Volume 21, Issue 3 (Autumn 2020)

jrehab 2020, 21(3): 358-375 |

Back to browse issues page

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Koohestani F, Rezaei P, Nakhshab M. Developing a Persian Version of the Checklist of Pragmatic Behaviors and Assessing Its Psychometric Properties: A Preliminary Study. jrehab 2020; 21 (3) :358-375

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2578-en.html

URL: http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-2578-en.html

1- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran., Isfahan, hezar jrib street , Isfahan University of Medical Sciences,School of Rehabilitation Sciences

2- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,m_nakhshab@yahoo.com

2- Department of Speech Therapy, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran. ,

Full-Text [PDF 6301 kb]

(2089 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (5030 Views)

The Chi-square with a score of 0.006 (<0.05 is acceptable), CMIN with a score of 1.291 (<3 is acceptable), RMSEA with a score of 0.06 (<0.08 is acceptable), IFI with a score of 0.921 (>0.9 is acceptable), PCFI=0.682 and PNFI=0.522 (>0.5 is acceptable) showed that the 4-factor model fit the data reasonably. These factors were called “conversational skills”, “information organization”, “descriptive skills”, and “actions”.

In assessing criterion validity, the mean correlation between the total score of the Persian CBP and the personal-social subscale score of the ages and stages questionnaire was obtained 0.583 (P<0.001), and it had a weak negative correlation with the behavioral problem questionnaire (r= -0.286). The Cronbach α coefficient for the internal consistency of the 25 items was obtained 0.839. The agreement between the raters was obtained 98% from the calculation of 30% of the samples in random offline scoring, and the agreement between online and offline scoring was 96%. The correlation between the score of the first test and retest was 0.665 (P=0.007), which was significant and moderate. The total score and the score of the communicative intents subscale were not significantly different between girls and boys, although the mean total score of the boys was higher than that of girls. Table 4 presents the categorization of the checklist items based on participants’ response patterns.

Discussion and conclusion

Comparing the total score of the Persian CPB and the scores of its two subscales of communicative intents and conversational devices showed a significant difference in these scores between the three age groups. This result is consistent with the results of Rolph et al. in 1979 (P≤0.05) and Carrpenter et al. in 1988 (P=0.0003). Comparison of the total CPB score using on post hoc test showed a significant difference between 3 and 5 years age groups and between 4 and 5 years age groups, indicating that the Persian CPB had good age-based discriminant validity Persian-speaking children. The total CPB score in the three groups was significantly different, where the development of pragmatics skills was higher in the 5-year-old children. This result is consistent with the results of Rolph et al. in 1979 and Carrpenter et al. in 1988. There was a significant difference between the three age groups in the scores of the three skills of hypothesizing, closing conversation, giving expanded answers in our study, while only the skill of “giving expanded answers” was significantly different in Carrpenter et al.’s study. Regarding the skill “taking turns”, the results of the present study were in line with the studies by Blain-Brière et al. in 2014 and Rahgozar et al. in 2009. This skill was present in most children aged >3 years. Regarding the skills of answering, attending to the speaker, and maintaining a topic, the results were consistent with Fangman’s study in 1982, in which all participants acquired these three skills. However, in Rolph et al.’s research, only the skill of maintaining a topic was acquired by all participants. The level of maintaining a topic depends on the type of task and the presented topic. Greeting and request for information skills were acquired by more than 60% of the children, while in Carrpenter et al.’s study, these skills differed significantly between the three age groups. The discrepancy in the results can indicate the differences in the age of acquisition and how to use pragmatics skills, which are influenced by culture and language. In different cultures, there are different expectations of children during their communication, and many communication norms are varied in different cultures. This difference in expectations and norms can lead to differences in children’s communicative methods and even differences in the development of pragmatics skills. For example, in Korean culture, greeting the elder is a very important behavior and is considered disrespectful not doing it. Persian-speaking people use politer words during greeting compared to English-speaking people because they think this can prevent communication problems. For making requests, Persians request less directly than Americans and Canadians. As a result, children’s pragmatics skills are developed according to the communication norms of each culture.

In Rolph et al.’s study, the results of factor analysis of the pragmatics checklist included three factors [17], while there were 4 factors for the pragmatics checklist in our research. The loading of some factors was less than 0.5 (minimum acceptable value). However, since this study was a preliminary study and the sample size was small compared to the number of variables, there was a need to examine variables with higher sample size, and, therefore, we refused to remove variables whose factor load value was less than 0.5. The Persian CPB showed a moderate correlation with ASQ and had acceptable criterion validity. That is, with the improvement of pragmatics skills in children, their social skills improve. The Persian CPB showed a weak negative correlation with the behavioral problem questionnaire. With the improvement of pragmatics skills in children, their behavioral problems became reduced a little. The reason for this result could be that the behavioral problem questionnaire assesses many destructive behaviors in children.

Moreover, since the behavioral problem questionnaire was designed for parents in kindergartens, parents were biased in completing it due to fear of labeling their children. Another reason can be that behavioral problems may increase over time. The Persian CPB had a high internal consistency, which indicates that this checklist measures a single structure (pragmatics behaviors). The test-retest reliability assessment of the Persian CPB showed a moderate correlation between the scores, indicating its acceptable test-retest reliability. The high agreement between online and offline scoring of the Persian CPB indicated the adequacy of online scoring without offline scoring in implementing this checklist.

The Persian CPB has acceptable validity and reliability. However, to decide whether this checklist can be used as a screening tool for Persian-speaking children, we need further studies with larger sample sizes. Some results of the present study differed from the results of previous studies, which may be due to differences in language and culture, which are the critical factors in the development of cognitive pragmatics skills. Because of the fundamental differences in language and culture, the age of acquisition, and the way of using pragmatics skills in the Persian language are different from those in the English language. Based on the cultural differences, a child may use some behaviors less or not at all.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: 1397.045). The participated child's parents completed an informed. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the MSc. thesis of the first author, Department of speech therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Also, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences supported financially this study.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mahbubeh Nakhshab, Parisa Rezaei and Faezeh Koohestani; Methodology: Faezeh Koohestani, Mahbubeh Nakhshab; Investigation, writing – original draft, and writing – review & editing: All authors; Data collection: Faezeh Koohestani and Mahbubeh Nakhshab; Data analysis: Mahbubeh Nakhshab and Faezeh Koohestani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

Full-Text: (3502 Views)

Introduction

Pragmatics is defined as the purposeful use of language for social purposes and interaction with other people, which requires the coordination of linguistic information with expressive movements, facial expressions, body movements, and the use of information in the physical, social, and verbal contexts. Given the importance of language and communication skills, after entering school, pragmatics plays an essential role in determining academic success and affects reading performance in the future. As a result, deficiencies in pragmatics skills lead to communication deficits and, subsequently, social and academic failures. Therefore, evaluation and identification of pragmatics deficits at an early age allows early intervention and prevents the development of related disorders and the creation of secondary problems such as educational and social problems. In other languages, a variety of tools have been developed to evaluate the pragmatics skills, including formal tests, conversation analysis tools, discourse analysis tools, checklists, and observation tools. Checklists are typically easy-to-use tools that assess a variety of aspects of pragmatism and also cover context-related features of pragmatics skills. The basis for evaluation in these checklists is observing patient’s behaviors or interviewing caregivers. There are several valid and well-known checklists in English for assessing pragmatics skills, including Dewart and Summers’ pragmatics profile and Bishop’s children’s communication checklist (CCC). Given the importance of early intervention in pragmatics impairments and its context-dependent nature, observational tools are needed to assess these skills in preschool age.

Craighead’s checklist of pragmatic behaviors (CPB) is an observational checklist that assesses communicative intents (such as greeting and requesting for an object) and conversational devices (such as maintaining and specifying a topic) in children aged 3-5 years. This checklist specifically examines pragmatics skills and has 25 items. This protocol provides an activity for each item that, by performing that activity, the examiner can test the selected skill. This checklist is designed for English-speaking children and has been used in several studies on both groups of children with normal and impaired growth, including those with developmental, intellectual disabilities, hearing loss, and cognitive impairments [16, 17].

To our knowledge, there is no coherent observational tool for assessing the pragmatic behaviors of preschool Persian-speaking children. In this regard, this study aims to translate and customize the CPB for Persian-speaking children aged 3-5 years and then evaluate its validity and reliability.

Materials and Methods

This research is a methodological study with a cross-sectional design conducted in 2018. Study samples were 63 children in three age groups of 3, 4, and 5 years selected from kindergartens in Isfahan City, Iran, using the cluster sampling method. The inclusion criteria comprise being 3-5 years old and a Persian speaker. The studied variables included 25 pragmatic behaviors in the CPB. The checklist and evaluation protocols were first translated. The initial translated version was sent to 8 speech clinical therapists. According to their comments and the opinions of two speech and language pathologists who had experience in the field of pragmatism and were fluent in English, the final changes in the translation were made. According to Iranian culture, some words changed in the Persian version. The discriminant validity of the Persian version was assessed based on age. Its criterion validity was measured by calculating the correlation between the total score of the CPB and the total score of the other two tests, including the personal-social subscale of ages and stages questionnaire (ASQ) and behavioral problem questionnaire since pragmatics skills are related to social skills. Then, its internal consistency was measured by calculating the Cronbach alpha coefficient. Its test-retest reliability and inter-rater reliability were also measured. To determine the adequacy of online scoring, we examined the correlation between offline and online scoring.

The informed consent forms and two ages and stages questionnaire and behavioral problem questionnaire were signed and completed by the parents in a room of kindergarten with a suitable number of tables and chairs. At the assessment session, the rater first spent a few minutes communicating with the child, and then the assessment protocol was implemented. Assessments were performed by two trained speech and language pathologists. The first activity of the peanut butter test was used to complete the CPB, and its second activity was used to perform the retest. The execution time was between 15 and 20 minutes. The scoring was done online and offline. If the child did not answer, s/he would be given a 0 score, and if answered (verbally or non-verbally), s/he was assigned a score of 1. The total score was obtained from the summing up of the given scores for each item. Fifteen participants were re-evaluated for measuring test-retest reliability.

The obtained data were analyzed in SPSS V. 21. The non-normality of the data distribution, nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis, and Mann-Whitney tests were used to examine discriminant validity. Also, the Spearman correlation test was used to check criterion validity and measure test-retest reliability and inter-rater reliability of the Persian CBP. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed in AMOS software. The Chi-square test was used to compare the scores of each item in three age groups.

Results

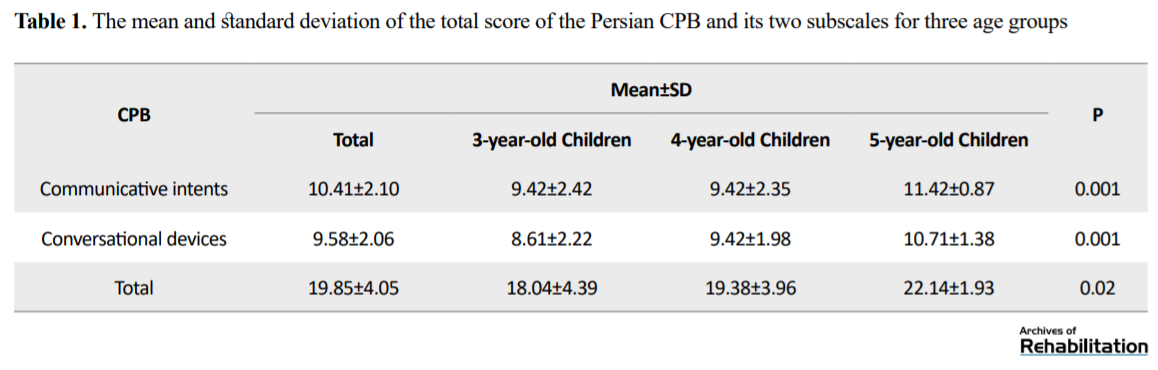

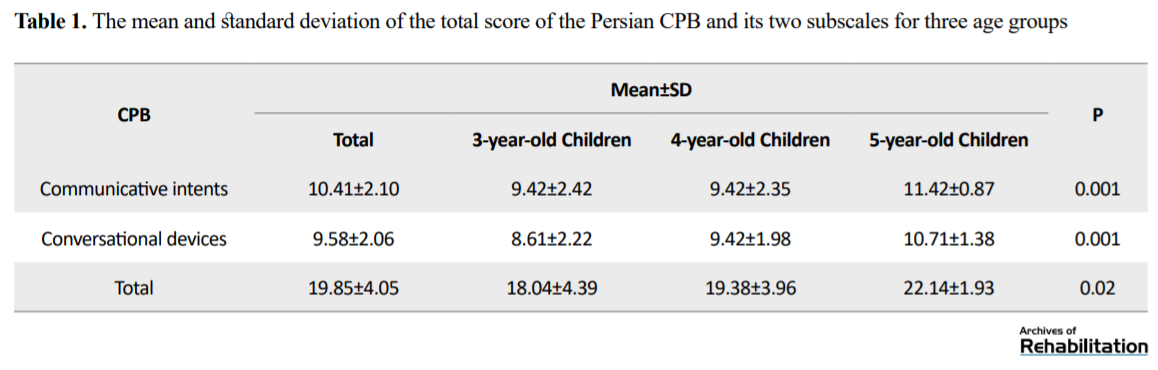

The participants were 63 children (33 girls, 30 boys) in three age groups of 3, 4, and 5 years. According to Table 1, in the assessment of age-based discriminant validity, the difference in total score (P=0.02) and in scores of communicative intents and conversational devices (P<0.001) was significant between the three groups such that these scores increased with the increase of age.

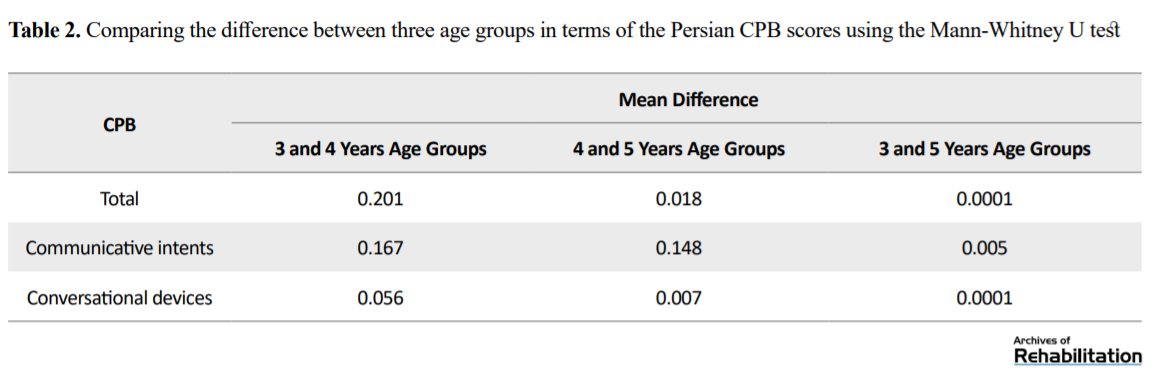

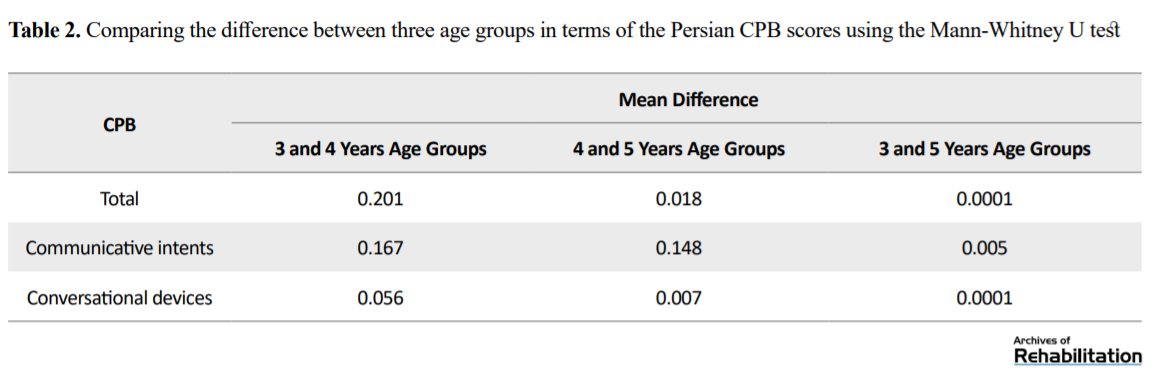

The post hoc test results of these three scores are presented in Table 2.

In comparing the score of each CBP item between the three age groups, the results showed a significant difference in the score difference of three items out of 25 items. These items were hypothesizing (P<0.007), closing conversation (P=0.01), and giving expanded answers (P=0.001).

In assessing factor validity, three of 25 items had zero variance and were excluded from factor analysis. These items were answering, attending to the speaker, and maintaining a topic. Then, exploratory factor analysis was performed, and 4 factors with a variance of 52% were identified. According to Table 3, in which the factor load of each of the checklist items is presented, the 5-factor model obtained from the exploratory factor analysis was entered into the confirmatory factor analysis.

Pragmatics is defined as the purposeful use of language for social purposes and interaction with other people, which requires the coordination of linguistic information with expressive movements, facial expressions, body movements, and the use of information in the physical, social, and verbal contexts. Given the importance of language and communication skills, after entering school, pragmatics plays an essential role in determining academic success and affects reading performance in the future. As a result, deficiencies in pragmatics skills lead to communication deficits and, subsequently, social and academic failures. Therefore, evaluation and identification of pragmatics deficits at an early age allows early intervention and prevents the development of related disorders and the creation of secondary problems such as educational and social problems. In other languages, a variety of tools have been developed to evaluate the pragmatics skills, including formal tests, conversation analysis tools, discourse analysis tools, checklists, and observation tools. Checklists are typically easy-to-use tools that assess a variety of aspects of pragmatism and also cover context-related features of pragmatics skills. The basis for evaluation in these checklists is observing patient’s behaviors or interviewing caregivers. There are several valid and well-known checklists in English for assessing pragmatics skills, including Dewart and Summers’ pragmatics profile and Bishop’s children’s communication checklist (CCC). Given the importance of early intervention in pragmatics impairments and its context-dependent nature, observational tools are needed to assess these skills in preschool age.

Craighead’s checklist of pragmatic behaviors (CPB) is an observational checklist that assesses communicative intents (such as greeting and requesting for an object) and conversational devices (such as maintaining and specifying a topic) in children aged 3-5 years. This checklist specifically examines pragmatics skills and has 25 items. This protocol provides an activity for each item that, by performing that activity, the examiner can test the selected skill. This checklist is designed for English-speaking children and has been used in several studies on both groups of children with normal and impaired growth, including those with developmental, intellectual disabilities, hearing loss, and cognitive impairments [16, 17].

To our knowledge, there is no coherent observational tool for assessing the pragmatic behaviors of preschool Persian-speaking children. In this regard, this study aims to translate and customize the CPB for Persian-speaking children aged 3-5 years and then evaluate its validity and reliability.

Materials and Methods

This research is a methodological study with a cross-sectional design conducted in 2018. Study samples were 63 children in three age groups of 3, 4, and 5 years selected from kindergartens in Isfahan City, Iran, using the cluster sampling method. The inclusion criteria comprise being 3-5 years old and a Persian speaker. The studied variables included 25 pragmatic behaviors in the CPB. The checklist and evaluation protocols were first translated. The initial translated version was sent to 8 speech clinical therapists. According to their comments and the opinions of two speech and language pathologists who had experience in the field of pragmatism and were fluent in English, the final changes in the translation were made. According to Iranian culture, some words changed in the Persian version. The discriminant validity of the Persian version was assessed based on age. Its criterion validity was measured by calculating the correlation between the total score of the CPB and the total score of the other two tests, including the personal-social subscale of ages and stages questionnaire (ASQ) and behavioral problem questionnaire since pragmatics skills are related to social skills. Then, its internal consistency was measured by calculating the Cronbach alpha coefficient. Its test-retest reliability and inter-rater reliability were also measured. To determine the adequacy of online scoring, we examined the correlation between offline and online scoring.

The informed consent forms and two ages and stages questionnaire and behavioral problem questionnaire were signed and completed by the parents in a room of kindergarten with a suitable number of tables and chairs. At the assessment session, the rater first spent a few minutes communicating with the child, and then the assessment protocol was implemented. Assessments were performed by two trained speech and language pathologists. The first activity of the peanut butter test was used to complete the CPB, and its second activity was used to perform the retest. The execution time was between 15 and 20 minutes. The scoring was done online and offline. If the child did not answer, s/he would be given a 0 score, and if answered (verbally or non-verbally), s/he was assigned a score of 1. The total score was obtained from the summing up of the given scores for each item. Fifteen participants were re-evaluated for measuring test-retest reliability.

The obtained data were analyzed in SPSS V. 21. The non-normality of the data distribution, nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis, and Mann-Whitney tests were used to examine discriminant validity. Also, the Spearman correlation test was used to check criterion validity and measure test-retest reliability and inter-rater reliability of the Persian CBP. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed in AMOS software. The Chi-square test was used to compare the scores of each item in three age groups.

Results

The participants were 63 children (33 girls, 30 boys) in three age groups of 3, 4, and 5 years. According to Table 1, in the assessment of age-based discriminant validity, the difference in total score (P=0.02) and in scores of communicative intents and conversational devices (P<0.001) was significant between the three groups such that these scores increased with the increase of age.

The post hoc test results of these three scores are presented in Table 2.

In comparing the score of each CBP item between the three age groups, the results showed a significant difference in the score difference of three items out of 25 items. These items were hypothesizing (P<0.007), closing conversation (P=0.01), and giving expanded answers (P=0.001).

In assessing factor validity, three of 25 items had zero variance and were excluded from factor analysis. These items were answering, attending to the speaker, and maintaining a topic. Then, exploratory factor analysis was performed, and 4 factors with a variance of 52% were identified. According to Table 3, in which the factor load of each of the checklist items is presented, the 5-factor model obtained from the exploratory factor analysis was entered into the confirmatory factor analysis.

The Chi-square with a score of 0.006 (<0.05 is acceptable), CMIN with a score of 1.291 (<3 is acceptable), RMSEA with a score of 0.06 (<0.08 is acceptable), IFI with a score of 0.921 (>0.9 is acceptable), PCFI=0.682 and PNFI=0.522 (>0.5 is acceptable) showed that the 4-factor model fit the data reasonably. These factors were called “conversational skills”, “information organization”, “descriptive skills”, and “actions”.

In assessing criterion validity, the mean correlation between the total score of the Persian CBP and the personal-social subscale score of the ages and stages questionnaire was obtained 0.583 (P<0.001), and it had a weak negative correlation with the behavioral problem questionnaire (r= -0.286). The Cronbach α coefficient for the internal consistency of the 25 items was obtained 0.839. The agreement between the raters was obtained 98% from the calculation of 30% of the samples in random offline scoring, and the agreement between online and offline scoring was 96%. The correlation between the score of the first test and retest was 0.665 (P=0.007), which was significant and moderate. The total score and the score of the communicative intents subscale were not significantly different between girls and boys, although the mean total score of the boys was higher than that of girls. Table 4 presents the categorization of the checklist items based on participants’ response patterns.

Discussion and conclusion

Comparing the total score of the Persian CPB and the scores of its two subscales of communicative intents and conversational devices showed a significant difference in these scores between the three age groups. This result is consistent with the results of Rolph et al. in 1979 (P≤0.05) and Carrpenter et al. in 1988 (P=0.0003). Comparison of the total CPB score using on post hoc test showed a significant difference between 3 and 5 years age groups and between 4 and 5 years age groups, indicating that the Persian CPB had good age-based discriminant validity Persian-speaking children. The total CPB score in the three groups was significantly different, where the development of pragmatics skills was higher in the 5-year-old children. This result is consistent with the results of Rolph et al. in 1979 and Carrpenter et al. in 1988. There was a significant difference between the three age groups in the scores of the three skills of hypothesizing, closing conversation, giving expanded answers in our study, while only the skill of “giving expanded answers” was significantly different in Carrpenter et al.’s study. Regarding the skill “taking turns”, the results of the present study were in line with the studies by Blain-Brière et al. in 2014 and Rahgozar et al. in 2009. This skill was present in most children aged >3 years. Regarding the skills of answering, attending to the speaker, and maintaining a topic, the results were consistent with Fangman’s study in 1982, in which all participants acquired these three skills. However, in Rolph et al.’s research, only the skill of maintaining a topic was acquired by all participants. The level of maintaining a topic depends on the type of task and the presented topic. Greeting and request for information skills were acquired by more than 60% of the children, while in Carrpenter et al.’s study, these skills differed significantly between the three age groups. The discrepancy in the results can indicate the differences in the age of acquisition and how to use pragmatics skills, which are influenced by culture and language. In different cultures, there are different expectations of children during their communication, and many communication norms are varied in different cultures. This difference in expectations and norms can lead to differences in children’s communicative methods and even differences in the development of pragmatics skills. For example, in Korean culture, greeting the elder is a very important behavior and is considered disrespectful not doing it. Persian-speaking people use politer words during greeting compared to English-speaking people because they think this can prevent communication problems. For making requests, Persians request less directly than Americans and Canadians. As a result, children’s pragmatics skills are developed according to the communication norms of each culture.

In Rolph et al.’s study, the results of factor analysis of the pragmatics checklist included three factors [17], while there were 4 factors for the pragmatics checklist in our research. The loading of some factors was less than 0.5 (minimum acceptable value). However, since this study was a preliminary study and the sample size was small compared to the number of variables, there was a need to examine variables with higher sample size, and, therefore, we refused to remove variables whose factor load value was less than 0.5. The Persian CPB showed a moderate correlation with ASQ and had acceptable criterion validity. That is, with the improvement of pragmatics skills in children, their social skills improve. The Persian CPB showed a weak negative correlation with the behavioral problem questionnaire. With the improvement of pragmatics skills in children, their behavioral problems became reduced a little. The reason for this result could be that the behavioral problem questionnaire assesses many destructive behaviors in children.

Moreover, since the behavioral problem questionnaire was designed for parents in kindergartens, parents were biased in completing it due to fear of labeling their children. Another reason can be that behavioral problems may increase over time. The Persian CPB had a high internal consistency, which indicates that this checklist measures a single structure (pragmatics behaviors). The test-retest reliability assessment of the Persian CPB showed a moderate correlation between the scores, indicating its acceptable test-retest reliability. The high agreement between online and offline scoring of the Persian CPB indicated the adequacy of online scoring without offline scoring in implementing this checklist.

The Persian CPB has acceptable validity and reliability. However, to decide whether this checklist can be used as a screening tool for Persian-speaking children, we need further studies with larger sample sizes. Some results of the present study differed from the results of previous studies, which may be due to differences in language and culture, which are the critical factors in the development of cognitive pragmatics skills. Because of the fundamental differences in language and culture, the age of acquisition, and the way of using pragmatics skills in the Persian language are different from those in the English language. Based on the cultural differences, a child may use some behaviors less or not at all.

Ethical Considerations

Compliance with ethical guidelines

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Code: 1397.045). The participated child's parents completed an informed. They were also assured about the confidentiality of their information and were free to leave the study whenever they wished, and if desired, the research results would be available to them.

Funding

The paper was extracted from the MSc. thesis of the first author, Department of speech therapy, School of Rehabilitation, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences. Also, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences supported financially this study.

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization and supervision: Mahbubeh Nakhshab, Parisa Rezaei and Faezeh Koohestani; Methodology: Faezeh Koohestani, Mahbubeh Nakhshab; Investigation, writing – original draft, and writing – review & editing: All authors; Data collection: Faezeh Koohestani and Mahbubeh Nakhshab; Data analysis: Mahbubeh Nakhshab and Faezeh Koohestani.

Conflict of interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Russell RL, Grizzle KL. Assessing child and adolescent pragmatic language competencies: Toward evidence-based assessments. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2008; 11(1-2):59-73. [DOI:10.1007/s10567-008-0032-1] [PMID]

- Cummings L. Clinical pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. p. 180-95. [DOI:10.1017/CBO9780511581601]

- Creaghead NA. Strategies for evaluating and targeting pragmatic behaviors in young children. Seminars in Speech and Language. 1984; 5(3):241-52. [DOI:10.1055/s-0028-1085181]

- Matthews D. Introduction: An overview of research on pragmatic development. In: Matthews D, editor. Pragmatic Development in First Language Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2014. p. 1-12. [DOI:10.1075/tilar.10.01mat]

- O’Neill DK. Assessing pragmatic language functioning in young children: Its importance and challenges. In: Matthews D, editor. Pragmatic Development in First Language Acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company; 2014. p. 363-386. [DOI:10.1075/tilar.10.20nei]

- Donno R, Parker G, Gilmour J, Skuse DH. Social communication deficits in disruptive primary-school children. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2010; 196(4):282-9. [DOI:10.1192/bjp.bp.108.061341] [PMID]

- Cummings L, editor. Research in clinical pragmatics. Cham: Springer; 2017. [DOI:10.1007/978-3-319-47489-2]

- Loveland KA, Landry SH, Hughes SO, Hall SK, McEvoy RE. Speech acts and the pragmatic deficits of autism. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1988; 31(4):593-604. [DOI:10.1044/jshr.3104.593] [PMID]

- Kim OH, Kaiser AP. Language characteristics of children with ADHD. Communication Disorders Quarterly. 2000; 21(3):154-65. [DOI:10.1177/152574010002100304]

- Adams C. Practitioner review: The assessment of language pragmatics. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002; 43(8):973-87. [DOI:10.1111/1469-7610.00226] [PMID]

- Miller L. Pragmatics and early childhood language disorders: Communicative interactions in a half-hour sample. The Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1978; 43(4):419-36. [DOI:10.1044/jshd.4304.419] [PMID]

- Prutting CA, Kirchner DM. A clinical appraisal of the pragmatic aspects of language. The Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders. 1987; 52(2):105-19. [DOI:10.1044/jshd.5202.105] [PMID]

- Bishop DVM. Development of the Children’s Communication Checklist (CCC): A method for assessing qualitative aspects of communicative impairment in children. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1998; 39(6):879-91. [DOI:10.1111/1469-7610.00388]

- Simmons ES, Paul R, Volkmar F. Assessing pragmatic language in autism spectrum disorder: The Yale in vivo pragmatic protocol. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2014; 57(6):2162-73. [DOI:10.1044/2014_JSLHR-L-14-0040] [PMID]

- Fangman MA. An examination of pragmatic behaviors of hearing impaired children ages three, four and five years using two testing formats [Master thesis]. Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati; 1982.

- Carpenter AE, Strong J. Pragmatic development in normal children: Assessment of testing protocol. NSSLHA Journal. 1988; 16:40-9. [DOI:10.1044/nsshla_16_40]

- Rolph TK. Development of a test of pragmatics for children ages three, four, and five[Master thesis]. Cincinnati: University of Cincinnati; 1979.

- Blain-Brière B, Bouchard C, Bigras N. The role of executive functions in the pragmatic skills of children age 4-5. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014; 5:240. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00240] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Dodd JL, Franke LK, Grzesik JK, Stoskopf J. Comprehensive multi-disciplinary assessment protocol for autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual Disability-Diagnosis and Treatment. 2014; 2(1):68-82. [DOI:10.6000/2292-2598.2014.02.01.9]

- Rahgozar M, Mousavi N, Shirazi S, Daroui A, Danaye-Tousi M, Pourshahbaz A. [Comparison of some of pragmatic skills between 4 to 6 years old Farsi speaking hard of hearing children with normal hearing peers (Persian)]. Archives of Rehabilitation. 2009; 10(3):60-5. http://rehabilitationj.uswr.ac.ir/article-1-378-en.html

- Ghayoumi Anaraki Z, Ghasisin L, Mahmoodi Bakhtiari B, Fallah A, Salehi F, Parishan E. [Conversational repair strategies in 3 and 5 year old normal Persian-speaking children in Ahwaz, Iran (Persian)]. Auditory and Vestibular Research. 2013; 22(1):25-31. https://avr.tums.ac.ir/index.php/avr/article/view/329

- Keyhani MR, Agharasuli Z, Modarresi Y, Nakhshab M. [Conversational repair strategies in normal children (Persian)]. Research in Rehabilitation Sciences. 2010; 6(1):45-51. http://jrrs.mui.ac.ir/index.php/jrrs/article/view/120

- Harkness J. Guidelines for best practice in cross-cultural surveys. Michigan: University of Michigan; 2011.

- Hooman HA. [Educational and psychological measurements (Persian)]. 17th ed. Tehran: Payke Farhang; 2015. p. 187-228. http://opac.nlai.ir/opac-prod/bibliographic/749118

- Sajedi F, Vameghi R, Kraskian Mojembari A, Habibollahi A, Lornejad H, Delavar B. [Standardization and validation of the ASQ developmental disorders screening tool in children of Tehran city (Persian)]. Tehran University Medical Journal. 2012; 70(7):436-46. http://tumj.tums.ac.ir/article-1-97-en.html

- Shahim S, Yousefi F. [Behavioral problem questionnaire for preschool children parental special (Persian)]. Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities of Shiraz University. 1999; (29):19-32. https://www.noormags.ir/view/fa/articlepage/42774/

- Kim SH, Junker D, Lord C. Observation of Spontaneous Expressive Language (OSEL): A new measure for spontaneous and expressive language of children with autism spectrum disorders and other communication disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2014; 44(12):3230-44. [DOI:10.1007/s10803-014-2180-0] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Trosborg A, editor. Pragmatics across languages and cultures. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter; 2010. [DOI:10.1515/9783110214444]

- Hegde MN, Maul CA. Language disorders in children: An evidence-based approach to assessment and treatment. Boston: Pearson; 2006. https://books.google.com/books?id=gdAJAQAAMAAJ&dq

- Song MJ, Smetana JG, Kim SY. Korean children’s conceptions of moral and conventional transgressions. Developmental Psychology. 1987; 23(4):577-82. [DOI:10.1037/0012-1649.23.4.577]

- Salmani-Nodoushan MA. Greeting forms in English and Persian: A socio-pragmatic perspective. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences. 2007; 4(3):355-62. https://medwelljournals.com/abstract/?doi=pjssci.2007.355.362

- Keshavarz MH, Eslami ZR, Ghahraman V. Pragmatic transfer and Iranian EFL refusals: A cross-cultural perspective of Persian and English. In: Bardovi-Harlig K, Félix-Brasdefer JC, Omar AS, editors. Pragmatics & Language Learning. Vol. 11. Honolulu, HI: National Foreign Language Resource Center; 2006. p. 359-403. https://books.google.com/books?id=v_HdzvVs48oC&dq

- Nakhle M, Naghavi M, Razavi A. Complaint behaviors among native speakers of Canadian English, Iranian EFL learners, and native speakers of Persian (Contrastive Pragmatic Study). Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2014; 98:1316-24. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.548]

- Mey JL, editor. Concise encyclopedia of pragmatics. 2nd ed. Oxford: Elsevier; 2009. https://books.google.com/books?id=GcmXgeBE7k0C&dq

Type of Study: Original |

Subject:

Speech & Language Pathology

Received: 22/01/2019 | Accepted: 11/04/2020 | Published: 1/10/2020

Received: 22/01/2019 | Accepted: 11/04/2020 | Published: 1/10/2020

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |