awake and alert but not crying. The home should be calm and the focus should be on fun plays for the infant. You can make this play time more fun for you and infant by talking or singing with your infant during the activities. Follow your baby’s cue and limit activities if your infant shows sign of stress or has trouble interacting, reduce activity and give infant a break. The activities used in the play included these items: 1) Encouraging the infant to look at people and toys that are within 10-12 inches of her and follow the movement of the toys with her eyes for 4 minutes; 2) Place the infant in a tummy position for 4 minutes and encourage the infant to lift its head, turn its head to the right and left to look at toys; 3) Holding head up for 4 minutes, in such a way that the infant is placed on the mother's shoulder and the mother supports the infant's back with her hand or supports the infant in a sitting position with her hands around her baby’s torso and arms so infant can practice lifting his/her head; 4) Kicking play for 4 minutes, in which the infant is placed in a supine position and t toys hang over infant’s feet so infant will accidentally bump them. Eventually this will help him/her learn to kick on purpose to hit the toys; 5) Toy play with hands and legs in the middle for 4 minutes, placing the rattle on the infant 's hands or feet, helping the infant to bring the hands to the mouth. in both studies, the results indicated that the interventions were effective on the motor skills of infants. In one study, the effect of intervention was follow at 6 months and 12 months and the results were significant [27]. The details of the interventions are given in Table 1.

Discussion

Evidence-based early interventions are needed to target the early motor abilities of preterm infants who are at risk for motor delay or cerebral palsy. Since the evidence about rehabilitation interventions in improving the neuromotor development of preterm infants was varied and scattered. Therefore, the present study was developed with the aim of identifying the types of therapeutic interventions for motor skills of preterm infants. In the present study, according to the evidence obtained and the opinions of experts in this field, interventions for the rehabilitation of motor skills of preterm infants hospitalized in the NICU were classified into four groups.

multimodal and multisensory interventions

Multi-sensory stimulation is relatively a new intervention closely related to principles of evolutionary care [21]. Since 1960, different researchers have proposed different types of multi-sensory stimulation for premature infants admitted in the hospital with aim to simulate the intrauterine environment at the first weeks of life in order to maintain and facilitate the development of preterm infants [29]. Based on the findings of the present study and the review study conducted by Pineda et al. (2018), there is growing evidence that supports the use of early sensory interventions in infants hospitalized in the NICU [30]. However, there are significant differences in sensory exposures, amount, and timing of sensory interventions across literature that make it challenging to combine studies for a cohesive understanding of appropriate sensory interventions. In addition, there are gaps in our understanding of appropriate timing of interventions. Also, there is little evidence to suggest there are improved long-term outcomes related to sensory interventions. Of course, the lack of evidence does not mean that these interventions do not improve long-term results. Most of the sensory interventions were done for short periods of time over only a few days, it remains unclear what the potential is for improving outcomes if such sensory exposures occurred consistently throughout NICU hospitalization [30].

Neuro developmental treatment

Based on the findings of the current research, neurodevelopmental therapy or NDT techniques are included in the treatment of motor skills of preterm infants. These techniques are usually the basis of many methods used by therapists to facilitate antigravity movements [31]. Although NDT techniques (such as positioning and anti-gravity movements) are used in the NICU and are included in the therapeutic repertoire of many therapists, they lack the support provided by statistically significant and measurable long-term results from randomized clinical trials [32, 33].

Parent-administered

some intervention that focus primarily on parent-infant relationships, but do not have a primary focus on early motor development, have been shown to improved mother-infant interactions, but not developmental outcomes [34-36]. Ustad and Oberg's studies are among the studies that have investigated the effect of interventions implemented by parents on motor development. These studies were conducted for 10 minutes twice a day for three weeks in the NICU. The TIMP tool was evaluated and the results indicated that the intervention was effective on the motor development of infants [25]. While Oberg examined the results of the study at three months and did not observe a significant difference in the results, it is stated that the increase in the amount of intervention was positively related to the improvement of the motor result [26].

Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention (SPEEDI)

Recent rehabilitation research on the treatment of children with motor impairments has emphasized the need for task specific and self-initiated movements to enhance learning [37, 38]. Parents of infants in the SPEEDI group were encouraged to identify ideal times to interact, set up the environment to provide a “just right challenge”, and support their infants self-initiated movements through a variety of activities. SPEEDI is an intervention that starts in the NICU and continues for three months after discharge, and by empowering parents to implement daily programs of movement opportunities and environmental enrichment, it examines the potential of increasing growth, even after the end of the intervention. Studies in this field are pilot and feasibility, so there is a need for more research.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this research and the meetings held with experts in this field, we were able to divide the early rehabilitation interventions of motor skills of preterm infants into 4 groups: 1) Multimodal and multisensory interventions, 2) Neurodevelopmental interventions, 3) Parent-administered interventions, 4) Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention. In this way, all types of therapeutic interventions in improving motor skills of infants were identified. Most of the studies involved short-term interventions and reported short-term effects on motor improvement. Only the supportive play exploration and early developmental intervention continued after discharge and bridged the gap of early NICU-to-home interventions and reported improved motor development in the short- and long-term (6, 12 months).

Suggestions

Based on the current evidence identified in this review and the opinions of clinical experts and the values of patients and parents, it is suggested to design a program for the development of motor skills of preterm infants, which includes the training and support of caregivers, the use of environmental enrichment strategies, movements initiated by the infant and facilitate and support the transition from hospital to home.

Limitation

This review only includes studies in English and Persian. It also does not include non- published literature.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a review with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Design, implementation, and writing of all parts of the research: All the authors; Research and review and draft writing: Hajar Sabour Eghbali Mustafa Khan; Methodology, editing, and finalization of the writing: Nazila AkbarFahimi; Project supervision and management: Seyed Ali Hosseini.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We hereby express our gratitude to Farin Soleimani and Aida Ravarian who helped us in conducting this research.

References

According to the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO), infants who are born before 37 weeks of pregnancy are called premature or preterm, and based on the gestational age, they are divided into three subgroups: Extreme preterm (under 28 weeks), very preterm (28-32 weeks) and moderate to late preterm (32-37) are classified [1].

Platt et al. (2014) highlighted that preterm birth is a common issue worldwide, with an estimated 10% of all of births being preterm. Preterm infants are more prone to face short-term and long-term neurodevelopmental disorders due to intrauterine growth interruption and hospitalization in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) [2]. In fact, a recent study showed that more than 25% of neonates born between 28 and 32 weeks of gestation have developmental disorders at the age of 2 years old, and this ratio reaches 40% at the age of 10 [3]. but even infants who are free of major neurodevelopmental delays are still at a higher risk of poor motor outcomes, such as subtle deficits in eye-hand coordination, sensory-motor integration, manual dexterity, and gross motor skills [4]. If these difficulties persist, integration and performance at school can be affected, leading to lower self-esteem [5].

The human brain in infancy is highly plastic and there is an active growth of dendrites and formation of synapses. Experience influences and models the brain and leads to structural changes in, e.g. the number of synapses that are developed, the synapses’ position and functioning, as well as elimination of synapses that are not needed [6]. Motor skills may be highly influenced by early intervention because the motor pathways forming the corticospinal tracts already show mature myelin at term age and myelination may be activity-dependent [7].There is some evidence that recovery from central nervous system injury in infants can be understood both by new growth of motor neurons and creation of new synapses [8]. Of these insights about brain plasticity it is suggested that early-targeted customized individual intervention could be of great importance to the development of movement quality and function of preterm children.

Evidence-based, effective early intervention programs are needed to target early motor abilities that support motor and cognitive development in infants at high risk of having cerebral palsy or minor neurological dysfunctions. Motor and cognitive development are tightly coupled, suggesting that delays in one domain could contribute to delays in other domains [9]. Motor experience provides infants an opportunity to learn about objects and interaction supports development in multiple domains [10]. Motor activity contributes to the infants attempts to attend to the environment, allowing the infant to receive and interpret important information, and solve problems by linking the mind and body in a cycle that supports development [11].

A recent Cochrane review of early developmental intervention programs to prevent motor and cognitive impairment highlighted the impact that even a minor motor impairment can have on a child and concluded that effective activities to enhance the motor skills of preterm infants need to be identified [12].

Since the evidence about rehabilitation interventions in improving the motor development of preterm infants is diverse and scattered and there is heterogeneity in the amount, time and type of therapeutic interventions, the purpose of this study is to summarize and identify the types of rehabilitation interventions (occupational therapy and physiotherapy) with the aim Improving the motor skills of infants admitted to the intensive care unit. In this way, the course of research in this field has become clear, therapeutic interventions that need more research and study are identified, and suggestions for future studies are presented.

Materials and Methods

The Scoping Review method is a structured method to obtain useful background information and find gaps in the literature. In the current study, this method was used, which was presented by Arksey et al. in 5 steps [13] and includes the following:

Identifying of the research question

The questions of the present research were: How many occupational therapy and physiotherapy intervention studies have been related to the motor development of preterm infants? What kind of treatment approaches have been used in these studies?

Identifying relevant studies

In this study, PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science and Google Scholar search engine databases were used to collect information with an advanced search strategy.

Sample syntax in PubMed

A) Preterm infants[Title/Abstract] OR premature infants[Title/Abstract] OR neonates

B) Occupational therapy[Title/Abstract] OR physiotherapy [Title/Abstract] OR early intervention OR sensory stimulation[Title/Abstract] OR play [Title]

C) A AND B

Study selection

The inclusion criteria included articles that were published in English and Farsi, were the main subject of occupational therapy and physiotherapy studies on motor skills of preterm infants, and were published between 2000 and 2023. The exclusion criteria were review studies and studies other than clinical trials.

Steps for selecting studies

After entering keywords and searching, duplicate articles were removed using endnote software, and then studies whose titles did not match the inclusion criteria were removed. In the remaining studies, the review abstract and a number of studies were excluded due to non-compliance with the inclusion criteria. After that, the remaining articles were examined in full text in detail, and at the end, studies that did not present an intervention or did not provide a proper description of the implementation of the interventions were excluded. All steps were done separately by two independent researchers. The results of each stage were discussed by two researchers, and in cases of disagreement, decisions were made with the agreement of both.

Data diagramming

In this step, the study process chart was set up along with the dropping of studies in each step and the reason for dropping.

Results

In the initial search, 2987 articles were identified. 988 duplicate articles were removed using Endnote software. The title and abstract of 1999 articles were reviewed for eligibility based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, and 948 articles were excluded due to their irrelevance. The full text of 51 articles was studied and finally 15 articles that met the inclusion criteria were examined (Figure 1). Neuro-motor rehabilitation studies of preterm infants in the neonatal intensive care unit differed based on the characteristics of the intervention and the way the outcome was measured. In general, based on the evidence in this scoping review, and during meetings with experts in this field, therapeutic interventions for motor skills of preterm infants were classified into four categories, which include: 1) Multi-sensory and multi-modal interventions, 2) Neuro-developmental interventions, 3) Parent-administered interventions, 4) Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention (Table 1).

Therefore, in the following, we provide a brief explanation about the studies.

Multi-sensory & multi-modal

9 studies are included in this classification. 7 studies included multimodal stimulation [14-20]. 2 studies include multi-sensory stimulation [21, 22]. The common feature of most of the studies in this category is the stimulation of hearing, touch, vision and vestibular senses. The stimulation method was such that for auditory stimulation, a soft lullaby between 30-40 dB was played for the infant using a miniature speaker. Tactile Stimulation, Gentle stroking massage in a sequence of chest, upper limbs and lower limbs in supine position; Visual Stimulation, Black and white visual stimulation card hung at a distance of 8–10 in. from the neonate; Vestibular Stimulation, Gentle horizontal and vertical rocking. In most of the multi-modal studies in this research, in addition to sensory stimuli in the same way as explained, movement has been used in this way; Guided movements of the upper and lower limbs, anti-gravity movements in the prone position (stretching the neck and spine), anti-gravity movements in the sitting position and vertical (supported) position. The time and amount of interventions were different. All these interventions were implemented in a short period of time in the intensive care unit and did not continue after discharge. The results of most studies indicate the short-term effect of therapeutic interventions on the neuromotor skills of infants. The details of therapeutic interventions are given in Table 1.

Neuro-developmental treatment

2 studies are included in this classification [23, 24].In these studies, neurodevelopmental therapy using manipulation techniques a key control points affects movement and the ability to maintain body posture. The method of implementing the NDT protocol; The infant was placed in supine, prone, side lying, and sitting positions, in the supine position: The infant was placed on the therapist's lap or on the isolated device, head in the midline, elongation of cervical spine, shoulders and arms on chest with scapular depression and elbow flexion, elongation of thoracic and lumbar spine, pelvis slightly off support surface. hips and knees flexed over abdomen. The goals of being in this position; ability to hold head upright and maintain in middle line, bringing hands together for reaching, assist bringing hands to mouth, life pelvis and flexed legs, rolling from supine to right and left side. in the prone position; The infant was placed on the therapist's lap or isolated device, positioned in flexion on either side of the infant's chin, pelvis tilted posteriorly with flexed hips and knees under abdomen. The goals of being in this position; ability to Lift head and turn right and left, ability to bring hands next to the mouth and shoulders, ability to stabilize the shoulders to lift and turn head, rolling from prone to the sides. in sitting position; The infant was placed sitting on the therapist's lap or bed, Head supported from behind with elongation of cervical spine, back straight, pelvis alignment natural, control over each shoulder to maintain depression and arms forward to midline, the infant should be tilted 10 to 15 degrees backward to space, hips and knees flexed in the neutral alignment, slight upward traction of the trunk to inhibit back rounding. The goals of being in this position; ability to hold head upright and maintain in midline, ability to maintain scapular depression and bring hands to midline, ability to maintain flexed hip and knees in neutral rotation. In the side lying position, the infant was placed on its side on the therapist's lap or the bed, head flexed slightly forward with capital flexion, arms forward to midline, elongation of thoracic and lumbar spine, neutral pelvis, hips and the knees flexed up toward abdomen. The goals of being in this position; ability to keep head flexed forward, the ability to bring arms forward-hands to the mouth, ability to maintain pelvis in a neutral alignment and hips and the knees flexed up toward abdomen. The duration of these interventions was 15 minutes twice a day and 4 days a week until discharge. Both of these interventions in the intensive care unit were not continued after discharge. In one study, the results indicated that the intervention was effective [23]. In another study, therapeutic intervention was not effective [24]. Details of therapeutic interventions are given in Table 1.

Parent-administered

2 studies are included in this classification [25, 26]. These two studies were designed based on mother-infant interaction program and family-centered practice. In these studies, the therapist met with the parents for 3 sessions to teach, revise and support parent learning. During session one, the therapist explained and demonstrated the play-exercises for the parent. During the second session, the parent performed the intervention under the supervision of the therapist. The therapist observed the parent’s performance of the exercises and provided input to enhance the delivery of each exercise in the protocol. One week later, therapist scheduled a third consultation to answer questions and clarify delivery of the protocol. Parents were invited to contact the therapist if they were in need of additional support or clarification regarding the exercise protocol. Per the protocol, the parent was asked to administer the intervention up to 10 minutes, twice a day, for 3 consecutive weeks beginning at 34 weeks and to terminate the exercise protocol at 37 weeks. These studies were also performed only while the infant was in the NICU and ended after discharge. In one study, the effect of the intervention was evaluated at 37 weeks and the results indicated that the therapeutic intervention was effective at 37 weeks [25]. In another study, the effect of therapeutic intervention was evaluated in a 3-month-old infant, and no significant difference was reported in the results of therapeutic intervention [26].

Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention (SPEEDI)

2 studies were included in this classification [27, 28]. The studies were based on action perception theory and synactive theory of development. These interventions were designed based on the enrichment of the environment and active participation of the infant for movement-based play and problem solving. The method of implementing interventions in these studies is two-phase (hospital and home). phase 1 was in NICU until discharge and included 5 sessions. All sessions were designed to include some time with the infant, discussion of behavioral cues and development, and answering the parents’ questions. Videos were provided for parents to review between sessions. The content of these videos was about the ideal times to interact, feed and play with the infant and how to prepare the infant for interaction. An activity booklet was reviewed with the parent during the last few visits in phase 1 in preparation for phase 2. phase 2 was at home. The focus of this phase was on parents to provide their infant with daily opportunities for motor and problem-solving based play with a goal of improving motor skills and early problem solving. The duration of the play was 20 minutes a day, 5 days a week, for 3 months, with the continuous support of a therapist. The intervention was focused on promoting motor control through a high amount of infant-directed exploratory behavior practice, and the instructions for playing with the infant at home were as follows; Play should be performed when infant is awake and alert but not crying. The home should be calm and the focus should be on fun plays for the infant. You can make this play time more fun for you and infant by talking or singing with your infant during the activities. Follow your baby’s cue and limit activities if your infant shows sign of stress or has trouble interacting, reduce activity and give infant a break. The activities used in the play included these items: 1) Encouraging the infant to look at people and toys that are within 10-12 inches of her and follow the movement of the toys with her eyes for 4 minutes; 2) Place the infant in a tummy position for 4 minutes and encourage the infant to lift its head, turn its head to the right and left to look at toys; 3) Holding head up for 4 minutes, in such a way that the infant is placed on the mother's shoulder and the mother supports the infant's back with her hand or supports the infant in a sitting position with her hands around her baby’s torso and arms so infant can practice lifting his/her head; 4) Kicking play for 4 minutes, in which the infant is placed in a supine position and t toys hang over infant’s feet so infant will accidentally bump them. Eventually this will help him/her learn to kick on purpose to hit the toys; 5) Toy play with hands and legs in the middle for 4 minutes, placing the rattle on the infant 's hands or feet, helping the infant to bring the hands to the mouth. in both studies, the results indicated that the interventions were effective on the motor skills of infants. In one study, the effect of intervention was follow at 6 months and 12 months and the results were significant [27]. The details of the interventions are given in Table 1.

Discussion

Evidence-based early interventions are needed to target the early motor abilities of preterm infants who are at risk for motor delay or cerebral palsy. Since the evidence about rehabilitation interventions in improving the neuromotor development of preterm infants was varied and scattered. Therefore, the present study was developed with the aim of identifying the types of therapeutic interventions for motor skills of preterm infants. In the present study, according to the evidence obtained and the opinions of experts in this field, interventions for the rehabilitation of motor skills of preterm infants hospitalized in the NICU were classified into four groups.

multimodal and multisensory interventions

Multi-sensory stimulation is relatively a new intervention closely related to principles of evolutionary care [21]. Since 1960, different researchers have proposed different types of multi-sensory stimulation for premature infants admitted in the hospital with aim to simulate the intrauterine environment at the first weeks of life in order to maintain and facilitate the development of preterm infants [29]. Based on the findings of the present study and the review study conducted by Pineda et al. (2018), there is growing evidence that supports the use of early sensory interventions in infants hospitalized in the NICU [30]. However, there are significant differences in sensory exposures, amount, and timing of sensory interventions across literature that make it challenging to combine studies for a cohesive understanding of appropriate sensory interventions. In addition, there are gaps in our understanding of appropriate timing of interventions. Also, there is little evidence to suggest there are improved long-term outcomes related to sensory interventions. Of course, the lack of evidence does not mean that these interventions do not improve long-term results. Most of the sensory interventions were done for short periods of time over only a few days, it remains unclear what the potential is for improving outcomes if such sensory exposures occurred consistently throughout NICU hospitalization [30].

Neuro developmental treatment

Based on the findings of the current research, neurodevelopmental therapy or NDT techniques are included in the treatment of motor skills of preterm infants. These techniques are usually the basis of many methods used by therapists to facilitate antigravity movements [31]. Although NDT techniques (such as positioning and anti-gravity movements) are used in the NICU and are included in the therapeutic repertoire of many therapists, they lack the support provided by statistically significant and measurable long-term results from randomized clinical trials [32, 33].

Parent-administered

some intervention that focus primarily on parent-infant relationships, but do not have a primary focus on early motor development, have been shown to improved mother-infant interactions, but not developmental outcomes [34-36]. Ustad and Oberg's studies are among the studies that have investigated the effect of interventions implemented by parents on motor development. These studies were conducted for 10 minutes twice a day for three weeks in the NICU. The TIMP tool was evaluated and the results indicated that the intervention was effective on the motor development of infants [25]. While Oberg examined the results of the study at three months and did not observe a significant difference in the results, it is stated that the increase in the amount of intervention was positively related to the improvement of the motor result [26].

Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention (SPEEDI)

Recent rehabilitation research on the treatment of children with motor impairments has emphasized the need for task specific and self-initiated movements to enhance learning [37, 38]. Parents of infants in the SPEEDI group were encouraged to identify ideal times to interact, set up the environment to provide a “just right challenge”, and support their infants self-initiated movements through a variety of activities. SPEEDI is an intervention that starts in the NICU and continues for three months after discharge, and by empowering parents to implement daily programs of movement opportunities and environmental enrichment, it examines the potential of increasing growth, even after the end of the intervention. Studies in this field are pilot and feasibility, so there is a need for more research.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this research and the meetings held with experts in this field, we were able to divide the early rehabilitation interventions of motor skills of preterm infants into 4 groups: 1) Multimodal and multisensory interventions, 2) Neurodevelopmental interventions, 3) Parent-administered interventions, 4) Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention. In this way, all types of therapeutic interventions in improving motor skills of infants were identified. Most of the studies involved short-term interventions and reported short-term effects on motor improvement. Only the supportive play exploration and early developmental intervention continued after discharge and bridged the gap of early NICU-to-home interventions and reported improved motor development in the short- and long-term (6, 12 months).

Suggestions

Based on the current evidence identified in this review and the opinions of clinical experts and the values of patients and parents, it is suggested to design a program for the development of motor skills of preterm infants, which includes the training and support of caregivers, the use of environmental enrichment strategies, movements initiated by the infant and facilitate and support the transition from hospital to home.

Limitation

This review only includes studies in English and Persian. It also does not include non- published literature.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This article is a review with no human or animal sample.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Design, implementation, and writing of all parts of the research: All the authors; Research and review and draft writing: Hajar Sabour Eghbali Mustafa Khan; Methodology, editing, and finalization of the writing: Nazila AkbarFahimi; Project supervision and management: Seyed Ali Hosseini.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We hereby express our gratitude to Farin Soleimani and Aida Ravarian who helped us in conducting this research.

References

- Blencowe H, Cousens S, Oestergaard MZ, Chou D, Moller AB, Narwal R, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of preterm birth rates in the year 2010 with time trends since 1990 for selected countries: A systematic analysis and implications. The Lancet. 2012; 379(9832):2162-72. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60820-4] [PMID]

- Platt MJ. Outcomes in preterm infants. Public Health. 2014; 128(5):399-403. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2014.03.010] [PMID]

- Johnston KM, Gooch K, Korol E, Vo P, Eyawo O, Bradt P, et al. The economic burden of prematurity in Canada. BMC Pediatrics. 2014; 14:93. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2431-14-93] [PMID]

- Arnaud C, Daubisse-Marliac L, White-Koning M, Pierrat V, Larroque B, Grandjean H, et al. Prevalence and associated factors of minor neuromotor dysfunctions at age 5 years in prematurely born children: The EPIPAGE Study. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2007; 161(11):1053-61. [DOI:10.1001/archpedi.161.11.1053] [PMID]

- Van Hus JW, Potharst ES, Jeukens-Visser M, Kok JH, Van Wassenaer-Leemhuis AG. Motor impairment in very preterm-born children: links with other developmental deficits at 5 years of age. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2014; 56(6):587-94. [DOI:10.1111/dmcn.12295] [PMID]

- Brodal P. The central nervous system: Structure and function. Oxford: Oxford university Press; 2004. [Link]

- Fields RD. Volume transmission in activity-dependent regulation of myelinating glia. Neurochemistry International. 2004; 45(4):503-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.neuint.2003.11.015] [PMID]

- Kinney HC, Brody BA, Kloman AS, Gilles FH. Sequence of central nervous system myelination in human infancy: II. Patterns of myelination in autopsied infants. Journal of Neuropathology & Experimental Neurology. 1988; 47(3):217-34. [DOI:10.1097/00005072-198805000-00003] [PMID]

- Lobo MA, Harbourne RT, Dusing SC, McCoy SW. Grounding early intervention: physical therapy cannot just be about motor skills anymore. Physical Therapy. 2013; 93(1):94-103. [DOI:10.2522/ptj.20120158] [PMID]

- Soska KC, Adolph KE, Johnson SP. Systems in development: Motor skill acquisition facilitates three-dimensional object completion. Developmental Psychology. 2010; 46(1):129-38. [DOI:10.1037/a0014618] [PMID]

- Gibson EJ. Exploratory behavior in the development of perceiving, acting, and the acquiring of knowledge. Annual Review of Psychology. 1988; 39(1):1-41. [DOI:10.1146/annurev.ps.39.020188.000245]

- Spittle A, Orton J, Anderson PJ, Boyd R, Doyle LW. Early developmental intervention programmes provided post hospital discharge to prevent motor and cognitive impairment in preterm infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; 2015(11):CD005495. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD005495.pub4] [PMID]

- Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2005; 8(1):19-32. [Link]

- Aranha VP. Multi modal stimulations to modify the neuromotor responses of hospitalized preterm infants [PhD dissertation]. Haryana: Maharishi Markandeshwar; 2019. [Link]

- Ponni HK, Rajarajeswari A, Sivakumar R. Effectiveness of Multimodal Sensory Stimulation in Improving Motor Outcomes of Preterm Infants. Indian Journal of Public Health. 2019; 10(8):467. [Link]

- Pineda R, Wallendorf M, Smith J. A pilot study demonstrating the impact of the supporting and enhancing NICU sensory experiences (SENSE) program on the mother and infant. Early Human Development. 2020; 144:105000. [DOI:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105000] [PMID]

- Fucile S, Gisel EG. Sensorimotor interventions improve growth and motor function in preterm infants. Neonatal Network. 2010; 29(6):359-66. [DOI:10.1891/0730-0832.29.6.359] [PMID]

- Ho YB, Lee RS, Chow CB, Pang MY. Impact of massage therapy on motor outcomes in very low-birthweight infants: Randomized controlled pilot study. Pediatrics International. 2010; 52(3):378-85. [DOI:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2009.02964.x] [PMID]

- Askary KR, Aliabadi F. [Effect of tactile-kinesthetic stimulation on motor development of low birth weight neonates. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2011. [Link]

- Letzkus L, Conaway MR, Daugherty R, Hook M, Zanelli S. A randomized-controlled trial of parent-administered interventions to improve short-term motor outcomes in hospitalized very low birthweight infants. 2023. [DOI:10.2139/ssrn.4385144]

- Kanagasabai PS, Mohan D, Lewis LE, Kamath A, Rao BK. Effect of multisensory stimulation on neuromotor development in preterm infants. The Indian Journal of Pediatrics. 2013; 80(6):460-4. [DOI:10.1007/s12098-012-0945-z] [PMID]

- Zeraati H, Nasimi F, Rezaeian A, Shahinfar J, Ghorban Zade M. Effect of multi-sensory stimulation on neuromuscular development of premature infants: A randomized clinical trial. Iranian Journal of Child Neurology. 2018; 12(3):32-9. [PMID]

- Lee EJ. Effect of Neuro-Development Treatment on motor development in preterm infants. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2017; 29(6):1095-7. [DOI:10.1589/jpts.29.1095] [PMID]

- Girolami GL, Campbell SK. Efficacy of a neuro-developmental treatment program to improve motor control in infants born prematurely. Pediatric Physical Therapy. 2000; 6(4):175-84. [DOI:10.1097/00001577-199406040-00002]

- Ustad T, Evensen KA, Campbell SK, Girolami GL, Helbostad J, Jørgensen L, et al. Early parent-administered physical therapy for preterm infants: A randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2016; 138(2):e20160271. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2016-0271] [PMID]

- Øberg GK, Girolami GL, Campbell SK, Ustad T, Heuch I, Jacobsen BK, et al. Effects of a parent-administered exercise program in the neonatal intensive care unit: Dose does matter-a randomized controlled trial. Physical Therapy. 2020; 100(5):860-9. [DOI:10.1093/ptj/pzaa014] [PMID]

- Dusing SC, Tripathi T, Marcinowski EC, Thacker LR, Brown LF, Hendricks-Muñoz KD. Supporting play exploration and early developmental intervention versus usual care to enhance development outcomes during the transition from the neonatal intensive care unit to home: A pilot randomized controlled trial. BMC Pediatrics. 2018; 18(1):46. [DOI:10.1186/s12887-018-1011-4] [PMID]

- Finlayson F, Olsen J, Dusing SC, Guzzetta A, Eeles A, Spittle A. Supporting play, exploration, and early development intervention (SPEEDI) for preterm infants: A feasibility randomised controlled trial in an Australian context. Early Human Development. 2020; 151:105172. [DOI:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105172] [PMID]

- VandenBerg KA. Individualized developmental care for high risk newborns in the NICU: A practice guideline. Early Human Development. 2007; 83(7):433-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.03.008] [PMID]

- Pineda R, Guth R, Herring A, Reynolds L, Oberle S, Smith J. Enhancing sensory experiences for very preterm infants in the NICU: An integrative review. Journal of Perinatology. 2017; 37(4):323-32. [DOI:10.1038/jp.2016.179] [PMID]

- Brown GT, Burns SA. The efficacy of neurodevelopmental treatment in paediatrics: A systematic review. British Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2001; 64(5):235-44. [DOI:10.1177/030802260106400505]

- Morgan C, Darrah J, Gordon AM, Harbourne R, Spittle A, Johnson R, et al. Effectiveness of motor interventions in infants with cerebral palsy: A systematic review. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2016; 58(9):900-9. [DOI:10.1111/dmcn.13105] [PMID]

- Novak I, Mcintyre S, Morgan C, Campbell L, Dark L, Morton N, et al. A systematic review of interventions for children with cerebral palsy: State of the evidence. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2013; 55(10):885-910. [DOI:10.1111/dmcn.12246] [PMID]

- Newnham CA, Milgrom J, Skouteris H. Effectiveness of a modified mother-infant transaction program on outcomes for preterm infants from 3 to 24 months of age. Infant Behavior and Development. 2009; 32(1):17-26. [DOI:10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.09.004] [PMID]

- Kynø NM, Ravn IH, Lindemann R, Fagerland MW, Smeby NA, Torgersen AM. Effect of an early intervention programme on development of moderate and late preterm infants at 36 months: A randomized controlled study. Infant Behavior and Development. 2012; 35(4):916-26. [DOI:10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.09.004] [PMID]

- Nurcombe B, Howell DC, Rauh VA, Teti DM, Ruoff P, Brennan J. An intervention program for mothers of low-birthweight infants: Preliminary results. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1984; 23(3):319-25. [DOI:10.1016/S0002-7138(09)60511-2] [PMID]

- Morgan C, Novak I, Badawi N. Enriched environments and motor outcomes in cerebral palsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2013; 132(3):e735-46. [DOI:10.1542/peds.2012-3985] [PMID]

Type of Study: Systematic Review |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 29/08/2023 | Accepted: 12/12/2023 | Published: 1/04/2024

Received: 29/08/2023 | Accepted: 12/12/2023 | Published: 1/04/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |