Volume 24, Issue 1 (Spring 2023)

jrehab 2023, 24(1): 132-149 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Heydari Z, Aminian G, Biglarian A, Shokrpour M, Mardani M A. Comparing the Effects of Lumbar-pelvic and Pelvic Belts on the Activity of Pelvic Muscles in Pregnant Women With Back and Pelvic Pain. jrehab 2023; 24 (1) :132-149

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3215-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3215-en.html

Zhaleh Heydari1

, Gholamreza Aminian1

, Gholamreza Aminian1

, Akbar Biglarian2

, Akbar Biglarian2

, Maryam Shokrpour3

, Maryam Shokrpour3

, Mohammad Ali Mardani *4

, Mohammad Ali Mardani *4

, Gholamreza Aminian1

, Gholamreza Aminian1

, Akbar Biglarian2

, Akbar Biglarian2

, Maryam Shokrpour3

, Maryam Shokrpour3

, Mohammad Ali Mardani *4

, Mohammad Ali Mardani *4

1- Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, School of Rehabilitation, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

2- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Female Pelvic Floor Medicine and Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine Taleghani Hospital, Arak University of Medical Sciences, Arak, Iran.

4- Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, School of Rehabilitation, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,natelnoory@yahoo.com

2- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Female Pelvic Floor Medicine and Surgery, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine Taleghani Hospital, Arak University of Medical Sciences, Arak, Iran.

4- Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, School of Rehabilitation, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 2177 kb]

(1691 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5820 Views)

Full-Text: (3372 Views)

Introduction

During pregnancy, the physical and hormonal changes that occur in the body cause skeletal and muscular discomforts and back and pelvic pain [1 ,2, 3 ,4]. During pregnancy, weight gain, belly pushing forward, displacement of the center of mass, increase in forces on the spine and ligament laxity, and as a result, changes in lumbar-pelvic posture and the movement pattern of the lumbar region can lead to skeletal-muscular disorders and increase muscle activity [8].

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction plays a crucial role in pregnancy-related back and pelvic pain [9]. Abdominal and pelvic muscles jointly create sacroiliac joint force barrier and hip flexion [10]. In case of damage to the mechanism of these muscles, the joint has less stability and is more exposed to shearing forces [11]. This condition leads to a change in the activity pattern of the lumbar and pelvic muscles and an increase in muscle activity to compensate for the anterior forces and bending torques caused by increasing the volume of the abdomen and creating a postural adaptation [1, 8, 12].

The active straight leg raise (ASLR) test is a valid and reliable test used to diagnose back and pelvic pain in pregnant women and can show the transfer of disturbed load through the sacroiliac joint in pregnant women with back and pelvic pain [13].

Pelvic belts in pregnancy improve muscle function [14], stabilize the pelvic joint, and reduce pain [15, 16], and by preventing muscle damage and reducing muscle activity and fatigue, they can reduce possible pains [17].

In previous studies, the activity of pelvic muscles in the ASLR test was evaluated in pregnant women without using a pelvic belt [18, 19]. The belts examined in the previous studies included a part around the pelvic ring, which can be slightly wider in the waist area for more support or be limited to the same pelvic ring. They were mostly designed at the level of the pubic symphysis or the upper anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). These orthoses do not fully support the lumbar region. A lumbar-pelvic belt can extend to below the lower angle of the scapula and fully supports the lumbar area and the waist and pelvis simultaneously by transferring movement from the back to the pelvis, compared to a pelvic belt. It can have a better force distribution in the back and pelvis area, and its positive effect has been shown in the improvement of pain and function of the back and pelvis and the quality of life of pregnant women with back and pelvis pain [20, 21]. So far, the lumbar-pelvic belt’s effect on the pelvic muscles’ activity during the ASLR test in pregnant women with back and pelvic pain has not been evaluated. Therefore, the present study aims to compare the effect of the lumbar-pelvic belt with the pelvic belt in the activity of pelvic muscles during the ASLR test in pregnant women with back and pelvic pain.

Materials and Methods

The present research is a clinical trial study (Registration code: IRCT20200925048833N1). The research population included pregnant women with pelvic and back pain related to pregnancy. The sampling method was convenience sampling among pregnant women with pelvic and back pain who had visited the Specialist and Subspecialty Clinic of Kowsar in Arak City, Iran. According to the Gemma study, considering the confidence interval of 95% and the test power of 80%, the variance of 15.16 units and the accuracy of 3.5 units [1], a sample size of 14, 14, 20, respectively, for the control groups, pelvic belt, and lumbar-pelvic belt were obtained. So, 48 pregnant women with back and pelvic pain were included in the study according to the inclusion and exclusion study. Then, they were randomly divided into three groups: pelvic belt, lumbar-pelvic belt, and control.

All participants signed the written consent form and then entered the study. First, all subjects completed the demographic questionnaire. Before the study and three weeks after the intervention, the muscle activity of the pelvic muscles was evaluated with the ASLR test. In the present study, two types of belts were evaluated.

A pelvic belt is a prefabricated belt. It is flexible, soft, and comfortable. It is made of three-dimensional fabric with hypoallergenic fibers and is placed around the pelvis under the upper ACL and lower abdomen.

The second one is the lumbar-pelvic belt, which has four abdominal, lumbar, pelvic, and shoulder straps. In this belt, the pelvic part is connected to the flexible lumbar-sacral orthosis (lumbar region). In addition to being soft and comfortable, it covers a wider area of the woman’s body.

To evaluate the muscle activity of the pelvic muscles during the ASLR test, a muscle electrical activity recording device equipped with 16 channels of the Mayon wireless model (made in Germany) was used.

To collect electromyography (EMG) data, the exact location of the electrodes on the muscles was identified and prepared based on the recommendations of the European Society of Electromyography [27]. The electrodes were placed on the rectus femoris and biceps femoris muscles. In the present study, the average muscle activity was determined based on the average amplitude of the signals. Due to the special conditions of pregnancy and the concerns about using the maximum voluntary isometric contraction test to normalize the data obtained from EMG, the signals of each muscle were normalized to the full activity value of that muscle during the same test [28, 29 ,30]. After refining the data, SPSS software, version 26 was used to analyze the data. A statistically significant level of <0.05 was considered for all tests.

Results

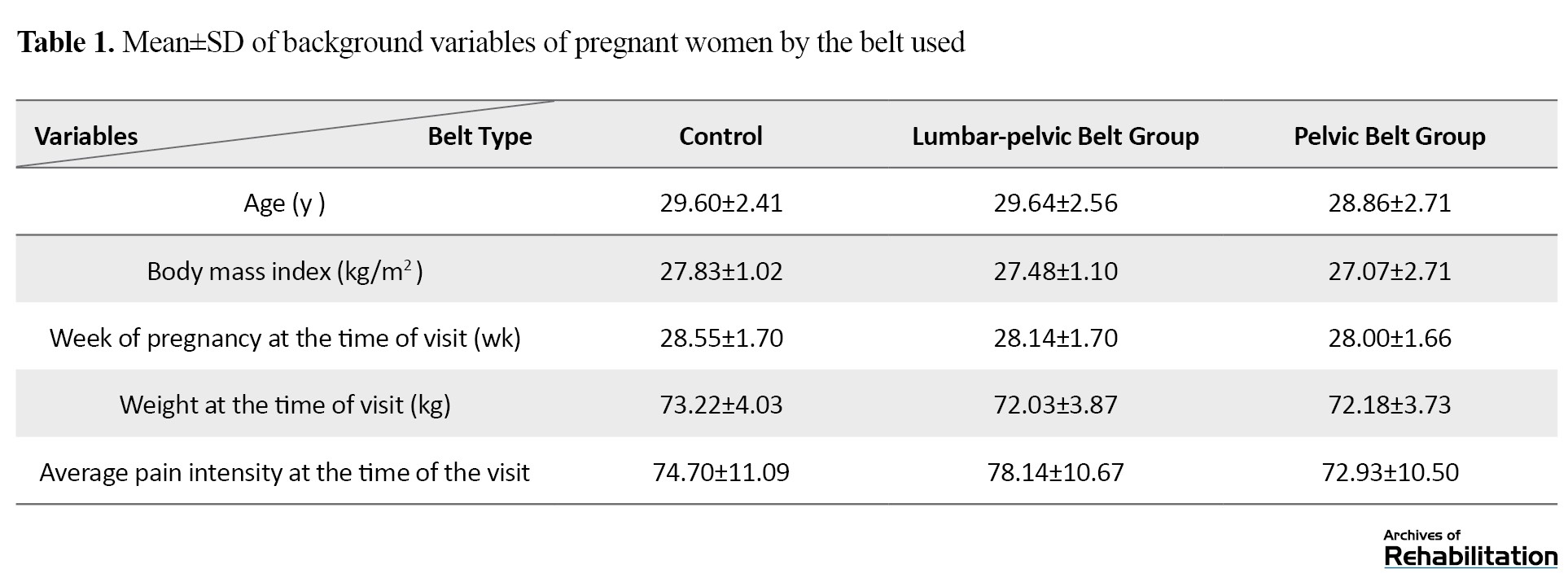

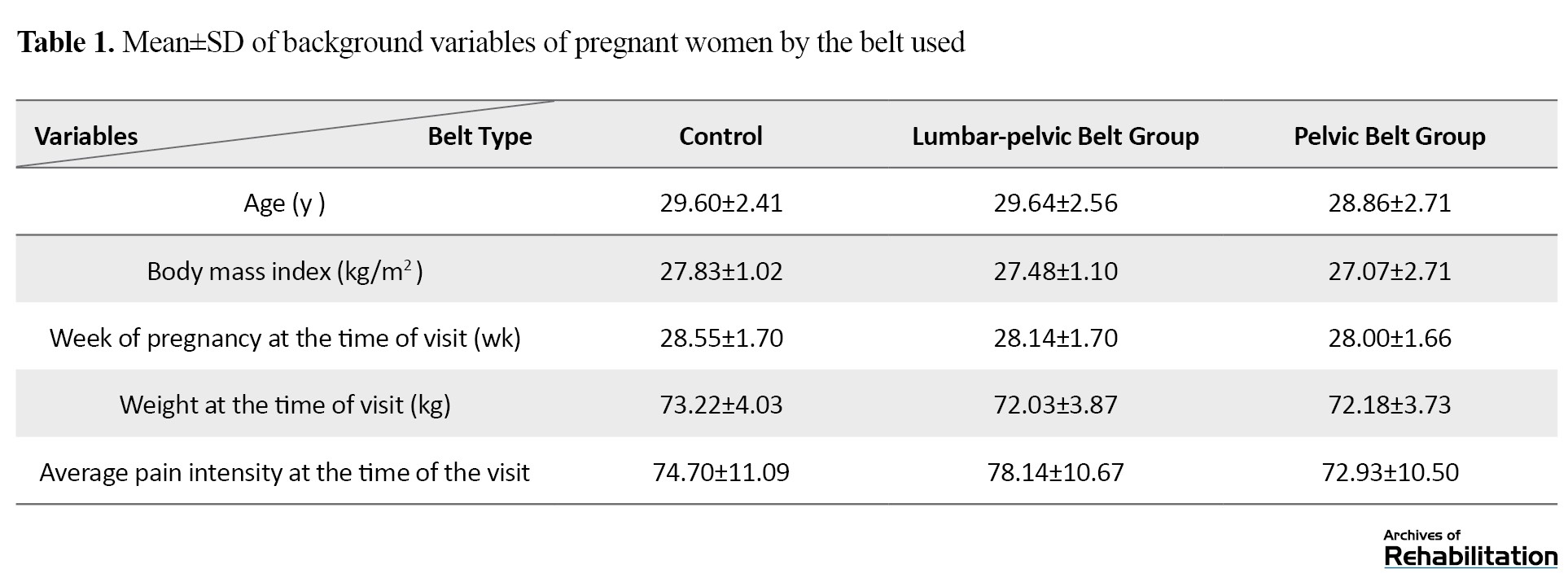

In the present study, 48 pregnant women with back and pelvic pain participated and were randomly divided into three groups: pelvic belt (14 people), lumbar-pelvic belt (14 people), and control group (20 people). Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviation of background variables of pregnant women participating in the study.

To check the normality of the muscle activity variable data, we used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the normality of the data was confirmed. The muscle activities of the right and rectus femoris and right and left biceps femoris muscles were assessed with the ASLR test before the study and three weeks after the intervention, and their mean and standard deviation were obtained (Table 2).

The results showed that three weeks after the administration of the belts, the muscle activity of all muscles during the ASLR in the two groups using the belt had a decreasing trend. In the control group, an increase in muscle activity was observed.

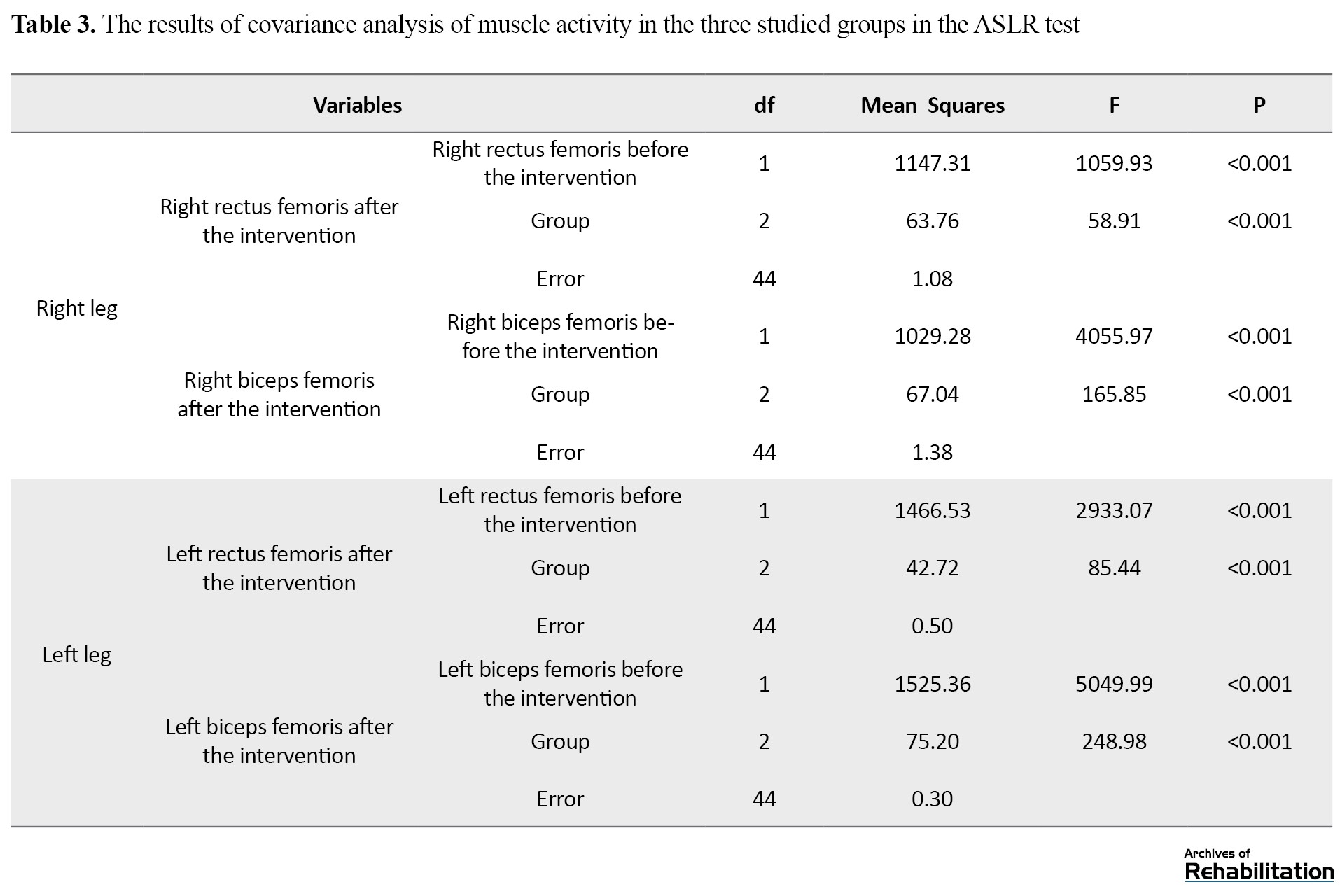

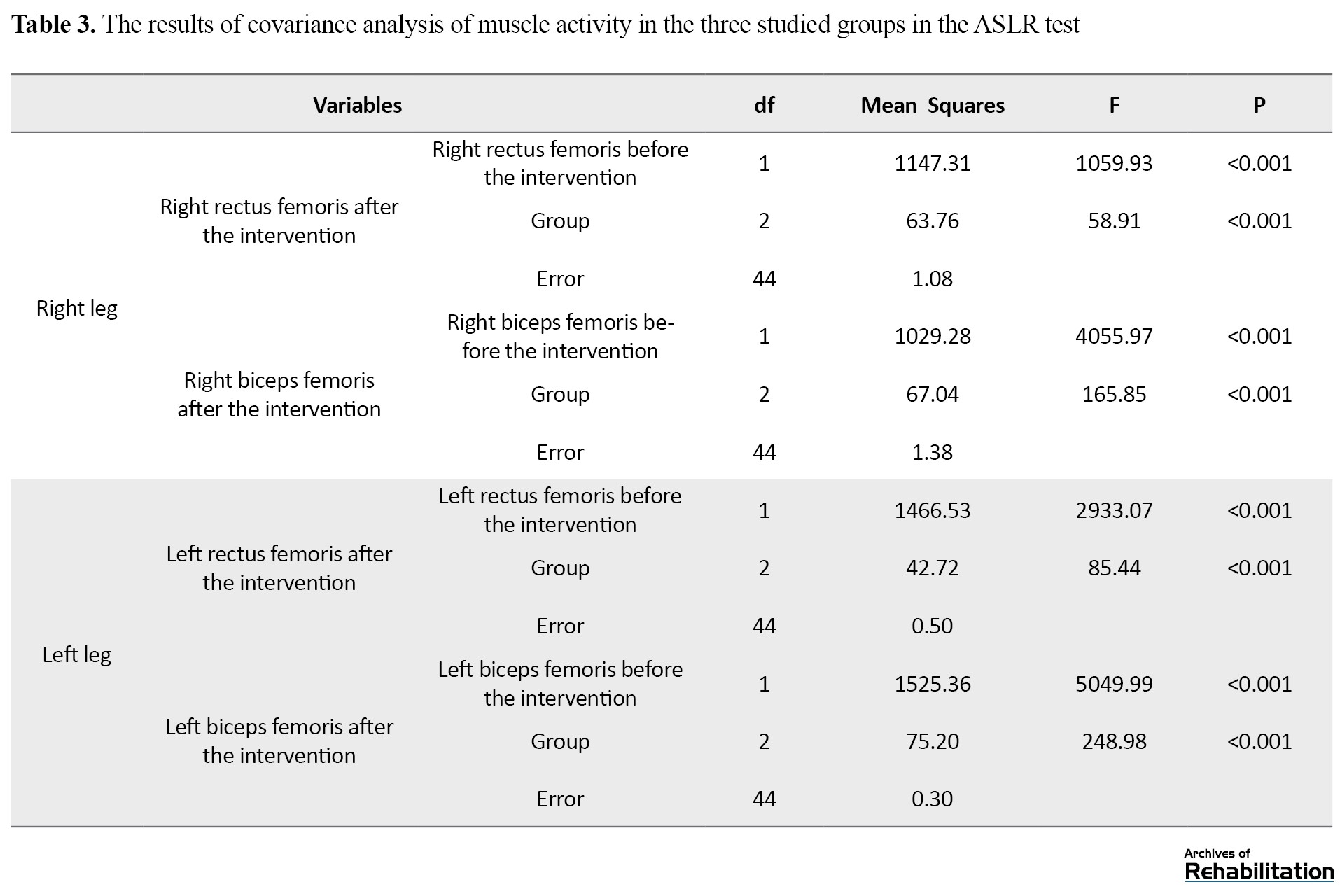

Muscle activity in the three studied groups in the ASLR test was analyzed using covariance analysis (Table 3).

The results showed significant differences between the groups in the right rectus femoris, left rectus femoris, right biceps femoris, and left biceps femoris muscles (P<0.001).

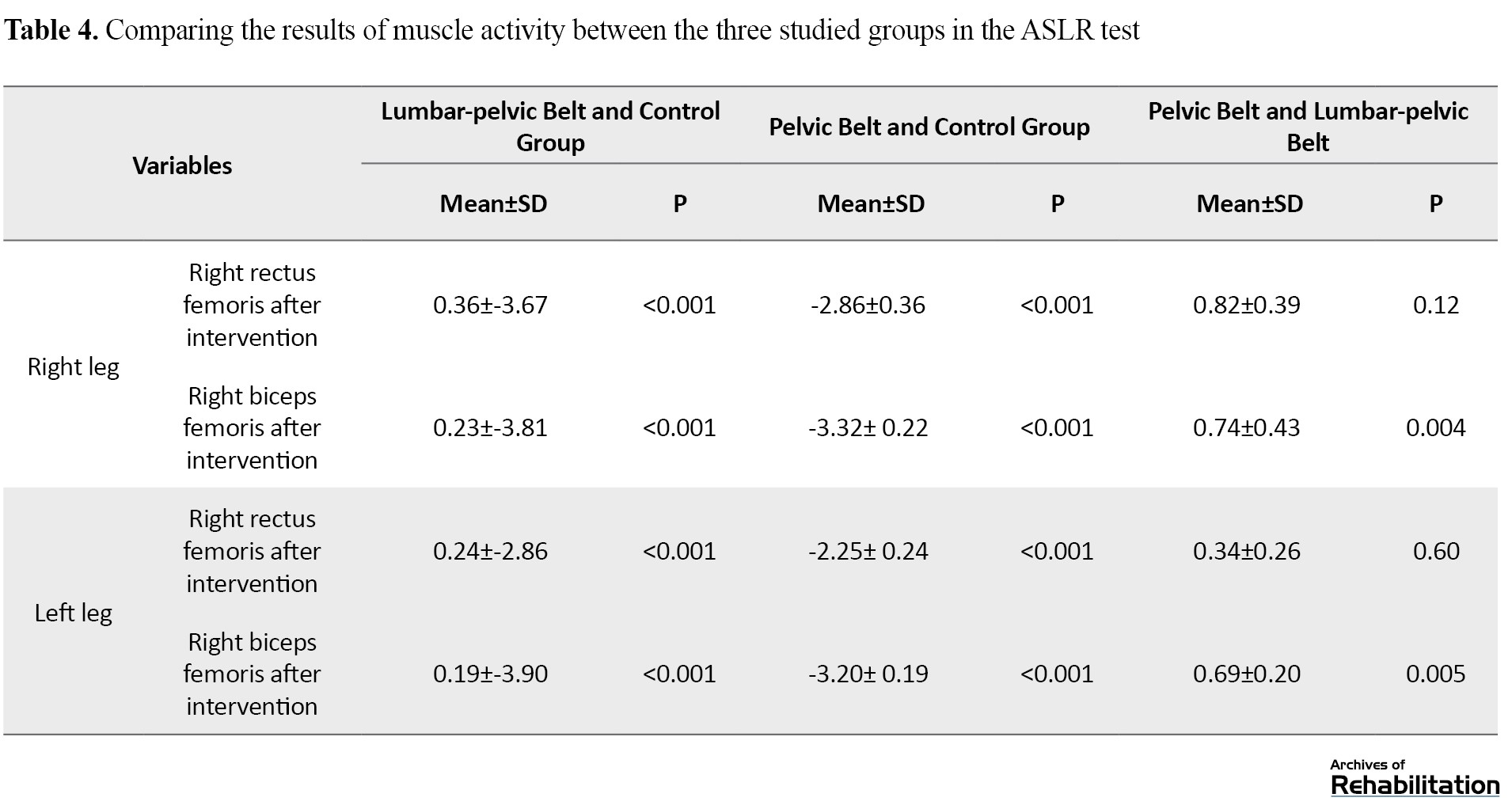

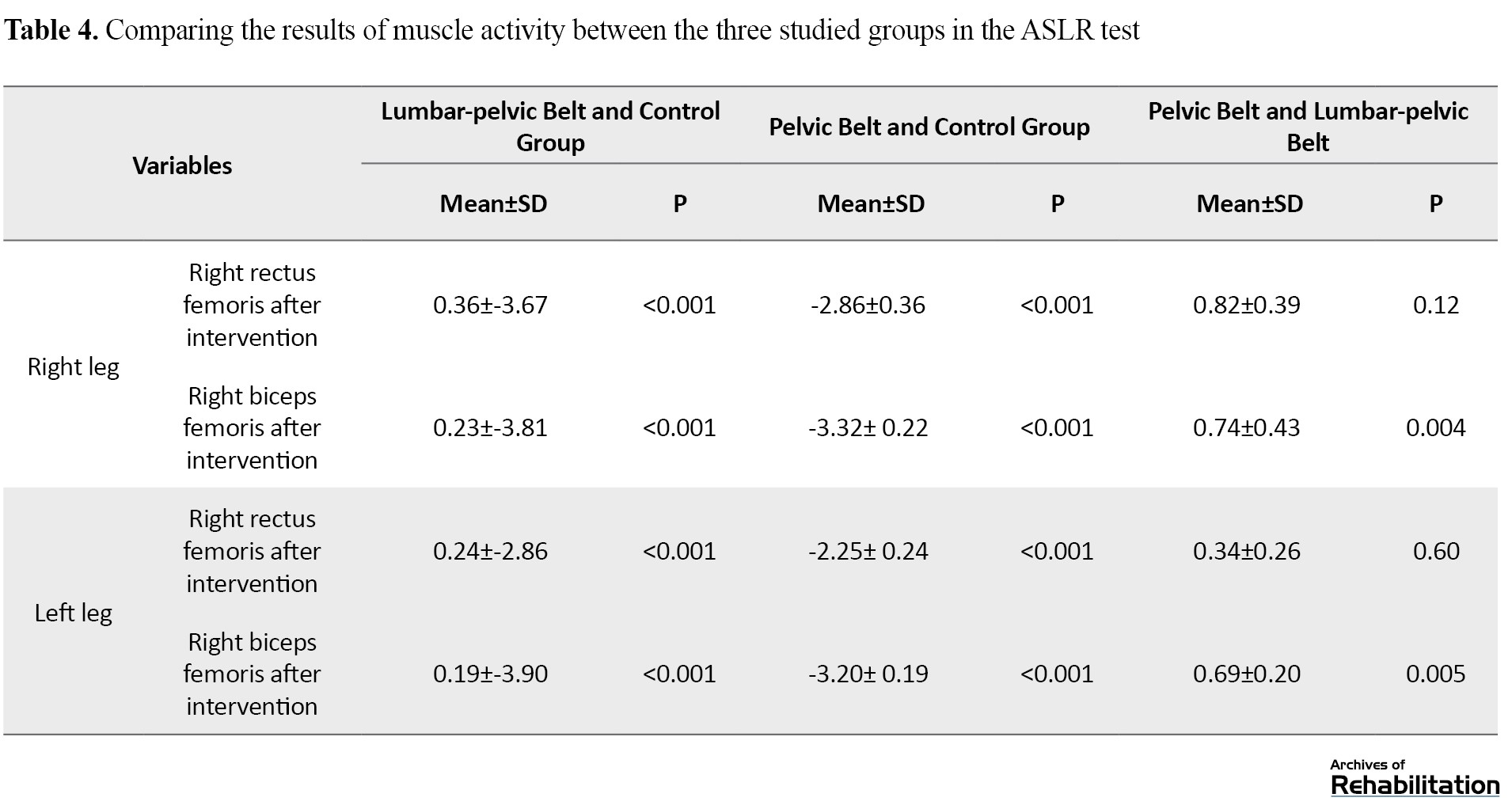

Three weeks after the intervention, the activity of all muscles decreased in both groups using the belt. Although the activity level of the right rectus femoris and left rectus femoris muscles in the lumbar-pelvic belt group decreased more than the pelvic belt group, this decrease was not statistically significant. Still, the activity level of the right biceps femoris and left biceps femoris muscles in the lumbar-pelvic belt group had a statistically significant decrease compared to the pelvic belt group (P<0.001). Comparing the two groups with the control group, a significant difference was observed in all four muscles (P<0.001), and in the control group, the amount of muscle activity increased (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study was conducted to compare the effect of the lumbar-pelvic belt with the pelvic belt on the activity of the pelvic muscles during the ASLR test in pregnant women with back and pelvic pain. The activities of the right rectus femoris, right biceps femoris, left rectus femoris muscles, and left biceps femoris were examined with the ASLR test in three groups of the lumbar-pelvic belt, pelvic belt, and control at the beginning of the study and three weeks after administering the belts. In the control group, the activity level of all muscles increased. The increase in muscle activity in the control group can lead to a rise in anterior forces and bending moments due to the enlargement of the abdomen and the increase in mass in the anterior part of the body of pregnant women. As a result, all posterior lumbar and pelvic muscles act as active stabilizers. To compensate for the increase in anterior forces and bending moment, they increase their activity [8], which could be the reason for the increased activity of the biceps femoris muscle in the control group. With the progress of pregnancy, by the increase in the laxity of the ligaments in the pelvic ring, and the shearing forces caused by the tilt of the pelvis, the force fence of the sacroiliac joint is damaged, and the pelvic pain increases. As a result, the pelvic muscles (especially the anterior pelvic muscles) must be active to provide pelvic stability [9, 10]. Thus, the increased activity of the rectus femoris, an anterior hip muscle, in the current study can be due to this. Also, the lack of use of pregnancy belts in the control group and, as a result, the lack of proper support and coverage in the back and pelvis, which helps distribute weight and reduce pressure on the spine and reduce ligament laxity, led to an increase in muscle activity in this group. This increased muscle activity can be associated with increased pain and disability in the lumbar and pelvic areas. Gutke and Naval also concluded in their studies that muscle dysfunction and increased activity of lumbar and pelvic muscles are associated with lumbar and pelvic pain and should be considered when formulating treatment strategies and preventive measures [12, 31]. Grote’s study showed that pregnant women with lumbar and pelvic pain had higher muscle activity during ASLR, which indicates disturbed load transfer through the sacroiliac joint in this population [9].

In the present study, the comparison between the three groups showed that the activity of all four muscles decreased in both groups that used pelvic and lumbar-pelvic belts for three weeks, which indicates the improvement of the muscle activity of the two groups mentioned in this test. This improvement in muscle activity can be due to belts’ support of the pelvic area. This support leads to the reduction of ligament laxity in the pelvic ring. It prevents the increase of pelvic tilt, and as an external support, it helps the pelvic muscles create and maintain stability in the sacroiliac joint and the appropriate distribution of the forces entering the pelvis, reducing the pain the excessive activity of the pelvic muscles. It is consistent with the studies of Grot, Hu, and Sohiro that showed the positive effect of using pelvic belts during active leg raising in improving performance and reducing pelvic muscle activity [9, 10, 19].

In this study, in the lumbar-pelvic belt group, compared to the pelvic belt group, the activity of all four muscles decreased; however, the decrease in the right rectus femoris and left rectus femoris muscle activities were not statistically significant. Still, the activity level of the right biceps femoris and left biceps femoris in the pelvic-lumbar belt group showed a statistically significant decrease compared to the pelvic belt group. This performance improvement in the lumbar-pelvic belt can be due to the simultaneous support and the same fabric of the lumbar and pelvic area. It provides better support than the pelvic belt in the pelvic area, improves load transfer, and better distributes forces in the spine and pelvic area. It has provided better resistance against bending moments and improved biceps femoris muscle activity.

In the present study, three weeks after the intervention, the activity of the rectus femoris and biceps femoris muscles during ASLR in both groups using the pelvic and lumbar-pelvic belts decreased and increased in the control group. As a result, both pelvic and lumbar-pelvic belts were effective in improving pelvic muscle activity. However, the lumbar-pelvic belt improved the activity of the biceps femoris muscles more than the pelvic belt during the ASLR test.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.161).

Funding

The paper was extracted from PhD thesis of Zhaleh Heydari at Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mohammad Ali Mardani; Methodology: Mohammad Ali Mardani and Akbar Biglarian; Data collection: Zhaleh Heydari, and Gholamreza Aminian; Data analysis: Akbar Biglarian and Zhaleh Heydari; Writing original draft, review & editing: All authors; Funding acquisition and resources: Zhaleh Heydari, Gholamreza Aminian and Maryam Shokrpour.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We hereby express our gratitude to Arak University of Medical Sciences, who helped the study in the stage of taking samples.

References

During pregnancy, the physical and hormonal changes that occur in the body cause skeletal and muscular discomforts and back and pelvic pain [1 ,2, 3 ,4]. During pregnancy, weight gain, belly pushing forward, displacement of the center of mass, increase in forces on the spine and ligament laxity, and as a result, changes in lumbar-pelvic posture and the movement pattern of the lumbar region can lead to skeletal-muscular disorders and increase muscle activity [8].

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction plays a crucial role in pregnancy-related back and pelvic pain [9]. Abdominal and pelvic muscles jointly create sacroiliac joint force barrier and hip flexion [10]. In case of damage to the mechanism of these muscles, the joint has less stability and is more exposed to shearing forces [11]. This condition leads to a change in the activity pattern of the lumbar and pelvic muscles and an increase in muscle activity to compensate for the anterior forces and bending torques caused by increasing the volume of the abdomen and creating a postural adaptation [1, 8, 12].

The active straight leg raise (ASLR) test is a valid and reliable test used to diagnose back and pelvic pain in pregnant women and can show the transfer of disturbed load through the sacroiliac joint in pregnant women with back and pelvic pain [13].

Pelvic belts in pregnancy improve muscle function [14], stabilize the pelvic joint, and reduce pain [15, 16], and by preventing muscle damage and reducing muscle activity and fatigue, they can reduce possible pains [17].

In previous studies, the activity of pelvic muscles in the ASLR test was evaluated in pregnant women without using a pelvic belt [18, 19]. The belts examined in the previous studies included a part around the pelvic ring, which can be slightly wider in the waist area for more support or be limited to the same pelvic ring. They were mostly designed at the level of the pubic symphysis or the upper anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). These orthoses do not fully support the lumbar region. A lumbar-pelvic belt can extend to below the lower angle of the scapula and fully supports the lumbar area and the waist and pelvis simultaneously by transferring movement from the back to the pelvis, compared to a pelvic belt. It can have a better force distribution in the back and pelvis area, and its positive effect has been shown in the improvement of pain and function of the back and pelvis and the quality of life of pregnant women with back and pelvis pain [20, 21]. So far, the lumbar-pelvic belt’s effect on the pelvic muscles’ activity during the ASLR test in pregnant women with back and pelvic pain has not been evaluated. Therefore, the present study aims to compare the effect of the lumbar-pelvic belt with the pelvic belt in the activity of pelvic muscles during the ASLR test in pregnant women with back and pelvic pain.

Materials and Methods

The present research is a clinical trial study (Registration code: IRCT20200925048833N1). The research population included pregnant women with pelvic and back pain related to pregnancy. The sampling method was convenience sampling among pregnant women with pelvic and back pain who had visited the Specialist and Subspecialty Clinic of Kowsar in Arak City, Iran. According to the Gemma study, considering the confidence interval of 95% and the test power of 80%, the variance of 15.16 units and the accuracy of 3.5 units [1], a sample size of 14, 14, 20, respectively, for the control groups, pelvic belt, and lumbar-pelvic belt were obtained. So, 48 pregnant women with back and pelvic pain were included in the study according to the inclusion and exclusion study. Then, they were randomly divided into three groups: pelvic belt, lumbar-pelvic belt, and control.

All participants signed the written consent form and then entered the study. First, all subjects completed the demographic questionnaire. Before the study and three weeks after the intervention, the muscle activity of the pelvic muscles was evaluated with the ASLR test. In the present study, two types of belts were evaluated.

A pelvic belt is a prefabricated belt. It is flexible, soft, and comfortable. It is made of three-dimensional fabric with hypoallergenic fibers and is placed around the pelvis under the upper ACL and lower abdomen.

The second one is the lumbar-pelvic belt, which has four abdominal, lumbar, pelvic, and shoulder straps. In this belt, the pelvic part is connected to the flexible lumbar-sacral orthosis (lumbar region). In addition to being soft and comfortable, it covers a wider area of the woman’s body.

To evaluate the muscle activity of the pelvic muscles during the ASLR test, a muscle electrical activity recording device equipped with 16 channels of the Mayon wireless model (made in Germany) was used.

To collect electromyography (EMG) data, the exact location of the electrodes on the muscles was identified and prepared based on the recommendations of the European Society of Electromyography [27]. The electrodes were placed on the rectus femoris and biceps femoris muscles. In the present study, the average muscle activity was determined based on the average amplitude of the signals. Due to the special conditions of pregnancy and the concerns about using the maximum voluntary isometric contraction test to normalize the data obtained from EMG, the signals of each muscle were normalized to the full activity value of that muscle during the same test [28, 29 ,30]. After refining the data, SPSS software, version 26 was used to analyze the data. A statistically significant level of <0.05 was considered for all tests.

Results

In the present study, 48 pregnant women with back and pelvic pain participated and were randomly divided into three groups: pelvic belt (14 people), lumbar-pelvic belt (14 people), and control group (20 people). Table 1 presents the mean and standard deviation of background variables of pregnant women participating in the study.

To check the normality of the muscle activity variable data, we used the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and the normality of the data was confirmed. The muscle activities of the right and rectus femoris and right and left biceps femoris muscles were assessed with the ASLR test before the study and three weeks after the intervention, and their mean and standard deviation were obtained (Table 2).

The results showed that three weeks after the administration of the belts, the muscle activity of all muscles during the ASLR in the two groups using the belt had a decreasing trend. In the control group, an increase in muscle activity was observed.

Muscle activity in the three studied groups in the ASLR test was analyzed using covariance analysis (Table 3).

The results showed significant differences between the groups in the right rectus femoris, left rectus femoris, right biceps femoris, and left biceps femoris muscles (P<0.001).

Three weeks after the intervention, the activity of all muscles decreased in both groups using the belt. Although the activity level of the right rectus femoris and left rectus femoris muscles in the lumbar-pelvic belt group decreased more than the pelvic belt group, this decrease was not statistically significant. Still, the activity level of the right biceps femoris and left biceps femoris muscles in the lumbar-pelvic belt group had a statistically significant decrease compared to the pelvic belt group (P<0.001). Comparing the two groups with the control group, a significant difference was observed in all four muscles (P<0.001), and in the control group, the amount of muscle activity increased (Table 4).

Discussion

The present study was conducted to compare the effect of the lumbar-pelvic belt with the pelvic belt on the activity of the pelvic muscles during the ASLR test in pregnant women with back and pelvic pain. The activities of the right rectus femoris, right biceps femoris, left rectus femoris muscles, and left biceps femoris were examined with the ASLR test in three groups of the lumbar-pelvic belt, pelvic belt, and control at the beginning of the study and three weeks after administering the belts. In the control group, the activity level of all muscles increased. The increase in muscle activity in the control group can lead to a rise in anterior forces and bending moments due to the enlargement of the abdomen and the increase in mass in the anterior part of the body of pregnant women. As a result, all posterior lumbar and pelvic muscles act as active stabilizers. To compensate for the increase in anterior forces and bending moment, they increase their activity [8], which could be the reason for the increased activity of the biceps femoris muscle in the control group. With the progress of pregnancy, by the increase in the laxity of the ligaments in the pelvic ring, and the shearing forces caused by the tilt of the pelvis, the force fence of the sacroiliac joint is damaged, and the pelvic pain increases. As a result, the pelvic muscles (especially the anterior pelvic muscles) must be active to provide pelvic stability [9, 10]. Thus, the increased activity of the rectus femoris, an anterior hip muscle, in the current study can be due to this. Also, the lack of use of pregnancy belts in the control group and, as a result, the lack of proper support and coverage in the back and pelvis, which helps distribute weight and reduce pressure on the spine and reduce ligament laxity, led to an increase in muscle activity in this group. This increased muscle activity can be associated with increased pain and disability in the lumbar and pelvic areas. Gutke and Naval also concluded in their studies that muscle dysfunction and increased activity of lumbar and pelvic muscles are associated with lumbar and pelvic pain and should be considered when formulating treatment strategies and preventive measures [12, 31]. Grote’s study showed that pregnant women with lumbar and pelvic pain had higher muscle activity during ASLR, which indicates disturbed load transfer through the sacroiliac joint in this population [9].

In the present study, the comparison between the three groups showed that the activity of all four muscles decreased in both groups that used pelvic and lumbar-pelvic belts for three weeks, which indicates the improvement of the muscle activity of the two groups mentioned in this test. This improvement in muscle activity can be due to belts’ support of the pelvic area. This support leads to the reduction of ligament laxity in the pelvic ring. It prevents the increase of pelvic tilt, and as an external support, it helps the pelvic muscles create and maintain stability in the sacroiliac joint and the appropriate distribution of the forces entering the pelvis, reducing the pain the excessive activity of the pelvic muscles. It is consistent with the studies of Grot, Hu, and Sohiro that showed the positive effect of using pelvic belts during active leg raising in improving performance and reducing pelvic muscle activity [9, 10, 19].

In this study, in the lumbar-pelvic belt group, compared to the pelvic belt group, the activity of all four muscles decreased; however, the decrease in the right rectus femoris and left rectus femoris muscle activities were not statistically significant. Still, the activity level of the right biceps femoris and left biceps femoris in the pelvic-lumbar belt group showed a statistically significant decrease compared to the pelvic belt group. This performance improvement in the lumbar-pelvic belt can be due to the simultaneous support and the same fabric of the lumbar and pelvic area. It provides better support than the pelvic belt in the pelvic area, improves load transfer, and better distributes forces in the spine and pelvic area. It has provided better resistance against bending moments and improved biceps femoris muscle activity.

In the present study, three weeks after the intervention, the activity of the rectus femoris and biceps femoris muscles during ASLR in both groups using the pelvic and lumbar-pelvic belts decreased and increased in the control group. As a result, both pelvic and lumbar-pelvic belts were effective in improving pelvic muscle activity. However, the lumbar-pelvic belt improved the activity of the biceps femoris muscles more than the pelvic belt during the ASLR test.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1399.161).

Funding

The paper was extracted from PhD thesis of Zhaleh Heydari at Department of Orthotics and Prosthetics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mohammad Ali Mardani; Methodology: Mohammad Ali Mardani and Akbar Biglarian; Data collection: Zhaleh Heydari, and Gholamreza Aminian; Data analysis: Akbar Biglarian and Zhaleh Heydari; Writing original draft, review & editing: All authors; Funding acquisition and resources: Zhaleh Heydari, Gholamreza Aminian and Maryam Shokrpour.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We hereby express our gratitude to Arak University of Medical Sciences, who helped the study in the stage of taking samples.

References

- Biviá-Roig G, Lisón JF, Sánchez-Zuriaga D. Effects of pregnancy on lumbar motion patterns and muscle responses.The Spine Journal: Official Journal of The North American Spine Society. 2019; 19(2):364-71. [PMID]

- Bastiaanssen JM, de Bie RA, Bastiaenen CH, Essed GG, van den Brandt PA. A historical perspective on pregnancy-related low back and/or pelvic girdle pain. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology. 2005; 120(1):3-14. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.11.021] [PMID]

- Cheng PL, Pantel M, Smith JT, Dumas GA, Leger AB, Plamondon A, et al. Back pain of working pregnant women: Identification of associated occupational factors. Applied Ergonomics. 2009; 40(3):419-23. [DOI:10.1016/j.apergo.2008.11.002] [PMID]

- Gutke A, Boissonnault J, Brook G, Stuge B. The severity and impact of pelvic girdle pain and low-back pain in pregnancy: A multinational study. Journal of Women's Health. 2018; 27(4):510-7. [DOI:10.1089/jwh.2017.6342] [PMID]

- Kluge J, Hall D, Louw Q, Theron G, Grové D. Specific exercises to treat pregnancy-related low back pain in a South African population. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of The International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2011; 113(3):187-91. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.10.030] [PMID]

- Kaplan Ş, Alpayci M, Karaman E, Çetin O, Özkan Y, İlter S, et al. Short-term effects of Kinesio Taping in women with pregnancy-related low back pain: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Medical Science Monitor. 2016; 22:1297–301. [DOI:10.12659/MSM.898353] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Vleeming A, Albert HB, Ostgaard HC, Sturesson B, Stuge B. European guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pelvic girdle pain. European Spine Journal. 2008; 17(6):794-819. [DOI:10.1007/s00586-008-0602-4] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Biviá-Roig G, Lisón JF, Sánchez-Zuriaga D. Changes in trunk posture and muscle responses in standing during pregnancy and postpartum. PLoS One. 2018; 13(3):e0194853. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0194853] [PMID] [PMCID]

- de Groot M, Pool-Goudzwaard AL, Spoor CW, Snijders CJ. The active straight leg raising test (ASLR) in pregnant women: Differences in muscle activity and force between patients and healthy subjects. Manual Therapy. 2008; 13(1):68-74. [DOI:10.1016/j.math.2006.08.006] [PMID]

- Buijs EJ, Kamphuis ET, Groen GJ. Radiofrequency treatment of sacroiliac joint-related pain aimed at the first three sacral dorsal rami: A minimal approach. The Pain Clinic. 2004; 16(2):139-46. [Link]

- Vleeming A, Volkers AC, Snijders CJ, Stoeckart R. Relation between form and function in the sacroiliac joint. Part II: Biomechanical aspects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990; 15(2):133-6. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-199002000-00017] [PMID]

- Nawal TTL, Mansourou LM, Lafiou Y, Geneviève D. Implication of back extensor muscles in the appearance of back pain in 30 beninese pregnant women. American Journal of Biomedical and Life Sciences. 2017; 5(6):119-22. [DOI:10.11648/j.ajbls.20170506.12]

- Mens JM, Vleeming A, Snijders CJ, Koes BW, Stam HJ. Reliability and validity of the active straight leg raise test in posterior pelvic pain since pregnancy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001; 26(10):1167-71. [DOI:10.1097/00007632-200105150-00015] [PMID]

- Liddle SD, Pennick V. Interventions for preventing and treating low-back and pelvic pain during pregnancy. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015; 2015(9):CD001139. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Oh JS. Effects of pelvic belt on hip extensor muscle EMG activity during prone hip extension in females with chronic low back pain. Journal of Physical Therapy Science. 2014; 26(7):1023-4. [DOI:10.1589/jpts.26.1023] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bertuit J, Van Lint CE, Rooze M, Feipel V. Pregnancy and pelvic girdle pain: Analysis of pelvic belt on pain. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018; 27(1-2):e129-37. [DOI:10.1111/jocn.13888] [PMID]

- Kang X, Ying BA, Zhang X, Qi J, Wu L. Force analysis of the support belt and pregnant woman for relieving the pregnancy-related waist pain. Journal of Fiber Bioengineering and Informatics. 2018; 11(4):217-26. [DOI:10.3993/jfbim00302]

- Hu H, Meijer OG, van Dieën JH, Hodges PW, Bruijn SM, Strijers RL, et al. Muscle activity during the active straight leg raise (ASLR), and the effects of a pelvic belt on the ASLR and on treadmill walking. Journal of Biomechanics. 2010; 43(3):532-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.035] [PMID]

- Suehiro T, Yakushijin Y, Nuibe A, Ishii S, Kurozumi C, Ishida H. Effect of pelvic belt on the perception of difficulty and muscle activity during active straight leg raising test in pain-free subjects. Journal of Exercise Rehabilitation. 2019; 15(3):449-53. [DOI:10.12965/jer.1938140.070] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Heydari Z, Aminian G, Biglarian A, Shokrpour M, Mardani MA. Comparison of the modified lumbar pelvic belt with the current belt on low back and pelvic pain in pregnant women. Journal of Biomedical Physics & Engineering. 2022; 12(3):309–18. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Heydari Z, Mardani MA, Biglarian A, Shokrpour M, Aminian G. Evaluation of the quality of life of pregnant women with lumbar pain using the new pregnancy belt and compare to the current belt. Journal of Rehabilitation Sciences & Research. 2022. [Link]

- Cameron L, Marsden J, Watkins K, Freeman J. Management of antenatal pelvic-girdle pain study (MAPS): A double blinded, randomised trial evaluating the effectiveness of two pelvic orthoses. International Journal of Women’s Health Care. 2018; 3(2):1-9. [DOI:10.33140/IJWHC.03.02.09]

- Kordi R, Abolhasani M, Rostami M, Hantoushzadeh S, Mansournia MA, Vasheghani-Farahani F. Comparison between the effect of lumbopelvic belt and home based pelvic stabilizing exercise on pregnant women with pelvic girdle pain; a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2013; 26(2):133-9. [DOI:10.3233/BMR-2012-00357] [PMID]

- Sehmbi H, D’Souza R, Bhatia A. Low back pain in pregnancy: Investigations, management, and role of neuraxial analgesia and anaesthesia: A systematic review. Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation. 2017; 82(5):417-36. [PMID]

- Depledge J, McNair PJ, Keal-Smith C, Williams M. Management of symphysis pubis dysfunction during pregnancy using exercise and pelvic support belts. Physical Therapy. 2005; 85(12):1290-300. [DOI:10.1093/ptj/85.12.1290] [PMID]

- Flack NA, Hay-Smith EJ, Stringer MD, Gray AR, Woodley SJ. Adherence, tolerance and effectiveness of two different pelvic support belts as a treatment for pregnancy-related symphyseal pain - a pilot randomized trial. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2015; 15:36. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hermens HJ, Freriks B, Disselhorst-Klug C, Rau G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 2000; 10(5):361-74. [DOI:10.1016/S1050-6411(00)00027-4] [PMID]

- Bagwell JJ, Reynolds N, Walaszek M, Runez H, Lam K, Armour Smith J, et al. Lower extremity kinetics and muscle activation during gait are significantly different during and after pregnancy compared to nulliparous females. Gait & Posture. 2020; 81:33-40. [DOI:10.1016/j.gaitpost.2020.07.002] [PMID]

- Choi Y, Kim Y, Kim M, Yoon B. Muscle synergies for turning during human walking. Journal of Motor Behavior. 2019; 51(1):1-9. [DOI:10.1080/00222895.2017.1408558] [PMID]

- Santuz A, Ekizos A, Janshen L, Mersmann F, Bohm S, Baltzopoulos V, et al. Modular control of human movement during running: An open access data set. Frontiers in Physiology. 2018; 9:1509. [DOI:10.3389/fphys.2018.01509] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Gutke A, Östgaard HC, Öberg B. Association between muscle function and low back pain in relation to pregnancy. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2008; 40(4):304-11. [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Orthotics & Prosthetics

Received: 15/11/2022 | Accepted: 7/12/2022 | Published: 1/05/2023

Received: 15/11/2022 | Accepted: 7/12/2022 | Published: 1/05/2023

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |