Volume 25, Issue 2 (Summer 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(2): 248-265 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Paknia M, Abdi K, Shahshahani S, Hosseinzade S. Translation and Psychometrics Evaluation of the Persian Version WatLX Patient Experience Survey of Outpatient Rehabilitation Care. jrehab 2024; 25 (2) :248-265

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3314-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3314-en.html

1- Department of Rehabilitation Management, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Rehabilitation Management, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,k55abdi@yahoo.com

3- Department of Rehabilitation Management, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Rehabilitation Management, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Rehabilitation Management, Pediatric Neurorehabilitation Research Center, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, School of Social Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

Full-Text [PDF 1968 kb]

(1062 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5542 Views)

Full-Text: (1607 Views)

Introduction

Patient-centered care is recognized as the top priority in the healthcare system. Achieving patient-centered care requires a more comprehensive understanding of patients’ experiences during their interactions with the healthcare and rehabilitation system [1]. With the aging population, an increasing number of individuals living with chronic disabilities require rehabilitation services, necessitating a novel approach to delivering and measuring services in diverse healthcare structures [2]. Rehabilitation care assists individuals with reduced functionality in achieving a desirable range of capabilities and skills [3]. There is growing evidence indicating that patient-reported actions correlate with better health outcomes, including increased treatment adherence, reduced hospital stays, enhanced presence, improved functional capacity, and fewer signs of depression in rehabilitation environments [4-6].

Most studies emphasizing the improvement of services evaluated negatively by patients emphasize the use of surveys. This approach focuses on improving service inputs and processes that identify patient needs and includes developmental activities that enhance service providers’ skills in recognizing and addressing patient concerns [7]. Measuring patient experience, especially in rehabilitation services, is suitable as the coordination and continuity of care often face challenges with medical complexities and the engagement of multiple healthcare specialists across the healthcare system [8]. Additionally, patients requiring rehabilitation care often need more than one type of service, provided by different providers simultaneously and multiple times over time [9]. As more providers are involved, patients’ experiences in the received care quality will differ [10]. Doyel et al. identified patient experience as a key pillar in improving the quality of healthcare, demonstrating a positive correlation between patient health and clinical clinic efficiency [11]. Understanding the patient experience is a crucial step in moving toward high-quality patient-centered care [12]. While there is a substantial and growing body of literature on tools measuring patient experiences [13], there is limited research done on measuring patient experiences in rehabilitation care [13]. The definitional ambiguity between patient experience and patient satisfaction has made developing a valid and reliable instrument challenging. Patient experience is a multidimensional structure encompassing a wide spectrum of patient interactions with the healthcare system [12]. Jenkinson et al. define experience as what has happened to the patient in the face of health and describe satisfaction as the patient’s evaluation of the encounter [14]. Slade and Keting suggest that the patient satisfaction questionnaire concerns general questions related to care providers and researchers, while the patient experience questionnaire relates to patients and assesses healthcare providers’ expertise in dealing with healthcare encounters [15].

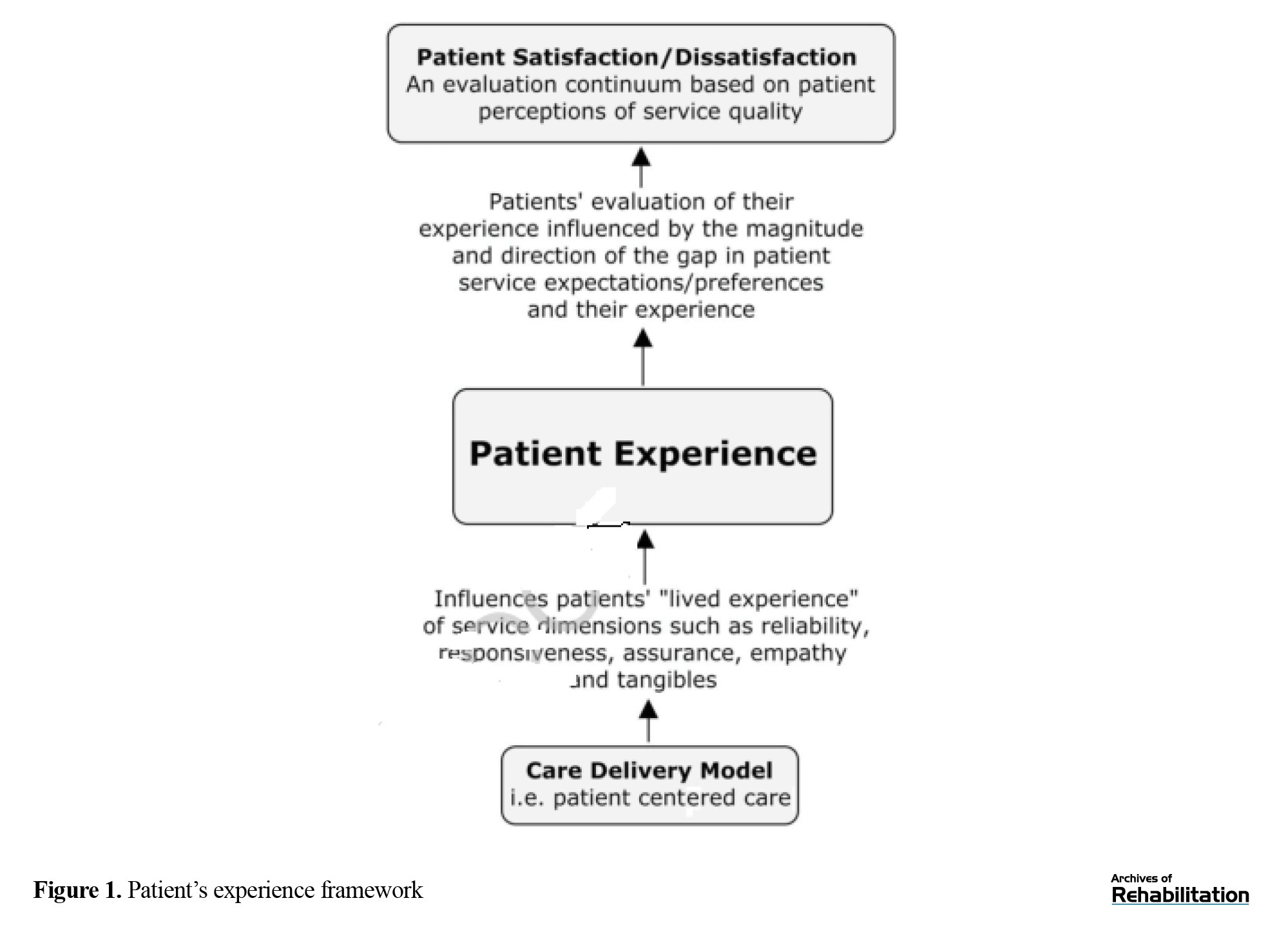

On the other hand, patient satisfaction indicates an individual’s pleasure or disappointment, relatively resulting from the individual’s evaluation of the service against personal values and expectations [16]. The degree and direction of the gap between patient experience and expectations, preferences, and values determine patient satisfaction. If a patient expresses satisfaction with services, it is assumed that they were satisfied after using it and that their expectations have been met. Some have referred to this area as the tolerance zone, acknowledging a range where patients report their satisfaction due to various moderating effects of expectations and preferences. It is also possible that each service encounter creates a different history due to the nature and essence of that service. Therefore, patient satisfaction is less tangible in actual representation [17], and patient experience is instrumental in identifying areas for useful and supportive improvement [14]. Accordingly, the patient’s experience, conceptually, differs from the patient’s satisfaction, requiring a different framework of understanding before it can serve as a performance metric (Figure 1) [12]. As the healthcare system moves toward integrating service delivery across structures and providers in geographical regions, regulatory and budgetary institutions have begun examining how the overall patient experience is measured within the healthcare system and service-providing organizations [18]. All these factors lead to the question of how can financial providers of the healthcare system and regulatory organizations effectively oversee the quality of the patient experience in a unified rehabilitative care system [12]. Providers and organizations can use the Waterloo Wilfrid Laurier University rehabilitation patient experience instrument (WatLX) to assess and report the quality of healthcare experiences and patient perspectives as part of their quality service audits and inspections. Considering the absence of standardized tools in Iran to assist managers and service providers in identifying quality improvement areas from the patients’ perspective in various rehabilitation services, the localization of a reliable and sustainable tool like WatLX is suitable for measuring the rehabilitative service experience within the Iranian community.

