Volume 25, Issue 2 (Summer 2024)

jrehab 2024, 25(2): 232-247 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Maleki Roveshti M, Raei M, Valipour F. Examining Mental Workload and Incidence of Musculoskeletal Abnormalities of Dentists During Surgery. jrehab 2024; 25 (2) :232-247

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3285-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3285-en.html

1- Department of Occupational Health Engineering, School of Health, Baqiatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Baqiatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Occupational Health Engineering, School of Health, Baqiatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,firouzvalipour@mail.com

2- Department of Biostatistics, School of Health, Baqiatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Occupational Health Engineering, School of Health, Baqiatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 1764 kb]

(972 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5137 Views)

Full-Text: (1134 Views)

Introduction

Mental workload is one of the concepts of cognitive ergonomics [1]. Although there is no general definition of mental workload, the set of factors affecting the mental processing of information, decision-making, and the individual’s reaction in the work environment about a specific task is considered mental workload [2]. Excessive workload is one of the most important factors in dentists’ burnout [3, 4]. Also, the evaluation of this index is essential for the prevention and control of human errors in medical departments [5, 6]. To date, concerted efforts have been made to design surgical devices [7] with consideration for the volume of work of dental surgeons and dental assistants. Occupational activity in healthcare-healing systems has been classified as a high-risk profession for generating musculoskeletal-related deformities with a hierarchical classification [8]. Studies have shown that work-related musculoskeletal disorders can be the result of complex interactions between physical, psychological, social, biological, and individual characteristics. However, the evidence for a specific relationship has not yet been conclusively confirmed [9]. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders are one of the most serious health-medical problems that the working population faces and result in individuals suffering significant negative economic effects and consequences [10, 11]. In the field of human factors engineering and ergonomics, most studies have been focused on the physical needs and the work that dentists have to do and the relationship or interaction between these demands and musculoskeletal disorders [12]. Today, the examination of musculoskeletal disorders is much more complicated than before because the risks of these disorders are affected by the combination of a diverse set of psychosocial risks, in addition to known work-related risk factors [13].

Today, complex and modern systems require activities with a high mental workload [14]. Mental workload can be described as when tasks require alertness and concentration on an activity or group of activities over some time [15]. The workload in any activity includes physical workload and mental workload. Accordingly, the human capacity to interact with complex systems, along with considering equipment, training, organization, environmental restrictions, and so on plays a significant role in the correct performance of employees [16].

Each task or job requires a certain level of attention and concentration in terms of instructions and inferences, level of accuracy of response, and organizational aspects, especially those that refer to the organization of working time [17]. In this context, mental workload is defined as the amount of mental effort that must be developed to achieve a specific result and is related to the needs of information processing and decision-making for task execution. In contrast, physical workload is defined as a set of physical requirements by an individual to perform tasks. Many researchers state that the type of work and a person’s age have a significant effect on the physical capacity of employees [18]. Current working conditions have led to high levels of mental workload, mental fatigue, and stress, which reduce performance and concentration. At the same time, another effect is the number of errors, forgetfulness, and confusion, increasing the probability of accidents while performing tasks [19]. To ensure the safety of patients and the quality of service delivery, it is important to consider the factors that may affect the mental workload and physical workload of dentists [20].

Dentistry is a profession with a high prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders for doctors. These symptoms often begin in the early stages of their careers [12, 21]. Extensive research has been conducted on dentists’ workload and the prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Iran, revealing an increasing trend of these deformities among Iranian dentists [22, 23]. In the study of Eyvazlou et al., musculoskeletal discomfort was higher in dentists compared to other office workers, and most of the complaints were reported in the neck area [24]. The study by Koochak Dezfouli et al., which was conducted among dentists in Sari City, Iran, emphasized improving the conditions of the working environment in reducing musculoskeletal abnormalities [25]. With the increasing difficulty of working conditions and long working hours in hospitals, dentists’ productivity and performance are negatively affected. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct reliable and comprehensive ergonomic studies in this field to identify the causes of this problem with greater awareness and take appropriate measures. Accordingly, this study investigates the relationship between cognitive workload and the development of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in dentists.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at Shahid Shokri Dental Hospital in Tehran City, Iran in 2022. The sampling was done by the targeted sampling method and the sample size was calculated using the Cochran formula and resulted in 42 people. The criteria for entering the study were as follows: 1) Having at least one year of work experience in a dental hospital, 2) Ability to allocate time voluntarily to complete the required questionnaire, 3) Desire to participate in the study, and 4) Having expertise in dentistry. Also, the exclusion criteria comprised the following items: 1) No history of skeletal-muscular problems in different parts of the body, 2) No history of mental-psychological problems, and 3) No history of problems in the respiratory system and cardiovascular diseases. The collection of data related to these methods was done by direct observation and taking pictures from different angles to analyze the most repeated position of the body (posture). To collect demographic information about the participants, a questionnaire was designed that inquired about participant’s age, gender, weight, height, body mass index, work experience, level of education, and marital status. This study was conducted in two stages. At first, the Nordic self-report questionnaire was employed and then the NASA task load index (NASA-TLX) tool was used to collect the data. The Nordic questionnaire was presented by the Professional Health Association of the Scandinavian countries in 2010 and was used to determine the prevalence rate of musculoskeletal disorders in 3 different sections A, B, and C [26]. This questionnaire divides the human body into 9 anatomical regions (neck, shoulder, elbow, hand/wrist, upper back, waist, thigh/hip, knee, foot/ankle). These anatomical regions were selected according to the following two criteria: a) the organs in which the symptoms are concentrated, and b) the organs that can be distinguished from each other by both the respondent and the researcher. In part A, the question is framed as “Have you had pain, discomfort, burning, or numbness in any of the specified areas in the last 12 months?”. In part B, the question is formed as follows: “In the past 7 days in which of the specified areas have you had pain, discomfort, burning, or numbness?” Finally, in part C, the question is presented as follows: “In the last 12 months in which of the specified areas due to pain or discomfort have you had to rest or reduce work activity, leave the workplace, or be unable to perform activities at work or home?”

The reliability and validity of this questionnaire have been confirmed in different versions, including the Persian version [27]. The Nordic questionnaire is designed to answer the general question of whether skeletal-muscular problems occur for a certain population and if so, in which of the body’s organs are these disorders more concentrated. Anatomical areas were selected according to the following two criteria: a) The organs where the symptoms are concentrated and b) The organs that can be distinguished from each other by the respondent and the researcher. NASA-TLX is a versatile tool and provides a multifaceted process available with different ratings designed to assess the perceptual aspects of mental workload. The mental workload tool, as the most powerful tool, provides a model to estimate the mental workload by using 6 scales mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, effort, performance, and frustration. This questionnaire was first developed by Hart and Steveland in 1988 at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (AMES NASA Research Center) to assess mental workload [16]. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire in Iran has been confirmed by Mohammadi et al. and the Cronbach α coefficient was calculated at 0.847 [28]. The process of evaluating the mental workload using the NASA-TLX model includes three steps that will be carried out as follows. The first step is to determine the load weight of each of the six scales (weight), the purpose of which is to specify the priority of the six scales of TLX. At this stage, all the scales are evaluated and selected by the employees in pairs and 15 different modes, and then each of the workload dimensions is determined between 0 and 1. The second step is to determine the rating (level) of each of the six scales (measures), to assess the influence of each of the six factors on cognitive workload. The weighted average score of each scale is calculated based on the number of times the cognitive workload-related factor is selected in the paired selection of each participant. Then, the total weighted scores (which is 15) are divided. The data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 26, in addition to descriptive statistics and statistical tests of the t-test, the Fisher exact test, and logistic regression at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

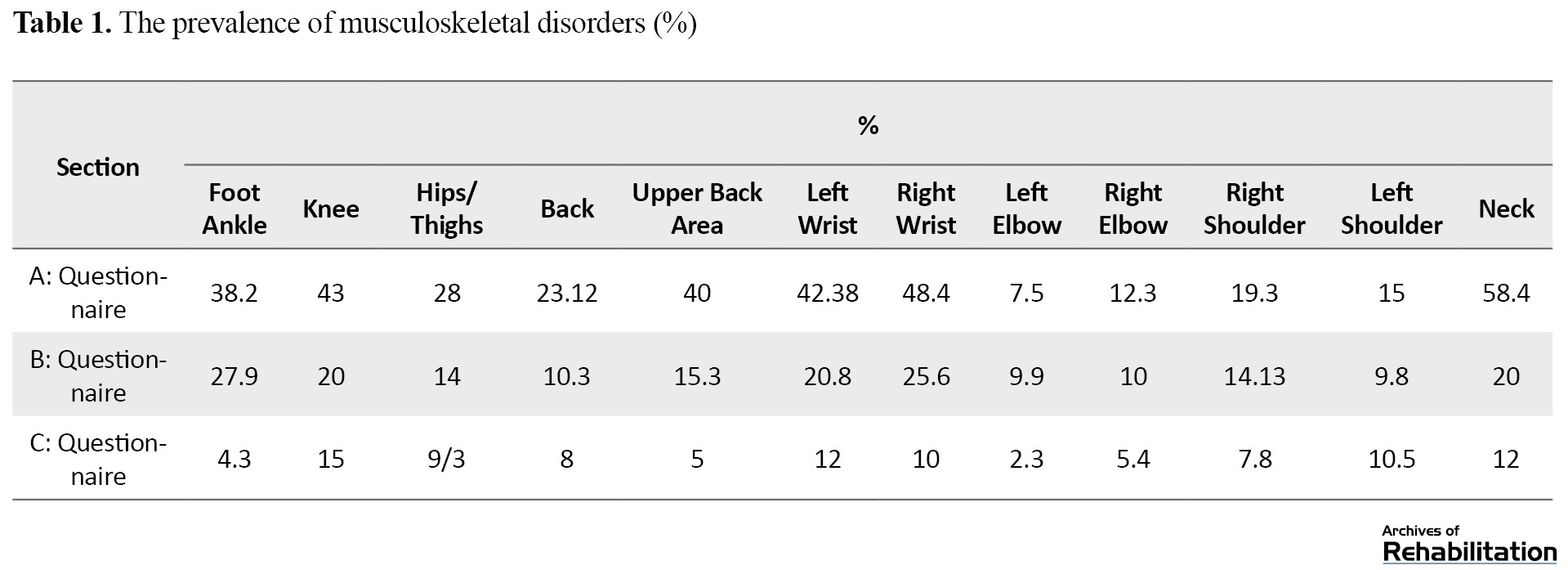

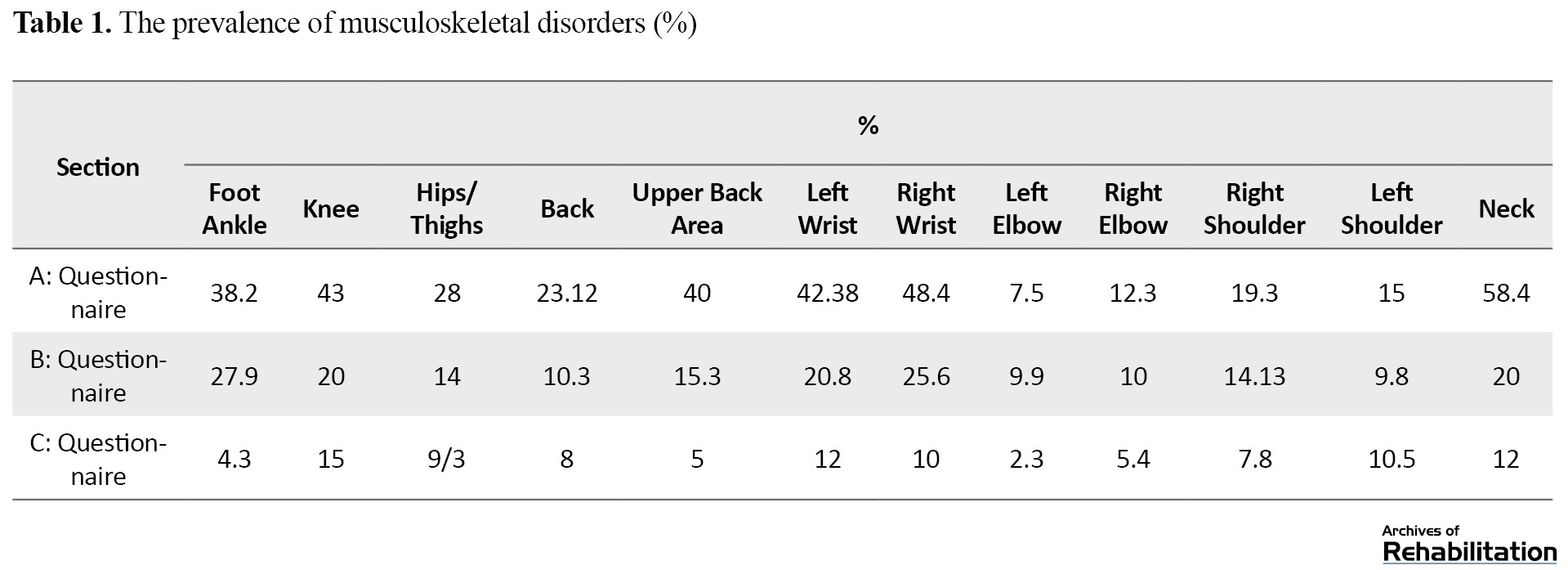

The percentage of the overall prevalence with at least one report of discomfort in each of the nine areas of the body during the last 12 months for men and women was equal to 78.34% and 99.84%, respectively. Also, the percentage of overall prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in the entire community with minimal discomfort in one member was calculated at 92.93%. Other details of the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders based on the Nordic questionnaire in nine body regions are reported in Table 1.

As shown in Figure 1, the average percentage of neck, left shoulder, right shoulder, right elbow, left elbow, right wrist, left wrist, upper back, waist, hip and thigh, knee and ankle disorders are as follows: 30.1%, 11.76%, 13.74%, 9.23%, 6.56%, 28%, 25.6%, 20.1/1, 13.8%, 17.1%, 26%, 23.46%. According to the Nordic questionnaire, there are more neck disorders than other areas of the body.

The relationship between the disorders of the examined organs in the Nordic questionnaire with age and work experience was investigated; accordingly, there is a significant relationship between the disorders of different parts and the influencing factors (P=0.001). Questionnaires were analyzed based on two age groups <35 years and >35 years. The most musculoskeletal disorders were for the age group over 35 years old, where 34.37% of people had musculoskeletal disorders in different parts of their bodies. Among the people in the age group <35 years old, 28.9% of people had musculoskeletal disorders. Also, for the work experience, the questionnaires were examined based on two groups of with experience of <10 years and >10 years. The most musculoskeletal disorders were for the group with >10 years of work experience, where 37.43% of people had musculoskeletal disorders in different parts of their body. Among the people in the group with <10 years of work experience, 31.06% had musculoskeletal disorders.

Mental workload

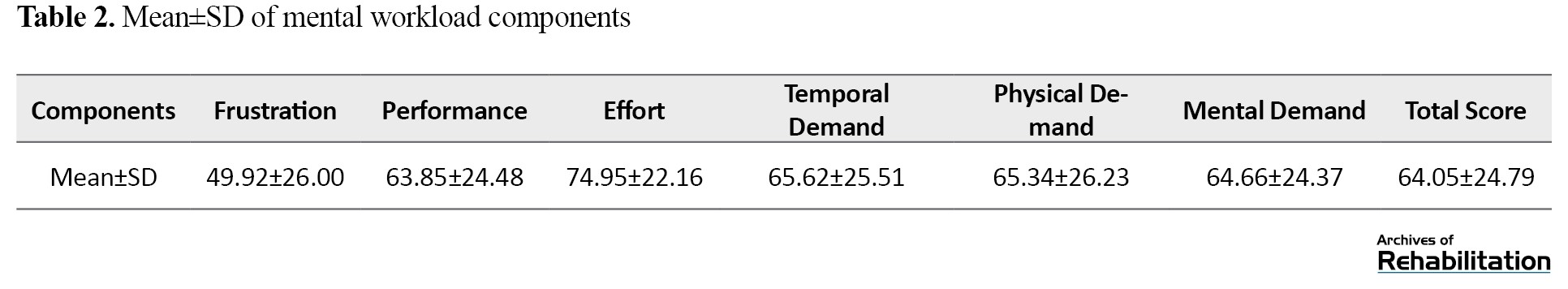

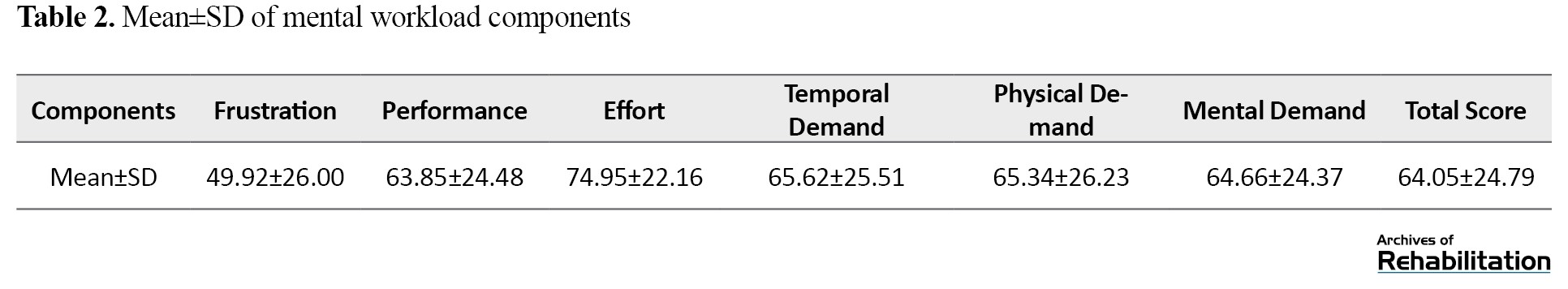

According to the results of the evaluation of mental workload, in this study, the effort level component with the Mean±SD of 74.95±22.16 has the highest score, and feeling discouraged with the Mean±SD of 49.92±26 has the lowest score compared to other components. Other results are reported in Table 2.

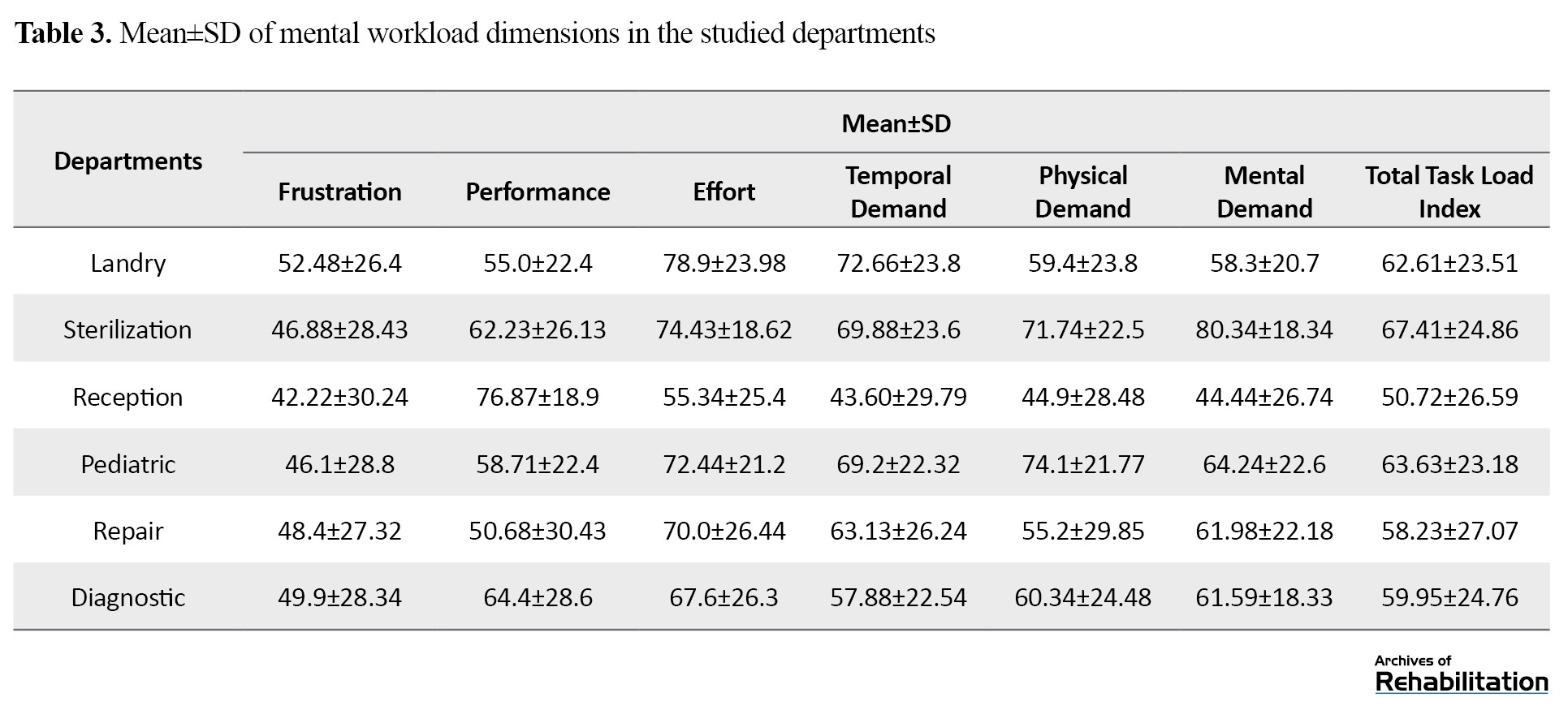

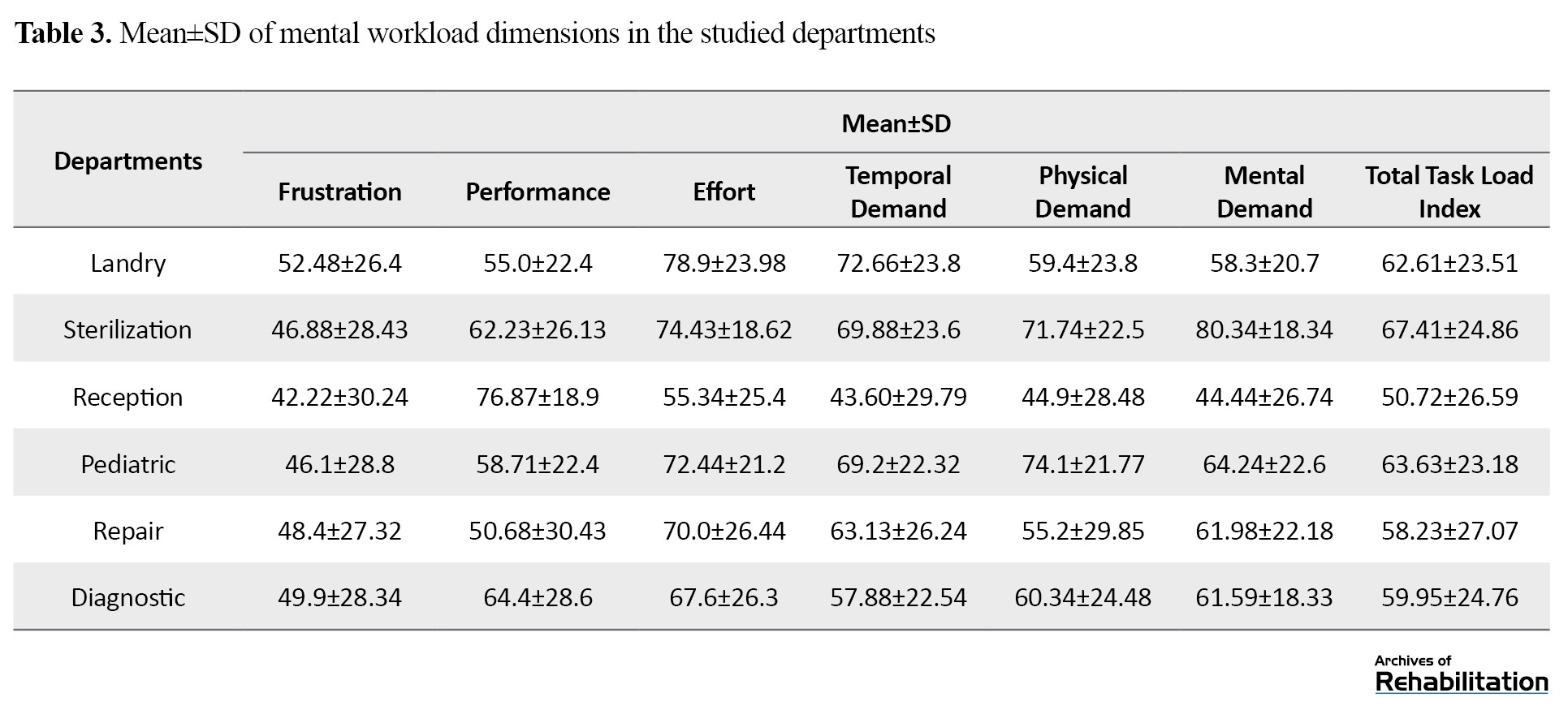

The examination of the mental demand by different departments showed that the sterilization department with the Mean±SD of 67.41±24.86 had a higher mental demand than other departments and the reception department with the Mean±SD of 50.72±26.59 had a lower mental workload than other subjects (Table 3).

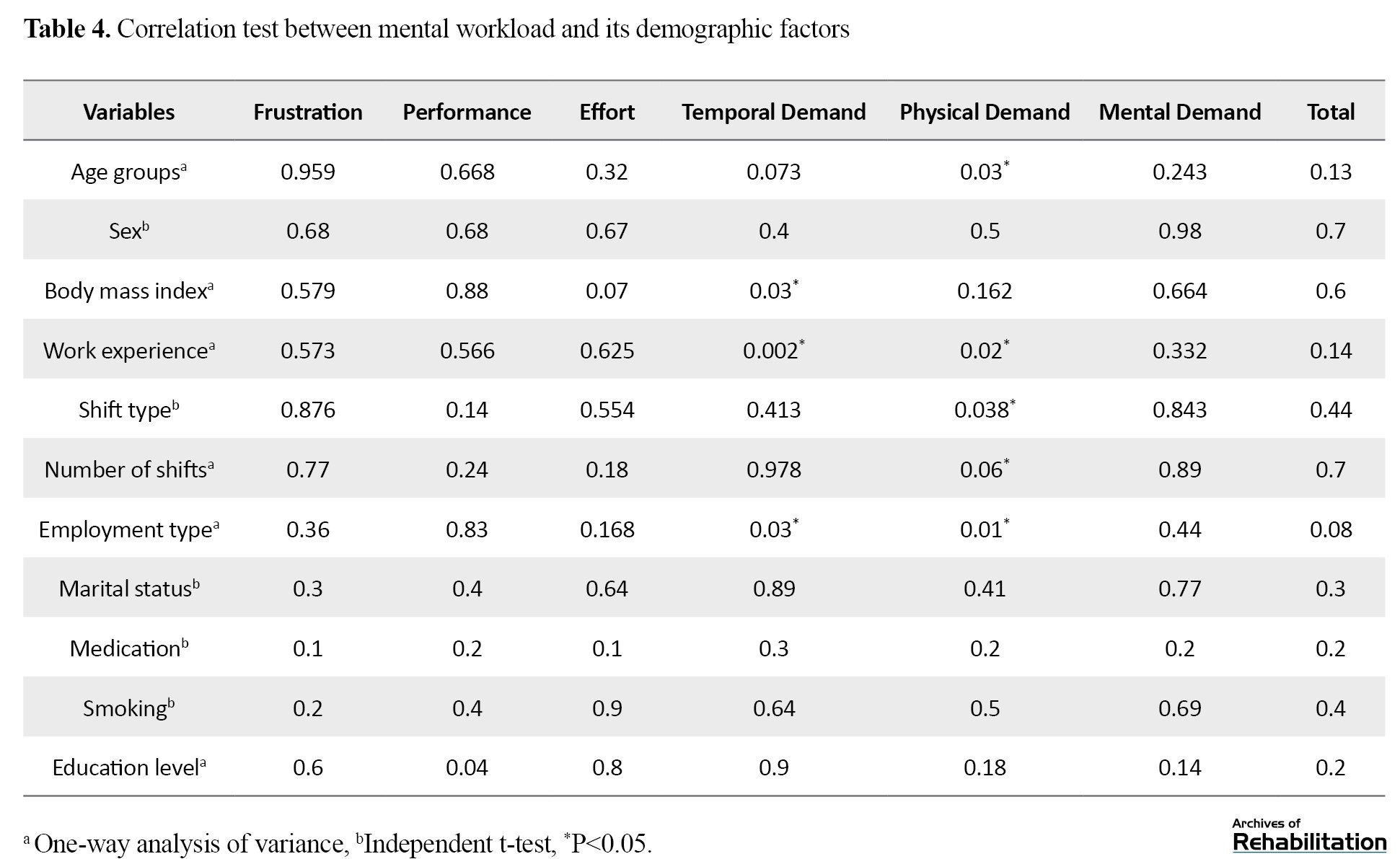

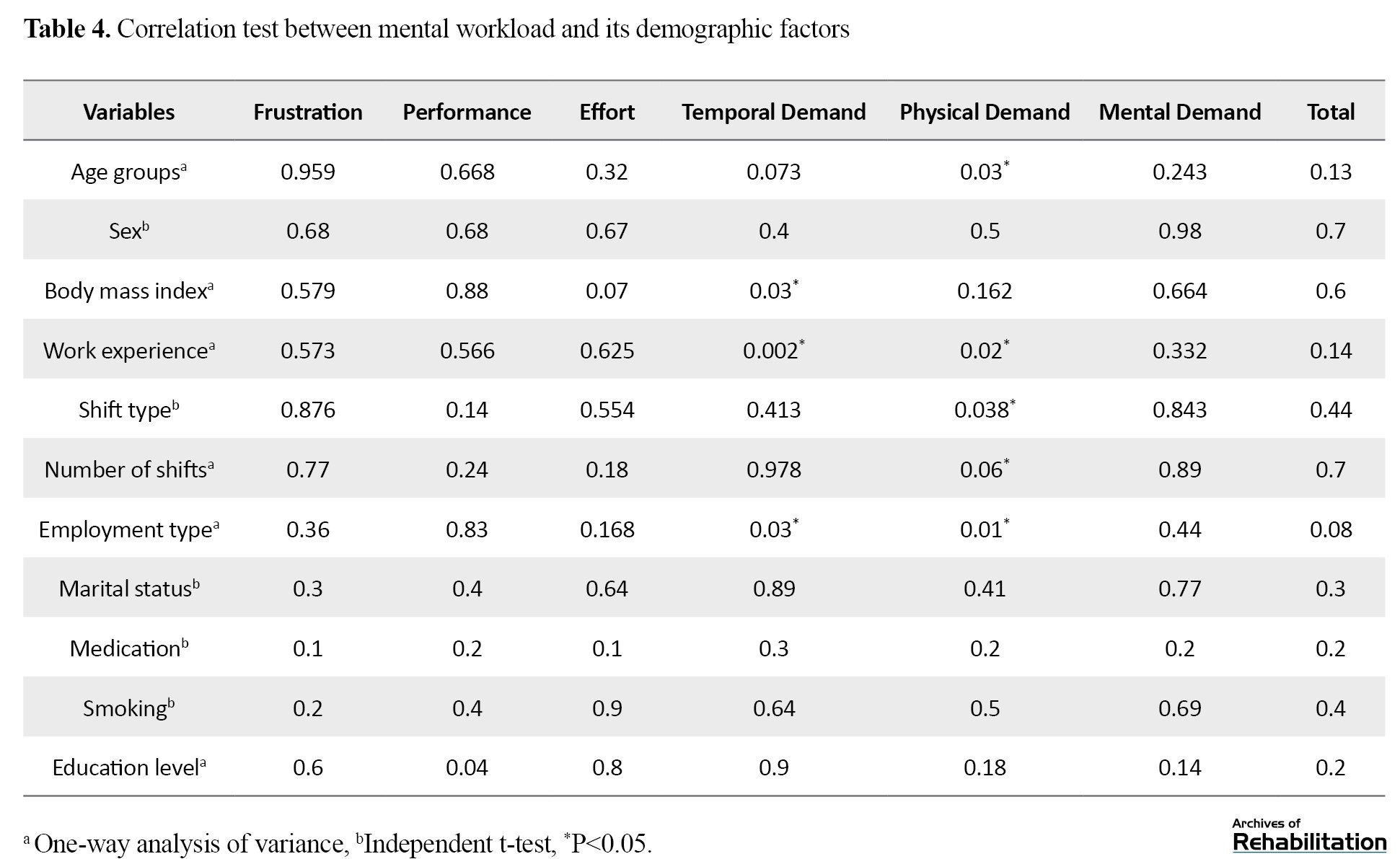

Table 4 shows the relationship between mental workload and its components with demographic and contextual factors.

The physical demand component had a significant relationship with age group, service history, type of shift, number of shifts, and type of employment (P=0.03). The Temporal demand component showed a statistically significant relationship with body mass index, service history, and type of employment (P=0.001). Also, a significant relationship was found between the effort component and body mass index (P=0.01). The independent t-tests and the one-way analysis of variance did not show a significant relationship between the total mental workload and the variables of age, gender, marital status, education level, service history, employment status, number of shifts, and shift work (P>0/05).

Discussion

The results showed that the average percentage of disorders are as follows: Neck area=30.1%, left shoulder=11.76%, right shoulder=13.74%, right elbow=9.23%, left elbow=6.56%, right wrist=28%, left-hand wrist=25.06%, upper back area=20.1%, waist=13.8%, hip and thigh=1.17%, knee=26%, and ankle=23.46%. Age and work experience had a significant relationship with the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders. Meanwhile, the effort component with a Mean±SD of 74.95±22.16 had the highest score, and discouragement with a Mean±SD of 49.92±26 received the lowest score compared to other components. The sterilization department with a Mean±SD of 67.41±24.86 showed a higher mental workload than other departments and the reception department with a Mean±SD of 50.72±26.59 had less mental workload than other cases. The chances of suffering from musculoskeletal disorders in the neck, wrist/hand, and back areas in employees with more than 10 years of work experience are about 6.5, 5.5, and 10 times, respectively, compared to employees with less than 10 years of work experience. In the same way, the chances of having musculoskeletal disorders in the neck and back areas in employees who work more than 10 h a day are about 5.5 and 5.8 times, respectively, compared to employees who work less than 10 h. According to the results of the Nordic questionnaire, musculoskeletal disorders among the employees of this hospital had a very high prevalence. Accordingly, the organs of the neck (30.1%), back (28%), and right shoulder (26%) had the highest prevalence of disorders. In this regard, Besharti et al. obtained results similar to the results of the present study. The results of their study showed a high prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders during the past 12 months, which was reported to be the most prevalent in the neck (60.16%), back (57.10%) and shoulder (54.03%) organs [29]. In the study of Gholami et al., who investigated musculoskeletal disorders among the employees of a medical university, the lower back (60.7%) and neck (50.9%) were the most common [30]. Also, in Pirmoradi et al.’s study, the neck (51.94%) and back (41.5%) [31], and in Heidarimoghadam et al.’s study neck (56.7%) and shoulder (40%) have the highest prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders [14]. In the cohort study of Collins et al., who investigated the mentioned disorders in two educational institutions, similar to the findings of this study, neck (58%), shoulder (57%), and back (51%) organs were at the highest risk of infection [32]. The results showed that the prevalence of symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders among the employees of this hospital is high. Overall, 70% of the employees have reported the symptoms of these disorders in at least one area of the musculoskeletal system, and since most of the employees are in the age range of 30-40 years, the problems related to the musculoskeletal system in this job are significant and employees are at high risk of suffering from these disorders. However, these conditions can be caused by the lack of adjustment of the equipment or the use of non-adjustable equipment. According to the present study, since the most prevalent musculoskeletal disorders were in the neck area, it is suggested to use height-adjustable monitor holders, for example, in office work. It is also recommended to train employees not to keep the phone between their neck and shoulder. It is necessary to use chairs with proper support for the back, with the ability to adjust the height and height of the forearm support to reduce the risk of factors involved in musculoskeletal disorders related to the back and shoulders. Designing and modifying workstations based on ergonomic principles, such as arranging the necessary equipment at the workplace in such a way that the person is forced to leave the sitting position. Installing software that reminds you to perform stretching and stretching exercises on staff computers, and setting appropriate work schedules in terms of the amount of rest and work are among the factors that reduce the risk of musculoskeletal disorders in the different areas investigated in this research. In the present study, the effort level component with a Mean±SD of 74.95±22.16 had the highest score, and the feeling of discouragement with a Mean±SD of 49.92±26 had the lowest score compared to other components. Also, in Jonker’s study conducted in 2009, the results showed that the position of the head and upper limbs among dentists is inappropriate [33]. In 2013, Habibi et al. investigated the relationship between mental workload and musculoskeletal disorders among nurses at Al-Zahra Hospital using the NASA-TLX and the Cornell questionnaire. The results showed a significant relationship between the amount of musculoskeletal discomfort of nurses with the dimensions of frustration burden, total burden, time requirement, effort, and physical requirement, respectively (0.211, 0.216, 0.277, 0.277, 0.304); however, there was no direct relationship between the dimensions of performance workload and mental demand with the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among nurses (r=0.05, P<0.304) [34]. The obtained results of the mental workload in the entire studied sample are in line with the research of Sarsangi et al., which was conducted in 2013 on the nurses of hospitals in Kashan City, Iran, In this study, among the workload components, age, type of shift, number of shifts and The type of employment had a significant relationship (P<0.05), which is similar to the study by Sarsangi et al. [5]. In this study, no significant relationship was found between workload and all demographic variables and background factors (P>0.05); however, in the study of figures between age, work experience and shift work, a significant relationship was found (P<0.05) [35]. In this study, the highest score was related to the effort level factor, which is in line with Mazur et al.’s studies, which can be attributed to the low number of workforce and high volume of work [36]. The average total workload was higher than the average and compared to Zakerian et al.’s study which was conducted on the nurses of two big hospitals in Tehran City, Iran, it is consistent [37]. Also, the highest score in both studies was related to the level of effort. The score of temporal demand was high in all the departments under study, while Fottler et al. found in their study that medical workers do not have enough time to provide adequate services [38]. In the study of workload in Urmia City, Iran, nurses conducted by Malekpour et al., the discouragement score was much higher compared to the present study [39]. The reason for this difference can be found in the organizational climate. It is also necessary to investigate other harmful ergonomic and physical factors of the work environment (such as noise, lighting, heat stress, etc.) of the administrative staff of other organizations [40].

Conclusion

The findings of the present study showed that the current situation and conditions in Shahid Shokri Dental Hospital are not in a proper position and require changes and improvement of conditions and workstations. Increasing the awareness of employees regarding ergonomic risk factors can improve the conditions. On the other hand, considering the tremendous impact of training on the improvement of workstations, during a suitable training program, this matter should be given special attention and the necessary knowledge should be given to the employees in this field. Because even though more than 40% of the employees in the present study were familiar with ergonomics and its role in their health, this did not have much effect on maintaining their musculoskeletal health. Also, high work history and the number of working hours per day were effective factors in the occurrence of symptoms in the neck and wrist/hand areas. It is suggested that in future studies, the solutions presented in this study should be used to improve the ergonomic status of employees to conduct intervention studies, and after the implementation of the aforementioned interventions, a study can be conducted to determine the effectiveness of the reforms made among employees.

Study limitations

Due to the inherent limitations of cross-sectional studies and the data collection method, which was self-reported, caution should be observed in the interpretation of the findings of the present study. In collecting data by self-report method, there is a problem of remembering the symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders. The employees participating in the present study were all active and engaged in the workforce; therefore, employees who temporarily or permanently quit their jobs due to musculoskeletal disorders were not included in the study. Accordingly, there is a possibility of a healthy work effect. As a result, the results of the present study may have underestimated the prevalence of symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders than what exists. The unwillingness of several employees in the study company, the non-cooperation of several participants in answering some questions, as well as the possibility of a non-routine physical state during the assessment of the physical state by the researcher, are other limitations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (Code: BMSU. BAQ. REC.1401.005).

Funding

This study was extracted from the research project of Mehran Maleki Roushti in the Department of Occupational Health Engineering of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: IR.BMSU.BAQ.REC.1401.005).

Authors' contributions

Statistical analysis: Mehdi Raei; Study supervision: Firouz Valipour and Mehdi Raee; Writing the manuscript: Mehran Maleki Roushti.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express his gratitude to all the staff of Shahid Shokri Dental Hospital.

References

Mental workload is one of the concepts of cognitive ergonomics [1]. Although there is no general definition of mental workload, the set of factors affecting the mental processing of information, decision-making, and the individual’s reaction in the work environment about a specific task is considered mental workload [2]. Excessive workload is one of the most important factors in dentists’ burnout [3, 4]. Also, the evaluation of this index is essential for the prevention and control of human errors in medical departments [5, 6]. To date, concerted efforts have been made to design surgical devices [7] with consideration for the volume of work of dental surgeons and dental assistants. Occupational activity in healthcare-healing systems has been classified as a high-risk profession for generating musculoskeletal-related deformities with a hierarchical classification [8]. Studies have shown that work-related musculoskeletal disorders can be the result of complex interactions between physical, psychological, social, biological, and individual characteristics. However, the evidence for a specific relationship has not yet been conclusively confirmed [9]. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders are one of the most serious health-medical problems that the working population faces and result in individuals suffering significant negative economic effects and consequences [10, 11]. In the field of human factors engineering and ergonomics, most studies have been focused on the physical needs and the work that dentists have to do and the relationship or interaction between these demands and musculoskeletal disorders [12]. Today, the examination of musculoskeletal disorders is much more complicated than before because the risks of these disorders are affected by the combination of a diverse set of psychosocial risks, in addition to known work-related risk factors [13].

Today, complex and modern systems require activities with a high mental workload [14]. Mental workload can be described as when tasks require alertness and concentration on an activity or group of activities over some time [15]. The workload in any activity includes physical workload and mental workload. Accordingly, the human capacity to interact with complex systems, along with considering equipment, training, organization, environmental restrictions, and so on plays a significant role in the correct performance of employees [16].

Each task or job requires a certain level of attention and concentration in terms of instructions and inferences, level of accuracy of response, and organizational aspects, especially those that refer to the organization of working time [17]. In this context, mental workload is defined as the amount of mental effort that must be developed to achieve a specific result and is related to the needs of information processing and decision-making for task execution. In contrast, physical workload is defined as a set of physical requirements by an individual to perform tasks. Many researchers state that the type of work and a person’s age have a significant effect on the physical capacity of employees [18]. Current working conditions have led to high levels of mental workload, mental fatigue, and stress, which reduce performance and concentration. At the same time, another effect is the number of errors, forgetfulness, and confusion, increasing the probability of accidents while performing tasks [19]. To ensure the safety of patients and the quality of service delivery, it is important to consider the factors that may affect the mental workload and physical workload of dentists [20].

Dentistry is a profession with a high prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders for doctors. These symptoms often begin in the early stages of their careers [12, 21]. Extensive research has been conducted on dentists’ workload and the prevalence of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Iran, revealing an increasing trend of these deformities among Iranian dentists [22, 23]. In the study of Eyvazlou et al., musculoskeletal discomfort was higher in dentists compared to other office workers, and most of the complaints were reported in the neck area [24]. The study by Koochak Dezfouli et al., which was conducted among dentists in Sari City, Iran, emphasized improving the conditions of the working environment in reducing musculoskeletal abnormalities [25]. With the increasing difficulty of working conditions and long working hours in hospitals, dentists’ productivity and performance are negatively affected. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct reliable and comprehensive ergonomic studies in this field to identify the causes of this problem with greater awareness and take appropriate measures. Accordingly, this study investigates the relationship between cognitive workload and the development of work-related musculoskeletal disorders in dentists.

Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional descriptive study was conducted at Shahid Shokri Dental Hospital in Tehran City, Iran in 2022. The sampling was done by the targeted sampling method and the sample size was calculated using the Cochran formula and resulted in 42 people. The criteria for entering the study were as follows: 1) Having at least one year of work experience in a dental hospital, 2) Ability to allocate time voluntarily to complete the required questionnaire, 3) Desire to participate in the study, and 4) Having expertise in dentistry. Also, the exclusion criteria comprised the following items: 1) No history of skeletal-muscular problems in different parts of the body, 2) No history of mental-psychological problems, and 3) No history of problems in the respiratory system and cardiovascular diseases. The collection of data related to these methods was done by direct observation and taking pictures from different angles to analyze the most repeated position of the body (posture). To collect demographic information about the participants, a questionnaire was designed that inquired about participant’s age, gender, weight, height, body mass index, work experience, level of education, and marital status. This study was conducted in two stages. At first, the Nordic self-report questionnaire was employed and then the NASA task load index (NASA-TLX) tool was used to collect the data. The Nordic questionnaire was presented by the Professional Health Association of the Scandinavian countries in 2010 and was used to determine the prevalence rate of musculoskeletal disorders in 3 different sections A, B, and C [26]. This questionnaire divides the human body into 9 anatomical regions (neck, shoulder, elbow, hand/wrist, upper back, waist, thigh/hip, knee, foot/ankle). These anatomical regions were selected according to the following two criteria: a) the organs in which the symptoms are concentrated, and b) the organs that can be distinguished from each other by both the respondent and the researcher. In part A, the question is framed as “Have you had pain, discomfort, burning, or numbness in any of the specified areas in the last 12 months?”. In part B, the question is formed as follows: “In the past 7 days in which of the specified areas have you had pain, discomfort, burning, or numbness?” Finally, in part C, the question is presented as follows: “In the last 12 months in which of the specified areas due to pain or discomfort have you had to rest or reduce work activity, leave the workplace, or be unable to perform activities at work or home?”

The reliability and validity of this questionnaire have been confirmed in different versions, including the Persian version [27]. The Nordic questionnaire is designed to answer the general question of whether skeletal-muscular problems occur for a certain population and if so, in which of the body’s organs are these disorders more concentrated. Anatomical areas were selected according to the following two criteria: a) The organs where the symptoms are concentrated and b) The organs that can be distinguished from each other by the respondent and the researcher. NASA-TLX is a versatile tool and provides a multifaceted process available with different ratings designed to assess the perceptual aspects of mental workload. The mental workload tool, as the most powerful tool, provides a model to estimate the mental workload by using 6 scales mental demand, physical demand, temporal demand, effort, performance, and frustration. This questionnaire was first developed by Hart and Steveland in 1988 at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (AMES NASA Research Center) to assess mental workload [16]. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire in Iran has been confirmed by Mohammadi et al. and the Cronbach α coefficient was calculated at 0.847 [28]. The process of evaluating the mental workload using the NASA-TLX model includes three steps that will be carried out as follows. The first step is to determine the load weight of each of the six scales (weight), the purpose of which is to specify the priority of the six scales of TLX. At this stage, all the scales are evaluated and selected by the employees in pairs and 15 different modes, and then each of the workload dimensions is determined between 0 and 1. The second step is to determine the rating (level) of each of the six scales (measures), to assess the influence of each of the six factors on cognitive workload. The weighted average score of each scale is calculated based on the number of times the cognitive workload-related factor is selected in the paired selection of each participant. Then, the total weighted scores (which is 15) are divided. The data were analyzed using the SPSS software, version 26, in addition to descriptive statistics and statistical tests of the t-test, the Fisher exact test, and logistic regression at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

The percentage of the overall prevalence with at least one report of discomfort in each of the nine areas of the body during the last 12 months for men and women was equal to 78.34% and 99.84%, respectively. Also, the percentage of overall prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders in the entire community with minimal discomfort in one member was calculated at 92.93%. Other details of the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders based on the Nordic questionnaire in nine body regions are reported in Table 1.

As shown in Figure 1, the average percentage of neck, left shoulder, right shoulder, right elbow, left elbow, right wrist, left wrist, upper back, waist, hip and thigh, knee and ankle disorders are as follows: 30.1%, 11.76%, 13.74%, 9.23%, 6.56%, 28%, 25.6%, 20.1/1, 13.8%, 17.1%, 26%, 23.46%. According to the Nordic questionnaire, there are more neck disorders than other areas of the body.

The relationship between the disorders of the examined organs in the Nordic questionnaire with age and work experience was investigated; accordingly, there is a significant relationship between the disorders of different parts and the influencing factors (P=0.001). Questionnaires were analyzed based on two age groups <35 years and >35 years. The most musculoskeletal disorders were for the age group over 35 years old, where 34.37% of people had musculoskeletal disorders in different parts of their bodies. Among the people in the age group <35 years old, 28.9% of people had musculoskeletal disorders. Also, for the work experience, the questionnaires were examined based on two groups of with experience of <10 years and >10 years. The most musculoskeletal disorders were for the group with >10 years of work experience, where 37.43% of people had musculoskeletal disorders in different parts of their body. Among the people in the group with <10 years of work experience, 31.06% had musculoskeletal disorders.

Mental workload

According to the results of the evaluation of mental workload, in this study, the effort level component with the Mean±SD of 74.95±22.16 has the highest score, and feeling discouraged with the Mean±SD of 49.92±26 has the lowest score compared to other components. Other results are reported in Table 2.

The examination of the mental demand by different departments showed that the sterilization department with the Mean±SD of 67.41±24.86 had a higher mental demand than other departments and the reception department with the Mean±SD of 50.72±26.59 had a lower mental workload than other subjects (Table 3).

Table 4 shows the relationship between mental workload and its components with demographic and contextual factors.

The physical demand component had a significant relationship with age group, service history, type of shift, number of shifts, and type of employment (P=0.03). The Temporal demand component showed a statistically significant relationship with body mass index, service history, and type of employment (P=0.001). Also, a significant relationship was found between the effort component and body mass index (P=0.01). The independent t-tests and the one-way analysis of variance did not show a significant relationship between the total mental workload and the variables of age, gender, marital status, education level, service history, employment status, number of shifts, and shift work (P>0/05).

Discussion

The results showed that the average percentage of disorders are as follows: Neck area=30.1%, left shoulder=11.76%, right shoulder=13.74%, right elbow=9.23%, left elbow=6.56%, right wrist=28%, left-hand wrist=25.06%, upper back area=20.1%, waist=13.8%, hip and thigh=1.17%, knee=26%, and ankle=23.46%. Age and work experience had a significant relationship with the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders. Meanwhile, the effort component with a Mean±SD of 74.95±22.16 had the highest score, and discouragement with a Mean±SD of 49.92±26 received the lowest score compared to other components. The sterilization department with a Mean±SD of 67.41±24.86 showed a higher mental workload than other departments and the reception department with a Mean±SD of 50.72±26.59 had less mental workload than other cases. The chances of suffering from musculoskeletal disorders in the neck, wrist/hand, and back areas in employees with more than 10 years of work experience are about 6.5, 5.5, and 10 times, respectively, compared to employees with less than 10 years of work experience. In the same way, the chances of having musculoskeletal disorders in the neck and back areas in employees who work more than 10 h a day are about 5.5 and 5.8 times, respectively, compared to employees who work less than 10 h. According to the results of the Nordic questionnaire, musculoskeletal disorders among the employees of this hospital had a very high prevalence. Accordingly, the organs of the neck (30.1%), back (28%), and right shoulder (26%) had the highest prevalence of disorders. In this regard, Besharti et al. obtained results similar to the results of the present study. The results of their study showed a high prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders during the past 12 months, which was reported to be the most prevalent in the neck (60.16%), back (57.10%) and shoulder (54.03%) organs [29]. In the study of Gholami et al., who investigated musculoskeletal disorders among the employees of a medical university, the lower back (60.7%) and neck (50.9%) were the most common [30]. Also, in Pirmoradi et al.’s study, the neck (51.94%) and back (41.5%) [31], and in Heidarimoghadam et al.’s study neck (56.7%) and shoulder (40%) have the highest prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders [14]. In the cohort study of Collins et al., who investigated the mentioned disorders in two educational institutions, similar to the findings of this study, neck (58%), shoulder (57%), and back (51%) organs were at the highest risk of infection [32]. The results showed that the prevalence of symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders among the employees of this hospital is high. Overall, 70% of the employees have reported the symptoms of these disorders in at least one area of the musculoskeletal system, and since most of the employees are in the age range of 30-40 years, the problems related to the musculoskeletal system in this job are significant and employees are at high risk of suffering from these disorders. However, these conditions can be caused by the lack of adjustment of the equipment or the use of non-adjustable equipment. According to the present study, since the most prevalent musculoskeletal disorders were in the neck area, it is suggested to use height-adjustable monitor holders, for example, in office work. It is also recommended to train employees not to keep the phone between their neck and shoulder. It is necessary to use chairs with proper support for the back, with the ability to adjust the height and height of the forearm support to reduce the risk of factors involved in musculoskeletal disorders related to the back and shoulders. Designing and modifying workstations based on ergonomic principles, such as arranging the necessary equipment at the workplace in such a way that the person is forced to leave the sitting position. Installing software that reminds you to perform stretching and stretching exercises on staff computers, and setting appropriate work schedules in terms of the amount of rest and work are among the factors that reduce the risk of musculoskeletal disorders in the different areas investigated in this research. In the present study, the effort level component with a Mean±SD of 74.95±22.16 had the highest score, and the feeling of discouragement with a Mean±SD of 49.92±26 had the lowest score compared to other components. Also, in Jonker’s study conducted in 2009, the results showed that the position of the head and upper limbs among dentists is inappropriate [33]. In 2013, Habibi et al. investigated the relationship between mental workload and musculoskeletal disorders among nurses at Al-Zahra Hospital using the NASA-TLX and the Cornell questionnaire. The results showed a significant relationship between the amount of musculoskeletal discomfort of nurses with the dimensions of frustration burden, total burden, time requirement, effort, and physical requirement, respectively (0.211, 0.216, 0.277, 0.277, 0.304); however, there was no direct relationship between the dimensions of performance workload and mental demand with the prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among nurses (r=0.05, P<0.304) [34]. The obtained results of the mental workload in the entire studied sample are in line with the research of Sarsangi et al., which was conducted in 2013 on the nurses of hospitals in Kashan City, Iran, In this study, among the workload components, age, type of shift, number of shifts and The type of employment had a significant relationship (P<0.05), which is similar to the study by Sarsangi et al. [5]. In this study, no significant relationship was found between workload and all demographic variables and background factors (P>0.05); however, in the study of figures between age, work experience and shift work, a significant relationship was found (P<0.05) [35]. In this study, the highest score was related to the effort level factor, which is in line with Mazur et al.’s studies, which can be attributed to the low number of workforce and high volume of work [36]. The average total workload was higher than the average and compared to Zakerian et al.’s study which was conducted on the nurses of two big hospitals in Tehran City, Iran, it is consistent [37]. Also, the highest score in both studies was related to the level of effort. The score of temporal demand was high in all the departments under study, while Fottler et al. found in their study that medical workers do not have enough time to provide adequate services [38]. In the study of workload in Urmia City, Iran, nurses conducted by Malekpour et al., the discouragement score was much higher compared to the present study [39]. The reason for this difference can be found in the organizational climate. It is also necessary to investigate other harmful ergonomic and physical factors of the work environment (such as noise, lighting, heat stress, etc.) of the administrative staff of other organizations [40].

Conclusion

The findings of the present study showed that the current situation and conditions in Shahid Shokri Dental Hospital are not in a proper position and require changes and improvement of conditions and workstations. Increasing the awareness of employees regarding ergonomic risk factors can improve the conditions. On the other hand, considering the tremendous impact of training on the improvement of workstations, during a suitable training program, this matter should be given special attention and the necessary knowledge should be given to the employees in this field. Because even though more than 40% of the employees in the present study were familiar with ergonomics and its role in their health, this did not have much effect on maintaining their musculoskeletal health. Also, high work history and the number of working hours per day were effective factors in the occurrence of symptoms in the neck and wrist/hand areas. It is suggested that in future studies, the solutions presented in this study should be used to improve the ergonomic status of employees to conduct intervention studies, and after the implementation of the aforementioned interventions, a study can be conducted to determine the effectiveness of the reforms made among employees.

Study limitations

Due to the inherent limitations of cross-sectional studies and the data collection method, which was self-reported, caution should be observed in the interpretation of the findings of the present study. In collecting data by self-report method, there is a problem of remembering the symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders. The employees participating in the present study were all active and engaged in the workforce; therefore, employees who temporarily or permanently quit their jobs due to musculoskeletal disorders were not included in the study. Accordingly, there is a possibility of a healthy work effect. As a result, the results of the present study may have underestimated the prevalence of symptoms of musculoskeletal disorders than what exists. The unwillingness of several employees in the study company, the non-cooperation of several participants in answering some questions, as well as the possibility of a non-routine physical state during the assessment of the physical state by the researcher, are other limitations.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (Code: BMSU. BAQ. REC.1401.005).

Funding

This study was extracted from the research project of Mehran Maleki Roushti in the Department of Occupational Health Engineering of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences (Grant No.: IR.BMSU.BAQ.REC.1401.005).

Authors' contributions

Statistical analysis: Mehdi Raei; Study supervision: Firouz Valipour and Mehdi Raee; Writing the manuscript: Mehran Maleki Roushti.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express his gratitude to all the staff of Shahid Shokri Dental Hospital.

References

- Salehi Sahlabadi A, Asgari Gandomani E, Abbasi Balochkhaneh F, Mousavi Kordmiri SH. [The effect of mental workload on job performance with the mediating role of job stress (Persian)]. Journal of Occupational Hygiene Engineering. 2022; 9(1):19-28. [DOI:10.61186/johe.9.1.19]

- Fallahi M, Motamedzade M, Sharifi Z, Heidari Moghaddam R, Soltanian A. [The impact of mental workload levels on physiological and subjective responses (Persian)]. Journal of Ergonomics. 2016; 4(3):11-8. [DOI:10.21859/joe-04032]

- Kaveh M, Sheikhlar Z, Akbari H, Saberi H, Motalebi-Kashani M. [Correlation between job mental load and sleep quality with occupational burnout in non-clinical faculty members of Kashan University of Medical Sciences (Persian)]. Feyz. 2020; 24(1):109-21. [Link]

- Lund S, Yan M, D'Angelo J, Wang T, Hallbeck MS, Heller S, Zielinski M. NASA-TLX assessment of workload in resident physicians and faculty surgeons covering trauma, surgical intensive care unit, and emergency general surgery services. American Journal of Surgery. 2021; 222(6):1158-62. [DOI:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2021.10.020] [PMID]

- Sarsangi V, Saberi HR, Hannani M, Honarjoo F, Salim Abadi M, Goroohi M, et al. [Mental workload and its affected factors among nurses in Kashan province during 2014 (Persian)]. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences. 2015; 14(1):25-36. [Link]

- Young G, Zavelina L, Hooper V. Assessment of workload using NASA Task Load Index in perianesthesia nursing. Journal of Perianesthesia Nursing. 2008; 23(2):102-10. [DOI:10.1016/j.jopan.2008.01.008] [PMID]

- Walters C, Webb PJ. Maximizing efficiency and reducing robotic surgery costs using the NASA task load index. AORN Journal. 2017; 106(4):283-294. [DOI:10.1016/j.aorn.2017.08.004] [PMID]

- Kakaraparthi VN, Vishwanathan K, Gadhavi B, Reddy RS, Tedla JS, Samuel PS, et al. Application of the rapid upper limb assessment tool to assess the level of ergonomic risk among health care professionals: A systematic review. Work. 2022; 71(3):551-64. [DOI:10.3233/WOR-210239] [PMID]

- Von Janczewski N, Kraus J, Engeln A, Baumann M. A subjective one-item measure based on nasa-tlx to assess cognitive workload in driver-vehicle interaction. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology And Behaviour. 2022; 86:210-25. [DOI:10.1016/j.trf.2022.02.012]

- Buckle P. Ergonomics and musculoskeletal disorders: Overview. Occupational Medicine. 2005; 55(3):164-7. [DOI:10.1093/occmed/kqi081] [PMID]

- da Costa BR, Vieira ER. Risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of recent longitudinal studies. American Journal of Industrial Medicine. 2010; 53(3):285-323. [DOI:10.1002/ajim.20750] [PMID]

- ZakerJafari HR, YektaKooshali MH. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Iranian dentists: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Safety and Health at Work. 2018; 9(1):1-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.shaw.2017.06.006] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Valachi B, Valachi K. Preventing musculoskeletal disorders in clinical dentistry: strategies to address the mechanisms leading to musculoskeletal disorders. Journal of the American Dental Association. 2003; 134(12):1604-12. [DOI:10.14219/jada.archive.2003.0106] [PMID]

- Heidarimoghadam R, Mortezapour A, Najafighobadi K, Saeednia H, Mosaferchi S. [Studying the relationship between surgeons’ mental workload and their productivity: Validating the “surgeon-tlx” tool in Iranian surgeons (Persian)]. Journal of Ergonomics. 2022; 10(3):172-80. [Link]

- Braarud Pø. Investigating the validity of subjective workload rating (Nasa Tlx) and subjective situation awareness rating (Sart) for cognitively complex human-machine work. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2021; 86:103233. [DOI:10.1016/j.ergon.2021.103233]

- Hart SG, Staveland LE. Development of Nasa-Tlx (task load index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. Advances in Psychology. 1988; 52:139-83. [DOI:10.1016/S0166-4115(08)62386-9]

- Nino V, Claudio D, Monfort SM. Evaluating the effect of perceived mental workload on work body postures. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2023; 93:103399. [DOI:10.1016/j.ergon.2022.103399]

- Didomenico A, Nussbaum MA. Effects of different physical workload parameters on mental workload and performance. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2011; 41(3):255-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.ergon.2011.01.008]

- Mahmoudifar Y, Seyedamini B. Investigation on the relationship between mental workload and musculoskeletal disorders among nursing staff. International Archives of Health Sciences. 2018; 5(1):16-20. [Link]

- Grytten J, Skau I. Improvements in dental health and dentists' workload in Norway, 1992 to 2015. International Dental Journal. 2022; 72(3):399-406. [DOI:10.1016/j.identj.2021.07.004] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mulimani P, Hoe VC, Hayes MJ, Idiculla JJ, Abas AB, Karanth L. Ergonomic interventions for preventing musculoskeletal disorders in dental care practitioners. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018; 10(10):CD011261. [DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD011261.pub2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Shams-Hosseini NS, Vahdati T, Mohammadzadeh Z, Yeganeh A, Davoodi S. Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders among dentists in Iran: A systematic review. Materia Socio-Medicad. 2017; 29(4):257-62. [DOI:10.5455/msm.2017.29.257-262] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hosseini A, Choobineh A, Razeghi M, Pakshir HR, Ghaem H, Vojud M. Ergonomic assessment of exposure to musculoskeletal disorders risk factors among dentists of Shiraz, Iran. Journal of Dentistry. 2019; 20(1):53-60. [DOI:10.30476/dentjods.2019.44564]

- Eyvazlou M, Asghari A, Mokarami H, Bagheri Hosseinabadi M, Derakhshan Jazari M, Gharibi V. Musculoskeletal disorders and selecting an appropriate tool for ergonomic risk assessment in the dental profession. Work. 2021; 68(4):1239-48. [DOI:10.3233/WOR-213453] [PMID]

- Koochak Dezfouli M, Bagheri B, Yazdani Charati J, Zamanzadeh M. [Prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders and related risk factors among general dentists in Sari in 2019(Persian)]. Journal of Mashhad Dental School. 2021; 45(4):395-404. [DOI:10.22038/JMDS.2021.53740.1975]

- Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, Vinterberg H, Biering-Sørensen F, Andersson G, Jørgensen K. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon. 1987 Sep;18(3):233-7. [DOI:10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-X] [PMID]

- Choobineh A, Lahmi M, Shahnavaz H, Jazani RK, Hosseini M. Musculoskeletal symptoms as related to ergonomic factors in Iranian hand-woven carpet industry and general guidelines for workstation design. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics. 2004; 10(2):157-68. [DOI:10.1080/10803548.2004.11076604] [PMID]

- Mohammadi M, Mazloumi A, Nasl Seraji J, Zeraati H. [Designing questionnaire of assessing mental workload and determine its validity and reliability among icus nurses in one of the Tums’s hospitals (Persian)]. Journal of School of Public Health and Institute of Public Health Research. 2013; 11(2):87-96. [Link]

- Besharati A, Daneshmandi H, Zareh K, Fakherpour A, Zoaktafi M. Work-related musculoskeletal problems and associated factors among office workers. International Journal of Occupational Safety and Ergonomics. 2020; 26(3):632-8. [DOI:10.1080/10803548.2018.1501238] [PMID]

- Gholami T, Maleki Z, Ramezani M, Khazraee T. Application of ergonomic approach in assessing musculoskeletal disorders risk factors among administrative employees of medical university. International Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain Prevention. 2018; 3(2):63-7. [Link]

- Pirmoradi Z, Golmohammadi R, Faradmal J, Motamedzade M. [Artificial lighting and its relation with body posture in office workplaces (Persian)]. Iran Journal of Ergonomics. 2018; 5(4):9-16. [DOI:10.30699/jergon.5.4.9]

- Collins JD, O’sullivan LW. Musculoskeletal disorder prevalence and psychosocial risk exposures by age and gender in a cohort of office based employees in two academic institutions. International Journal of Industrial Ergonomics. 2015; 46:85-97. [DOI:10.1016/j.ergon.2014.12.013]

- Jonker D, Rolander B, Balogh I. Relation between perceived and measured workload obtained by long-term inclinometry among dentists. Applied Ergonomics. 2009; 40(3):309-15. [DOI:10.1016/j.apergo.2008.12.002] [PMID]

- Habibi E, Hasanzadeh A, Mahdavi Rad M, Taheri MR. [Relationship mental workload with musculoskeletal disorders among Alzahra hospital nurses by NASA-TLX index and CMDQ (Persian)]. Journal of Health System Research. 2015; 10(4):775-85. [Link]

- Arghami S, Kamali K, Radanfar F. [Task performance induced work load in nursing (Persian)]. Journal of Occupational Hygiene Engineering. 2015; 2(3):45-54. [Link]

- Mazur LM, Mosaly PR, Jackson M, Chang SX, Burkhardt KD, Adams RD, et al. Quantitative assessment of workload and stressors in clinical radiation oncology. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. 2012; 83(5):e571-6. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.063] [PMID]

- Zakerian SA, Abbasinia M, Mohammadian F, Fathi A, Rahmani A, Ahmadnezhad I, et al. [The relationship between workload and quality of life among hospital staffs (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of Ergonomics. 2013; 1(1):43-56. [Link]

- Fottler MD, Widra LS. Intention of inactive registered nurses to return to nursing. Medical Care Research and Review. 1995; 52(4):492-516. [DOI:10.1177/107755879505200404] [PMID]

- Malekpour F, Mohammadian Y, Mohamadpour Y, Fazli B, Hassanloei B. [Assessmen of relationship between quality of life and mental workload among nurses of Urmia Medical Science University Hospitals (Persian)]. Nursing and Midwifery Journal. 2014; 12(6):499-505. [Link]

- Shkembi A, Smith LM, Le AB, Neitzel RL. Noise exposure and mental workload: Evaluating the role of multiple noise exposure metrics among surface miners in the US Midwest. Applied Ergonomics. 2022; 103:103772. [DOI:10.1016/j.apergo.2022.103772] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Surgery

Received: 16/04/2023 | Accepted: 18/10/2023 | Published: 1/07/2024

Received: 16/04/2023 | Accepted: 18/10/2023 | Published: 1/07/2024

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |