Volume 24, Issue 3 (Autumn 2023)

jrehab 2023, 24(3): 364-381 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Abedinzadeh A, Shomal Nesab F, Sotoudeh Lar F, Azhdari E, Rajabi K, Hosseini Beidokhti M, et al . Comparison of Mental Health of Mothers of Children With Disorders Speech and Language With an Emphasis on the Duration of Receiving Rehabilitation Services. jrehab 2023; 24 (3) :364-381

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3205-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-3205-en.html

Azadeh Abedinzadeh1

, Fatemeh Shomal Nesab1

, Fatemeh Shomal Nesab1

, Fatemeh Sotoudeh Lar1

, Fatemeh Sotoudeh Lar1

, Emad Azhdari1

, Emad Azhdari1

, Kobra Rajabi1

, Kobra Rajabi1

, Masoumeh Hosseini Beidokhti *

, Masoumeh Hosseini Beidokhti *

2, Negin Moradi1

2, Negin Moradi1

, Seyed Mahmoud Latifi3

, Seyed Mahmoud Latifi3

, Fatemeh Hosseini Beidokhti4

, Fatemeh Hosseini Beidokhti4

, Fatemeh Shomal Nesab1

, Fatemeh Shomal Nesab1

, Fatemeh Sotoudeh Lar1

, Fatemeh Sotoudeh Lar1

, Emad Azhdari1

, Emad Azhdari1

, Kobra Rajabi1

, Kobra Rajabi1

, Masoumeh Hosseini Beidokhti *

, Masoumeh Hosseini Beidokhti *

2, Negin Moradi1

2, Negin Moradi1

, Seyed Mahmoud Latifi3

, Seyed Mahmoud Latifi3

, Fatemeh Hosseini Beidokhti4

, Fatemeh Hosseini Beidokhti4

1- Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation Research Center, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Ahvaz Jundishapour University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.

2- Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation Research Center, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Ahvaz Jundishapour University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran. ,masoume64hosseini@gmail.com

3- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Health, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.

4- Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Persian Literature and Foreign Languages, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran.

2- Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation Research Center, Faculty of Rehabilitation, Ahvaz Jundishapour University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran. ,

3- Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, Faculty of Health, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran.

4- Department of English Language and Literature, Faculty of Persian Literature and Foreign Languages, Semnan University, Semnan, Iran.

Keywords: Quality of life (QoL), Stress, Depression, Mothers, Speech and language disorders, Rehabilitation

Full-Text [PDF 1727 kb]

(534 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5291 Views)

Full-Text: (919 Views)

Introduction

The childs disability can profoundly affect the entire family, especially the parents. Parents typically expect the arrival of a healthy child. When developmental problems are diagnosed in their child, they may feel a great sense of guilt and responsibility for giving birth to a child with a disability [1, 2].

Disability is a broad concept that includes various physical, developmental, and emotional disorders [4]. One of the most common disorders in children is speech and language disorders, leading to multiple degrees of disability in children. Children with speech and language disorders have problems communicating with their environment [9]. Communication problems in these children can disrupt the acquisition of other skills and abilities, such as decision-making, self-confidence, self-esteem, independence, participation in social groups, and successful communication with peers [10].

Mothers are usually the primary caregivers of these children and are mostly affected psychologically. They bear the pressures and stresses of being responsible for these children [13, 14]. Mothers of children with developmental and psychological problems experience higher stress levels than mothers of typically developing children because the mother is the first person to communicate directly with the child. Feelings, such as guilt, fault, and deprivation stemming from the childs abnormality can result in the mothers isolation, depression, and disinterest in establishing a relationship with the environment; the outcomes are low self-esteem, depression, and jeopardy of mother›s mental health [15].

Rehabilitation services constitute an essential part of healthcare services for children with speech and language disorders. The process takes time and perseverance [28]. Given that rehabilitation results appear in the long term, the suitable mental conditions of parents, especially mothers, are of particular importance to continue and complete rehabilitation exercises. As such, the psychological well-being of children›s parents, particularly mothers, is a crucial sign that therapists should consider in providing treatment for children and families [14]. On the other hand, anxiety and depression are prominent symptoms that affect health-related QoL (HRQoL) [29].

Mothers play an essential role in the treatment process of their children; thus, their engagement in speech and language rehabilitation services and its resultant recovery over time can affect their stress levels, mental well-being, and quality of life (QoL) [23]. Hence, the duration of receiving rehabilitation interventions plays a vital role in the anxiety, depression, and QoL of mothers of children with speech and language disorders. Regrettably, this issue has not been addressed in previous studies.

Given the effectiveness of rehabilitation of speech and language disorders as well as the time-consuming nature of rehabilitation, we hypothesize that the level of stress, depression, and QoL in mothers of children with speech and language disorders will change over time (<1 month up to >1 year) after receiving rehabilitation services. Therefore, our study examined the relationship between anxiety, depression, and QoL in relation to the duration of receiving rehabilitation services.

Materials and Methods

This study was a cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study. The mothers were selected by convenience sampling. A total of 185 mothers of children with speech and language disorders were selected from mothers of children who received rehabilitation services in speech therapy centers affiliated with Ahvaz Jundishapour University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz City, Iran, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The childs specific disorder was diagnosed by a psychiatrist, audiologist, and or speech therapist, depending on the type of speech and language disorder.

The inclusion criteria included having a child with a speech/language disorder, possessing the educational proficiency to read, understand, and complete the questionnaire, demonstrating willingness to cooperate and participate in the project, and being 20-45 years old. The exclusion criteria included multiple interruptions in receiving child rehabilitation services and multiple disability disorders in the child. Based on the duration of receiving rehabilitation services, mothers participating in this study were divided into four groups: Mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services for <1 month, mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services between 1 and 6 months, mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services between 7 and 11 months, and mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services for >12 months. Also, other factors, including the child’s disorder, the mother’s age, level of education, and job status, were considered for group comparisons.

Before filling out the questionnaires, the procedure and purpose of the study were fully explained to the mothers. They were assured that the information obtained would remain confidential. Then, they were asked to complete a written informed consent form. During this process, a researcher, responsible for collecting the questionnaires, was present at the site to solve the problems and answer the mothers’ questions. The mothers were invited to complete the questionnaire in one of the quiet rooms of the medical center.

In this study, we used the parental stress index short form (PSI-SF) to measure stress, the Beck depression inventory-2nd edition (BDI-II) to measure mothers’ depression, and the health background questionnaire (short form of 36 questions) (SF- 36) to measure the quality of life. PSI-SF is a 36-item self-report scale with three subscales: Parental distress, challenging child behavior, and dysfunctional parent-child interactions [34]. BDI-II is a 21-question questionnaire and one of the widely recognized and commonly used self-report measures of depression symptoms in people over 13. Answers are given using a 4-point scale from 0 to 3 [39]. Finally, the health assessment questionnaire is a short and multi-purpose health assessment questionnaire containing 36 questions. It consists of 8 subscales: Physical functioning, physical limitations, body pain, general health, vitality, social function, role-emotional problems, and mental health [44].

Statistical analysis

In this study, we used the Shapiro-Wilk test to examine the normality of data distribution, Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances, and the M-box test to check the homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and Tukey’s post hoc test were used to compare the groups based on the duration of receiving rehabilitation services. Also, to compare the QoL, the level of anxiety, and depression of mothers in study groups, we used the multivariate ANOVA test. This analysis considers the effect of four factors: Type of disorder, age, education level, employment of mothers, as well as their interactive effects. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 22 at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

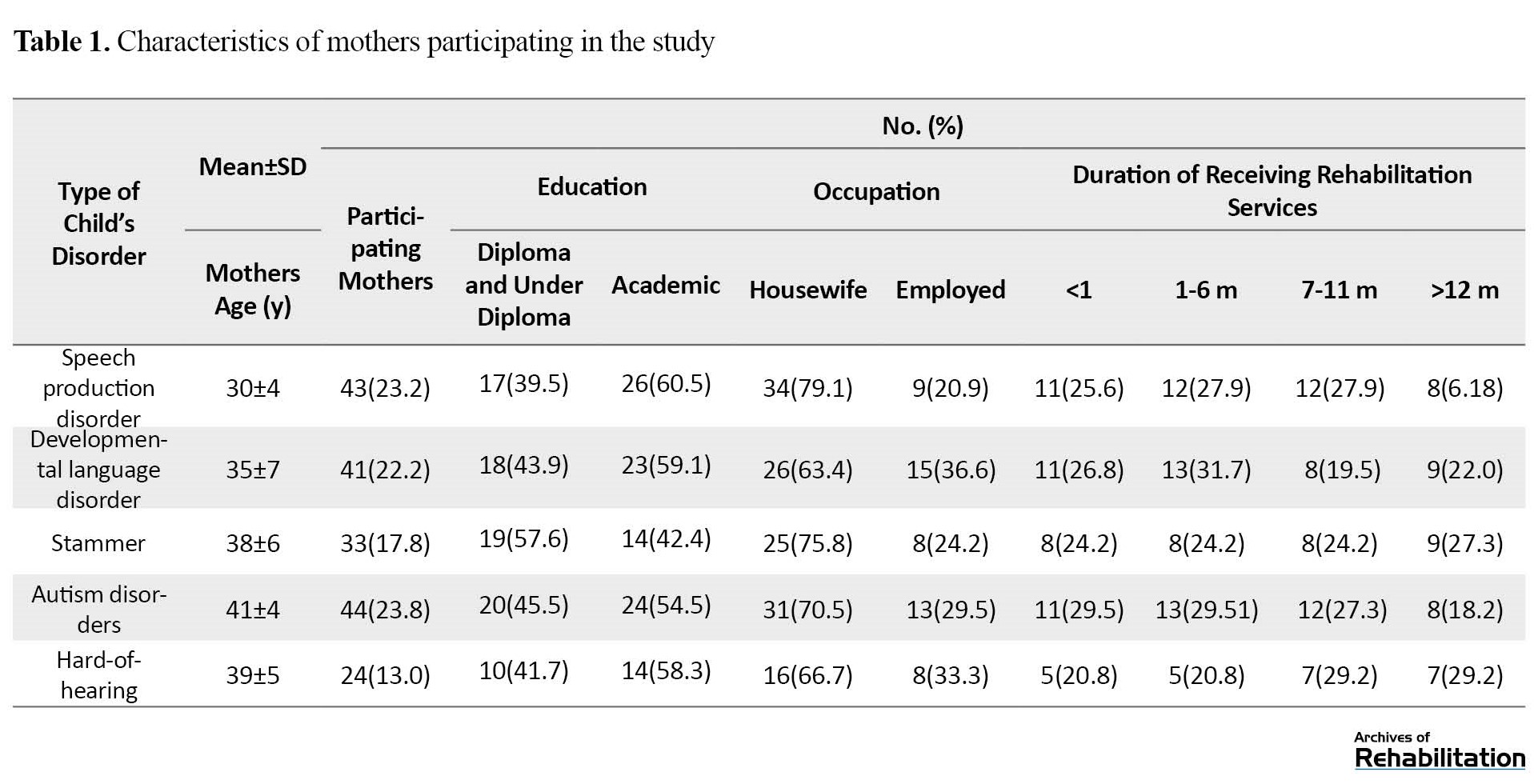

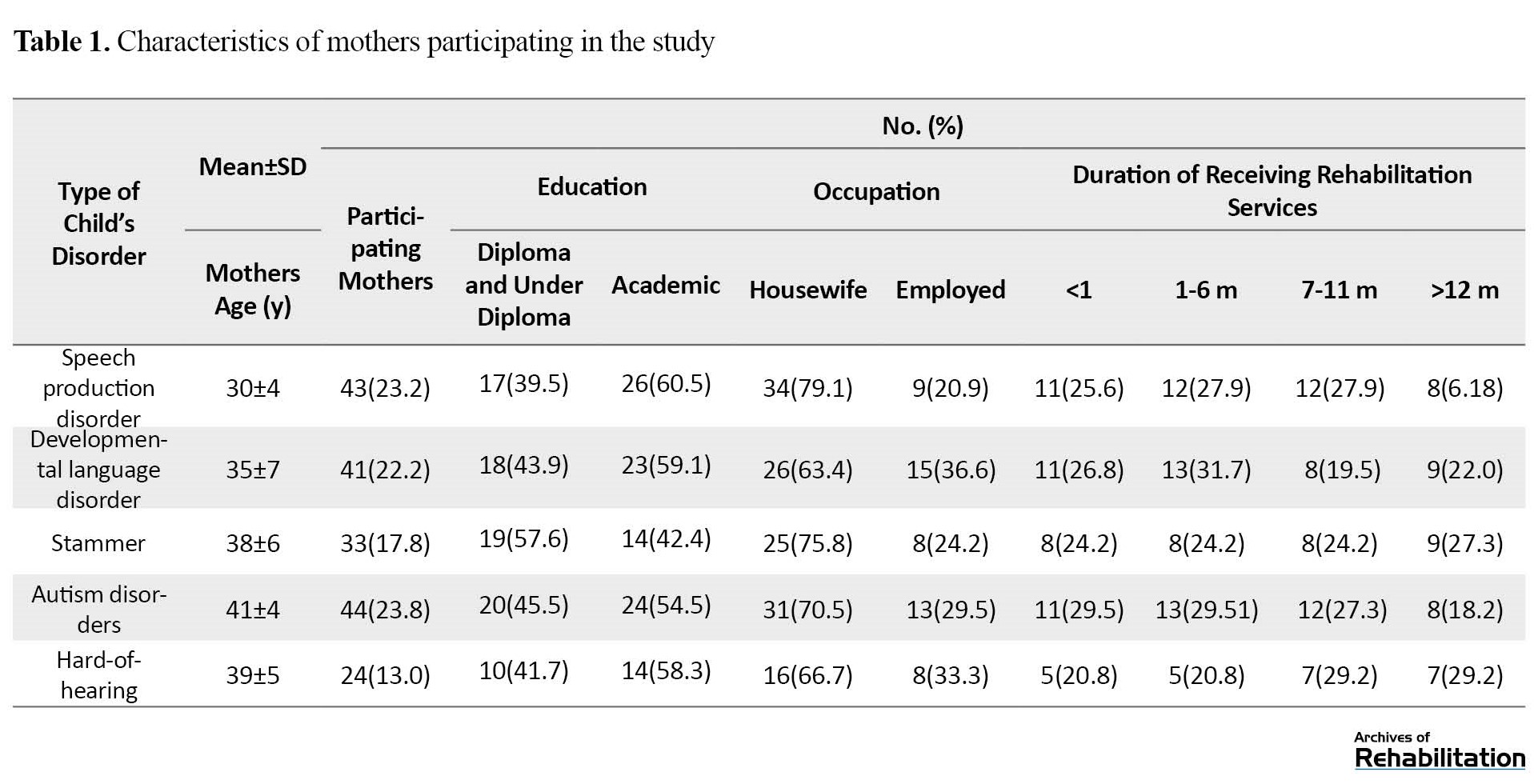

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants.

The Mean±SD age of mothers was 36.6±5.2 years.

According to the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test, the significance levels of all research variables exceeded 0.05, so the data of all variables were normally distributed. Also, based on the level of significance obtained in Leven's test, the equality of variances was established (P<0.05). Therefore, this assumption was also confirmed. The results of the M-box test also indicated that the assumption of homogeneity of the variance-covariance matrices was established (P<0.05).

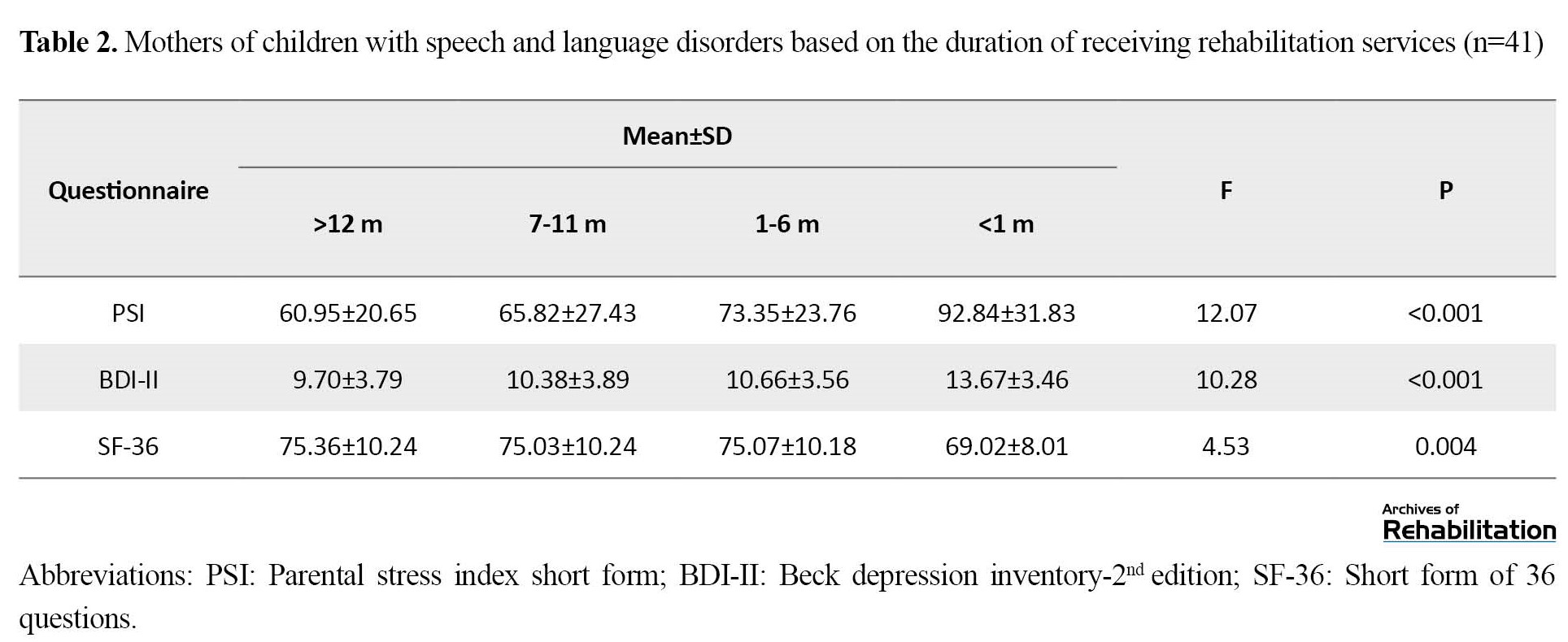

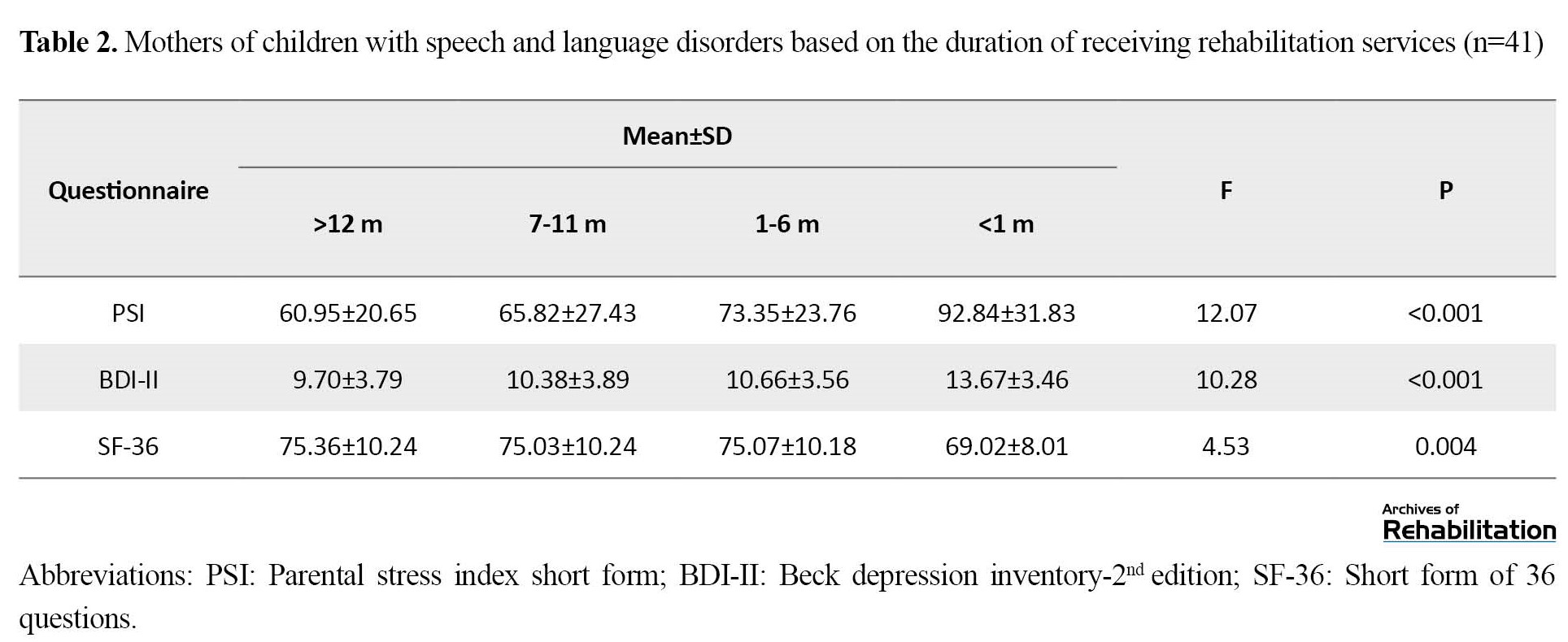

The one-way ANOVA showed that the effect of the duration of receiving rehabilitation services on the average scores of PSI, BDI-II, and SF-36 was statistically significant. Specifically, mothers whose children received rehabilitation services for >12 months had the lowest score in PSI and BDI-II and the highest score in SF-36 compared to the other 3 groups (P<0.001) (Table 2).

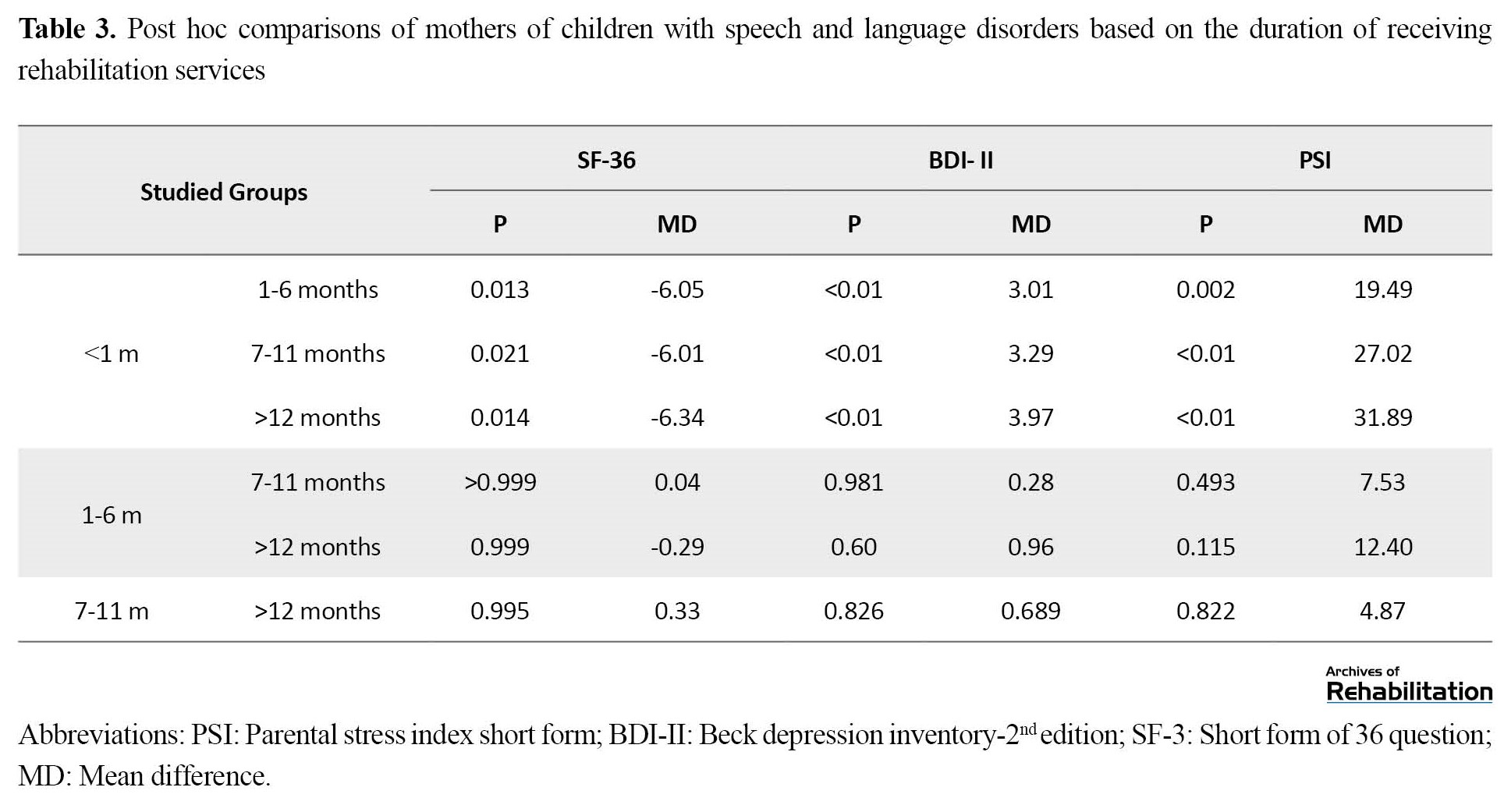

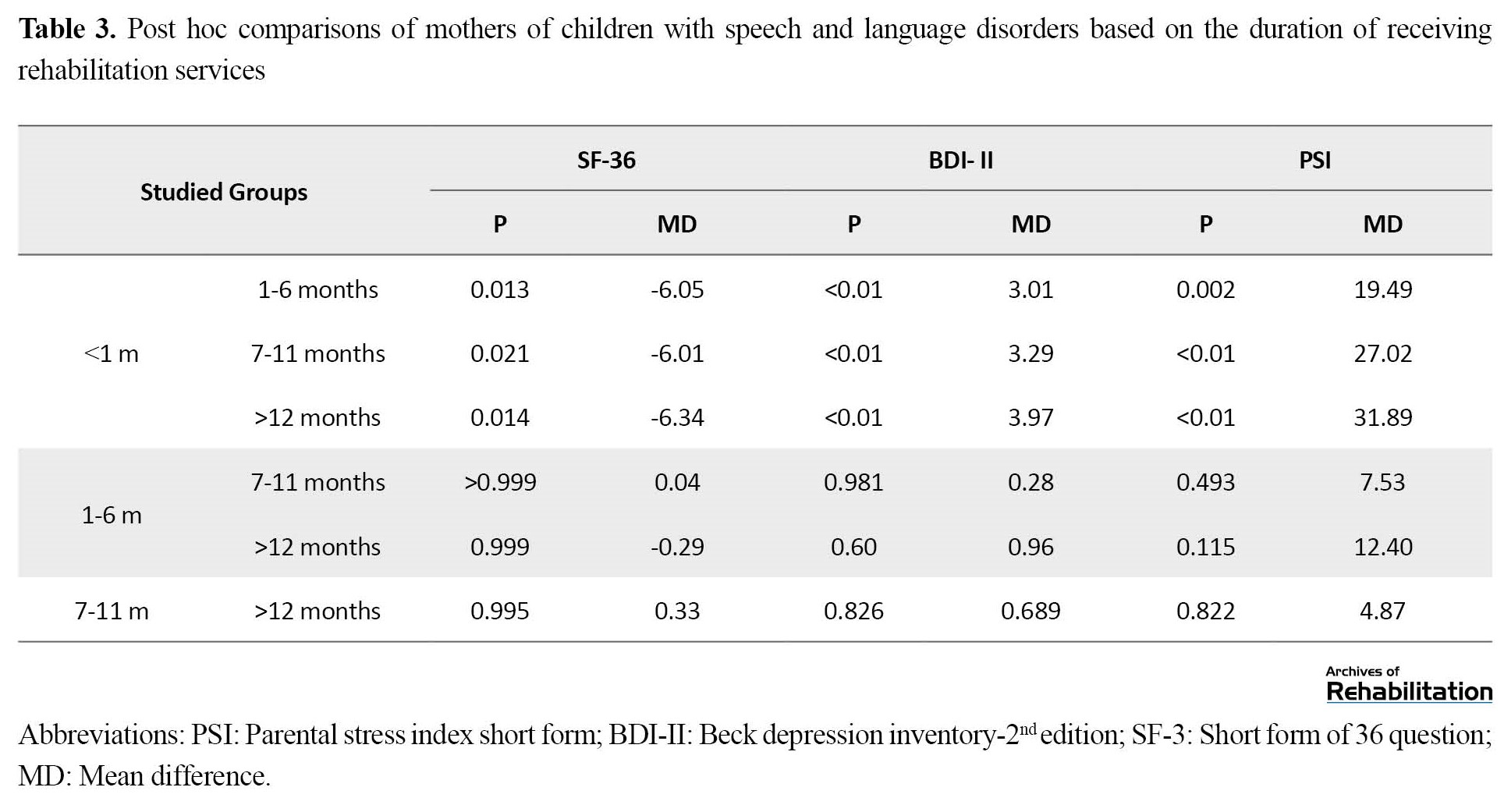

Also, the paired comparisons of Tukey’s post hoc test revealed that mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services for <1 month, compared to the other 3 groups had a lower QoL score and a higher level of stress and depression (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Also, based on the results of the multivariate ANOVA test, the effect of the type of disorder on the average scores of PSI, BDI-II, and SF-36 was statistically significant (P<0.05). So, mothers with children with speech production disorder displayed the lowest level of stress and depression (46.79±12.08 and 9.11±3.07, respectively) and the highest level of QoL (78.81±9.95). However, mothers of children with autism had the highest level of stress and depression (74.12±26.47 and 9.11±3.07, respectively) and the lowest level of QoL (71.66±6.24). In examining the effect of the mother’s age and education factors on the mean scores of PSI, BDI-II, and SF-36, no single or interaction effect was found on the studied variables (P>0.05). Lastly, the interactive and combined impact of the two factors of disorder type and duration of receiving rehabilitation, as well as three factors of disorder type, duration of receiving rehabilitation, and mother’s occupation, on the results of the mean PSI scores of mothers were significant (P<0.05). In other words, mothers of children with autism who had received rehabilitation services for >1 month, had the highest level of stress (119.54±25.33), and mothers of children with voice disorder who had received rehabilitation services for >1 year, had the lowest level of stress (35.12±4.05). Also, household mothers of children with autism who had received rehabilitation services for <1 month, had the highest level of stress (121.37±22.09), and working mothers of children with speech production disorder who had received rehabilitation services for >1 year, had the lowest level of stress (29.00±3.46).

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of the duration of rehabilitation interventions on the psychological characteristics and QoL of mothers of children with speech and language disorders. Children with speech and language disorders need specialized medical and healthcare attention, and mothers usually assume a vital role in meeting these needs [47, 48].

Overall, our results showed that mothers whose children received rehabilitation services for a longer period exhibited lower levels of stress and depression and a higher QoL. Therefore, receiving ongoing rehabilitation services increases the QoL of mothers and reduces their stress and depression over time. One possible reason for this outcome is that mothers who have recently discovered their children's problems are at the beginning of the treatment process and may have doubts about the effect of educational programs, thus experiencing more anxiety. However, since the results of rehabilitation interventions are revealed over time, ie, the child's communication skills improve, and the behavioral problems are reduced, mothers who receive rehabilitation services for a longer period may see more improvement in their children. Also, they are better equipped with stress-coping strategies to deal with their child's condition, resulting in improved psychological well-being [49].

This result was consistent with a study conducted by Robertson and Wisemer, who concluded that intervention for children with language delays not only improved their language skills but also enhanced their social skills and reduced parental stress [50]. Also, Burger et al. showed that the stress level in mothers of hard-of-hearing children was very high after diagnosing their child's problem. However, their stress level decreased with the beginning of treatment sessions and over time [51]. In Lederberg's study, mothers of 22-month-old hard-of-hearing children were more concerned about their child's condition than mothers of normal-hearing children. Nevertheless, no significant difference was observed in the mean PSI of mothers of 3- and 4-year-old children. They found that this lack of difference in the preschool period may be due to the success of early intervention programs [52].

Among different speech and language disorders, mothers of children with autism disorders had higher stress and depression scores and lower QoL. This result is consistent with the study conducted by Burgis et al. and Islami et al [15, 53]. Their studies indicate that the QoL, hope, and meaning of life of mothers of children with autism are significantly lower than that of mothers with healthy children and mothers with deaf children or with intellectual learning problems [14 , 53]. Also, Ogeston et al. found that mothers of children with autism reported lower hope and more worry about the future than mothers with children with Down syndrome [54]. Lloyd et al. in a study, examined the relationship between hope and mental health in 198 mothers of children with mental retardation, autism, and Down syndrome and found that mothers of children with autism had a lower score on the hope and mental health scale compared to the other two groups [55]. In explaining the low level of hope observed in the mothers of children with autism compared to other mothers, we can attribute this difference to some of the characteristics of autism disorder compared to other disorders. These characteristics, such as language, communication, behavioral, and social abnormalities, create a lot of tension in the family and require special and continuous care, education, and treatment for children with autism [15].

Future studies are suggested to adopt a longitudinal approach, spanning an extended approach, and involve a larger sample size.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that therapeutic interventions and the improvement of children’s communication skills are an opportunity to support mothers of children with speech and language disorders. By determining treatment goals and participating mothers in their child’s treatment and the consequent improvement, therapists can increase mothers’ satisfaction with their children’s recovery process and, as a result, reduce their stress and depression and increase their QoL. Therefore, it is suggested to hold educational and counseling classes to reduce the worries of mothers of children at the beginning of treatment and to increase their awareness about their child’s personality and communication characteristics. Also, forming mothers’ groups to share their experiences can provide a valuable platform for these families to receive support from each other and increase their hope.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study approved by the Ethics Committee of Jundishapur Ahvaz University of Medical Sciences (AJUMS) (Code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1399.291). Before the participants completed the questionnaires, the procedure and purpose of the study were fully explained to them. The participants were assured that the information obtained from the questionnaires would remain confidential, and written consent was obtained from the participants. In this study, they were allowed to exclude the study whenever they wanted.

Funding

This article was derived from a research project (No.: PHT-9910) under the auspices of the Research and Technology Vice-Chancellor of Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Masoumeh Hosseini Bidokhti and Azadeh Abedinzadeh; Research and data collection: Fateme Shamal Nasab, Fatemeh Sotoudeh Lar, Emad Azhdari and Kobra Rajabi; Data analysis: Seyyed Mahmoud Latifi; Writing the initial draft and sourcing: Azadeh Abedinzadeh, Masoumeh Hosseini Bidkhti and Fatemeh Hosseini Bidkhti; Editing the paper and finalization: Masoumeh Hosseini Bidkhti, Azadeh Abedinzadeh, Seyed Mahmoud Latifi, Fatemeh Hosseini Bidkhti and Negin Moradi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the mothers who participated in this study, as well as the esteemed staff of the speech therapy department of the centers covered by Ahwaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences who cooperated in this study.

References

The childs disability can profoundly affect the entire family, especially the parents. Parents typically expect the arrival of a healthy child. When developmental problems are diagnosed in their child, they may feel a great sense of guilt and responsibility for giving birth to a child with a disability [1, 2].

Disability is a broad concept that includes various physical, developmental, and emotional disorders [4]. One of the most common disorders in children is speech and language disorders, leading to multiple degrees of disability in children. Children with speech and language disorders have problems communicating with their environment [9]. Communication problems in these children can disrupt the acquisition of other skills and abilities, such as decision-making, self-confidence, self-esteem, independence, participation in social groups, and successful communication with peers [10].

Mothers are usually the primary caregivers of these children and are mostly affected psychologically. They bear the pressures and stresses of being responsible for these children [13, 14]. Mothers of children with developmental and psychological problems experience higher stress levels than mothers of typically developing children because the mother is the first person to communicate directly with the child. Feelings, such as guilt, fault, and deprivation stemming from the childs abnormality can result in the mothers isolation, depression, and disinterest in establishing a relationship with the environment; the outcomes are low self-esteem, depression, and jeopardy of mother›s mental health [15].

Rehabilitation services constitute an essential part of healthcare services for children with speech and language disorders. The process takes time and perseverance [28]. Given that rehabilitation results appear in the long term, the suitable mental conditions of parents, especially mothers, are of particular importance to continue and complete rehabilitation exercises. As such, the psychological well-being of children›s parents, particularly mothers, is a crucial sign that therapists should consider in providing treatment for children and families [14]. On the other hand, anxiety and depression are prominent symptoms that affect health-related QoL (HRQoL) [29].

Mothers play an essential role in the treatment process of their children; thus, their engagement in speech and language rehabilitation services and its resultant recovery over time can affect their stress levels, mental well-being, and quality of life (QoL) [23]. Hence, the duration of receiving rehabilitation interventions plays a vital role in the anxiety, depression, and QoL of mothers of children with speech and language disorders. Regrettably, this issue has not been addressed in previous studies.

Given the effectiveness of rehabilitation of speech and language disorders as well as the time-consuming nature of rehabilitation, we hypothesize that the level of stress, depression, and QoL in mothers of children with speech and language disorders will change over time (<1 month up to >1 year) after receiving rehabilitation services. Therefore, our study examined the relationship between anxiety, depression, and QoL in relation to the duration of receiving rehabilitation services.

Materials and Methods

This study was a cross-sectional descriptive-analytical study. The mothers were selected by convenience sampling. A total of 185 mothers of children with speech and language disorders were selected from mothers of children who received rehabilitation services in speech therapy centers affiliated with Ahvaz Jundishapour University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz City, Iran, based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The childs specific disorder was diagnosed by a psychiatrist, audiologist, and or speech therapist, depending on the type of speech and language disorder.

The inclusion criteria included having a child with a speech/language disorder, possessing the educational proficiency to read, understand, and complete the questionnaire, demonstrating willingness to cooperate and participate in the project, and being 20-45 years old. The exclusion criteria included multiple interruptions in receiving child rehabilitation services and multiple disability disorders in the child. Based on the duration of receiving rehabilitation services, mothers participating in this study were divided into four groups: Mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services for <1 month, mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services between 1 and 6 months, mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services between 7 and 11 months, and mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services for >12 months. Also, other factors, including the child’s disorder, the mother’s age, level of education, and job status, were considered for group comparisons.

Before filling out the questionnaires, the procedure and purpose of the study were fully explained to the mothers. They were assured that the information obtained would remain confidential. Then, they were asked to complete a written informed consent form. During this process, a researcher, responsible for collecting the questionnaires, was present at the site to solve the problems and answer the mothers’ questions. The mothers were invited to complete the questionnaire in one of the quiet rooms of the medical center.

In this study, we used the parental stress index short form (PSI-SF) to measure stress, the Beck depression inventory-2nd edition (BDI-II) to measure mothers’ depression, and the health background questionnaire (short form of 36 questions) (SF- 36) to measure the quality of life. PSI-SF is a 36-item self-report scale with three subscales: Parental distress, challenging child behavior, and dysfunctional parent-child interactions [34]. BDI-II is a 21-question questionnaire and one of the widely recognized and commonly used self-report measures of depression symptoms in people over 13. Answers are given using a 4-point scale from 0 to 3 [39]. Finally, the health assessment questionnaire is a short and multi-purpose health assessment questionnaire containing 36 questions. It consists of 8 subscales: Physical functioning, physical limitations, body pain, general health, vitality, social function, role-emotional problems, and mental health [44].

Statistical analysis

In this study, we used the Shapiro-Wilk test to examine the normality of data distribution, Levene’s test for homogeneity of variances, and the M-box test to check the homogeneity of variance-covariance matrices. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test and Tukey’s post hoc test were used to compare the groups based on the duration of receiving rehabilitation services. Also, to compare the QoL, the level of anxiety, and depression of mothers in study groups, we used the multivariate ANOVA test. This analysis considers the effect of four factors: Type of disorder, age, education level, employment of mothers, as well as their interactive effects. Data were analyzed using SPSS software, version 22 at a significance level of 0.05.

Results

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants.

The Mean±SD age of mothers was 36.6±5.2 years.

According to the results of the Shapiro-Wilk test, the significance levels of all research variables exceeded 0.05, so the data of all variables were normally distributed. Also, based on the level of significance obtained in Leven's test, the equality of variances was established (P<0.05). Therefore, this assumption was also confirmed. The results of the M-box test also indicated that the assumption of homogeneity of the variance-covariance matrices was established (P<0.05).

The one-way ANOVA showed that the effect of the duration of receiving rehabilitation services on the average scores of PSI, BDI-II, and SF-36 was statistically significant. Specifically, mothers whose children received rehabilitation services for >12 months had the lowest score in PSI and BDI-II and the highest score in SF-36 compared to the other 3 groups (P<0.001) (Table 2).

Also, the paired comparisons of Tukey’s post hoc test revealed that mothers whose children had received rehabilitation services for <1 month, compared to the other 3 groups had a lower QoL score and a higher level of stress and depression (P<0.001) (Table 3).

Also, based on the results of the multivariate ANOVA test, the effect of the type of disorder on the average scores of PSI, BDI-II, and SF-36 was statistically significant (P<0.05). So, mothers with children with speech production disorder displayed the lowest level of stress and depression (46.79±12.08 and 9.11±3.07, respectively) and the highest level of QoL (78.81±9.95). However, mothers of children with autism had the highest level of stress and depression (74.12±26.47 and 9.11±3.07, respectively) and the lowest level of QoL (71.66±6.24). In examining the effect of the mother’s age and education factors on the mean scores of PSI, BDI-II, and SF-36, no single or interaction effect was found on the studied variables (P>0.05). Lastly, the interactive and combined impact of the two factors of disorder type and duration of receiving rehabilitation, as well as three factors of disorder type, duration of receiving rehabilitation, and mother’s occupation, on the results of the mean PSI scores of mothers were significant (P<0.05). In other words, mothers of children with autism who had received rehabilitation services for >1 month, had the highest level of stress (119.54±25.33), and mothers of children with voice disorder who had received rehabilitation services for >1 year, had the lowest level of stress (35.12±4.05). Also, household mothers of children with autism who had received rehabilitation services for <1 month, had the highest level of stress (121.37±22.09), and working mothers of children with speech production disorder who had received rehabilitation services for >1 year, had the lowest level of stress (29.00±3.46).

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of the duration of rehabilitation interventions on the psychological characteristics and QoL of mothers of children with speech and language disorders. Children with speech and language disorders need specialized medical and healthcare attention, and mothers usually assume a vital role in meeting these needs [47, 48].

Overall, our results showed that mothers whose children received rehabilitation services for a longer period exhibited lower levels of stress and depression and a higher QoL. Therefore, receiving ongoing rehabilitation services increases the QoL of mothers and reduces their stress and depression over time. One possible reason for this outcome is that mothers who have recently discovered their children's problems are at the beginning of the treatment process and may have doubts about the effect of educational programs, thus experiencing more anxiety. However, since the results of rehabilitation interventions are revealed over time, ie, the child's communication skills improve, and the behavioral problems are reduced, mothers who receive rehabilitation services for a longer period may see more improvement in their children. Also, they are better equipped with stress-coping strategies to deal with their child's condition, resulting in improved psychological well-being [49].

This result was consistent with a study conducted by Robertson and Wisemer, who concluded that intervention for children with language delays not only improved their language skills but also enhanced their social skills and reduced parental stress [50]. Also, Burger et al. showed that the stress level in mothers of hard-of-hearing children was very high after diagnosing their child's problem. However, their stress level decreased with the beginning of treatment sessions and over time [51]. In Lederberg's study, mothers of 22-month-old hard-of-hearing children were more concerned about their child's condition than mothers of normal-hearing children. Nevertheless, no significant difference was observed in the mean PSI of mothers of 3- and 4-year-old children. They found that this lack of difference in the preschool period may be due to the success of early intervention programs [52].

Among different speech and language disorders, mothers of children with autism disorders had higher stress and depression scores and lower QoL. This result is consistent with the study conducted by Burgis et al. and Islami et al [15, 53]. Their studies indicate that the QoL, hope, and meaning of life of mothers of children with autism are significantly lower than that of mothers with healthy children and mothers with deaf children or with intellectual learning problems [14 , 53]. Also, Ogeston et al. found that mothers of children with autism reported lower hope and more worry about the future than mothers with children with Down syndrome [54]. Lloyd et al. in a study, examined the relationship between hope and mental health in 198 mothers of children with mental retardation, autism, and Down syndrome and found that mothers of children with autism had a lower score on the hope and mental health scale compared to the other two groups [55]. In explaining the low level of hope observed in the mothers of children with autism compared to other mothers, we can attribute this difference to some of the characteristics of autism disorder compared to other disorders. These characteristics, such as language, communication, behavioral, and social abnormalities, create a lot of tension in the family and require special and continuous care, education, and treatment for children with autism [15].

Future studies are suggested to adopt a longitudinal approach, spanning an extended approach, and involve a larger sample size.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that therapeutic interventions and the improvement of children’s communication skills are an opportunity to support mothers of children with speech and language disorders. By determining treatment goals and participating mothers in their child’s treatment and the consequent improvement, therapists can increase mothers’ satisfaction with their children’s recovery process and, as a result, reduce their stress and depression and increase their QoL. Therefore, it is suggested to hold educational and counseling classes to reduce the worries of mothers of children at the beginning of treatment and to increase their awareness about their child’s personality and communication characteristics. Also, forming mothers’ groups to share their experiences can provide a valuable platform for these families to receive support from each other and increase their hope.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study approved by the Ethics Committee of Jundishapur Ahvaz University of Medical Sciences (AJUMS) (Code: IR.AJUMS.REC.1399.291). Before the participants completed the questionnaires, the procedure and purpose of the study were fully explained to them. The participants were assured that the information obtained from the questionnaires would remain confidential, and written consent was obtained from the participants. In this study, they were allowed to exclude the study whenever they wanted.

Funding

This article was derived from a research project (No.: PHT-9910) under the auspices of the Research and Technology Vice-Chancellor of Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and methodology: Masoumeh Hosseini Bidokhti and Azadeh Abedinzadeh; Research and data collection: Fateme Shamal Nasab, Fatemeh Sotoudeh Lar, Emad Azhdari and Kobra Rajabi; Data analysis: Seyyed Mahmoud Latifi; Writing the initial draft and sourcing: Azadeh Abedinzadeh, Masoumeh Hosseini Bidkhti and Fatemeh Hosseini Bidkhti; Editing the paper and finalization: Masoumeh Hosseini Bidkhti, Azadeh Abedinzadeh, Seyed Mahmoud Latifi, Fatemeh Hosseini Bidkhti and Negin Moradi.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to all the mothers who participated in this study, as well as the esteemed staff of the speech therapy department of the centers covered by Ahwaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences who cooperated in this study.

References

- Bumin G, Günal A, Tükel Ş. Anxiety, depression and quality of life in mothers of disabled children. SDÜ Tıp Fakültesi Dergisi. 2008; 15(1):6-11. [Link]

- Gogoi RR, Kumar R, Deuri SP. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in mothers of children with intellectual disability. Open Journal of Psychiatry & Allied Sciences. 2017; 8(1):71-5. [DOI:10.5958/2394-2061.2016.00046.X]

- Marsh D. Families and mental retardation: New directions in professional practice. London: Bloomsbury Publishing; 1992. [Link]

- Reichman NE, Corman H, Noonan K. Impact of child disability on the family. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008; 12(6):679-83. [DOI:10.1007/s10995-007-0307-z] [PMID]

- Singhi PD, Goyal L, Pershad D, Singhi S, Walia BN. Psychosocial problems in families of disabled children. British Journal of Medical Psychology. 1990; 63(2):173-82. [DOI:10.1111/j.2044-8341.1990.tb01610.x] [PMID]

- Law J, Boyle J, Harris F, Harkness A, Nye C. Prevalence and natural history of primary speech and language delay: Findings from a systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 2000; 35(2):165-88. [PMID]

- Law J, Garrett Z, Nye C. The efficacy of treatment for children with developmental speech and language delay/disorder: A meta-analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004; 47(4):924-43. [DOI:10.1044/1092-4388(2004/069)] [PMID]

- Prelock PA, Hutchins T, Glascoe FP. Speech-language impairment: How to identify the most common and least diagnosed disability of childhood. The Medscape Journal of Medicine. 2008; 10(6):136. [Link]

- Dulčić A, Pavičić Dokoza K, Bakota K, Tadić I. Parents’ and speech and language pathologists’ attitudes toward preschool children with speech and language disorders. Logopedija. 2018; 8(1):13-20. [DOI:10.31299/log.8.1.3]

- Schery TK. Correlates of language development in language-disordered children. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1985; 50(1):73-83. [DOI:10.1044/jshd.5001.73] [PMID]

- Beitchman JH, Nair R, Clegg M, Patel PG, Ferguson B, Pressman E, et al. Prevalence of speech and language disorders in 5-year-old kindergarten children in the Ottawa-Carleton region. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1986; 51(2):98-110. [DOI:10.1044/jshd.5102.98] [PMID]

- Holley E. Parents’ feelings and perceptions towards their child’s speech or language disorder [BA thesis]. Akron: Williams Honors College; 2018. [Link]

- Diwan S, Chovatiya H, Diwan J. Depression and quality of life in mothers of children with cerebral palsy. National Journal of Integrated Research in Medicine. 2011; 2(4):81-90. [Link]

- Smith TB, Innocenti MS, Boyce GC, Smith CS. Depressive symptomatology and interaction behaviors of mothers having a child with disabilities. Psychological Reports. 1993; 73(3 Pt 2):1184-6. [DOI:10.2466/pr0.1993.73.3f.1184] [PMID]

- Berjis M, Hakim Javadi M, Taher M, Lavasani MG, Hossein Khanzadeh AA. [A comparison of the amount of worry, hope and meaning of life in the mothers of deaf children, children with autism, and children with learning disability (Persian)]. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2013; 3(1):6-27. [Link]

- Estes A, Munson J, Dawson G, Koehler E, Zhou XH, Abbott R. Parenting stress and psychological functioning among mothers of preschool children with autism and developmental delay. Autism. 2009; 13(4):375-87. [DOI:10.1177/1362361309105658] [PMID]

- Karande S, Kumbhare N, Kulkarni M, Shah N. Anxiety levels in mothers of children with specific learning disability. Journal of Postgraduate Medicine. 2009; 55(3):165-70. [DOI:10.4103/0022-3859.57388] [PMID]

- Rudolph M, Rosanowski F, Eysholdt U, Kummer P. Anxiety and depression in mothers of speech impaired children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2003; 67(12):1337-41. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2003.08.042] [PMID]

- Manuel J, Naughton MJ, Balkrishnan R, Paterson Smith B, Koman LA. Stress and adaptation in mothers of children with cerebral palsy. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003; 28(3):197-201. [DOI:10.1093/jpepsy/jsg007] [PMID]

- Ahmadizadeh Z, Rassafiani M, Khalili MA, Mirmohammadkhani M. Factors associated with quality of life in mothers of children with cerebral palsy in Iran. Hong Kong Journal of Occupational Therapy. 2015; 25(1):15-22. [DOI:10.1016/j.hkjot.2015.02.002]

- Yilmaz H, Erkin G, İzki AA. Quality of life in mothers of children with Cerebral Palsy. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2013; 2013:1-6. [Link]

- Kütük MÖ, Tufan AE, Kılıçaslan F, Güler G, Çelik F, Altıntaş E, et al. High depression symptoms and burnout levels among parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: a multi-center, cross-sectional, case-control study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2021; 51(11):4086-99. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-021-04874-4] [PMID]

- Aras I, Stevanović R, Vlahović S, Stevanović S, Kolarić B, Kondić L. Health related quality of life in parents of children with speech and hearing impairment. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 2014; 78(2):323-9. [DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.12.001] [PMID]

- Noohi S, Amirsalari S, Sabouri E, Moradi S, Saburi A. Prevalence of anxiety and depression in mothers of children with profound bilateral sensorineural hearing loss: A brief report. Medical Journal of Dr DY Patil University. 2014; 7(6):717-20. [DOI:10.4103/0975-2870.144855]

- Amiri MM, Hosseini SF, Jafari A. [Comparing the quality of life and marital intimacy among parents of children with Down syndrome, parents of children with learning disabilities, and parents of normal children (Persian)]. Journal of Learning Disabilities 2014; 4(1):38-55. [Link]

- Dambi JM, Jelsma J, Mlambo T, Chiwaridzo M, Tadyanemhandu C, Chikwanha MT, et al. A critical evaluation of the effectiveness of interventions for improving the well-being of caregivers of children with cerebral palsy: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews. 2016; 5(1):112. [PMID]

- Havaei N, Rahmani A, Mohammadi A, Rezaei M. Comparison of general health status in parents of children with cerebral palsy and healthy children. The Scientific Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2015; 4(1):99-106. [Link]

- Zamani P. [Comparison of clients’ satisfaction from public and private speech therapy clinics in Ahvaz city (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Rehabilitation Sciences. 8(7):1186-93. [Link]

- Rudolph M, Kummer P, Eysholdt U, Rosanowski F. Quality of life in mothers of speech impaired children. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology. 2005; 30(1):3-8. [DOI:10.1080/14015430410022292] [PMID]

- Vohr B, Pierre LS, Topol D, Jodoin-Krauzyk J, Bloome J, Tucker R. Association of maternal communicative behavior with child vocabulary at 18-24 months for children with congenital hearing loss. Early Human Development. 2010; 86(4):255-60. [DOI:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2010.04.002] [PMID]

- Topol D, Girard N, St Pierre L, Tucker R, Vohr B. The effects of maternal stress and child language ability on behavioral outcomes of children with congenital hearing loss at 18-24 months. Early Human Development. 2011; 87(12):807-11. [DOI:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2011.06.006] [PMID]

- Kaplan PS, Danko CM, Kalinka CJ, Cejka AM. A developmental decline in the learning-promoting effects of infant-directed speech for infants of mothers with chronically elevated symptoms of depression. Infant Behavior and Development. 2012; 35(3):369-79. [DOI:10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.02.009] [PMID]

- Weikum WM, Oberlander TF, Hensch TK, Werker JF. Prenatal exposure to antidepressants and depressed maternal mood alter trajectory of infant speech perception. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012; 109(Supplement 2):17221-7. [DOI:10.1073/pnas.1121263109] [PMID]

- Shirzadi P, Framarzi S, Ghasemi M, Shafiee M. [Investigating Validity and reliability of Parenting Stress Index-short form among Fathers of normal child under 7 years old (Persian)]. Rooyesh-e-Ravanshenasi Journal (RRJ). 2015; 3(4):91-110. [Link]

- Fadae Z, Dehghani M, Tahmasian K, Farhadi F. [Investigating reliability, validity and factor structure of parenting stress-short form in mothers of 7-12 year-old children (Persian)]. Journal of Research in Behavioural Sciences. 2011; 8(2):81-91. [Link]

- Tardast K, Amanelahi A, Rajabi G, Aslani K, Shiralinia K. [The effectiveness of acceptance and commitment-based parenting education on children’s anxiety and the parenting stress of mothers (Persian)]. Payesh. 2021; 20 (1):91-107. [DOI:10.29252/payesh.20.1.91]

- Hamidi R, Fekrizadeh Z, Azadbakht M, Garmaroudi Gh, Taheri Tanjani P, Fathizadeh Sh, et al. [Validity and reliability Beck Depression Inventory-II among the Iranian elderly population (Persian)]. Journal of Sabzevar University of Medical Sciences. 2015; 22(1):189-98. [Link]

- Rajabi G, Karju Kasmai S. [Psychometric properties of a Persian language version of the beck depression inventory second edition (Persian)]. Educational Measurement. 2013; 3(10):139-58. [Link]

- García-Batista ZE, Guerra-Peña K, Cano-Vindel A, Herrera-Martínez SX, Medrano LA.Validity and reliability of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II) in general and hospital population of Dominican Republic. PLoS One. 2018; 13(6):e0199750.[DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0199750] [PMID]

- Kühner C, Bürger C, Keller F, Hautzinger M. [Reliability and validity of the Revised Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II). Results from German samples (German)]. Der Nervenarzt. 2007; 78(6):651-6. [DOI:10.1007/s00115-006-2098-7] [PMID]

- Montazeri A, Goshtasebi A, Vahdaninia M, Gandek B. The Short Form Health Survey (SF-36): Translation and validation study of the Iranian version. Quality of Life Research. 2005; 14(3):875-82. [DOI:10.1007/s11136-004-1014-5] [PMID]

- Bunevicius A. Reliability and validity of the SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire in patients with brain tumors: A cross-sectional study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes. 2017; 15(1):92. [DOI:10.1186/s12955-017-0665-1] [PMID]

- Pinar R. Reliability and construct validity of the SF-36 in Turkish cancer patients. Quality of Life Research. 2005, 14(1):259-64. [DOI:10.1007/s11136-004-2393-3] [PMID]

- Lera L, Fuentes-García A, Sánchez H, Albala C. Validity and reliability of the SF-36 in Chilean older adults: The ALEXANDROS study. European Journal of Ageing. 2013; 10(2):127-34. [DOI:10.1007/s10433-012-0256-2] [PMID]

- Gómez-Besteiro MI, Santiago-Pérez MI, Alonso-Hernández A, Valdés-Cañedo F, Rebollo-Alvarez P. Validity and reliability of the SF-36 questionnaire in patients on the waiting list for a kidney transplant and transplant patients. American Journal of Nephrology. 2004; 24(3):346-51. [DOI:10.1159/000079053] [PMID]

- Asghari Moghaddam M, Faghehi S. [Validation of the SF-36 health survey questionnaire in two Iranian samples (Persian)]. Clinical Psychology and Personality. 2003; 1(1):1-10. [Link]

- Benson P, Karlof KL, Siperstein GN. Maternal involvement in the education of young children with autism spectrum disorders. Autism. 2008; 12(1):47-63. [DOI:10.1177/1362361307085269] [PMID]

- Forsingdal S, St John W, Miller V, Harvey A, Wearne P. Goal setting with mothers in child development services. Child: Care, Health and Development. 2014; 40(4):587-96. [DOI:10.1111/cch.12075] [PMID]

- Beresford BA. Resources and strategies: How parents cope with the care of a disabled child. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1994; 35(1):171-209. [DOI:10.1111/j.1469-7610.1994.tb01136.x] [PMID]

- Robertson SB, Ellis Weismer S. Effects of treatment on linguistic and social skills in toddlers with delayed language development. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999; 42(5):1234-48. [DOI:10.1044/jslhr.4205.1234] [PMID]

- Burger T, Spahn C, Richter B, Eissele S, Löhle E, Bengel J. Parental distress: The initial phase of hearing aid and cochlear implant fitting. American Annals of The Deaf. 2005; 150(1):5-10. [DOI:10.1353/aad.2005.0017] [PMID]

- Lederberg AR, Golbach T. Parenting stress and social support in hearing mothers of deaf and hearing children: A longitudinal study. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education. 2002; 7(4):330-45. [DOI:10.1093/deafed/7.4.330] [PMID]

- Eslami Shahrbabaki M, Mazhari S, Haghdoost AA, Zamani Z. [Anxiety, depression, quality of life and general health of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (Persian)]. Health and Development Journal. 2018; 6(4):314-22. [Link]

- Ogeston PaulaL, MackintoshVH, Myers BJ. Hope and worry in mothers of children with an autism spectrum disorder or Down syndrome. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders. 2011; 5(4):1378-84. [DOI:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.01.020]

- Lloyd TJ, Hastings R. Hope as a psychological resilience factor in mothers and fathers of children with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. 2009; 53(12):957-68. [DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2788.2009.01206.x] [PMID]

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Speech & Language Pathology

Received: 16/10/2022 | Accepted: 15/05/2023 | Published: 1/10/2023

Received: 16/10/2022 | Accepted: 15/05/2023 | Published: 1/10/2023

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |