Volume 21, Issue 4 (Winter 2021)

jrehab 2021, 21(4): 422-435 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Gharib M, Shayesteh Azar M, Vameghi R, Hosseini S A, Nobakht Z, Dalvand H. Relationship of Environmental Factors With Social Participation of Children With Cerebral Palsy Spastic Diplegia: A Preliminary Study. jrehab 2021; 21 (4) :422-435

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2778-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2778-en.html

Masoud Gharib1

, Masoud Shayesteh Azar2

, Masoud Shayesteh Azar2

, Roshanak Vameghi3

, Roshanak Vameghi3

, Seyed Ali Hosseini3

, Seyed Ali Hosseini3

, Zahra Nobakht3

, Zahra Nobakht3

, Hamid Dalvand *4

, Hamid Dalvand *4

, Masoud Shayesteh Azar2

, Masoud Shayesteh Azar2

, Roshanak Vameghi3

, Roshanak Vameghi3

, Seyed Ali Hosseini3

, Seyed Ali Hosseini3

, Zahra Nobakht3

, Zahra Nobakht3

, Hamid Dalvand *4

, Hamid Dalvand *4

1- Orthopedic Research Center, Mazandran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran., Emam Khomeini hospital, Orthopedic Research center, Mazandran University of Medical Sciences, sari, Iran.

2- Orthopedic Research Center, Mazandran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran., Orthopedic Research center, Mazandran University of Medical Sciences, sari, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neuro Rehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Pediatric Neuro rehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,hdalvand@sina.tums.ac.ir

2- Orthopedic Research Center, Mazandran University of Medical Sciences, Sari, Iran., Orthopedic Research center, Mazandran University of Medical Sciences, sari, Iran.

3- Pediatric Neuro Rehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran., Pediatric Neuro rehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran.

4- Department of Occupational Therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 4872 kb]

(2078 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5296 Views)

Full-Text: (3048 Views)

Introduction

erebral Palsy Spastic Diplegia (CPSD) is the most common childhood disability with a prevalence of 2-3 per 1000 live births [2]. Brain damage affects the growth and development and daily activities of children with CPSD throughout their lives and affects their social participation, too [3]. According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, Child and Youth version (ICF-CY), participation is defined as a person’s “involvement in a life situation” [4]. This classification considers the context in which the disabled person lives as an influential factor of participation. This context consists of personal factors such as personality and the way of coping with environmental issues and factors, including physical, social, and attitudinal [5]. Our environment is designed and built for healthy people, and the problems of people with mobility impairments are less considered in its design [6]. In general, the environment can be a facilitator or a barrier to participation [7]. Law et al. stated that cultural, economic, institutional, physical, social, and attitudinal factors in the environment could facilitate or hinder the participation of children with disabilities [8]. In examining the environmental factors, it is essential to consider issues such as access, provision, availability of resources, social support, and equality [9].

CPSD children’s participation is affected by factors such as the type of cerebral palsy, the degree of mental disability, epilepsy, and the ability to walk and communicate [5, 10]. Psychosocial pressures, financial problems, and inadequate service systems, as well as building design, lack of income, and access to special facilities can also affect CPSD children’s participation [11]. Mobility factors, transportation system, parental support, and others’ attitude towards CPSD children [12, 13, 14], as well as the type and severity of disease [15, 16], are some factors affecting the social participation of these children. Their participation is also influenced by their functional abilities, skills, interests, and family culture [16, 17]. According to the parents of CPSD children, the role of environmental factors such as provided services, assistance, and policies in non-participation are more critical than other factors [21]. Pashmdar Fard et al. reported the limited participation of children with CPSD in Iran and emphasized further studies in this field [22]. This study aimed to investigate the predictive effect of environmental factors on the social participation of children with CPSD.

Materials and Methods

This research is a cross-sectional study. The study population consists of all children with CPSD and their parents living in Tehran, Mazandaran, and Alborz provinces of Iran. Of them, 116 children and their parents were selected as study samples using a convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria were being 6-18 years old and having been diagnosed CPSD by a pediatric neurologist or based on the medical record, and those who have had botox injection or history of surgery at least in the past 6 months. The exclusion criteria were disorders such as hydrocephalus, blindness and deafness, and lack of parental cooperation. After declaring verbal consent, the written consent was obtained from the children and their parents. The Gross Motor Function Classification System-Expanded and Revised (GMFCS-E&R) classification system was used for children. It is based on spontaneous movement with an emphasis on sitting, transfers, and mobility [24]. The children’s cognitive level was classified according to the impairment form of the SPARCLE project in three sub-categories of IQ>70, IQ: 50-70, and IQ<50 [21]. In this form, the IQ is expressed based on ICD 10 [25].

In addition to recording demographic (gender and age) and medical characteristics (hearing, vision, history of seizures, cognitive level), parents of children completed the Life Habit (LIFE-H) questionnaire to assess social participation of children and the European Child Environment Questionnaire (ECEQ) to assess environmental factors. The SPARCLE group developed the ECEQ, too [26, 27]. The “need” of each item was scored as “0=not needed”, and “1=needed”. Also, “availability” of each item was scored as “0=needed and available” and “1=needed and not available” [28]. The LIFE-H was developed by Noreau et al. in Québec, Canada [29]. The items are scored from 0 (not performed) to 9 (performed) based on the difficulty and the need for assistance. Its total score ranges from 0 to 10 [29, 30].

To investigate the relationship of social participation with the subscales of ECEQ, we used the correlation test and interpreted it, according to Portney and Watkins, as excellent (>0.90), good (0.75-0.89), moderate (0.50-0.74), and poor (<0.50) correlation. The significant value for all cases was 0.05 [23]. The linear regression analysis was used to predict the impact of environmental factors (physical, social, and attitudinal environments) on participation rate based on the standard beta coefficient value and a significance level of 0.05.

Results

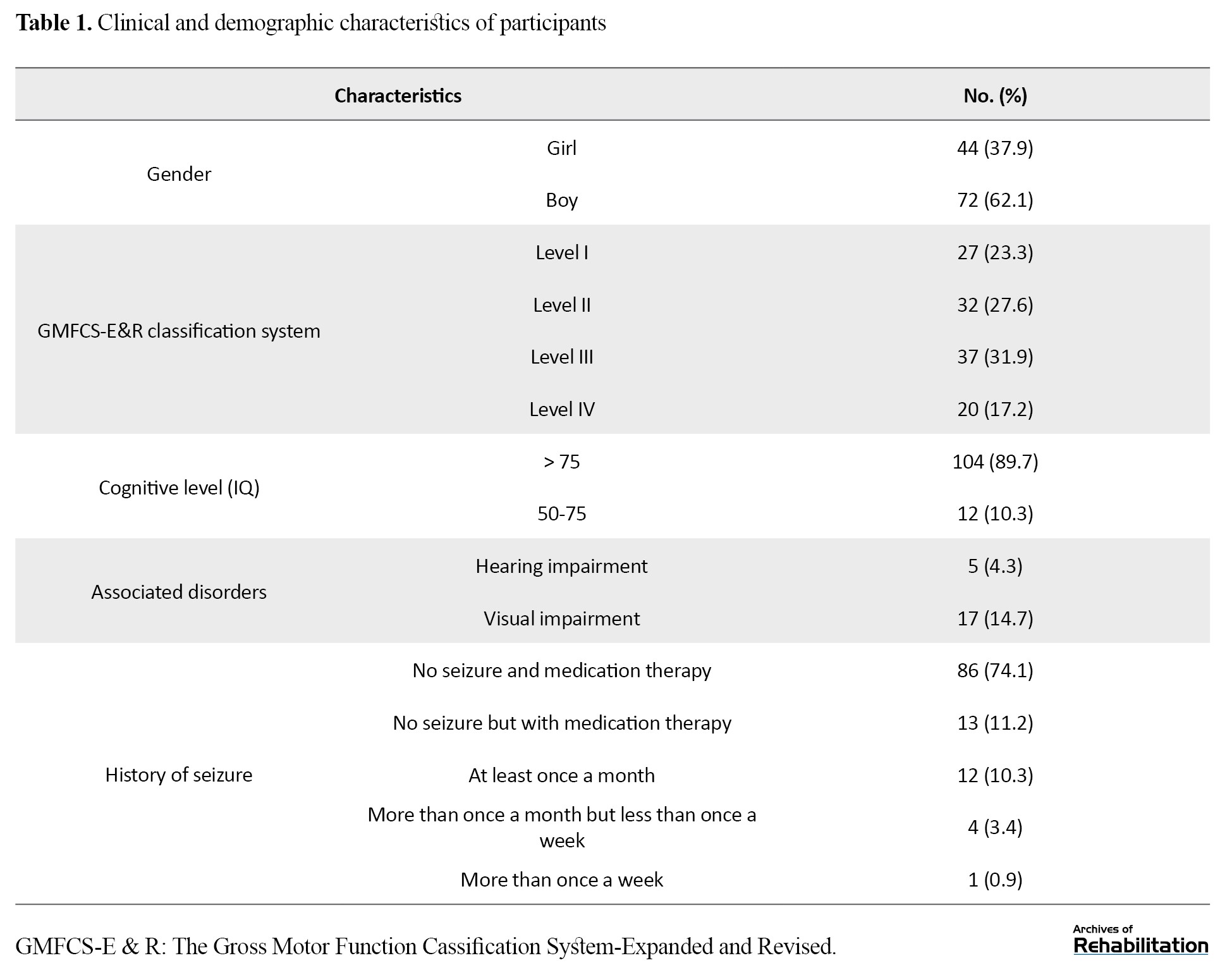

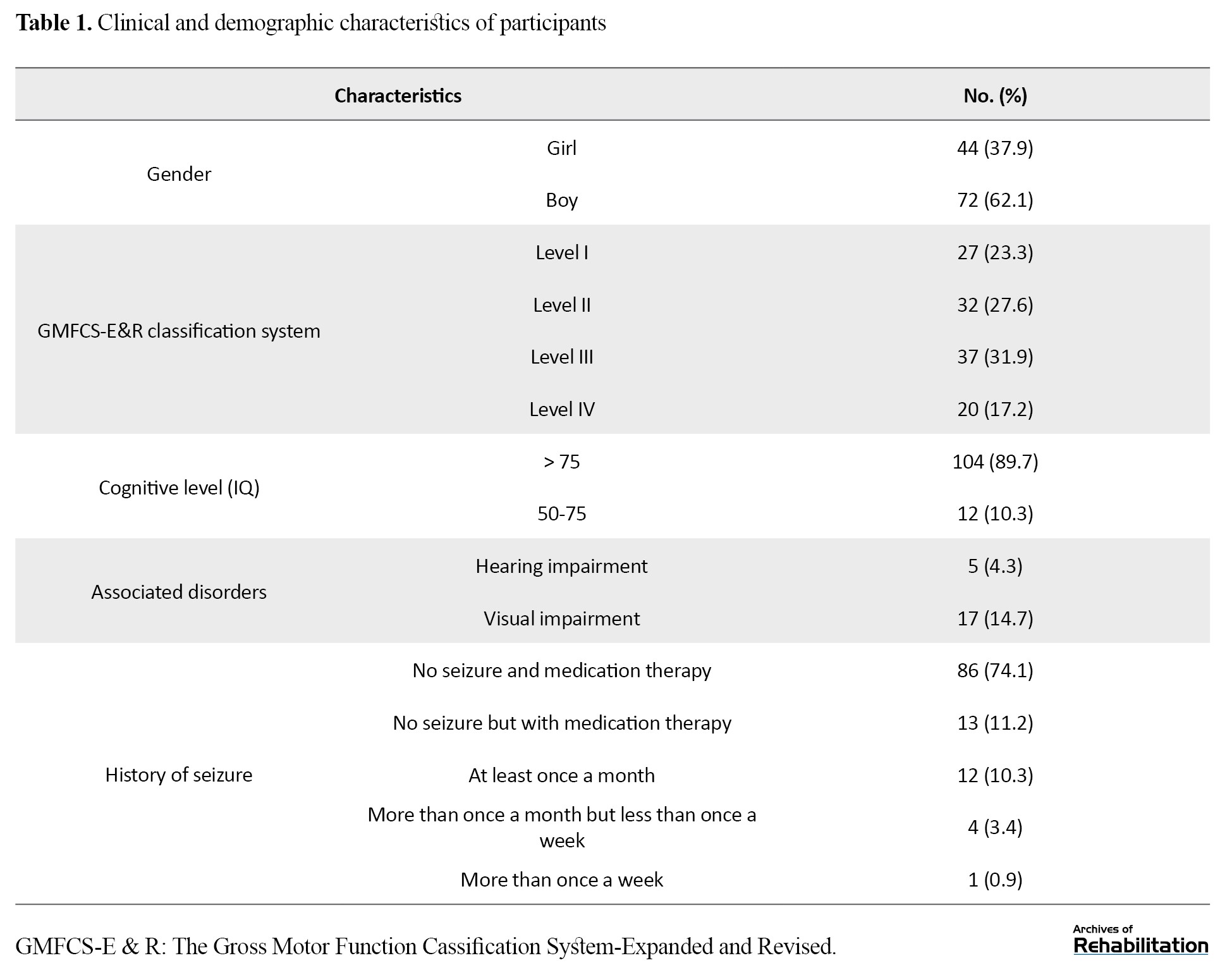

In this study, 116 children with CPSD aged 6-18 years with a Mean±SD age of 129.49±16.70 months (72 boys and 44 girls) participated. Also, 27 children (23.3%) were in category I, 32 (27.6%) in category II, 37 (31.9%) in category III, and 20 (17.2%) in category IV, according to the GMFCS-E&R classification system. Besides, 104 (89.7%) had an IQ above 75. Also, 4.3% and 14.7% of the children had visual and hearing impairment, respectively. Moreover, 85.3% had no seizures (Table 1).

According to Table 2, a good correlation with social participation was obtained for all sub-domains of physical, social, and attitudinal environments (r=0.75-0.89), where the higher correlation was related to the physical environment (r=0.811, P<0.01).

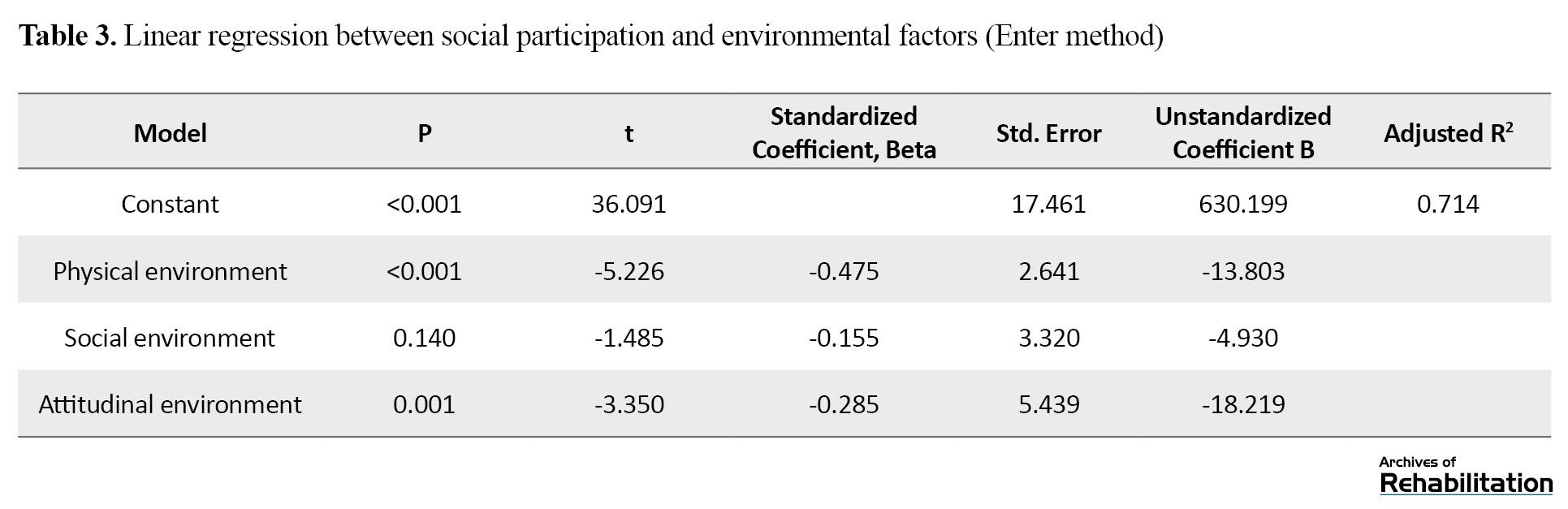

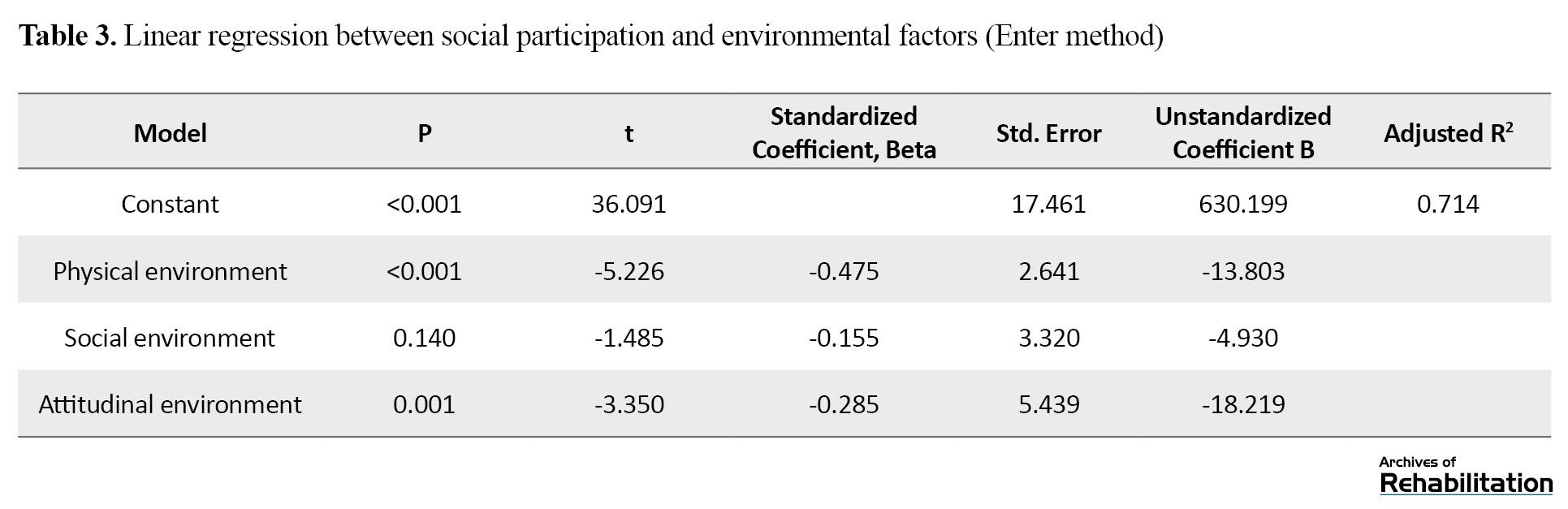

Among sub-domains, the highest correlation with social participation was related to “community” (r=-0.775) from the physical environment followed by “home” (r=-0.773) from the social environment and “home” (r=-0.713) from the physical environment (P<0.01). Table 3 presents that the model predicting the impact of environmental factors on social participation was significant (P<0.001).

The adjusted R2 value showed that the environmental factors could explain 71% of the variance in children’s social participation, and the regression model had a good fit. Among environmental factors, the relationship of physical (β=-0.475) and attitudinal (β=-0.285) environments with social participation were significant (P<0.05), but for social support variable (β=-0.155) it was not significant (P>0.05).

Discussion and Conclusion

According to the present study findings, all domains of ECEQ (physical, social, and attitudinal environments) had an acceptable correlation with the social participation of children with CPSD, which has also been reported in previous studies [27, 32]. According to these children’s parents, the predictors of social participation in their children were physical and attitudinal environments. The social environment, due to its non-significance, was not included in the regression model for social participation. According to the ICF-CY, environmental factors affecting social participation are classified into five categories: (a) products and technology, (b) natural environment and construction, (c) support and relationships, (d) attitudes, values, and beliefs, and (e) services, systems, and policies [11]. In our study, categories a and b were considered physical environment; categories c and e, social environment; and category d as the attitudinal environment.

Children’s social participation compared to adults’ social participation is vital in several ways. First, their brains at a young age have greater plasticity, and the neuroplasticity of the brain increases the power of learning at a young age [33]. Second, through participation at home, school, and community, a child’s identity and personality develop, and s/he becomes an active and independent individual in the society [34]. Third, social participation prevents the complications of non-participation in children with CPSD, such as short stature, deformity, and obesity [17].

Individual factors such as type and severity of disease, cognitive impairment, seizures, ability to walk, visual impairment, and other comorbidities have been reported effective in many studies [16 ,20 ,35]. Most of these factors are a part of a child’s disease with CPSD, but environmental factors such as physical environment, social support, and attitudes are not a part of cerebral palsy and are changed by changing policies, support, culture, and attitudes. Our results showed that an increase in the standard deviation of the physical environment led to a decrease of 0.475 in the standard deviation of social participation in children with CPSD. In the studies by Law et al. and Vogts et al. the critical barriers to participation were two physical and structural factors and workplace and school environments [6, 36]. Although their samples included children with cerebral palsy, we focused only on children with spastic diplegia, most of whom could walk independently. Achieving the same results indicates the existence of the same environmental factor (physical environment) from the perspective of the parents of these children. Therefore, the need to optimize the physical environment at home, school, community, and transportation system is essential to increase the social participation of children with CPSD. Obstacles at home, community, and school environment can lead to complications such as falling and fear of falling, which results in the unwillingness of the child or his/her family to participate in social activities that require more mobility [37]. Opheim et al. showed that people with CPSD fall more than 50 times per year [38]. Therefore, improving the home, community (urban space), and school environment can reduce the fear of falling and, thus, increase the mobility and social participation of children with CPSD [39].

Another study finding was the role of attitudinal environment in predicting the social participation of children with CPSD. An increase in the standard deviation of the negative attitudes of relatives, family members, friends, classmates, therapists, and others led to a decrease of 0.285 in the standard deviation of social participation in children with CPSD. Negative social attitudes are the most critical barriers for children with CPSD to participate in social activities and work [12, 20]. In Colver et al.’s study, children with limited mobility suffered more from the negative attitudes of family members and friends towards them [27]. Dickinson et al. stated about the existence of hidden dimensions in the attitude of family members, community, and school [26]. Negative attitudes towards a child with CPSD can prevent the parent or caregiver from wanting to accompany and encourage the child to move around independently or with assistive devices, and ultimately reduce the child’s social participation [40, 41]. In our study, although social environment had a good correlation with the social participation of children with CPSD, it did not predict their social participation from the parents’ point of view. This finding is consistent with the results of Nobakht et al. who reported that most of these children were exposed to the factors in the two areas of service and assistance [21]. Law et al. also reported the effect of the environmental factor of social support on the social participation perceived by the parents of children with CPSD [6]. This result indicates the need for good support from family members, friends, and relatives and providing public and organizational financial support to the families of children with CPSD. In our study, 71% of the changes in social participation of children with CPSD were explained by the physical environment, social support, and attitudes, which indicates a very high role of environmental factors. The rest of this amount (29%) can be related to other hidden individual and environmental factors.

One of this study’s limitations was performing it on the children with CPSD in Tehran, Alborz, and Mazandaran provinces of Iran. Given that the type and severity of cerebral palsy and place of residence are among the environmental factors affecting social participation rate, further studies can be conducted in different areas and different cerebral palsy types in children.

Physical environment, social support, and attitude have an acceptable correlation with the social participation of children with CPSD. The physical environment is also a predictor of social participation in them. By environmental adaptations at home, community, school, and transportation system, the social participation of children with CPSD can be increased.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study obtained its ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1394.225)

Funding

The paper was extracted from the thesis PhD.dissertation of the first author, Pediatric Neuro Rehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

erebral Palsy Spastic Diplegia (CPSD) is the most common childhood disability with a prevalence of 2-3 per 1000 live births [2]. Brain damage affects the growth and development and daily activities of children with CPSD throughout their lives and affects their social participation, too [3]. According to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, Child and Youth version (ICF-CY), participation is defined as a person’s “involvement in a life situation” [4]. This classification considers the context in which the disabled person lives as an influential factor of participation. This context consists of personal factors such as personality and the way of coping with environmental issues and factors, including physical, social, and attitudinal [5]. Our environment is designed and built for healthy people, and the problems of people with mobility impairments are less considered in its design [6]. In general, the environment can be a facilitator or a barrier to participation [7]. Law et al. stated that cultural, economic, institutional, physical, social, and attitudinal factors in the environment could facilitate or hinder the participation of children with disabilities [8]. In examining the environmental factors, it is essential to consider issues such as access, provision, availability of resources, social support, and equality [9].

CPSD children’s participation is affected by factors such as the type of cerebral palsy, the degree of mental disability, epilepsy, and the ability to walk and communicate [5, 10]. Psychosocial pressures, financial problems, and inadequate service systems, as well as building design, lack of income, and access to special facilities can also affect CPSD children’s participation [11]. Mobility factors, transportation system, parental support, and others’ attitude towards CPSD children [12, 13, 14], as well as the type and severity of disease [15, 16], are some factors affecting the social participation of these children. Their participation is also influenced by their functional abilities, skills, interests, and family culture [16, 17]. According to the parents of CPSD children, the role of environmental factors such as provided services, assistance, and policies in non-participation are more critical than other factors [21]. Pashmdar Fard et al. reported the limited participation of children with CPSD in Iran and emphasized further studies in this field [22]. This study aimed to investigate the predictive effect of environmental factors on the social participation of children with CPSD.

Materials and Methods

This research is a cross-sectional study. The study population consists of all children with CPSD and their parents living in Tehran, Mazandaran, and Alborz provinces of Iran. Of them, 116 children and their parents were selected as study samples using a convenience sampling method. The inclusion criteria were being 6-18 years old and having been diagnosed CPSD by a pediatric neurologist or based on the medical record, and those who have had botox injection or history of surgery at least in the past 6 months. The exclusion criteria were disorders such as hydrocephalus, blindness and deafness, and lack of parental cooperation. After declaring verbal consent, the written consent was obtained from the children and their parents. The Gross Motor Function Classification System-Expanded and Revised (GMFCS-E&R) classification system was used for children. It is based on spontaneous movement with an emphasis on sitting, transfers, and mobility [24]. The children’s cognitive level was classified according to the impairment form of the SPARCLE project in three sub-categories of IQ>70, IQ: 50-70, and IQ<50 [21]. In this form, the IQ is expressed based on ICD 10 [25].

In addition to recording demographic (gender and age) and medical characteristics (hearing, vision, history of seizures, cognitive level), parents of children completed the Life Habit (LIFE-H) questionnaire to assess social participation of children and the European Child Environment Questionnaire (ECEQ) to assess environmental factors. The SPARCLE group developed the ECEQ, too [26, 27]. The “need” of each item was scored as “0=not needed”, and “1=needed”. Also, “availability” of each item was scored as “0=needed and available” and “1=needed and not available” [28]. The LIFE-H was developed by Noreau et al. in Québec, Canada [29]. The items are scored from 0 (not performed) to 9 (performed) based on the difficulty and the need for assistance. Its total score ranges from 0 to 10 [29, 30].

To investigate the relationship of social participation with the subscales of ECEQ, we used the correlation test and interpreted it, according to Portney and Watkins, as excellent (>0.90), good (0.75-0.89), moderate (0.50-0.74), and poor (<0.50) correlation. The significant value for all cases was 0.05 [23]. The linear regression analysis was used to predict the impact of environmental factors (physical, social, and attitudinal environments) on participation rate based on the standard beta coefficient value and a significance level of 0.05.

Results

In this study, 116 children with CPSD aged 6-18 years with a Mean±SD age of 129.49±16.70 months (72 boys and 44 girls) participated. Also, 27 children (23.3%) were in category I, 32 (27.6%) in category II, 37 (31.9%) in category III, and 20 (17.2%) in category IV, according to the GMFCS-E&R classification system. Besides, 104 (89.7%) had an IQ above 75. Also, 4.3% and 14.7% of the children had visual and hearing impairment, respectively. Moreover, 85.3% had no seizures (Table 1).

According to Table 2, a good correlation with social participation was obtained for all sub-domains of physical, social, and attitudinal environments (r=0.75-0.89), where the higher correlation was related to the physical environment (r=0.811, P<0.01).

Among sub-domains, the highest correlation with social participation was related to “community” (r=-0.775) from the physical environment followed by “home” (r=-0.773) from the social environment and “home” (r=-0.713) from the physical environment (P<0.01). Table 3 presents that the model predicting the impact of environmental factors on social participation was significant (P<0.001).

The adjusted R2 value showed that the environmental factors could explain 71% of the variance in children’s social participation, and the regression model had a good fit. Among environmental factors, the relationship of physical (β=-0.475) and attitudinal (β=-0.285) environments with social participation were significant (P<0.05), but for social support variable (β=-0.155) it was not significant (P>0.05).

Discussion and Conclusion

According to the present study findings, all domains of ECEQ (physical, social, and attitudinal environments) had an acceptable correlation with the social participation of children with CPSD, which has also been reported in previous studies [27, 32]. According to these children’s parents, the predictors of social participation in their children were physical and attitudinal environments. The social environment, due to its non-significance, was not included in the regression model for social participation. According to the ICF-CY, environmental factors affecting social participation are classified into five categories: (a) products and technology, (b) natural environment and construction, (c) support and relationships, (d) attitudes, values, and beliefs, and (e) services, systems, and policies [11]. In our study, categories a and b were considered physical environment; categories c and e, social environment; and category d as the attitudinal environment.

Children’s social participation compared to adults’ social participation is vital in several ways. First, their brains at a young age have greater plasticity, and the neuroplasticity of the brain increases the power of learning at a young age [33]. Second, through participation at home, school, and community, a child’s identity and personality develop, and s/he becomes an active and independent individual in the society [34]. Third, social participation prevents the complications of non-participation in children with CPSD, such as short stature, deformity, and obesity [17].

Individual factors such as type and severity of disease, cognitive impairment, seizures, ability to walk, visual impairment, and other comorbidities have been reported effective in many studies [16 ,20 ,35]. Most of these factors are a part of a child’s disease with CPSD, but environmental factors such as physical environment, social support, and attitudes are not a part of cerebral palsy and are changed by changing policies, support, culture, and attitudes. Our results showed that an increase in the standard deviation of the physical environment led to a decrease of 0.475 in the standard deviation of social participation in children with CPSD. In the studies by Law et al. and Vogts et al. the critical barriers to participation were two physical and structural factors and workplace and school environments [6, 36]. Although their samples included children with cerebral palsy, we focused only on children with spastic diplegia, most of whom could walk independently. Achieving the same results indicates the existence of the same environmental factor (physical environment) from the perspective of the parents of these children. Therefore, the need to optimize the physical environment at home, school, community, and transportation system is essential to increase the social participation of children with CPSD. Obstacles at home, community, and school environment can lead to complications such as falling and fear of falling, which results in the unwillingness of the child or his/her family to participate in social activities that require more mobility [37]. Opheim et al. showed that people with CPSD fall more than 50 times per year [38]. Therefore, improving the home, community (urban space), and school environment can reduce the fear of falling and, thus, increase the mobility and social participation of children with CPSD [39].

Another study finding was the role of attitudinal environment in predicting the social participation of children with CPSD. An increase in the standard deviation of the negative attitudes of relatives, family members, friends, classmates, therapists, and others led to a decrease of 0.285 in the standard deviation of social participation in children with CPSD. Negative social attitudes are the most critical barriers for children with CPSD to participate in social activities and work [12, 20]. In Colver et al.’s study, children with limited mobility suffered more from the negative attitudes of family members and friends towards them [27]. Dickinson et al. stated about the existence of hidden dimensions in the attitude of family members, community, and school [26]. Negative attitudes towards a child with CPSD can prevent the parent or caregiver from wanting to accompany and encourage the child to move around independently or with assistive devices, and ultimately reduce the child’s social participation [40, 41]. In our study, although social environment had a good correlation with the social participation of children with CPSD, it did not predict their social participation from the parents’ point of view. This finding is consistent with the results of Nobakht et al. who reported that most of these children were exposed to the factors in the two areas of service and assistance [21]. Law et al. also reported the effect of the environmental factor of social support on the social participation perceived by the parents of children with CPSD [6]. This result indicates the need for good support from family members, friends, and relatives and providing public and organizational financial support to the families of children with CPSD. In our study, 71% of the changes in social participation of children with CPSD were explained by the physical environment, social support, and attitudes, which indicates a very high role of environmental factors. The rest of this amount (29%) can be related to other hidden individual and environmental factors.

One of this study’s limitations was performing it on the children with CPSD in Tehran, Alborz, and Mazandaran provinces of Iran. Given that the type and severity of cerebral palsy and place of residence are among the environmental factors affecting social participation rate, further studies can be conducted in different areas and different cerebral palsy types in children.

Physical environment, social support, and attitude have an acceptable correlation with the social participation of children with CPSD. The physical environment is also a predictor of social participation in them. By environmental adaptations at home, community, school, and transportation system, the social participation of children with CPSD can be increased.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study obtained its ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences (Code: IR.USWR.REC.1394.225)

Funding

The paper was extracted from the thesis PhD.dissertation of the first author, Pediatric Neuro Rehabilitation Research Center, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences.

Authors' contributions

All authors contributed equally in preparing this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Shevell M. Cerebral palsy to cerebral palsy spectrum disorder: Time for a name change? Neurology. 2019; 92(5):233-5. [DOI:10.1212/WNL.0000000000006747] [PMID]

- Rosenbaum P, Paneth N, Leviton A, Goldstein M, Bax M, Damiano D, et al. A report: The definition and classification of cerebral palsy April 2006. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. Supplement. 2007; 109(suppl 109):8-14. [PMID]

- Rogers S. Common conditions that influence children’s participation. In: Teoksessa Case-Smith J, O’Brien JC, editors Occupational Therapy for Children. Missouri: Elsevier; 2010. https://www.worldcat.org/title/occupational-therapy-for-children/oclc/537394250

- World Health Organization (WHO). International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42407/9241545429.pdf

- Hammal D, Jarvis SN, Colver AF. Participation of children with cerebral palsy is influenced by where they live. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2004; 46(5):292-8. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2004.tb00488.x] [PMID]

- Law M, Petrenchik T, King G, Hurley P. Perceived environmental barriers to recreational, community, and school participation for children and youth with physical disabilities. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2007; 88(12):1636-42. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2007.07.035] [PMID]

- Kramer P, Hinojosa J, Royeen CB. Perspectives in human occupation: Participation in life. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2003. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Perspectives_in_Human_Occupation/-kaoonr_7ycC?hl=en&gbpv=0

- Petrenchik T, Ziviani J, King G. Participation of children in school and community. In: S Rodger, J Ziviani editors. Occupational Therapy with Children: Understanding Children's Occupations and Enabling Participation. Oxford: Blackwell; 2006. https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:72237

- Whiteneck G, Brooks C, Melick D. The creation of the Craig Hospital Inventory of Environmental Factors (CHIEF). Englewood Cliffs (CO): Craig Hospital; 1999.

- Sivaratnam C, Howells K, Stefanac N, Reynolds K, Rinehart N. Parent and clinician perspectives on the participation of children with cerebral palsy in community-based football: A qualitative exploration in a regional setting. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(3):1102. [DOI:10.3390/ijerph17031102] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Mihaylov SI, Jarvis SN, Colver AF, Beresford B. Identification and description of environmental factors that influence participation of children with cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2004; 46(5):299-304. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2004.tb00489.x] [PMID]

- Lawlor K, Mihaylov S, Welsh B, Jarvis S, Colver A. A qualitative study of the physical, social and attitudinal environments influencing the participation of children with cerebral palsy in northeast England. Pediatric Rehabilitation. 2006; 9(3):219-28. [DOI:10.1080/13638490500235649] [PMID]

- McManus V, Michelsen S, Parkinson K, Colver A, Beckung E, Pez O, et al. Discussion groups with parents of children with cerebral palsy in Europe designed to assist development of a relevant measure of environment. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2006; 32(2):185-92. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2006.00601.x] [PMID]

- Forsyth R, Colver A, Alvanides S, Woolley M, Lowe M. Participation of young severely disabled children is influenced by their intrinsic impairments and environment. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2007; 49(5):345-9. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00345.x] [PMID]

- Ziviani J, Desha L, Feeney R, Boyd R. Measures of participation outcomes and environmental considerations for children with acquired brain injury: A systematic review. Brain Impairment. 2010; 11(2):93-112. [DOI:10.1375/brim.11.2.93]

- Imms C. Children with cerebral palsy participate: A review of the literature. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2008; 30(24):1867-84. [DOI:10.1080/09638280701673542] [PMID]

- Fauconnier J, Dickinson HO, Beckung E, Marcelli M, McManus V, Michelsen SI, et al. Participation in life situations of 8-12 year old children with cerebral palsy: Cross sectional European study. The BMJ. 2009; 338:b1458. [DOI:10.1136/bmj.b1458] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Michelsen SI, Flachs EM, Uldall P, Eriksen EL, McManus V, Parkes J, et al. Frequency of participation of 8-12-year-old children with cerebral palsy: A multi-centre cross-sectional European study. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology. 2009; 13(2):165-77. [DOI:10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.03.005] [PMID]

- Reedman SE, Boyd RN, Trost SG, Elliott C, Sakzewski L. Efficacy of participation-focused therapy on performance of physical activity participation goals and habitual physical activity in children With cerebral palsy: A randomized Controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2019; 100(4):676-86. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2018.11.012] [PMID]

- Shikako-Thomas K, Majnemer A, Law M, Lach L. Determinants of participation in leisure activities in children and youth with cerebral palsy: Systematic review. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. 2008; 28(2):155-69. [DOI:10.1080/01942630802031834] [PMID]

- Nobakht Z, Rassafiani M, Rezasoltani P, Sahaf R, Yazdani F. Environmental barriers to social participation of children with cerebral palsy in Tehran. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2013; 11:40-5. https://irj.uswr.ac.ir/browse.php?a_id=355&sid=1&slc_lang=en&ftxt=1

- Pashmdarfard M, Amini M, MEHRABAN AH. Participation of Iranian cerebral palsy children in life areas: a systematic review article. Iranian Journal of Child Neurology. 2017; 11(1):1-12. [PMID] [PMCID]

- Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research. United Kingdom: Prentice Hall Health; 2000. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Foundations_of_Clinical_Research/zzhrAAAAMAAJ?hl=en

- Dehghan L, Abdolvahab M, Bagheri H, Dalvand H. Inter rater reliability of Persian version of Gross Motor Function Classification System Expanded and Revised in patients with cerebral palsy. Daneshvar Medicine. 2011; 18(91):37-44. https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=287460

- Colver A. Study protocol: SPARCLE - a multi-centre European study of the relationship of environment to participation and quality of life in children with cerebral palsy. BMC Public Health. 2006; 6(1):105. [DOI:10.1186/1471-2458-6-105] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dickinson HO, Colver A, Group S. Quantifying the physical, social and attitudinal environment of children with cerebral palsy. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2011; 33(1):36-50. [DOI:10.3109/09638288.2010.485668] [PMID]

- Colver A, Thyen U, Arnaud C, Beckung E, Fauconnier J, Marcelli M, et al. Association between participation in life situations of children with cerebral palsy and their physical, social, and attitudinal environment: A cross-sectional multicenter European study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2012; 93(12):2154-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.apmr.2012.07.011] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Salavati M, Vameghi R, Hosseini SA, Saeedi A, Gharib M. Reliability and validity of the European Child Environment Questionnaire (ECEQ) in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy: Persian Version. Children. 2018; 5(4):48. [DOI:10.3390/children5040048] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Noreau L, Fougeyrollas P, Vincent C. The LIFE-H: Assessment of the quality of social participation. Technology and Disability. 2002; 14(3):113-8. [DOI:10.3233/TAD-2002-14306]

- Coster W, Khetani MA. Measuring participation of children with disabilities: Issues and challenges. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2008; 30(8):639-48. [DOI:10.1080/09638280701400375] [PMID]

- Mortazavi SN, Rezaei M, Rassafiani M, Tabatabaei M, Mirzakhani N. [Validity and reliability of Persian version of LIFE-H assessment for children with cerebral palsy aged between 5 and 13 years old (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2014; 14(6):115-23. http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-1432-en.htm

- Colver A, Dickinson HO, Marcelli M, Michelsen SI, Parkes J, Parkinson K, et al. Predictors of participation of adolescents with cerebral palsy: A European multi-centre longitudinal study. Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2015; 36C:551-64. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.043] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dehghan L, Dalvand H. [Neuroplasticity after injury(Persian)]. Journal of Modern Rehabilitation 2008; 1(4):13-9. https://mrj.tums.ac.ir/browse.php?a_code=A-10-25-154&slc_lang=fa&sid=1

- Dalvand H, Dehghan L, Rassafiani M, Hosseini SA. Exploring the process of mothering co-occupations in caring of children with cerebral palsy at home. International Journal of Pediatrics. 2018; 6(2):7129-40. https://www.magiran.com/paper/1794108

- Welsh B, Jarvis S, Hammal D, Colver A. How might districts identify local barriers to participation for children with cerebral palsy? Public Health. 2006; 120(2):167-75. [DOI:10.1016/j.puhe.2005.04.006] [PMID]

- Vogts N, Mackey AH, Ameratunga S, Stott NS. Parent-perceived barriers to participation in children and adolescents with cerebral palsy. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2010; 46(11):680-5. [DOI:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01815.x] [PMID]

- Morris C, Kurinczuk JJ, Fitzpatrick R, Rosenbaum PL. Do the abilities of children with cerebral palsy explain their activities and participation? Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2006; 48(12):954-61. [DOI:10.1017/S0012162206002106] [PMID]

- Opheim A, Jahnsen R, Olsson E, Stanghelle JK. Balance in relation to walking deterioration in adults with spastic bilateral cerebral palsy. Physical Therapy. 2012; 92(2):279-88. [DOI:10.2522/ptj.20100432] [PMID]

- Morgan C, Novak I, Dale RC, Badawi N. Optimising motor learning in infants at high risk of cerebral palsy: A pilot study. BMC Pediatrics. 2015; 15:30. [DOI:10.1186/s12887-015-0347-2] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Badia M, Orgaz MB, Gómez-Vela M, Verdugo MA, Ullan AM, Longo E. Do environmental barriers affect the parent-reported quality of life of children and adolescents with cerebral palsy? Research in Developmental Disabilities. 2016; 49:312-21. [DOI:10.1016/j.ridd.2015.12.011] [PMID]

- Colver AF, Dickinson HO, Parkinson K, Arnaud C, Beckung E, Fauconnier J, et al. Access of children with cerebral palsy to the physical, social and attitudinal environment they need: A cross-sectional European study. Disability and Rehabilitation. 2011; 33(1):28-35. [DOI:10.3109/09638288.2010.485669] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Occupational Therapy

Received: 22/04/2020 | Accepted: 5/08/2020 | Published: 1/01/2021

Received: 22/04/2020 | Accepted: 5/08/2020 | Published: 1/01/2021

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |