Volume 24, Issue 1 (Spring 2023)

jrehab 2023, 24(1): 28-41 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Khademhamzehei E, Mortazavi Z, Najafivosough R, Haghgoo H A, Mortazavi S S. The Post-traumatic Stress Disorder in COVID-19 Recovered Patients: A Cross-sectional Study. jrehab 2023; 24 (1) :28-41

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3189-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3189-en.html

Elham Khademhamzehei1

, Zahra Mortazavi2

, Zahra Mortazavi2

, Roya Najafivosough3

, Roya Najafivosough3

, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo4

, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo4

, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi *5

, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi *5

, Zahra Mortazavi2

, Zahra Mortazavi2

, Roya Najafivosough3

, Roya Najafivosough3

, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo4

, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo4

, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi *5

, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi *5

1- Student Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

4- Department of Occupational Therapy, Hearing Disorders Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

5- Department of Occupational Therapy, Hearing Disorders Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran. ,s.mortazavi.ot@gmail.com

2- Department of Speech Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

3- Department of Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

4- Department of Occupational Therapy, Hearing Disorders Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran.

5- Department of Occupational Therapy, Hearing Disorders Research Center, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences, Hamadan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 1305 kb]

(1594 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4953 Views)

Full-Text: (2539 Views)

Introduction

The COVID-19 disease is caused by a new and genetically modified virus called SARS-CoV-2 and was officially named by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. The virus spread to all world countries in less than 4 months [2, 3]. According to official reports, 584935393 people worldwide and 7236361 people in Iran were infected with this virus until December 5, 2022, and 7061727 people recovered [4]. The outbreak of the disease and the sudden quarantine of the community, with a great impact on life, created concerns about mental health in the general public [5]. The increase in the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in those who have recovered from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and COVID-19 has been widely reported [6]. PTSD is one of the fundamental public health concerns, and the rate of exposure to at least one traumatic event in life is estimated at 50%-65% [7]. This disorder is the fourth most common psychiatric diagnosis, affecting 10% of men and 18% of women [8]. In PTSD, a person is exposed to a severely damaging event, the severity of which will be harmful to any other person [9]. Harmful events may be trauma, floods, earthquakes, rape, war, and similar cases [10]. This disorder is prevalent in groups of patients with hospitalization experience, including patients in intensive care units (ICUs) who had intubation, mechanical ventilation, and delusions [6]. The duration of symptoms varies in different people, this period can be as short as a week [10], but it mainly occurs in the first two years after the accident [11]. In a study by the WHO in 13 countries on 23936 people who experienced exposure to trauma, 6.6% of the participants showed clinical evidence of PTSD [12].

Scientific evidence shows that PTSD is common in people recovering from COVID-19, and factors, including obesity, diabetes, and heart disease in black men and asthma in black women [13], high blood pressure and obesity in veterans [14], having a history of depression and anxiety [15], pneumonia and lung lobe involvement, and higher levels of urea [16] and a history of cancer [17]increase the probability of this disorder.

Because little time has passed since the epidemic of COVID-19 disease and there is a lot of uncertainty about the health and consequences of COVID-19, the patients who recovered from this disease in different communities have a high prevalence of PTSD. Also, cases of severe PTSD have been reported in similar diseases, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome epidemic (MERS), because the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to lead to early and delayed mental health problems and COVID-19 recoveries will live under the shadow of past trauma for a long time [18, 19, 20] and also despite the limited scientific evidence in the field of PTSD. Regarding the tragedy in the recovery from COVID-19 in different Iranian communities [21, 22, 23], the present study was designed to investigate PTSD in the patients who recovered from COVID-19 in Hamadan City, Iran.

Materials and Methods

The present study is a cross-sectional study conducted to investigate the level of post-traumatic stress in those who recovered from COVID-19 in Hamadan City, Iran. After the approval of the Ethics Committee, data collection started on November 30, 2021, and ended on February 30, 2022.

People who recovered from COVID-19 were eligible to participate in the study. Sampling was done by simple random method. The inclusion criteria included being over 14 years old, confirmation of the diagnosis of COVID-19 disease by the health department of the university, a time interval of at least one month and at most three months from the time of infection, no diagnosis of cognitive impairment that prevents the completion of the questionnaire (mini-mental state examination [MMSE]>23), having reading and writing literacy, and the ability to use a mobile phone by the patient himself or his main caregiver. The patient’s informed consent to participate in the study and the conditions for withdrawing from the study included receiving psychiatric and psychological treatments, diagnosis of PTSD before the person was infected with COVID-19, and willingness to withdraw.

According to previous studies [24], the required number of samples was calculated to be 185 people, considering the type I error of 5% and the test power of 90%.