Materials and Methods

Study participants

This psychometric study was conducted in 2023. The study population consisted of adults aged 18 and above who visited physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy centers and clinics in Tehran City, Iran, to receive one of the rehabilitative services, such as cardiac, musculoskeletal, neurological, stroke, pulmonary, or speech therapy. Sampling was done systematically based on the available sampling method. Initially, rehabilitation centers, both private and public, in Tehran City, Iran, were considered in five geographical zones as follows: North, south, east, west, and center. A total of 10 rehabilitation centers were selected, including Rafideh Hospital, Asma Rehabilitation Center, Haji Baqeri Physiotherapy Center, Omid Shargh Occupational and Speech Therapy Center, Nazam Mafi Rehabilitation Center, Bahrad Physiotherapy Center, Darya Speech and Occupational Therapy Center, Raad Al-Ghadir Rehabilitation Center, Dastan Occupational Therapy Center, and Brain and Cognition Clinic. These centers collaborated and provided the setting for participant recruitment and data collection. Given that a sample size of 5 to 10 individuals per item is sufficient for psychometric studies, considering the 10 questions in the mentioned questionnaire, a minimum of 100 samples was targeted, and ultimately, 115 participants completed the questionnaire. The inclusion criteria were adults above 18 years old with either a healthy cognitive level or mild cognitive impairment (scoring more than 6 on the abbreviated mental test [AMT] questionnaire).

Study instruments

Demographic questionnaire

A demographic questionnaire collected the data on participants’ age, gender, education level, initial conditions, and issues for receiving rehabilitation services, duration of rehabilitation services (number of sessions), type of rehabilitation service, and the name of the rehabilitation clinic and center. All the details were gathered through the WatLX questionnaire.

Abbreviated mental test

AMT was used to assess participants’ cognitive levels as an entry criterion. The Persian version of the AMT has been shown to have good validity and reliability in various studies.

WatLX

The WatLX questionnaire comprises a set of simple questions designed for management in standing rehabilitation centers, examining the rehabilitation care experience in standing patients. Developed in Canada by a team of researchers from the University of Waterloo and Wilfrid Laurier University, led by Josephine McMurray and Paul Stole, in collaboration with the Rehabilitative Care Alliance, the English version of WatLX consists of 10 items and one question about expressing the overall patient experience. The questions cover various aspects, such as courtesy and kindness, decision-making, family/friendliness, environmental conditions, pain goals, safety information, expectations, and recommendations. The participants rate each item based on a 7-point Likert scale (completely disagree=1 to completely agree=7), and the total score is the sum of these ten questions. The final question about the overall experience is rated based on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 10. The reliability of this tool has been tested with over 1000 patient participants. No statistically significant difference was found in the mean WatLX response between men and women. There was no significant correlation between age and WatLX total score, and no significant difference in WatLX total score was observed based on the patient’s medical condition.

Persian version of Medrisk instrument for measuring

The Persian version of the Medrisk instrument for measuring was designed in 2005 by Betty et al. and consists of 20 items, of which 10 items were related to the therapist-patient relationship (internal factor), 8 were related to service aspects such as the admission process and secretary behavior (external factor), and 2 items were related to overall satisfaction. This brief and useful questionnaire assesses patient satisfaction with physical therapy services for musculoskeletal problems. In a study by Abdolalizadeh, the Persian version of this tool showed good internal consistency and reliability. The Persian version of the WatLX questionnaire, used in this psychometric study, provides a reliable and culturally adapted tool for assessing the experience of standing rehabilitation care in Iranian patients. The study employed rigorous sampling and inclusion criteria, ensuring the validity and reliability of the data collected through WatLX and other supporting tools, such as AMT and MedRisk Instrument for measuring.

Study implementation method

Initially, permission to use the tool was obtained from the questionnaire designer, Professor Josephine McMurray. The translation process started with the English-to-Persian translation and back-translation. The English-to-Persian translation was done by a translator proficient in English and Persian. Subsequently, the reverse translation to English was performed by another translator proficient in both languages, without access to the original questionnaire. The English version was sent to the original author for confirmation after the translated questionnaire was validated for consistency and alignment with the original version by the corresponding author. Content validity was assessed through the Lawshe method with the participation of 14 experts and faculty members specializing in physical medicine and rehabilitation, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and rehabilitation management. Items were evaluated for relevance and necessity. The content validity ratio (CVR) was calculated, considering a minimum acceptable score of 0.51 for 14 experts. Based on the results, one question was removed, and three additional questions were added. In the second step, 13 experts completed a second round of evaluation, and one of the added questions was eliminated based on the minimum CVR score. The open-ended questions section was also removed.

Face validity was assessed through qualitative content review by 10 participants from the study population. No issues were identified in this phase, confirming the face and content validity of 11 questions. To examine the tool’s reliability, collaboration was established with rehabilitation centers across Tehran City, Iran. Sampling was done with the coordination of managers and officials of these centers.

Individuals based on the inclusion criteria were approached, and informed consent was obtained. The participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information, and they were informed that their participation would not disrupt their treatment process. The participants completed the WatLX questionnaire, and 50 participants also completed the MRPS questionnaire for convergent validity assessment. A subset of 39 patients completed the WatLX questionnaire again after two weeks for test re-test reliability assessment.

Data analysis

The content validity was assessed using the CVR index. The minimum acceptable value for CVR, based on the Lawshe method, was equal to 0.51. The internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach α for item homogeneity, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and the standard error of measurement for test re-test reliability. The convergent validity was assessed through Pearson correlation coefficients between WatLX and MedRisk Instrument for Measuring scores. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using the principal component method and Equamax rotation to explore the underlying structure of the questionnaire after changes in questions. This detailed methodology provides a comprehensive approach to the translation, adaptation, and validation of the WatLX questionnaire for assessing the experience of standing rehabilitation care in Iranian patients.

Results

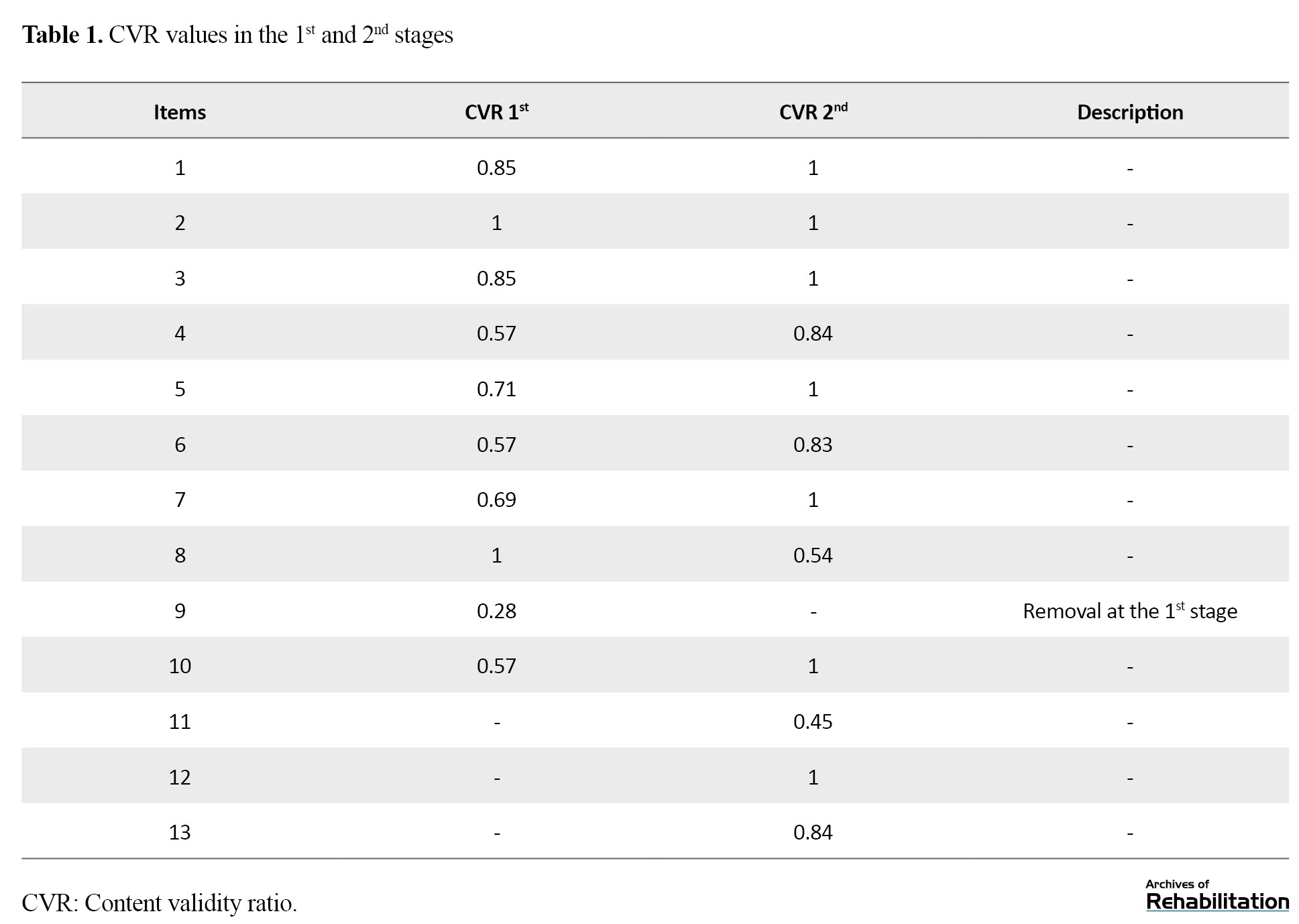

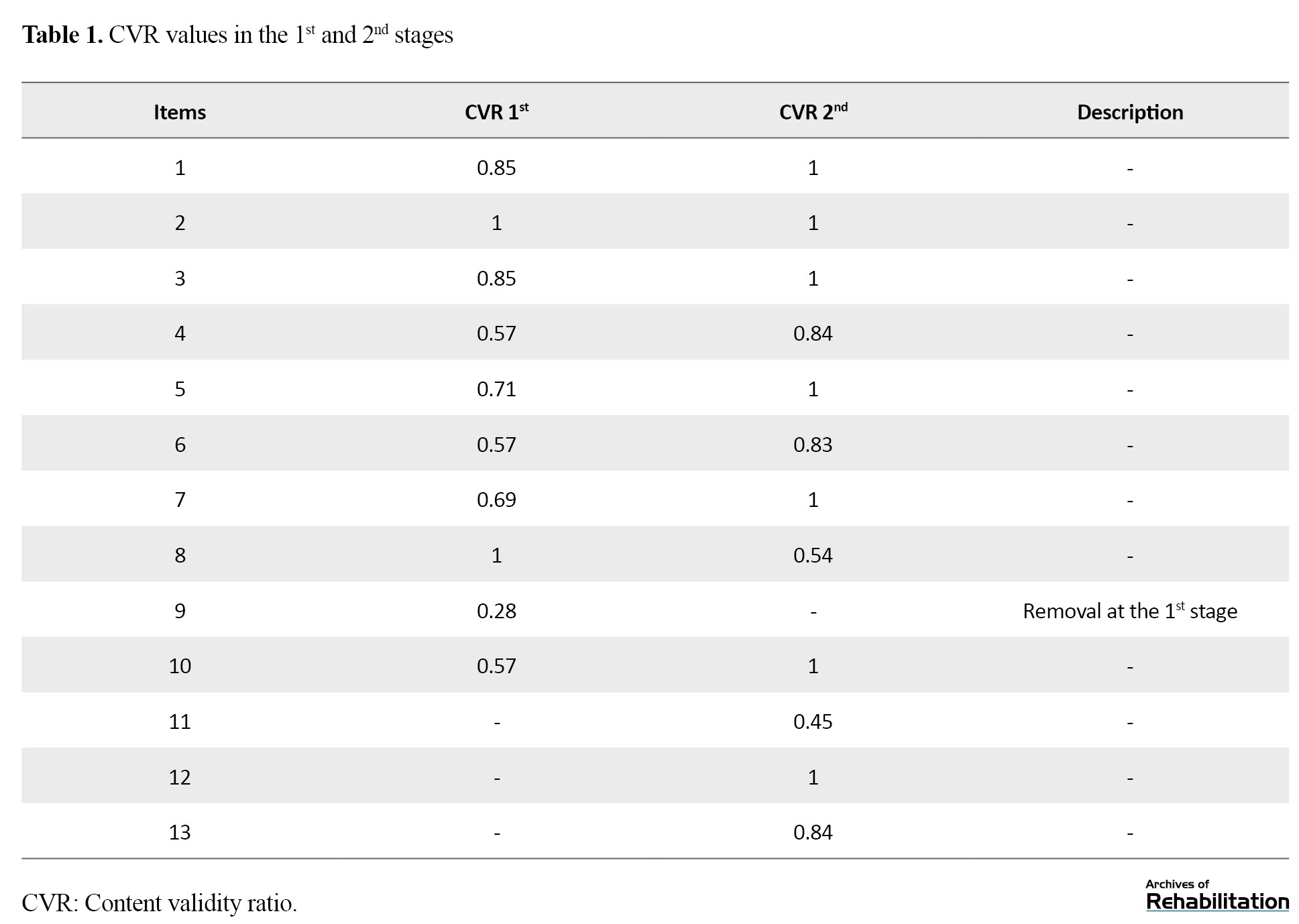

The first and second stages of content validity assessment for the tool have been completed. Overall, one question was added to the existing items of this tool, and the content and face validity of this question was confirmed by experts, the tool designer, and the surveyed community (Table 1).

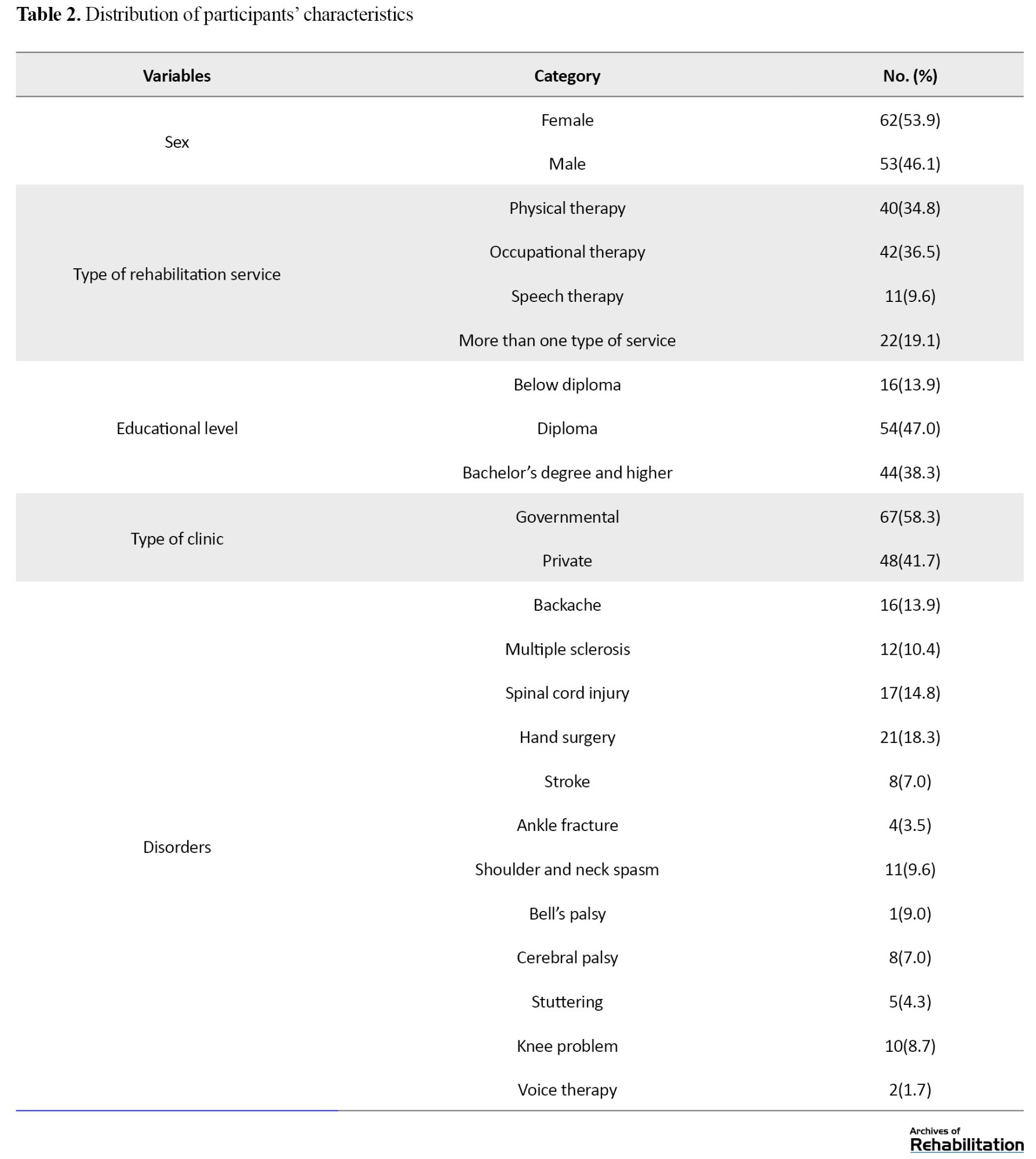

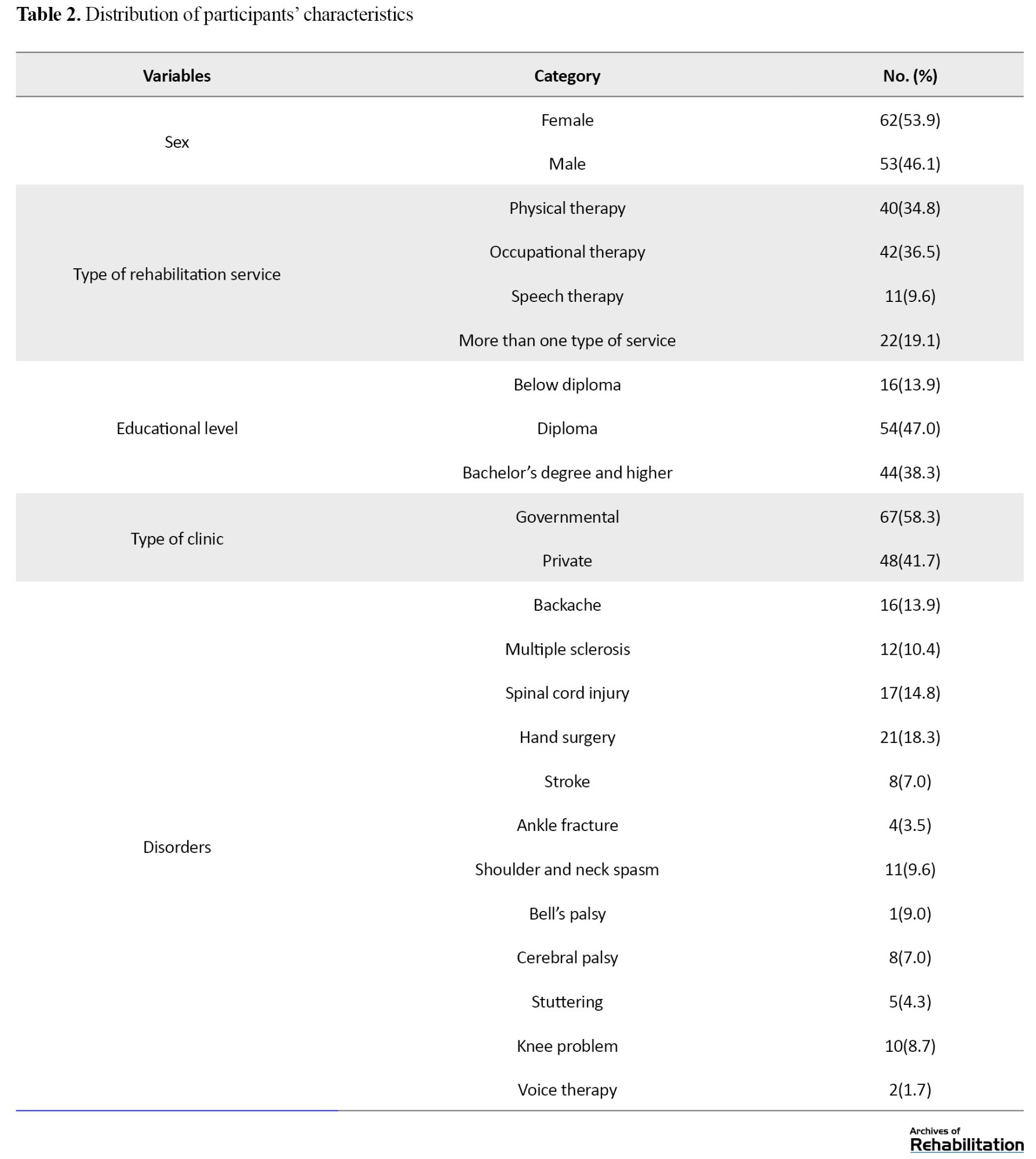

A total of 115 participants took part in the study. The Mean±SD age of the participants was 42.8±16.7 years. Meanwhile, 53.9% of the participants were female. Among the various disorders, participants with low back pain, hand surgery, and spinal cord injury had the highest number. The most common type of service received was physical therapy. Nearly 60% of the participants were from government clinics. The majority of participants had a diploma-level education (47%) (Table 2).

The Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that the total score of the WatLX tool in the sample of 115 individuals does not follow a normal distribution (P<0.05). However, the total score of the Medrisk tool in the sample of 50 individuals follows a normal distribution (P<0.05).

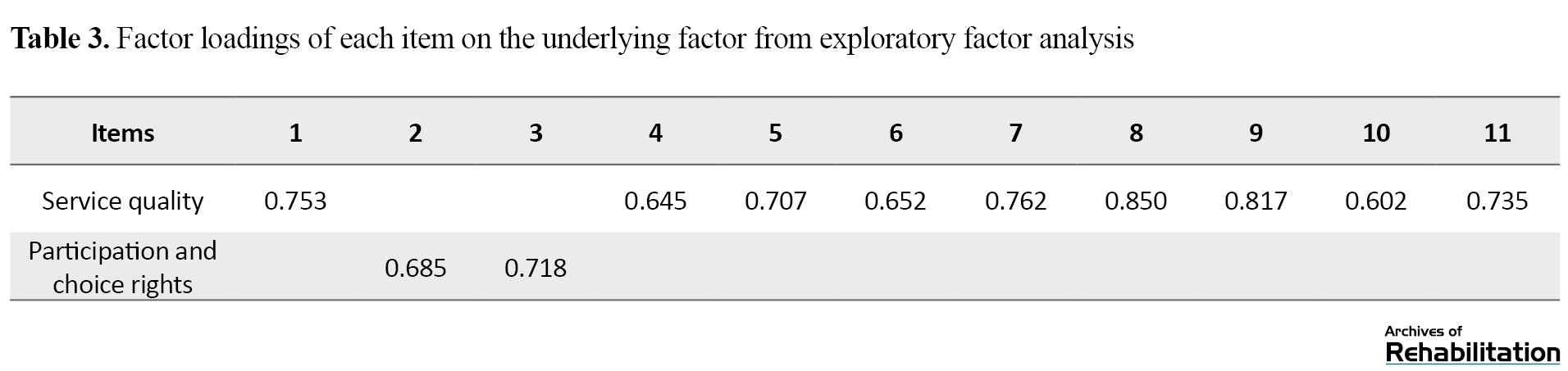

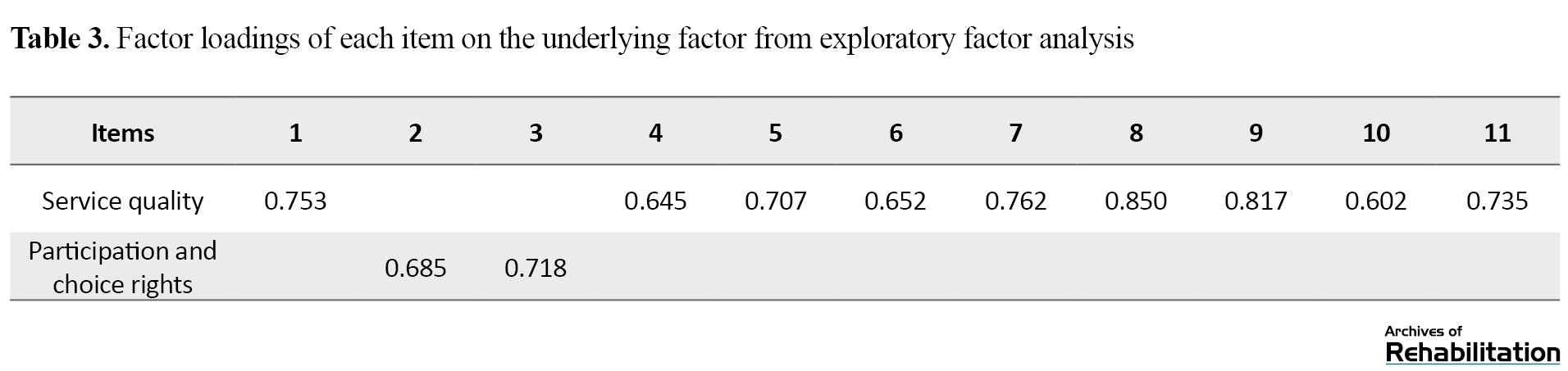

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted for this questionnaire with 11 questions. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure was calculated as 0.829, indicating that the data are sufficiently competent for conducting exploratory factor analysis. The Bartlett test of sphericity was also performed (value=644.63, df=55, P<0.001), indicating significant inter-item correlations. According to the results, this tool has two factors that explain 59.3% of the total variance (factor 1 explains 42.7% and factor 2 explains 16.5% of the variance). The items of each factor and their factor loadings are presented in Table 3.

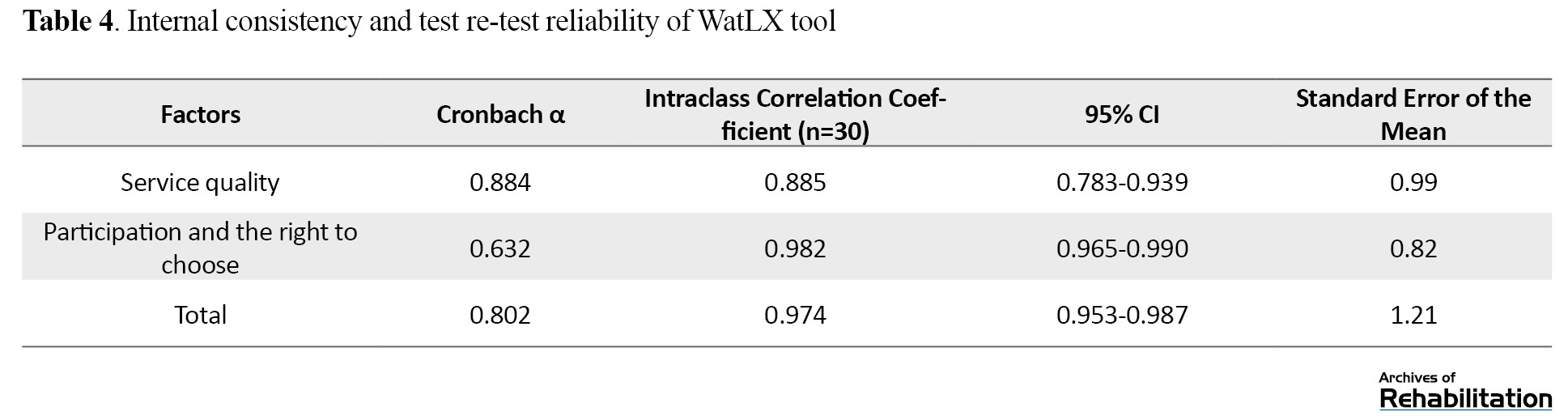

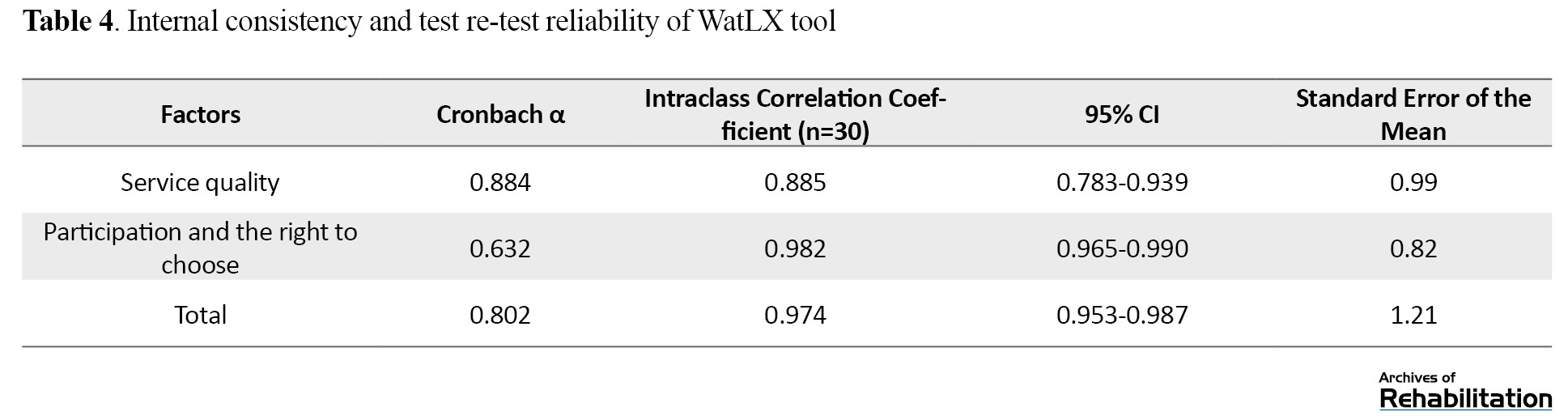

The values of Cronbach α and ICC for both factors and the total score in Table 4 indicate that this tool has good internal consistency and repeatability.

The standard error of the mean value is also small, indicating that the measurement error in this tool is minimal.

The Spearman correlation coefficient between the total score of the Persian version of WatLX and the total score of the Medrisk tool was 0.53, indicating a significant and direct correlation between these two tools. This implies that conceptually and content-wise, these two tools are aligned. However, due to their low correlation, the Persian version of WatLX can be used independently as a separate tool.

Discussion

The use of a standardized scale to assess the rehabilitation experience in individuals receiving rehabilitation services is a key step in patient-centered care models, as the measurement of patient-reported experiences correlates with better health system outcomes, and decision-makers seek cost-effective care delivery methods. This is increasingly observed in rehabilitation services.

Providers and regulators need reliable, cost-effective, and user-friendly tools that allow them to assess the quality of patient healthcare experiences as part of continuous quality assurance and reporting. In this study, the Cronbach α coefficient for the Persian version of the WatLX questionnaire was 0.802, indicating that this questionnaire maintains very good internal consistency similar to the original version.

Regarding the examination of the questionnaire’s repeatability, in the test and re-test sessions, and for the 11 questions of the Persian version of the questionnaire, an ICC value of 0.974 was obtained. The results obtained in this section are consistent with a study conducted in Canada in 2018, where the ICC values for the two questionnaires, Spectrum 7 Likert and 5 Likert WatLX were 0.880 and 0.827, respectively. Considering the ICC value, the Persian version of the WatLX tool has very good repeatability.

In the convergent validity assessment of the tool, the correlation between the scores obtained from the WatLX questionnaire and the scores of the Medrisk questionnaire was moderately significant. This finding indicates that conceptually and content-wise, these two tools are aligned. However, due to their low correlation, the Persian version of WatLX can be used independently as a separate tool.

The psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Medrisk tool were only evaluated for physiotherapy services by Abdolalizadeh et al. in 2017, and the correlations of Medrisk scores with physical therapy patient satisfaction questionnaire, physical therapy outpatient satisfaction survey, and perception of parents scale questionnaires, and a 14-item patient satisfaction questionnaire for physiotherapy were calculated. In that study, these correlations were found to be moderate. The current research shows that there was no significant linear relationship between the total scores the age of the participants and the number of rehabilitation sessions. Additionally, no significant difference was observed in the mean total scores of WatLX between women and men, but there was a significant difference in different education groups. As education levels increased, the mean total scores of WatLX decreased, meaning that individuals with lower education had a better experience of rehabilitation services. By comparing the mean total scores in two groups of private and public clinics and rehabilitation centers, it was found that individuals in private clinics had a better treatment experience. Considering the opinions and statements of the participants, it is suggested that factors such as greater changes in therapists during the treatment period in public centers, the fixed income of public center staff regardless of receiving rehabilitation services by participants, issues of interest in private centers, insufficient supervision of managers, and health supervision in public centers, service delivery, etc. may affect the experience of patients in different centers. This issue in its place requires further investigation and studies. Moreover, in the present study, there was no significant difference in the total scores of WatLX in different rehabilitation groups, including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, etc.

For clinical centers and clinics, it is recommended to assess the rehabilitation service experience of patients in government and private clinics using this questionnaire. Additionally, rehabilitation center managers can use this scale to have a comprehensive report on the rehabilitation service experience of their center’s clients. To provide better evidence regarding the rehabilitation experience of patients, accurate statistics can be made available to governmental decision-makers. This would enable the adoption of appropriate solutions, such as providing and enhancing the quantity and quality of necessary services for individuals in this category.

Conclusion

The Persian version of the WatLX tool has acceptable psychometric properties for assessing the experience of patients referring to rehabilitation centers and clinics. Therefore, the Persian version of this questionnaire, like its original version, is a tool with suitable performance and can be used in various therapeutic, clinical, and research fields. Study limitations include the participation of individuals over 18 years of age who received a rehabilitation services program. This points to the need for further studies in other age groups under 18 and families of young children receiving rehabilitation services. Moreover, due to the non-cooperation of some clinics or insufficient numbers of participants meeting the study criteria in certain clinics, the possibility of comparison between clinics in some geographical areas of Tehran City, Iran, was not provided.

For future research, considering the breadth of the concept of experience in rehabilitation services, it is suggested that this scale has the potential for validity and reliability for use in other communities, including families with disabled children. Further studies on the experience of rehabilitation services and the assessment of rehabilitation outcomes in other groups can also be considered.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

In this study, after stating the objectives and research method, individuals with entry criteria were approached, and informed consent was obtained. Individuals were informed that they could choose not to complete the tools at any time, and their information would remain confidential. Participation in this study would not disrupt their treatment process and rehabilitation services. The research process was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Welfare (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.050).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Kianoosh Abdi and Molood Paknia; Data collection: Molood Paknia; Data analysis: Samaneh Hosseinzadeh and Molood Paknia; Methodology, validation and writing: All authors; Supervision: Kianoosh Abdi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the professors of the Rehabilitation Management Department and other rehabilitation departments of the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Welfare who collaborated in the content validity assessment of the questionnaire. Also, the authors thank the rehabilitation centers participating in the study in Tehran City, Iran.

References

Patient-centered care is recognized as the top priority in the healthcare system. Achieving patient-centered care requires a more comprehensive understanding of patients’ experiences during their interactions with the healthcare and rehabilitation system [1]. With the aging population, an increasing number of individuals living with chronic disabilities require rehabilitation services, necessitating a novel approach to delivering and measuring services in diverse healthcare structures [2]. Rehabilitation care assists individuals with reduced functionality in achieving a desirable range of capabilities and skills [3]. There is growing evidence indicating that patient-reported actions correlate with better health outcomes, including increased treatment adherence, reduced hospital stays, enhanced presence, improved functional capacity, and fewer signs of depression in rehabilitation environments [4-6].

Most studies emphasizing the improvement of services evaluated negatively by patients emphasize the use of surveys. This approach focuses on improving service inputs and processes that identify patient needs and includes developmental activities that enhance service providers’ skills in recognizing and addressing patient concerns [7]. Measuring patient experience, especially in rehabilitation services, is suitable as the coordination and continuity of care often face challenges with medical complexities and the engagement of multiple healthcare specialists across the healthcare system [8]. Additionally, patients requiring rehabilitation care often need more than one type of service, provided by different providers simultaneously and multiple times over time [9]. As more providers are involved, patients’ experiences in the received care quality will differ [10]. Doyel et al. identified patient experience as a key pillar in improving the quality of healthcare, demonstrating a positive correlation between patient health and clinical clinic efficiency [11]. Understanding the patient experience is a crucial step in moving toward high-quality patient-centered care [12]. While there is a substantial and growing body of literature on tools measuring patient experiences [13], there is limited research done on measuring patient experiences in rehabilitation care [13]. The definitional ambiguity between patient experience and patient satisfaction has made developing a valid and reliable instrument challenging. Patient experience is a multidimensional structure encompassing a wide spectrum of patient interactions with the healthcare system [12]. Jenkinson et al. define experience as what has happened to the patient in the face of health and describe satisfaction as the patient’s evaluation of the encounter [14]. Slade and Keting suggest that the patient satisfaction questionnaire concerns general questions related to care providers and researchers, while the patient experience questionnaire relates to patients and assesses healthcare providers’ expertise in dealing with healthcare encounters [15].

On the other hand, patient satisfaction indicates an individual’s pleasure or disappointment, relatively resulting from the individual’s evaluation of the service against personal values and expectations [16]. The degree and direction of the gap between patient experience and expectations, preferences, and values determine patient satisfaction. If a patient expresses satisfaction with services, it is assumed that they were satisfied after using it and that their expectations have been met. Some have referred to this area as the tolerance zone, acknowledging a range where patients report their satisfaction due to various moderating effects of expectations and preferences. It is also possible that each service encounter creates a different history due to the nature and essence of that service. Therefore, patient satisfaction is less tangible in actual representation [17], and patient experience is instrumental in identifying areas for useful and supportive improvement [14]. Accordingly, the patient’s experience, conceptually, differs from the patient’s satisfaction, requiring a different framework of understanding before it can serve as a performance metric (Figure 1) [12]. As the healthcare system moves toward integrating service delivery across structures and providers in geographical regions, regulatory and budgetary institutions have begun examining how the overall patient experience is measured within the healthcare system and service-providing organizations [18]. All these factors lead to the question of how can financial providers of the healthcare system and regulatory organizations effectively oversee the quality of the patient experience in a unified rehabilitative care system [12]. Providers and organizations can use the Waterloo Wilfrid Laurier University rehabilitation patient experience instrument (WatLX) to assess and report the quality of healthcare experiences and patient perspectives as part of their quality service audits and inspections. Considering the absence of standardized tools in Iran to assist managers and service providers in identifying quality improvement areas from the patients’ perspective in various rehabilitation services, the localization of a reliable and sustainable tool like WatLX is suitable for measuring the rehabilitative service experience within the Iranian community.

Materials and Methods

Study participants

This psychometric study was conducted in 2023. The study population consisted of adults aged 18 and above who visited physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy centers and clinics in Tehran City, Iran, to receive one of the rehabilitative services, such as cardiac, musculoskeletal, neurological, stroke, pulmonary, or speech therapy. Sampling was done systematically based on the available sampling method. Initially, rehabilitation centers, both private and public, in Tehran City, Iran, were considered in five geographical zones as follows: North, south, east, west, and center. A total of 10 rehabilitation centers were selected, including Rafideh Hospital, Asma Rehabilitation Center, Haji Baqeri Physiotherapy Center, Omid Shargh Occupational and Speech Therapy Center, Nazam Mafi Rehabilitation Center, Bahrad Physiotherapy Center, Darya Speech and Occupational Therapy Center, Raad Al-Ghadir Rehabilitation Center, Dastan Occupational Therapy Center, and Brain and Cognition Clinic. These centers collaborated and provided the setting for participant recruitment and data collection. Given that a sample size of 5 to 10 individuals per item is sufficient for psychometric studies, considering the 10 questions in the mentioned questionnaire, a minimum of 100 samples was targeted, and ultimately, 115 participants completed the questionnaire. The inclusion criteria were adults above 18 years old with either a healthy cognitive level or mild cognitive impairment (scoring more than 6 on the abbreviated mental test [AMT] questionnaire).

Study instruments

Demographic questionnaire

A demographic questionnaire collected the data on participants’ age, gender, education level, initial conditions, and issues for receiving rehabilitation services, duration of rehabilitation services (number of sessions), type of rehabilitation service, and the name of the rehabilitation clinic and center. All the details were gathered through the WatLX questionnaire.

Abbreviated mental test

AMT was used to assess participants’ cognitive levels as an entry criterion. The Persian version of the AMT has been shown to have good validity and reliability in various studies.

WatLX

The WatLX questionnaire comprises a set of simple questions designed for management in standing rehabilitation centers, examining the rehabilitation care experience in standing patients. Developed in Canada by a team of researchers from the University of Waterloo and Wilfrid Laurier University, led by Josephine McMurray and Paul Stole, in collaboration with the Rehabilitative Care Alliance, the English version of WatLX consists of 10 items and one question about expressing the overall patient experience. The questions cover various aspects, such as courtesy and kindness, decision-making, family/friendliness, environmental conditions, pain goals, safety information, expectations, and recommendations. The participants rate each item based on a 7-point Likert scale (completely disagree=1 to completely agree=7), and the total score is the sum of these ten questions. The final question about the overall experience is rated based on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 10. The reliability of this tool has been tested with over 1000 patient participants. No statistically significant difference was found in the mean WatLX response between men and women. There was no significant correlation between age and WatLX total score, and no significant difference in WatLX total score was observed based on the patient’s medical condition.

Persian version of Medrisk instrument for measuring

The Persian version of the Medrisk instrument for measuring was designed in 2005 by Betty et al. and consists of 20 items, of which 10 items were related to the therapist-patient relationship (internal factor), 8 were related to service aspects such as the admission process and secretary behavior (external factor), and 2 items were related to overall satisfaction. This brief and useful questionnaire assesses patient satisfaction with physical therapy services for musculoskeletal problems. In a study by Abdolalizadeh, the Persian version of this tool showed good internal consistency and reliability. The Persian version of the WatLX questionnaire, used in this psychometric study, provides a reliable and culturally adapted tool for assessing the experience of standing rehabilitation care in Iranian patients. The study employed rigorous sampling and inclusion criteria, ensuring the validity and reliability of the data collected through WatLX and other supporting tools, such as AMT and MedRisk Instrument for measuring.

Study implementation method

Initially, permission to use the tool was obtained from the questionnaire designer, Professor Josephine McMurray. The translation process started with the English-to-Persian translation and back-translation. The English-to-Persian translation was done by a translator proficient in English and Persian. Subsequently, the reverse translation to English was performed by another translator proficient in both languages, without access to the original questionnaire. The English version was sent to the original author for confirmation after the translated questionnaire was validated for consistency and alignment with the original version by the corresponding author. Content validity was assessed through the Lawshe method with the participation of 14 experts and faculty members specializing in physical medicine and rehabilitation, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and rehabilitation management. Items were evaluated for relevance and necessity. The content validity ratio (CVR) was calculated, considering a minimum acceptable score of 0.51 for 14 experts. Based on the results, one question was removed, and three additional questions were added. In the second step, 13 experts completed a second round of evaluation, and one of the added questions was eliminated based on the minimum CVR score. The open-ended questions section was also removed.

Face validity was assessed through qualitative content review by 10 participants from the study population. No issues were identified in this phase, confirming the face and content validity of 11 questions. To examine the tool’s reliability, collaboration was established with rehabilitation centers across Tehran City, Iran. Sampling was done with the coordination of managers and officials of these centers.

Individuals based on the inclusion criteria were approached, and informed consent was obtained. The participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information, and they were informed that their participation would not disrupt their treatment process. The participants completed the WatLX questionnaire, and 50 participants also completed the MRPS questionnaire for convergent validity assessment. A subset of 39 patients completed the WatLX questionnaire again after two weeks for test re-test reliability assessment.

Data analysis

The content validity was assessed using the CVR index. The minimum acceptable value for CVR, based on the Lawshe method, was equal to 0.51. The internal consistency was evaluated using Cronbach α for item homogeneity, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), and the standard error of measurement for test re-test reliability. The convergent validity was assessed through Pearson correlation coefficients between WatLX and MedRisk Instrument for Measuring scores. Exploratory factor analysis was conducted using the principal component method and Equamax rotation to explore the underlying structure of the questionnaire after changes in questions. This detailed methodology provides a comprehensive approach to the translation, adaptation, and validation of the WatLX questionnaire for assessing the experience of standing rehabilitation care in Iranian patients.

Results

The first and second stages of content validity assessment for the tool have been completed. Overall, one question was added to the existing items of this tool, and the content and face validity of this question was confirmed by experts, the tool designer, and the surveyed community (Table 1).

A total of 115 participants took part in the study. The Mean±SD age of the participants was 42.8±16.7 years. Meanwhile, 53.9% of the participants were female. Among the various disorders, participants with low back pain, hand surgery, and spinal cord injury had the highest number. The most common type of service received was physical therapy. Nearly 60% of the participants were from government clinics. The majority of participants had a diploma-level education (47%) (Table 2).

The Shapiro-Wilk test indicated that the total score of the WatLX tool in the sample of 115 individuals does not follow a normal distribution (P<0.05). However, the total score of the Medrisk tool in the sample of 50 individuals follows a normal distribution (P<0.05).

Exploratory factor analysis was conducted for this questionnaire with 11 questions. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure was calculated as 0.829, indicating that the data are sufficiently competent for conducting exploratory factor analysis. The Bartlett test of sphericity was also performed (value=644.63, df=55, P<0.001), indicating significant inter-item correlations. According to the results, this tool has two factors that explain 59.3% of the total variance (factor 1 explains 42.7% and factor 2 explains 16.5% of the variance). The items of each factor and their factor loadings are presented in Table 3.

The values of Cronbach α and ICC for both factors and the total score in Table 4 indicate that this tool has good internal consistency and repeatability.

The standard error of the mean value is also small, indicating that the measurement error in this tool is minimal.

The Spearman correlation coefficient between the total score of the Persian version of WatLX and the total score of the Medrisk tool was 0.53, indicating a significant and direct correlation between these two tools. This implies that conceptually and content-wise, these two tools are aligned. However, due to their low correlation, the Persian version of WatLX can be used independently as a separate tool.

Discussion

The use of a standardized scale to assess the rehabilitation experience in individuals receiving rehabilitation services is a key step in patient-centered care models, as the measurement of patient-reported experiences correlates with better health system outcomes, and decision-makers seek cost-effective care delivery methods. This is increasingly observed in rehabilitation services.

Providers and regulators need reliable, cost-effective, and user-friendly tools that allow them to assess the quality of patient healthcare experiences as part of continuous quality assurance and reporting. In this study, the Cronbach α coefficient for the Persian version of the WatLX questionnaire was 0.802, indicating that this questionnaire maintains very good internal consistency similar to the original version.

Regarding the examination of the questionnaire’s repeatability, in the test and re-test sessions, and for the 11 questions of the Persian version of the questionnaire, an ICC value of 0.974 was obtained. The results obtained in this section are consistent with a study conducted in Canada in 2018, where the ICC values for the two questionnaires, Spectrum 7 Likert and 5 Likert WatLX were 0.880 and 0.827, respectively. Considering the ICC value, the Persian version of the WatLX tool has very good repeatability.

In the convergent validity assessment of the tool, the correlation between the scores obtained from the WatLX questionnaire and the scores of the Medrisk questionnaire was moderately significant. This finding indicates that conceptually and content-wise, these two tools are aligned. However, due to their low correlation, the Persian version of WatLX can be used independently as a separate tool.

The psychometric properties of the Persian version of the Medrisk tool were only evaluated for physiotherapy services by Abdolalizadeh et al. in 2017, and the correlations of Medrisk scores with physical therapy patient satisfaction questionnaire, physical therapy outpatient satisfaction survey, and perception of parents scale questionnaires, and a 14-item patient satisfaction questionnaire for physiotherapy were calculated. In that study, these correlations were found to be moderate. The current research shows that there was no significant linear relationship between the total scores the age of the participants and the number of rehabilitation sessions. Additionally, no significant difference was observed in the mean total scores of WatLX between women and men, but there was a significant difference in different education groups. As education levels increased, the mean total scores of WatLX decreased, meaning that individuals with lower education had a better experience of rehabilitation services. By comparing the mean total scores in two groups of private and public clinics and rehabilitation centers, it was found that individuals in private clinics had a better treatment experience. Considering the opinions and statements of the participants, it is suggested that factors such as greater changes in therapists during the treatment period in public centers, the fixed income of public center staff regardless of receiving rehabilitation services by participants, issues of interest in private centers, insufficient supervision of managers, and health supervision in public centers, service delivery, etc. may affect the experience of patients in different centers. This issue in its place requires further investigation and studies. Moreover, in the present study, there was no significant difference in the total scores of WatLX in different rehabilitation groups, including physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, etc.

For clinical centers and clinics, it is recommended to assess the rehabilitation service experience of patients in government and private clinics using this questionnaire. Additionally, rehabilitation center managers can use this scale to have a comprehensive report on the rehabilitation service experience of their center’s clients. To provide better evidence regarding the rehabilitation experience of patients, accurate statistics can be made available to governmental decision-makers. This would enable the adoption of appropriate solutions, such as providing and enhancing the quantity and quality of necessary services for individuals in this category.

Conclusion

The Persian version of the WatLX tool has acceptable psychometric properties for assessing the experience of patients referring to rehabilitation centers and clinics. Therefore, the Persian version of this questionnaire, like its original version, is a tool with suitable performance and can be used in various therapeutic, clinical, and research fields. Study limitations include the participation of individuals over 18 years of age who received a rehabilitation services program. This points to the need for further studies in other age groups under 18 and families of young children receiving rehabilitation services. Moreover, due to the non-cooperation of some clinics or insufficient numbers of participants meeting the study criteria in certain clinics, the possibility of comparison between clinics in some geographical areas of Tehran City, Iran, was not provided.

For future research, considering the breadth of the concept of experience in rehabilitation services, it is suggested that this scale has the potential for validity and reliability for use in other communities, including families with disabled children. Further studies on the experience of rehabilitation services and the assessment of rehabilitation outcomes in other groups can also be considered.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

In this study, after stating the objectives and research method, individuals with entry criteria were approached, and informed consent was obtained. Individuals were informed that they could choose not to complete the tools at any time, and their information would remain confidential. Participation in this study would not disrupt their treatment process and rehabilitation services. The research process was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Welfare (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1401.050).

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Kianoosh Abdi and Molood Paknia; Data collection: Molood Paknia; Data analysis: Samaneh Hosseinzadeh and Molood Paknia; Methodology, validation and writing: All authors; Supervision: Kianoosh Abdi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to the professors of the Rehabilitation Management Department and other rehabilitation departments of the University of Rehabilitation Sciences and Social Welfare who collaborated in the content validity assessment of the questionnaire. Also, the authors thank the rehabilitation centers participating in the study in Tehran City, Iran.

References

- Grondahl VA, Wilde-Larsson B, Karlsson I, Hall-Lord ML. Patients’ experiences of care quality and satisfaction during hospital stay: a qualitative study. European Journal for Person Centered Healthcare. 2013; 1(1):185-92. [DOI:10.5750/ejpch.v1i1.650]

- Landry MD, Jaglal S, Wodchis W, Cott CA, Gordon M, Tong S, et al. Forecasting the demand for rehabilitation services across ontario’s continuum of care: Final report. Toronto: Toronto Rehabilitation Institute; 2006. [Link]

- Meyer T, Gutenbrunner C, Kiekens C, Skempes D, Melvin JL, Schedler K, et al. ISPRM discussion paper: Proposing a conceptual description of health-related rehabilitation services. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2014; 46(1):1-6. [DOI:10.2340/16501977-1251] [PMID]

- Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KD, Franks P. The cost of satisfaction: A national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2012; 172(5):405-11. [DOI:10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662] [PMID]

- Tsai TC, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Patient satisfaction and quality of surgical care in US hospitals. Annals of Surgery. 2015; 261(1):2-8. [DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000000765] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ali S, Chessex C, Bassett-Gunter R, Grace SL. Patient satisfaction with cardiac rehabilitation: Association with utilization, functional capacity, and heart-health behaviors. Patient Preference and Adherence. 2017; 11:821-30. [DOI:10.2147/PPA.S120464] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dibbelt S, Schaidhammer M, Fleischer C, Greitemann B. Patient-doctor interaction in rehabilitation: The relationship between perceived interaction quality and long-term treatment results. Patient Education and Counseling. 2009; 76(3):328-35. [DOI:10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.031] [PMID]

- Toscan J, Mairs K, Hinton S, Stolee P; InfoRehab Research Team. Integrated transitional care: Patient, informal caregiver and health care provider perspectives on care transitions for older persons with hip fracture. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2012; 12:e13. [DOI:10.5334/ijic.797] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Glenny C, Stolee P, Sheiban L, Jaglal S. Communicating during care transitions for older hip fracture patients: Family caregiver and health care provider's perspectives. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2013; 13:e044. [DOI:10.5334/ijic.1076] [PMID] [PMCID]

- McLeod J, McMurray J, Walker JD, Heckman GA, Stolee P. Care transitions for older patients with musculoskeletal disorders: Continuity from the providers' perspective. International Journal of Integrated Care. 2011; 11:e014. [DOI:10.5334/ijic.555] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D. A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2013; 3(1):e001570. [DOI:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001570] [PMID] [PMCID]

- McMurray J, McNeil H, Lafortune C, Black S, Prorok J, Stolee P. Measuring patients' experience of rehabilitation services across the care continuum. Part II: Key dimensions. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2016; 97(1):121-30. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.08.408] [PMID]

- Hills R, Kitchen S. Satisfaction with outpatient physiotherapy: A survey comparing the views of patients with acute and chronic musculoskeletal conditions. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 2007; 23(1):21-36. [DOI:10.1080/09593980601023705] [PMID]

- Jenkinson C, Coulter A, Bruster S, Richards N, Chandola T. Patients' experiences and satisfaction with health care: Results of a questionnaire study of specific aspects of care. Quality & Safety in Health Care. 2002; 11(4):335-9. [DOI:10.1136/qhc.11.4.335] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Slade SC, Keating JL. Measurement of participant experience and satisfaction of exercise programs for low back pain: A structured literature review. Pain Medicine. 2010; 11(10):1489-99. [DOI:10.1111/j.1526-4637.2010.00951.x] [PMID]

- Delanian Halsdorfer N, Blasquez J, Bensoussan L, Gentile S, Collado H, Viton JM, et al. An assessment of patient satisfaction for a short-stay program in a physical and rehabilitation medicine day hospital. Annals of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2011; 54(4):236-47. [DOI:10.1016/j.rehab.2011.04.001] [PMID]

- Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: A review of issues and concepts. Social Science & Medicine. 1997; 45(12):1829-43. [DOI:10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00128-7] [PMID]

- McMurray J, McNeil H, Lafortune C, Black S, Prorok J, Stolee P. Measuring patients' experience of rehabilitation services across the care continuum. Part I: A systematic review of the literature. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2016; 97(1):104-20. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2015.08.407] [PMID]

- Bakhtiyari F, Foroughan M, Fakhrzadeh H, Nazari N, Najafi B, Alizadeh M, et al. [Validation of the persian version of abbreviated mental test (AMT) in elderly residents of Kahrizak charity foundation (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Diabetes and Metabolism. 2014; 13(6):487-94. [Link]

- Foroughan M, Wahlund LO, Jafari Z, Rahgozar M, Farahani IG, Rashedi V. Validity and reliability of abbreviated mental test score (AMTS) among older Iranian. Psychogeriatrics. 2017; 17(6):460-5. [DOI:10.1111/psyg.12276] [PMID]

- McMurray J, McNeil H, Gordon A, Elliott J, Stolee P. Psychometric testing of a rehabilitative care patient experience instrument. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2018; 99(9):1840-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2018.04.028] [PMID]

- Abdolalizadeh M, Ghodrati M, Saeedi A, Kamyab H, Nejad ARR. Translation, reliability assessment, and validation of the persian version of medrisk instrument for measuring patient satisfaction with physical therapy care (20-item MRPS). Journal of Modern Rehabilitation. 2021; 15(2):93-104. [DOI:10.18502/jmr.v15i2.7730]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Rehabilitation Management

Received: 19/06/2023 | Accepted: 27/02/2024 | Published: 1/07/2024

Received: 19/06/2023 | Accepted: 27/02/2024 | Published: 1/07/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |