Volume 25, Issue 1 (Spring 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(1): 72-99 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mardani M, Alipour F, Rafiey H, Fallahi-Khoshknab M, Arshi M. Mothers’ Experiences of Living With Children With Substance Abuse Issues: Overcoming Challenges on the Road to Rehabilitation. jrehab 2024; 25 (1) :72-99

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3318-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3318-en.html

1- Department of Social Work, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences

2- Department of Social Work, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,barbodalipour@gmail.com

3- Social Welfare Management Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences

4- Department of Nursing, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences

2- Department of Social Work, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Social Welfare Management Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences

4- Department of Nursing, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences

Full-Text [PDF 2349 kb]

(902 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2872 Views)

Full-Text: (1261 Views)

Introduction

Drug abuse is a global issue that extends beyond the boundaries of any specific country. According to an estimate by the United Nations drugs control program (UNDCP) in 2020, 5.6% of the world’s population was involved in substance abuse [1]. Iran, given its unique geographical location, is not exempt from this crisis and has witnessed an upward trend in the utilization of various narcotics [2]. It is important to emphasize that problematic substance use encompasses more than just frequent narcotics or alcohol consumption. It also includes the challenges individuals and their families face and the subsequent adverse consequences [3, 4, 5, 6]. While much attention has been directed toward the affected individuals in addiction studies and interventions, there is a gap in the impact of addiction on other individuals, particularly the families and primary caregivers.

Regarding the rising challenges and consequences of drug and alcohol abuse for addiction-affected family members (including spouses, children, parents, siblings, and relatives), it is now more evident that these groups require keener focus and consideration [7, 8, 9]. Generally, these individuals are profoundly impacted by the substance abuse of one or more family members, experiencing various health-related issues at different levels [6, 9, 10, 11]. Not only do addiction-affected family members have to deal with multiple problems related to supporting the addicted person [4, 5, 12], but they also spend significant effort in mitigating the problems arising from addiction within the family, such as instances of violence, arguments, and disputes [8]. Although studies have provided valuable insights into the personal experiences of individuals grappling with addiction, a substantial gap still exists in the current literature when it comes to exploring the specific challenges, dynamics, and coping mechanisms within families affected by addiction [13, 14]. In other words, such studies overlook the other side of addiction, which is addiction-affected families [15].

It is noteworthy that among the family members, parents experience the most profound level of involvement with the problem [16, 17] and endure immense mental [18, 19] and emotional pressure [16, 17, 19, 20]. This pressure arises from various factors, including financial stress, family conflicts, struggles with their children, and so on [18-21]. Given the pivotal role parents assume within the family dynamic, mothers, in particular, involve themselves more than any other family member in addressing their child’s problem, seeking solutions to cut them from the grip of addiction.

Groenewald revealed that mothers of children struggling with substance abuse experience a range of distressing emotions, including emotional distress, desperate cries for help, and thoughts of suicide [22]. Additionally, other unpleasant experiences, such as constant worry, persistent anxiety, feelings of shame and fear towards their child, family conflicts, severe financial problems, and a sense of hopelessness and guilt, have been stated by addiction-affected mothers [23]. Furthermore, studies have documented additional experiences, including feelings of mistrust and betrayal, as well as occasions where mothers felt compelled to leave their homes due to fear of their teenager’s unusual behaviors [19-21]. While addiction has been associated with detrimental effects on families in different countries, the diverse array of consequences that addiction can have within various cultural contexts should not be overlooked [24]. Although some quantitative studies have evaluated the effects of addiction on families and parents, qualitative studies in this field are very limited [25-30]. There is a pressing need for designing various studies to explore the experiences of addiction-affected mothers (AAMs) within diverse cultural settings. Qualitative studies hold immense potential to explore deep and new experiences, which can, in turn, enhance the generalizability of findings and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter [31]. Furthermore, gaining a deeper understanding of issues in this field can help deliver the best possible services to AAMs as they navigate the complexities associated with their children’s addiction. Despite the existence of numerous studies in this area, rehabilitation service providers still face a gap concerning the experiences of parents, especially mothers, as the most involved family members [32].

Examining maternal experiences has predominantly originated from the distinctive care giving role assumed by mothers within both Iranian and global cultures. In these contexts, mothers are responsible for caring for their children, primarily monitoring their children’s health and considering their wellbeing as an ultimate duty [19, 33-35]. Notably, studies investigating the experiences of parents affected by addiction, specifically in relation to their children’s substance abuse, consistently report fathers’ low participation rate. Consequently, women, particularly mothers, constitute the primary participants in such research endeavors [23]. Given the circumstances mentioned above, there exists a compelling need for further research within the realm of mothers affected by child addiction. Such research instills a paradigm shift in therapeutic approaches and theoretical frameworks. Through the execution of comprehensive and meticulous investigations, a profound understanding of this complex phenomenon can be achieved. This collective understanding has the potential to alter prevailing perspectives and facilitate advancements in the field.

Furthermore, a solid foundation can be established for future treatment modalities by discerning the positive facets of maternal experiences and highlighting their practical efforts and strategies in the recovery process. Consequently, this study endeavors to explore the experiences of Iranian mothers affected by their child’s addiction, recognizing the challenges encountered in managing a child with substance abuse. The qualitative nature of this study, relying on an interview-based approach, is essential for capturing the nuanced dimensions of maternal experiences in this context.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This study used the phenomenological method to delve deeply into the experiences of AAMs. The fundamental principle of phenomenology states that each individual’s encounter with a particular phenomenon is unique, and different individuals may have distinct experiences of the same phenomenon [36]. Bracketing, assessing, and understanding the nature of the phenomenon are the three key steps researchers need to consider when trying to understand a phenomenon [37]. In the present study, data collection and analysis were conducted using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), which provides a deep understanding of the phenomenon and integrates phenomenological and hermeneutic principles. In general, the IPA method can be a suitable and effective strategy when researchers want to understand a process or its changes or problems that have received little attention or are new and complex. This method considers social, historical, contextual, and situational factors to understand the phenomenon better [38].

Study participants

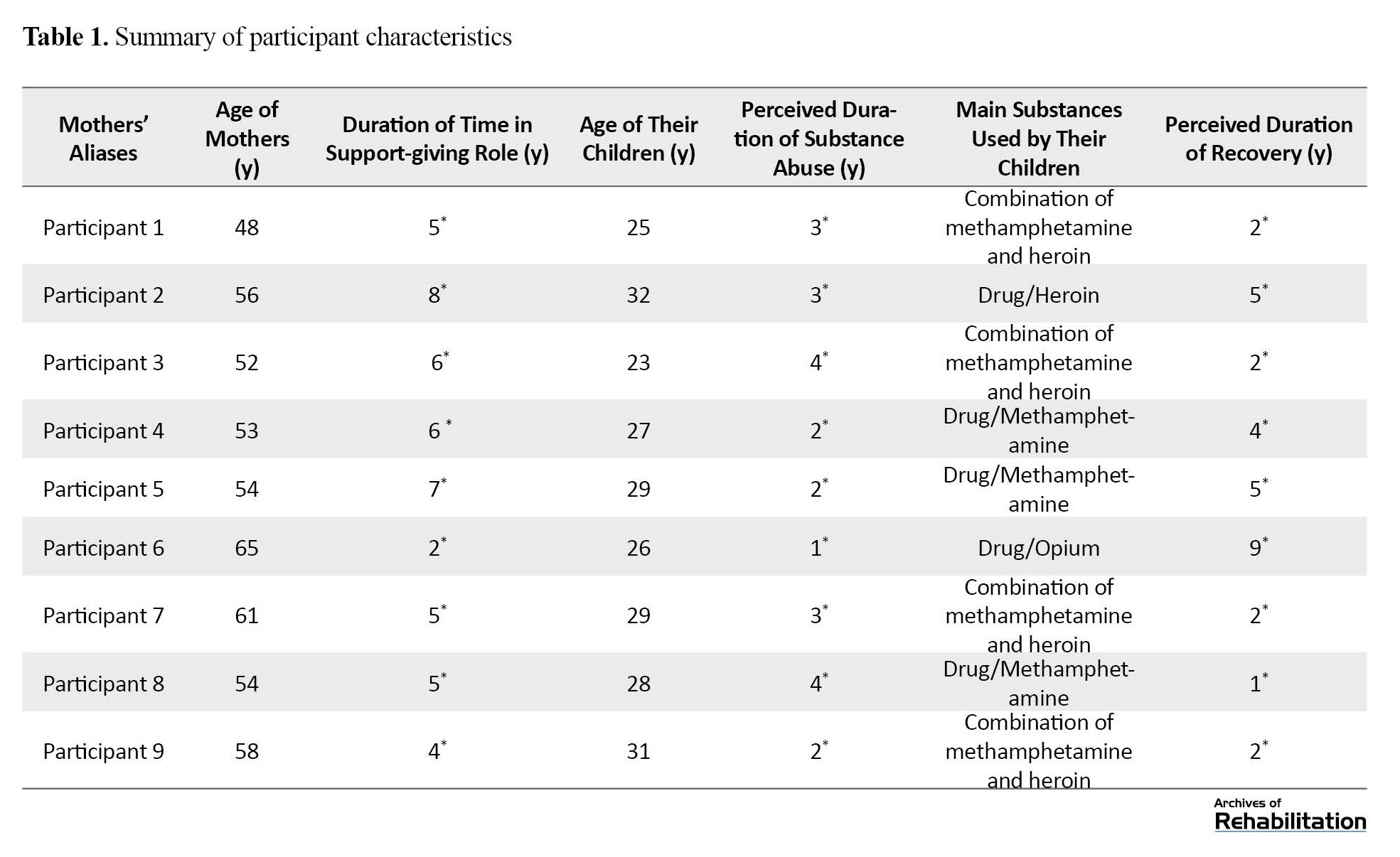

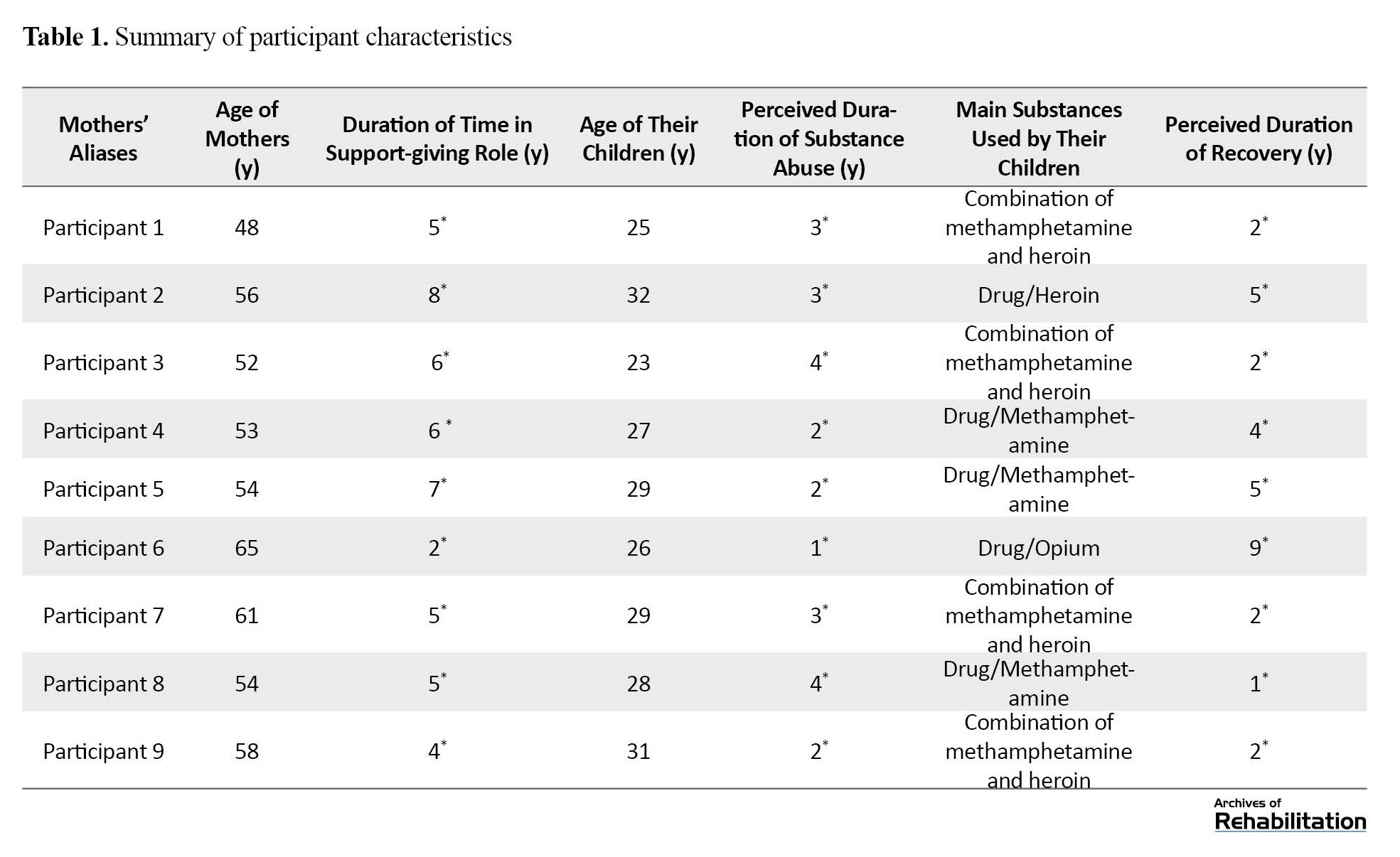

In this study, 9 mothers affected by addiction, whose children were not involved in addiction at the time of the research and had completed the stages of recovery, were included in the study using the purposeful sampling technique. In qualitative research, the sample size is between 6 and 10 people, but this amount can be increased if information saturation has not been achieved [39]. This study involved 9 mothers affected by their children’s addiction, who, at the time of the study, were actively engaging in educational and support sessions following their children’s recovery (Table 1).

The average age of these individuals was 50 years, and they had been serving in their supportive role for consumers for at least three years. All participants resided in the urban setting of Tehran City, Iran, and the predominant substances used by their children were methamphetamine, heroin, and opium. All participants in the current study were mothers who, following their child’s recovery, actively endeavored to mitigate the challenges associated with their child’s addiction.

Additionally, they dealt with residual issues arising post-recovery. Over at least one year, these mothers participated in specialized training and support sessions facilitated by the Rebirth Charity Organization in Tehran, Iran. The Rebirth Charity Training Unit was pivotal in disseminating information to mothers. Following the inclusion criteria of the present study, this unit provided contact information for the participating mothers to the researchers.

Moreover, with a commitment to safeguarding confidentiality in handling information and interviews, all participants were assured that only the researcher would have access to their information. In addition, confidentiality principles were followed, and participants were assured of their privacy. Detailed explanations of the study’s protocols were provided to them, accompanied by their written informed consent. The inclusion criteria consisted of mothers who had experience of caring for children with substance abuse issues, and mothers whose children had entered the recovery period during the study (this refers to the process through which individuals transition from the challenges of drug use to a life-free from substance abuse, ultimately becoming integral contributors to society) [40, 41], absence of other family members with addiction issues, and mothers actively seek psychological and social support. In this current study, we focused on mothers who had reached the conclusion of their children’s journey through addiction and had gained a comprehensive understanding of the various challenges and issues associated with addiction, persisting even after their children’s recovery. This selection aimed to capture profound and valuable experiences that these mothers had acquired throughout this process, providing insights for researchers and the broader public. The decision to emphasize mothers who dealt with the aftermath of addiction stems from the crucial need to address the lingering issues of post-recovery. It is noteworthy that a prevalent public opinion assumes that once an individual’s addiction concludes, all related problems cease to exist. However, our study acknowledges and explores the often-overlooked complexity of these lingering challenges.

Data collection

Notes and recorded audio were employed as additional data collection tools alongside interviews. The interview guide followed the study’s objectives and existing literature to explore the experiences of AAMs (Table 2).

To ensure clarity, any misunderstood questions were explained in detail, and the research team maintained a non-judgmental and unbiased stance during interviews. Qualitative research relies on audio recordings, observations, and interviews to gather data without quantifying information. Thus, this study incorporated field notes and observations to capture non-verbal responses, the interview atmosphere, and participants’ behavioral expressions. Before interviews, a session was conducted to thoroughly explain the study’s objectives and establish clear expectations for participation. It is worth noting that all interviews were conducted at the central office of the Rebirth Charity from September 2022 to March 2023 to explore participants’ experiences through individual, semi-structured, and face-to-face interactions. The interviews took 60 to 100 minutes, with each participant being interviewed only once. Interviews concluded once the necessary information was obtained to fulfill the research objectives and data saturation was reached. The potential risk of compromising data quality due to the researcher’s prior interaction with participants (during a meeting to explain the research protocol) was attentively addressed throughout the study. At the end of the interviews, gratitude was expressed to participating mothers for their contributions, and they were informed of the availability of a summary of the findings should they express interest.

Data analysis

The data analysis process within the IPA method encompasses several steps [42]. Initially, the interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the resulting transcripts underwent extensive scrutiny to conduct a thorough textual analysis, thereby facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ experiences. The primary objective of this phase was to capture the mothers’ narratives and assimilate their non-verbal information to establish relevant themes. Furthermore, each transcript was precisely reexamined several times to develop the main category and subcategories. The data analysis followed an inductive approach, where efforts were made to avoid any unexplained missing data. Each authentic participant’s expression was regarded as a distinct code to maintain impartiality and prevent personal bias from influencing the data [43, 44]. These codes were subsequently organized into temporary themes and their corresponding subthemes. A meticulous process of clustering and merging was employed to unveil the interconnections between the identified themes. This process enabled a higher level of data extraction through focused and precise analysis [38]. This iterative and inductive process persisted until data saturation was achieved [36]. It is noteworthy that in this study, the path of the semantic analytic level was from data description in the results section to data interpretation in the discussion section. Regarding the continuous connection between the researcher and the participants during the study, all stages of data coding and analysis were undertaken by a single researcher to ensure methodological rigor and coherence [45].

Reflexivity

The study utilized the interpretive IPA method to understand AAMs’ experiences deeply. In this study, to reduce and minimize the effects of the researcher and the effects of her experiences, values, previous assumptions, and priorities on the research process [46-48], self-awareness, self-questioning, and rethinking have always been of interest to researchers [47-49]. Furthermore, reliability and validation criteria were employed to enhance accuracy throughout the study, involving an analyst appointed to conduct the analysis [50]. Moreover, validity was ensured in this study through meticulous participant selection aligned with the sampling criteria, emphasizing maximum diversity. This measure involved multiple meetings to establish a consensus on various coding aspects and theme identification. The participants played an active role in summarizing and reviewing interviews. Additionally, scrutiny of data and codes by the research team and professors contributed to the robustness of the study. The researchers also expressed keen interest in incorporating field notes and reminders alongside the semi-structured interview format.

Results

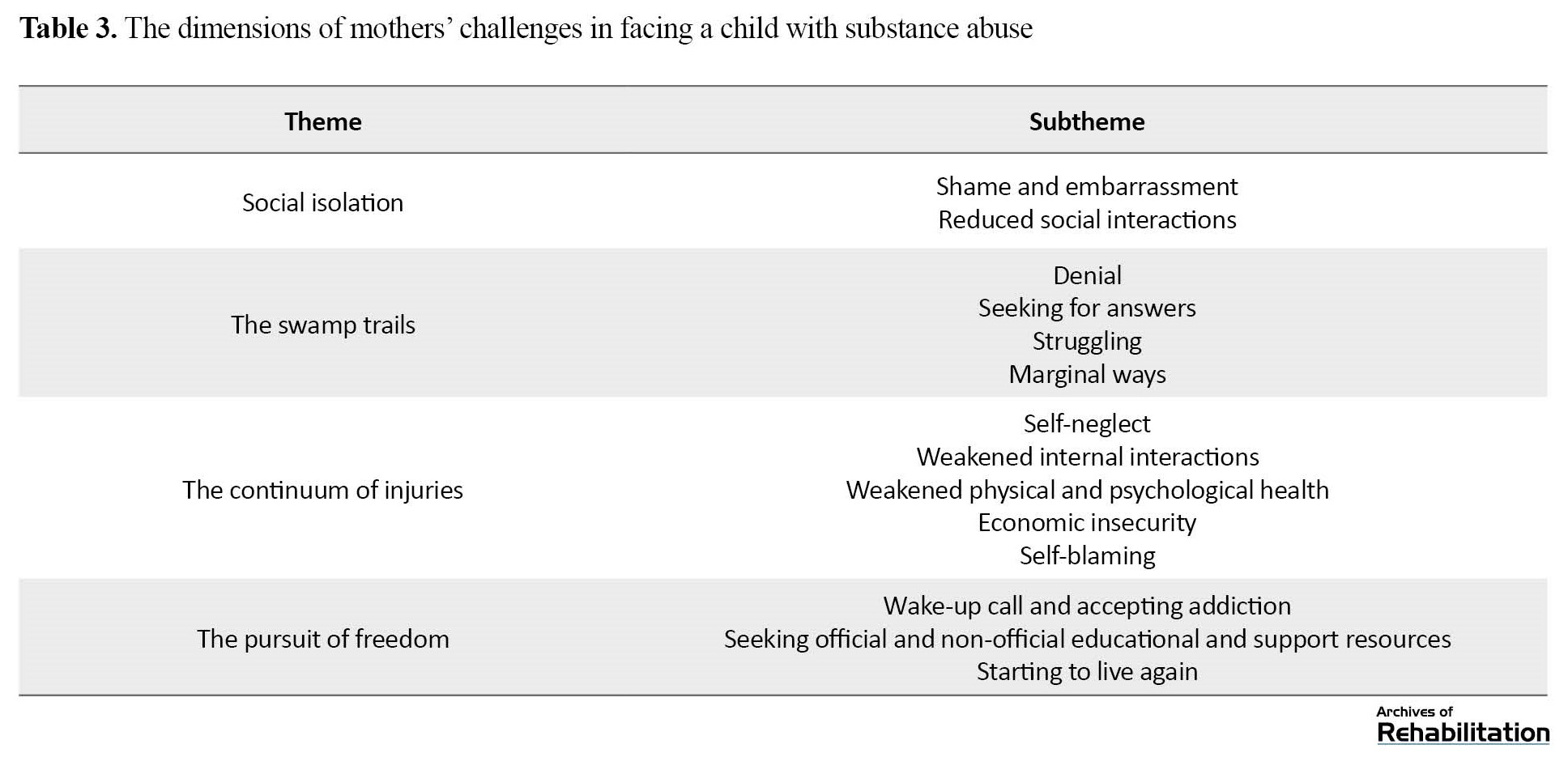

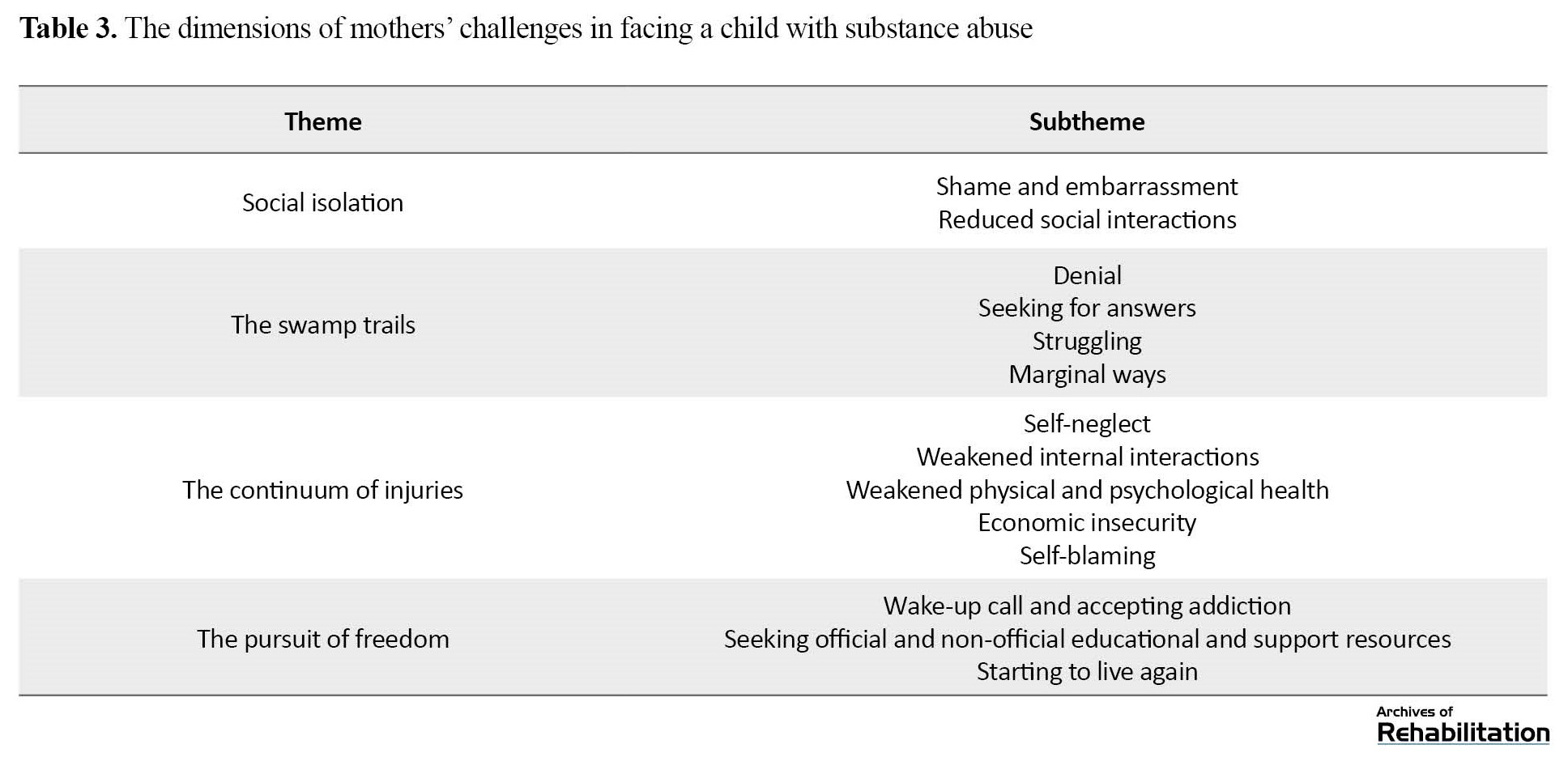

Nine AAMs with the experience of caring for a child with substance abuse issues participated in this study (Table 1). The average age of the mothers was 50 years, and they all had at least three years of supporting their affected children. All participants resided in the city (Tehran City, Iran), and the most common substances used by their children were glass, heroin, and opium. The data analysis and the codes extracted from the interviews revealed four main themes (social isolation, the swamp trails, the continuum of injuries, and the pursuit of freedom) and 14 subthemes (Table 3).

One of the topics mentioned more than anything else in this study was the initial struggle faced by mothers in responding to the problem, a concept referred to as running on a treadmill, ending up in a continuum of problems for mothers. The first three themes reflect the experiences that mothers went through when dealing with their children’s substance abuse. In contrast, the fourth theme indicates the measures mothers employ to counteract the situation.

Theme 1: Social isolation

After discovering their children’s addiction problem, all AAMs, in some way, went through a social isolation episode driven by their desire to avoid social labels, stigma, and judgment from others. The “shame and embarrassment” and “reduced social interactions” are the subthemes that emerged from this main theme.

Shame and embarrassment

Most mothers admitted in their interviews that one of their unpleasant experiences was the feeling of shame and embarrassment in relation to their child’s addiction and its visible impact on their behavior and appearance.

“When we lived in an apartment, I would quickly close our door whenever a neighbor entered the building because I didn’t want to see them at all. I felt that if they saw me, they might say, ‘She’s the mother of the boy who uses drugs.’ It was becoming really difficult for me, which is why I always told my husband that I didn’t want our son to come with us as long as he was struggling with addiction” (Participant (P) No. 1).

“When he crossed the line in a way that his face and appearance clearly turned unusual, it became evident that my child did not have the mood to groom himself. That’s when I realized that he had been using drugs and had become a drug addict. Since then, I have told my husband that we shouldn’t allow anyone to see him or go out with him anymore” (P No. 6).

Reduced social interactions

Mothers dealing with shame and embarrassment felt compelled to hide from the judgmental gaze of others, resulting in reduced social interactions. The fear of being judged by others and people’s strong guard against addiction were among the most important issues addressed by mothers with regard to their social isolation.

“As soon as my child became addicted, people immediately started judging me, claiming it was my fault and that I was the reason for this situation; everyone said that I was responsible and should be condemned. I was always blamed by others, from my family to my husband; they all insisted that I was the one to blame” (P No. 8).

“Because of the fear of being judged by others, it feels as if your voice is silenced; you want to cry out loud, but it seems that your roar is always silenced. I always wanted to scream and shout to stop him, but I was afraid of neighbors’ judgment, and the fear of being blamed and humiliated held me back. As a matter of fact, I felt all these things; one cannot ignore people’s looks; it was always there, I saw it, I felt it, and that is why I decided to stay away from them”(P No. 1).

“Even when you attempt to confide in someone, they mistreat you or say words that even hurt you more. Well, in such a situation, one has to keep a distance from these people” (P No. 7).

“My whole family members were educated, but they did not even have a single clue in their minds about this disease; I could not talk to them at all; they had a very strong guard against this problem” (P No. 8).

Participants acknowledged the complex circumstances they had to navigate in every interaction, considering the appearance and behavior of their child, their own mental condition, the timing of their child’s drug consumption, etc. This led them to withdraw from social engagements, seeking to minimize judgment and labels from others as much as possible.

“When this problem happened to my child, I decided not to go anywhere. I was all by myself and kept a far distance from everyone to avoid hearing their words, but they would talk anyway indirectly. Maybe they did not mean me, but I took it to myself. I tried to avoid any form of communication with others (P No. 3).

“In reality, there were many things before that no longer exist after the addiction. For example, the simple and peaceful interactions I once had with others are now a thing of the past, and I don’t foresee them returning. If I wanted to communicate with the closest people to me, I would be limited by time constraints. I always have to consider my child’s condition and his consumption time. Our relationships, the feeling that you want to have in society, walking proudly with your own child, all would vanish because you have to terminate all relationships with others, even the closest people to you, like your own sister or colleague. I even had to quit my job” (P No. 7).

Theme 2: The swamp trails

Initially, AAMs resisted seeking official and unofficial support or engaging with specialized institutions to avoid exposing their child’s addiction problem to others. Instead, they adopted several self-recommendation measures, leading them into challenges, such as denial, seeking answers, struggling, and marginal ways, which were like a swamp or the Bermuda Triangle for them.

Denial

“I could not accept it at all; I thought that no one in our family used drugs; I believed our entire family was clean, and I could not accept that my kid could be addicted to drugs (P No. 2).

“My husband always told me nothing was wrong; perhaps we were resentful, and he wanted to calm us down. He always convinced me that there was nothing to worry about; nothing would happen. This drug is not for him; it belongs to his friends. He blamed his friends for influencing our child” (P No. 4).

Seeking answers

Most mothers in this study emphasized the significance of understanding why their children fell into addiction, and they started searching to find a solution to their child’s addiction through various ways and countermeasures. Experiencing a state of ambiguity and uncertainty, self-prescribed treatments, impulsive actions, and making decisions without consulting others were among the reactions mentioned by most of the mothers in this context.

“After my child’s addiction, I fell into the path of searching for people to ask them where to go; some suggested I visit the Esteghlal Park to identify the substances my child was consuming, to understand what I saw in his hand” (P No. 1).

“My first mistake was that I attempted to administer the treatment myself; my child was not mentally and physically ready to accept the treatment, but I forced him to go for the treatment. I made a mistake; I thought the best solution was to compel him to go to a rehabilitation camp” (P No. 8).

“You may not believe it, but I sold all my furniture and all I had in my life except for my house; I sold everything, and I changed my city. To avoid being alone, I took one of my relatives with me, rented her a house, and spent a lot of money on her. I thought this would help us a lot. I made all the decisions alone, convinced that I was making the right choices” (P No. 7.)

Struggling

AAMs consistently perceived self-suppression, attempts to compensate for the repercussions of addiction, aimless wandering, and co-dependency as recurring struggles. They admitted that they would grab on anything desperately to find a way out of their problems.

“I have always likened this process to an unwanted swamp sinking both me and his father; my child is outside the swamp; the harder we struggle to reach him, the deeper we sink. That’s exactly how it felt”(P No. 1). She added, “Many mothers, like myself, find themselves in the same position; we do not know what to do, which makes us try every devious way to gain understanding.”

Marginal ways

This subtheme is closely related to the concept of “mothers’ struggling.” Somehow, mothers have tried to control the situation through marginal ways and complementary actions, such as restricting and controlling the child, planning for the child’s life, providing inappropriate support, implementing financial sanctions, or rejecting the child. However, these actions only exacerbated their problems.

“I finally decided to talk to my child, telling him not to go out with his friends and offering other pieces of advice. These friends are not beneficial to you. I was trying to control him emotionally. I even would chase after him. If he did not return home at night, I would force his father to go to his friends’ houses, no matter if it was 1:00 AM. In a way, I was always present at their gatherings from a distance”(P No. 9).

“I told my son that I would not give him a single rial (Iran’s currency) and would not support him anymore, telling him: If you want to leave, do not come back at all; if you still want to take drugs, do not come home anymore; even if you come again, I won’t open the door”, (P No. 5).

Theme 3: The continuum of injuries

Within the support process, various subthemes emerged from the data, highlighting the sequential problems and harms experienced by mothers. These subthemes included self-neglect, weakened internal interactions, weakened physical, mental, and psychological health, economic insecurity, and self-blaming.

Self-neglect

Mothers’ involvement in their child’s addiction often resulted in neglecting their wellbeing above all else. In other words, they would disregard their daily affairs and health concerns, creating many problems for themselves both during the child’s addiction and after recovery.

“I completely forgot that I also needed to take care of myself as well, that I needed to remain healthy, that I could use the opportunities when my child would come along with me. But I could not deliver it at all; I was so mentally and physically engaged with this issue that I completely neglected myself and my own needs. It was the same for my health; I would not go to a doctor at all, even when I felt sick”(P No. 1).

Weakened internal interactions

A common issue mentioned by all mothers in the study was their neglect of other family members due to constant attention to the affected member. In a way, mothers prioritized providing financial, psychological, and emotional support to their affected child, resulting in detachment among family members. This detachment manifested in extreme marital disputes, thinking of divorce, and the propagation of the problem to other members, especially other children.

“During that time, my attention shifted away from my daughter. I neglected her, and this was tormenting for me. My daughter was mentally traumatized because she was constantly exposed to the stress and deterioration caused by her brother and me. This was bothering her, not knowing where her brother was. For example, several times when Amir overdosed, she was distressed witnessing a family member’s illness, but she did not receive my attention” (P No. 8).

“When addiction entered our family, I felt hatred toward my husband and really wanted to divorce him. I believed that separating from him would improve my situation. I assumed the reason for all these problems was my husband, so I should leave him”(P No. 9).

Weakened physical and psychological health

During the initial phases of this problem, AAMs encountered various challenges that affected their physical and psychological wellbeing. These challenges included life losing its vibrancy, reaching a dead end, desperation and helplessness, depression, suicidal thoughts, facing mental and psychological pressure, constant comparison of their lives with others, engaging in repetitive and intrusive thinking, developing various physical ailments, and physical exhaustion.

“I felt like I was not living at all; I was a crazy and confused person who just opened her eyes in the morning, grabbed a cup of tea, and just thinking what I could do today. Everything seemed devoid of color and meaning to me”(P No. 1).

“When you look around and see children of the same age in the relatives, observing their achievements, and thinking about where your child should have been, but instead realizing where he or she actually is. These thoughts and comparisons are truly devastating” (P No. 7).

“Because of the pressure I endured, I developed early menopause and had to take medications for a long time, I extracted a lot of my teeth, I got diabetes, and the doctor said that my diabetes was neurological”(P No. 3).

Economic insecurity

Under this theme, mothers addressed the financial problems caused by the high costs of addiction treatment and their inability to afford medical and therapeutic expenses. They also mentioned financial drawbacks caused by a decline in the family’s financial acumen, resorting to loans, and experiencing financial and occupational setbacks.

“Despite the fact that my husband and my son were financial partners, their company collapsed because of my son’s addiction. We had to sell the equipment and officially announce the company’s closure because it was detrimental to our child’s wellbeing, but it was also causing significant financial harm” (P No. 4).

“My child’s addiction drained our entire savings and livelihood; we even spent my husband’s retirement funds and became completely out of money. We faced severe hardships, having to sell two cars. Even when I wanted to get an MRI, I couldn’t afford it” (P No. 5).

Self-blaming

This concept is closely related to “the search for reasons” for mothers, but according to the mothers’ statements, this concept emerges after a period of realizing their child’s addiction. As mothers navigate through various circumstances, they eventually turn inward and begin to blame themselves (self-blaming and self-destruction), searching for the root of the problem within themselves.

“When my child was using drugs, I deprived myself of any right to live; I used to judge and curse myself, saying that it was my abandonment of my child that caused these problems; I would self-destruct and experience inner devastation”(P No. 5).

Theme 4: The pursuit of freedom

In response to the various consequences of addiction, many mothers adopted several measures to cope and adjust. These measures appeared gradually in mothers’ lives and became apparent under three subthemes: Wake-up call and accepting addiction, seeking official and unofficial educational and support resources, and starting to live again. Most mothers emphasized that this theme extended beyond the addiction period and remained relevant even during their child’s recovery phase, signifying an ongoing engagement with these concepts. In other words, these mothers would have to live under the theme of “the pursuit of freedom.”

Wake-up call and accepting addiction

Accepting the problem was one of the most important factors that all the participants acknowledged its role as a driving force for exiting the crisis. This concept enabled mothers to confront numerous issues associated with addiction and accept the fact that addiction cannot be eradicated instantaneously. Themes such as “passing through the fog” and “rising like a phoenix” emerged as perceptions among these mothers only after answering the wake-up calls.

“Step by step, others awakened me that you cannot do anything: Chasing, beating, locking the door would yield no fruitful results. At some point, I came to the conclusion that my child might perish here, and I asked myself, “What would I do then? Would I let myself perish, too? Or die? It was at that moment I stopped myself”(P No. 1).

“After a while, you find yourself going down a road and then returning to the first place, taking your child to rehabilitation camps and doing anything to save him; all seem to be futile. It is then that you are taken aback, realizing the futility of these efforts and the need to think about yourself as well and prioritize your own wellbeing” (P No. 9).

Additionally, accepting the addiction and the person (as it is) was found to play an essential role in mothers’ progression beyond the continuum of problems. Under this concept, mothers tried to support their children positively.

“I finally told my son that it was not important if he wanted to continue taking drugs, and I assured him that he could always turn to me whenever he felt tired, and I would support him in every possible way. I did my best and tried everything for him; enough was enough! I said, “Go and consume it, and whenever you feel tired, return to me. I am here for you all the way”(P No. 3).

Seeking official and non-official educational and support resources

The acceptance of addiction assists mothers to ultimately overcome the fear of social stigma and being in society, thus propelling them to seek both official and unofficial support. By acquiring knowledge in the field of addiction, they aim to mitigate its impact by implementing effective countermeasures. An important aspect emphasized by all mothers was the necessity of continuous learning even after their child’s recovery.

“If it was not for the experiences of the Naranan [group sessions of anonymous addicts’ families] sessions, the three of us (me, my husband, and my child) would probably be dead or met an unfortunate end by now. I owe my current situation to the abilities that I gained in the Naranan sessions” (P No. 7).

“In the training classes, we somehow became aware of how we should behave; because of that, a class was held. I made sure to participate not to fix my child but to seek answers to the question of why this happened to my family and me. Through these classes, I realized that I should not be asking why it happened to me because any family can be a victim of addiction” (P No. 2).

Starting to live again

All AAMs in this study expressed that initiating a new life independent of the drug-addicted individual was one of the effective measures to alleviate the impact of their child’s addiction. Setting free the child, continuing life without them, rediscovering oneself, returning home, and fostering internal healing within the family were among the concepts mentioned by the participants.

“I turned into a person who managed to sleep and avoid bothering myself, even when my child did not come home at night, and I was really worried as a mother. I managed to sleep, continue to do my daily routines, prepare meals for myself, and eat” (P No. 3).

“At some point, I told myself: Your father and your mother are no longer with you, your child is gone, your 3-membered family is shattered, and now you wish to lose the remaining member too? Return to your own life”(P No. 1).

“After all the ups and downs, I finally realized how effective it was to release a child and acknowledged the necessity of doing so. I witnessed, when I let my child be free, how successful he became; he was allowed to decide for his life by himself, and I could once again live my own life”(P No. 4).

Discussion

The present phenomenological study provides a deep insight into the experiences of AAMs, specifically focusing on their supportive role in relation to their children’s substance abuse both during and after recovery. Overall, four main themes and 14 subthemes were extracted from the data. The three primary themes, namely “social isolation”, “the swamp trails”, and “the continuum of injuries”, reflected the experiences encountered by these mothers in the context of their children’s substance abuse. The fourth theme, “the pursuit of freedom”, addressed the coping measures employed by the mothers to deal with the situation, with participants acknowledging that these strategies would continue to have an impact even after their child’s recovery. As primary caregivers responsible for their children’s wellbeing and health, mothers are often the first to confront and initiate protective measures for their children’s addiction.

Regarding the stigmatized nature of addiction in society, AAMs feel ashamed and attempt to keep a distance from society and those around them. Not only does addiction affect mothers but also all family members, causing significant disruption, detachment from the social world, and reduced engagement in society. In addition, many families will face challenges when trying to ask for help as they tend to conceal their child’s addiction, limiting their communication with others and presenting significant hurdles in accessing support [51, 52]. The study also explored the coping strategies employed by mothers in dealing with their children’s addiction and, in this regard, utilized a diverse range of actions, including denial, the search for reasons, struggling, and exploring marginal ways. A child’s addiction is an incredibly distressing and traumatic experience that compels family members, particularly parents, to resort to defensive reactions such as denial and avoiding accepting the problem [17, 53]. Then, parents seek logical explanations and attempt to identify the underlying causes of the issue within the family, aiming to find a rational solution [18, 52]. Another issue mentioned by AAMs was the occurrence of problems in the form of dominoes, affecting their lives even after the child’s recovery. One notable issue was the intense pressure placed on mothers due to intra-familial disintegration. Family relationships suffer greatly as a result of a child’s addiction, leading to a wide array of conflicts, including parental and marital disputes [34, 54, 55], the breakdown of interpersonal relationships at home [17, 25, 53, 56, 57], chaos and failure in familial communication, familial conflicts [33], and neglect and inattention towards other children [53, 58]. The development of various health-related problems in AAMs was one of the subthemes extracted from the data. Feelings of hopelessness, mistrust, distress, emotional exhaustion, and helplessness permeate their lives [20, 22, 34, 58-61], accompanied by heightened stress, pressure, and an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and attempts [22, 53, 62]. Additionally, these families struggle with numerous physical disorders and ailments, as reported in other studies examining the impact of addiction on affected families [17, 53, 61 , 63]. It is worth noting that families in this situation encounter serious financial hardships, sometimes leading to financial collapse [17, 51, 55, 62, 64]. AAMs admitted that in order to deal with such problems and reduce the impacts of addiction, they adopted coping strategies, including accepting addiction, obtaining resources, and starting a new life. Attracting moral, financial, informational, and social support is one of the coping strategies against this situation, with families utilizing support networks, accessing information, and engaging in therapeutic interventions as prevalent methods to confront addiction [17, 21, 34, 51, 53, 58]. In general, this study provides valuable insights into the experiences of mothers affected by addiction and their supportive roles throughout their children’s substance abuse journey. The findings underscore the profound impact of addiction on various aspects of these mothers’ lives, from social isolation and familial disintegration to physical and psychological health challenges. The study highlights the importance of comprehensive support systems, resources, and coping strategies to address the multifaceted needs of addiction-affected families.

Conclusion

Although various research has been conducted to investigate the experiences of families affected by addiction in multiple countries, the rate of addiction in Iran is high, and every year, a significant number of families enter this process. So far, limited studies have investigated such experiences in depth in this country, especially for mothers who, according to the culture of Iran, have a significant role in managing their children’s educational and current affairs. The conclusive findings of this study represent a foundational resource poised to catalyze a paradigm shift in the orientation of research, interventions, and policies concerning substance use and abuse. Rather than exclusively centering on individuals engaged in drug use, the study advocates for a broader perspective encompassing those impacted by addiction, including family members, caregivers, friends, and close relatives. The imperative for such a shift is underscored by the escalating trend of addiction within the country. A focused inquiry aimed at “hearing the voices of people in the shadows”, particularly mothers, becomes more pressing in this context. Accordingly, the outcomes of the present study hold significant relevance for researchers across the dual dimensions of prevention and treatment measures. Furthermore, the findings offer valuable insights for policymakers and experts, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the multifaceted challenges posed by addiction and informing the development of effective strategies to address its impact on individuals and their support networks.

Regarding prevention, the findings of the current study reveal that a lack of awareness within families, particularly among primary caregivers such as mothers, results in the adoption of unhealthy coping mechanisms when confronted with the issue of their children’s substance abuse. This condition not only gives rise to serious secondary problems but also diverts the family from the appropriate treatment trajectory. Consequently, the implementation of support policies and the formulation of preventive measures targeted at families at the initial stages of the problem can substantially contribute to alleviating the burden on both the affected family and the individual grappling with drug use or abuse. Such initiatives have the potential to guide families towards more informed and efficacious responses, thereby fostering a supportive environment conducive to effective prevention and intervention strategies. Furthermore, in the therapeutic domain, the outcomes of the current study hold the potential to deepen the understanding of researchers, policymakers (specifically deputies overseeing addiction prevention and treatment within the welfare sector and the Ministry of Health), and experts in the field of addiction, including social workers, addiction counselors, addiction psychiatrists, and addiction assistants. Leveraging the insights gathered from this data, stakeholders can formulate comprehensive and informed approaches tailored to addressing the needs of this specific demographic. The study’s findings can serve as a valuable resource for these professionals, enabling the development of enduring policies, research initiatives, and interventions. By actively involving families affected by addiction, these stakeholders can strategically integrate long-term measures into their agendas. This collaborative effort aims to enhance the psychological and social wellbeing of mothers, caregivers, and all those affected by addiction. By fostering economic empowerment, these interventions aspire to expedite the resolution of challenges engendered by addiction, facilitating a more expedient and effective recovery process. Furthermore, as the current study represents one of the initial endeavors conducted with a distinct focus on mothers affected by child addiction, comprehensively exploring diverse facets of their experiences and challenges, it serves as a foundational resource for the formulation of policies and specialized interventions. This study occupies a unique position within the existing body of research by shedding light on the nuanced experiences of caregivers grappling with the substance use or abuse of their children. The insights derived from this study hold significant potential for informing the development of targeted policies and interventions tailored explicitly for caregivers involved in the support and care of individuals dealing with substance use or abuse. Consequently, this study contributes to advancing knowledge in the field and provides practical guidance for implementing measures that address the distinctive needs of this caregiver population.

Relevance for clinical practice

Aligned with the findings of this study, organizations and groups engaged in the addiction field, such as Welfare Prevention Offices, the Addiction Department of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, municipal social affairs departments, Naranan groups (Association of Families of Addicts), social workers, specialists, counselors, and activists in the realm of addiction and family counseling should prioritize and implement measures to encourage the active participation of mothers impacted by child addiction. Recognizing these mothers as primary stakeholders in family issues, fostering their involvement in educational and support sessions emerges as a principal and highly effective mechanism for addressing addiction-related challenges, extending beyond the period of the child’s recovery. This approach reflects a strategic response that could be integrated into various addiction intervention and support practice entities. In essence, through the strategic utilization of effective resources and mechanisms, individuals can proactively navigate and surmount the direct and indirect challenges arising from addiction. This approach facilitates the establishment of a trajectory leading towards the attainment of “sustainable recovery” for both the individuals experiencing substance abuse and their family members. Hence, in pursuit of this objective, legal and structural backing is necessary to facilitate the growth of proactive groups in the domain, such as Naranan and non-governmental organizations specializing in addiction and family issues. Moreover, providing financial and legal support for researchers in this field is essential to catalyze prospective research endeavors. Such support would contribute to the strategic development of future research initiatives specifically targeting families affected by addiction and elucidating the intricate dynamics of the recovery process within families. It is also necessary for policymakers in this field to consider families and main caregivers as one of the important elements in their plans and policies in addition to the individual in the process of dealing with addiction.

Study limitations

In broad terms, a notable strength of the current study lies in its deliberate focus on capturing the perspectives of an often-overlooked group within the domain of addiction. This particular demographic, though integral, has received comparatively less attention in existing studies, interventions, and addiction-related services. However, the study is not without its limitations, the mitigation of which could substantially augment the richness of the data. Challenges include non-random sampling, no interviews with the affected children, and restricting samples to a singular city and center. Furthermore, a significant constraint arises from the study’s participant composition. Despite employing an inclusive approach, all participants are mothers actively engaged in specialized support and training sessions tailored for families affected by addiction. Consequently, their experiences may differ from those of mothers who do not partake in such sessions. Hence, it is recommended that the participant pool be broadened to encompass diverse groups for future investigations. Additionally, there is a need to scrutinize the departure process of families, particularly mothers impacted by their children’s addiction, with greater precision to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the myriad challenges they encounter.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.114). Also, before participating in the study, all participants read and signed a written informed consent form, and the researcher answered all their questions carefully and patiently. No specific ethical issue was reported during the study, and no participant withdrew. All participants were completely assured of the confidentiality of their information during and after the study.

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Mostafa Mardani, approved by Department of Social Work, School of Behavioral Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Study design: Mostafa Mardani, Fardin Alipour and Hassan Rafiey; Conceptualization and formal analysis: Mostafa Mardani and Fardin Alipour; Data curation: Mostafa Mardani; Investigation, methodology, resources, and visualization: Mostafa Mardani; Supervision: Hassan Rafiey and Masoud Fallahi-Khoshknab; Review and editing: Fardin Alipour, Hassan Rafiey and Maliheh Arshi; Final approval: All authors.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Rebirth Charity staff who assisted with the recruitment.

References

Drug abuse is a global issue that extends beyond the boundaries of any specific country. According to an estimate by the United Nations drugs control program (UNDCP) in 2020, 5.6% of the world’s population was involved in substance abuse [1]. Iran, given its unique geographical location, is not exempt from this crisis and has witnessed an upward trend in the utilization of various narcotics [2]. It is important to emphasize that problematic substance use encompasses more than just frequent narcotics or alcohol consumption. It also includes the challenges individuals and their families face and the subsequent adverse consequences [3, 4, 5, 6]. While much attention has been directed toward the affected individuals in addiction studies and interventions, there is a gap in the impact of addiction on other individuals, particularly the families and primary caregivers.

Regarding the rising challenges and consequences of drug and alcohol abuse for addiction-affected family members (including spouses, children, parents, siblings, and relatives), it is now more evident that these groups require keener focus and consideration [7, 8, 9]. Generally, these individuals are profoundly impacted by the substance abuse of one or more family members, experiencing various health-related issues at different levels [6, 9, 10, 11]. Not only do addiction-affected family members have to deal with multiple problems related to supporting the addicted person [4, 5, 12], but they also spend significant effort in mitigating the problems arising from addiction within the family, such as instances of violence, arguments, and disputes [8]. Although studies have provided valuable insights into the personal experiences of individuals grappling with addiction, a substantial gap still exists in the current literature when it comes to exploring the specific challenges, dynamics, and coping mechanisms within families affected by addiction [13, 14]. In other words, such studies overlook the other side of addiction, which is addiction-affected families [15].

It is noteworthy that among the family members, parents experience the most profound level of involvement with the problem [16, 17] and endure immense mental [18, 19] and emotional pressure [16, 17, 19, 20]. This pressure arises from various factors, including financial stress, family conflicts, struggles with their children, and so on [18-21]. Given the pivotal role parents assume within the family dynamic, mothers, in particular, involve themselves more than any other family member in addressing their child’s problem, seeking solutions to cut them from the grip of addiction.

Groenewald revealed that mothers of children struggling with substance abuse experience a range of distressing emotions, including emotional distress, desperate cries for help, and thoughts of suicide [22]. Additionally, other unpleasant experiences, such as constant worry, persistent anxiety, feelings of shame and fear towards their child, family conflicts, severe financial problems, and a sense of hopelessness and guilt, have been stated by addiction-affected mothers [23]. Furthermore, studies have documented additional experiences, including feelings of mistrust and betrayal, as well as occasions where mothers felt compelled to leave their homes due to fear of their teenager’s unusual behaviors [19-21]. While addiction has been associated with detrimental effects on families in different countries, the diverse array of consequences that addiction can have within various cultural contexts should not be overlooked [24]. Although some quantitative studies have evaluated the effects of addiction on families and parents, qualitative studies in this field are very limited [25-30]. There is a pressing need for designing various studies to explore the experiences of addiction-affected mothers (AAMs) within diverse cultural settings. Qualitative studies hold immense potential to explore deep and new experiences, which can, in turn, enhance the generalizability of findings and contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter [31]. Furthermore, gaining a deeper understanding of issues in this field can help deliver the best possible services to AAMs as they navigate the complexities associated with their children’s addiction. Despite the existence of numerous studies in this area, rehabilitation service providers still face a gap concerning the experiences of parents, especially mothers, as the most involved family members [32].

Examining maternal experiences has predominantly originated from the distinctive care giving role assumed by mothers within both Iranian and global cultures. In these contexts, mothers are responsible for caring for their children, primarily monitoring their children’s health and considering their wellbeing as an ultimate duty [19, 33-35]. Notably, studies investigating the experiences of parents affected by addiction, specifically in relation to their children’s substance abuse, consistently report fathers’ low participation rate. Consequently, women, particularly mothers, constitute the primary participants in such research endeavors [23]. Given the circumstances mentioned above, there exists a compelling need for further research within the realm of mothers affected by child addiction. Such research instills a paradigm shift in therapeutic approaches and theoretical frameworks. Through the execution of comprehensive and meticulous investigations, a profound understanding of this complex phenomenon can be achieved. This collective understanding has the potential to alter prevailing perspectives and facilitate advancements in the field.

Furthermore, a solid foundation can be established for future treatment modalities by discerning the positive facets of maternal experiences and highlighting their practical efforts and strategies in the recovery process. Consequently, this study endeavors to explore the experiences of Iranian mothers affected by their child’s addiction, recognizing the challenges encountered in managing a child with substance abuse. The qualitative nature of this study, relying on an interview-based approach, is essential for capturing the nuanced dimensions of maternal experiences in this context.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This study used the phenomenological method to delve deeply into the experiences of AAMs. The fundamental principle of phenomenology states that each individual’s encounter with a particular phenomenon is unique, and different individuals may have distinct experiences of the same phenomenon [36]. Bracketing, assessing, and understanding the nature of the phenomenon are the three key steps researchers need to consider when trying to understand a phenomenon [37]. In the present study, data collection and analysis were conducted using interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), which provides a deep understanding of the phenomenon and integrates phenomenological and hermeneutic principles. In general, the IPA method can be a suitable and effective strategy when researchers want to understand a process or its changes or problems that have received little attention or are new and complex. This method considers social, historical, contextual, and situational factors to understand the phenomenon better [38].

Study participants

In this study, 9 mothers affected by addiction, whose children were not involved in addiction at the time of the research and had completed the stages of recovery, were included in the study using the purposeful sampling technique. In qualitative research, the sample size is between 6 and 10 people, but this amount can be increased if information saturation has not been achieved [39]. This study involved 9 mothers affected by their children’s addiction, who, at the time of the study, were actively engaging in educational and support sessions following their children’s recovery (Table 1).

The average age of these individuals was 50 years, and they had been serving in their supportive role for consumers for at least three years. All participants resided in the urban setting of Tehran City, Iran, and the predominant substances used by their children were methamphetamine, heroin, and opium. All participants in the current study were mothers who, following their child’s recovery, actively endeavored to mitigate the challenges associated with their child’s addiction.

Additionally, they dealt with residual issues arising post-recovery. Over at least one year, these mothers participated in specialized training and support sessions facilitated by the Rebirth Charity Organization in Tehran, Iran. The Rebirth Charity Training Unit was pivotal in disseminating information to mothers. Following the inclusion criteria of the present study, this unit provided contact information for the participating mothers to the researchers.

Moreover, with a commitment to safeguarding confidentiality in handling information and interviews, all participants were assured that only the researcher would have access to their information. In addition, confidentiality principles were followed, and participants were assured of their privacy. Detailed explanations of the study’s protocols were provided to them, accompanied by their written informed consent. The inclusion criteria consisted of mothers who had experience of caring for children with substance abuse issues, and mothers whose children had entered the recovery period during the study (this refers to the process through which individuals transition from the challenges of drug use to a life-free from substance abuse, ultimately becoming integral contributors to society) [40, 41], absence of other family members with addiction issues, and mothers actively seek psychological and social support. In this current study, we focused on mothers who had reached the conclusion of their children’s journey through addiction and had gained a comprehensive understanding of the various challenges and issues associated with addiction, persisting even after their children’s recovery. This selection aimed to capture profound and valuable experiences that these mothers had acquired throughout this process, providing insights for researchers and the broader public. The decision to emphasize mothers who dealt with the aftermath of addiction stems from the crucial need to address the lingering issues of post-recovery. It is noteworthy that a prevalent public opinion assumes that once an individual’s addiction concludes, all related problems cease to exist. However, our study acknowledges and explores the often-overlooked complexity of these lingering challenges.

Data collection

Notes and recorded audio were employed as additional data collection tools alongside interviews. The interview guide followed the study’s objectives and existing literature to explore the experiences of AAMs (Table 2).

To ensure clarity, any misunderstood questions were explained in detail, and the research team maintained a non-judgmental and unbiased stance during interviews. Qualitative research relies on audio recordings, observations, and interviews to gather data without quantifying information. Thus, this study incorporated field notes and observations to capture non-verbal responses, the interview atmosphere, and participants’ behavioral expressions. Before interviews, a session was conducted to thoroughly explain the study’s objectives and establish clear expectations for participation. It is worth noting that all interviews were conducted at the central office of the Rebirth Charity from September 2022 to March 2023 to explore participants’ experiences through individual, semi-structured, and face-to-face interactions. The interviews took 60 to 100 minutes, with each participant being interviewed only once. Interviews concluded once the necessary information was obtained to fulfill the research objectives and data saturation was reached. The potential risk of compromising data quality due to the researcher’s prior interaction with participants (during a meeting to explain the research protocol) was attentively addressed throughout the study. At the end of the interviews, gratitude was expressed to participating mothers for their contributions, and they were informed of the availability of a summary of the findings should they express interest.

Data analysis

The data analysis process within the IPA method encompasses several steps [42]. Initially, the interviews were transcribed verbatim, and the resulting transcripts underwent extensive scrutiny to conduct a thorough textual analysis, thereby facilitating a comprehensive understanding of the participants’ experiences. The primary objective of this phase was to capture the mothers’ narratives and assimilate their non-verbal information to establish relevant themes. Furthermore, each transcript was precisely reexamined several times to develop the main category and subcategories. The data analysis followed an inductive approach, where efforts were made to avoid any unexplained missing data. Each authentic participant’s expression was regarded as a distinct code to maintain impartiality and prevent personal bias from influencing the data [43, 44]. These codes were subsequently organized into temporary themes and their corresponding subthemes. A meticulous process of clustering and merging was employed to unveil the interconnections between the identified themes. This process enabled a higher level of data extraction through focused and precise analysis [38]. This iterative and inductive process persisted until data saturation was achieved [36]. It is noteworthy that in this study, the path of the semantic analytic level was from data description in the results section to data interpretation in the discussion section. Regarding the continuous connection between the researcher and the participants during the study, all stages of data coding and analysis were undertaken by a single researcher to ensure methodological rigor and coherence [45].

Reflexivity

The study utilized the interpretive IPA method to understand AAMs’ experiences deeply. In this study, to reduce and minimize the effects of the researcher and the effects of her experiences, values, previous assumptions, and priorities on the research process [46-48], self-awareness, self-questioning, and rethinking have always been of interest to researchers [47-49]. Furthermore, reliability and validation criteria were employed to enhance accuracy throughout the study, involving an analyst appointed to conduct the analysis [50]. Moreover, validity was ensured in this study through meticulous participant selection aligned with the sampling criteria, emphasizing maximum diversity. This measure involved multiple meetings to establish a consensus on various coding aspects and theme identification. The participants played an active role in summarizing and reviewing interviews. Additionally, scrutiny of data and codes by the research team and professors contributed to the robustness of the study. The researchers also expressed keen interest in incorporating field notes and reminders alongside the semi-structured interview format.

Results

Nine AAMs with the experience of caring for a child with substance abuse issues participated in this study (Table 1). The average age of the mothers was 50 years, and they all had at least three years of supporting their affected children. All participants resided in the city (Tehran City, Iran), and the most common substances used by their children were glass, heroin, and opium. The data analysis and the codes extracted from the interviews revealed four main themes (social isolation, the swamp trails, the continuum of injuries, and the pursuit of freedom) and 14 subthemes (Table 3).

One of the topics mentioned more than anything else in this study was the initial struggle faced by mothers in responding to the problem, a concept referred to as running on a treadmill, ending up in a continuum of problems for mothers. The first three themes reflect the experiences that mothers went through when dealing with their children’s substance abuse. In contrast, the fourth theme indicates the measures mothers employ to counteract the situation.

Theme 1: Social isolation

After discovering their children’s addiction problem, all AAMs, in some way, went through a social isolation episode driven by their desire to avoid social labels, stigma, and judgment from others. The “shame and embarrassment” and “reduced social interactions” are the subthemes that emerged from this main theme.

Shame and embarrassment

Most mothers admitted in their interviews that one of their unpleasant experiences was the feeling of shame and embarrassment in relation to their child’s addiction and its visible impact on their behavior and appearance.

“When we lived in an apartment, I would quickly close our door whenever a neighbor entered the building because I didn’t want to see them at all. I felt that if they saw me, they might say, ‘She’s the mother of the boy who uses drugs.’ It was becoming really difficult for me, which is why I always told my husband that I didn’t want our son to come with us as long as he was struggling with addiction” (Participant (P) No. 1).

“When he crossed the line in a way that his face and appearance clearly turned unusual, it became evident that my child did not have the mood to groom himself. That’s when I realized that he had been using drugs and had become a drug addict. Since then, I have told my husband that we shouldn’t allow anyone to see him or go out with him anymore” (P No. 6).

Reduced social interactions

Mothers dealing with shame and embarrassment felt compelled to hide from the judgmental gaze of others, resulting in reduced social interactions. The fear of being judged by others and people’s strong guard against addiction were among the most important issues addressed by mothers with regard to their social isolation.

“As soon as my child became addicted, people immediately started judging me, claiming it was my fault and that I was the reason for this situation; everyone said that I was responsible and should be condemned. I was always blamed by others, from my family to my husband; they all insisted that I was the one to blame” (P No. 8).

“Because of the fear of being judged by others, it feels as if your voice is silenced; you want to cry out loud, but it seems that your roar is always silenced. I always wanted to scream and shout to stop him, but I was afraid of neighbors’ judgment, and the fear of being blamed and humiliated held me back. As a matter of fact, I felt all these things; one cannot ignore people’s looks; it was always there, I saw it, I felt it, and that is why I decided to stay away from them”(P No. 1).

“Even when you attempt to confide in someone, they mistreat you or say words that even hurt you more. Well, in such a situation, one has to keep a distance from these people” (P No. 7).

“My whole family members were educated, but they did not even have a single clue in their minds about this disease; I could not talk to them at all; they had a very strong guard against this problem” (P No. 8).

Participants acknowledged the complex circumstances they had to navigate in every interaction, considering the appearance and behavior of their child, their own mental condition, the timing of their child’s drug consumption, etc. This led them to withdraw from social engagements, seeking to minimize judgment and labels from others as much as possible.

“When this problem happened to my child, I decided not to go anywhere. I was all by myself and kept a far distance from everyone to avoid hearing their words, but they would talk anyway indirectly. Maybe they did not mean me, but I took it to myself. I tried to avoid any form of communication with others (P No. 3).

“In reality, there were many things before that no longer exist after the addiction. For example, the simple and peaceful interactions I once had with others are now a thing of the past, and I don’t foresee them returning. If I wanted to communicate with the closest people to me, I would be limited by time constraints. I always have to consider my child’s condition and his consumption time. Our relationships, the feeling that you want to have in society, walking proudly with your own child, all would vanish because you have to terminate all relationships with others, even the closest people to you, like your own sister or colleague. I even had to quit my job” (P No. 7).

Theme 2: The swamp trails

Initially, AAMs resisted seeking official and unofficial support or engaging with specialized institutions to avoid exposing their child’s addiction problem to others. Instead, they adopted several self-recommendation measures, leading them into challenges, such as denial, seeking answers, struggling, and marginal ways, which were like a swamp or the Bermuda Triangle for them.

Denial

“I could not accept it at all; I thought that no one in our family used drugs; I believed our entire family was clean, and I could not accept that my kid could be addicted to drugs (P No. 2).

“My husband always told me nothing was wrong; perhaps we were resentful, and he wanted to calm us down. He always convinced me that there was nothing to worry about; nothing would happen. This drug is not for him; it belongs to his friends. He blamed his friends for influencing our child” (P No. 4).

Seeking answers

Most mothers in this study emphasized the significance of understanding why their children fell into addiction, and they started searching to find a solution to their child’s addiction through various ways and countermeasures. Experiencing a state of ambiguity and uncertainty, self-prescribed treatments, impulsive actions, and making decisions without consulting others were among the reactions mentioned by most of the mothers in this context.

“After my child’s addiction, I fell into the path of searching for people to ask them where to go; some suggested I visit the Esteghlal Park to identify the substances my child was consuming, to understand what I saw in his hand” (P No. 1).

“My first mistake was that I attempted to administer the treatment myself; my child was not mentally and physically ready to accept the treatment, but I forced him to go for the treatment. I made a mistake; I thought the best solution was to compel him to go to a rehabilitation camp” (P No. 8).

“You may not believe it, but I sold all my furniture and all I had in my life except for my house; I sold everything, and I changed my city. To avoid being alone, I took one of my relatives with me, rented her a house, and spent a lot of money on her. I thought this would help us a lot. I made all the decisions alone, convinced that I was making the right choices” (P No. 7.)

Struggling

AAMs consistently perceived self-suppression, attempts to compensate for the repercussions of addiction, aimless wandering, and co-dependency as recurring struggles. They admitted that they would grab on anything desperately to find a way out of their problems.

“I have always likened this process to an unwanted swamp sinking both me and his father; my child is outside the swamp; the harder we struggle to reach him, the deeper we sink. That’s exactly how it felt”(P No. 1). She added, “Many mothers, like myself, find themselves in the same position; we do not know what to do, which makes us try every devious way to gain understanding.”

Marginal ways

This subtheme is closely related to the concept of “mothers’ struggling.” Somehow, mothers have tried to control the situation through marginal ways and complementary actions, such as restricting and controlling the child, planning for the child’s life, providing inappropriate support, implementing financial sanctions, or rejecting the child. However, these actions only exacerbated their problems.

“I finally decided to talk to my child, telling him not to go out with his friends and offering other pieces of advice. These friends are not beneficial to you. I was trying to control him emotionally. I even would chase after him. If he did not return home at night, I would force his father to go to his friends’ houses, no matter if it was 1:00 AM. In a way, I was always present at their gatherings from a distance”(P No. 9).

“I told my son that I would not give him a single rial (Iran’s currency) and would not support him anymore, telling him: If you want to leave, do not come back at all; if you still want to take drugs, do not come home anymore; even if you come again, I won’t open the door”, (P No. 5).

Theme 3: The continuum of injuries

Within the support process, various subthemes emerged from the data, highlighting the sequential problems and harms experienced by mothers. These subthemes included self-neglect, weakened internal interactions, weakened physical, mental, and psychological health, economic insecurity, and self-blaming.

Self-neglect

Mothers’ involvement in their child’s addiction often resulted in neglecting their wellbeing above all else. In other words, they would disregard their daily affairs and health concerns, creating many problems for themselves both during the child’s addiction and after recovery.

“I completely forgot that I also needed to take care of myself as well, that I needed to remain healthy, that I could use the opportunities when my child would come along with me. But I could not deliver it at all; I was so mentally and physically engaged with this issue that I completely neglected myself and my own needs. It was the same for my health; I would not go to a doctor at all, even when I felt sick”(P No. 1).

Weakened internal interactions

A common issue mentioned by all mothers in the study was their neglect of other family members due to constant attention to the affected member. In a way, mothers prioritized providing financial, psychological, and emotional support to their affected child, resulting in detachment among family members. This detachment manifested in extreme marital disputes, thinking of divorce, and the propagation of the problem to other members, especially other children.

“During that time, my attention shifted away from my daughter. I neglected her, and this was tormenting for me. My daughter was mentally traumatized because she was constantly exposed to the stress and deterioration caused by her brother and me. This was bothering her, not knowing where her brother was. For example, several times when Amir overdosed, she was distressed witnessing a family member’s illness, but she did not receive my attention” (P No. 8).

“When addiction entered our family, I felt hatred toward my husband and really wanted to divorce him. I believed that separating from him would improve my situation. I assumed the reason for all these problems was my husband, so I should leave him”(P No. 9).

Weakened physical and psychological health

During the initial phases of this problem, AAMs encountered various challenges that affected their physical and psychological wellbeing. These challenges included life losing its vibrancy, reaching a dead end, desperation and helplessness, depression, suicidal thoughts, facing mental and psychological pressure, constant comparison of their lives with others, engaging in repetitive and intrusive thinking, developing various physical ailments, and physical exhaustion.

“I felt like I was not living at all; I was a crazy and confused person who just opened her eyes in the morning, grabbed a cup of tea, and just thinking what I could do today. Everything seemed devoid of color and meaning to me”(P No. 1).

“When you look around and see children of the same age in the relatives, observing their achievements, and thinking about where your child should have been, but instead realizing where he or she actually is. These thoughts and comparisons are truly devastating” (P No. 7).

“Because of the pressure I endured, I developed early menopause and had to take medications for a long time, I extracted a lot of my teeth, I got diabetes, and the doctor said that my diabetes was neurological”(P No. 3).

Economic insecurity