The tools used in this research included the demographic profile form and the Mississippi scale. Demographic characteristics included age, gender, height, weight, occupation, marital status, education, hospitalization due to coronavirus, number of days in the ward, and number of days in the ICU.

The Mississippi scale is a self-report scale consisting of 35 items. It measures the items from never with a score of 1 to always with a score of 5. In the research of Boks et al., the correlation of the questions of this scale with the self-assessment list for PTSD was 0.82, which indicates its high validity [25]. Also, in the study of Huang and Kashubek-West, the correlation between the scale to measure PTSD and the PTSD checklist was 0.90 [26]. The minimum score is 35, and the maximum is 175. A score higher than 107 indicates the presence of PTSD. The Cronbach α coefficient of this questionnaire was 0.86-0.94 [27]. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the PTSD scale were reported by Sadeghi et al. (r=0.68, P=0.001). Also, the Cronbach α and retest reliability coefficients for the whole scale and its dimensions have been reported above 0.70 [28]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaires using the Cronbach α was 0.729. The approximate time to complete the questionnaires was between 15 and 20 minutes.

Data analysis

After entering data into SPSS software, version 24, descriptive statistics (prevalence, relative frequency, Mean±SD) were used to describe the collected information. After checking the data distribution normality, each basic variable’s relationship with PTSD was studied using appropriate statistical tests, including the Mann-Whitney test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Pearson correlation coefficients.

Results

In general, 185 people who recovered from COVID-19, over 14 years old and with an average age of 38.43±14.07 years participated in the study, and 117 of the participants (63.2%) were women, 122(65.9%) were married, most of them were housewives, unemployed (35.6%), had a bachelor’s degree (44%), 43 people (23.2%) of this group were hospitalized, and 142 people (76.8%) were hospitalized at home. People were hospitalized between 2 and 28 days, with an Mean±SD of 6.41±4.15 days in the ward, and between 1 and 11 days, with an mean of 4.09±3.61 days in the ICU.

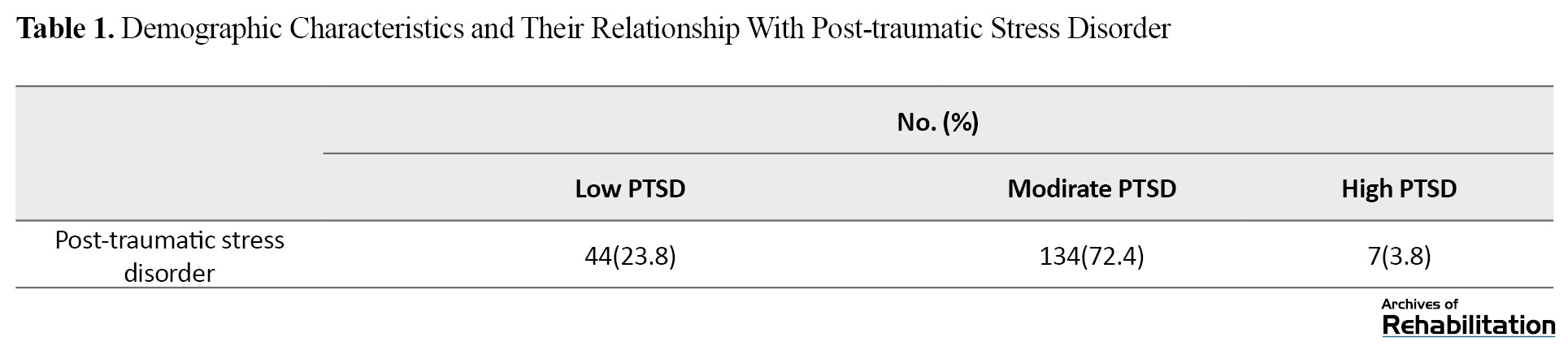

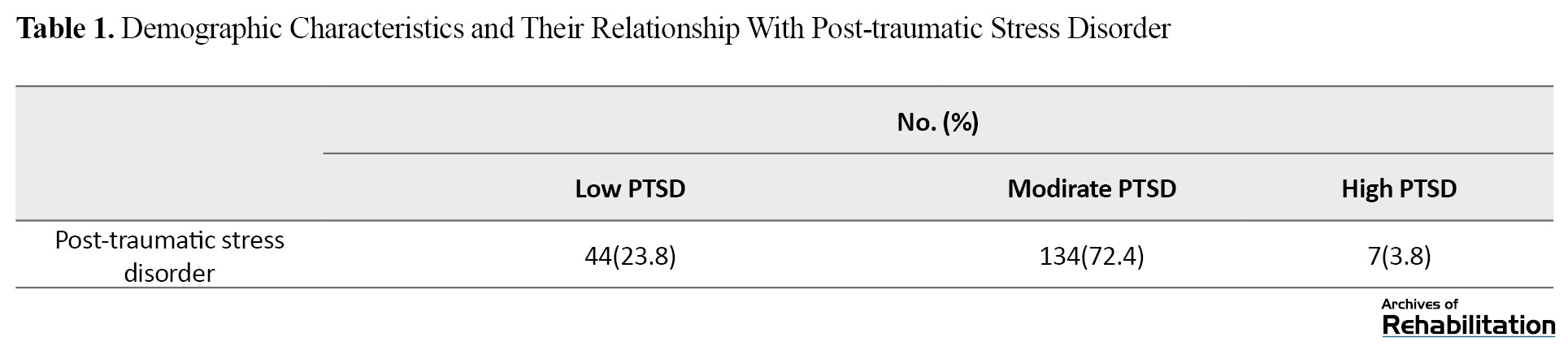

Because of the non-normal distribution of stress disorder in at least one of the levels of gender, marital status, and hospitalization due to COVID-19, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to investigate the relationship between these variables and PTSD. The results of this test showed a significant relationship between PTSD and gender. PTSD in women (63.2%) was more than in men (63.8%), but there was no significant relationship between PTSD and marital status and hospitalization due to COVID-19. Also, due to the non-normal distribution of stress disorder in at least one of the job and education levels, to investigate the relationship between these two variables with PTSD, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. This test showed a significant relationship between PTSD and job, but no significant relationship was observed between PTSD and education. Also, the Pearson correlation test results showed a significant relationship between PTSD and age, height, and weight in people who have recovered from COVID-19 (Table 1).

The Mean±SD PTSD score in people who recovered from COVID-19 was 80.37±17.37, which means that the severity of PTSD symptoms is moderate. Among them, 23.8% had low PTSD, 72.4% had moderate PTSD, and 3.8% had high PTSD.

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that three-quarters of people who have recovered from COVID-19 have PTSD symptoms. In line with the results of studies in patients who recovered from COVID-19 in Tehran City, Iran, 6 weeks after discharge, 58% of participants reported at least one persistent symptom. These symptoms were 15% of anxiety cases [21], 3.8% of PTSD, 5.8% of anxiety, and 5% of depression [23]. In other studies, neurological and psychological symptoms after recovery from COVID-19 have been confirmed [29]. Symptoms of depression disorder, sleep disorder, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress are also symptoms of post-ICU syndrome in patients [30]. In justifying the causes of this finding, the fear of the consequences of COVID-19 and the limitation of social communication may cause psychological disorders [31].

Also, the current study showed that PTSD is more common in women who have recovered from COVID-19. In line with the present study, studies in the epidemic of COVID-19 [24], in the epidemic of Influenza A virus subtype (H1N1) [32], and also in those who recovered from SARS [33] showed that women are susceptible to suffering from higher levels of PTSD. Some studies reported different results. In a study of 1257 health workers and medical services affected by the SARS virus [34] and residents in the war zone [35], an increase in the probability of suffering from post-traumatic stress was reported more in men than women. In the explanation of the present study, it is noteworthy that women experience higher levels of potential risk factors such as depression, sensitivity to physical anxiety, and helplessness [36].

Also, the percentage of PTSD in those who recovered from COVID-19 with a bachelor’s education was more than in other degrees. In other studies, different results have been reported. In a study of people aged 14 to 35 years in China [37] and a study of the general population during the SARS virus epidemic in Taiwan, people with lower education were more likely to have PTSD and mental distress than people with higher education [38]. In another study on the prevalence of post-traumatic stress in the Chinese population during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was emphasized that education has no significant relationship with post-traumatic stress [24]. One of the possible reasons for the difference in the different results is probably because everyone was placed in home quarantine as soon as the disease worsened, so almost everyone received information about the epidemic, which may reduce the effect of educational background on PTSD symptoms [24].

In the present study, there is a significant relationship between occupation and PTSD, and the housewife and non-working group show the highest severity of PTSD. Various studies investigated PTSD in different occupational groups. In the study of mental health one year after the 2006 war in southern Lebanon, the researchers reported cases such as PTSD and depression in a civilian population and the highest rate of PTSD (26.2%) among homemakers [39]. In the epidemic of COVID-19 disease, non-working people and homemakers exposed themselves more to the onslaught of media information, and the concern about the presence of other family members outside the home as necessary and their possible exposure to the virus has intensified the stress situation.

Age, height, and weight were also considered significant variables in predicting post-traumatic stress in the study group. Studies by Halpin et al. (2021) showed that 80% of patients admitted to the ICU who reported PTSD symptoms were obese [40]. Other studies also confirmed the relationship between obesity and PTSD [13, 14] and considered younger age a protective factor in PTSD [23].

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that three-quarters of people who recovered from COVID-19 had PTSD symptoms, and these symptoms were more severe in obese and elderly women. Therefore, it seems that designing and providing support and educational services to those who have recovered from COVID-19 can effectively prevent and manage this disorder and improve their performance.

One of the most important limitations of the current research is not using a tool to remove duplicates. However, it was ensured that multiple responses were not registered through the same IPs. Because people were infected suddenly, the absence of post-traumatic stress before contracting COVID-19 in the studied subjects was recorded only based on the samples’ self-reports, and the researchers could not control it ideally. The study was conducted at a point in time with a self-report instrument and without a comparison group, and caution should be exercised in generalizing the results. One of the strong points of the study is the collection of samples from the approved list of Hamedan University of Medical Sciences Vice-Chancellor of Health, which was confirmed to be infected with COVID-19 by PCR and nasal and pharyngeal swab tests, but because of the coronavirus strain and ethnic and cultural variables and healthy people without experience of getting infected with covid were not investigated in the comparison group and there is no analysis based on these cases, so it is suggested to be considered in future studies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences with ID IR.UMSHA.REC.1400.645. To comply with ethical considerations in the present study, completing the questionnaires and participating in the study was voluntary, and consent was obtained from all participants. Personal information remained confidential. The result of the research was informed to the subjects if they wanted to know it.

Funding

This article is the result of a research project approved by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (No.: 140008257020) and was done with the financial support of the Student Research Center.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Elham Khadem Hamzeii, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi; Methodology: Roya Najafivosough, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi; Analysis, research, and investigation: Elham Khadem Hamzeii, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi, Roya Najafivosough; Edited and finalized: Saideh Sadat Mortazavi, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo.

Conflict of interest

All authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all patients who helped us in the implementation of this research.

The COVID-19 disease is caused by a new and genetically modified virus called SARS-CoV-2 and was officially named by the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. The virus spread to all world countries in less than 4 months [2, 3]. According to official reports, 584935393 people worldwide and 7236361 people in Iran were infected with this virus until December 5, 2022, and 7061727 people recovered [4]. The outbreak of the disease and the sudden quarantine of the community, with a great impact on life, created concerns about mental health in the general public [5]. The increase in the risk of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in those who have recovered from severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and COVID-19 has been widely reported [6]. PTSD is one of the fundamental public health concerns, and the rate of exposure to at least one traumatic event in life is estimated at 50%-65% [7]. This disorder is the fourth most common psychiatric diagnosis, affecting 10% of men and 18% of women [8]. In PTSD, a person is exposed to a severely damaging event, the severity of which will be harmful to any other person [9]. Harmful events may be trauma, floods, earthquakes, rape, war, and similar cases [10]. This disorder is prevalent in groups of patients with hospitalization experience, including patients in intensive care units (ICUs) who had intubation, mechanical ventilation, and delusions [6]. The duration of symptoms varies in different people, this period can be as short as a week [10], but it mainly occurs in the first two years after the accident [11]. In a study by the WHO in 13 countries on 23936 people who experienced exposure to trauma, 6.6% of the participants showed clinical evidence of PTSD [12].

Scientific evidence shows that PTSD is common in people recovering from COVID-19, and factors, including obesity, diabetes, and heart disease in black men and asthma in black women [13], high blood pressure and obesity in veterans [14], having a history of depression and anxiety [15], pneumonia and lung lobe involvement, and higher levels of urea [16] and a history of cancer [17]increase the probability of this disorder.

Because little time has passed since the epidemic of COVID-19 disease and there is a lot of uncertainty about the health and consequences of COVID-19, the patients who recovered from this disease in different communities have a high prevalence of PTSD. Also, cases of severe PTSD have been reported in similar diseases, including severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome epidemic (MERS), because the COVID-19 pandemic is expected to lead to early and delayed mental health problems and COVID-19 recoveries will live under the shadow of past trauma for a long time [18, 19, 20] and also despite the limited scientific evidence in the field of PTSD. Regarding the tragedy in the recovery from COVID-19 in different Iranian communities [21, 22, 23], the present study was designed to investigate PTSD in the patients who recovered from COVID-19 in Hamadan City, Iran.

Materials and Methods

The present study is a cross-sectional study conducted to investigate the level of post-traumatic stress in those who recovered from COVID-19 in Hamadan City, Iran. After the approval of the Ethics Committee, data collection started on November 30, 2021, and ended on February 30, 2022.

People who recovered from COVID-19 were eligible to participate in the study. Sampling was done by simple random method. The inclusion criteria included being over 14 years old, confirmation of the diagnosis of COVID-19 disease by the health department of the university, a time interval of at least one month and at most three months from the time of infection, no diagnosis of cognitive impairment that prevents the completion of the questionnaire (mini-mental state examination [MMSE]>23), having reading and writing literacy, and the ability to use a mobile phone by the patient himself or his main caregiver. The patient’s informed consent to participate in the study and the conditions for withdrawing from the study included receiving psychiatric and psychological treatments, diagnosis of PTSD before the person was infected with COVID-19, and willingness to withdraw.

According to previous studies [24], the required number of samples was calculated to be 185 people, considering the type I error of 5% and the test power of 90%.

The tools used in this research included the demographic profile form and the Mississippi scale. Demographic characteristics included age, gender, height, weight, occupation, marital status, education, hospitalization due to coronavirus, number of days in the ward, and number of days in the ICU.

The Mississippi scale is a self-report scale consisting of 35 items. It measures the items from never with a score of 1 to always with a score of 5. In the research of Boks et al., the correlation of the questions of this scale with the self-assessment list for PTSD was 0.82, which indicates its high validity [25]. Also, in the study of Huang and Kashubek-West, the correlation between the scale to measure PTSD and the PTSD checklist was 0.90 [26]. The minimum score is 35, and the maximum is 175. A score higher than 107 indicates the presence of PTSD. The Cronbach α coefficient of this questionnaire was 0.86-0.94 [27]. The validity and reliability of the Persian version of the PTSD scale were reported by Sadeghi et al. (r=0.68, P=0.001). Also, the Cronbach α and retest reliability coefficients for the whole scale and its dimensions have been reported above 0.70 [28]. In the present study, the reliability of the questionnaires using the Cronbach α was 0.729. The approximate time to complete the questionnaires was between 15 and 20 minutes.

Data analysis

After entering data into SPSS software, version 24, descriptive statistics (prevalence, relative frequency, Mean±SD) were used to describe the collected information. After checking the data distribution normality, each basic variable’s relationship with PTSD was studied using appropriate statistical tests, including the Mann-Whitney test, Kruskal-Wallis test, and Pearson correlation coefficients.

Results

In general, 185 people who recovered from COVID-19, over 14 years old and with an average age of 38.43±14.07 years participated in the study, and 117 of the participants (63.2%) were women, 122(65.9%) were married, most of them were housewives, unemployed (35.6%), had a bachelor’s degree (44%), 43 people (23.2%) of this group were hospitalized, and 142 people (76.8%) were hospitalized at home. People were hospitalized between 2 and 28 days, with an Mean±SD of 6.41±4.15 days in the ward, and between 1 and 11 days, with an mean of 4.09±3.61 days in the ICU.

Because of the non-normal distribution of stress disorder in at least one of the levels of gender, marital status, and hospitalization due to COVID-19, the Mann-Whitney U test was used to investigate the relationship between these variables and PTSD. The results of this test showed a significant relationship between PTSD and gender. PTSD in women (63.2%) was more than in men (63.8%), but there was no significant relationship between PTSD and marital status and hospitalization due to COVID-19. Also, due to the non-normal distribution of stress disorder in at least one of the job and education levels, to investigate the relationship between these two variables with PTSD, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. This test showed a significant relationship between PTSD and job, but no significant relationship was observed between PTSD and education. Also, the Pearson correlation test results showed a significant relationship between PTSD and age, height, and weight in people who have recovered from COVID-19 (Table 1).

The Mean±SD PTSD score in people who recovered from COVID-19 was 80.37±17.37, which means that the severity of PTSD symptoms is moderate. Among them, 23.8% had low PTSD, 72.4% had moderate PTSD, and 3.8% had high PTSD.

Discussion

The results of the present study indicate that three-quarters of people who have recovered from COVID-19 have PTSD symptoms. In line with the results of studies in patients who recovered from COVID-19 in Tehran City, Iran, 6 weeks after discharge, 58% of participants reported at least one persistent symptom. These symptoms were 15% of anxiety cases [21], 3.8% of PTSD, 5.8% of anxiety, and 5% of depression [23]. In other studies, neurological and psychological symptoms after recovery from COVID-19 have been confirmed [29]. Symptoms of depression disorder, sleep disorder, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress are also symptoms of post-ICU syndrome in patients [30]. In justifying the causes of this finding, the fear of the consequences of COVID-19 and the limitation of social communication may cause psychological disorders [31].

Also, the current study showed that PTSD is more common in women who have recovered from COVID-19. In line with the present study, studies in the epidemic of COVID-19 [24], in the epidemic of Influenza A virus subtype (H1N1) [32], and also in those who recovered from SARS [33] showed that women are susceptible to suffering from higher levels of PTSD. Some studies reported different results. In a study of 1257 health workers and medical services affected by the SARS virus [34] and residents in the war zone [35], an increase in the probability of suffering from post-traumatic stress was reported more in men than women. In the explanation of the present study, it is noteworthy that women experience higher levels of potential risk factors such as depression, sensitivity to physical anxiety, and helplessness [36].

Also, the percentage of PTSD in those who recovered from COVID-19 with a bachelor’s education was more than in other degrees. In other studies, different results have been reported. In a study of people aged 14 to 35 years in China [37] and a study of the general population during the SARS virus epidemic in Taiwan, people with lower education were more likely to have PTSD and mental distress than people with higher education [38]. In another study on the prevalence of post-traumatic stress in the Chinese population during the COVID-19 pandemic, it was emphasized that education has no significant relationship with post-traumatic stress [24]. One of the possible reasons for the difference in the different results is probably because everyone was placed in home quarantine as soon as the disease worsened, so almost everyone received information about the epidemic, which may reduce the effect of educational background on PTSD symptoms [24].

In the present study, there is a significant relationship between occupation and PTSD, and the housewife and non-working group show the highest severity of PTSD. Various studies investigated PTSD in different occupational groups. In the study of mental health one year after the 2006 war in southern Lebanon, the researchers reported cases such as PTSD and depression in a civilian population and the highest rate of PTSD (26.2%) among homemakers [39]. In the epidemic of COVID-19 disease, non-working people and homemakers exposed themselves more to the onslaught of media information, and the concern about the presence of other family members outside the home as necessary and their possible exposure to the virus has intensified the stress situation.

Age, height, and weight were also considered significant variables in predicting post-traumatic stress in the study group. Studies by Halpin et al. (2021) showed that 80% of patients admitted to the ICU who reported PTSD symptoms were obese [40]. Other studies also confirmed the relationship between obesity and PTSD [13, 14] and considered younger age a protective factor in PTSD [23].

Conclusion

The results of this study showed that three-quarters of people who recovered from COVID-19 had PTSD symptoms, and these symptoms were more severe in obese and elderly women. Therefore, it seems that designing and providing support and educational services to those who have recovered from COVID-19 can effectively prevent and manage this disorder and improve their performance.

One of the most important limitations of the current research is not using a tool to remove duplicates. However, it was ensured that multiple responses were not registered through the same IPs. Because people were infected suddenly, the absence of post-traumatic stress before contracting COVID-19 in the studied subjects was recorded only based on the samples’ self-reports, and the researchers could not control it ideally. The study was conducted at a point in time with a self-report instrument and without a comparison group, and caution should be exercised in generalizing the results. One of the strong points of the study is the collection of samples from the approved list of Hamedan University of Medical Sciences Vice-Chancellor of Health, which was confirmed to be infected with COVID-19 by PCR and nasal and pharyngeal swab tests, but because of the coronavirus strain and ethnic and cultural variables and healthy people without experience of getting infected with covid were not investigated in the comparison group and there is no analysis based on these cases, so it is suggested to be considered in future studies.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This research was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences with ID IR.UMSHA.REC.1400.645. To comply with ethical considerations in the present study, completing the questionnaires and participating in the study was voluntary, and consent was obtained from all participants. Personal information remained confidential. The result of the research was informed to the subjects if they wanted to know it.

Funding

This article is the result of a research project approved by Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (No.: 140008257020) and was done with the financial support of the Student Research Center.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Elham Khadem Hamzeii, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi; Methodology: Roya Najafivosough, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi; Analysis, research, and investigation: Elham Khadem Hamzeii, Saideh Sadat Mortazavi, Roya Najafivosough; Edited and finalized: Saideh Sadat Mortazavi, Hojjat Allah Haghgoo.

Conflict of interest

All authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to all patients who helped us in the implementation of this research.

References

- Wu J, Li J, Zhu G, Zhang Y, Bi Z, Yu Y, et al. Clinical features of maintenance hemodialysis patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 2020; 15(8):1139-45. [DOI:10.2215/CJN.04160320] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zangrillo A, Beretta L, Silvani P, Colombo S, Scandroglio AM, Dell’Acqua A, et al. Fast reshaping of intensive care unit facilities in a large metropolitan hospital in Milan, Italy: Facing the covid-19 pandemic emergency. Critical Care and Resuscitation. 2020; 22(2):91-4. [DOI:10.51893/2020.2.pov1] [PMID]

- Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. Covid-19 and Italy: What next? The lancet. 2020; 395(10231):1225-8. [DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9] [PMID]

- Gupta R, Grover S, Basu A, Krishnan V, Tripathi A, Subramanyam A, et al. Changes in sleep pattern and sleep quality during covid-19 lockdown. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020; 62(4):370-8. [DOI:10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_523_20] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Bonsaksen T, Heir T, Schou-Bredal I, Ekeberg Ø, Skogstad L, Grimholt TK. Post-traumatic stress disorder and associated factors during the early stage of the covid-19 pandemic in Norway. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(24):9210. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17249210] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kaseda ET, Levine AJ. Post-traumatic stress disorder: A differential diagnostic consideration for covid-19 survivors. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 2020; 34(7-8):1498-514. [DOI:10.1080/13854046.2020.1811894] [PMID]

- Sheldon T. Psychological intervention including emotional freedom techniques for an adult with motor vehicle accident related posttraumatic stress disorder: A case study. Current Research in Psychology. 2014; 5(1):40-63. [DOI:10.3844/crpsp.2014.40.63]

- Nagpal M, Gleichauf K, Ginsberg J. Meta-analysis of heart rate variability as a psychophysiological indicator of posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Trauma & Treatment. 2013; 3(1):1000182. [DOI:10.4172/2167-1222.1000182]

- St Cyr K, McIntyre-Smith A, Contractor AA, Elhai JD, Richardson JD. Somatic symptoms and health-related quality of life among treatment-seeking Canadian forces personnel with PTSD. Psychiatry Research. 2014; 218(1-2):148-52. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2014.03.038] [PMID]

- Hojjati H, Ebadi A, Akhoondzadeh G, Sirati M, Heravi M, Nohi E. [Sleep quality in spouses of war veterans with post-traumatic stress: A qualitative study (Persian)]. Military Caring Sciences Journal. 2017; 4(1):1-9. [DOI:10.29252/mcs.4.1.1]

- Mandani B, Rostami H, Hosseini MS. [Comparison of the health related quality of life in out-patient and in-patient war veterans with post traumatic stress disorder (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of War and Public Health. 2012; 4(4):35-42. [Link]

- Williamson JB, Porges EC, Lamb DG, Porges SW. Maladaptive autonomic regulation in PTSD accelerates physiological aging. Frontiers in Psychology. 2015; 5:1571. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01571] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Archibald P, Thorpe R. Chronic medical conditions as predictors of the likelihood of PTSD among black adults: Preparing for the aftermath of covid-19. Health & Social Work. 2021; 46(4):268-76. [DOI:10.1093/hsw/hlab025] [PMID]

- Haderlein TP, Wong MS, Yuan A, Llorente MD, Washington DL. Association of PTSD with covid-19 testing and infection in the veterans health administration. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2021; 143:504-7. [DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.11.033] [PMID] [PMCID]

- De Lorenzo R, Conte C, Lanzani C, Benedetti F, Roveri L, Mazza MG, et al. Residual clinical damage after covid-19: A retrospective and prospective observational cohort study. Plos One. 2020; 15(10):e0239570. [DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0239570] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mei Z, Wu X, Zhang X, Zheng X, Li W, Fan R, et al. The occurrence and risk factors associated with post-traumatic stress disorder among discharged covid-19 patients in Tianjin, China. Brain and Behavior. 2022; 12(2):e2492. [DOI:10.1002/brb3.2492] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ernst M, Brähler E, Beutel M. How can we support covid-19 survivors? Five lessons from long-term cancer survival. Public Health. 2021; 197:e8-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2020.12.017] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Batawi S, Tarazan N, Al-Raddadi R, Al Qasim E, Sindi A, Al Johni S, et al. Quality of life reported by survivors after hospitalization for Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS). Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2019; 17(1):101. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-019-1165-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Kim HC, Yoo SY, Lee BH, Lee SH, Shin HS. Psychiatric findings in suspected and confirmed Middle East respiratory syndrome patients quarantined in hospital: A retrospective chart analysis. Psychiatry Investigation. 2018; 15(4):355. [DOI:10.30773/pi.2017.10.25.1] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mak IW, Chu CM, Pan PC, Yiu MG, Chan VL. Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009; 31(4):318-26. [DOI:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.03.001] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Moradian ST, Parandeh A, Khalili R, Karimi L. Delayed symptoms in patients recovered from covid-19. Iranian Journal of Public Health. 2020; 49(11):2120-7. [DOI:10.18502/ijph.v49i11.4729] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Nagarajan R, Krishnamoorthy Y, Basavarachar V, Dakshinamoorthy R. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among survivors of severe covid-19 infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2022; 299:52-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.jad.2021.11.040] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Khademi M, Vaziri-Harami R, Shams J. Prevalence of mental health problems and its associated factors among recovered covid-19 patients during the pandemic: A single-center study. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2021; 12:602244. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.602244] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sun L, Yi B, Pan X, Wu L, Shang Z, Jia Y, et al. PTSD symptoms and sleep quality of covid-19 patients during hospitalization: An observational study from two centers. Nature and Science of Sleep. 2021; 12:602244. [DOI:10.2147/NSS.S317618] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Boks MP, van Mierlo HC, Rutten BP, Radstake TR, De Witte L, Geuze E, et al. Longitudinal changes of telomere length and epigenetic age related to traumatic stress and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015; 51:506-12. [DOI:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.07.011] [PMID]

- Huang Hh, Kashubeck-West S. Exposure, agency, perceived threat, and guilt as predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder in veterans. Journal of Counseling & Development. 2015; 93(1):3-13. [DOI:10.1002/j.1556-6676.2015.00176.x]

- Hosseininejad SM, Jahanian F, Elyasi F, Mokhtari H, Koulaei ME, Pashaei SM. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder among emergency nurses: A cross sectional study in northern Iran. BioMedicine. 2019; 9(3):19. [DOI:10.1051/bmdcn/2019090319] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sadeghi M, Taghva A, Goudarzi N, Rah Nejat A. [Validity and reliability of Persian version of “post-traumatic stress disorder scale” in war veterans (Persian)]. Iranian Journal of War and Public Health. 2016; 8(4):243-9. [Link]

- Bashar FR, Vahedian-Azimi A, Hajiesmaeili M, Salesi M, Farzanegan B, Shojaei S, et al. Post-ICU psychological morbidity in very long ICU stay patients with ARDS and delirium. Journal of Critical Care. 2018; 43:88-94. [DOI:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.08.034] [PMID]

- Wang CH, Tsay SL, Bond AE. Post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, anxiety and quality of life in patients with traffic-related injuries. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005; 52(1):22-30. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03560.x] [PMID]

- Liu N, Zhang F, Wei C, Jia Y, Shang Z, Sun L, et al. Prevalence and predictors of PTSS during covid-19 outbreak in China hardest-hit areas: Gender differences matter. Psychiatry Research. 2020; 287:112921. [DOI:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112921] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Xu J, Zheng Y, Wang M, Zhao J, Zhan Q, Fu M, et al. Predictors of symptoms of posttraumatic stress in Chinese university students during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Medical Science Monitor. 2011; 17(7):PH60. [DOI:10.12659/MSM.881836] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Hong X, Currier GW, Zhao X, Jiang Y, Zhou W, Wei J. Posttraumatic stress disorder in convalescent severe acute respiratory syndrome patients: A 4-year follow-up study. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2009; 31(6):546-54. [DOI:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.06.008] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Chong MY, Wang WC, Hsieh WC, Lee CY, Chiu NM, Yeh WC, et al. Psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome on health workers in a tertiary hospital. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2004; 185(2):127-33. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.185.2.127] [PMID]

- Yasan A, Saka G, Ozkan M, Ertem M. Trauma type, gender, and risk of PTSD in a region within an area of conflict. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2009; 22(6):663-6. [DOI:10.1002/jts.20459] [PMID]

- Christiansen DM, Hansen M. Accounting for sex differences in PTSD: A multi-variable mediation model. European Journal of Psychotraumatology. 2015; 6(1):26068. [DOI:10.3402/ejpt.v6.26068] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Liang L, Ren H, Cao R, Hu Y, Qin Z, Li C, et al. The effect of covid-19 on youth mental health. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2020; 91(3):841-52. [DOI:10.1007/s11126-020-09744-3] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Peng EY, Lee MB, Tsai ST, Yang CC, Morisky DE, Tsai LT, et al. Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: An example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. Journal of the Formosan Medical Association. 2010; 109(7):524-32. [DOI:10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60087-3] [PMID]

- Farhood L, Dimassi H, Strauss NL. Understanding post-conflict mental health: Assessment of PTSD, depression, general health and life events in civilian population one year after the 2006 war in South Lebanon. Journal of Traumatic Stress Disorders & Treatment. 2013; 2:2. [DOI:10.4172/2324-8947.1000103]

- Halpin SJ, McIvor C, Whyatt G, Adams A, Harvey O, McLean L, et al. Postdischarge symptoms and rehabilitation needs in survivors of covid-19 infection: A cross-sectional evaluation. Journal of Medical Virology. 2021; 93(2):1013-22. [DOI:10.1002/jmv.26368] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 26/09/2022 | Accepted: 6/12/2022 | Published: 1/01/2023

Received: 26/09/2022 | Accepted: 6/12/2022 | Published: 1/01/2023

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |