Volume 24, Issue 1 (Spring 2023)

jrehab 2023, 24(1): 42-55 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Mashaherifard M B, Motififard M, taheri N. The Effect of Knee Joint Muscles Deep Dry Needling on Pain and Function in Patients After Total Knee Arthroplasty. jrehab 2023; 24 (1) :42-55

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2799-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2799-en.html

1- Department of Physical Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran., 1038 roknedoleh ave. bozorgmehr str. esfahan

2- Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran., Department of orthopedy, Faculty of medical, ,Isfahan medical university,Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Physical Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,n_taheri@rehab.mui.ac.ir

2- Department of Orthopedic Surgery, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran., Department of orthopedy, Faculty of medical, ,Isfahan medical university,Isfahan, Iran.

3- Department of Physical Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 2217 kb]

(1563 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (4956 Views)

Full-Text: (2604 Views)

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis is one of the most common diseases of this joint, and 15.5% of people in Iran suffer from this problem [1]. Knee osteoarthritis is a multifactorial, inflammatory, and destructive joint disorder that involves synovial tissues and articular cartilage [2] and causes permanent pain, functional limitation, and low quality of life (QoL) [3]. Knee osteoarthritis management aims to control pain and improve the patient’s QoL [4].

Total knee arthroplasty is a common surgery to reduce pain and improve the function of people who suffer from this disease [3]. The presence of pain after total knee arthroplasty is a major concern, which is severe in 60% of cases and moderate in 30% of patients [5], reducing the QoL of these people [6]. One of the most important goals of this surgery is to reduce pain, improve function, and increase the QoL of these patients [7]. Some causes of permanent pain after total knee arthroplasty include infection, improper function of mechanical components, sympathetic pain syndromes, nerve entrapment, and musculoskeletal pain [8]. In Hoffman’s algorithm, which investigates the causes of pain after total knee arthroplasty, musculoskeletal pain or extra-articular pain ranks as the tenth cause of pain [9]. One of the causes of musculoskeletal pain is active trigger points, which play a significant role in the occurrence of pain after total knee arthroplasty because it seems that surgery or stress activates trigger points in these patients [10].

In general, trigger points are the common causes of musculoskeletal pain, and the prevalence of pain resulting from these trigger points is very high in all patients with chronic pain [11]. About 95% to 85% of patients are in the pain clinic [12]. Various methods to disable trigger points include ultrasonic waves, ischemic pressure, cold spray, stretch, laser, oral drugs, local anesthetic injection, and superficial and deep dry needling [13].

The exact mechanism of action of dry needling is still unclear. However, mechanisms such as disruption of the end plate, change in length, the tension of muscle fibers, stimulation of mechanical receptors, increase in blood flow, and the release of intravenous painkillers affect central and peripheral sensitivity, change the chemical environment around active trigger points and as a result, improves tissue function, mechanical correction, and tissue repair [14, 15]. Deep dry needling, as a simple and effective method, is widely used in physiotherapy clinics, and in this way, patients spend less time and money [16]. In Henry’s study, the effect of dry needling on the muscles around the knee in patients on the waiting list for knee arthroplasty reduced their pain [11].

Due to the lack of studies investigating the effect of dry needling on knee arthroplasty patients, this study investigated the effect of a dry needling session on the pain and function of patients who had at least three months of knee arthroplasty with active trigger points in the muscles around the knee.

Materials and Methods

This research was a before-and-after clinical trial study conducted from October 2017 to September 2018 at a private physiotherapy center in Isfahan City, Iran. A total of 49 patients undergoing knee arthroplasty for at least 3 months participated in the study after considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria by an orthopedic doctor. Then, the first researcher, a physiotherapist with 15 years of experience, evaluated the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the presence of active trigger points in the muscles around the knee, including the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocsoleus [11]. A total of 27 patients were eligible, and two refused to cooperate due to the fear of dry needling. Finally, 25 patients were included in the study.

The inclusion criteria for the study included the age range of 55 to 80 years, the ability to read and write, having the full extension range of the knee, having a pain level above 40 mm on the linear visual analog scale (VAS) and the presence of active trigger points in the muscles around the knee, including the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocsoleus based on the Travel and Simon evaluation index [10, 11, 15].

The presence of 3 of the 4 Travel and Simon evaluation indicators was mandatory as follows:

1- The presence of a tight band inside the muscle during the manual examination,

2- High sensitivity or painfulness of points to manual touch,

3- Re-feeling the previously referred pain by pressing the points, and

4- Creating a local contraction due to squeezing between two fingers.

Patients who had at least one and at most two active trigger points were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were the presence of referred back pain, neuropathy, fibromyalgia, hypothyroidism, meralgia, paresthesia, systemic or coagulation diseases, malignant diseases, myopathy, fear of needles, use of blood anticoagulants or painkillers, performing hip joint arthroplasty in the same side, total knee arthroplasty on the opposite side less than 6 months ago, and problems in surgical techniques [10, 12].

After evaluating the active trigger points of the muscles around the knee by the first researcher, the patients completed the ethical consent form to participate in the study. They completed the background information questionnaire, including age, height, and weight. It should be noted that the second researcher, a physiotherapist with 15 years of work experience and 6 years of experience in dry needling, performed needling on the active trigger points of the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocsoleus muscles.

The knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS) questionnaire, whose validity and reliability have already been checked and proven, was used to assess the patients’ performance [17].

The performance score of the patients in this questionnaire ranges from a minimum of 0 (the worst situation) to a maximum of 100 (no problem).

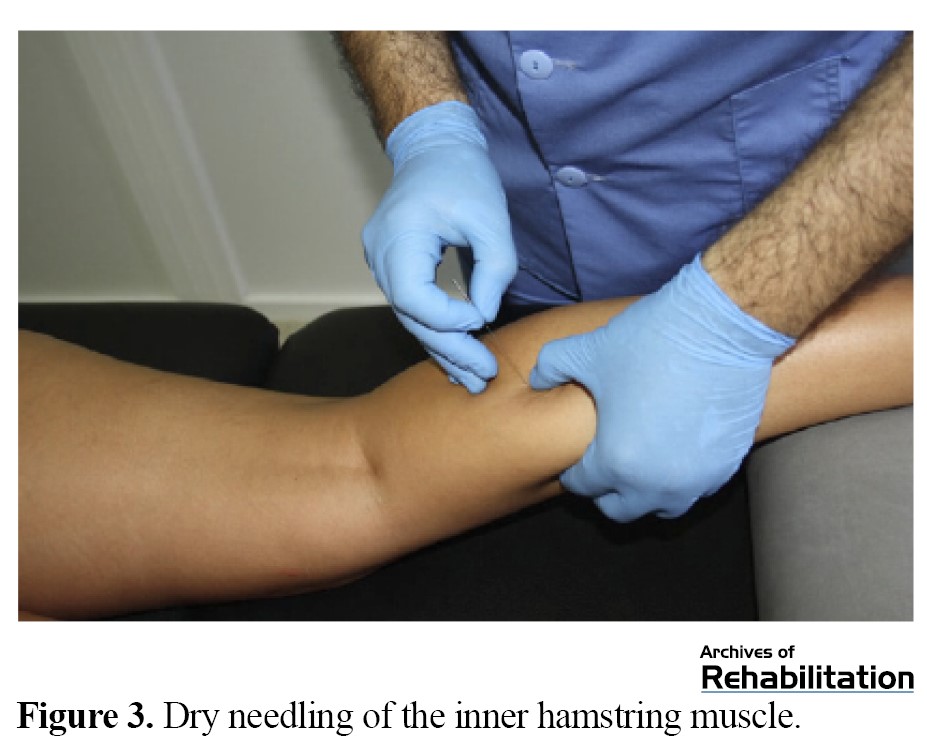

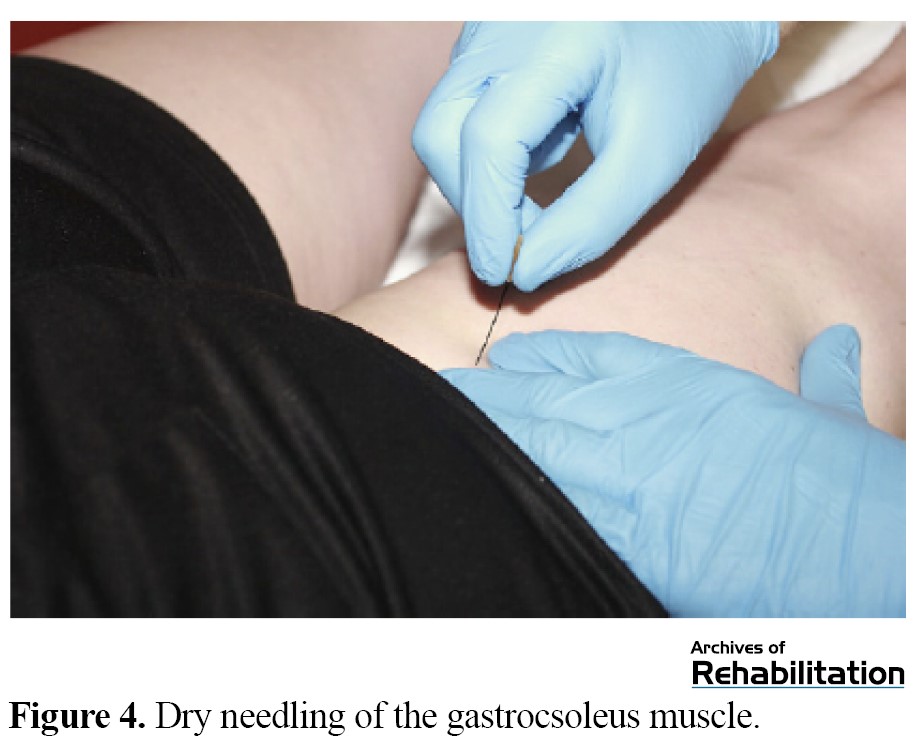

The pain intensity was measured using a linear VAS, and the patients were asked to indicate their current pain level on a graded ruler, ranging from 0 to 100 mm [10]. For needling the quadriceps muscles, the patient lies down, and a pillow is put under his or her knee so that it is slightly bent (Figure 1). To needle the hamstring muscles, the patient lies on his stomach, and a pillow is placed under the ankle [18] (Figures 2 and 3). For needling the gastrocsoleus muscles, the patient lies on his stomach as before, and a pillow is placed under the ankles [18] (Figure 4). In all cases, the patients were needled by Hong’s fast-in and fast-out method with a needle with a diameter of 0.3 mm and a length of 5 cm with a frequency of 1 Hz and 10 times back and forth [12]. One week and one month after dry needling, the pain was measured and recorded using the VAS, and the patients’ performance using the KOOS questionnaire.

It should be noted that in this study, the patients with pain inside the knee had the most active trigger points in the internal vastus muscles and the medial head of the gastrocsoleus muscle and the patients with more pain outside the knee had active trigger points in the external vastus muscles and the external head of the gastrocsoleus muscle.

The normal distribution of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To analyze the data, repeated measure analysis of variance test with was performed in SPSS20 software, version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

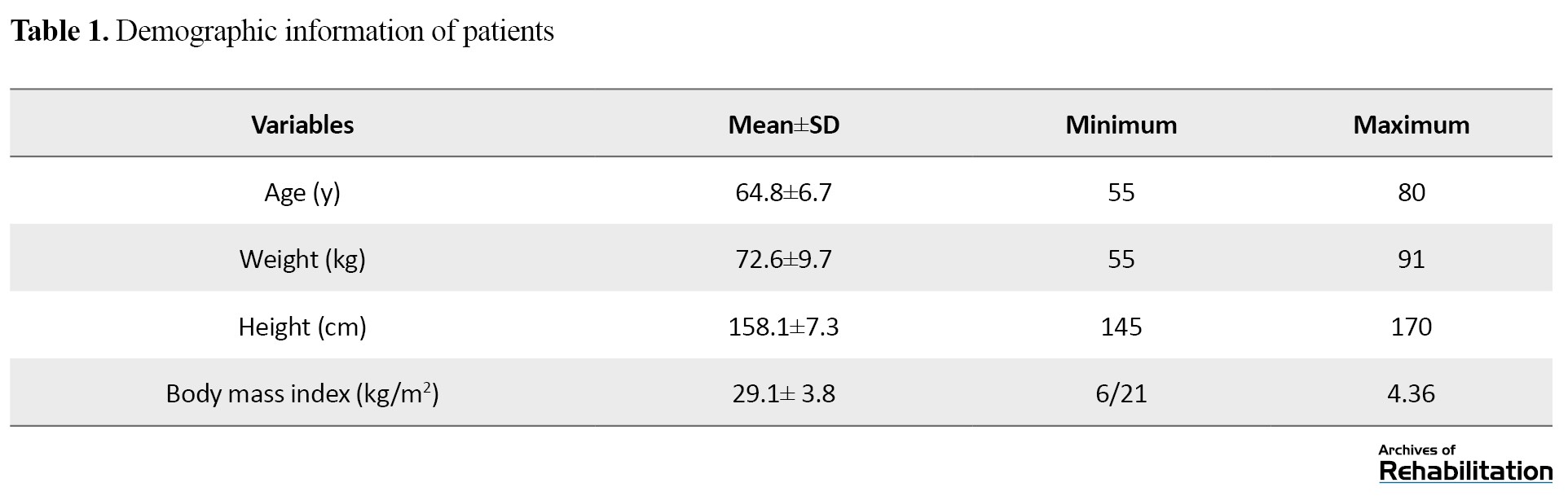

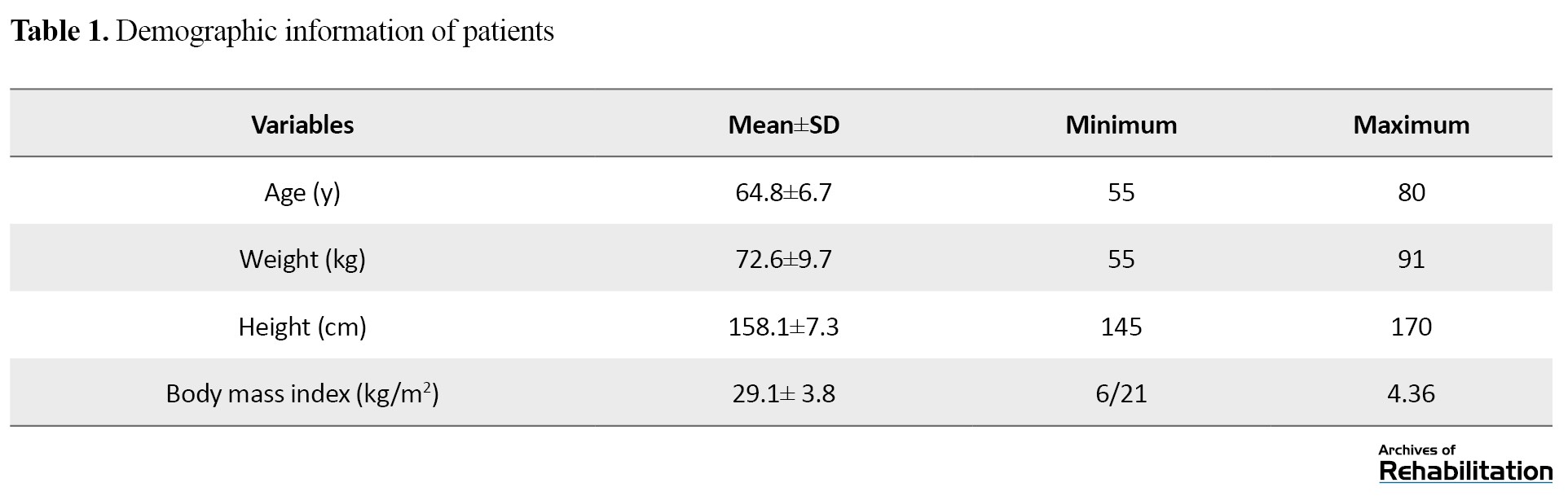

The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the distribution of height, weight, age, and body mass index variables follows the normal distribution (P<0.05). The demographic information of patients is shown in Table 1.

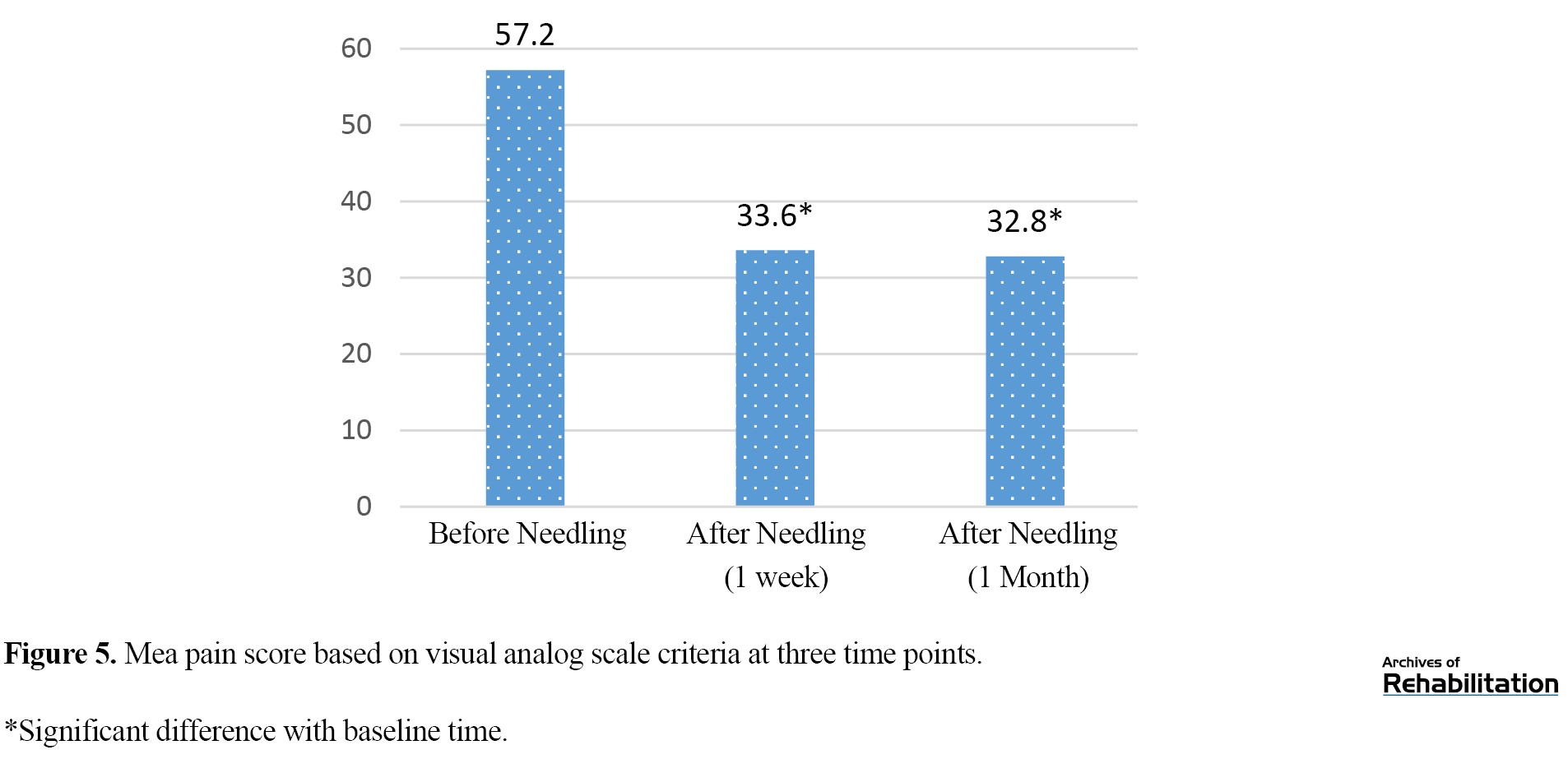

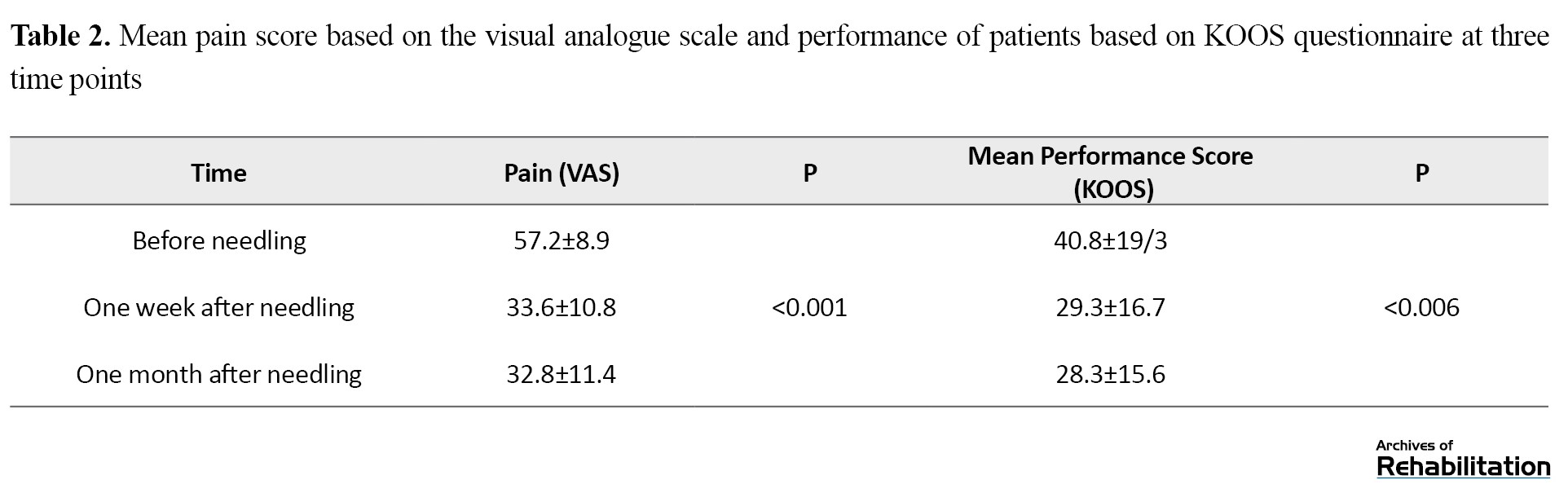

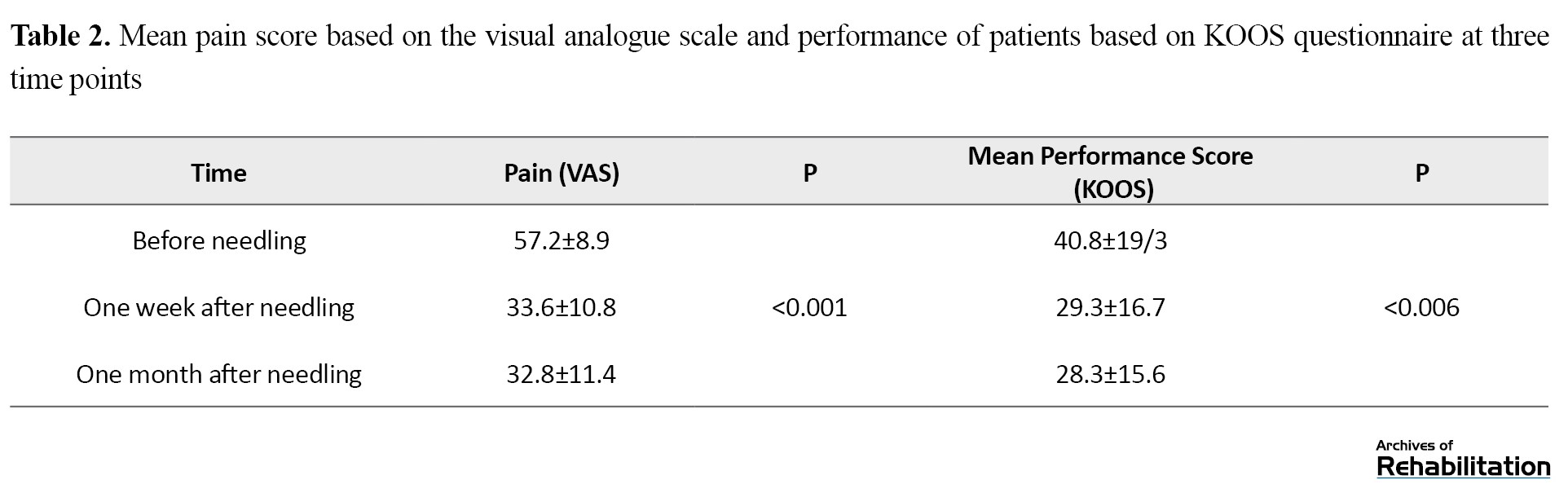

Repeated measure analysis of variance showed that the mean pain score based on VAS criteria had a significant difference (P<0.001) between three time points: before needling, one week, and one month after needling. The least significant difference post hoc test showed that the mean pain score based on the VAS between the time points of before needling and one week later was significant, and it was also significant (P<0.001) between the time before needling and one month later. There was no significant difference (P=0.16) (Table 2) between one week later and one month later (Figure 5).

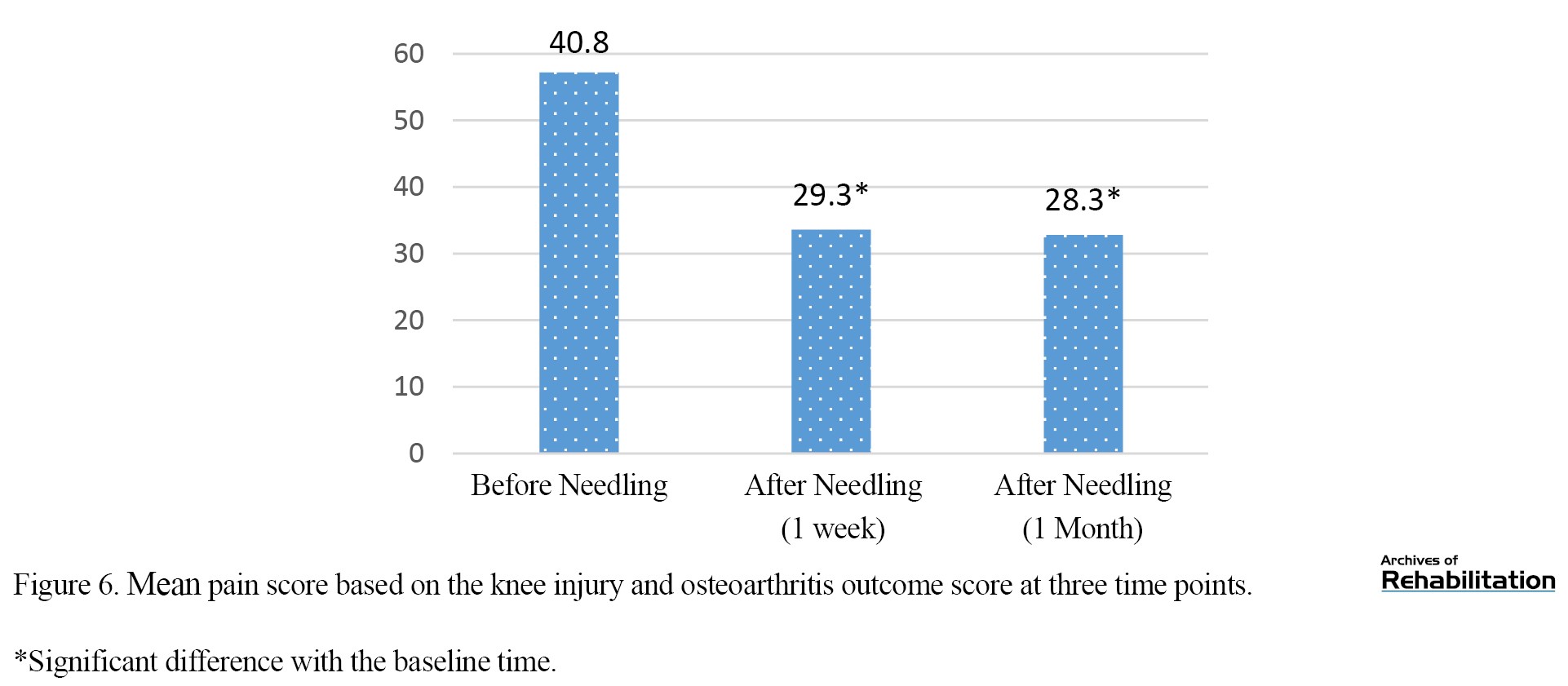

Repeated measures analysis of variance showed that the mean performance based on the KOOS questionnaire had a significant difference between the three time points (P=0.006). The least significant difference post hoc test showed that the mean performance score after one week (P=0.002) and after one month of needling (P=0.001) was significantly lower than before needling, but there was no significant difference (P=0.43) between after one week and after one month of needling (Table 2) (Figure 6). Discussion

This study showed that performing one session of dry needling reduces pain and improves patients’ performance after one week and one month after needling. Based on the VAS, the mean pain level decreased from 23.6 after one week of dry needling to 24.4 one month after the intervention. The performance score of the patients improved on mean by 11.3 one week after dry needling and 12.3 one month after the intervention.

The results of the present study concerning the reduction of pain after dry needling were in line with Feinberg et al. Their study investigated the effect of manual therapy and needling on active trigger points on permanent pain after total knee arthroplasty [8]. This study reached the same results as Mayoral et al. In their research, dry needle injection was performed before surgery in the active trigger points of total knee arthroplasty patients [10]. Mayoral et al. used another questionnaire in addition to VAS. In another study, Imanura et al. investigated the effect of a dry needling session on active trigger points of patients on the waiting list for total hip arthroplasty. In their study, as in the present study, the reports indicated a reduction in patients’ pain [17]. Imanura et al. used VAS in pain assessment. In a study by Ryeon Kim et al. examining the effects of physiotherapy and acupuncture in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery [18], the patient’s performance was improved based on the KOOS questionnaire. In the present study, the performance of the patients was also enhanced based on the KOOS questionnaire. Epsi Lopez et al. reported the reduction of pain in patients with patellofemoral syndrome after performing 3 sessions of dry needling and muscle strengthening consistent with the results of this study [19].

Although the method of dry needling and its function has not yet been fully understood, mechanisms such as disruption of the end plate, change in length, the tension of muscle fibers, stimulation of mechanical receptors, increase in blood flow, release of endogenous painkillers that affect central and peripheral sensitivity [20, 21], modifying the chemical environment around active trigger points as a result of improving tissue function, mechanical correction, and tissue repair are considered contributing factors [14, 15, 22]. In addition, some researchers have considered the two factors of increasing blood flow around the trigger points and mechanical effects that lead to correcting the length of sarcomeres in the affected area. The effect of dry needling can be examined from two mechanical and neurophysiological aspects. For example, a disruption in the contraction group or an increase in the sarcomere length is a mechanical mechanism. The reduction of input data and the activation of central pain fibers are examples of neurophysiological mechanisms. In Hoffman’s algorithm, one of the causes of pain after total knee arthroplasty is extra-articular conflicts and musculoskeletal problems. Active trigger points are the most common causes of musculoskeletal pain, which can be initiated by excessive pressure on the muscle as a result of acute trauma, acute strain, fracture, surgery, or repetitive activities that put abnormal pressure on a group of muscles and cause motor control disorders and muscle fatigue in patients undergoing complete knee arthroplasty with activated trigger points in the muscles around their knee due to pain or surgical stress. Performing one dry needling session reduces pain and improves performance. The study results showed no significant difference between one week and one month in pain and function items; the effects of dry needling reached their maximum effect in one week.

One of the limitations of this study is that it was done as a before and after clinical trial study. Because no study in this field was found in the databases, we did not know the number of samples, and it was impossible to predict the number of controls. For these reasons, conducting a randomized clinical trial study was impossible. Other study limitations were limited access to required patients, fear of dry needling, and patients’ unwillingness to participate. Having a control group with longer follow-ups, performing therapeutic exercises, stretching, dry needling, and performing therapeutic sessions are more suggestions for future studies.

Conclusion

The present study showed that performing one session of dry needling on active trigger points in the muscles around the knee in patients at least three months after their total knee arthroplasty reduces pain and increases their performance in one week and one month after the intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUI.REC 1396.3.471). In this study, written consent was obtained from all the patients. At first, the patients were fully informed about the plan’s implementation process, and they were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time, and their information remained completely confidential.

Funding

This article is taken from the master’s thesis of Mohammad Bagher Mashaharifard, at the Department of Physiotherapy, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. It should be noted that has been registered in the Research Assistant System of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences with project No.: 396471.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, and writing – review & editing: All authors; Supervision, investigation, data analysi: Navid Taheri and Mohammad Bagher Mashaherifard; Data collection, funding acquisition and resources: Mohammad Bagher Mashaherifard.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Knee osteoarthritis is one of the most common diseases of this joint, and 15.5% of people in Iran suffer from this problem [1]. Knee osteoarthritis is a multifactorial, inflammatory, and destructive joint disorder that involves synovial tissues and articular cartilage [2] and causes permanent pain, functional limitation, and low quality of life (QoL) [3]. Knee osteoarthritis management aims to control pain and improve the patient’s QoL [4].

Total knee arthroplasty is a common surgery to reduce pain and improve the function of people who suffer from this disease [3]. The presence of pain after total knee arthroplasty is a major concern, which is severe in 60% of cases and moderate in 30% of patients [5], reducing the QoL of these people [6]. One of the most important goals of this surgery is to reduce pain, improve function, and increase the QoL of these patients [7]. Some causes of permanent pain after total knee arthroplasty include infection, improper function of mechanical components, sympathetic pain syndromes, nerve entrapment, and musculoskeletal pain [8]. In Hoffman’s algorithm, which investigates the causes of pain after total knee arthroplasty, musculoskeletal pain or extra-articular pain ranks as the tenth cause of pain [9]. One of the causes of musculoskeletal pain is active trigger points, which play a significant role in the occurrence of pain after total knee arthroplasty because it seems that surgery or stress activates trigger points in these patients [10].

In general, trigger points are the common causes of musculoskeletal pain, and the prevalence of pain resulting from these trigger points is very high in all patients with chronic pain [11]. About 95% to 85% of patients are in the pain clinic [12]. Various methods to disable trigger points include ultrasonic waves, ischemic pressure, cold spray, stretch, laser, oral drugs, local anesthetic injection, and superficial and deep dry needling [13].

The exact mechanism of action of dry needling is still unclear. However, mechanisms such as disruption of the end plate, change in length, the tension of muscle fibers, stimulation of mechanical receptors, increase in blood flow, and the release of intravenous painkillers affect central and peripheral sensitivity, change the chemical environment around active trigger points and as a result, improves tissue function, mechanical correction, and tissue repair [14, 15]. Deep dry needling, as a simple and effective method, is widely used in physiotherapy clinics, and in this way, patients spend less time and money [16]. In Henry’s study, the effect of dry needling on the muscles around the knee in patients on the waiting list for knee arthroplasty reduced their pain [11].

Due to the lack of studies investigating the effect of dry needling on knee arthroplasty patients, this study investigated the effect of a dry needling session on the pain and function of patients who had at least three months of knee arthroplasty with active trigger points in the muscles around the knee.

Materials and Methods

This research was a before-and-after clinical trial study conducted from October 2017 to September 2018 at a private physiotherapy center in Isfahan City, Iran. A total of 49 patients undergoing knee arthroplasty for at least 3 months participated in the study after considering the inclusion and exclusion criteria by an orthopedic doctor. Then, the first researcher, a physiotherapist with 15 years of experience, evaluated the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the presence of active trigger points in the muscles around the knee, including the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocsoleus [11]. A total of 27 patients were eligible, and two refused to cooperate due to the fear of dry needling. Finally, 25 patients were included in the study.

The inclusion criteria for the study included the age range of 55 to 80 years, the ability to read and write, having the full extension range of the knee, having a pain level above 40 mm on the linear visual analog scale (VAS) and the presence of active trigger points in the muscles around the knee, including the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocsoleus based on the Travel and Simon evaluation index [10, 11, 15].

The presence of 3 of the 4 Travel and Simon evaluation indicators was mandatory as follows:

1- The presence of a tight band inside the muscle during the manual examination,

2- High sensitivity or painfulness of points to manual touch,

3- Re-feeling the previously referred pain by pressing the points, and

4- Creating a local contraction due to squeezing between two fingers.

Patients who had at least one and at most two active trigger points were included in the study. The exclusion criteria were the presence of referred back pain, neuropathy, fibromyalgia, hypothyroidism, meralgia, paresthesia, systemic or coagulation diseases, malignant diseases, myopathy, fear of needles, use of blood anticoagulants or painkillers, performing hip joint arthroplasty in the same side, total knee arthroplasty on the opposite side less than 6 months ago, and problems in surgical techniques [10, 12].

After evaluating the active trigger points of the muscles around the knee by the first researcher, the patients completed the ethical consent form to participate in the study. They completed the background information questionnaire, including age, height, and weight. It should be noted that the second researcher, a physiotherapist with 15 years of work experience and 6 years of experience in dry needling, performed needling on the active trigger points of the quadriceps, hamstrings, and gastrocsoleus muscles.

The knee injury and osteoarthritis outcome score (KOOS) questionnaire, whose validity and reliability have already been checked and proven, was used to assess the patients’ performance [17].

The performance score of the patients in this questionnaire ranges from a minimum of 0 (the worst situation) to a maximum of 100 (no problem).

The pain intensity was measured using a linear VAS, and the patients were asked to indicate their current pain level on a graded ruler, ranging from 0 to 100 mm [10]. For needling the quadriceps muscles, the patient lies down, and a pillow is put under his or her knee so that it is slightly bent (Figure 1). To needle the hamstring muscles, the patient lies on his stomach, and a pillow is placed under the ankle [18] (Figures 2 and 3). For needling the gastrocsoleus muscles, the patient lies on his stomach as before, and a pillow is placed under the ankles [18] (Figure 4). In all cases, the patients were needled by Hong’s fast-in and fast-out method with a needle with a diameter of 0.3 mm and a length of 5 cm with a frequency of 1 Hz and 10 times back and forth [12]. One week and one month after dry needling, the pain was measured and recorded using the VAS, and the patients’ performance using the KOOS questionnaire.

It should be noted that in this study, the patients with pain inside the knee had the most active trigger points in the internal vastus muscles and the medial head of the gastrocsoleus muscle and the patients with more pain outside the knee had active trigger points in the external vastus muscles and the external head of the gastrocsoleus muscle.

The normal distribution of the data was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To analyze the data, repeated measure analysis of variance test with was performed in SPSS20 software, version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

The results of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test showed that the distribution of height, weight, age, and body mass index variables follows the normal distribution (P<0.05). The demographic information of patients is shown in Table 1.

Repeated measure analysis of variance showed that the mean pain score based on VAS criteria had a significant difference (P<0.001) between three time points: before needling, one week, and one month after needling. The least significant difference post hoc test showed that the mean pain score based on the VAS between the time points of before needling and one week later was significant, and it was also significant (P<0.001) between the time before needling and one month later. There was no significant difference (P=0.16) (Table 2) between one week later and one month later (Figure 5).

Repeated measures analysis of variance showed that the mean performance based on the KOOS questionnaire had a significant difference between the three time points (P=0.006). The least significant difference post hoc test showed that the mean performance score after one week (P=0.002) and after one month of needling (P=0.001) was significantly lower than before needling, but there was no significant difference (P=0.43) between after one week and after one month of needling (Table 2) (Figure 6). Discussion

This study showed that performing one session of dry needling reduces pain and improves patients’ performance after one week and one month after needling. Based on the VAS, the mean pain level decreased from 23.6 after one week of dry needling to 24.4 one month after the intervention. The performance score of the patients improved on mean by 11.3 one week after dry needling and 12.3 one month after the intervention.

The results of the present study concerning the reduction of pain after dry needling were in line with Feinberg et al. Their study investigated the effect of manual therapy and needling on active trigger points on permanent pain after total knee arthroplasty [8]. This study reached the same results as Mayoral et al. In their research, dry needle injection was performed before surgery in the active trigger points of total knee arthroplasty patients [10]. Mayoral et al. used another questionnaire in addition to VAS. In another study, Imanura et al. investigated the effect of a dry needling session on active trigger points of patients on the waiting list for total hip arthroplasty. In their study, as in the present study, the reports indicated a reduction in patients’ pain [17]. Imanura et al. used VAS in pain assessment. In a study by Ryeon Kim et al. examining the effects of physiotherapy and acupuncture in patients after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery [18], the patient’s performance was improved based on the KOOS questionnaire. In the present study, the performance of the patients was also enhanced based on the KOOS questionnaire. Epsi Lopez et al. reported the reduction of pain in patients with patellofemoral syndrome after performing 3 sessions of dry needling and muscle strengthening consistent with the results of this study [19].

Although the method of dry needling and its function has not yet been fully understood, mechanisms such as disruption of the end plate, change in length, the tension of muscle fibers, stimulation of mechanical receptors, increase in blood flow, release of endogenous painkillers that affect central and peripheral sensitivity [20, 21], modifying the chemical environment around active trigger points as a result of improving tissue function, mechanical correction, and tissue repair are considered contributing factors [14, 15, 22]. In addition, some researchers have considered the two factors of increasing blood flow around the trigger points and mechanical effects that lead to correcting the length of sarcomeres in the affected area. The effect of dry needling can be examined from two mechanical and neurophysiological aspects. For example, a disruption in the contraction group or an increase in the sarcomere length is a mechanical mechanism. The reduction of input data and the activation of central pain fibers are examples of neurophysiological mechanisms. In Hoffman’s algorithm, one of the causes of pain after total knee arthroplasty is extra-articular conflicts and musculoskeletal problems. Active trigger points are the most common causes of musculoskeletal pain, which can be initiated by excessive pressure on the muscle as a result of acute trauma, acute strain, fracture, surgery, or repetitive activities that put abnormal pressure on a group of muscles and cause motor control disorders and muscle fatigue in patients undergoing complete knee arthroplasty with activated trigger points in the muscles around their knee due to pain or surgical stress. Performing one dry needling session reduces pain and improves performance. The study results showed no significant difference between one week and one month in pain and function items; the effects of dry needling reached their maximum effect in one week.

One of the limitations of this study is that it was done as a before and after clinical trial study. Because no study in this field was found in the databases, we did not know the number of samples, and it was impossible to predict the number of controls. For these reasons, conducting a randomized clinical trial study was impossible. Other study limitations were limited access to required patients, fear of dry needling, and patients’ unwillingness to participate. Having a control group with longer follow-ups, performing therapeutic exercises, stretching, dry needling, and performing therapeutic sessions are more suggestions for future studies.

Conclusion

The present study showed that performing one session of dry needling on active trigger points in the muscles around the knee in patients at least three months after their total knee arthroplasty reduces pain and increases their performance in one week and one month after the intervention.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: IR.MUI.REC 1396.3.471). In this study, written consent was obtained from all the patients. At first, the patients were fully informed about the plan’s implementation process, and they were allowed to withdraw from the study at any time, and their information remained completely confidential.

Funding

This article is taken from the master’s thesis of Mohammad Bagher Mashaharifard, at the Department of Physiotherapy, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. It should be noted that has been registered in the Research Assistant System of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences with project No.: 396471.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, writing-original draft, and writing – review & editing: All authors; Supervision, investigation, data analysi: Navid Taheri and Mohammad Bagher Mashaherifard; Data collection, funding acquisition and resources: Mohammad Bagher Mashaherifard.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Davatchi F, Sandoughi M, Moghimi N, Jamshidi AR, Tehrani Banihashemi A, Zakeri Z, et al. Epidemiology of rheumatic diseases in Iran from analysis of four COPCORD studies. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2016; 19(11):1056-62. [DOI:10.1111/1756-185X.12809] [PMID]

- Minafra L, Bravatà V, Saporito M, Cammarata FP, Forte GI, Caldarella S, et al. Genetic, clinical and radiographic signs in knee osteoarthritis susceptibility. Arthritis Research & Therapy. 2014; 16(2):R91. [DOI:10.1186/ar4535] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Petterson SC, Mizner RL, Stevens JE, Raisis L, Bodenstab A, Newcomb W, et al. Improved function from progressive strengthening interventions after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized clinical trial with an imbedded prospective cohort. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2009; 61(2):174-83. [DOI:10.1002/art.24167] [PMID]

- Jinks C, Jordan K, Croft P. Measuring the population impact of knee pain and disability with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC). Pain. 2002; 100(1):55-64. [DOI:10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00239-7] [PMID]

- Singelyn FJ, Deyaert M, Joris D, Pendeville E, Gouverneur J. Effects of intravenous patient-controlled analgesia with morphine, continuous epidural analgesia, and continuous three-in-one block on postoperative pain and knee rehabilitation after unilateral total knee arthroplasty. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 1998; 87(1):88-92. [DOI:10.1097/00000539-199807000-00019] [PMID]

- Herrero-Sánchez MD, García-Iñigo Mdel C, Nuño-Beato-Redondo BS, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Alburquerque-Sendín F. Association between ongoing pain intensity, health-related quality of life, disability and quality of sleep in elderly people with total knee arthroplasty. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2014; 19(6):1881-8. [DOI:10.1590/1413-81232014196.04632013] [PMID]

- Brander VA, Stulberg SD, Adams AD, Harden RN, Bruehl S, Stanos SP, et al. Predicting total knee replacement pain: A prospective, observational study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2003; 416:27-36. [DOI:10.1097/01.blo.0000092983.12414.e9] [PMID]

- Feinberg BI, Feinberg RA. Persistent pain after total knee arthroplasty: Treatment with manual therapy and trigger point injections. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain. 1998; 6(4):85-95. [DOI:10.1300/J094v06n04_08]

- Hofmann S, Seitlinger G, Djahani O, Pietsch M. The painful knee after TKA: A diagnostic algorithm for failure analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011; 19(9):1442. [DOI:10.1007/s00167-011-1634-6] [PMID]

- Mayoral O, Salvat I, Martín MT, Martín S, Santiago J, Cotarelo J, et al. Efficacy of myofascial trigger point dry needling in the prevention of pain after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013; 2013:694941. [DOI:10.1155/2013/694941] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Henry R, Cahill CM, Wood G, Hroch J, Wilson R, Cupido T, et al. Myofascial pain in patients waitlisted for total knee arthroplasty. Pain Research and Management. 2012; 17(5):321-7. [DOI:10.1155/2012/547183] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ebrahimi R, Taheri N. [Pain, pressure pain threshold and disability following one session of dry needling in subjects with active trigger points in the upper trapezius muscle (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Rehabilitation Sciences. 2016; 12(2):76-81. [DOI:10.22122/jrrs.v12i2.2605]

- Edwards J, Knowles N. Superficial dry needling and active stretching in the treatment of myofascial pain-a randomised controlled trial. Acupuncture in Medicine. 2003; 21(3):80-6. [DOI:10.1136/aim.21.3.80] [PMID]

- Itoh K, Katsumi Y, Hirota S, Kitakoji H. Randomised trial of trigger point acupuncture compared with other acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2007; 15(3):172-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.ctim.2006.05.003] [PMID]

- Tough EA, White AR. Effectiveness of acupuncture/dry needling for myofascial trigger point pain. Physical Therapy Reviews. 2011; 16(2):147-54. [DOI:10.1179/1743288X11Y.0000000007]

- Liu L, Huang QM, Liu QG, Ye G, Bo CZ, Chen MJ, et al. Effectiveness of dry needling for myofascial trigger points associated with neck and shoulder pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2015; 96(5):944-55. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2014.12.015] [PMID]

- Imamura ST, Riberto M, Fischer AA, Imamura M, Kaziyama HHS, Teixeira MJ. Successful pain relief by treatment of myofascial components in patients with hip pathology scheduled for total hip replacement. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain. 1998; 6(1):73-89. [DOI:10.1300/J094v06n01_06]

- Kim HR, Choi YN, Kim SH, Kang HR, Lee YJ, Jung CY, et al. Korean medical therapy for knee pain after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. The Acupuncture. 2017; 34(1):67-79. [DOI:10.13045/acupunct.2017076]

- Espí-López GV, Serra-Añó P, Vicent-Ferrando J, Sánchez-Moreno-Giner M, Arias-Buría JL, Cleland J, et al. Effectiveness of inclusion of dry needling in a multimodal therapy program for patellofemoral pain: A randomized parallel-group trial. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 2017; 47(6):392-401. [DOI:10.2519/jospt.2017.7389] [PMID]

- Hong CZ. Lidocaine Injection versus dry needling to myofascial trigger point: The importance of the local twitch response. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 1994; 73(4):256-63. [DOI:10.1097/00002060-199407000-00006] [PMID]

- Morihisa R, Eskew J, McNamara A, Young J. Dry needling in subjects with muscular trigger points in the lower quarter: A systematic review. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2016;11(1):1-14. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Ga H, Choi JH, Park CH, Yoon HJ. Dry needling of trigger points with and without paraspinal needling in myofascial pain syndromes in elderly patients. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2007; 13(6):617-24. [DOI:10.1089/acm.2006.6371] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Physical Therapy

Received: 23/06/2020 | Accepted: 19/10/2022 | Published: 1/01/2023

Received: 23/06/2020 | Accepted: 19/10/2022 | Published: 1/01/2023

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |