Volume 25, Issue 2 (Summer 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(2): 266-291 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Norozpour M, Pourshahbaz A, Poursharifi H, Dolatshahi B, Habibi N. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-adolescent-restructured Form (MMPI-A-RF): Characteristics of Conduct Disorder. jrehab 2024; 25 (2) :266-291

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3329-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3329-en.html

Marzieh Norozpour1

, Abbas Pourshahbaz2

, Abbas Pourshahbaz2

, Hamid Poursharifi *3

, Hamid Poursharifi *3

, Behrooz Dolatshahi2

, Behrooz Dolatshahi2

, Nastaran Habibi4

, Nastaran Habibi4

, Abbas Pourshahbaz2

, Abbas Pourshahbaz2

, Hamid Poursharifi *3

, Hamid Poursharifi *3

, Behrooz Dolatshahi2

, Behrooz Dolatshahi2

, Nastaran Habibi4

, Nastaran Habibi4

1- Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Islamic Republic of Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,poursharifi@gmail.com

4- Department of Psychiatry, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

4- Department of Psychiatry, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Keywords: Conduct disorder (CD), Comorbidity, Attention deficit-hyperactivity, Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory (MMPI), Adolescent

Full-Text [PDF 4249 kb]

(1460 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6152 Views)

Full-Text: (2248 Views)

Introduction

Conduct disorder (CD) is diagnosed as a developmental disorder and is classified in the externalizing group [1]. The indicator feature of this disorder is a repetitive and constant pattern of behavior in which a person violates the rights of others. The behaviors related to this disorder can be divided into four main groups as follows: Lying and stealing, vandalism, aggression, and violation of laws [2، 3]. This disorder is more similar to personality disorders, and in contrast to the episodic nature of other disorders, such as depression, has a chronic nature [4]. CD is one of the main reasons for patients referring to psychological clinics at school age, although it has not been studied sufficiently.

The prevalence of CD has been estimated at 2% to 2.5% worldwide. It affects 3% to 4% of boys and 1% to 2% of girls. Furthermore, prevalence studies demonstrate that 10% of people are affected by this disorder at some stage of childhood and adolescence. Concerning the symptoms related to the different age disorders, evidence supports changes according to age. With increasing age, the number of aggressive behaviors decreases, and nonaggressive symptoms, especially crimes, increase during adolescence [5، 6]. CD disturbs people’s social, occupational, and academic performance and carries a high social and economic burden. The global health burden index ranks higher than attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder [7]. Moreover, the incidence of this disorder in Iran is reported to be nearly similar to the numbers globally [8]. Considering the nearly high prevalence of this disorder, it is vital to consider this issue.

Similar to many childhood disorders, the coexistence of CD with other emotional and behavioral problems is common. Among the common psychiatric disorders with high comorbidity risk with CD are ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, substance abuse, and depression [9]. ADHD is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder that is associated with symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity [3]. The comorbidity of ADHD and CD has been discussed for a long time [9–11]. According to both epidemiological and clinical studies, the comorbidity of ADHD and CD is estimated to occur in 30% to 50% of cases [12]. Moreover, the incidence of ADHD in children with CD is ten times greater compared to children without CD. Coinfection with ADHD and CD is associated with decreased age, more severe symptoms, and more stable periods of the disorder [12، 13]. The results of this study regarding the comorbidity of these two disorders focused on a combination of impulsive-antisocial traits and callous-unemotional traits, such as a lack of guilt, superficial emotions, and instrumental and cruel use of others [14]. Some findings suggest that the comorbidity of these two disorders in childhood and adolescence can be associated with more chronic psychiatric disorders, such as psychosis in adulthood, although the findings are not definite [15، 16]. As a result, ADHD and CD can affect psychological symptoms and the severity of the disorder. Meanwhile, incorrect evaluation of psychopathological co-occurring conditions increases the chance of a false diagnosis. Therefore, recognizing the symptoms related to the disorder and considering its differences from associated disorders can be useful in treatment plans.

Narrow-band measures, such as the child behavior checklist and the strengths and difficulties questionnaire provide incremental helpful information about symptoms and psychopathological CD comorbidity [17]. The Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory adolescent (MMPI-A) is used as a broad-band tool to evaluate personality and psychopathology traits in the adolescent population [18]. MMPI-2 and its subsequent versions, the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory adolescent-restructured form (MMPI-A-RF), provide a complex set of main scales that evaluate the validity of symptoms and extensive psychopathology [19]. This tool has been standardized in Iran, and its diagnostic validity has been investigated for several disorders [20-22]. The MMPI-A-RF was developed in response to limitations related to the MMPI-A, such as high intercorrelations between clinical scales, low diagnostic validity in clinical constructs, overlap of scale items, and test duration [23]. Considering that the MMPI-A has similar strengths and weaknesses to the MMPI-2, Archer et al. sought to design the MMPI-A based on the success of the MMPI-2-RF project. The primary goals of this questionnaire were to create criteria for measuring depression in teenagers, identify the main components of clinical scales using exploratory factor analysis, which is different from depression, design more basic scales, create scales valid for random responding, exaggerate problems and underreporting, and revise personality pathology scales (PSY-5) using the MMPI-A-RF questionnaire. Another important factor in creating the MMPI-A-RF was the total length of the test. A total of 478 items on the MMPI-A could cause trouble in terms of attention and concentration in adolescents. Hence, it was important for the creators of the questionnaire to have fewer than 250 items. The authors intended to maintain comparability with the MMPI-2-RF to facilitate easy transfer between the two forms. To achieve this purpose, they used the MMPI-2-RF as a starting stage for identifying the relevant items that formed the primary scales of the MMPI-A-RF. However, not all items from the MMPI-2-RF could be directly transferred to the set of MMPI-A items, and vice versa. Despite sharing similar scale names and measuring similar constructs, the two versions often showed different items. The creation and validation process included a sample of 15 128 adolescents from different environments, including correctional and educational centers, schools, and outpatient and inpatient centers, with a Mean±SD age of 61.15±1.8 years. This broad approach aimed to create a more efficient and effective assessment tool for teenagers [13، 23]. Nevertheless, despite the common use of this tool for adults, identifying problems related to adolescents is limited. In an investigation conducted in 2021, Chakranarayan et al. used the MMPI-A-RF questionnaire to distinguish the characteristics of adolescents with ADHD in clinical samples and comparison, with those with other mental disorders [24].

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have evaluated CD and comorbidities. Archer’s [25] investigation of indices related to depression and CD demonstrated that the scales (conduct problem) A-CON, A-CYN (cynicism), and immaturity are the best predictors of CD. In other studies of CD and its comorbidity with depression, they showed that people who are depressed and have CD disorders have elevations on the F, 0, 2, and 9 scales, while the depressed group has just elevations on the 2 and 0 scales [6]. Sharf and Rogers [26] investigated the diagnostic construct validity of the MMPI-A-RF in youth with mental health needs and found that antisocial behavior is a strong predictor of externalizing disorders such as CD. According to the conducted research, little information is available regarding the comorbidity of these disorders and their power in differentiating disorders. Considering the widespread prevalence of CD and the unknown role of comorbidities of this disorder in the clinical table of symptoms, course, prognosis, and treatment of this disorder, this study determines the profiles of MMPI-A-RF in adolescents with CD and investigates the effect of its coexistence with ADHD. The questions related to this topic during the research process were as follows: “In the MMPI-A-RF questionnaire, what are the scales elevated in the conduct disorder group and the comorbidity group of conduct disorder and attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder?” and “Is there a difference between the two groups of conduct disorder and the comorbidity group of conduct disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in elevated scale?”

Materials and Methods

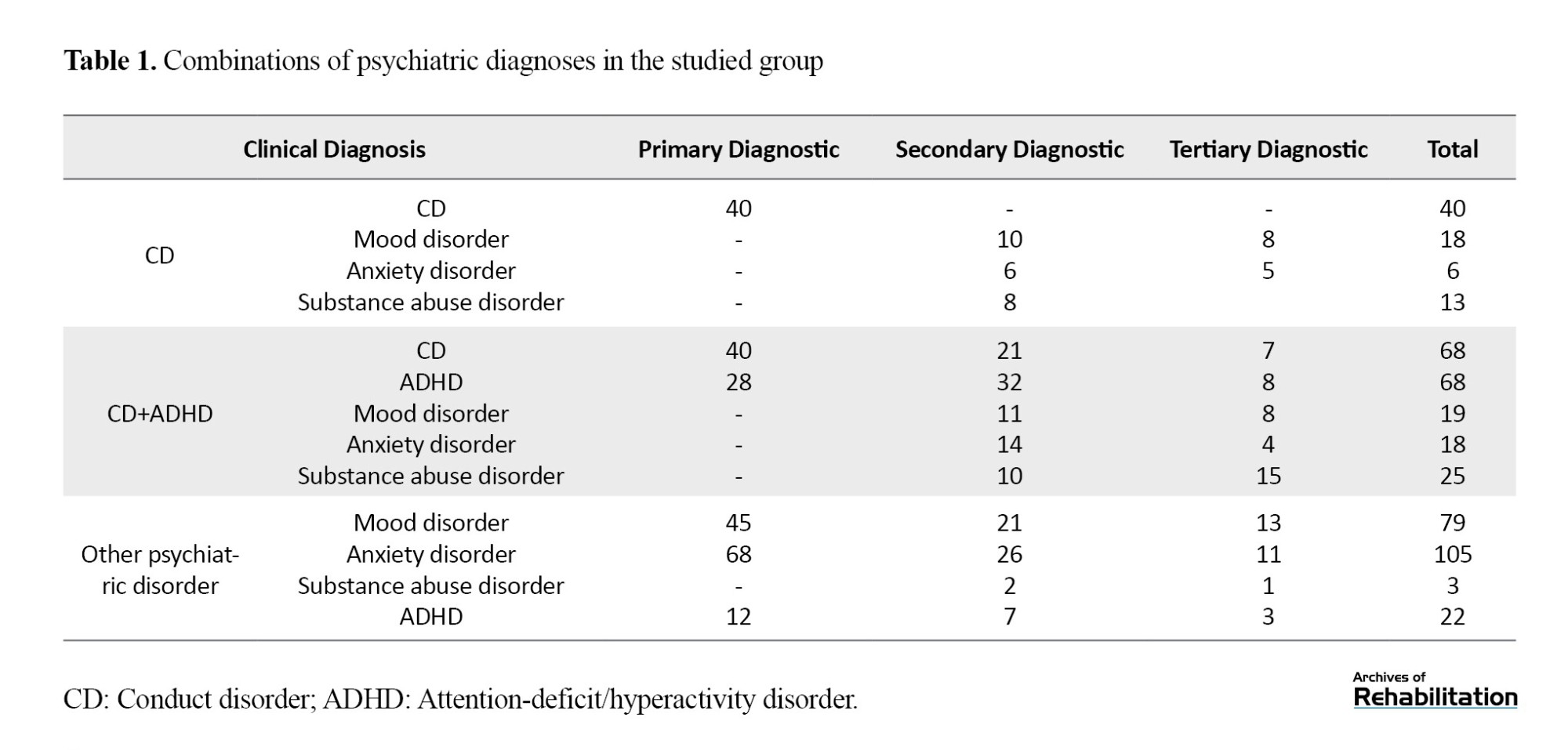

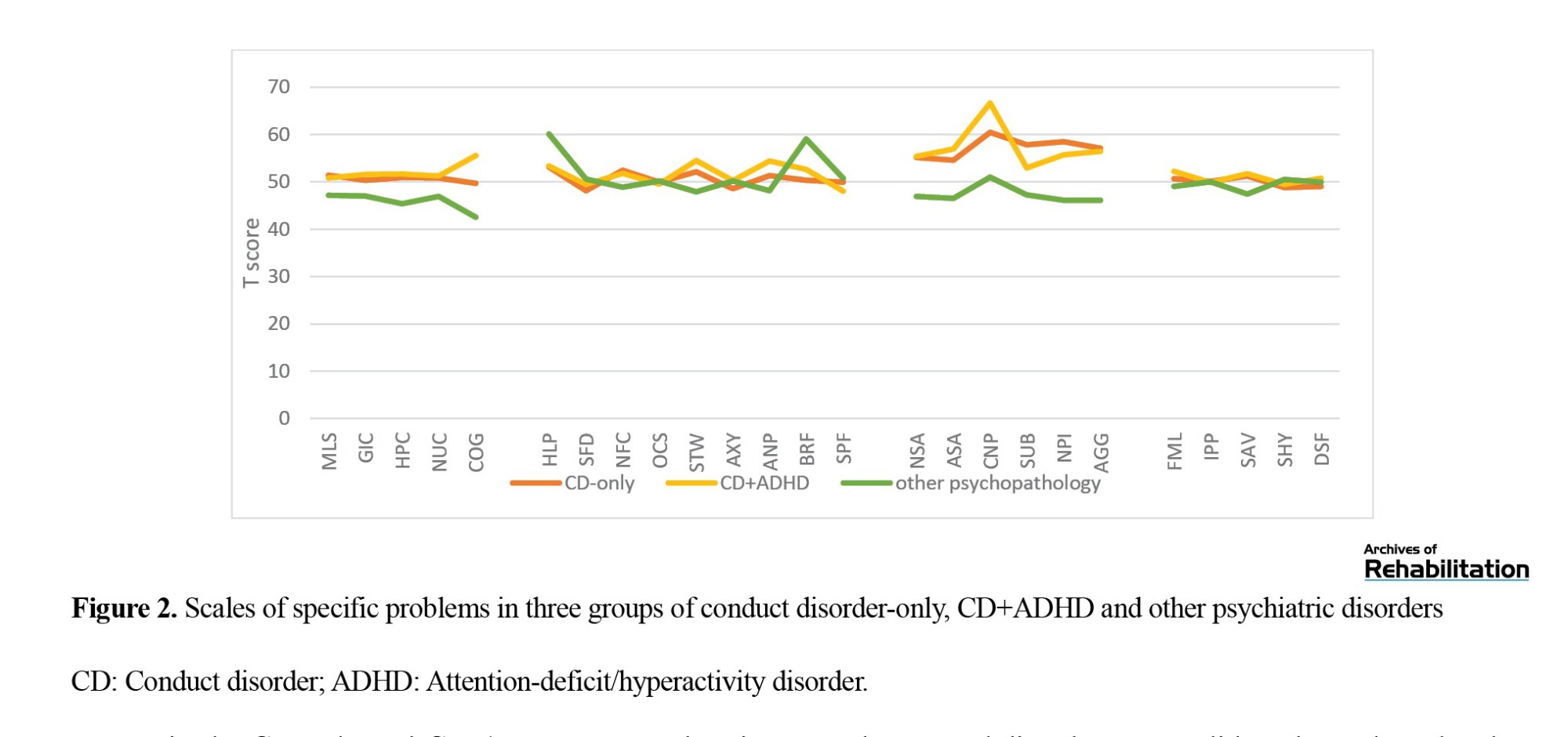

This was a comparative-causal study. The population of the present study included adolescents suffering from psychological disorders referred to the Nezam Mafi Rehabilitation Treatment Center, Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Atiyeh Zehn Clinic, Juvenile Detention Center, and several private clinics and counseling centers affiliated to the Ministry of Education were in 2013 to 2014. The sample group included 310 patients with psychological disorders who were selected from the target population via the purposeful sampling method. The researchers’ relative number of adolescents who suffer from psychological disorders and who are referred to the mentioned centers was 800-900 individuals. According to the Morgan table, 260-269 individuals were sufficient as a sample. Due to the possibility of dropping out of several participants in the sample group, 310 people were selected by intended sampling during the period mentioned above. Disorders of the spectrum were externalizing. The exclusion criteria were having other psychiatric diagnoses and mental retardation. Additionally, 15 profiles were omitted because they did not meet the validity of the manual MMPI-A-RF, as “cannot say” <10, “variable response inconsistency” <75, “true response inconsistency” <75, “combined response inconsistency” <75, and “infrequent responses” <90. The last sample included 295 people (CD=40; CD+ADHD=68, and other psychiatric disorders=187). The demographic information of the sample is given in Table 1.

Psychiatric diagnoses were built based on the Iranian version of the Kiddie schedule for affective disorder and schizophrenia-present and lifetime rating by trained therapists. Therapists with master’s degrees in clinical psychology, counselors of schools and correctional centers with master’s degrees, and doctoral students in clinical psychology participated in personal and online discussions during a 1-h session to accomplish interviews and necessary training. Adolescents received up to three diagnoses based on the Kiddie schedule for affective disorder and schizophrenia-present and lifetime. Table 1 provides the detailed psychiatric diagnoses of the participants.

All the participants voluntarily participated in the present study, and they did not charge any fees for participating. If the participants requested, the test results were reported to them. In addition, this study was approved by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Study measures

Questionnaire assessing demographic characteristics

A questionnaire obtained demographic and personal information. The information examined in this research included sex, date of birth, educational grade, field of study, grade point average, birth order, parents’ education, and psychological status.

MMPI-A-RF

The reorganized form of the MMPI-A-RF tool is influenced by the theoretical foundations and methodology of the MMPI-2-RF. This self-reported tool contains 241 true/false items extracted from 478 items of the MMPI-A questionnaire. The MMPI-A-RF is designed to assess adolescent psychopathology in clinical, academic, judicial, and medical settings. This questionnaire includes a total of 48 scales: 8 validity scales (inconsistency of variable answers, inconsistency of correct answers, inconsistency of combined responses, prevalent responses, unusual superiority, validity adaptability), 3 higher order scales (emotional dysfunction/internalizing, behavioral dysfunction, behavioral dysfunction/externalizing), 9 revised clinical scales (depression, physical complaints, insignificant positive emotions, pessimism, antisocial behavior, malicious thoughts and injury, negative feelings, dysfunction, abnormal experiences, hypomanic activation), 25 scales of specific problems, and 5 scales of personality pathology (aggressive-revised, psychoticism-revised, unrestrained-revised, neuroticism-revised and introversion/positive excitability [minor-revision]). The scale of specific problems includes physical/cognitive scales (weakness, gastrointestinal complaints, headache complaints, neurological complaints, cognitive complaints), internalization (impotence/despair, self-doubt, unhelpfulness, obsessive/compulsive, stress, worry/anxiety, quick-tempered, behavioral-limiting fears, specific fears), externalization (negative school attitude, antisocial attitude, behavioral problems, drug abuse, harmful effects of peers, aggression), and interpersonal family problems (being passive in interpersonal relationships, social avoidance, embarrassment, lack of connection with others) [23].

The questionnaire is psychometrically appropriate at the level of clinical diagnosis and subthreshold clinical diagnosis. The Cronbach α for all the scales was above 0.8, which is in line with previous studies [23]. It has also been validated in Iran with the Cronbach α at a proper level. The retest coefficients at all scales are above 0.89 as reported in other studies [27]. In the present study, the Persian version of the MMPI-A-RF questionnaire was provided to the researcher with the permission of the University of Minnesota, and its items were adapted by the institute to the cases of the Persian version of the MMPI-A [22] and the cases. The additions were omitted. No change in the Persian translation of the questions was allowed.

Kiddie schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia

A semi-structured diagnostic interview was designed to acquire information from adolescents, adolescents’ parents, or other custodians. This version of the Kiddie schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia has been revised for the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), and includes dimensional and categorical diagnostic assessments. Trained interviewers provided better clinical images of the symptoms in all diagnostic categories. By employing the interview, the researcher can acquire information about the previous episode (last six months) and the current episode. In this study, information related to the current episode was examined. This semi-structured interview included a screening section and six supplementary sections. The screening section included a preceding interview, the reason for the consultation, the patient’s general data, and the main symptoms of each disorder. When at least one sign is mentioned in the screening section, the supplementary section is executed. “Supplementary section 1” includes depression and bipolar disorders, “supplementary section 2” includes psychotic disorders, and the third section includes anxiety, stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Meanwhile, the fourth section includes destructive behavior disorders and impulse control disorders and the fifth section includes substance use disorders and eating disorders. The sixth section comprises neurodevelopmental disorders [28].

The tool has satisfactory validity and reliability. Francisco et al. reported a Kappa value above 0.7 for interrater reliability in more than half of the disorders [28]. Ghanizadeh et al. reported the reliability of the Persian version at 81.0 and the interobserver reliability at 69.0 based on retesting [29].

Statistical analyses

Mean±SD were calculated for all the MMPI-2-RF validity, higher-order, restructured clinical, and specific problem scales for the CD-only, CD with ADHD comorbidity (CD-ADHD), and other disorders comparison (referred to here as a psychi`atric comparison) groups, and analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to test for significant differences between groups across scales to determine which scales had different endorsement rates among the three study groups. The Levene test showed that the assumptions of using ANOVA are valid (P>0.001). All MMPI-2-RF variables were within acceptable limits in terms of skewness and kurtosis [30] and most were appropriately normally distributed, indicating that the F test was appropriate. The false discovery rate procedure, with a 0.05% maximum false discovery rate, was implemented to control the familywise error rate associated with multiple comparisons [31]. Effect sizes (partial Eta squared [[Ƞp2]]) for ANOVAs were interpreted as 0.01=small, 0.06=medium, and ≥0.14=large effects. For all ANOVAs with a significant overall effect, Games–Howell post hoc tests were used to examine pairwise differences across groups.

Results

In all the studied samples, 55.9% (n=165) were girls, and 44.1% (n=130) were boys, with a Mean±SD age of 15.9±1.18 years. The majority of the participants, 43.4% (n=128) of the father's education level was a diploma, and 49.2% (n=145) of the mother's education level was a diploma. In the occupational status index, 63.1% (n=186) of the fathers were self-employed, and 72.2% (n=213) of the mothers were housewives.

Additionally, the results of the chi-square test and the ANOVA did not reveal any significant differences among the three studied groups in terms of demographic characteristics (P>0.05).

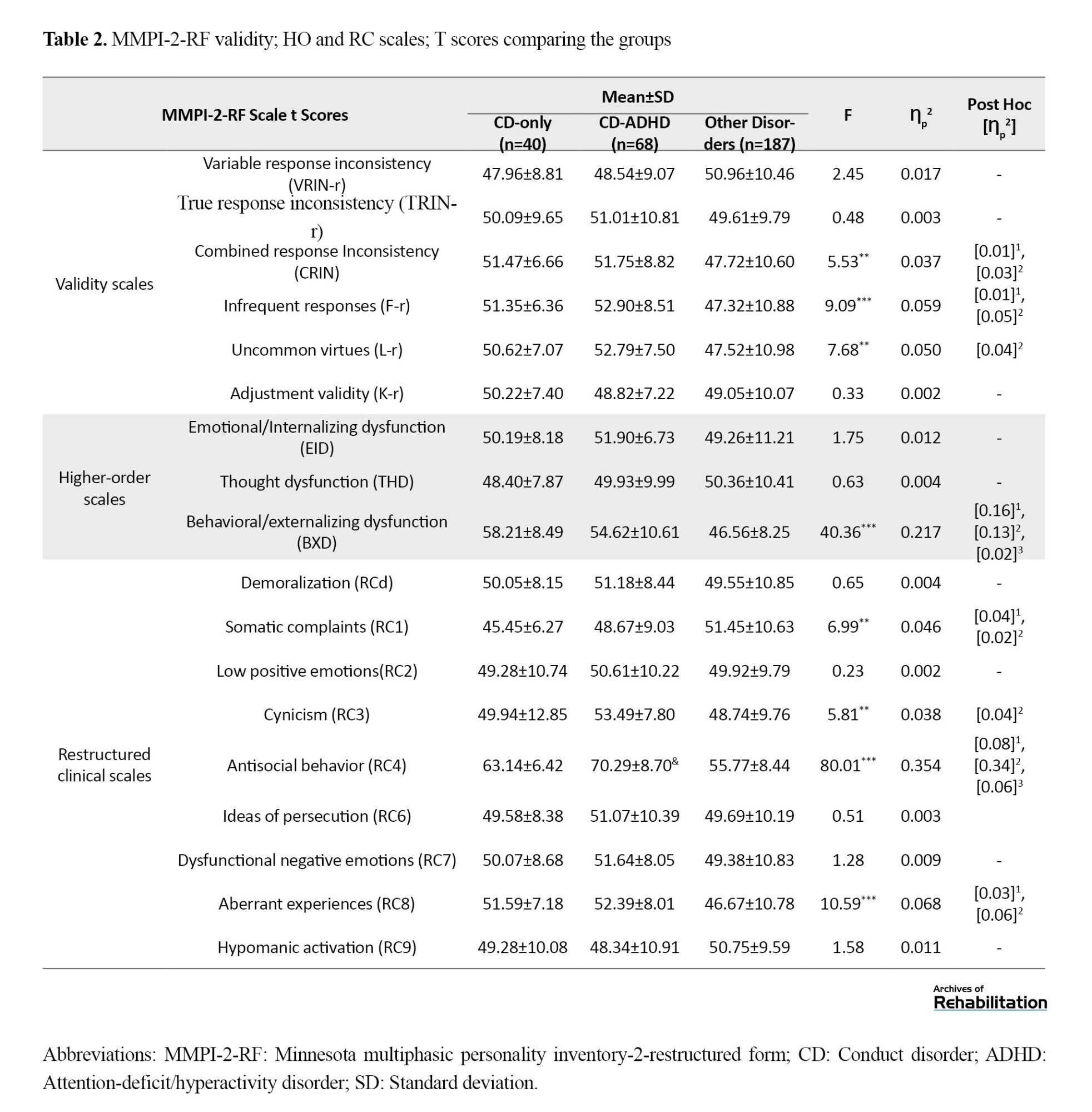

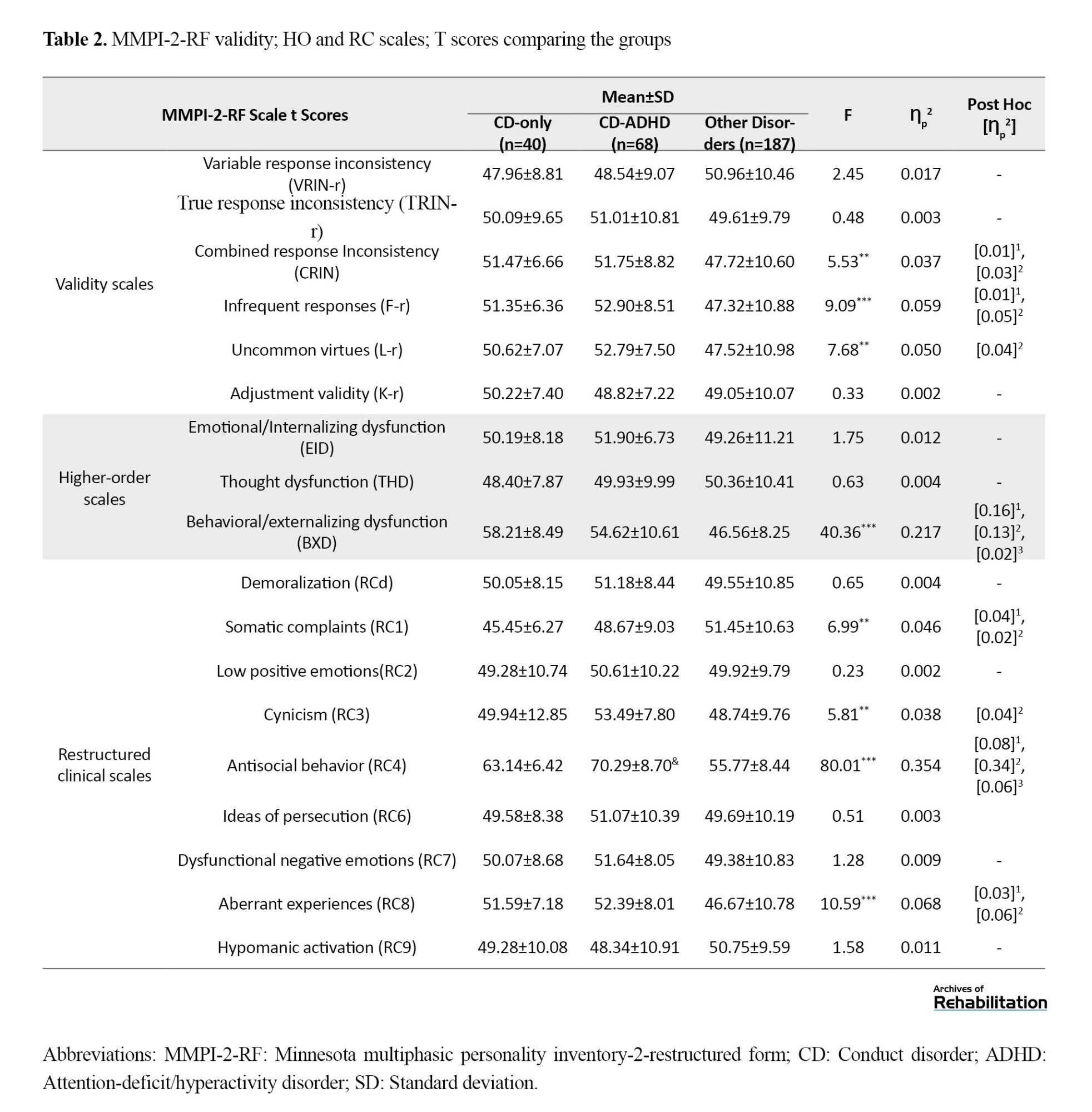

The Mean±SD scores of the scales of validity, higher-order, and restructured clinical scales of the MMPI-2-RF questionnaire in three groups of adolescents with CD-only, CD-ADHD, and other disorders are shown in Table 2. Only the mean antisocial behavior scale scores in the CD-ADHD disorder group were clinically significant (t≥65).

There was a significant difference between the three studied groups in the three subscales of the combined response inconsistency, infrequent responses, and uncommon virtues of the narrative scale (P<0.001). Accordingly, the mean scores of these subscales were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups compared to other groups of disorders. Moreover, the effect size was low.

There was a considerable difference between the three studied groups only in the behavioral/externalizing dysfunction subscale of the higher-order scale (P<0.001). The mean scores on this subscale were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups compared to the other disorders group. The effect size was moderate. In addition, on this scale, the mean survival time of the CD-only group was greater than that of the CD-ADHD group, but the effect size was slight.

There was a notable distinction between the three studied groups in the four subscales somatic complaints, cynicism, antisocial behavior, and aberrant experiences of the revised clinical scale (P<0.001). Therefore, the mean scores of the antisocial behavior and aberrant experiences subscales in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups were greater than those in the other disorders group. Similarly, the effect sizes ranged from low to high. Furthermore, on the antisocial behavior scale, the mean score in the CD-ADHD group was greater than that in the CD-only group, but the effect size was small.

Furthermore, the mean scores on the cynicism subscale were greater in the CD-ADHD group than in the group with other disorders. On the somatic complaints scale, the mean mortality in the other disorders group was greater than that in the other two groups.

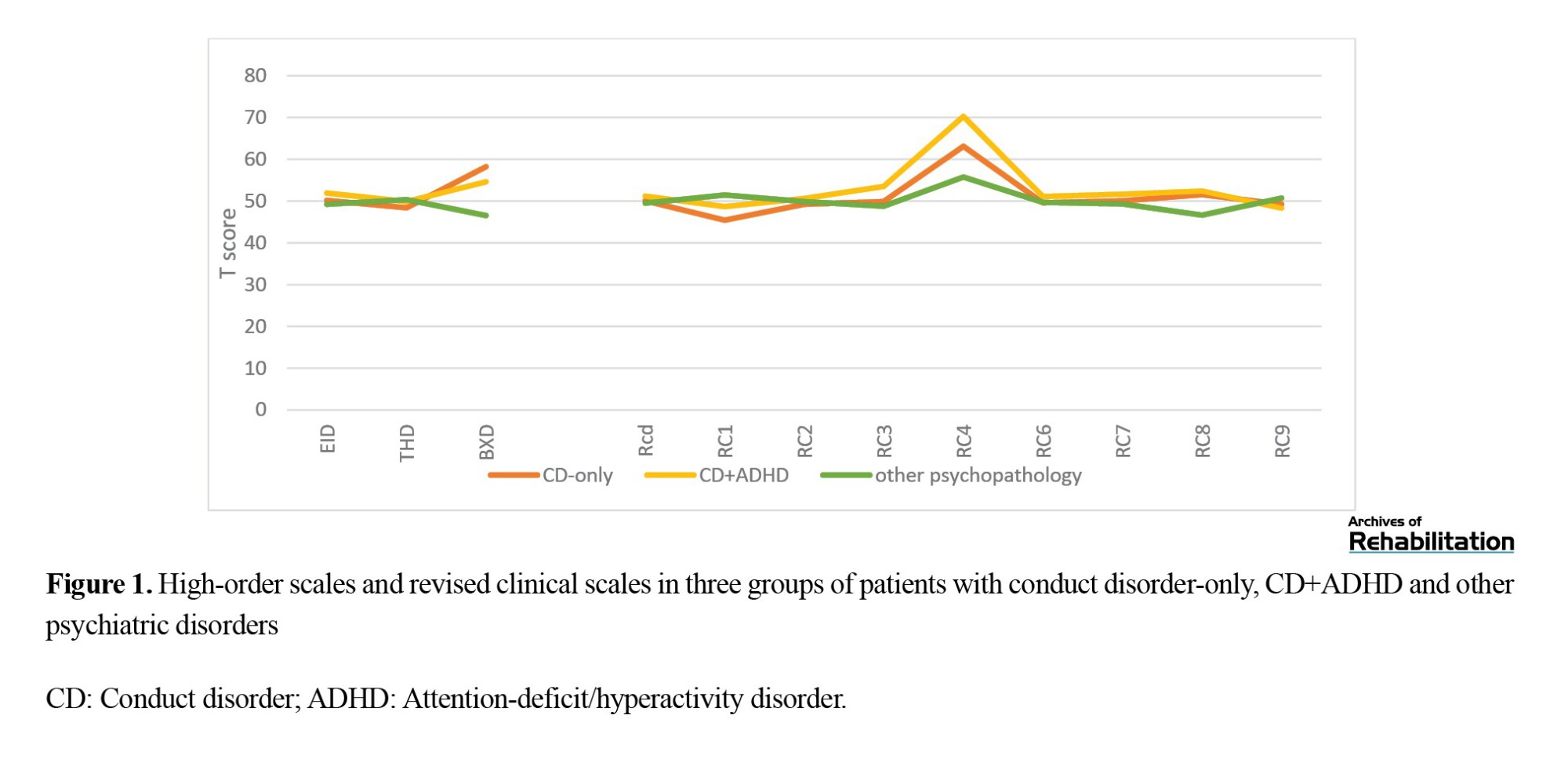

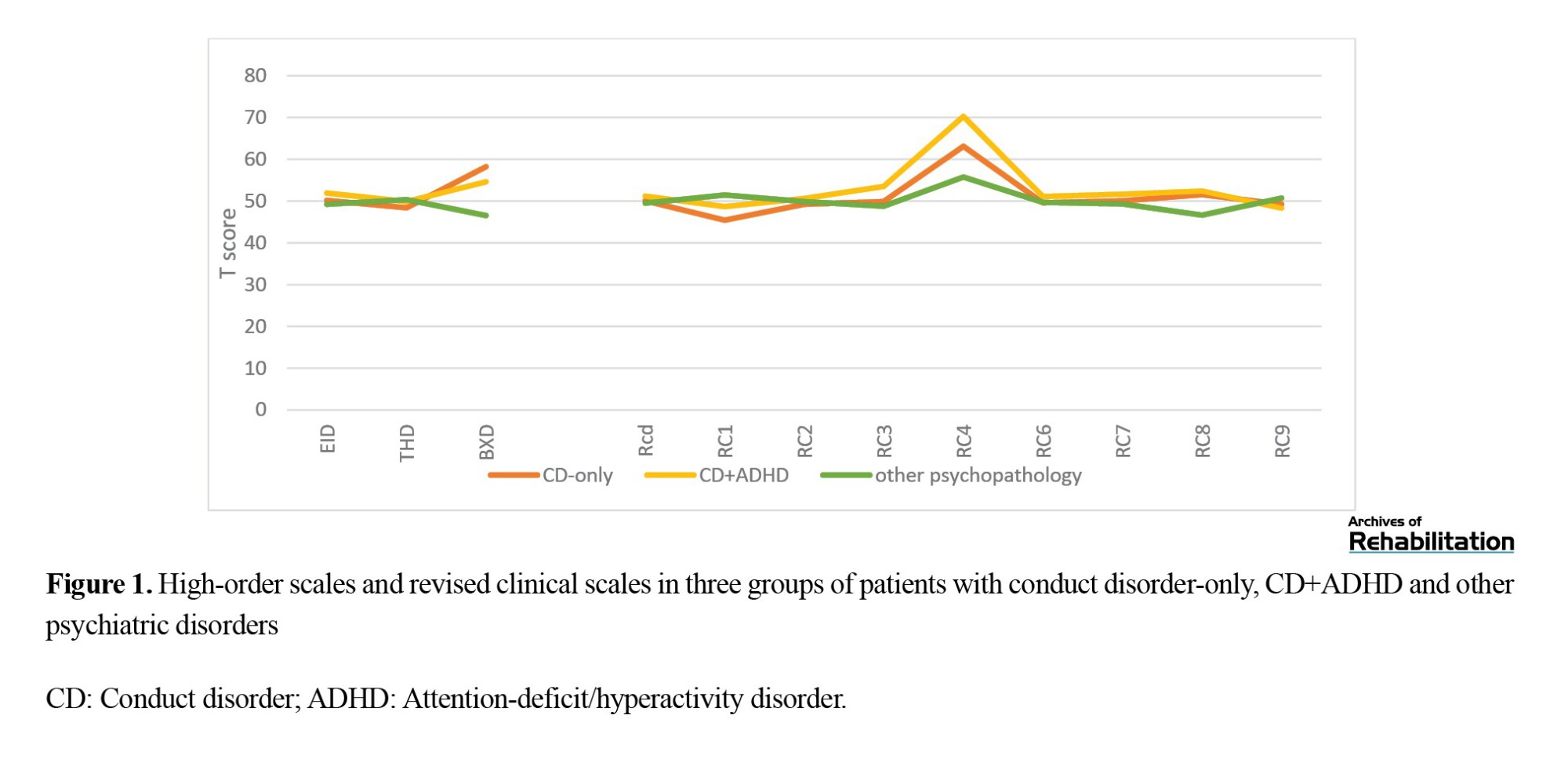

Figure 1 shows the individual high-order scale and revised clinical scale scores for the three groups, namely CD-only, CD+ADHD, and other psychopathology.

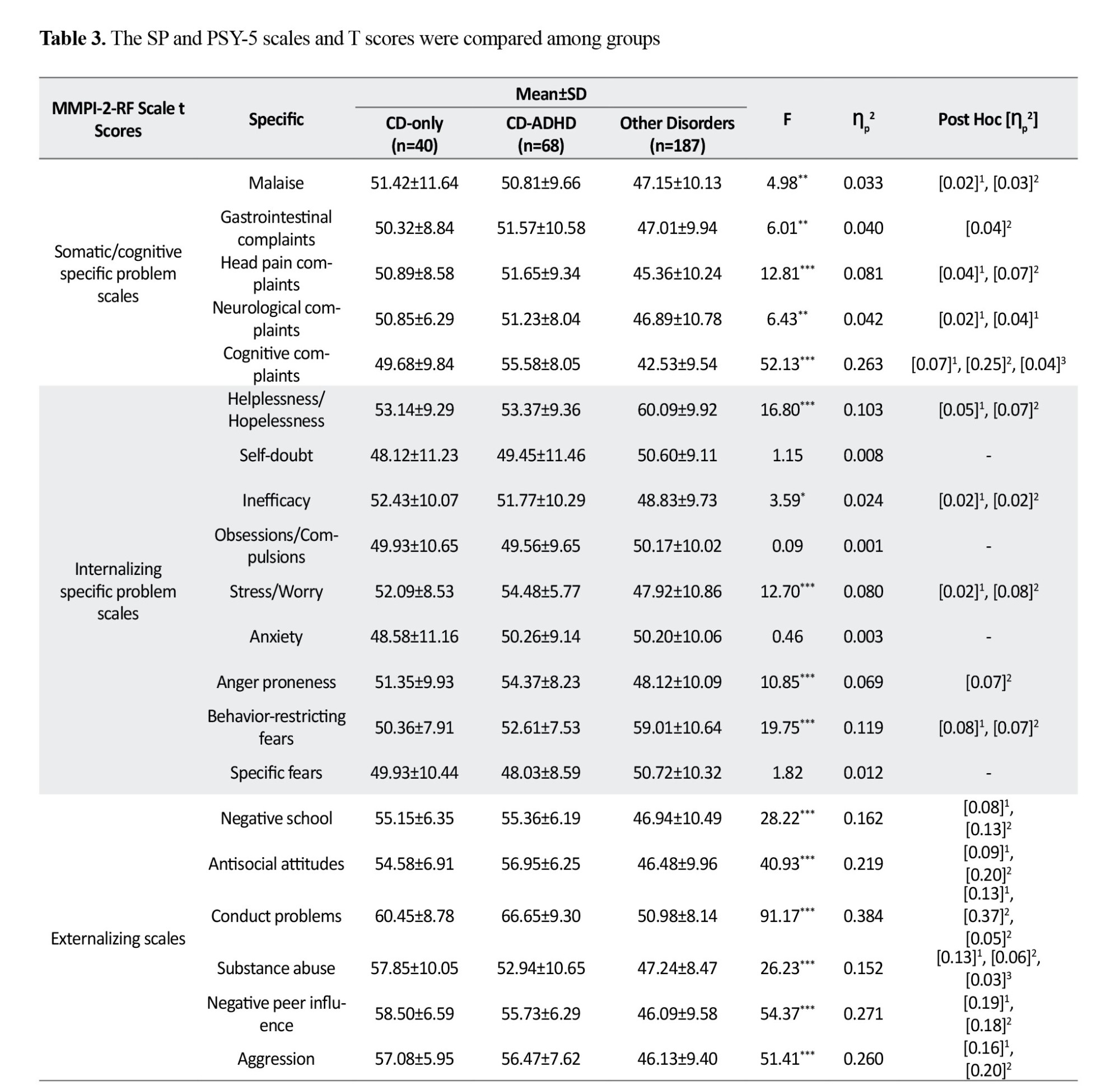

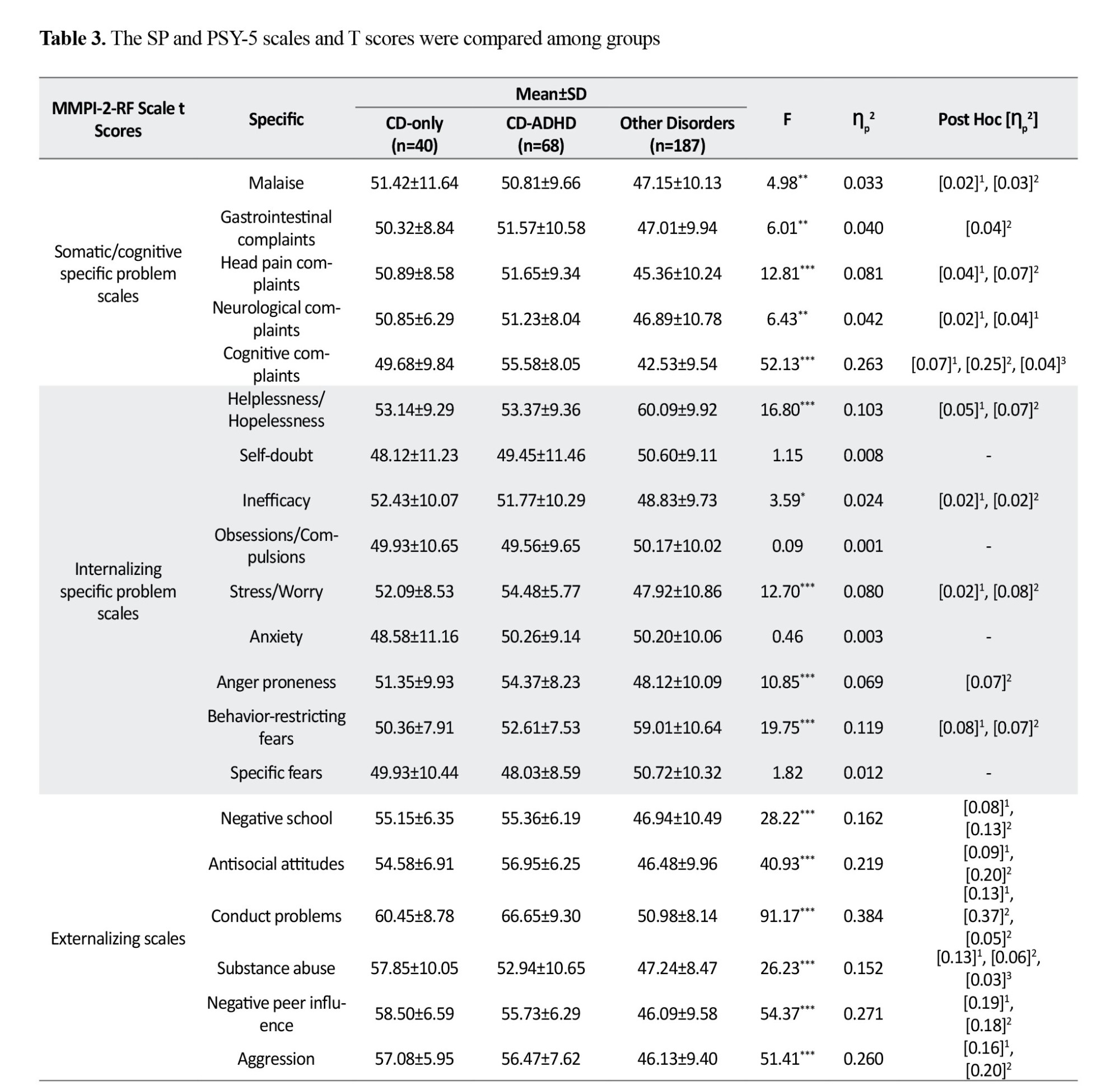

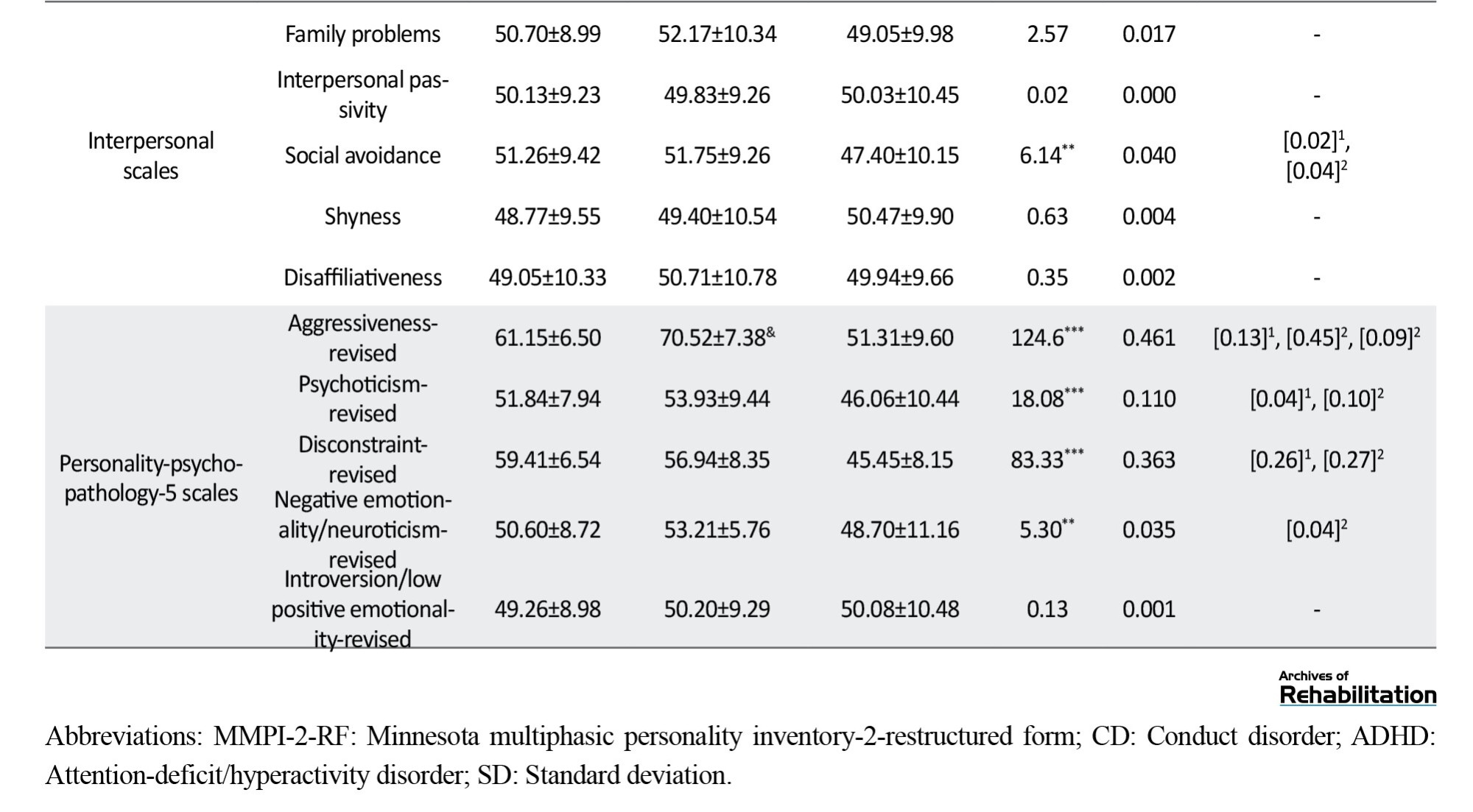

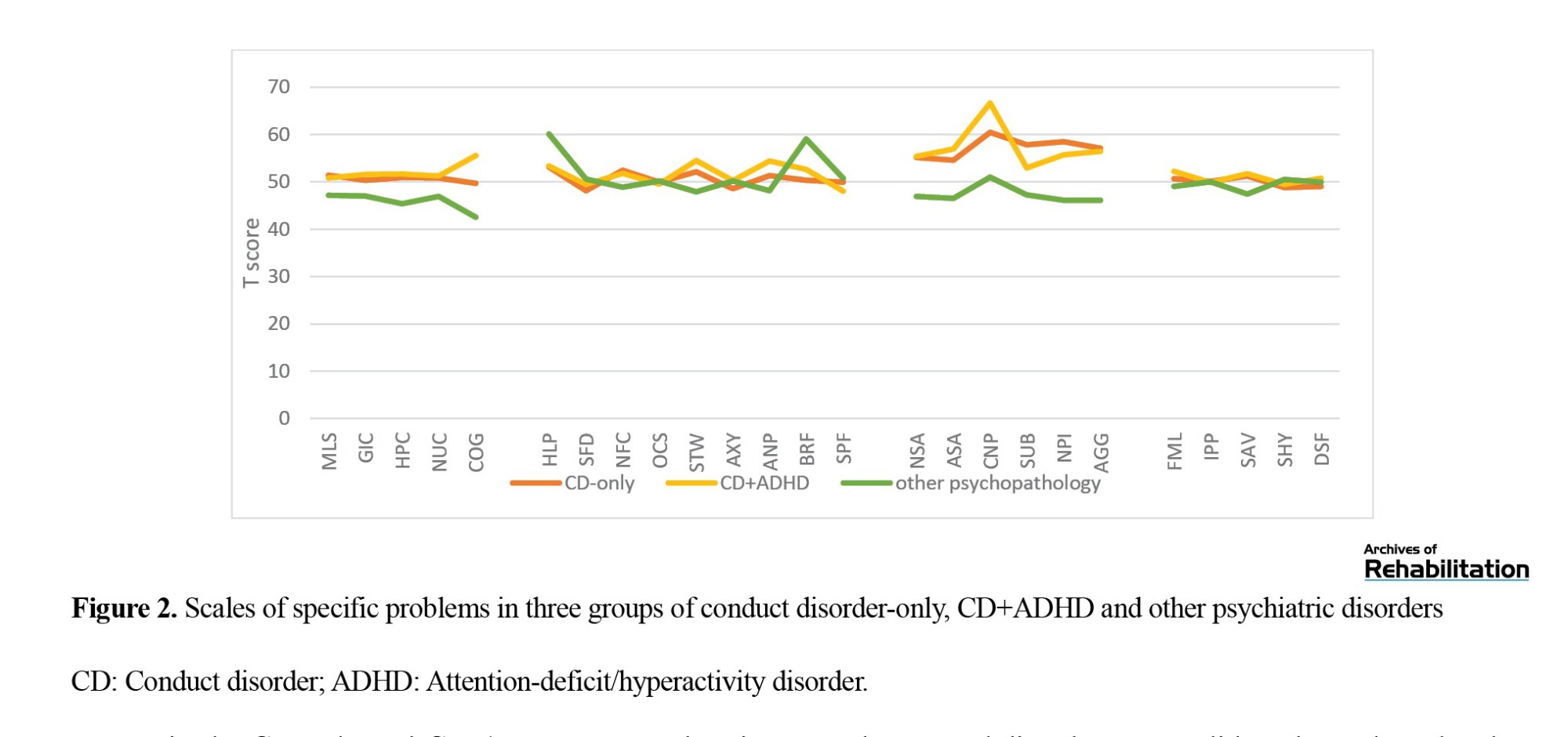

The Mean±SD of the specific problem scale scores on the MMPI-2-RF questionnaire in three groups of adolescents with CD-only, CD-ADHD, or other disorders are shown in Table 3. The mean conduct problems and aggressiveness-revised scores were clinically high in the CD-ADHD group (t≥65).

There was a significant difference between the three studied groups in all the somatic/cognitive subscale scores on the specific problem scale (P<0.001). Therefore, the mean scores on these subscales were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups than in the other disorders group. Additionally, the effect sizes ranged from low to high.

There was a significant distinction between the three studied groups based on the helplessness/hopelessness, inefficacy, stress/worry, anger proneness, and behavior-restricting fears subscales of the internalization scale (P<0.001). Therefore, the mean inefficacy, stress/worry, and anger proneness scores in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups were greater than those in the other disorders group. Correspondingly, the effect size was low to medium. Nonetheless, the mean scores of the HLP and BRF subscales in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups were lower than those in the other disorders group. Similarly, the effect size was low to medium.

There was a significant difference between the three studied groups in all subscales of the externalizing scale (P<0.001). Therefore, the mean scores on these subscales were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups than in the other disorders group. Furthermore, the effect sizes ranged from low to high. Additionally, on the SUB subscale, the mean scores of the CD-only group were greater than those of the CD-ADHD group. Furthermore, on the conduct problems subscale, the mean score in the CD-ADHD group was greater than that in the CD-only group, but the effect size was small.

There was a notable difference between the three study groups only in the social avoidance subscale of the interpersonal scale (P<0.001). In this manner, the mean scores on this subscale were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups than in the group with other disorders. The effect size was small.

There was a significant difference between the three studied groups on all subscales of the personality pathology (except for the introversion/low positive emotionality-revised; P<0.001). Therefore, the mean scores of the three subscales aggressiveness-revised, psychoticism-revised, and disconstraint-revised were significantly greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups than in the other disorders group. Furthermore, for the negative emotionality/neuroticism-revised and aggressiveness-revised subscales, the mean scores of the CD-ADHD group were greater than those of the other disorders group.

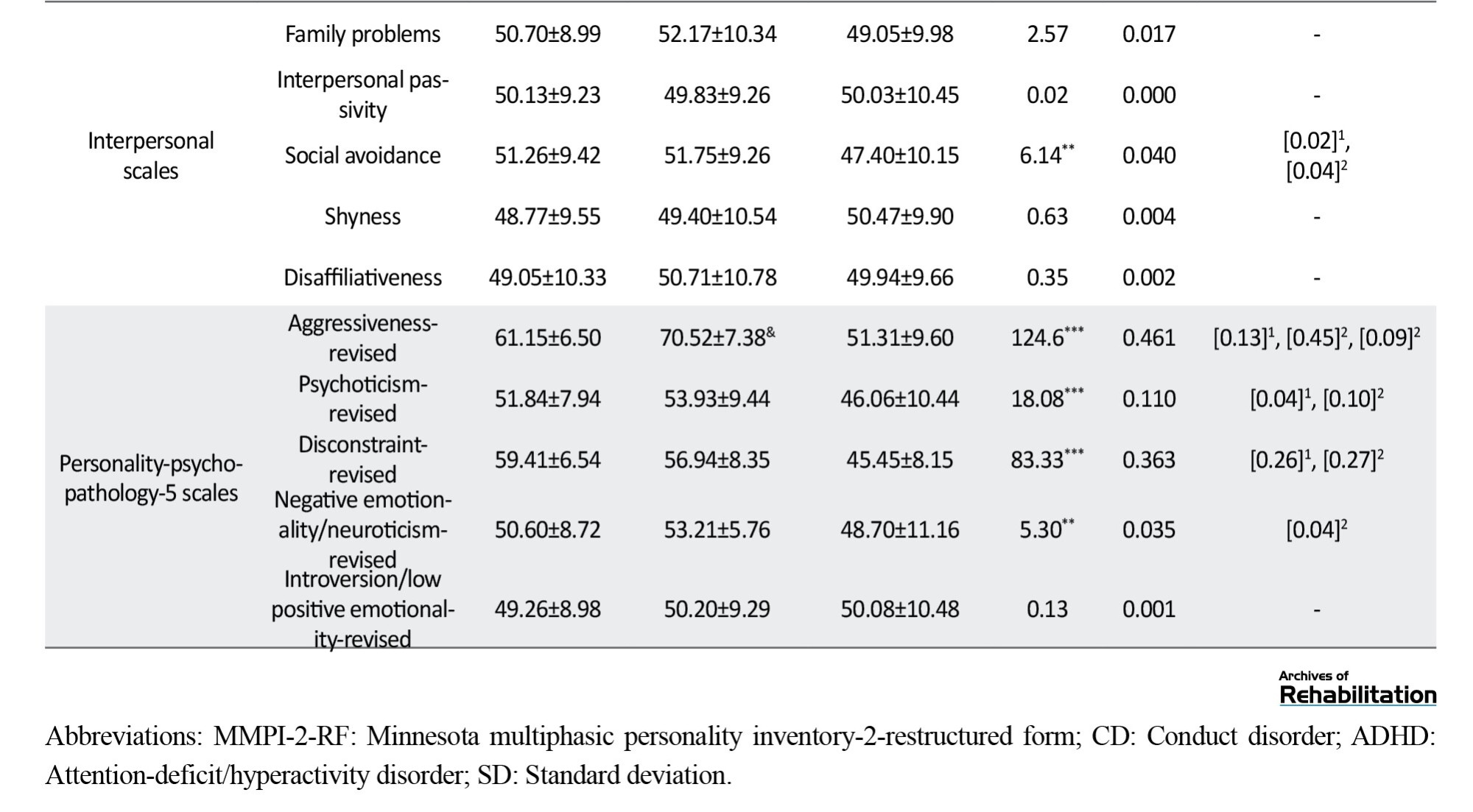

Figure 2 shows the scales of specific problems for the following three groups: CD-only, CD+ADHD, and other psychopathologies.

Discussion

This study investigated the clinical characteristics of conduct disorder and its comorbidity with impulsivity-hyperactivity in adolescent clinical samples. The results revealed that adolescents with conduct disorders and adolescents who were infected with CD and ADHD had greater levels of behavioral dysfunction, difficulty in regulating emotions, and problems in performance than those with normative scores on the MMPI-A-RF. This disorder is associated with defects in verbal skills, executive function, and the lack of balance in activation and inhibition systems of behavior [32].

According to the results of previous studies [10، 12، 13، 33، 34], a considerable difference was observed between the CD and CD+ADHD groups and the other psychiatric disorders group in terms of the scores related to externalizing concern. With the structure of the questionnaire, the MMPI-A-RF scales, which were organized hierarchically, move from broad psychopathology structures (high-order scales) to narrowband scales (specific problem scales). At each level of the hierarchy, the CD+ADHD group scored significantly greater than the other mental disorders group did on the scales related to behavioral disorders and aggression (P<0.001).

Moreover, regarding the second hypothesis, the CD+ADHD group was related to more symptoms and greater functional degradation. These results were consistent in some cases, and we observed that the CD+ADHD group had markedly greater scores than did the CD group and other psychiatric disorders according to the RC4 scale, which is associated with antisocial behaviors. Furthermore, a significant difference was observed in the specific problems level on the conduct problems and substance abuse scales, which, in agreement with the background, could predict more severe psychopathology in the CD+ADHD group than in the CD group (P<0.001).

Another significant difference between the CD and CD+ADHD groups was in symptoms related to depression and anxiety (stress/worry, inefficacy, helplessness/hopelessness) due to the high comorbidity of CD with depression symptoms and mixed anxiety symptoms. Depression may indicate subthreshold diagnoses that have caused changes in the process of diagnosis [25، 35]. This issue can double the importance of dimensional investigation of disorders. In the dimensional system, the problem of subthreshold diagnosis has been solved. The hierarchical classification of the psychopathology model is a step in addressing problems related to arbitrary diagnostic boundaries (such as subthreshold cases), which solves the problem of heterogeneity within disorders by constructing dimensions based on observed changes in symptoms and identifying coherent structures of disorders. This model includes both transitional symptoms and persistent incompatible characteristics [36].

The results of the present study indicated that, in the field of problems related to interpersonal relationships, except for the social avoidance scale, there was no significant difference between the three groups on the other scales. A background review revealed that it is crucial to distinguish between behavioral inhibition (such as anxiety and shyness) and social withdrawal associated with delinquency. According to a longitudinal study of a 10- to 12-year-old sample and follow-up data at the age of 13-15 years, behavioral inhibition and not withdrawal are protective factors for the negative prediction of delinquency; on the other hand, withdrawal is considered a risk factor for crime. Boys who were disruptive and withdrawn were three times more likely to commit delinquency and depression. Although the behaviors of individuals with anxiety caused by shyness and social withdrawal are similar, their consequences for behavioral problems can be quite different [6]. However, this topic has been less studied, and additional investigations are needed.

The present study is the first to use the MMPI-A-RF to examine the clinical presentations of CD and its cooccurrence with hyperactivity in a clinical sample. Due to the hierarchical structure of the MMPI-A-RF, it provides helpful information regarding higher levels of pathology, disease symptoms, co-occurrence with other disorders with CD, and changes in the clinical presentations of disorders and functional disorders in areas such as interpersonal functioning.

Conclusion

According to the hierarchical structure of the MMPI-A-RF, if we want to have a view of the personality profile of adolescents with CD in mind, considering the following indicators will greatly improve the results:

1- At the highest level of psychopathology, the behavioral/externalizing dysfunction scale is an accurate indicator for diagnosing behavioral disorders.

2- At the level of the revised clinical scale, antisocial behavior is the main index of the scale for diagnosing conduct disorders, and the greater the elevation of this scale is, the greater the destruction and possibility of cooccurring with ADHD. Meanwhile cynicism and aberrant experiences provide practical information about this disorder in the second step.

3- It is necessary to focus on two points through the specific problems. First, most of the indicators are higher than those of other psychiatric disorders, and second, the two key scales, conduct problems and substance abuse, can distinguish this disorder from other disorders. The cognitive complaints scale is also a suitable index for diagnosing the cooccurrence of conduct disorders with ADHD.

4- Through personality pathology, the three key indicators in the diagnosis of conduct disorder are aggressiveness-revised, psychoticism-revised, and disconstraint-revised. Meanwhile, the intensity of elevation in aggressiveness-revised indicates the possibility of coexistence of these disorders and it increases with ADHD.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in which the difference between these presentations was evaluated in the MMPI-A-RF cohort, and the findings of this study could be useful for differentiating between presentations of conduct disorders using the MMPI-A-RF. Although these differences are evident in a large sample of people, their diagnostic application at the individual level needs much investigation, and clinicians should be careful not to rely too much on increasing the MMPI scale. A-RF or its absence should be cautiously considered when diagnosing specific CD presentations at the individual level.

Study limitations

One of the significant limitations was the lack of split ADHD clusters (hyperactive, attention deficit, and combined type), which can supply more precise information about the CD+ADHD profile. Moreover, we asked whether individuals with attention deficiency had higher scores on cognitive complaints and internalizing scales and whether the combined type of attention deficiency was associated with greater destruction in individuals with behavioral disorders. All these cases are hypotheses that can be the subject of further study.

Another limitation was the lack of control of medication status. The use or nonuse of medication was not taken into account at the time of completing the questionnaire, which could lead to misinterpretation of the relationship between medication status and test results. Finally, the individuals in the conduct disorder group and the conduct disorder group with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder included all clinical cases that met the criteria for these two disorders, and we did not differentiate between primary diagnoses and second and third diagnoses. The manifestations of the symptoms at the primary diagnosis and the second and third diagnoses may be different and can be investigated in a separate study. In conclusion, the use of larger and more homogeneous samples allows this study to be more accurate and comprehensive.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present article was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.153). Written consent was obtained from the participants and their parents to participate in the research. All participants freely participated in the research and had the right to withdraw from the research. No fee w:::::::::::as char:::::::::::ged for participating in the research, and the researchers respected the basic principle of information confidentiality.

Funding

The present article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Marzieh Norozpour, approved by Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and validation: Marzieh Norozpour and Abbas Porschehbaz; Research: Marzieh Norozpour, Abbas Pourshahbaz, Hamid Poursharifi and Behrouz Dolatshahi; Data analysis: Marzieh Norozpour, Abbas Pourshahbaz and Hamid Poursharifi; Sources: Marzieh Norozpour; Drafting the initial manuscript: Marzieh Norozpour, Abbas Pourshahbaz and Hamid Poursharifi; Review, editing and final approval: All authors; Supervision: Abbas Pourshahbaz and Hamid Poursharifi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank and appreciate all the colleagues who cooperated with the researcher in the introduction

of patients with behavioral disorders to carry out the research.

Conduct disorder (CD) is diagnosed as a developmental disorder and is classified in the externalizing group [1]. The indicator feature of this disorder is a repetitive and constant pattern of behavior in which a person violates the rights of others. The behaviors related to this disorder can be divided into four main groups as follows: Lying and stealing, vandalism, aggression, and violation of laws [2، 3]. This disorder is more similar to personality disorders, and in contrast to the episodic nature of other disorders, such as depression, has a chronic nature [4]. CD is one of the main reasons for patients referring to psychological clinics at school age, although it has not been studied sufficiently.

The prevalence of CD has been estimated at 2% to 2.5% worldwide. It affects 3% to 4% of boys and 1% to 2% of girls. Furthermore, prevalence studies demonstrate that 10% of people are affected by this disorder at some stage of childhood and adolescence. Concerning the symptoms related to the different age disorders, evidence supports changes according to age. With increasing age, the number of aggressive behaviors decreases, and nonaggressive symptoms, especially crimes, increase during adolescence [5، 6]. CD disturbs people’s social, occupational, and academic performance and carries a high social and economic burden. The global health burden index ranks higher than attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder [7]. Moreover, the incidence of this disorder in Iran is reported to be nearly similar to the numbers globally [8]. Considering the nearly high prevalence of this disorder, it is vital to consider this issue.

Similar to many childhood disorders, the coexistence of CD with other emotional and behavioral problems is common. Among the common psychiatric disorders with high comorbidity risk with CD are ADHD, oppositional defiant disorder, substance abuse, and depression [9]. ADHD is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder that is associated with symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity [3]. The comorbidity of ADHD and CD has been discussed for a long time [9–11]. According to both epidemiological and clinical studies, the comorbidity of ADHD and CD is estimated to occur in 30% to 50% of cases [12]. Moreover, the incidence of ADHD in children with CD is ten times greater compared to children without CD. Coinfection with ADHD and CD is associated with decreased age, more severe symptoms, and more stable periods of the disorder [12، 13]. The results of this study regarding the comorbidity of these two disorders focused on a combination of impulsive-antisocial traits and callous-unemotional traits, such as a lack of guilt, superficial emotions, and instrumental and cruel use of others [14]. Some findings suggest that the comorbidity of these two disorders in childhood and adolescence can be associated with more chronic psychiatric disorders, such as psychosis in adulthood, although the findings are not definite [15، 16]. As a result, ADHD and CD can affect psychological symptoms and the severity of the disorder. Meanwhile, incorrect evaluation of psychopathological co-occurring conditions increases the chance of a false diagnosis. Therefore, recognizing the symptoms related to the disorder and considering its differences from associated disorders can be useful in treatment plans.

Narrow-band measures, such as the child behavior checklist and the strengths and difficulties questionnaire provide incremental helpful information about symptoms and psychopathological CD comorbidity [17]. The Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory adolescent (MMPI-A) is used as a broad-band tool to evaluate personality and psychopathology traits in the adolescent population [18]. MMPI-2 and its subsequent versions, the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory adolescent-restructured form (MMPI-A-RF), provide a complex set of main scales that evaluate the validity of symptoms and extensive psychopathology [19]. This tool has been standardized in Iran, and its diagnostic validity has been investigated for several disorders [20-22]. The MMPI-A-RF was developed in response to limitations related to the MMPI-A, such as high intercorrelations between clinical scales, low diagnostic validity in clinical constructs, overlap of scale items, and test duration [23]. Considering that the MMPI-A has similar strengths and weaknesses to the MMPI-2, Archer et al. sought to design the MMPI-A based on the success of the MMPI-2-RF project. The primary goals of this questionnaire were to create criteria for measuring depression in teenagers, identify the main components of clinical scales using exploratory factor analysis, which is different from depression, design more basic scales, create scales valid for random responding, exaggerate problems and underreporting, and revise personality pathology scales (PSY-5) using the MMPI-A-RF questionnaire. Another important factor in creating the MMPI-A-RF was the total length of the test. A total of 478 items on the MMPI-A could cause trouble in terms of attention and concentration in adolescents. Hence, it was important for the creators of the questionnaire to have fewer than 250 items. The authors intended to maintain comparability with the MMPI-2-RF to facilitate easy transfer between the two forms. To achieve this purpose, they used the MMPI-2-RF as a starting stage for identifying the relevant items that formed the primary scales of the MMPI-A-RF. However, not all items from the MMPI-2-RF could be directly transferred to the set of MMPI-A items, and vice versa. Despite sharing similar scale names and measuring similar constructs, the two versions often showed different items. The creation and validation process included a sample of 15 128 adolescents from different environments, including correctional and educational centers, schools, and outpatient and inpatient centers, with a Mean±SD age of 61.15±1.8 years. This broad approach aimed to create a more efficient and effective assessment tool for teenagers [13، 23]. Nevertheless, despite the common use of this tool for adults, identifying problems related to adolescents is limited. In an investigation conducted in 2021, Chakranarayan et al. used the MMPI-A-RF questionnaire to distinguish the characteristics of adolescents with ADHD in clinical samples and comparison, with those with other mental disorders [24].

To the best of our knowledge, few studies have evaluated CD and comorbidities. Archer’s [25] investigation of indices related to depression and CD demonstrated that the scales (conduct problem) A-CON, A-CYN (cynicism), and immaturity are the best predictors of CD. In other studies of CD and its comorbidity with depression, they showed that people who are depressed and have CD disorders have elevations on the F, 0, 2, and 9 scales, while the depressed group has just elevations on the 2 and 0 scales [6]. Sharf and Rogers [26] investigated the diagnostic construct validity of the MMPI-A-RF in youth with mental health needs and found that antisocial behavior is a strong predictor of externalizing disorders such as CD. According to the conducted research, little information is available regarding the comorbidity of these disorders and their power in differentiating disorders. Considering the widespread prevalence of CD and the unknown role of comorbidities of this disorder in the clinical table of symptoms, course, prognosis, and treatment of this disorder, this study determines the profiles of MMPI-A-RF in adolescents with CD and investigates the effect of its coexistence with ADHD. The questions related to this topic during the research process were as follows: “In the MMPI-A-RF questionnaire, what are the scales elevated in the conduct disorder group and the comorbidity group of conduct disorder and attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder?” and “Is there a difference between the two groups of conduct disorder and the comorbidity group of conduct disorder and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in elevated scale?”

Materials and Methods

This was a comparative-causal study. The population of the present study included adolescents suffering from psychological disorders referred to the Nezam Mafi Rehabilitation Treatment Center, Razi Psychiatric Hospital, Atiyeh Zehn Clinic, Juvenile Detention Center, and several private clinics and counseling centers affiliated to the Ministry of Education were in 2013 to 2014. The sample group included 310 patients with psychological disorders who were selected from the target population via the purposeful sampling method. The researchers’ relative number of adolescents who suffer from psychological disorders and who are referred to the mentioned centers was 800-900 individuals. According to the Morgan table, 260-269 individuals were sufficient as a sample. Due to the possibility of dropping out of several participants in the sample group, 310 people were selected by intended sampling during the period mentioned above. Disorders of the spectrum were externalizing. The exclusion criteria were having other psychiatric diagnoses and mental retardation. Additionally, 15 profiles were omitted because they did not meet the validity of the manual MMPI-A-RF, as “cannot say” <10, “variable response inconsistency” <75, “true response inconsistency” <75, “combined response inconsistency” <75, and “infrequent responses” <90. The last sample included 295 people (CD=40; CD+ADHD=68, and other psychiatric disorders=187). The demographic information of the sample is given in Table 1.

Psychiatric diagnoses were built based on the Iranian version of the Kiddie schedule for affective disorder and schizophrenia-present and lifetime rating by trained therapists. Therapists with master’s degrees in clinical psychology, counselors of schools and correctional centers with master’s degrees, and doctoral students in clinical psychology participated in personal and online discussions during a 1-h session to accomplish interviews and necessary training. Adolescents received up to three diagnoses based on the Kiddie schedule for affective disorder and schizophrenia-present and lifetime. Table 1 provides the detailed psychiatric diagnoses of the participants.

All the participants voluntarily participated in the present study, and they did not charge any fees for participating. If the participants requested, the test results were reported to them. In addition, this study was approved by the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Study measures

Questionnaire assessing demographic characteristics

A questionnaire obtained demographic and personal information. The information examined in this research included sex, date of birth, educational grade, field of study, grade point average, birth order, parents’ education, and psychological status.

MMPI-A-RF

The reorganized form of the MMPI-A-RF tool is influenced by the theoretical foundations and methodology of the MMPI-2-RF. This self-reported tool contains 241 true/false items extracted from 478 items of the MMPI-A questionnaire. The MMPI-A-RF is designed to assess adolescent psychopathology in clinical, academic, judicial, and medical settings. This questionnaire includes a total of 48 scales: 8 validity scales (inconsistency of variable answers, inconsistency of correct answers, inconsistency of combined responses, prevalent responses, unusual superiority, validity adaptability), 3 higher order scales (emotional dysfunction/internalizing, behavioral dysfunction, behavioral dysfunction/externalizing), 9 revised clinical scales (depression, physical complaints, insignificant positive emotions, pessimism, antisocial behavior, malicious thoughts and injury, negative feelings, dysfunction, abnormal experiences, hypomanic activation), 25 scales of specific problems, and 5 scales of personality pathology (aggressive-revised, psychoticism-revised, unrestrained-revised, neuroticism-revised and introversion/positive excitability [minor-revision]). The scale of specific problems includes physical/cognitive scales (weakness, gastrointestinal complaints, headache complaints, neurological complaints, cognitive complaints), internalization (impotence/despair, self-doubt, unhelpfulness, obsessive/compulsive, stress, worry/anxiety, quick-tempered, behavioral-limiting fears, specific fears), externalization (negative school attitude, antisocial attitude, behavioral problems, drug abuse, harmful effects of peers, aggression), and interpersonal family problems (being passive in interpersonal relationships, social avoidance, embarrassment, lack of connection with others) [23].

The questionnaire is psychometrically appropriate at the level of clinical diagnosis and subthreshold clinical diagnosis. The Cronbach α for all the scales was above 0.8, which is in line with previous studies [23]. It has also been validated in Iran with the Cronbach α at a proper level. The retest coefficients at all scales are above 0.89 as reported in other studies [27]. In the present study, the Persian version of the MMPI-A-RF questionnaire was provided to the researcher with the permission of the University of Minnesota, and its items were adapted by the institute to the cases of the Persian version of the MMPI-A [22] and the cases. The additions were omitted. No change in the Persian translation of the questions was allowed.

Kiddie schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia

A semi-structured diagnostic interview was designed to acquire information from adolescents, adolescents’ parents, or other custodians. This version of the Kiddie schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia has been revised for the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), and includes dimensional and categorical diagnostic assessments. Trained interviewers provided better clinical images of the symptoms in all diagnostic categories. By employing the interview, the researcher can acquire information about the previous episode (last six months) and the current episode. In this study, information related to the current episode was examined. This semi-structured interview included a screening section and six supplementary sections. The screening section included a preceding interview, the reason for the consultation, the patient’s general data, and the main symptoms of each disorder. When at least one sign is mentioned in the screening section, the supplementary section is executed. “Supplementary section 1” includes depression and bipolar disorders, “supplementary section 2” includes psychotic disorders, and the third section includes anxiety, stress, and obsessive-compulsive disorders. Meanwhile, the fourth section includes destructive behavior disorders and impulse control disorders and the fifth section includes substance use disorders and eating disorders. The sixth section comprises neurodevelopmental disorders [28].

The tool has satisfactory validity and reliability. Francisco et al. reported a Kappa value above 0.7 for interrater reliability in more than half of the disorders [28]. Ghanizadeh et al. reported the reliability of the Persian version at 81.0 and the interobserver reliability at 69.0 based on retesting [29].

Statistical analyses

Mean±SD were calculated for all the MMPI-2-RF validity, higher-order, restructured clinical, and specific problem scales for the CD-only, CD with ADHD comorbidity (CD-ADHD), and other disorders comparison (referred to here as a psychi`atric comparison) groups, and analyses of variance (ANOVA) were used to test for significant differences between groups across scales to determine which scales had different endorsement rates among the three study groups. The Levene test showed that the assumptions of using ANOVA are valid (P>0.001). All MMPI-2-RF variables were within acceptable limits in terms of skewness and kurtosis [30] and most were appropriately normally distributed, indicating that the F test was appropriate. The false discovery rate procedure, with a 0.05% maximum false discovery rate, was implemented to control the familywise error rate associated with multiple comparisons [31]. Effect sizes (partial Eta squared [[Ƞp2]]) for ANOVAs were interpreted as 0.01=small, 0.06=medium, and ≥0.14=large effects. For all ANOVAs with a significant overall effect, Games–Howell post hoc tests were used to examine pairwise differences across groups.

Results

In all the studied samples, 55.9% (n=165) were girls, and 44.1% (n=130) were boys, with a Mean±SD age of 15.9±1.18 years. The majority of the participants, 43.4% (n=128) of the father's education level was a diploma, and 49.2% (n=145) of the mother's education level was a diploma. In the occupational status index, 63.1% (n=186) of the fathers were self-employed, and 72.2% (n=213) of the mothers were housewives.

Additionally, the results of the chi-square test and the ANOVA did not reveal any significant differences among the three studied groups in terms of demographic characteristics (P>0.05).

The Mean±SD scores of the scales of validity, higher-order, and restructured clinical scales of the MMPI-2-RF questionnaire in three groups of adolescents with CD-only, CD-ADHD, and other disorders are shown in Table 2. Only the mean antisocial behavior scale scores in the CD-ADHD disorder group were clinically significant (t≥65).

There was a significant difference between the three studied groups in the three subscales of the combined response inconsistency, infrequent responses, and uncommon virtues of the narrative scale (P<0.001). Accordingly, the mean scores of these subscales were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups compared to other groups of disorders. Moreover, the effect size was low.

There was a considerable difference between the three studied groups only in the behavioral/externalizing dysfunction subscale of the higher-order scale (P<0.001). The mean scores on this subscale were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups compared to the other disorders group. The effect size was moderate. In addition, on this scale, the mean survival time of the CD-only group was greater than that of the CD-ADHD group, but the effect size was slight.

There was a notable distinction between the three studied groups in the four subscales somatic complaints, cynicism, antisocial behavior, and aberrant experiences of the revised clinical scale (P<0.001). Therefore, the mean scores of the antisocial behavior and aberrant experiences subscales in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups were greater than those in the other disorders group. Similarly, the effect sizes ranged from low to high. Furthermore, on the antisocial behavior scale, the mean score in the CD-ADHD group was greater than that in the CD-only group, but the effect size was small.

Furthermore, the mean scores on the cynicism subscale were greater in the CD-ADHD group than in the group with other disorders. On the somatic complaints scale, the mean mortality in the other disorders group was greater than that in the other two groups.

Figure 1 shows the individual high-order scale and revised clinical scale scores for the three groups, namely CD-only, CD+ADHD, and other psychopathology.

The Mean±SD of the specific problem scale scores on the MMPI-2-RF questionnaire in three groups of adolescents with CD-only, CD-ADHD, or other disorders are shown in Table 3. The mean conduct problems and aggressiveness-revised scores were clinically high in the CD-ADHD group (t≥65).

There was a significant difference between the three studied groups in all the somatic/cognitive subscale scores on the specific problem scale (P<0.001). Therefore, the mean scores on these subscales were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups than in the other disorders group. Additionally, the effect sizes ranged from low to high.

There was a significant distinction between the three studied groups based on the helplessness/hopelessness, inefficacy, stress/worry, anger proneness, and behavior-restricting fears subscales of the internalization scale (P<0.001). Therefore, the mean inefficacy, stress/worry, and anger proneness scores in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups were greater than those in the other disorders group. Correspondingly, the effect size was low to medium. Nonetheless, the mean scores of the HLP and BRF subscales in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups were lower than those in the other disorders group. Similarly, the effect size was low to medium.

There was a significant difference between the three studied groups in all subscales of the externalizing scale (P<0.001). Therefore, the mean scores on these subscales were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups than in the other disorders group. Furthermore, the effect sizes ranged from low to high. Additionally, on the SUB subscale, the mean scores of the CD-only group were greater than those of the CD-ADHD group. Furthermore, on the conduct problems subscale, the mean score in the CD-ADHD group was greater than that in the CD-only group, but the effect size was small.

There was a notable difference between the three study groups only in the social avoidance subscale of the interpersonal scale (P<0.001). In this manner, the mean scores on this subscale were greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups than in the group with other disorders. The effect size was small.

There was a significant difference between the three studied groups on all subscales of the personality pathology (except for the introversion/low positive emotionality-revised; P<0.001). Therefore, the mean scores of the three subscales aggressiveness-revised, psychoticism-revised, and disconstraint-revised were significantly greater in the CD-only and CD-ADHD groups than in the other disorders group. Furthermore, for the negative emotionality/neuroticism-revised and aggressiveness-revised subscales, the mean scores of the CD-ADHD group were greater than those of the other disorders group.

Figure 2 shows the scales of specific problems for the following three groups: CD-only, CD+ADHD, and other psychopathologies.

Discussion

This study investigated the clinical characteristics of conduct disorder and its comorbidity with impulsivity-hyperactivity in adolescent clinical samples. The results revealed that adolescents with conduct disorders and adolescents who were infected with CD and ADHD had greater levels of behavioral dysfunction, difficulty in regulating emotions, and problems in performance than those with normative scores on the MMPI-A-RF. This disorder is associated with defects in verbal skills, executive function, and the lack of balance in activation and inhibition systems of behavior [32].

According to the results of previous studies [10، 12، 13، 33، 34], a considerable difference was observed between the CD and CD+ADHD groups and the other psychiatric disorders group in terms of the scores related to externalizing concern. With the structure of the questionnaire, the MMPI-A-RF scales, which were organized hierarchically, move from broad psychopathology structures (high-order scales) to narrowband scales (specific problem scales). At each level of the hierarchy, the CD+ADHD group scored significantly greater than the other mental disorders group did on the scales related to behavioral disorders and aggression (P<0.001).

Moreover, regarding the second hypothesis, the CD+ADHD group was related to more symptoms and greater functional degradation. These results were consistent in some cases, and we observed that the CD+ADHD group had markedly greater scores than did the CD group and other psychiatric disorders according to the RC4 scale, which is associated with antisocial behaviors. Furthermore, a significant difference was observed in the specific problems level on the conduct problems and substance abuse scales, which, in agreement with the background, could predict more severe psychopathology in the CD+ADHD group than in the CD group (P<0.001).

Another significant difference between the CD and CD+ADHD groups was in symptoms related to depression and anxiety (stress/worry, inefficacy, helplessness/hopelessness) due to the high comorbidity of CD with depression symptoms and mixed anxiety symptoms. Depression may indicate subthreshold diagnoses that have caused changes in the process of diagnosis [25، 35]. This issue can double the importance of dimensional investigation of disorders. In the dimensional system, the problem of subthreshold diagnosis has been solved. The hierarchical classification of the psychopathology model is a step in addressing problems related to arbitrary diagnostic boundaries (such as subthreshold cases), which solves the problem of heterogeneity within disorders by constructing dimensions based on observed changes in symptoms and identifying coherent structures of disorders. This model includes both transitional symptoms and persistent incompatible characteristics [36].

The results of the present study indicated that, in the field of problems related to interpersonal relationships, except for the social avoidance scale, there was no significant difference between the three groups on the other scales. A background review revealed that it is crucial to distinguish between behavioral inhibition (such as anxiety and shyness) and social withdrawal associated with delinquency. According to a longitudinal study of a 10- to 12-year-old sample and follow-up data at the age of 13-15 years, behavioral inhibition and not withdrawal are protective factors for the negative prediction of delinquency; on the other hand, withdrawal is considered a risk factor for crime. Boys who were disruptive and withdrawn were three times more likely to commit delinquency and depression. Although the behaviors of individuals with anxiety caused by shyness and social withdrawal are similar, their consequences for behavioral problems can be quite different [6]. However, this topic has been less studied, and additional investigations are needed.

The present study is the first to use the MMPI-A-RF to examine the clinical presentations of CD and its cooccurrence with hyperactivity in a clinical sample. Due to the hierarchical structure of the MMPI-A-RF, it provides helpful information regarding higher levels of pathology, disease symptoms, co-occurrence with other disorders with CD, and changes in the clinical presentations of disorders and functional disorders in areas such as interpersonal functioning.

Conclusion

According to the hierarchical structure of the MMPI-A-RF, if we want to have a view of the personality profile of adolescents with CD in mind, considering the following indicators will greatly improve the results:

1- At the highest level of psychopathology, the behavioral/externalizing dysfunction scale is an accurate indicator for diagnosing behavioral disorders.

2- At the level of the revised clinical scale, antisocial behavior is the main index of the scale for diagnosing conduct disorders, and the greater the elevation of this scale is, the greater the destruction and possibility of cooccurring with ADHD. Meanwhile cynicism and aberrant experiences provide practical information about this disorder in the second step.

3- It is necessary to focus on two points through the specific problems. First, most of the indicators are higher than those of other psychiatric disorders, and second, the two key scales, conduct problems and substance abuse, can distinguish this disorder from other disorders. The cognitive complaints scale is also a suitable index for diagnosing the cooccurrence of conduct disorders with ADHD.

4- Through personality pathology, the three key indicators in the diagnosis of conduct disorder are aggressiveness-revised, psychoticism-revised, and disconstraint-revised. Meanwhile, the intensity of elevation in aggressiveness-revised indicates the possibility of coexistence of these disorders and it increases with ADHD.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in which the difference between these presentations was evaluated in the MMPI-A-RF cohort, and the findings of this study could be useful for differentiating between presentations of conduct disorders using the MMPI-A-RF. Although these differences are evident in a large sample of people, their diagnostic application at the individual level needs much investigation, and clinicians should be careful not to rely too much on increasing the MMPI scale. A-RF or its absence should be cautiously considered when diagnosing specific CD presentations at the individual level.

Study limitations

One of the significant limitations was the lack of split ADHD clusters (hyperactive, attention deficit, and combined type), which can supply more precise information about the CD+ADHD profile. Moreover, we asked whether individuals with attention deficiency had higher scores on cognitive complaints and internalizing scales and whether the combined type of attention deficiency was associated with greater destruction in individuals with behavioral disorders. All these cases are hypotheses that can be the subject of further study.

Another limitation was the lack of control of medication status. The use or nonuse of medication was not taken into account at the time of completing the questionnaire, which could lead to misinterpretation of the relationship between medication status and test results. Finally, the individuals in the conduct disorder group and the conduct disorder group with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder included all clinical cases that met the criteria for these two disorders, and we did not differentiate between primary diagnoses and second and third diagnoses. The manifestations of the symptoms at the primary diagnosis and the second and third diagnoses may be different and can be investigated in a separate study. In conclusion, the use of larger and more homogeneous samples allows this study to be more accurate and comprehensive.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present article was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1400.153). Written consent was obtained from the participants and their parents to participate in the research. All participants freely participated in the research and had the right to withdraw from the research. No fee w:::::::::::as char:::::::::::ged for participating in the research, and the researchers respected the basic principle of information confidentiality.

Funding

The present article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Marzieh Norozpour, approved by Department of Clinical Psychology, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and validation: Marzieh Norozpour and Abbas Porschehbaz; Research: Marzieh Norozpour, Abbas Pourshahbaz, Hamid Poursharifi and Behrouz Dolatshahi; Data analysis: Marzieh Norozpour, Abbas Pourshahbaz and Hamid Poursharifi; Sources: Marzieh Norozpour; Drafting the initial manuscript: Marzieh Norozpour, Abbas Pourshahbaz and Hamid Poursharifi; Review, editing and final approval: All authors; Supervision: Abbas Pourshahbaz and Hamid Poursharifi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank and appreciate all the colleagues who cooperated with the researcher in the introduction

of patients with behavioral disorders to carry out the research.

References

- Noordermeer SD, Luman M, Oosterlaan J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of neuroimaging in oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) taking attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) into account. Neuropsychology Review. 2016; 26(1):44-72. [DOI:10.1007/s11065-015-9315-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zhang R, Aloi J, Bajaj S, Bashford-Largo J, Lukoff J, Schwartz A, et al. Dysfunction in differential reward-punishment responsiveness in conduct disorder relates to severity of callous-unemotional traits but not irritability. Psychological Medicine. 2023; 53(5):1870-80. [DOI:10.1017/S0033291721003500] [PMID] [PMCID]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. Washington: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Link]

- Simonoff E, Elander J, Holmshaw J, Pickles A, Murray R, Rutter M. Predictors of antisocial personality. Continuities from childhood to adult life. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004; 184:118-27. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.184.2.118] [PMID]

- Maughan B, Rowe R, Messer J, Goodman R, Meltzer H. Conduct Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder in a national sample: Developmental epidemiology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2004; 45(3):609-21. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00250.x] [PMID]

- Loeber R, Burke JD, Lahey BB, Winters A, Zera M. Oppositional defiant and conduct disorder: a review of the past 10 years, part I.Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000; 39(12):1468-84. [DOI:10.1097/00004583-200012000-00007] [PMID]

- Erskine HE, Ferrari AJ, Polanczyk GV, Moffitt TE, Murray CJ, Vos T, et al. The global burden of conduct disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 2010. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2014; 55(4):328-36. [DOI:10.1111/jcpp.12186] [PMID]

- Mohammadi MR, Arman S, Khoshhal Dastjerdi J, Salmanian M, Ahmadi N, Ghanizadeh A, et al. Psychological problems in Iranian adolescents: application of the self report form of strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry. 2013; 8(4):152-9. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 1999; 40(1):57-87. [PMID]

- von Polier GG, Vloet TD, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. ADHD and delinquency--A developmental perspective. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2012; 30(2):121-39. [DOI:10.1002/bsl.2005] [PMID]

- Gudjonsson GH, Sigurdsson JF, Sigfusdottir ID, Young S. A national epidemiological study of offending and its relationship with ADHD symptoms and associated risk factors. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2014; 18(1):3-13. [DOI:10.1177/1087054712437584] [PMID]

- Thapar A, Harrington R, McGuffin P. Examining the comorbidity of ADHD-related behaviours and conduct problems using a twin study design. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001; 179:224-9. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.179.3.224] [PMID]

- Abikoff H, Klein RG. Attention-deficit hyperactivity and conduct disorder: Comorbidity and implications for treatment. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992; 60(6):881-92. [DOI:10.1037//0022-006X.60.6.881] [PMID]

- Lynam DR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Loeber R, Stouthamer-Loeber M. Longitudinal evidence that psychopathy scores in early adolescence predict adult psychopathy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 2007; 116(1):155-65. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.116.1.155] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Michonski JD, Sharp C. Revisiting lynam's notion of the "fledgling psychopath": Are HIA-CP children truly psychopathic-like? Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2010; 4:24.[DOI:10.1186/1753-2000-4-24] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Barry CT, Frick PJ, DeShazo TM, McCoy M, Ellis M, Loney BR. The importance of callous-unemotional traits for extending the concept of psychopathy to children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000; 109(2):335-340. [DOI:10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.335] [PMID]

- Rabbani A, Mahmoudi-Gharaei J, Mohammadi MR, Motlagh ME, Mohammad K, Ardalan G, et al. Mental health problems of Iranian female adolescents and its association with pubertal development: A nationwide study. Acta Medica Iranica. 2012; 50(3):169-76. [PMID]

- Archer RP, Newsom CR. Psychological test usage with adolescent clients: survey update. Assessment. 2000; 7(3):227-35. [DOI:10.1177/107319110000700303] [PMID]

- Ben-Porath YS, Tellegen A. MMPI-2-RF: Manual for administration, scoring and interpretation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press; 2008. [Link]

- Ghamkhar Fard Z, Pourshahbaz A, Anderson J, Shakiba S, Mirabzadeh A. Assessing DSM-5 section II personality disorders using the MMPI-2-RF in an Iranian community sample. Assessment. 2022; 29(4):782-805. [DOI:10.1177/1073191121991225] [PMID]

- Valianpour Z, Gharavi M, Mahram MB. [Validation of the minnesota multiphasic personality inventory (MMPI 2) in psychiatric patients and non-patient individuals in Mashhad city (Persian)]. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2020; 22(6):399-407. [DOI:10.22038/jfmh.2020.17815]

- Habibi M, Gharaei B, Ashouri A. [Clinical application of validity and clinical scales of minnesota multiphasic personality inventory-adolescent (MMPI-A): A comparison of profiles for clinical and non-clinical sample and determining a cut point (Persian)]. Journal of Fundamentals of Mental Health. 2013; 15(60):301-11. [DOI:10.22038/jfmh.2013.2286]

- Archer R. Assessing adolescent psychopathology: MMPI-A/MMPI-A-RF. New York: Routledge; 2016. [DOI:10.4324/9781315737010]

- Chakranarayan C, Weed NC, Han K, Skeel RL, Moon K, Kim JH. Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory-adolescent-restructured form (MMPI-A-RF) characteristics of ADHD in a Korean psychiatric sample. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2022; 78(5):913-25. [DOI:10.1002/jclp.23269] [PMID]

- Archer RP, Krishnamurthy R. MMPI-A and rorschach indices related to depression and conduct disorder: An evaluation of the incremental validity hypothesis. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1997; 69(3):517-33.[DOI:10.1207/s15327752jpa6903_7] [PMID]

- Sharf AJ, Rogers R. Validation of the MMPI-A-RF for youth with mental health needs: A systematic examination of clinical correlates and construct validity. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2020; 42(3):527-38. [DOI:10.1007/s10862-019-09754-x]

- Taziki A, Kamkar K. MMPI-ARF Standardization of reconstructed form of Minnesota multidimensional Personality Inventory in guidance school students in Aq Qala city. Psychometry. 2016; 4(16):1-7. [Link]

- de la Peña FR, Rosetti MF, Rodríguez-Delgado A, Villavicencio LR, Palacio JD, Montiel C, et al. Construct validity and parent-child agreement of the six new or modified disorders included in the Spanish version of the kiddie schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia present and lifetime version DSM-5 (K-SADS-PL-5). Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2018; 101:28-33. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.02.029] [PMID]

- Ghanizadeh A. ADHD, bruxism and psychiatric disorders: does bruxism increase the chance of a comorbid psychiatric disorder in children with ADHD and their parents? Sleep & Breathing. 2008; 12(4):375-80. [DOI:10.1007/s11325-008-0183-9] [PMID]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York: Guilford Publications; 2016. [Link]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. 1995; 57(1):289-300. [DOI:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x]

- Hill J. Biological, psychological and social processes in the conduct disorders. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2002; 43(1):133-64. [DOI:10.1111/1469-7610.00007] [PMID]

- Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991; 148(5):564-77. [DOI:10.1176/ajp.148.5.564] [PMID]

- Wickens CM, Kao A, Ialomiteanu AR, Dubrovskaya K, Kenney C, Vingilis E, et al. Conduct disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as risk factors for prescription opioid use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2020; 213:108103. [DOI:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108103] [PMID]

- Herkov MJ, Myers WC. MMPI profiles of depressed adolescents with and without conduct disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1996; 52(6):705-10. [DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199611)52:63.0.CO;2-Q]

- Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D. A paradigm shift in psychiatric classification: The hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology (HiTOP). World Psychiatry. 2018; 17(1):24-5. [DOI:10.1002/wps.20478] [PMID] [PMCID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Clinical Psycology

Received: 23/07/2023 | Accepted: 14/10/2023 | Published: 21/06/2024

Received: 23/07/2023 | Accepted: 14/10/2023 | Published: 21/06/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |