Volume 25, Issue 1 (Spring 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(1): 48-71 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mirmohammadi F, Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi M. The Effect of Acceptance and Commitment Group Therapy on Emotional Maturity in Female Adolescents With Visual Impairment. jrehab 2024; 25 (1) :48-71

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3287-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3287-en.html

1- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,mpmrtajrishi@gmail.com

2- Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, School of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 2371 kb]

(904 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (2412 Views)

Full-Text: (1126 Views)

Introduction

Visual impairment is one of the most critical and common disabilities; 285 million people worldwide have a visual impairment, of which 39 million are blind, and 246 million are visually impaired [1]. All over the world, visual impairment ranks 14th among other physical injuries [2]. In Iran, the number of blind and partially sighted people is reported to be approximately 180000 [3]. Visually impaired people are deprived of the opportunities of face-to-face observation and contact and have a different perception of the world. This issue can lead to emotional and social problems [4].

Psychological, physical, social, and emotional maturity is one of adolescence’s main challenges, accompanied by dramatic changes in adolescence. Nevertheless, the recent challenges become worse when the adolescent has a disability in addition to puberty changes [5]. During emotional maturity, a person continuously tries to achieve emotional and psychological health [6]. Emotional maturity consists of 7 components: Intimacy, empathy, self-expression, psychological stability, independence, psychological balance, and the ability to consider emotional issues [7].

As adolescents grow, they are supported by their parents, can achieve emotional stability [8], and learn how to expand interpersonal and intra-personal relationships [9]. Poor emotional maturity leads to ineffective coping methods [10], and higher emotional maturity leads to problem-oriented and more helpful coping strategies [11]. The most prominent sign of emotional maturity is the ability to tolerate stress and indifference [12] to some stimuli that negatively impact people and cause them to become bored or emotional [13]. Emotional stability (an essential component of emotional maturity) is one of the main determinants of personality patterns that affect adolescent development. People with emotional stability can postpone the satisfaction of their needs, tolerate failure, believe in long-term planning, and change their expectations according to different situations [14].

Due to poor eyesight, people with visual impairments probably struggle to form secure bonds with others and adapt to challenging situations [15]. During adolescence, they have deficient emotional maturity, less ability to adjust emotionally and socially to the environment [16], and more academic problems [17]. In addition, they experience more behavioral problems, psychological disorders [18], and emotional problems compared to their normal peers [19]. However, some findings indicate no difference between the prevalence of psychological issues and depression in adolescents with visual impairment compared to normal adolescents [20]. Those adolescents with vision impairment who cannot transition from childhood to youth properly do not achieve an integrated identity of themselves. Therefore, they experience various problems, including suppression of emotions and feelings, isolation, defensive reactions, and blaming themselves or others. Even severe symptoms of depression and anxiety have been reported in visually impaired girls more than boys [19]. Visual impairment in these people causes cognitive, emotional, social, and movement problems [17]. The delay in the skills mentioned above leads to a gap in social development and deprives adolescents of the possibility of healthy interaction with other people. As a result, adolescents have problems satisfying their natural needs [21].

Despite emotional problems in visually impaired adolescents [22], the use of therapeutic interventions to provide emotional management and mental health in visually impaired teenagers can prevent the occurrence of many emotional and psychological problems and disturbances in the forthcoming years [23]. One of the preventive approaches to the occurrence of emotional issues and managing emotions in people is acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Demehri et al. presented ACT in the early 1980s. It is one of the third-wave behavioral therapies [24]. The ACT approach is based on the philosophy of realistic conceptualism and emphasizes context’s role in understanding nature and events. The main goal of therapy is to help people effectively manage the pains, sufferings, and tensions they have experienced, communicate with the present moment, increase their flexibility, and change their behavior to achieve valuable goals [25]. One of the main components of ACT is identifying and recognizing the boundaries that prevent people from living a desirable life [26]. The six essential processes in ACT are acceptance, being in the present moment, specifying values, cognitive diffusion, commitment to action, and considering self as content for change. The purpose of all the mentioned processes is to confront the person with the experiences of the present time so that he can eliminate the connection between negative thoughts and previous experiences, accept the actual relationships between thoughts and experiences, and separate his earlier experiences from the fake world, and achieve goals that have higher value and stick to his values in life [27].

ACT uses “values” to guide intervention strategies, improve life satisfaction, and increase motivation [28]. Behavioral principles, along with ACT, help people to act based on their values. Performing these important and purposeful behaviors may be considered a form of emotion regulation even when experiencing intense emotions [29]. When thoughts and feelings keep a person from maintaining behaviors in accordance with values, the principles of acceptance and commitment therapy are considered. Although ACT has been designed for adults, it applies to the clinical population of adolescents, and its principles are the same. Still, its exercises, examples, and metaphors are adapted to the conditions of adolescents [30].

Many findings of previous studies indicate the effect of ACT on the mental health of adolescents [31], reducing psychological distress [32], reducing physical aggression [33], improving emotional regulation [34], reducing depression and increasing adaptation [35], regulating mood states [36], reducing obsessive-compulsive disorder [37], improving resilience and optimism [38], and improving self-esteem [39]. However, according to the researcher’s investigation, the previous studies have not explored the effect of ACT on the emotional maturity of visually impaired adolescents.

In general, the components of ACT, including values, may be beneficial for adolescents because they are in a transitional period to achieve an integrated identity [30]. However, ACT has not yet been tested as a preventive program in a non-clinical adolescent population. The results of the clinical samples show that ACT is effective as an emotion regulation strategy. Therefore, the need to deal with it as a preventive program, especially during adolescence, is more felt. Consequently, it is essential to administer research that shows how acceptance and commitment therapy can be used in real-life situations and non-clinical samples. So, based on the research findings, the ACT approach can be applied to the normal population [40]. For this reason, the present research investigated whether group ACT affects emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adjustment, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment.

Materials and Methods

The current quasi-experimental employed a pre-test and post-test design with a control group, which was conducted with an 8-week follow-up. An educational complex special for the 14 to 18 years old visually-impaired females was selected in Tehran City, Iran. The study was conducted in the 2020-2021 academic year. The sample size was determined considering the type 1 error of 0.05, test power of 0.84, σ=2.13, 2µ=10.3, 1µ=0.12, and a possible dropout of at least 28 people (14 in each group). The samples were randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups.

Data collection tools

Emotional maturity scale

The current study collected information using the emotional maturity scale (EMS). Bal prepared this self-report scale. It has 48 items and covers five areas: Emotional stability (10 items), emotional progression (10 items), social adjustment (10 items), personality integration (10 items), and independence (8 items) [41]. This scale is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 to 5 for each option: Very much, a lot, uncertain, probably, and never, respectively. A person’s high score (>180) indicates a problem in emotional maturity and its related components. The reliability values of the whole scale were 0.75 and 0.64, using the test re-test method and the internal consistency, respectively. The reliability values for emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence were 0.75, 0.63, 0.58, 0.86, and 0.42, respectively [42].

The present study used the test re-test method with 10 visually impaired teenagers at a 4-week interval to check the EMS’s reliability. The Pearson correlation coefficient calculated for the reliability of the whole scale was 0.90. Also, the coefficients were 0.99, 0.98, 0.97, 0.90, and 0.85 for emotional stability, emotional progression, social adjustment, personality integration, and independence, respectively. In addition, the internal correlation coefficient for the whole emotional maturity scale was 0.85, indicating an excellent coefficient for the scale.

Study procedure

After obtaining the code of ethics and the letter of representation from the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, the permission received from the Organization of Exceptional Education in Tehran City for referring to one of the educational complexes special for visually impaired females in the academic year 2020-2021. At first, the research objectives were described and explained to the complex authorities, and the volunteers signed a written consent form to cooperate in the study. Then, 82 teenagers were individually evaluated using the EMS. The research assistant read the emotional maturity scale for each adolescent individually and recorded their responses to each item. After scoring the scale by the researcher, 33 people who got a score of 180 or higher were included in the study according to the inclusion criteria. These criteria were having visual impairment from low vision to total blindness, having normal intelligence, not suffering from hearing impairment, behavioral problems, and multiple disabilities based on their school file. The exclusion criteria were the absence of more than two sessions from ACT or participating simultaneously or for the last six months in group ACT sessions. Twenty-eight adolescents were randomly selected and matched based on age and educational level. Then, they were assigned to experimental and control groups (14 people in each group). Considering the condition of visual impairment in participants and to increase the effectiveness of ACT in small groups [43], the experimental group was divided into two subgroups of 7 people, and each subgroup attended 10 ACT group sessions for two months (once a week; each session lasted 60 minutes) after the curriculum time of the complex. At the same time, the control group only participated in make-up empowering sessions in the complex. Therapeutic sessions were held in a separate room in the complex (7 people in the room separately and on different days). The researcher’s assistant implemented the EMS, but the researcher (trained in the ACT workshop and certified) scored the EMS and administered the therapeutic sessions. In addition, none of the participants or the research assistant were aware that the questionnaire belonged to the people of the experimental or control groups.

The outline of the ACT protocol was prepared based on the content of the books “acceptance and commitment therapy” [44] and “case conceptualization in acceptance & commitment therapy” [45]. Using mindfulness, the Gestalt technique, and one of the previous studies in this field [46], we tried to adjust each method according to the conditions of visually impaired teenagers and follow each therapeutic session’s goals. Also, the content of the program was flexible for the adolescents. The design of the therapeutic protocol, examples, and metaphors used in the sessions were adapted according to the characteristics of visually impaired teenagers and the opinion of the experts for educating blind people. The intervention rating profile questionnaire (developed by Martens et al. in 1985) was used to measure the social validity of the protocol. This questionnaire has 15 questions rated from 1 to 6 for “completely agree” to “completely disagree”. The range of total scores is between 15 and 90. A score higher than 52 indicates acceptance of the intervention protocol [47]. The stability of the questionnaire was found between 0.84 and 0.98 through internal consistency, and the social validity score in the present study was 71, which was acceptable. All participants were re-evaluated using the EMS after the last acceptance and commitment group therapy session and then 8 weeks later. During the therapeutic sessions, the experimental group lost two people due to their unwillingness to continue working with the researcher. To comply with ethical considerations, the content of the ACT was briefly held for the control group in 3 sessions after the end of the research process and follow-up period. Also, the teenagers were free to refuse to continue working with the researcher whenever they wanted; the researcher was also committed to maintaining the privacy and personal and confidential information of the teenagers. Participation in the research had no additional costs or possible losses for the participants. The data obtained from the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up were analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test (to check normality), Levene’s test (to determine the homogeneity of variances), M. Box test (to determine the homogeneity of the line slope), multivariate analysis of covariance, and the dependent t-test.

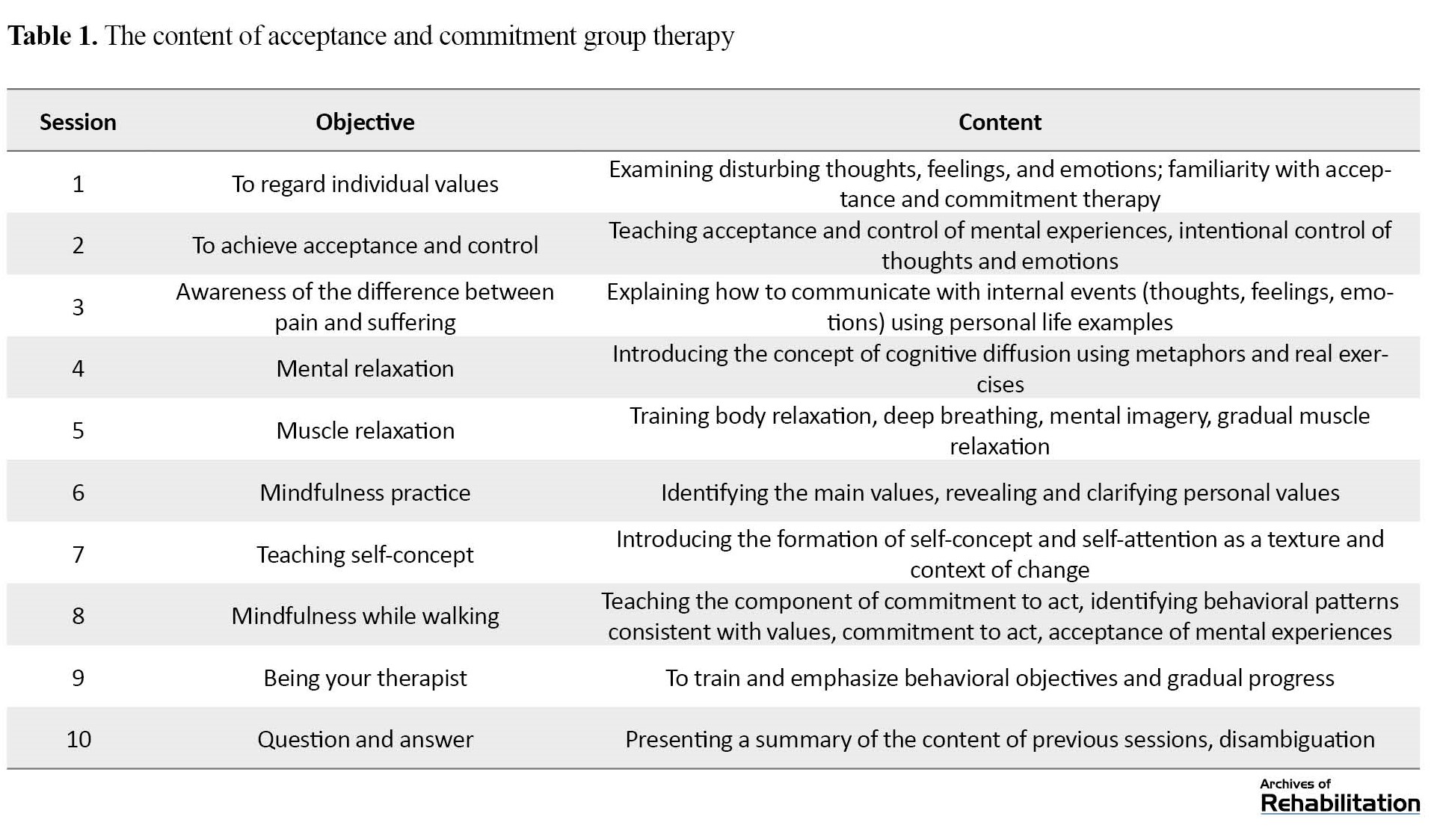

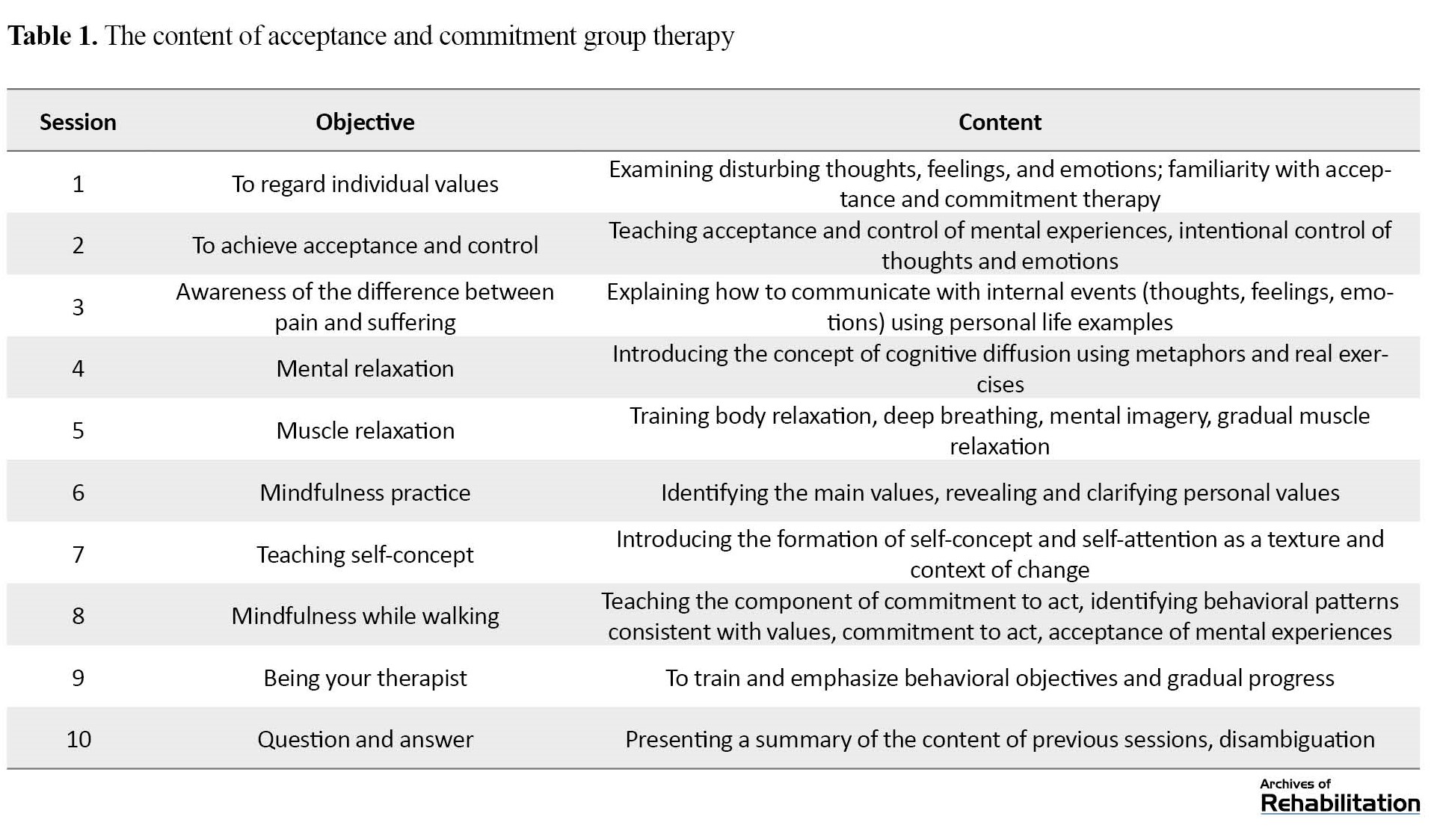

The content of the ACT protocol by sessions is presented in Table 1.

Results

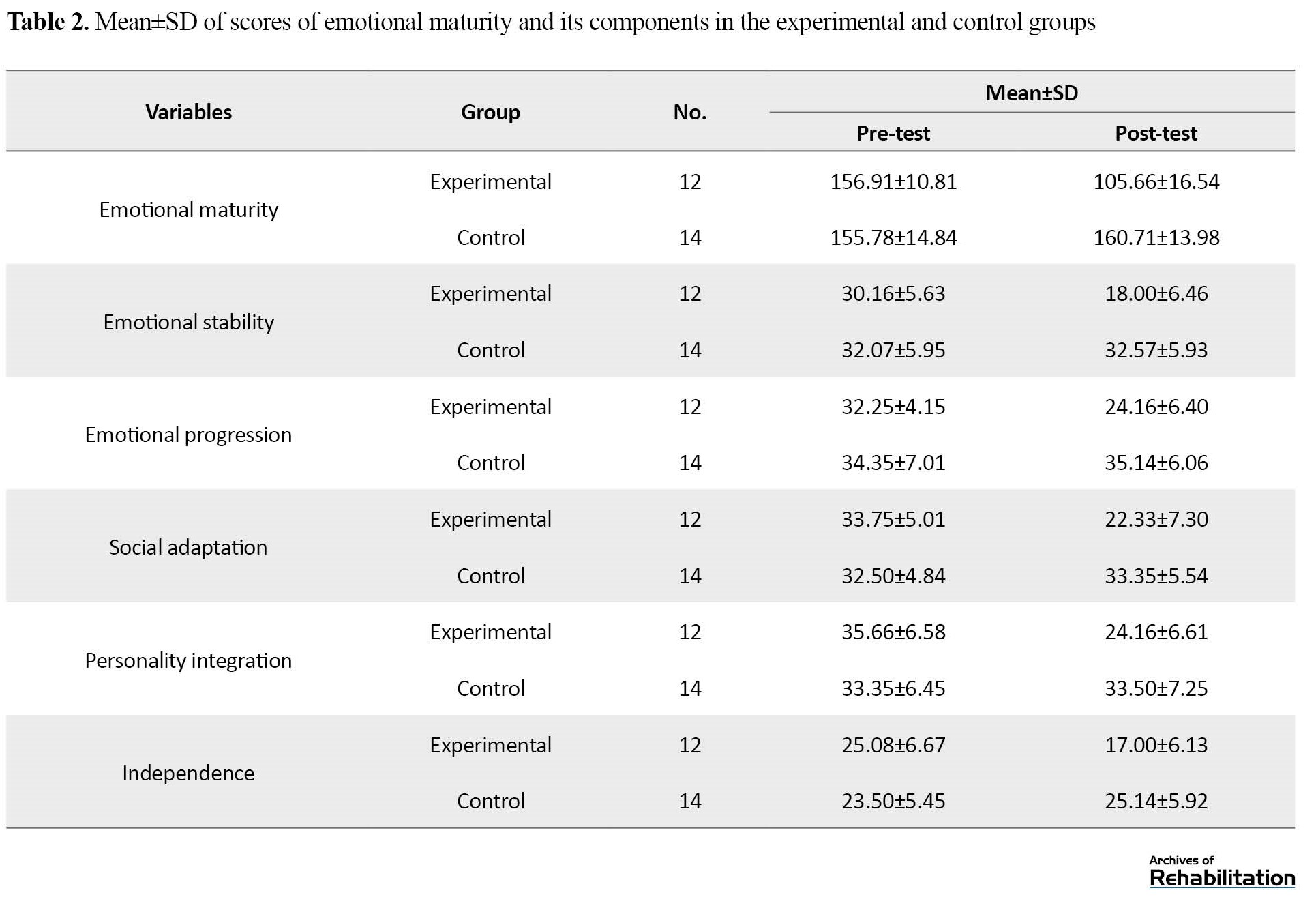

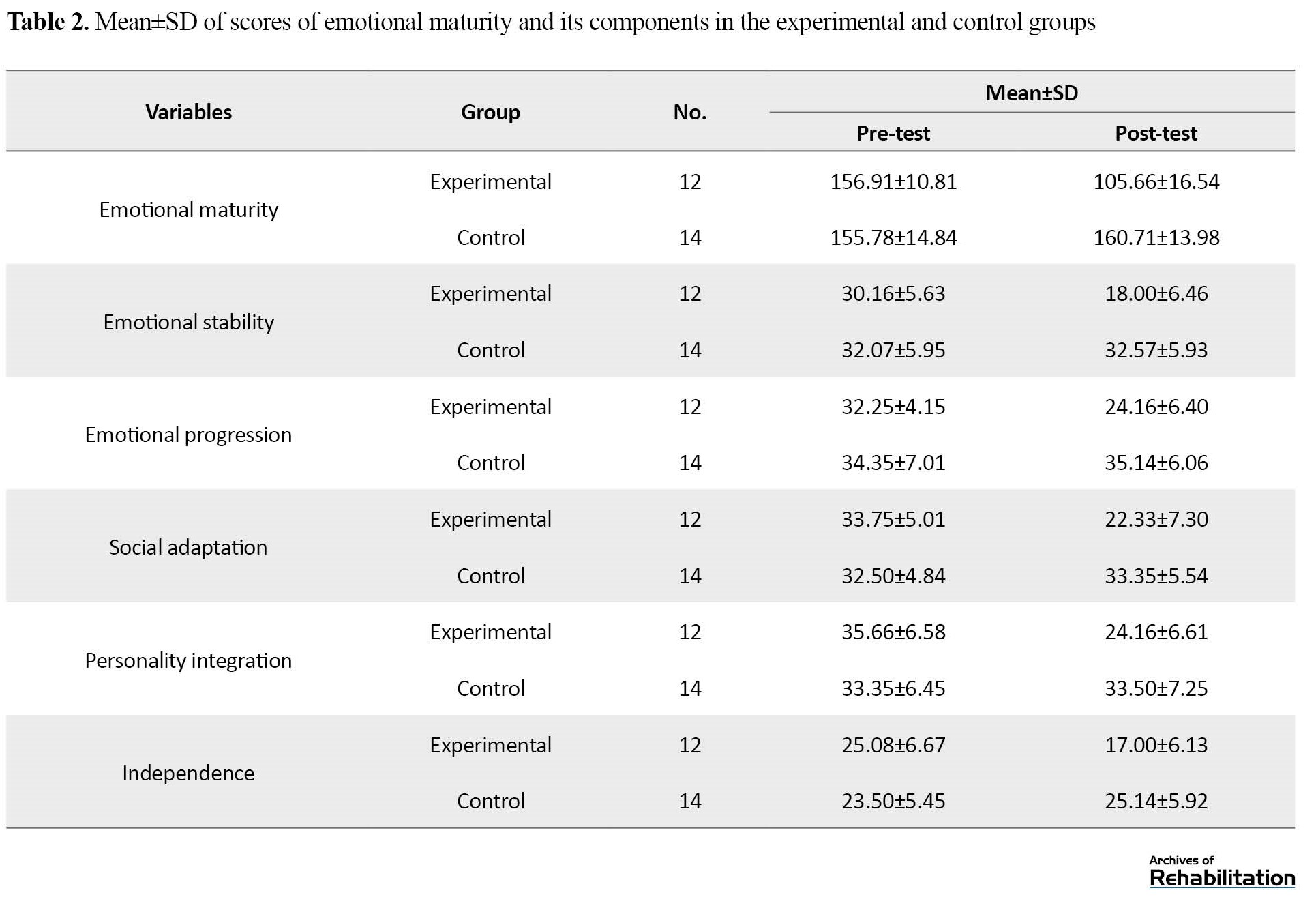

The Mean±SD age of adolescents in the experimental and control groups were 16.17±2.11 and 16.22±1.23 years, respectively. The chi-square test was used to determine the difference between the experimental and control groups regarding age and educational level. Its significance level was 1.00 and 0.705 for age and educational level, respectively. As the significant levels were higher than 0.05, both groups were matched in terms of age and educational level. The Mean±SD of emotional maturity and component scores (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in the pre-test and post-test stages were separately shown for experimental and control groups in Table 2.

As seen in Table 2, the Mean±SD scores of emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) are not different in the experimental and control groups in the pre-test stage (a higher score indicates difficulty in emotional maturity and a lower score suggests normal emotional maturity). On the other hand, the Mean±SD scores of emotional maturity and its components in the experimental group decreased in the post-test stage (indicating the improvement of emotional maturity). In contrast, the Mean±SD scores of emotional maturity and its areas in the control group increased in the post-test stage (indicating no improvement in emotional maturity).

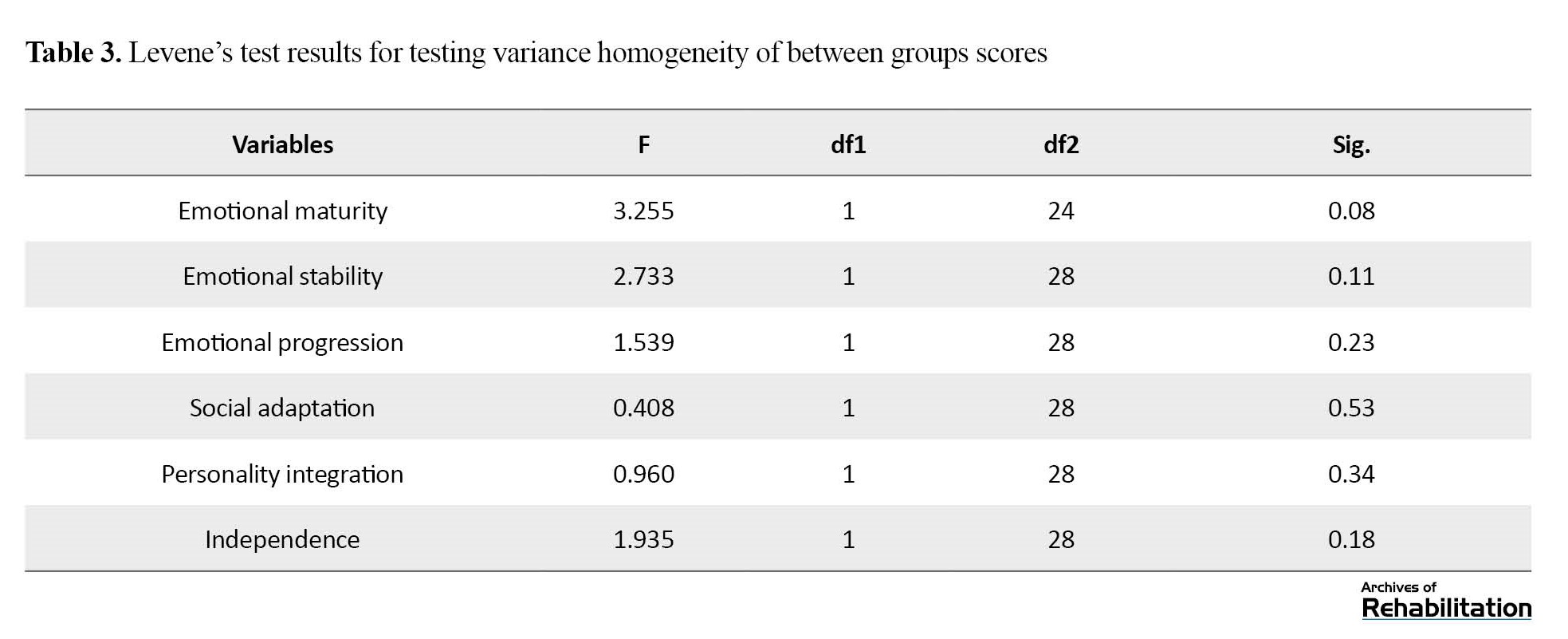

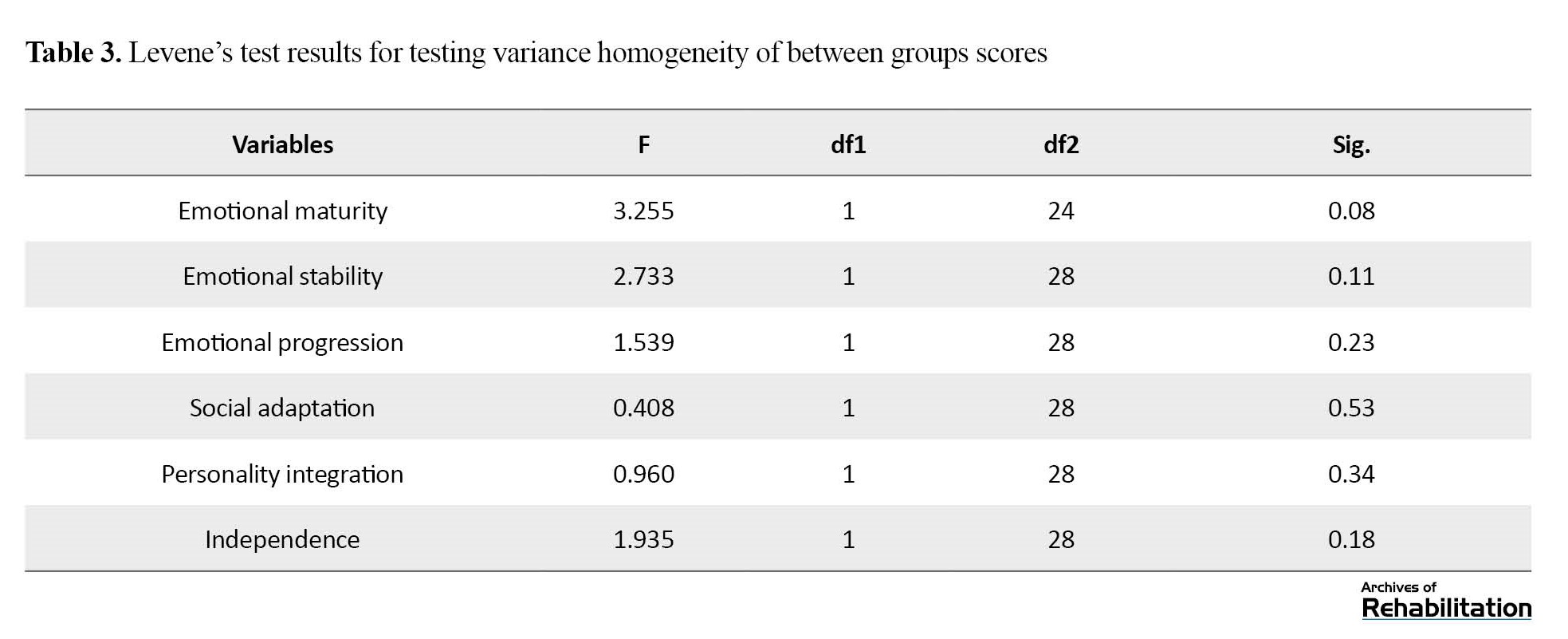

To investigate whether ACT improves emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment, we used a multivariate analysis of covariance. For this purpose, its assumptions were examined. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test showed that none of the values obtained for emotional maturity and its components are significant at the 0.05 level in one group, so the assumption of the normal distribution of scores was established. Therefore, there is no difference between the experimental and control groups regarding the research variables in the pre-test stage, which means that the two groups are homogeneous in the pre-test stage. The Levene test was used to test the assumption of homogeneity of variances (Table 3).

The two groups are homogeneous in the pre-test stage. The default analysis of variance homogeneity using the Levene test showed that the value of F (1.202) was not significant (P>0.05), so the assumption of variance homogeneity was established.

Examining the assumption of homogeneity of the regression slope between the auxiliary variable (emotional maturity in the pre-test) and dependent variable (emotional maturity in the post-test) at factor levels (experimental and control groups) showed that the interaction of pre-tests and post-tests of emotional maturity and its areas (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in the group is not significant (P>0.05). The assumption of homogeneity of the variance-covariance matrix of the emotional maturity areas in the research groups was confirmed according to the value of M Box (15.315), index F=0.785, and P=0.696. it is concluded that the homogeneity assumption of the variance-covariance matrix is established.

Considering all the assumptions, the multivariate analysis of covariance was used to test the research hypothesis of whether acceptance and commitment therapy improves emotional maturity and its areas (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment (Table 4).

Based on the results presented in Table 4, the presence of adolescents with visual impairment in ACT sessions has improved their emotional maturity compared to the control group. Also, based on the eta coefficient, it can be stated that 90% of changes in the emotional maturity of adolescents with visual impairment are due to receiving ACT. Therefore, the first research hypothesis was confirmed. Also, the findings presented in Table 4 indicate that emotional maturity in adolescents with visual impairment has improved after attending ACT sessions. Thus, based on the eta coefficients, 69%, 59%, 55%, 92%, and 68% of the changes in emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence are, respectively, due to receiving the ACT by adolescents with visual impairment. In this way, the second research hypothesis was confirmed.

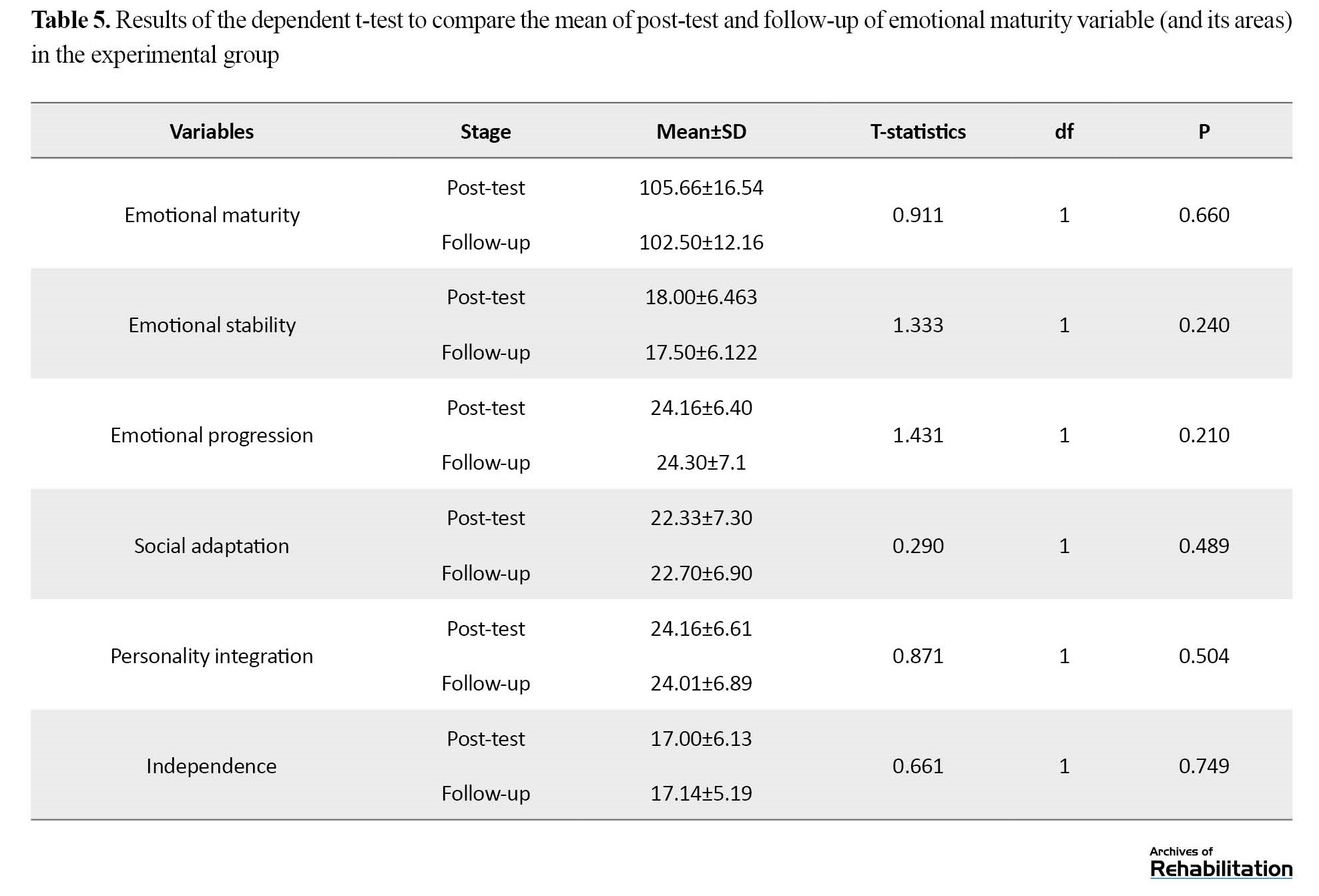

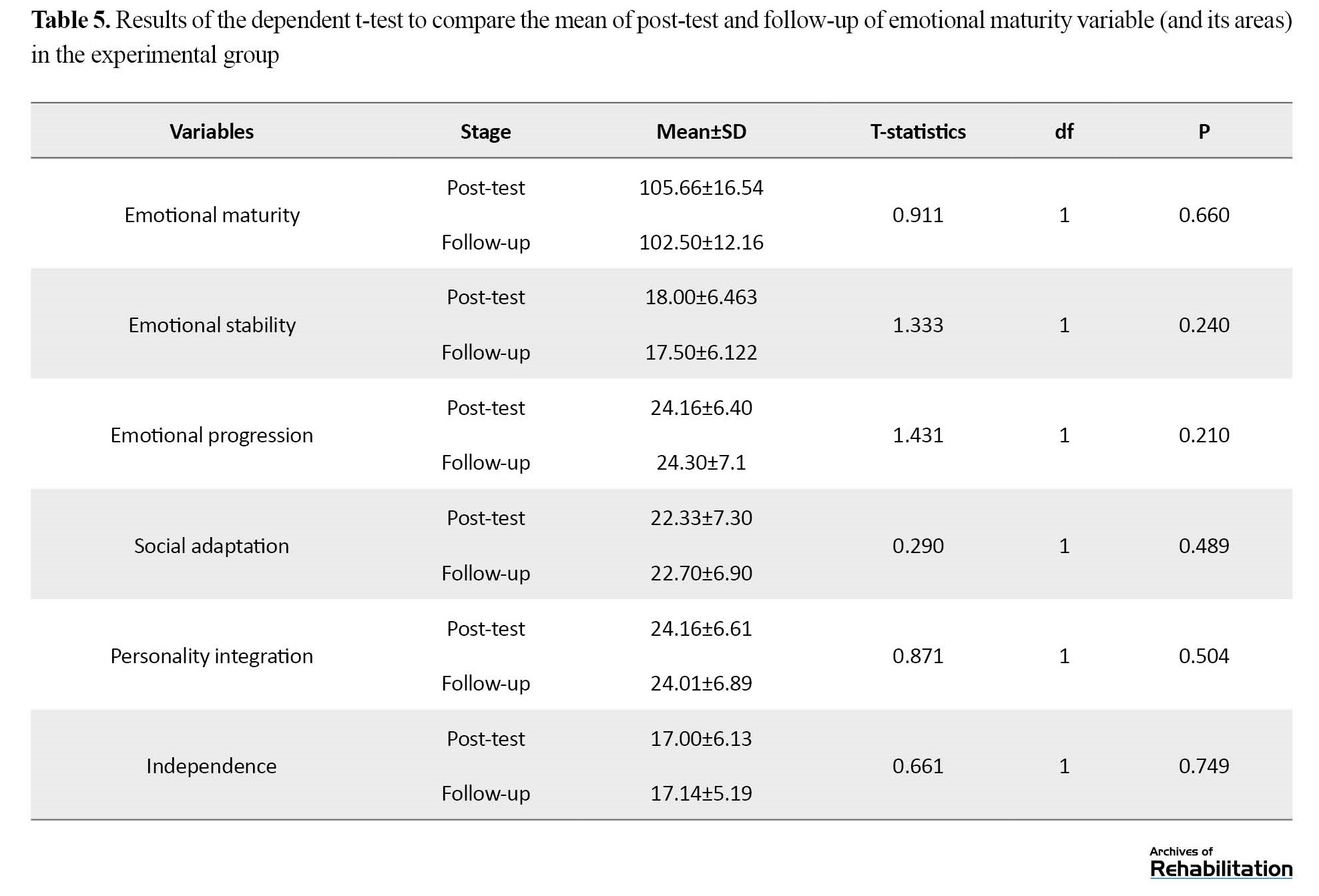

To test the stability of the effect of ACT on emotional maturity and its components in adolescents with visual impairment, the dependent t-test was used (Table 5).

As the results of Table 5 show, there is no significant difference between the post-test and follow-up scores of the emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in the experimental group. Therefore, the effect of ACT on emotional maturity and its components of adolescents with visual impairment remains stable even 8 weeks after the end of the therapeutic program (Table 5).

Discussion

The study’s objective was to determine the effect of ACT on emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment. The first finding of the research showed that ACT improves emotional maturity in female adolescents with visual impairment. The recent finding is consistent with the results of some studies [15, 30]. Explaining the recent findings, it can be noted that female adolescents, compared to male adolescents, experience more challenges regarding emotional maturity [48]. ACT seems to be an attractive mindfulness program and more effective than other meditation-based programs for working with female adolescents. Since adolescents should not receive medication, especially in school settings, the use of psychological therapies is increasing to help them regulate and manage their emotions. Mindfulness in regulating emotions is crucial for adolescents, considering that they are in the transition period from childhood to youth [29]. The two main components of mindfulness are paying attention to the present moment and doing an activity based on adopting a judgment-free attitude [30]. These two components are closely related to two emotion regulation strategies (attention and acceptance). Attention means the ability to choose an aspect to focus on, while acceptance involves experiencing an emotion without trying to prevent it from happening. There are many reasons to accept the belief that mindfulness may be useful for adolescents’ navigation in society. Developmental changes in the brain mean that adolescents are more affected by emotions than adults and experience more intense emotional reactions, although the frontal lobe of the brain (which is responsible for controlling executive functions, judgment, planning, and emotional regulation) has not yet developed in them. Mindfulness and its ability to regulate emotions may help face this imbalance and reduce emotional problems in non-clinical and normal populations [49].

Another research finding indicates that the components of emotional maturity (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) have improved in female adolescents with visual impairment after participating in ACT sessions. The recent finding is consistent with some research results [7, 30, 50, 51]. Explaining this finding that ACT has improved emotional stability, it can be noted that the concept of “values” in ACT is used as a framework to guide intervention strategies and increase life satisfaction and motivation. During ACT sessions, people learn that values are considered desires and wish to achieve in the future. Behavioral principles and ACT can help people behave according to their values. Performing such important and purposeful behaviors even when experiencing intense emotions may be considered a form of emotion regulation [29]. When thoughts and feelings cause people to engage in behaviors far from their values, the principles of ACT help them overcome thoughts, feelings, and emotions. A blind person should accept visual impairment in the present moment and experience pleasant thoughts and emotions. Although living in a school complex helps female adolescents achieve better social integration in the group, it seems that they are deprived of the emotional support of their family. Participating in an intervention program similar to ACT provides the necessary emotional support for them [30].

Another finding indicates that ACT increases social adjustment in female adolescents with visual impairment. This finding is consistent with other research studies [22, 50, 52]. Stability and emotional stability are the main determinants of personality patterns but also affect adolescents’ growth and development and represent normal emotional development at any level. A person’s potential to develop emotional aspects depends on his or her social interaction and relationship with other people. Since adolescents with visual impairment are deprived of the opportunity to interact face-to-face with other people, they usually experience emotional instability. Still, during therapeutic sessions, they learn to increase their capacity to adapt to themselves and their peers, endure deprivation, plan for the long term, and postpone their expectations or change them according to different situations. This issue leads to the improvement of their social adaptation [52].

Another finding indicates that ACT has improved the personality integration of female adolescents with visual impairment. This finding is consistent with the results of previous research [20]. To explain this finding, it can be noted that some adolescents with visual impairments who fail in the transition from childhood to youth could not acquire a unified identity properly, so they probably would not experience the personality integration to confront various problems. Suppression of emotions and feelings, withdrawal, defensive reactions, and blaming themselves or others are the most important ones among those problems. Visual impairment causes an imbalance in these people’s cognitive, emotional, linguistic, social, and movement [17]. So, the delay in developing the skills mentioned above postpones the social development of adolescents and the possibility of healthy interaction with other people [21]. As a result, adolescents have problems satisfying their natural needs [52]. ACT is an attractive mindfulness program for adolescents because they are aware of the role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, which helps them go through the transition period well and achieve an integrated identity of themselves [30]. Emotion regulation helps adolescents identify, understand, accept, and adjust flexible responses to emotions. A high ability to regulate emotions allows people to behave according to personal goals even when faced with difficult emotions, in addition to having to manage their impulsive behavior. Therefore, adhering to and acting on values is essential for adolescents to integrate identity and achieve a coherent personality [34].

The last finding indicates that the ACT improves independence in female adolescents with visual impairment. This finding is consistent with another study [10]. Since one of the components of emotional maturity is to achieve independence, it is possible to say that when people have a high commitment to carry out their daily activities, they can build relationships based on their inner experiences. They try to increase their flexibility to behave according to their life values, accept their current situations, and not need to be monitored by others. Therefore, they try to do things independently through self-regulation. This process results from mindfulness and emotion regulation and is considered one of the signs of emotional maturity [13].

Conclusion

According to the present study, ACT has improved emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment. One of the main goals of ACT is to help adolescents understand that, as they build their values without showing a negative attitude towards their disability or handicap, they find the point that they recognize and accept their thoughts, feelings, and emotions instead of inhibiting them. Since emotional maturity represents normal emotional development, the provision and implementation of complementary and therapeutic programs by psychologists who help therapeutic services to adolescents with visual impairment postpone the satisfaction of their needs, tolerate failure, plan to achieve long-term goals and adjust their expectations in relation to different situations. In this way, the necessary platform for preventing social maladaptation in adolescents will be provided.

Available sampling, not paying attention to demographic variables (socioeconomic status, birth order, number of siblings), selecting only female samples, and using a self-report questionnaire are the most important limitations of the present study. Therefore, it is suggested that other methods (i.e. interviews with adolescents and their peers) be employed to measure emotional maturity. Using ACT for other adolescents with special needs can lead to promising results. Also, controlling some demographic variables and considering the gender variable and random sampling in such studies can enrich and generalize research findings. In addition, holding empowerment workshops for parents and teachers who deal with adolescents with visual impairment can be effective in preventing the emotional problems of this group of people.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1398.170). To comply with ethical considerations, the research objectives were explained to the authorities of the educational complex and adolescents. After obtaining written consent, the participants were assured that the information acquired from the questionnaires would remain confidential. Their participation in the research will not involve any losses, and adolescents who do not want to continue the study could withdraw. While paying attention to adolescents’ mental states and fatigue, efforts were made to respect their dignity and human rights during the research. After the intervention, the people of the control group were introduced to the content of the group therapeutic program based on ACT in three intensive sessions.

Funding

The present article was extracted from the master’s thesis of Fatemeh Mirmohammadi approved by Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, sources and writing: All authors; Supervision and visualization: Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi; Project management: Fatemeh Mirmohammadi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors hereby express their gratitude to the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences and Exceptional Education Organization in Tehran City, and the authorities of the educational complex for blind people.

Visual impairment is one of the most critical and common disabilities; 285 million people worldwide have a visual impairment, of which 39 million are blind, and 246 million are visually impaired [1]. All over the world, visual impairment ranks 14th among other physical injuries [2]. In Iran, the number of blind and partially sighted people is reported to be approximately 180000 [3]. Visually impaired people are deprived of the opportunities of face-to-face observation and contact and have a different perception of the world. This issue can lead to emotional and social problems [4].

Psychological, physical, social, and emotional maturity is one of adolescence’s main challenges, accompanied by dramatic changes in adolescence. Nevertheless, the recent challenges become worse when the adolescent has a disability in addition to puberty changes [5]. During emotional maturity, a person continuously tries to achieve emotional and psychological health [6]. Emotional maturity consists of 7 components: Intimacy, empathy, self-expression, psychological stability, independence, psychological balance, and the ability to consider emotional issues [7].

As adolescents grow, they are supported by their parents, can achieve emotional stability [8], and learn how to expand interpersonal and intra-personal relationships [9]. Poor emotional maturity leads to ineffective coping methods [10], and higher emotional maturity leads to problem-oriented and more helpful coping strategies [11]. The most prominent sign of emotional maturity is the ability to tolerate stress and indifference [12] to some stimuli that negatively impact people and cause them to become bored or emotional [13]. Emotional stability (an essential component of emotional maturity) is one of the main determinants of personality patterns that affect adolescent development. People with emotional stability can postpone the satisfaction of their needs, tolerate failure, believe in long-term planning, and change their expectations according to different situations [14].

Due to poor eyesight, people with visual impairments probably struggle to form secure bonds with others and adapt to challenging situations [15]. During adolescence, they have deficient emotional maturity, less ability to adjust emotionally and socially to the environment [16], and more academic problems [17]. In addition, they experience more behavioral problems, psychological disorders [18], and emotional problems compared to their normal peers [19]. However, some findings indicate no difference between the prevalence of psychological issues and depression in adolescents with visual impairment compared to normal adolescents [20]. Those adolescents with vision impairment who cannot transition from childhood to youth properly do not achieve an integrated identity of themselves. Therefore, they experience various problems, including suppression of emotions and feelings, isolation, defensive reactions, and blaming themselves or others. Even severe symptoms of depression and anxiety have been reported in visually impaired girls more than boys [19]. Visual impairment in these people causes cognitive, emotional, social, and movement problems [17]. The delay in the skills mentioned above leads to a gap in social development and deprives adolescents of the possibility of healthy interaction with other people. As a result, adolescents have problems satisfying their natural needs [21].

Despite emotional problems in visually impaired adolescents [22], the use of therapeutic interventions to provide emotional management and mental health in visually impaired teenagers can prevent the occurrence of many emotional and psychological problems and disturbances in the forthcoming years [23]. One of the preventive approaches to the occurrence of emotional issues and managing emotions in people is acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT). Demehri et al. presented ACT in the early 1980s. It is one of the third-wave behavioral therapies [24]. The ACT approach is based on the philosophy of realistic conceptualism and emphasizes context’s role in understanding nature and events. The main goal of therapy is to help people effectively manage the pains, sufferings, and tensions they have experienced, communicate with the present moment, increase their flexibility, and change their behavior to achieve valuable goals [25]. One of the main components of ACT is identifying and recognizing the boundaries that prevent people from living a desirable life [26]. The six essential processes in ACT are acceptance, being in the present moment, specifying values, cognitive diffusion, commitment to action, and considering self as content for change. The purpose of all the mentioned processes is to confront the person with the experiences of the present time so that he can eliminate the connection between negative thoughts and previous experiences, accept the actual relationships between thoughts and experiences, and separate his earlier experiences from the fake world, and achieve goals that have higher value and stick to his values in life [27].

ACT uses “values” to guide intervention strategies, improve life satisfaction, and increase motivation [28]. Behavioral principles, along with ACT, help people to act based on their values. Performing these important and purposeful behaviors may be considered a form of emotion regulation even when experiencing intense emotions [29]. When thoughts and feelings keep a person from maintaining behaviors in accordance with values, the principles of acceptance and commitment therapy are considered. Although ACT has been designed for adults, it applies to the clinical population of adolescents, and its principles are the same. Still, its exercises, examples, and metaphors are adapted to the conditions of adolescents [30].

Many findings of previous studies indicate the effect of ACT on the mental health of adolescents [31], reducing psychological distress [32], reducing physical aggression [33], improving emotional regulation [34], reducing depression and increasing adaptation [35], regulating mood states [36], reducing obsessive-compulsive disorder [37], improving resilience and optimism [38], and improving self-esteem [39]. However, according to the researcher’s investigation, the previous studies have not explored the effect of ACT on the emotional maturity of visually impaired adolescents.

In general, the components of ACT, including values, may be beneficial for adolescents because they are in a transitional period to achieve an integrated identity [30]. However, ACT has not yet been tested as a preventive program in a non-clinical adolescent population. The results of the clinical samples show that ACT is effective as an emotion regulation strategy. Therefore, the need to deal with it as a preventive program, especially during adolescence, is more felt. Consequently, it is essential to administer research that shows how acceptance and commitment therapy can be used in real-life situations and non-clinical samples. So, based on the research findings, the ACT approach can be applied to the normal population [40]. For this reason, the present research investigated whether group ACT affects emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adjustment, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment.

Materials and Methods

The current quasi-experimental employed a pre-test and post-test design with a control group, which was conducted with an 8-week follow-up. An educational complex special for the 14 to 18 years old visually-impaired females was selected in Tehran City, Iran. The study was conducted in the 2020-2021 academic year. The sample size was determined considering the type 1 error of 0.05, test power of 0.84, σ=2.13, 2µ=10.3, 1µ=0.12, and a possible dropout of at least 28 people (14 in each group). The samples were randomly assigned to the experimental and control groups.

Data collection tools

Emotional maturity scale

The current study collected information using the emotional maturity scale (EMS). Bal prepared this self-report scale. It has 48 items and covers five areas: Emotional stability (10 items), emotional progression (10 items), social adjustment (10 items), personality integration (10 items), and independence (8 items) [41]. This scale is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 to 5 for each option: Very much, a lot, uncertain, probably, and never, respectively. A person’s high score (>180) indicates a problem in emotional maturity and its related components. The reliability values of the whole scale were 0.75 and 0.64, using the test re-test method and the internal consistency, respectively. The reliability values for emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence were 0.75, 0.63, 0.58, 0.86, and 0.42, respectively [42].

The present study used the test re-test method with 10 visually impaired teenagers at a 4-week interval to check the EMS’s reliability. The Pearson correlation coefficient calculated for the reliability of the whole scale was 0.90. Also, the coefficients were 0.99, 0.98, 0.97, 0.90, and 0.85 for emotional stability, emotional progression, social adjustment, personality integration, and independence, respectively. In addition, the internal correlation coefficient for the whole emotional maturity scale was 0.85, indicating an excellent coefficient for the scale.

Study procedure

After obtaining the code of ethics and the letter of representation from the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, the permission received from the Organization of Exceptional Education in Tehran City for referring to one of the educational complexes special for visually impaired females in the academic year 2020-2021. At first, the research objectives were described and explained to the complex authorities, and the volunteers signed a written consent form to cooperate in the study. Then, 82 teenagers were individually evaluated using the EMS. The research assistant read the emotional maturity scale for each adolescent individually and recorded their responses to each item. After scoring the scale by the researcher, 33 people who got a score of 180 or higher were included in the study according to the inclusion criteria. These criteria were having visual impairment from low vision to total blindness, having normal intelligence, not suffering from hearing impairment, behavioral problems, and multiple disabilities based on their school file. The exclusion criteria were the absence of more than two sessions from ACT or participating simultaneously or for the last six months in group ACT sessions. Twenty-eight adolescents were randomly selected and matched based on age and educational level. Then, they were assigned to experimental and control groups (14 people in each group). Considering the condition of visual impairment in participants and to increase the effectiveness of ACT in small groups [43], the experimental group was divided into two subgroups of 7 people, and each subgroup attended 10 ACT group sessions for two months (once a week; each session lasted 60 minutes) after the curriculum time of the complex. At the same time, the control group only participated in make-up empowering sessions in the complex. Therapeutic sessions were held in a separate room in the complex (7 people in the room separately and on different days). The researcher’s assistant implemented the EMS, but the researcher (trained in the ACT workshop and certified) scored the EMS and administered the therapeutic sessions. In addition, none of the participants or the research assistant were aware that the questionnaire belonged to the people of the experimental or control groups.

The outline of the ACT protocol was prepared based on the content of the books “acceptance and commitment therapy” [44] and “case conceptualization in acceptance & commitment therapy” [45]. Using mindfulness, the Gestalt technique, and one of the previous studies in this field [46], we tried to adjust each method according to the conditions of visually impaired teenagers and follow each therapeutic session’s goals. Also, the content of the program was flexible for the adolescents. The design of the therapeutic protocol, examples, and metaphors used in the sessions were adapted according to the characteristics of visually impaired teenagers and the opinion of the experts for educating blind people. The intervention rating profile questionnaire (developed by Martens et al. in 1985) was used to measure the social validity of the protocol. This questionnaire has 15 questions rated from 1 to 6 for “completely agree” to “completely disagree”. The range of total scores is between 15 and 90. A score higher than 52 indicates acceptance of the intervention protocol [47]. The stability of the questionnaire was found between 0.84 and 0.98 through internal consistency, and the social validity score in the present study was 71, which was acceptable. All participants were re-evaluated using the EMS after the last acceptance and commitment group therapy session and then 8 weeks later. During the therapeutic sessions, the experimental group lost two people due to their unwillingness to continue working with the researcher. To comply with ethical considerations, the content of the ACT was briefly held for the control group in 3 sessions after the end of the research process and follow-up period. Also, the teenagers were free to refuse to continue working with the researcher whenever they wanted; the researcher was also committed to maintaining the privacy and personal and confidential information of the teenagers. Participation in the research had no additional costs or possible losses for the participants. The data obtained from the pre-test, post-test, and follow-up were analyzed using the Shapiro-Wilk test (to check normality), Levene’s test (to determine the homogeneity of variances), M. Box test (to determine the homogeneity of the line slope), multivariate analysis of covariance, and the dependent t-test.

The content of the ACT protocol by sessions is presented in Table 1.

Results

The Mean±SD age of adolescents in the experimental and control groups were 16.17±2.11 and 16.22±1.23 years, respectively. The chi-square test was used to determine the difference between the experimental and control groups regarding age and educational level. Its significance level was 1.00 and 0.705 for age and educational level, respectively. As the significant levels were higher than 0.05, both groups were matched in terms of age and educational level. The Mean±SD of emotional maturity and component scores (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in the pre-test and post-test stages were separately shown for experimental and control groups in Table 2.

As seen in Table 2, the Mean±SD scores of emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) are not different in the experimental and control groups in the pre-test stage (a higher score indicates difficulty in emotional maturity and a lower score suggests normal emotional maturity). On the other hand, the Mean±SD scores of emotional maturity and its components in the experimental group decreased in the post-test stage (indicating the improvement of emotional maturity). In contrast, the Mean±SD scores of emotional maturity and its areas in the control group increased in the post-test stage (indicating no improvement in emotional maturity).

To investigate whether ACT improves emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment, we used a multivariate analysis of covariance. For this purpose, its assumptions were examined. The results of the Shapiro-Wilk test showed that none of the values obtained for emotional maturity and its components are significant at the 0.05 level in one group, so the assumption of the normal distribution of scores was established. Therefore, there is no difference between the experimental and control groups regarding the research variables in the pre-test stage, which means that the two groups are homogeneous in the pre-test stage. The Levene test was used to test the assumption of homogeneity of variances (Table 3).

The two groups are homogeneous in the pre-test stage. The default analysis of variance homogeneity using the Levene test showed that the value of F (1.202) was not significant (P>0.05), so the assumption of variance homogeneity was established.

Examining the assumption of homogeneity of the regression slope between the auxiliary variable (emotional maturity in the pre-test) and dependent variable (emotional maturity in the post-test) at factor levels (experimental and control groups) showed that the interaction of pre-tests and post-tests of emotional maturity and its areas (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in the group is not significant (P>0.05). The assumption of homogeneity of the variance-covariance matrix of the emotional maturity areas in the research groups was confirmed according to the value of M Box (15.315), index F=0.785, and P=0.696. it is concluded that the homogeneity assumption of the variance-covariance matrix is established.

Considering all the assumptions, the multivariate analysis of covariance was used to test the research hypothesis of whether acceptance and commitment therapy improves emotional maturity and its areas (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment (Table 4).

Based on the results presented in Table 4, the presence of adolescents with visual impairment in ACT sessions has improved their emotional maturity compared to the control group. Also, based on the eta coefficient, it can be stated that 90% of changes in the emotional maturity of adolescents with visual impairment are due to receiving ACT. Therefore, the first research hypothesis was confirmed. Also, the findings presented in Table 4 indicate that emotional maturity in adolescents with visual impairment has improved after attending ACT sessions. Thus, based on the eta coefficients, 69%, 59%, 55%, 92%, and 68% of the changes in emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence are, respectively, due to receiving the ACT by adolescents with visual impairment. In this way, the second research hypothesis was confirmed.

To test the stability of the effect of ACT on emotional maturity and its components in adolescents with visual impairment, the dependent t-test was used (Table 5).

As the results of Table 5 show, there is no significant difference between the post-test and follow-up scores of the emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in the experimental group. Therefore, the effect of ACT on emotional maturity and its components of adolescents with visual impairment remains stable even 8 weeks after the end of the therapeutic program (Table 5).

Discussion

The study’s objective was to determine the effect of ACT on emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment. The first finding of the research showed that ACT improves emotional maturity in female adolescents with visual impairment. The recent finding is consistent with the results of some studies [15, 30]. Explaining the recent findings, it can be noted that female adolescents, compared to male adolescents, experience more challenges regarding emotional maturity [48]. ACT seems to be an attractive mindfulness program and more effective than other meditation-based programs for working with female adolescents. Since adolescents should not receive medication, especially in school settings, the use of psychological therapies is increasing to help them regulate and manage their emotions. Mindfulness in regulating emotions is crucial for adolescents, considering that they are in the transition period from childhood to youth [29]. The two main components of mindfulness are paying attention to the present moment and doing an activity based on adopting a judgment-free attitude [30]. These two components are closely related to two emotion regulation strategies (attention and acceptance). Attention means the ability to choose an aspect to focus on, while acceptance involves experiencing an emotion without trying to prevent it from happening. There are many reasons to accept the belief that mindfulness may be useful for adolescents’ navigation in society. Developmental changes in the brain mean that adolescents are more affected by emotions than adults and experience more intense emotional reactions, although the frontal lobe of the brain (which is responsible for controlling executive functions, judgment, planning, and emotional regulation) has not yet developed in them. Mindfulness and its ability to regulate emotions may help face this imbalance and reduce emotional problems in non-clinical and normal populations [49].

Another research finding indicates that the components of emotional maturity (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) have improved in female adolescents with visual impairment after participating in ACT sessions. The recent finding is consistent with some research results [7, 30, 50, 51]. Explaining this finding that ACT has improved emotional stability, it can be noted that the concept of “values” in ACT is used as a framework to guide intervention strategies and increase life satisfaction and motivation. During ACT sessions, people learn that values are considered desires and wish to achieve in the future. Behavioral principles and ACT can help people behave according to their values. Performing such important and purposeful behaviors even when experiencing intense emotions may be considered a form of emotion regulation [29]. When thoughts and feelings cause people to engage in behaviors far from their values, the principles of ACT help them overcome thoughts, feelings, and emotions. A blind person should accept visual impairment in the present moment and experience pleasant thoughts and emotions. Although living in a school complex helps female adolescents achieve better social integration in the group, it seems that they are deprived of the emotional support of their family. Participating in an intervention program similar to ACT provides the necessary emotional support for them [30].

Another finding indicates that ACT increases social adjustment in female adolescents with visual impairment. This finding is consistent with other research studies [22, 50, 52]. Stability and emotional stability are the main determinants of personality patterns but also affect adolescents’ growth and development and represent normal emotional development at any level. A person’s potential to develop emotional aspects depends on his or her social interaction and relationship with other people. Since adolescents with visual impairment are deprived of the opportunity to interact face-to-face with other people, they usually experience emotional instability. Still, during therapeutic sessions, they learn to increase their capacity to adapt to themselves and their peers, endure deprivation, plan for the long term, and postpone their expectations or change them according to different situations. This issue leads to the improvement of their social adaptation [52].

Another finding indicates that ACT has improved the personality integration of female adolescents with visual impairment. This finding is consistent with the results of previous research [20]. To explain this finding, it can be noted that some adolescents with visual impairments who fail in the transition from childhood to youth could not acquire a unified identity properly, so they probably would not experience the personality integration to confront various problems. Suppression of emotions and feelings, withdrawal, defensive reactions, and blaming themselves or others are the most important ones among those problems. Visual impairment causes an imbalance in these people’s cognitive, emotional, linguistic, social, and movement [17]. So, the delay in developing the skills mentioned above postpones the social development of adolescents and the possibility of healthy interaction with other people [21]. As a result, adolescents have problems satisfying their natural needs [52]. ACT is an attractive mindfulness program for adolescents because they are aware of the role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, which helps them go through the transition period well and achieve an integrated identity of themselves [30]. Emotion regulation helps adolescents identify, understand, accept, and adjust flexible responses to emotions. A high ability to regulate emotions allows people to behave according to personal goals even when faced with difficult emotions, in addition to having to manage their impulsive behavior. Therefore, adhering to and acting on values is essential for adolescents to integrate identity and achieve a coherent personality [34].

The last finding indicates that the ACT improves independence in female adolescents with visual impairment. This finding is consistent with another study [10]. Since one of the components of emotional maturity is to achieve independence, it is possible to say that when people have a high commitment to carry out their daily activities, they can build relationships based on their inner experiences. They try to increase their flexibility to behave according to their life values, accept their current situations, and not need to be monitored by others. Therefore, they try to do things independently through self-regulation. This process results from mindfulness and emotion regulation and is considered one of the signs of emotional maturity [13].

Conclusion

According to the present study, ACT has improved emotional maturity and its components (emotional stability, emotional progression, social adaptation, personality integration, and independence) in female adolescents with visual impairment. One of the main goals of ACT is to help adolescents understand that, as they build their values without showing a negative attitude towards their disability or handicap, they find the point that they recognize and accept their thoughts, feelings, and emotions instead of inhibiting them. Since emotional maturity represents normal emotional development, the provision and implementation of complementary and therapeutic programs by psychologists who help therapeutic services to adolescents with visual impairment postpone the satisfaction of their needs, tolerate failure, plan to achieve long-term goals and adjust their expectations in relation to different situations. In this way, the necessary platform for preventing social maladaptation in adolescents will be provided.

Available sampling, not paying attention to demographic variables (socioeconomic status, birth order, number of siblings), selecting only female samples, and using a self-report questionnaire are the most important limitations of the present study. Therefore, it is suggested that other methods (i.e. interviews with adolescents and their peers) be employed to measure emotional maturity. Using ACT for other adolescents with special needs can lead to promising results. Also, controlling some demographic variables and considering the gender variable and random sampling in such studies can enrich and generalize research findings. In addition, holding empowerment workshops for parents and teachers who deal with adolescents with visual impairment can be effective in preventing the emotional problems of this group of people.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1398.170). To comply with ethical considerations, the research objectives were explained to the authorities of the educational complex and adolescents. After obtaining written consent, the participants were assured that the information acquired from the questionnaires would remain confidential. Their participation in the research will not involve any losses, and adolescents who do not want to continue the study could withdraw. While paying attention to adolescents’ mental states and fatigue, efforts were made to respect their dignity and human rights during the research. After the intervention, the people of the control group were introduced to the content of the group therapeutic program based on ACT in three intensive sessions.

Funding

The present article was extracted from the master’s thesis of Fatemeh Mirmohammadi approved by Department of Psychology and Education of Exceptional Children, Faculty of Behavioral Sciences and Mental Health, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, analysis, sources and writing: All authors; Supervision and visualization: Masoume Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi; Project management: Fatemeh Mirmohammadi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors hereby express their gratitude to the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences and Exceptional Education Organization in Tehran City, and the authorities of the educational complex for blind people.

References

- Pascolini D, Mariotti SP. Global estimates of visual impairment: 2010. The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 2012; 96(5):614-8. [DOI:10.1136/bjophthalmol-2011-300539] [PMID]

- Ashrafi E, Mohammadi SF, Fotouhi A, Lashay A, Asadi-lari M, Mahdavi A, et al. National and sub-national burden of visual impairment in Iran 1990-2013; study protocol. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 2014; 17(12):810-5. [PMID]

- Hashemi H, Rezvan F, Yekta A, Ostadimoghaddam H, Soroush S, Dadbin N, et al. The prevalence and causes of visaual impairment and blindness in a rural population in the north of Iran. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2015; 44(6):855-64. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ruiz FJ, Flórez CL, García-Martín MB, Monroy-Cifuentes A, Barreto-Montero K, García-Beltrán DM, et al. A multiple-baseline evaluation of a brief acceptance and commitment therapy protocol focused on repetitive negative thinking for moderate emotional disorders. Journal of contextual behavioral science. 2018; 9:1-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2018.04.004]

- Aghaee-Chaghooshi S, Khodabakhshi-Koolaee A, Falsafinejad M. Puberty challenges of female adolescents with visual impairment. British Journal of Visual Impairment. 2021; 41(1):96-107. [DOI:10.1177/02646196211019069]

- Joy M, Mathew A. Emotional maturity and general well-being of adolescents. IOSR Journal of Pharmacy. 2018; 8(5):1-6. [Link]

- Sunny AM, Jacob JG, Jimmy N, Shaji DT, Dominic C. Emotional maturity variation among college students with perceived loneliness. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications. 2018; 8(5):233-51. [DOI:10.29322/IJSRP.8.5.2018.p7736]

- Rawat C, Gulati R. Influence of Home environment and peers influence on Emotional maturity of Adolescents. Journal of Social Sciences. 2019; 6(1):15-8. [Link]

- Jobson MC. Emotional maturity among adolescents and its importance. Indian Journal of Mental Health. 2020; 7(1):35-41. [DOI:10.30877/IJMH.7.1.2020.35-41]

- Bélanger J, Edwards PK, Wright M. Commitment at work and independence from management:a study of advanced teamwork. Work and Occupations. 2003; 30(2):234-52. [DOI:10.1177/0730888403251708]

- Rawat C, Singh R. A study of emotional maturity of adolescents with respect to their educational settings. Journal of Social Sciences. 2016; 49(3-2):345-51. [DOI:10.1080/09718923.2016.11893630]

- Dousti M, PourmohamadrezaTajrishi M, GhobariBonab B. [The effectiveness of resilience training on psychological well-being of female street children with externalizing disorders (Persian)]. Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2014; 11(41):43-54. [Link]

- Cloninger KM, Cloninger CR. The psychobiology of the path to a joyful life: Implications for future research and practice. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2020; 15(1):74-83. [DOI:10.1080/17439760.2019.1685579]

- Singh R, Pant K, Valentina L. Impact analysis: Family structure on social and emotional maturity of adolescents. The Anthropologist. 2014; 17(2):359-65. [DOI:10.1080/09720073.2014.11891445]

- Demir T, Bolat N, Yavuz M, Karaçetin G, Doğangün B, Kayaalp L. Attachment characteristics and behavioral problems in children and adolescents with congenital blindness. Noro Psikiyatri Arsivi. 2014; 51(2):116-21. [DOI:10.4274/npa.y6702] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Wong HB, Machin D, Tan SB, Wong TY, Saw SM. Visual impairment and its impact on health-related quality of life in adolescents. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 2009; 147(3):505-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.ajo.2008.09.025] [PMID]

- Chennaz L, Valente D, Baltenneck N, Baudouin JY, Gentaz E. Emotion regulation in blind and visually impaired children aged 3 to 12 years assessed by a parental questionnaire. Acta Psychologica. 2022; 225:103553. [DOI:10.1016/j.ACTpsy.2022.103553] [PMID]

- Ghorbaninejad S, Sajedi F, Pourmohamadreza Tajrishi M, Hosseinzadeh S. The relations between behavioral problems and demographic variables in students with visual impairment. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2020; 18(3):249-56. [DOI:10.32598/irj.18.3.260.1]

- Augestad LB. Mental health among children and young adults with visual impairments: A systematic review. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness. 2017; 111(5):411-25. [DOI:10.1177/0145482X1711100503]

- Garaigordobil M, Bernarás E. Self-concept, self-esteem, personality traits and psychopathological symptoms in adolescents with and without visual impairment. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 2009; 12(1):149-60. [DOI:10.1017/S1138741600001566] [PMID]

- Hankó C, Pohárnok M, Lénárd K, Bíró B. Motherhood experiences of visually impaired and normally sighted women. Human Arenas. 2022; 7:127-55. [DOI:10.1007/s42087-022-00276-9]

- Duijndam S, Karreman A, Denollet J, Kupper N. Emotion regulation in social interaction: Physiological and emotional responses associated with social inhibition. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2020; 158:62-72. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2020.09.013] [PMID]

- Schofield DJ, Shrestha RN, Percival R, Passey ME, Callander EJ, Kelly SJ. The personal and national costs of mental health conditions: Impacts on income, taxes, government support payments due to lost labour force participation. BMC Psychiatry. 2011; 11:72. [DOI:10.1186/1471-244X-11-72] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Demehri F, Saeedmanesh M, Jala N. [The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) on rumination and well-being in adolescents with general anxiety disorder (Persian)]. Middle Eastern Journal of Disability Studies. 2018; 8:25. [Link]

- Nasiri F, Keshavarz Z, Davazdahemami M, Karimkhani Zandi S, Nasiri M. [The effectiveness of religious-spiritual psychotherapy on the quality of life of women with breast cancer (Persian)]. Journal of Babol University of Medical Sciences. 2019; 21(1):67-73. [DOI:10.22088/jbums.21.1.67]

- Lee EB, Pierce BG, Twohig MP, Levin ME. Acceptance and commitment therapy. In: Wenzel A, editor. Handbook of cognitive behavioral therapy: Overview and approaches. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2021. [DOI:10.1037/0000218-019]

- Geda YE, Krell-Roesch J, Fisseha Y, Tefera A, Beyero T, Rosenbaum D, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy in a low-income country in sub-saharan Africa: A call for further research. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021; 9:732800. [DOI:10.3389/fpubh.2021.732800] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Amiri Argmand SA, Mirzaeian B, Baghbanian SM. [Comparison of the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavioral stress management and their combination on distress tolerance and headache reduction in patients with tension headache (Persian)]. Journal of Babol University of Medical Sciences. 2022; 24(1):169-78. [DOI:10.22088/jbums.24.1.169]

- Roemer L, Williston SK, Rollins LG. Mindfulness and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2015; 3:52-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.02.006]

- Livheim F, Hayes L, Ghaderi A, Magnusdottir T, Högfeldt A, Rowse J, et al. The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for adolescent mental health: Swedish and Australian pilot outcomes. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2015; 24(4):1016-30. [DOI:10.1007/s10826-014-9912-9]

- Brown M, Glendenning A, Hoon AE, John A. Effectiveness of web-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy in relation to mental health and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2016; 18(8):e221. [DOI:10.2196/jmir.6200] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Takahashi F, Ishizu K, Matsubara K, Ohtsuki T, Shimoda Y. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a school-based group intervention for adolescents: An open-label trial. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2020; 16:71-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.03.001]

- Bennett CM, Dillman Taylor D. ACTing as yourself: Implementing acceptance and commitment therapy for transgender adolescents through a developmental lens. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling. 2019; 5(2):146-60. [DOI:10.1080/23727810.2019.1586414]

- Guerrini Usubini A, Cattivelli R, Bertuzzi V, Varallo G, Rossi AA, Volpi C, et al. The ACTyourCHANGE in teens study protocol: An acceptance and commitment therapy-based intervention for adolescents with obesity: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021; 18(12):6225. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph18126225] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bass C, van Nevel J, Swart J. A comparison between dialectical behavior therapy, mode deACTivation therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy in the treatment of adolescents. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy. 2014; 9(2):4. [DOI:10.1037/h0100991]

- Van der Gucht K, Griffith JW, Hellemans R, Bockstaele M, Pascal-Claes F, Raes F. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for adolescents: Outcomes of a large-sample, school-based, cluster-randomized controlled trial. Mindfulness. 2017; 8(2):408-16. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-016-0612-y]

- Laurito LD, Loureiro CP, Dias RV, Faro L, Torres B, Moreira-de-Oliveira ME, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy for obsessive compulsive disorder in a Brazilian context: Treatment of three cases. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science. 2022; 24:134-40. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcbs.2022.04.002]

- Shiri S, Farshbaf-Khalili A, Esmaeilpour K, Sattarzadeh N. The effect of counseling based on acceptance and commitment therapy on anxiety, depression, and quality of life among female adolescent students. Journal of Education and Health Promotion. 2022; 11:66. [DOI:10.4103/jehp.jehp_1486_20] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mirmohammadi F, Pourmohamadreza-Tajrishi M, Dolatshahi B, Bakhshi E. [The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment group therapy on the self-esteem of girls with visual impairment (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2021; 22(4):462-81. [DOI:10.32598/RJ.22.4.3261.1]

- Burckhardt R, Manicavasagar V, Batterham PJ, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Shand F. Acceptance and commitment therapy universal prevention program for adolescents: A feasibility study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health. 2017; 11:27. [DOI:10.1186/s13034-017-0164-5] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Singh Bal B, Singh D. An analysis of the components of emotional maturity and adjustment in combat sport athletes. American Journal of Applied Psychology. 2015; 4(1):13-20. [DOI:10.11648/j.ajap.20150401.13]

- Kumar B. Study of difference of emotional maturity among adolescents of Dehradun. The International Journal of Indian Psychology. 2018; 6(3):31-42. DOI:10.25215/0603.085

- Naylor PD, Labbé EE. Exploring the effects of group therapy for the visually impaired. British Journal of Visual Impairment 2017; 35(1):18-28. [DOI:10.1177/0264619616671976]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy, second edition: The process and practice of mindful change. New York: Guilford Publications; 2016. [Link]

- Bach PA, Moran DJ. ACT in practice: Case conceptualization in acceptance & commitment therapy. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications; 2008. [Link]

- Tajvar Rostami S, Rahimi F, Kazemi M. [Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment treatment in depression and spiritual well-being of blind girls in Shahrekord (Persian)]. Journal of Modern Psychological Researches. 2017; 11(44):75-88. [Link]

- Martens BK, Witt JC, Elliott SN, Darveaux DX. Teacher judgments concerning the acceptability of school-based interventions. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1985; 16(2):191-8. [DOI:10.1037//0735-7028.16.2.191]

- Pant P, Joshi PK. A comparative study of emotional stability of visually impaired students studying at secondary level in inclusive setup and special schools. Journal of Education and Practice. 2016; 7(22):53-8. [Link]

- Kallapiran K, Koo S, Kirubakaran R, Hancock K. Review: Effectiveness of mindfulness in improving mental health symptoms of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2015; 20(4):182-94. [DOI:10.1111/camh.12113] [PMID]

- Parua RK. Emotional development of children with visual impairment studying in integrated and special schools. International Journal of Advanced Research. 2015; 3(12):1345-8. [Link]

- Yari S, Noruzi A. [Emotions and emotion theories in information retrieval: Roles and applications (Persian)]. Library & Information Science Research. 2021; 10(2):29-320. [DOI:10.22067/INFOSCI.2021.23913.0]

- Manitsa I, Doikou M. Social support for students with visual impairments in educational institutions: An integrative literature review. British Journal of Visual Impairment. 2022; 40(1):29-47. [DOI:10.1177/0264619620941885]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Clinical Psycology

Received: 18/04/2023 | Accepted: 11/09/2023 | Published: 1/04/2024

Received: 18/04/2023 | Accepted: 11/09/2023 | Published: 1/04/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |