Volume 23, Issue 2 (Summer 2022)

jrehab 2022, 23(2): 272-289 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Rohani Ravari M H, Darouie A, Bakhshi E, Amiri E. The Effect of Distance Delivery of Lidcombe Program on The Severity of Stuttering in Preschool Children: A Single-Subject Study. jrehab 2022; 23 (2) :272-289

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2904-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2904-en.html

1- Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Koodakyar Alley, Daneshjoo Blvd., Velenjak, Tehran, Iran

2- Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,adarouie@hotmail.com

3- Department of Biostatistics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Biostatistics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Speech Therapy, school of rehabilitation, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran., Department of speech therapy, school of rehabilitation, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

2- Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

3- Department of Biostatistics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Department of Biostatistics, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4- Department of Speech Therapy, school of rehabilitation, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran., Department of speech therapy, school of rehabilitation, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 4215 kb]

(1768 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4576 Views)

Full-Text: (2627 Views)

Introduction

Stuttering is a speech disorder, in which the fluency of the individual’s speech is affected [1]. A person suffering from stuttering has special characteristics, including consecutive repetitions, prolongation of sounds, syllables, or words, or consecutive pauses, causing the development of disruption in the flow of speech [2]. The incidence of stuttering has been reported to be 1%, where at school and adult ages, its male-to-female ratio is 3 to 1, while during preschool ages, it is 1 to 1 [3]. The beginning of stuttering usually occurs between two and four years of age and after some time, the child is clearly distinguishable from their other peers. Early intervention and diagnosis of stuttering is the best solution, preventing its conversion to chronic stuttering and a long-term disability as well as its negative impact on the social and academic activities of the child in the future [4].

Lidcombe treatment program

Research has shown that rewarding the stutter-free speeches of preschool children can cause elevated fluency in speech among these children [5]. Lidcombe treatment program is a direct treatment for stuttering in children [6], which has been designed based on rewarding the fluent speech of children [5]. Lidcombe program is a behavioral program, in which the operant conditioning method is used. In this program, parents present variable stimuli to the child at home, and the therapist during weekly sessions presents guidelines about the type and number of these feedbacks to the parents. In the Lidcombe program, first, the therapist trains the parents on how the severity scoring scale should be used and also investigates the accuracy of the scores of parents throughout the treatment course. The therapist performs this by scoring parents and their children to a single sample of speech. Then, the therapist trains the parents on how to reward the fluent speeches of the child and give feedback in a respectable matter to the stutter speeches of the child. These rewards and feedback are transferred in structured conversations at the beginning of the treatment and then with a reduction of stuttering in the child to other daily situations. According to this program, the therapist and parents assess the child regularly to investigate the progress and make therapeutic decisions [3]. This program has two phases, where after reaching the first phase, i.e. when the child has no or minimum stuttering, the child enters the second phase of this program. To finalize the first phase, the child should achieve these criteria in three consecutive weeks: A severity rating of zero or one, which has at least four zero scores within a week and the percentage of syllables stuttered in clinical sessions should be zero or one. The second phase aims to preserve the aim of the first phase for the long-term and stabilize it [7]. Various studies have been conducted to investigate the effect of the Lidcombe program, according to which the effect of this program on mitigating stuttering in children younger than six years old and schoolchildren (6-10 years of age) has been confirmed [8, 9, 10].

Therapeutic

Most therapeutic programs require children and parents to visit care centers for one or several sessions during the week [7]. However, in some cases, problems may arise, causing the clients not to be able to participate in this therapeutic program regularly. One of the problems in this regard is the shortage of speech and language pathologists, especially in small cities and villages [11]. Other problems include the high cost of transportation, the daily and professional preoccupations of the parents, and the physical state of the patient, which can cause leaving the house and visiting the care centers to become difficult or even impossible. Therefore, people suffering from these problems are not able to receive the required care services.

In recent years, communication sciences have advanced considerably and live communication between very far distances has also become possible. Today, these live communications have various uses, one of which is their applications in health and medical issues. Telemedicine means offering telehealth services or exchange of information about healthcare services. Other terms, including telehealth, telepractice, and telecare are also used in this regard, all of which refer to the exchange of health information throughout some distant points, leading to the promotion of the health of individuals [12]. According to the definition by the American Speech, Language, and Hearing Association, telepractice has been designed with the aim of utilizing telecommunications technology to establish a connection between the therapist and patient or therapist with the therapist with aim of assessment, treatment, or consultancy [13]. It is also a suitable model to overcome the problems of not having the access to care services due to long-distance or shortage of specialists [14]. Various studies have been performed across different countries with the aim of investigating the effect of several types of treatment through telepractice on stuttering [15, 16]. Furthermore, studies have also been conducted on other disorders, including speech sound disorders [17], voice disorders [18], swallowing disorders [19], and aphasia [20].

Outside Iran, also, some studies have been conducted on telepractice of communication disorders, including stuttering, with the results of the effectiveness of the treatment and satisfaction of the person suffering from stuttering and their parents [16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. Among these studies is the research by Sue O’Brian et al. in Australia, in which the researchers investigated the extent of the first phase effect of the Lidcombe program on three children suffering from stuttering. In the treatment, the therapist held the sessions on a weekly basis through Internet video communication, and throughout the treatment, no face-to-face treatment occurred between the therapist and the child or the parents. After the treatment, the results suggested diminished stuttering in the children and satisfaction of the parents and the therapist about the way the treatment was offered [24].

In another study done by Valentine in 2014, the cure for stuttering was presented in three ways. The subjects of this study were a boy and a girl, both aged 11 years, who were evaluated by Stuttering Severity Instrument, Fourth Edition (SSI4), and Communication Attitude Test (CAT) tests. The evaluation of the SSI4 test was fulfilled before and after each course of the treatment, for which the modified stuttering techniques were used. The whole process was run in three courses of face-to-face treatment, face-to-face treatment plus telepractice, and telepractice solely. In the end, the results showed that direct treatment was the most successful one, which continued in the other two courses. Therefore, the scholars included that telepractice is proper and effective in the increase and stabilization of speech fluency [25].

In a review study on telepractice accomplished by Theodores in 2011, the advantages, scientific evidence, challenges, and the future of telepractice were analyzed. The effectiveness of this type of treatment in some disorders, such as adult neurological disorders, sound disorders, stutter, language and speech disorders plus swallowing disorders was reported. The mentioned challenges in this study are related to professional issues (including the fact that most therapists believe face-to-face treatment is the golden standard), the impossibility of a therapist to provide treatment in other states, and also the necessity of training other therapists for telepractice, telepractice refunds, clinical outcome, and its efficiency. The last challenge would be related to the present technology. It needs to provide a situation, in which the therapist is able to fulfill the same tasks he does in the face-to-face sessions as well as telepractice ones. At the end of this study, the writers recommended more studies to be done in the field of telepractice treatment efficiencies. They stated that a collection of expected results of the telepractice treatment should be added to decide more easily on the effectiveness of the treatment in establishing the policy and insurance. Moreover, another issue was to determine the characteristics of the patient, like physical, behavioral, and cultural ones, which may affect the telepractice treatment results [26].

In the course of studies conducted in Iranian information banks, no research was found regarding the presentation of the speech telepractice services. Regarding the differences that exist across different cultures on video communication, and because usage of communication sciences is developing for distantly performing tasks throughout the world and establishment of communication between very far points has become possible; some research should also be conducted in Iran. Accordingly, this research investigated the effect of distance delivery of the Lidcombe telepractice program on stuttering in preschool children.

Materials and Methods

The design of the study

This research is a single-subject study with an A-B design. It has three phases, including the first baseline, treatment, and second baseline. The first baseline lasted three weeks, during which no treatment was done and the parents recorded the scores of severity using the 9-score scale developed for the severity in the Lidcombe program on a daily basis. Then, during a session, which was held through video communication, they reported the results to the therapist. The therapist also recorded the percentage of stuttered syllables in the same session after taking a sample from the child’s speech. Eventually, in the course of the first baseline, 3 times the percentage of stuttered syllables and 21 severity ratings were recorded. In the treatment phase, the sessions were held on a weekly basis through video communication, where for each subject, 15 sessions were held. During the treatment phase, the assessments were continued, where overall in the baseline, 15 assessments of a percentage of syllables stuttered and 105 severity ratings were recorded for each subject. In the second baseline conducted during three weeks, the assessments were recorded as with the first baseline, i.e., the percentage of stuttered syllables three times and 21 severity ratings.

Subjects

The studied population was preschool children suffering from stuttering and the studied samples were chosen by available sampling from the Kerman and Fars provinces of Iran. Stuttering in the children was confirmed by two speech and language pathologists and these subjects had the inclusion and exclusion criteria, including the age between four and six years, the onset of stuttering at least six months ago, access to the Internet at home, consent of parents for cooperation, and absence of accompanying disorders, including behavioral, vision, hearing, and mental disorders.

Subject No. 1

The first subject was a boy five years and three months old at the first baseline. The onset of stuttering in the subject was seven months ago and the percentage of syllables stuttered in this child at the beginning of the baseline was 16% and the severity of stuttering was six. Seven months after the onset of stuttering, this child had not received any treatment for his condition.

Subject No. 2

This subject was also a boy at five years and seven months of age at the baseline. The percentage of syllables stuttered in this child was 12% and stuttering severity was four. According to his parents, stuttering began in this child around one year ago. This child had not received any treatment for his condition.

Subject No. 3

The third subject was a boy at four years and ten months of age at the beginning of the first baseline. At baseline, the percentage of syllables stuttered in this child was 21% and stuttering severity was six. This child had been suffering from stuttering for a year and had not received any treatment for his condition.

Subject No. 4

The fourth subject was a girl five years and six months of age, whose stuttering began one and a half years ago. The percentage of syllables stuttered in this child at the beginning of the baseline was 16% and the stuttering severity was seven. This child had not received any treatment for his condition.

Subject No. 5

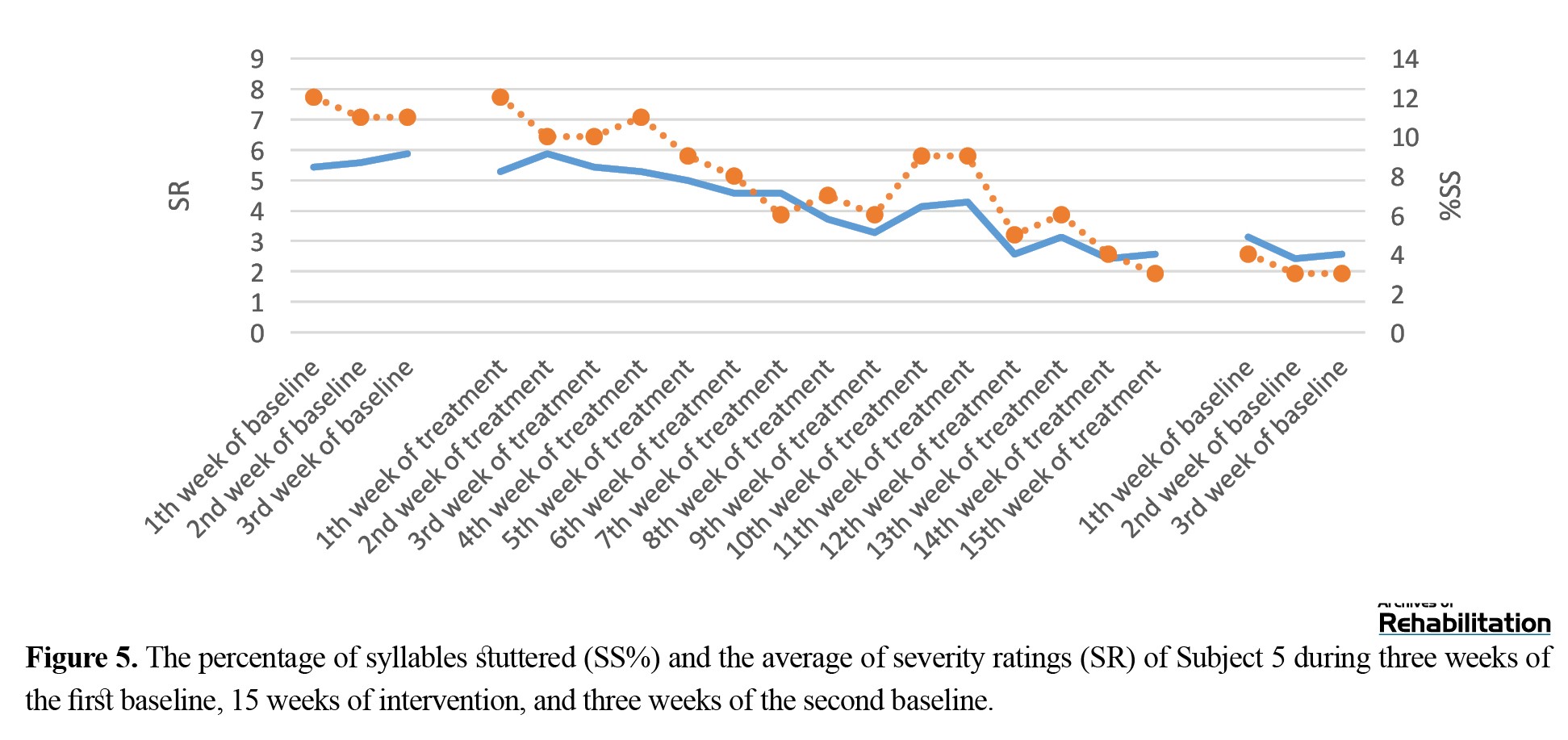

The fifth subject was a girl of four years and two months of age. According to her parents, this child had been suffering from stuttering for six months. The percentage of syllables stuttered in this child at the beginning of the baseline was 12% and stuttering severity was seven. This child had not received any treatment for his condition.

The treatment procedure:

Following sampling, the procedure of the treatment was explained to the children’s parents in a face-to-face session, during which constant form and personal information questionnaires were filled by the parents. As in this study, severity ratings were used for assessment during the first baseline, in the same face-to-face session, the way the 9-score scale should be used was trained to the parents. On this scale, a score of zero is stutter-free speech, while a score of nine is the most intense stutter that has occurred. Before starting the treatment, during the baseline for three weeks, three assessments regarding the percentage of syllables stuttered were recorded by the therapist through video communication and the score of severity of stuttering was recorded by the parents on a daily basis. Three weeks after the baseline, the treatment of children was initiated through video communication between the therapist in the clinic and the studied individuals at home using Skype software.

The utilized treatment was the first phase of the Lidcombe treatment program and the procedure of sessions was conducted according to the guidelines of this treatment program, which is available at the site of Sydney University stuttering Research Center [7]. The only difference was the implementation of the program was distant, whereby the duration of interaction between the therapist and the child decreased, and the major part of the therapeutic session was devoted to giving training and consultancy to the parents and the observation of the interaction between the parents and the child. The therapeutic sessions were held as one session per week for 45-60 minutes by a speech and language pathologist with three years of experience in implementing the Lidcombe program.

Overall, during therapeutic sessions, first, the therapist observed the interaction between parents and the child for 10-15 minutes. The parents could use any subject or things, such as a book, LEGO, etc. in which the child was interested in establishing an interaction. During this interaction, the therapist recorded the percentage of syllables stuttered as well as severity rating using the 9-score scale. Next, the parents gave the severity ratings of the previous week to the therapist and the therapist discussed elevation or reduction of the severity ratings with the parents to inquire about the reasons for these elevations. Then, after finding the reason, the therapist asked the parents how they could solve the problems. Thereafter, the parents demonstrated the manner of giving feedback during an interaction, and after observation by the therapist, he corrected the problems in the way parents gave feedback to the children. By the end of the session, the therapist stated a summary of the subjects discussed in the session and terminated the session. During the first baseline, treatment period, and second baseline, no face-to-face session was held between the therapist and the parents and children, and all the sessions were held through live video communication.

Assessments for investigating the progress of the treatment were based on the therapeutic protocol of the Lidcombe program. The percentage of syllables stuttered was recorded by the therapist each week at the beginning of the session and the severity of stuttering was recorded daily by the parents according to the 9-score scale of the Lidcombe program. By the end of the 15 sessions, the assessments of the first baseline were performed again, including three times the percentage of syllables stuttered and 21 severity ratings during three weeks without offering treatment.

The data of this research were analyzed and investigated using Microsoft Office Excel 2017 and SPSS 19. In this study, in addition to presenting descriptive statistics and plotting diagrams, Z-index was also used.

Results

The results obtained are stated below for each subject.

Subject 1

The percentage of syllables stuttered for subject No. 1 decreased from 16% in the first baseline to 4% in the second baseline. Furthermore, the scores of stuttering severity decreased from an average of seven in the first baseline to an average of two in the second baseline. According to Z-index, changes in the scores of stuttering severity in the first (Z=0.95<1.64) and second (Z=0.31<1.64) baseline were not significant; however, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=4.68>1.64). The scores of severity and percentage of syllables stuttered during the 15 treatment sessions had a descending trend. By the end of the 15 sessions, the children did not achieve the final criteria of the first phase of the Lidcombe program (Figure 1). Subject No. 2

The percentage of syllables stuttered and severity ratings of subject No. 2 in the first and second baselines suggest the diminished percentage of stuttered syllables from 12% to 1%. Also, the security of stuttering declined from an average of five to one. According to Z-index, changes in the stuttering severity ratings were not significant in the first (Z=-1.3<1.64) and second (Z=0<1.64) baselines. However, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=4.57>1.64). The second subject approached the final criteria of the first phase, though he did not achieve them (Figure 2). Subject No. 3

The percentage of syllables stuttered in this subject decreased from 23% in the first baseline to 7% in the second baseline. Also, the severity ratings diminished from an average of seven to two. According to Z-index, changes in the stuttering severity ratings were not significant in the first (Z=1.3<1.64) and second (Z=-0.4<1.64) baselines. However, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=4.8>1.64). This subject did not achieve the final criteria of the first phase (Figure 3). Subject No. 4

In this subject, the percentage of syllables stuttered decreased from 16% in the first baseline to 8% in the second baseline. Also, the severity ratings diminished from an average of seven to three. According to Z-index, changes in the stuttering severity ratings were not significant in the first (Z=-0.8<1.64) and second (Z=-4.8<1.64) baselines. However, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=2.4>1.64). By the end of the 15 sessions, this subject did not achieve the final criteria of the first phase. In the second baseline, we observed increased severity ratings and percentage of stuttered syllables (Figure 4). Subject No. 5

The percentage of syllables stuttered in the subject decreased from 11% in the first baseline to 2% in the second baseline, and severity ratings declined from an average of six to two. According to Z-index, changes in the stuttering severity ratings were not significant in the first (Z=-5.5<1.64) and second (Z=-2/4<1/64) baselines. However, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=3.5>1.64). By the end of the 15 sessions, this subject approached the final criteria of the first phase, though she did not achieve them (Figure 5). Discussion

Four subjects (subjects 1, 2, 3, and 5) had a reduction in the percentage of syllables stuttered as well as severity ratings and preserved this reduction until the end of the second baseline. One of the subjects (subject 4) showed an increased percentage of syllables stuttered and severity ratings by the end of the second baseline. This is common in some children throughout Lidcombe treatment and after it, where stuttering can diminish again with repetition of the previous stages of the treatment [27, 28].

In the diagram of scores of stuttering severity and percentage of syllables stuttered by the subjects, throughout the treatments, a dramatic increase was observed in some weeks. According to the therapist, these elevations were a result of increased or decreased number of feedbacks, problems in the manner of giving feedback, exaggeration in giving feedback, lack of proportion between positive and negative feedback, disrupting the speech of the child to give feedback and sensitivity of the child to negative feedbacks. These issues were solved through the guidelines of the therapist. As the environment has a huge impact on stuttering in preschool children [6], these elevations can also be a result of other environmental changes and stressing factors in the environment. For example, in subject 3, some fluctuations can be observed throughout the treatment phase, where according to the mother, throughout this duration, some disputes occurred in the family, where these elevations and reductions in the severity and percentage of stuttering may be due to environmental stress and anxiety. Furthermore, during weeks ten and 11, subject 5 experienced an increased percentage of stuttered syllables and severity ratings, during which the child suffered from a disease and these elevations may be due to this disease.

In spite of the proven cases observed in the subjects and approximation of a number of them (subjects 1 and 2) to the criteria of the first phase of the Lidcombe program, these subjects were not able to achieve the criteria. In the therapeutic guideline of the Lidcombe program, the average number of sessions required to achieve therapeutic targets of the first phase has been reported to be 16 [7]. However, in this study, during the 15 sessions of treatment, which had been considered here, the subjects were not able to achieve the final targets of the first phase. These findings are in line with the findings of research conducted by O’Brian et al. in Australia, in which implementation of the Lidcombe program also took longer, in comparison with in-person treatment [24]. Not achieving the targets of the first phase of the Lidcombe program could be due to the fact that this study was the first experience of the therapist in treating the disorder through video communication.

The results of a study conducted in Malaysia regarding usage of the in-person Lidcombe treatment program on bilingual children suggested that the subjects needed a longer time to achieve the objectives of the first phase of the program; in comparison with the duration reported in other studies. The author stated the reason for prolongation as training the parents to learn proper manners of giving feedback and rewards. According to him, this can be due to cultural differences, as in Malaysian families, rewarding behaviors are used less frequently [29]. Kingstone et al. in England showed that an average of 21 sessions are required for completion of the first phase of the Lidcombe program. The reason for the prolongation of the first phase in comparison with other studies, as with the study conducted in Malaysia, was cultural differences. They also considered the severity of stuttering at the beginning of the treatment and the age of the child as the determination of the factors in the duration of the treatment [30].

Conclusion

Finally, the obtained results indicated that after the 15 treatment sessions through live video communication, the stuttering diminished in the subjects. Based on the results and the level of improvement developed in the subjects, it can be stated that Lidcombe telepractice can be a suitable alternative for direct treatment in those who have no access to direct treatment.

Based on our search, this study is the first on telepractice of stuttering in Iran. The extent of the effect of the Lidcombe program through video communication and the sense of satisfaction of the families about this method indicated that implementation of this program, given the facilities of Iran, is possible and effective. Also, this type of treatment was acceptable among families.

To be able to generalize the results of this study to the whole society, further studies should be conducted with larger sample size. Moreover, to compare the extent of the effect of this therapeutic method and in-person treatment, more studies should also be conducted.

Study limitations

The therapist’s low experience in telepractice was one of the limitations, which may cause a longer course of treatment. Furthermore, the difference between families’ cooperation in performing the treatment may influence the results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

In this study, to respect the rights of the participants before entering the study, complete information about the implementation process of this study was provided to them. If the participants are satisfied, they voluntarily signed the written consent form related to the participants and entered this study. In this study, participants could discontinue their cooperation at any stage of the study and leave the study. To protect the personal sanctuary and personal information of the participants, all their information remained confidential, and to report the results, a numeric code was used to indicate the participant. It should be noted that the issues related to the ethics of this study have been approved by the code of ethics IR.USWR.REC.1395.308 by the ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the MA Thesis of Mr. Mohmmad Hosein Rohani Ravari, Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Akbar Darouie, Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari; Methodology: Akbar Darouie; Validation: Akbar Darouie, Enayatollah Bakhshi, Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari; Analysis: Enayatollah Bakhshi, Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari; Research and review of resources: Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari, Ehsan Amiri; Drafting: Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari, Ehsan Amiri; Editing and finalizing the writing: Akbar Darouie, Enayatollah Bakhshi; Supervision: Akbar Darouie, Enayatollah Bakhshi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the people who shared their assistance in fulfilling this study; particularly the subjects' families.

References

Stuttering is a speech disorder, in which the fluency of the individual’s speech is affected [1]. A person suffering from stuttering has special characteristics, including consecutive repetitions, prolongation of sounds, syllables, or words, or consecutive pauses, causing the development of disruption in the flow of speech [2]. The incidence of stuttering has been reported to be 1%, where at school and adult ages, its male-to-female ratio is 3 to 1, while during preschool ages, it is 1 to 1 [3]. The beginning of stuttering usually occurs between two and four years of age and after some time, the child is clearly distinguishable from their other peers. Early intervention and diagnosis of stuttering is the best solution, preventing its conversion to chronic stuttering and a long-term disability as well as its negative impact on the social and academic activities of the child in the future [4].

Lidcombe treatment program

Research has shown that rewarding the stutter-free speeches of preschool children can cause elevated fluency in speech among these children [5]. Lidcombe treatment program is a direct treatment for stuttering in children [6], which has been designed based on rewarding the fluent speech of children [5]. Lidcombe program is a behavioral program, in which the operant conditioning method is used. In this program, parents present variable stimuli to the child at home, and the therapist during weekly sessions presents guidelines about the type and number of these feedbacks to the parents. In the Lidcombe program, first, the therapist trains the parents on how the severity scoring scale should be used and also investigates the accuracy of the scores of parents throughout the treatment course. The therapist performs this by scoring parents and their children to a single sample of speech. Then, the therapist trains the parents on how to reward the fluent speeches of the child and give feedback in a respectable matter to the stutter speeches of the child. These rewards and feedback are transferred in structured conversations at the beginning of the treatment and then with a reduction of stuttering in the child to other daily situations. According to this program, the therapist and parents assess the child regularly to investigate the progress and make therapeutic decisions [3]. This program has two phases, where after reaching the first phase, i.e. when the child has no or minimum stuttering, the child enters the second phase of this program. To finalize the first phase, the child should achieve these criteria in three consecutive weeks: A severity rating of zero or one, which has at least four zero scores within a week and the percentage of syllables stuttered in clinical sessions should be zero or one. The second phase aims to preserve the aim of the first phase for the long-term and stabilize it [7]. Various studies have been conducted to investigate the effect of the Lidcombe program, according to which the effect of this program on mitigating stuttering in children younger than six years old and schoolchildren (6-10 years of age) has been confirmed [8, 9, 10].

Therapeutic

Most therapeutic programs require children and parents to visit care centers for one or several sessions during the week [7]. However, in some cases, problems may arise, causing the clients not to be able to participate in this therapeutic program regularly. One of the problems in this regard is the shortage of speech and language pathologists, especially in small cities and villages [11]. Other problems include the high cost of transportation, the daily and professional preoccupations of the parents, and the physical state of the patient, which can cause leaving the house and visiting the care centers to become difficult or even impossible. Therefore, people suffering from these problems are not able to receive the required care services.

In recent years, communication sciences have advanced considerably and live communication between very far distances has also become possible. Today, these live communications have various uses, one of which is their applications in health and medical issues. Telemedicine means offering telehealth services or exchange of information about healthcare services. Other terms, including telehealth, telepractice, and telecare are also used in this regard, all of which refer to the exchange of health information throughout some distant points, leading to the promotion of the health of individuals [12]. According to the definition by the American Speech, Language, and Hearing Association, telepractice has been designed with the aim of utilizing telecommunications technology to establish a connection between the therapist and patient or therapist with the therapist with aim of assessment, treatment, or consultancy [13]. It is also a suitable model to overcome the problems of not having the access to care services due to long-distance or shortage of specialists [14]. Various studies have been performed across different countries with the aim of investigating the effect of several types of treatment through telepractice on stuttering [15, 16]. Furthermore, studies have also been conducted on other disorders, including speech sound disorders [17], voice disorders [18], swallowing disorders [19], and aphasia [20].

Outside Iran, also, some studies have been conducted on telepractice of communication disorders, including stuttering, with the results of the effectiveness of the treatment and satisfaction of the person suffering from stuttering and their parents [16, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]. Among these studies is the research by Sue O’Brian et al. in Australia, in which the researchers investigated the extent of the first phase effect of the Lidcombe program on three children suffering from stuttering. In the treatment, the therapist held the sessions on a weekly basis through Internet video communication, and throughout the treatment, no face-to-face treatment occurred between the therapist and the child or the parents. After the treatment, the results suggested diminished stuttering in the children and satisfaction of the parents and the therapist about the way the treatment was offered [24].

In another study done by Valentine in 2014, the cure for stuttering was presented in three ways. The subjects of this study were a boy and a girl, both aged 11 years, who were evaluated by Stuttering Severity Instrument, Fourth Edition (SSI4), and Communication Attitude Test (CAT) tests. The evaluation of the SSI4 test was fulfilled before and after each course of the treatment, for which the modified stuttering techniques were used. The whole process was run in three courses of face-to-face treatment, face-to-face treatment plus telepractice, and telepractice solely. In the end, the results showed that direct treatment was the most successful one, which continued in the other two courses. Therefore, the scholars included that telepractice is proper and effective in the increase and stabilization of speech fluency [25].

In a review study on telepractice accomplished by Theodores in 2011, the advantages, scientific evidence, challenges, and the future of telepractice were analyzed. The effectiveness of this type of treatment in some disorders, such as adult neurological disorders, sound disorders, stutter, language and speech disorders plus swallowing disorders was reported. The mentioned challenges in this study are related to professional issues (including the fact that most therapists believe face-to-face treatment is the golden standard), the impossibility of a therapist to provide treatment in other states, and also the necessity of training other therapists for telepractice, telepractice refunds, clinical outcome, and its efficiency. The last challenge would be related to the present technology. It needs to provide a situation, in which the therapist is able to fulfill the same tasks he does in the face-to-face sessions as well as telepractice ones. At the end of this study, the writers recommended more studies to be done in the field of telepractice treatment efficiencies. They stated that a collection of expected results of the telepractice treatment should be added to decide more easily on the effectiveness of the treatment in establishing the policy and insurance. Moreover, another issue was to determine the characteristics of the patient, like physical, behavioral, and cultural ones, which may affect the telepractice treatment results [26].

In the course of studies conducted in Iranian information banks, no research was found regarding the presentation of the speech telepractice services. Regarding the differences that exist across different cultures on video communication, and because usage of communication sciences is developing for distantly performing tasks throughout the world and establishment of communication between very far points has become possible; some research should also be conducted in Iran. Accordingly, this research investigated the effect of distance delivery of the Lidcombe telepractice program on stuttering in preschool children.

Materials and Methods

The design of the study

This research is a single-subject study with an A-B design. It has three phases, including the first baseline, treatment, and second baseline. The first baseline lasted three weeks, during which no treatment was done and the parents recorded the scores of severity using the 9-score scale developed for the severity in the Lidcombe program on a daily basis. Then, during a session, which was held through video communication, they reported the results to the therapist. The therapist also recorded the percentage of stuttered syllables in the same session after taking a sample from the child’s speech. Eventually, in the course of the first baseline, 3 times the percentage of stuttered syllables and 21 severity ratings were recorded. In the treatment phase, the sessions were held on a weekly basis through video communication, where for each subject, 15 sessions were held. During the treatment phase, the assessments were continued, where overall in the baseline, 15 assessments of a percentage of syllables stuttered and 105 severity ratings were recorded for each subject. In the second baseline conducted during three weeks, the assessments were recorded as with the first baseline, i.e., the percentage of stuttered syllables three times and 21 severity ratings.

Subjects

The studied population was preschool children suffering from stuttering and the studied samples were chosen by available sampling from the Kerman and Fars provinces of Iran. Stuttering in the children was confirmed by two speech and language pathologists and these subjects had the inclusion and exclusion criteria, including the age between four and six years, the onset of stuttering at least six months ago, access to the Internet at home, consent of parents for cooperation, and absence of accompanying disorders, including behavioral, vision, hearing, and mental disorders.

Subject No. 1

The first subject was a boy five years and three months old at the first baseline. The onset of stuttering in the subject was seven months ago and the percentage of syllables stuttered in this child at the beginning of the baseline was 16% and the severity of stuttering was six. Seven months after the onset of stuttering, this child had not received any treatment for his condition.

Subject No. 2

This subject was also a boy at five years and seven months of age at the baseline. The percentage of syllables stuttered in this child was 12% and stuttering severity was four. According to his parents, stuttering began in this child around one year ago. This child had not received any treatment for his condition.

Subject No. 3

The third subject was a boy at four years and ten months of age at the beginning of the first baseline. At baseline, the percentage of syllables stuttered in this child was 21% and stuttering severity was six. This child had been suffering from stuttering for a year and had not received any treatment for his condition.

Subject No. 4

The fourth subject was a girl five years and six months of age, whose stuttering began one and a half years ago. The percentage of syllables stuttered in this child at the beginning of the baseline was 16% and the stuttering severity was seven. This child had not received any treatment for his condition.

Subject No. 5

The fifth subject was a girl of four years and two months of age. According to her parents, this child had been suffering from stuttering for six months. The percentage of syllables stuttered in this child at the beginning of the baseline was 12% and stuttering severity was seven. This child had not received any treatment for his condition.

The treatment procedure:

Following sampling, the procedure of the treatment was explained to the children’s parents in a face-to-face session, during which constant form and personal information questionnaires were filled by the parents. As in this study, severity ratings were used for assessment during the first baseline, in the same face-to-face session, the way the 9-score scale should be used was trained to the parents. On this scale, a score of zero is stutter-free speech, while a score of nine is the most intense stutter that has occurred. Before starting the treatment, during the baseline for three weeks, three assessments regarding the percentage of syllables stuttered were recorded by the therapist through video communication and the score of severity of stuttering was recorded by the parents on a daily basis. Three weeks after the baseline, the treatment of children was initiated through video communication between the therapist in the clinic and the studied individuals at home using Skype software.

The utilized treatment was the first phase of the Lidcombe treatment program and the procedure of sessions was conducted according to the guidelines of this treatment program, which is available at the site of Sydney University stuttering Research Center [7]. The only difference was the implementation of the program was distant, whereby the duration of interaction between the therapist and the child decreased, and the major part of the therapeutic session was devoted to giving training and consultancy to the parents and the observation of the interaction between the parents and the child. The therapeutic sessions were held as one session per week for 45-60 minutes by a speech and language pathologist with three years of experience in implementing the Lidcombe program.

Overall, during therapeutic sessions, first, the therapist observed the interaction between parents and the child for 10-15 minutes. The parents could use any subject or things, such as a book, LEGO, etc. in which the child was interested in establishing an interaction. During this interaction, the therapist recorded the percentage of syllables stuttered as well as severity rating using the 9-score scale. Next, the parents gave the severity ratings of the previous week to the therapist and the therapist discussed elevation or reduction of the severity ratings with the parents to inquire about the reasons for these elevations. Then, after finding the reason, the therapist asked the parents how they could solve the problems. Thereafter, the parents demonstrated the manner of giving feedback during an interaction, and after observation by the therapist, he corrected the problems in the way parents gave feedback to the children. By the end of the session, the therapist stated a summary of the subjects discussed in the session and terminated the session. During the first baseline, treatment period, and second baseline, no face-to-face session was held between the therapist and the parents and children, and all the sessions were held through live video communication.

Assessments for investigating the progress of the treatment were based on the therapeutic protocol of the Lidcombe program. The percentage of syllables stuttered was recorded by the therapist each week at the beginning of the session and the severity of stuttering was recorded daily by the parents according to the 9-score scale of the Lidcombe program. By the end of the 15 sessions, the assessments of the first baseline were performed again, including three times the percentage of syllables stuttered and 21 severity ratings during three weeks without offering treatment.

The data of this research were analyzed and investigated using Microsoft Office Excel 2017 and SPSS 19. In this study, in addition to presenting descriptive statistics and plotting diagrams, Z-index was also used.

Results

The results obtained are stated below for each subject.

Subject 1

The percentage of syllables stuttered for subject No. 1 decreased from 16% in the first baseline to 4% in the second baseline. Furthermore, the scores of stuttering severity decreased from an average of seven in the first baseline to an average of two in the second baseline. According to Z-index, changes in the scores of stuttering severity in the first (Z=0.95<1.64) and second (Z=0.31<1.64) baseline were not significant; however, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=4.68>1.64). The scores of severity and percentage of syllables stuttered during the 15 treatment sessions had a descending trend. By the end of the 15 sessions, the children did not achieve the final criteria of the first phase of the Lidcombe program (Figure 1). Subject No. 2

The percentage of syllables stuttered and severity ratings of subject No. 2 in the first and second baselines suggest the diminished percentage of stuttered syllables from 12% to 1%. Also, the security of stuttering declined from an average of five to one. According to Z-index, changes in the stuttering severity ratings were not significant in the first (Z=-1.3<1.64) and second (Z=0<1.64) baselines. However, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=4.57>1.64). The second subject approached the final criteria of the first phase, though he did not achieve them (Figure 2). Subject No. 3

The percentage of syllables stuttered in this subject decreased from 23% in the first baseline to 7% in the second baseline. Also, the severity ratings diminished from an average of seven to two. According to Z-index, changes in the stuttering severity ratings were not significant in the first (Z=1.3<1.64) and second (Z=-0.4<1.64) baselines. However, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=4.8>1.64). This subject did not achieve the final criteria of the first phase (Figure 3). Subject No. 4

In this subject, the percentage of syllables stuttered decreased from 16% in the first baseline to 8% in the second baseline. Also, the severity ratings diminished from an average of seven to three. According to Z-index, changes in the stuttering severity ratings were not significant in the first (Z=-0.8<1.64) and second (Z=-4.8<1.64) baselines. However, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=2.4>1.64). By the end of the 15 sessions, this subject did not achieve the final criteria of the first phase. In the second baseline, we observed increased severity ratings and percentage of stuttered syllables (Figure 4). Subject No. 5

The percentage of syllables stuttered in the subject decreased from 11% in the first baseline to 2% in the second baseline, and severity ratings declined from an average of six to two. According to Z-index, changes in the stuttering severity ratings were not significant in the first (Z=-5.5<1.64) and second (Z=-2/4<1/64) baselines. However, these changes were significant in the treatment phase (Z=3.5>1.64). By the end of the 15 sessions, this subject approached the final criteria of the first phase, though she did not achieve them (Figure 5). Discussion

Four subjects (subjects 1, 2, 3, and 5) had a reduction in the percentage of syllables stuttered as well as severity ratings and preserved this reduction until the end of the second baseline. One of the subjects (subject 4) showed an increased percentage of syllables stuttered and severity ratings by the end of the second baseline. This is common in some children throughout Lidcombe treatment and after it, where stuttering can diminish again with repetition of the previous stages of the treatment [27, 28].

In the diagram of scores of stuttering severity and percentage of syllables stuttered by the subjects, throughout the treatments, a dramatic increase was observed in some weeks. According to the therapist, these elevations were a result of increased or decreased number of feedbacks, problems in the manner of giving feedback, exaggeration in giving feedback, lack of proportion between positive and negative feedback, disrupting the speech of the child to give feedback and sensitivity of the child to negative feedbacks. These issues were solved through the guidelines of the therapist. As the environment has a huge impact on stuttering in preschool children [6], these elevations can also be a result of other environmental changes and stressing factors in the environment. For example, in subject 3, some fluctuations can be observed throughout the treatment phase, where according to the mother, throughout this duration, some disputes occurred in the family, where these elevations and reductions in the severity and percentage of stuttering may be due to environmental stress and anxiety. Furthermore, during weeks ten and 11, subject 5 experienced an increased percentage of stuttered syllables and severity ratings, during which the child suffered from a disease and these elevations may be due to this disease.

In spite of the proven cases observed in the subjects and approximation of a number of them (subjects 1 and 2) to the criteria of the first phase of the Lidcombe program, these subjects were not able to achieve the criteria. In the therapeutic guideline of the Lidcombe program, the average number of sessions required to achieve therapeutic targets of the first phase has been reported to be 16 [7]. However, in this study, during the 15 sessions of treatment, which had been considered here, the subjects were not able to achieve the final targets of the first phase. These findings are in line with the findings of research conducted by O’Brian et al. in Australia, in which implementation of the Lidcombe program also took longer, in comparison with in-person treatment [24]. Not achieving the targets of the first phase of the Lidcombe program could be due to the fact that this study was the first experience of the therapist in treating the disorder through video communication.

The results of a study conducted in Malaysia regarding usage of the in-person Lidcombe treatment program on bilingual children suggested that the subjects needed a longer time to achieve the objectives of the first phase of the program; in comparison with the duration reported in other studies. The author stated the reason for prolongation as training the parents to learn proper manners of giving feedback and rewards. According to him, this can be due to cultural differences, as in Malaysian families, rewarding behaviors are used less frequently [29]. Kingstone et al. in England showed that an average of 21 sessions are required for completion of the first phase of the Lidcombe program. The reason for the prolongation of the first phase in comparison with other studies, as with the study conducted in Malaysia, was cultural differences. They also considered the severity of stuttering at the beginning of the treatment and the age of the child as the determination of the factors in the duration of the treatment [30].

Conclusion

Finally, the obtained results indicated that after the 15 treatment sessions through live video communication, the stuttering diminished in the subjects. Based on the results and the level of improvement developed in the subjects, it can be stated that Lidcombe telepractice can be a suitable alternative for direct treatment in those who have no access to direct treatment.

Based on our search, this study is the first on telepractice of stuttering in Iran. The extent of the effect of the Lidcombe program through video communication and the sense of satisfaction of the families about this method indicated that implementation of this program, given the facilities of Iran, is possible and effective. Also, this type of treatment was acceptable among families.

To be able to generalize the results of this study to the whole society, further studies should be conducted with larger sample size. Moreover, to compare the extent of the effect of this therapeutic method and in-person treatment, more studies should also be conducted.

Study limitations

The therapist’s low experience in telepractice was one of the limitations, which may cause a longer course of treatment. Furthermore, the difference between families’ cooperation in performing the treatment may influence the results.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

In this study, to respect the rights of the participants before entering the study, complete information about the implementation process of this study was provided to them. If the participants are satisfied, they voluntarily signed the written consent form related to the participants and entered this study. In this study, participants could discontinue their cooperation at any stage of the study and leave the study. To protect the personal sanctuary and personal information of the participants, all their information remained confidential, and to report the results, a numeric code was used to indicate the participant. It should be noted that the issues related to the ethics of this study have been approved by the code of ethics IR.USWR.REC.1395.308 by the ethics committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the MA Thesis of Mr. Mohmmad Hosein Rohani Ravari, Department of Speech Therapy, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: Akbar Darouie, Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari; Methodology: Akbar Darouie; Validation: Akbar Darouie, Enayatollah Bakhshi, Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari; Analysis: Enayatollah Bakhshi, Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari; Research and review of resources: Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari, Ehsan Amiri; Drafting: Mohammad Hosein Rohani Ravari, Ehsan Amiri; Editing and finalizing the writing: Akbar Darouie, Enayatollah Bakhshi; Supervision: Akbar Darouie, Enayatollah Bakhshi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the people who shared their assistance in fulfilling this study; particularly the subjects' families.

References

- Packman A, Onslow M, Webber M, Harrison E, Arnott S, Bridgman K, et al. The Lidcombe program treatment guide [Internet]. 2015 [Updated 2015 January]. Available from: [Link]

- Ward D. Stuttering and cluttering frameworks for undrestanding and treatment. London: Psycology Press; 2008. [Link]

- World Health Organization (WHO). International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems 2016: 10th revision. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. [Link]

- Guitar B. Stuttering an integrated approach to its nature and treatment. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Link]

- Conture EG, Curlee RF. Stuttering and related disorders of fluency. Leipzig: Thieme; 2011. [Link]

- Ramig PR, Dodge D. The child and adolescent stuttering treatment & activity resource guide. Boston: Cengage Learning; 2009 [Link].

- Guitar B, McCauley RJ. Treatment of stuttering: Established and emerging interventions. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010. [Link]

- Lincoln M, Onslow M, Lewis C, Wilson L. A clinical trial of an operant treatment for school-age children who stutter. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology. 1996; 5(2):73-85. [DOI:10.1044/1058-0360.0502.73]

- Koushik S, Shenker R, Onslow M. Follow-up of 6-10-year-old stuttering children after Lidcombe program treatment: A Phase I trial. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 2009; 34(4):279-90. [DOI:10.1016/j.jfludis.2009.11.001] [PMID]

- Shafiei B, Hashemi F. [Identification of efficacy of Lidcombe program in reducing of the severity of stuttering in preschool children who stutter and their parent’s anxiety reduction (Persian)]. Middle Eastern Journal of Disability Studies. 2015; 5(1):29-38. [Link]

- Mashima PA, Doarn CR. Overview of telehealth activities in speech-language pathology. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2008; 14(10):1101-17. [DOI:10.1089/tmj.2008.0080] [PMID]

- Craig J, Patterson V. Introduction to the practice of telemedicine. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2005; 11(1):3-9. [DOI:10.1177/1357633X0501100102] [PMID]

- ASHA. Telepractice. Maryland: American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; 2014 [Link]

- Brown J. ASHA and the evolution of telepractice. Perspectives on Telepractice. 2011; 1(1):4-9.[Link]

- Bridgman K. Webcam delivery of the Lidcombe program for preschool children who stutter: A randomised controlled trial [PhD Disertation]. Sydney: The University of Sydney; 2014. [Link]

- Carey B, O’Brian S, Lowe R, Onslow M. Webcam delivery of the camperdown program for adolescents who stutter: A phase ii trial. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2014; 45(4):314-24. [DOI:10.1044/2014_LSHSS-13-0067] [PMID]

- Grogan-Johnson S, Gabel RM, Taylor J, Rowan LE, Alvares R, Schenker J. A pilot explor ation of speech sound disorder intervention delivered by telehealth to school-age children. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2011; 3(1):31-42. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2011.6064] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Howell S, Tripoliti E, Pring T. Delivering the Lee Silverman voice treatment (LSVT) by web camera: A feasibility study. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2009; 44(3):287-300. [DOI:10.1080/13682820802033968] [PMID]

- Sharma S, Ward EC, Burns C, Theodoros D, Russell T. Assessing swallowing disorders online: A pilot telerehabilitation study. Telemedicine and e-Health. 2011; 17(9):688-95. [DOI:10.1089/tmj.2011.0034] [PMID]

- Agostini M, Garzon M, Benavides-Varela S, De Pellegrin S, Bencini G, Rossi G, et al. Telerehabilitation in poststroke anomia. BioMed Research International. 2014; 2014. [DOI:10.1155/2014/706909] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Carey B, O’Brian S, Onslow M, Packman A, Menzies R. Webcam delivery of the Camperdown program for adolescents who stutter: A Phase I trial. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools. 2012; 43(3):370-80. [DOI:10.1044/0161-1461(2011/11-0010)] [PMID]

- Claude Sicotte PL, Julie Fortier-Blanc, Leblanc Y. Feasibility and outcome evaluation of a telemedicine application in speech-language pathology. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2003; 9:253-8. [DOI:10.1258/135763303769211256] [PMID]

- O’Brian S, Packman A, Onslow M. Telehealth delivery of the Camperdown program for adults who stutter: A phase I trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2008; 51(1):184-95. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2008/014)] [PMID]

- O’Brian S, Smith K, Onslow M. Webcam delivery of the Lidcombe Program for early stuttering: A phase I clinical trial. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2014; 57(3):825-30. [DOI:10.1044/2014_JSLHR-S-13-0094] [PMID]

- Valentine DT. Stuttering intervention in three service delivery models (direct, hybrid, and telepractice): Two case studies. International Journal of Telerehabilitation. 2014; 6(2):51. [DOI:10.5195/ijt.2014.6154] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Theodoros D. Telepractice in speech-language pathology: The evidence, the challenges, and the future. SIG 18 Perspectives on Telepractice. 2011; 1(1):10-21. [DOI:10.1044/tele1.1.10]

- Jones M, Onslow M, Packman A, O’Brian S, Hearne A, Williams S, et al. Extended follow up of a randomized controlled trial of the Lidcombe program of early stuttering intervention. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2008; 43(6):649-61. [DOI:10.1080/13682820801895599] [PMID]

- Onslow M, Packman A, Harrison RE.The lidcombe program of early stuttering intervention: A clinician’s guide. Austin: Macquarie University; 2003. [Link]

- Vong E, Wilson L, Lincoln M. The Lidcombe program of early stuttering intervention for malaysian families: Four case studies. Journal of Fluency Disorders. 2016; 49:29-39. [DOI:10.1016/j.jfludis.2016.07.003] [PMID]

- Kingston M, Huber A, Onslow M, Jones M, Packman A. Predicting treatment time with the Lidcombe program: Replication and meta-analysis. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2003; 38(2):165-77. [DOI:10.1080/1368282031000062882] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Speech & Language Pathology

Received: 6/05/2021 | Accepted: 18/10/2021 | Published: 12/07/2022

Received: 6/05/2021 | Accepted: 18/10/2021 | Published: 12/07/2022

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)