Volume 24, Issue 4 (Winter 2024)

jrehab 2024, 24(4): 516-547 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rohani Ravari M H, Darouie A, Ebadi A. Explaining the Telepractice Process of Stuttering in Preschool Children: A Grounded Theory Study. jrehab 2024; 24 (4) :516-547

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3259-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3259-en.html

1- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Koodakyar Alley, Daneshjoo Blvd., Velenjak

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Koodakyar Alley, Daneshjoo Blvd., Velenjak, Tehran, Iran

3- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Faculty of Nursing, Lifestyle Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,ebadi1347@yahoo.com

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Koodakyar Alley, Daneshjoo Blvd., Velenjak, Tehran, Iran

3- Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Faculty of Nursing, Lifestyle Institute, Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 2446 kb]

(1167 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (6877 Views)

Full-Text: (1712 Views)

Introduction

Stuttering is a type of disfluency in speech that may occur during the developmental period or in adulthood due to trauma. Stuttering exhibits symptoms such as block, prolongation, or repetition [1، 2]. Based on age, stuttering can be divided into three types: Preschool children, school-age children, and adults [1، 3].

Various texts on stuttering have emphasized that early intervention increases the probability of recovery and accelerates spontaneous recovery. Accordingly, providing treatment to preschool children becomes particularly important [4، 5]. To conduct the programs for stuttering therapy, the person with stuttering must go to the medical centers several times a week and receive the desired treatment. These regular visits may be impossible sometimes due to various reasons such as lack of therapist, long distance between home and clinic, and physical condition of the patient [5، 6]. Another case that decreased face-to-face visits to speech therapy clinics over the last three years is the COVID-19 pandemic, depriving people of speech and language therapies [7].

Information and communication technology enables therapists to provide their treatments remotely to people needing speech therapy services. Providing services using information and communication technology eliminates travel time to clinics or clients’ homes for individuals and therapists. In addition to allowing people to benefit from rehabilitation services regardless of geographical distance, the therapist can provide services to more people [8]. So far, several studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficiency of stuttering telepractice, and these studies have indicated the positive effect of this method of providing treatment on the severity of stuttering [9-11].

Reviewing studies on stuttering telepractice has shown problems with this treatment method. These problems include therapist training, insurance and payment issues, and country policy issues [12، 13]. One of these studies was a review on the topic of telepractice conducted by Theodores (2011). This study examined the benefits, scientific evidence, challenges, and future of telepractice. The challenges in the study relate to professional issues, reimbursement, clinical outcomes and usefulness, and available technology. At the end of this study, the authors suggested conducting more studies on the efficacy of this method of treatment [14]. A more accurate and deeper identification of the problems in this treatment method is the first step to improving the quality of telepractice services.

The study of Skeat and Perry (2008) recommended using the grounded theory method in studies related to speech and language, and the resulting theories can be used as a basis for other studies [15]. The grounded theory method is used when a phenomenon is not well described or when there are few theories to describe it. In the grounded theory, the main concerns and problems of the participants are identified, and a descriptive framework is explained for it. In this theory, the concepts that make up the theory are extracted from the data collected during the study and are not pre-selected as in some qualitative studies. In this type of study, data collection and analysis are interdependent, and data analysis is done by collecting the data continuously. These factors distinguish grounded theory from other qualitative research methods [16].

The purpose of this qualitative study is to investigate the process of telepractice in preschool children’s stuttering using the grounded theory method. By accurately identifying this process, a step can be taken to increase the quality of telepractice for preschool children stuttering.

Materials and Methods

The present qualitative research is a grounded theory study. A qualitative study helps the researcher gain in-depth and detailed insight into a particular subject. Qualitative studies help collect and describe phenomena in existing contexts using disciplined methods [17]. This method can help understand a phenomenon better and more profoundly. In grounded theory, participants’ main concerns and problems are identified through a process, and a descriptive framework is explained [15].

This study was conducted in Iran. To maximize diversification, participants from Tehran, Isfahan, Khorasan Razavi, South Khorasan, Yazd, Shiraz, and Hamedan provinces were selected using purposive sampling. This study was conducted between November 2020 and February 2022.

Study participants

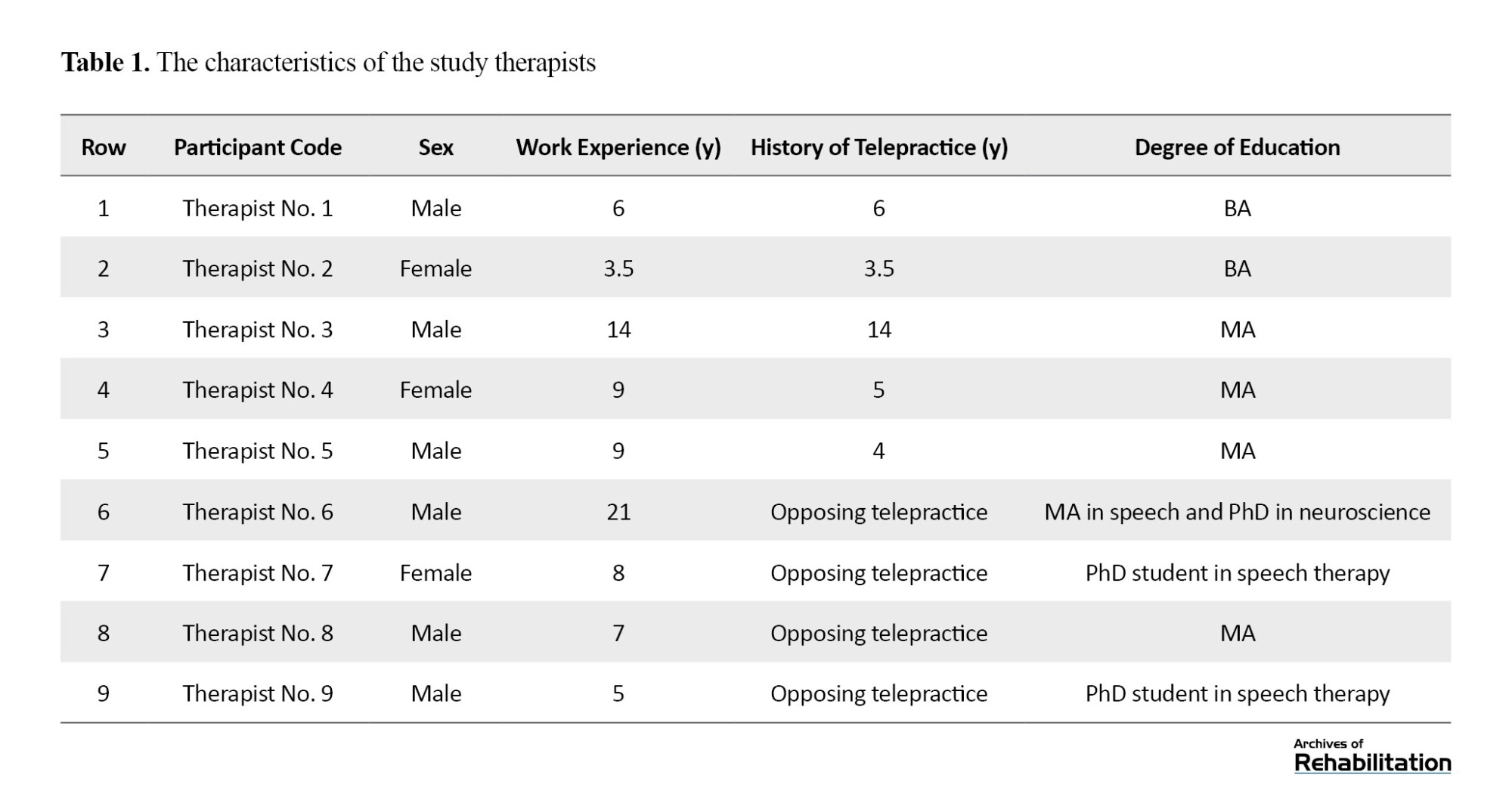

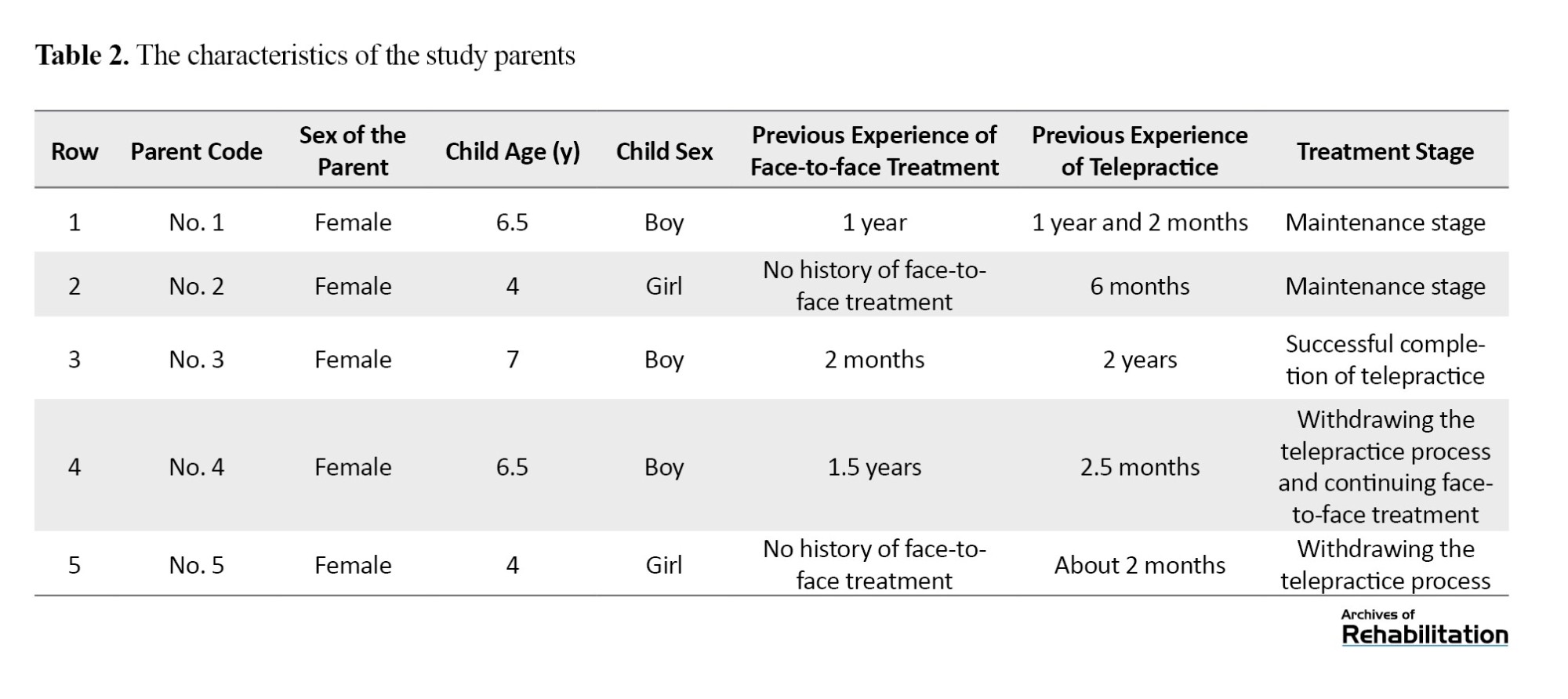

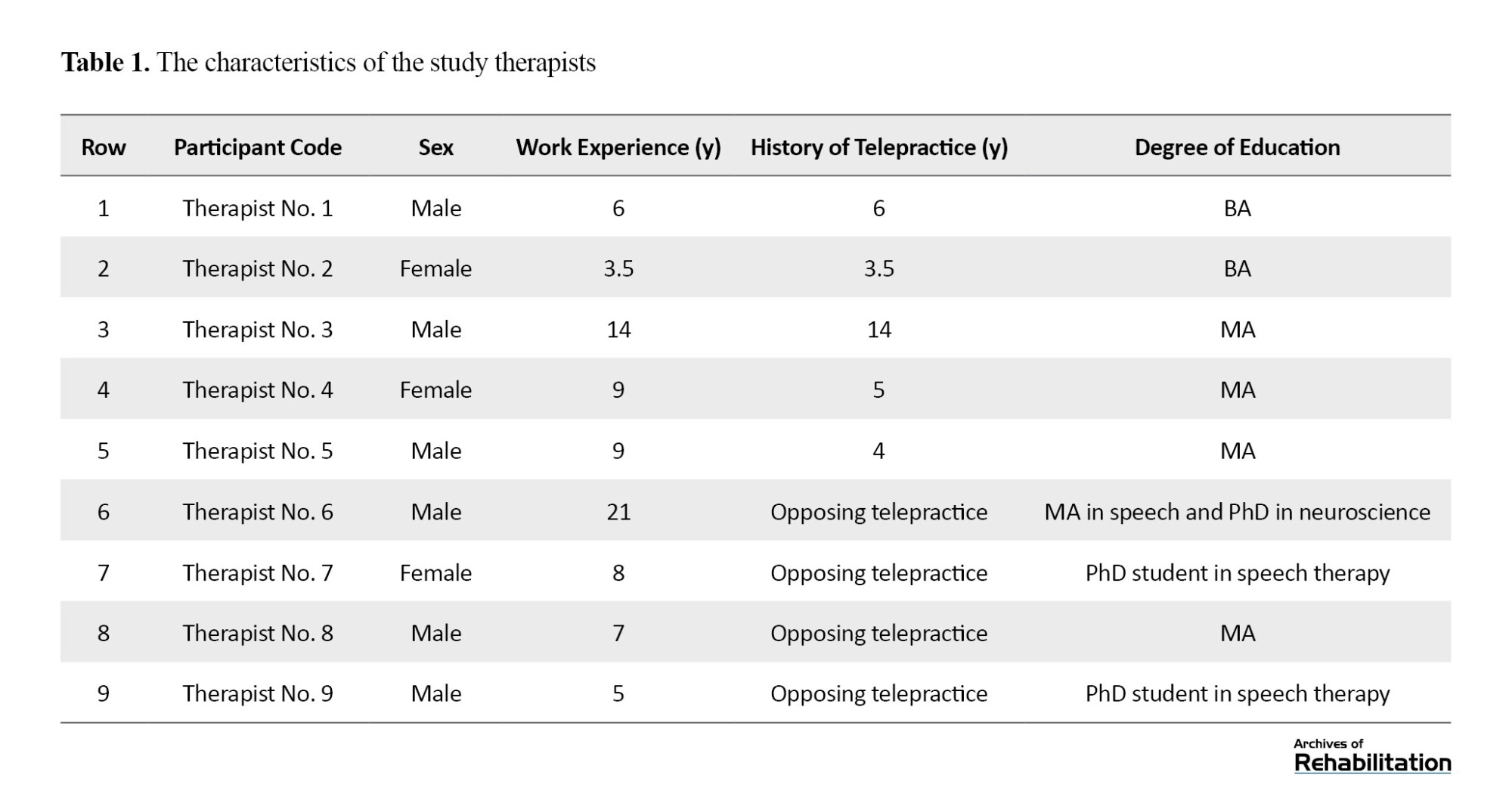

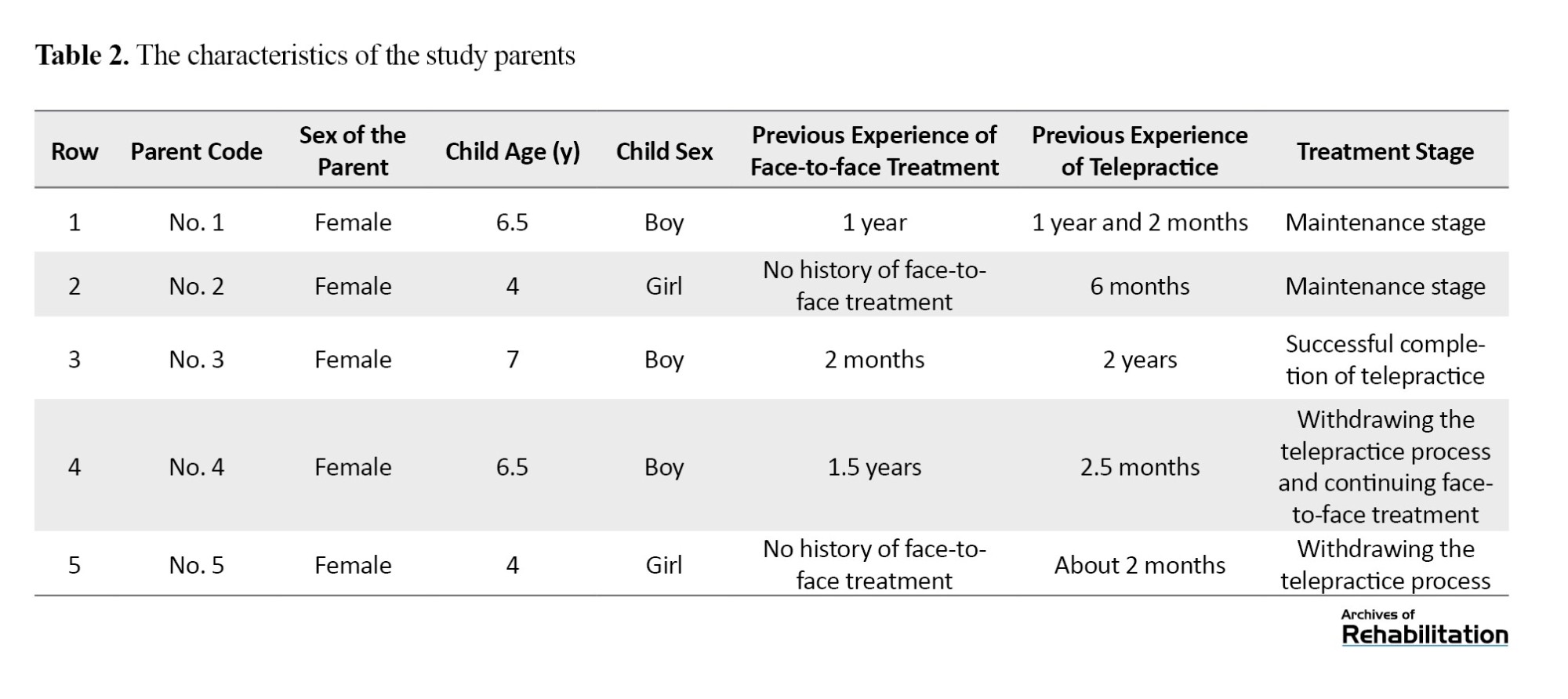

A total of 14 participants were included in this study, comprising 5 therapists with telepractice experience, 4 therapists who were opposed to telepractice, 3 parents with successful treatment experience, and 2 parents with telepractice withdrawal experience (Tables 1 and 2).

After each interview, it was analyzed. By theoretical sampling, more interviews were conducted with parents who had successful or unsuccessful treatment and telepractice therapists. The sampling process continued until reaching data saturation. Saturation is a point in which the analysis process where a new concept is not extracted after further analysis of the interviews [18].

Interview procedure

In this study, unstructured interviews were used to collect data because free interviews can provide the most data to the researcher. This type of interview also provides the possibility of theoretical sampling for the researcher. The interview started with an open-ended question like “please explain your experience in telepractice for stuttering in preschool children”. At each point of the interview that was ambiguous for the interviewer or needed further explanation, the interviewer asked questions from the participant to clarify the issue. Interview sessions were conducted to obtain consent from the participants in voice calls using WhatsApp. Interviews took 35 to 66 minutes, with an average of 49 minutes.

It should be noted that the first author of this study conducted the interviews. The interviewer is a PhD student in speech therapy with a history of conducting research in the field of telepractice.

Data analysis

The obtained data were analyzed using Strauss and Corbin method version 2015 (Corbin, 2015#400). The steps of this method include open coding, examining concepts to find their dimensions, analysis for context, process, and integration. MAXQDA software, version 2020 was used for data analyses. In this study, the criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba were used to increase the reliability of the data: Credibility, transferability, confirmability, and consistency [19، 20].

Credibility in qualitative studies increases the probability of obtaining valid findings. This study tried to increase the credibility and accuracy of the findings with the researcher’s long-term involvement (about 2 years). Also, some data were given to other research team members, who were asked to analyze the data and extract its concepts. Another method used to increase the credibility of the data was to review the results of the analyses by the participants.

Transferability or appropriateness is equivalent to generalizability in quantitative studies, which shows how much research findings can be applied in similar situations. To increase transferability in this study, we tried to provide a detailed description of the participants so that the readers of this study report can get to know the characteristics of the participants.

Confirmability shows how much the results are based on the data and not influenced by the researcher’s bias. To increase confirmability in this study, notes were taken, and reports were written during the analysis so that the readers of the reports could achieve similar results by following them.

Consistency of qualitative studies is equivalent to reliability in quantitative studies and refers to the stability of the data pattern at another time. To increase consistency in studies, there should be auditability, which means that another researcher can follow up on the entire study process and decisions made in the study. In this study, to achieve consistency, we tried to record and report all the steps and the whole study process accurately so that the readers could perform the audit using these reports.

Results

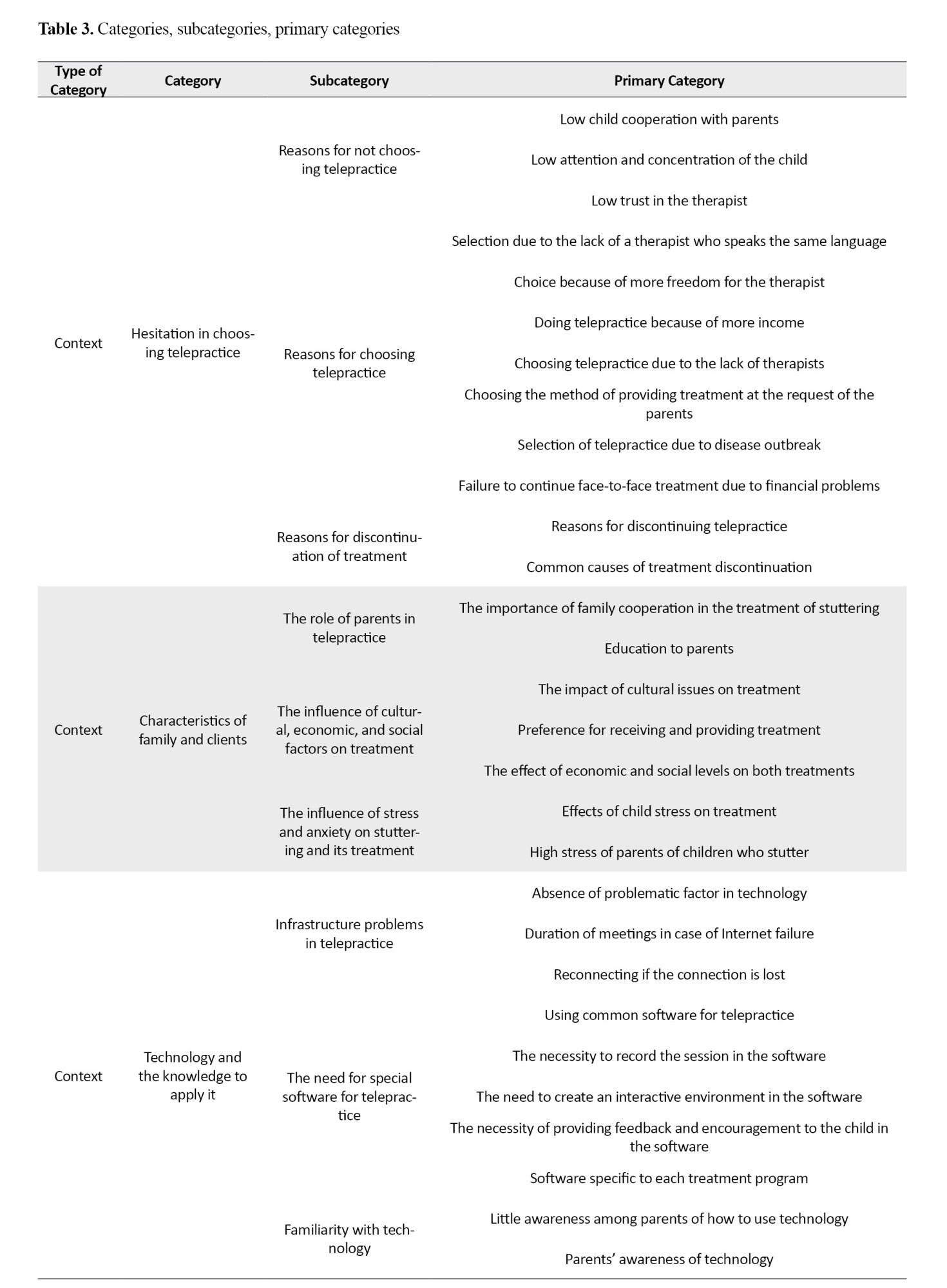

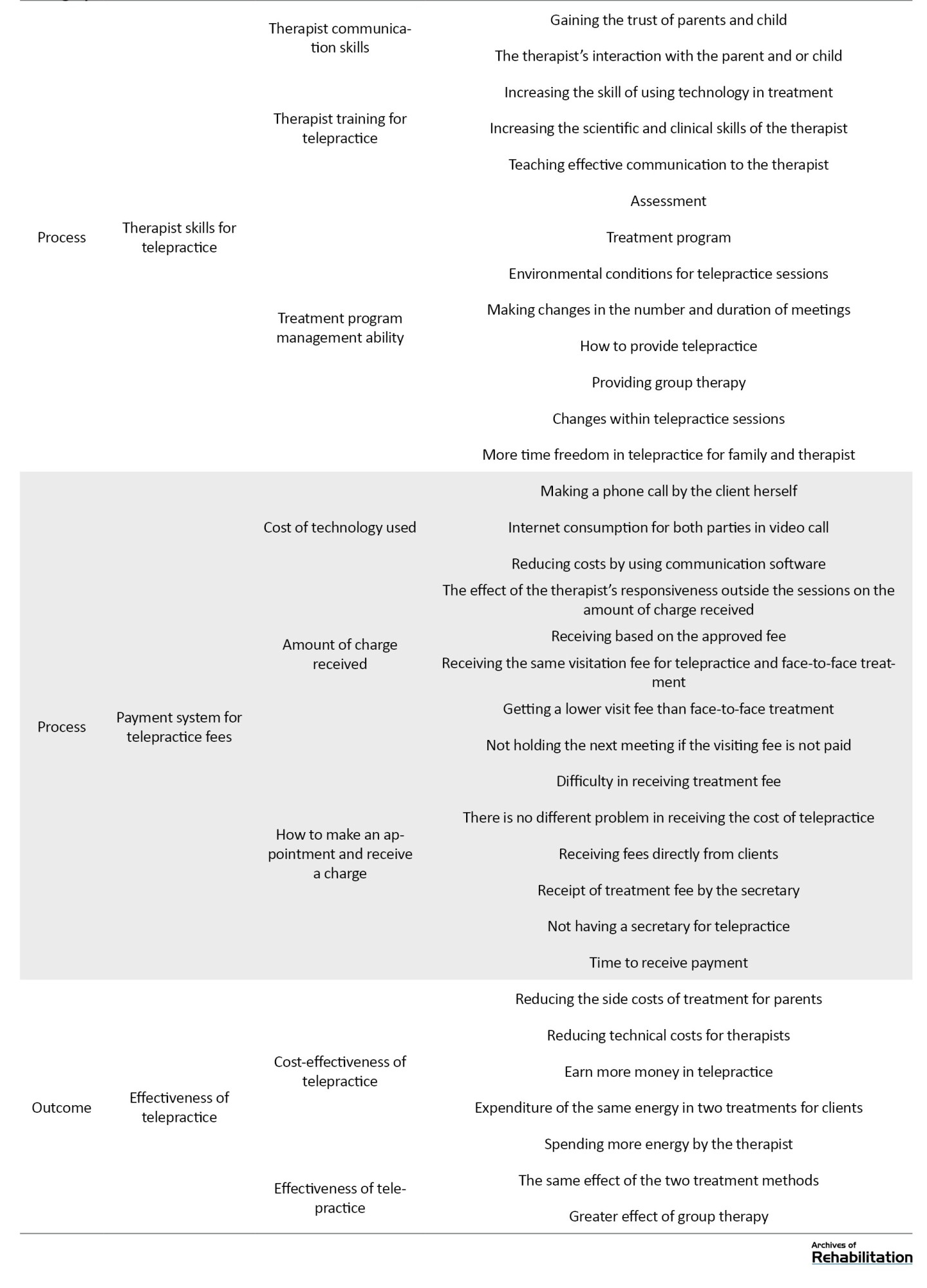

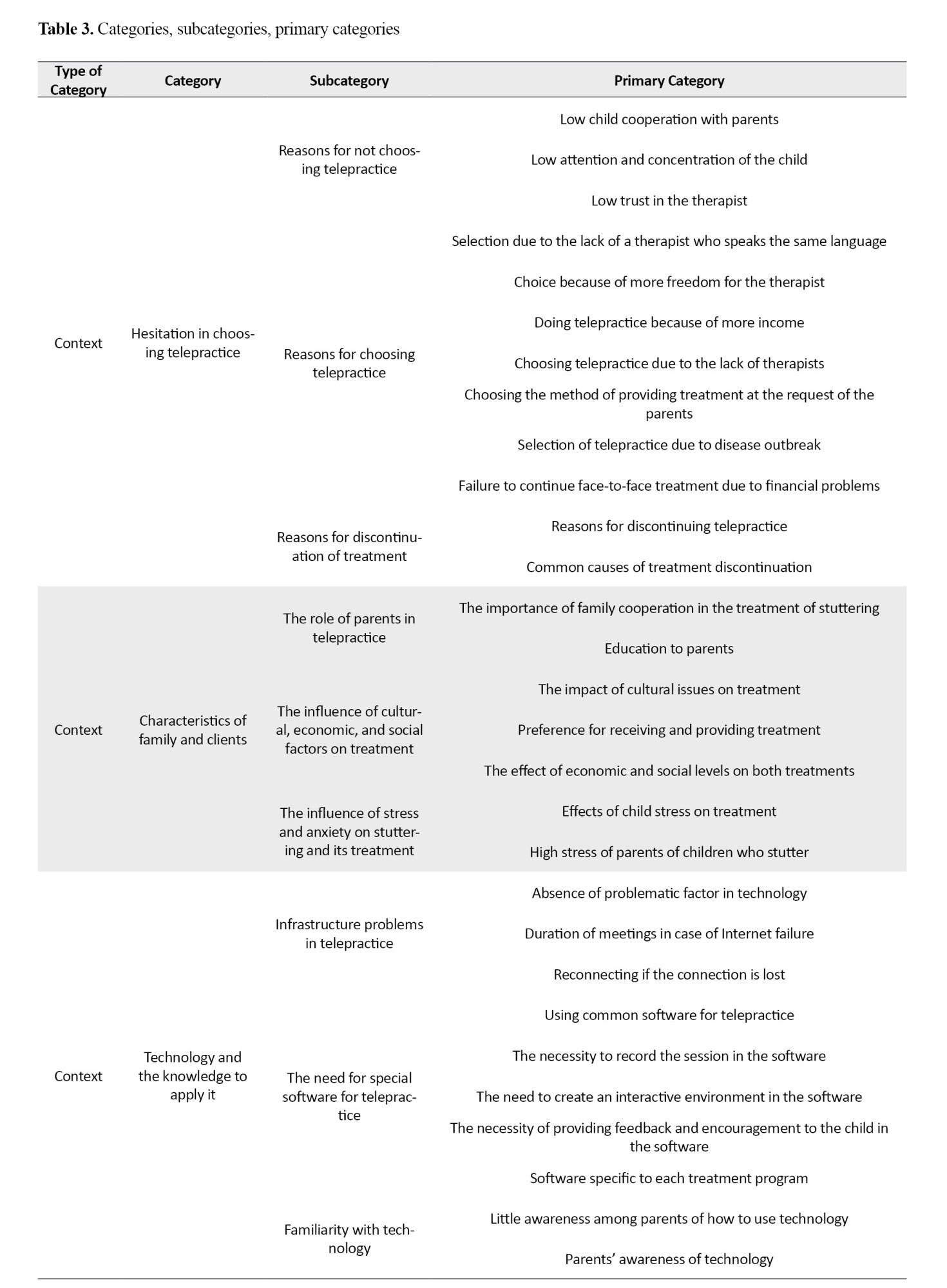

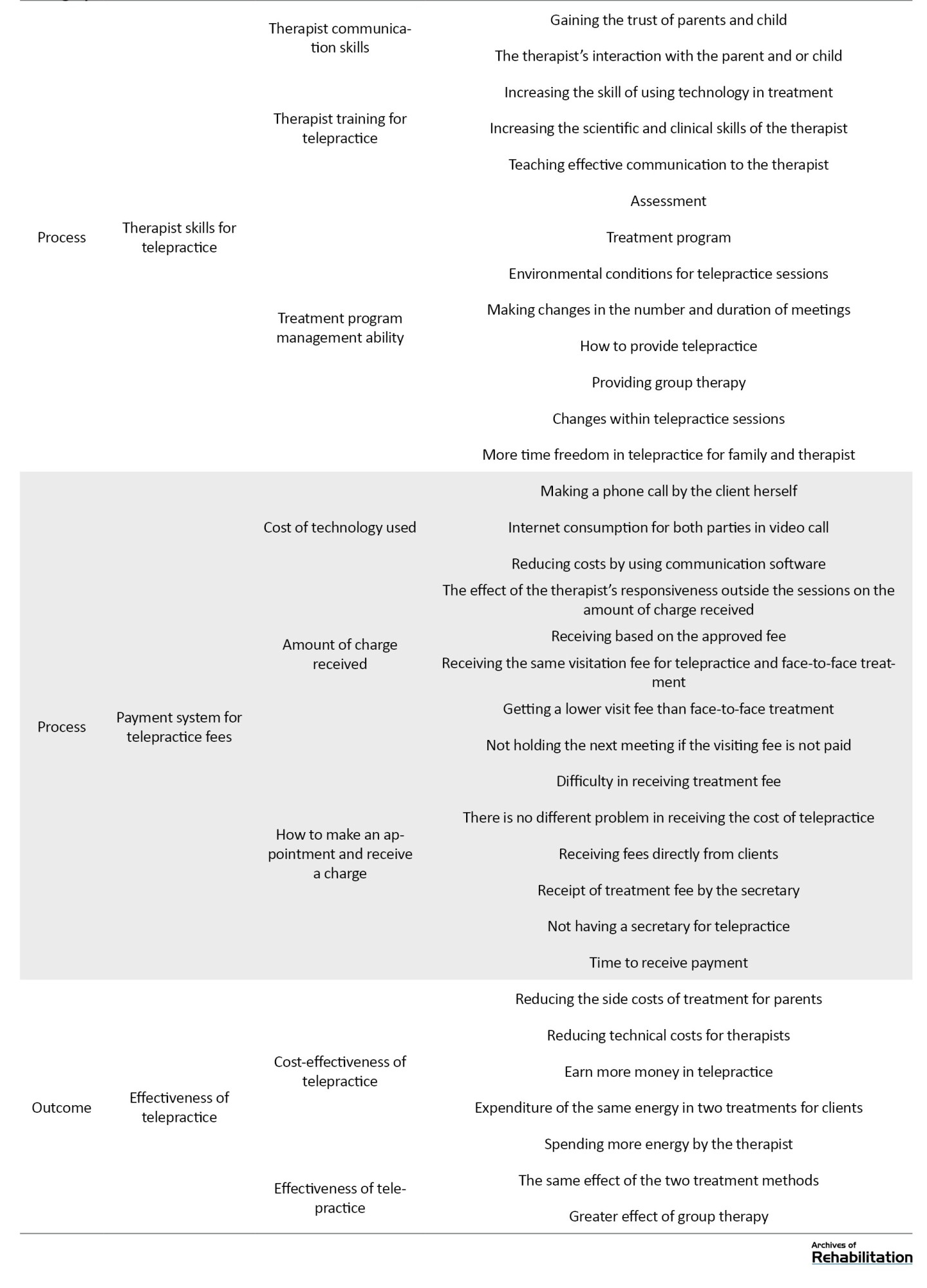

During this study, a total of 1046 primary codes were extracted. These codes were combined by continuous and constant comparison based on their similarities and relationships, and primary categories, subcategories, and main categories were finally developed. In total, 6 main categories, 17 subcategories, and 63 primary categories were extracted in this study (Table 3).

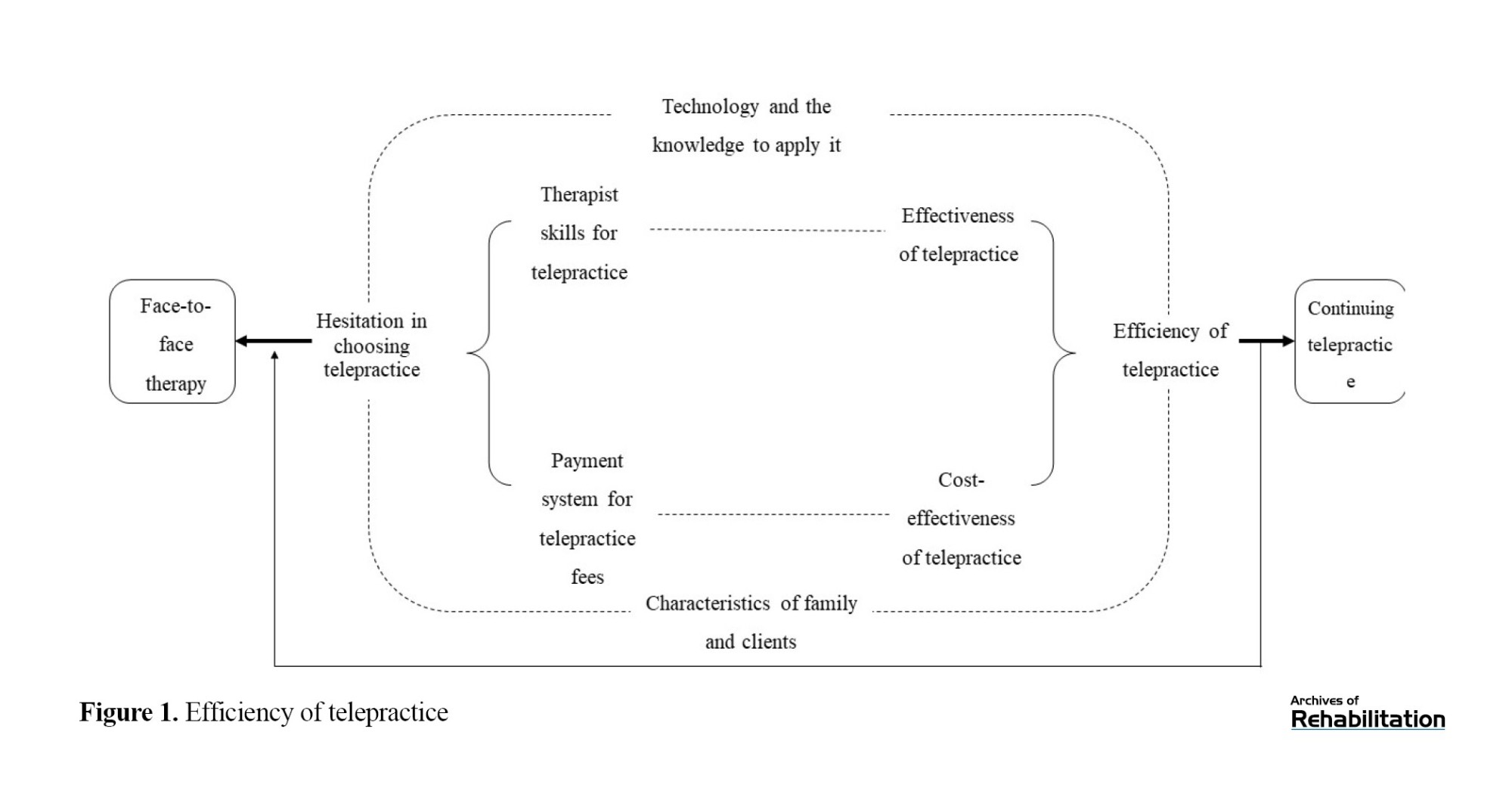

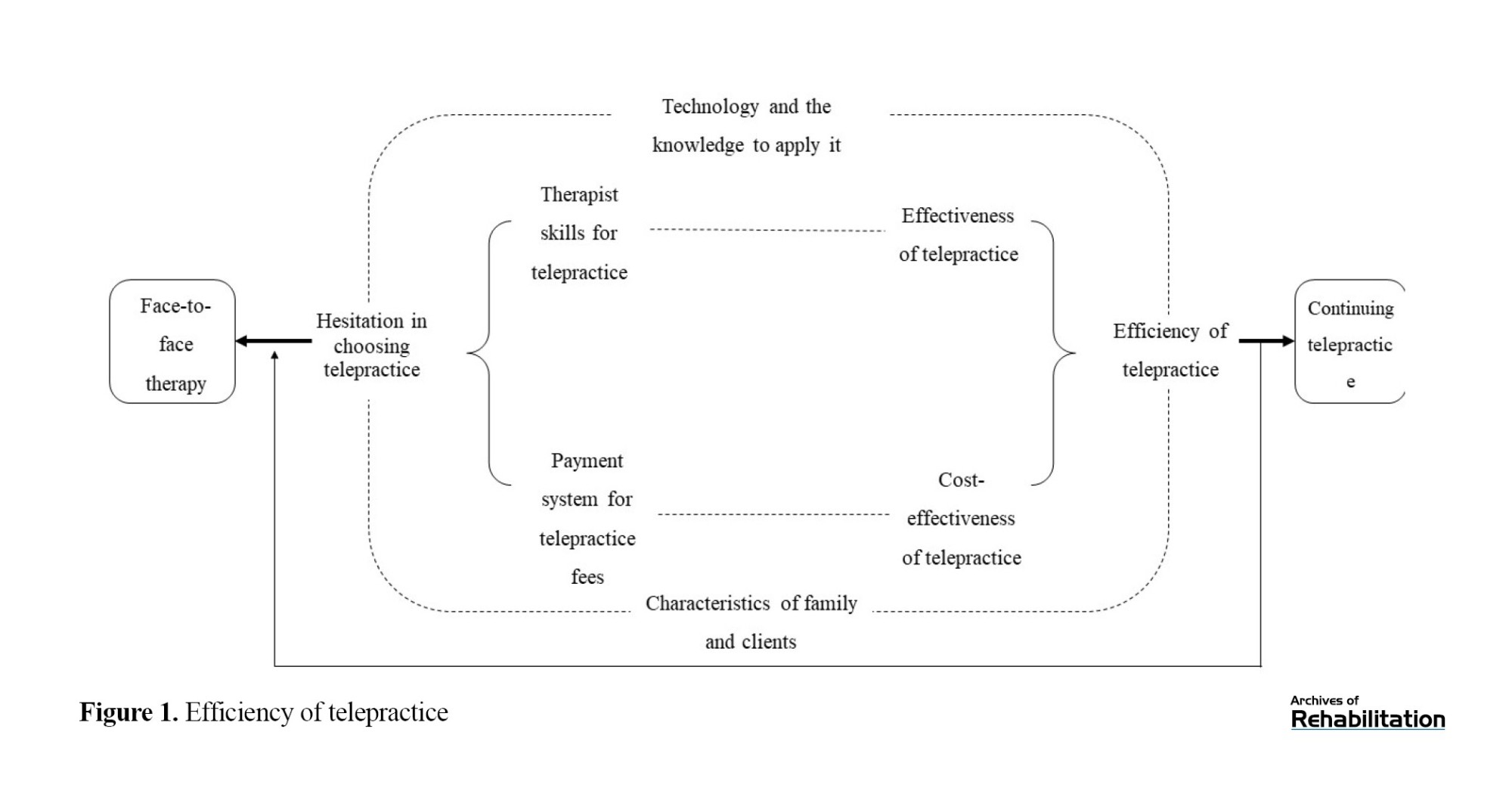

The main categories include “hesitation in choosing telepractice”, “family and client characteristics”, “technology and knowledge to apply it”, “therapist skills for telepractice”, “payment system for telepractice fees”, and “efficiency of telepractice”. The conceptual model shown in Figure 1 was developed using the extracted concepts. According to the analysis, “efficiency of telepractice” was identified as the central concept. The results of the study are described below. It should be noted that quotes are given as examples among the explanations related to categories.

Hesitation in choosing telepractice

Several families have chosen telepractice due to some problems. Many other families hesitated to choose this method due to facing some issues, abandoned it, and turned to face-to-face treatment. The category of “hesitation in choosing telepractice” has three subcategories: “reasons for not choosing telepractice”, “reasons for choosing telepractice”, and “reasons for discontinuation of treatment”, which are explained below in relation to these subcategories.

The lack of therapists, the long distance between the clinic and the client’s home, and the COVID-19 pandemic over the last three years are the reasons parents have chosen telepractice.

“Commuting was very important for me; it is not okay in this crowd and this situation, well, if there was a possibility for a face-to-face visit now, well, definitely, I could not go because now in this outbreak of, it is not really good to be in a clinic.” Said parent No. 5, who withdrew from telepractice.

One of the reasons therapists choose telepractice is to expand the geographical area they cover and increase their income.

“My situation is such that I cannot work in a crowded city to earn more income and have time in the field of stuttering the way I want to and get both economic and scientific results.” Said therapist No. 2 with 3.5 years of telepractice experience.

Trusting the therapist is one factor affecting parents’ choice of telepractice. If the parent does not trust the therapist, even the therapist is reluctant to do the treatment remotely.

Therapist No. 3, with 14 years of telepractice experience, said, “I personally do not telepractice with clients who do not trust me. Okay? That is, if they are not introduced before, I personally will not work with them remotely.”

Parents’ daily work may cause them to stop telepractice and choose face-to-face therapies to reduce their responsibilities and have their child’s therapist take care of the children.

“In online treatment, since I have to be completely at my daughter’s demand and I really did not have the opportunity to let this happen, I said, let’s see what decision we have to make after this summer.” Said parent No. 5, who withdrew from telepractice.

Some parents prefer to receive treatment in person because telepractice reduces the child’s social interactions, and the child receives treatment at home without contact with other people.

Parent No. 4, who refused telepractice, said, “The child becomes more social in face-to-face communication. At least, he learns how to behave in the community with someone other than his family and how to treat and talk to them.”

Characteristics of family and clients

In general, the family plays an essential role in treating preschool children’s stuttering. In telepractice, the therapist interacts more with the parent and tries to perform the therapy by educating the parents. Therefore, family characteristics become more important for telepractice. It seems that the amount of parental cooperation in the treatment process depends on the characteristics of each family. Also, the stress and anxiety of the family, which is seen in the families of children with stuttering, affects this process. This category is composed of the subcategories “the role of parents in telepractice”, “the influence of cultural, economic, and social factors on treatment”, and “the influence of stress and anxiety on stuttering and its treatment”, which are further explained in relation to these subcategories.

The results indicate that in telepractice, the therapist interacts more with the parents than the child. Accordingly, the burden of parents’ responsibility in telepractice increases. Therefore, parents should have a high level of cooperation with the therapist in this treatment.

“In the way we had, the Lidcombe program was much more responsible because I did everything myself.” Said parent No. 3, who had successful treatment.

Also, the participation and cooperation of other family members in the treatment is very important. In addition to reducing the burden on the parent in charge of treatment, it also helps to adapt the child’s living environment and achieve a better result.

Parent No. 5, who refused telepractice, said, “It can be said that practice is a way in which all the members who live together in the same house or even the one who enters the house as a guest, all have to come to something in common, understand the situation and talk in almost the same way that the speech therapist said.”

The parent’s level of education can affect the quality of education and make the parent learn and apply the education provided by the therapist better.

Parent No. 3, who successfully completed telepractice, said, “I think at some points, the mother’s education can also affect your understanding of what your therapist means. I think this is important.”

The conditions of the house, such as the number of people and the presence of the child’s siblings, can make it difficult for the parent to prepare for the treatment environment.

“Sometimes when I came to talk, I just had to tell my kids “Don’t.” I was pointing down with my hand. When something was falling, I would catch it. It is distracting. I was looking at the clock like it’s three-thirty, and it ends in ten minutes instead of enjoying sessions.” said parent No. 5, who rejected telepractice.

Using telepractice is not fully accepted among clients, and clients view face-to-face treatment as the gold standard and prefer to receive treatment as a combination of face-to-face and telepractice.

“I always thought that face-to-face therapy might be another way; maybe it would help a person better, and the child would have a better relationship with the therapist. I mean, if our communication were in person, or at least once in a while, every two months, once every three months, it would help. Then we would go there and see other children; we would see other mothers.” said parent No. 2, who was at the maintenance stage.

Family characteristics such as education level, belief in telepractice, and economic and social level affect parents’ cooperation.

Therapist No. 5, with 4 years of telepractice, said, “Their level of education definitely affects their cooperation. Their social economy is effective in this case, and I mean their social class. Even their economics are effective in this case.”

Presence in the clinic, encountering strangers, and the therapist’s presence in face-to-face therapies may increase the child’s stress. These are less common in telepractice because the treatment is provided in a familiar home environment.

Parent No. 4, who rejected telepractice, said, “However, he does not feel that the person next to him is more tormented. Like an online classroom, it is very different from a face-to-face classroom. The child has more control, sits, has confidence, sits next to me, and talks, but in face-to-face therapy, which is not the case, the child goes into a non-family room, for example, talking to strangers, which is very different.”

In general, parents of children with stuttering experience high-stress levels. Parents’ awareness of the nature of stuttering, its treatments, and the future of stuttering can help reduce their stress.

Therapist No. 2, with 3.5 years of telepractice experience, said, “In the issue of stuttering, children’s parents have a lot of stress, are very worried, and are really confused. And if there is no one with them along the way, stress exaggerates the stuttering in the child.”

Technology and knowledge to apply it

It is necessary to have a suitable platform for remote communication. In addition to the existence of a suitable platform, the level of knowledge of the people who should participate in this communication is also essential in using the existing technology. The category of “technology and knowledge to apply it” is composed of the subcategories of “infrastructure problems in telepractice”, “the need for a special software for telepractice”, and “familiarity with technology”, which are explained in the following section in relation to these subcategories.

Problems such as slow Internet and disconnection may occur during telepractice sessions. Based on the results, these problems do not interfere with the meetings, and if the connection is lost, it is re-established, and the meeting starts again.

“Well, when the call is disconnected, we make the call again and continue. There is no problem in the middle. I do not show a negative reaction, nor does the parent because we are both familiar with the situation.” said therapist No. 2, with 3.5 years of telepractice experience.

To perform telepractice, therapists use common and available applications such as WhatsApp and Skype. WhatsApp is more common because it is user-friendly.

Therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience, said, “Now we have a lot of software that can make video and voice calls. For example, we can use Skype. There is WhatsApp for video calls, Telegram, and Imo; it can be done whatever it is. The quality is almost the same. I myself did my treatment with WhatsApp; the contacts we had were mostly with WhatsApp.”

In some treatment programs, such as Lidcombe and FRP, it is crucial to provide feedback to clients. Having software that allows the child to provide feedback can be very helpful.

Therapist No. 2, with 3.5 years of telepractice experience, said, “Sometimes we have a meeting with the child, and this software only supports video calling. I like to show the child a picture, and at the same time, I see that picture, and the child sees that picture, I would like to send him a sticker because I want to give him feedback. Skype somewhat works for us, which is why I use Skype.”

Therapist skills for telepractice

For the therapist to effectively provide telepractice, he/she must have skills to solve specific problems and conditions encountered during the treatment. Therapist skills for telepractice consist of subcategories, including “therapist communication skills”, “therapist training for telepractice”, and “treatment program management ability”. Below are explanations related to the subcategories.

In telepractice, trust between the therapist and the client may develop later or cause problems. Responsiveness and a high scientific level of therapists significantly impact trust.

Parent No. 1, at the maintenance stage, said, “Look, all this trust in the therapist was formed for me when I saw the therapist’s knowledge.”

Establishing communication between parents of children with stuttering can significantly help increase client trust in the therapist, transfer experiences, and increase parents’ awareness. The therapist must also have the skills to communicate with parents and how to deal with parents.

Parent No. 2 at the telepractice maintenance stage said, “Another thing that helped me gain more trust was that I read other mothers’ comments, I was in contact with them, we had an information exchange, as the famous saying goes, and I saw that there are mothers who trust them like this, then I can trust them, and this trust is growing every day.”

The problem of trusting the therapist is not seen in parents to whom a trusted person has referred.

“When a colleague refers them, their trust will increase. In this case, I have never experienced this problem. Because the referrals I experienced were all from colleagues”, said therapist No. 3, with 14 years of telepractice experience.

The therapist’s reputation as a specialist and experienced therapist in the field of stuttering significantly impacts the therapist’s trust.

Therapist No. 8, who opposed telepractice, said, “I know several cases, therapists who work in stuttering and are much better known. Now, I do not know exactly what their job is, but I know that the more well-known and experienced therapist naturally has more family trust.”

Therapists’ skills for producing and publishing training content on stuttering on social media and therapist activities on social media, in general, can affect trust as some parents search on social media to find a specialist therapist. Therapists’ skills for producing and publishing training content on stuttering on social media and therapist activities on social media, in general, can affect trust as some parents search on social media to find a specialist therapist.

Parent No. 5, who refused telepractice, said, “Before I started the treatment, I followed their page for about 6 months, that is, the posts they sent, the information they posted, and I checked to see if they talk up to date.”

The ability to communicate positively and effectively with both parent and child can constructively affect the treatment process and trust in the therapist.

Therapist No. 7, who opposed telepractice, said, “That effective communication is key either in face-to-face therapy or telepractice. If not, a large part of the treatment is lost.”

The therapist’s experience and communication skills with the child can affect the therapist’s interaction.

Parent No. 4 withdrew from telepractice and said, “The interaction was like face-to-face therapy. For example, if we had 45 minutes, or half an hour if it was half an hour, 20 minutes with the child, 10 minutes with me. Otherwise, if it was 45 minutes, half an hour with the child. They talked to me to tell me tips to follow to treat my child at home so I could work with the child.”

Most therapists believe that to perform a successful telepractice; the therapist must increase his or her scientific and clinical skills through specialized training in this field.

“I think they need to be given a series of training on distance therapy and telepractice, yes, 100%. And I don’t think it’s going to take a student’s time to take a course or two; it can replace another course, which I don’t think is very practical, and yes, it would be great if these courses were given at the university.” said therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience.

Therapists must also have sufficient skills in the use of technology. Therefore, they should receive training in this field to use technology effectively to achieve telepractice goals.

Therapist No. 8, who opposed telepractice, said, “There may be a series of cases or even a series of tutorials on using technology that can help me do this.”

The therapist should be able to evaluate the child remotely and, in addition to the evaluation via video calls, ask the parents to record a sample of the child’s speech in a few-minute video and send it to the therapist for more accurate evaluation.

Therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience, said, “Before beginning the first session, I asked them to take a sample in the form of a film for about four or five minutes, and some of them liked to send the voice, but I said that I should also see the child’s face, they would send the film, and I could have an initial view. But the evaluation was not 100%; the film was a part of our evaluation.”

Generally, therapists do not have any particular problem with the evaluation and usually use the speech sample and the stuttering severity rating for the assessment and believe that using formal evaluations due to being structured can give accurate results to the therapist.

Therapist No. 7, who opposed telepractice, said, “I think we do not have a problem with stuttering evaluation because, in any case, we have a formal evaluation tool for stuttering, which is SSI 4. It is an official tool that is completely defined and predetermined. This means that if we have face-to-face treatment, we will record a video and inform the family about the severity of stuttering in the next session to make our assessment more accurate. And if we want to inform the family in the same session, we will resort to the SR form, which says the severity more qualitatively.”

The therapist must be able to choose the best and most appropriate treatment plan for the child by considering various factors. Therapists also consider the family situation when choosing the type of treatment. For example, suppose the family has good cooperation. In that case, the therapist may use parent-centered therapy, and if the parents are busy and do not actively cooperate, the therapist may use other treatment programs.

Therapist No. 4, with 5 years of telepractice experience, said, “One of the factors is the level of family cooperation and family perception; some families do not have enough cooperation, some families do not have enough understanding of how to implement, these conditions affect whether we want to run the program therapist-centered or parent-centered.”

Therapists believe that protocols for this method should be designed and made widely available to individuals. In addition, the presence of the protocol increases the motivation, interest, and skills of therapists in performing telepractice.

Therapist No. 7, opposed to telepractice, said, “If we have a guide for telepractice for the treatment programs that we now have, for example, for preschoolers, surely therapists’ trust and interest in telepractice will increase.”

In telepractice, the therapist allows the parent to communicate with them between sessions. If they have a question or encounter a problem, ask the therapist questions and resolve their problems.

Parent No. 2, at the treatment maintenance stage, said, “During this time, two weeks or one week, we ask the doctor if we have specific questions or problems. In this regard, we are assured that he is not with us at the time of the meeting, and they do not say that you must visit; you must take your time so that I can answer. No, they really answer, and this is very assuring.”

The therapist must also be able to hold and manage group sessions. Therapists emphasize group therapy and try to have a group session for each client in exchange for a few individual sessions. These group meetings may be synchronous or asynchronous.

“There are two therapists in a group; they offer the children a challenge, and all the children really participate in that challenge willingly. Yes. And that every day the children tell stories to each other, send conferences, tell their daily stories, their memories, everything that has happened.” said parent No. 1, who was at the maintenance stage.

Payment system for telepractice fees

One of the issues that both the therapist and the parent face is the cost of telepractice sessions. In addition to the holding costs, the amount of the received tariff and the method of receiving it should also be taken into consideration in this way. This category consists of the subcategories of “cost of technology used”, “amount of charge received”, and “how to make an appointment and receive a charge”. Explanations related to these items are provided below.

In telepractice, if the meetings are held by phone, the clients make the telephone call, and therefore, the cost of communication or, in other words, the cost of holding the meeting will be paid by the clients themselves.

Therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience, said, “I should say that they call on themselves; if it is a telephone call, it means that the cost of contacting the parents is with the clients themselves because they call themselves.”

In video communications or internet-based communications in general, the cost of the session will be on both the therapist and the client.

“If it is WhatsApp, the Internet is consumed, and there is a two-way cost”, said therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience.

Several therapists receive the telepractice visitation fee, which is the same as the face-to-face treatment. Some other therapists believe that because this treatment method has less technical costs than face-to-face treatment, a lower visitation fee can be received. These costs include the percentage of payment to the clinic, the salary of the secretary, the cost of commuting, and the internal costs of the clinic.

Therapist No. 6, opposed to telepractice, said, “I think it is logical because the clinic fee is not paid here; 70% of the clinic fee should be paid.”

Therapists usually do not have a problem receiving the visitation fee of telepractice and receive this fee from the clients before or after the treatment session.

“I received the fee after the meeting. I asked them to transfer the fee to my credit card”, said therapist No. 1, who has 6 years of telepractice experience.

Many therapists receive the fee directly from the client and do not use a secretary for this reception or even give appointments. However, several therapists who own the clinic leave all the steps of giving appointments and payment to their secretaries.

Therapist No. 3, with 14 years of telepractice experience, said, “I give the credit card number, and they transfer the money. First of all, I never give my credit card number; I give the secretary a credit card number, usually like this. The secretary does everything. I do not communicate directly with clients at all.”

Efficiency of telepractice

This method of providing treatment by therapists has advantages for the therapist and the parent, considering the cases mentioned in relation to the cost. The efficiency of the telepractice category includes the subcategories of “cost-effectiveness of telepractice” and “effectiveness of telepractice”, whose subcategories are explained below.

Doing telepractice reduces technical costs for the therapist. The therapist who performs telepractice does not usually pay a percentage to the clinic, in addition to the cost of renting the clinic, the salary of the secretary, the cost of commuting to the clinic, and other current clinic costs are cut off and therefore makes this treatment more economical for the therapist.

“Telepractice, since the technical costs are not on the therapist, is cost-efficient for the therapist who does not have to pay a percentage to the clinic”, said therapist No. 4, with 5 years of telepractice experience.

The commuting cost is cut off for parents. Also, other side expenses, such as purchasing a prize for the child and any costs incurred on the way to the clinic, will be eliminated.

“Face-to-face meetings cost me more because we had to buy a prize for each session the doctor would give to my child. Then we would go for a walk together with the same clinic friend or a playhouse or a park and finally have a meal. Sometimes, we went out for lunch; sometimes, we went for dinner. Well, my side expenses were very high when we went to the clinic. Well, for me, the side costs are much lower now.” said parent No. 1 at the telepractice maintenance stage.

Most therapists believe telepractice is as effective as face-to-face therapy and can be a good alternative. Of course, this can only happen if the therapist has expended the necessary energy to perform this procedure to achieve the best possible result.

Therapist No. 4, with 5 years of telepractice experience, said, “Telepractice compared to face-to-face therapy, I can say that both have almost the same effect, for a family-centered program is exactly the same, and for children who are a little older, it is almost the same.”

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the stuttering telepractice treatment for preschool children. Analysis of the obtained data indicates that “telepractice efficiency” is the main concern of parents and therapists. All participants were somehow concerned about the efficiency of this treatment method and tried to help increase the efficiency of telepractice by using certain strategies. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between concepts and their relationship with the central concept. This Figure shows that telepractice-related processes happen in the context of “choosing telepractice”, “family and client characteristics”, and “the technology and knowledge to apply it.”

This study indicated that parents choose telepractice for reasons such as lack of therapists, commuting problems, and the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years. Some parents also prefer to receive their treatment in person because the child’s social connections are reduced in this method. Of course, to solve this problem, therapists hold virtual group therapy sessions to improve the child’s social connections.

Another context affecting the telepractice process is the characteristics of the family and the client. Stress and anxiety of the family and the clients can negatively affect stuttering [21، 22]. Participants in this study believed that the treatment in the child’s natural environment and among familiar people can significantly reduce stress and anxiety in the child. Other studies in this field have shown that children’s stress levels are low during telepractice [23]. Parents’ personality characteristics can affect their level of cooperation, which is very important in telepractice due to the greater responsibility of parents. Therefore, teaching therapeutic methods to parents must be done correctly and accurately. This study shows that therapists use various methods to educate parents, such as producing educational content and carefully examining the quality of education. These results are consistent with the recommendations presented in the study by Philp et al., whose authors suggested that educating parents can be done offline through producing educational content or online and in a meeting where it is possible to see how the parents perform the treatment and give feedback to the parent by the therapist [24].

Another thing that influences the telepractice process is the technology and the knowledge to use it. Some studies have reported that a speed of 384 kbps is suitable for a quality video connection. This study also suggests that applications that can adapt the quality of communication with speed should be used so that the connection between the therapist and clients is not disconnected if the speed is reduced [25].

As shown in Figure 1, one of the components of telepractice is the therapist’s skill for telepractice. The therapists participating in this study believed that to increase the efficiency of telepractice, they should raise their scientific and clinical skills in this field and receive specific training in this treatment method. Studies in this field have also shown a more efficient telepractice when the therapist engages in training in applying technology and solving potential technology-related problems [25]. This training includes interviewing and evaluating bilaterally, visually, and aurally, and familiarity with communication concepts [26] and interpersonal communication on the Internet [27].

Therapists must improve their communication skills to increase the efficiency of telepractice and improve their scientific and clinical skills. Appropriate communication skills and the effect on the implementation of treatment and education of parents also affect the level of parents’ trust. The trust between the therapist and the parent is another important factor affecting the treatment, which, in addition to the therapist’s communication skills, is also influenced by other factors. The results of this study demonstrated that the therapist’s reputation could also help build trust between the therapist and clients, such as referrals from other professionals and people whom parents trust. These results are consistent with the results of a study conducted by Li et al. and Van Velsen et al. [28، 29]. The results of this study show that therapists use social media advertising to increase their clients’ trust and their knowledge of families. These results align with the study conducted by Househ et al., which shows that social networks can increase the client’s participation, independence, motivation, and trust [30]. Another strategy therapists use to increase client trust is building relationships between families. Therapists try to connect families by creating virtual groups and transferring experiences between parents, increasing their trust in the therapist, raising parents’ awareness, and reducing parents’ stress. In addition, therapists hold face-to-face meetings for some parents to increase their trust, which is consistent with the results of Van Welsen’s study, which showed that face-to-face meetings help decide whether to trust the therapist and increase trust [29]. In addition, the results of this study indicate that the trust between the therapist and clients is formed gradually, which is also mentioned in the study of Eslami Jahromi et al. [23].

Another component in this field is the payment system for telepractice fees. Regarding the receipt of costs, the results of this study show that therapists do not face any particular problem in this regard. Although there is disagreement among therapists about the amount of the fee, it can be said that most therapists believe that the amount of visitation fee should be similar to face-to-face treatment or that because telepractice has fewer side costs for the therapist, fewer visitation fees can be received compared to face-to-face treatment. Studies on the cost of telepractice have also reported that telepractice has similar or lower costs for the therapist [31]. As mentioned, these costs can affect the visitation fee received from the client.

Two other important issues the participants emphasized are the relationship between the therapist and the parent in the sessions and holding group sessions. According to the results, the therapist-parent relationship between sessions can positively affect the treatment process, and parent education, and reduce parents’ stress. Group sessions can also help increase the child’s social interactions and motivate them to do the therapeutic practices.

Finally, the results of this study show the qualitative effect of telepractice and indicate that this treatment method can reduce the stuttering severity of preschool children as much as face-to-face therapy. Other quantitative studies comparing the impact of face-to-face therapy and telepractice reached similar findings [9-11]. Another consequence of this method is the cost-effectiveness. The findings of this study show that this treatment reduces the side costs of treatment, such as commuting, etc. for parents and technical costs, such as renting a clinic, and so on. In addition, therapists can expand their geographical area and make more money by doing telepractice. Therefore, it can be stated that telepractice can lead to the same quality of treatment as in person but at a lower cost.

One of the limitations of this study was that all parents participating were female, and the researcher could not find a man responsible for treating the child in telepractice. It is suggested that studies be conducted to teach therapists how to perform telepractice so that it can be used to change the curricula of university education and in-service education of therapists.

Conclusion

The findings of this study show that all participants are somehow concerned about the efficiency of telepractice. All of them aim to use strategies to increase the efficiency of telepractice. The analyses indicate that the concepts of “characteristics of family and clients”, “technology and the knowledge to apply it”, and “hesitation in choosing telepractice” as a context affect telepractice and the concepts of “therapist skills for telepractice” and “payment system for telepractice fees” are processes and seeks to improve the efficiency of telepractice. The results of this study can be used to prepare educational curricula for students and in-service education for therapists. Finally, using the telepractice features described in this study, it is possible to increase the quality of services provided remotely for stuttering preschool children and fill the gaps.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

In this study, a numeric code was given to each participant. The names of the participants will not be published anywhere to protect the participants’ information and privacy. Participants entered the study with informed consent and could refuse to continue collaborating in any part of the study, including the interview and the member check. In this study, the observance of ethical issues was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.238).

Funding

This article was extracted from the PhD dissertation of Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari, approved by Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Sciences, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Abbas Ebadi, Akbar Darouie, and Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari; Methodology: Abbas Ebadi; Analysis: Abbas Ebadi and Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari; Drafting, research, and review of resources: Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravar; Supervision, validation, editing, and final approval: Akbar Darouie and Abbas Ebadi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all participants, including therapists and parents of children with stuttering.

References

Stuttering is a type of disfluency in speech that may occur during the developmental period or in adulthood due to trauma. Stuttering exhibits symptoms such as block, prolongation, or repetition [1، 2]. Based on age, stuttering can be divided into three types: Preschool children, school-age children, and adults [1، 3].

Various texts on stuttering have emphasized that early intervention increases the probability of recovery and accelerates spontaneous recovery. Accordingly, providing treatment to preschool children becomes particularly important [4، 5]. To conduct the programs for stuttering therapy, the person with stuttering must go to the medical centers several times a week and receive the desired treatment. These regular visits may be impossible sometimes due to various reasons such as lack of therapist, long distance between home and clinic, and physical condition of the patient [5، 6]. Another case that decreased face-to-face visits to speech therapy clinics over the last three years is the COVID-19 pandemic, depriving people of speech and language therapies [7].

Information and communication technology enables therapists to provide their treatments remotely to people needing speech therapy services. Providing services using information and communication technology eliminates travel time to clinics or clients’ homes for individuals and therapists. In addition to allowing people to benefit from rehabilitation services regardless of geographical distance, the therapist can provide services to more people [8]. So far, several studies have been conducted to evaluate the efficiency of stuttering telepractice, and these studies have indicated the positive effect of this method of providing treatment on the severity of stuttering [9-11].

Reviewing studies on stuttering telepractice has shown problems with this treatment method. These problems include therapist training, insurance and payment issues, and country policy issues [12، 13]. One of these studies was a review on the topic of telepractice conducted by Theodores (2011). This study examined the benefits, scientific evidence, challenges, and future of telepractice. The challenges in the study relate to professional issues, reimbursement, clinical outcomes and usefulness, and available technology. At the end of this study, the authors suggested conducting more studies on the efficacy of this method of treatment [14]. A more accurate and deeper identification of the problems in this treatment method is the first step to improving the quality of telepractice services.

The study of Skeat and Perry (2008) recommended using the grounded theory method in studies related to speech and language, and the resulting theories can be used as a basis for other studies [15]. The grounded theory method is used when a phenomenon is not well described or when there are few theories to describe it. In the grounded theory, the main concerns and problems of the participants are identified, and a descriptive framework is explained for it. In this theory, the concepts that make up the theory are extracted from the data collected during the study and are not pre-selected as in some qualitative studies. In this type of study, data collection and analysis are interdependent, and data analysis is done by collecting the data continuously. These factors distinguish grounded theory from other qualitative research methods [16].

The purpose of this qualitative study is to investigate the process of telepractice in preschool children’s stuttering using the grounded theory method. By accurately identifying this process, a step can be taken to increase the quality of telepractice for preschool children stuttering.

Materials and Methods

The present qualitative research is a grounded theory study. A qualitative study helps the researcher gain in-depth and detailed insight into a particular subject. Qualitative studies help collect and describe phenomena in existing contexts using disciplined methods [17]. This method can help understand a phenomenon better and more profoundly. In grounded theory, participants’ main concerns and problems are identified through a process, and a descriptive framework is explained [15].

This study was conducted in Iran. To maximize diversification, participants from Tehran, Isfahan, Khorasan Razavi, South Khorasan, Yazd, Shiraz, and Hamedan provinces were selected using purposive sampling. This study was conducted between November 2020 and February 2022.

Study participants

A total of 14 participants were included in this study, comprising 5 therapists with telepractice experience, 4 therapists who were opposed to telepractice, 3 parents with successful treatment experience, and 2 parents with telepractice withdrawal experience (Tables 1 and 2).

After each interview, it was analyzed. By theoretical sampling, more interviews were conducted with parents who had successful or unsuccessful treatment and telepractice therapists. The sampling process continued until reaching data saturation. Saturation is a point in which the analysis process where a new concept is not extracted after further analysis of the interviews [18].

Interview procedure

In this study, unstructured interviews were used to collect data because free interviews can provide the most data to the researcher. This type of interview also provides the possibility of theoretical sampling for the researcher. The interview started with an open-ended question like “please explain your experience in telepractice for stuttering in preschool children”. At each point of the interview that was ambiguous for the interviewer or needed further explanation, the interviewer asked questions from the participant to clarify the issue. Interview sessions were conducted to obtain consent from the participants in voice calls using WhatsApp. Interviews took 35 to 66 minutes, with an average of 49 minutes.

It should be noted that the first author of this study conducted the interviews. The interviewer is a PhD student in speech therapy with a history of conducting research in the field of telepractice.

Data analysis

The obtained data were analyzed using Strauss and Corbin method version 2015 (Corbin, 2015#400). The steps of this method include open coding, examining concepts to find their dimensions, analysis for context, process, and integration. MAXQDA software, version 2020 was used for data analyses. In this study, the criteria proposed by Lincoln and Guba were used to increase the reliability of the data: Credibility, transferability, confirmability, and consistency [19، 20].

Credibility in qualitative studies increases the probability of obtaining valid findings. This study tried to increase the credibility and accuracy of the findings with the researcher’s long-term involvement (about 2 years). Also, some data were given to other research team members, who were asked to analyze the data and extract its concepts. Another method used to increase the credibility of the data was to review the results of the analyses by the participants.

Transferability or appropriateness is equivalent to generalizability in quantitative studies, which shows how much research findings can be applied in similar situations. To increase transferability in this study, we tried to provide a detailed description of the participants so that the readers of this study report can get to know the characteristics of the participants.

Confirmability shows how much the results are based on the data and not influenced by the researcher’s bias. To increase confirmability in this study, notes were taken, and reports were written during the analysis so that the readers of the reports could achieve similar results by following them.

Consistency of qualitative studies is equivalent to reliability in quantitative studies and refers to the stability of the data pattern at another time. To increase consistency in studies, there should be auditability, which means that another researcher can follow up on the entire study process and decisions made in the study. In this study, to achieve consistency, we tried to record and report all the steps and the whole study process accurately so that the readers could perform the audit using these reports.

Results

During this study, a total of 1046 primary codes were extracted. These codes were combined by continuous and constant comparison based on their similarities and relationships, and primary categories, subcategories, and main categories were finally developed. In total, 6 main categories, 17 subcategories, and 63 primary categories were extracted in this study (Table 3).

The main categories include “hesitation in choosing telepractice”, “family and client characteristics”, “technology and knowledge to apply it”, “therapist skills for telepractice”, “payment system for telepractice fees”, and “efficiency of telepractice”. The conceptual model shown in Figure 1 was developed using the extracted concepts. According to the analysis, “efficiency of telepractice” was identified as the central concept. The results of the study are described below. It should be noted that quotes are given as examples among the explanations related to categories.

Hesitation in choosing telepractice

Several families have chosen telepractice due to some problems. Many other families hesitated to choose this method due to facing some issues, abandoned it, and turned to face-to-face treatment. The category of “hesitation in choosing telepractice” has three subcategories: “reasons for not choosing telepractice”, “reasons for choosing telepractice”, and “reasons for discontinuation of treatment”, which are explained below in relation to these subcategories.

The lack of therapists, the long distance between the clinic and the client’s home, and the COVID-19 pandemic over the last three years are the reasons parents have chosen telepractice.

“Commuting was very important for me; it is not okay in this crowd and this situation, well, if there was a possibility for a face-to-face visit now, well, definitely, I could not go because now in this outbreak of, it is not really good to be in a clinic.” Said parent No. 5, who withdrew from telepractice.

One of the reasons therapists choose telepractice is to expand the geographical area they cover and increase their income.

“My situation is such that I cannot work in a crowded city to earn more income and have time in the field of stuttering the way I want to and get both economic and scientific results.” Said therapist No. 2 with 3.5 years of telepractice experience.

Trusting the therapist is one factor affecting parents’ choice of telepractice. If the parent does not trust the therapist, even the therapist is reluctant to do the treatment remotely.

Therapist No. 3, with 14 years of telepractice experience, said, “I personally do not telepractice with clients who do not trust me. Okay? That is, if they are not introduced before, I personally will not work with them remotely.”

Parents’ daily work may cause them to stop telepractice and choose face-to-face therapies to reduce their responsibilities and have their child’s therapist take care of the children.

“In online treatment, since I have to be completely at my daughter’s demand and I really did not have the opportunity to let this happen, I said, let’s see what decision we have to make after this summer.” Said parent No. 5, who withdrew from telepractice.

Some parents prefer to receive treatment in person because telepractice reduces the child’s social interactions, and the child receives treatment at home without contact with other people.

Parent No. 4, who refused telepractice, said, “The child becomes more social in face-to-face communication. At least, he learns how to behave in the community with someone other than his family and how to treat and talk to them.”

Characteristics of family and clients

In general, the family plays an essential role in treating preschool children’s stuttering. In telepractice, the therapist interacts more with the parent and tries to perform the therapy by educating the parents. Therefore, family characteristics become more important for telepractice. It seems that the amount of parental cooperation in the treatment process depends on the characteristics of each family. Also, the stress and anxiety of the family, which is seen in the families of children with stuttering, affects this process. This category is composed of the subcategories “the role of parents in telepractice”, “the influence of cultural, economic, and social factors on treatment”, and “the influence of stress and anxiety on stuttering and its treatment”, which are further explained in relation to these subcategories.

The results indicate that in telepractice, the therapist interacts more with the parents than the child. Accordingly, the burden of parents’ responsibility in telepractice increases. Therefore, parents should have a high level of cooperation with the therapist in this treatment.

“In the way we had, the Lidcombe program was much more responsible because I did everything myself.” Said parent No. 3, who had successful treatment.

Also, the participation and cooperation of other family members in the treatment is very important. In addition to reducing the burden on the parent in charge of treatment, it also helps to adapt the child’s living environment and achieve a better result.

Parent No. 5, who refused telepractice, said, “It can be said that practice is a way in which all the members who live together in the same house or even the one who enters the house as a guest, all have to come to something in common, understand the situation and talk in almost the same way that the speech therapist said.”

The parent’s level of education can affect the quality of education and make the parent learn and apply the education provided by the therapist better.

Parent No. 3, who successfully completed telepractice, said, “I think at some points, the mother’s education can also affect your understanding of what your therapist means. I think this is important.”

The conditions of the house, such as the number of people and the presence of the child’s siblings, can make it difficult for the parent to prepare for the treatment environment.

“Sometimes when I came to talk, I just had to tell my kids “Don’t.” I was pointing down with my hand. When something was falling, I would catch it. It is distracting. I was looking at the clock like it’s three-thirty, and it ends in ten minutes instead of enjoying sessions.” said parent No. 5, who rejected telepractice.

Using telepractice is not fully accepted among clients, and clients view face-to-face treatment as the gold standard and prefer to receive treatment as a combination of face-to-face and telepractice.

“I always thought that face-to-face therapy might be another way; maybe it would help a person better, and the child would have a better relationship with the therapist. I mean, if our communication were in person, or at least once in a while, every two months, once every three months, it would help. Then we would go there and see other children; we would see other mothers.” said parent No. 2, who was at the maintenance stage.

Family characteristics such as education level, belief in telepractice, and economic and social level affect parents’ cooperation.

Therapist No. 5, with 4 years of telepractice, said, “Their level of education definitely affects their cooperation. Their social economy is effective in this case, and I mean their social class. Even their economics are effective in this case.”

Presence in the clinic, encountering strangers, and the therapist’s presence in face-to-face therapies may increase the child’s stress. These are less common in telepractice because the treatment is provided in a familiar home environment.

Parent No. 4, who rejected telepractice, said, “However, he does not feel that the person next to him is more tormented. Like an online classroom, it is very different from a face-to-face classroom. The child has more control, sits, has confidence, sits next to me, and talks, but in face-to-face therapy, which is not the case, the child goes into a non-family room, for example, talking to strangers, which is very different.”

In general, parents of children with stuttering experience high-stress levels. Parents’ awareness of the nature of stuttering, its treatments, and the future of stuttering can help reduce their stress.

Therapist No. 2, with 3.5 years of telepractice experience, said, “In the issue of stuttering, children’s parents have a lot of stress, are very worried, and are really confused. And if there is no one with them along the way, stress exaggerates the stuttering in the child.”

Technology and knowledge to apply it

It is necessary to have a suitable platform for remote communication. In addition to the existence of a suitable platform, the level of knowledge of the people who should participate in this communication is also essential in using the existing technology. The category of “technology and knowledge to apply it” is composed of the subcategories of “infrastructure problems in telepractice”, “the need for a special software for telepractice”, and “familiarity with technology”, which are explained in the following section in relation to these subcategories.

Problems such as slow Internet and disconnection may occur during telepractice sessions. Based on the results, these problems do not interfere with the meetings, and if the connection is lost, it is re-established, and the meeting starts again.

“Well, when the call is disconnected, we make the call again and continue. There is no problem in the middle. I do not show a negative reaction, nor does the parent because we are both familiar with the situation.” said therapist No. 2, with 3.5 years of telepractice experience.

To perform telepractice, therapists use common and available applications such as WhatsApp and Skype. WhatsApp is more common because it is user-friendly.

Therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience, said, “Now we have a lot of software that can make video and voice calls. For example, we can use Skype. There is WhatsApp for video calls, Telegram, and Imo; it can be done whatever it is. The quality is almost the same. I myself did my treatment with WhatsApp; the contacts we had were mostly with WhatsApp.”

In some treatment programs, such as Lidcombe and FRP, it is crucial to provide feedback to clients. Having software that allows the child to provide feedback can be very helpful.

Therapist No. 2, with 3.5 years of telepractice experience, said, “Sometimes we have a meeting with the child, and this software only supports video calling. I like to show the child a picture, and at the same time, I see that picture, and the child sees that picture, I would like to send him a sticker because I want to give him feedback. Skype somewhat works for us, which is why I use Skype.”

Therapist skills for telepractice

For the therapist to effectively provide telepractice, he/she must have skills to solve specific problems and conditions encountered during the treatment. Therapist skills for telepractice consist of subcategories, including “therapist communication skills”, “therapist training for telepractice”, and “treatment program management ability”. Below are explanations related to the subcategories.

In telepractice, trust between the therapist and the client may develop later or cause problems. Responsiveness and a high scientific level of therapists significantly impact trust.

Parent No. 1, at the maintenance stage, said, “Look, all this trust in the therapist was formed for me when I saw the therapist’s knowledge.”

Establishing communication between parents of children with stuttering can significantly help increase client trust in the therapist, transfer experiences, and increase parents’ awareness. The therapist must also have the skills to communicate with parents and how to deal with parents.

Parent No. 2 at the telepractice maintenance stage said, “Another thing that helped me gain more trust was that I read other mothers’ comments, I was in contact with them, we had an information exchange, as the famous saying goes, and I saw that there are mothers who trust them like this, then I can trust them, and this trust is growing every day.”

The problem of trusting the therapist is not seen in parents to whom a trusted person has referred.

“When a colleague refers them, their trust will increase. In this case, I have never experienced this problem. Because the referrals I experienced were all from colleagues”, said therapist No. 3, with 14 years of telepractice experience.

The therapist’s reputation as a specialist and experienced therapist in the field of stuttering significantly impacts the therapist’s trust.

Therapist No. 8, who opposed telepractice, said, “I know several cases, therapists who work in stuttering and are much better known. Now, I do not know exactly what their job is, but I know that the more well-known and experienced therapist naturally has more family trust.”

Therapists’ skills for producing and publishing training content on stuttering on social media and therapist activities on social media, in general, can affect trust as some parents search on social media to find a specialist therapist. Therapists’ skills for producing and publishing training content on stuttering on social media and therapist activities on social media, in general, can affect trust as some parents search on social media to find a specialist therapist.

Parent No. 5, who refused telepractice, said, “Before I started the treatment, I followed their page for about 6 months, that is, the posts they sent, the information they posted, and I checked to see if they talk up to date.”

The ability to communicate positively and effectively with both parent and child can constructively affect the treatment process and trust in the therapist.

Therapist No. 7, who opposed telepractice, said, “That effective communication is key either in face-to-face therapy or telepractice. If not, a large part of the treatment is lost.”

The therapist’s experience and communication skills with the child can affect the therapist’s interaction.

Parent No. 4 withdrew from telepractice and said, “The interaction was like face-to-face therapy. For example, if we had 45 minutes, or half an hour if it was half an hour, 20 minutes with the child, 10 minutes with me. Otherwise, if it was 45 minutes, half an hour with the child. They talked to me to tell me tips to follow to treat my child at home so I could work with the child.”

Most therapists believe that to perform a successful telepractice; the therapist must increase his or her scientific and clinical skills through specialized training in this field.

“I think they need to be given a series of training on distance therapy and telepractice, yes, 100%. And I don’t think it’s going to take a student’s time to take a course or two; it can replace another course, which I don’t think is very practical, and yes, it would be great if these courses were given at the university.” said therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience.

Therapists must also have sufficient skills in the use of technology. Therefore, they should receive training in this field to use technology effectively to achieve telepractice goals.

Therapist No. 8, who opposed telepractice, said, “There may be a series of cases or even a series of tutorials on using technology that can help me do this.”

The therapist should be able to evaluate the child remotely and, in addition to the evaluation via video calls, ask the parents to record a sample of the child’s speech in a few-minute video and send it to the therapist for more accurate evaluation.

Therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience, said, “Before beginning the first session, I asked them to take a sample in the form of a film for about four or five minutes, and some of them liked to send the voice, but I said that I should also see the child’s face, they would send the film, and I could have an initial view. But the evaluation was not 100%; the film was a part of our evaluation.”

Generally, therapists do not have any particular problem with the evaluation and usually use the speech sample and the stuttering severity rating for the assessment and believe that using formal evaluations due to being structured can give accurate results to the therapist.

Therapist No. 7, who opposed telepractice, said, “I think we do not have a problem with stuttering evaluation because, in any case, we have a formal evaluation tool for stuttering, which is SSI 4. It is an official tool that is completely defined and predetermined. This means that if we have face-to-face treatment, we will record a video and inform the family about the severity of stuttering in the next session to make our assessment more accurate. And if we want to inform the family in the same session, we will resort to the SR form, which says the severity more qualitatively.”

The therapist must be able to choose the best and most appropriate treatment plan for the child by considering various factors. Therapists also consider the family situation when choosing the type of treatment. For example, suppose the family has good cooperation. In that case, the therapist may use parent-centered therapy, and if the parents are busy and do not actively cooperate, the therapist may use other treatment programs.

Therapist No. 4, with 5 years of telepractice experience, said, “One of the factors is the level of family cooperation and family perception; some families do not have enough cooperation, some families do not have enough understanding of how to implement, these conditions affect whether we want to run the program therapist-centered or parent-centered.”

Therapists believe that protocols for this method should be designed and made widely available to individuals. In addition, the presence of the protocol increases the motivation, interest, and skills of therapists in performing telepractice.

Therapist No. 7, opposed to telepractice, said, “If we have a guide for telepractice for the treatment programs that we now have, for example, for preschoolers, surely therapists’ trust and interest in telepractice will increase.”

In telepractice, the therapist allows the parent to communicate with them between sessions. If they have a question or encounter a problem, ask the therapist questions and resolve their problems.

Parent No. 2, at the treatment maintenance stage, said, “During this time, two weeks or one week, we ask the doctor if we have specific questions or problems. In this regard, we are assured that he is not with us at the time of the meeting, and they do not say that you must visit; you must take your time so that I can answer. No, they really answer, and this is very assuring.”

The therapist must also be able to hold and manage group sessions. Therapists emphasize group therapy and try to have a group session for each client in exchange for a few individual sessions. These group meetings may be synchronous or asynchronous.

“There are two therapists in a group; they offer the children a challenge, and all the children really participate in that challenge willingly. Yes. And that every day the children tell stories to each other, send conferences, tell their daily stories, their memories, everything that has happened.” said parent No. 1, who was at the maintenance stage.

Payment system for telepractice fees

One of the issues that both the therapist and the parent face is the cost of telepractice sessions. In addition to the holding costs, the amount of the received tariff and the method of receiving it should also be taken into consideration in this way. This category consists of the subcategories of “cost of technology used”, “amount of charge received”, and “how to make an appointment and receive a charge”. Explanations related to these items are provided below.

In telepractice, if the meetings are held by phone, the clients make the telephone call, and therefore, the cost of communication or, in other words, the cost of holding the meeting will be paid by the clients themselves.

Therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience, said, “I should say that they call on themselves; if it is a telephone call, it means that the cost of contacting the parents is with the clients themselves because they call themselves.”

In video communications or internet-based communications in general, the cost of the session will be on both the therapist and the client.

“If it is WhatsApp, the Internet is consumed, and there is a two-way cost”, said therapist No. 1, with 6 years of telepractice experience.

Several therapists receive the telepractice visitation fee, which is the same as the face-to-face treatment. Some other therapists believe that because this treatment method has less technical costs than face-to-face treatment, a lower visitation fee can be received. These costs include the percentage of payment to the clinic, the salary of the secretary, the cost of commuting, and the internal costs of the clinic.

Therapist No. 6, opposed to telepractice, said, “I think it is logical because the clinic fee is not paid here; 70% of the clinic fee should be paid.”

Therapists usually do not have a problem receiving the visitation fee of telepractice and receive this fee from the clients before or after the treatment session.

“I received the fee after the meeting. I asked them to transfer the fee to my credit card”, said therapist No. 1, who has 6 years of telepractice experience.

Many therapists receive the fee directly from the client and do not use a secretary for this reception or even give appointments. However, several therapists who own the clinic leave all the steps of giving appointments and payment to their secretaries.

Therapist No. 3, with 14 years of telepractice experience, said, “I give the credit card number, and they transfer the money. First of all, I never give my credit card number; I give the secretary a credit card number, usually like this. The secretary does everything. I do not communicate directly with clients at all.”

Efficiency of telepractice

This method of providing treatment by therapists has advantages for the therapist and the parent, considering the cases mentioned in relation to the cost. The efficiency of the telepractice category includes the subcategories of “cost-effectiveness of telepractice” and “effectiveness of telepractice”, whose subcategories are explained below.

Doing telepractice reduces technical costs for the therapist. The therapist who performs telepractice does not usually pay a percentage to the clinic, in addition to the cost of renting the clinic, the salary of the secretary, the cost of commuting to the clinic, and other current clinic costs are cut off and therefore makes this treatment more economical for the therapist.

“Telepractice, since the technical costs are not on the therapist, is cost-efficient for the therapist who does not have to pay a percentage to the clinic”, said therapist No. 4, with 5 years of telepractice experience.

The commuting cost is cut off for parents. Also, other side expenses, such as purchasing a prize for the child and any costs incurred on the way to the clinic, will be eliminated.

“Face-to-face meetings cost me more because we had to buy a prize for each session the doctor would give to my child. Then we would go for a walk together with the same clinic friend or a playhouse or a park and finally have a meal. Sometimes, we went out for lunch; sometimes, we went for dinner. Well, my side expenses were very high when we went to the clinic. Well, for me, the side costs are much lower now.” said parent No. 1 at the telepractice maintenance stage.

Most therapists believe telepractice is as effective as face-to-face therapy and can be a good alternative. Of course, this can only happen if the therapist has expended the necessary energy to perform this procedure to achieve the best possible result.

Therapist No. 4, with 5 years of telepractice experience, said, “Telepractice compared to face-to-face therapy, I can say that both have almost the same effect, for a family-centered program is exactly the same, and for children who are a little older, it is almost the same.”

Discussion

This study was conducted to investigate the stuttering telepractice treatment for preschool children. Analysis of the obtained data indicates that “telepractice efficiency” is the main concern of parents and therapists. All participants were somehow concerned about the efficiency of this treatment method and tried to help increase the efficiency of telepractice by using certain strategies. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships between concepts and their relationship with the central concept. This Figure shows that telepractice-related processes happen in the context of “choosing telepractice”, “family and client characteristics”, and “the technology and knowledge to apply it.”

This study indicated that parents choose telepractice for reasons such as lack of therapists, commuting problems, and the COVID-19 pandemic in recent years. Some parents also prefer to receive their treatment in person because the child’s social connections are reduced in this method. Of course, to solve this problem, therapists hold virtual group therapy sessions to improve the child’s social connections.